Morphology is the study of words and their parts. Morphemes, like prefixes, suffixes and base words, are defined as the smallest meaningful units of meaning. Morphemes are important for phonics in both reading and spelling, as well as in vocabulary and comprehension.

Why use morphology

Teaching morphemes unlocks the structures and meanings within words. It is very useful to have a strong awareness of prefixes, suffixes and base words. These are often spelt the same across different words, even when the sound changes, and often have a consistent purpose and/or meaning.

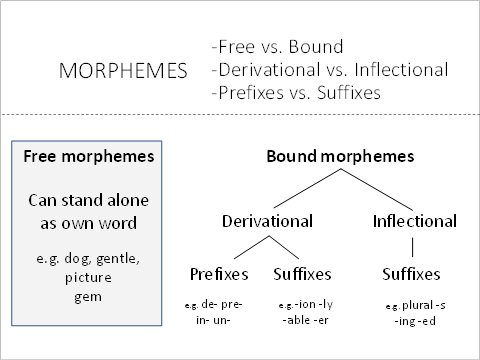

Types of morphemes

Free vs. bound

Morphemes can be either single words (free morphemes) or parts of words (bound morphemes).

A free morpheme can stand alone as its own word

- gentle

- father

- licence

- picture

- gem

A bound morpheme only occurs as part of a word

- -s as in cat+s

- -ed as in crumb+ed

- un- as in un+happy

- mis- as in mis-fortune

- -er as in teach+er

In the example above: un+system+atic+al+ly, there is a root word (system) and bound morphemes that attach to the root (un-, -atic, -al, -ly)

system = root un-, -atic, -al, -ly = bound morphemes

If two free morphemes are joined together they create a compound word. These words are a great way to introduce morphology (the study of word parts) into the classroom.

For more details, see:

Compound words

Inflectional vs. derivational

Morphemes can also be divided into inflectional or derivational morphemes.

Inflectional morphemes change what a word does in terms of grammar, but does not create a new word.

For example, the word <skip> has many forms: skip (base form), skipping (present progressive), skipped (past tense).

The inflectional morphemes -ing and -ed are added to the base word skip, to indicate the tense of the word.

If a word has an inflectional morpheme, it is still the same word, with a few suffixes added. So if you looked up <skip> in the dictionary, then only the base word <skip> would get its own entry into the dictionary. Skipping and skipped are listed under skip, as they are inflections of the base word. Skipping and skipped do not get their own dictionary entry.

Skip

verb, skipped, skipping.

- to move in a light, springy manner by bounding forward with alternate hops on each foot. to pass from one point, thing, subject, etc.,

- to another, disregarding or omitting what intervenes: He skipped through the book quickly.

- to go away hastily and secretly; flee without notice.

From

Dictionary.com — skip

Another example is <run>: run (base form), running (present progressive), ran (past tense). In this example the past tense marker changes the vowel of the word: run (rhymes with fun), to ran (rhymes with can). However, the inflectional morphemes -ing and past tense morpheme are added to the base word <run>, and are listed in the same dictionary entry.

Run

verb, ran, run, running.

- to go quickly by moving the legs more rapidly than at a walk and in such a manner that for an instant in each step all or both feet are off the ground.

- to move with haste; act quickly: Run upstairs and get the iodine.

- to depart quickly; take to flight; flee or escape: to run from danger.

From

Dictionary.com — run

Derivational morphemes are different to inflectional morphemes, as they do derive/create a new word, which gets its own entry in the dictionary. Derivational morphemes help us to create new words out of base words.

For example, we can create new words from <act> by adding derivational prefixes (e.g. re- en-) and suffixes (e.g. -or).

Thus out of <act> we can get re+act = react en+act = enact act+or = actor.

Whenever a derivational morpheme is added, a new word (and dictionary entry) is derived/created.

For the <act> example, the following dictionary entries can be found:

Act

noun

- anything done, being done, or to be done; deed; performance: a heroic act.

- the process of doing: caught in the act.

- a formal decision, law, or the like, by a legislature, ruler, court, or other authority; decree or edict; statute; judgement, resolve, or award: an act of Parliament.

From

Dictionary.com — act

React

verb

- to act in response to an agent or influence: How did the audience react to the speech?

- to act reciprocally upon each other, as two things.

- to act in a reverse direction or manner, especially so as to return to a prior condition.

From

Dictionary.com — react

Enact

verb

- to make into an act or statute: Parliament has enacted a new tax law.

- to represent on or as on the stage; act the part of: to enact Hamlet.

From

Dictionary.com — enact

Actor

noun

- a person who acts in stage plays, motion pictures, television broadcasts, etc.

- a person who does something; participant.

From

Dictionary.com — actor

Teachers should highlight and encourage students to analyse both Inflectional and Derivational morphemes when focussing on phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension.

For more information, see:

Prefixes, suffixes, and roots/bases

Many morphemes are very helpful for analysing unfamiliar words. Morphemes can be divided into prefixes, suffixes, and roots/bases.

- Prefixes are morphemes that attach to the front of a root/base word.

- Suffixes are morphemes that attach to the end of a root/base word, or to other suffixes (see example below)

- Roots/Base words are morphemes that form the base of a word, and usually carry its meaning.

- Generally, base words are free morphemes, that can stand by themselves (e.g. cycle as in bicycle/cyclist, and form as in transform/formation).

- Whereas root words are bound morphemes that cannot stand by themselves (e.g. -ject as in subject/reject, and -volve as in evolve/revolve).

Most morphemes can be divided into:

- Anglo-Saxon Morphemes (like re-, un-, and -ness);

- Latin Morphemes (like non-, ex-, -ion, and -ify); and

- Greek Morphemes (like micro, photo, graph).

It is useful to highlight how words can be broken down into morphemes (and which each of these mean) and how they can be built up again).

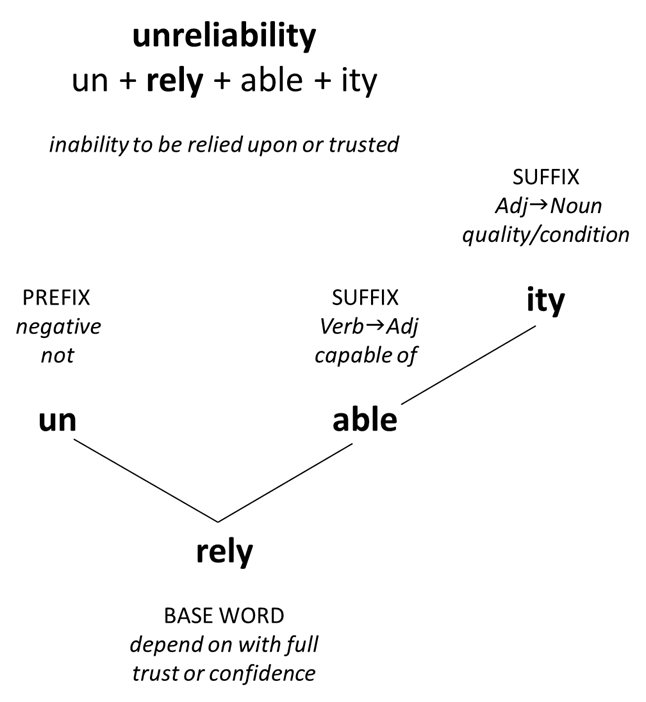

For example, the word <unreliability> may be unfamiliar to students when they first encounter it.

If <unreliability> is broken into its morphemes, students can deduce or infer the meaning.

So it is helpful for both reading and spelling to provide opportunities to analyse words, and become familiar with common morphemes, including their meaning and function.

Compound words

Compound words (or compounds) are created by joining free morphemes together. Remember that a free morpheme is a morpheme that can stand along as its own word (unlike bound morphemes — e.g. -ly, -ed, re-, pre-). Compounds are a fun and accessible way to introduce the idea that words can have multiple parts (morphemes). Teachers can highlight that these compound words are made up of two separate words joined together to make a new word. For example dog + house = doghouse

Examples

- lifetime

- basketball

- cannot

- fireworks

- inside

- upside

- footpath

- sunflower

- moonlight

- schoolhouse

- railroad

- skateboard

- meantime

- bypass

- sometimes

- airport

- butterflies

- grasshopper

- fireflies

- footprint

- something

- homemade

- backbone

- passport

- upstream

- spearmint

- earthquake

- backward

- football

- scapegoat

- eyeball

- afternoon

- sandstone

- meanwhile

- limestone

- keyboard

- seashore

- touchdown

- alongside

- subway

- toothpaste

- silversmith

- nearby

- raincheck

- blacksmith

- headquarters

- lukewarm

- underground

- horseback

- toothpick

- honeymoon

- bootstrap

- township

- dishwasher

- household

- weekend

- popcorn

- riverbank

- pickup

- bookcase

- babysitter

- saucepan

- bluefish

- hamburger

- honeydew

- thunderstorm

- spokesperson

- widespread

- hometown

- commonplace

- supermarket

Example activities of highlighting morphemes for phonics, vocabulary, and comprehension

There are numerous ways to highlight morphemes for the purpose of phonics, vocabulary and comprehension activities and lessons.

Highlighting the morphology of words is useful for explaining phonics patterns (graphemes) and spelling rules, as well as discovering the meanings of unfamiliar words, and demonstrating how words are linked together. Highlighting and analysing morphemes is also useful, therefore, for providing comprehension strategies.

Examples of how to embed morphological awareness into literacy activities can include:

- Sorting words by base/root words (word families), or by prefixes or suffixes

- Word Detective — Students break longer words down into their prefixes, suffixes, and base words

- e.g. Find the morphemes in multi-morphemic words like: dissatisfied unstoppable ridiculously hydrophobic metamorphosis oxygenate fortifications

- Word Builder — students are given base words and prefixes/suffixes and see how many words they can build, and what meaning they might have:

- Prefixes: un- de- pre- re- co- con-

Base Words: play help flex bend blue sad sat

Suffixes: -ful -ly -less -able/-ible -ing -ion -y -ish -ness -ment - Etymology investigation — students are given multi-morphemic words from texts they have been reading and are asked to research the origins (etymology) of the word. Teachers could use words like progressive, circumspect, revocation, and students could find out the morphemes within each word, their etymology, meanings, and use.

WORD STRUCTURE IN MODERN ENGLISH

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of morphemes. Allomorphs.

II. Structural types of words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of stems. Derivational types of words.

I. The morphological structure of a word. Morphemes. Types of Morphemes. Allomorphs.

There are two levels of approach to the study of word- structure: the level of morphemic analysis and the level of derivational or word-formation analysis.

Word is the principal and basic unit of the language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis.

It has been universally acknowledged that a great many words have a composite nature and are made up of morphemes, the basic units on the morphemic level, which are defined as the smallest indivisible two-facet language units.

The term morpheme is derived from Greek morphe “form ”+ -eme. The Greek suffix –eme has been adopted by linguistic to denote the smallest unit or the minimum distinctive feature.

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. A form in these cases a recurring discrete unit of speech. Morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words, not independently, although a word may consist of single morpheme. Even a cursory examination of the morphemic structure of English words reveals that they are composed of morphemes of different types: root-morphemes and affixational morphemes. Words that consist of a root and an affix are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word building known as affixation (or derivation).

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of the word; it has a very general and abstract lexical meaning common to a set of semantically related words constituting one word-cluster, e.g. (to) teach, teacher, teaching. Besides the lexical meaning root-morphemes possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots.

Affixational morphemes include inflectional affixes or inflections and derivational affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms. Derivational affixes are relevant for building various types of words. They are lexically always dependent on the root which they modify. They possess the same types of meaning as found in roots, but unlike root-morphemes most of them have the part-of-speech meaning which makes them structurally the important part of the word as they condition the lexico-grammatical class the word belongs to. Due to this component of their meaning the derivational affixes are classified into affixes building different parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives or adverbs.

Roots and derivational affixes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, fill-, are understood as the lexical centers of the words, and –less, -y, -ness, -er, re- are felt as morphemes dependent on these roots.

Distinction is also made of free and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes coincide with word-forms of independently functioning words. It is obvious that free morphemes can be found only among roots, so the morpheme boy- in the word boy is a free morpheme; in the word undesirable there is only one free morpheme desire-; the word pen-holder has two free morphemes pen- and hold-. It follows that bound morphemes are those that do not coincide with separate word- forms, consequently all derivational morphemes, such as –ness, -able, -er are bound. Root-morphemes may be both free and bound. The morphemes theor- in the words theory, theoretical, or horr- in the words horror, horrible, horrify; Angl- in Anglo-Saxon; Afr- in Afro-Asian are all bound roots as there are no identical word-forms.

It should also be noted that morphemes may have different phonemic shapes. In the word-cluster please , pleasing , pleasure , pleasant the phonemic shapes of the word stand in complementary distribution or in alternation with each other. All the representations of the given morpheme, that manifest alternation are called allomorphs/or morphemic variants/ of that morpheme.

The combining form allo- from Greek allos “other” is used in linguistic terminology to denote elements of a group whose members together consistute a structural unit of the language (allophones, allomorphs). Thus, for example, -ion/ -tion/ -sion/ -ation are the positional variants of the same suffix, they do not differ in meaning or function but show a slight difference in sound form depending on the final phoneme of the preceding stem. They are considered as variants of one and the same morpheme and called its allomorphs.

Allomorph is defined as a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and so characterized by complementary description.

Complementary distribution is said to take place, when two linguistic variants cannot appear in the same environment.

Different morphemes are characterized by contrastive distribution, i.e. if they occur in the same environment they signal different meanings. The suffixes –able and –ed, for instance, are different morphemes, not allomorphs, because adjectives in –able mean “ capable of beings”.

Allomorphs will also occur among prefixes. Their form then depends on the initials of the stem with which they will assimilate.

Two or more sound forms of a stem existing under conditions of complementary distribution may also be regarded as allomorphs, as, for instance, in long a: length n.

II. Structural types of words.

The morphological analysis of word- structure on the morphemic level aims at splitting the word into its constituent morphemes – the basic units at this level of analysis – and at determining their number and types. The four types (root words, derived words, compound, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word building.

According to the number of morphemes words can be classified into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. small, dog, make, give, etc. All polymorphic word fall into two subgroups: derived words and compound words – according to the number of root-morphemes they have. Derived words are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more derivational morphemes, e.g. acceptable, outdo, disagreeable, etc. Compound words are those which contain at least two root-morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant. There can be both root- and derivational morphemes in compounds as in pen-holder, light-mindedness, or only root-morphemes as in lamp-shade, eye-ball, etc.

These structural types are not of equal importance. The clue to the correct understanding of their comparative value lies in a careful consideration of: 1)the importance of each type in the existing wordstock, and 2) their frequency value in actual speech. Frequency is by far the most important factor. According to the available word counts made in different parts of speech, we find that derived words numerically constitute the largest class of words in the existing wordstock; derived nouns comprise approximately 67% of the total number, adjectives about 86%, whereas compound nouns make about 15% and adjectives about 4%. Root words come to 18% in nouns, i.e. a trifle more than the number of compound words; adjectives root words come to approximately 12%.

But we cannot fail to perceive that root-words occupy a predominant place. In English, according to the recent frequency counts, about 60% of the total number of nouns and 62% of the total number of adjectives in current use are root-words. Of the total number of adjectives and nouns, derived words comprise about 38% and 37% respectively while compound words comprise an insignificant 2% in nouns and 0.2% in adjectives. Thus it is the root-words that constitute the foundation and the backbone of the vocabulary and that are of paramount importance in speech. It should also be mentioned that root words are characterized by a high degree of collocability and a complex variety of meanings in contrast with words of other structural types whose semantic structures are much poorer. Root- words also serve as parent forms for all types of derived and compound words.

III. Principles of morphemic analysis.

In most cases the morphemic structure of words is transparent enough and individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word. The segmentation of words is generally carried out according to the method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. This method is based on the binary principle, i.e. each stage of the procedure involves two components the word immediately breaks into. At each stage these two components are referred to as the Immediate Constituents. Each Immediate Constituent at the next stage of analysis is in turn broken into smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents incapable of further division, i.e. morphemes. These are referred to Ultimate Constituents.

A synchronic morphological analysis is most effectively accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into Immediate Constituents. ICs are the two meaningful parts forming a large linguistic unity.

The method is based on the fact that a word characterized by morphological divisibility is involved in certain structural correlations. To sum up: as we break the word we obtain at any level only ICs one of which is the stem of the given word. All the time the analysis is based on the patterns characteristic of the English vocabulary. As a pattern showing the interdependence of all the constituents segregated at various stages, we obtain the following formula:

un+ { [ ( gent- + -le ) + -man ] + -ly}

Breaking a word into its Immediate Constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents.

A diagram presenting the four cuts described looks as follows:

1. un- / gentlemanly

2. un- / gentleman / — ly

3. un- / gentle / — man / — ly

4. un- / gentl / — e / — man / — ly

A similar analysis on the word-formation level showing not only the morphemic constituents of the word but also the structural pattern on which it is built.

The analysis of word-structure at the morphemic level must proceed to the stage of Ultimate Constituents. For example, the noun friendliness is first segmented into the ICs: [frendlı-] recurring in the adjectives friendly-looking and friendly and [-nıs] found in a countless number of nouns, such as unhappiness, blackness, sameness, etc. the IC [-nıs] is at the same time an UC of the word, as it cannot be broken into any smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. Any further division of –ness would give individual speech-sounds which denote nothing by themselves. The IC [frendlı-] is next broken into the ICs [-lı] and [frend-] which are both UCs of the word.

Morphemic analysis under the method of Ultimate Constituents may be carried out on the basis of two principles: the so-called root-principle and affix principle.

According to the affix principle the splitting of the word into its constituent morphemes is based on the identification of the affix within a set of words, e.g. the identification of the suffix –er leads to the segmentation of words singer, teacher, swimmer into the derivational morpheme – er and the roots teach- , sing-, drive-.

According to the root-principle, the segmentation of the word is based on the identification of the root-morpheme in a word-cluster, for example the identification of the root-morpheme agree- in the words agreeable, agreement, disagree.

As a rule, the application of these principles is sufficient for the morphemic segmentation of words.

However, the morphemic structure of words in a number of cases defies such analysis, as it is not always so transparent and simple as in the cases mentioned above. Sometimes not only the segmentation of words into morphemes, but the recognition of certain sound-clusters as morphemes become doubtful which naturally affects the classification of words. In words like retain, detain, contain or receive, deceive, conceive, perceive the sound-clusters [rı-], [dı-] seem to be singled quite easily, on the other hand, they undoubtedly have nothing in common with the phonetically identical prefixes re-, de- as found in words re-write, re-organize, de-organize, de-code. Moreover, neither the sound-cluster [rı-] or [dı-], nor the [-teın] or [-sı:v] possess any lexical or functional meaning of their own. Yet, these sound-clusters are felt as having a certain meaning because [rı-] distinguishes retain from detain and [-teın] distinguishes retain from receive.

It follows that all these sound-clusters have a differential and a certain distributional meaning as their order arrangement point to the affixal status of re-, de-, con-, per- and makes one understand —tain and –ceive as roots. The differential and distributional meanings seem to give sufficient ground to recognize these sound-clusters as morphemes, but as they lack lexical meaning of their own, they are set apart from all other types of morphemes and are known in linguistic literature as pseudo- morphemes. Pseudo- morphemes of the same kind are also encountered in words like rusty-fusty.

IV. Derivational level of analysis. Stems. Types of Stems. Derivational types of word.

The morphemic analysis of words only defines the constituent morphemes, determining their types and their meaning but does not reveal the hierarchy of the morphemes comprising the word. Words are no mere sum totals of morpheme, the latter reveal a definite, sometimes very complex interrelation. Morphemes are arranged according to certain rules, the arrangement differing in various types of words and particular groups within the same types. The pattern of morpheme arrangement underlies the classification of words into different types and enables one to understand how new words appear in the language. These relations within the word and the interrelations between different types and classes of words are known as derivative or word- formation relations.

The analysis of derivative relations aims at establishing a correlation between different types and the structural patterns words are built on. The basic unit at the derivational level is the stem.

The stem is defined as that part of the word which remains unchanged throughout its paradigm, thus the stem which appears in the paradigm (to) ask ( ), asks, asked, asking is ask-; thestem of the word singer ( ), singer’s, singers, singers’ is singer-. It is the stem of the word that takes the inflections which shape the word grammatically as one or another part of speech.

The structure of stems should be described in terms of IC’s analysis, which at this level aims at establishing the patterns of typical derivative relations within the stem and the derivative correlation between stems of different types.

There are three types of stems: simple, derived and compound.

Simple stems are semantically non-motivated and do not constitute a pattern on analogy with which new stems may be modeled. Simple stems are generally monomorphic and phonetically identical with the root morpheme. The derivational structure of stems does not always coincide with the result of morphemic analysis. Comparison proves that not all morphemes relevant at the morphemic level are relevant at the derivational level of analysis. It follows that bound morphemes and all types of pseudo- morphemes are irrelevant to the derivational structure of stems as they do not meet requirements of double opposition and derivative interrelations. So the stem of such words as retain, receive, horrible, pocket, motion, etc. should be regarded as simple, non- motivated stems.

Derived stems are built on stems of various structures though which they are motivated, i.e. derived stems are understood on the basis of the derivative relations between their IC’s and the correlated stems. The derived stems are mostly polymorphic in which case the segmentation results only in one IC that is itself a stem, the other IC being necessarily a derivational affix.

Derived stems are not necessarily polymorphic.

Compound stems are made up of two IC’s, both of which are themselves stems, for example match-box, driving-suit, pen-holder, etc. It is built by joining of two stems, one of which is simple, the other derived.

In more complex cases the result of the analysis at the two levels sometimes seems even to contracted one another.

The derivational types of words are classified according to the structure of their stems into simple, derived and compound words.

Derived words are those composed of one root- morpheme and one or more derivational morpheme.

Compound words contain at least two root- morphemes, the number of derivational morphemes being insignificant.

Derivational compound is a word formed by a simultaneous process of composition and derivational.

Compound words proper are formed by joining together stems of word already available in the language.

Теги:

Word structure in modern english

Реферат

Английский

Просмотров: 27751

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Word structure in modern english

Morphology is the study of words, word formation, and the relationship between words. In Morphology, we look at morphemes — the smallest lexical items of meaning. Studying morphemes helps us to understand the meaning, structure, and etymology (history) of words.

Morphemes: meaning

The word morphemes from the Greek morphḗ, meaning ‘shape, form‘. Morphemes are the smallest lexical items of meaning or grammatical function that a word can be broken down to. Morphemes are usually, but not always, words.

Look at the following examples of morphemes:

These words cannot be made shorter than they already are or they would stop being words or lose their meaning.

For example, ‘house’ cannot be split into ho- and -us’ as they are both meaningless.

However, not all morphemes are words.

For example, ‘s’ is not a word, but it is a morpheme; ‘s’ shows plurality and means ‘more than one’.

The word ‘books’ is made up of two morphemes: book + s.

Morphemes play a fundamental role in the structure and meaning of language, and understanding them can help us to better understand the words we use and the rules that govern their use.

How to identify a morpheme

You can identify morphemes by seeing if the word or letters in question meet the following criteria:

-

Morphemes must have meaning. E.g. the word ‘cat’ represents and small furry animal. The suffix ‘-s’ you might find at the end of the word ‘cat’ represents plurality.

- Morphemes cannot be divided into smaller parts without losing or changing their meaning. E.g. dividing the word ‘cat’ into ‘ca’ leaves us with a meaningless set of letters. The word ‘at’ is a morpheme in its own right.

Types of morphemes

There are two types of morphemes: free morphemes and bound morphemes.

Free morphemes

Free morphemes can stand alone and don’t need to be attached to any other morphemes to get their meaning. Most words are free morphemes, such as the above-mentioned words house, book, bed, light, world, people, and so on.

Bound morphemes

Bound morphemes, however, cannot stand alone. The most common example of bound morphemes are suffixes, such as —s, —er, —ing, and -est.

Let’s look at some examples of free and bound morphemes:

-

Tall

-

Tree

-

-er

-

-s

‘Tall’ and ‘Tree’ are free morphemes.

We understand what ‘tall’ and ‘tree’ mean; they don’t require extra add-ons. We can use them to create a simple sentence like ‘That tree is tall.’

On the other hand, ‘-er’ and ‘-s’ are bound morphemes. You won’t see them on their own because they are suffixes that add meaning to the words they are attached to.

So if we add ‘-er’ to ‘tall’ we get the comparative form ‘taller’, while ‘tree’ plus ‘-s’ becomes plural: ‘trees’.

Morphemes: structure

Morphemes are made up of two separate classes.

-

Bases (or roots)

-

Affixes

A morpheme’s base is the main root that gives the word its meaning.

On the other hand, an affix is a morpheme we can add that changes or modifies the meaning of the base.

‘Kind’ is the free base morpheme in the word ‘kindly’. (kind + -ly)

‘-less’ is a bound morpheme in the word ‘careless’. (Care + —less)

Morphemes: affixes

Affixes are bound morphemes that occur before or after a base word. They are made up of suffixes and prefixes.

Suffixes are attached to the end of the base or root word. Some of the most common suffixes include —er, -or, -ly, -ism, and -less.

Taller

Thinner

Comfortably

Absurdism

Ageism

Aimless

Fearless

Prefixes come before the base word. Typical prefixes include ante-, pre-, un-, and dis-.

Antedate

Prehistoric

Unkind

Disappear

Derivational affixes

Derivational affixes are used to change the meaning of a word by building on its base. For instance, by adding the prefix ‘un-‘ to the word ‘kind‘, we got a new word with a whole new meaning. In fact, ‘unkind‘ has the exact opposite meaning of ‘kind’!

Another example is adding the suffix ‘-or’ to the word ‘act’ to create ‘actor’. The word ‘act’ is a verb, whereas ‘actor’ is a noun.

Inflectional affixes

Inflectional affixes only modify the meaning of words instead of changing them. This means they modify the words by making them plural, comparative or superlative, or by changing the verb tense.

books — books

short — shorter

quick — quickest

walk — walked

climb — climbing

There are many derivational affixes in English, but only eight inflectional affixes and these are all suffixes.

|

Word class |

Modification reason |

Suffixes |

| To modify nouns | Plural & possessive forms | -s (or -es), -‘s (or s’) |

| To modify adjectives |

Comparative & superlative forms |

-er, -est |

| To modify verbs |

3rd person singular, past tense, present & past participles |

-s, -ed, -ing, -en |

All prefixes in English are derivational. However, suffixes may be either derivational or inflectional.

Morphemes: categories

The free morphemes we looked at earlier (such as tree, book, and tall) fall into two categories:

- Lexical morphemes

- Functional morphemes

Reminder: Most words are free morphemes because they have meaning on their own, such as house, book, bed, light, world, people etc.

Lexical morphemes

Lexical morphemes are words that give us the main meaning of a sentence, text or conversation. These words can be nouns, adjectives and verbs. Examples of lexical morphemes include:

- house

- book

- tree

- panther

- loud

- quiet

- big

- orange

- blue

- open

- run

- talk

Because we can add new lexical morphemes to a language (new words get added to the dictionary each year!), they are considered an ‘open’ class of words.

Functional morphemes

Functional (or grammatical) morphemes are mostly words that have a functional purpose, such as linking or referencing lexical words. Functional morphemes include prepositions, conjunctions, articles and pronouns. Examples of functional morphemes include:

- and

- but

- when

- because

- on

- near

- above

- in

- the

- that

- it

- them.

We can rarely add new functional morphemes to the language, so we call this a ‘closed’ class of words.

Allomorphs

Allomorphs are a variant of morphemes. An allomorph is a unit of meaning that can change its sound and spelling but doesn’t change its meaning and function.

In English, the indefinite article morpheme has two allomorphs. Its two forms are ‘a’ and ‘an’. If the indefinite article precedes a word beginning with a constant sound it is ‘a’, and if it precedes a word beginning with a vowel sound, it is ‘an’.

Past Tense allomorphs

In English, regular verbs use the past tense morpheme -ed; this shows us that the verb happened in the past. The pronunciation of this morpheme changes its sound according to the last consonant of the verb but always keeps its past tense function. This is an example of an allomorph.

Consider regular verbs ending in t or d, like ‘rent’ or ‘add’.

Now look at their past forms: ‘rented‘ and ‘added‘. Try pronouncing them. Notice how the —ed at the end changes to an /id/ sound (e.g. rent /ɪd/, add /ɪd/).

Now consider the past simple forms of want, rest, print, and plant. When we pronounce them, we get: wanted (want /ɪd/), rested (rest /ɪd/), printed (print /ɪd/), planted (plant /ɪd/).

Now look at other regular verbs ending in the following ‘voiceless’ phonemes: /p/, /k/, /s/, /h/, /ch/, /sh/, /f/, /x/. Try pronouncing the past form and notice how the allomorph ‘-ed’ at the end changes to a /t/ sound. For example, dropped, pressed, laughed, and washed.

Plural allomorphs

Typically we add ‘s’ or ‘es’ to most nouns in English when we want to create the plural form. The plural forms ‘s’ or ‘es’ remain the same and have the same function, but their sound changes depending on the form of the noun. The plural morpheme has three allomorphs: [s], [z], and [ɨz].

When a noun ends in a voiceless consonant (i.e. ch, f, k, p, s, sh, t, th), the plural allomorph is /s/.

Book becomes books (pronounced book/s/)

When a noun ends in a voiced phoneme (i.e. b, l, r, j, d, v, m, n, g, w, z, a, e, i, o, u) the plural form remains ‘s’ or ‘es’ but the allomorph sound changes to /z/.

Key becomes keys (pronounced key/z/)

Bee becomes bees (pronounced bee/z/)

When a noun ends in a sibilant (i.e. s, ss, z), the sound of the allomorph sound becomes /iz/.

Bus becomes buses (bus/iz/)

house becomes houses (hous/iz/)

A sibilant is a phonetic sound that makes a hissing sound, e.g. ‘s’ or ‘z’.

Zero (bound) morphemes

The zero bound morpheme has no phonetic form and is also referred to as an invisible affix, null morpheme, or ghost morpheme.

A zero morpheme is when a word changes its meaning but does not change its form.

In English, certain nouns and verbs do not change their appearance even when they change number or tense.

Sheep, deer, and fish, keep the same form whether they are used as singular or plural.

Some verbs like hit, cut, and cost remains the same in their present and past forms.

Morphemes — Key takeaways

- Morphemes are the smallest lexical unit of meaning. Most words are free morphemes, and most affixes are bound morphemes.

- There are two types of morphemes: free morphemes and bound morphemes.

- Free morphemes can stand alone, whereas bound morphemes must be attached to another morpheme to get their meaning.

- Morphemes are made up of two separate classes called bases (or roots) and affixes.

- Free morphemes fall into two categories; lexical and functional. Lexical morphemes are words that give us the main meaning of a sentence, and functional morphemes have a grammatical purpose.

Скачать материал

Скачать материал

- Сейчас обучается 396 человек из 63 регионов

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

1 слайд

Morphological Structure of English Words

-

2 слайд

The word as an autonomous unit of the language system should be distinguished from another fundamental language unit – the morpheme.

-

3 слайд

A morpheme

Is an association of a given meaning with a given sound pattern, which makes it similar to a word.

Unlike a word, a morpheme is not autonomous, morphemes occur in speech only as constituent parts of words.

Cannot be divided into smaller meaningful units, so it is defined as the minimum meaningful unit of the language system. -

4 слайд

According to their form

Morphemes

Free

Bound

Semi-bound

(semi-free) -

5 слайд

Free morphemes

Are capable of forming words without adding other morphemes, which means that they coincide with the stems or independent forms of words:

House- (morpheme) = house (word)

Shoe- (morpheme) = shoe (word)

Bread- (morpheme) = bread (word) -

6 слайд

Bound morphemes

May not stand alone without a loss or change of their meaning, they are always bound to something else. It means that they do not coincide with stems or independent forms of words:

Horr- (morpheme) – horr-or (word)

Agit- (morpheme) – agit-ate (word)

Nat- (morpheme) – nat-ion (word)

-Ible (morpheme) – elig-ible (word)

Pre- (morpheme) – pre-war (word) -

7 слайд

Free and Bound morphemes

Prefixes and suffixes (jointly called derivational affixes) are always bound

Root morphemes may be both free and bound

Bound root morphemes are mainly found among loan words: arrog-ance, char-ity, cour-age, dis-tort, in-volve, toler-able, etc. -

8 слайд

Semi-bound (semi-free) morphemes

Can function in a morphemic sequence both as an affix and as a free morpheme:

E.g., the morphemes «well» and «half» can occur as free morphemes (cf. sleep well, half an hour) or as bound morphemes (cf. well-known, half-done) -

9 слайд

According to their role in constructing words

Morphemes

Roots

Affixes -

10 слайд

According to their position in a word

Affixes

Prefixes

Suffixes

Infixes

(unproductive

in English) -

11 слайд

According to their function and meaning

Affixes

Derivational

Functional

(Endings,

inflexions) -

12 слайд

A stem

When a derivational or functional affix is stripped from the word, what remains is a stem (a stem base)

If a stem consists of a single morpheme, it is simple (heart, fact, month, red, etc.)

If a stem consists of a root and an affix, it is derived (hearty, factual, monthly, reddish, etc.)

If a stem consists of two root morphemes (and an affix / affixes), it is compound (teaspoon, mother-in-law, dog-owner, looking-glass, etc.) -

13 слайд

A root

Is the main morphemic vehicle of a given idea in a given language at a given stage of its development

Is the ultimate constituent element which remains after the removal of all functional and derivational affixes and does not admit any further analysis

Is the common element of words within a word-cluster (cf. heart, hearten, dishearten, heartily, heartless, hearty, heartiness, sweetheart, heart-broken, etc.) -

14 слайд

A root

The etymological treatment of root morphemes encourages a search for cognates (elements descended from a common ancestor):

Heart (English) – cor (Latin) – kardia (Greek) – corazon (Spanish) – Herz (German) – сердце (Russian), etc. -

15 слайд

A suffix

Is a derivational morpheme following the stem and forming a new derivative in a different part of speech or a different word class: luck – luck-y – luck-i-ly -

16 слайд

A prefix

Is a derivational morpheme standing before the root and modifying the meaning of the original word: happy – unhappy, president – ex-president, argument – counter-argument, etc. -

17 слайд

A prefix

Prefixes do not generally change the part-of-speech meaning of the resultant word

An exception to the rule is the formation of some verbs and statives: friend, n – befriend, v; earth, n – unearth (выкапывать, вырывать из земли, доставать из-под земли), v; sleep, n – asleep (stative), etc. -

18 слайд

An infix

Is an affix placed within the word: -n- in «stand» (this type is not productive). -

19 слайд

Combining forms

Affixes should not be confused with combining forms

A combining form is a bound form that is distinguished from an affix historically by the fact that it is always borrowed from another language in which it existed as a free or combining form. -

20 слайд

Combining forms

Most combining forms were borrowed from Latin and Greek (however, not exclusively) and have thus become international:

Cyclo- (from Greek «kuklos» — circle): cyclometer, cyclopedia, cyclic, bicycle, etc.

Mal- (from French «mal» — bad): malfunction, malnutrition, etc.

Compound and derivative words which these combining forms are part of never existed in their original language but were coined only in modern times. -

21 слайд

Morphemic and Structural Analysis of English Words

-

22 слайд

Morphemic analysis

Implies stating the number and type of morphemes that make up the word:

Girl (one root morpheme) – a root word

Girlish (one root morpheme plus one affix) – a derived word

Girl-friend (two stems) – a compound word

Last-minuter (two stems and a common affix) – a compound derivative -

23 слайд

Structural word-formation analysis

Studies the structural correlation with other words as well as the structural patterns or rules on which words are built

-

24 слайд

Structural word-formation analysis

A correlation is a set of binary oppositions, in which each second element is derived from the first by a general rule valid for all members of the relation:

Child – childish

Woman – womanish

Monkey – monkeyish

Spinster – spinsterish, etc. -

25 слайд

Structural word-formation analysis

This correlation demonstrates that

in English there is a type of derived adjectives consisting of a noun stem and a suffix –ish;

the stems are mostly those of animate nouns;

any one word built according to this pattern contains a semantic component common to the whole group, namely «typical of, or having the bad qualities of». -

26 слайд

Morphological Analysis of English Words

-

27 слайд

A synchronic morphological analysis (introduced by

L. Bloomfield)

Is accomplished by the procedure known as the analysis into immediate constituents

The main opposition here is the opposition of stem and affix which reveals the motivation of the word -

28 слайд

A synchronic morphological analysis

Ungentlemanly

Un-

gentlemanly

gentleman

ly

gentle

man

gent

le -

29 слайд

A synchronic morphological analysis

Un- is split after the pattern: un- + adjective stem (uncertain, unconscious, uneasy, unearthly, untimely, unwomanly, etc.);

-Ly is split following the pattern: noun stem + -ly (womanly, masterly, scholarly, etc.);

Gentleman is split into gentle- + -man after a similar pattern observed in «nobleman» (adjective stem + the semi-affix -man)

Gentle is split into gent- + -le following the pattern: noun stem + -le (brittle, fertile, juvenile, noble, subtle, little, etc.) -

30 слайд

A synchronic morphological analysis

The constituents that allow further splitting into morphemes are called immediate (gentlemanly, gentleman, gentle),

Those that don’t allow this are termed ultimate (un-, -ly, gent-, le-, -man). -

31 слайд

A synchronic morphological analysis

The procedure of the analysis into immediate constituents is reduced to the recognition and classification of the same and different morphemes as well as same and different patterns: thus it permits the tracing and understanding of the vocabulary system. -

32 слайд

Thank you for your attention!

Найдите материал к любому уроку, указав свой предмет (категорию), класс, учебник и тему:

6 210 144 материала в базе

- Выберите категорию:

- Выберите учебник и тему

- Выберите класс:

-

Тип материала:

-

Все материалы

-

Статьи

-

Научные работы

-

Видеоуроки

-

Презентации

-

Конспекты

-

Тесты

-

Рабочие программы

-

Другие методич. материалы

-

Найти материалы

Другие материалы

- 02.12.2020

- 132

- 0

- 26.10.2020

- 450

- 4

- 15.08.2020

- 157

- 0

- 08.08.2020

- 396

- 0

- 26.07.2020

- 75

- 0

- 09.06.2020

- 558

- 13

- 05.06.2020

- 91

- 1

- 06.05.2020

- 519

- 2

Вам будут интересны эти курсы:

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Управление персоналом и оформление трудовых отношений»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Основы управления проектами в условиях реализации ФГОС»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Экскурсоведение: основы организации экскурсионной деятельности»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Клиническая психология: теория и методика преподавания в образовательной организации»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация практики студентов в соответствии с требованиями ФГОС юридических направлений подготовки»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация деятельности по подбору и оценке персонала (рекрутинг)»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Маркетинг в организации как средство привлечения новых клиентов»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Разработка бизнес-плана и анализ инвестиционных проектов»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Управление сервисами информационных технологий»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация технической поддержки клиентов при установке и эксплуатации информационно-коммуникационных систем»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Корпоративная культура как фактор эффективности современной организации»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Политология: взаимодействие с органами государственной власти и управления, негосударственными и международными организациями»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Уголовно-правовые дисциплины: теория и методика преподавания в образовательной организации»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Гостиничный менеджмент: организация управления текущей деятельностью»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Информационная поддержка бизнес-процессов в организации»

10.1. The morphological structure of English words.

10.2. Definition of word-formation. Synchronic and diachronic approaches to word formation.

10.3. Main units of word-formation. Derivational analysis.

10.4. Ways of word-formation.

10.5. Functional approach to word-formation.

10.6. The communicative aspect of word-formation.

10.1. Structurally, words are divisible into smaller units which are called morphemes. Morphemes are the smallest indivisible two-facet (significant) units. A morpheme exists only as a constituent part of the word.

One morpheme may have different phonemic shapes, i.e. it is represented by allomorphs (its variants),

e.g. in please, pleasure, pleasant [pli: z], [ple3-], [plez-] are allomorphs of one morpheme.

Semantically, all morphemes are classified into roots and affixes. The root is the lexical centre of the word, its basic part; it has an individual lexical meaning,

e.g. in help, helper, helpful, helpless, helping, unhelpful — help- is the root.

Affixes are used to build stems; they are classified into prefixes and suffixes; there are also infixes. A prefix precedes the root, a suffix follows it; an infix is inserted in the body of the word,

e.g. prefixes: re -think, mis -take, dis -cover, over -eat, ex -wife;

suffixes: danger- ous, familiar- ize, kind- ness, swea- ty etc.

Structurally, morphemes fall into: free morphemes, bound morphemes, semi-bound (semi-free) morphemes.

A free morpheme is one that coincides with a stem or a word-form. A great many root-morphemes are free,

e.g. in friendship the root -friend — is free as it coincides with a word-form of the noun friend.

A bound morpheme occurs only as a part of a word. All affixes are bound morphemes because they always make part of a word,

e.g. in friendship the suffix -ship is a bound morpheme.

Some root morphemes are also bound as they always occur in combination with other roots and/or affixes,

e.g. in conceive, receive, perceive — ceive — is a bound root.

To this group belong so-called combining forms, root morphemes of Greek and Latin origin,

e.g. tele -, mega, — logy, micro -, — phone: telephone, microphone, telegraph, etc.

Semi-bound morphemes are those that can function both as a free root morpheme and as an affix (sometimes with a change of sound form and/or meaning),

e.g. proof, a. » giving or having protection against smth harmful or unwanted» (a free root morpheme): proof against weather;

-proof (in adjectives) » treated or made so as not to be harmed by or so as to give protection against» (a semi-bound morpheme): bulletproof, ovenproof, dustproof, etc.

Morphemic analysis aims at determining the morphemic (morphological) structure of a word, i.e. the aim is to split the word into morphemes and state their number, types and the pattern of arrangement. The basic unit of morphemic analysis is the morpheme.

In segmenting words into morphemes, we use the method of Immediate and Unltimate Constituents. At each stage of the analysis, a word is broken down into two meaningful parts (ICs, i.e. Immediate Constituents). At the next stage, each IC is broken down into two smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we get indivisible constituents, i.e. Ultimate Constituents, or morphs, which represent morphemes in concrete words,

e.g.

Friend-, -ly, -ness are indivisible into smaller meaningful units, so they are Ultimate Constituents (morphs) and the word friendliness consists of 3 morphemes: friend-+-li+-ness.

There are two structural types of words at the morphemic level of analysis: monomorphic (non-segmentable, indivisible) and polymorphic words (segmentable, divisible). The former consist only of a root morpheme, e.g. cat, give, soon, blue, oh, three. The latter consist of two or more morphemes, e.g. disagreeableness is a polymorphic word which consists of four morphemes, one root and three affixes: dis- + -agree- + -able + -ness. The morphemic structure is Pr + R + Sf1 + Sf2.

10.2. Word-Formation (W-F) is building words from available linguistic material after certain structural and semantic patterns. It is also a branch of lexicology that studies the process of building words as well as the derivative structure of words, the patterns on which they are built and derivational relations between words.

Synchronically, linguists study the system of W-F at a given time; diachronically, they are concerned with the history of W-F, and the history of building concrete words. The results of the synchronic and the diachronic analysis may not always coincide,

e.g. historically, to beg was derived from beggar, but synchronically the noun beggar is considered derived from the verb after the pattern v + -er/-ar → N, as the noun is structurally and semantically more complex. Cf. also: peddle- ← -pedlar/peddler, lie ← liar.

10.3. The aim of derivational analysis is to determine the derivational structure of a word, i.e. to state the derivational pattern after which it is built and the derivational base (the source of derivation).

Traditionally, the basic units of derivational analysis are: the derived word (the derivative), the derivational base, the derivational pattern, the derivational affix.

The derivational base is the source of a derived word, i.e. a stem, a word-form, a word-group (sometimes even a sentence) which motivates the derivative semantically and on which the latter is based structurally,

e.g. in dutifully the base is dutiful-, which is a stem;

in unsmiling it is the word-form smiling (participle I);

in blue-eyed it is the word-group blue eye.

In affixation, derivational affixes are added to derivational bases to build new words, i.e. derivatives. They repattern the bases, changing them structurally and semantically. They also mark derivational relations between words,

e.g. in encouragement en- and -ment are derivational affixes: a prefix and a suffix; they are used to build the word encouragement: (en- + courage) + -ment.

They also mark the derivational relations between courage and encourage, encourage and encouragement.

A derivational pattern is a scheme (a formula) describing the structure of derived words already existing in the language and after which new words may be built,

e.g. the pattern of friendliness is a+ -ness- → N, i.e. an adjective stem + the noun-forming suffix -ness.

Derivationally, all words fall into two classes: simple (non-derived) words and derivatives. Simple words are those that are non-motivated semantically and independent of other linguistic units structurally, e.g. boy, run, quiet, receive, etc. Derived words are motivated structurally and semantically by other linguistic units, e.g. to spam, spamming, spammer, anti-spamming are motivated by spam.

Each derived word is characterized by a certain derivational structure. In traditional linguistics, the derivational structure is viewed as a binary entity, reflecting the relationship between derivational bases and derivatives and consisting of a stem and a derivational affix,

e.g. the structure of nationalization is nationaliz- + -ation

(described by the formula, or pattern v + -ation → N).

But there is a different point of view. In modern W-F, the derivational structure of a word is defined as a finite set of derivational steps necessary to produce (build) the derived word,

e.g. [(nation + -al) + — ize ] + -ation.

To describe derivational structures and derivational relations, it is convenient to use the relator language and a system of oriented graphs. In this language, a word is generated by joining relators to the amorphous root O. Thus, R1O describes the structure of a simple verb (cut, permiate); R2O shows the structure of a simple noun (friend, nation); R3O is a simple adjective (small, gregarious) and R4O is a simple adverb (then, late).

e.g. The derivational structure of nationalization is described by the R-formula R2R1R3R2O; the R-formula of unemployment is R2R2R1O (employ → employment → unemployment).

In oriented graphs, a branch slanting left and down » /» correspond to R1; a vertical branch » I» corresponds to R2; a branch slanting right and down » » to R3, and a horizontal right branch to R4.

and dutifulness like this:

Words whose derivational structures can be described by one R-formula are called monostructural, e.g. dutifulness, encouragement; words whose derivational structures can be described by two (or more) R-formulas are polystructural,

e.g. disagreement R2R2R1O / R2R1R1O

(agree → disagree → disagreement R2R1R1O or

agree → agreement → disagreement R2R2R1O)

There are complex units of word-formation. They are derivational clusters and derivational sets.

A derivational cluster is a group of words that have the same root and are derivationally related. The structure of a cluster can be shown with the help of a graph,

reread read

misreadreaderreadable

reading

readership ∙ unreadable

A derivational set is a group of words that are built after the same derivational pattern,

e.g. n + -ish → A: mulish, dollish, apish, bookish, wolfish, etc,

Table TWO TYPES OF STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS

| MORPHEMIC ANALYSIS | DERIVATIONAL ANALYSIS | |

| AIM | to find out the morphemic structure (composition) | to determine the derivational structure |

| BASIC UNITS | morphemes (roots and affixes) | derived word, derivational pattern, derivational base, derivational step, derivational means (e.g. affix) |

| RESULTS: CLASSES OF WORDS | monomorphic (non-segmentable) and polymorphic (segmentable) words | simple and derived words |

| EXAMPLES | 1. cut, v. and cut, n. are monomorphic (root) words | 1. cut, v. is a simple word (R1O); cut, n. is derived from it (R2R1O) |

| 2. encouragement, unemployment consist of three morphemes and have the same morphemic composition: Pr + R + Sf | 2. encouragement and unemployment have different derivational structures: v + -ment → N (R2R1R2O) and un- + n → N (R2R2R1O) |

10.4. Traditionally, the following ways of W-F are distinguished:

affixation, compounding, conversion, shortening, blending, back-formation. Sound interchange, sound imitation, distinctive stress, lexicalization, coinage certainly do not belong to word-formation as no derivational patterns are used.

Affixation is formation of words by adding derivational affixes to derivational bases. Affixation is devided into prefixation and suffixation,

e.g. the following prefixes and suffixes are used to build words with negative or opposite meanings: un-, non-, a-, contra-, counter-, de-, dis-, in-, mis-, -less, e.g. non-toxic.

Compounding is building words by combining two (or more) derivational bases (stems or word-forms),

e.g. big -ticket (= expensive), fifty-fifty, laid-back, statesman.

Among compounds, we distinguish derivational compounds, formed by adding a derivational affix (usu. a suffix) to a word group,

e.g. heart-shaped (= shaped like a heart), stone-cutter (= one who cuts stone).

Conversion consists in making a word from some existing word by transferring it into another part of speech. The new word acquires a new paradigm; the sound form and the morphimic composition remain unchanged. The most productive conversion patterns are n → V (i.e. formation of verbs from noun-stems), v → N (formation of nouns from verb stems), a → V (formation of verbs from adjective stems),

e.g. a drink, a do, a go, a swim: Have another try.

to face, to nose, to paper, to mother, to ape;

to cool, to pale, to rough, to black, to yellow, etc.

Nouns and verbs can be converted from other parts of speech, too, for example, adverbs: to down, to out, to up; ifs and buts.

Shortening consists in substituting a part for a whole. Shortening may result in building new lexical items (i.e. lexical shortenings) and so-called graphic abbreviations, which are not words but signs representing words in written speech; in reading, they are substituted by the words they stand for,

e.g. Dr = doctor, St = street, saint, Oct = 0ctober, etc.

Lexical shortenings are produced in two ways:

(1) clipping, i.e. a new word is made from a syllable (or two syllables) of the original word,

e.g. back-clippings: pro ← professional, chimp ← chimpanzee,

fore-clippings: copter ← helicopter, gator ← alligator,

fore-and-aft clippings: duct ← deduction, tec ← detective,

(2) abbreviation, i.e. a new word is made from the initial letters of the original word or word-group. Abbreviations are devided into letter-based initialisms (FBI ← the Federal Bureau of Investigation) and acronyms pronounced as root words (AIDS, NATO).

Blending is building new words, called blends, fusions, telescopic words, or portmanteau words, by merging (usu.irregular) fragments of two existing words,

e.g. biopic ← biography + picture, alcoholiday ← alcohol + holiday.

Back-formation is derivation of new words by subtracting a real or supposed affix (usu. a suffix) from existing words (on analogy with existing derivational pairs),

e.g. to enthuse ← enthusiasm, to intuit ← intuition.

Sound interchange and distinctive stress are not ways of word-formation. They are ways of distinguishing words or word forms,

e.g. food -feed, speech — speak, life — live;

‘ insult, n. — in ‘ sult, v., ‘ perfect, a. — per ‘ fect, v.

Sound interchange may be combined with affixation and/or the shift of stress,

e.g. strong — strength, wide — width.

10.5. Productivity and activity of derivational ways and means.

Productivity and activity in W-F are close but not identical. By productivity of derivational ways/types/patterns/means we mean ability to derive new words,

e.g. The suffix -er/ the pattern v + -er → N is highly productive.

By activity we mean the number of words derived with the help of a certain derivational means or after a derivational pattern,

e.g. — er is found in hundreds of words so it is active.

Sometimes productivity and activity go together, but they may not always do.

| DERIVATIONAL MEANS | EXAMPLE | PRODUCTIVITY | ACTIVITY |

| -ly | nicely | + | + |

| -ous | dangerous | _ | + |

| -th | breadth | _ | _ |

In modern English, the most productive way of W-P is affixation (suffixation more so than prefixation), then comes compounding, shortening takes third place, with conversion coming fourth.

Productivity may change historically. Some derivational means / patterns may be non-productive for centuries or decades, then become productive, then decline again,

e.g. In the late 19th c. US -ine was a popular feminine suffix on the analogy of heroine, forming such words as actorine, doctorine, speakerine. It is not productive or active now.

|

Расчетные и графические задания Равновесный объем — это объем, определяемый равенством спроса и предложения… |

Кардиналистский и ординалистский подходы Кардиналистский (количественный подход) к анализу полезности основан на представлении о возможности измерения различных благ в условных единицах полезности… |

Обзор компонентов Multisim Компоненты – это основа любой схемы, это все элементы, из которых она состоит. Multisim оперирует с двумя категориями… |

Композиция из абстрактных геометрических фигур Данная композиция состоит из линий, штриховки, абстрактных геометрических форм… |

|

Внешняя политика России 1894- 1917 гг. Внешнюю политику Николая II и первый период его царствования определяли, по меньшей мере три важных фактора… Оценка качества Анализ документации. Имеющийся рецепт, паспорт письменного контроля и номер лекарственной формы соответствуют друг другу. Ингредиенты совместимы, расчеты сделаны верно, паспорт письменного контроля выписан верно. Правильность упаковки и оформления…. БИОХИМИЯ ТКАНЕЙ ЗУБА В составе зуба выделяют минерализованные и неминерализованные ткани… |