Word formation and parts of speech in Spanish — Wortbildung und Wortarten im Spanischen

The formation of words in Spanish , formación de palabras, is the subject of linguistic morphology , morfología lingüística . Word formation is a linguistic process with which new, complex words ( lexemes ) are generated on the basis of existing linguistic means. These linguistic means can be simple and complex words, morphemes and affixes .

A part of speech or class of speech , categoría morfosintáctica as a lexical category, is understood to be the class of words in a language based on their assignment according to common grammatical features.

Wortbildung, word formation

Word formation is one of the essential forms of vocabulary expansion , alongside a change in meaning , cambio léxico-semántico and borrowing , préstamo lingüístico . [1] As such, it is a matter of lexical innovation processes . [2]

At any time, in any epoch and in a constantly changing environment and environment, people are called upon to react to the fact of missing words or linguistic means of expression by continuously expanding their vocabulary , procesos de formación de palabras . [3] For the production of new words from existing words, i.e. the word formation , formación de palabras , two variants are distinguished:

- Wortableitung ( Derivation , derivation );

- Word composition ( composition , composición ) and

- Parasynthese, parasíntesis . [4]

Derivation is characterized by the fact that a lexeme with one or more affixes [5] is combined on a morphological level to form a new unit of the Spanish vocabulary. [6] When composing, a new word is formed by combining at least two existing words (or word stems ). [7]

-

With the word derivation or derivation, derivación , a base lexem , base lexemática, is combined with only one or several affixes to form a new word.

- Derivation = Basislexem + Affix

Therefore, depending on their position in relation to the basic complex , affixes, afijos can be divided into:

-

- Prefixes , prefijos before the base lexeme: im — pur o, im — posible ;

- Infixes , infijos or Inter Fixed midst of Basislexems: buen — ec -ito

- Suffixes , sufijos nach dem Basislexem: internacio- al

There is also the option of combining several affixes for word formation: des — nacion — al — izar . [8th]

-

In the case of composition, composición , two and possibly several autonomous lexemes are combined to form a new word. [9]

- Composition = Lexem + Lexem + (n-Lexeme)

In Spanish there are various word combinations:

- Verb und Substantiv , verb + noun : corkscrew , can-opener , water-parties .

- Substantiv und Adjektiv, noun + adjective : water-sea , field-holy , paso-doble , hair-red , mouth-open , sweet -full .

- Adjektiv und Substantiv, adjective + noun : extreme-anointing . midnight , safe-conduit , low-relief .

- Substantiv und Substantiv, noun + noun : mouth-street , coli-flower , base salary , home , motorcycle-car , werewolf , Spanish-speaker.

- Adjektiv und Adjektiv, adjective + adjective : deaf-mute , green-blue , sour-sweet , high -low.

- Adverb and adjective, adverbio + adjetivo : biem-pensante .

- Substantiv und Verb, noun + verb : makes it hurt.

- Pronoun und Verb, pronoun + verb : who-wants , what-to-do , who-wants.

- Verb und Verb, verb + verb : sleep-candle. [10]

Another form of «new word formation» is the expansion of meaning . [11] Thus, the speakers of a language community to the needs of an ever-changing environment, by changing the meaning or by the change of meaning react by existing in their language words with their meanings extension. For example, the word «pantalla» [12] [13] has the original meaning of a » screen » or protection as an object. With the demands, its meaning later expanded to “cinema screen”, “screen” or “display”.

Another way of forming new words is nominalization and its opposite, denominalization .

In the area of loan words or borrowing , préstamo lingüístico , for example in the terminology of electronic data processing , the English language shows a great influence . The Internet vocabulary in Spanish in particular has a high number of Anglicisms or Anglo-American word creations. [14]

Not to go unmentioned: [15] [16] [17]

- the apheresis , aféresis , the repayment of speech sounds at the letters. — Example: bus for autobus .

- the Apokopierung , Apocope , the loss of speech sounds at the end of a word. — Example: cine for cinema .

- the contraction , contracción , the contraction of speech sounds in the word. — Example: docudrama from documento and drama .

- the epenthesis , epéntesis , the addition of a speech sound to facilitate pronunciation. — Example: toballa for toalla .

Wortarten, morphosyntactic categories

The part of speech theory tries to classify the lexical- grammatical units of a language. The part of speech must be distinguished from the syntactic function (sentence function) of a word such as subject , object , adverbial , attribute , etc.

Words can be classified according to their meaning ( semantic ), according to their form ( morphological ) or according to their use in the sentence ( syntactic ). The parts of speech in Spanish can be divided into lexical and grammatical words, like content words and functional words .

Both classes contain inflected , conjugable and immutable words: [18] [19] [20]

| Meaning, function ↓ | Forms, classes | |

|---|---|---|

| flexible | flexionslos | |

| Lexical | Substantiv , noun | Zahlwort , numeral name [21] |

| Lexical | Adjective , adjective | Adjective , adverb |

| Lexical | Verb , verb | Partikel , grammatical particle

Interjection , interjección [22] |

| Grammatical | Artikel , article | Präposition , preposition |

| Grammatical | Pronomen , pronoun | Konjunktion , conjunction |

Classifications

A word can be examined from different perspectives or scientific approaches, as follows:

- phonological criteria, criterio fonológico .

- morphological criteria, criterio morfológico .

- functional criteria, criterio funcional .

- semantic criteria, criterio semántico .

A word , palabra , is morphologically composed of meaningful units, the morphemes , morfemas . Two classes can be constructed semantically and functionally for these morphemes:

- the lexical morphemes ( lexemes ), morfemas léxicos and

- the grammatical morphemes, morfemas gramaticales .

To put it simply, one can say: Lexemes (lexical content morphemes ) describe or preferably verbalize facts , things , actions , properties . Grammatical morphemes (grammatical function morphemes ), on the other hand, show the relationships between these facts and circumstances; they also give expression to more abstract categories of meaning, such as gender , number , tense .

Words either have a more lexical or grammatical meaning. With the lexical word classes of the speech producer taught in a text or spoken word , the semantic main information to the receiver, however, are the grammatical word classes or units more function symbols. The group of grammatical units, which also includes inflectional morphemes , functional words (such as structural verbs ), affixes , etc., is much more limited in number than the lexical word units.

literature

- Helmut Berschin , Julio Fernández-Sevilla, Josef Felixberger: The Spanish language. Distribution, history, structure. 3. Edition. Georg Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2005, ISBN 3-487-12814-4

- Franz Rainer: Spanish word formation theory. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1984, ISBN 3-484-50337-8

Weblinks

- Ursula Reutner: Marking information in Spanish lexicons. The example of euphemisms. Romance Linguistics, University of Augsburg, pp. 1–15 — Romance Studies in Past and Present 14.2 (2008), Helmut Buske Verlag, Hamburg [2]

Individual evidence

- ↑ Another, rather rare method of word formation is the new or original creation (cf. Wolfgang Fleischer, Irmhild Barz, with the collaboration of Marianne Schröder: Word formation of the German contemporary language. 2nd, revised and supplemented edition. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1995, ISBN 3- 484-10682-4 , p. 5f., Johannes Erben: Introduction to German Word Formation. 3rd revised edition, Schmidt, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-503-03038-7 , p. 18f.).

- ^ Paul Gévaudan: Typology of lexical change. Change of meaning, word formation and borrowing using the example of the Romance languages. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-86057-173-6 , pp. 34f., 42-44. Another form of change is lexical depletion.

- ↑ Martin Becker: The development of modern word formation in Spanish: The political-social vocabulary since 1869. Bonn Romanistic works, Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-631-51011-X .

- ↑ Kim Vermeersch: The desubstantivic ‘ornative’ verbs in German and Spanish: A chapter from the word formation considered in contrast. Universiteit Gent, 2011/2012 [1]

- ↑ Spelling rules. Prefixes and suffixes.

- ^ Justo Fernández López: Wortbildung. Word formation. hispanoteca.org

- ↑ Antoon van Bommel, Kees van Esch, Jos Hallebeek: Estudiando español, Grundgrammatik. Ernst Klett Sprachen, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-12-535499-9 , S. 178 f.

- ↑ Juan Antonio Marín Candón: Prefix- suffix. Orthography rules.

- ↑ Wolf Dietrich, Horst Geckeler: Introduction to Spanish Linguistics. (= Basics of Romance Studies. Volume 15). Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-503-06188-6 , pp. 88-99.

- ↑ Mervyn F. Lang: Spanish word formation: productive derivative morphology in the modern lexicon. Ed. Cátedra, Madrid 1990, ISBN 84-376-1145-8 .

- ^ Rainer Walter: Spanish word formation theory. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-11-095605-5 .

- ↑ Dictionary of the Spanish language. Royal Spanish Academy

- ↑ The word originally comes from the Catalan «pàmpol» where it means «vine leaf», «lampshade» and is related to the Latin word «pampinus» for vine leaf pampinus

- ↑ Martina Rüdel-Hahn: Anglicisms in the Internet vocabulary of the Romance languages: French — Italian — Spanish. Dissertation . Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf 2008.

- ^ Paul Gévaudan: Classification of Lexical Developments. Semantic, morphological and stratic filiation. ( Memento from June 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Dissertation. University of Tübingen, Tübingen 2002, p. 150 f.

- ↑ Justo Fernández López: Apokope, Epenthese, Zusammenziehung — Apocope, epenthesis and contraction. hispanoteca.eu

- ^ Bernhard Pöll: Spanish Lexicology. An introduction. Gunter Narr Verlag, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-8233-4993-7 , p. 36.

- ^ Table based on Helmut Berschin, Julio Fernández-Sevilla, Josef Felixberger: The Spanish language. Distribution, history, structure. 3. Edition. Georg Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2005, ISBN 3-487-12814-4 , p. 161.

- ^ Modified from Helmut Berschin, Julio Fernández-Sevilla, Josef Felixberger: The Spanish language. Distribution, history, structure. 3. Edition. Georg Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2005, ISBN 3-487-12814-4 , p. 161.

- ↑ The Die Wortgrammatik , Canoonet

- ↑ Numerals, nombres numerales can be inflected to a limited extent .

- ↑ Interjections, interjecciónes and particles, partícula gramatical also have a grammatical function as structural elements in the sentence

The formation of words in Spanish , formación de palabras, is the subject of linguistic morphology , morfología lingüística . Word formation is the term used to describe linguistic processes with which new complex words ( lexemes ) are generated on the basis of existing linguistic means. These linguistic means can be simple and complex words, morphemes and affixes .

A part of speech or class of speech , categorías morfosintácticas as a lexical category, is understood to be the class of words in a language based on their assignment according to common grammatical features.

Word formation, formación de palabras

Word formation is one of the main forms of vocabulary expansion , alongside a change in meaning , cambio léxico-semántico and borrowing , préstamo lingüístico . As such, they are methods of lexical innovation .

At any time, epoch and in a constantly changing environment, people are called upon to react to the fact of missing words or linguistic means of expression by continuously expanding their vocabulary , procesos de formación de palabras . For the production of new words from existing words , i.e. word formation , formación de palabras , two variants are distinguished:

- Word derivation ( derivation , derivación );

- Word composition ( composition , composición ) and

- Parasynthesis, parasíntesis .

Derivation is characterized by the fact that a lexeme with one or more affixes combines on a morphological level to form a new unit of the Spanish vocabulary. When composing, the formation of a new word by combining at least two existing words (or word stems ).

- In the case of word derivation or derivation, derivación , a base lexem , base lexemática is combined with just one or several affixes to form a new word.

- Derivation = base lexeme + affix

Therefore, depending on their position in relation to the basic complex , affixes, afijos can be divided into:

-

- Prefixes , prefijos before the base lexeme: im — pur o, im — posible ;

- Infixes , infijos or Inter Fixed midst of Basislexems: buen — ec -ito

- Suffixes , sufijos after the base lexeme: internacio- al

There is also the option of combining several affixes for word formation: des — nacion — al — izar .

- In the case of composition, composición , two and possibly several autonomous lexemes are combined to form a new word.

- Composition = Lexeme + Lexeme + (n-Lexeme)

In Spanish there are various word combinations:

- Verb and noun verbo + sustantivo : saca-corchos , abre-latas , agua-fiestas .

- Noun and adjective sustantivo + adjetivo : agua-marina , campo-santo , paso-doble , pelir-rojo , boqui-abierto , cari-lleno .

- Adjective and noun adjetivo + sustantivo : extrema-unción . media-noche , salvo-conducto , bajor-relieve .

- Noun and noun sustantivo + sustantivo : boca-calle , coli-flor , sueldo base , casa cuna , moto-carro , hombre lobo , hispano-hablante.

- Adjective and adjective adjetivo + adjetivo : sordo-mudo , verdi-azul , agri-dulce , alti-bajo.

- Adverb and adjective adverbio + adjetivo : biem-pensante .

- Noun, verb sustantivo + verbo : faz-ferir.

- Pronouns and verb pronombre + verbo : cual-quiera , que-hacer , quien-quiera.

- Verb and verb verbo + verbo : duerme-vela.

Another form of «word formation» is the expansion of meaning . The speakers of a language community can react to the demands of a constantly changing environment by changing the meaning or the change in meaning of existing words in their language by expanding their meaning. The word “pantalla”, for example, has its original relation to the object of an “ umbrella ”, for example protection. With the demands later, its meaning expanded to “cinema screen”, “screen” or “display”.

Another way of forming new words is nominalization and its opposite is denominalization .

In the area of loan words or borrowing , préstamo lingüístico for example in the terminology of electronic data processing , the English language has a great influence . The Internet vocabulary in Spanish in particular has a high number of Anglicisms or Anglo-American word creations.

Not to go unmentioned:

- the apheresis , aféresis . — Example: bus for autobus .

- the apocopying , apócope . — Example: cine for cinema .

- the contraction , contracción . — Example: docudrama from documento and drama .

- the epenthesis , epéntesis . — Example: toballa for toalla .

Parts of speech, categorías morfosintácticas

The part of speech theory tries to classify the lexical- grammatical units of a language. The part of speech must be distinguished from the syntactic function (sentence function) of a word such as subject , object , adverbial , attribute , etc.

Words can therefore be classified according to their meaning ( semantic ), according to their form ( morphological ) or according to their use in the sentence ( syntactic ). The speech of Spanish can be like everywhere in lexical and grammatical words divided, roughly content words and function words .

Both classes contain inflected , conjugable and immutable words:

| Meaning, function ↓ | Forms, classes | |

|---|---|---|

| flexible | flexionless | |

| Lexically | Noun , sustantivo |

Numerical word , nombre numeral |

| Lexically | Adjective , adjetivo | Adverb , adverbio |

| Lexically | Verb , verbo |

Particle , partícula gramatical

Interjection , interjección |

| Grammatically | Article , artículo | Preposition , preposición |

| Grammatically | Pronoun , pronombre | Conjunction , conjunción |

Classifications

A word can be examined from different perspectives or scientific approaches, as follows:

- phonological criteria, criterio fonológico .

- morphological criteria, criterio morfológico .

- functional criteria, criterio funcional .

- semantic criteria, criterio semántico .

One word , palabra , is morphologically composed of meaningful units called morphemes , morfemas . Two classes can be constructed semantically and functionally for these morphemes:

- the lexical morphemes ( lexemes ), morfemas léxicos and

- the grammatical morphemes, morfemas gramaticales .

To simplify matters , the two groups can be summarized in such a way that the lexemes (lexical content morphemes ) preferably describe or verbalize facts , things , actions , properties . The grammatical morphemes (grammatical function morphemes ), however, the relationships between these facts, facts. They also give expression to more abstract categories of meaning, such as gender , number , tense .

Words either have a more lexical or grammatical meaning. With the lexical word classes, the main semantic information is conveyed to the recipient on the part of the language producer in a text , the spoken text , whereas the grammatical word classes or units are more functional characters. The group of grammatical units, including inflectional morphemes , functional words (such as structural verbs ), affixes , etc., is much more limited in number than the lexical word units.

literature

- Helmut Berschin , Julio Fernández-Sevilla, Josef Felixberger: The Spanish language. Distribution, history, structure. 3. Edition. Georg Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2005, ISBN 3-487-12814-4

- Franz Rainer: Spanish word formation theory. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1984, ISBN 3-484-50337-8

Web links

- Ursula Reutner: Marking information in Spanish lexicons. The example of euphemisms. Romance Linguistics, University of Augsburg, pp. 1–15 — Romance Studies in Past and Present 14.2 (2008), Helmut Buske Verlag, Hamburg [2]

Individual evidence

-

↑ Another, rather rare process is that of the new creation or original creation (cf. Wolfgang Fleischer, Irmhild Barz, with the collaboration of Marianne Schröder: Wortbildung der Deutschen Gegenwartsssprach. 2nd, revised and supplemented edition. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1995, ISBN 3-484 -10682-4 , p. 5f., Johannes Erben: Introduction to the German Word Formation Theory . 3rd revised edition, Schmidt, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-503-03038-7 , p. 18f.).

- ^ Paul Gévaudan: Typology of lexical change. Change of meaning, word formation and borrowing using the example of the Romance languages. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-86057-173-6 , pp. 34f., 42-44. Another form of change is lexical depletion.

- ↑ Martin Becker: The Development of Modern Word Formation in Spanish: The Political-Social Vocabulary Since 1869. Bonn Romance Works, Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-631-51011-X .

- ↑ Kim Vermeersch: The desubstantivic ‘ornative’ verbs in German and Spanish: A chapter from the word formation viewed in contrast. Universiteit Gent, 2011/2012 [1]

- ↑ Reglas de ortografía. Prefijos y sufijos.

- ^ Justo Fernández López: Word formation. Formación de palabras. hispanoteca.org

- ^ Antoon van Bommel, Kees van Esch, Jos Hallebeek: Estudiando español, basic grammar. Ernst Klett Sprachen, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-12-535499-9 , p. 178 f.

- ↑ Juan Antonio Marín Candón: Prefijo- sufijo. Reglas de Ortografía.

- ↑ Wolf Dietrich, Horst Geckeler: Introduction to Spanish Linguistics. (= Basics of Romance Studies. Volume 15). Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-503-06188-6 , pp. 88-99.

- ^ Mervyn F. Lang: Formación de palabras en español: morfología derivativa productiva en el léxico moderno. Ed. Cátedra, Madrid 1990, ISBN 84-376-1145-8 .

- ^ Rainer Walter: Spanish word formation theory. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-11-095605-5 .

- ↑ Diccionario de la lengua española. Real Academia Española

- ↑ The word originally comes from the Catalan «pàmpol» where it means «vine leaf», «lampshade» and is related to the Latin word «pampinus» for vine leaf pampinus

- ↑ Martina Rüdel-Hahn: Anglicisms in the Internet vocabulary of the Romance languages: French — Italian — Spanish. Dissertation . Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf 2008.

^ Paul Gévaudan: Classification of Lexical Developments. Semantic, morphological and stratic filiation. ( Memento of the original from June 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Dissertation. University of Tübingen, Tübingen 2002, p. 150 f.

- ↑ Justo Fernández López: Apokope, Epenthese, Contraction — Apócope, epéntesis y contracción. hispanoteca.eu

- ^ Bernhard Pöll: Spanish Lexicology. An introduction. Gunter Narr Verlag, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-8233-4993-7 , p. 36.

- ^ Table based on Helmut Berschin, Julio Fernández-Sevilla, Josef Felixberger: The Spanish language. Distribution, history, structure. 3. Edition. Georg Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2005, ISBN 3-487-12814-4 , p. 161.

↑ Numerals, nombres numerales can be inflected to a limited extent .

- ↑ Interjections, interjecciónes and particles, partícula gramatical , as structural elements in the sentence, also have a grammatical function

- ^ Modified from Helmut Berschin, Julio Fernández-Sevilla, Josef Felixberger: The Spanish language. Distribution, history, structure. 3. Edition. Georg Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2005, ISBN 3-487-12814-4 , p. 161.

- ↑ The word grammar , canoonet

You are probably familiar with the common conception that an easy way to form a Spanish word from an English one is simply by adding an «o» to the end of it. Although this may be true in 1% of cases, read on to learn Spanish word formation hacks that will work more often.

In this article, you will be learning how to form Spanish words that are very similar to the English words and that have the same meaning in both languages. These types of words are called cognates, and they are a language learner’s best friends. An example would be that the Spanish word conversación. This word is easily recognizable as the English word conversation. Sometimes cognates are exactly the same in both languages. These are called exact cognates. The common misconception that you can create a Spanish word by simply adding o to the end of an English one likely comes from knowing a few exact cognates in Spanish. A few examples are rodeo, macho, and solo. These three words are exactly the same in English and Spanish. Now that you know that cognates are your friends, take a look at these Spanish word formation hacks.

English Words Ending in «tion»

This word formation hack is pretty simple and words pretty often. If you take an English word that ends in tion, change the t to c, and add an accent to the o (ó), you will have hacked your way into forming a Spanish word. For example, information becomes información in Spanish. Participation in Spanish is participación. This hack works very well for forming Spanish words by looking at the English ones. It does not always work exactly though. An example is the word atención. Although the t changes to a c, and you add the accent to the o, you also have to remove a t. It is always best to look up a word to make sure of your hack, but in a bind, 9 times out of 10, changing tion to ción will create the Spanish word. Do pay attention to the difference in pronunciation, however. Click on atención to hear the correction pronunciación for the ending ción in Spanish.

Forming the Spanish word from an English word that ends in sion only requires you to make one small modificación: add an accent to the o. Words formed in this way are usually exact cognates. Tension turns into tensión. Fusion becomes fusión. Version in Spanish is versión. Although English words ending in sion will simply add an accent to form the Spanish, you may have to drop some of the letters from the English word to create the Spanish one. For example, aggression drops a g and an s to form the Spanish word agresión. This modificación is due to the fact that the only double letters found in Spanish words are rr and ll and sometimes cc. Anytime an English word has a double letter other than r or l in this Spanish hack words, you will have to drop one of the double letters. Admission becomes admisión, and commission becomes comisión. Although dropping the double letter does not affect the pronunciación, it is always best to consult a dictionary to make sure your written comunicación is accurate.

English Words Ending in «ary»

The next Spanish word formación hack is creating Spanish words from English words that end in ary. The English word adversary will turn into adversario in English. Contrary becomes contrario. The English word primary, in Spanish, becomes primario. Like all rules, there are always going to be excepciones. The month of January does not become Januario. It is enero. Similarly, library is not librario. It is biblioteca. This hack is best paired with a diccionario. Another way to safely use this hack is to only use it for forming adjectives. Like the previous word formation hacks, some spelling modifications will be necesario.

By

Last updated:

August 31, 2022

Spanish sentence structure can be baffling even for intermediate speakers.

The thing is, it’s essential to know to be able to communicate effectively. If you accidentally switch the order of the words, you can end up saying something completely different from what you’re thinking.

And while misunderstandings make for great sitcom material, we don’t want you in that position.

Here’s what you need to know, so you can go from situational comedy to fluency.

Contents

- Why Learn Spanish Sentence Structure?

- Learning the Basics of Spanish Sentence Structure

- Spanish Sentence Structure: A Brief “Theory of Chaos”

-

- Spanish Word Order

- Spanish Declarative Sentences

- Negation in Spanish

- Questions in Spanish

- Indirect Questions in Spanish

- Spanish Adjective Placement

- Spanish Adverb Placement

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Why Learn Spanish Sentence Structure?

Sentence structure involves the word order in a sentence.

When you start learning a new language, you want to start speaking it right away, but you feel there is always something holding you back, making it impossible for you to make sense when you try to say something.

That something could very well be sentence structure, so we’ve got to learn it early. Why?

When you master the art of word order, you can put into practice all those vocabulary and grammar rules you have learned, and produce perfectly grammatical and native-sounding sentences with the exact meaning you had in mind.

Learning the correct structure for a sentence also opens up your communication possibilities, as you can then easily substitute words in certain sentence format to get a ton of different phrases.

And finally, learning Spanish sentence structure will save you from embarrassing mistakes, since you’ll be able to say what you actually mean to say.

So if you don’t want to end up with a coin in your hand like Michael, don’t leave yet. It’s high time you started learning a little bit about Spanish sentence structure.

Learning the Basics of Spanish Sentence Structure

Sentence structure can sometimes be daunting for a native speaker of a language, let alone for students. However, its bark is worse than its bite, and there are always some rules we can apply in order to bring some order to that chaos.

Like in English, changing the sentence structure in Spanish can lead to misunderstandings. We will see later that the typical word order in Spanish is SVO (Subject, Verb, Object), but I have good news for you! Spanish is a very flexible language, and most of the time you’ll be able to change that order without altering the meaning of the sentence or making it completely ungrammatical.

Have a look at the following example:

Mi hermano está leyendo un libro. (My brother is reading a book.)

We have a subject (Mi hermano), a verb form (está leyendo) and an object (un libro).

Now imagine I have gone mad and changed the word order of the sentence, like this:

Un libro está leyendo mi hermano. (Literally: A book is reading my brother.)

As you can see, the Spanish sentence is still grammatically correct, but the literal translation into English has become a little weird, to say the least.

Since it’s really odd seeing a book reading a person (isn’t it?), we would have to rearrange that English sentence if we want to keep the original meaning, and say something along the lines of, “It is a book that my brother is reading.”

From this example you can see that Spanish definitely has flexibility with its word order, but there are certain instances that offer no flexibility, which are really important to learn.

You can get a better understanding of Spanish sentence structure by seeing it in actual Spanish-language content.

For example, you can read a simple Spanish book and note key sentence structure elements. If it’s your book, you could literally mark it up, writing the part of speech, form, tense, etc. of each word in the sentence.

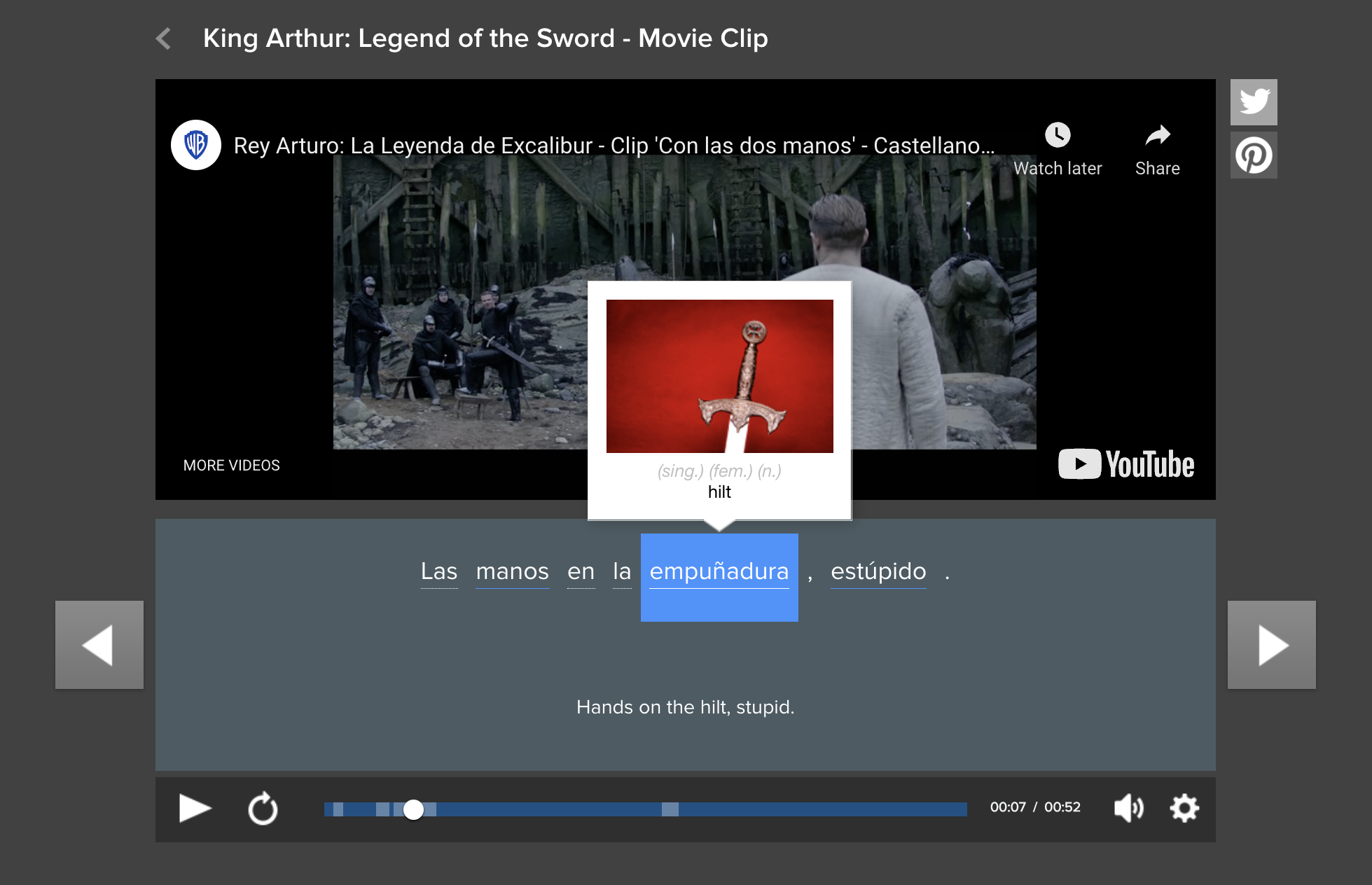

You can also use FluentU to hear spoken Spanish in authentic videos. Watch clips like movie trailers, music videos, news segments and other Spanish-language media.

You can easily follow along thanks to accurate subtitles and check the meaning and part of speech of any word with a click. Clicking on the word also shows you example sentences and video clips with the word in use, for even more help with sentence structure.

So sit back, relax and enjoy this journey through Spanish sentence structure. And watch out for turbulence!

Spanish Sentence Structure: A Brief “Theory of Chaos”

Spanish Word Order

As I mentioned in the introduction, word order is quite important in Spanish (as in any other language) because it can be a little chaotic and can lead to misunderstandings if you don’t keep to it.

Spanish and English have the same basic word order scheme, SVO (Subject, Verb, Object), but there can be big differences between the two languages, and we do not always use said scheme. In the following points you will learn how to master word order not only in declarative sentences, but also in questions and in negation.

You will also learn where to insert Spanish adjectives in the sentence, and how the meaning can be different if you make some little changes. Lastly, I’ll show you where to put Spanish adverbs in a sentence. Off we go!

Spanish Declarative Sentences

Declarative sentences are pretty straightforward because they tend to look the same both in Spanish and in English.

In order for a sentence to be grammatical, we need at least a subject and a verb. Then we can add an object or any other word category we may need. Example:

Yo leo. (I read.)

Yo leo libros. (I read books.)

There are, however, a couple of situations when a declarative sentence in Spanish can be a little different from its English translation:

1. In Spanish you do not need to add a subject, except if used for emphasis:

Leo libros. (I read books.)

Yo leo libros (It is me who reads books, not you, not him.)

2. Because of this, you will always have a conjugated verb in a Spanish sentence, and it needs to agree in person and number with the omitted subject:

(Yo) Compro manzanas. (I buy apples.)

(Tú) Compras manzanas. (You buy apples.)

(Ellos) Compran manzanas. (They buy apples.)

3. Insert pronouns directly before the verb, not after it:

Las compro. (I buy them.)

Lo leo. (I read it.)

Se la enviamos. (We send it to her.)

4. There are times when you can put the verb in front of the subject! This is true especially when dealing with passives:

Se venden libros. (Books for sale.)

Se habla español aquí. (Spanish is spoken here.)

5. Thanks to Spanish being a very flexible language, many times you will be able to change the word order without making the sentence ungrammatical. As a result, you will have different sentences with practically the same meaning. Use this technique only when you want to put emphasis on a specific sentence constituent:

(Yo) leo libros.

(I read books.)

Libros leo (yo).

(Literally: “Books I read.” Meaning: It is books that I read, not magazines.)

Leo libros (yo).

(Meaning: I read books, I don’t sell them, I don’t burn them, I just read them).

However, bear in mind that you will not be able to do this every time (like with adjective placement, as we’ll see in a bit). Try to follow the basic scheme and the rules above so that you always have it right.

Negation in Spanish

Spanish negation is really, really easy. Basically, what you have to do is add “no” before the verb:

No compro manzanas. (I don’t buy apples.)

No leo libros. (I don’t read books.)

If you have a pronoun in the sentence, add “no” before it:

No las compro. (I don’t buy them.)

No los leo. (I don’t read them.)

This is also true when you have two pronouns:

No se los leo. (I don’t read them to him.)

If the answer to a question is negative, you will probably need two negative words:

¿Lees libros? (Do you read books?)

No, no los leo (No, I don’t.)

(Note: While in Spanish we need to use the verb in the answer, in English you can just use the auxiliary.)

The only tricky part in Spanish negation is probably the double negation, but even this is easy.

First of all, have a look at this list of negative words:

nada (nothing)

nadie (nobody)

ningún, -o, -a, -os, -as (any, no, no one, none)

ni (nor)

ni…ni (neither…nor)

nunca (never)

ya no (no longer)

todavía no (not yet)

tampoco (neither)

There are two ways of using these negative words in a sentence:

1. You can use them alone before the verb (Remember not to use “no” in that case!).

Nunca leo. (I never read.)

Nadie ha comprado manzanas. (Nobody has bought apples.)

2. You can use “no” before the verb, and add the negative word after the verb.

No leo nunca. (I never read.)

No ha comprado nadie manzanas. (Nobody has bought apples.)

Unlike English, in Spanish you can even find three negatives:

No leo nada nunca. (I never read anything.)

And even four! Have a look:

No leo nunca nada tampoco. (I never read anything either.)

Questions in Spanish

Asking questions in Spanish is way easier than in English because you don’t use auxiliary verbs to make questions. The only thing you have to bear in mind is whether you are asking a yes/no question or are expressing incredulity.

Expressing incredulity is the easiest. Just add question marks at the beginning and the end of the declarative sentence and you are ready to go:

María lee libros. → ¿María lee libros?

(Maria reads books. → Really? Maria reads books? How surprising!).

If you are expecting a real answer, just invert the subject and verb:

¿Lee María libros? Sí, lee cada mañana.

(Does María read books? Yes, she reads every morning.)

When we have a question word (qué – what, cuándo – when, por qué – why, quién – who, dónde – where, cómo – how, cuál – which, cuánto – how much, etc.) we normally use inversion:

¿Por qué lee María?

(Why does María read?)

¿Cuánto cuestan las manzanas?

(How much do the apples cost?)

Indirect Questions in Spanish

An indirect question is a question embedded in another sentence. They normally end up with a period, not a question mark, and they tend to begin with a question word, as in English.

Indirect questions work very similarly in English and in Spanish. You will have the beginning of a sentence, and inside you’ll find the indirect question embedded. Have a look at the following examples:

No sé por qué María lee.

(I don’t know why Maria reads.)

Dime cuánto cuestan las manzanas.

(Tell me how much the apples cost.)

As you can see, indirect questions look exactly the same as a declarative sentence; there’s no inversion nor any other further changes.

There are two types of indirect questions. The first type contains a question word, as in the examples above. The second type requires a yes/no answer, and instead of using a question word, you will have to use “si” (if, whether):

Me pregunto si María lee.

(I wonder if Maria reads.)

Me gustaría saber si has comprado manzanas.

(I would like to know if you have bought apples.)

You can also add “o no“ (or not) at the end of the indirect question:

¿Me podría decir si María lee o no? (Could you tell me whether María reads or not?)

Spanish Adjective Placement

When you start studying Spanish, one of the first rules you’ll have to learn is that adjectives usually come after the noun in Spanish.

El perro grande (the big dog)

El libro amarillo (the yellow book)

El niño alto (the tall child)

However, this rule is broken quite often. It is true that you should put the adjectives after the noun. In fact, sometimes it is not correct to put them before the noun. Still, there are some adjectives that can take both positions. Bear in mind, though, that the meaning of the sentence changes depending on the position of those adjectives!

Here you have some of them:

Grande:

When used before the noun, it changes to gran, and it means great: un gran libro (a great book).

When used after the noun, it means big: un libro grande (a big book).

Antiguo:

Before the noun it means old-fashioned or former: un antiguo alumno (a former student).

After the noun it means antique: un libro antiguo (an antique book).

Mismo:

Before the noun it means “the same”: el mismo libro (the same book).

After the noun it means itself, himself, herself, etc.: el niño mismo (the child himself).

Nuevo:

Before the noun it means recently made: un nuevo libro (a recently made book).

After the noun it means unused: un libro nuevo (an unused book).

Propio:

Before the noun it means one’s own: mi propio libro (my own book).

After the noun it means appropriate: un vestido muy propio (a very appropriate dress).

Pobre:

Before the noun it means poor, in the sense of pitiful: el pobre niño (the poor child).

After the noun it means poor, without money: el niño pobre (the poor, moneyless child).

Solo:

Before the noun it means only one: un solo niño (only one child).

After the noun it means lonely: un niño solo (a lonely child).

Único:

Before the noun it means the only one: el único niño (the only child).

After the noun, it means unique: un niño único (a unique child, but ser hijo único means to be an only child).

Spanish Adverb Placement

Adverb placement is pretty flexible in Spanish, although there is a tendency to put them right after the verb or right in front of the adjective:

El niño camina lentamente.

(The boy walks slowly.)

Este tema es horriblemente difícil.

(This topic is horribly difficult.)

You can place adverbs almost everywhere in the sentence, as long as they are not far from the verb they modify:

Ayer encontré un tesoro.

(Yesterday I found some treasure.)

Encontré ayer un tesoro.

(I found yesterday some treasure*) Still correct in Spanish!

Encontré un tesoro ayer

(I found some treasure yesterday).

If the object is too long, it is much better to put the adverb directly after the verb and before the object. For example, the following:

Miró amargamente a los vecinos que habían llegado tarde a la reunión.

(He looked bitterly at his neighbors who had arrived late to the meeting.)

is much better than:

Miró a los vecinos que habían llegado tarde a la reunión amargamente.

You can create an adverb from most Spanish adjectives. In order to do that, choose the feminine, singular form of the adjective and add the ending -mente (no need to make any further changes):

rápido → rápida → rápidamente (quickly)

lento → lenta → lentamente (slowly)

claro → clara → claramente (clearly)

cuidadoso → cuidadosa → cuidadosamente (carefully)

amargo → amarga → amargamente (bitterly)

When you have two adverbs modifying the same verb, add -mente only to the second one:

El niño estudia rápida y eficientemente.

(The boy studies quickly and efficiently.)

Mi hermano habla lenta y claramente.

(My brother speaks slowly and clearly.)

On the other hand, there are some adverbs that do not end in -mente. These simply have to be learned by heart, including:

mal (poorly)

bien (well)

aquí (here)

allí (there)

siempre (always)

nunca (never)

mucho (a lot)

muy (very)

poco (little)

And with that, you’ve now taken many steps further into your Spanish learning, while replacing chaos with harmony. You’ve improved your Spanish writing, speaking and overall language skills.

Practice will make all these concepts familiar and instinctive over time. Soon enough, the mystery of Spanish sentence structure will be dispelled, and you’ll be hopping into conversations with grace and confidence!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

1.1 Approaches to word formation

As a branch of linguistic science, word formation is concerned with analysing and understanding the mechanisms by which the lexis is created and renewed. These mechanisms are mainly morphological, involving the combination of words and their subunits in various ways, although word creation may also involve other procedures such as borrowing words from other languages, the formation of new terms through the combining of initial letters of the names of institutions, generally known as acronymy, or the subtraction of units from words in processes known as back formation or clipping. The data with which word formation is concerned is to be found not only in the existing lexis of the language as recorded in the dictionary, but also in the neologistic terminology of science, technology, commerce, the mass media, in the creative language of modem literature, and in the colloquial and innovatory language of contemporary speech.

In handling these sources of data, the approach may be diachronic, looking back to the etymological sources of word forming procedures and examining the dominant morphological patterns of the past; or it may be synchronic, referring to present-day tendencies which will determine the features of the vocabulary in the immediate future. It may be illuminating to combine these approaches as Marchand (1969), for example, has done to a certain extent in his exhaustive account of English word formation. Whether diachronic, synchronic, or both combined, a variety of criteria has to be applied in attempting to account adequately for the many regularities as well as the real or apparent irregularities which characterise the procedures of word formation. Etymological analysis can show which patterns are due to Greek or Latin sources and how word forming units evolved in meaning and function in the evolution of Castilian. Morphological criteria will be applied in describing the actual permissible combinations of units, and these in turn are invariably governed by the dominant sound features of the language requiring the application of the principles of phonology. Semantic considerations have to be taken into account in explaining relationships between word components and the result of their combination with regard to meaning. Since the final result of these procedures is a new term which will require immediate or eventual entry in the dictionary, then lexicographical implications ensue. So word formation involves aspects of all the major divisions of linguistic analysis, making it a particularly complex area of study and bringing together many critical problems of present-day linguistic theory.

Different schools of linguistics, while exploiting all such criteria, have tended to favour one or another at particular times. In the pretwentieth century diachronic focus, attention was concentrated on the striking transformations of the lexis over the centuries, and in particular on the way in which the vocabulary seemed to be structured in historical layers through successive periods of different ethnic influences.1 Thus the constituent parts of the vocabulary of Spanish were perceived as being Latin, Greek, and Arabic words, as in the Arabic series in a/- (<algarroba, alguacil, alfiler, etc.), or word parts as in the latin suffix -tas (sinceritas, Jutilitas, gravitast etc.) which yielded the long Spanish abstract noun of quality series in -dad (sinceridad, futilidad, gravedad, etc.). These historical criteria were reflected in the dictionary where the current forms of the entries were explained by their etymological origins, as exemplified in the Vox dictionary (1964):

Although three of these items show compositional morphological structure the emphasis in the entry is on the etymology rather than on the structure. In the same way, in specific studies of word formation applied to individual languages, great attention is always paid to etymology, as for example in Tekavčič’s account of Italian derivational morphology, where the Latin and Greek sources of the components are given priority in the descriptions (Tekavčč: 1972). This emphasis is seen in the strongly diachronic approach of traditional studies of Spanish word formation as well as in the treatment of derivational morphology in traditional grammars. So, for example, the comprehensive pedagogical grammar of Ragucci (1963) which distinguishes itself by the close attention given to an aspect of language often skirted in grammars, deals with it in a chapter headed:

Breves nociones de Etimología. -Formatión de las palabras. -Derivatión, compositión y parasíntesis. — Palabras primitivas y derivadas; simples, compuestas y parasintéticas. -Análisis etimolégico.

In this approach, etymology and word formation are thus regarded as one, with suffixes and prefixes classified on an etymological basis (castellanos, latinos, griegos). Similarly, the distinction of Latin, Greek, and Castilian is basic to the Spanish Academy’s approach, as shown in the Gramática de la Lengua Española of 1931.

In the early twentieth century, the advent of Saussurian linguistics marked a change in emphasis away from the historical account of language to a synchronic descriptive approach, studying the systems and rules of the internal mechanisms of language, independently of the historical or ethno-cultural environment. Here, however, word formation was not in the forefront of interest; on the one hand it combined diachrony and synchrony which the new linguists were keen to keep separate, and on the other it was concerned with productive procedures going beyond synchrony and looking towards the future state of the language by way of lexical change and innovation. In the post-Saussurian period, interest concentrated not on the word but on the minimal segments of speech as represented by the morpheme and the phoneme and analysed without close regard to their combination into larger units, and the very status of the word was questioned as a useful unit of analysis.2

Just as the advent of Chomskian linguistics from the late 1950s marked a dramatic innovation in general linguistic theory, it eventually did so also in the treatment of word formation. Although initially transformational-generative grammar was concerned with syntax in its attempts to explain the creativity and competence of the native speaker in producing and understanding an infinite number of new sentences, the problems posed by the plethora of structure models which emerged led to a new interest in the word, especially in its function as the lexical insertion component in deep structure and its syntactic relationship with the rest of the sentence. At the same time, by stressing the creative rather than the prescriptive aspect of the grammar, transformationalism could no more overlook the ability of the native speaker to speak and understand new words than it could the ability to construct and understand new sentences. As well as an innate grammatical faculty, the native speaker was perceived to be endowed with an inherent lexical competence, which is the basis of the lexicon and of neologistic terminology not yet recorded in the dictionary. In this way, from being marginal, word formation has come to play a central role in general linguistic theory, and under the label of ‘derivational’ or ‘lexical’ morphology become the raw material of a wealth of modern theories evolving from transformational-generativism.3

In the later development of transformational-generative grammar, word formation ceased to be isolated from phrase structure and sentence formation. Indeed, ‘the development of transformational or transformational-generative grammar from its beginnings up to the present can be seen, among other ways, as a progressive refinement of the structure of the lexical component’ (Scalise 1984: 1). Following the tenets of post Chomskian syntactic theory, the procedures involved in forming words were taken as being analogous to those involved in forming new sentences. The form of complex words was seen as itself containing syntactic structure, the derivative or compound being no more than a surface representation of this, a sort of graphic shortcut. Stemming from this, linguists enthusiastically applied transformational analysis to the lexis in an attempt to explain word formation on some logical basis. An example of this is the prolific work of Guilbert in French, both in the study of individual lexical subject areas and in the dictionary as a whole.4 In Spanish this might be exemplified as follows, where a) = derivative lexeme and b) = underlying syntactic structure:

In terms of transformational-generativism these represent surface realisations of transpositions from verb to noun structures. This approach may be specious in seeing everything in terms of deep structure and tending to be over-preoccupied with the verb and noun phrase relationship which fascinated the post Chomskian linguists. It tends, for example, to overlook other types of syntactic links in word formation, such …

Related Papers

The aim of this chapter is to study de relationship between verbs and deverbal nouns within the derivational series and sub-series which constitute a word family. Specifically, it explores, from a historical point of view, some of the changes that Spanish deverbal nouns have undergone inside derivational series with regard to their original base verb. In doing so, this article proves that morphological irregularities can only be detected from a diachronic perspective.

The rise of the Internet has fueled a rapid borrowing of English-language computer and Internet related lexical resources into Spanish, at the same time that it has provided an unprecedented opportunity to observe the results of this virtual language contact. The traditional stages of adaptation and integration are occurring simultaneously rather than sequentially. Many borrowings reflect early stage orthography, flagging, metalinguistic clarification, and non-typical phonology, accompanied by a full range of late stage morphological exploitation. Computer and Internet related loanwords serve as bases for the full range of word formation processes in Spanish, including inflection, prefixation, emotive and non-emotive suffixation, acronymy, clipping, and composition and blending. However, while many borrowed bases are available for the creation of loanblends of all types, the number of native morphemes with which the bases combine is actually quite reduced, representing a very small …

The most productive way to encode ablative, privative, and reversative meanings in current Catalan and Spanish is by means of des- prefixation. This paper investigates how these related values are obtained both from a structural and from a conceptual perspective. To analyze the structural behaviour of these predicates, a new neoconstructionist model is adopted: Nanosyntax, according to which lexical items are syntactic constructs. As for the conceptual content associated to these verbs, it is accounted for by means of a non-canonical approach to the Generative Lexicon Theory developed by Pustejovsky (1995 ff.). The core proposal is that des- prefixed verbs with an ablative, a privative, or a reversative value share the same syntactic structure, and that the different interpretations emerge as a consequence of the interactions generated, at a conceptual level, between the Qualia Structure of the verbal root and that of the internal argument of the verb.

Résumé En théorie, les verbes « effectifs » ou « résultatifs », précédés de des-, ont une valeur ingressive (d’entrée dans un état) et non égressive (de sortie d’un état), contrairement au reste des verbes précédés de ce même préfixe. L’article commence par une analyse diachronique de ce type de constructions, ce qui permet de rendre compte des processus morphologiques et sémantiques ayant conduit à leur apparition dans la langue. Compte tenu du traitement des données historiques, on arrive à la conclusion que tous les verbes préfixés par des- ont une valeur égressive et non ingressive. Par ailleurs, les données recueillies dans ce travail vont à l’encontre du prétendu statut parasynthétique de ces verbes effectifs. Resumen La presente investigación pretende dar respuesta al problema que supone afirmar que los verbos efectivos prefijados con des-, a diferencia del resto de verbos encabezados por este mismo prefijo, tienen valor ingresivo (de entrada a un estado) y no egresivo (de salida de un estado). Para dar respuesta a este problema se parte de un análisis diacrónico de este tipo de formaciones que permite dar cuenta de los procesos morfológicos y semánticos que motivaron su aparición. Teniendo en cuenta la información histórica, se propone que los verbos efectivos con prefijo des-, al igual que el resto de formaciones encabezadas por dicho prefijo, tienen valor egresivo y no ingresivo. Asimismo, apelando también a evidencias históricas, se pone en tela de juicio el asumido estatus parasintético de tales verbos.

The main aim of this paper is to examine the word formation of denominal parasynthetic verbs with prefix a- in Old Spanish. The analysis relies on the lexical semantics viewpoint of the Generative Lexicon. I argue that the polysemy in denominal parasynthetic verbs can essentially be attributed to the semantic features of the nominal stem. Regarding the data under study, the paper focuses on the verbs contained in Nebrija’s Vocabulario (1495). This information is compared with the one provided by the Spanish textual corpora CORDE, CE and CDH.

The dissertation aims mainly to develop a descriptive and quantitative framework to analyze the morphosemantic features of EVALs in view to obtain measurable parameters that can be applied cross-linguistically in EM studies, both descriptive and contrastive. Accordingly, the following tasks have been established to achieve various individual objectives: 1. To review critically EM literature and survey up-to-date theoretical perspectives to assess the state of affairs in the study field. 2. To identify and discuss terminological and conceptual discrepancies in the relevant literature, and to adopt a set of terms that may be applicable cross-linguistically. 3. To define and characterize EVALs as a distinctive lexical type within the larger group of evaluative constructions. 4. To establish a set of analytical variables associated with productivity and diversity in EVAL-formation, and to provide quantitative measurements of how each variable is represented in a language’s EM system. 5. To carry out a detailed review and critical analysis of existing literature on Spanish and Latvian EM, as well as a systematic description and contrastive analysis of their respective EM resources.

We might not always like to admit this when we’re starting to learn a language, but the truth is that one can’t speak properly without knowing how to put sentences together. If you use the wrong word order, there’s a chance that what you’re saying might have a different meaning than what you intended, or it might have no meaning at all.

To avoid this, here’s the perfect article for you to learn Spanish sentence structure. You’ll soon learn that Spanish word order is actually not so hard, and that, in some ways, it’s similar to word order in English. You’ll also learn that, in fact, it’s more flexible! That means you can change the order of words a little bit more than you can in English.

Table of Contents

- Overview of Word Order in Spanish

- Basic Word Order with Subject, Verb, and Object

- Word Order in Negative Sentences

- Word Order with Prepositional Phrases

- Word Order with Modifiers

- Changing a Sentence into a Yes-or-No Question

- Translation Exercises

- How to Master Spanish with SpanishPod101.com

1. Overview of Word Order in Spanish

Basic Spanish language word order refers to the usual order in which words are found in a sentence. Even though the sentences that we use day-to-day may have other elements in them, to learn this basic order, there are three basic elements that we use as a reference. These three elements are the subject, verb, and object.

Despite Spanish being more flexible than English in this sense, our basic word order is the same:

subject + verb + object (SVO)

Yo + me comí + la tarta

I + ate + the cake

Sometimes, we might want to emphasize one element or another in a sentence. This leads us to moving these around the sentence, but they will keep the same (or very similar) meaning. In English, because the ability to move words in a sentence is quite limited, emphasizing an element is accomplished by intonation.

Let’s look at two sentences. The first one has basic word order, and the other one has a different order. In the second sentence, the emphasized word is marked in bold:

Example: Yo me comí la tarta.

Translation: “I ate the cake.”

Example: Me la comí yo, la tarta.

Translation: “I ate the cake.”

There’s a way of modifying the English sentence to emphasize this element even more: “It is I that ate the cake.” However, this wouldn’t be an accurate translation of our example in Spanish, because in English, we’re not just moving an element around: we’re changing the whole structure.

Did you notice that we actually added an extra word in our second Spanish sentence? If you did, we just want to say: Nice job! The word that we added was a pronoun, and don’t worry, we’ll explain it a little bit later.

We could still modify our sample sentence a bit more:

Example: La tarta me la comí yo.

Translation: “The cake, I ate.”

In this case, we can translate this new structure pretty much literally, but in English, we feel like this sounds quite unnatural. In Spanish, this is completely normal.

2. Basic Word Order with Subject, Verb, and Object

Now, let’s go more into detail about the most basic Spanish word order rules.

1 – Subject

Subject is the person or thing performing the action of the verb. It’s usually a noun phrase, such as a noun or a pronoun: Juan come espaguetis. (“Juan eats spaghetti.”) / Él come espaguetis. (“He eats spaghetti.”).

Sometimes, the subject might be a verb: Cantar es divertido. (“Singing is fun.”). However, as we’ve explained in previous articles, in Spanish, a subject isn’t always necessary and we often drop pronouns when we already know who the subject is: Como espaguetis. (“I eat spaghetti.”).

As we saw in our previous article about verb conjugation in Spanish, the verb como is conjugated, and considering the verb is conjugated in the first person singular, we know it means “I eat,” so there’s no possible confusion.

2 – Verb

The second element in Spanish word order is verbs. You know what verbs are, don’t you? According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a verb is “a word or phrase that describes an action, condition, or experience.”

To give you a few examples: cantar (“to sing”), comer (“to eat”), and hablar (“to talk”) are all verbs. Without them, language wouldn’t make much sense.

3 – Object

The third and last element in basic word order is something we call an object. It isn’t an indispensable element in a sentence, as some verbs don’t require objects, but it’s undoubtedly common and helps us define sentence structure.

Cambridge defines an object as “a noun or noun phrase that is affected by the action of a verb or that follows a preposition.” In the sentence Juan come espaguetis. (“Juan eats spaghetti.”), spaghetti is the thing that is being eaten by Juan.

3. Word Order in Negative Sentences

In some languages, negative sentences can completely change an affirmative sentence. Lucky for you, in this sense, Spanish happens to be quite simple. So, what is the Spanish word order for these negative sentences?

To form a regular negative sentence, all we need to do is add the word no, which in this context is equivalent to “not,” to an affirmative sentence. No is always found before the verb. To illustrate this, let’s use the same example we did before: Juan no come espaguetis. (“Juan does not eat spaghetti.”).

As you know, there are other ways of making a negative sentence. One example would be to add nunca (“never”): Juan nunca come espaguetis. (“Juan never eats spaghetti.”). As you can see, it follows exactly the same structure as the previous example. Simple, right?

Well, there are many other negative words: nada (“nothing”), nadie (“nobody”), ninguno (“none”)… When we use these words, the structure is a bit different, because they can be used in different ways. They can act as subjects or as objects.

For example: Nadie ha comido espaguetis. (“Nobody has eaten spaghetti.”). Here we find the word nadie before the verb, just as we saw in the previous negative sentences. However, that makes sense, because it acts as a subject.

Since we’re mentioning this, we should explain that sometimes these words might be found after the verb, even if they’re a subject. Here are a few examples:

- No hay nadie. → “There isn’t anyone.”

- No hay nada. → “There isn’t anything.”

- No queda ninguno. → “There is none left.”

The negative word in bold in each of these examples is the subject of the sentence, even though it might not be as obvious as in the other examples we’ve seen. We could say that the word in bold is “the thing that isn’t.”

As you might have noticed, the adverb no does appear at the beginning of the sentence, something that happens similarly in the English translation. As you’ll find out in our lesson “How to Be Negative?” in Spanish, it’s quite common to have more than one negative word in one sentence.

4. Word Order with Prepositional Phrases

Another element that needs to be taken into account when talking about word order is prepositional phrases. A prepositional phrase is a type of phrase that always begins with a preposition, such as en (“in,” “on,” “at”) or con (“with”). If you would like to find out more about prepositions, we have an article just for you! Check out our article about Spanish prepositions.

Prepositional phrases are usually found at the end of a sentence, but some of them can be placed at the beginning if you want to emphasize said phrase. Let’s look at some examples of Spanish word order that show this:

Estudio español en casa. → “I study Spanish at home.”

But what if someone asked us:

¿Dónde estudias español? → “Where do you study Spanish?”

In this case, a possible answer we could give them would be:

En casa, estudio español. → “At home, I learn Spanish.”

There are many other prepositional phrases we could add to the same sentence, even together, such as:

Estudio español en casa con SpanishPod101.com. → “I study Spanish at home with SpanishPod101.com.”

5. Word Order with Modifiers

We’ve already seen a type of modifier, which were the ones that turned affirmative sentences into negative sentences. However, there are many more elements in sentences that we call modifiers. These include words such as articles, adjectives, and pronouns.

Determiners are easy, because they always go in front of a noun, just like in English. These are, among others, articles, numerals, and possessives. Let’s look at examples for these types of modifiers:

Articles: El hombre come espaguetis. → “The man eats spaghetti.”

Numerals: Dos hombres comen espaguetis. → “Two men eat spaghetti.”

Possessives: Mi padre come espaguetis. → “My father eats spaghetti.”

However, in Spanish word order, adjectives normally go after the noun, but there are exceptions. For example, in literature, especially poetry, it’s common to write the adjective before the noun. Check out our article on adjectives for more information!

El coche blanco es de mi padre. → “The white car is my dad’s.”

La hermosa princesa abrió los ojos. → “The beautiful princess opened her eyes.”

Pronouns can go either before or after the verb, depending on the kind of pronoun they are, or sometimes depending on what you feel like saying. As we learned in our previous article about pronouns, there are different kinds of pronouns in Spanish. Even though we also talked about the order they follow in that article, we’ll look at them again, one by one:

1 – Personal Pronouns

If you read the article we just mentioned, you might remember that there are many kinds of personal pronouns.

a) Subject Pronouns

Subject pronouns, which are the ones we use for the subject of a sentence, are always found before the verb. This is because, as we saw, in Spanish, the subject is always the first element in a sentence.

Ellos quieren una casa nueva. → “They want a new house.”

b) Direct and Indirect Object Pronouns and Reflexive Pronouns

You probably remember that basic word order in Spanish is subject + verb + object, don’t you? Well, when a direct or indirect object is substituted by a pronoun, the pronoun is actually found before the verb. We’ll illustrate this with a few examples:

Direct object:

Quieren una casa nueva. → La quieren.

“They want a new house.” → “They want it.”

Both direct and indirect objects:

Traigo un regalo para mi madre. → Le traigo un regalo. → Se lo traigo.

“I bring a present for my mom.” → “I bring her a present.” → “I bring it to her.”

Reflexive pronouns work in a very similar way and they’re always found before the verb:

Mis padres se van de vacaciones. → “My parents are going on vacation.”

c) Prepositional Pronouns

Prepositional pronouns follow the same rules that prepositional phrases do, so they can be in different locations inside a sentence depending on what you would like to emphasize.

Sin ti todo es diferente. → “Without you, everything is different.”

Todo es diferente sin ti. → “Everything is different without you.”

d) Possessive Pronouns

A possessive pronoun can be a subject or an object, so its order will depend on the function it does in the sentence:

El nuestro es ese. → “Ours is that one.”

La casa es nuestra. → “The house is ours.”

2 – Demonstrative Pronouns

Just like what happened with possessive pronouns, demonstrative pronouns can be in different places in the same sentence, depending on their function.

Este es mi hermano. → “This is my brother.”

Nunca he estado ahí. → “I have never been there.”

3 – Interrogative Pronouns

Interrogative pronouns are pronouns that help us ask questions, and they’re always the first word in a question:

¿Qué quieres? → “What do you want?”

4 – Indefinite Pronouns

Once again, indefinite pronouns don’t have a specific position in a sentence, because that depends on their function.

Todos quieren dinero. → “Everyone wants money.”

Puedes preguntárselo a cualquiera. → “You can ask anyone.”

5 – Relative Pronouns

Relative pronouns are never found in simple sentences. Rather, we find them in complex sentences. These pronouns always start the second part of the sentence, so they’ll always be in the middle. This might sound odd if you’re not sure what a relative pronoun is, but you’ll understand once you look at an example:

Esta es mi prima que vive en la ciudad. → “This is my cousin who lives in the city.”

6. Changing a Sentence into a Yes-or-No Question

In many languages, to transform a normal sentence into a yes-or-no question you must change it a fair bit, or change the order. In Spanish, this is way simpler. So, what is the Spanish word order in questions? Look at these examples:

Estudias español todos los días. → “You study Spanish every day.”

¿Estudias español todos los días? → “Do you study Spanish every day?”

As you probably noticed, it’s exactly the same structure. This doesn’t only happen with specific structures: it happens every time you turn a sentence, either affirmative or negative, into a yes-or-no question.

We’re sure you enjoyed learning this, but you probably know that there are other kinds of questions. If you feel a bit lost when it comes to this topic, you might enjoy our lesson on 15 Questions You Should Know.

7. Translation Exercises

We thought it would be useful to you to see how we transform a simple sentence into more complex sentences, and translate them to English. Below, you can see exactly what changes we make.

1. Bebiste agua. → “You drank water.”

2. Bebiste agua hace cinco minutos. → “You drank water five minutes ago.”

In this second sentence, the only thing we added was the time the action happened, hace cinco minutos, which means “five minutes ago.”

3. Bebiste dos botellas de agua hace cinco minutos. → “You drank two bottles of water five minutes ago.”

In this third sentence, we made a bigger change. This time, what we’re drinking isn’t just water, but something slightly more specific: two bottles of water. The new object is dos botellas de agua instead of just agua.

4. ¿Bebiste dos botellas de agua hace cinco minutos? → “Did you drink two bottles of water five minutes ago?”

To end these examples, we thought it would be a good idea to show you once again how to turn an affirmative sentence into a question, to convince you that we don’t have to make any changes to it, just in case you didn’t believe us before!

8. How to Master Spanish with SpanishPod101.com

As we mentioned previously, Spanish word order is more flexible than English word order, so in some cases, if you don’t use our basic order, it might just seem as if you’re trying to emphasize some word or phrase in particular. The way we see it, it means you would have to try pretty hard to get it wrong! When learning a foreign language, this is exactly the kind of motivation you need.

For more information on Spanish word order, SpanishPod101.com has another short lesson on this as well! If you want to get a better understanding of Spanish grammar in general, also check out our relevant page.

No matter what your level is, give us a try and learn Spanish! From beginner to advanced, here you’ll find everything you need.

Before you go, let us know in the comments if there’s anything that’s still not clear about Spanish word order. We’ll do our best to help you out!

Spanish is a grammatically inflected language, which means that many words are modified («marked») in small ways, usually at the end, according to their changing functions. Verbs are marked for tense, aspect, mood, person, and number (resulting in up to fifty conjugated forms per verb). Nouns follow a two-gender system and are marked for number. Personal pronouns are inflected for person, number, gender (including a residual neuter), and a very reduced case system; the Spanish pronominal system represents a simplification of the ancestral Latin system.

Frontispiece of the Grammatica Nebrissensis

Spanish was the first of the European vernaculars to have a grammar treatise, Gramática de la lengua castellana, published in 1492 by the Andalusian philologist Antonio de Nebrija and presented to Queen Isabella of Castile at Salamanca.[1]

The Real Academia Española (RAE, Royal Spanish Academy) traditionally dictates the normative rules of the Spanish language, as well as its orthography.

Differences between formal varieties of Peninsular and American Spanish are remarkably few, and someone who has learned the language in one area will generally have no difficulties of communication in the other; however, pronunciation does vary, as well as grammar and vocabulary.

Recently published comprehensive Spanish reference grammars in English include DeBruyne (1996), Butt & Benjamin (2011), and Batchelor & San José (2010).

Verbs[edit]

Every Spanish verb belongs to one of three form classes, characterized by the infinitive ending: -ar, -er, or -ir—sometimes called the first, second, and third conjugations, respectively.

A Spanish verb has nine indicative tenses with more-or-less direct English equivalents: the present tense (‘I walk’), the preterite (‘I walked’), the imperfect (‘I was walking’ or ‘I used to walk’), the present perfect (‘I have walked’), the past perfect — also called the pluperfect (‘I had walked’), the future (‘I will walk’), the future perfect (‘I will have walked’), the conditional simple (‘I would walk’) and the conditional perfect (‘I would have walked’).

In most dialects, each tense has six potential forms, varying for first, second, or third person and for singular or plural number. In the second person, Spanish maintains the so-called «T–V distinction» between familiar and formal modes of address. The formal second-person pronouns (usted, ustedes) take third-person verb forms.

The second-person familiar plural is expressed in most of Spain with the pronoun vosotros and its characteristic verb forms (e.g., coméis ‘you [pl.] eat’), while in Latin American Spanish it merges with the formal second-person plural (e.g., ustedes comen). Thus ustedes is used as both the formal and familiar second-person pronoun in Latin America.

In many areas of Latin America (especially Central America and southern South America), the second-person familiar singular pronoun tú is replaced by vos, which frequently requires its own characteristic verb forms, especially in the present indicative, where the endings are -ás, -és, and -ís for -ar, -er, -ir verbs, respectively. See «voseo«.

In the tables of paradigms below, the (optional) subject pronouns appear in parentheses.

Present indicative[edit]

The present indicative is used to express actions or states of being in a present time frame. For example:

- Soy alto (I am tall). (Subject pronoun «yo» not required and not routinely used.)

- Ella canta en el club (She sings in the club).

- Todos nosotros vivimos en un submarino amarillo (We all live in a yellow submarine).

- Son las diez y media ([It] is ten thirty).

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| First person | (yo) hablo | (nosotros/-as) hablamos |

| Second person familiar | (tú) hablas (vos) hablás/habláis |

(vosotros/-as) habláis |

| Second person formal | (usted) habla | (ustedes) hablan |

| Third person | (él, ella) habla | (ellos, ellas) hablan |

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| First person | (yo) como | (nosotros/-as) comemos |

| Second person familiar | (tú) comes (vos) comés/coméis |

(vosotros/-as) coméis |

| Second person formal | (usted) come | (ustedes) comen |

| Third person | (él, ella) come | (ellos, ellas) comen |

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| First person | (yo) vivo | (nosotros/-as) vivimos |

| Second person familiar | (tú) vives (vos) vivís |

(vosotros/-as) vivís |

| Second person formal | (usted) vive | (ustedes) viven |

| Third person | (él, ella) vive | (ellos, ellas) viven |

Past tenses[edit]

Spanish has a number of verb tenses used to express actions or states of being in a past time frame. The two that are «simple» in form (formed with a single word, rather than being compound verbs) are the preterite and the imperfect.

Preterite[edit]

The preterite is used to express actions or events that took place in the past, and which were instantaneous or are viewed as completed. For example:

- Ella se murió ayer (She died yesterday)

- Pablo apagó las luces (Pablo turned the lights off)

- Yo me comí el arroz (I ate the rice)

- Te cortaste el pelo (You had your hair cut, Lit. «You cut yourself the hair»)

| Singular | Plural | |