2.1. Word structure

The

bulk of the OE vocabulary consisted of native words. In the course

of the OE period the vocabulary grew; it was mainly replenished from

native sources, by means of word-formation. According

to their morphological structure OE words (like modern words)

fell into three main types:

-

simple

words («root-words») or words with a simple stem,

containing

a root-morpheme and no derivational affixes, e.g. land

‘land’,

sinan

‘sing’, ōd

‘good’; -

derived

words consisting of one root-morpheme and one or more affixes,

e.g. be-innan

‘begin’,

weorþ-un

’worthiness’,

un-scyld-i

‘innocent’,

e-met-in

‘meeting’. -

compound

words, whose stems were made up of more than one root-morpheme,

e.g. mann-cynn

‘mankind’,

norþe-weard

‘northward’,

fēower-tiene

‘fourteen’,

wall-eat

‘wall gate’,

scir-e-refa

‘sheriff’.

2.2. Ways of word-formation

In

OE

there existed a well-developed system of word-formation.

A

single root could

appear in many simple, derived and compound words. For

instance, OE mōd

‘mood’ yielded about fifty words: derived words,

such as mōdi,

emōded,

ofermōd (‘proud’,

‘disposed’, ‘arrogance’), compound

words mōd-caru,

mōd-lēof, mōd-eþōht,

lædmōdnis

(‘care’,

‘beloved’,

‘thought’, ‘kindness’). Scores of words contained the roots of

OE dæ

‘day’,

ōd

‘good’,

monn

‘man’,

weorþ

‘worth’,

lon

‘long’.

Many

derivational affixes appear to have been very productive as they

occurred

in numerous words: a prefix wiþ-

in

more than fifty words, ofer-

in

over a hundred words.

OE

employed two ways of word-formation: derivation and word-composition.

-

Word-derivation

Derived

words in OE were built with the help of affixes: prefixes

and suffixes; in addition to these principal means of derivation,

words

were distinguished with the help of sound interchanges and word

stress.

2.2.1.1. Suffixation

Suffixation

was by far the most productive means of word derivation

in OE. Suffixes not only modified the lexical meaning of the

word but could refer it to another part of speech. Suffixes were

mostly applied

in forming nouns and adjectives, seldom – in forming verbs.

Suffixes

are usually classified according to the part of speech which

they can form. In OE there were two large groups of suffixes:

suffixes of nouns and suffixes of adjectives.

Substantive Suffixes

Here

we find a group of suffixes which are added to substantive

or verb stems to derive names of the doer. Each of them is connected

with a grammatical gender.

Thus,

the suffix -ere

is used to derive masculine substantives: fiscere

‘fisherman’,

fuelere

‘fowler’,

wrītere

‘writer’,

‘scribe’, also þrōwere

‘sufferer’.

The suffix corresponds to the Gothic suffix –areis

in

laisareis

‘teacher’,

bōkareis

‘bookman’,

and Russian -apь

in naxapь,

вpaтapь. The

suffix is productive.

The

suffix -estre

is used to derive feminine substantives: spinnestre

‘spinner’

bæcestre

‘woman

baker’, also witeestre

‘prophetess’.

The

suffix -end

(connected with the participle suffix -ende)

is used

to derive masculine substantives: frēond

‘friend’,

fēond

‘hater’,

‘enemy’,

hælend

‘saviour’,

dēmend

‘judge’,

wealdend

‘ruler’.

The

suffix -in

is used to derive patronymics: æðelin

‘son

of a

nobleman’, ‘prince’, cynin

‘king’,

Æðelwulfin

‘son

of Æthelwulf’, etc.

It is also used to derive substantives from adjectives, as in ltlin

‘baby’,

earmin

‘poor

fellow’. The suffix is productive. An enlarged

variant of this suffix, -ling,

serves to derive substantives with some emotional colouring

(depending on the meaning of the stem):

ōslin

‘gosling’,

dēorlin

‘darling’,

hrlin

‘hireling’.

It is also

productive.

The

suffix -en

is used to derive feminine substantives from masculine

stems. As its original shape was -in,

it is always accompanied

by mutation: yden

‘goddess’

(< *udin),

cf.

ox

‘god’,

fyxen

‘vixen’

(< *fuxin), cf. fox

‘fox’.

The

suffix -nis,

-nes

is used to derive abstract substantives from

adjective stems: ōdnis

‘goodness’,

þrēnes

‘trinity’.

It is productive.

The

suffix -þ,

-uþ, -ōþ

is used to derive abstract substantives; sometimes

it is accompanied by mutation: trēowþ

‘truth’

from treow

‘true’,

piefþ

‘theft’

from pēof

‘thief’,

eouþ

‘youth’

(cf. eon

‘young’),

fiscoþ

‘fishing’,

cf. fisc

‘fish’,

huntoþ

‘hunting’,

cf. hunta’‘hunter’.

The

suffix -un,

-in

derives feminine verbal subsfantives: leornun,

leorning ‘learning’,

monun

‘admonishing’,

rædin

‘reading’.

It is productive.

Some

suffixes originated from substantives. Thus, from the substantive

dōm

‘doom’

came the suffix -dom,

as

in wīsdōm

‘wisdom’,

frēodōm

‘freedom’.

The

substantive hād

‘title’,

‘rank’ yielded the suffix -hād,

as

in cildhād

‘childhood,

mæhad

‘virginity’.

The

substantive lāc

‘gift’

yielded the suffix -lac,

as in rēoflāc

‘robbery’

from the stem of the verb rēafian

‘bereave’,

wedlāc

‘wedlock’,

scīnlāc

‘fantasy’.

The

substantive ræden

‘arrangement’, ‘agreement’ yielded the suffix

-ræden,

as in frēondræden

‘friendship’

sibbræden

‘relationship’,

mannræden

‘faithfulness’.

The

suffix -scipe

(cf. the verb scieppan

‘create’)

is found in the substantives

frēondscipe

‘friendship’,

weorþscipe

‘honour’,

ebēorscipe’feast’

(from bēor

‘beer’).

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

1. PARTS OF SPEECH AND GRAMMATICAL CATEGORIES

Old English was a synthetic, or inflected type of language; it showed the relations between words and expressed other grammatical meanings mainly with the help of simple (synthetic) grammatical forms. In building grammatical forms OE employed grammatical endings, sound interchanges in the root, grammatical prefixes, and suppletive formation.

Grammatical endings, or inflections, were certainly the principal form-building means used: they were found in all the parts of speech that could change their form; they were usually used alone but could also occur in combination with other means.

Sound interchanges were employed on a more limited scale and were often combined with other form-building means, especially endings. Vowel interchanges were more common than interchanges of consonants.

The use of prefixes in grammatical forms was rare and was confined to verbs. Suppletive forms were restricted to several ptonouns, a few adjectives and a couple of verbs.

The parts of speech to be distinguished in OE are as follows: the noun, the adjective, the pronoun, the numeral (all referred to as nominal parts of speech), the verb, the adverb, the preposition, the conjunction, and the interjection. Inflected parts of speech possessed certain grammatical categories displayed in formal and semantic correlations and oppositions of grammatical forms. Grammatical categories are usually subdivided into nominal categories, found in nominal parts of speech and verbal categories found chiefly in the finite verb.

We shall assume that there were five nominal grammatical categories in OE: number, case, gender, degrees of comparison, and the category of definiteness/indefiniteness. Each part of speech had its own peculiarities in the inventory of categories and the number of members within the category (categorial forms). The noun had only three grammatical categories: number, case and gender. The adjective had the maximum number of categories — five. The number of members in the same grammatical categories in different parts of speech did not necessarily coincide: thus the noun had four cases, Nominative, Genitive, Dative, and Accusative, whereas the adjective had five (the same four cases plus the Instrumental case). The personal pronouns of the 1st and 2nd person, unlike other psrts of speech, distinguished three numbers — singular, Plural and Dual.

sing. OE ic (NE I), dual wit ‘we two’, pl. we (NE we)

Verbal grammatical categories were not numerous: tense and mood — verbal categories proper — and number and person, showing agreement between the verb-predicate and the subject of the sentence.

The distiction of categorial forms by the noun and the verb was to a large extent determined by their division into morphological classes: declensions and conjugations.

2. SOME COMMON GERMANIC FEATURES

It is the opinion of many scholars that the grammatical structure of the Old Germanic languages was, but for a few exceptions, similar to that of other Old Indo-European languages. They shared similar systems of the parts of speech, similar categories of the noun, the verb, etc.

The structure of the word is supposed to have been the same in all the Indo-European languages. Between the root and the ending, there were usually stem-building suffixes. For instance, the Gothic word sunus (E. son) consisted of three parts, the root sun-, the stem-buiding suffix -u-, and the ending of the nominative singular -s. Thus the stem of the word, sunu-, ended in the sound [u], and it is customary to speak in such cases of an u-stem. There were likewise o-stems, a-stems, n-stems, etc. The paradigm of a word, that is the system of its endings, often depended on its stem-building suffix. The number of stems containing no stem-building suffixes, so that the endings were added directly to the root (root-stems), was comparatively small.

Later on this clear-cut structure of the word was blurred, especially in the Germanic languages. The endings were often fused with the preceding suffixes, or they were lost altogether. For instance, the Russian word сын or the English son have preserved neither the ending of the nominative singular, nor the stem-building suffix. In the OE sunu ‘son’ the last ‘u’ was no longer felt as the stem-building suffix, but rather as an ending. Still, liguists have found it convenient to speak of the u-stem declension, o-stem declension, etc. even after the loss of the corresponding sounds.

Besides the features the Germanic languages shared with other members of the Indo-European family, they had certain peculiarities that marked them off as a separate branch. We shall dwell here only on the following two major features:

1. A special ‘weak’ conjugation of verbs,

2. A special ‘weak’ declension of adjectives.

1. The Modern English verbs write and want differ in the way they form the past tense. The former changes its root vowel (write — wrote), which is called ablaut in German and gradation in English. The latter adds a suffix (want-wanted). The ablaut verbs were called strong by Jacob Grimm, the others weak. Strong verbs, though typical of the Germanic languages, can be found in other branches as well. Cf. R. несу[нису] — нес[нес], Gr. leipo ‘I leave’ — leloipa ‘I have left’. But weak verbs, forming the past tense by adding dental suffix (i.e. a suffix containing the sounds [d] or [t]), are found nowhere else.

Naturally, linguists are interested in the origin of the dental suffix, the most essential feature of these verbs. So far opinions differ. One point of view is that the dental suffix is an outgrowth of the verb to do which seems to have been used as an auxiliary verb of the past tense (something like work did for worked). In the course of time this enclictic did is supposed to have debeloped into the past tense suffix -ed. Later the suffix is said to have spread to the past participle as well.

Another hypothesis is that the dental suffix first developed in the past participle. It might well happen, seeing that there are dental consonants in the participle suffixes of many Indo-European languages. Cf. R. разбит(ый), одет(ый), L. dictus ‘said’, lectus ‘read’, etc. According to this theory the dental suffix of the past tense is a later development on the analogy of the past participle.

2) A special ‘weak’ declension of adjectives will be discussed later on.

3. THE NOUN.

Old English nouns possessed the categories of number, case and gender. There were two numbers (singular and plural), four cases (nominative, genitive, dative and accusative) and three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter).

3.1. The expression of relationships: inflexions or element order and prepositions?

George Bernard Shaw based his play Androcles and the Lion on the story of the runaway slave who had the good fortune to encounter as his opponent in the Roman arena the very lion from whose paw he had removed a thorn while he was at liberty. The lion recognized him and embraced him in-stead of tearing him to pieces. Readers of today’s newspapers will not find it difficult to imagine the headline LIONESS KISSES MAN over the story and to interpret it as meaning “The lioness kissed the man”. The sentence can be described in different ways:…..

If we now write MAN KISSES LIONESS (“The man kissed the lioness”), the order is still SVO but the meaning has changed because the man is now the subject and the lioness the object. This change demonstrates the vital role played in MnE by what is called word-order or element order.

The Anglo-Saxon predecessor of the hypothetical newspaper man who produced the headline LIONESS KISSES MAN could have written

LEO CYSSE GUMAN or

GUMAN CYSSE LEO or

GUMAN LEO CYSSE with the orders SVO, OVS and OSV respectively, because in Old English many nouns change their subject or nominative form to an accusative form when they are used as direct object.

Thus MAN KISSES LIONESS could have appeared as

GUMA CYSSE LEON

LEON CYSSE GUMA

LEON GUMA CYSSE

3.2. Types of declension

OE possessed several types of declension. They are usually denoted in grammar books by the last sound the stem-building suffix of the corresponding nouns is thought to have possessed in the common Indo-European language or its dialects. Hence such names as o-declension, a-declension, n-declension, etc. And although OE wulf (E. wolf) no longer contain any stem-building suffix, it is said to belong historically to the o-stem declension, as well as Latin lupus or Greek lukos.

It has become traditional to call the declensions of stems ending in a vowel — strong (o-, a-, i-, u-declensions), of n-stems — weak, and to designate all other declensions as minor (r-, nt-, s-, root-declensions).

We give here only the most common paradigms which have left certain traces in Modern English.

3.2.1. The o -stem declension.

It comprised very many OE nouns of the masculine and neuter genders and played the most important role in the history of English noun inflections.

Here is the paradigm of the OE nouns hund ‘dog’ (E. hound) and stan (E. stone), both masculine.

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nom. | hund | hundas | stan | stanas |

| Gen. | hundes | hunda | stanes | stana |

| Dat. | hunde | hundum | stane | stanum |

| Acc. | hund | hunas | stan | stanas |

The ending -es of the Gen.Sing. has eventually developed into Modern English ‘s of the possessive case, and the ending -as of the Nom. and Acc.Pl. into the plural ending -(e)s of Modern English. Thus the two productive endings of Modern English nouns go down to the paradigm of the Old English masculine o-stems.

The neuter o-stems differed onlu in Nom. and Acc. Pl. where the usual ending was -u instead of -as. That unstressed -u ending regularly disappeared and the form of the plural became identical with that of the singular.

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nom. | scip | scipu | word | word |

| Gen. | scipes | scipa | wordes | worda |

| Dat. | scipe | scipum | worde | wordum |

| Acc. | scip | scipu | word | word |

3.2.2. The n -stem declension.

The weak n -declension comprised many masculine and feminine nouns, but only two nouns of the neuter gender — OE eage (E. eye) and OE eare (E. ear).

Here is the paradigm of the OE oxa (E. ox) and nama (E. name), both masculine.

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nom. | oxa | oxan | nama | naman |

| Gen. | oxan | oxena | naman | namena |

| Dat. | oxan | oxum | naman | namum |

| Acc. | oxan | oxan | naman | naman |

The ending -an was originally the stem-building suffix. Compare ox- en -a with the Russian им- ен -а, им- ен; сем- ен -а, сем- ян.

The Modern English plural ending -en in oxen is derived from OE -an in oxan of Nom. and Acc. Plural. The ending -an (ME -en) was later extended to some nouns of other declensions, e.g. children, brethren.

3.2.3. Root-stems.

The peculiarity of the root-stems was that they contained no stem-building suffixes, the endings being simply added to the root. In OE there existed a few masculine and feminine nouns of that type.

Here is the paradigm of the OE noun fot (E. foot).

| Singular | Plural | |

| Nom. | fot | fet |

| Gen. | fotes | fota |

| Dat. | fet | fotum |

| Acc. | fot | fet |

It differs from the paradigm of the o-stems only in the Dat.Sing. and Nom. and Acc. Plural, where we find a different root vowel. The change [o>e] took place under the influence of the sound [i] (see ‘Palatal Mutation’) that had once been in the endings of those cases (Dat.Sing. fet < *foti and Nom., Acc. Pl. fet < Germ. *fotis). When the endings were later lost, the only difference between the singular and plural was the root vowel, and this difference has been retained in Modern English.

3.2.4. The s -stem declensions

This minor declension is of interest to us chiefly in connection with the form children.

In Russian there are a few s-stem nouns: небо — неб-ес-а, чудо — чуд-ес-а. IE [s] > Germ. [z] (Verner’s law). In West-Germanic [z] > [r] (rhotacism). Thus an IE s-stem became an r-stem in OE. Nouns of this declension were neuter and formed the plural in the following way:

lamb(root) + -r-(stem-building suffix) + -u(the ending of Nom. Plur.)

The noun child followed the same rule. Later it has acquired an additional plural ending -n by analogy with the n-stems. Hence children.

3.2.5. The r -stems.

In OE a few masculine and feminine nouns of relationship belonged to this type: fa der(E.father), bropor(E. brother), modor (E. mother), dohtor (E. daughter), sweostor (E. sister). These are probably the only Indo-European stems that have been preserved in Modern English.

As the endings of the o-stems were later extended to these nouns, there is no point in discussing their paradigms.

4. PRONOUNS

It is expedient to treat the OE personal proboubs of the first and second persons separatel because of their peculiarities.

1) They were the only words in OE whichdistinguished three numbers: singular, dual and plural.

2) Unlike the pronouns of the 3rd person they had no gender distictions.

3) Their paradigm contained more suppletive forms than other pronouns.

5. ADJECTIVES

In Modern English adjectives are indeclinable, but in Old English as well as in other Germanic languages almost every adjective could be declined in two different ways, and this is how it must have come about.

Originally the Indo-European adjective seems not to have differed from the noun in its paradigm. This is corroborated by facts like the Russian добр молодец, добра молодца, добру молодцу, or the Latin amicus bonus, amicis bonis, etc. But later the declension of adjectives was in most cases separated from that of nouns, acquiring some pronominal inflections. In Russian, for instance, the declension of full adjectives is now almost entirely pronominal.

Cf. того красного стола, тому красному столу, etc.

Likewise, the paradigms of Germanic adjectives contained many pronominal endings. This pronominal declension is usually called strong. But apart from it there developed a new declension called weak or nominal and connected with the n-stems.

In Modern Russian there have remained some 10 n-stem nouns: племя — плем-ен-и, знамя — знам-ен-и, etc. In other Indo-European languages, particularly in the Germanic languages, that class of nouns was much more numerous. Many of them were derived from adjectives and denoted persons or things possessing the qualities indicated by the corresponding adjectives. Thus, the Latin proper name Cato (g. Catonis) meaning ‘the sly one’, was derived from the adjective catus ‘sly’, the Greek name Platon ‘the flat one’ from the adjective platys ‘flat’, etc. Their declension was therefore identical with the declension of n-stem nouns. Later, by analogy, this declension spread to almost all adjectives, so that each could be declined either according to the weak or according to the strong declension. The choice depended on the presence or absence of a demonstrative or possessive pronoun or a similar defining word before the adjective. This usage has been well preserved in Modern German. Cf. diese guten Manner ‘these good men’, where after the demonstrative diese the adjective has the -n suffix of the weak declension, and gute Manner ‘good men’, where, without the demonstrative, the adjective is strong. Owing to its connection with defining words, the weak declension is also called definite as opposed to the indefinite strong declension.

The terms ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ are also applied to adjectives. Which form of the adjective is used depends not on the type of noun with which it is used, but on how it is used.

The strong form is used when the adjective stands alone, e.g. ‘The man is old’ se mann is eald, or just with a noun, e.g. ‘old man’ ealde menn.

The weak form appears when the adjective follows a demonstrative, e.g. ‘that old man’ se ealda mann, or a possessive adjective, e.g. ‘m old friend’ min ealda freond. You can remember that the strong forms stand alone, while the weak forms need the support of a demonstrative or possessive pronoun.

Weak declension (with demonstrative or possessive pronoun)

| Singular | Plural | |||

| Masc. | Neut. | Fem. | All genders | |

| Nom. | tila | tile | tile | tilan |

| Gen. | tilan | tilan | tilan | tilra, -ena |

| Dat. | tilan | tilan | tilan | tilum |

| Acc. | tilan | tile | tilan | tilum |

|

Обзор компонентов Multisim Компоненты – это основа любой схемы, это все элементы, из которых она состоит. Multisim оперирует с двумя категориями… |

Композиция из абстрактных геометрических фигур Данная композиция состоит из линий, штриховки, абстрактных геометрических форм… |

Важнейшие способы обработки и анализа рядов динамики Не во всех случаях эмпирические данные рядов динамики позволяют определить тенденцию изменения явления во времени… |

ТЕОРЕТИЧЕСКАЯ МЕХАНИКА Статика является частью теоретической механики, изучающей условия, при которых тело находится под действием заданной системы сил… |

|

Эндоскопическая диагностика язвенной болезни желудка, гастрита, опухоли Хронический гастрит — понятие клинико-анатомическое, характеризующееся определенными патоморфологическими изменениями слизистой оболочки желудка — неспецифическим воспалительным процессом… Признаки классификации безопасности Можно выделить следующие признаки классификации безопасности. Прием и регистрация больных Пути госпитализации больных в стационар могут быть различны. В центральное приемное отделение больные могут быть доставлены: |

ЛЕКАРСТВЕННЫЕ ФОРМЫ ДЛЯ ИНЪЕКЦИЙ К лекарственным формам для инъекций относятся водные, спиртовые и масляные растворы, суспензии, эмульсии, новогаленовые препараты, жидкие органопрепараты и жидкие экстракты, а также порошки и таблетки для имплантации… Тема 5. Организационная структура управления гостиницей 1. Виды организационно – управленческих структур. 2. Организационно – управленческая структура современного ТГК… Методы прогнозирования национальной экономики, их особенности, классификация В настоящее время по оценке специалистов насчитывается свыше 150 различных методов прогнозирования, но на практике, в качестве основных используется около 20 методов… |

Слайд 1KYIV NATIONAL LINGUISTIC UNIVERSITY

Subota S.V.

LECTURE 5

OLD ENGLISH SYNTAX AND VOCABULARY.

Слайд 2Plan

Word Order in OE.

Compound and Complex Sentences in OE. Means of

Connection.

Negation.

OE Vocabulary (Words of IE, CG Origin, loan-words).

Word formation in OE.

Слайд 3Literature

Расторгуева Т.А. История английского языка. – М.: Астрель, 2005. – С.

124-147.

Ильиш Б.А. История английского языка. – Л.: Просвещение, 1972. – С. 56-63, 114-132.

Иванова И.П., Чахоян Л.П. История английского языка. – М.: Высшая школа, 1976. – С.216-231, 239-256.

Студенець Г.І. Історія англійської мови в таблицях. — К.: КДЛУ, 1998. – Tables 55-60

Слайд 5

OE was a highly synthetic language.

It had a well-developed system of grammatical forms, which indicate the connection between words.

It was originally a spoken language; therefore the written forms of the language resembled oral speech – unless the texts were literal translations from Latin.

Consequently, the syntax of the sentence was relatively simple. Coordination of clauses prevailed over subordination and complicated syntactical structures were rare.

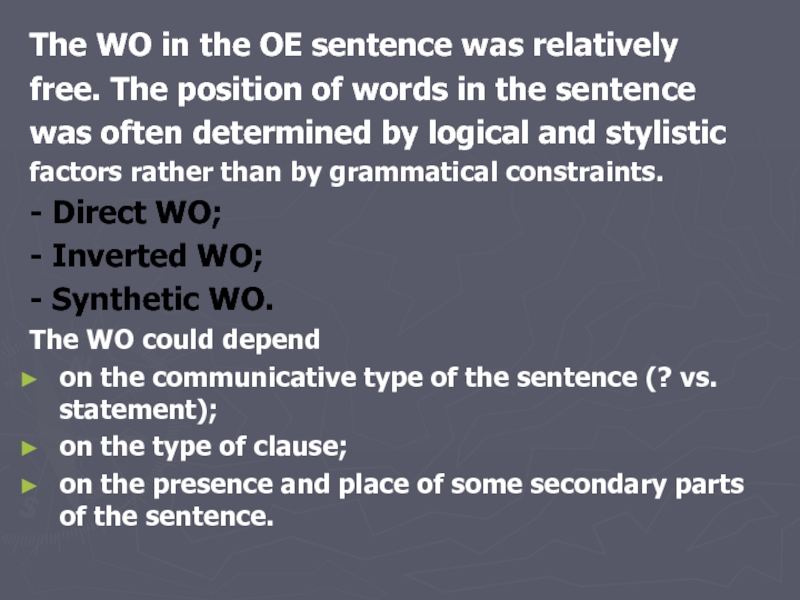

Слайд 6The WO in the OE sentence was relatively

free. The position of

words in the sentence

was often determined by logical and stylistic

factors rather than by grammatical constraints.

— Direct WO;

— Inverted WO;

— Synthetic WO.

The WO could depend

on the communicative type of the sentence (? vs. statement);

on the type of clause;

on the presence and place of some secondary parts of the sentence.

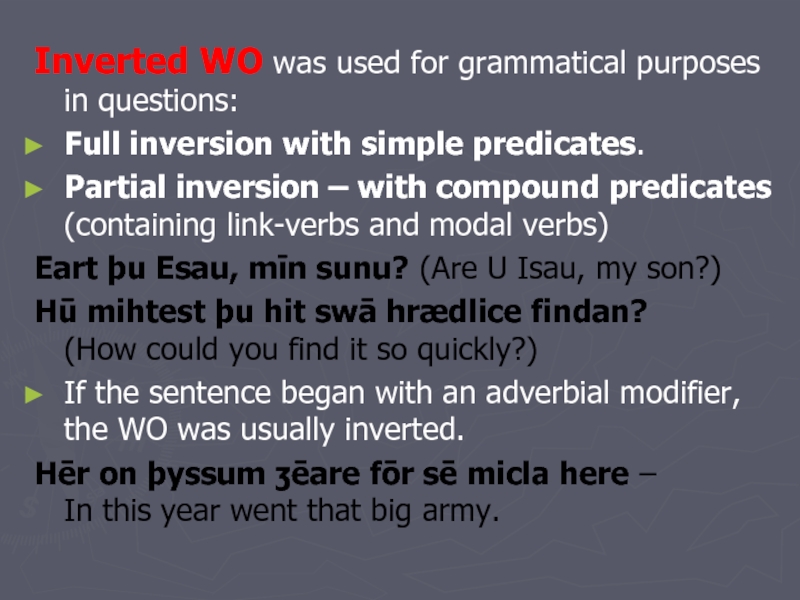

Слайд 7Inverted WO was used for grammatical purposes in questions:

Full inversion with

simple predicates.

Partial inversion – with compound predicates (containing link-verbs and modal verbs)

Eart þu Esau, mīn sunu? (Are U Isau, my son?)

Hū mihtest þu hit swā hrædlice findan? (How could you find it so quickly?)

If the sentence began with an adverbial modifier, the WO was usually inverted.

Hēr on þyssum ʒēare fōr sē micla here – In this year went that big army.

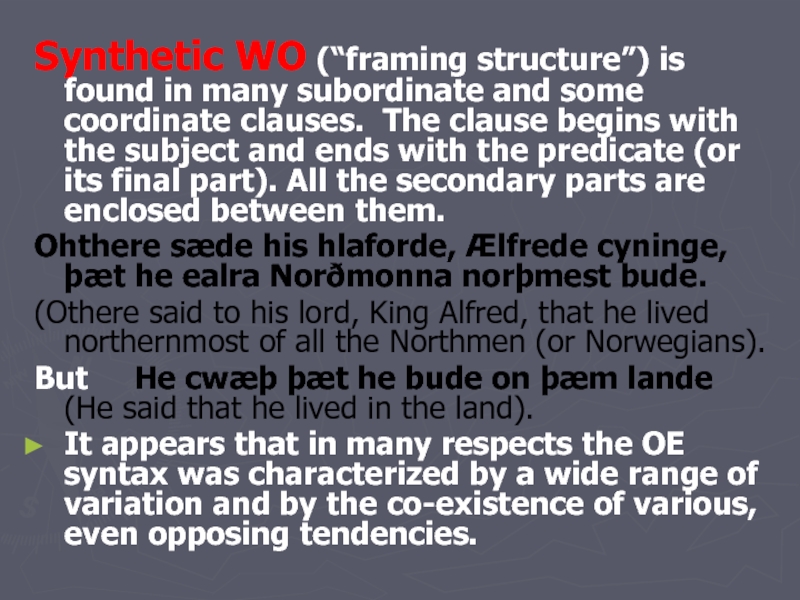

Слайд 8Synthetic WO (“framing structure”) is found in many subordinate and some

coordinate clauses. The clause begins with the subject and ends with the predicate (or its final part). All the secondary parts are enclosed between them.

Ohthere sæde his hlaforde, Ælfrede cyninge, þæt he ealra Norðmonna norþmest bude.

(Othere said to his lord, King Alfred, that he lived northernmost of all the Northmen (or Norwegians).

But He cwæþ þæt he bude on þæm lande (He said that he lived in the land).

It appears that in many respects the OE syntax was characterized by a wide range of variation and by the co-existence of various, even opposing tendencies.

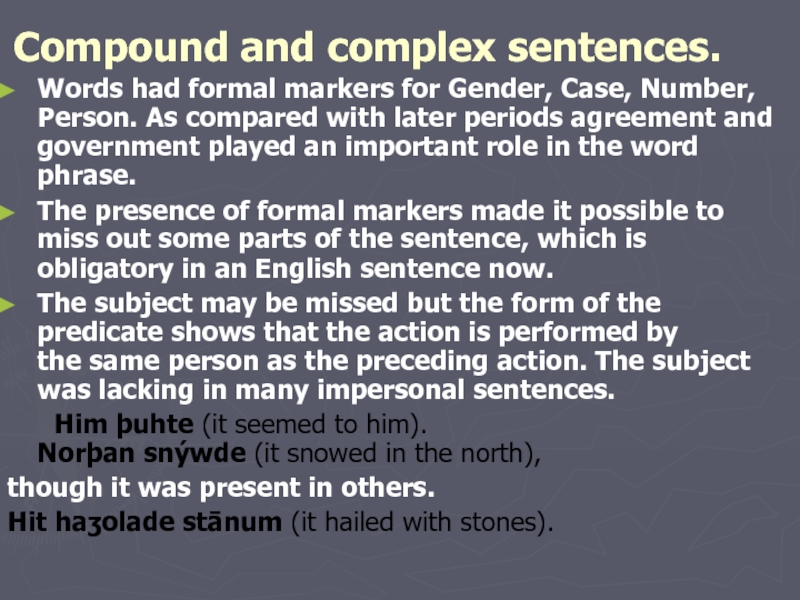

Слайд 9 Compound and complex sentences.

Words had formal markers for Gender, Case,

Number, Person. As compared with later periods agreement and government played an important role in the word phrase.

The presence of formal markers made it possible to miss out some parts of the sentence, which is obligatory in an English sentence now.

The subject may be missed but the form of the predicate shows that the action is performed by the same person as the preceding action. The subject was lacking in many impersonal sentences.

Him þuhte (it seemed to him). Norþan snýwde (it snowed in the north),

though it was present in others.

Hit haʒolade stānum (it hailed with stones).

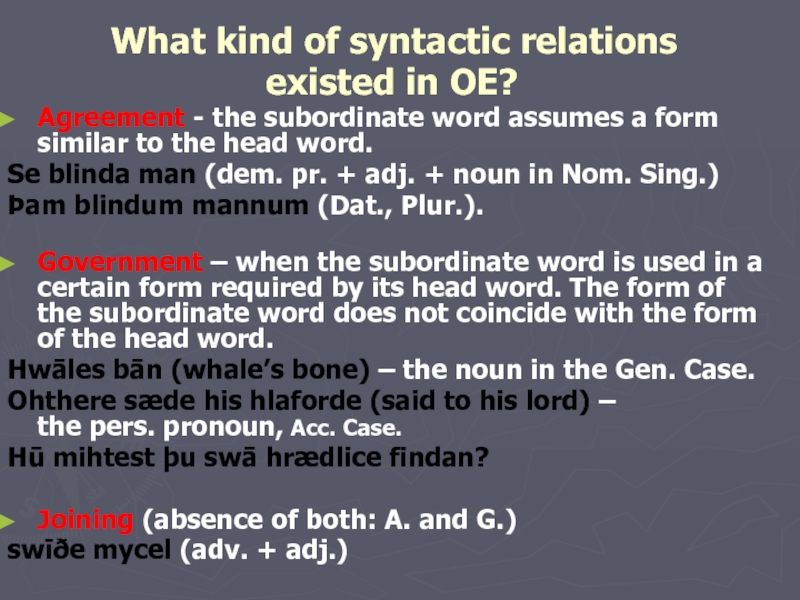

Слайд 10 What kind of syntactic relations

existed in OE?

Agreement —

the subordinate word assumes a form similar to the head word.

Se blinda man (dem. pr. + adj. + noun in Nom. Sing.)

Þam blindum mannum (Dat., Plur.).

Government – when the subordinate word is used in a certain form required by its head word. The form of the subordinate word does not coincide with the form of the head word.

Hwāles bān (whale’s bone) – the noun in the Gen. Case.

Ohthere sæde his hlaforde (said to his lord) – the pers. pronoun, Acc. Case.

Hū mihtest þu swā hrædlice findan?

Joining (absence of both: A. and G.)

swīðe mycel (adv. + adj.)

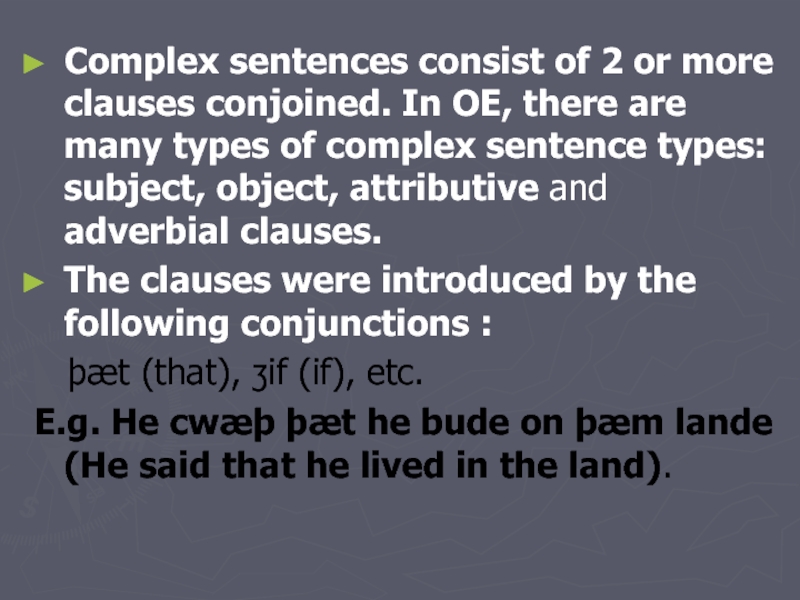

Слайд 11Complex sentences consist of 2 or more clauses conjoined. In OE,

there are many types of complex sentence types: subject, object, attributive and adverbial clauses.

The clauses were introduced by the following conjunctions :

þæt (that), ʒif (if), etc.

E.g. He cwæþ þæt he bude on þæm lande (He said that he lived in the land).

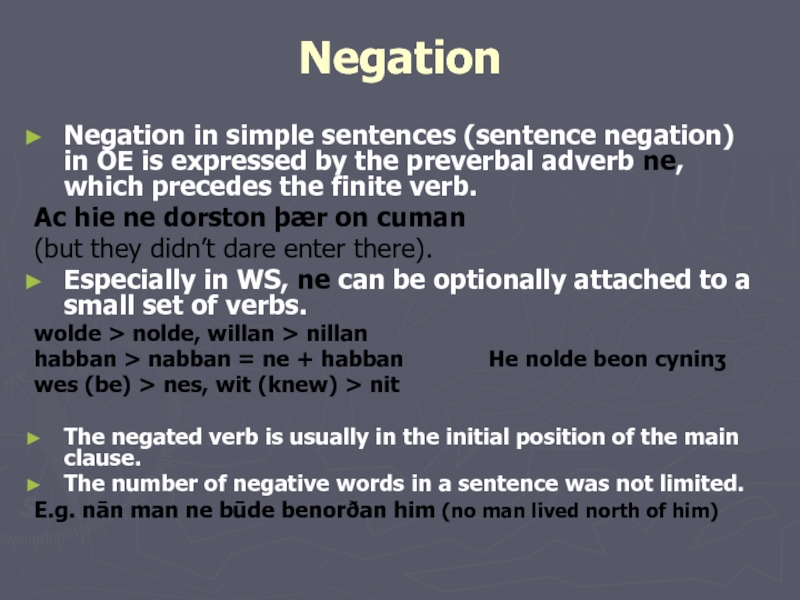

Слайд 12Negation

Negation in simple sentences (sentence negation) in OE is expressed by

the preverbal adverb ne, which precedes the finite verb.

Ac hie ne dorston þær on cuman

(but they didn’t dare enter there).

Especially in WS, ne can be optionally attached to a small set of verbs.

wolde > nolde, willan > nillan

habban > nabban = ne + habban He nolde beon cyninʒ

wes (be) > nes, wit (knew) > nit

The negated verb is usually in the initial position of the main clause.

The number of negative words in a sentence was not limited.

E.g. nān man ne būde benorðan him (no man lived north of him)

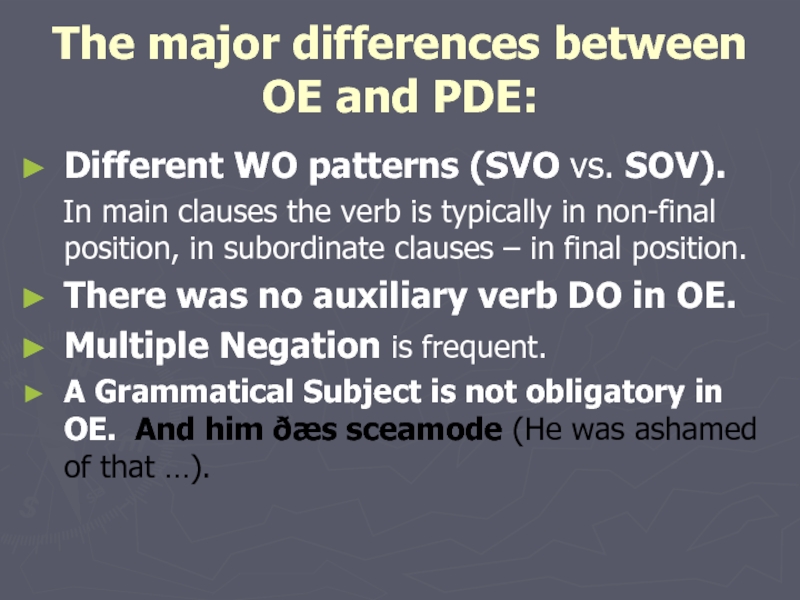

Слайд 13The major differences between OE and PDE:

Different WO patterns (SVO

vs. SOV).

In main clauses the verb is typically in non-final position, in subordinate clauses – in final position.

There was no auxiliary verb DO in OE.

Multiple Negation is frequent.

A Grammatical Subject is not obligatory in OE. And him ðæs sceamode (He was ashamed of that …).

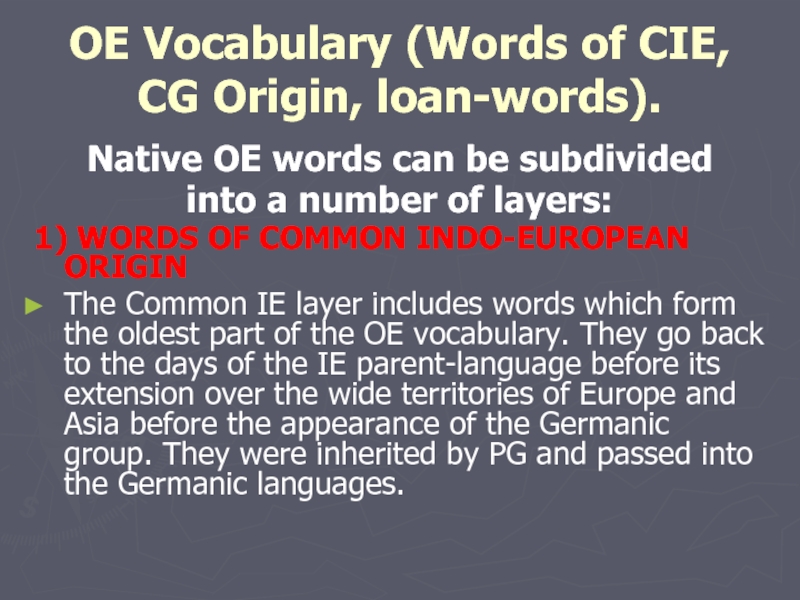

Слайд 14OE Vocabulary (Words of CIE, CG Origin, loan-words).

Native OE words can

be subdivided

into a number of layers:

1) WORDS OF COMMON INDO-EUROPEAN ORIGIN

The Common IE layer includes words which form the oldest part of the OE vocabulary. They go back to the days of the IE parent-language before its extension over the wide territories of Europe and Asia before the appearance of the Germanic group. They were inherited by PG and passed into the Germanic languages.

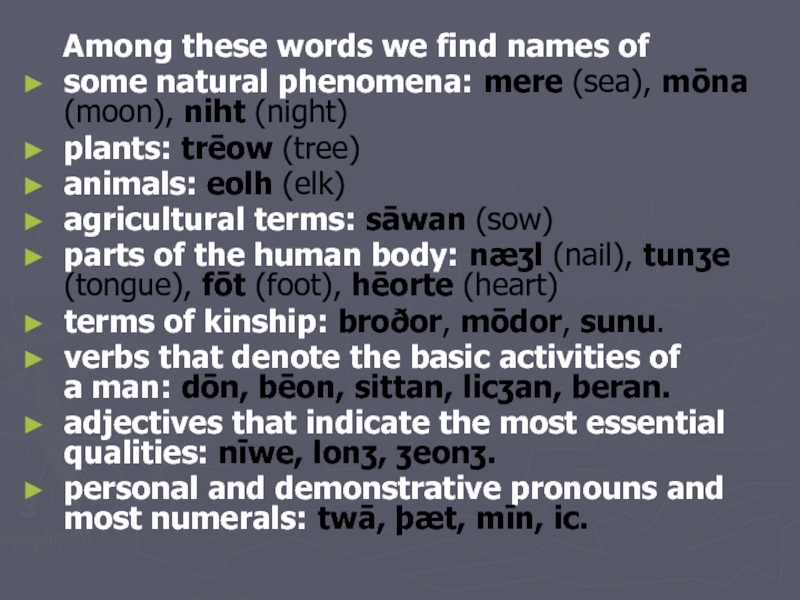

Слайд 15 Among these words we find names of

some natural phenomena:

mere (sea), mōna (moon), niht (night)

plants: trēow (tree)

animals: eolh (elk)

agricultural terms: sāwan (sow)

parts of the human body: næʒl (nail), tunʒe (tongue), fōt (foot), hēorte (heart)

terms of kinship: broðor, mōdor, sunu.

verbs that denote the basic activities of a man: dōn, bēon, sittan, licʒan, beran.

adjectives that indicate the most essential qualities: nīwe, lonʒ, ʒeonʒ.

personal and demonstrative pronouns and most numerals: twā, þæt, mīn, ic.

Слайд 16

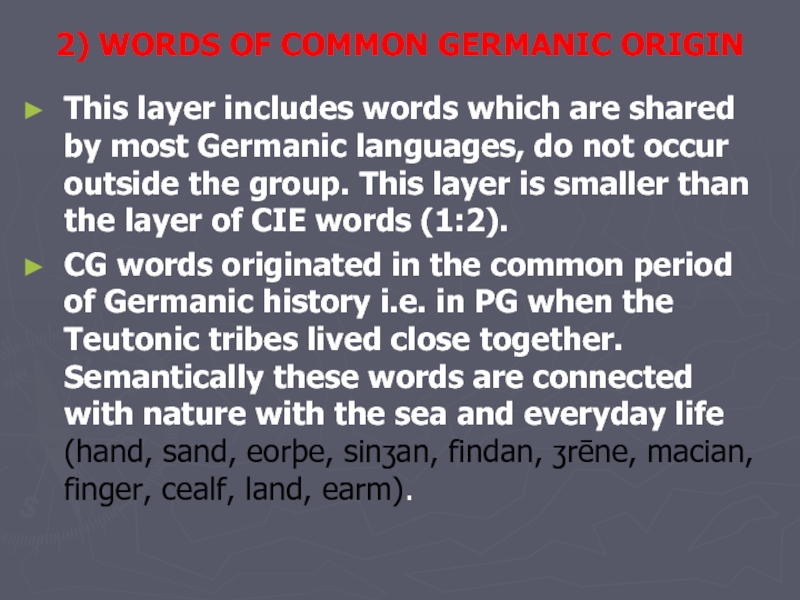

2) WORDS OF COMMON GERMANIC ORIGIN

This layer includes words which

are shared by most Germanic languages, do not occur outside the group. This layer is smaller than the layer of CIE words (1:2).

CG words originated in the common period of Germanic history i.e. in PG when the Teutonic tribes lived close together. Semantically these words are connected with nature with the sea and everyday life (hand, sand, eorþe, sinʒan, findan, ʒrēne, macian, finger, cealf, land, earm).

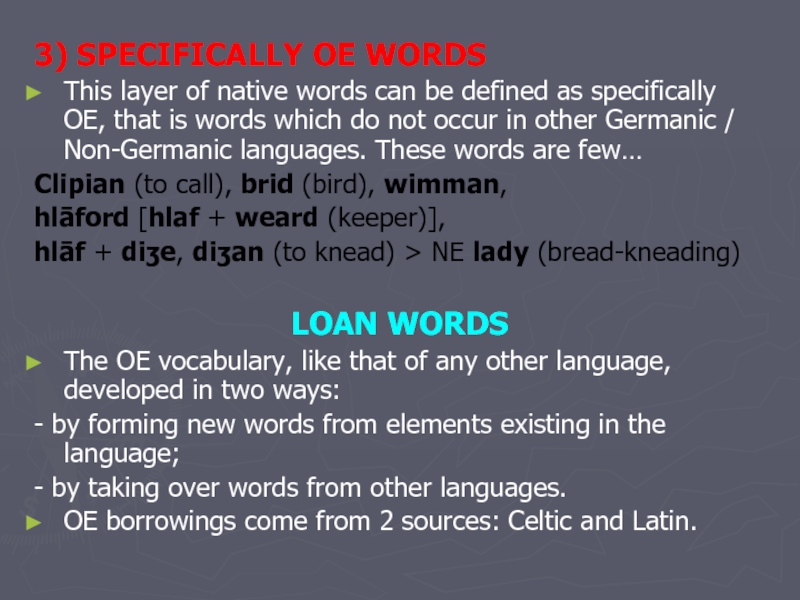

Слайд 173) SPECIFICALLY OE WORDS

This layer of native words can be defined

as specifically OE, that is words which do not occur in other Germanic / Non-Germanic languages. These words are few…

Clipian (to call), brid (bird), wimman,

hlāford [hlaf + weard (keeper)],

hlāf + diʒe, diʒan (to knead) > NE lady (bread-kneading)

LOAN WORDS

The OE vocabulary, like that of any other language, developed in two ways:

— by forming new words from elements existing in the language;

— by taking over words from other languages.

OE borrowings come from 2 sources: Celtic and Latin.

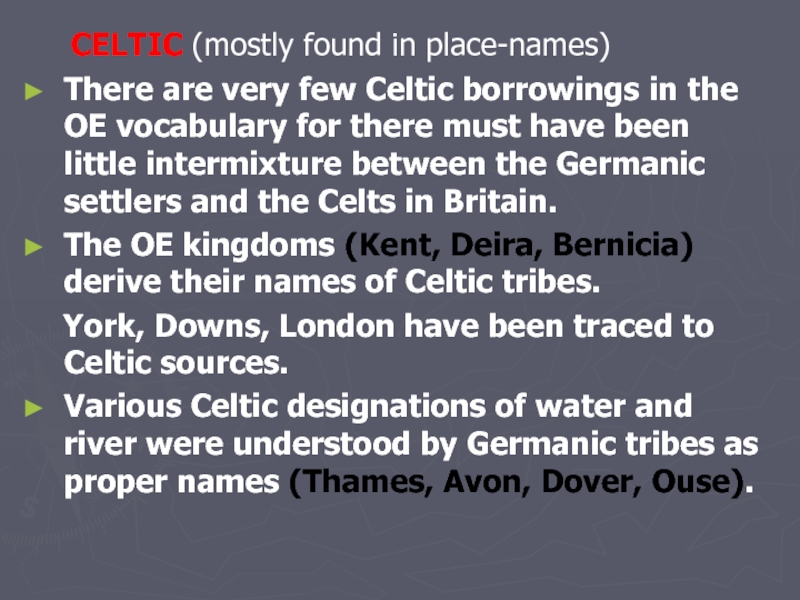

Слайд 18 CELTIC (mostly found in place-names)

There are very few Celtic

borrowings in the OE vocabulary for there must have been little intermixture between the Germanic settlers and the Celts in Britain.

The OE kingdoms (Kent, Deira, Bernicia) derive their names of Celtic tribes.

York, Downs, London have been traced to Celtic sources.

Various Celtic designations of water and river were understood by Germanic tribes as proper names (Thames, Avon, Dover, Ouse).

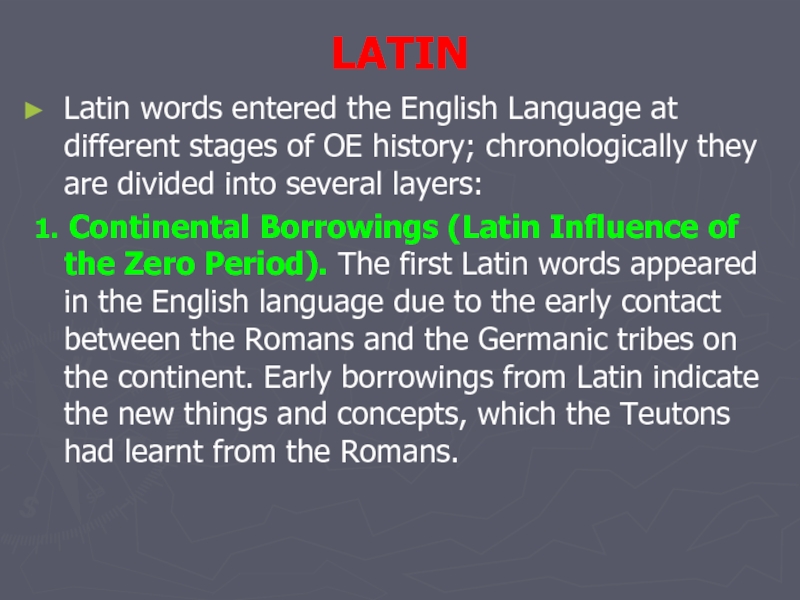

Слайд 20LATIN

Latin words entered the English Language at different stages of

OE history; chronologically they are divided into several layers:

1. Continental Borrowings (Latin Influence of the Zero Period). The first Latin words appeared in the English language due to the early contact between the Romans and the Germanic tribes on the continent. Early borrowings from Latin indicate the new things and concepts, which the Teutons had learnt from the Romans.

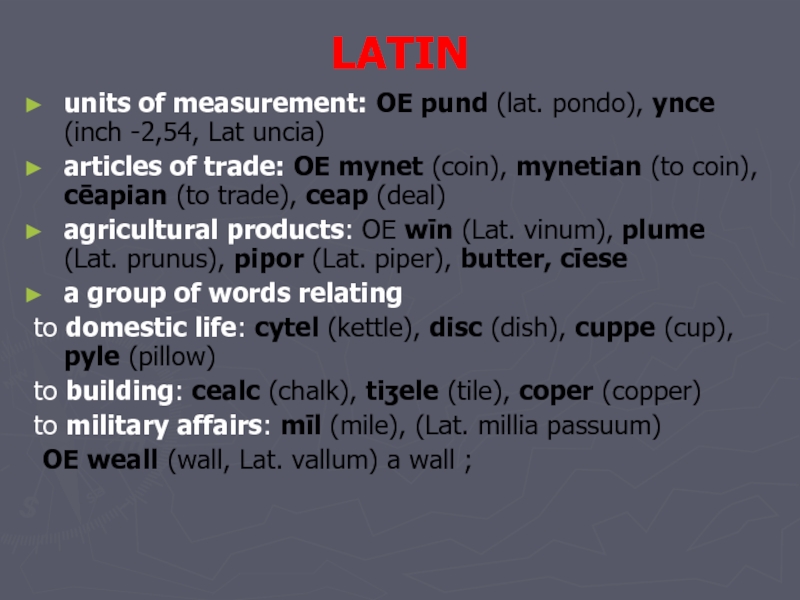

Слайд 21LATIN

units of measurement: OE pund (lat. pondo), ynce (inch -2,54,

Lat uncia)

articles of trade: OE mynet (coin), mynetian (to coin), cēapian (to trade), ceap (deal)

agricultural products: OE wīn (Lat. vinum), plume (Lat. prunus), pipor (Lat. piper), butter, cīese

a group of words relating

to domestic life: cytel (kettle), disc (dish), cuppe (cup), pyle (pillow)

to building: cealc (chalk), tiʒele (tile), coper (copper)

to military affairs: mīl (mile), (Lat. millia passuum)

OE weall (wall, Lat. vallum) a wall ;

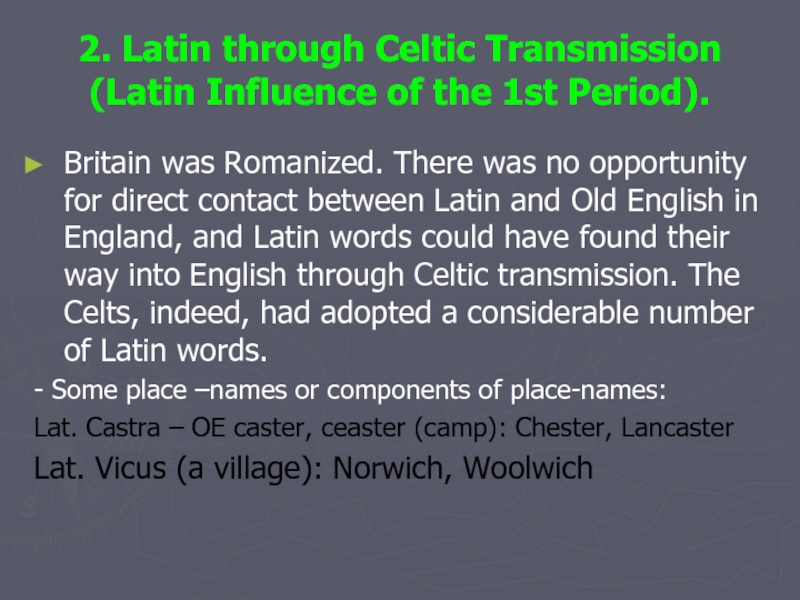

Слайд 222. Latin through Celtic Transmission (Latin Influence of the 1st Period).

Britain

was Romanized. There was no opportunity for direct contact between Latin and Old English in England, and Latin words could have found their way into English through Celtic transmission. The Celts, indeed, had adopted a considerable number of Latin words.

— Some place –names or components of place-names:

Lat. Castra – OE caster, ceaster (camp): Chester, Lancaster

Lat. Vicus (a village): Norwich, Woolwich

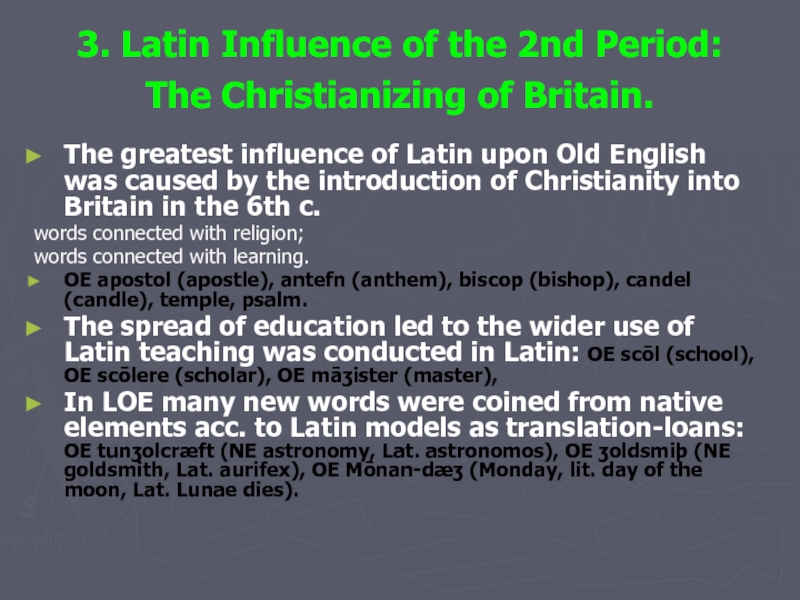

Слайд 233. Latin Influence of the 2nd Period:

The Christianizing of Britain.

The greatest influence of Latin upon Old English was caused by the introduction of Christianity into Britain in the 6th c.

words connected with religion;

words connected with learning.

OE apostol (apostle), antefn (anthem), biscop (bishop), candel (candle), temple, psalm.

The spread of education led to the wider use of Latin teaching was conducted in Latin: OE scōl (school), OE scōlere (scholar), OE māʒister (master),

In LOE many new words were coined from native elements acc. to Latin models as translation-loans: OE tunʒolcræft (NE astronomy, Lat. astronomos), OE ʒoldsmiþ (NE goldsmith, Lat. aurifex), OE Mōnan-dæʒ (Monday, lit. day of the moon, Lat. Lunae dies).

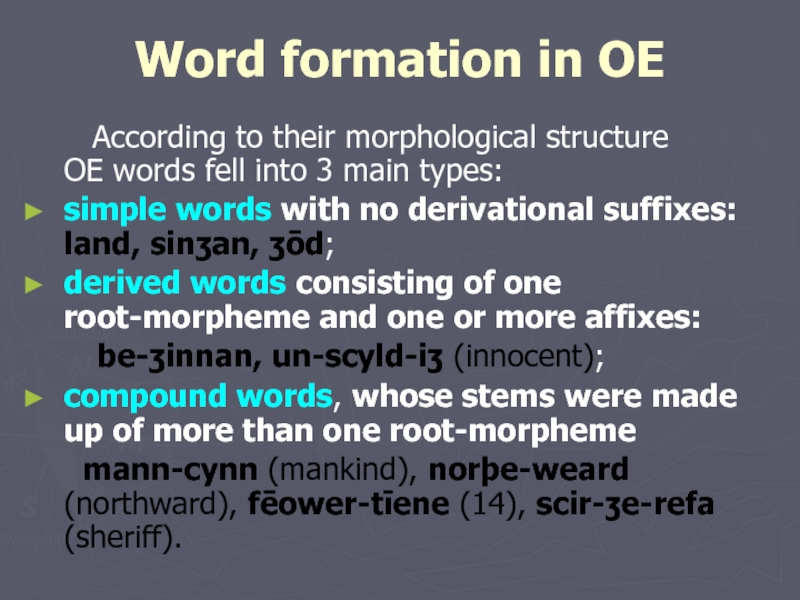

Слайд 24Word formation in OE

According to their morphological

structure OE words fell into 3 main types:

simple words with no derivational suffixes: land, sinʒan, ʒōd;

derived words consisting of one root-morpheme and one or more affixes:

be-ʒinnan, un-scyld-iʒ (innocent);

compound words, whose stems were made up of more than one root-morpheme

mann-cynn (mankind), norþe-weard (northward), fēower-tīene (14), scir-ʒe-refa (sheriff).

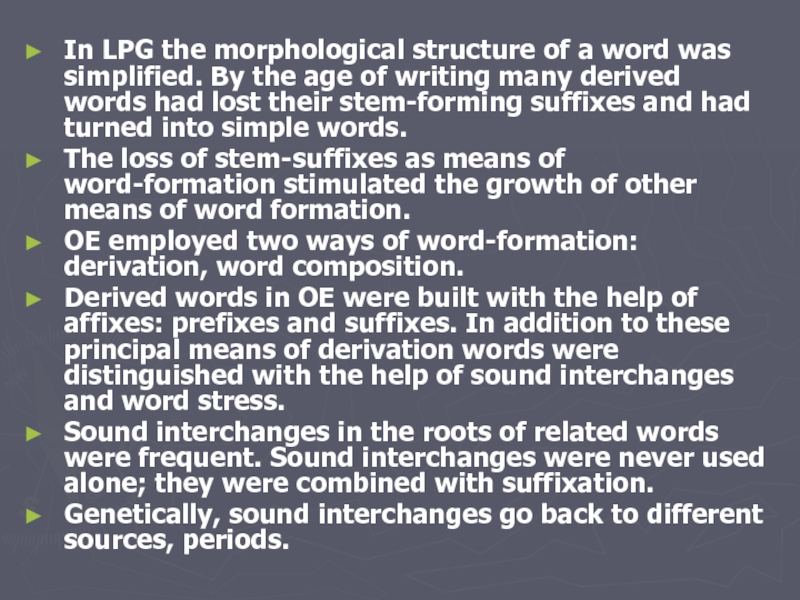

Слайд 25In LPG the morphological structure of a word was simplified. By

the age of writing many derived words had lost their stem-forming suffixes and had turned into simple words.

The loss of stem-suffixes as means of word-formation stimulated the growth of other means of word formation.

OE employed two ways of word-formation: derivation, word composition.

Derived words in OE were built with the help of affixes: prefixes and suffixes. In addition to these principal means of derivation words were distinguished with the help of sound interchanges and word stress.

Sound interchanges in the roots of related words were frequent. Sound interchanges were never used alone; they were combined with suffixation.

Genetically, sound interchanges go back to different sources, periods.