Word-formation

is the system of derivative types of words and the process of

creating new words from material, available in the language after

certain structural and semantic formulas and patterns. A distinction

is made between two principal types of word-formation:

word-derivation

and word-composition.

The basic ways of forming words in word derivation are affixation

and conversion.

Affixation is the formation of a new word with the help of affixes

(f.e.

heartless; overdo).

Conversion is the formation of a new word by bringing a stem of this

word into a different formal paradigm (f.e.

a private, to paper).

The basic form of the original and the basic form of the derived

words are homonymous.

Affixation

– the addition of the affix, is a a basic means of forming words in

English. It has been productive in all periods of the history of

English.

Linguists

distinguish three types of affixes: 1. An affix that is attached to

the front of its base is called a prefix,

whereas 2. an affix attached to the end of the base is called a

suffix.

Both

types of affix occur in English Far less common than prefixes or

suffixes infixes

— a type of affix that occurs within a base of a word to express

such notions as tense,

number,

or gender.

English has no system of infixes.

In

Modern English suffixation is characteristic of noun and adjective

formation, while prefixation is typical of verb formation. As a rule

prefixes modify the lexical meaning of stems to which they are added.

The prefixes of derivatives usually join the part of speech the

unprefixed word belongs: usual

– unusual.

The

suffix does not only modify the lexical meaning of the stem it is

added to, but the word itself is usually transferred to another part

of speech: e.g. care-careless.

The

process of affixation consists in coining a new word by adding an

affix or several affixes to some root-morpheme. Affixation is

generally defined as the formation of word by adding derivational

affixes to different types of bases.

Suffixes

and prefixes may be classified along different lines. The logical

classification of suffixes is according to:

-

their

origin: from etymological point of view suffixes are subdivided

into 2 main classes:

native

(-er, -ness, -dom) and borrowed

(latin: -ant,-ent,-ible,-able; romanic: -age,-ment,-tion; greek:

-ist,-ism,-ism).

-

meaning:

-er – doer of the action: worker;-

ess

– denote gender: lion-lioness; -

-ence/-ance

– abstract meaning: importance; -

-dom

+ -age – collectivity: kingdom.etc.

-

-

Suffixes

part of speech they form:-

noun-forming

suffixes: -er, -ness, -ment, -th, -hood, -ing. -

Adjective-forming

suffixes: -ful, -less, -y, -ish, -en, -ly. -

Verb-forming

suffixes: -en (redden, darken)

-

4.

Productivity. By productive suffixes we mean the ability of being

used to form new occasional or potential words which take part in

deriving new words in this particular

period of languge development.

The

best way to identify productive affixes is to look for them among

neologisms.

Well most productive suffixes are: noun forming — -er,

-ness, -ing, -ism, -ist, -ance, -ancy;

adjective forming — -ish,

-able, -ion, -edd, -less;

adverb forming — -ly;

verb

forming — -ize,

-ise, -ate. By

non-productive affixes

we mean affixes which are not able to form new words in the period in

question. Non-productive affixes are recognized as separate morphemes

and posess clear-cut semantic characteristics. ( non-productive

suffixes are: noun forming —

-hood, -ship, adjective

forming — —ful,

-some,

verb forming — —en.

An

affix may lose its productivity and then become productive again in

the process of word formation. For ex. non-prod. noun forming

suffixes –dom,

-ship

centuries ago were considered as productive. The adjective forming

suffix –ish

which

leaves no doubt

to

its productivity nowadays has regained it after having been

non-prod. for many centuries. The productivity of an affix shouldn’t

be confused with its frequency of occurrence. The frequency of

occurrence is understood as the existence in the vocabulary of a

great number of words containing an affix in question. An affix may

occur in hundreds of words but if it isn’t used to form new words

it isn’t productive. For ex. adjective forming suffix –ful

(beautiful,

trustful) is met in hundreds of adjectives but no new words seem to

be built with its help. So it’s non-productive.

The

logical classification of prefixes. They are characterized according

their origin-native and borrowed. 1) be-, mis-(name), un-(selfish),

over-(do). 2) latin – pre-, ultra. Greec – anti-, sym. French –

en-. Also they classified according their meaning. 1)negative (in,

mis, un, non). 2)pr of time and order (after, post, proto) 3)pr of

repetitions (re) 4)location (extra, trance, super). 4)size and degree

meaning (mega, super, ultra). The main а

ща

зк

is to change the lexical meaning.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Affixation is the morphological process in by which bound morphemes are attached to a roots or stems to mark changes in meaning, part of speech, or grammatical relationships. Affixes take on several forms and serve different functions. In this tutorial, we will be looking specifically at affixation in Standard English.

Affixes

An affix is a bound morpheme that attaches to a root or stem to form a new word, or a variant form of the same word. In English we primarily see 2 types. Prefixes precede the root or stem, e.g., re-cover, while suffixes follow, e.g., hope-ful. A third type of affix known as a circumfix occurs in the two words en-ligh-en and em-bold-en, where the prefix en/m– and the suffix –en/m are attached simultaneously to the root.

There are those who claim that infixation is also used as an emphasis marker in colloquial English. This occurs when an expletive is inserted into the internal structure of a word, e.g., un-fricking-believable.

Derivational affixes derive new words by altering the definitional meaning or the grammatical category of a word, whereas inflectional affixes show grammatical relationships between words or grammatical contrast. In English, both prefixes and suffixes can be derivational, but only suffixes can be inflectional.

Prefixes

Prefixes are abundant in English. Some are more commonly used (productive) than others. As mentioned above, prefixes are only used to derive new meaning or part of speech. Below is a list of those that are more common.

Table 1 Commonly used prefixes in English Click Photo for Large View

Suffixes

Suffixes can either be derivational or inflectional. Below is a list of common derivational suffixes.

Table 2 Commonly used derivational suffixes in English Click Photo for Large View

In English there are 8 inflectional suffixes. As you will see, these are limited to showing some type of grammatical function.

Table 3 Inflectional suffixes in English Click Photo for Large View

You may have noticed that -er appears as both a derivational and inflectional morpheme. Although they share phonological form, they are two separate morphemes, having 2 separate functions and must not be confused. -er attached to a verb causes the derivation: verb noun, e.g., write writer. -er attached to an adjective shows inflection, i.e., the comparative form of an adjective: nice nicer. This is also true for –ing and –en. A verb + -ing can derive a noun or inflect a verb for past or present progressive.

(1)

set + ing = noun

The setting of the sun was covered by clouds.

set + ing + progressive verb

I was setting the table when the phone rang.

verb + -en = past participle (freeze + en)

The low temperatures had frozen all the crops.

noun + -en = verb (light + en)

Mary decided to lighten her hair.

Infixes

There is question as to whether the limited usage of infixation in English actually a morphological process since the word being inserted is not itself an infix, as it is free-standing and not a bound morpheme. Furthermore, there is no resulting derivation or inflection.

Only expletives are used as infixes and in only a limited number of words. For example, infixes are only permitted when the expletive is flanked by stress. This means that only words with initial stress (trochees and not iambs) will be candidates for infixation.

(2)

un-expletive-believable but *unbe-expletive-lievable

Clitics

Clitics are unstressed reduced units of meaning that attached to a limited number of host words. They generally are not considered a type of affix since they do not meet specific minimal phonological requirements (which will not be discussed here). Proclitics attach to the beginning of a root, e.g., ‘tis for ‘it is’, ‘dyou for ‘do you’. Enclitics are attached word finally, e.g., what’s for ‘what is’.

Rules of Formation

Although a speaker may generally count on intuition in forming complex words in terms of which affixes may be attached to which roots, underlying rules of word-formation actually account for the process. Our intuition allows us to attach ‘un-‘ to ‘productive’ but not to ‘fish’. We can attach the suffix ‘-ly’ to ‘kind’ but not to ‘sky’.

(3)

un + ‘productive’ but not *un + ‘fish’

‘kind’ + ly *’sky’ + ly

This distribution of affixes leads us to believe that there are rules of word-formation to which we intuitively adhere. So let’s break this down.

Productivity

Certain affixes are more productive than others, meaning that they can be added to a large number of words without obstructing meaning. An example of a productive suffix in English would be –ness which we regularly use to derive nouns from adjectives.

(4)

adjective + ness = noun

happy + ness = ‘happiness’

In fact, some affixes are so productive that they can be attached to almost any stem creating nonce words in which meaning is transparent. Take –ish for example in English. This suffix can be attached to almost any noun or adjective to communicate like –ness. If a soup broth is not thick, it could be described as ‘thin’-ish and there would be no ambiguity as to this non-word’s meaning. All listeners would agree on the interpretation of ‘thin’-ish.

Unproductive morphemes, on the other hand, are not frequently used. An example would be the suffix –th as in ‘warmth’.

(5)

adjective + –th = noun

‘warm’ + –th = ‘warmth’

-th can only be attached to a small number of words. No English speaker would consider using the word ‘thinth’ to describe soup broth that is not thick.

So back to rules.

As we have seen, there are rules that govern the process of affixation (3). Furthermore, we know that when specific suffixes are attached to one part of speech, they derive another.

–ly will derive an adverb from an adjective.

(6)

adjective + –ly = adverb

‘calm’ + –ly = ‘calmly’

We can also use –ly with a limited number of nouns to derive adjectives.

(7)

noun + –ly = adjective

‘matron’ +-ly = ‘matronly’

‘friend’ + –ly = ‘friendly’

‘love’ + –ly = ‘lovely’

However this is not possible with verbs.

(8)

*verb +-ly = adverb/adjective

*’walk’ + –ly = adverb

Thus we can claim:

1. adjective + –ly = adverb

2. noun + –ly = adjective

Let’s look again at ‘-ness‘. This suffix can be attached to adjectives but not to nouns or verbs.

Let’s look again at –ness. This suffix can be attached to adjectives but not to nouns or verbs.

(9)

adjective + –ness = noun

‘sweet’ + –ness = ‘sweetness’

‘tender’ + —ness = ‘tenderness’

*noun + —ness = noun (or anything)

*‘house’ + —ness = ‘houseness’

*verb + –ness = noun (or anything)

*’study’ + –ness = ‘studiness’

Prefixes in English do not generally change the grammatical category of a word, but rather meaning. Even so, there are still rules as to how they are distributed.

Un- may combine with adjectives and certain verbs, but not with nouns or adverbs.

(10)

u–n + ‘friendly’ = ‘unfriendly’

un– + ‘do’ = ‘undo’

but not

* un– + ‘computer’ = ‘uncomputer’

* un– + ‘very’ = ‘unvery’

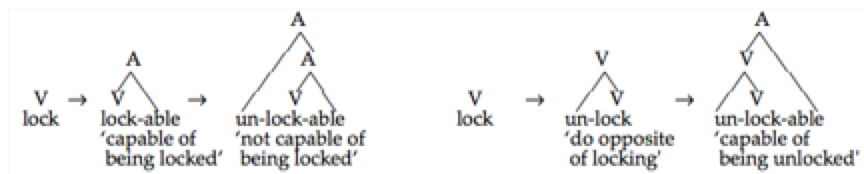

In addition, to these distributional constraints, we will see that there is an order in which affixes must be combined with roots and stems. For instance, the word ‘unbelievable’ must be built by attaching –able to ‘believe’, deriving ‘believable’, and then add un– to derive ‘unbelievable’. We cannot add un– to ‘believe’ and then –able to ‘unbelieve.’ Even though the outcome seems to be the same, the meaning derived from the different rule orderings is not. This is due to the fact that un- generally attaches to an adjective and not a verb. That’s why ‘unbelieve’ is not a word to which an affix may be added.

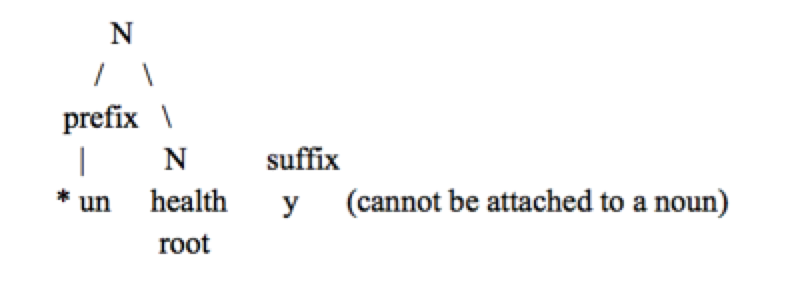

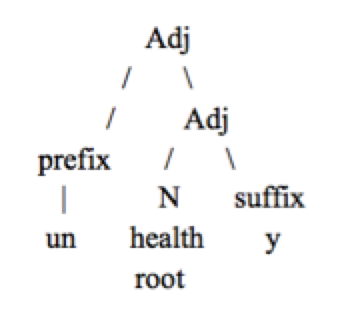

This requirement for an ordered application of affixes is referred to as the hierarchal structure of derived words, which is shown by tree diagrams. These tree structures demonstrate the steps to adding multiple affixes to a root and how each addition may create a new word form. Below is an example of a diagram.

(11)

Click Photo for Large View

We see in (11) that the result of attaching un– to a noun root yields an ungrammatical structure. Furthermore, we cannot add –y to a noun. This derivation fails. However we see in (12) that when -y is attached to a noun, it yields an adjective. Now un– can be attached to an adjective. This derivation results in a grammatical structure.

Click Photo for Large View

(12)

Constructions such as (11 and 12) demonstrate an unambiguous word-formation. This means that the ordering of affixes is clear. There are, however, morphologically complex words in which two orders are possible with meaning being dependent upon the ordering. In (13), the first construction shows –able attaching to the verb root, resulting in the adjective ‘lockable’ to which un– is added, deriving an adjective with the opposite meaning: ‘not capable of being locked’. In the second diagram un– is first added to the verb root resulting in the verb ‘unlock’ to which –able can be attached resulting in an adjective meaning ‘capable of being unlocked’. The formation of the morphologically complex word ‘unlockable’ is ambiguous since both orderings of affixes result in a grammatical structure.

(13)

Click Photo for Large View

As you can see, it is crucial to be well-acquainted with the parts of speech and rules of formation. For practice, visit our self-correcting morphology exercises.

R. Aronow

[1] We use the term root as a bare, simple word that has not undergone any morphological processes, e.g., read. Stem refers to a morphologically complex word, i.e., 2 or more morphemes, to which additional morphemes may be attached, e.g., reread rereading.

Back to Morphology Tutorials

Amazement, Quickly, Impossible, Intergalactic. What do all of these words have in common? The answer is that they all contain affixes. Read on to learn all about affixes in English, the different examples of affixes, and the affixation process.

Affixation Linguistics Definition

What is the definition of affixation? We see the meaning of affixation as a morphological process whereby a group of letters (the affix) is attached to a base or root word to form a new word. Sometimes the new word takes on a whole new meaning, and sometimes it simply gives us more grammatical information.

For example, adding the affix ‘-s’ to the end of the word ‘apple’ tells us there is more than one apple.

Morphological process — Changing or adding to a root word to create a more suitable word for the context.

Affixes are a type of bound morpheme — this means they cannot stand alone and must appear alongside a base word to get their meaning. Take a look at an example of affixes below:

On its own, the affix ‘-ing’ doesn’t really mean anything. However, placing it at the end of a base word, such as ‘walk’ to create the word ‘walking,’ lets us know that the action is progressive (ongoing).

Understanding the meaning and usage of affixes can help us ‘decipher’ the meaning of unknown words.

There are three types of affixes: prefixes, suffixes, and circumfixes. Let’s take a closer look at these now.

Types of Affixation

To begin, let’s look at the different types of affixes that we can add to a base word. The two main types of affixation are suffixes and prefixes, and the third, less common, are circumfixes. We have compiled some examples of affixation and their types for you to check out below!

Prefixes

Prefixes are affixes that go at the beginning of a base word. Prefixes are very common in the English language, and thousands of English words contain a prefix. Common English prefixes include in-, im-, un-, non-, and re-.

Prefixes are commonly used to make based words negative/positive (e.g., unhelpful) and to express relations of time (e.g., prehistoric), manner (e.g., underdeveloped), and place (e.g., extraterrestrial).

Here are some common English words with prefixes:

- impolite

- autobiography

- hyperactive

- irregular

- midnight

- outrun

- semicircle

A more complete list of all English prefixes can be found towards the end of this explanation!

Prefixes and Hyphens (-)

Unfortunately, there aren’t any set rules as to when you should use a hyphen (-) with a prefix; however, there are a few guidelines you can follow to help you decide when to use a hyphen.

- If the prefixed word can easily be confused with another existing word, e.g., re-pair and repair (to pair again and to fix something)

- If the prefix ends in a vowel and the base word begins with a vowel, e.g., anti-intellectual

- If the base word is a proper noun and should be capitalized, e.g., un-American

- When using dates and numbers, e.g., mid-century, pre-1940s

Suffixes

Whereas prefixes go at the beginning of a base word, suffixes go at the end. Common suffixes include -full, -less, -ed, -ing, -s, and -en.

When we add suffixes to base words, the affixation process is either derivational or inflectional. So, what exactly does that mean?

When the word’s meaning or the word class (e.g., noun, adjective, verb, etc.) completely changes, the process is derivational. For example, adding ‘-er’ to the end of the based word ‘teach’ changes the verb (teach) to a noun (teacher).

Derivational affixes are one the most common ways new words are formed in English!

Some examples of words with derivational suffixes include:

- laughable (changes the verb laugh to an adjective)

- joyous (changes the abstract noun joy to an adjective)

- quickly (changes the adjective quick to an adverb)

On the other hand, inflectional suffixes show a grammatical change within a word class — this means the word class always remains the same. For example, adding the suffix ‘-ed’ to the verb ‘talk’ to create the verb ‘talked’ shows us that the action happened in the past.

Some example words with inflectional suffixes include:

- walking (shows the progressive aspect)

- shoes (shows plurality)

- likes (shows 3rd person singular, e.g., he likes coffee)

- taller (a comparative adjective)

- tallest (a superlative adjective)

- eaten (shows the perfect aspect)

Circumfixes

In affixation, circumfixes are less common than prefixes and affixes and typically involve adding affixes to both the beginning and the end of a base word.

- enlighten

- unattainable

- incorrectly

- inappropriateness

Examples of Affixation

Here are several useful tables outlining examples of affixation, with some of English’s most common prefixes and suffixes:

Prefixes

| Prefix | Meaning | Examples |

| anti- | against or opposite | antibiotics, antiestablishment |

| de- | removal | de-iced, decaffeinated |

| dis- | negation or removal | disapprove, disloyal |

| hyper- | more than | hyperactive, hyperallergic |

| inter- | between | interracial, intergalactic |

| non- | absence or negation | nonessential, nonsense |

| post- | after a period of time | post-war |

| pre- | before a period of time | pre-war |

| re- | again | reapply, regrow, renew |

| semi- | half | semicircle, semi-funny |

Derivational Suffixes Forming Nouns

| Suffix | Original word | New word |

| -er | drive | driver |

| -cian | diet | dietician |

| -ness | happy | happiness |

| -ment | govern | government |

| -y | jealous | jealousy |

Derivational Suffixes Forming Adjectives

| Suffix | Original word | New word |

| -al | President | Presidential |

| -ary | exemplar | exemplary |

| -able | debate | debatable |

| -y | butter | buttery |

| -ful | resent | resentful |

Derivational Suffixes Forming Adverbs

| Suffix | Original word | New word |

| -ly | slow | slowly |

Derivational Suffixes Forming verbs

| Suffix | Original word | New word |

| -ize | apology | apologize |

| -ate | hyphen | hyphenate |

Rules for Affixation

There aren’t any rules for which words can go through the affixation process. Language is an ever-evolving and developing thing created by the people, and, as we previously mentioned, adding affixes is one of the most common ways new words enter the English dictionary.

However, there are few rules regarding the affixation process. Let’s take a look at some examples of affixation rules now.

The Affixation Process

What is the affixation process? When we add affixes to a base word, there are a few guidelines regarding spelling that should be followed. Most of these rules and examples of affixes apply to adding suffixes and making plurals (a type of suffix).

Suffixes

-

Double the final constant when it comes after and before a vowel, e.g., running, hopped, funny.

-

Drop the ‘e’ at the end of the base word if the suffix begins with a vowel, e.g., closable, using, adorable

-

Change a ‘y’ to an ‘i’ before adding the suffix if a consonant comes before the ‘y’, e.g., happy —> happiness.

-

Change ‘ie’ to ‘y’ when the suffix is ‘-ing,’ e.g., lie —> lying.

The most common way to show the plurality of nouns is to add the suffix ‘-s’; however, we add ‘-es’ when the base word ends in -s, -ss, -z, -ch, -sh, and -x, e.g., foxes, buses, lunches.

Remember that not all words will follow these rules — this is the English language, after all!

Why not have a go at affixation yourself? You never know; your new word could end up in The Oxford English Dictionary one day.

Affixation — Key Takeaways

- Affixation is a morphological process, meaning letters (affixes) are added to a base word to form a new word.

- Affixes are a type of bound morpheme — this means they cannot stand alone and must appear alongside a base word to get their meaning.

- The main types of affixes are prefixes, suffixes, and circumfixes.

- Prefixes go at the beginning of a base word, suffixes go at the end, and circumfixes go at the beginning and the end.

- Suffixes can be either derivational (meaning they create a new word class) or inflectional (meaning they express grammatical function).

Lecture 3. Word-building: affixation, conversion, composition, abbreviation. THE WORD-BUILDING SYSTEM OF ENGLISH 1. Word-derivation 2. Affixation 3. Conversion 4. Word-composition 5. Shortening 6. Blending 7. Acronymy 8. Sound interchange 9. Sound imitation 10. Distinctive stress 11. Back-formation Word-formation is a branch of Lexicology which studies the process of building new words, derivative structures and patterns of existing words. Two principle types of wordformation are distinguished: word-derivation and word-composition. It is evident that wordformation proper can deal only with words which can be analyzed both structurally and semantically. Simple words are closely connected with word-formation because they serve as the foundation of derived and compound words. Therefore, words like writer, displease, sugar free, etc. make the subject matter of study in word-formation, but words like to write, to please, atom, free are irrelevant to it. WORD-FORMATION WORD-DERIVATION AFFIXATION WORD-COMPOSITION CONVERSION 1. Word-derivation. Speaking about word-derivation we deal with the derivational structure of words which basic elementary units are derivational bases, derivational affixes and derivational patterns. A derivational base is the part of the word which establishes connection with the lexical unit that motivates the derivative and determines its individual lexical meaning describing the difference between words in one and the same derivative set. For example, the individual lexical meaning of the words singer, writer, teacher which denote active doers of the action is signaled by the lexical meaning of the derivational bases: sing-, write-, teach-. Structurally derivational bases fall into 3 classes: 1. Bases that coincide with morphological stems of different degrees оf complexity, i.e., with words functioning independently in modern English e.g., dutiful, day-dreamer. Bases are functionally and semantically distinct from morphological stems. Functionally the morphological stem is a part of the word which is the starting point for its forms: heart – hearts; it is the part which presents the entire grammatical paradigm. The stem remains unchanged throughout all word-forms; it keeps them together preserving the identity of the word. A derivational base is the starting point for different words (heart – heartless – hearty) and its derivational potential outlines the type and scope of existing words and new creations. Semantically the stem stands for the whole semantic structure of the word; it represents all its lexical meanings. A base represents, as a rule, only one meaning of the source word. 2. Bases that coincide with word-forms, e.g., unsmiling, unknown. The base is usually represented by verbal forms: the present and the past participles. 3. Bases that coincide with word-groups of different degrees of stability, e.g., blue-eyed, empty-handed. Bases of this class allow a rather limited range of collocability, they are most active with derivational affixes in the class of adjectives and nouns (long-fingered, blue-eyed). Derivational affixes are Immediate Constituents of derived words in all parts of speech. Affixation is generally defined as the formation of words by adding derivational affixes to different types of bases. Affixation is subdivided into suffixation and prefixation. In Modern English suffixation is mostly characteristic of nouns and adjectives coining, while prefixation is mostly typical of verb formation. A derivational pattern is a regular meaningful arrangement, a structure that imposes rigid rules on the order and the nature of the derivational base and affixes that may be brought together to make up a word. Derivational patterns are studied with the help of distributional analysis at different levels. Patterns are usually represented in a generalized way in terms of conventional symbols: small letters v, n, a, d which stand for the bases coinciding with the stems of the respective parts of speech: verbs, etc. Derivational patterns may represent derivative structure at different levels of generalization: - at the level of structural types. The patterns of this type are known as structural formulas, all words may be classified into 4 classes: suffixal derivatives (friendship) n + -sf → N, prefixal derivatives (rewrite), conversions (a cut, to parrot) v → N, compound words (musiclover). - at the level of structural patterns. Structural patterns specify the base classes and individual affixes thus indicating the lexical-grammatical and lexical classes of derivatives within certain structural classes of words. The suffixes refer derivatives to specific parts of speech and lexical subsets. V + -er = N (a semantic set of active agents, denoting both animate and inanimate objects - reader, singer); n + -er = N (agents denoting residents or occupations Londoner, gardener). We distinguish a structural semantic derivationa1 pattern. - at the level of structural-semantic patterns. Derivational patterns may specify semantic features of bases and individual meaning of affixes: N + -y = A (nominal bases denoting living beings are collocated with the suffix meaning "resemblance" - birdy, catty; but nominal bases denoting material, parts of the body attract another meaning "considerable amount" - grassy, leggy). The basic ways of forming new words in word-derivation are affixation and conversion. Affixation is the formation of a new word with the help of affixes (heartless, overdo). Conversion is the formation of a new word by bringing a stem of this word into a different paradigm (a fall from to fall). 2. Affixation Affixation is generally defined as the formation of words by adding derivational affixes to different types of bases. Affixation includes suffixation and prefixation. Distinction between suffixal and prefixal derivates is made according to the last stage of derivation, for example, from the point of view of derivational analysis the word unreasonable – un + (reason- + -able) is qualified as a prefixal derivate, while the word discouragement – (dis- + -courage) + -ment is defined as a suffixal derivative. Suffixation is the formation of words with the help of suffixes. Suffixes usually modify the lexical meaning of the base and transfer words to a different part of speech. Suffixes can be classified into different types in accordance with different principles. According to the lexico-grammatical character suffixes may be: deverbal suffixes, e.d., those added to the verbal base (agreement); denominal (endless); deadjectival (widen, brightness). According to the part of speech formed suffixes fall into several groups: noun-forming suffixes (assistance), adjective-forming suffixes (unbearable), numeral-forming suffixes (fourteen), verb-forming suffixes (facilitate), adverb-forming suffixes (quickly, likewise). Semantically suffixes may be monosemantic, e.g. the suffix –ess has only one meaning “female” – goddess, heiress; polysemantic, e.g. the suffix –hood has two meanings “condition or quality” falsehood and “collection or group” brotherhood. According to their generalizing denotational meaning suffixes may fall into several groups: the agent of the action (baker, assistant); collectivity (peasantry); appurtenance (Victorian, Chinese); diminutiveness (booklet). Prefixation is the formation of words with the help of prefixes. Two types of prefixes can be distinguished: 1) those not correlated with any independent word (un-, post-, dis-); 2) those correlated with functional words (prepositions or preposition-like adverbs: out-, up-, under-). Diachronically distinction is made between prefixes of native and foreign origin. Prefixes can be classified according to different principles. According to the lexico-grammatical character of the base prefixes are usually added to, they may be: deverbal prefixes, e.d., those added to the verbal base (overdo); denominal (unbutton); deadjectival (biannual). According to the part of speech formed prefixes fall into several groups: noun-forming prefixes (ex-husband), adjective-forming prefixes (unfair), verb-forming prefixes (dethrone), adverb-forming prefixes (uphill). Semantically prefixes may be monosemantic, e.g. the prefix –ex has only one meaning “former” – ex-boxer; polysemantic, e.g. the prefix –dis has four meanings “not” disadvantage and “removal of” to disbrunch. According to their generalizing denotational meaning prefixes may fall into several groups: negative prefixes – un, non, dis, a, in (ungrateful, nonpolitical, disloyal, amoral, incorrect); reversative prefixes - un, de, dis (untie, decentralize, disconnect); pejorative prefixes – mis, mal, pseudo (mispronounce, maltreat, pseudo-scientific); prefix of repetition (redo), locative prefixes – super, sub, inter, trans (superstructure, subway, intercontinental, transatlantic). 3. Conversion Conversion is a process which allows us to create additional lexical terms out of those that already exist, e.g., to saw, to spy, to snoop, to flirt. This process is not limited to one syllable words, e.g., to bottle, to butter, nor is the process limited to the creation of verbs from nouns, e.g., to up the prices. Converted words are extremely colloquial: "I'll microwave the chicken", "Let's flee our dog", "We will of course quiche and perrier you". Conversion came into being in the early Middle English period as a result of the leveling and further loss of endings. In Modern English conversion is a highly-productive type of word-building. Conversion is a specifically English type of word formation which is determined by its analytical character, by its scarcity of inflections and abundance of mono-and-de-syllabic words in different parts of speech. Conversion is coining new words in a different part of speech and with a different distribution but without adding any derivative elements, so that the original and the converted words are homonyms. Structural Characteristics of Conversion: Mostly monosyllabic words are converted, e.g., to horn, to box, to eye. In Modern English there is a marked tendency to convert polysyllabic words of a complex morphological structure, e.g., to e-mail, to X-ray. Most converted words are verbs which may be formed from different parts of speech from nouns, adjectives, adverbs, interjections. Nouns from verbs - a try, a go, a find, a loss From adjectives - a daily, a periodical From adverbs - up and down From conjunctions - but me no buts From interjection - to encore Semantic Associations / Relations of Conversion: The noun is the name of a tool or implement, the verb denotes an action performed by the tool, e.g., to nail, to pin, to comb, to brush, to pencil; The noun is the name of an animal, the verb denotes an action or aspect of behavior considered typical of this animal, e.g., to monkey, to rat, to dog, to fox; When the noun is the name of a part of a human body, the verb denotes an action performed by it, e.g., to hand, to nose, to eye; When the noun is the name of a profession or occupation, the verb denotes the activity typical of it, e.g., to cook, to maid, to nurse; When the noun is the name of a place, the verb will denote the process of occupying the place or by putting something into it, e.g., to room, to house, to cage; When the word is the name of a container, the verb will denote the act of putting something within the container, e.g., to can, to pocket, to bottle; When the word is the name of a meal, the verb means the process of taking it, e.g., to lunch, to supper, to dine, to wine; If an adjective is converted into a verb, the verb may have a generalized meaning "to be in a state", e.g., to yellow; When nouns are converted from verbs, they denote an act or a process, or the result, e.g., a try, a go, a find, a catch. 4. Word-composition Compound words are words consisting of at least two stems which occur in the language as free forms. Most compounds in English have the primary stress on the first syllable. For example, income tax has the primary stress on the in of income, not on the tax. Compounds have a rather simple, regular set of properties. First, they are binary in structure. They always consist of two or more constituent lexemes. A compound which has three or more constituents must have them in pairs, e.g., washingmachine manufacturer consists of washingmachine and manufacturer, while washingmachine in turn consists of washing and machine. Compound words also usually have a head constituent. By a head constituent we mean one which determines the syntactic properties of the whole lexeme, e.g., the compound lexeme longboat consists of an adjective, long and a noun, boat. The compound lexeme longboat is a noun, and it is а noun because boat is a noun, that is, boat is the head constituent of longboat. Compound words can belong to all the major syntactic categories: • Nouns: signpost, sunlight, bluebird, redwood, swearword, outhouse; • Verbs: window shop, stargaze, outlive, undertake; • Adjectives: ice-cold, hell-bent, undersized; • Prepositions: into, onto, upon. From the morphological point of view compound words are classified according to the structure of immediate constituents: • Compounds consisting of simple stems - heartache, blackbird; • Compounds where at least one of the constituents is a derived stem -chainsmoker, maid-servant, mill-owner, shop-assistant; • Compounds where one of the constituents is a clipped stem - V-day, A-bomb, Xmas, H-bag; • Compounds where one of the constituents is a compound stem - wastes paper basket, postmaster general. Compounds are the commonest among nouns and adjectives. Compound verbs are few in number, as they are mostly the result of conversion, e.g., to blackmail, to honeymoon, to nickname, to safeguard, to whitewash. The 20th century created some more converted verbs, e.g., to weekend, to streamline,, to spotlight. Such converted compounds are particularly common in colloquial speech of American English. Converted verbs can be also the result of backformation. Among the earliest coinages are to backbite, to browbeat, to illtreat, to housekeep. The 20th century gave more examples to hitch-hike, to proof-read, to mass-produce, to vacuumclean. One more structural characteristic of compound words is classification of compounds according to the type of composition. According to this principle two groups can be singled out: words which are formed by a mere juxtaposition without any connecting elements, e.g., classroom, schoolboy, heartbreak, sunshine; composition with a vowel or a consonant placed between the two stems. e.g., salesman, handicraft. Semantically compounds may be idiomatic and non-idiomatic. Compound words may be motivated morphologically and in this case they are non-idiomatic. Sunshine - the meaning here is a mere meaning of the elements of a compound word (the meaning of each component is retained). When the compound word is not motivated morphologically, it is idiomatic. In idiomatic compounds the meaning of each component is either lost or weakened. Idiomatic compounds have a transferred meaning. Chatterbox - is not a box, it is a person who talks a great deal without saying anything important; the combination is used only figuratively. The same metaphorical character is observed in the compound slowcoach - a person who acts and thinks slowly. The components of compounds may have different semantic relations. From this point of view we can roughly classify compounds into endocentric and exocentric. In endocentric compounds the semantic centre is found within the compound and the first element determines the other as in the words filmstar, bedroom, writing-table. Here the semantic centres are star, room, table. These stems serve as a generic name of the object and the determinants film, bed, writing give some specific, additional information about the objects. In exocentric compound there is no semantic centre. It is placed outside the word and can be found only in the course of lexical transformation, e.g., pickpocket - a person who picks pockets of other people, scarecrow an object made to look like a person that a farmer puts in a field to frighten birds. The Criteria of Compounds As English compounds consist of free forms, it's difficult to distinguish them from phrases, because there are no reliable criteria for that. There exist three approaches to distinguish compounds from corresponding phrases: Formal unity implies the unity of spelling solid spelling, e.g., headmaster; with a hyphen, e.g., head-master; with a break between two components, e.g., head master. Different dictionaries and different authors give different spelling variants. Phonic principal of stress Many compounds in English have only one primary stress. All compound nouns are stressed according to this pattern, e.g., ice-cream, ice cream. The rule doesn't hold with adjectives. Compound adjectives are double-stressed, e.g., easy-going, new-born, sky-blue. Stress cannot help to distinguish compounds from phrases because word stress may depend on phrasal stress or upon the syntactic function of a compound. Semantic unity Semantic unity means that a compound word expresses one separate notion and phrases express more than one notion. Notions in their turn can't be measured. That's why it is hard to say whether one or more notions are expressed. The problem of distinguishing between compound words and phrases is still open to discussion. According to the type of bases that form compounds they can be of : 1. compounds proper – they are formed by joining together bases built on the stems or on the ford-forms with or without linking element, e.g., door-step; 2. derivational compounds – by joining affixes to the bases built on the word-groups or by converting the bases built on the word-groups into the other parts of speech, e.g., longlegged → (long legs) + -ed, a turnkey → (to turn key) + conversion. More examples: do-gooder, week-ender, first-nighter, house-keeping, baby-sitting, blue-eyed blond-haired, four-storied. The suffixes refer to both of the stems combined, but not to the final stem only. Such stems as nighter, gooder, eyed do not exist. Compound Neologisms In the last two decades the role of composition in the word-building system of English has increased. In the 60th and 70th composition was not so productive as affixation. In the 80th composition exceeded affixation and comprised 29.5 % of the total number of neologisms in English vocabulary. Among compound neologisms the two-component units prevail. The main patterns of coining the two-component neologisms are Noun stem + Noun stem = Noun; Adjective stem + Noun stem = Noun. There appeared a tendency to coin compound nouns where: The first component is a proper noun, e.g., Kirlian photograph - biological field of humans. The first component is a geographical place, e.g., Afro-rock. The two components are joined with the help of the linking vowel –o- e.g., bacteriophobia, suggestopedia. The number of derivational compounds increases. The main productive suffix to coin such compound is the suffix -er - e.g., baby-boomer, all nighter. Many compound words are formed according to the pattern Participle 2 + Adv = Adjective, e.g., laid-back, spaced-out, switched-off, tapped-out. The examples of verbs formed with the help of a post-positive -in -work-in, die-in, sleep-in, write-in. Many compounds formed by the word-building pattern Verb + postpositive are numerous in colloquial speech or slang, e.g., bliss out, fall about/horse around, pig-out. ATTENTION: Apart from the principle types there are some minor types of modern wordformation, i.d., shortening, blending, acronymy, sound interchange, sound imitation, distinctive stress, back-formation, and reduplicaton. 5. Shortening Shortening is the formation of a word by cutting off a part of the word. They can be coined in two different ways. The first is to cut off the initial/ middle/ final part: Aphaeresis – initial part of the word is clipped, e.g., history-story, telephone-phone; Syncope – the middle part of the word is clipped, e.g., madam- ma 'am; specs spectacles Apocope – the final part of the word is clipped, e.g., professor-prof, editored, vampirevamp; Both initial and final, e.g., influenza-flu, detective-tec. Polysemantic words are usually clipped in one meaning only, e.g., doc and doctor have the meaning "one who practices medicine", but doctor is also "the highest degree given by a university to a scholar or scientist". Among shortenings there are homonyms, so that one and the same sound and graphical complex may represent different words, e.g., vac - vacation/vacuum, prep — preparation/preparatory school, vet — veterinary surgeon/veteran. 6. Blending Blending is a particular type of shortening which combines the features of both clipping and composition, e.g., motel (motor + hotel), brunch (breakfast + lunch), smog (smoke + fog), telethon (television + marathon), modem , (modulator + demodulator), Spanglish (Spanish + English). There are several structural types of blends: Initial part of the word + final part of the word, e.g., electrocute (electricity + execute); initial part of the word + initial part of the word, e.g., lib-lab (liberal+labour); Initial part of the word + full word, e.g., paratroops (parachute+troops); Full word + final part of the word, e.g., slimnastics (slim+gymnastics). 7. Acronymy Acronyms are words formed from the initial letters of parts of a word or phrase, commonly the names of institutions and organizations. No full stops are placed between the letters. All acronyms are divided into two groups. The first group is composed of the acronyms which are often pronounced as series of letters: EEC (European Economic Community), ID (identity or identification card), UN (United Nations), VCR (videocassette recorder), FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation), LA (Los Angeles), TV (television), PC (personal computer), GP (General Practitioner), ТВ (tuberculosis). The second group of acronyms is composed by the words which are pronounced according to the rules of reading in English: UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization), AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome), ASH (Action on Smoking and Health). Some of these pronounceable words are written without capital letters and therefore are no longer recognized as acronyms: laser (light amplification by stimulated emissions of radiation), radar (radio detection and ranging). Some abbreviations have become so common and normal as words that people do not think of them as abbreviations any longer. They are not written in capital letters, e.g., radar (radio detection and ranging), laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) yuppie, gruppie, sinbads, dinkies. Some abbreviations are only written forms but they are pronounced as full words, e.g., Mr, Mrs, Dr. Some abbreviations are from Latin. They are used as part of the language etc. - et cetera, e.g., (for example) — exampli gratia, that is - id est. Acromymy is widely used in the press, for the names of institutions, organizations, movements, countries. It is common to colloquial speech, too. Some acronyms turned into regular words, e.g., jeep -came from the expression general purpose car. There are a lot of homonyms among acronyms: MP - Member of Parliament/Military Police/Municipal Police PC - Personal Computer/Politically correct 8. Sound-interchange Sound-interchange is the formation of a new word due to an alteration in the phonemic composition of its root. Sound-interchange falls into two groups: 1) vowel-interchange, e.g., food – feed; in some cases vowel-interchange is combined with suffixation, e.g., strong – strength; 2) consonant-interchange e.g., advice – to advise. Consonant-interchange and vowel-interchange may be combined together, e.g., life – to live. This type of word-formation is greatly facilitated in Modern English by the vast number of monosyllabic words. Most words made by reduplication represent informal groups: colloquialisms and slang, hurdy-gurdy, walkie-talkie, riff-raff, chi-chi girl. In reduplication new words are coined by doubling a stem, either without any phonetic changes as in bye-bye or with a variation of the root-vowel or consonant as in ping-pong, chit-chat. 9. Sound imitation or (onomatopoeia) It is the naming of an action or a thing by more or less exact reproduction of the sound associated with it, cf.: cock-a-do-doodle-do – ку-ка-ре-ку. Semantically, according to the source sound, many onomatopoeic words fall into the following definitive groups: 1) words denoting sounds produced by human beings in the process of communication or expressing their feelings, e.g., chatter; 2) words denoting sounds produced by animals, birds, insects, e.g., moo, buzz; 3) words imitating the sounds of water, the noise of metallic things, movements, e.g., splash, whip, swing. 10. Distinctive stress Distinctive stress is the formation of a word by means of the shift of the stress in the source word, e.g., increase – increase. 11. Back-formation Backformation is coining new words by subtracting a real or supposed suffix, as a result of misinterpretation of the structure of the existing word. This type of word-formation is not highly productive in Modern English and it is built on the analogy, e.g., beggar-to beg, cobbler to cobble, blood transfusion — to blood transfuse, babysitter - to baby-sit.

Affixation is a process which involves adding bound morphemes to roots which results in a newly-created derivative. Whereas we can distinguish many types of this process,

the English language generally makes use of two — prefixation and suffixation. The first is characterised by adding a morpheme that is placed before the base: mature — premature, do — undo, affirm — reaffirm, function — malfunction. In contrast, suffixation focuses on attaching a morpheme that rather follows the base than proceeds it: read — reader, friend — friendship, manage — management. What is also characteristic for this type of affixation is the fact that suffixes can be stacked on one another — this does not happen when it comes to prefixes: re-spect-ful-ness, friend-liness, un-help-ful-ness. It should be noted that affixes are divided into two main categories: while some of them are labelled as inflectional, a majority of them is known to be derivational.

Derivational affixes[edit | edit source]

Derivational affixes can change the word-class of the derivative and can be either prefixes or suffixes — therefore they can produce new lexemes.

However, the meaning they carry is not always fixed — eg. X-ise carries the meaning of either «put into X (computerise — ‘put into a computer’), make more X (modernise —

‘make more modern’ or provide with X (brotherise — ‘provide with a brother’).

Inflectional affixes[edit | edit source]

Another type of affixes is labelled as inflectional. They differ from the other

type in the way that once attached, they will never change the word-class of a derivative. Also, their grammatical function is very much fixed: the plural -s suffix

always creates plural forms of nouns: dog — dogs, cat — cats. In fact, they do not produce new words in English, but rather provide the existing lexemes with new forms:

- the plural [-s] — creates plural forms of nouns: dog — dogs, cat — cats, bush — bushes,

- Saxon genitive [‘s] — indicates possession: Robert — Robert’s (clothes), children — children’s (toys), Jesus — Jesus’ (mercy),

- the past tense [-ed] — creates past forms of regular verbs: walk — walked, delve -delved,

- the third person singular [-s] — enforced by the English grammar in the Present Simple tense: She works there, The knife proves sharp,

- the progressive [-ing] — used in progressive forms of verbs: go — going, see — seeing, ski — skiing,

- the comparative [-er] — forms comparative adjectives: wide — wider, high — higher, far — farther,

- the superlative [est] — forms superlative adjectives: wise — widest, high — highest, far — furthest.

Another type of affixation that can be encountered in either English or Polish

(though to a rather limited scope) is infixation, which involves putting a morpheme in

the middle of a word structure rather than taking lateral positions: al-bloody-mighty,

kanga-bloody-roo. In the English language this only serves as a tool of emotionally

colouring swear-words to give them greater an impact.

Yet another type of suffix are interfixes. They are used in Polish compounds and blends

to ensure phonological feasibility of a word: śrub-o-kręt, park-o-metr, lod-o-łamacz and are

meaningless phonemes that connect two bases. They do exist in English but due to the fact that

English compound-formation does not require such measures their number is scarce (eg. speedo-meter).