In English grammar, a word class is a set of words that display the same formal properties, especially their inflections and distribution. The term «word class» is similar to the more traditional term, part of speech. It is also variously called grammatical category, lexical category, and syntactic category (although these terms are not wholly or universally synonymous).

The two major families of word classes are lexical (or open or form) classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs) and function (or closed or structure) classes (determiners, particles, prepositions, and others).

Examples and Observations

- «When linguists began to look closely at English grammatical structure in the 1940s and 1950s, they encountered so many problems of identification and definition that the term part of speech soon fell out of favor, word class being introduced instead. Word classes are equivalent to parts of speech, but defined according to strict linguistic criteria.» (David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2003)

- «There is no single correct way of analyzing words into word classes…Grammarians disagree about the boundaries between the word classes (see gradience), and it is not always clear whether to lump subcategories together or to split them. For example, in some grammars…pronouns are classed as nouns, whereas in other frameworks…they are treated as a separate word class.» (Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker, Edmund Weiner, The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 2014)

Form Classes and Structure Classes

«[The] distinction between lexical and grammatical meaning determines the first division in our classification: form-class words and structure-class words. In general, the form classes provide the primary lexical content; the structure classes explain the grammatical or structural relationship. Think of the form-class words as the bricks of the language and the structure words as the mortar that holds them together.»

The form classes also known as content words or open classes include:

- Nouns

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

The structure classes, also known as function words or closed classes, include:

- Determiners

- Pronouns

- Auxiliaries

- Conjunctions

- Qualifiers

- Interrogatives

- Prepositions

- Expletives

- Particles

«Probably the most striking difference between the form classes and the structure classes is characterized by their numbers. Of the half million or more words in our language, the structure words—with some notable exceptions—can be counted in the hundreds. The form classes, however, are large, open classes; new nouns and verbs and adjectives and adverbs regularly enter the language as new technology and new ideas require them.» (Martha Kolln and Robert Funk, Understanding English Grammar. Allyn and Bacon, 1998)

One Word, Multiple Classes

«Items may belong to more than one class. In most instances, we can only assign a word to a word class when we encounter it in context. Looks is a verb in ‘It looks good,’ but a noun in ‘She has good looks‘; that is a conjunction in ‘I know that they are abroad,’ but a pronoun in ‘I know that‘ and a determiner in ‘I know that man’; one is a generic pronoun in ‘One must be careful not to offend them,’ but a numeral in ‘Give me one good reason.'» (Sidney Greenbaum, Oxford English Grammar. Oxford University Press, 1996)

Suffixes as Signals

«We recognize the class of a word by its use in context. Some words have suffixes (endings added to words to form new words) that help to signal the class they belong to. These suffixes are not necessarily sufficient in themselves to identify the class of a word. For example, -ly is a typical suffix for adverbs (slowly, proudly), but we also find this suffix in adjectives: cowardly, homely, manly. And we can sometimes convert words from one class to another even though they have suffixes that are typical of their original class: an engineer, to engineer; a negative response, a negative.» (Sidney Greenbaum and Gerald Nelson, An Introduction to English Grammar, 3rd ed. Pearson, 2009)

A Matter of Degree

«[N]ot all the members of a class will necessarily have all the identifying properties. Membership in a particular class is really a matter of degree. In this regard, grammar is not so different from the real world. There are prototypical sports like ‘football’ and not so sporty sports like ‘darts.’ There are exemplary mammals like ‘dogs’ and freakish ones like the ‘platypus.’ Similarly, there are good examples of verbs like watch and lousy examples like beware; exemplary nouns like chair that display all the features of a typical noun and some not so good ones like Kenny.» (Kersti Börjars and Kate Burridge, Introducing English Grammar, 2nd ed. Hodder, 2010)

Word for Microsoft 365 Word for Microsoft 365 for Mac Word 2021 Word 2021 for Mac Word 2019 Word 2019 for Mac Word 2016 Word 2016 for Mac Word 2013 Word 2010 Word for Mac 2011 More…Less

To create a form in Word that others can fill out, start with a template or document and add content controls. Content controls include things like check boxes, text boxes, date pickers, and drop-down lists. If you’re familiar with databases, these content controls can even be linked to data.

Show the Developer tab

If the developer tab isn’t displayed in the ribbon, see Show the Developer tab.

Open a template or a blank document on which to base the form

To save time, start with a form template or start from scratch with a blank template.

-

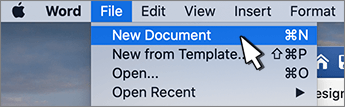

Go to File > New.

-

In Search online templates, type Forms or the type of form you want and press ENTER.

-

Choose a form template, and then select Create or Download.

-

Go to File > New.

-

Select Blank document.

Add content to the form

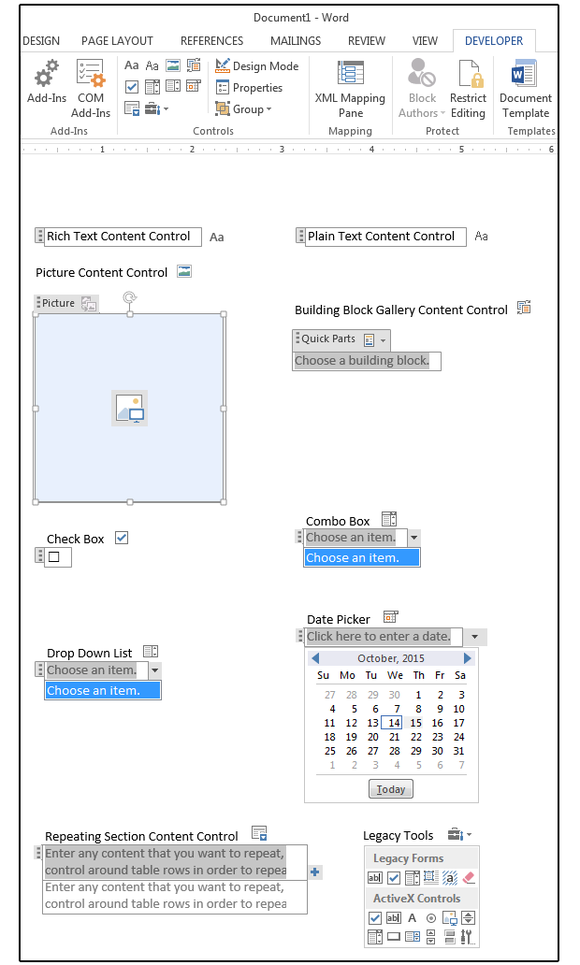

Go to Developer, and then choose the controls that you want to add to the document or form. To remove a content control, select the control and press Delete. You can set properties on controls once inserted.

Note: You can print a form that was created using content controls, but the boxes around the content controls will not print.

In a rich text content control, users can format text as bold or italic, and they can type multiple paragraphs. If you want to limit what users add, insert the plain text content control.

-

Click or tap where you want to insert the control.

-

Select Developer > Rich Text Content Control

or Plain Text Content Control

.

To set specific properties on the control, see Set or change properties for content controls.

A picture control is often used for templates, but you can also add a picture control to a form.

-

Click or tap where you want to insert the control.

-

Select Developer > Picture Content Control

.

To set specific properties on the control, see Set or change properties for content controls.

Use building block controls when you want people to choose a specific block of text. For example, building block controls are helpful when you need to add different boilerplate text depending on the contract’s specific requirements. You can create rich text content controls for each version of the boilerplate text, and then you can use a building block control as the container for the rich text content controls.

-

Click or tap where you want to insert the control.

-

Go to DeveloperBuilding Block Gallery Content Control

(or Building Block Content Control).

-

Select Developer and content controls for the building block.

-

Click or tap where you want to insert the control.

To set specific properties on the control, see Set or change properties for content controls.

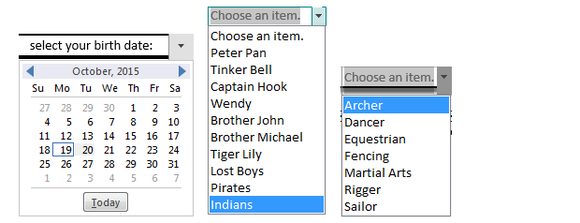

In a combo box, users can select from a list of choices that you provide or they can type in their own information. In a drop-down list, users can only select from the list of choices.

-

Go to Developer > Combo Box Content Control

or Drop-Down List Content Control

.

-

Select the content control, and then select Properties.

-

To create a list of choices, select Add under Drop-Down List Properties.

-

Type a choice in Display Name, such as Yes, No, or Maybe.

Repeat this step until all of the choices are in the drop-down list.

-

Fill in any other properties that you want.

Note: If you select the Contents cannot be edited check box, users won’t be able to click a choice.

-

Click or tap where you want to insert the date picker control.

-

Select Developer > Date Picker Content Control

.

To set specific properties on the control, see Set or change properties for content controls.

-

Click or tap where you want to insert the check box control.

-

Select Developer > Check Box Content Control

.

To set specific properties on the control, see Set or change properties for content controls.

Legacy form controls are for compatibility with older versions of Word and consist of legacy form and Active X controls.

-

Click or tap where you want to insert a legacy control.

-

Go to Developer > Legacy Forms

drop-down.

-

Select the Legacy Form control or Active X Control that you want to include.

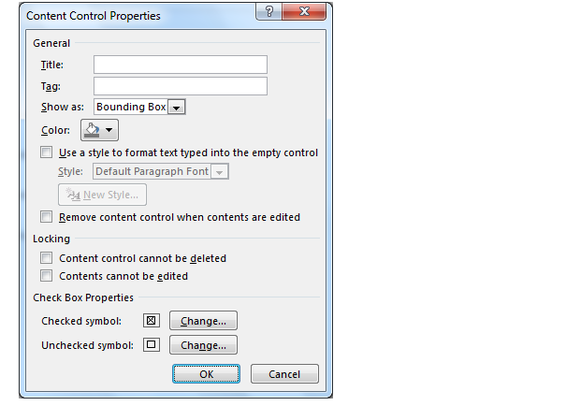

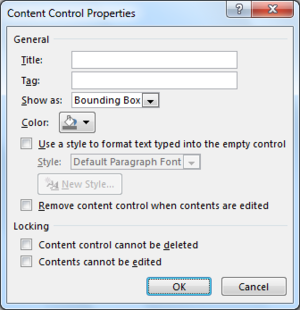

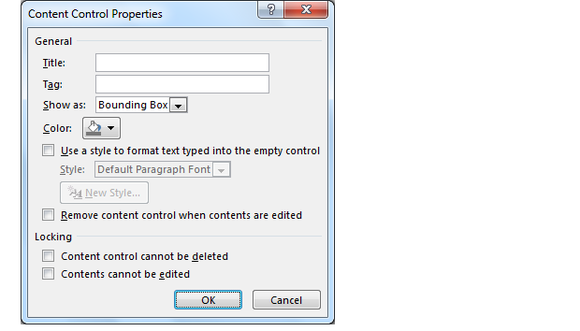

Set or change properties for content controls

Each content control has properties that you can set or change. For example, the Date Picker control offers options for the format you want to use to display the date.

-

Select the content control that you want to change.

-

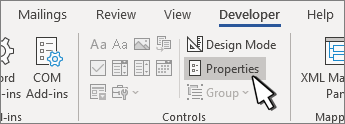

Go to Developer > Properties.

-

Change the properties that you want.

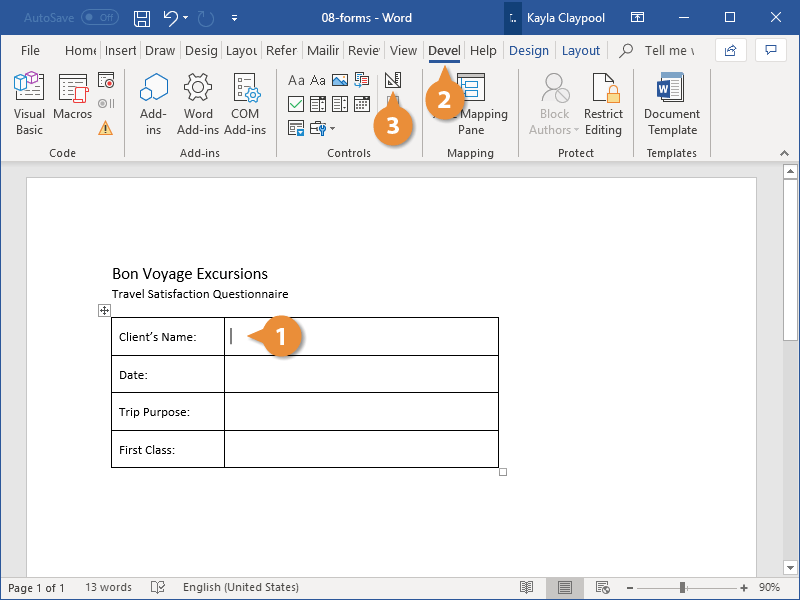

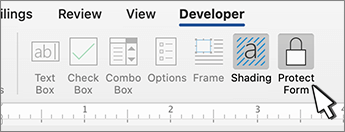

Add protection to a form

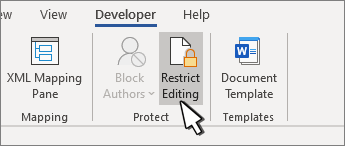

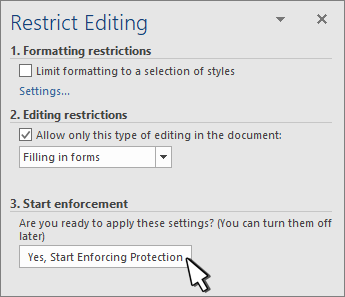

If you want to limit how much others can edit or format a form, use the Restrict Editing command:

-

Open the form that you want to lock or protect.

-

Select Developer > Restrict Editing.

-

After selecting restrictions, select Yes, Start Enforcing Protection.

Advanced Tip:

If you want to protect only parts of the document, separate the document into sections and only protect the sections you want.

To do this, choose Select Sections in the Restrict Editing panel. For more info on sections, see Insert a section break.

Show the Developer tab

If the developer tab isn’t displayed in the ribbon, see Show the Developer tab.

Open a template or use a blank document

To create a form in Word that others can fill out, start with a template or document and add content controls. Content controls include things like check boxes, text boxes, and drop-down lists. If you’re familiar with databases, these content controls can even be linked to data.

-

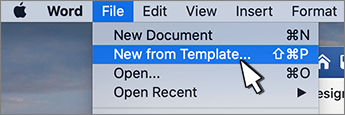

Go to File > New from Template.

-

In Search, type form.

-

Double-click the template you want to use.

-

Select File > Save As, and pick a location to save the form.

-

In Save As, type a file name and then select Save.

-

Go to File > New Document.

-

Go to File > Save As.

-

In Save As, type a file name and then select Save.

Add content to the form

Go to Developer, and then choose the controls that you want to add to the document or form. To remove a content control, select the control and press Delete. You can set Options on controls once inserted. From Options, you can add entry and exit macros to run when users interact with the controls, as well as list items for combo boxes, .

-

In the document, click or tap where you want to add a content control.

-

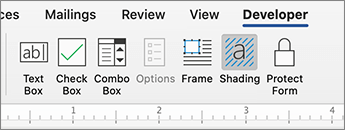

On Developer, select Text Box, Check Box, or Combo Box.

-

To set specific properties for the control, select Options, and set .

-

Repeat steps 1 through 3 for each control that you want to add.

Options let you set common settings, as well as control specific settings. Select a control and then select Options to set up or make changes.

-

Set common properties.

-

Select Macro to Run on lets you choose a recorded or custom macro to run on Entry or Exit from the field.

-

Bookmark Set a unique name or bookmark for each control.

-

Calculate on exit This forces Word to run or refresh any calculations, such as total price when the user exits the field.

-

Add Help Text Give hints or instructions for each field.

-

OK Saves settings and exits the panel.

-

Cancel Forgets changes and exits the panel.

-

-

Set specific properties for a Text box

-

Type Select form Regular text, Number, Date, Current Date, Current Time, or Calculation.

-

Default text sets optional instructional text that’s displayed in the text box before the user types in the field. Set Text box enabled to allow the user to enter text into the field.

-

Maximum length sets the length of text that a user can enter. The default is Unlimited.

-

Text format can set whether text automatically formats to Uppercase, Lowercase, First capital, or Title case.

-

Text box enabled Lets the user enter text into a field. If there is default text, user text replaces it.

-

-

Set specific properties for a Check box.

-

Default Value Choose between Not checked or checked as default.

-

Checkbox size Set a size Exactly or Auto to change size as needed.

-

Check box enabled Lets the user check or clear the text box.

-

-

Set specific properties for a Combo box

-

Drop-down item Type in strings for the list box items. Press + or Enter to add an item to the list.

-

Items in drop-down list Shows your current list. Select an item and use the up or down arrows to change the order, Press — to remove a selected item.

-

Drop-down enabled Lets the user open the combo box and make selections.

-

-

Go to Developer > Protect Form.

Note: To unprotect the form and continue editing, select Protect Form again.

-

Save and close the form.

If you want, you can test the form before you distribute it.

-

Protect the form.

-

Reopen the form, fill it out as the user would, and then save a copy.

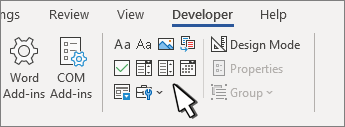

Show the Developer tab

-

On the right side of the ribbon, select

, and then select Ribbon Preferences.

-

Under Customize, select Developer .

Open a template or a document on which to base the form

You can start with a blank document and create your own form. Or, to save time, you can start with a form template.

-

Go to File > New from Template.

-

In the left pane, expand Online Templates, and then select Forms.

-

Double-click the form template that you want to use.

Add content controls to the form

-

In the document, click where you want to add the control.

-

On the Developer tab, under Form Controls, select Text Box, Check Box, or Combo Box.

-

To set specific properties for the control, select Options, and then configure the properties that you want.

Note: To create a list of drop-down items in a combo box, select the combo box placeholder, click Options, and then add the items that you want to appear in the drop-down list.

-

Repeat steps 1 through 3 for each control that you want to add.

Add instructional text (optional)

Instructional text (for example, «Type First Name») in a text box can make your form easier to use. By default, no text appears in a text box, but you can add it.

-

Select the text box control that you want to add instructional text to.

-

On the Developer tab, under Form Controls, select Options.

-

In Default Text, type the instructional text.

-

Make sure that Fill-in enabled is selected, and then select OK.

Protect the form

-

On the Developer tab, under Form Controls, select Protect Form.

Note: To unprotect the form and continue editing, click Protect Form again.

-

Save and close the form.

Test the form (optional)

If you want, you can test the form before you distribute it.

-

Protect the form.

-

Reopen the form, fill it out as the user would, and then save a copy.

Creating fillable forms isn’t available in Word for the web.

You can create the form with the desktop version of Word with the instructions in Create a fillable form.

When you save the document and reopen it in Word for the web, you’ll see the changes you made.

Need more help?

You can use Word to create interactive digital forms that other people can fill out on their computers before printing or sending them back to you. It takes a little preparation but keeps you from having to decipher messy handwriting! Some of the tools you will use when creating a form include:

- Templates: Forms are normally saved as templates so that they can be used again and again.

- Content controls: The areas where users input information in a form.

- Tables: Tables are often used in forms to align text and form fields, and to create borders and boxes.

- Protection: Users can complete the form fields without being able to change the form’s text and/or design.

Show the Developer Tab

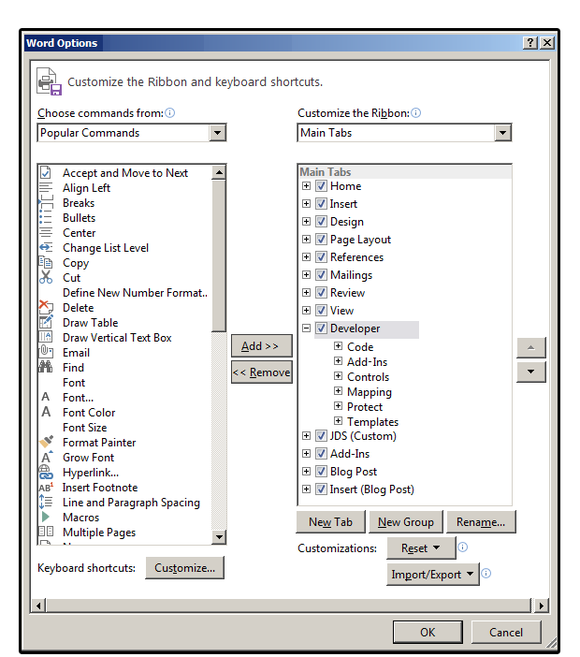

Before you can create a form, you’ll need to turn on the Developer tab to get access to the advanced tools.

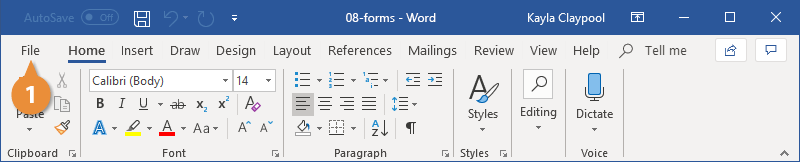

- Click the File tab.

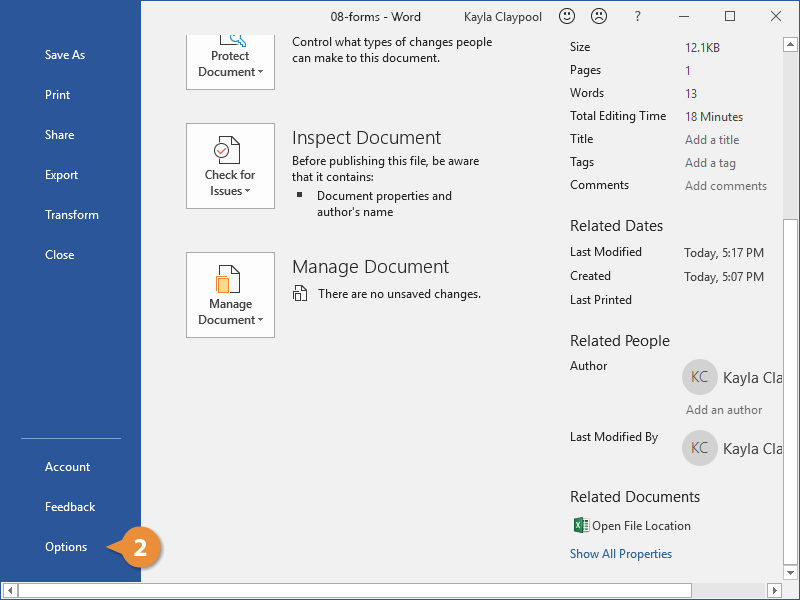

- Select Options.

The Word Options window opens.

- Click the Customize Ribbon tab on the left.

The column on the right controls which ribbon tabs are enabled.

- Check the Developer check box.

- Click OK.

The Developer tab now appears on the ribbon. In addition to advanced tools for macro recording, add-ins, and document protection, we now have access to form controls.

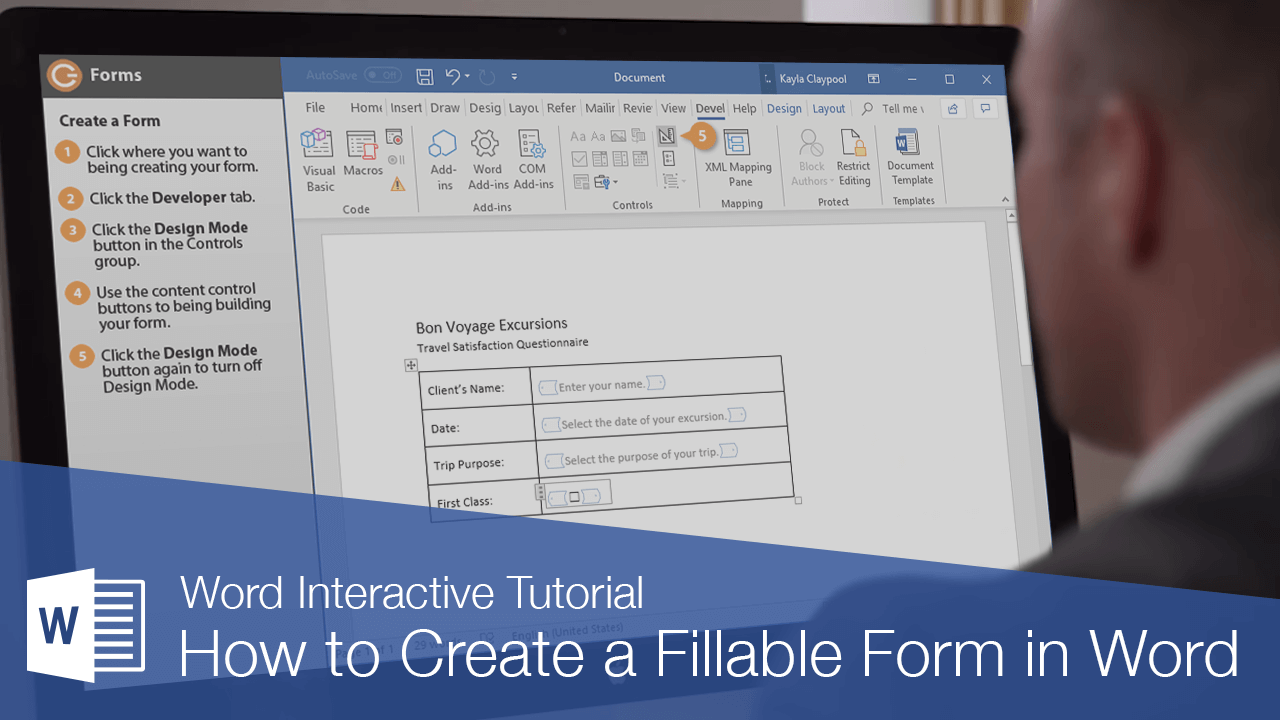

Create a Form

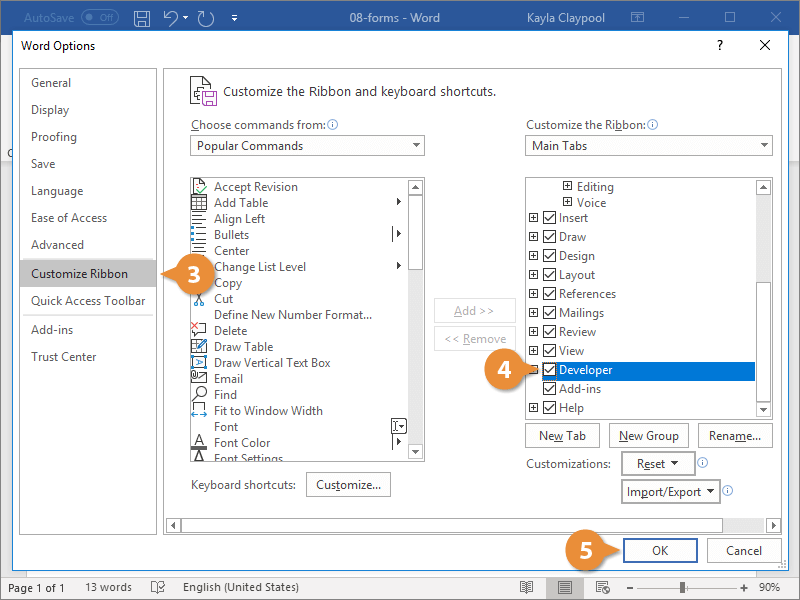

Once you’ve enabled the Developer tab, and created the layout and structure of the form, you can start adding form fields to your document with Content Controls.

- Place the text cursor where you want to insert the form field.

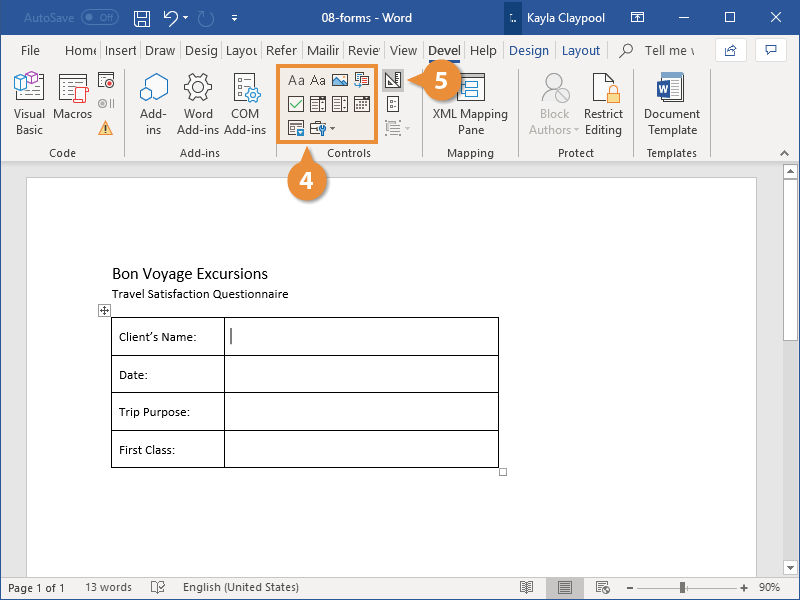

- Click the Developer tab on the ribbon.

The Controls group contains the different kinds of content controls you can add to a form, as well as the toggle button for Design Mode.

- Click the Design Mode button in the controls group.

While Design Mode is active, controls you insert won’t be active, so clicking a check box to move it around won’t also check it. You can also customize placeholder text for some controls.

- Click a Content Control buttons to insert the selected type of control.

The content control is inserted.

Select a form field and click the Properties button on the ribbon to edit a control’s options. Depending on the type of control you’ve inserted, you can change its appearance, set up the options in a list, or lock the control once edited.

- When you’re done, click the Design Mode button again to exit Design Mode.

You leave Design Mode, and the content controls that you’ve inserted can now be used.

Types of Form Controls

There are many different types of form controls you can add to a form that will allow people to add different types of responses.

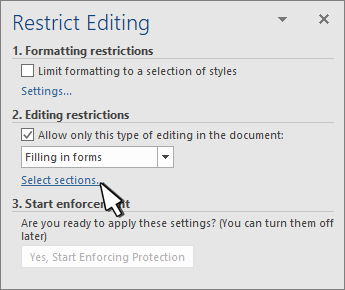

Finalize a Form

When you’re ready to distribute a form so others can fill it out, you can restrict the form so that content controls cannot be removed or changed by those filling it out.

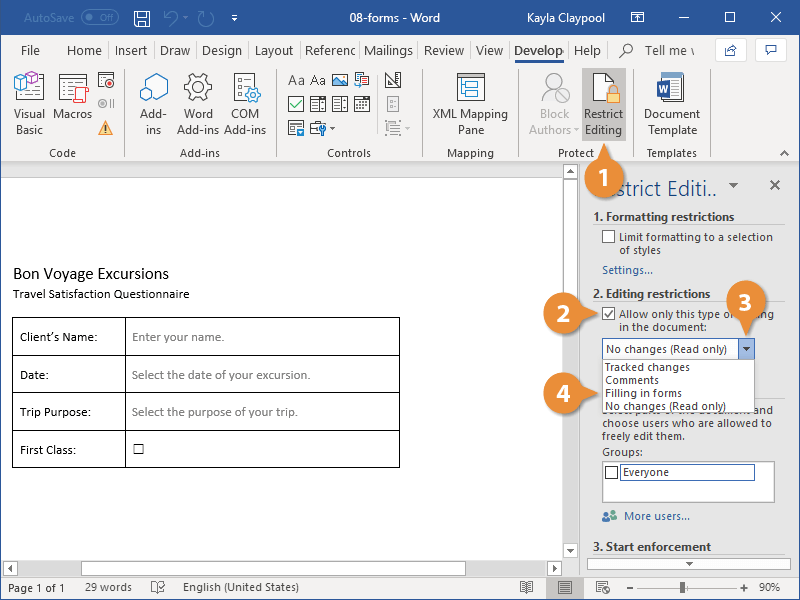

- Click the Restrict Editing button on the Developer tab.

The Restrict Editing pane appears on the right.

- Check the Editing restrictions check box.

- Click the Editing restriction list arrow.

- Select Filling in forms.

When this option is enabled, the only change that anyone else can make to this document is the filling in of form fields. They won’t be able to move, delete, or edit the fields themselves until protection is turned off.

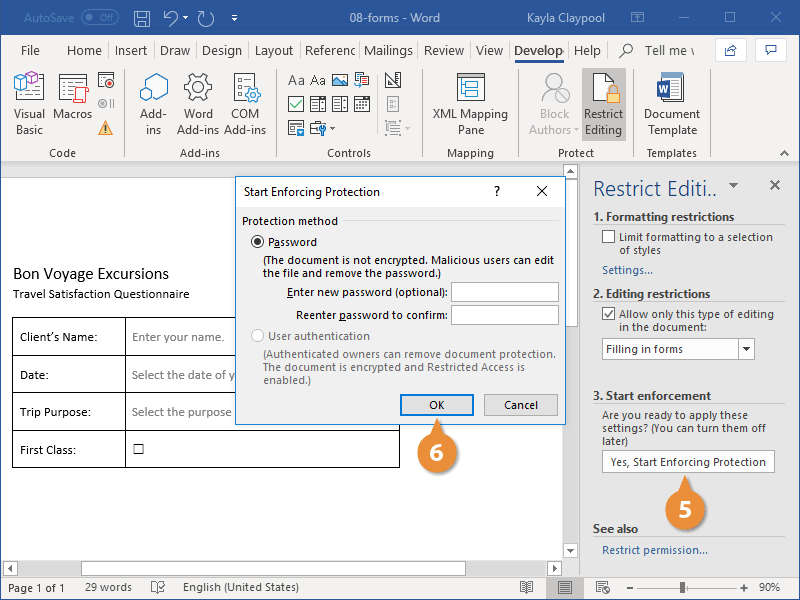

- Click the Yes, Start Enforcing Protection button.

A password is not required to start enforcing protection, but you can add one if you’d like to prevent just anyone from turning this protection off.

- Enter a password (optional), then click OK.

The document is now restricted, and anyone you send it to will only be able to fill in the forms.

FREE Quick Reference

Click to Download

Free to distribute with our compliments; we hope you will consider our paid training.

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar

In 3rd person singular, the personal, reflexive, and possessive pronouns distinguish in gender between masculine (he/him/himself/ his), and non-personal (it/itself/its). Relative and interrogative pronouns and determiners distinguish between personal and non-personal gender.

The 2nd person uses a common form for singular and plural in the personal and possessive series but has a separate plural in the reflexive (yourself, yourselves). «We», the 1st person plural pronoun, does not denote «more than I» (cf.: the boy — the boys) but «I plus one or more others». There is thus an interrelation between number and person. We may exclude the person(s) addressed.

Questions:

1.What parts of speech do the authors identify? How do they classify them?

2.What common features of pronouns do they point out?

3.What casal forms of the pronouns do they single out?

4.What subclasses of pronouns is the category of person relevant for?

5.What classification types of pronouns are gender sensitive?

6.What subclasses of pronouns have number distinctions?

4.

HillA.Introduction to

Linguistic Structures

Form Classes

In English words and fixed phrases are divided into two groups: those which can take suffixes and prefixes, that is to say, those which are inflectable; and those which can take only prebases and postbases and which are therefore uninflectable. Suffixes and prefixes are added to bases in intersecting and largely symmetrical sets called paradigms. A typical paradigm is that for nouns, where a given form is classified according to the 2 variations, or categories, of case and

|

fegeminar 4. Grammatical Classes of Words |

99 |

I number. Since the paradigmatic sets are sharply different for large’ groups of words, words fall into classes defined by their paradigms. I [These large groups are called form classes, though the traditional I name for them is parts of speech.

English possesses three classes of inflected words: nouns, pro-t- nouns, and verbs. […]

Paradigmatic characteristics will not, however, identify all memIbers of these classes since some of them are defective, lacking all or [some of the expected set of suffixes. In complex words which are thus ^defective, the normal next step is to look at any postbases the form i may contain, since other constructions containing the same postbase may be fully inflectable. If this should be the case, the postbase defines the class of the defective constructions. Thus the analyst may |: find himself with such a form as «greenness», which cannot be imme-1 diately classified as a noun, since it is not usually inflected for number f’Or case. But the same postbase occurs in «kindness», where it is regu- i’larly inflected for number, giving «kindnesses». As a result, the ana-j lyst has no hesitation in calling «greenness» a noun. One of the ad-I vantages of a complete and indexed morphemic lexicon of English ^would be that it would bring together all constructions containing the same postbase, so that this kind of analysis would be greatly simplified. […]

If there were a morphemic lexicon, the formation of English words could be much more fully described than is possible at present, and individual postbases and prebases could be extensively used in assigning words to their proper form classes. […]

We can start a series like «the slow cars», «the slower cars», «the slowest cars». Phonologically each series is a single phrase, that is, is not interrupted by any juncture other than /+/. We know that the last word in each is a noun, as proved by the suffixes it may appear with. We can then use the series to set up a tentative definition of one group of adjectives: any word which can be modified by the addition of [- ] and [-ist] is an adjective.

The definition is not complete, however, since the resultant word has to have the syntactic and morphological characteristics of «slow, slower, slowest» and, negatively, must lack the characteristics of any other form class. Thus, for instance, «type, typer, typist» might be

|

100 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

thought of as a series which contains adjectives. The series does not have the distribution of «slow, slower, slowest». We can say «a slower car than mine» or «the slowest car in the group». We cannot fit «typer» or «typist» into this series, or even into a series involving other nouns, such as «boy» or «talk». Negatively, a form such as «typist» has the inflectional characteristics of a noun, as in «the typist’s coat». For these reasons, then, the series «typer, typist» does not contain the same morphemes as «slower, slowest»; and «type, typer, typist» are not adjectives. To be complete, our preliminary definition should read: any word having the distributional characteristics of «slow» and capable of being modified by the addition of «-er» and «- est» is an adjective, and the resultant constructions containing the postbases «-er» and «-est» are also adjectives…

More important than this difficulty in terminology is the fact that our definition — any word having the distributional characteristics of «slow» and capable of being modified by the addition of «-er» and «- est» is an adjective, and the resultant constructions containing the postbases «-er» and «-est» are also adjectives — runs counter to most, if not all, traditional definitions. It is usual, for instance, to define «slower» as an adverb in such sentences as «The car runs slower», which our definition denies. The traditional definition is based on meaning, whereas ours has as usual attempted to rely on form and distribution. Even in this situation, then, we shall call «slower» an adjective and shall describe the peculiarities of distribution of adjectives after verbs when we describe the elements of sentences…

Questions:

1.What are A. Hill’s criteria of identifying form classes?

2.What do distributional characteristics of the word show?

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

|

-Seminar 4. Grammatical Classes of Words |

101 |

5.

Jespersen O. The

Philosophy of Grammar

Chapter VII. THE

THREE RANKS.

i Subordination. Substantives. Adjectives. Pronouns. Verbs.

Adverbs. Word Groups. Clauses. Final Remarks

i* Subordination

1» The question of the class into which a word should be. put -whether «that of substantives or adjectives, or some other — is one that concterns the word in itself. Some answer to that question will therefore foe found in dictionaries.5 We have now to consider combinations of %ords, and here we shall find that though a substantive always reriiains a substantive and an adjective an adjective, there is a certain scheme of subordination in connected speech which is analogous to iftie distribution of words into «parts of speech», without being entirely dependent on it.

In any composite denomination of a thing or person […], we altoays find that there is one word of supreme importance to which the others are joined as subordinates. This chief word is defined (qualified, modified) by another word, which in its turn may be defined (qualified, modified) by a third word, etc. We are thus led to establish different «ranks» of words according to their mutual relations as ‘defined or defining. In the combination extremely hot weather the last word weather, which is evidently the chief idea, may be called ternary; hot, which defines weather, secondary, and extremely, which defines hot, tertiary. Though a tertiary word may be further defined

Note, however, that any word, or group of words, or part of a word, may be turned into a substantive when treated as a quotation word, e.g. your late was misheard as light I his speech abounded in / think so’s I there should be two I’s in his name.

|

102 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

by a (quaternary) word, and this again by a (quinary) word, and so forth, it is needless to distinguish more than three ranks, as there are no formal or other traits that distinguish words of these lower orders from tertiary words. Thus, in the phrase a certainly not very cleverly worded remark, no one of the words certainly, not, and very, though defining the following word, is in any way grammatically different from what it would be as a tertiary word, as it is in certainly a clever remark, not a clever remark, a very clever remark.

If now we compare the combination a furiously barking dog (a dog barking furiously), in which dog is primary, barking secondary, and furiously tertiary, with the dog barks furiously, it is evident that the same subordination obtains in the latter as in the former combination. Yet there is a fundamental difference between them, which calls for separate terms for the two kinds of combination: we shall call the former kind junction, and the latter nexus. […] we shall see that there are other types of nexus besides the one seen in the dog barks. It should be noted that the dog is a primary not only when it is the subject, as in the dog barks, but also when it is the object of a verb, as in I see the dog, or of a preposition, as in he runs after the dog.

As regards terminology, the words primary, secondary, and tertiary are applicable to nexus as well as to junction, but it will be useful to have the special names adjunct for a secondary word in a junction, and adnex for a secondary word in a nexus. For tertiary we may use the term subjunct, and quaternary words, in the rare cases in which a special name is needed, may be termed sub-subjuncts.6

Just as we may have two (or more) coordinate primaries, e.g. in the dog and the cat ran away, we may, of course, have two or more coordinate adjuncts to the same primary: thus, in a nice young lady the words a, nice, and young equally define lady; compare also much (II) good (II) white (II) wine (I) with very (III) good (II) wine (I). Coordinate adjuncts are often joined by means of connectives, as in a rainy and stormy afternoon I a brilliant, though lengthy novel. Where there is no

I now prefer the word primary to the term principal. One might invent the terms superjunct and supernex for a primary in a junction and in a nexus respectively, and subnex for a tertiary in a nexus, but these cumbersome words are really superfluous.

|

eminar 4. Grammatical Classes of Words |

103 |

pfonnective the last adjunct often stands in a specially close connexion yith the primary as forming one idea, one compound primary (young- mJady), especially in some fixed combinations (in high good humour, by M’tfeat good fortune; extreme old age). Sometimes the first of two adImmcts tends to be subordinate to the second and thus nearly becomes a v ubjunct, as in burning hot soup, a shocking bad nurse. In this way very,

,^/hich was an adjective (as it still is in the very day) in Chaucer’s a verr ay par fit gentil knight, has become first an intermediate between an ifidjunct and a subjunct, and then a subjunct which must be classed , ;arnong adverbs. A somewhat related instance is nice (and) in nice and $warm, to which there is a curious parallel in It. bell’e: Giacosa, Foglie 136 il concerto. … Oh ci ho bell’e rinunziato / Tu Thai bell’e trovato. ‘..Other instances of adjuncts, where subjuncts might be expected, are w

Fr. Elle est toute surprise / les fenetres grandes ouvertes. I; Coordinated subjuncts are seen, e.g. in a logically and grammati-I;, cally unjustifiable construction I a seldom or never seen form. ; i In the examples hitherto chosen we have had substantives as pri-I maries, adjectives as adjuncts, and adverbs as subjuncts; and there is Certainly some degree of correspondence between the three parts of speech and the three ranks here established. We might even define substantives as words standing habitually as primaries, adjectives as ,. : words standing habitually as adjuncts, and adverbs as words stand-| ? ing habitually as subjuncts. But the correspondence is far from com-,| plete, as will be evident from the following survey: the two things, word-classes and ranks, really move in two different spheres.

Substantives

Substantives as Primaries. No further examples are needed. Substantives as Adjuncts. The old-established way of using a sub-

stantive as an adjunct is by putting it in the genitive case, e.g. Shelley’s poems / the butcher’s shop / St. Paul’s Cathedral. But it should be noted that a genitive case may also be a primary (through what is often called ellipsis), as in «I prefer Keats’s poems to Shelley’s /I bought it at the butcher’s I St. Paul’s is a fine building». In English what was the first element of a compound is now often to be considered an independent word, standing as an adjunct, thus in stone wall / a silk dress and a cotton one. Other examples of substantives as

—— .~«. ^iigiisu urammar

adjuncts are women writers / a queen bee / boy messengers, and (why not?) Captain Smith / Doctor Johnson — cf. the non-inflexion in G. Kaiser Wilhelms Erinnerungen (though with much fluctuation with compound titles).

In some cases when we want to join two substantival ideas it is found impossible or impracticable to make one of them into an adjunct of the other by simple juxtaposition; here languages often have recourse to the «definitive genitive» or a corresponding prepositional combination, as in Lat. urbs Romoe (cf. the juxtaposition in Dan. byen Rom, and on the other hand combinations like Captain Smith), Fr. la cite de Rome, E. the city of Rome, etc., and further the interesting expressions E. a devil of a fellow / that scoundrel of a servant /his ghost of a voice/G. ein alter schelm von lohnbedienter (with the exceptional use of the nominative after von) /Fr. ce fripon de valet I un amour d’enfant /celui qui avail un si drole de /It. quel ciarlatano d’un dottore/quelpover uomo di tuopadre, etc. This is connected with the Scandinavian use of a possessive pronoun ditfoe «you fool» and to the Spanish Pobrecitos de nosotros!/Desdichada de mi! […]

Substantives as Subjuncts (subnexes). The use is rare, except in word groups, where it is extremely frequent. Examples: emotions, part religious … but part human (Stevenson) / the sea went mountains high. In «Come home /I bought it cheap» home and cheap were originally substantives, but are now generally called adverbs; cf. also go South.

Adjectives

Adjectives as Primaries: you had better bow to the impossible (sg.) ye have the poor (pi.) always with you — but in savages, regulars, Christians, the moderns, etc., we have real substantives, as shown by the plural ending; so also in «the child is a dear», as shown by the article. G. beamier is generally reckoned a substantive, but is rather an adjective primary, as seen from the flexion: der beamte, ein beamier. Adjectives as Adjuncts: no examples are here necessary. Adjectives as Subjuncts. In «a fast moving engine / a long delayed punishment / a clean shaven face» and similar instances it is historically more correct to call the italicized words adverbs (in which the old adverbial ending -e has become mute in the same way as other weak -e’s) rather than adjective subjuncts. […]

|

-Seminar 4. Grammatical Classes of Words |

105 |

Pronouns

Pronouns as Primaries: / am well / this is mine I who said that? I What happened? / nobody knows, etc. (But in a mere nobody we have a real substantive, cf. the pi. nobodies.}

«Pronouns as Adjuncts: this hat / my hat / what hat? / no hat, etc.

«In some cases there is no formal distinction between pronouns in

these two employments, but in others there is, cf. mine : my I none : ‘no; thus also in G. mein hut: der meine. Note also «Hier ist ein um- ‘stand (ein ding) richtig genannt, aber nur einer (eines) «. In Fr. we ‘have formal differences in several cases: mon chapeau : le mien/ce chapeau : celui-ci I quel chapeau : lequel? I chaque : chacun I quelque : quelqu’un.

Pronouns as Subjuncts. Besides «pronominal adverbs», which need no exemplification, we have such instances as «I am that sleepy (vg.) / the more, the merrier / none too able /1 won’t stay any longer / nothing loth / somewhat paler than usual.»7

Verbs

Finite forms of verbs can only stand as secondary words (adnexes), never either as primaries or as tertiaries. But participles, like adjectives, can stand as primaries (the living are more valuable than the dead) and as adjuncts (the living dog). Infinitives, according to circumstances, may belong to each of the three ranks; in some positions they require in English to (cf. G. zu, Dan. at). I ought strictly to have entered such combinations as to go, etc., under the heading «rank of word groups».

Infinitives as Primaries: to see is to believe (cf. seeing is believing} I she wants to rest (cf. she wants some rest, with the corresponding substantive). Fr. esperer, c’esty’owzr / il est defendu defumer ici / sans courir I au lieu de courir. G. denken ist schwer / er verspricht zu kommen I ohne zu laufen I anstatt zu laufen, etc.

There are some combinations of pronominal and numeral adverbs with adjuncts that are not easily «parsed,» e.g. this once / we should have gone to Venice, or somewhere not half so nice (Masefield) / Are we going anywhere particular? They are psychologically explained from the fact that «once» = one time, «somewhere and anywhere» = (to) some, any place; the adjunct thus belongs to the implied substantive.

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

|

106 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

Infinitives as Adjuncts: in times to come there isn’t a girl to touch her / the correct thing to do/ina way not to be forgotten /the never to be forgot ten look. Fr. la chose afaire /du tabac dfamer. (In G. a special passive participle has developed from the corresponding use of the infinitive: das zu lesende buch.) […] This use of the infinitive in some way makes up for the want of a complete set of participles (future, passive, etc.).

Infinitives as Subjuncts: to see him, one would think /1 shudder to think of it / he came here to see you.

Adverbs

Adverbs as Primaries. This use is rare; as an instance may be mentioned «he did not stay for long I he’s only just back from abroad’. With pronominal adverbs it is more frequent: from here I till now. Another instance is «he left there at two o’clock»: there is taken as the object of left. Here and there may also be real substantives in philosophical parlance: «Motion requires a here and a there I in the Space-field he innumerable other theres. «

Adverbs as Adjuncts. This, too, is somewhat rare: the offside / in after years / the few nearby trees (US) / all the well passengers (US) / a so-so matron (Byron). In most instances the adjunct use of an adverb is unnecessary, as there is a corresponding adjective available. (Pronominal adverbs: the then government / the hither shore.)

Adverbs as Subjuncts. No examples needed, as this is the ordinary employment of this word-class.

When a substantive is formed from an adjective or verb, a defining word is, as it were, lifted up to a higher plane, becoming secondary instead of tertiary, and wherever possible, this is shown by the

|

Absolutely novel |

use of an adjective instead of an |

|

adverb form. |

|

Utterly dark |

absolute novelty utter darkness perfect |

|

|

Perfectly strange |

||

|

stranger accurate description my firm |

||

|

Describes accurately belief, a firm believer severe judges |

||

|

I firmly believe |

careful reader I+ 11 |

|

|

judges severely |

||

|

reads carefully + |

||

|

III |

|

4. Grammatical Classes of Words |

107 |

It is worth noting that adjectives indicating size (great, small) are Bused as shifted equivalents of adverbs of degree (much, little): a great ylmirer of Tennyson, Fr. un grand admirateur de Tennyson [ . .. ] Curme Mentions G. die geistig armen, etwas Idngst bekanntes, where geistig ind Idngst remain uninflected like adverbs «though modifying a sub stantive»: the explanation is that armen and bekanntes are not subSjstantives, but merely adjective primaries, as indicated by their flexlion. Some English words may be used in two ways: «these //

Equivalents (for)» or «fully equivalent (to)», «the direct opposites (of) » , jjor «directly opposite (to)»; Macaulay writes: «The government of Ifthe Tudors was the direct opposite to the government of Augustus»,

.tlwhere to seems to fit better with the adjective opposite than with the f; substantive, while direct presupposes the latter. In Dan. people hesi- ‘$ tate between den indbildt syge and den indbildte syge as a translation I’, of/e malade imaginaire.

Questions:

1.What principle does O. Jespersen consider to be major while differentiat ing between the three ranks of words?

2.What is meant by «junction» and «nexus»?

3.How do the traditional parts of speech and O. Jespersen’s theory of three ranks correlate? Is there any one-to-one correspondence between the tra ditional parts of speech and O. Jespersen’s three ranks? What are the advantages of the theory of three ranks?

References

Blokh M. Y. A Course in Theoretical English Grammar. — M., 2000. — P. 37-48.

. .

. — ., 1975. — . 49-67.

. . — ., 2000.

. . — .:

, 2001.- . 21-25. ., .,

.

. — ., 1981. — . 14-20, 40-46,91-99.

. . — ., 1986.

|

Hill A. |

———- • ———— .—: |

||||

|

Introduction |

to |

Linguistic Structures. |

-NY |

1958 |

|

|

Geason |

^.Linguistics |

and |

English Grammar. — |

N Y |

1961 |

lyuh B. The Structure of Modern English.-L 197l» p 27 « <« 7, Jespersen O. The Philosophy of Grammar LonHnn ~ ‘ ‘ 2‘

|

wins, 1924. — P. 96- 1. |

rdmmar— — London. G. Allen and Un— |

|

QuirkR., Greenbaum S., Leech G |

SW/wZ- / • |

|

English. — M., 1982. |

University Grammar of |

Modern English Structure. — London, 1962.

Seminar 5

NOUN AND ITS CATEGORIES

|

1. |

The general characteristics of the noun as a part of speech. Classification |

|

|

of nouns. |

||

|

2. |

The category of gender: the traditional and modern approaches to the |

|

|

category of gender. Gender in Russian and English. |

||

|

3. |

The category of number. Traditional and modern interpretations of num |

|

|

ber distinctions of the noun. Singularia Tantum and Pluralia Tantum |

||

|

nouns. |

||

|

4. |

The category of case: different approaches to its interpretation. Case dis |

|

|

•*•’.’•• |

tinctions in personal pronouns. |

|

|

5. |

The category of article determination. The status of article in the language |

|

|

hierarchy. The opposition of articles and pronominal determiners. |

||

|

6. |

The oppositional reduction of the nounal categories: neutralization and |

|

|

transposition in the categories of gender, of number, of case, and of arti |

||

|

cle determination. |

||

|

7. |

The specific status of proper names. Transposition of proper names into |

|

|

class nouns. |

1. Noun as a Part of Speech

. The noun as a part of speech has the categorial meaning of «substance».

The semantic properties of the noun determine its categorial syntactic properties: the primary substantive functions of the noun are those of the subject and the object. Its other functions are predicative, attributive and adverbial.

The syntactic properties of the noun are also revealed in its special types of combinability. In particular, the noun is characterized

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

____ ^,.6 orammar

by the prepositional combinability with another noun, a verb, an adjective, an adverb; by the casal combinability which coexists with its prepositional combinability with another noun; by the contact combinability with another noun.

As a part of speech the noun has also a set of formal features. Thus, it is characterized by specific word-building patterns having typical suffixes, compound stem models, conversion patterns.

The noun discriminates four grammatical categories: the categories of gender, number, case, and article determination.

2. Category of Gender

The problem of gender in English is being vigorously disputed. Linguistic scholars as a rule deny the existence of gender in English as a grammatical category and stress its purely semantic character. The actual gender distinctions of nouns are not denied by anyone; what is disputable is the character of the gender classification: whether it is purely semantic or semantico-grammatical.

In fact, the category of gender in English is expressed with the help of the obligatory correlation of nouns with the personal pronouns of the third person. The third person pronouns being specific and obligatory classifiers of nouns, English gender distinctions display their grammatical nature.

The category of gender is based on two hierarchically arranged oppositions: the upper opposition is general, it functions in the whole set of nouns; the lower opposition is partial, it functions in the subset of person nouns only. As a result of the double oppositional correlation, in Modern English a specific system of three genders arises: the neuter, the masculine, and the feminine genders.

In English there are many person nouns capable of expressing both feminine and masculine genders by way of the pronominal correlation. These nouns comprise a group of the so-called «common gender» nouns, e.g.: «person», «friend», etc.

In the plural all the gender distinctions are neutralized but they are rendered obliquely through the correlation with the singular.

Alongside of the grammatical (or lexico-grammatical) gender distinctions, English nouns can show the sex of their referents also lexically with the help of special lexical markers, e.g.: bull-calf I cow-calf,

i,.sparrow I hen-sparrow, he-bear I she-bear, etc. or through suffixderivation: sultan I sultana, lion I lioness, etc. The category of gender can undergo the process of oppositional tion. It can be easily neutralized (with the group of «common nouns) and transponized (the process of «personification»). The English gender differs much from the

Russian gender: the Eng-fflish gender has a semantic character (oppositionally, i.e. grammatically ressed), while the gender in Russian

is partially semantic (Russian ate nouns have semantic gender distinctions), and partially formal.

3. Category of Number

The category of number is expressed by the opposition of the plural form of the noun to its singular form. The semantic difference of the Acjpositional members of the category of number in many linguistic works $ is treated traditionally: the meaning of the singular is interpreted as «one» * and the meaning of the plural — as «many» («more than one»). , As the traditional interpretation of the singular and the plural members does not work in many cases, recently the categorial meaning of the plural has been reconsidered and now it is interpreted as the denotation ®f «the potentially dismembering reflection of the structure of the referent» (correspondingly, the categorial meaning of the singular is treated as «the non-dismembering reflection of the structure of the referent»).

The categorial opposition of number is subjected to the process of oopositional reduction. Neutralization takes place when countable aouns begin to function as Singularia Tantum nouns, denoting in such cases either abstract ideas or some mass material, e.g. On my birthday we always have goose: or when countable nouns are used in the func- tion of the Absolute Plural: The board are not unanimous on The ques- tion. A stylistically marked transposition is achieved by the use of the descriptive uncountable plural (The fruits of the toil are not always visible) and the «repetition plural» (Car after car rushed past me).

4. Category of Case

The case meanings in English relate to one another in a peculiar, unknown in other languages, way: the common case is quite indifferent from the semantic point of view, while the genitive case functions as i subsidiary element in the morphological system of English be-

112

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar

cause its semantics is also rendered by the Common Case noun in prepositional collocations and in contact.

In the discussion of the case problem four main views advanced by different scholars should be considered: the «theory of positional cases», the «theory of prepositional cases», the «limited case theory», and the «postpositional theory».

According to the «theory of positional cases», the English noun distinguishes the inflectional genitive case and four non-inflectional, purely positional, cases — Nominative, Vocative, Dative, Accusative. The cardinal weak point of this theory lies in the fact that it mixes up the functional (syntactic) characteristics of the sentence parts and the morphological features of the noun.

The «theory of prepositional cases» regards nounal combinations with the prepositions in certain object and attributive collocations as morphological case forms: the Dative Case (to + N, for + N), the Genitive Case (of + N).

The «limited case theory» recognizes the existence in English of a limited case system whose members are the Genitive Case (a strong form) and the Common Case (a weak form).

The «postpositional theory» claims that the English noun in the course of its historical development has completely lost the morphological category of case; that is why the traditional Genitive Case is treated by its advocates as a combination of a noun with a particle.

Taking into account the advantages of the two theories — the «limited case theory» and the «postpositional theory» opens new perspectives in the treatment of the category of case. It stands to reason to regard the element -s I -es as a special case particle. Thus, according to the «particle case theory» the two-case system of the noun is to be recognized in English: the Common Case is a direct case, the Genitive Case is an oblique case. As the case opposition does not work with all nouns, from the functional point of view the Genitive Case is to be regarded as subsidiary to the syntactic system of prepositional phrases.

5. Category of Article Determination

The problem of English articles has been the subject of hot discussions for many years. Today the most disputable questions concerning the system of articles in English are the following: the identi-

|

linar 5. Noun and Its Categories |

113 |

tion of the article status in the hierarchy of language units, the Dumber of articles, their categorial and pragmatic functions.

There exist two basic approaches to the problem of the article fctatus: some scholars consider the article a self-sufficient word which lorms with the modified noun a syntactic syntagma; others identify the article with the morpheme-like element which builds up with the rnpunal stem a specific morph.

In recent works on the problem of article determination of Eng-| lish nouns, more often than not an opinion is expressed that in the ‘(»hierarchy of language units the article occupies a peculiar place — the place intermediary between the word and the morpheme.

In the light of the oppositional theory the category of article determination of the noun is regarded as one which is based on two binary oppositions: one of them is upper, the other is lower. The opposition of the higher level operates in the whole system of articles and contrasts the definite article with the noun against the two other forms of article determination of the noun — the indefinite article and

. the meaningful absence of the article. The opposition of the lower level operates within the sphere of realizing the categorial meaning of non-identification (the sphere of the weak member of the upper opposition) and contrasts the two types of generalization — the relative generalization and the absolute generalization. As a result, the system of articles in English is described as one consisting of three articles — the definite article, the indefinite article, and the zero article, which, correspondingly, express the categorial functions (meanings) Of identification, relative generalization, and absolute generalization. The article paradigm is generalized for the whole system of the common nouns in English and is transpositionally outstretched into the subsystems of proper nouns and Unica (unique nouns) as well as

.into the system of pronouns.

Questions:

1. What are the «part of speech» properties of a noun? • 2. What does the peculiarity of expressing gender distinctions in English

consist in?

‘3. What differentiates the category of gender in English from that in Russian? 8 — 3548

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

|

4. Why don’t lexical gender markers annul the grammatical character of |

ariar 5. Noun and Its Categories |

115 |

|

|

English gender? |

»Isn’t Ida’s head a dead ringer for the |

||

|

5. Why is the interpretation of the categorial meaning of the nounal plural |

|||

|

lady’s head on the silver dollar?» (O.Henry) |

|||

|

form as «more than one» considered not well grounded? |

He had been away from New York for more than eight months and |

||

|

6. What is the modern interpretation of the categorial semantics of the plu |

|||

|

most of the dance music was unfamiliar to him, but at the first bars of |

|||

|

ral form of the noun? |

|||

|

|he «Painted Doll», to which he and Caroline had moved through so |

|||

|

‘ 7. What makes the category of case in English disputable? > 8. What are |

|||

|

much happiness and despair the previous summer, he crossed to Caro- |

|||

|

the strong and weak points of the «prepositional», «positional», and |

|||

|

line’s table and asked her to dance (Fitzgerald). |

|||

|

«postpositional» case theories? 9. What ensures a peculiar status of «-s»? |

|||

|

10. What are the main approaches to the treatment of the article? |

b) |

||

|

’11. What shows the intermediate (between the word and the morpheme) sta- |

|||

|

And then followed the big city’s biggest shame, its most ancient and |

|||

|

tus of the article? |

|||

|

12. What does the oppositional representation of the articles reveal? • |

rotten surviving canker… handed down from a long-ago century of the |

||

|

‘basest barbarity- the Hue and Cry (O.Henry). He mentioned what he |

|||

|

13. What are the categorial meanings of the three articles? |

|||

|

had said to the aspiring young actress who had stopped him in front |

|||

|

I. Account for the article determination of the given casal phrases: |

ofSardi’s and asked quite bluntly if she should persist in her ambition to |

||

|

go on the stage or give up and go home (Saroyan). The policeman’s mind |

|||

|

a) a soldier’s bag, a ten miles’ forest, the Prime Minister’s speech; |

|||

|

refused to accept Soapy even as a clue. Men who smash windows do |

|||

|

b) Travolta’s first role, expensive teenagers’ T-shirts, the man who was |

not remain to parley with the law’s minions (O.Henry). |

||

|

run over yesterday’s daughter; |

I’ve heard you’re very fat these days, but I know it’s nothing serious, |

||

|

c) week’s work, a new men’s deodorant, a hundred miles’ run; |

|||

|

and anyhow I don’t care what happens to people’s bodies, just so the |

|||

|

d) within a stone’s throw, a child’s dream, Christ’s Church. |

rest of them is O.K. (Saroyan). |

||

|

«I dropped them flowers in a cracker-barrel, and let the news trickle in |

|||

|

11. Define the casal semantics of the modifying component in the underlined |

my ears and down toward my upper left-hand shirt pocket until it got |

||

|

phrases and account for their determination: |

to my feet.» (O.Henry) |

||

|

5. |

She turned and smiled at him unhappily in the dim dashboard light |

||

|

a) |

(Cheever). |

||

|

1. Two Negroes, dressed in glittering livery such as one sees in pictures of |

c) |

||

|

royal processions in London, were standing at attention beside the car |

|||

|

and as the two young men dismounted from the buggy they were greeted |

Andy agreed with me, but after we talked the scheme over with the |

||

|

in some language which the guest could not understand, but which seemed |

hotel clerk we gave that plan up. He told us that there was only one way |

||

|

to be an extreme form of the Southern Negro’s dialect (Fitzgerald). |

to get an appointment in Washington, and that was through a lady |

||

|

2. Home was a fine high-ceiling apartment hewn from the palace of a Re |

lobbyist (O.Henry). |

||

|

naissance cardinal in the Rue Monsieur — the sort of thing Henry could |

Nobody lived in the old Parker mansion, and the driveway was used as |

||

|

not have afforded in America (Fitzgerald). |

a lovers’ lane (Cheever). |

||

|

3. Wherefore it is better to be a guest of the law, which, though conducted |

His eyes were the same blue shade as the china dog’s in the right-hand |

||

|

by rules, does not meddle unduly with a gentleman’s private affairs |

corner of your Aunt Ellen’s mantelpiece (O.Henry). |

||

|

(O.Henry). |

Pandemonium broke loose in the courtroom. A woman’s scream rose |

||

|

4. The two vivid years of his love for Caroline moved back around him |

above the bedlam and suddenly a lovely, dark-haired girl was in Walter |

||

|

like years in Einstein’s physics (Fitzgerald). |

Mitty’s arms (Thurber). |

||

|

«A man?» said Sue, with a jew’s-harp twang in her voice (O.Henry). |

6.Then he would spring onto the terrace, lift the steak lightly off the fire, and run away with the Goslins’ dinner. Jupiter’s days were numbered. The Wrightsons’ German gardener or the Farquarsons’ cook would

d)

1.He was past sixty and had a Michael Angelo’s Moses beard curling down from the head of a satyr along the body of an imp (O.Henry).

2.One day this man finds his wife putting on her overshoes and three months’ supply of bird seed into the canary’s cage (O.Henry).

1.After leaving Pinky, Francis went to a jeweller’s and bought the girl a bracelet (Cheever).

1.And Mr. Binkley looked imposing and dashing with his red face and grey moustache, and his tight dress coat, that made the back of his neck roll up just like a successful novelist’s (Cheever).

1.He broke up garden parties and tennis matches, and got mixed up in the processional at Christ’s Church on Sunday, barking at the men in red dresses (Cheever).

1.I painted the portrait of a very beautiful and popular society dame (O.Henry).

III.Open the brackets and account for the choice of the casaJ form of the noun:

a)

1.Vivian Schnlitzer-Murphy had rubies as big as (hen + eggs), and sap phires that were like globes with lights inside them (Fitzgerald).

1.But as Soapy set foot inside the (restaurant + door) the (head + waiter + eye) fell upon his frayed trousers and decadent shoes (O.Henry).

1.A miserable cat wanders into the garden, sunk in spiritual and physical discomfort. Tied to its head is a small (straw + hat) — a (doll + hat) — and it is securely buttoned into a (doll + dress), from the skirts of which protrudes its long, hairy tail (Cheever).

1.Soapy straightened the (lady + missionary + ready-made + tie), dragged his shrinking cuffs into the open, set his hat at a killing cant and sidled towards the young woman (O.Henry).

1.«I’m afraid I won’t be able to,» he said, after a (moment + hesitation) (Fitzgerald).

b)

1.Of women there were five in Yellowhammer. The (assayer + wife), the (proprietress + the Lucky Strike Hotel), and a laundress whose washtub panned out an (ounce + dust) a day (O.Henry).

2.- «The face,» said Reineman, «is the (face + one + God + own angels).» (O.Henry)

3.people who had come in were rich and at home in their richness with one another — a dark lovely girl with a hysterical little laugh he had met before; two confident men whose jokes referred invariably to last (night + scandal) and (tonight + potentialities)… (Fitzgerald).

4.His face was a sickly white, covered almost to the eyes with a stubble the (shade + a red Irish setter + coat) (O.Henry).

5.During the first intermission he suddenly remembered that he had not had a seat removed from the theatre and placed in his dressing room, so he called the (stage + manager) and told him to see that such a seat was instantly found somewhere and placed in his dress ing room (Saroyan).

c)

1.His eyes were full of hopeless, tricky defiance like that seen in a (cur) that is cornered by his tormentors (O.Henry).

2.The scene for his miserere mei Deus was, like (the waiting room + so many doctors + offices), a crude (token + gesture) toward the sweets of domestic bliss: a place arranged with antiques, (coffee + tables), potted plants, and (etchings + snow-covered bridges and geese in fight), al though there were no children, no (marriage + bed), no stove, even, in this (travesty + a house), where no one had ever spent the night and where the curtained windows looked straight onto a dark (air + shaft) (Cheever).

1.Their eyes brushed past (each other), and the look he knew so well was staring out at him from hers (Fitzgerald).

2.«Hello, Mitty,» he said. «We’re having the (devil + own time) with McMillan, the millionaire banker and close personal friend of Roosevelt.» (Thurber)

1.«You know? Clayton, that (boy + hers), doesn’t seem to get a job…» (Cheever)

d)

1.He noticed that the (face + the + taxi + driver) in the photograph inside the cab resembled, in many ways, the (painter + face) (Saroyan).

2.Here he was, proudly resigned to the loneliness which is (man + lot), ready and able to write, and to say yes, with no strings attached (Saroyan).

3.He was tired from the (day + work) and tired with longing, and sitting on the (edge + the bed) had the effect of deepening his weariness (Cheever).

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

Соседние файлы в папке Теорграмматика

- #

18.03.201516.06 Mб72haymovich(2).pdf

- #

- #

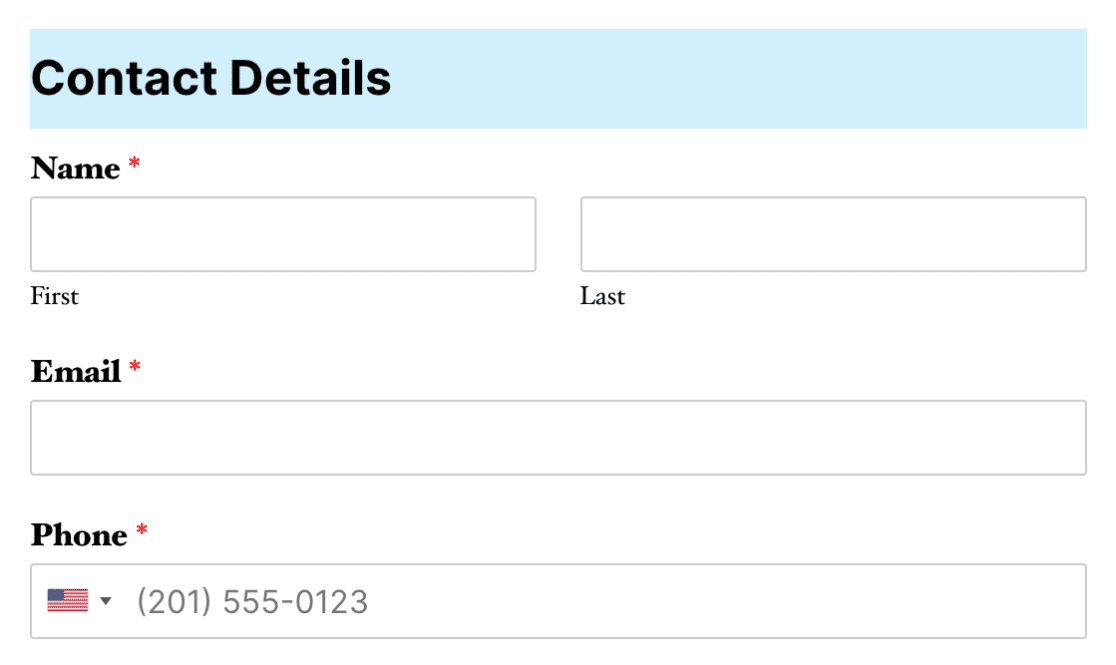

- #

Would you like to customize the appearance of your WordPress forms? In WPForms, you can easily add custom CSS classes and styles to make your forms look how you’d like.

In this tutorial, we’ll show you how to add custom CSS classes to style specific form elements, as well as how to add any custom CSS to your WordPress site.

- What’s a CSS Class?

- Adding Custom CSS Classes in WPForms

- Adding CSS Classes to Individual Form Fields

- Adding CSS Classes to a Form Container or Submit Button

- Creating and Adding CSS Styles for Your Site

- Creating CSS Styles

- Adding CSS to Your WordPress Site

What’s a CSS Class?

CSS classes are a way of targeting the elements that you’d like to style on your website.

In WPForms, fields are automatically assigned several CSS classes. For instance, if a field is set to a Field Size of Large, it will be assigned the CSS class wpforms-field-large.

By adding a custom CSS class, you can easily target a specific form field or apply the same styles to multiple fields.

Note: If you’d like to style your forms but skip using custom CSS classes or writing any code, consider checking out our form styling tutorial.

Adding Custom CSS Classes in WPForms

In WPForms, you can add your own custom CSS classes to individual form fields, the submit button or the container around your form.

Adding CSS Classes to Individual Form Fields

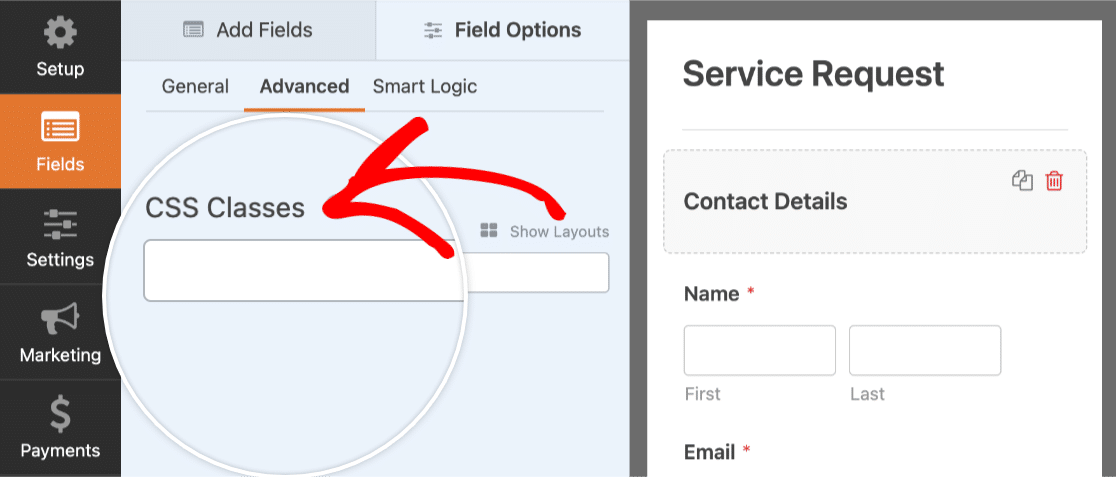

To add a custom CSS class to a form field, you’ll need to create a new form or edit an existing form.

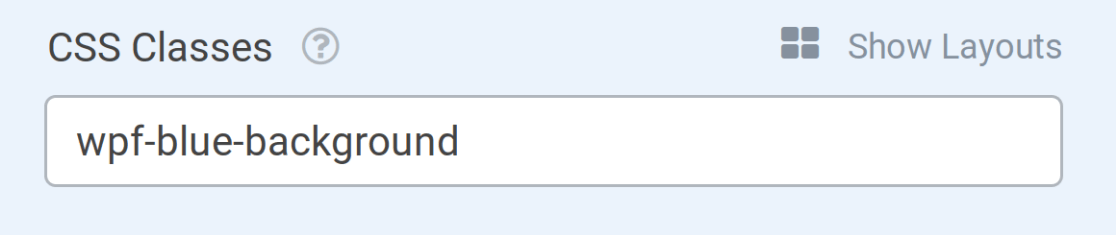

Within the form builder’s preview panel, click on the field to open its Field Options. Then, open the Advanced tab and look for the field labeled CSS Classes.

When naming a CSS class, you may use only letters or numbers, and no spaces are allowed. Class names are case-sensitive, so it is recommended that you use lowercase letters. If you’d like the class name to contain more than one word, include a hyphen (-) or underscore (_) instead of a space.

To avoid running into any issues, always start your class names with a letter.

For this example, we’ll name our CSS class wpf-blue-background.

By adding wpf- to the beginning of our classes, we’re less likely to add a class name already being used by our site’s theme. This will help to avoid style conflicts and make it more likely for our styles to be applied successfully.

When you’re ready, add the wpf-blue-background CSS class to the CSS Classes field.

If you’d like, you can also add additional classes to this field. To do that, simply add a space between each class name. For example:

wpf-blue-background wpf-bold-font wpf-xl-margin

Adding CSS Classes to a Form Container or Submit Button

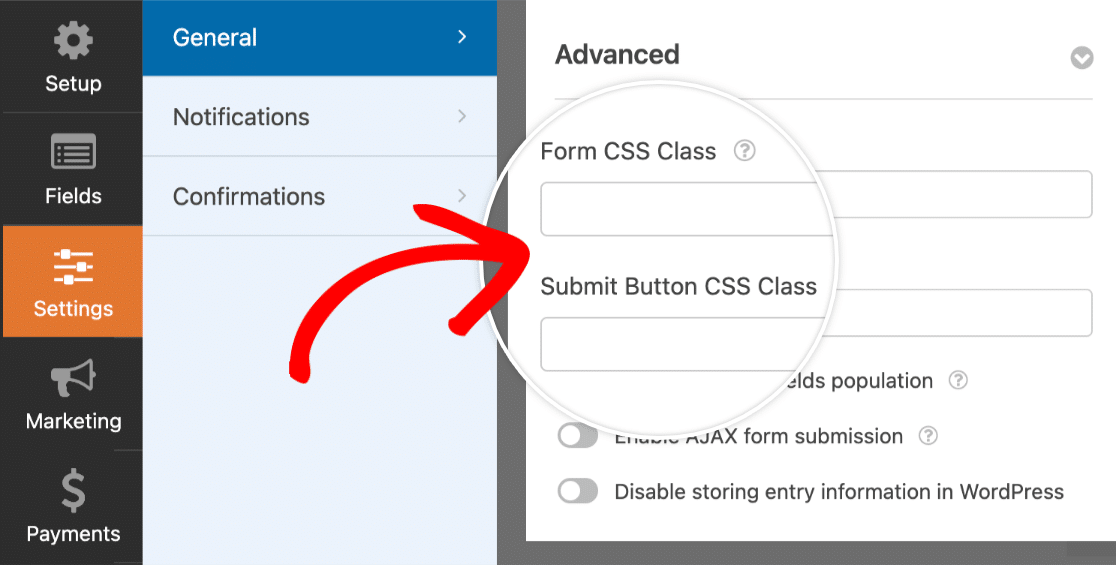

For some styles, it may be useful to target the form’s container or its submit button.

For example, you may want the submit buttons for all signup forms on your site to be styled one way, and for the submit buttons in any general contact forms to be styled a different way. An easy way to accomplish this is by adding the same CSS class to any submit buttons that you’d like to be styled the same way.

To add a custom CSS class name for either option, open the form builder and go to Settings » General. From here, go to the Advanced section and you’ll be able to see fields for Form CSS Class and Submit Button CSS Class.

If you’d like to add more than one class name, just separate each with a space.

Creating and Adding CSS Styles for Your Site

Now that you’ve added a custom CSS class to a field in your form, you can create the styles you’d like applied.

Creating CSS Styles

CSS is a powerful tool with an extensive amount of styling options available. For instructions on how to get started with creating CSS, please see our Beginner’s CSS Guide.

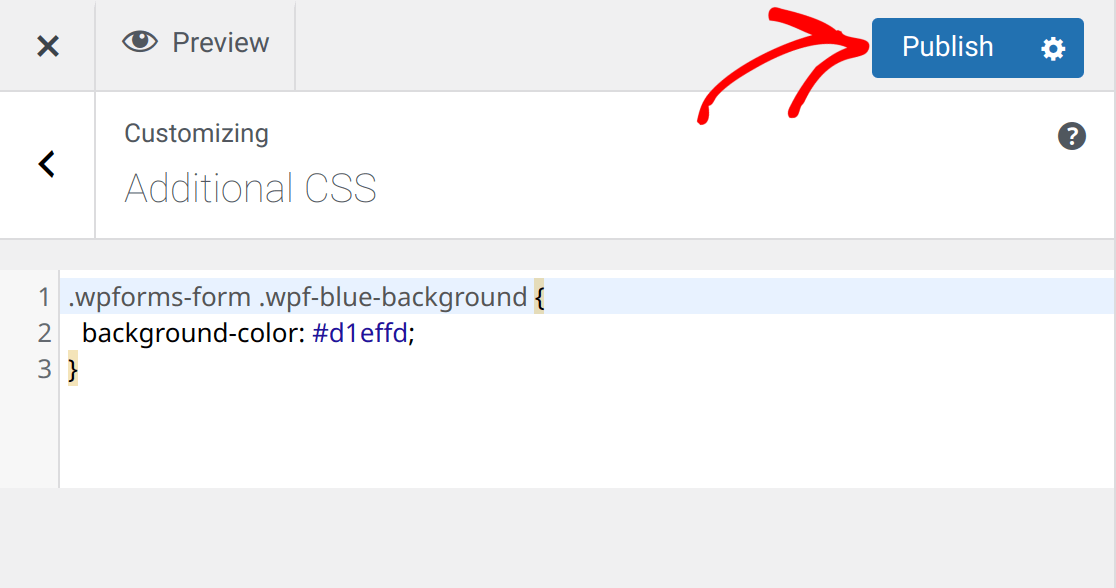

For our example, we’ll simply add a blue background to any field with the class wpf-blue-background. When targeting a class name within CSS, it must always begin with a period (.), for example .wpf-blue-background.

Since many styles are already being applied to your form, it’s also a good idea to make your CSS more specific. To do that, simply add .wpforms-form in front of your custom class name.

Here’s our example CSS:

.wpforms-form .wpf-blue-background {

background-color: #d1effd;

}

If your custom styles are not being applied successfully, you can include !important before the semicolon.

Note: Using !important is only necessary if your styles are not being applied otherwise. Our guide on troubleshooting CSS contains more details.

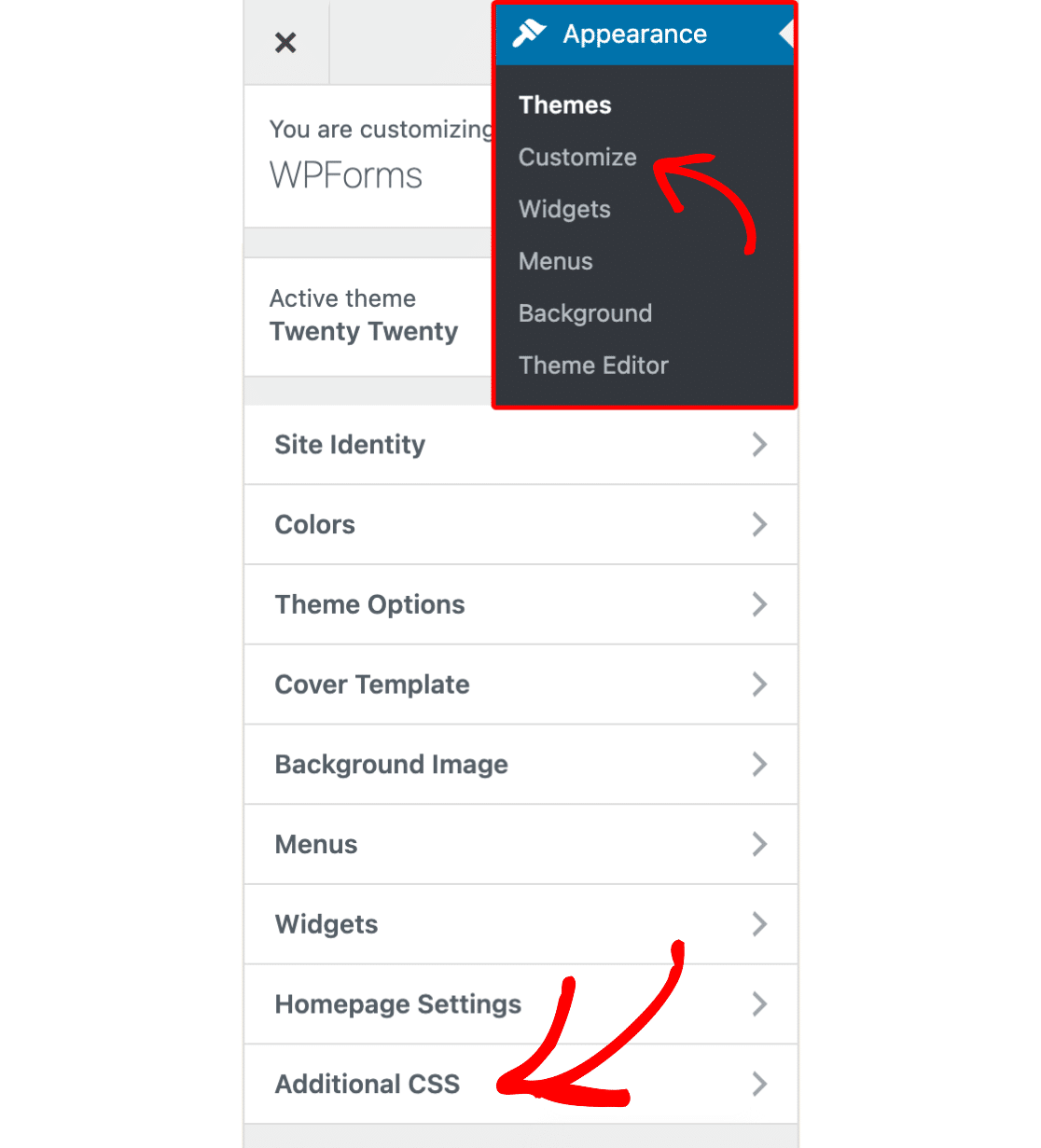

Adding CSS to Your WordPress Site

One quick and easy way to add custom CSS to your site is with the WordPress Theme Customizer. This is a popular option because it’s available in almost all themes and has a live preview area.

If you’d like to see additional methods, please see WPBeginner’s tutorial on how to add custom CSS to WordPress.

To access the CSS area of the Theme Customizer, go to Appearance » Customize and then select the tab labeled Additional CSS.

Next, go ahead and add your custom CSS snippet. When you’re ready, click Publish.

Here’s how our example form looks now with the CSS class and CSS styles applied:

Note: Are your custom styles not displaying? Please check out our guide to troubleshooting CSS for the most common issues and solutions.

That’s it! You can now add custom CSS classes to style specific areas of your forms.

Would you also like to view and modify our built-in form styles? Check out our tutorial on customizing individual form fields for all the details.

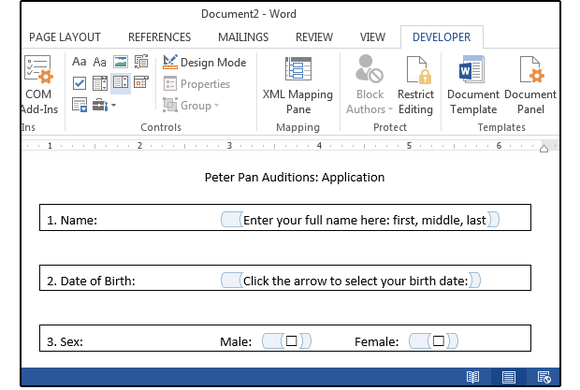

Custom interactive forms are one of Word’s most sophisticated tricks. More than a simple design tool, the form tools let you collect specific information and export to Excel, Access, or XML.

Start in the Developer tab

You create custom forms in the Developer tab. If the Developer tab is not currently visible on your Ribbon menu, select File > Options > Customize Ribbon. Click the Developer checkbox in the Main Tabs panel, and click OK.

When the main document screen reappears, click the Developer tab. Notice the icon buttons on the left side of the Controls group. These are the main controls used for interactive forms. The icon buttons on the right side of the Controls group are used to define the properties and format the attributes for each Content Control button. Each Control is defined below:

Rich Text Content Control: contains a block of text (including attributes) plus additional content types such as tables, images, or other content controls.

Plain Text Content Control: contains just plain text—that is, no other content controls, images, or tables. Attributes are included, but only one attribute is applied to the entire text control; e.g., if you underline one word, all the text is underlined.

Picture Content Control: This one, obviously, contains images.

Building Block Gallery Control: Use this control to insert blocks of data into documents such as custom text, custom tables, custom equations, custom quick parts, etc. These blocks are generally defined in advance and saved in the Building Block Gallery (which is part of the Quick Parts Gallery).

Check Box: Use this to solicit a yes/no type of response (selected is generally yes, and not -elected is no).

Combo Box: Use this control to provide users with a list of selectable items plus an option to add/enter their own responses, which are not included in the list.

Drop Down List: a pre-programmed group of items, which users can select from a list.

Date Picker: Use this to select a date from a pop-up calendar.

Repeating Section Content Control: Use this control to enter repetitive content (e.g., to repeat parts of a table, text, etc.) including other content controls.

Legacy Tools: Theseform field types were available in previous versions of Word; that is, Word 97 through 2003. You can still use them in Word 2013, but these forms must be saved in one of the previous legacy formats (i.e., Word 1997 or Word 2003).

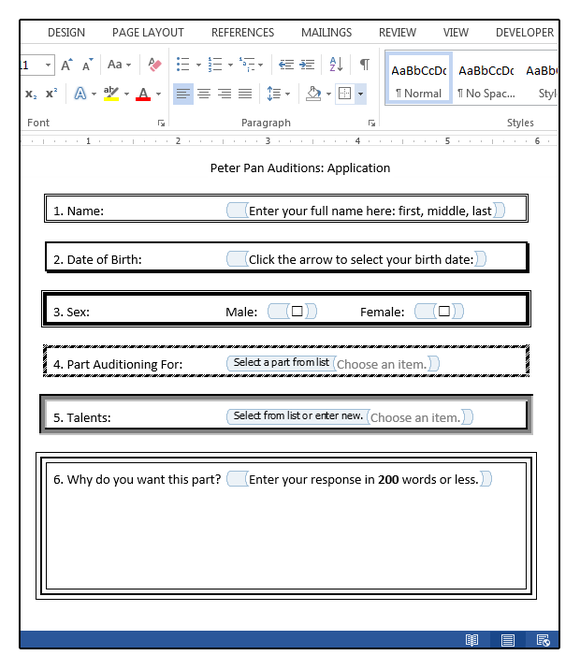

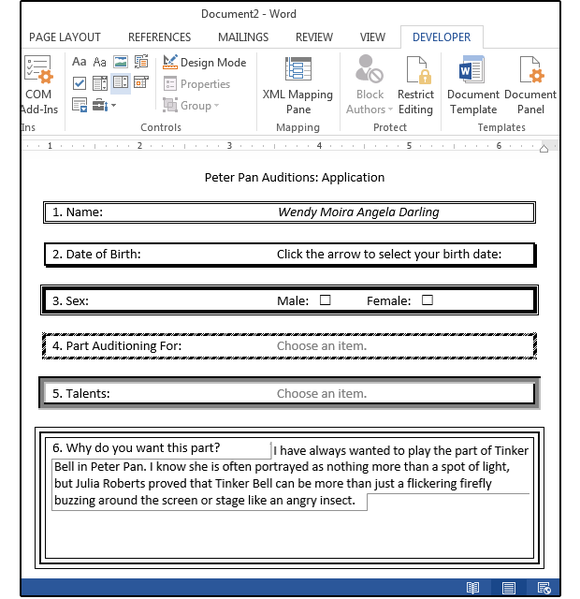

Create a form

We’ll create a simple application, with questions that must be filled out or selected from a list of options.

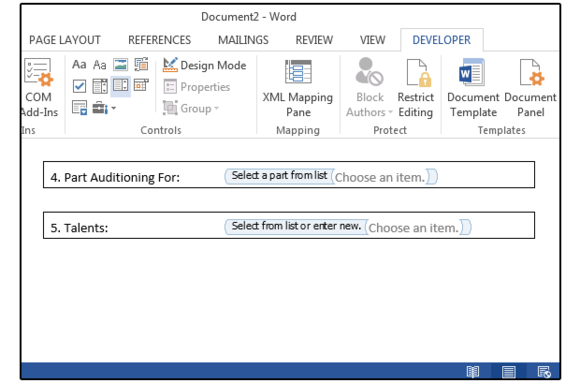

First, select the application type you want to create, then decide which questions (or fields) you want to ask your audience. For this exercise, let’s try an application for auditions for the play Peter Pan. Use the following fields/questions.

- Name (Plain Text)

- Date of Birth (Date Picker)

- Sex (Check Box)

- Part Auditioning For (Drop Down List)

- Talents (Combo Box)

- Why do you want this part? (Rich Text)

Enter or copy and paste the six fields above to a new, blank document, then click Developer > Controls > Design Mode to see the options you select as you build the form.

1. Position the cursor beside the first field: “Name.” Press the tab key a few times to move the cursor a few columns to the right. Click the Plain Text Content Control button. Enter your custom text (e.g., “Enter your full name here: first, middle, last.”) over the existing text.

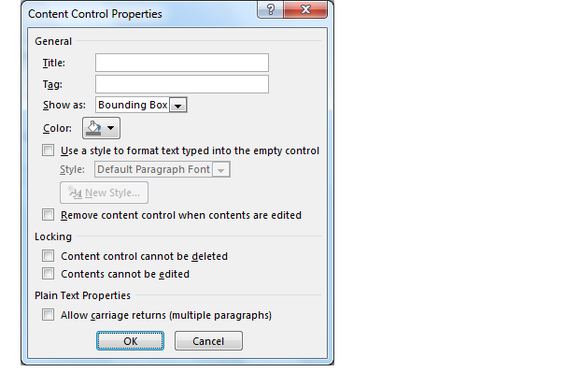

Next, click the Properties button to add a title and/or tag; change the border, color, or style; and set or define several content control properties related to the Name field.

Note: Except for the attributes, most designers skip this section.

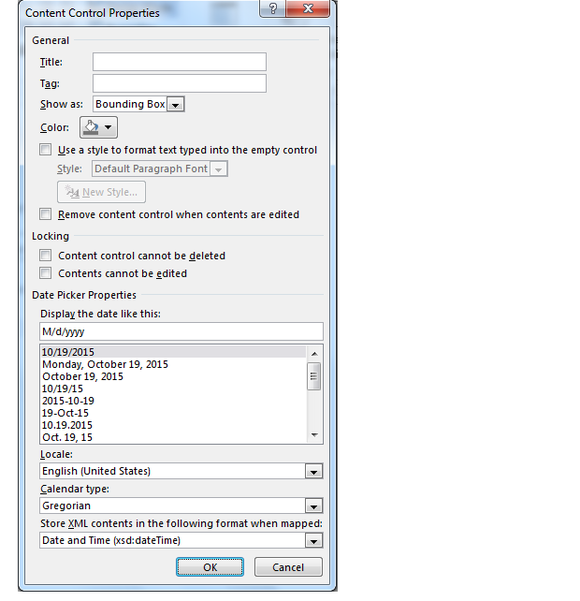

2. Move to the second field: “Date of Birth.” Press a few tabs to align with the field above, then select the Date Picker button. Again, enter your custom text over the existing text (such as, “Click the arrow to select your birthdate”). Click the Properties button to add a title or tag; change the border, color, or style; set the date format, and define several content control properties related to this field.

3. For the third field, Sex; type Male, then select the Check Box button. Press the spacebar a couple of times, then type Female and click the Check Box button again. Click the Properties button to add a title and/or tag. Change the border, color, or style; set the check box format; and define several content control properties related to this field.

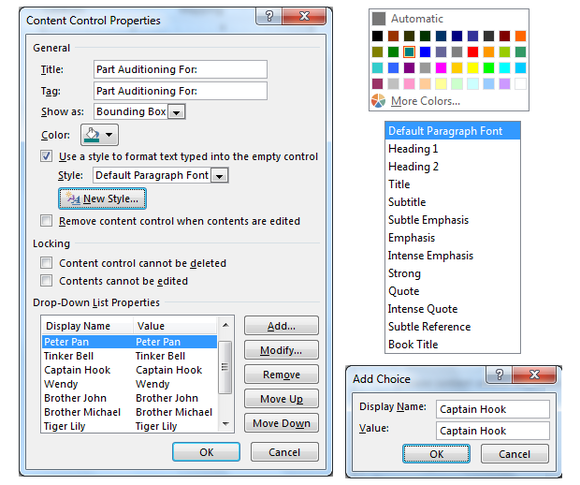

4. Move to the fourth field: “Part Auditioning For.” Press a few tabs to align with the field above, then select the Drop Down List button. Enter your custom text over the existing text, then click the Properties button to add or change the properties like before.

For these types of fields, you must enter some responses for the users to select from a list. At the bottom of this window, under Drop Down List Properties, click the Add button to add selections to the list. Use the remaining buttons to modify, remove, or move items up and down.

5. Move to the fifth field: Talents. Press a few tabs to align with the field above, then select the Combo Box button. The Combo Box functions exactly like a List Box except, in addition to a list of items, users can add their own custom items. The Properties dialog is exactly the same as the Drop Down List dialog, with Add, Modify, and Remove buttons.

Note: The maximum number of items allowed in a single Drop Down or Combo list is 25.

6. Position the cursor beside the last field: “Why do you want this part?” Press the tab key a few times to move the cursor a few columns to the right. Click the Rich Text Content Control button. Enter your custom text, then click the Properties button to change or add information to the Content Control Properties fields.

Once the form is complete, consider adding some creative formatting such as artistic borders, shading, and unique fonts. Our example shows six different borders to illustrate the various options that are available, but obviously you’d select just one or two styles for an actual form.

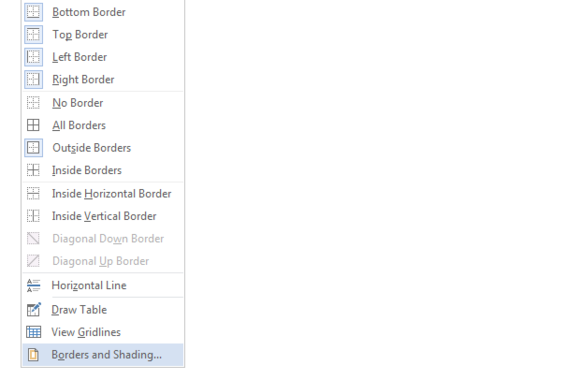

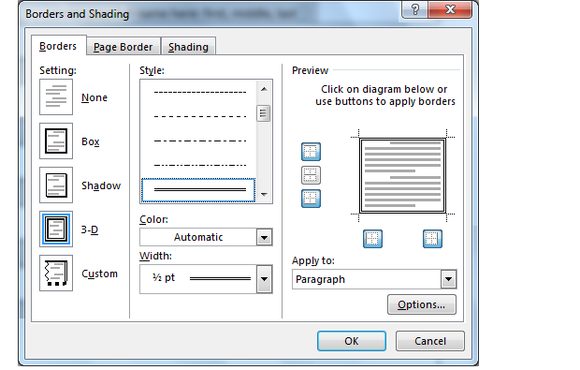

Add borders, colors and more

Highlight each field separately to add a border and/or shading around each application question. To add a single border around the entire form, press Ctrl+A to select all the text.

1. Once the target area is highlighted, select the Home > Paragraph > Borders > Borders and Shading.

2. From the Borders and Shading dialog box, click the Borders tab, then select border settings from the options in this dialog box.

3. Notice the options on the right side of this dialog box under Preview. Use these icons to add or remove the selected border from the top, bottom, left, right, or center of the target area.

D. When finished, click OK. Test your custom form: Answer the questions, fill in the blanks, select items from the list, and click the check boxes to ensure that everything is working properly. Once you’re satisfied with the form, save it, and then distribute it to the applicants.

This article is written for users of the following Microsoft Word versions: 2007, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2019, and Word in Microsoft 365. If you are using an earlier version (Word 2003 or earlier), this tip may not work for you. For a version of this tip written specifically for earlier versions of Word, click here: Working with Form Fields.

Written by Allen Wyatt (last updated March 23, 2019)

This tip applies to Word 2007, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2019, and Word in Microsoft 365

The fields available for use in forms are accessible through the Developer tab of the ribbon. If you don’t see the Developer tab (it isn’t visible on your system), you need to instruct Word to display it.

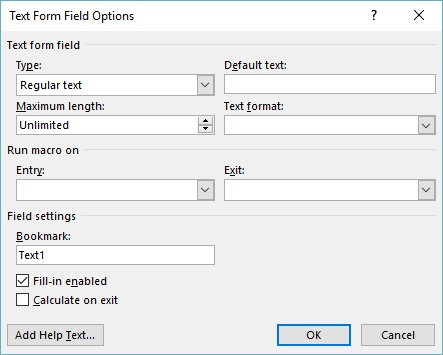

If you display the Developer tab and take a look at the Controls group, you’ll notice that there are a bunch of controls available. None of these controls are form fields. Instead, you need to click the Legacy Tools icon, which displays a whole group of controls that originate with older versions of Word. The Legacy Forms group (visible after you click the Legacy Tools icon) includes three types of form fields you can insert in a document: text, check box, and pull-down. Each of these form fields allows the user of the form to select or enter information of the type that you deem appropriate.

As an example, let’s say you are creating an order form and you need a field where a user can enter the name of the person making the order. Further, you want to allow only up to 25 characters to be entered in the field. To accomplish this, follow these steps:

- Position the insertion point where you want the field to appear.

- Display the Developer tab of the ribbon.

- In the Controls group click Legacy Tools and then click the Text Form Field tool. A field indicator appears in the document.

- Right-click the form field just entered and choose Properties from the resulting Context menu. The Text Form Field Options dialog box appears. (See Figure 1.)

- Make sure the Type pull-down list is set to Regular Text. (This is the type of information you want to allow in the field.)