муниципальное бюджетное общеобразовательное учреждение средняя общеобразовательная школа № 60 имени пятого гвардейского Донского казачьего кавалерийского Краснознаменного Будапештского корпуса Советского района г. Ростова-на-Дону

(МБОУСОШ № 60)

REPORT

PHENOMENON OF PLAYING UPON WORDS IN MASS MEDIA

BY EXAMPLE OF NEWSPAPER HEADLINES

Prepared by:

Dzyubenko Vladislava

Academic supervisor:

Nekrasova T. Yu.

Rostov-on-Don

2015

Contents:

|

3 4 9 13 14 15 |

- Introduction

«Everything that I know is that I see in newspapers. The good reader of all in a year can learn from newspapers everything that most of people learn in the years spent in libraries».

Brian Smith

Object of research is a word-play in English headings.

Relevance of research is caused by the high welfare importance of heading presently.

The aim of research is studying of features of a word-play in newspaper headings.

The novelty of research consists in consecutive studying of modern headings and means of a word-play.

The material of research is examples of 11 English-language newspapers from newspaper publicistic editions of the English, American and Irish press.

- Theoretical part

Currently, the scope of the concept playing upon words includes a huge number of events taking place in literature, media and advertising texts, as well as in everyday speech. The notion of playing upon words relates to the field of speech communication, and playing upon words itself is regarded as «embellishment» speech that «usually has the character of jokes, chats, puns, jokes, etc.» [2, p. 138].

The study was conducted on the material of English titles of publications website Inosmi containing translations mainly analytical articles, so important for us is the study of the specifics of the use of this technique in the body of mass communication.

The purpose of using this technique in a media is to attract the reader’s attention and provide aesthetic (in particular comic) effects by intentional violation of linguistic norms. These violations are not errors, showing ignorance of the rules of language and speech reception, reflecting the extraordinary human ability to use language consciously — in order to beat the comical value or form of the word.

Among the techniques playing upon words accepted to such tricks as play on words, zeugma, occasional usage, modification precedent phenomena and collocations, lexical repetition, etc.

Zeugma — is the ratio of one word at a time to the other two in different semantic plans, the comic effect is achieved due to the lack of consistency of the sentence, for example, Wildfires in Russia devastate forests and pockets.

Nonce words — a word formed «on occasion» in the specific conditions of speech communication and, as a rule, contrary to the linguistic norm, deviating from the conventional ways of forming words in a given language. Occasionalism usually appears in the speech as a means playing upon words, for example, Indianomics, Gazpromia.

Referring to the definition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, a pun we understand «stylistic turn of phrase or author’s miniature, based on the comic usage of the same-sounding words that have different meanings, or similar-sounding words or groups of words, or different meanings of the same word or the phrase «[1]. The most frequent types are lexical (In Russia, cold is a matter of degree, Chavez Visit to Russia: Infected by VIRUS) and phraseological puns (Leeches: Fresh Blood for Russia’s Economy).

The main ways of creating playing upon words in a media we believe to be the repetition of word units or parts their parts (Some Bullshit Happening Somewhere; Tough Calls, Good Calls), a modification of precedent texts (The Axis Of Anarchy, The Silence of Mr. Medvedev), and pun as well (Sour notes before Russia’s big moment on stage, Polishing up the relationship).

Often, in order to improve and enhance the expressiveness of pragmatic effects on the recipient’s author uses several techniques playing upon words. For example, the title The Specter of Finlandization used occasionalism «Finlandization», while the title is an allusion to the whole which later became the first winged phrase «Communist Manifesto» written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, «The Specter of Communism».

Numerous studies methods of language games allow to conclude that the lexical-semantic tools and principles of their construction in different languages are similar. Only different degree of efficiency of a receiving language game by virtue of languages belonging to different types. For example, because of syntactic features of English and Russian languages zeugma was more common in the English language. Refer to the following example: Robin Hood Fires His Guns and Top Officials- — Robin Hood shoots right through and dismisses the large «cones»

The author of the article says that the D.A. Medvedev as president of Russia, dismissed a large number of officials, unable to perform their duties. The title is quite expressive, since it uses several stylistic devices — antonomasia and zeugma. When translating Zeugma author can not save zeugma design, and he uses the device of partial compensation, introducing an element of conversation — «big shot.» Partial compensation is often addressed while the translation of game titles that are based on lexical repetition: Breaking News: Some Bullshit Happening Somewhere — Newsflash: Around garbage. In this example, the partial compensation is achieved through the use of rhyme. When translating nonce words, the most productive transcription, transliteration, tracing, functional replacement, descriptive translation, ptosis. Article entitled Indianomics — Indianomika highlights the current state of the Indian economy. Occasionalism Indianomics, formed by way of contamination toponym «India» and common noun «economics» translated by receiving tracing.

100 days: Living in Obamaland — One hundred days in Obamalende

«Obamaland» — occasionalism formed by adding the proper name — the names of the President of the United States and the common noun «land». In this case, the translator uses transcription.

When translated into Russian puns are equally misplaces with omission and compensation.

For example, Pipelines and pipe dreams — Pipes and pipe dreams

This article tells about the opening of a new pipeline, exporting East Siberian oil to China at a fairly high prices, as well as Russia’s desire to take an advantageous position, which will allow it to dictate prices, volumes and related supplies to consumers political conditions in the East and the West. In this case, the translator can not restore phrasebook pun, and using omission, he creates a stylistically neutral title.

Against the grain- Grain block

When translating this phraseological pun it was used full compensation

change in the type of pun. The basis of the formation of the pun idiom is against the grain, which has its own value in itself unusual manner, against the grain. But, as the article describes the «protracted» Russian ban on grain exports, which caused regular disagreements between the US and Russia, after reading it becomes clear that beat element is the word «grain» in its literal meaning — «grain».

A huge number of English-language titles are the result of the transformation of precedent phenomena: idioms, proverbs, sayings, catch phrase, titles of movies, literary, historical phenomena. The transformation of the original case phenomena in most cases is to replace one of the elements of the original on the other hand, significant for the content of the article, and in modified form, they are easily recognizable and at the same time expressive. When translating the following methods:

— Equivalent translation

All Roads Lead to Istanbul — All roads lead to Istanbul;

Beware PR men bearing dictators’ gifts — Fear PR dictators bearing gifts;

— Analog translation

Analysis: Two’s a crowd as Russian state banks squeeze rivals — Among Russian banks odd man out

Thus, the translation of the English game titles is a very difficult task, because the translator must create the most expressive, bright and concise title and try to save the component playing upon words. Translating headlines in Russian are used in virtually all types of lexical and grammatical transformation. The translation should reflect connection of the heading with the text of articles set out in the original language.

III. Practical part

Analysis of the use of «Pun» in English headlines

During the practical analysis of the material were analyzed following publications:

New York Post

The New York Times

The Moscow Times

The Times

The Wall Street Journal

USA Today

The Sun

The Sunday Times

The Daily Telegraph

The Observer

The Irish Times

These publications were analyzed in terms of identifying them in the newspaper headlines containing puns. Then there were two groups of word games. As the basic operation of the first group is the principle of semantic associations in the same context of different values of one word (polysemy) and the principle of sound monotonous or similarity with existing semantic difference (V.V. Vinogradov, V.S.Vinogradov, V.Z.Sannikov, Hiebert , Hausmann, Reiners, Techa). In accordance with the last principle we different 4 types of word games, built on the basis of:

1) homonyms (same phonetics and graphics expressed by the parties)

2) homophony (phonetics match, graphic design is different)

3) homography (the same graphic design, phonetic — Miscellaneous)

4) paronymy (phonetics and graphics available with contrast detect similarities).

Based on this classification, all the headlines were divided into clusters listed in the table

|

Title |

Newspaper |

Cluster |

Analysis |

|

Burning questions on tunnel safety unanswered |

The Guardian |

Paronym |

Игра слов в этом случае находится в словах Burning questions (горящие вопросы). Вопросы об огнях, следовательно, горящие вопросы, но горящий вопрос – это еще один способ сказать о важности и неотложности его решения. |

|

A shot in the dark |

The Guardian |

Paronym |

Игра слов — A shot in the dark. Прямое значение-выстрел в темноте. Но A shot in the dark также означает догадку наобум (Definition of a shot in the dark from the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary). |

|

On a whinge and a prayer |

The Guardian |

homophone |

Игра слов Whinge (хныкать) and a prayer. Речь идет о Wing and a prayer (Coming in on a wing and a prayer – название песни). |

|

What’s black and white and red (read) all over? |

Techcrunch |

homonym |

Игра слов – red. В сравнении два слова red (красный) и red (прошедшая форма глагола read). Два разных слова, звучание одинаково. |

|

Why are there no aspirin tablets in the jungle? — Because paracetamol! |

The Sun |

homophone |

Игра слов — Because paracetamol. (Because parrots eat them all) (The Dictionary); Парацетомол (paracetamol) – название таблеток. |

|

Nigeria: Still standing, but standing still |

The BBC News |

homonym |

Игра слов – Still standing, but standing still. Используется в качестве наречия все еще (в первом случае) и также в качестве наречия во втором случае (спокойно). Также to stand still имеет значение остановиться. |

In the process of data collection and analysis of newspaper headlines there were found many examples of headlines with the replacement of (dies) such as:

1. Science friction. (From The Guardian). Friction (rubbing) — a word used to describe tensions and differences between people, in this case between scientists and the British government. The obvious reference here to science fiction (science fiction); stories about the future or another part of the universe.

2. Between a Bok and a hard place. (From The Guardian). Nicknamed the South African team the Springboks (or Boks). Wordplay — Between a rock and a hard place, which means «in a difficult situation.»

3. Return to gender. (From The Guardian). The term gender (genus) refers to the definition of feminine and masculine. Wordplay — Return to sender (usually placed on the letters, which can not be sent and forwarded to the sender).

4. Silent blight. (From The Guardian). Blight (decline) is a disease. In this case, the disease of the throat teachers, because of which they are forced to remain silent. Link to a Christmas song called Silent Night.

These examples are not included in the classification, based on which the analysis and distribution of the clusters. However, they seem to be interesting to study because are vivid and memorable examples of wordplay in English titles.

After analyzing about 64 headlines and distributing them on the parameters of classification, it was concluded that the British headlines reflect the style of speech and the expression of modern English-speaking people — they are the most compressed and are based on wordplay. In the process of analysis identified the types of headlines, often used as homonyms, homophones, paronyms. The analysis also showed that the titles are not related to any cluster.

IV. Conclusion

Nowadays, newspaper is one of the very well-known types of media. Newspapers must keep attention of the reader and make them read the news. One means of information content and expression — a newspaper headline. As the first signal to induce us to read a newspaper headline should be appropriate and expressive. As guides which focuses our attention on news stories authors use as parts of headings stamps, neologisms, idioms, slang, grammar and syntactic methods attractions.

The effectiveness of newspaper materials is enhanced by the use of their bright, expressive titles. Exceptions are the texts of news information, in which the use of promotional titles is unacceptable. In the language of modern English-language newspaper headlines are characterized by great diversity in terms of their structure, vocabulary, meaning, style that makes it possible to classify them for various reasons: the complexity of the structure, relationship with the text of the article, full of reflection semantic elements of the text.

To draw attention to the headlines journalists use different methods — new words, neologisms, replacing words and idioms. After analyzing about 64 headlines and distributing them on the parameters of classification, it was concluded that the British headlines reflect the style of speech and the expression of modern English-speaking people. Headings are maximally compressed, many of them are based on wordplay. The analysis showed that in headings there are used homonyms, homophones, paronyms. The analysis revealed the headings that do not belong to any cluster, but nevertheless they entered the job as examples of pun.

V. Resources and literature

- Большая Советская энциклопедия: [электронный ресурс]. – URL: http://bse.sci-lib.com/ (дата обращения 19.02.2011)

- Санников В.З. Русский язык в зеркале языковой игры. – М.: Языки русской культуры, 1999. – 544 с.

- [Электронный ресурс]. – URL: http://inosmi.ru/

- Крикунов Ю.А. Сила газетного слова/ Ю.А. Крикунов. — Алма-Ата: 1980, стр. 210

- Лазарева Э. А. Заголовок в газете/ Э.А. Лазарева. — Свердловск, 1989, стр. 115

- Якаменко Н.В. Игра слов в английском языке/ Н.В. Якаменко. – Киев, 1984, стр. 175

VI. Supplement

|

руб. цена работы

+ руб. комиссия сервиса |

Комиссия сервиса является гарантией качества полученного вами результата

Если вас по какой-либо причине не устроит полученная работа — мы вернем вам деньги.

Наша служба поддержки всегда поможет решить любую проблему.

Для того, чтобы купить готовую работу, необходимо иметь на балансе достаточную сумму денег. Все загруженные работы имеют уникальность не менее 50% в общедоступной системе Антиплагиат.ру (модуль интернет). Сразу после покупки работы вы получите ссылку на скачивание файла. Срок скачивания не ограничен по времени. Если работа не соответствует описанию, вы сможете подать жалобу. Гарантийный период 7 дней.

На указанный адрес электронной почты будет отправлена купленная вами готовая работа.

Введите почту получателя купленной работы

Ваша работа успешно отправлена

Нажимая кнопку «Пожаловаться», Вы подтверждаете, что ознакомлены с правилами проверки уникальности готовых работ на сайте. Проверка уникальности работ проводится в общедоступной системе Антиплагиат.ру (модуль Интернет). Пожалуйста, удостоверьтесь, что проверяете уникальность именно в этой системе. Если процент уникальности ниже 50%, то возможен частичный возврат средств пропорционально недостающему проценту. Жалобы о проверке уникальности в другой системе рассматриваться не будут.

When the reader takes in hands the newspaper, the first thing he catches the eye is the headlines.

Headline is the most important component of newspaper information and means of influence. It fixes attention of the reader to the most interesting and important point of article, often without completely opening its essence, than encourages the reader to familiarize with the proposed information in more detail.

- Введение

- Содержание

- Список литературы

- Отрывок из работы

Введение

Newspapers and magazines play a very important role in human life. They help navigate the reality around us, give information concerning events and facts. American Comedian Will Rogers once said, «All I know is what I read in the papers».

The relevance of the research is caused by high socio-cultural significance of headline nowadays.

The research material included examples of 7 English-language newspapers, selected by continuous sampling from newspaper journalistic publications British, American, Irish and Russian media, namely: The Independent, The Guardian, The Daily Mail, The Daily Express, The Times, The New York Times and others.

Содержание

The headline is the first signal, induces us to read the newspaper, or put it aside. Very often sensational and screaming headlines are worthless. The reader is disappointed not only in a separate article or publication, but in the edition in general. The headline is face of all the newspapers, it influences of the popularity.

To create an expression in the headline you can use almost any language means, but the headline should be relevant, expressive. The headline may be invocative, generate in readers some relevance to the publication.

The headlines have some grammatical and syntactical features. In English and American newspapers dominated verb type of headlines: Floods Hit Scotland (Guardian), William Faulkner Is Dead (SBC News), Exports to Russia Are Rising (The Moscow Times). Verb is normally saved in the headlines, consisting of an interrogative sentence: Will There Be Another Major Slump Next Year? (The NY Times). A specific feature of the English title is the ability to omit the subject: Want No War Hysteria in Toronto Schools (Toronto Star), Hits Arrests of Peace Campaigners, etc. (Gardian).

Список литературы

1. Вакуров, В.Н. Стилистика газетных жанров/ В.Н. Вакуров. – М.:Просвещение, 1978, стр. 175

2. Крикунов Ю.А. Сила газетного слова/ Ю.А. Крикунов. — Алма-Ата: 1980, стр. 210

3. Путин А.А. О некоторых особенностях газетных заголовков / А.А. Путин.- Иностранные языки в высшей школе. 1971, стр.65

4. Сизов М.М. Развитие английского газетного заголовка / М.М. Сизов. — М.: Наука, 1984, стр. 131

5. Якаменко Н.В. Игра слов в английском языке/ Н.В. Якаменко. – Киев, 1984, стр. 175

6. Wales, K. 2001. A Dictionary of Stylistics. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2001. pp. 429.

7. Crystal, D. 1995. The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. pp.

8. http://nsportal.ru/shkola/inostrannye-yazyki/angliiskiy-yazyk/library/2013/12/09/igra-slov-v-angliyskikh-gazetnykh#h.2et92p0

Отрывок из работы

During the analysis of the material was analyzed the following publications:

— New York Post

— The New York Times

— The Moscow Times

— The Times

— USA Today

— The Sunday Times

— The Irish Times

These editions were analyzed in terms of identifying in them newspaper headlines containing play on words.

According to the principle of monotonous distinguish four kinds of wordplay, built on the basis of:

1)homonymy (same phonetics and graphics expressed by the parties)

2)homophony (phonetics coincides, graphic design is different)

3)homography (the same graphic design, phonetic is miscellaneous)

4)paronymy (phonetics and graphics at available contrast detect similarities)

The analysis of of newspaper headlines in according to the classification.

Не смогли найти подходящую работу?

Вы можете заказать учебную работу от 100 рублей у наших авторов.

Оформите заказ и авторы начнут откликаться уже через 5 мин!

Here in the UK, we love a good pun.

You’ll probably notice them in tabloid newspaper headlines, but you might also hear them in everyday conversation, emails, social media, television and any number of other situations in which the speaker wishes to present themselves as comical or witty. They’re not the only prevalent form of wordplay you’ll encounter in the English language though; there are plenty more plays on words that contribute to the richness of the spoken and written language. In this article, we start with an introduction to English puns and wordplay and then take you through some of our favourite examples.

What is a pun?

A pun is a form of wordplay that creates humour through the use of a word or series of words that sound the same but that have two or more possible meanings. Puns often make use of homophones – words that sound the same, and are sometimes spelt the same, but have a different meaning. Puns are generally jokes – but not always; we tend to write “no pun intended” in brackets if we’ve inadvertently chosen our words in a way that could be construed as a pun.

As with any kind of comedy, timing is crucial to the telling of a good pun, and if you’re able to think of one on the spot then you’re bound to get a laugh for your ready wit (it won’t look so good if you take several minutes to think of one, by which time the conversation has moved on!). For example, you might be having a conversation about what you had for breakfast, and your friend tells you that they had boiled eggs for breakfast. You could then retort with “were they eggstraordinary?” – accompanied by a cheeky grin in acknowledgement of the poor joke, of course. More subtle and sophisticated puns don’t modify words in this way, but make use of homophones. For example, in a conversation about cooking fish for a dinner party, one might say “do you think we should scale back on the number of guests?” (playing on a fish’s scales and the expression “scale back”, which means to reduce).

Puns have a slightly poor reputation as forms of humour go, and often elicit a groan from the person on the receiving end of one (though that might just be because they wish they’d thought of something that witty to say). They’re generally considered to be a fairly basic form of humour, though they can also be very sophisticated and funny. Shakespeare was famously pretty big on puns; perhaps, it’s recently been suggested, even more so than previously thought; apparently if you read Shakespeare in an Elizabethan accent, you spot many more puns. These days the tabloids are known for their use of puns in headlines; for example, you might see a headline like “Otter Devastation” in an article detailing the decline of the otter (this plays on the similarities between the words “otter” and “utter”).

Other forms of English wordplay

Puns aren’t the only form of English wordplay – they’re just one of the most popular. Here are some of the other kinds of wordplay you might encounter when you’re learning English, whether in everyday conversation, in the newspapers or in works of English literature.

Acronyms

Acronyms involve making a word using the first letters of a series of other words. This type of wordplay is popular in company names. You might not have known, for example, that the popular budget furniture shop IKEA is actually an acronym; it stands for Ingvar Kamprad, Elmtaryd, Agunnaryd. The first two words are the founder’s name, the third the farm on which he spent his childhood, and the fourth his Swedish hometown. “IKEA” has become such a common word in everyday use that very few people know that it stands for something.

Spoonerisms

We accidentally use spoonerisms all the time, to the point where it’s debateable whether they can legitimately classed as ‘wordplay’, with the connotations of intentional wit that that word entails. A spoonerism – named after a chap named Reverend Spooner, who supposedly fell foul of this slip of the tongue frequently – is when you switch some of the letters between two words. For example, you might say “a slight of fairs” instead of “a flight of stairs”. There’s a joke that relies on Spoonerisms:

Question: Why did the butterfly flutter by?

Answer: Because it saw the dragonfly drink the flagon dry.

While this isn’t exactly a laugh-out-loud witticism, it’s an excellent example of the Spoonerism.

Internet abbreviations

Originally intended to make typing a bit quicker, internet abbreviations have almost become a language in their own right – and some abbreviations have actually entered the spoken English language as well. Perhaps the most famous example is “lol”, which means “laughing out loud”. Some people – particularly among the younger generation – now say “lol” out loud, pronouncing it as “loll” (traditionalists frown upon such behaviour, however, so you’re advised to avoid it if you want to be taken seriously).

Portmanteaus

Take part of one word and its meaning, and combine it with another word and its meaning, and you have a portmanteau. For example, the word “brunch” is a portmanteau that combines “breakfast” and “lunch” to create a word for a meal one has in between, and often instead of, breakfast and lunch. Portmanteaus are very popular with tacky gossip magazines, who use them to refer to celebrity couples, such as “Brangelina” for Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie. They were actually popularised by Lewis Carroll, who used the word “portmanteau” for the first time in Alice Through the Looking-Glass.

Alliteration and onomatopoeia

Alliteration is when you use two or more words in a row beginning with the same letter or using the same sounds, and it tends to be used for emphasis or to make something more memorable. You might hear it in a brand name – such as the Automobile Association (AA) – or newspaper headlines, such as “Persecuted for Praying”. You’ll also see it used in English literature, particularly poetry, as it can be helpful for emphasising a point or creating a particular sound. For instance, a piece of writing about a snake might use words beginning with or containing the letter ‘s’, because, when spoken aloud, this echoes the sound a snake makes when it hisses: “the sly snake slithered stealthily”. A similar concept in wordplay is onomatopoeia, which is where a word sounds like what it describes. For example, animal noises are usually onomatopoeic, such as “oink” to describe the noise a pig makes, “moo” for a cow, “woof” for a dog, and so on. This type of wordplay is also common in poetry, as it means that the poet can create certain sounds to add meaning to what they are writing; a poem about fireworks, for example, might allude to the sounds a firework makes using onomatopoeic words, such as “bang”, “crash”, “fizz”, “whoosh”, and so on.

Jokes, headlines and other witticisms involving puns and wordplay

Finally, we give you some more examples of how cunning use of words can make great jokes and newspaper headlines. Puns are particularly popular in tabloid newspaper headlines because they are eye-catching and memorable, drawing attention to a story that might otherwise not spark the curiosity of a passerby.

“Why did the scarecrow…”

Question: Why did the scarecrow win a Nobel Prize?

Answer: For being outstanding in his field!

This excellent joke makes use of clever wordplay to great comic effect, centered around the word “outstanding”. Clearly Nobel laureates are outstanding in their field of expertise, but you wouldn’t expect a scarecrow would be – these are, after all, simply effigies put in fields to scare birds away from crops. But the word “outstanding”, when separated into two words, takes on a different meaning: the scarecrow is “out standing in his field”, meaning that he is “outside, standing in his field”.

A Queen-based headline

A newspaper headline did the rounds on social media a while ago for its clever play on lyrics from the song Bohemian Rhapsody by the rock band Queen in a story about hikes in rail prices. This is explained below with the original lyrics included in italics beneath the headline words.

Is this the rail price?

Is this the real life?

Is this just fantasy?

Is this just fantasy?

Caught up in land buys

Caught in a landslide,

No escape from bureaucracy!

No escape from reality.

This example illustrates an example of witty wordplay that doesn’t involve homophones, and it’s been hailed as headline writing at its very best!

“I wondered why the baseball…”

The joke goes like this: “I was wondering why the baseball was getting bigger. Then it hit me.” The punchline rests on two meanings of the word “hit”. It can mean physically being hit by something being thrown at you, but it can also mean a thought or realisation suddenly occurring to you.

“Why did the fly fly?”

This one’s a staple of the Christmas cracker and makes use of homophones.

Question: Why did the fly fly?

Answer: Because the spider spied her.

The question exploits two meanings of the word “fly”; it’s a small, irritating buzzing insect, but it’s also a verb – “to fly” – meaning to be airborne. The answer relies on the fact that “spied her” – meaning “saw her” – sounds like “spider”.

“What do you call a small midget fortune teller…”

Here’s a joke that’s both groan-worthy and quite clever wordplay.

Question: What do you call a midget fortune teller who just escaped from prison?

Answer: A small medium at large!

The comedy here hinges on the fact that the answer includes the common sizes of small, medium and large, but they all mean different things. A midget is a small person; another word for a fortune teller is “medium”, as in a psychic medium; and when someone has escaped from prison, they’re described as being “at large”.

“A cigarette lighter”

Three men are on board a boat and they have four cigarettes, but nothing to light them with. What do they do? They throw one overboard… so that they become a cigarette lighter!

The humour here relies on the two different interpretations of “cigarette lighter”. Clearly it’s something used to light a cigarette, but the boat itself can also said to be “a cigarette lighter” in weight, because it has shed the weight of one cigarette.

A long joke to end with

Let’s end with a longer joke that relies on clever wordplay for its punchline. This is a popular joke and comes in a number of versions; this particular rendition comes from here.

“The big chess tournament was taking place at the Plaza in New York. After the first day’s competition, many of the winners were sitting around in the foyer of the hotel talking about their matches and bragging about their wonderful play. After a few drinks they started getting louder and louder until finally, the desk clerk couldn’t take any more and kicked them out.

The next morning the Manager called the clerk into his office and told him there had been many complaints about his being so rude to the hotel guests….instead of kicking them out, he should have just asked them to be less noisy. The clerk responded, “I’m sorry, but if there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s chess nuts boasting in an open foyer.”

The punchline at the end – “chess nuts boasting in an open foyer” – is a play on the words of a famous “Christmas Song”, which begins “Chestnuts roasting on an open fire”. “Chess nuts” are people who are “nuts” or crazy about chess; boasting rhymes with roasting; and the “open foyer” that sounds like “open fire” is another word for a reception area. We bet you didn’t realise you could do such clever things with the English language when you first started learning!

Puzzles are a relatively recent addition to daily newspapers. The first crossword puzzle appeared in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World only 106 years ago. Here’s a look at how your favorite pastime developed over the years.

The origin of many of today’s newspaper puzzles was a game that was played in China as early as 190 years B.C. Various versions used numbers and symbols and require users to arrange them in a certain order. They called it «Magic Squares.«

In the version played in ancient Pompeii, a player was given a group of words — in Latin, of course — and had to arrange them on a grid so that the words would read the same way across and down.

Among early Americans who were fascinated by Magic Squares: Benjamin Franklin, who created one that was first published in 1767.

1783

Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler devises a game he calls «Latin Squares.» He describes it as a «new kind of Magic Squares.» It’s a grid in which each numeral or symbol can appear only once in each direction. This will evolve into today’s Sudoku.

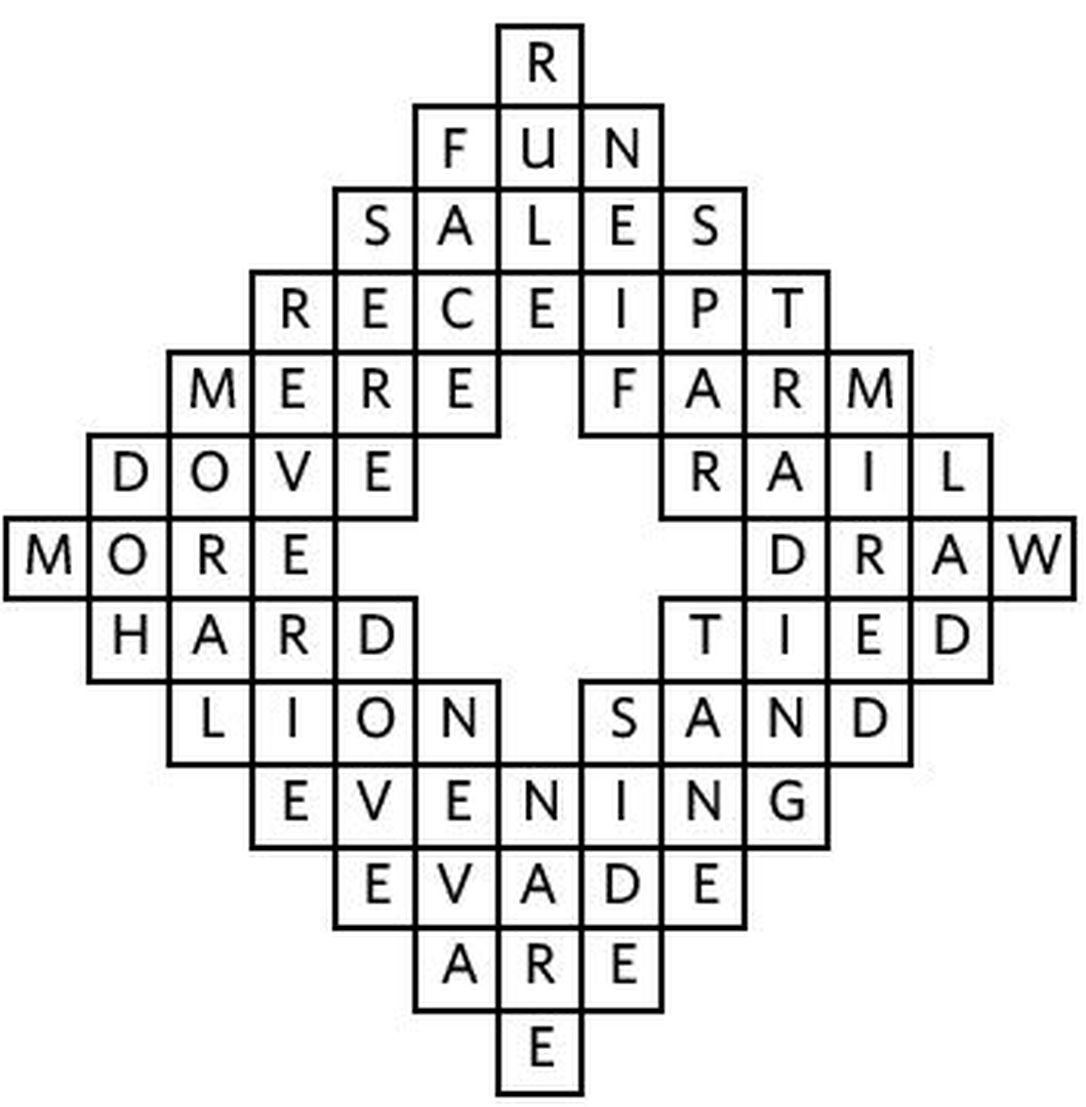

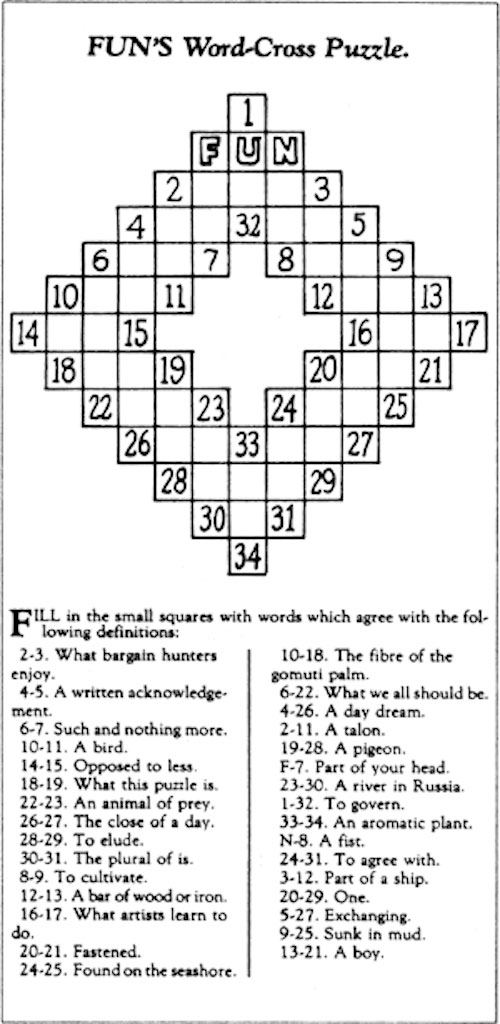

DEC. 21, 1913

The first crossword puzzle — created by Arthur Wynne and called «Word-Cross» — appears in the New York World.

Wynne, a violinist for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, moved to New York to work for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World — at the time, the world’s most visually-oriented newspaper, with pictures, illustrations, infographics and cartoons.

Wynne is asked to come up with a new type of puzzle. He draws inspiration from Magic Squares, turning the game on its ear: He discards the anagram-like aspect and places the words on the page himself — but then hides the words, giving readers clues on how the missing letters are to be filled in.

APRIL 1924

Dick Simon and Lincoln Schuster publish «The Cross Word Puzzle Book» — a collection of puzzles that had run in the New York World and the first-ever book-length collection of crossword puzzles.

By the end of that year, they will have sold more than a million copies — so many that it sets Simon and Schuster on the road to becoming a publishing giant.

NOV. 17, 1924

The New York Times notes the crossword craze overtaking the city and calls them a «primitive sort of mental exercise» and «a sinful waste» of time. «This is not a game at all,» the Times writes, «and it can hardly be called a sport; it merely is a new utilization of leisure by those for whom it would otherwise be empty and tedious.»

FEB. 3, 1925

The New York Evening World runs a story that tells readers «Cross-word puzzles have captivated and possessed New York completely.» It reports that crosswords are a great «brain exercise» and urges readers to give them a try.

The World’s First Crossword Puzzle

Dec. 21, 1913 — New York World

1931

Dell Crossword Puzzles magazine begins publishing crosswords and other puzzles.

FEB. 15, 1942

The New York Times publishes its first crossword puzzle.

NOV. 11, 1950

The New York Times begins publishing a daily crossword puzzle.

1954

Comic book artist Martin Nadel — best known for creating the «golden age» version of the Green Lantern in 1940 — creates the first illustrated «Scramble» puzzle — a series of scrambled words that, when arranged properly, matches a cartoon-illustrated clue.

Nadel would eventually change the feature’s name to «Jumble» and, in 1962, hand off to Henri Arnold and Bob Lee, who would write and draw the puzzle for the next 30 years.

Nadel would go to work for the Leo Burnett advertising agency, where he would play a key role in creating the Pillsbury Doughboy.

March 1, 1968

Norman E. Gibat creates and publishes the first Word Search puzzle in his weekly advertising digest, Selenby (say it out loud: «Sell ’n’ buy»), in Norman, Oklahoma. That first puzzle contained only 34 words — of locations in Oklahoma.

His switchboard lights up as teachers call, wanting extra copies to use in their classes.

1979

Dell begins running new puzzles it calls «Number Place.» It will take them a few years — and a change of name — before they catch on.

1984

Japanese publisher Nikoli takes the Number Place puzzles, makes a few small changes and renames them «Sudoku» — short for the expression «Sūji wa dokushin ni kagiru»: «The digits are limited to one occurrence.»

Sudoku becomes a big hit in Japan, where the alphabet isn’t really suited for crossword puzzles.

March 1997

New Zealand-born retired judge Wayne Gould visits Tokyo, finds a book of Sudoku puzzles and sees potential in the concept. Over the next six years, he develops a computer program he calls Pappocom Sudoku that automatically generates Sudoku puzzles.

Nov. 12, 2004

Gould’s Sudoku puzzle first appear in the Sunday Times of London.

July 2006

Gould publishes his first Sudoku puzzle in the U.S. — in the Daily Sun of Conway, New Hampshire.

Gould’s idea for marketing Sudoku in the U.S.: Give the puzzle away for free to newspapers in exchange for plugging his computer applications and books.

By the end of the year, Gould will have sold more than 4 million Sudoku books.

THE CREATORS OF YOUR FAVORITE PUZZLES

These puzzles The Spokesman-Review brings you don’t grow on trees, you know. They’re created by some of the most clever… well, we hesititate to call them «evil geniuses,» but that’s pretty much what we’re talking about, right?

Tricky Ricky Kane

Wordy Gurdy

«Tricky Ricky Kane» is a pen name for longtime puzzle creator Mark Danna, assistant to the puzzle editor for the Wall Street Journal. He’s published more than 20 word search books and more than 200 crossword puzzles, including two for The Sunday New York Times and he’s the co-writer of Mensa’s Page-A-Day Puzzle Calendar. He also worked as a staff writer for Who Wants to be a Millionaire. Previously, Danna was a professional Frisbee player and won three national Frisbee championships and a national disc golf championship.

David L. Hoyt

Jumble

Word Roundup

Hoyt gave up a career in finance in 1993 to become a full-time puzzle maker. In addition to his most popular feature, Word Roundup, he also creates Jumble Crosswords, TV Jumble, Pat Sajak’s Lucky Letters and USA Today’s Up & Down Words. Hoyt, who lives in Chicago, has created game apps for phones and casino slot machines and scratch-off lottery games. He’s also sold board games to Hasbro and Mattel.

Jeff Knurek

Jumble

Word Roundup

Cartoonist Jeff Knurek is best-known, perhaps, for illustrating the daily Jumble feature — which you can usually find at the bottom right of page two of your daily Spokesman-Review section. Tribune syndicate says the duo reaches more than 70 million readers every day. Knurek lives in Fishers, Indiana, and created the game Spikeball.

Jacqueline E. Mathews

The Daily Commuter

Mathews spent 30 years working for Dell Magazines’ puzzle publications. She founded her own puzzle syndication agency in 1989 and has written four books of word puzzles. The idea behind «The Daily Commuter» puzzle: Clues are more «straightforward» to make this easier for commuters on a bus or train. Mathews also tries to use a bit more humor in her clues. She lives in Everett, Washington.

Will Shortz

The New York Times

Shortz sold his first crossword puzzle at age 14. Two years later, he became a regular contributor to Dell puzzle publications. Shortz attended law school at the University of Virginia but upon graduation, decided to become a full-time puzzle creator instead. He became the crossword editor for The New York Times in 1993. He wrote riddles for the film «Batman Forever» in 1995 and guest-starred in a 2008 episode of «The Simpsons«. He owns and operates the largest table tennis facility in the U.S. near his home in Pleasantville, New York.

Christopher York

7 Little Words

York created his first word game at age 15 with an Atari home computer. He later created 7 Little Words as an electronic game for mobile devices. Apple’s App Store featured the app, which has now been downloaded more than 5 million times. In 2011, 7 Little Words was adapted for use in newspapers. York lives in Caribou, Maine.

Solution for the 1913 Word-Cross Puzzle

Sources:

The New York Times, The Guardian, Bangor Daily News, Time magazine, Andrews McMeel Syndication, Tribune Content Agency, Harper Collins Publishers, WillShortz.com, Sudoku.com, Jumble.com, crosswordtournament.com, RecMath.org, TownePost.com, SporcleBlog, simpsonswiki.com

Is there anything more enjoyable than reading a newspaper on a lazy Sunday morning, outside to the porch where you can bask in the sunshine or to the backyard under the shade of your favorite tree? Wherever you enjoy your morning paper, invite your child to join you with some of these newspaper reading activities!

Remember: any kind of reading will help increase your child’s reading scores and her love of reading. Just spending this kind of quality time will go a long way to helping your child become a lifetime reader.

1. Newspaper Puzzles

Choose a section of the paper you are finished reading and one you think your child will be particularly interested in such as sports or local events. Clip an interesting news story and cut the paragraphs apart. Hand the article to your child in pieces and ask him to read the paragraphs and put the article back together in the proper order. Read the article together and talk about the news story.

2. In My Opinion

Give your child the editorial section and two different colors of highlighter pens. Ask her to highlight all the facts in one color and the opinions in the other color. Talk about the article together. Help your child see that sometimes people with the same facts form different opinions. Also it might be interesting to note that people spout their opinions without any consideration of the facts. Use this time as an opportunity to help children see that forming opinions based on facts makes a lot more sense than just forming opinions for opinion sake.

3. Caption Action

Clip photographs from the newspaper. Don’t include the captions and ask your child to write a caption telling about the picture. It’s okay to make the captions humorous, but make sure your child is noticing details in the photographs so that the captions fit what’s happening in the picture. This is a good way to help your child improve in the important reading skill of finding details.

4. Comic Books

Read the comics with your child. Young children won’t understand most of the comics in a newspaper until they are about ten or eleven years of age. But it is fun to see the first “I get it!” moment when your child understands a comic for the first time. Have your child cut out his favorite comic and glue it on paper to create his own comic book that he can read anytime. Or have your child just cut the pictures from the comics and write her own caption or conversation.

5. Headline Scrabble

The crossword puzzle in the newspaper may be too much of a challenge for your child, but you can create a word game by cutting out the large headlines from the newspaper. Cut the individual letters of the headlines. Then challenge your child to make new words or even a new headline from the letters. Provide paper and glue and allow your child to record her word creations.

6. Take My Advice

Read the advice column of the newspaper with your child. Talk about the problems that are being written about and the answers the columnist gave. Ask your child if they think the advice is good. Then have your child write his or her own advice for the problems. Perhaps your child will want to write about his or her problems in a similar way. Then you can play the role of the columnist. This type of role playing may be the start of some healthy communication between you and your child.

Use these and other ideas you come up with as you take the time to read the paper with your child. If you foster an atmosphere for reading in your home through fun and informal activities such as these, you’ll instill a love of reading in your child that will go beyond the standardize test.