способность,

inability

неспособность;

disability

нетрудоспособность

способный, умелый

unable

неспособный

disabled

искалеченный; инвалид

дать возможность

disable

делать неспособным, калечить

умело, искусно

абсурдность

абсурдный

приемлемость

приемлемый

unacceptable

неприемлемый

принимать, соглашаться

доступ

accessibility

доступность

доступный

доступно

случай, случайность

случайный

нечаянно, случайно

действие

actor

актер

actress

актриса

activity

активность

activities

деятельность

acting

представление

активный

acting

действующий, работающей

действовать

активно

достижение

достигать

привычка, приверженность, увлеченность

addict

увлеченный человек, имеющий стойкую привычку

способный вызывать привычку

увлекаться, предаваться

восхищение

восхитительный

восхищаться

восхитительно

совет

рекомендуемый

советовать

притворство, искусственность

affection

привязанность, любовь

притворный

affectionate

любящий

affective

эмоциональный

воздействовать, влиять; притворяться

соглашение, согласие

disagreement

разногласие, несогласие

соответствующий, приятный

соглашаться

disagree

не соглашаться

соответственно

агрессия

aggressor

агрессору зачинщик

агрессивный

нападать

агрессивно

цель

бесцельный

целиться, намереваться

бесцельно

то, что может быть позволено

unaffordable

то, что невозможно себе позволить

позволять себе

развлечение

приятно изумленный

amusing

забавный

развлекать, забавлять

изумленно

внешность; появление

disappearance

исчезновение

появляться

disappear

исчезать

назначение; деловая встреча

disappointment

разочарование, досада

назначенный

disappointed

огорченный

disappointing

разочаровывающий

назначать

disappoint

разочаровывать

одобрение

одобренный

approving

одобрительный

одобрять

одобрительно

соглашение; расположение

приведенный в порядок

приводить в порядок, организовывать

аргумент, довод

argumentation

аргументация

доказуемый (в споре)

argumentative

спорный, конфликтный

утверждать, спорить, ссориться

доказательно

присвоение; ассигнование

подходящий, соответствующий

inappropriate

несоответствущий, неуместный

присваивать, предназначать

соответственно, подходяще

прибытие

прибывать, приезжать

притяжение, привлекательность

привлеченный

attractive

привлекательный

привлекать

привлекательно

избежание, отмена

то, чего можно избежать

unavoidable

неизбежный

избегать

неизбежно

красота; красавица

красивый

украшать

красиво

роды

сносный, допустимый

unbearable

невыносимый

носить; терпеть

невыносимо

вера

вероятный, правдоподобный

unbelievable

невероятный

верить

выгода

выгодный

получать выгоду

зануда

boredom

скука

испытывающий скуку

boring

скучный, надоедливый

надоедать

скучно

дыхание, дуновение

breathing

дыхание

breather

короткая передышка

дышащий

breathless

бездыханный

дышать

затаив дыхание

дело

businessman

деловой мужчина

businesswoman

деловая женщина

занятой

businesslike

деловой, практичный

занимать делом

деловито, по-деловому

забота, уход

заботливый

careless

небрежный

заботиться, любить

заботливо

carelessly

небрежно

празднование

celebrity

знаменитость

знаменитый, прославленный

праздновать, прославлять

определенность

uncertainty

неопределенность, неуверенность

определенный

uncertain

неопределенный

определенно, уверенно

изменение; мелочь, сдача

изменчивый

changed

изменившийся

changeless

неизменный

unchanged

не изменившийся

менять; обменивать(ся)

неизменно

характер

характерный, типичный

характеризовать

выбор

разборчивый

выбирать

ребенок

children

дети

детский; ребяческий

очистка; устранение препятствий

четкий, ясный

очищать, расчищать

четко, ясно

облако

облачный

cloudless

безоблачный

собрание; коллекция

collector

сборщик

коллективный, совокупный

собирать; коллекционировать

колония

колониальный

колонизировать

цвет

цветной

colourless

бесцветный

multi-coloured

разноцветный

раскрашивать

комфорт; утешение

discomfort

беспокойство; неудобство

удобный, комфортабельный

uncomfortable

неудобный

утешать, успокаивать

удобно

uncomfortably

неудобно

община, общество

общественный, коллективный

сообщение

communicator

коммуникатор, переговорщик

использующийся в общении; коммуникативный

сообщать; общаться

сравнение

сравниваемый

comparative

сравнительный

сравнивать

сравнительно, относительно

соревнование; конкуренция

competitor

конкурент, соперник

соревновательный

соревноваться, конкурировать

в форме соревнования, конкуренции

завершение, окончание

законченный

complete

полный, завершенный

incomplete

неполный, назавершенный

заканчивать, завершать

полностью

поздравление

поздравлять

соединение, объединение

связанный, соединенный

соединять

disconnect

разъединять

внимание; рассмотрение, обсуждение

значительный

considerate

внимательный, деликатный, тактичный

inconsiderate

неосмотрительный; невнимательный к другим

считать, полагать; рассматривать

значительно

совесть

совестливый, добросовестный

conscientiousless

бессовестный

добросовестно

сознание

осознающий

unconscious

без сознания

сознательно, осознанно

консультация

consultant

консультант

консультирующий

консультировать

вместилище, контейнер

содержащий

содержать, вмещать

непрерывность

продолжающийся, длящийся

продолжать

непрерывно

управление, руководство

поддающийся управлению

uncontrollable

неподдающийся управлению

controlled

управляемый

uncontrolled

неуправляемый

управлять, регулировать

бесконтрольно

убеждение

убедительный

convinced

убежденный

убеждать

убедительно

повар

cooker

плита, духовка

переваренный

under-cooked

недоваренный

готовить еду

исправление

corrector

корректор

правильный

incorrect

неправильный

исправлять

правильно

прилавок

discount

скидка

accountant

бухгалтер

исчисляемый

uncountable

неисчисляемый

считать

немеряно, без счета

храбрость

храбрый

encouraged

воодушевленный

encouraging

подбадривающий

discouraged

обескураженный

приободрять, поддерживать

discourage

отговаривать, обескураживать

смело, храбро

создание

creativity

творчество

creator

творец, создатель

creature

творение; живое существо

творческий

создавать, творить

творчески

вера, доверие

вероятный, заслуживающий доверия

incredible

невероятный

вероятно

incredibly

невероятно

критик

criticism

критика

критический; переломный; рискованный

критиковать

критично, критически

культивация, обработка

культивированный, обработанный

обрабатывать

культура

культурный, воспитанный

cultural

культурный (как часть культуры)

культурно

лекарство; лечение

излечимый

incurable

неизлечимый

вылечивать, исцелять

неизлечимо

опасность

опасный

угрожать

опасно

день

ежедневный

ежедневно

обман, заблуждение

обманчивый

deceitful

обманчивый, лживый

обманывать

обманчиво, предательски

решение

определенный, явный

undecided

нерешительный, неясный

decisive

решительный, убежденный, убедительный

решать, принимать решение

решительно, определенно

определение

четкий, определенный

indefinite

неопределенный

определять, давать определение

определенно, ясно

indefinitely

нечетко, неопределенно

восторг, наслаждение

восхитительный

delighted

польщенный

восхищаться

с восторгом

доставка, поставка

доставленный

доставлять

зависимость

independence

независимость

зависимый

independent

независимый

зависеть

независимо

депрессия, подавленность

депрессивный, вызывающий депрессию

depressed

подавленный

подавлять

описание

описательный, наглядный

описывать

проект, дизайн

designer

дизайнер, проектировщик

проектировать

желание, стремление

желательный, желаемый

undesirable

нежелательный

желать, стремиться

желательно

разрушение

разрушенный

разрушать, уничтожать

решительность; определение

решительный

решать, определять

развитие

developer

разработчик

развитой

developing

развивающийся

undeveloped

неразвитый

развивать(ся)

умирающий

умирать

разница, различие

indifference

безразличие

другой, отличающийся

indifferent

безразличный

отличаться

по-другому

indifferently

с безразличием

тревога, беспокойство; нарушение тишины, порядка

обеспокоенный

disturbing

беспокоящий

беспокоить, мешать

сомнение

сомнительный

doubtless

несомненный

undoubted

бесспорный

сомневаться

с сомнением

doubtlessly

не сомневаясь

undoubtedly

без сомнения

легкость, свобода

disease

болезнь

легкий

uneasy

неловкий, тревожный

облегчать, ослаблять

легко

uneasily

неловко

хозяйство

экономический

economical

экономный

экономить

экономически; экономно

воспитатель, педагог

education

образование

образованный

uneducated

необразованный

educative

образовательный

воспитывать, давать образование

следствие, результат

effectiveness

эффективность

эффективный, действующий

производить, выполнять

эффективно, действенно

электричество

electrician

электрик

электрический

электрифицировать

империя

empiror

император

имперский

empiric / empirical

исходящий из опыта, эмпирический

служба, работа

unemployment

безработица

employer

наниматель, работодатель

employee

работающий по найму

нанятый, занятый

unemployed

безработный

нанимать

конец, окончание

бесконечный

unending

нескончаемый

конец, окончание

бесконечно

окружающая среда

природный

развлечение

развлекательный

развлекать

энтузиазм, восторг

enthusiast

энтузиаст, восторженный человек

восторженный

с восторгом

оборудование

снаряженный, оборудованный

снаряжать

сущность

главный, основной

главным образом

экзамен; медосмотр

проэкзаменованный; осмотренный врачом

экзаменовать; осматривать

возбуждение, волнение

возбуждающий

excitable

возбудимый

excited

возбужденный, взволнованный

возбуждать, волновать

взволнованно, возбужденно

ожидание, предчувствие

ожидаемый

unexpected

неожиданный

ожидать, предчувствовать

расход(ы), затраты

дорогой

inexpensive

недорогой

тратить, расходовать

дорого

опыт, опытность

inexperience

неопытность

experiment

эксперимент

опытный

inexperienced

неопытный

experimental

эспериментальный

испытывать

взрыв

explosive

взрывчатое вещество

взрывчатый

взрываться

выражение

выразительный

выражать

выразительно

пространство, степень

длительный,обширный

extensive

обширный

простираться, тянуться

обширно, протяженно

крайняя степень, крайность

крайний, чрезвычайный

крайне

очарование, обаяние

чарующий

fascinated

очарованный

очаровывать

справедливость; порядочность

порядочный, справедливый

unfair

несправедливый

справедливо, честно; довольно-таки

финансы

финансовый

финансировать

финансово

твердость

твердый

утверждать

твердо

физическая форма, физическое состояние

находящийся в хорошей форме; подходящий

unfit

неподходящий

подгонять, подстраивать

следующий

следовать

глупыш, дурак

глупый

обманывать

глупо

забываемый

unforgettable

незабываемый

forgetful

забывчивый

forgotten

забытый

забывать

прощение

прощающий

forgivable

простительный

unforgivable

непростительный

прощать

с прощением

судьба, счастье; богатство, состояние

счастливый

unfortunate

несчастный

к счастью

unfortunately

к сожалению

свобода

свободный; бесплатный

свободно

частота

частый

часто посещать

часто

друг

friendship

дружба

friendliness

дружелюбие

дружеский, дружелюбный

unfriendly

недружеский

дружелюбно

страх, испуг

страшный

frightened

испуганный

frightening

пугающий

пугать, устрашать

страшно; испуганно

щедрость

щедрый

щедро

джентльмен

мягкий, нежный

мягко, нежно

привидение, призрак

похожий на привидение

трава

травяной

привычка, обычай

habitant

обитатель

habitat

естественная среда

habitation

жилище, обиталище

привычный

приучать

обычно

рука; рабочий

handful

горсть

удобный (для использования)

handmade

изготовленный вручную

вручать

счастье

unhappiness

несчастье

счастливый

unhappy

несчастный

счастливо

unhappily

несчастливо

вред

вредный

harmless

безвредный

повредить, навредить

вредно

здоровье

здоровый

unhealthy

нездоровый

дом, жилище

бездомный

честь

почетный

почитать, чтить

почетно

надежда

hopefulness

оптимизм, надежда

надеющийся

hopeless

безнадежный

надеяться

с надеждой

человечество

человеческий

humane

гуманный

inhuman

бесчеловечный

humanitarian

гуманитарный

юмор

юмористический

с юмором

спешка

торопливый, спешащий

hurried

торопливый

торопиться

торопливо

лед

ледяной

важность

важный

unimportant

незначительный

важно

впечатление

впечатленный

impressive

впечатляющий

unimpressed

безучастный

производить впечатление

впечатляюще

улучшение

улучшенный

улучшать

толчок, побуждение

импульсивный

импульсивно

несчастный случай; конфликт, инцидент

случайный

случайно

рост, увеличение

растущий

увеличивать(ся)

с ростом

промышленность

промышленный

industrious

трудолюбивый. усердный

индустриализовать

в промышленном отношении

сообщение, информация

informant

осведомитель

formality

формальность

осведомленный

well-informed

знающий, хорошо информированный

misinformed

неверно информированный

formal

формальный, официальный

informal

неофициальный

информировать

misinform

неверно сообщать; дезинформировать

информационно

интенсивность

интенсивный

интенсифицировать

интенсивно

интерес

заинтересованный

interesting

интересный

интересовать

изобретатель

invention

изобретение

изобретательный

изобретать

изобретательно

приглашение

приглашенный

приглашать

вдохновение

вдохновленный

inspiring

вдохновляющий

вдохновлять

знание

acknowledgement

признание; расписка

признанный

признавать, подтверждать

законность, легальность

юридический, законный

illegal

незаконный, подпольный

легализовать

законно

illegally

незаконно

сходство, подобие

приятный

unlike

непохожий

like

аналогичный

относиться хорошо

dislike

относиться отрицательно

вероятно

unlikely

невероятно

unlike

в отличие

жизнь

living

жизнь

оживленный, веселый

live

актуальный, реальный

жить

оживленно

литература

буквальный

literary

литературный

literate

грамотный

illiterate

неграмотный

буквально

место, поселение

местный

размещать

в определенном месте

одиночество

одинокий; один

удача

удачливый

unlucky

неудачливый, неудачный

к счастью

роскошь

шикарный

большинство

главный, основной

управляющий, руководитель

управленческий

управлять; справляться

женитьба

женатый / замужняя

unmarried

неженатый / незамужняя

жениться

встреча; собрание

встречать, знакомиться

память

memorial

мемориал

памятный

заучивать наизусть

нищета

нищенский, ничтожный

месяц

ежемесячный

ежемесячно

движение

неподвижный

показывать жестом

тайна, загадка

таинственный, загадочный

таинственно, загадочно

необходимость

необходимый

unnecessary

ненужный

необходимо

нерв

нервный

нервировать

нервно

число; количество

многочисленный

numerate

умеющий считать

innumerate

неумеющий считать

обозначать цифрами

объект, предмет

objective

цель; возражение

объективный

возражать

объективно

упрямый

упрямо

случай, происшествие

происходить

операция; оперирование, приведение в действие

управлять, действовать

возможность

opportunist

оппортунист

своевременный, подходящий

оппозиция, противостояние

opponent

оппонент, противник

напротив

opposed

противоположный

противопосталять

владелец, хозяин

собственный

владеть

боль

болезненный

painless

безболезненный

болезненно

painlessly

безболезненно

терпение

impatience

нетерпение

patient

пациент

терпеливый

impatient

нетерпеливый

терпеливо

impatiently

нетерпеливо

участник

participation

участие

участвующий

принимать участие

подробности

особенный

особенно

совершенство

совершенный, идеальный

imperfect

несовершенный

совершенствовать, улучшать

отлично, безупречно

период, срок

периодический

периодически

представление; исполнение

performer

исполнитель

исполнять, выполнять, совершать

мир, спокойствие

мирный

мирно

разрешение

permissiveness

вседозволенность

permit

пропуск

позволяющий

позволять

с позволением

удовольствие

приятный

pleased

довольный

displeased

недовольный

доставлять удовольствие

приятно

точка; пункт

остроконечный, нацеленный

pointful

уместный, удачный

pointless

бесцельный

указывать, направлять

остро, по существу

вежливость

вежливый

impolite

невежливый

вежливо

популярность

популярный

unpopular

непопулярный

популяризировать

владение, собственность

possessor

обладатель, владелец

собственнический

владеть, обладать

вероятность, возможность

возможный

impossible

невозможный

возможно

сила, мощь

мощный

powerless

бессильный

уполномочивать

предпочтение

предпочтительный

preferential

пользующийся препочтением

предпочитать

предпочтительно

подготовка

подготовленный

unprepared

неподготовленный

подготовить

с готовностью

престиж

престижный

престижно

профессия

профессиональный

профессионально

выгода

выгодный

unprofitable

не приносящий выгоды

получать выгоду

выгодно

прогресс, продвижение

прогрессивный

продвигаться вперед

постепенно, продвигаясь вперед

предложение

предложенный

делать предложение

процветание

процветающий

процветать

процветающе

общественность

общественный

разглашать

открыто, публично

быстрота

быстрый

убыстрять

быстро

реальность

realization

реализация, осуществление

реальный, настоящий

unreal

нереальный

реализовать, осуществлять

действительно, в самом деле

признание, узнавание

признанный

узнавать; признавать

снижение, понижение

уменьшенный; сниженный

снижать; сбавлять

отдых, расслабление

расслабленный

relaxing

отдыхающий; расслабляющий

отдыхать, расслабляться

расслабленно

надежность

надежный

unreliable

ненадежный

доверять, полагаться

надежно

религия

религиозный

нежелание, неохота

неохотный

неохотно

регулярность

irregularity

нерегулярность

регулярный, правильный

irregular

неправильный; нестандартный

регулировать

регулярно

замечание

замечательный

замечать, отмечать

замечательно

представление

representative

представитель

представительный

представлять

упрек

безупречный

упрекать

с упреком

репутация

имеющий хорошую репутацию, почтенный

disreputable

имеющий плохую репутацию

давать репутацию

disrepute

компрометироватъ

сопротивление

ударопрочный;

irresistible

неотразимый

resistant

прочный

сопротивляться

неотразимо

уважение

уважительный

уважать

с уважением

отдых

беспокойный

отдыхать

беспокойно

награда

стоящий награды

unrewarded

невознагражденный

награждать

богатства

richness

богатство

богатый

обогащать

богато

риск

рискованный

рисковать

грусть

грустный

огорчать

грустно

сейф

safety

безопасность

безопасный

unsafe

опасный

спасать; экономить

безопасно

удовлетворение

dissatisfaction

неудовлетворенность; недовольство

довольный

dissatisfied

недовольный

satisfactory

удовлетворительный

unsatisfactory

неудовлетворительный

удовлетворять

dissatisfy

разочаровывать; огорчать

исследование

искать, осуществлять поиск

безопасность

безопасный

insecure

находящийся в опасности

охранять, гарантировать

безопасно

серьезность

серьезный

серьезно

наука

scientist

ученый

научный

научно

чувство

insensibility

отсутствие чувствительности

чувствительный

insensitive

несочувствующий

sensible

разумный

insensible

нечувствительный, неосознающий

ощущать

чувствительно

sensibly

разумно

услуга, обслуживание

servant

слуга

обслуженный; поданный на стол

служить, обслуживать, подавать на стол

значительный

insignificant

незначительный

иметь значение

значительно

сходство, похожесть

похожий, подобный

похоже, подобно

искренность

искренний

insincere

неискренний

искренне

шорты

короткий

укорачивать

кратко

сон

sleeper

спящий; спальный вагон

спящий

sleepless

бессонный

спать

без сна

решение; раствор

решенный; растворенный

решать; находить выход; растворять

специальность; фирменное блюдо

specialty

особенность

особенный; специальный

specific

специфический

точно определять

specialize

специализировать(ся)

специально

specifically

специфично

сила

сильный

укреплять

сильно

стресс

стрессовый

ударять, ставить ударение

в состоянии стресса

успех

успешный

unsuccessful

безуспешный

преуспевать

успешно

достаточность

insufñcience

недостаточность

достаточный

insufficient

недостаточный

быть достаточным

достаточно

подходящий

unsuitable

неподходящий

подходить, устраивать

предложение

предлагать

подозреваемый

подозрительный

подозревать

подозрительно

пловец

swimming

плавание

плавающий, плавательный

плавать

сочувствие, понимание

сочувствующий

сочувствовать

с пониманием; сочувственно

уверенность

уверенный

unsure

неуверенный

assured

обеспеченный; уверенный

self-assured

уверенный в себе

обеспечивать; гарантировать

assure

уверять, обеспечивать

конечно; уверенно

assuredly

с уверенностью

окружение

окруженный

окружать

беседа, разговор

разговорчивый

беседовать

вкус

distaste

отсуствие вкуса

сделанный со вкусом; обладающий вкусом

tasteless

безвкусный

пробовать

со вкусом

tastelessly

без вкуса

террор

terrorist

террорист

ужасный

terrific

потрясающий

terrifying

ужасающий

terrified

напуганный

ужасать

ужасно

terrifically

потрясающе

жажда

испытывать жажду

колготки

плотный, тесный

сжимать, натягивать

тесно, плотно

мысль

задумчивый

thoughtless

бездумный

думать, иметь мнение

задумчиво

трагедия

трагичный

tragical

трагический

трагично

путешествие

traveller

путешественник

путешествующий

путешествовать

правда

untruth

неправда

правильный; настоящий

untrue

неверный, не соответствующий действительности

truthful

правдивый

по-настоящему, искренне

truthfully

правдиво

ценность

ценимый

valuable

ценный

ценить, оценивать

разнообразие

variability

изменчивость, непостоянство

изменяемый

invariable

неизменный

менять, разнообразить

неизменно

год

ежегодный

ежегодно

понимание

misunderstanding

непонимание; недоразумение

понятный

понимать

польза

misuse

неправильное использование;

usage

использование

полезный

useless

бесполезный

used

использованный

unused

неиспользованный

использовать, пользоваться

полезно

uselessly

бесполезно

неделя

еженедельный

еженедельно

ширина

широкий

расширять

широко

воля, желание; завещание

жаждущий, желающий

unwilling

не желающий

проявлять волю, желать

охотно, с удовольствием

unwillingly

неохотно

ветер

ветренный

windless

безветренный

мудрость

мудрый

unwise

неблагоразумный

мудро

unwisely

неблагоразумно

стоимость, ценность

достойный

worthless

не имеющий ценности

Modern English Word-Formation

C H A P T E R I

The ways in which new words are

formed, and the factors which govern their acceptance into the language, are

generally taken very much for granted by the average speaker. To understand a

word, it is not necessary to know how it is constructed, whether it is simple

or complex, that is, whether or not it can be broken down into two or more

constituents. We are able to use a word which is new to us when we find out

what object or notion it denotes. Some words, of course, are more ‘transparent’

than others. For example, in the words unfathomable and indescribable

we recognize the familiar pattern of negative prefix + transitive word +

adjective-forming suffix on which many words of similar form are constructed.

Knowing the pattern, we can easily guess their meanings – ‘cannot be fathomed’

and ‘cannot be described’ – although we are not surprised to find other

similar-looking words, for instance unfashionable and unfavourable

for which this analysis will not work. We recognize as ‘transparent’ the

adjectives unassuming and unheard-of, which taking for granted

the fact that we cannot use assuming and heard-of. We accept as

quite natural the fact that although we can use the verbs to pipe, to

drum and to trumpet, we cannot use the verbs to piano

and to violin.

But when we meet new coinages, like tape-code,

freak-out, shutup-ness and beautician, we may not readily

be able to explain our reactions to them. Innovations in vocabulary are capable

of arousing quite strong feelings in people who may otherwise not be in the

habit of thinking very much about language. Quirk[1]

quotes some letter to the press of a familiar kind, written to protest about

‘horrible jargon’, such as breakdown, ‘vile’ words like transportation,

and the ‘atrocity’ lay-by.

Many linguists agree over the fact

that the subject of word-formation has not until recently received very much

attention from descriptive grammarians of English, or from scholars working in

the field of general linguistics. As a collection of different processes

(compounding, affixation, conversion, backformation, etc.) about which, as a

group, it is difficult to make general statements, word-formation usually makes

a brief appearance in one or two chapters of a grammar. Valerie Adams

emphasizes two main reasons why the subject has not been attractive to

linguists: its connections with the non-linguistic world of things and ideas,

for which words provide the names, and its equivocal position as between

descriptive and historical studies. A few brief remarks, which necessarily

present a much over-simplified picture, on the course which linguistics has

taken in the last hundred years will make this easier.

The nineteenth century, the period of

great advances in historical and comparative language study, saw the first

claims of linguistics to be a science, comparable in its methods with the

natural sciences which were also enjoying a period of exciting discovery. These

claims rested on the detailed study, by comparative linguists, of formal

correspondences in the Indo-European languages, and their realization that such

study depended on the assumption of certain natural ‘laws’ of sound change. As

Robins[2] observes in his discussion of the

linguistics of the latter part of the nineteenth century:

The history of a language is traced

through recorded variations in the forms and meanings of its words, and

languages are proved to be related by reason of their possession of worlds

bearing formal and semantic correspondences to each other such as cannot be

attributed to mere chance or to recent borrowing. If sound change were not

regular, if word-forms were subject to random, inexplicable, and unmotivated

variation in the course of time, such arguments would lose their validity and

linguistic relations could only be established historically by extralinguistic

evidence such as is provided in the Romance field of languages descended from

Latin.

The rise and development in the

twentieth century of synchronic descriptive linguistics meant a shift of

emphasis from historical studies, but not from the idea of linguistics as a

science based on detailed observation and the rigorous exclusion of all

explanations depended on extralinguistic factors. As early as 1876, Henry Sweet

had written:

Before history must come a knowledge of what exists.

We must learn to observe things as they are, without regard to their origin,

just as a zoologist must learn to describe accurately a horse or any other

animal. Nor would the mere statements that the modern horse is a descendant of

a three-toed marsh quadruped be accepted as an exhausted description… Such

however is the course being pursued by most antiquarian philologists.[3]

The most influential scholar

concerned with the new linguistics was Ferdinand de Saussure, who emphasized

the distinction between external linguistics – the study of the effects on a

language of the history and culture of its speakers, and internal linguistics –

the study of its system and rules. Language, studied synchronically, as a

system of elements definable in relation to one another, must be seen as a

fixed state of affairs at a particular point of time. It was internal

linguistics, stimulated by de Saussure’s works, that was to be the main concern

of the twentieth-century scholars, and within it there could be no place for

the study of the formation of words, with its close connection with the

external world and its implications of constant change. Any discussion of new

formations as such means the abandonment of the strict distinction between

history and the present moment. As Harris expressed in his influential Structural

Linguistics[4]:

‘The methods of descriptive linguistics cannot treat of the productivity of

elements since that is a measure of the difference between our corpus and some

future corpus of the language.’ Leonard Bloomfield, whose book Language[5]

was the next work of major influence after that of de Saussure, re-emphasized

the necessity of a scientific approach, and the consequent difficulties in the

way of studying ‘meaning’, and until the middle of the nineteen-fifties,

interest was centered on the isolating of minimal segments of speech, the

description of their distribution relative to one another, and their

organization into larger units. The fundamental unit of grammar was not the

word but a smaller unit, the morpheme.

The next major change of emphasis in

linguistics was marked by the publication in 1957 of Noam Chomsky’s Syntactic

Structures[6].

As Chomsky stated it, the aim of linguistics was now seen to be ‘to make

grammatical explanations parallel in achievement to the behavior of the speaker

who, on the basis of a finite and accidental experience with language can

produce and understand an indefinite number of new sentences’[7].

The idea of productivity, or creativity, previously excluded from linguistics,

or discussed in terms of probabilities in the effort to maintain the view of

language as existing in a static state, was seen to be of central importance.

But still word-formation remained a topic neglected by linguists, and for

several good reasons. Chomsky made explicit the distinction, fundamental to

linguistics today (and comparable to that made by de Saussure between langue,

the system of a language, and parole, the set of utterances of the

language), between linguistic competence, ‘the speaker-hearer’s knowledge of

his language’ and performance, ‘the actual use of language in concrete

situations’[8].

Linked with this distinction are the notions of ‘grammaticalness’ and

‘acceptability’; in Chomsky’s words, ‘Acceptability is a concept that belongs

to the study of competence’[9].

A ‘grammatical’ utterance is one which may be generated and interpreted by the

rules of the grammar; an ‘acceptable’ utterance is one which is ‘perfectly

natural and immediately comprehensible… and in no way bizarre or outlandish’[10].

It is easy to show, as Chomsky does, that a grammatical sentence may not be

acceptable. For instance, this is the cheese the rat the cat caught stole

appears ‘bizarre’ and unacceptable because we have difficulty in working it

out, not because it breaks any grammatical rules. Generally, however, it is to

be expected that grammaticalness and acceptability will go hand in hand where

sentences are concerned.

The ability to make and understand

new words is obviously as much a part of our linguistic competence as the

ability to make and understand new sentences, and so, as Pennanen[11]

points out, ‘it is an obvious gap in transformational grammars not to have made

provision for treating word-formation.’ But, as we have already noticed, we may

readily thing of words, like to piano and to violin, against

which we can invoke no rule, but which are definitely ‘unacceptable’ for no

obvious reason. The incongruence of grammaticality and acceptability that is,

is far greater where words are concerned than where sentences are concerned. It

is so great, in fact, that the exercise of setting out the ‘rules’ for forming

words has so far seemed to many linguists to be out of questionable usefulness.

The occasions on which we would have to describe the output of such rules as ‘grammatical

but non-occurring’[12]

are just too numerous. And there are further difficulties in treating new words

like new sentences. A novel word (like handbook or partial) may

attract unwelcome attention to itself and appear to be the result of the breaking

of rules rather than of their application. And besides, the more accustomed to

the word we become, the more likely we are to find it acceptable, whether it is

‘grammatical’ or not – or perhaps we should say, whether or not is was

‘grammatical’ at the time it was first formed, since a new word once

formed, often becomes merely a member of an inventory; its formation is a

historical event, and the ‘rule’ behind it may then appear irrelevant.

What exactly is a word? From Lewis

Carroll onwards, this apparently simple question has bedeviled countless word

buffs, whether they are participating in a game of Scrabble or writing an

article for the Word Ways linguistic magazine. To help the reader decide what

constitutes a word, A. Ross Eckler[13]

suggests a ranking of words in decreasing order of admissibility. A logical way

to rank a word is by the number of English-speaking people who can recognize it

in speech or writing, but this is obviously impossible to ascertain.

Alternatively, one can rank a word by its number of occurrences in a selected

sample of printed material. H. Kucera and W.N. Francis’s Computational

Analysis of Present-day English[14]

is based on one million words from sources in print in 1961. Unfortunately, the

majority of the words in Webster’s Unabridged[15]

do not appear even once in this compilation – and the words which do not appear

are the ones for which a philosophy of ranking is most urgently needed.

Furthermore, the written ranking will differ from the recognition ranking;

vulgarities and obscenities will rank much higher in the latter than in the

former.

A detailed, word-by-word ranking is

an impossible dream, but a ranking based on classes of words may be within our

grasp. Ross Eckler[16]

proposes the following classes: (1) words appearing in one more standard

English-language dictionaries, (2) non-dictionary words appearing in print in

several different contexts, (3) words invented to fill a specific need and

appearing but once in print.

Most people are willing to admit as

words all uncapitalized, unlabeled entries in, say, Webster’s New International

Dictionary, Third Edition (1961). Intuitively, one recognizes that words become

less admissible as they move in any or all of three directions: as they become

more frequently capitalized, as they become the jargon of smaller groups

(dialect, technical, scientific), and as they become archaic or obsolete. These

classes have no definite boundaries – is a word last used in 1499 significantly

more obsolete than a word last used in 1501? Is a word known to 100,000

chemists more admissible than a word known to 90,000 Mexican-Americans? Each

linguist will set his own boundaries.

The second class consists of

non-dictionary words appearing in print in a number of sources. There are many

non-dictionary words in common use; some logologists would like to draw a wider

circle to include these. Such words can be broadly classified into: (1)

neologisms and common words overlooked by dictionary-makers, (2) geographical

place names, (3) given names and surnames.

Dmitri Borgmann[17]

points out that the well-known words uncashed, ex-wife and duty-bound

appear in no dictionaries (since 1965, the first of these has appeared in the

Random House Unabridged). Few people would exclude these words. Neologisms

present a more awkward problem since some may be so ephemeral that they never

appear in a dictionary. Perhaps one should read Pope’s dictum «Be not the

first by whom the new are tried, nor yet the last to lay the old aside.»

Large treasure-troves of geographic

place names can be found in The Times Atlas of the World[18]

(200,000 names), and the Rand McNally Commercial Atlas and Marketing Guide[19]

(100,000 names). These are not all different, and some place names are already

dictionary words. All these can be easily verified by other readers; however,

some will feel uneasy about admitting as a word the name, say, of a small

Albanian town which possibly has never appeared in any English-language text

outside of atlases.

Given names appear in the appendix of

many dictionaries. Common given names such as Edward or Cornelia ought to be

admitted as readily as common geographical place names such as Guatemala, but

this set does not add much to the logological stockpile.

Family surnames at first blush appear

to be on the same footing as geographical place names. However, one must be

careful about sources. Biographical dictionaries and Who’s Who are adequate

references, but one should be cautious citing surnames appearing only in

telephone directories. Once a telephone directory is supplanted by a later

edition, it is difficult to locate copies for verifying surname claims.

Further, telephone directories are not immune to nonce names coined by

subscribers for personal reasons. A good index of the relative admissibility of

surnames is the number of people in the United States bearing that surname. An

estimate of this could be obtained from computer tapes of the Social Security

Administration; in 1957 they issued a pamphlet giving the number of Social

Security accounts associated with each of the 1500 most common family names.

The third and final class of words

consists of nonce words, those invented to fill a specific need, and appearing

only once (or perhaps only in the work of the author favoring the word). Few

philologists feel comfortable about admitting these. Nonce words range from

coinages by James Joyce and Edgar Allan Poe (X-ing a Paragraph) to

interjections in comic strips (Agggh! Yowie!). Ross Eckler and Daria

Abrossimova suggest that misspellings in print should be included here also.

In the book “Beyond Language”, Dmitri

Borgmann proposes that the philologist be prepared to admit words that may

never have appeared in print. For example, Webster’s Second lists eudaemony as

well as the entry «Eudaimonia, eudaimonism, eudaimonist, etc.» From

this he concludes that EUDAIMONY must exist and should be admitted as a word.

Similarly, he can conceive of sentences containing the word GRACIOUSLY’S («There are ten graciously’s in

Anna Karenina») and SAN DIEGOS («Consider the luster that the San Diegos of our

nation have brought to the US»). In short, he argues that these words

might plausibly be used in an English-language sentence, but does not assert

any actual usage. His criterion for the acceptance of a word seems to be its

philological uniqueness (EUDAIMONY is a short word containing all five vowels and Y).

The available linguistic literature

on the subject cites various types and ways of forming words. Earlier books,

articles and monographs on word-formation and vocabulary growth in general used

to mention morphological, syntactic and lexico-semantic types of

word-formation. At present the classifications of the types of word-formation

do not, as a rule, include lexico-semantic word-building. Of interest is the

classification of word-formation means based on the number of motivating bases

which many scholars follow. A distinction is made between two large classes of

word-building means: to Class I belong the means of building words having one

motivating base (e.g. the noun doer is composed of the base do-

and the suffix —er), which Class II includes the means of building words

containing more than one motivating base. They are all based on compounding

(e.g. compounds letter-opener, e-mail, looking-glass).

Most linguists in special chapters and manuals devoted to

English word-formation consider as the chief processes of English

word-formation affixation, conversion and compounding.

Apart from these, there is a number

of minor ways of forming words such as back-formation, sound interchange,

distinctive stress, onomatopoeia, blending, clipping, acronymy.

Some of the ways of forming words in

present-day English can be restored to for the creation of new words whenever

the occasion demands – these are called productive ways of forming words,

other ways of forming words cannot now produce new words, and these are

commonly termed non—productive or unproductive. R. S.

Ginzburg gives the example of affixation having been a productive way of

forming new words ever since the Old English period; on the other hand,

sound-interchange must have been at one time a word-building means but in

Modern English (as we have mentioned above) its function is actually only to

distinguish between different classes and forms of words.

It follows that productivity of

word-building ways, individual derivational patterns and derivational affixes

is understood as their ability of making new words which all who speak English

find no difficulty in understanding, in particular their ability to create what

are called occasional words or nonce-words[20]

(e.g. lungful (of smoke), Dickensish (office), collarless

(appearance)). The term suggests that a speaker coins such words when he needs

them; if on another occasion the same word is needed again, he coins it afresh.

Nonce-words are built from familiar language material after familiar patterns.

Dictionaries, as a rule, do not list occasional words.

The delimitation between productive

and non-productive ways and means of word-formation as stated above is not,

however, accepted by all linguists without reserve. Some linguists consider it

necessary to define the term productivity of a word-building means more

accurately. They hold the view that productive ways and means of word-formation

are only those that can be used for the formation of an unlimited number of new

words in the modern language, i.e. such means that “know no bounds” and easily

form occasional words. This divergence of opinion is responsible for the

difference in the lists of derivational affixes considered productive in

various books on English lexicology.

Nevertheless, recent investigations

seem to prove that productivity of derivational means is relative in many

respects. Moreover there are no absolutely productive means; derivational

patterns and derivational affixes possess different degrees of productivity.

Therefore it is important that conditions favouring productivity and the degree

if productivity of a particular pattern or affix should be established. All

derivational patterns experience both structural and semantic constraints. The

fewer are the constraints, the higher is the degree of productivity, the

greater is the number of new words built on it. The two general constraints

imposed on all derivational patterns are: the part of speech in which the

pattern functions and the meaning attached to it which conveys the regular

semantic correlation between the two classes of words. It follows that each

part of speech is characterized by a set of productive derivational patterns

peculiar to it. Three degrees of productivity are distinguished for

derivational patterns and individual derivational affixes: (1) highly

productive, (2) productive or semi-productive and (3) non-productive.

R. S. Ginzburg[21]

says that productivity of derivational patterns and affixes should not be

identified with the frequency of occurrence in speech, although there may be

some interrelation between then. Frequency of occurrence is characterized by

the fact that a great number of words containing a given derivational affix are

often used in speech, in particular in various texts. Productivity is

characterized by the ability of a given suffix to make new words.

In linguistic literature there is

another interpretation of derivational productivity based on a quantitative

approach. A derivational pattern or a derivational affix are qualified as

productive provided there are in the word-stock dozens and hundreds of derived

words built on the pattern or with the help of the suffix in question. Thus

interpreted, derivational productivity is distinguished from word-formation

activity by which is meant the ability of an affix to produce new words, in

particular occasional words or nonce-words. For instance, the agent suffix –er

is to be qualified both as a productive and as an active suffix: on the one hand,

the English word-stock possesses hundreds of nouns containing this suffix (e.g.

writer, reaper, lover, runner, etc.), on the other hand, the suffix –er

in the pattern v + –er à N is freely used to coin an unlimited number

of nonce-words denoting active agents (e.g. interrupter, respecter, laugher,

breakfaster, etc.).

The adjective suffix –ful is

described as a productive but not as an active one, for there are hundreds of

adjectives with this suffix (e.g. beautiful, hopeful, useful, etc.), but

no new words seem to be built with its help.

For obvious reasons, the noun-suffix –th in terms of

this approach is to be regarded both as a non-productive and a non-active one.

Now let us consider the basic ways of

forming words in the English language.

Affixation is generally defined as the

formation of words by adding derivational affixes to different types of bases.

Derived words formed by affixation may be the result of one or several

applications of word-formation rule and thus the stems of words making up a

word-cluster enter into derivational relations of different degrees. The zero

degree of derivation is ascribed to simple words, i.e. words whose stem is

homonymous with a word-form and often with a root-morpheme (e.g. atom,

haste, devote, anxious, horror, etc.). Derived words whose bases are built

on simple stems and thus are formed by the application of one derivational

affix are described as having the first degree of derivation (e.g. atomic,

hasty, devotion, etc.). Derived words formed by two consecutive stages of

coining possess the second degree of derivation (e.g. atomical, hastily,

devotional, etc.), and so forth.

In conformity with the division of

derivational affixes into suffixes and prefixes affixation is subdivided into suffixation

and prefixation. Distinction is naturally made between prefixal and

suffixal derivatives according to the last stage of derivation, which

determines the nature of the immediate constituents of the pattern that signals

the relationship of the derived word with its motivating source unit, e.g. unjust

(un– + just), justify (just + –ify), arrangement

(arrange + –ment), non-smoker (non– + smoker). Words like reappearance,

unreasonable, denationalize, are often qualified as prefixal-suffixal

derivatives. R. S. Ginzburg[22]

insists that this classification is relevant only in terms of the constituent

morphemes such words are made up of, i.e. from the angle of morphemic analysis.

From the point of view of derivational analysis, such words are mostly either

suffixal or prefixal derivatives, e.g. sub-atomic = sub– + (atom

+ –ic), unreasonable = un– + (reason + –able), denationalize = de– +

(national + –ize), discouragement = (dis– + courage) + –ment.

A careful study of a great many

suffixal and prefixal derivatives has revealed an essential difference between

them. In Modern English, suffixation is mostly characteristic of noun and

adjective formation, while prefixation is mostly typical of verb formation. The

distinction also rests on the role different types of meaning play in the

semantic structure of the suffix and the prefix. The part-of-speech meaning has

a much greater significance in suffixes as compared to prefixes which possess

it in a lesser degree. Due to it, a prefix may be confined to one part of

speech as, for example, enslave, encage, unbutton, or may function in

more that one part of speech as over– in overkind, overfeed,

overestimation. Unlike prefixes, suffixes as a rule function in any one

part of speech often forming a derived stem of a different part of speech as

compared with that of the base, e.g. careless – care; suitable – suit,

etc. Furthermore, it is necessary to point out that a suffix closely knit

together with a base forms a fusion retaining less of its independence that a

prefix which is as a general rule more independent semantically, e.g. reading

– ‘the act of one who reads’; ‘ability to read’; and to re-read – ‘to read

again’.

Prefixation is the formation of words with the

help of prefixes. The interpretation of the terms prefix and prefixation now firmly

rooted in linguistic literature has undergone a certain evolution. For

instance, some time ago there were linguists who treated prefixation as part of

word-composition (or compounding). The greater semantic independence of

prefixes as compared with suffixes led the linguists to identify prefixes with

the first component part of a compound word.

At present the majority of scholars

treat prefixation as an integral part of word-derivation regarding prefixes as

derivational affixes which differ essentially both from root-morphemes and

non-derivational prepositive morphemes. Opinion sometimes differs concerning

the interpretation of the functional status of certain individual groups of

morphemes which commonly occur as first component parts of words. H. Marchand[23],

for instance, analyses words like to overdo, to underestimate as

compound verbs, the first component of which are locative particles, not

prefixes. In a similar way he interprets words like income, onlooker,

outhouse qualifying them as compounds with locative particles as first

elements.

R. S. Ginzburg[24]

states there are about 51 prefixes in the system of Modern English

word-formation.

Unlike suffixation, which is usually more closely bound

up with the paradigm of a certain part of speech, prefixation is considered to

be more neutral in this respect. It is significant that in linguistic

literature derivational suffixes are always divided into noun-forming,

adjective-forming and so on; prefixes, however, are treated differently. They

are described either in alphabetical order or sub-divided into several classes

in accordance with their origin,. Meaning or function and never according to

the part of speech.

Prefixes may be classified on

different principles. Diachronically distinction is made between prefixes of

native and foreign origin. Synchronically prefixes may be classified:

(1) According to the class of words they

preferably form. Recent investigations allow one to classify prefixes according

to this principle. It must be noted that most of the 51 prefixes of Modern

English function in more than one part of speech forming different structural

and structural-semantic patterns. A small group of 5 prefixes may be referred

to exclusively verb-forming (en–, be–, un–, etc.).

(2) As to the type of lexical-grammatical

character of the base they are added to into: (a) deverbal, e.g. rewrite,

outstay, overdo, etc.; (b) denominal, e.g. unbutton, detrain,

ex-president, etc. and (c) deadjectival, e.g. uneasy, biannual, etc.

It is interesting that the most productive prefixal pattern for adjectives is

the one made up of the prefix un– and the base built either on

adjectival stems or present and past participle, e.g. unknown, unsmiling,

untold, etc.

(3) Semantically prefixes fall into mono–

and polysemantic.

(4) As to the generic denotational

meaning there are different groups that are distinguished in linguistic

literature: (a) negative prefixes such as un–, non–, in–, dis–, a–,

im–/in–/ir– (e.g. employment à unemployment, politician à non-politician, correct à incorrect, advantage à disadvantage, moral à amoral, legal à illegal, etc.); (b) reversative of privative

prefixes, such as un–, de–, dis–, dis– (e.g. tie à untie, centralize à decentralize, connect à disconnect, etc.); (c) pejorative prefixes,

such as mis–, mal–, pseudo– (e.g. calculate à miscalculate, function à malfunction, scientific à pseudo-scientific, etc.); (d) prefixes of time and

order, such as fore–, pre–, post–, ex– (e.g. see à foresee, war à pre-war, Soviet à post-Soviet, wife à ex-wife, etc.); (e) prefix of repetition re–

(e.g. do à redo, type à retype, etc.); (f) locative prefixes such

as super–, sub–, inter–, trans– (e.g. market à supermarket, culture à subculture, national à international, Atlantic à trans-Atlantic, etc.).

(5) When viewed from the angle of their

stylistic reference, English prefixes fall into those characterized by neutral

stylistic reference and those possessing quite a definite stylistic

value. As no exhaustive lexico-stylistic classification of English prefixes

has yet been suggested, a few examples can only be adduced here. There is no

doubt, for instance, that prefixes like un–, out–, over–, re–, under–

and some others can be qualified as neutral (e. g. unnatural, unlace,

outgrow, override, redo, underestimate, etc.). On the other hand, one can

hardly fail to perceive the literary-bookish character of such prefixes as pseudo–,

super–, ultra–, uni–, bi– and some others (e. g. pseudo-classical,

superstructure, ultra-violence, unilateral, bifocal, etc.).

Sometimes one

comes across pairs of prefixes one of which is neutral, the other is

stylistically coloured. One example will suffice here: the prefix over–

occurs in all functional styles, the prefix super– is peculiar to

the style of scientific prose.

(6) Prefixes may be also

classified as to the degree of productivity into highly-productive,

productive and non-productive.

Suffixation is the formation of

words with the help of suffixes. Suffixes usually modify the lexical meaning

of the base and transfer words to a different part of speech. There are

suffixes however, which do not shift words from one part of speech into

another; a suffix of this kind usually transfers a word into a different

semantic group, e. g. a concrete noun becomes an abstract one, as is the case

with child—childhood, friend—friendship, etc.

Chains of suffixes

occurring in derived words having two and more suffixal morphemes are sometimes

referred to in lexicography as compound suffixes: –ably = –able + –ly

(e. g. profitably, unreasonably) –ical–ly = –ic + –al + –ly

(e. g. musically, critically); –ation = –ate + –ion (e. g.

fascination, isolation) and some others. Compound suffixes do not

always present a mere succession of two or more suffixes arising out of several

consecutive stages of derivation. Some of them acquire a new quality operating

as a whole unit. Let us examine from this point of view the suffix –ation

in words like fascination, translation, adaptation and the like. Adaptation

looks at first sight like a parallel to fascination, translation.

The latter however are first-degree derivatives built with the suffix –ion

on the bases fascinate–, translate–. But there is no base adaptate–,

only the shorter base adapt–. Likewise damnation,

condemnation, formation, information and many others

are not matched by shorter bases ending in –ate, but only by still

shorter ones damn–, condemn–, form–, inform–. Thus, the suffix –ation

is a specific suffix of a composite nature. It consists of two suffixes –ate

and –ion, but in many cases functions as a single unit in first-degree

derivatives. It is referred to in linguistic literature as a coalescent suffix

or a group suffix. Adaptation is then a derivative of the first

degree of derivation built with the coalescent suffix on the base adapt–.

Of interest is also the

group-suffix –manship consisting of the suffixes –man and

–ship. It denotes a superior quality, ability of doing something

to perfection, e. g. authormanship, quotemanship, lipmanship, etc.

It also seems appropriate

to make several remarks about the morphological changes that sometimes

accompany the process of combining derivational morphemes with bases. Although

this problem has been so far insufficiently investigated, some observations

have been made and some data collected. For instance, the noun-forming suffix –ess

for names of female beings brings about a certain change in the phonetic shape

of the correlative male noun provided the latter ends in –er, –or, e.g.

actress (actor), sculptress (sculptor), tigress (tiger), etc. It may be

easily observed that in such cases the sound [∂] is contracted in

the feminine nouns.

Further, there are

suffixes due to which the primary stress is shifted to the syllable immediately

preceding them, e.g. courageous (courage), stability (stable), investigation

(investigate), peculiarity (peculiar), etc. When added to a base

having the suffix –able/–ible as its component, the suffix –ity

brings about a change in its phonetic shape, namely the vowel [i] is

inserted between [b] and [l], e. g. possible à possibility, changeable

à changeability, etc. Some suffixes attract the primary stress on

to themselves, there is a secondary stress on the first syllable in words with

such suffixes, e. g. ’employ’ee (em’ploy), govern’mental (govern),

‘pictu’resque (picture).

There are different

classifications of suffixes in linguistic literature, as suffixes may be

divided into several groups according to different principles:

(1) The first principle of

classification that, one might say, suggests itself is the part of speech

formed. Within the scope of the part-of-speech classification suffixes

naturally fall into several groups such as:

a)

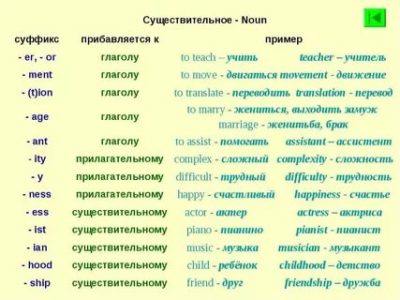

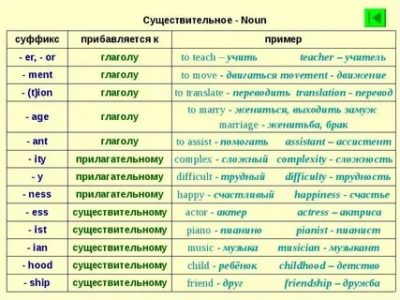

noun-suffixes,

i.e. those forming or occurring in nouns, e. g. –er, –dom, –ness, –ation, etc.

(teacher, Londoner, freedom, brightness, justification, etc.);

b) adjective-suffixes, i.e.

those forming or occurring in adjectives, e. g. –able, –less, –ful, –ic,

–ous, etc. (agreeable, careless, doubtful, poetic, courageous, etc.);

c) verb-suffixes, i.e. those

forming or occurring in verbs, e. g. –en, –fy, –ize (darken, satisfy,

harmonize, etc.);

d) adverb-suffixes, i.e.

those forming or occurring in adverbs, e. g. –ly, –ward (quickly, eastward,

etc.).

(2) Suffixes may also be

classified into various groups according to the lexico-grammatical character of

the base the affix is usually added to. Proceeding from this principle one may

divide suffixes into:

a)

deverbal

suffixes (those added to the verbal base), e. g. –er, –ing, –ment, –able, etc.

(speaker, reading, agreement, suitable, etc.);

b) denominal suffixes (those

added to the noun base), e. g. –less, –ish, –ful, –ist, –some, etc.

(handless, childish, mouthful, violinist, troublesome, etc.);

c) de-adjectival suffixes

(those affixed to the adjective base), e. g. –en, –ly, –ish, –ness, etc.

(blacken, slowly, reddish, brightness, etc.).

(3) A classification of

suffixes may also be based on the criterion of sense expressed by a set of

suffixes. Proceeding from this principle suffixes are classified into various

groups within the bounds of a certain part of speech. For instance, noun-suffixes

fall into those denoting:

a)

the

agent of an action, e. g. –er, –ant (baker, dancer, defendant, etc.);

b) appurtenance, e. g. –an,

–ian, –ese, etc. (Arabian, Elizabethan, Russian, Chinese,

Japanese, etc.);

c) collectivity, e. g. –age,

–dom, –ery (–ry), etc. (freightage, officialdom, peasantry,

etc.);

d) diminutiveness, e. g. –ie,

–let, –ling, etc. (birdie, girlie, cloudlet, squirreling,

wolfing, etc.).

(4) Still another

classification of suffixes may be worked out if one examines them from the

angle of stylistic reference. Just like prefixes, suffixes are also

characterized by quite a definite stylistic reference falling into two basic

classes:

a)

those

characterized by neutral stylistic reference such as –able, –er, –ing,

etc.;

Suffixes with

neutral stylistic reference may occur in words of different lexico-stylistic

layers. As for suffixes of the second class they are restricted in use to quite

definite lexico-stylistic layers of words, in particular to terms, e.g. rhomboid,

asteroid, cruciform, cyclotron, synchrophasotron, etc.

(5) Suffixes are also

classified as to the degree of their productivity.

Distinction is usually

made between dead and living affixes. Dead affixes are described as those which are no longer felt in

Modern English as component parts of words; they have so fused with the base of

the word as to lose their independence completely. It is only by special

etymological analysis that they may be singled out, e. g. –d in dead,

seed, –le, –l, –el in bundle, sail, hovel; –ock in hillock; –lock

in wedlock; –t in flight, gift, height. It is quite

clear that dead suffixes are irrelevant to present-day English word-formation,

they belong in its diachronic study.

Living

affixes may be easily singled out from a word, e. g. the noun-forming suffixes –ness,

–dom, –hood, –age, –ance, as in darkness, freedom, childhood,

marriage, assistance, etc. or the adjective-forming suffixes –en, –ous,

–ive, –ful, –y as in wooden, poisonous, active, hopeful, stony, etc.

However, not

all living derivational affixes of Modern English possess the ability to coin

new words. Some of them may be employed to coin new words on the spur of the

moment, others cannot, so that they are different from the point of view of

their productivity. Accordingly they fall into two basic classes — productive

and non-productive word-building affixes.

It has been

pointed out that linguists disagree as to what is meant by the productivity of

derivational affixes.

Following the

first approach all living affixes should be considered productive in varying

degrees from highly-productive (e. g. –er, –ish, –less, re–, etc.)

to non-productive (e. g. –ard, –cy, –ive, etc.).

Consequently

it becomes important to describe the constraints imposed on and the factors

favouring the productivity of affixational patterns and individual affixes. The

degree of productivity of affixational patterns very much depends on the

structural, lexico-grammatical and semantic nature of bases and the meaning of

the affix. For instance, the analysis of the bases from which the suffix –ize

can derive verbs reveals that it is most productive with noun-stems,

adjective-stems also favour ifs productivity, whereas verb-stems and

adverb-stems do not, e. g. criticize (critic), organize (organ), itemize

(item), mobilize (mobile), localize (local), etc. Comparison of the

semantic structure of a verb in –ize with that of the base it is built

on shows that the number of meanings of the stem usually exceeds that of the

verb and that its basic meaning favours the productivity of the suffix –ize

to a greater degree than its marginal meanings, e. g. to characterize —

character, to moralize — moral, to dramatize — drama, etc.

The treatment

of certain affixes as non-productive naturally also depends on the concept of

productivity. The current definition of non-productive derivational affixes as

those which cannot hg used in Modern English for the coining of new words is

rather vague and maybe interpreted in different ways. Following the definition

the term non-productive refers only to the affixes unlikely to be used for the

formation of new words, e. g. –ous, –th, fore– and some others (famous,

depth, foresee).

If one

accepts the other concept of productivity mentioned above, then non-productive

affixes must be defined as those that cannot be used for the formation of

occasional words and, consequently, such affixes as –dom, –ship, –ful, –en,

–ify, –ate and many others are to be regarded as non-productive.

The theory of

relative productivity of derivational affixes is also corroborated by some

other observations made on English word-formation. For instance, different

productive affixes are found in different periods of the history of the

language. It is extremely significant, for example, that out of the seven

verb-forming suffixes of the Old English period only one has survived up to the

present time with a very low degree of productivity, namely the suffix –en

(e. g. to soften, to darken, to whiten).

A derivational

affix may become productive in just one meaning because that meaning is

specially needed by the community at a particular phase in its history. This

may be well illustrated by the prefix de– in the sense of ‘undo what has

been done, reverse an action or process’, e. g. deacidify (paint spray),

decasualize (dock labour), decentralize (government or management), deration

(eggs and butter), de-reserve (medical students), desegregate (coloured

children), and so on.

Furthermore,

there are cases when a derivational affix being nonproductive in the

non-specialized section of the vocabulary is used to coin scientific or

technical terms. This is the case, for instance, with the suffix –ance

which has been used to form some terms in Electrical Engineering, e. g. capacitance,

impedance, reactance. The same is true of the suffix –ity

which has been used to form terms in physics, and chemistry such as alkalinity,

luminosity, emissivity and some others.

Conversion, one of the principal

ways of forming words in Modern English is highly productive in replenishing

the English word-stock with new words. The term conversion, which some

linguists find inadequate, refers to the numerous cases of phonetic identity

of word-forms, primarily the so-called initial forms, of two words belonging to

different parts of speech. This may be illustrated by the following cases: work

— to work; love — to love; paper — to paper; brief — to brief, etc. As

a rule we deal with simple words, although there are a few exceptions, e.g. wireless

— to wireless.

It will be

recalled that, although inflectional categories have been greatly reduced in

English in the last eight or nine centuries, there is a certain difference on

the morphological level between various parts of speech, primarily between

nouns and verbs. For instance, there is a clear-cut difference in Modern

English between the noun doctor and the verb to doctor —

each exists in the language as a unity of its word-forms and variants, not as

one form doctor. It is true that some of the forms are identical

in sound, i.e. homonymous, but there is a great distinction between them, as

they are both grammatically and semantically different.

If we regard

such word-pairs as doctor — to doctor, water — to water, brief — to brief

from the angle of their morphemic structure, we see that they are all

root-words. On the derivational level, however, one of them should be referred

to derived words, as it belongs to a different part of speech and is understood

through semantic and structural relations with the other, i.e. is motivated by

it. Consequently, the question arises: what serves as a word-building means in

these cases? It would appear that the noun is formed from the verb (or vice

versa) without any morphological change, but if we probe deeper into the

matter, we inevitably come to the conclusion that the two words differ in the

paradigm. Thus it is the paradigm that is used as a word-building means. Hence,

we may define conversion as the formation of a new word through changes in its

paradigm.

It is

necessary to call attention to the fact that the paradigm plays a significant

role in the process of word-formation in general and not only in the case of

conversion. Thus, the noun cooker (in gas-cooker) is formed from

the word to cook not only by the addition of the suffix –er, but also by

the change in its paradigm. However, in this case, the role played by the

paradigm as a word-building means is less obvious, as the word-building suffix

–er comes to the fore. Therefore, conversion is characterized not simply