Filters

Filter synonyms by Letter

B F G L M O P S U V

Filter by Part of speech

phrase

noun

Suggest

If you know synonyms for Single woman, then you can share it or put your rating in listed similar words.

Suggest synonym

Menu

Single woman Thesaurus

External Links

Other usefull source with synonyms of this word:

Synonym.tech

Thesaurus.com

Photo search results for Single woman

Image search results for Single woman

Cite this Source

- APA

- MLA

- CMS

Synonyms for Single woman. (2016). Retrieved 2023, April 14, from https://thesaurus.plus/synonyms/single_woman

Synonyms for Single woman. N.p., 2016. Web. 14 Apr. 2023. <https://thesaurus.plus/synonyms/single_woman>.

Synonyms for Single woman. 2016. Accessed April 14, 2023. https://thesaurus.plus/synonyms/single_woman.

- Amy Froide is a professor of history at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

- Froide writes that while actress Emma Watson describes herself as «self-partnered,» there’s a long history of terms for unmarried women.

- In the 17th century, new terms — like «spinster» and «singlewoman» — appeared as the number of unwed women rose. As marriage rates dropped, negative terms like «old maids» started to come into use and English authorities created a Marriage Duty Tax.

- Today’s marriage pattern is essentially a return to that of the 17th century, but women like Watson still feel the need to justify their marital status.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Loading

Something is loading.

Thanks for signing up!

Access your favorite topics in a personalized feed while you’re on the go.

In a recent interview with Vogue, actress Emma Watson opened up about being a single 30-year-old woman. Instead of calling herself single, however, she used the word «self-partnered.»

I’ve studied and written about the history of single women, and this is the first time I am aware of «self-partnered» being used. We’ll see if it catches on, but if it does, it will join the ever-growing list of words used to describe single women of a certain age.

Women who were once called spinsters eventually started being called old maids. In 17th-century New England, there were also words like «thornback» — a sea skate covered with thorny spines — used to describe single women older than 25.

Attitudes toward single women have repeatedly shifted — and part of that attitude shift is reflected in the names given to unwed women.

The rise of the ‘singlewoman’

Before the 17th century, women who weren’t married were called maids, virgins, or «puella,» the Latin word for «girl.» These words emphasized youth and chastity, and they presumed that women would only be single for a small portion of their life — a period of «pre-marriage.»

But by the 17th century, new terms, such as «spinster» and «singlewoman,» emerged.

What changed? The numbers of unwed women — or women who simply never married — started to grow.

In the 1960s, demographer John Hajnal identified the «Northwestern European Marriage Pattern,» in which people in northwestern European countries such as England started marrying late — in their 30s and even 40s. A significant proportion of the populace didn’t marry at all. In this region of Europe, it was the norm for married couples to start a new household when they married, which required accumulating a certain amount of wealth. Like today, young men and women worked and saved money before moving into a new home, a process that often delayed marriage. If marriage were delayed too long — or if people couldn’t accumulate enough wealth — they might not marry at all.

Now terms were needed for adult single women who might never marry. The term spinster transitioned from describing an occupation that employed many women — a spinner of wool — to a legal term for an independent, unmarried woman.

Single women made up, on average, 30% of the adult female population in early modern England. My own research on the town of Southampton found that in 1698, 34.2% of women over 18 were single, another 18.5% were widowed, and less than half, or 47.3%, were married.

Many of us assume that past societies were more traditional than our own, with marriage more common. But my work shows that in 17th-century England, at any given time, more women were unmarried than married. It was a normal part of the era’s life and culture.

The pejorative ‘old maid’

In the late 1690s, the term old maid became common. The expression emphasizes the paradox of being old and yet still virginal and unmarried. It wasn’t the only term that was tried out; the era’s literature also poked fun at «superannuated virgins.» But because «old maid» trips off the tongue a little easier, it’s the one that stuck.

The undertones of this new word were decidedly critical.

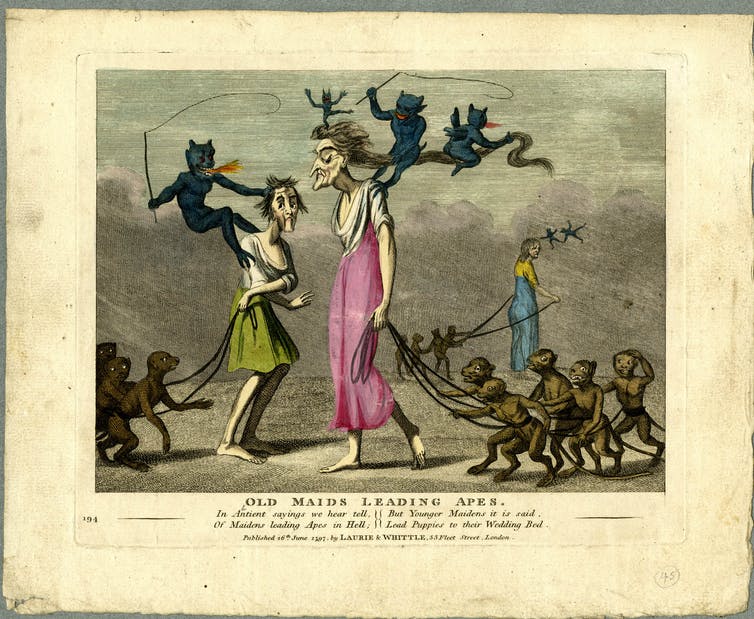

«A Satyr upon Old Maids,» an anonymously written 1713 pamphlet, referred to never-married women as «odious,» «impure,» and repugnant. Another common trope was that old maids would be punished for not marrying by «leading apes in hell.»

At what point did a young, single woman become an old maid? There was a definitive line: In the 17th century, it was a woman in her mid-20s.

For instance, the single poet Jane Barker wrote in her 1688 poem, «A Virgin Life,» that she hoped she could remain «Fearless of twenty-five and all its train, / Of slights or scorns, or being called Old Maid.»

These negative terms came about as the numbers of single women continued to climb and marriage rates dropped. In the 1690s and early 1700s, English authorities became so worried about population decline that the government levied a Marriage Duty Tax, requiring bachelors, widowers, and some single women of means to pay what amounted to a fine for not being married.

Still uneasy about being single

Today in the US, the median first age at marriage for women is 28. For men, it’s 30.

What we’re experiencing now isn’t a historical first; instead, we’ve essentially returned to a marriage pattern that was common 300 years ago. From the 18th century up until the mid-20th century, the average age at first marriage dropped to a low of age 20 for women and age 22 for men. Then it began to rise again.

There’s a reason Vogue was asking Watson about her single status as she approached 30. To many, age 30 is a milestone for women — the moment when, if they haven’t already, they’re supposed to go from being footloose and fancy-free to thinking about marriage, a family, and a mortgage.

Even if you’re a wealthy and famous woman, you can’t escape this cultural expectation. Male celebrities don’t seem to be questioned about being single and 30.

While no one would call Watson a spinster or old maid today, she nonetheless feels compelled to create a new term for her status: «self-partnered.» In what some have dubbed the «age of self-care,» perhaps this term is no surprise. It seems to say, «I’m focused on myself and my own goals and needs. I don’t need to focus on another person, whether it’s a partner or a child.»

To me, though, it’s ironic that the term «self-partnered» seems to elevate coupledom. Spinster, singlewoman, or singleton: None of those terms openly refers to an absent partner. But self-partnered evokes a missing better half.

It says something about our culture and gender expectations that despite her status and power, a woman like Watson still feels uncomfortable simply calling herself single.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

By Amy Froide, chair and professor, Department of History, UMBC

In a recent interview with Vogue, actress Emma Watson opened up about being a single 30-year-old woman. Instead of calling herself single, however, she used the word “self-partnered.”

I’ve studied and written about the history of single women, and this is the first time I am aware of “self-partnered” being used. We’ll see if it catches on, but if it does, it will join the ever-growing list of words used to describe single women of a certain age.

Women who were once called spinsters eventually started being called old maids. In 17th-century New England, there were also words like “thornback” – a sea skate covered with thorny spines – used to describe single women older than 25.

Attitudes toward single women have repeatedly shifted – and part of that attitude shift is reflected in the names given to unwed women.

The rise of the ‘singlewoman’

Before the 17th century, women who weren’t married were called maids, virgins or “puella,” the Latin word for “girl.” These words emphasized youth and chastity, and they presumed that women would only be single for a small portion of their life – a period of “pre-marriage.”

But by the 17th century, new terms, such as “spinster” and “singlewoman,” emerged.

What changed? The numbers of unwed women – or women who simply never married – started to grow.

In the 1960s, demographer John Hajnal identified the “Northwestern European Marriage Pattern,” in which people in northwestern European countries such as England started marrying late – in their 30s and even 40s. A significant proportion of the populace didn’t marry at all. In this region of Europe, it was the norm for married couples to start a new household when they married, which required accumulating a certain amount of wealth. Like today, young men and women worked and saved money before moving into a new home, a process that often delayed marriage. If marriage were delayed too long – or if people couldn’t accumulate enough wealth – they might not marry at all.

Now terms were needed for adult single women who might never marry. The term spinster transitioned from describing an occupation that employed many women – a spinner of wool – to a legal term for an independent, unmarried woman.

Single women made up, on average, 30% of the adult female population in early modern England. My own research on the town of Southampton found that in 1698, 34.2% of women over 18 were single, another 18.5% were widowed, and less than half, or 47.3%, were married.

Many of us assume that past societies were more traditional than our own, with marriage more common. But my work shows that in 17th-century England, at any given time, more women were unmarried than married. It was a normal part of the era’s life and culture.

The pejorative ‘old maid’

In the late 1690s, the term old maid became common. The expression emphasizes the paradox of being old and yet still virginal and unmarried. It wasn’t the only term that was tried out; the era’s literature also poked fun at “superannuated virgins.” But because “old maid” trips off the tongue a little easier, it’s the one that stuck.

The undertones of this new word were decidedly critical.

“A Satyr upon Old Maids,” an anonymously written 1713 pamphlet, referred to never-married women as “odious,” “impure” and repugnant. Another common trope was that old maids would be punished for not marrying by “leading apes in hell.”

At what point did a young, single woman become an old maid? There was a definitive line: In the 17th century, it was a woman in her mid-20s.

For instance, the single poet Jane Barker wrote in her 1688 poem, “A Virgin Life,” that she hoped she could remain “Fearless of twenty-five and all its train, / Of slights or scorns, or being called Old Maid.”

These negative terms came about as the numbers of single women continued to climb and marriage rates dropped. In the 1690s and early 1700s, English authorities became so worried about population decline that the government levied a Marriage Duty Tax, requiring bachelors, widowers and some single women of means to pay what amounted to a fine for not being married.

Still uneasy about being single

Today in the U.S., the median first age at marriage for women is 28. For men, it’s 30.

What we’re experiencing now isn’t a historical first; instead, we’ve essentially returned to a marriage pattern that was common 300 years ago. From the 18th century up until the mid-20th century, the average age at first marriage dropped to a low of age 20 for women and age 22 for men. Then it began to rise again.

There’s a reason Vogue was asking Watson about her single status as she approached 30. To many, age 30 is a milestone for women – the moment when, if they haven’t already, they’re supposed to go from being footloose and fancy-free to thinking about marriage, a family and a mortgage.

Even if you’re a wealthy and famous woman, you can’t escape this cultural expectation. Male celebrities don’t seem to be questioned about being single and 30.

While no one would call Watson a spinster or old maid today, she nonetheless feels compelled to create a new term for her status: “self-partnered.” In what some have dubbed the “age of self-care,” perhaps this term is no surprise. It seems to say, I’m focused on myself and my own goals and needs. I don’t need to focus on another person, whether it’s a partner or a child.

To me, though, it’s ironic that the term “self-partnered” seems to elevate coupledom. Spinster, singlewoman or singleton: None of those terms openly refers to an absent partner. But self-partnered evokes a missing better half.

It says something about our culture and gender expectations that despite her status and power, a woman like Watson still feels uncomfortable simply calling herself single.

*****

Amy Froide, Professor of History, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Header image: Photo by Lucian Andrei on Unsplash.

Tags: CAHSS, History, Single Women, The Conversation

In a recent interview with Vogue, actress Emma Watson opened up about being a single 30-year-old woman. Instead of calling herself single, however, she used the word «self-partnered.»

I’ve studied and written about the history of single women, and this is the first time I am aware of «self-partnered» being used. We’ll see if it catches on, but if it does, it will join the ever-growing list of words used to describe single women of a certain age.

Women who were once called spinsters eventually started being called old maids. In 17th-century New England, there were also words like «thornback»—a sea skate covered with thorny spines—used to describe single women older than 25.

Attitudes toward single women have repeatedly shifted—and part of that attitude shift is reflected in the names given to unwed women.

The rise of the ‘singlewoman’

Before the 17th century, women who weren’t married were called maids, virgins or «puella,» the Latin word for «girl.» These words emphasized youth and chastity, and they presumed that women would only be single for a small portion of their life—a period of «pre-marriage.»

But by the 17th century, new terms, such as «spinster» and «singlewoman,» emerged.

What changed? The numbers of unwed women—or women who simply never married—started to grow.

In the 1960s, demographer John Hajnal identified the «Northwestern European Marriage Pattern,» in which people in northwestern European countries such as England started marrying late—in their 30s and even 40s. A significant proportion of the populace didn’t marry at all. In this region of Europe, it was the norm for married couples to start a new household when they married, which required accumulating a certain amount of wealth. Like today, young men and women worked and saved money before moving into a new home, a process that often delayed marriage. If marriage were delayed too long—or if people couldn’t accumulate enough wealth—they might not marry at all.

Now terms were needed for adult single women who might never marry. The term spinster transitioned from describing an occupation that employed many women – a spinner of wool—to a legal term for an independent, unmarried woman.

Single women made up, on average, 30% of the adult female population in early modern England. My own research on the town of Southampton found that in 1698, 34.2% of women over 18 were single, another 18.5% were widowed, and less than half, or 47.3%, were married.

Many of us assume that past societies were more traditional than our own, with marriage more common. But my work shows that in 17th-century England, at any given time, more women were unmarried than married. It was a normal part of the era’s life and culture.

The pejorative ‘old maid’

In the late 1690s, the term old maid became common. The expression emphasizes the paradox of being old and yet still virginal and unmarried. It wasn’t the only term that was tried out; the era’s literature also poked fun at «superannuated virgins.» But because «old maid» trips off the tongue a little easier, it’s the one that stuck.

The undertones of this new word were decidedly critical.

«A Satyr upon Old Maids,» an anonymously written 1713 pamphlet, referred to never-married women as «odious,» «impure» and repugnant. Another common trope was that old maids would be punished for not marrying by «leading apes in hell.»

At what point did a young, single woman become an old maid? There was a definitive line: In the 17th century, it was a woman in her mid-20s.

For instance, the single poet Jane Barker wrote in her 1688 poem, «A Virgin Life,» that she hoped she could remain «Fearless of twenty-five and all its train, / Of slights or scorns, or being called Old Maid.»

These negative terms came about as the numbers of single women continued to climb and marriage rates dropped. In the 1690s and early 1700s, English authorities became so worried about population decline that the government levied a Marriage Duty Tax, requiring bachelors, widowers and some single women of means to pay what amounted to a fine for not being married.

Still uneasy about being single

Today in the U.S., the median first age at marriage for women is 28. For men, it’s 30.

What we’re experiencing now isn’t a historical first; instead, we’ve essentially returned to a marriage pattern that was common 300 years ago. From the 18th century up until the mid-20th century, the average age at first marriage dropped to a low of age 20 for women and age 22 for men. Then it began to rise again.

There’s a reason Vogue was asking Watson about her single status as she approached 30. To many, age 30 is a milestone for women – the moment when, if they haven’t already, they’re supposed to go from being footloose and fancy-free to thinking about marriage, a family and a mortgage.

Even if you’re a wealthy and famous woman, you can’t escape this cultural expectation. Male celebrities don’t seem to be questioned about being single and 30.

While no one would call Watson a spinster or old maid today, she nonetheless feels compelled to create a new term for her status: «self-partnered.» In what some have dubbed the «age of self-care,» perhaps this term is no surprise. It seems to say, I’m focused on myself and my own goals and needs. I don’t need to focus on another person, whether it’s a partner or a child.

To me, though, it’s ironic that the term «self-partnered» seems to elevate coupledom. Spinster, singlewoman or singleton: None of those terms openly refers to an absent partner. But self-partnered evokes a missing better half.

It says something about our culture and gender expectations that despite her status and power, a woman like Watson still feels uncomfortable simply calling herself single.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Citation:

Spinster, old maid or self-partnered – why words for single women have changed through time (2019, December 2)

retrieved 14 April 2023

from https://phys.org/news/2019-12-spinster-maid-self-partnered-words-women.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

- bachelor girl

- fuddy-duddy

- goody-goody

- lone woman

- maiden

- prig

- prude

- spinster

- unmarried woman

- virgin

- bachelor girl

- lone woman

- old maid

Roget’s 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by the Philip Lief Group.

On this page you’ll find 19 synonyms, antonyms, and words related to single woman, such as: old maid, single girl, and unattached female.

SYNONYM OF THE DAY

OCTOBER 26, 1985

WORDS RELATED TO SINGLE WOMAN

- old maid

- single girl

- single woman

- unattached female

- bachelor girl

- fuddy-duddy

- goody-goody

- lone woman

- maiden

- prig

- prude

- single woman

- spinster

- unmarried woman

- bachelor girl

- lone woman

- old maid

- single woman

- virgin

Roget’s 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by the Philip Lief Group.

Synonyms for Single woman

-

spinster

older unmarried woman

-

old maid

unmarried woman

-

bachelor girl

unmarried woman

older unmarried woman

-

maiden

older unmarried woman

-

lone woman

unmarried woman

older unmarried woman

-

prude

older unmarried woman

-

virgin

unmarried woman

-

unattached female

unmarried woman

-

single girl

unmarried woman

-

unmarried woman

older unmarried woman

-

prig

-

goody-goody

-

fuddy-duddy

-

feme sole

-

bachelorette

-

single

-

maidens

-

maid

-

spinstress

For more similar words, try Single woman on Thesaurus.plus dictionary