There was a heated debate on a sentence discussion for the Duolingo Indonesian from English course: «Should Duolingo give us word-for-word translations or free translations?»

I recently opened the same poll on Reddit, asking which approach would better work for Clozemaster, another language learning app using the so-called «cloze-deletion test» method. Four options are available.

- Always prefer free translations

- Mostly prefer free translations

- Mostly prefer modest word-for-word translations

- Always prefer extreme word-for-word translations

Both of the approaches have pros and cons. But more Duolingo Indonesian course takers at the time supported word-for-word than free translations. Natural free translations make us more comfortable in reading long passages in English while they also make us confused with hundreds of possible answers. In order to manage the complexity and to take into account that the target users of Duolingo are absolute beginners, the majority of course takers prefer word-for-word translations.

To my surprise, the result (still ongoing, though) is more polarized on Reddit than on the Duolingo SD. So far, more users on Reddit support free translations. Please join the poll after reading the following example cases, and/or give your thought on this matter.

Case 1: idiom and word order (JP-EN)

-

JP: 昨日、トムは風邪を{{引き}}ました。

-

EN (free translation): «Tom caught a cold yesterday.«

-

EN (modest W4W): «Yesterday, Tom caught a cold.«

-

EN (extreme W4W): «Yesterday, Tom pulled an evil wind.«

The {{cloze-word}} is a verb, meaning «to pull». But «pulled an evil wind» is not helpful for Japanese learners to answer it. I still wonder, however, which is better: putting «yesterday» at the end or beginning.

Case 2: passive form (ID-EN)

-

ID: «Silakan {{dinikmati}} kuenya.«

-

EN (free translation): «Please help yourself to the cake. «(= Tatoeba version)

-

EN (modest W4W): «Please enjoy the cake if you like.«

-

EN (extreme W4W): «Please be enjoyed with the cake.«

The {{cloze-word}} is written in a passive form in Indonesian. Native speakers intentionally choose a passive form when they are offering something politely. An active verb in an imperative sentence sounds too direct and even insistent even if «please» («silakan») is inserted.

The extreme version is the easiest one to fill in the cloze-word. But no English speaker says «please be enjoyed» with a passive verb.

The modest version uses the active form («enjoy»), but adding «if you like» phrase may give a hint to Indonesian learners.

The free translation sourced from Tatoeba is very hard to guess the cloze-word. {{Dinikmati}} merely means «to be enjoyed».

Often, you might come across something funny when you encounter word-for-word translation. For example, something as simple as the French phrase “Je m’appelle Jean” can become clunky if you translate word-by-word. The word “je” means “I.” The word “me” which is shortened into “m’” here means me. The word “appelle” means “call.” And “Jean,” being a proper noun remains the same. So basically, the phrase “Je m’appelle Jean” literally translates into “I me call Jean” which is not a grammatical English sentence.

Words with More Than One Meaning

So it’s best to avoid word-for-word translation, largely because it doesn’t mix with the different grammatical constructions in different languages. But, also consider the fact that one word can have more than one meaning in a language. For example, the word “hee” in Hindi is usually translated as “only” or “just.” But sometimes, it can be used to underscore or emphasize a certain action or feeling. For example, the sentence “Mujhe yeh karna hee nahin” means “I really don’t want to do this.” In this case, the word “hee” means “really.” However, most people in India translate this incorrectly as “I don’t want to do this only” which is not idiomatic in the English language.

Words with No Exact Counterparts

Apart from grammatical issues and words with more than one meaning, there’s also the fact that certain words just don’t have counterparts in other languages. Take, for example, the French phrase “je ne sais quoi.” A word-by-word translation of this phrase would be “I don’t know what” which hardly means the same thing as the original. So you have to approximate by using phrases like “a certain charm” or “a certain something.” For example, you might say, “That well-dressed lady has a certain charm.” Or you might just keep the French phrase and say, “That well-dressed lady has je ne sais quoi.”

Pointing the Finger at Literal Translation

Be careful not to quickly accuse your translation team of literal translation without understanding first what edits your in-house reviewer has inserted into the translation. All too often a company’s in-house/in-country reviewer has “free-styled” the translation without taking into account the (e.g. English) source content and inserted additional content that was not be found in the original. Professional translators will convey the meaning, without straying from the original source. Which means they won’t embellish, add additional or omit content, or change the meaning of what is being conveyed in the source content. Translators are not granted the creative license to change the meaning of the client’s content.

Either way, you can’t rely on word-for-word translation but have to use some ingenuity to get your meaning across. Contact us for more information.

Word-for-word

translation is another method of rendering sense.

It presents a consecutive verbal translation though at the level of

word-groups and sentences. This way of translation is often employed

both consciously and subconsciously by students in the process

of translating alien grammatical constructions/word forms. Sometimes

students at the initial stage of learning a foreign language may

employ

this way of translation even when dealing with seemingly common

phrases or sentences, which are structurally different from their

equivalents in the native tongue. Usually the students employ

word-for-word

translation to convey the sense of word-groups or sentences which

have a structural form, the order of words, and the means of

connection

quite different from those in the target language. To achieve

faithfulness

various grammtical in translation, word-for-word variants are

to be corrected to avoid various grammatical violations made by the

inexperienced students. Cf. You

are right to begin with*BU маєте

рацію,

щоб

почати

з

instead of Почнемо

з

того/припустимо,

що

ви

маєте

рацію/що

ви

праві.

-

Interlinear translation.

The

interlinear1

way/method of translating is

a conventional

term for a strictly faithful rendering of sense expressed by

word-groups

and sentences at the level of some text. The

method

of interlinear translation may be practically applied to all speech

units(sentences, super syntactic units, passages). Interlinear

translation always provides a completely faithful conveying only of

content, which is often achieved through various transformations of

structure of many sense units.

Interlinear

translating is widely practiced at the intermediary and

advanced stages of studying a foreign language. It is helpful when

checking up the students’ understanding of certain structurally

peculiar

English sense units in the passage under translation.

The interlinear method of translating helps the student to obtain

the necessary training in rendering the main aspects of the foreign

language.

The

method

of interlinear translation is practically employed when rendering

some passages or works for internal office use in scientific/research

centers and laboratories and other organizations and by students in

their translation

practice

-

Literary translation.

Literary

translating represents the highest level of translator’s activity.

Literary translators in addition to dealing with the difficulties

inherent to translations

of all fields, must consider the aesthetic aspects of the text, its

beauty and style, as well as its marks (lexical, grammatical or

phonological) keeping in mind that one language’s stylistic marcs

can be different from another’s. the important idea is that the

quality of the translation

be the same in both languages while also maintaining the integrity of

the contents at the same time.

For

a translator, the fundamental issue is searching for equivalents that

produce the same effects in the translated text as those that the

author was seeking for readers of the original text.

Literary

artistic translation

presents a faithful transmission of content and of the artistic

merits only of a work.

Literary

translations are always performed in literary all-nation languages

and with many transformations which help achieve the ease and beauty

of

the original composition.

When

the SL and TL belong to different cultural groups the first problem

faced by the translator is finding terms in his own language that

express

the highest level of faithfulness possible to the meaning of certain

worlds.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

First off, some data:

According to COCA word-for-word has 60 usages, 3 of them are «word-for-word translation». Word-by-word has 26 usages, none of them are «word-by-word translation» (but some with «transcription»).

The definition of word-for-word:

Oxford: In exactly the same or, when translated, exactly equivalent words

Merriam-Webster: being in or following the exact words, verbatim

The Free Dictionary: one word at a time, without regard for the sense of the whole

Only the last dictionary contains a definition for word-by-word, too:

The Free Dictionary: one word at a time

The definitions given by The Free Dictionary are, obviously, identical to each other.

Google hits:

Word-for-word ~21m

Word-for-word translation ~318k

Word-by-word ~3.8m

Word-by-word translation ~95k

According to usages and dictionaries word-by-word is, at least, less popular. And assuming that there may be a lot of usages from non-natives among the Google hits, this could be an indicator for word-by-word being even utterly wrong.

In another forum I found the following statement:

When I translate something «literally,» (wörtlich) it still follows the main rules of the language I’m translating into. What you mean is «word-by-word» (wortwörtlich) to me.

I assume that this was written by a German but I don’t know it. However, if this would be true a «word-by-word translation» would be a translation where I keep, for instance, the order of the words, disregarding if it makes sense in the target language.

Some examples:

Original: word-by-word

Word-by-word translation: Wort bei Wort (That’s a terrible translation!)Original: It is critical to know…

Word-by-word translation: Es ist kritisch zu wissen… (That’s a terrible translation!)Original: Ich glaub, ich spinne.

Word-by-word translation: I think I spider. (I guess only Germans understand this.)

A «word-for-word translation», however, would be an attempt to keep the word-choice as close as possible but following the rules of the target language (e.g. order of words) and also considering if the statement still makes sense in the other language. Here are better translations for the examples above:

Wort für Wort

Es ist wichtig zu wissen…

I think, I’m going nuts. (Actually, this is not a word-for-word translation but rather a sense-for-sense translation.)

So, my questions again:

- As neither Oxford nor Merriam-Webster have any entries for word-by-word in their dictionaries: is word-by-word actually valid?

- If yes, is there any difference between «word-by-word translation» and «word-for-word translation»? If yes again, what is it specifically?

Advantages and disadvantages of Word for Word Translation

Word for word translation or literal translation is the rendering of text from one language to another one word at a time with or without conveying the sense of the original text. In translation studies, literal translation is often associated with scientific, technical, technological or legal texts.

A bad practice

It is often considered a bad practice of conveying word by word translation in non-technical texts. This usually refers to the mistranslation of idioms that affects the meaning of the text, making it unintelligible. The concept of literal translation may be viewed as an oxymoron (contradiction in terms), given that literal denotes something existing without interpretation, whereas a translation, by its very nature, is an interpretation (an interpretation of the meaning of words from one language into another).

Usage

A word for word translation can be used in some languages and not others dependent on the sentence structure: El equipo está trabajando para terminar el informe would translate into English as The team is working to finish the report. Sometimes it works and sometimes it does not. For example, the Spanish sentence above could not be translated into French or German using this technique because the French and German sentence structures are completely different. And because one sentence can be translated literally across languages does not mean that all sentences can be translated literally.

Literal translation can also denote a translation that represents the precise meaning of the original text but does not attempt to convey its style, beauty, or poetry. There is, however, a great deal of difference between a literal translation of a poetic work and a prose translation. A literal translation of poetry may be in prose rather than verse, but also be error free. Charles Singleton’s translation of The Divine Comedy (1975) is regarded as a prose translation.

Machine Translation

Early machine translations were famous for this type of translation because they simply created a database of words and their translations. Later attempts utilized common phrases which resulted in better grammatical structure and capture of idioms but with many words left in the original language.

The systems that we use nowadays are based on a combination of technologies and apply algorithms to correct the “natural” sound of the translation. However, professional translation agencies that use machine translation create a rough translation first that is then tweaked by a professional translator.

Mistakes and Jokes

Literal translation of idioms results quite often in jokes and amusement among translators and not only. The following famous example has often been told both in the context of newbie translators and that of machine translation: When the sentence “The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak was translated into Russian and then back to English, the result was “The vodka is good, but the meat is rotten. This is generally believed to be simply an amusing story, and not a factual reference to an actual machine translation error.

Sign up and receive weekly tips to get started in translation

Sign up and receive free weekly tips

No spam, we promise.

Since an early age I have been passionate about languages. I hold a Master’s degree in Translation and Interpreting, and I have worked as a freelance translator for several years. I specialize in Marketing, Digital Marketing, Web and Social Media. I love blogging and I also run the blog www.italiasocialmedia.com

A recent Facebook group post asked about whether or not teachers should do word-for-word translation.

Word-for-word is not necessarily the same as direct translation, though it can be. For example, in German we say mein Nahme ist Chris (“my name is Chris”). In this case, the two languages use the same word order.

Here are some more examples of what word-for-word translation looks like:

In Spanish, a grammatically good sentence is estudiar no me gusta, which literally means “to study not me pleases” but an English speaker would translate this as “I don’t like studying” or “I don’t like to study.”

In other languages, things get weirder: some languages don’t (always) use pronouns. When I acquired a bit of Mandarin years ago working for Taiwan-born Visco in the camera store, some of the sentences in Mandarin were something like “go store yesterday” which translates into English as “Yesterday I went to the store.” In other languages, like French, you can’t just say “no” or “not:” you have to wrap the verb with ne…pas. In some languages in some places you do not always need a verb. E.g in German, if somebody asks you Bist du gestern nach Berlin gegangen? (meaning “Did you go to Berlin?”), you can answer with Nein, gestern bin ich nicht nach Berlin (literally “No, yesterday am I not to Berlin”).

I think we should generally not use word-for-word translation. Why?

- WFW unnecessarily confuses the kids. The point of direct translation is to clarify meaning. You want to waste as little time as possible and having them think through weird word order is not doing much for meaning. Terry Waltz calls this “a quick meaning dump,” by which she means the point is to get from L2 to L1 in as simple and easy a way as possible.

2. WFW turns on the Monitor. In other words, when we do this, students start to focus on language as opposed to meaning. We know that the implicit (subconscious) system is where language is acquired and stored, so there is little point in getting them to focus on language. Both Krashen and VanPatten have argued (and shown) that conscious knowledge about language does not translate into acquisition of language. Monitor use is at best not very helpful so why bother?

3. WFW can cause problems for people whose L1 is not English. In my classes, we have lots of kids whose first languages are Hindi, Punjabi, Urdu, Tagalog etc etc. Some of them are fairly new to English (they speak with accents and their English output has errors). For example, a classic South Asian L2 English error I hear/read in my English classes all the time is “yesterday he had gone to the store” instead of “yesterday he went to the store.”

What these L2s need, more than anything, is not just grammatically good L3 but also gramamtically coherent English. We tend to forget that, say, the Ilocarno-speaking Filipino kid who is in our Spanish class is also learning English in our Spanish classes.

Powerhouse Spanish teacher Alina Filipescu writes

I tell students what “ME LLAMO” means word for word, “myself I call,” then I add that in other words it means “my name is.” Since I’ve switched to this instead of just telling students that ME LLAMO means “my name is” like a textbook says it, I’ve seen a lot less errors. I now rarely see students make the mistake “ME LLAMO ES John.” When students do volleyball translations, then I have them do translations that make sense and not word for word. I do it word for word as a class so that I can control where it goes. I also like that students can “feel” what the syntax of the sentence is in the language that I teach. Just like Blaine always says, if there is something better than I will try it and adopt it. This is not written in stone for me, it’s what I do right now because it made sense when I heard/saw somebody else do it.

Filipescu makes three good points here. First, students should know that you generally cannot translate most things WFW and have it make sense. We all know what happens when legacy-methods assignments demand output beyond kids’ abilities: Google transliterate!

She also says that she gets less *me llamo es (“myself I call is”) as a result. I don’t doubt it…but she raises the interesting question of why and under what conditions? Was this compared to when she used legacy methods? Or compared to when she started C.I. and just did general meaning translation? I too get a lot less me llamo es and other such errors, but I think it has more to do with C.I. allowing me to spend way more time meaningfully in the target language than anything else.

Third, Filipescu translates me as “myself” which is correct…here. However, elsewhere me means “me,” rather than “myself,” more or less like in English, eg me pegó means “she hit me.” Now if we obsess over WFW (not that Alina does so) we are going to focus the kids on two different meanings “anchored” to one word. Which I could see being confusing.

Filipescu’s post also raises the interesting question of under what conditions the kids write. I have found that the more time they have, the more they screw up, because when they have notes, dictionaries, etc, they start thinking, and thinking is what (linguistically speaking) gets you into grammatical trouble. One of the reasons C.I. uses little vocab and LOADS of repetition (via parallel characters, repeating scenes, embedded readings, etc) is to automatise (via processing, and not via “practise” talking) language use. The less time they have to write, the less they think, and the more you get to see what the students’ implicit (subconscious) systems have picked up.

Anyway, overall, I would say, point out the weirdness of word order (or whatever aspect of grammar is different) once, then stick to natural, meaningful L1 useage for translation. Mainly, this is to keep us in the TL as much as possible, and eliminate L1 distractions.

11th November 2017

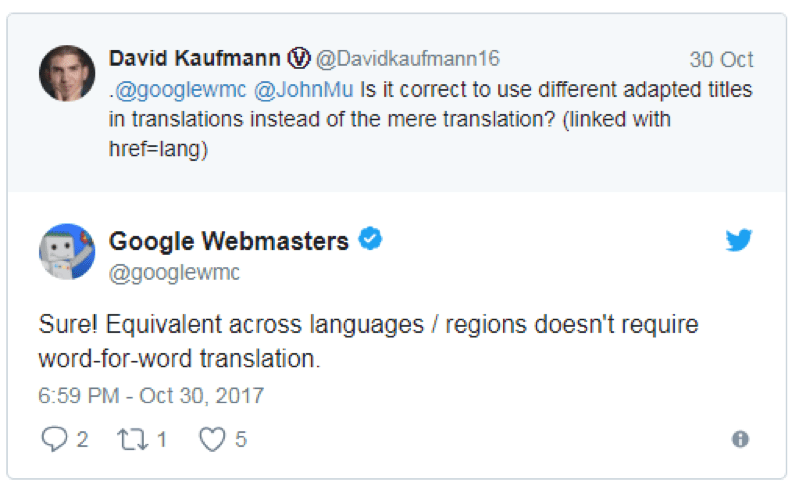

In its recent tweet, Google Webmasters stated that multilingual pages shouldn’t be word for word translation. Some website owners believe that Google requires word for word translation when you use hreflang and make a multilingual website. That is absolutely not the case. In fact, it is best to translate the page naturally and not do word for word translation. Appoint a professional translator fluent in both languages to translate it in a natural way, easy for visitors to understand and engage with. That means some words might not be on the page at all but bad website translation can have a catastrophic impact on your business and its sales.

What is Google Translate and how it works?

Today, businesses need digital content to be translated quickly, almost on the fly, and a single or even team of translators may not be able to provide acceptable turnaround times.

In an effort to accelerate the process, many businesses are turning to Google Translate for website translation. Google Translate is Google’s free tool that instantly translates words, phrases, and web pages between English and over 100 other languages. Google Translate uses a process called “statistical machine translation”. This means that Google computers generate translations based on patterns found in a large amount of text. Instead of teaching their computers all the rules of a language, they let their computers discover the rules themselves. They do this by analysing documents that have already been translated by human translators and scanning these texts, looking for statistically significant patterns.

You can find out more about Google Translate in the video below.

Because the Google Translate widget uses an algorithm that is based on probability, the system is most effective when used with smaller chunks of language to convey simple messages. This makes is fine for casual conversation, and internal communications but not for technical documents or important emails due to inaccuracies around grammar and sometimes meaning. Error in medical translation can cost lives.

Can businesses rely on Google Translate for an accurate translation?

Using a translation method that relies on probability increases the chances of errors. The translated text will only be as good as the machine allows it to be, but never as good as human translation will make it.

An article for The Telegraph says that “humans have shorter attention span than goldfish, thanks to smartphones” – if your website content is hard to understand and not localised, your visitors will bounce off and go somewhere else. Can you risk that? Or is the initial investment worth the outcome?