муниципальное бюджетное общеобразовательное учреждение средняя общеобразовательная школа № 60 имени пятого гвардейского Донского казачьего кавалерийского Краснознаменного Будапештского корпуса Советского района г. Ростова-на-Дону

(МБОУСОШ № 60)

REPORT

PHENOMENON OF PLAYING UPON WORDS IN MASS MEDIA

BY EXAMPLE OF NEWSPAPER HEADLINES

Prepared by:

Dzyubenko Vladislava

Academic supervisor:

Nekrasova T. Yu.

Rostov-on-Don

2015

Contents:

|

3 4 9 13 14 15 |

- Introduction

«Everything that I know is that I see in newspapers. The good reader of all in a year can learn from newspapers everything that most of people learn in the years spent in libraries».

Brian Smith

Object of research is a word-play in English headings.

Relevance of research is caused by the high welfare importance of heading presently.

The aim of research is studying of features of a word-play in newspaper headings.

The novelty of research consists in consecutive studying of modern headings and means of a word-play.

The material of research is examples of 11 English-language newspapers from newspaper publicistic editions of the English, American and Irish press.

- Theoretical part

Currently, the scope of the concept playing upon words includes a huge number of events taking place in literature, media and advertising texts, as well as in everyday speech. The notion of playing upon words relates to the field of speech communication, and playing upon words itself is regarded as «embellishment» speech that «usually has the character of jokes, chats, puns, jokes, etc.» [2, p. 138].

The study was conducted on the material of English titles of publications website Inosmi containing translations mainly analytical articles, so important for us is the study of the specifics of the use of this technique in the body of mass communication.

The purpose of using this technique in a media is to attract the reader’s attention and provide aesthetic (in particular comic) effects by intentional violation of linguistic norms. These violations are not errors, showing ignorance of the rules of language and speech reception, reflecting the extraordinary human ability to use language consciously — in order to beat the comical value or form of the word.

Among the techniques playing upon words accepted to such tricks as play on words, zeugma, occasional usage, modification precedent phenomena and collocations, lexical repetition, etc.

Zeugma — is the ratio of one word at a time to the other two in different semantic plans, the comic effect is achieved due to the lack of consistency of the sentence, for example, Wildfires in Russia devastate forests and pockets.

Nonce words — a word formed «on occasion» in the specific conditions of speech communication and, as a rule, contrary to the linguistic norm, deviating from the conventional ways of forming words in a given language. Occasionalism usually appears in the speech as a means playing upon words, for example, Indianomics, Gazpromia.

Referring to the definition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, a pun we understand «stylistic turn of phrase or author’s miniature, based on the comic usage of the same-sounding words that have different meanings, or similar-sounding words or groups of words, or different meanings of the same word or the phrase «[1]. The most frequent types are lexical (In Russia, cold is a matter of degree, Chavez Visit to Russia: Infected by VIRUS) and phraseological puns (Leeches: Fresh Blood for Russia’s Economy).

The main ways of creating playing upon words in a media we believe to be the repetition of word units or parts their parts (Some Bullshit Happening Somewhere; Tough Calls, Good Calls), a modification of precedent texts (The Axis Of Anarchy, The Silence of Mr. Medvedev), and pun as well (Sour notes before Russia’s big moment on stage, Polishing up the relationship).

Often, in order to improve and enhance the expressiveness of pragmatic effects on the recipient’s author uses several techniques playing upon words. For example, the title The Specter of Finlandization used occasionalism «Finlandization», while the title is an allusion to the whole which later became the first winged phrase «Communist Manifesto» written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, «The Specter of Communism».

Numerous studies methods of language games allow to conclude that the lexical-semantic tools and principles of their construction in different languages are similar. Only different degree of efficiency of a receiving language game by virtue of languages belonging to different types. For example, because of syntactic features of English and Russian languages zeugma was more common in the English language. Refer to the following example: Robin Hood Fires His Guns and Top Officials- — Robin Hood shoots right through and dismisses the large «cones»

The author of the article says that the D.A. Medvedev as president of Russia, dismissed a large number of officials, unable to perform their duties. The title is quite expressive, since it uses several stylistic devices — antonomasia and zeugma. When translating Zeugma author can not save zeugma design, and he uses the device of partial compensation, introducing an element of conversation — «big shot.» Partial compensation is often addressed while the translation of game titles that are based on lexical repetition: Breaking News: Some Bullshit Happening Somewhere — Newsflash: Around garbage. In this example, the partial compensation is achieved through the use of rhyme. When translating nonce words, the most productive transcription, transliteration, tracing, functional replacement, descriptive translation, ptosis. Article entitled Indianomics — Indianomika highlights the current state of the Indian economy. Occasionalism Indianomics, formed by way of contamination toponym «India» and common noun «economics» translated by receiving tracing.

100 days: Living in Obamaland — One hundred days in Obamalende

«Obamaland» — occasionalism formed by adding the proper name — the names of the President of the United States and the common noun «land». In this case, the translator uses transcription.

When translated into Russian puns are equally misplaces with omission and compensation.

For example, Pipelines and pipe dreams — Pipes and pipe dreams

This article tells about the opening of a new pipeline, exporting East Siberian oil to China at a fairly high prices, as well as Russia’s desire to take an advantageous position, which will allow it to dictate prices, volumes and related supplies to consumers political conditions in the East and the West. In this case, the translator can not restore phrasebook pun, and using omission, he creates a stylistically neutral title.

Against the grain- Grain block

When translating this phraseological pun it was used full compensation

change in the type of pun. The basis of the formation of the pun idiom is against the grain, which has its own value in itself unusual manner, against the grain. But, as the article describes the «protracted» Russian ban on grain exports, which caused regular disagreements between the US and Russia, after reading it becomes clear that beat element is the word «grain» in its literal meaning — «grain».

A huge number of English-language titles are the result of the transformation of precedent phenomena: idioms, proverbs, sayings, catch phrase, titles of movies, literary, historical phenomena. The transformation of the original case phenomena in most cases is to replace one of the elements of the original on the other hand, significant for the content of the article, and in modified form, they are easily recognizable and at the same time expressive. When translating the following methods:

— Equivalent translation

All Roads Lead to Istanbul — All roads lead to Istanbul;

Beware PR men bearing dictators’ gifts — Fear PR dictators bearing gifts;

— Analog translation

Analysis: Two’s a crowd as Russian state banks squeeze rivals — Among Russian banks odd man out

Thus, the translation of the English game titles is a very difficult task, because the translator must create the most expressive, bright and concise title and try to save the component playing upon words. Translating headlines in Russian are used in virtually all types of lexical and grammatical transformation. The translation should reflect connection of the heading with the text of articles set out in the original language.

III. Practical part

Analysis of the use of «Pun» in English headlines

During the practical analysis of the material were analyzed following publications:

New York Post

The New York Times

The Moscow Times

The Times

The Wall Street Journal

USA Today

The Sun

The Sunday Times

The Daily Telegraph

The Observer

The Irish Times

These publications were analyzed in terms of identifying them in the newspaper headlines containing puns. Then there were two groups of word games. As the basic operation of the first group is the principle of semantic associations in the same context of different values of one word (polysemy) and the principle of sound monotonous or similarity with existing semantic difference (V.V. Vinogradov, V.S.Vinogradov, V.Z.Sannikov, Hiebert , Hausmann, Reiners, Techa). In accordance with the last principle we different 4 types of word games, built on the basis of:

1) homonyms (same phonetics and graphics expressed by the parties)

2) homophony (phonetics match, graphic design is different)

3) homography (the same graphic design, phonetic — Miscellaneous)

4) paronymy (phonetics and graphics available with contrast detect similarities).

Based on this classification, all the headlines were divided into clusters listed in the table

|

Title |

Newspaper |

Cluster |

Analysis |

|

Burning questions on tunnel safety unanswered |

The Guardian |

Paronym |

Игра слов в этом случае находится в словах Burning questions (горящие вопросы). Вопросы об огнях, следовательно, горящие вопросы, но горящий вопрос – это еще один способ сказать о важности и неотложности его решения. |

|

A shot in the dark |

The Guardian |

Paronym |

Игра слов — A shot in the dark. Прямое значение-выстрел в темноте. Но A shot in the dark также означает догадку наобум (Definition of a shot in the dark from the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary). |

|

On a whinge and a prayer |

The Guardian |

homophone |

Игра слов Whinge (хныкать) and a prayer. Речь идет о Wing and a prayer (Coming in on a wing and a prayer – название песни). |

|

What’s black and white and red (read) all over? |

Techcrunch |

homonym |

Игра слов – red. В сравнении два слова red (красный) и red (прошедшая форма глагола read). Два разных слова, звучание одинаково. |

|

Why are there no aspirin tablets in the jungle? — Because paracetamol! |

The Sun |

homophone |

Игра слов — Because paracetamol. (Because parrots eat them all) (The Dictionary); Парацетомол (paracetamol) – название таблеток. |

|

Nigeria: Still standing, but standing still |

The BBC News |

homonym |

Игра слов – Still standing, but standing still. Используется в качестве наречия все еще (в первом случае) и также в качестве наречия во втором случае (спокойно). Также to stand still имеет значение остановиться. |

In the process of data collection and analysis of newspaper headlines there were found many examples of headlines with the replacement of (dies) such as:

1. Science friction. (From The Guardian). Friction (rubbing) — a word used to describe tensions and differences between people, in this case between scientists and the British government. The obvious reference here to science fiction (science fiction); stories about the future or another part of the universe.

2. Between a Bok and a hard place. (From The Guardian). Nicknamed the South African team the Springboks (or Boks). Wordplay — Between a rock and a hard place, which means «in a difficult situation.»

3. Return to gender. (From The Guardian). The term gender (genus) refers to the definition of feminine and masculine. Wordplay — Return to sender (usually placed on the letters, which can not be sent and forwarded to the sender).

4. Silent blight. (From The Guardian). Blight (decline) is a disease. In this case, the disease of the throat teachers, because of which they are forced to remain silent. Link to a Christmas song called Silent Night.

These examples are not included in the classification, based on which the analysis and distribution of the clusters. However, they seem to be interesting to study because are vivid and memorable examples of wordplay in English titles.

After analyzing about 64 headlines and distributing them on the parameters of classification, it was concluded that the British headlines reflect the style of speech and the expression of modern English-speaking people — they are the most compressed and are based on wordplay. In the process of analysis identified the types of headlines, often used as homonyms, homophones, paronyms. The analysis also showed that the titles are not related to any cluster.

IV. Conclusion

Nowadays, newspaper is one of the very well-known types of media. Newspapers must keep attention of the reader and make them read the news. One means of information content and expression — a newspaper headline. As the first signal to induce us to read a newspaper headline should be appropriate and expressive. As guides which focuses our attention on news stories authors use as parts of headings stamps, neologisms, idioms, slang, grammar and syntactic methods attractions.

The effectiveness of newspaper materials is enhanced by the use of their bright, expressive titles. Exceptions are the texts of news information, in which the use of promotional titles is unacceptable. In the language of modern English-language newspaper headlines are characterized by great diversity in terms of their structure, vocabulary, meaning, style that makes it possible to classify them for various reasons: the complexity of the structure, relationship with the text of the article, full of reflection semantic elements of the text.

To draw attention to the headlines journalists use different methods — new words, neologisms, replacing words and idioms. After analyzing about 64 headlines and distributing them on the parameters of classification, it was concluded that the British headlines reflect the style of speech and the expression of modern English-speaking people. Headings are maximally compressed, many of them are based on wordplay. The analysis showed that in headings there are used homonyms, homophones, paronyms. The analysis revealed the headings that do not belong to any cluster, but nevertheless they entered the job as examples of pun.

V. Resources and literature

- Большая Советская энциклопедия: [электронный ресурс]. – URL: http://bse.sci-lib.com/ (дата обращения 19.02.2011)

- Санников В.З. Русский язык в зеркале языковой игры. – М.: Языки русской культуры, 1999. – 544 с.

- [Электронный ресурс]. – URL: http://inosmi.ru/

- Крикунов Ю.А. Сила газетного слова/ Ю.А. Крикунов. — Алма-Ата: 1980, стр. 210

- Лазарева Э. А. Заголовок в газете/ Э.А. Лазарева. — Свердловск, 1989, стр. 115

- Якаменко Н.В. Игра слов в английском языке/ Н.В. Якаменко. – Киев, 1984, стр. 175

VI. Supplement

|

руб. цена работы

+ руб. комиссия сервиса |

Комиссия сервиса является гарантией качества полученного вами результата

Если вас по какой-либо причине не устроит полученная работа — мы вернем вам деньги.

Наша служба поддержки всегда поможет решить любую проблему.

Для того, чтобы купить готовую работу, необходимо иметь на балансе достаточную сумму денег. Все загруженные работы имеют уникальность не менее 50% в общедоступной системе Антиплагиат.ру (модуль интернет). Сразу после покупки работы вы получите ссылку на скачивание файла. Срок скачивания не ограничен по времени. Если работа не соответствует описанию, вы сможете подать жалобу. Гарантийный период 7 дней.

На указанный адрес электронной почты будет отправлена купленная вами готовая работа.

Введите почту получателя купленной работы

Ваша работа успешно отправлена

Нажимая кнопку «Пожаловаться», Вы подтверждаете, что ознакомлены с правилами проверки уникальности готовых работ на сайте. Проверка уникальности работ проводится в общедоступной системе Антиплагиат.ру (модуль Интернет). Пожалуйста, удостоверьтесь, что проверяете уникальность именно в этой системе. Если процент уникальности ниже 50%, то возможен частичный возврат средств пропорционально недостающему проценту. Жалобы о проверке уникальности в другой системе рассматриваться не будут.

When the reader takes in hands the newspaper, the first thing he catches the eye is the headlines.

Headline is the most important component of newspaper information and means of influence. It fixes attention of the reader to the most interesting and important point of article, often without completely opening its essence, than encourages the reader to familiarize with the proposed information in more detail.

- Введение

- Содержание

- Список литературы

- Отрывок из работы

Введение

Newspapers and magazines play a very important role in human life. They help navigate the reality around us, give information concerning events and facts. American Comedian Will Rogers once said, «All I know is what I read in the papers».

The relevance of the research is caused by high socio-cultural significance of headline nowadays.

The research material included examples of 7 English-language newspapers, selected by continuous sampling from newspaper journalistic publications British, American, Irish and Russian media, namely: The Independent, The Guardian, The Daily Mail, The Daily Express, The Times, The New York Times and others.

Содержание

The headline is the first signal, induces us to read the newspaper, or put it aside. Very often sensational and screaming headlines are worthless. The reader is disappointed not only in a separate article or publication, but in the edition in general. The headline is face of all the newspapers, it influences of the popularity.

To create an expression in the headline you can use almost any language means, but the headline should be relevant, expressive. The headline may be invocative, generate in readers some relevance to the publication.

The headlines have some grammatical and syntactical features. In English and American newspapers dominated verb type of headlines: Floods Hit Scotland (Guardian), William Faulkner Is Dead (SBC News), Exports to Russia Are Rising (The Moscow Times). Verb is normally saved in the headlines, consisting of an interrogative sentence: Will There Be Another Major Slump Next Year? (The NY Times). A specific feature of the English title is the ability to omit the subject: Want No War Hysteria in Toronto Schools (Toronto Star), Hits Arrests of Peace Campaigners, etc. (Gardian).

Список литературы

1. Вакуров, В.Н. Стилистика газетных жанров/ В.Н. Вакуров. – М.:Просвещение, 1978, стр. 175

2. Крикунов Ю.А. Сила газетного слова/ Ю.А. Крикунов. — Алма-Ата: 1980, стр. 210

3. Путин А.А. О некоторых особенностях газетных заголовков / А.А. Путин.- Иностранные языки в высшей школе. 1971, стр.65

4. Сизов М.М. Развитие английского газетного заголовка / М.М. Сизов. — М.: Наука, 1984, стр. 131

5. Якаменко Н.В. Игра слов в английском языке/ Н.В. Якаменко. – Киев, 1984, стр. 175

6. Wales, K. 2001. A Dictionary of Stylistics. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2001. pp. 429.

7. Crystal, D. 1995. The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. pp.

8. http://nsportal.ru/shkola/inostrannye-yazyki/angliiskiy-yazyk/library/2013/12/09/igra-slov-v-angliyskikh-gazetnykh#h.2et92p0

Отрывок из работы

During the analysis of the material was analyzed the following publications:

— New York Post

— The New York Times

— The Moscow Times

— The Times

— USA Today

— The Sunday Times

— The Irish Times

These editions were analyzed in terms of identifying in them newspaper headlines containing play on words.

According to the principle of monotonous distinguish four kinds of wordplay, built on the basis of:

1)homonymy (same phonetics and graphics expressed by the parties)

2)homophony (phonetics coincides, graphic design is different)

3)homography (the same graphic design, phonetic is miscellaneous)

4)paronymy (phonetics and graphics at available contrast detect similarities)

The analysis of of newspaper headlines in according to the classification.

Не смогли найти подходящую работу?

Вы можете заказать учебную работу от 100 рублей у наших авторов.

Оформите заказ и авторы начнут откликаться уже через 5 мин!

Here in the UK, we love a good pun.

You’ll probably notice them in tabloid newspaper headlines, but you might also hear them in everyday conversation, emails, social media, television and any number of other situations in which the speaker wishes to present themselves as comical or witty. They’re not the only prevalent form of wordplay you’ll encounter in the English language though; there are plenty more plays on words that contribute to the richness of the spoken and written language. In this article, we start with an introduction to English puns and wordplay and then take you through some of our favourite examples.

What is a pun?

A pun is a form of wordplay that creates humour through the use of a word or series of words that sound the same but that have two or more possible meanings. Puns often make use of homophones – words that sound the same, and are sometimes spelt the same, but have a different meaning. Puns are generally jokes – but not always; we tend to write “no pun intended” in brackets if we’ve inadvertently chosen our words in a way that could be construed as a pun.

As with any kind of comedy, timing is crucial to the telling of a good pun, and if you’re able to think of one on the spot then you’re bound to get a laugh for your ready wit (it won’t look so good if you take several minutes to think of one, by which time the conversation has moved on!). For example, you might be having a conversation about what you had for breakfast, and your friend tells you that they had boiled eggs for breakfast. You could then retort with “were they eggstraordinary?” – accompanied by a cheeky grin in acknowledgement of the poor joke, of course. More subtle and sophisticated puns don’t modify words in this way, but make use of homophones. For example, in a conversation about cooking fish for a dinner party, one might say “do you think we should scale back on the number of guests?” (playing on a fish’s scales and the expression “scale back”, which means to reduce).

Puns have a slightly poor reputation as forms of humour go, and often elicit a groan from the person on the receiving end of one (though that might just be because they wish they’d thought of something that witty to say). They’re generally considered to be a fairly basic form of humour, though they can also be very sophisticated and funny. Shakespeare was famously pretty big on puns; perhaps, it’s recently been suggested, even more so than previously thought; apparently if you read Shakespeare in an Elizabethan accent, you spot many more puns. These days the tabloids are known for their use of puns in headlines; for example, you might see a headline like “Otter Devastation” in an article detailing the decline of the otter (this plays on the similarities between the words “otter” and “utter”).

Other forms of English wordplay

Puns aren’t the only form of English wordplay – they’re just one of the most popular. Here are some of the other kinds of wordplay you might encounter when you’re learning English, whether in everyday conversation, in the newspapers or in works of English literature.

Acronyms

Acronyms involve making a word using the first letters of a series of other words. This type of wordplay is popular in company names. You might not have known, for example, that the popular budget furniture shop IKEA is actually an acronym; it stands for Ingvar Kamprad, Elmtaryd, Agunnaryd. The first two words are the founder’s name, the third the farm on which he spent his childhood, and the fourth his Swedish hometown. “IKEA” has become such a common word in everyday use that very few people know that it stands for something.

Spoonerisms

We accidentally use spoonerisms all the time, to the point where it’s debateable whether they can legitimately classed as ‘wordplay’, with the connotations of intentional wit that that word entails. A spoonerism – named after a chap named Reverend Spooner, who supposedly fell foul of this slip of the tongue frequently – is when you switch some of the letters between two words. For example, you might say “a slight of fairs” instead of “a flight of stairs”. There’s a joke that relies on Spoonerisms:

Question: Why did the butterfly flutter by?

Answer: Because it saw the dragonfly drink the flagon dry.

While this isn’t exactly a laugh-out-loud witticism, it’s an excellent example of the Spoonerism.

Internet abbreviations

Originally intended to make typing a bit quicker, internet abbreviations have almost become a language in their own right – and some abbreviations have actually entered the spoken English language as well. Perhaps the most famous example is “lol”, which means “laughing out loud”. Some people – particularly among the younger generation – now say “lol” out loud, pronouncing it as “loll” (traditionalists frown upon such behaviour, however, so you’re advised to avoid it if you want to be taken seriously).

Portmanteaus

Take part of one word and its meaning, and combine it with another word and its meaning, and you have a portmanteau. For example, the word “brunch” is a portmanteau that combines “breakfast” and “lunch” to create a word for a meal one has in between, and often instead of, breakfast and lunch. Portmanteaus are very popular with tacky gossip magazines, who use them to refer to celebrity couples, such as “Brangelina” for Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie. They were actually popularised by Lewis Carroll, who used the word “portmanteau” for the first time in Alice Through the Looking-Glass.

Alliteration and onomatopoeia

Alliteration is when you use two or more words in a row beginning with the same letter or using the same sounds, and it tends to be used for emphasis or to make something more memorable. You might hear it in a brand name – such as the Automobile Association (AA) – or newspaper headlines, such as “Persecuted for Praying”. You’ll also see it used in English literature, particularly poetry, as it can be helpful for emphasising a point or creating a particular sound. For instance, a piece of writing about a snake might use words beginning with or containing the letter ‘s’, because, when spoken aloud, this echoes the sound a snake makes when it hisses: “the sly snake slithered stealthily”. A similar concept in wordplay is onomatopoeia, which is where a word sounds like what it describes. For example, animal noises are usually onomatopoeic, such as “oink” to describe the noise a pig makes, “moo” for a cow, “woof” for a dog, and so on. This type of wordplay is also common in poetry, as it means that the poet can create certain sounds to add meaning to what they are writing; a poem about fireworks, for example, might allude to the sounds a firework makes using onomatopoeic words, such as “bang”, “crash”, “fizz”, “whoosh”, and so on.

Jokes, headlines and other witticisms involving puns and wordplay

Finally, we give you some more examples of how cunning use of words can make great jokes and newspaper headlines. Puns are particularly popular in tabloid newspaper headlines because they are eye-catching and memorable, drawing attention to a story that might otherwise not spark the curiosity of a passerby.

“Why did the scarecrow…”

Question: Why did the scarecrow win a Nobel Prize?

Answer: For being outstanding in his field!

This excellent joke makes use of clever wordplay to great comic effect, centered around the word “outstanding”. Clearly Nobel laureates are outstanding in their field of expertise, but you wouldn’t expect a scarecrow would be – these are, after all, simply effigies put in fields to scare birds away from crops. But the word “outstanding”, when separated into two words, takes on a different meaning: the scarecrow is “out standing in his field”, meaning that he is “outside, standing in his field”.

A Queen-based headline

A newspaper headline did the rounds on social media a while ago for its clever play on lyrics from the song Bohemian Rhapsody by the rock band Queen in a story about hikes in rail prices. This is explained below with the original lyrics included in italics beneath the headline words.

Is this the rail price?

Is this the real life?

Is this just fantasy?

Is this just fantasy?

Caught up in land buys

Caught in a landslide,

No escape from bureaucracy!

No escape from reality.

This example illustrates an example of witty wordplay that doesn’t involve homophones, and it’s been hailed as headline writing at its very best!

“I wondered why the baseball…”

The joke goes like this: “I was wondering why the baseball was getting bigger. Then it hit me.” The punchline rests on two meanings of the word “hit”. It can mean physically being hit by something being thrown at you, but it can also mean a thought or realisation suddenly occurring to you.

“Why did the fly fly?”

This one’s a staple of the Christmas cracker and makes use of homophones.

Question: Why did the fly fly?

Answer: Because the spider spied her.

The question exploits two meanings of the word “fly”; it’s a small, irritating buzzing insect, but it’s also a verb – “to fly” – meaning to be airborne. The answer relies on the fact that “spied her” – meaning “saw her” – sounds like “spider”.

“What do you call a small midget fortune teller…”

Here’s a joke that’s both groan-worthy and quite clever wordplay.

Question: What do you call a midget fortune teller who just escaped from prison?

Answer: A small medium at large!

The comedy here hinges on the fact that the answer includes the common sizes of small, medium and large, but they all mean different things. A midget is a small person; another word for a fortune teller is “medium”, as in a psychic medium; and when someone has escaped from prison, they’re described as being “at large”.

“A cigarette lighter”

Three men are on board a boat and they have four cigarettes, but nothing to light them with. What do they do? They throw one overboard… so that they become a cigarette lighter!

The humour here relies on the two different interpretations of “cigarette lighter”. Clearly it’s something used to light a cigarette, but the boat itself can also said to be “a cigarette lighter” in weight, because it has shed the weight of one cigarette.

A long joke to end with

Let’s end with a longer joke that relies on clever wordplay for its punchline. This is a popular joke and comes in a number of versions; this particular rendition comes from here.

“The big chess tournament was taking place at the Plaza in New York. After the first day’s competition, many of the winners were sitting around in the foyer of the hotel talking about their matches and bragging about their wonderful play. After a few drinks they started getting louder and louder until finally, the desk clerk couldn’t take any more and kicked them out.

The next morning the Manager called the clerk into his office and told him there had been many complaints about his being so rude to the hotel guests….instead of kicking them out, he should have just asked them to be less noisy. The clerk responded, “I’m sorry, but if there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s chess nuts boasting in an open foyer.”

The punchline at the end – “chess nuts boasting in an open foyer” – is a play on the words of a famous “Christmas Song”, which begins “Chestnuts roasting on an open fire”. “Chess nuts” are people who are “nuts” or crazy about chess; boasting rhymes with roasting; and the “open foyer” that sounds like “open fire” is another word for a reception area. We bet you didn’t realise you could do such clever things with the English language when you first started learning!

Wordle joins an impressive roster of brain bafflers including Spelling Bee and the New York Times crossword.

Dan is a writer on CNET’s How-To team. His byline has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, NBC News, Architectural Digest and elsewhere. He is a crossword junkie and is interested in the intersection of tech and marginalized communities.

Expertise Personal Finance, Government and Policy, Consumer Affairs

Wordle has officially joined the New York Times Games section: The viral word puzzle is now part of a robust portfolio that includes Spelling Bee, Letter Boxed and the legendary New York Times daily crossword.

«If you’ve followed along with the story of Wordle, you’ll know that New York Times Games play a big part in its origins, and so this step feels very natural to me,» Worlde creator Josh Wardle tweeted.

Last year, New York Times Games reached 1 million subscribers, and the paper’s online games were played more than 500 million times.

Here’s everything you need to know about the puzzles in the New York Times Games family, including how to play them.

For more, find out how to start playing Wordle, tips on how to best guess the daily word and how to download Wordle to keep it free forever.

Many Wordle players like to start with words with many vowels

Screenshot by Mark Serrels/CNETWordle

The Times announced it acquired Wordle at the end of January, for an undisclosed sum in the «low seven figures.»

On the off chance you’ve never played, the immensely popular word game gives you six chances to guess a five-letter word.

If the right letter is in the right spot, it shows up in a green box, while a correct letter in the wrong spot shows up in yellow. A letter that isn’t in the word at all shows up gray.

Wordle players have all kinds of strategies — including starter words, like «ADIEU» and «ROATE,» that are heavy on vowels.

And despite complaints, the daily word game has not gotten more difficult since it was purchased by the Times.

«Nothing has changed about the gameplay,» Times’ communications director Jordan Cohen told CNET in an email. In fact, all the words in Wordle for the next five years were written into a script before the game launched in October 2021. (Spoiler: You can view that script on Medium.)

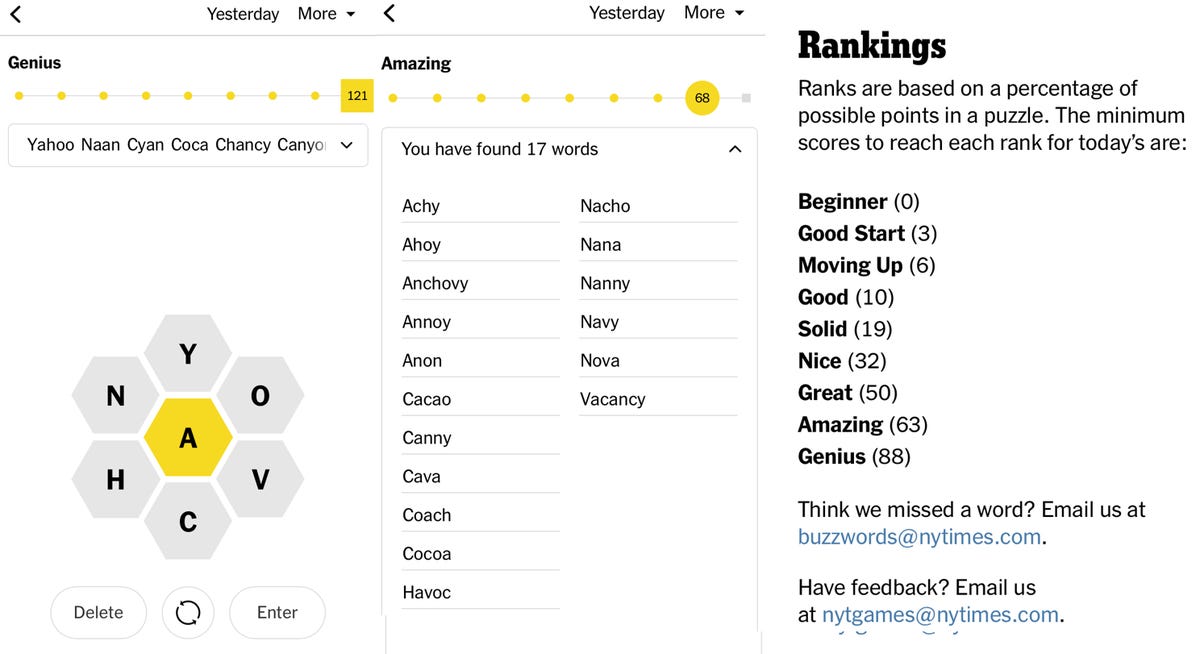

Spelling Bee

Outside of the daily crossword puzzle, Spelling Bee has the most devout following, with a daily column by Isaac Aronow and more than 600 comments a day on average.

Spelling Bee started out as a weekly puzzle in the New York Times magazine before becoming a daily feature on the NYT Games app in 2018.

It’s easy to learn the game but tough to master it: Each puzzle features a seven-cell honeycomb, with six letters arranged around a seventh in the center.

Players simply come up with as many words containing at least four letters as they can. You can reuse letters as often as you want, but each word must contain the center letter.

Words with four letters are worth one point, while longer words receive more. (A «pangram» uses all seven letters at least once. )

Proper nouns aren’t recognized, nor are obscure or obscene words — but exactly what qualifies as obscure is hotly debated through multiple threads.

«Of course, everyone has a different opinion about whether a clue or word is ‘fair,’ and solvers are not afraid to express that,» Wordplay columnist Deb Amlen told CNET. «But don’t all families disagree sometimes?»

The Spelling Bee comment section is filled with gripes and brags, peppered between clues to help struggling members of the Hivemind figure out all the possible words and achieve «Queen Bee» status.

Spelling Bee enthusiast Nancy Pfeffer became so enamored with the game’s online «family» that she embarked on a 5,000-mile cross-country road trip last summer to meet some of her fellow players in person.

«What comes to mind when I think about our solvers is ‘community,’ in the best meaning of the word,» Amlen said.

«I can’t think of any other newspaper games section that draws such a devoted and enthusiastic audience,» she said. «Wordplay commenters have helped and supported each other when personal problems arise. There are local Wordplay groups that meet up in real life to get to know each other. Our games act as a kind of social outlet for like-minded puzzle lovers.»

The game launched as a weekly feature in The New York Times Magazine in 2014 and a daily digital edition debuted four years later.

As of August last year, Spelling Bee has been maintained by Sam Ezersky, who constructs the puzzles, decides what words are acceptable and posts the new game at midnight PT (3 a.m. ET).

And, yes, there are people up at 3 a.m. waiting for the new Bee.

Read on: 10 Tips to Winning the New York Times Spelling Bee

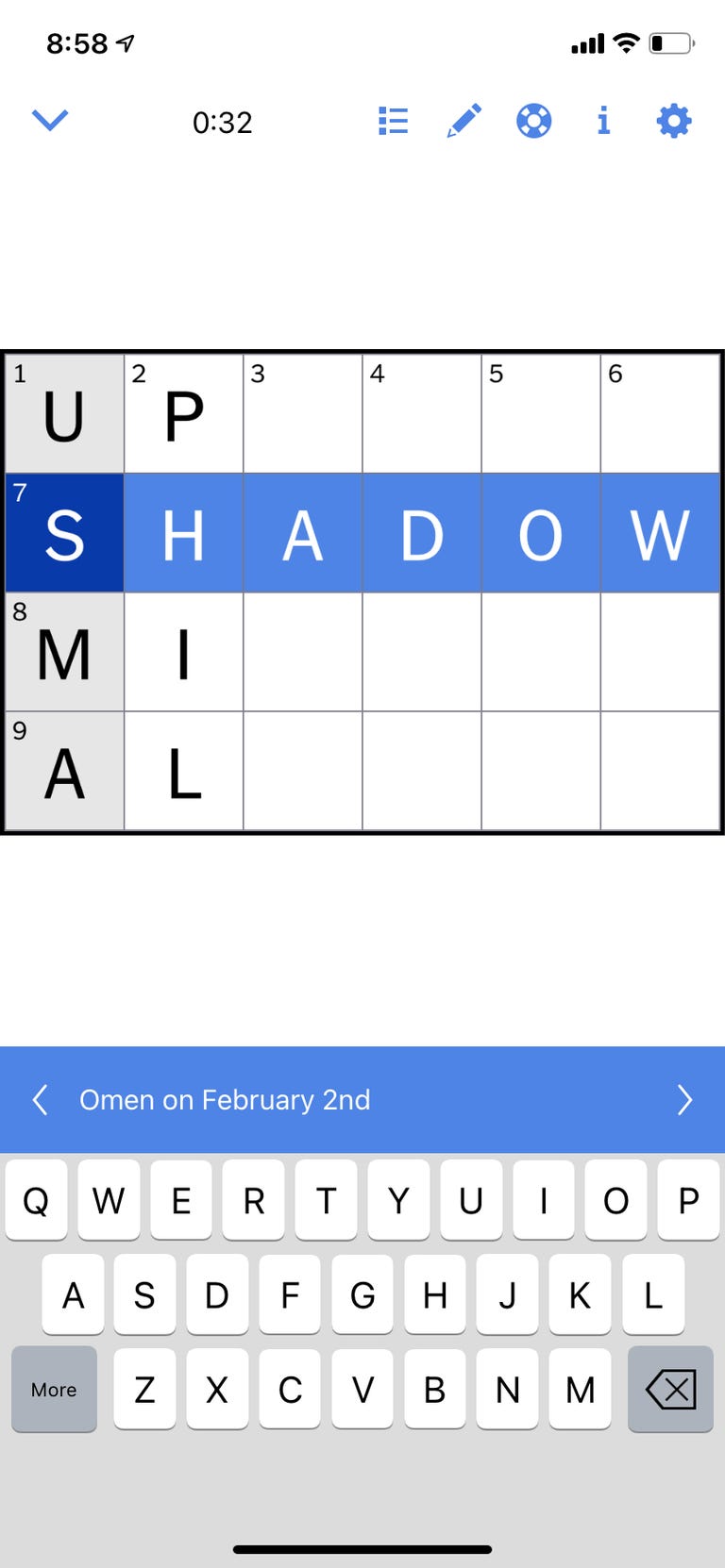

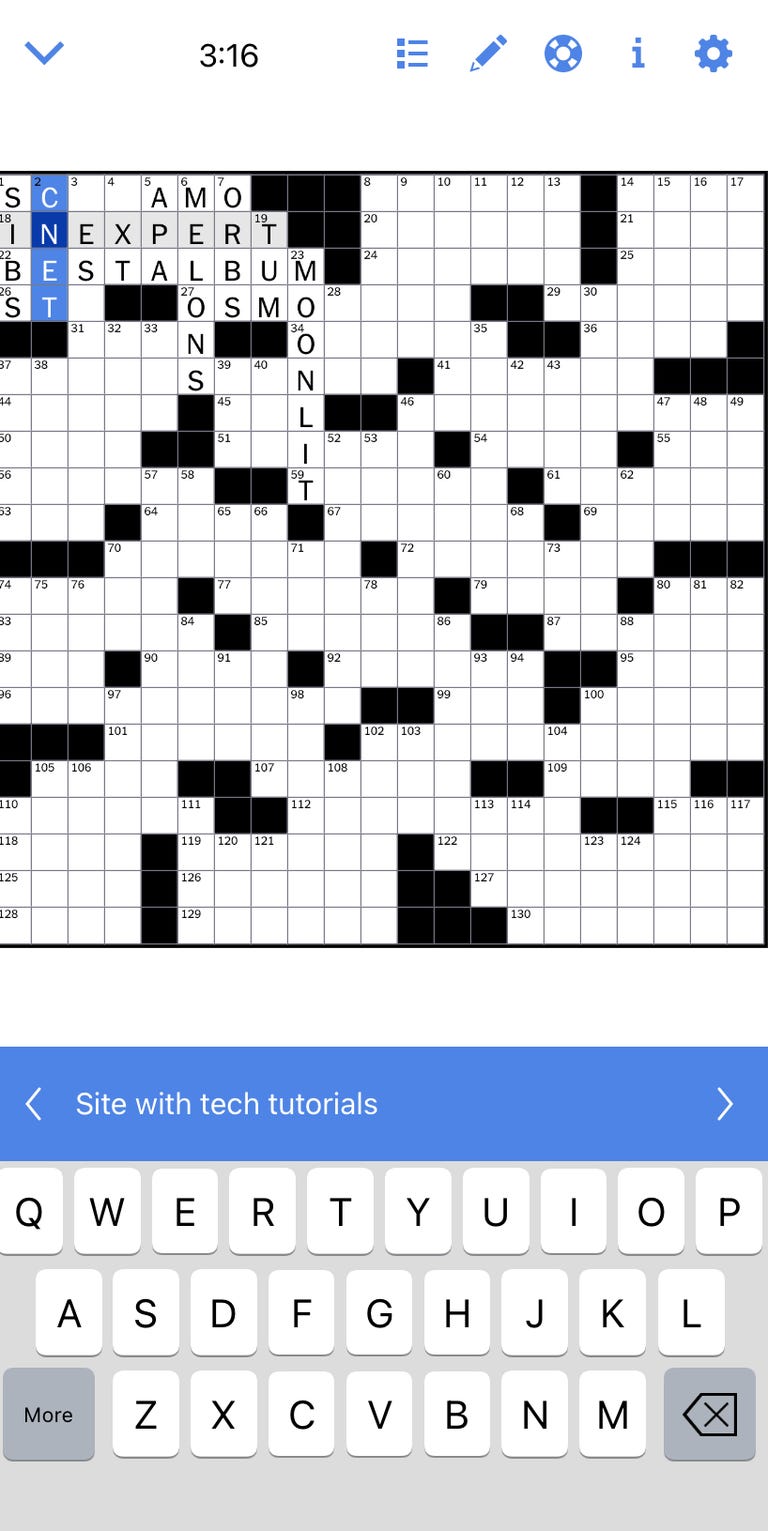

The Mini crossword

The NYT Mini crossword offers a five-by-five grid Sunday through Friday and a seven-by-seven layout on Saturday.

New York Times/Screenshot by Dan Avery/CNETSometimes you don’t have the time, energy or gray matter to work on a full-blown New York Times crossword puzzle. Since 2014, the Times has offered an easier, smaller puzzle, designed by cruciverbalist Joel Fagliano, now digital puzzle editor at the Times.

The Mini is an amuse-bouche of a crossword, with a simple five-by-five grid Sunday through Friday and a seven-by-seven layout on Saturday. (Occasionally larger «midi» puzzles with 11-by-11 layouts pop up, too.)

Even within that limited space, Fagliano has devised something of a formula, as he told the Poynter Institute for Media Studies: «Six or seven clues that are pretty easy, two that are trivia and two that are a bit more cryptic.»

If you’ve been too intimidated to try your hand at a Times crossword, a Mini is definitely a good place to start.

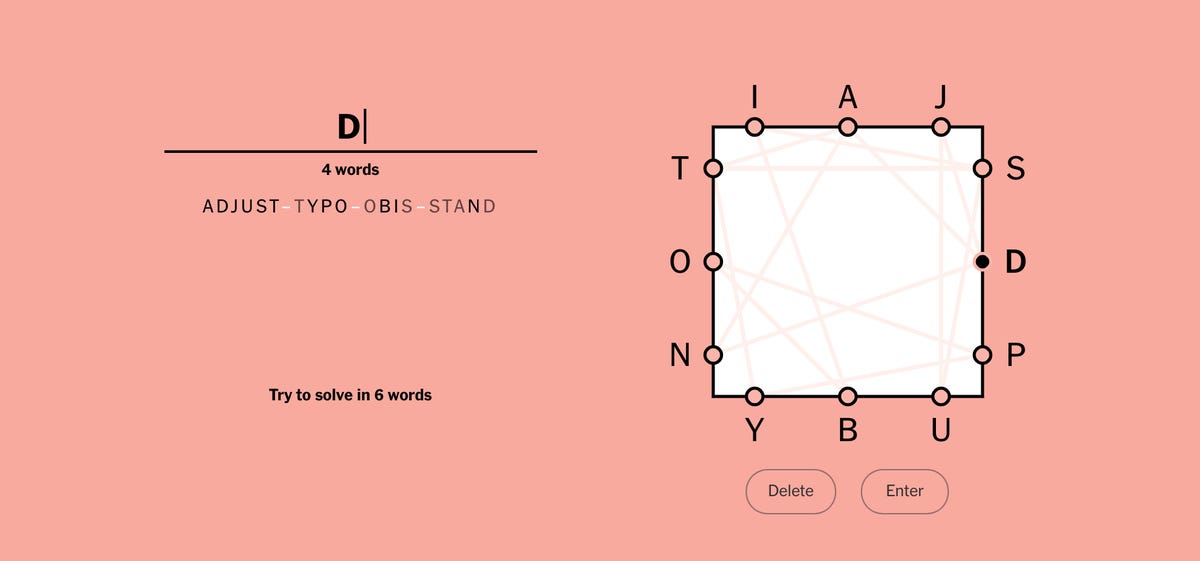

Letter Boxed

Launched in 2019, Letter Boxed, like Spelling Bee, relies more on vocabulary than knowledge of trivia: Three letters are featured on each side of a square and players must connect the letters to make words that are at least three letters long. The final letter of one word becomes the first letter of the next.

The catch, though, is that letters on the same side of the «box» can’t be used consecutively.

The aim is to use all 12 letters by making as few words as possible. But, unlike a crossword, there’s no one route to success. (The Times’ answer to yesterday’s puzzle, as a result, is just labeled «Our Solution.»)

In Letter Boxed, letters on the same side of the square can’t be used consecutively.

New York TimesVertex

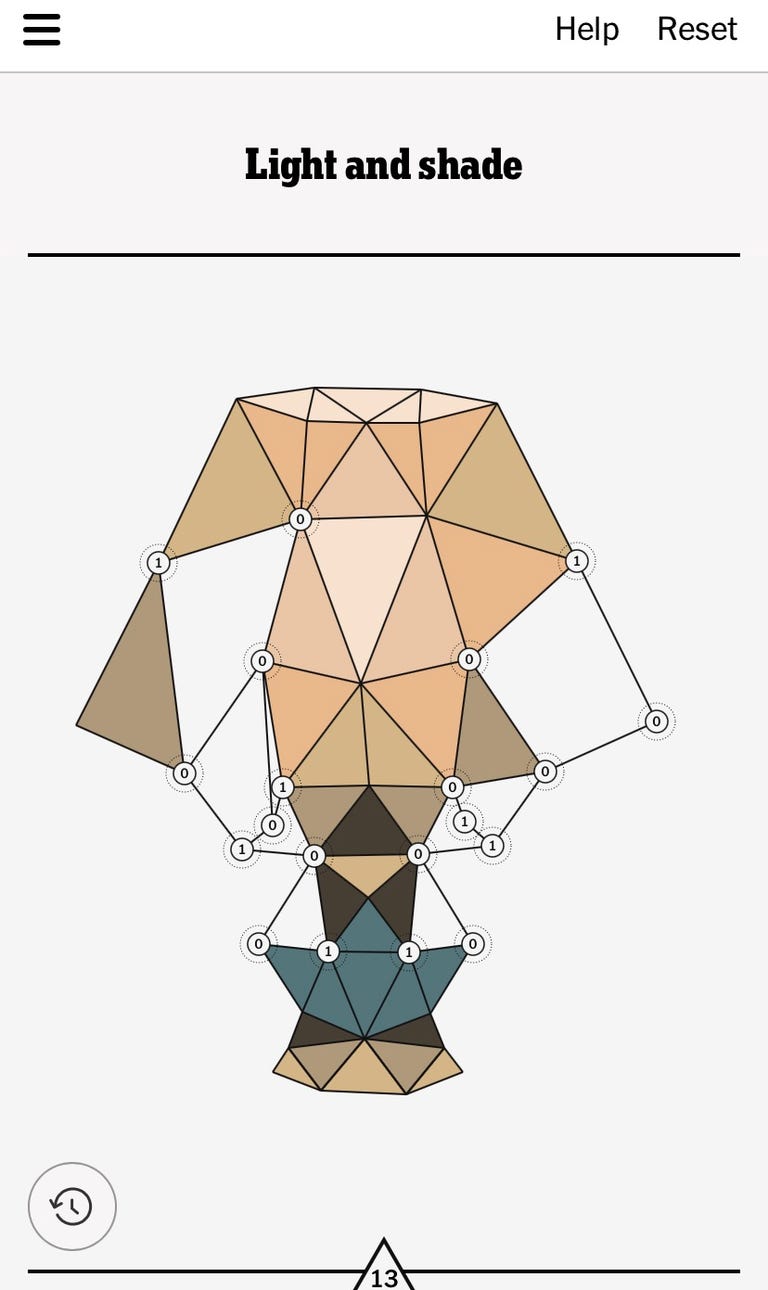

An example of a Vertex puzzle with numerous triangles shaded in giving a glimpse at the finished image hinted at above.

New York Times/Screenshot by Dan Avery/CNETEschewing words altogether, Vertex is an interactive version of a tangram, a Chinese geometric puzzle, that allows users to connect dots to create triangles that ultimately form a larger image.

«At its core, a vertex puzzle is a drawing game with a logic component,» according to an article on the Times website.

The number on a dot indicates how many connections it has to other dots. If you link vertices correctly, the triangle they form will be filled in a specific color.

Tiles

The Times debuted Tiles, its first nonword game, in June 2019. It’s a high-concept, artfully designed take on the classic tile game Mahjong solitaire.

Instead of Chinese characters and symbols, though, users try to match squares featuring intricate patterns — some are inspired by hand-painted Portuguese Azulejo tiles, others by the work of 1970s Op artist Bridget Riley and German color theorist Josef Albers.

A screenshot of a Tiles game.

New York Times/Screenshot by Dan Avery/CNETPlayers click on matching pairs to make them disappear until they’ve cleared the entire board. But the variations in the tile patterns are far more subtle than in traditional Chinese mahjong tiles, making the game significantly more difficult.

Unlike crosswords, which appeal to completists, Tiles is aimed at a more meditative player. In fact, there’s even a «zen mode» that goes on forever without clearing the board.

«One additional strategy around launching Tiles is to reach users who may not be native English-language speakers,» The Times wrote a release announcing the game.

The app version of the famous crossword puzzle.

New York Times/Screenshot by Dan Avery/CNETThe New York Times crossword puzzle

The main draw for Games subscribers is online access to the venerable New York Times crossword puzzle that you can solve on your phone. Not just the current puzzle, but the daily archives going back to November 1993. Subscribers also get access to the new crossword the evening before it appears in print.

The app version of the Times puzzle has an autocheck feature that immediately tells you if you’ve entered the wrong letter. If you’re stuck, you can also have the app «reveal» a square, word or the remainder of the puzzle.

More competitive players can track their solve rate and stats and see how they compare to other players on a leaderboard.

How much is a New York Times Games subscription?

Distinct from the main Times subscription, a New York Times Games digital subscription costs $5 a month or $40 for a year, and includes Spelling Bee, Letter Boxed, Tiles, Vertex and the daily crossword puzzle.

The Times offers the Mini and the logic puzzle Sudoku for free to nonsubscribers. For now, Wordle will also be free for nonsubscribers.

Read more: Finished Wordle? Try one of these similar games

The New York Times crossword puzzle is a daily American-style crossword puzzle published in The New York Times, online on the newspaper’s website, syndicated to more than 300 other newspapers and journals, and on mobile apps.[1][2][3][4][5]

The puzzle is created by various freelance constructors and has been edited by Will Shortz since 1993. The crosswords are designed to increase in difficulty throughout the week, with the easiest puzzle on Monday and the most difficult on Saturday.[6] The larger Sunday crossword, which appears in The New York Times Magazine, is an icon in American culture; it is typically intended to be as difficult as a Thursday puzzle.[6] The standard daily crossword is 15 by 15 squares, while the Sunday crossword measures 21 by 21 squares.[7][8]

History[edit]

Although crosswords became popular in the early 1920s, The New York Times (which initially regarded crosswords as frivolous, calling them «a primitive form of mental exercise») did not begin to run a crossword until 1942, in its Sunday edition.[9][10] The first puzzle ran on Sunday, February 15, 1942. The motivating impulse for the Times to finally run the puzzle (which took over 20 years even though its publisher, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, was a longtime crossword fan) appears to have been the bombing of Pearl Harbor; in a memo dated December 18, 1941, an editor conceded that the puzzle deserved space in the paper, considering what was happening elsewhere in the world and that readers might need something to occupy themselves during blackouts.[10] The puzzle proved popular, and Sulzberger himself authored a Times puzzle before the year was out.[10]

In 1950, the crossword became a daily feature. That first daily puzzle was published without an author line, and as of 2001 the identity of the author of the first weekday Times crossword remained unknown.[11]

There have been four editors of the puzzle: Margaret Farrar from the puzzle’s inception until 1969; Will Weng, former head of the Times‘ metropolitan copy desk, until 1977; Eugene T. Maleska until his death in 1993; and the current editor, Will Shortz. In addition to editing the Times crosswords, Shortz founded and runs the annual American Crossword Puzzle Tournament as well as the World Puzzle Championship (where he remains captain of the US team), has published numerous books of crosswords, sudoku, and other puzzles, authors occasional variety puzzles (also known as «Second Sunday puzzles») to appear alongside the Sunday Times puzzle, and serves as «Puzzlemaster» on the NPR show «Weekend Edition Sunday».[12][13]

The puzzle’s popularity grew over the years, until it came to be considered the most prestigious of the widely circulated U.S. crosswords. Many celebrities and public figures have publicly proclaimed their liking for the puzzle, including opera singer Beverly Sills,[10] author Norman Mailer,[14] baseball pitcher Mike Mussina,[15] former President Bill Clinton,[16] conductor Leonard Bernstein,[10] TV host Jon Stewart,[15] and music duo the Indigo Girls.[15]

The Times puzzles have been collected in hundreds of books by various publishers, most notably Random House and St. Martin’s Press, the current publisher of the series.[17] In addition to appearing in the printed newspaper, the puzzles also appear online on the paper’s website, where they require a separate subscription to access.[18] In 2007, Majesco Entertainment released The New York Times Crosswords game, a video game adaptation for the Nintendo DS handheld. The game includes over 1,000 Times crosswords from all days of the week. Various other forms of merchandise featuring the puzzle have been created, including dedicated electronic crossword handhelds that just contain Times crosswords, and a variety of Times crossword-themed memorabilia, including cookie jars, baseballs, cufflinks, plates, coasters, and mousepads.[17]

Style and conventions[edit]

Will Shortz does not write the Times crossword himself; a wide variety of contributors submit puzzles to him. A full specification sheet listing the paper’s requirements for crossword puzzle submission can be found online or by writing to the paper.

The Monday–Thursday puzzles and the Sunday puzzle always have a theme, some sort of connection between at least three long (usually Across) answers, such as a similar type of pun, letter substitution, or alteration in each entry. Another theme type is that of a quotation broken up into symmetrical portions and spread throughout the grid. For example, the February 11, 2004, puzzle by Ethan Friedman featured a theme quotation: ANY IDIOT CAN FACE / A CRISIS IT’S THIS / DAY-TO-DAY LIVING / THAT WEARS YOU OUT.[19] (This quotation has been attributed to Anton Chekhov, but that attribution is disputed and the specific source has not been identified.) Notable dates such as holidays or anniversaries of famous events are often commemorated with an appropriately themed puzzle, although only two are routinely commemorated annually: Christmas and April Fool’s Day.[20]

The Friday and Saturday puzzles, the most difficult, are usually themeless and «wide open», with fewer black squares and more long words. The maximum word count for a themed weekday puzzle is normally 78 words, while the maximum for a themeless Friday or Saturday puzzle is 72; Sunday puzzles must contain 140 words or fewer.[8] Given the Times‘s reputation as a paper for a literate, well-read, and somewhat arty audience, puzzles frequently reference works of literature, art, or classical music, as well as modern TV, movies, or other touchstones of popular culture.[8]

The puzzle follows a number of conventions, both for tradition’s sake and to aid solvers in completing the crossword:

- Nearly all the Times crossword grids have rotational symmetry: they can be rotated 180 degrees and remain identical. Rarely, puzzles with only vertical or horizontal symmetry can be found; yet rarer are asymmetrical puzzles, usually when an unusual theme requires breaking the symmetry rule. Starting in January 2020, diagonal symmetry began appearing in Friday and Saturday puzzles. This rule has been part of the puzzle since the beginning; when asked why, initial editor Margaret Farrar is said to have responded, «Because it is prettier.»[10]

- Any time a clue contains the tag «abbr.» or an abbreviation more significant than «e.g.», the answer will be an abbreviation (e.g., M.D. org. = AMA).[6]

- Any time a clue ends in a question mark, the answer is a play on words.[6] (e.g., Fitness center? = CORE)

- Occasionally, themed puzzles will require certain squares to be filled in with a symbol, multiple letters, or a word, rather than one letter (so-called «rebus» puzzles). This symbol/letters/word will be repeated in each themed entry. For example, the December 6, 2012, puzzle by Jeff Chen featured a rebus theme based on the chemical pH scale used for acids and bases, which required the letters «pH» to be written together in a single square in several entries (in the middle of entries such as «triumpH» or «sopHocles»).[21]

- French-, Spanish-, or Latin-language answers, and more rarely answers from other languages are indicated either by a tag in the clue giving the answer language (e.g., ‘Summer: Fr.’ = ETE) or by the use in the clue of a word from that language, often a personal or place name (e.g. ‘Friends of Pierre’ = AMIS or ‘The ocean, e.g., in Orleans’ = EAU).[6]

- Clues and answers must always match in part of speech, tense, number, and degree. Thus a plural clue always indicates a plural answer (and the same for singular), a clue in the past tense will always be matched by an answer in the same tense, and a clue containing a comparative or superlative will always be matched by an answer in the same degree.[6]

- The answer word (or any of the answer words, if it consists of multiple words) will not appear in the clue itself. Unlike in some easier puzzles in other outlets, the number of words in the answer is not given in the clue—so a one-word clue can have a multiple-word answer.[22]

- The theme, if any, will be applied consistently throughout the puzzle; e.g., if one of the theme entries is a particular variety of pun, all the theme entries will be of that type.[8]

- In general, any words that might appear elsewhere in the newspaper, such as well-known brand names, pop culture figures, or current phrases of the moment, are fair game.[23]

- No entries involving profanity, sad or disturbing topics, or overly explicit answers should be expected, though some have sneaked in. The April 3, 2006, puzzle contained the word SCUMBAG (a slang term for a condom), which had previously appeared in a Times article quoting people using the word. Shortz apologized and said the term would not appear again.[24][25] PENIS also appeared once in a Shortz-edited puzzle in 1995, clued as «The __ mightier than the sword.»[26]

- Spoken phrases are always indicated by enclosure in quotation marks, e.g., «Get out of here!» = LEAVE NOW.[22]

- Short exclamations are sometimes clued by a phrase in square brackets, e.g., «[It’s cold!]» = BRR.[22]

- When the answer can only be substituted for the clue when preceding a specific other word, this other word is indicated in parentheses. For example, «Think (over)» = MULL, since «mull» only means «think» when preceding the word «over» (i.e., “think over” and «mull over» are synonymous, but «think» and «mull» are not necessarily synonymous otherwise). The point here is that the single word «think» can be replaced by the single word «mull», but only when the following word is «over».

- When the answer needs an additional word in order to fit the clue, this other word is indicated with the use of «with». For example, «Become understood, with in» = SINK, since «Sink in» (but not «Sink» alone) means «to become understood.» The point here is that the single phrase «become understood» can be replaced with the single phrase «sink in», regardless of whether it is followed by anything else.

- Times style is to always capitalize the first letter of a clue, regardless of whether the clue is a complete sentence or whether the first word is a proper noun. On occasion, this is used to deliberately create difficulties for the solver; e.g., in the clue «John, for one», it is ambiguous whether the clue is referring to the proper name John or to the slang term for a bathroom.[22]

Variety puzzles[edit]

Second Sunday puzzles[edit]

In addition to the primary crossword, the Times publishes a second Sunday puzzle each week, of varying types, something that the first crossword editor, Margaret Farrar, saw as a part of the paper’s Sunday puzzle offering from the start; she wrote in a memo when the Times was considering whether or not to start running crosswords that «The smaller puzzle, which would occupy the lower part of the page, could provide variety each Sunday. It could be topical, humorous, have rhymed definitions or story definitions or quiz definitions. The combination of these two would offer meat and dessert, and catch the fancy of all types of puzzlers.»[10] Currently, every other week is an acrostic puzzle authored by Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon, with a rotating selection of other puzzles, including diagramless crosswords, Puns and Anagrams, cryptics (a.k.a. «British-style crosswords»), Split Decisions, Spiral Crosswords, word games, and more rarely, other types (some authored by Shortz himself—the only puzzles he has created for the Times during his tenure as crossword editor).[18] Of these types, the acrostic has the longest and most interesting history, beginning on May 9, 1943, authored by Elizabeth S. Kingsley, who is credited with inventing the puzzle type, and continued to write the Times acrostic until December 28, 1952.[27] From then until August 13, 1967, it was written by Kingsley’s former assistant, Doris Nash Wortman; then it was taken over by Thomas H. Middleton for a period of over 30 years, until August 15, 1999, when the pair of Cox and Rathvon became just the fourth author of the puzzle in its history.[27] The name of the puzzle also changed over the years, from «Double-Crostic» to «Kingsley Double-Crostic,» «Acrostic Puzzle,» and finally (since 1991) just «Acrostic.»[27]

Other puzzles[edit]

As well as a second word puzzle on Sundays, the Times publishes a KenKen numbers puzzle (a variant of the popular sudoku logic puzzles) each day of the week.[18] The KenKen and second Sunday puzzles are available online at the New York Times crosswords and games page, as are «SET!» logic puzzles, a word search variant called «Spelling Bee» in which the solver uses a hexagonal diagram of letters to spell words of four or more letters in length, and a monthly bonus crossword with a theme relating to the month.[18] The Times Online also publishes a daily «mini» crossword by Joel Fagliano, which is 5×5 Sunday through Friday and 7×7 on Saturdays and is significantly easier than the traditional daily puzzle. Other «mini» and larger 11×11 «midi» puzzles are sometimes offered as bonuses.

Records and puzzles of note[edit]

Fans of the Times crossword have kept track of a number of records and interesting puzzles (primarily from among those published in Shortz’s tenure), including those below. (All puzzles published from November 21, 1993, on are available to online subscribers to the Times crossword.)[18]

- Fewest words in a daily 15×15 puzzle: 50 words, on Saturday, June 29, 2013, by Joe Krozel;[28] in a Sunday puzzle: 120 words on August 21, 2022, by Brooke Husic and Will Nediger.[29][30]

- Most words in a daily puzzle: 86 words on Tuesday, December 23, 2008, by Joe Krozel;[28][31] in a 21×21 Sunday puzzle: 150 words, on June 26, 1994, by Nancy Nicholson Joline and on November 21, 1993, by Peter Gordon (the first Sunday puzzle edited by Will Shortz)[29]

- Fewest black squares (in a daily 15×15 puzzle): 17 blocks, on Friday, July 27, 2012, by Joe Krozel[32][33]

- Most prolific author: Manny Nosowsky is the crossword constructor who has been published most frequently in the Times under Shortz, with 241 puzzles (254 including pre-Shortz-era puzzles, published before 1993), although others may have written more puzzles than that under prior editors. The record for most Sunday puzzles is held by Jack Luzzato, with 119 (including two written under pseudonyms);[35] former editor Eugene T. Maleska wrote 110 himself, including 8 under other names.[35]

- Youngest constructor: Daniel Larsen, aged 13 years and 4 months.[36]

- Oldest constructor: Bernice Gordon was 100 on August 11, 2014, when her final Times crossword was published.[37] (She died in 2015 at the age of 101.)[38] Gordon published over 150 crosswords in the Times since her first puzzle was published by Margaret Farrar in 1952.[39]

- Greatest difference in ages between two constructors of a single puzzle: 83, a puzzle by David Steinberg (age 16) and Bernice Gordon (age 99) with the theme AGE DIFFERENCE.[40][41]

- 15-letter-word stacks: On December 29, 2012, Joe Krozel stacked five 15-letter entries, something never before or since achieved. Krozel, Martin Ashwood-Smith, George Barany and Erik Agard have stacked four 15-letter entries in a puzzle. Since 2010, Krozel, Ashwood-Smith, Kevin G. Der, and Jason Flinn have stacked two sets of four 15-letter entries in a puzzle.[42]

- Lowest word count for a debut puzzle: 62 words, on Saturday, June 1, 2019, by Ari Richter.

A few crosswords have achieved recognition beyond the community of crossword solvers. Perhaps the most famous is the November 5, 1996, puzzle by Jeremiah Farrell, published on the day of the U.S. presidential election, which has been featured in the movie Wordplay and the book The Crossword Obsession by Coral Amende, as well as discussed by Peter Jennings on ABC News, featured on CNN, and elsewhere.[12][13][43][44] The two leading candidates that year were Bill Clinton and Bob Dole; in Farrell’s puzzle one of the long clue/answer combinations read «Title for 39-Across next year» = MISTER PRESIDENT. The remarkable feature of the puzzle is that 39-Across could be answered either CLINTON or BOB DOLE, and all the Down clues and answers that crossed it would work either way (e.g., «Black Halloween animal» could be either BAT or CAT depending on which answer you filled in at 39-Across; similarly «French 101 word» could equal LUI or OUI, etc.).[43] Constructors have dubbed this type of puzzle a Schrödinger or quantum puzzle after the famous paradox of Schrödinger’s cat, which was both alive and dead at the same time. Since Farrell’s invention of it, 16 other constructors—Patrick Merrell, Ethan Friedman, David J. Kahn, Damon J. Gulczynski, Dan Schoenholz, Andrew Reynolds, Kacey Walker and David Quarfoot (in collaboration), Ben Tausig, Timothy Polin, Xan Vongsathorn, Andrew Kingsley and John Lieb (in collaboration), Zachary Spitz, David Steinberg and Stephen McCarthy have used a similar trick.[45]

In another notable Times crossword, 27-year-old Bill Gottlieb proposed to his girlfriend, Emily Mindel, via the crossword puzzle of January 7, 1998, written by noted crossword constructor Bob Klahn.[46][47] The answer to 14-Across, «Microsoft chief, to some» was BILLG, also Gottlieb’s name and last initial. 20-Across, «1729 Jonathan Swift pamphlet», was A MODEST PROPOSAL. And 56-Across, «1992 Paula Abdul hit», was WILL YOU MARRY ME. Gottlieb’s girlfriend said yes. The puzzle attracted attention in the AP, an article in the Times itself, and elsewhere.[47] Other Times crosswords with a notable wedding element include the June 25, 2010, puzzle by Byron Walden and Robin Schulman, which has rebuses spelling I DO throughout, and the January 8, 2020, puzzle by Joon Pahk and Amanda Yesnowitz, which was used at the latter’s wedding reception.

On May 7, 2007, former U.S. president Bill Clinton, a self-professed long-time fan of the Times crossword, collaborated with noted crossword constructor Cathy Millhauser on an online-only crossword in which Millhauser constructed the grid and Clinton wrote the clues.[16][48] Shortz described the President’s work as «laugh out loud» and noted that he as editor changed very little of Clinton’s clues, which featured more wordplay than found in a standard puzzle.[16][48] Clinton made his print constructing debut on Friday, May 12, 2017, collaborating with Vic Fleming on one of the co-constructed puzzles celebrating the crossword’s 75th Anniversary.[49]

The Times crossword of Thursday, April 2, 2009, by Brendan Emmett Quigley,[50] featured theme answers that all ran the gamut of movie ratings—beginning with the kid-friendly «G» and finishing with adults-only «X» (now replaced by the less crossword-friendly «NC-17»). The seven theme entries were GARY GYGAX, GRAND PRIX, GORE-TEX, GAG REFLEX, GUMMO MARX, GASOLINE TAX, and GENERATION X. In addition, the puzzle contained the clues/answers of «‘Weird Al’ Yankovic’s ‘__ on Jeopardy‘» = I LOST and «I’ll take New York Times crossword for $200, __» = ALEX. What made the puzzle notable is that the prior night’s episode of the US television show Jeopardy! featured video clues of Will Shortz for five of the theme answers (all but GARY GYGAX and GENERATION X) which the contestants attempted to answer during the course of the show.

Controversies[edit]

The Times crossword has been criticized for a lack of diversity in its constructors and clues. Major crosswords like those in the Times have historically been largely written, edited, fact-checked, and test-solved by older white men.[51] Less than 30% of puzzle constructors in the Shortz Era have been women.[52] In the 2010s, only 27% of clued figures were female, and 20% were of minority racial groups.[53]

In January 2019, the Times crossword was criticized for including the racial slur «BEANER» (clued as «Pitch to the head, informally», but also a derogatory slur for Mexicans).[54] Shortz apologized for the distraction this may have caused solvers, claiming that he had never heard the slur before.[55]

In 2022, the Times was criticized after many readers claimed that its December 18 crossword grid resembled a Nazi swastika.[56] Some were particularly upset that the puzzle was published on the first night of Hanukkah.[57] In a statement, the Times said the resemblance was unintentional, stemming from the grid’s rotational symmetry.[58] The Times was also criticized in 2017 and 2014 for crossword grids that resembled a swastika, which it both times defended as a coincidence.[56][59]

See also[edit]

- Wordplay, a 2006 documentary about the crossword

References[edit]

- ^ «New York Times News Service/Syndicate». October 18, 2006. Archived from the original on October 18, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ New York Times Crosswords for BlackBerry

- ^ «Official New York Times Crossword Puzzle Game Released – TouchArcade». Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ New York Times Crosswords for Kindle Fire

- ^ New York Times Crosswords for Barnes and Noble Nook

- ^ a b c d e f Shortz, Will (April 8, 2001). «ENDPAPER: HOW TO; Solve The New York Times Crossword Puzzle». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ «Crossword Puzzle Archive — 1999 — Premium — NYTimes.com». www.nytimes.com. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d «New York Times Specification Sheet». www.cruciverb.com. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ (Unsigned Editorial) «Topics of the Times» The New York Times, November 17, 1924. Retrieved on March 13, 2009. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g Richard F. Shepard «Bambi is a Stag and Tubas Don’t Go ‘Pah-Pah’: The Ins and Outs of Across and Down» The New York Times Magazine, February 16, 1992. Retrieved on March 13, 2009.

- ^ Will Shortz «150th Anniversary: 1851–2001; The Addiction Begins» The New York Times, November 14, 2001. Retrieved on 2009-13-13.

- ^ a b Author unknown. «A Puzzling Occupation: Will Shortz, Enigmatologist» Biography of Will Shortz from American Crossword Puzzle Tournament homepage, dated March 1998. Retrieved on 2009-03-13.

- ^ a b Leora Baude «Nice Work if You Can Get It», Indiana University College of Arts and Sciences, January 19, 2001. Retrieved on March 13, 2009.

- ^ Will Shortz «CROSSWORD MEMO; What’s in a Name? Five Letters or Less» The New York Times, March 9, 2003. Retrieved on March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c David Germain «Crossword guru Shortz brings play on words to Sundance» Associated Press, January 23, 2006. Retrieved on March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c «Bill Clinton pens NY Times’ crossword puzzle» Reuters 2007-05-07. Retrieved on 2009-03-13.

- ^ a b New York Times store – crossword books

- ^ a b c d e The New York Times crossword puzzle online (subscription required)

- ^ «Thumbnails». XWordInfo. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Account of 2008 presentation by Will Shortz. Retrieved on 2009-03.13]

- ^ Amlen, Deb (December 5, 2012). «Theme of this Puzzle». «Wordplay» blog. The New York Times. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Amlen, Deb (November 30, 2017). «How to Solve the New York Times Crossword». The New York Times. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ^ Hiltner, Stephen (August 1, 2017). «Will Shortz: A Profile of a Lifelong Puzzle Master». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ New York Times Crossword Forum, April 4, 2006

- ^ Sheidlower, Jesse (April 6, 2006). «The dirty word in 43 Down». Slate Magazine. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ «New York Times crossword for August 27, 1995». Xwordinfo.com. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c History of the Times acrostic puzzle Archived February 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Xwordinfo.com

- ^ a b Xwordinfo.com

- ^ «Sun Aug 21, 2022 NYT crossword by Brooke Husic & Will Nediger». Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ record high 86-word puzzle (subscription required)

- ^ July 27, 2012 puzzle with record low black square count (subscription required)

- ^ .Xwordinfo.com

- ^ Xwordinfo.com

- ^ a b New York Times Crossword «Database»

- ^ Shortz, Will (February 14, 2017). «The Youngest Crossword Constructor in New York Times History». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ Amlen, Deb (January 14, 2014). «Location, Location, Location». Wordplay: The Crossword Blog of The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (January 30, 2015). «Bernice Gordon, Crossword Creator for The Times, Dies at 101». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- ^ Mucha, Peter. «Construction worker Bernice Gordon, 95, has been coming across with downright nifty crossword puzzles for 60 years». The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- ^ «New York Times, Wednesday, June 26, 2013». XWord Info. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ Amlen, Deb (June 25, 2013). «Four Score and Three». Wordplay, The Crossword Blog of the New York Times. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ Horne, Jim. «Stacks». XWordInfo. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ a b Amende, Coral (1996) The Crossword Obsession, Berkley Books: New York ISBN 978-0756790868

- ^ Ali Velshi «Business Unusual: Will Shortz», CNN

- ^ «Quantum». xwordinfo.com. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ January 7, 1998 wedding proposal crossword (subscription required)

- ^ a b James Barron «Two Who Solved the Puzzle of Love», The New York Times, January 8, 1998. Retrieved on October 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Cathy Millhauser (constructor) and Bill Clinton (clues); edited by Will Shortz «Twistin’ the Oldies» The New York Times (web only) 2005-05-07. Retrieved on 2009-03-13. (Bill Clinton’s Times crossword, available via PDF or Java applet.)

- ^ «Friday, May 12, 2017 crossword by Bill Clinton and Victor Fleming». www.xwordinfo.com. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ April 2, 2009 puzzle featured on «Jeopardy!» (subscription required)

- ^ Last, Natan (March 18, 2020). «The Hidden Bigotry of Crosswords». The Atlantic. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ «XWord Info». www.xwordinfo.com. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ «Who’s in the Crossword?». The Pudding. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ Flood, Brian (January 2, 2019). «New York Times apologizes for including racial slur in crossword puzzle: ‘It is simply not acceptable’«. Fox News. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ Welk, Brian (January 2, 2019). «NY Times Crossword Editor Apologizes for ‘Slur’ in New Year’s Day Puzzle». TheWrap. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Kilander, Gustaf (December 19, 2022). «New York Times responds after readers accuse paper of swastika-shaped crossword puzzle». The Independent. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ Silverstein, Joe (December 18, 2022). «NY Times Sunday crossword puzzles readers with swastika shape on Hanukkah: ‘How did this get approved’«. Fox News. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Smith, Ryan (December 19, 2022). «The New York Times speaks out on claims its crossword resembles swastika». Newsweek. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ «‘NYT’ Response to Prior Crossword Swastika Accusations Resurfaces». MSN. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

External links[edit]

- Official website (subscription required)

- «New York Times Crossword Archive». The New York Times. From before 2000c.

- «New York Times Crossword Solver». (Unaffiliated). Archive from 1980 forward.