English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- vurd (Bermuda)

- worde (obsolete)

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /wɜːd/

- (General American) enPR: wûrd, IPA(key): /wɝd/

- Rhymes: -ɜː(ɹ)d

- Homophone: whirred (accents with the wine-whine merger)

Etymology 1[edit]

From Middle English word, from Old English word, from Proto-West Germanic *word, from Proto-Germanic *wurdą, from Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dʰh₁om. Doublet of verb and verve; further related to vrata.

Noun[edit]

word (countable and uncountable, plural words)

-

The smallest unit of language that has a particular meaning and can be expressed by itself; the smallest discrete, meaningful unit of language. (contrast morpheme.)

-

1897, Ouida, “The New Woman”, in An Altruist and Four Essays, page 239:

-

But every word, whether written or spoken, which urges the woman to antagonism against the man, every word which is written or spoken to try and make of her a hybrid, self-contained opponent of men, makes a rift in the lute to which the world looks for its sweetest music.

-

-

1986, David Barrat, Media Sociology, →ISBN, page 112:

-

The word, whether written or spoken, does not look like or sound like its meaning — it does not resemble its signified. We only connect the two because we have learnt the code — language. Without such knowledge, ‘Maggie’ would just be a meaningless pattern of shapes or sounds.

-

-

2009, Jack Fitzgerald, Viva La Evolucin, →ISBN, page 233:

-

Brian and Abby signed the word clothing, in which the thumbs brush down the chest as though something is hanging there. They both spoke the word clothing. Brian then signed the word for change, […]

-

-

2013 June 14, Sam Leith, “Where the profound meets the profane”, in The Guardian Weekly, volume 189, number 1, page 37:

-

Swearing doesn’t just mean what we now understand by «dirty words». It is entwined, in social and linguistic history, with the other sort of swearing: vows and oaths. Consider for a moment the origins of almost any word we have for bad language – «profanity», «curses», «oaths» and «swearing» itself.

-

- The smallest discrete unit of spoken language with a particular meaning, composed of one or more phonemes and one or more morphemes

-

1894, Alex. R. Mackwen, “The Samaritan Passover”, in Littell’s Living Age, volume 1, number 6:

-

Then all was silent save the voice of the high priest, whose words grew louder and louder, […]

-

-

1897 December (indicated as 1898), Winston Churchill, chapter IV, in The Celebrity: An Episode, New York, N.Y.: The Macmillan Company; London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd., →OCLC:

-

Mr. Cooke at once began a tirade against the residents of Asquith for permitting a sandy and generally disgraceful condition of the roads. So roundly did he vituperate the inn management in particular, and with such a loud flow of words, that I trembled lest he should be heard on the veranda.

-

- 2006 Feb. 17, Graham Linehan, The IT Crowd, Season 1, Episode 4:

- I can’t believe you want me back.

You’ve got Jen to thank for that. Her words the other day moved me deeply. Very deeply indeed.

Really? What did she say.

Like I remember! Point is it’s the effect of her words that’s important.

- I can’t believe you want me back.

-

- The smallest discrete unit of written language with a particular meaning, composed of one or more letters or symbols and one or more morphemes

-

c. 1599–1602 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, [Act II, scene ii]:

-

Polonius: What do you read, my lord?

Hamlet: Words, words, words.

-

-

2003, Jan Furman, Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon: A Casebook, →ISBN, page 194:

-

The name was a confused gift of love from her father, who could not read the word but picked it out of the Bible for its visual shape, […]

-

-

2009, Stanislas Dehaene, Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read, →ISBN:

-

Well-meaning academics even introduced spelling absurdities such as the “s” in the word “island,” a misguided Renaissance attempt to restore the etymology of the [unrelated] Latin word insula.

-

-

- A discrete, meaningful unit of language approved by an authority or native speaker (compare non-word).

-

1896, Israel Zangwill, Without Prejudice, page 21:

-

“Ain’t! How often am I to tell you ain’t ain’t a word?”

-

-

1999, Linda Greenlaw, The Hungry Ocean, Hyperion, page 11:

-

Fisherwoman isn’t even a word. It’s not in the dictionary.

-

-

-

- Something like such a unit of language:

- Hypernym: syntagma

- A sequence of letters, characters, or sounds, considered as a discrete entity, though it does not necessarily belong to a language or have a meaning

-

1974, Thinking Goes to School: Piaget’s Theory in Practice, →ISBN, page 183:

-

In still another variation, the nonsense word is presented and the teacher asks, «What sound was in the beginning of the word?» «In the middle?» and so on. The child should always respond with the phoneme; he should not use letter labels.

-

-

2003, How To Do Everything with Your Tablet PC, →ISBN, page 278:

-

I wrote a nonsense word, «umbalooie,» in the Input Panel’s Writing Pad. Input Panel converted it to «cembalos» and displayed it in the Text Preview pane.

-

-

2006, Scribal Habits and Theological Influences in the Apocalypse, →ISBN, page 141:

-

Here the scribe has dropped the με from καθημενος, thereby creating the nonsense word καθηνος.

-

-

2013, The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Language, →ISBN, page 91:

-

If M. V. has sustained impairment to a phonological output process common to reading and repetition, we might anticipate that her mispronunciations will partially reflect the underlying phonemic form of the nonsense word.

-

-

- (telegraphy) A unit of text equivalent to five characters and one space. [from 19th c.]

- (computing) A fixed-size group of bits handled as a unit by a machine and which can be stored in or retrieved from a typical register (so that it has the same size as such a register). [from 20th c.]

-

1997, John L. Hennessy; David A. Patterson, Computer Organization and Design, 2nd edition, San Francisco, California: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, Inc., §3.3, page 109:

-

The size of a register in the MIPS architecture is 32 bits; groups of 32 bits occur so frequently that they are given the name word in the MIPS architecture.

-

-

- (computer science) A finite string that is not a command or operator. [from 20th or 21st c.]

- (group theory) A group element, expressed as a product of group elements.

- The fact or act of speaking, as opposed to taking action. [from 9th c].

-

1811, Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility:

-

[…] she believed them still so very much attached to each other, that they could not be too sedulously divided in word and deed on every occasion.

-

-

2004 September 8, Richard Williams, The Guardian:

-

As they fell apart against Austria, England badly needed someone capable of leading by word and example.

-

-

- (now rare outside certain phrases) Something that someone said; a comment, utterance; speech. [from 10th c.]

-

1945 April 1, Sebastian Haffner, The Observer:

-

«The Kaiser laid down his arms at a quarter to twelve. In me, however, they have an opponent who ceases fighting only at five minutes past twelve,» said Hitler some time ago. He has never spoken a truer word.

-

-

2011, David Bellos, Is That a Fish in Your Ear?, Penguin_year_published=2012, page 126:

-

Despite appearances to the contrary […] dragomans stuck rigidly to their brief, which was not to translate the Sultan’s words, but his word.

-

-

2011, John Lehew (senior), The Encouragement of Peter, →ISBN, page 108:

-

In what sense is God’s Word living? No other word, whether written or spoken, has the power that the Bible has to change lives.

-

-

- (obsolete outside certain phrases) A watchword or rallying cry, a verbal signal (even when consisting of multiple words).

-

1592, William Shakespeare, Richard III:

-

Our ancient word of courage, fair Saint George, inspire us with the spleen of fiery dragons!

-

-

c. 1623, John Fletcher and William Rowley, The Maid in the Mill, published 1647, scene 3:

-

I have the word : sentinel, do thou stand; […]

-

-

- (obsolete) A proverb or motto.

-

1499, John Skelton, The Bowge of Court:

-

Among all other was wrytten in her trone / In golde letters, this worde, whiche I dyde rede: / Garder le fortune que est mauelz et bone.

-

-

1646, Joseph Hall, The Balm of Gilead:

-

The old word is, ‘What the eye views not, the heart rues not.’

-

-

- (uncountable) News; tidings [from 10th c.]

-

1945 August 17, George Orwell [pseudonym; Eric Arthur Blair], chapter 1, in Animal Farm […], London: Secker & Warburg, →OCLC:

-

Word had gone round during the day that old Major, the prize Middle White boar, had had a strange dream on the previous night and wished to communicate it to the other animals.

-

-

Have you had any word from John yet?

-

I’ve tried for weeks to get word, but I still don’t know where she is or if she’s all right.

-

- An order; a request or instruction; an expression of will. [from 10th c.]

-

He sent word that we should strike camp before winter.

-

Don’t fire till I give the word

-

Their mother’s word was law.

-

- A promise; an oath or guarantee. [from 10th c.]

-

I give you my word that I will be there on time.

- Synonym: promise

-

- A brief discussion or conversation. [from 15th c.]

-

Can I have a word with you?

-

- (meiosis) A minor reprimand.

-

I had a word with him about it.

-

- (in the plural) See words.

-

There had been words between him and the secretary about the outcome of the meeting.

-

- (theology, sometimes Word) Communication from God; the message of the Christian gospel; the Bible, Scripture. [from 10th c.]

-

Her parents had lived in Botswana, spreading the word among the tribespeople.

- Synonyms: word of God, Bible

-

- (theology, sometimes Word) Logos, Christ. [from 8th c.]

-

1526, [William Tyndale, transl.], The Newe Testamẽt […] (Tyndale Bible), [Worms, Germany: Peter Schöffer], →OCLC, John ]:

-

And that worde was made flesshe, and dwelt amonge vs, and we sawe the glory off yt, as the glory off the only begotten sonne off the father, which worde was full of grace, and verite.

-

- Synonyms: God, Logos

-

Usage notes[edit]

In English and other languages with a tradition of space-delimited writing, it is customary to treat «word» as referring to any sequence of characters delimited by spaces. However, this is not applicable to languages such as Chinese and Japanese, which are normally written without spaces, or to languages such as Vietnamese, which are written with spaces delimiting syllables.

In computing, the size (length) of a word, while being fixed in a particular machine or processor family design, can be different in different designs, for many reasons. See Word (computer architecture) for a full explanation.

Synonyms[edit]

- vocable; see also Thesaurus:word

Derived terms[edit]

- a-word

- action word

- afterword

- b-word

- babble word

- bad word

- bareword

- baseword

- breathe a word

- bug-word

- buzzword

- byword

- c-word

- catchword

- codeword

- compound predicate word

- compound word

- content word

- counterword

- crossword

- curse word

- cuss word

- d-word

- description word

- directed acyclic word graph

- dirty word

- doubleword

- dword

- Dyck word

- empty word

- f-word

- famous last words

- fighting word, fighting words

- five-dollar word

- foreword

- fossil word

- four-letter word

- frankenword

- from the word go

- function word

- g-word

- gainword

- get a word in edgeways, get a word in edgewise

- get the word out

- ghost word

- good as one’s word

- good word

- guideword

- h-word

- halfword

- hard word

- have a quiet word

- have a word

- have a word in someone’s ear

- have a word with oneself

- have words

- headword

- i-word

- in a word

- in so many words

- interword

- joey word

- k-word

- kangaroo word

- keyword

- l-word

- last word, last words

- last-wordism

- loaded word

- loanword

- longword

- Lyndon word

- m-word

- magic word

- measure word

- metaword

- mince words

- multi-word

- mum’s the word

- my word, oh my word

- n-word

- nameword

- non-word

- nonce word

- nonsense word

- octoword

- of one’s word

- one’s word is law

- operative word

- oword

- p-word

- partword

- pass one’s word

- password

- phoneword

- pillow word

- place word

- polyword

- portmanteau word

- power word

- procedure word, proword

- protoword

- purr word

- put in a good word

- put words in someone’s mouth

- quadword

- question word

- qword

- r-word

- reserved word

- root word

- s-word

- safeword

- say the word

- say word one

- semiword

- send word

- sight word

- single-word

- snarl word

- spelling word

- spoken word

- starword

- stop word

- subword

- swear word

- t-word

- take someone’s word for it

- ten-dollar word

- the word is go

- twenty-five cent word

- ur-word

- v-word

- vocabulary word

- vogue word

- w-word

- wake word

- war of words

- watchword

- weasel word

- wh-word

- winged word

- Wonderword

- word association

- word blindness

- word break

- word class

- word cloud

- word count

- word divider

- word for word

- word formation

- word game

- word golf

- word has it

- word is bond

- word ladder

- word method

- Word of Allah

- word of faith

- word of finger

- Word of God, word of God, God’s word

- word of honour

- word of mouth

- Word of Wisdom

- word on the street

- word order

- word problem

- word processing

- word processor

- word salad

- word search

- word space

- word square

- word to the wise

- word wrap

- word-blind

- word-final

- word-hoard

- word-initial

- word-lover

- word-perfect

- word-stock

- word-wheeling

- wordage

- wordbook

- wordbuilding

- wordcraft

- wordfast

- wordfinding

- wordflow

- wordform

- wordful

- wordhood

- wordie

- wording

- wordish

- wordlength

- wordless

- wordlike

- wordlist

- wordlore

- wordly

- wordmark

- wordmeal

- wordmonger

- wordness

- wordnet

- wordplay

- wordpool

- words fail someone

- words of one syllable

- wordscape

- wordshaping

- wordship

- wordsmith

- wordsome

- wordwise

- wordy

- workword

- wug word

Descendants[edit]

- Chinese Pidgin English: word, 𭉉

Translations[edit]

unit of language

- Abkhaz: ажәа (aẑʷa)

- Adyghe: гущыӏ (gʷuśəʼ)

- Afrikaans: woord (af)

- Albanian: fjalë (sq) f, llaf (sq) m

- Ambonese Malay: kata

- Amharic: ቃል (am) (ḳal)

- Arabic: كَلِمَة (ar) f (kalima)

- Egyptian Arabic: كلمة f (kilma)

- Hijazi Arabic: كلمة f (kilma)

- Aragonese: parola (an) f

- Aramaic:

- Hebrew: מלתא c (melthā, meltho)

- Syriac: ܡܠܬܐ c (melthā, meltho)

- Archi: чӏат (čʼat)

- Armenian: բառ (hy) (baṙ)

- Aromanian: zbor, cuvendã

- Assamese: শব্দ (xobdo)

- Asturian: pallabra (ast) f

- Avar: рагӏул (raʻul), рагӏи (raʻi)

- Azerbaijani: söz (az)

- Balinese: kruna

- Bashkir: һүҙ (hüð)

- Basque: hitz, berba

- Belarusian: сло́ва (be) n (slóva)

- Bengali: শব্দ (bn) (śobdo), লফজ (bn) (lôfzô)

- Bikol Central: kataga

- Breton: ger (br) m, gerioù (br) pl

- Bulgarian: ду́ма (bg) f (dúma), сло́во (bg) n (slóvo)

- Burmese: စကားလုံး (my) (ca.ka:lum:), ပုဒ် (my) (pud), ပဒ (my) (pa.da.)

- Buryat: үгэ (üge)

- Catalan: paraula (ca) f, mot (ca) m

- Cebuano: pulong

- Chamicuro: nachale

- Chechen: дош (doš)

- Cherokee: ᎧᏁᏨ (kanetsv)

- Chichewa: mawu

- Chickasaw: anompa

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 詞/词 (ci4)

- Dungan: цы (cɨ)

- Mandarin: 詞/词 (zh) (cí), 單詞/单词 (zh) (dāncí), 詞語/词语 (zh) (cíyǔ)

- Chukchi: вэтгав (vėtgav)

- Chuvash: сӑмах (sămah)

- Classical Nahuatl: tēntli, tlahtōlli

- Crimean Tatar: söz

- Czech: slovo (cs) n

- Danish: ord (da) n

- Dhivehi: ލަފުޒު (lafuzu)

- Drung: ka

- Dutch: woord (nl) n

- Dzongkha: ཚིག (tshig)

- Eastern Mari: мут (mut)

- Egyptian: (mdt)

- Elfdalian: uord n

- Erzya: вал (val)

- Esperanto: vorto (eo)

- Estonian: sõna (et)

- Even: төрэн (törən)

- Evenki: турэн (turən)

- Faroese: orð (fo) n

- Finnish: sana (fi)

- French: mot (fr) m

- Friulian: peraule f

- Ga: wiemɔ

- Galician: palabra (gl) f, verba f, pravoa f, parola (gl) f

- Georgian: სიტყვა (ka) (siṭq̇va)

- German: Wort (de) n

- Gothic: 𐍅𐌰𐌿𐍂𐌳 n (waurd)

- Greek: λέξη (el) f (léxi)

- Ancient: λόγος m (lógos), ῥῆμα n (rhêma), λέξις f (léxis), (Epic) ὄψ f (óps)

- Greenlandic: oqaaseq

- Guerrero Amuzgo: jñ’o

- Gujarati: શબ્દ (gu) m (śabd)

- Haitian Creole: mo

- Hausa: kalma

- Hawaiian: huaʻōlelo

- Hebrew: מילה מִלָּה (he) f (milá), דבר (he) m (davár) (Biblical)

- Higaonon: polong

- Hindi: शब्द (hi) m (śabd), बात (hi) f (bāt), लुग़त m (luġat), लफ़्ज़ m (lafz)

- Hittite: 𒈨𒈪𒅀𒀸 (memiyaš)

- Hungarian: szó (hu)

- Ibanag: kagi

- Icelandic: orð (is) n

- Ido: vorto (io)

- Ilocano: (literally) sao n

- Indonesian: kata (id)

- Ingrian: sana

- Ingush: дош (doš)

- Interlingua: parola (ia), vocabulo

- Irish: focal (ga) m

- Italian: parola (it) f, vocabolo (it) m, termine (it) m

- Japanese: 言葉 (ja) (ことば, kotoba), 単語 (ja) (たんご, tango), 語 (ja) (ご, go)

- Javanese:

- Carakan: ꦠꦼꦩ꧀ꦧꦸꦁ (jv) (tembung)

- Roman: tembung

- K’iche’: tzij

- Kabardian: псалъэ (psaalˢe)

- Kabyle: awal

- Kaingang: vĩ

- Kalmyk: үг (üg)

- Kannada: ಶಬ್ದ (kn) (śabda), ಪದ (kn) (pada)

- Kapampangan: kataya, salita, amanu

- Karachay-Balkar: сёз (söz)

- Karelian: sana

- Kashubian: słowò n

- Kazakh: сөз (kk) (söz)

- Khmer: ពាក្យ (km) (piək), ពាក្យសំដី (piək sɑmdəy)

- Korean: 말 (ko) (mal), 낱말 (ko) (nanmal), 단어(單語) (ko) (daneo), 마디 (ko) (madi)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: وشە (ckb) (wşe)

- Northern Kurdish: peyv (ku) f, bêje (ku) f, kelîme (ku) f

- Kyrgyz: сөз (ky) (söz)

- Ladin: parola f

- Ladino: palavra f, פﭏאבﬞרה (palavra), biervo m

- Lak: махъ (maq)

- Lao: ຄຳ (lo) (kham)

- Latgalian: vuords m

- Latin: verbum (la) n; vocābulum n, fātus m

- Latvian: vārds (lv) m

- Laz: ნენა (nena)

- Lezgi: гаф (gaf)

- Ligurian: paròlla f

- Lingala: nkómbó

- Lithuanian: žodis (lt) m

- Lombard: paròlla f

- Luxembourgish: Wuert (lb) n

- Lü: ᦅᧄ (kam)

- Macedonian: збор (mk) m (zbor), слово (mk) n (slovo) (archaic)

- Malay: kata (ms), perkataan (ms), kalimah (ms)

- Malayalam: വാക്ക് (ml) (vākkŭ), പദം (ml) (padaṃ), ശബ്ദം (ml) (śabdaṃ)

- Maltese: kelma f

- Maori: kupu (mi)

- Mara Chin: bie

- Marathi: शब्द (mr) m (śabda)

- Middle English: word

- Mingrelian: ზიტყვა (ziṭq̇va), სიტყვა (siṭq̇va)

- Moksha: вал (val)

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: үг (mn) (üg)

- Mongolian: ᠦᠭᠡ (üge)

- Moroccan Amazigh: ⴰⵡⴰⵍ (awal)

- Mòcheno: bourt n

- Nahuatl: tlahtolli (nah)

- Nanai: хэсэ

- Nauruan: dorer (na)

- Navajo: saad

- Nepali: शब्द (śabda)

- North Frisian:

- Föhr-Amrum: wurd n

- Helgoland: Wür n

- Mooring: uurd n

- Sylt: Uurt n

- Northern Sami: sátni

- Northern Yukaghir: аруу (aruu)

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: ord (no) n

- Nynorsk: ord (nn) n

- Occitan: mot (oc) m, paraula (oc) f

- Ojibwe: ikidowin

- Okinawan: くとぅば (kutuba)

- Old Church Slavonic:

- Cyrillic: слово n (slovo)

- Glagolitic: ⱄⰾⱁⰲⱁ n (slovo)

- Old East Slavic: слово n (slovo)

- Old English: word (ang) n

- Old Norse: orð n

- Oriya: ଶବ୍ଦ (or) (śôbdô)

- Oromo: jecha

- Ossetian: дзырд (ʒyrd), ныхас (nyxas)

- Pali: pada n

- Papiamentu: palabra f

- Pashto: لغت (ps) (luġat), کلمه (kalimâ)

- Persian: واژه (fa) (vâže), کلمه (fa) (kalame), لغت (fa) (loğat)

- Piedmontese: mòt m, vos f, paròla f

- Plautdietsch: Wuat (nds) n

- Polabian: slüvǘ n

- Polish: słowo (pl) n

- Portuguese: palavra (pt) f, vocábulo (pt) m

- Punjabi: ਸ਼ਬਦ (pa) (śabad)

- Romanian: cuvânt (ro) n, vorbă (ro) f

- Romansch: pled m, plaid m

- Russian: сло́во (ru) n (slóvo)

- Rusyn: сло́во n (slóvo)

- S’gaw Karen: တၢ်ကတိၤ (ta̱ ka toh̄)

- Samoan: ’upu

- Samogitian: žuodis m

- Sanskrit: शब्द (sa) m (śabda), पद (sa) n (pada), अक्षरा (sa) f (akṣarā)

- Santali: ᱨᱳᱲ (roṛ)

- Sardinian: fueddu

- Scots: wird, wurd

- Scottish Gaelic: facal m, briathar m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: ре̑ч f, рије̑ч f, сло̏во n (obsolete)

- Roman: rȇč (sh) f, rijȇč (sh) f, slȍvo (sh) n (obsolete)

- Sicilian: palora (scn) f, parola (scn) f

- Sidamo: qaale

- Silesian: suowo n

- Sindhi: لَفظُ (sd) (lafẓu)

- Sinhalese: වචනය (si) (wacanaya)

- Skolt Sami: sääˊnn

- Slovak: slovo (sk) n

- Slovene: beseda (sl) f

- Somali: eray (so)

- Sorbian:

- Lower Sorbian: słowo n

- Upper Sorbian: słowo n

- Sotho: lentswe

- Southern Sami: baakoe

- Spanish: palabra (es) f, voz f, vocablo (es) m

- Sundanese: ᮊᮨᮎᮕ᮪ (kecap)

- Svan: please add this translation if you can

- Swahili: neno (sw)

- Swedish: ord (sv) n

- Tagalog: salita (tl)

- Tahitian: parau

- Tajik: вожа (tg) (voža), калима (tg) (kalima), луғат (tg) (luġat)

- Tamil: வார்த்தை (ta) (vārttai), சொல் (ta) (col)

- Tatar: сүз (tt) (süz)

- Telugu: పదము (te) (padamu), మాట (te) (māṭa)

- Tetum: liafuan

- Thai: คำ (th) (kam)

- Tibetan: ཚིག (tshig)

- Tigrinya: ቃል (ti) (ḳal)

- Tocharian B: reki

- Tofa: соот (soot)

- Tongan: lea

- Tswana: lefoko

- Tuareg: tăfert

- Turkish: sözcük (tr), kelime (tr)

- Turkmen: söz

- Tuvan: сөс (sös)

- Udmurt: кыл (kyl)

- Ugaritic: 𐎅𐎆𐎚 (hwt)

- Ukrainian: сло́во (uk) n (slóvo)

- Urdu: شبد m (śabd), بات f (bāt), کلمہ (ur) m, لغت (ur) m (luġat), لفظ (ur) m (lafz)

- Uyghur: سۆز (söz)

- Uzbek: soʻz (uz)

- Venetian: paroła f, paròła f, paròla f

- Vietnamese: từ (vi), lời (vi), nhời (vi), tiếng (vi)

- Volapük: vöd (vo)

- Walloon: mot (wa) m

- Waray-Waray: pulong

- Welsh: gair (cy)

- West Frisian: wurd (fy) n

- Western Cham: بۉه ڤنوۉئ

- White Hmong: lo lus

- Wolof: baat (wo)

- Xhosa: igama

- Yagnobi: гап (gap)

- Yakut: тыл (tıl)

- Yiddish: וואָרט (yi) n (vort)

- Yoruba: ó̩ró̩gbólóhùn kan, ọ̀rọ̀

- Yup’ik: qanruyun

- Zazaki: çeku c, kelime (diq) c, qıse (diq) m, qısa f

- Zhuang: cih

- Zulu: igama (zu) class 5/6, uhlamvu class 11/10

telegraphy: unit of text

- Finnish: sana (fi)

- Greek: λέξη (el) f (léxi)

- Maori: kupu (mi)

- Russian: сло́во (ru) n (slóvo)

- Telugu: సంకేత పదము (saṅkēta padamu)

computer science: finite string which is not a command or operator

- Finnish: sana (fi)

- Russian: сло́во (ru) n (slóvo)

fact or act of speaking, as opposed to taking action

- Finnish: sanat (fi) pl

something which has been said

- Arabic: كَلِمَة (ar) f (kalima), كَلَام (ar) m (kalām), قَوْل m (qawl)

- Bulgarian: реч (bg) f (reč)

- Finnish: sana (fi), puhe (fi)

- French: parole (fr) f

- German: Wort (de) n

- Malay: perkataan (ms)

- Maore Comorian: urongozi class 11

- Middle English: word

- Russian: речь (ru) f (rečʹ), слова́ (ru) n pl (slová)

- Zazaki: qıse (diq) c

news, tidings

- Bulgarian: известие (bg) n (izvestie)

- Finnish: uutiset (fi) pl, sana (fi)

- Malay: berita (ms), khabar (ms), kabar

- Maori: pūrongo (mi)

- Middle English: word

- Portuguese: notícias (pt) f

- Russian: весть (ru) f (vestʹ), изве́стие (ru) n (izvéstije), но́вость (ru) f (nóvostʹ)

- Telugu: వార్త (te) (vārta)

promise

- Afrikaans: erewoord

- Albanian: sharje (sq) f

- Armenian: խոսք (hy) (xoskʿ), խոստում (hy) (xostum)

- Breton: ger (br) m

- Bulgarian: обещание (bg) n (obeštanie), дума (bg) f (duma)

- Catalan: paraula (ca) f

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 諾言/诺言 (zh) (nuòyán)

- Czech: slovo (cs) n, slib (cs) m

- Dutch: erewoord (nl) n, woord (nl) n

- Finnish: sana (fi)

- French: parole (fr) f

- Galician: palabra (gl) f

- German: Ehrenwort (de) n

- Greek: λόγος (el) m (lógos)

- Haitian Creole: pawòl

- Hungarian: szó (hu)

- Interlingua: parolaa

- Italian: parola (it) f

- Japanese: 約束 (ja) (やくそく, yakusoku), 誓い (ja) (ちかい, chikai)

- Korean: 말 (ko) (mal), 약속(約束) (ko) (yaksok)

- Lithuanian: žodis (lt) m

- Macedonian: збор (mk) m (zbor)

- Malay: janji (ms)

- Malayalam: വാക്ക് (ml) (vākkŭ)

- Middle English: word

- Norwegian: ord (no) n, lovnad (no) m

- Persian: پیمان (fa) (peymân), قول (fa) (qol)

- Polish: słowo (pl) n

- Portuguese: palavra (pt) f, promessa (pt) f

- Romanian: cuvânt de onoare n

- Russian: сло́во (ru) n (slóvo), обеща́ние (ru) n (obeščánije)

- Slovak: čestné slovo n

- Slovene: častna beseda (sl) f, beseda (sl) f

- Spanish: palabra (es) f

- Swedish: ord (sv) n

- Telugu: మాట (te) (māṭa)

- Zulu: isithembiso class 7/8

brief discussion

- Finnish: pari sanaa

- Ladino: byerveziko

- Malay: perbincangan (ms)

- Maori: matapakinga

- Middle English: word

- Portuguese: palavra (pt) f

- Russian: разгово́р (ru) m (razgovór)

- Telugu: చర్చ (te) (carca)

Christ

- Arabic: كلمة الله

- Burmese: နှုတ်ကပတ်တော်သည် (hnutka.pattausany)

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 道 (zh) (dào)

- Finnish: Sana

- French: Verbe (fr) m, verbe (fr) m

- Hungarian: ige (hu)

- Middle English: word

- Occitan: vèrbe (oc) m, vèrb (oc) m

- Oriya: ବାକ୍ୟ (or) (bakyô)

- Tajik: Калом (Kalom)

- Telugu: దేవుడు (te) (dēvuḍu)

the word of God

- Armenian: բան (hy) (ban)

- Catalan: paraula (ca) f

- Czech: slovo boží n

- Finnish: sana (fi)

- French: parole (fr) f

- German: Wort (de) n

- Greek: λόγος (el) m (lógos)

- Indonesian: firman (id)

- Interlingua: parola (ia), verbo (ia)

- Italian: parola (it) f, verbo (it) m

- Japanese: 福音 (ja) (ふくいん, fukuin)

- Korean: 복음(福音) (ko) (bogeum), 말씀 (ko) (malsseum)

- Lingala: liloba

- Luxembourgish: Wuert (lb) n

- Macedonian: божја реч f (božja reč)

- Malay: sabda, firman

- Maore Comorian: Urongozi wa Mungu class 11

- Norwegian: ord (no) n

- Persian: گفتار (fa) (goftâr)

- Polish: Słowo Boże n

- Portuguese: verbo (pt), palavra (pt) f, palavra do Senhor f, palavra divina f, palavra de Deus f

- Romanian: cuvânt (ro) n

- Russian: сло́во бо́жье n (slóvo bóžʹje)

- Slovak: slovo božie n, božie slovo n

- Telugu: వాణి (te) (vāṇi)

Verb[edit]

word (third-person singular simple present words, present participle wording, simple past and past participle worded)

- (transitive) To say or write (something) using particular words; to phrase (something).

- Synonyms: express, phrase, put into words, state

-

I’m not sure how to word this letter to the council.

- (transitive, obsolete) To flatter with words, to cajole.

-

1607, William Shakespeare, Anthony and Cleopatra, act 5, scene 2:

-

He words me, girls, he words me, that I should not / be noble to myself.

-

-

- (transitive) To ply or overpower with words.

-

1621 November 30, James Howell, letter to Francis Bacon, from Turin:

-

[…] if one were to be worded to death, Italian is the fittest Language [for that task]

-

-

1829 April 1, “Webster’s Dictionary”, in The North American Review, volume 28, page 438:

-

[…] if a man were to be worded to death, or stoned to death by words, the High-Dutch were the fittest [language for that task].

-

-

- (transitive, rare) To conjure with a word.

- c. 1645–1715, Robert South, Sermon on Psalm XXXIX. 9:

- Against him […] who could word heaven and earth out of nothing, and can when he pleases word them into nothing again.

-

1994, “Liminal Postmodernisms”, in Postmodern Studies, volume 8, page 162:

-

«Postcolonialism» might well be another linguistic construct, desperately begging for a referent that will never show up, simply because it never existed on its own and was literally worded into existence by the very term that pretends to be born from it.

-

-

2013, Carla Mae Streeter, Foundations of Spirituality: The Human and the Holy, →ISBN, page 92:

-

The being of each person is worded into existence in the Word, […]

-

- c. 1645–1715, Robert South, Sermon on Psalm XXXIX. 9:

- (intransitive, archaic) To speak, to use words; to converse, to discourse.

-

1818–1819, John Keats, “Hyperion, a Fragment”, in Lamia, Isabella, the Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems, London: […] [Thomas Davison] for Taylor and Hessey, […], published 1820, →OCLC, page 181:

-

Thus wording timidly among the fierce: / «O Father, I am here the simplest voice, […] «

-

-

Derived terms[edit]

- misword

- reword

- word it

- wordable

- worder

Translations[edit]

to say or write using particular words

- Bulgarian: изразява (bg) (izrazjava)

- Catalan: redactar (ca)

- Chinese:

- Mandarin: 措辞 (zh)

- Danish: formulere

- Dutch: verwoorden (nl), onder woorden brengen, formuleren (nl)

- Finnish: muotoilla (fi) (to formulate); pukea sanoiksi (fi) (to put into words)

- French: formuler (fr)

- Greek: διατυπώνω (el) (diatypóno), συντάσσω (el) (syntásso)

- Hebrew: ניסח (nisákh)

- Hungarian: megfogalmazn

- Icelandic: orða

- Macedonian: изразува (izrazuva), формулира (formulira)

- Portuguese: frasear (pt)

- Russian: формули́ровать (ru) (formulírovatʹ)

- Spanish: redactar (es)

- Swedish: formulera (sv)

to ply or overpower with words

- Finnish: puhua (fi)

Interjection[edit]

word

- (slang, African-American Vernacular) Truth, indeed, that is the truth! The shortened form of the statement «My word is my bond.»

-

«Yo, that movie was epic!» / «Word?» («You speak the truth?») / «Word.» («I speak the truth.»)

-

- (slang, emphatic, stereotypically, African-American Vernacular) An abbreviated form of word up; a statement of the acknowledgment of fact with a hint of nonchalant approval.

-

2004, Shannon Holmes, Never Go Home Again: A Novel, page 218:

-

« […] Know what I’m sayin’?» / «Word!» the other man strongly agreed. «Let’s do this — «

-

-

2007, Gabe Rotter, Duck Duck Wally: A Novel, page 105:

-

« […] Not bad at all, man. Worth da wait, dawg. Word.» / «You liked it?» I asked dumbly, stoned still, and feeling victorious. / «Yeah, man,» said Oral B. «Word up. […] «

-

-

2007, Relentless Aaron, The Last Kingpin, page 34:

-

« […] I mean, I don’t blame you… Word! […] «

-

-

Quotations[edit]

- For quotations using this term, see Citations:word.

See also[edit]

- allomorph

- compound word

- grapheme

- idiomatic

- lexeme

- listeme

- morpheme

- orthographic

- phrase

- set phrase

- syllable

- term

Etymology 2[edit]

Variant of worth (“to become, turn into, grow, get”), from Middle English worthen, from Old English weorþan (“to turn into, become, grow”), from Proto-West Germanic *werþan, from Proto-Germanic *werþaną (“to turn, turn into, become”). More at worth § Verb.

Verb[edit]

word

- Alternative form of worth (“to become”).

See also[edit]

- Appendix:Wordhood

Further reading[edit]

word on Wikipedia.Wikipedia

Anagrams[edit]

- drow

Afrikaans[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Dutch worden, from Middle Dutch werden, from Old Dutch werthan, from Proto-Germanic *werþaną.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /vɔrt/

Verb[edit]

word (present word, present participle wordende, past participle geword)

- to become; to get (to change one’s state)

-

Ek het ryk geword.

- I became rich.

-

Ek word ryk.

- I am becoming rich.

-

Sy word beter.

- She is getting better.

-

- Forms the present passive voice when followed by a past participle

-

Die kat word gevoer.

- The cat is being fed.

-

Usage notes[edit]

- The verb has an archaic preterite werd: Die kat werd gevoer. (“The cat was fed.”) In contemporary Afrikaans the perfect is used instead: Die kat is gevoer.

Chinese Pidgin English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- 𭉉 (Chinese characters)

Etymology[edit]

From English word.

Noun[edit]

word

- word

-

1862, T‘ong Ting-Kü, Ying Ü Tsap T’sün, or The Chinese and English Instructor, volume 6, Canton:

-

挨仙㕭𭉉

- Aai1 sin1 jiu1 wut3.

- I will send you word.

- (literally, “I send you word.”)

-

-

Dutch[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ʋɔrt/

- Rhymes: -ɔrt

Verb[edit]

word

- first-person singular present indicative of worden

- imperative of worden

Middle English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- wurd, weord, vord, woord, wourd, worde

Etymology[edit]

From Old English word, from Proto-West Germanic *word, from Proto-Germanic *wurdą, from Proto-Indo-European *werdʰh₁om. Doublet of verbe.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /wurd/, /woːrd/

Noun[edit]

word (plural wordes or (Early ME) word)

- A word (separable, discrete linguistic unit)

-

a. 1400, Geoffrey Chaucer, “Book II”, in Troilus and Criseyde, line 22-28:

-

Ȝe knowe ek that in fourme of ſpeche is chaunge / With-inne a thousand ȝeer, and wordes tho / That hadden pris now wonder nyce and ſtraunge / Us thenketh hem, and ȝet thei ſpake hem so / And ſpedde as wel in loue as men now do

- You also know that the form of language is in flux; / within a thousand years, words / that had currency; really weird and bizarre / they seem to us now, but they still spoke them / and accomplished as much in love as men do now.

-

-

- A statement; a linguistic unit said or written by someone:

- A speech; a formal statement.

- A byword or maxim; a short expression of truth.

- A promise; an oath or guarantee.

- A motto; a expression associated with a person or people.

- A piece of news (often warning or recommending)

- An order or directive; something necessary.

- A religious precept, stricture, or belief.

- Discourse; the exchange of statements.

- The act of speaking (especially as opposed to action)

- The basic, non-figurative reading of something.

- The way one speaks (especially with modifying adjective)

- (theology) The Logos (Jesus Christ)

-

c. 1395, John Wycliffe, John Purvey [et al.], transl., Bible (Wycliffite Bible (later version), MS Lich 10.)[1], published c. 1410, Joon 1:1, page 44r, column 2; republished as Wycliffe’s translation of the New Testament, Lichfield: Bill Endres, 2010:

-

IN þe bigynnyng was þe woꝛd .· ⁊ þe woꝛd was at god / ⁊ god was þe woꝛd

- In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and God was the Word.

-

-

- (rare) The human faculty of language as a whole.

[edit]

- bodeword

- byword

- hereword

- mysword

- wacche word

- worden

- wordy

- wytword

Descendants[edit]

- English: word

- Scots: wird, wourd

References[edit]

- “wō̆rd, n.”, in MED Online, Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan, 2007, retrieved 27 February 2020.

Old English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- ƿord

- wyrde

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /word/, [worˠd]

Etymology 1[edit]

From Proto-West Germanic *word, from Proto-Germanic *wurdą.

Noun[edit]

word n (nominative plural word)

- word

- speech, utterance, statement

- (grammar) verb

- news, information, rumour

- command, request

Declension[edit]

Declension of word (strong a-stem)

Derived terms[edit]

- bīword

- ġylpword

- witword

- wordbōc

- wordfæst

- wordiġ

Descendants[edit]

- Middle English: word, wurd, weord

- Scots: word, wourd

- English: word

Etymology 2[edit]

Unknown. Perhaps ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dʰos (“sweetbriar”). Compare Latin rubus (“bramble”), Persian گل (gol, “flower”).

Noun[edit]

word ?

- thornbush

Old Saxon[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Proto-West Germanic *word, from Proto-Germanic *wurdą.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /wɔrd/

Noun[edit]

word n

- word

Declension[edit]

Declension of word (neuter a-stem)

Скачать материал

Скачать материал

- Сейчас обучается 396 человек из 63 регионов

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

1 слайд

Word as the basic unit of language

Lecture 2. -

2 слайд

§ 1. The Definition of the Word

A successful definition should 1) contain essential features of a word and 2) draw a sharp borderline between various linguistic units:

1.1. word and phoneme (Oh! I)

1.2. word and morpheme (man, wise, ism)

1.3. word and phrase (all right, alarm clock, the reciprocal pronouns each other and one another) -

3 слайд

1.1. Unity of form and meaning

Word — Formphonetic/graphic morphological structure grammar form

Essential features

Word – Meaningdenotational connotational lexico-grammatic grammatic

-

4 слайд

1.2. When used in sentences words are syntactically organized. Their freedom of entering into syntactic constructions is limited by rules and constraints

They told me this story vs. They spoke me this story

to deny smth categorically vs. to admit categorically1.3. Words are characterized by (in)ability to occur in different situations

In a business letter: ‘I was a bit put out to hear that you are not going to place the order with us’

To a friend: ‘I regret to inform you that our meeting will have to be postponed. -

5 слайд

Distinctive features: Within the scope of linguistics the word has been defined syntactically, semantically, phonologically and by combining various approaches.

Syntactic: H. Sweet «the minimum sentence“

L. Bloomfield «a minimum free form».

Syntactic and semantic aspects:

E. Sapir — «one of the smallest completely satisfying bits of isolated ‘meaning’, into which the sentence resolves itself. It cannot be cut into without a disturbance of meaning”.

Indivisibility criterion: A lion is a word-group because we can insert other words between them: a living lion. Alive is a word: it is indivisible, nothing can be inserted between its elements.

Semantic:

Stephen Ullmann: “words are meaningful units.» -

6 слайд

Semantic-phonological approach:

A.H.Gardiner: «A word is an articulate sound-symbol in its aspect of denoting something which is spoken about.»

Thus, a satisfying word-definition should reflect the following features as borrowed from the above explanations:

the association of a particular meaning with a particular group of sounds

capable of a particular grammatical employment

the smallest significant unit, used in isolation

capable of functioning alone

characterized by morphological uninterruptability and

having semantic integrity -

7 слайд

§ 2. Types of lexical units

The units/elements of a vocabulary are lexical units, which means that they are two-facet elements possessing form and meaning.

Set expressions or groups of words into which words may be combined

Morphemes which are parts of words, into which words may be analyzed

They are, apart from words: -

8 слайд

Morphemes are structural units which either form a new word or modify its meaning. Their meaning is of more abstract and general nature. Morphemes can’t function alone and deny grammar change.

Set expressions are word groups consisting of two or more words whose combination is integrated so that they are introduced in speech ready-made as units with a specialized meaning of the whole that is not understood as a mere sum total of the meanings of the elements.

-

9 слайд

are the biggest units of morphology and the smallest of syntax

embody the main structural properties and functions of the language (nominative, significative, communicative and pragmatic)

can be used in isolation

are thought of as having a single referent or represent a concept, a feeling, an action

are the smallest units of written discourse: they are marked off by solid spelling

segmentation of a sentence into words is easily done by an illiterate speaker, but that of a word into morphemes presents sometimes difficulties even for trained linguists

are written as a sequence of letters bounded by spaces on a page (with exceptions)

Wоrds are the central elements of language system = we speak in words and not otherwise, because they : -

10 слайд

Thus, the vocabulary of a language is not homogeneous, it’s made of sets with blurred boundaries

WORDS

morphemes

set expressions

phrasal verbs

adaptive abstract system

selective reflection

Syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations

Functional vs. referential approach -

11 слайд

§ 3. Types of words

Eight Kinds of Words by Tom McArthur:The orthographic word

(a visual sign with space around: colour vs. color)

The phonological word

(a spoken signal: a notion vs. an ocean)

The morphological word

(a unity behind variants of form

The lexical word

(lexeme, full word as related to a thing, action or state in the world) -

12 слайд

The grammatical word

(form word, a closed set of conj-s, determiners, particles, pronouns, etc.)

The onomastic word

(words with unique reference: Napoleon)

The lexicographical word

(a word as an entry in the dictionary)

The statistical word

(each letter or group of letters from space to space) -

13 слайд

Types of words as regards their structure, semantics and function (E.M. Mednicova):

MORPHOLOGICALLY:

Monomorphemic: root-words

Polymorphemic: derivatives, compounds, compound-

derivatives, derivational compoundsSEMANTICALLY:

Monosemantic: words having only one lexical meaning and denoting, accordingly, one conceptPolysemantic: words having several meanings, thus denoting a whole set of related concepts grouped according to the national peculiarities of a given language

-

14 слайд

SYNTACTICALLY:

Categorematic: notional words

Syncategorematic: form-wordsSTYLISTICALLY:

Neutral

Elevated (bookish) (steed, to commence, spouse, slay, maiden)

Colloquial (smart, cute, chap, trash, horny)

Substandard words (vulgarisms, taboo, jargon argot, slang), etc (there are various other stylistic groupings).ETYMOLOGICALLY:

Native

Borrowed

Hybrid

international words -

15 слайд

Practical tasks # 2

Which criterion can be used to distinguish word from other language units? Match:

a) Phoneme1) meaningful unit able of functioning alone

b) Morpheme2) unity of form and meaning

c) Free phrase 3) semantic integrity

2. Which units from the list below are not lexical units?

Shchd) he is a genius

To make firee) in a nutshell

Did f) dogs -

16 слайд

3. How many lexemes are there in the phrase:

Don’t trouble trouble until trouble troubles you.

4. Which one of these words is monosemantic?

to get, a cat, an aspen-tree, to borrow, a ball, to follow.

Найдите материал к любому уроку, указав свой предмет (категорию), класс, учебник и тему:

6 210 144 материала в базе

- Выберите категорию:

- Выберите учебник и тему

- Выберите класс:

-

Тип материала:

-

Все материалы

-

Статьи

-

Научные работы

-

Видеоуроки

-

Презентации

-

Конспекты

-

Тесты

-

Рабочие программы

-

Другие методич. материалы

-

Найти материалы

Другие материалы

- 31.12.2020

- 5414

- 40

- 31.12.2020

- 4723

- 0

- 31.12.2020

- 6177

- 11

- 30.12.2020

- 4547

- 0

- 30.12.2020

- 4464

- 1

- 30.12.2020

- 4748

- 2

- 30.12.2020

- 5164

- 3

- 30.12.2020

- 4430

- 3

Вам будут интересны эти курсы:

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Основы построения коммуникаций в организации»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация практики студентов в соответствии с требованиями ФГОС технических направлений подготовки»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Маркетинг в организации как средство привлечения новых клиентов»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Разработка бизнес-плана и анализ инвестиционных проектов»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Использование активных методов обучения в вузе в условиях реализации ФГОС»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация деятельности секретаря руководителя со знанием английского языка»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Управление сервисами информационных технологий»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Актуальные вопросы банковской деятельности»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Риск-менеджмент организации: организация эффективной работы системы управления рисками»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Техническая диагностика и контроль технического состояния автотранспортных средств»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Международные валютно-кредитные отношения»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Информационная поддержка бизнес-процессов в организации»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Управление качеством»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Стандартизация и метрология»

Word

occupies central place in the hierarchy of lingual units which

comprises the following levels: phonemes, morphemes, lexemes (words),

phrasemes (word-combinations), sentences and text. Word is a basic

lingual unit consisting of morphemes, each of which consists of

phonemes. Words differ from morphemes due to the quality of their

meaning. Word is a nominative

lingual unit, which expresses direct, nominative meaning: it names,

or nominates various referents. The words consist of morphemes, and

the shortest word can include only one morpheme, e.g. cat.

The meaning of the morpheme is abstract and significative: it does

not name the referent, but only signifies it. Separate words should

be distinguished from word-combinations, which are the combinations

of two or more notional words, representing complex nominations of

various referents (things, actions, qualities, and even situations)

in a sentence, e.g. a

sudden departure.

The meaning of a word-combination is complex nomination.

In

connection with the hierarchy of lingual units there exists the

size-of-unit problem.

It’s the problem of discriminating between the word and the

morpheme, on the one hand, and the word-combination, on the

other hand, and the issue of how words can be singled out in the flow

of speech as independent units.

Words

differ from morphemes which cannot function beyond words. The word

criterion is the positional

mobility

while morphemes are bound within a sequence: shipwreck(s)

VS

the wreck(s)

of the

ship(s);

John

Lyons illustrates the fact with the following sequences: the

boys walked slowly up

the

hill;

slowly

the boys walked up the hill;

up the hill slowly walked the boys.

Words

differ from word-combinations. One cannot insert another word between

the elements of the given word without a disturbance of its meaning,

unlike word combinations words are characterized by indivisibility

or morphological

uninterruptability:

a

lion (a

living lion,

a dead lion)

VS

alive.

Graphically

words also tend to be indivisible though some borderline units occur

where parts of compound words are graphically separable: each

other,

one

another,

but morphologically indivisible:

with each other,

with

one another.

Variation takes place in altogether

which

is one word according to its spelling, whereas all

right

which is rather a similar combination has a different spelling.

Phonologically

the majority of English words tend to bear one stress: ‘mother,

‘brand

name.

Grammatically

words also tend to be whole-formed.

A word has grammatical forms which are expressed by grammatical

suffixes added to the word:

mother – mothers,

at my mother’s,

two

gin and tonics.

But

how should one treat the following sequences: Ilf

and Petrov’s book;

the girl I danced with’s father;

‘we were the

good guys,

they were the bad guys’

kind of thing?

In

such cases one can apply to the criterion of semantic

integrity,

that is naming one thing, not many things:

Earl Grey,

real estate, rack rate.

The semantic criterion can be also applied to functional words which

function like morphemes: to

give up.

As

the above mentioned examples show, there is a size-of-unit problem.

That’s why Check linguists Josef Bachek and Vilem Mathesius stated

that there is no borderline between a word and a word-combination,

which correlates with the field theory.

Thus, words are relatively

easy to be diagnosed in speech as separate units because they are

featured by positional mobility, semantic integrity and graphic,

phonological and grammatical whole-formedness.

The

identity-of-unit problem.

The term ‘identity’ implies systemic speech usage and

invariability of basic properties of the lingual unit.

Words are subject to some

variations. Sometimes the ‘law of the sign’ (one-to-one

correspondence of expression and content) is violated without

impairing the word’s globality as a separate lexical unit.

1.

Phonetic variation: bread

and butter,

now and then,

normal and natural,

Past Simple;

‘contrary

– cont‘rary,

‘territory

– terri‘tory,

‘aristocrat

– a‘ristocrat,

‘coffee

bean – ‘coffee

bean,

again,

Iranian,

privacy,

mountain,

expertise,

nausea.

2. Morphological variation:

a)

grammatical: to

learn – learned,

learnt;

to broadcast – broadcasted,

broadcast; to bide – bode,

bidded – bided,

bidden;

bolsheviki – bolsheviks;

b)

word-building: academic

– academical,

explicable

– explainable,

damp

down

– dampen

down.

The

words of this group make the so-called doublets.

They

vary in pronunciation and morphemic arrangement, but function as full

equivalents of each other. They do not signal some semantic or

stylistic change of context. Their usage depends only on speech habit

of a speaker.

3.

Lexico-semantic variants (polysemy): bed (1. furniture,

2.

bottom,

3.

area or ground).

Variants

of the words

are their subkinds conditioned by position (context). Variants of the

word cannot replace each other, they can only complement each other

in different surroundings. Sometimes different lexico-semantic

variants have peculiarities in word-changing paradigm, e.g. the verb

to

cost

can function as a regular one in the meaning ‘to estimate the price

of’: We’ll

get the plan costed before presenting it to the board

or Well,

I’ve only had 3 courses and a bottle of wine and costed here.

One

should be able to discriminate between different meanings of the same

word and its homonyms: a

baseball club,

a golf club,

a club of a gun – a wine club.

Polysemy

doesn’t violate the identity of the word as all the meanings of it

are interconnected with each other, they have some common semantic

element (a baseball club, a golf club, a club of a gun are kinds of a

stick). The meanings of homonyms are by no means connected with each

other (a

club of a gun и

a

wine club).

Word

as a lingual sign.

Ferdinand de Saussure was the first to define lingual units as

specific signs:

the elements of language are special lingual signs – meaningful,

bilateral (two-sided) units that have both form

and meaning.

Ferdinand de Saussure spoke about an indissoluble link between a

phonetic ‘signifier’

(French ‘signifiant’), and concept signified

(‘signifie’).

The other pair of terms to name these two sides of a lingual sign was

suggested by Luis Elsmlev: the

plane of content

and the

plane of expression.

There

is regular semantic connection between the signifier and the

signified, otherwise people wouldn’t be able to understand each

other in the process of human intercourse.

Arbitrariness

is the fundamental property of the lingual sign. It is the absence of

any natural connection between the signifier and the signified. For

example, the form and the meaning of the word eye

are arbitrarily linked, the connection between them being a matter of

convention (this means that there is no reason beyond convention why

the English word eye

should refer to глаз

and not to ухо,

нос

or something else). Moreover either changed over time. On the one

hand, the graphic form were altered (cf. Old English eage,

ege;

Middle English eie,

ie).

On the other hand, in the course of time the meaning of the word

developed along several lines, e.g.: “the power of seeing”, “the

hole in the needle through which the thread passes”, “the calm

centre of a storm, especially of a hurricane”, etc. In other words,

there is no necessary connection between the word and the object it

denotes, and either may change over time.

The

idea of arbitrariness can also be supported by the fact that in

various languages one and the same object is given different names,

cf. English wife,

Russian жена,

German Frau,

French femme.

Asymmetric

duality

of the lingual sign is the ability of the plane of expression

(signifier) to be associated with more than one signified (plane of

content) – polysemy, homonymy: table,

bank of a river – central bank,

seal,

hand;

and the ability of the plane of content (the signified) to be

associated with more than one plane of expression (the signifier) –

synonymy: nice

– pleasing,

agreeable;

pretty – nice,

beautiful.

Sometimes

a lingual sign (including words) is graphically presented in the form

of a triangle (Diagram 2), including material form, content and

referent. Fulfilling the naming (expressive) function, a word

represents a unity of the three components: the material (sound)

form, the referent and the concept of it. For example, the word ‘dog’

is a sign, consisting of a signifier, or form – the sequence of

phonemes (or, in written presentation, of letters), and a signified,

or concept – the image of the animal in our mind; the referent is

the ‘real’ animal in the outside world, which may or may not be

physically present.

Diagram 2.

concept

(an idea of a class of objects)

‘dog’

sound

form (sign) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ referent

(thing

meant)

The

sign problem applied

to a word

is

all about identifying the correlation between the word and the

referent and the connection between the sound form and the concept it

signifies.

Motivation

of the word.

Some

lingual signs may be motivated. Motivation

(inner word form, etymological structure) of the lingual sign is the

direct connection between the signifier and the signified. Some

examples, of motivation are cuckoo,

bluebell,

woodpecker,

volleyball

(volley

– «стрелять

залпами»),

alphabet.

The question of word motivation is examined by onomasiology.

Motivation

doesn’t imply an exact reflection of the world in a language. The

basis for motivation is usually some outstanding, conspicuous but not

necessarily significant feature(s) (e.g. Russian медведь

– «медом

ведает»;

English handkerchief

– hand

«рука»

+ kerchief

«платок»).

Thus, in case of motivation many language phenomena appear as a

result of some interpretation of reality by speakers. If the word

preserves semantic connection with the words it has been derived

from, it is considered to be motivated or have a transparent inner

word form:

time-table,

foresee,

speaker,

to safeguard,

chairman, springboard.

If the speaker isn’t aware of the semantic connection

between the meaning of the word and its form,

the word is said to

be

non-motivated

for

the present stage of language development:

home,

read,

parachute,

etc.

Borrowings are seldom motivated for native speakers.

It

should be borne in mind that in different languages one and the same

object gets its name on the basis of different features. That’s why

motivation of the words expressing the same notion in different

languages may differ: cf. Russian стол

< стлать,

English table

< Latin tabula

(доска).

Traditionally, three types of

motivation are distinguished: phonetic, morphological, and semantic.

Phonetic

motivation

is a direct connection between the sound form of the word and its

meaning. Phonetic motivation is observed in onomatopoeic words, e.g.

buzz,

splash,

gargle,

purr,

etc. Onomatopoeia

or

sound imitation is the naming of the action or thing by a more or

less exact reproduction of a sound associated with it.

Morphologic(al)

motivation

is a direct connection between the morphological structure of the

word and its meaning. For example, in the pair friend

– unfriendly,

the morphologically motivated word is unfriendly.

The morphological structure suggests the following: the prefix un-

gives a negative meaning to the stem; the suffix -ly

shows the part of speech – when the suffix -ly

is attached to a noun stem, the resultant word is an adjective.

Semantic

motivation

is a connection between the direct meaning and figurative meaning(s)

of the word. The derived meaning is interpreted by means of referring

to the primary one, the transfer being often based on metaphor or

metonymy. For instance, the direct meaning of mink

“a small fierce animal like a weasel” is not motivated, but

its figurative metonymical meaning “the valuable brown fur of this

animal (a mink

coat)” is motivated by the direct meaning and based upon it.

Thus, the word is a basic

lingual unit possessing a form to express concepts which reflect

reality within the word meaning. Words reflect reality in this

respect. The sound form of a word doesn’t reflect outward reality,

it only gives a name to some phenomenon. In this sense word is a

sign. Word is an arbitrary sign regularly used in communication,

though some words can be motivated. Words combine in sentences, in

connected sense-bearing speech, this property distinguishes them from

morphemes which can’t function in speech beyond words. Words are

relatively easy to be distinguished in speech as they are separate

meaningful (characterized by semantic integrity) whole-formed

(phonologically, morphologically and grammatically) lingual units.

Words are used in speech in one meaning.

Word is the most complex unit

of language. It comprises synchronic and diachronic features. Word

refers to the real world of things, thinking and other lingual units.

It coarticulates the signifier and the signified while the signifier

can correspond to several signified (homonymy, polysemy) and vice

versa (synonymy). Word is a merger of sound, morphological and

semantic structures. It belongs to both grammatical and lexical

systems, and at the same time takes part in human communication. Word

semantically interacts with meanings of other words. It always enters

some lexical set, class, sub-class, group or row.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

01.05.201512.56 Mб51ENLISH GRAMMAR (Understanding & Using).pdf

- #

- #

- #

This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

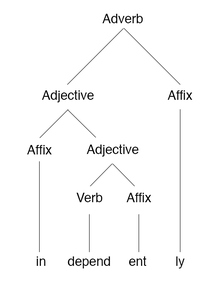

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.