-

#1

Hi teachers,

I have no religious faith. So, the words that has come up to my mind are «atheist», «non-believer»,»agnostic», «secular humanist», and «freethinker».

I have already looked them up in dictionaries but the definitions I found in dictionaries are similar and do not give me any clear idea about how I should call myself.

To describe myself, I have no religious faith but this lack of religous faith is not associated with any political stance. (I know that most secular humanists are liberal.) But I am a centrist.

Freethinking is also a little related to political beliefs as far as I can notice. They don’t accept orthodox beliefs and want to from their own beliefs.

Atheist is a term that sounds fine to me because it doest not indicate the political stance of the person. But it means not believing in the creator gods so every Buddhist can be called atheists as well. But I am not a Buddhist.

«Agnostic» as far as I know means someone who doubts the religious teaching. I think I am a bit more than an agnostic person because I don’t have any faith at all.

So I think the best way to call myself is «non-believer», but I am not so sure.

Which word do you think is the most appropriate one to address a person who does not have any religious faith but does not want to associate himself/herself with any political stance by the use of this word?

I would really appreciate your views because dictionaries cannot help me with this any longer. You opinion would be very useful to me.

Thank you very much in advance. (I have checked the previous threads as well but they do not give an answer to this particular question.)

-

#3

I think non-believer works. I’m not sure why you think politics is involved in these labels. Aside from ‘secular humanist’ which is often ‘liberal’ I don’t see any politics as readily linked to ‘atheist’ ‘freethinker’ etc.

-

#4

If you «have no religious faith,» nonreligious would be a good way to describe yourself.

However, you should realize that a nonreligious person could still be a spiritual person and believe in God or gods.

I think you have to tell us if you believe in the existence of God or gods for us to comment on the appropriateness of

terms like «atheist» and «agnostic» to describe yourself.

-

#5

I think non-believer works. I’m not sure why you think politics is involved in these labels. Aside from ‘secular humanist’ which is often ‘liberal’ I don’t see any politics as readily linked to ‘atheist’ ‘freethinker’ etc.

I think what OP means by political stance is they don’t wanted to be lumped into a particular group. Non-believer sounds a bit too extreme. Non-religious or just «not religious» is just vague enough to describe someone that is not part of organized religion or any other group.

-

#6

But I myself would be a little puzzled if someone said, «I’m not a religious person but I believe in God.»

I suppose I might think they were a deist (T. Jefferson) or pantheist (Spinoza).

Usually, such a person says, «I’m not involved in organized religion, but I believe in God.»

If you «have no religious faith,» nonreligious would be a good way to describe yourself.

However, you should realize that a nonreligious person could still be a spiritual person and believe in God or gods.I think you have to tell us if you believe in the existence of God or gods for us to comment on the appropriateness of

terms like «atheist» and «agnostic» to describe yourself.

-

#7

I’ve heard many people claim that they weren’t religious but spiritual instead, meaning that

they do not believe in one particular religion but do acknowledge the presence of a higher power.

-

#8

Thank you very much everyone for your kind response and advice.

Well, if I have to describe myself again to avoid confusion, I reject everything spiritual and supernormal. I follow the ideas of people like Steven Hawking and believe in science only, nothing else. But I don’t want use a term that indicate some political beliefs like humanism because they are liberal at the same time but I am centrist/independent when it comes to politics. I guess this explains what I am.

«Non-religious» is fine, but it is an adjective. Is there any noun that can describe the kind of person like me?

-

#9

«Freethinker» sounds good, in my opinion. Or perhaps «independent thinker».

-

#10

«Freethinker» is a bit dated—I think of Thomas Paine. Perhaps a more modern term, «free spirit.»

-

#11

Thank you for the clarification in post #8, MN.

Personally, I think you could call yourself an atheist.

There is a good explanation of the difference between an atheist and an agnostic

here

:

An atheist lacks faith in God, believes there is no god, or lacks awareness of gods. An agnostic either believes that it is impossible to know whether there is a god or is noncommittal on the issue. The difference may seem small, but atheism and agnosticism are actually vastly different worldviews

-

#12

Thanks again everyone. I usually describe myself as an atheist as well, but Buddhists are also a kind of atheist since they reject the idea of creator God and embrace the Karma theory. Some Buddhists I know sometimes say, «you can call me an atheist; I don’t believe in any creator immortal god, but I believe in only Karma».

Do you call a Karma believer who believes in no god an atheist as well, as a native speaker ?

Thanks again everyone. I really appreciate everyone’s views.

-

#13

Thanks again everyone. I usually describe myself as an atheist as well, but Buddhists are also a kind of atheist since they reject the idea of creator God and embraces the Karma theory. Some Buddhists I know sometimes say, «you can call me an atheist; I don’t believe in any creator immortal god, but I believe in only Karma».

Do you call a Karma believer who believes in no god an atheist as well, as a native speaker ?

Thanks again everyone. I really appreciate everyone’s views.

A believer in Buddhism may be an atheist by definition but that’s not the common use of atheist. A believer in karma could be described as spiritual or if it falls into the beliefs of Buddhism, a Buddhist.

-

#14

You are an atheist.

The fact that other people, with different views to you, can also be called atheists does not stop it being the best word for your personal position.

I have never considered the need to label Buddhists as anything other than Buddhists, so I wouldn’t really think of calling them atheists, though from what you say the label works for them.

-

#15

OK, again, thank you very much everyone. All your views are very useful to a non-native speaker like me. Thank you very much, teachers.

-

#16

I agree with Suzi and LH: atheist conveys the meaning you want, Mitchell, and I think most people would understand it that way.

I don’t know where you found that meaning, «not believing in the creator gods». For me it’s just ‘not believing in any god or gods’ – from the Greek a- (without) and theos (god).

I wouldn’t use freethinker or non-believer, because those terms can be used in contexts other than religion. In my experience, people with particular religious beliefs may use the term «non-believers» when speaking to or about others who don’t share those beliefs. But I don’t think I’ve ever heard people calling themselves non-believers. I’m sure many atheists would insist that they believe in many things, but that gods just don’t figure among those things.

Ws

-

#17

I too would suggest, atheist. It’s current use tends to include those who reject all forms of «spirituality» and dogma for which there is no hard evidence: this would include «karma».

Last edited: Sep 3, 2015

-

#18

To describe myself, I have no religious faith but this lack of religous faith is not associated with any political stance. (I know that most secular humanists are liberal.) But I am a centrist.

You should know that often political ideologies are simplified to the point of almost being meaningless, and I don’t think — at all — that «secular humanists» have to be «liberals».

Atheist is a term that sounds fine to me because it doest not indicate the political stance of the person. But it means not believing in the creator gods so every Buddhist can be called atheists as well. But I am not a Buddhist.

«Agnostic» as far as I know means someone who doubts the religious teaching. I think I am a bit more than an agnostic person because I don’t have any faith at all.

Agnosticism refers to knowledge, i.e. the stance that one can’t or don’t know whether there is a god(s). «Atheist» seems to be appropriate for you. I would go with that.

-

#19

I wonder whether Mitchell is concerned about the brand of aggressive atheism that is getting more prevalent in the UK and US, but would be very unusual in East Asia. In a context where most people are assumed to have some religious faith, the term unbeliever might work.

-

#21

I too would suggest, atheist. It’s current use tends to include those who reject all forms of «spirituality» and dogma for which there is no hard evidence.

Sorry, PaulQ, but I think an atheist can

also

be a person who doesn’t believe in God but believes in some other forms of spirituality like nature, meditation/yoga. (Regarding nature, the picture of Thomas Hardy comes to my mind). Just like Mitchell, I am also an out-and-out atheist (a sore in the eyes of all the people around me) and believe in science only.

Edit: To correct my mistake of having attributed PaulQ’s comment to Parla.

Last edited: Sep 3, 2015

-

#22

I did say, «It’s current use tends to include …»

The boundaries of what is considered to be atheism are as vague as those that define «religion.» At the time that the word entered English, there was only one religion to consider, and that was Christianity. The rest were simply pagans (if they had gods) and «mystics» if they did not (and sometimes both.). You say you are an «out and out atheist» and «believe in science only.» There is no science in «karma» or «spirituality» both of which are unfalsifiable and unmeasurable. These qualities and the sole acceptance of real experience to interpret the world are what distinguish those who have faith from those who do not. Those who do not have faith (of any sort) tend to be known as atheists.

-

#23

Thank you, PaulQ, that’s clear. When I said a person can be an atheist and yet believe in some other forms of spirituality like nature, etc, I was not referring to myself, but some other people.

Last edited: Sep 3, 2015

-

#24

In a context where most people are assumed to have some religious faith, the term unbeliever might work.

I suppose it might, Nat, but to me it rather smacks of infidels and crusades, or hellfire and brimstone raining down upon the unbelievers, and the like.

Ws

-

#25

Just for completeness,

in some areas of society the word will carry baggage. For some religious people, the word atheist defines more than just the neutral description above, and they think all atheists are more or less militant. A typical quote from a facebook page to illustrate the thinking: «This is because militant atheists think religion is a disease far worse than cancer». For these people the term «atheist» has connotations of anarchic, amoral and anti-religion. However, they are loading up the term with their views and do not understand the meaning of the word as described above. Most atheists I know leave religious people to their own beliefs, although there are «militant atheists» (like militant/fundamental proselytizing religious fanatics) that seem to have given us a bad reputation, but there is little we can do to educate them as to the original meaning of the word.

Last edited: Sep 3, 2015

-

#26

I think we’re doing everyone a HUGE disservice by describing «atheists» as «militant atheists» «like militant/fundamental proselytizing religious fanatics».

The atheists described as «militant» seem to be just vocal about their atheism and anti-religious stance. But just as some religious people want to make it seem as if atheists by definition are guilty of the same level of irrational belief as they themselves are — thereby redefining the usage of the word belief in other contexts — they are also seemingly trying to use the word «militant» to taint the atheist stance in general.

I have a hard time explaining my thoughts better than above because I’m tired, but the gist of it is that by calling (some) atheists militant the effect is soiling the atheists by comparing them to militant religious fanatics, while at the same time lessening the meaning of «militant when actually saying «militant religious fanatics». After all, with this use of language some atheists are militant just like some religious people are… hence the use of the word… so what’s the difference? Of course the difference is huge, which is why the word shouldn’t be used.

-

#27

I suppose it might, Nat, but to me it rather smacks of infidels and crusades, or hellfire and brimstone raining down upon the unbelievers, and the like.

Ws

Yes, you have a point there, although perhaps unbeliever is still different from infidel or pagan or heathen. I was thinking of a self-description rather than an other-description.

-

#28

I think we’re doing everyone a HUGE disservice by describing «atheists» as «militant atheists» «like militant/fundamental proselytizing religious fanatics».

No-one here was describing them that way. We have described the literal meaning and tried to clarify with respect to «god» vs spirituality and belief and so on.

I only mentioned, as a caution, that some «religious» people think that way so the OP would know of that group and their meaning of the word «atheist», and how negatively it can occasionally be.

-

#29

Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, among other books, described himself as a «radical atheist.» When asked about that in an interview, he said that he used the term «radical» rather loosely, just for emphasis, and went on: If you describe yourself as “atheist,” some people will say, “Don’t you mean ‘agnostic’?” I have to reply that I really do mean atheist, I really do not believe that there is a god; in fact, I am convinced that there is not a god (a subtle difference). I see not a shred of evidence to suggest that there is one … etc., etc. It’s easier to say that I am a radical atheist, just to signal that I really mean it, have thought about it a great deal, and that it’s an opinion I hold seriously.

Interestingly, I don’t see radical and militant as meaning the same thing in the context of atheist, and admire his wording and reasoning.

-

#30

No-one here was describing them that way. We have described the literal meaning and tried to clarify with respect to «god» vs spirituality and belief and so on.

I only mentioned, as a caution, that some «religious» people think that way so the OP would know of that group and their meaning of the word «atheist», and how negatively it can occasionally be.

I didn’t mean that all atheists are described that way, but you were (seemed) most definitely clear about your opinion when you said:

Most atheists I know leave religious people to their own beliefs, although there are «militant atheists» (like militant/fundamental proselytizing religious fanatics) that seem to have given us a bad reputation, but there is little we can do to educate them as to the original meaning of the word.

If «militant» doesn’t modify «atheist» the same way it does «religious fanatic» then why use the word in the first place? All it does is fuel the misconception of atheism within the religious, and thereby distort discussion on the related topics.

-

#31

Yes, you have a point there, although perhaps unbeliever is still different from infidel or pagan or heathen. I was thinking of a self-description rather than an other-description.

A good distinction, Nat, though I think I was looking at it from a self-description angle anyway. Interpretation of words can be very subjective, of course, but if I were an atheist in a society where atheists are in a minority, I still don’t think I’d use unbeliever.

Firstly, it doesn’t mention religion. The very use of the word (for that purpose) would assume that ‘belief’ is intrinsically linked to religion — something an atheist would be unlikely to accept. To an atheist, saying «I’m an unbeliever» might be akin to saying «I’m someone who is sceptical about everything».

Secondly, the «un-« gives it a negative feel, as though «believer» is some sort of natural state, and «unbeliever» is a deviation from that state — again unlikely to be the view of an atheist. I know that, etymologically, «atheist» could be said to be the same, but for most English speakers the Greek prefix a- doesn’t have the same negative impact as un-.

Just my view.

Ws

-

#32

Interestingly, I don’t see radical and militant as meaning the same thing in the context of atheist, and admire his wording and reasoning.

![Smile :) :)]()

But you should remember that some will argue that just as some religion is interpreted as mandating specific «aggression» (for lack of a better term) so does atheism mandate the same, and they will follow that up with atheists having committed crimes against humanity. The difference being — and this is why I pointed out the distinction between [not having belief X] and [believing «the opposite» of belief X], the latter actually being a belief system — that religion is a belief system that can mandate aggression, whereas atheism is just the lack of something which means it is not able to do the same. In other words while atheists may be just as poorly behaving as religious people it can’t be because of what atheism mandates, because it mandates nothing. It’s just a lack of belief.

But by using the words «radical» and «militant» in conjunction with «atheism» some people will feel the above argument is validated and reinforced, regardless of how nonsensical it is.

-

#33

I believe Julian Stuart made a valid point. There are connotations that are worth understanding when asking about the meaning and use of a word. There are people who conflate «religious» and «fanatic», just as there are people who conflate «militant» and «atheist». Julian Stuart was very diligent to point out that these people are loading the words with their own views. Nevertheless, it’s worth knowing that when some people say «religious» they mean far more than religious and when some people say «atheist» they mean far more than atheist.

-

#34

I believe Julian Stuart made a valid point. There are connotations that are worth understanding when asking about the meaning and use of a word.

I’m not arguing that. I’m arguing him then saying that there actually are militant atheists. Are there?

-

#35

@MattiasNYC : I guess it all depends on whether you see atheism as «not believing there are any gods» or «believing there are not any gods».

I wouldn’t describe myself as either radical or militant; but when JWs knock on my door and try to convert me (though usually very politely), I always return the favour by demonstrating the fallacy of their arguments (also politely, and of course in vain). In effect I’m arguing the case for atheism. Am I being just a teensy bit militant? Maybe (but politely).

Ws

-

#36

Maybe I don’t fully comprehend the definition of «militant» then.

-

#37

I’m not arguing that. I’m arguing him then saying that there actually are militant atheists. Are there?

The facebook page I quoted from is here (https://www.facebook.com/FFAF.International — Freedom From Atheism Foundation). These religious people feel strongly that atheists are militant. Whether they feel that all of them are, it is hard to say. Sample at your own risk

-

#39

I am inspired to agree with you Mattias despite not having caught up with the thread. I read it yesterday and wanted to think about it. My comment at this point and in direct response to yours above is that I would rarely describe myself as an atheist in general conversation, although I am one. it’s very rare that the topic of religion occurs in my everyday life.

Depending on the context, I say I’m a ‘humanist’. I might say I’m an ‘agnostic’. It depends on my mood, and who I’m talking to. I certainly turn ‘militant’ and ‘atheist’ if some fanatic tries to push their religion (or those views that derive from it which threaten my democratic rights) down my throat.

Otherwise my belief system is nobody else’s business if the topic is deliberately introduced, or, I don’t want to upset anybody else if it accidentally crops up. The word ‘atheist’ in my experience makes many people uneasy and distresses some. When I lived in NYC, I was even more careful what I said, as careful as what I said about my political views. Luckily most of the people we associated with at that time, and now in the UK, both at work and friendly socialising are people very like us or not at all interested.

The UK is notoriously ‘ungodly’. Astonishingly few people in surveys say they believe in the Christian god, although many more use the Anglican church for life events like marriages, christenings and burials. Other sorts of Christian, the ‘non-established’ congregations, tend to be more committed to their faith. Naturally, people who belong to the non-established, non- conformist Christian groups in the UK tend not to ‘conform’ socially.They are not usually members of the upper middle class, aristocratic proto-typical ‘establishment’. They tend to be left-wing and ‘liberal’ or socialist. Since the ‘establishment’ incorporates a Christian church with the monarch at its head, people who are not members of this particular church tend to have different attitudes from those who are. Very often if not always in the past the non conformists were non-land owning working class people, struggling to survive in the face of landowner and industrialist exploitation.

Added content- it has to be remembered that it’s relatively recent in historical terms that religious non-conformists could vote and get government jobs. They were outsiders.

Last edited: Sep 4, 2015

-

#40

Maybe I don’t fully comprehend the definition of «militant» then.

I was using it in the sense of «favouring confrontational methods in support of a social cause», and I did say «a teensy bit». I meant that my use of counter-arguments might be seen as slightly confrontational, and that my desire to refute their claims might be seen as a social cause (not an organised cause, but a cause nonetheless).

Apparently I’m not alone in seeing ‘militant’ in that way …

I certainly turn ‘militant’ and atheist if some fanatic tries to push their religion (or the views that derive from it which threaten my democratic rights) down my throat.

Ws

-

#41

I just say that I’m not religious.

-

#42

I was using it in the sense of «favouring confrontational methods in support of a social cause», and I did say «a teensy bit». I meant that my use of counter-arguments might be seen as slightly confrontational, and that my desire to refute their claims might be seen as a social cause (not an organised cause, but a cause nonetheless).

Apparently I’m not alone in seeing ‘militant’ in that way …

Ws

I understand. I think I need to look at the word differently then. Though I maintain it is an unfortunately ‘vague’ term, especially considering the tie to the word «military».

Table of Contents

- What is another word for religious belief?

- What is no religion called?

- What is religious discrimination?

- How do you prove religious discrimination?

- What is religious discrimination in the workplace?

- What is a reasonable religious accommodation?

- Can I sue for religious discrimination?

- Can an employer ask for proof of religion?

- Is it illegal to make someone work on a religious holiday?

- Can you call off work for religious reasons?

- What is religious harassment?

- Can I refuse to work Saturdays?

- What are the advantages of allowing staff to express their religious values in the workplace?

- What are potential risks of allowing religious expression in the workplace?

- How do you address a religious background learner?

- Can teachers talk about God in school?

- What is religious diversity?

- How do you incorporate religion in the classroom?

- Can teachers share their religious beliefs?

- Can a teacher display a student’s religious work?

- Why is religious education important in schools?

Secular things are not religious. Anything not affiliated with a church or faith can be called secular. Non–religious people can be called atheists or agnostics, but to describe things, activities, or attitudes that have nothing to do with religion, you can use the word secular.

What is another word for religious belief?

| creed | faith |

|---|---|

| dogma | ideology |

| piety | orthodoxy |

| spirituality | devotion |

| doctrine | piousness |

What is no religion called?

No religion may refer to: Irreligion, absence of, or indifference towards religion. Atheism, the absence of belief of the existence of deities. Agnosticism, the position that the existence of deities is unknown or unknowable.

What is religious discrimination?

Religious discrimination involves treating a person (an applicant or employee) unfavorably because of his or her religious beliefs. … Religious discrimination can also involve treating someone differently because that person is married to (or associated with) an individual of a particular religion.

How do you prove religious discrimination?

To prove you have been discriminated against because of your religious attire, you first have to show three things: 1) your sincere religious belief requires you to wear certain attire, 2) your employer (or potential employer) has indicated that wearing the religious attire conflicts with a job requirement, and that …

What is religious discrimination in the workplace?

Religious discrimination, in the context of employment, is treating employees differently because of their religion, religious beliefs or practices, and/or their request for accommodation —a change in a workplace rule or policy— for their religious beliefs and practices.

What is a reasonable religious accommodation?

A reasonable religious accommodation is any adjustment to the work environment that will allow an employee to practice their religious beliefs. This applies not only to schedule changes or leave for religious observances, but also to such things as dress or grooming practices that an employee has for religious reasons.

Can I sue for religious discrimination?

If you believe your were treated unfairly in the workplace on the basis of your religious beliefs, you may be able to file a discrimination charge with the EEOC, which will investigate your charge and either sue the employer or give you the option of doing so.

Can an employer ask for proof of religion?

Employees do not have to justify or prove anything about their religious belief to the employer (for example, the employee need not provide a note from clergy): an employer is required to accommodate – subject to the undue hardship rule – any of the employee’s sincerely-held religious beliefs.

Is it illegal to make someone work on a religious holiday?

There is no federal law that requires an employer to give employees days off for religious holidays; however, under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, employers may not treat employees differently because of their religion affiliations, and employees cannot be required to participate or not participate in …

Can you call off work for religious reasons?

U.S. law clearly states that employers cannot discriminate on the basis of religion and must make reasonable accommodations for religious needs. But unfortunately, not all managers are willing to work with their employees—and some can make your life pretty difficult when they do.

What is religious harassment?

Religious beliefs harassment occurs when you are the target of offensive or negative remarks about your faith and how you practice it, consistent unwelcome comments on your religion and religious comments that create a hostile work environment. You can also be the victim of “quid pro quo” religious harassment.

Can I refuse to work Saturdays?

A Unless you have a written contract specifying that you would not have to work weekends, your employer may require you–as well as other employees–to work weekends. … Your refusal to work weekends would probably be deemed insubordination and could lead to your termination.

What are the advantages of allowing staff to express their religious values in the workplace?

It doesn’t have to be that way. Businesses have the opportunity to foster religious respect in the workplace. And, in doing so, according to many experts, companies can find bottom line results from increased employee satisfaction, strengthened loyalty and commitment and increased productivity.

What are potential risks of allowing religious expression in the workplace?

The danger of allowing religious-based meetings in the workplace is that those meetings, alone or combined with other anecdotal evidence, may give an employee the subjective belief that an employment action was taken because of religion.

How do you address a religious background learner?

How Do You Approach Discussing Your Religious Beliefs With Students?

- Be honest about what you believe. One route is to be honest but brief about your own religious identity. …

- Shut it down. …

- Deflect or change the subject. …

- Ignore the question.

Can teachers talk about God in school?

As agents of the government, teachers cannot inculcate religion at school, so they cannot lead students in prayer during class. But they also are private citizens with rights to free speech — and many interpret that to mean they can pray with students at church on Sunday, for example.

What is religious diversity?

Religious diversity is the fact that there are significant differences in religious belief and practice. It has always been recognized by people outside the smallest and most isolated communities. … In contrast, exclusivist approaches say that only one religion is uniquely valuable.

How do you incorporate religion in the classroom?

How to Teach About World Religions in Schools

- Just observe on field trips. …

- Pick someone neutral and knowledgeable for guest talks on religion. …

- Be an active moderator of any guest speaker on religion, including parents. …

- Avoid dress-up exercises in the classroom. …

- Stay away from anything else that resembles simulating ritual in class.

Teachers, as agents of the government, may not inculcate students in religious matters. Otherwise, they run afoul of the establishment clause. However, this does not mean that teachers can never speak about religion, for religion is an important part of history, culture and current events.

Can a teacher display a student’s religious work?

Religious Messages: Schools may not permanently display religious messages like the Ten Commandments. Stone v. Graham (1980). They may, however, display religious symbols in teaching about religion, as long as they are used as teaching aids on a temporary basis as part of an academic program.

Why is religious education important in schools?

Learning about religion and learning from religion are important for all pupils, as religious education (RE) helps pupils develop an understanding of themselves and others. RE promotes the spiritual, moral, social and cultural development of individuals and of groups and communities.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Irreligious» redirects here. For the album by Moonspell, see Irreligious (album).

Irreligion is the neglect or active rejection of religion and, depending on the definition, a simple lack of religion.

Irreligion takes many forms, ranging from the casual and unaware to full-fledged philosophies such as atheism and agnosticism, secular humanism and antitheism. Social scientists[who?] tend to define irreligion as a purely naturalist worldview that excludes a belief in anything supernatural. The broadest and loosest definition, serving as an upper limit, is the lack of religious identification, though many non-identifiers express metaphysical and even religious beliefs. The narrowest and strictest is subscribing to positive atheism.

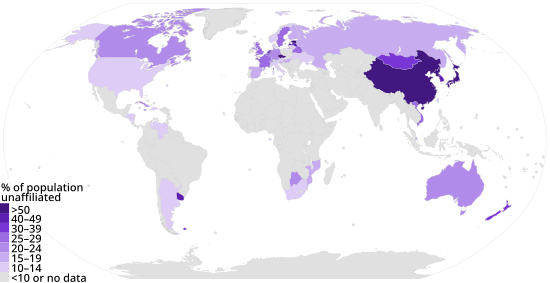

According to the Pew Research Center’s 2012 global study of 230 countries and territories, 16% of the world’s population does not identify with any religion.[1] The population of the religiously unaffiliated, sometimes referred to as «nones», has grown significantly in recent years.[2] Measurement of irreligiosity requires great cultural sensitivity, especially outside the West, where the concepts of «religion» or «the secular» are not always rooted in local culture.[3]

Etymology[edit]

The term irreligion is a combination of the noun religion and the ir- form of the prefix in-, signifying «not» (similar to irrelevant). It was first attested in French as irréligion in 1527, then in English as irreligion in 1598. It was borrowed into Dutch as irreligie in the 17th century, though it is not certain from which language.[4]

Definition[edit]

Irreligion is defined as a rejection of religion, but whether it is distinct from lack of religion is disputed.

The Encyclopedia of religion and society defines it as the «rejection of religion in general or any of its more specific organized forms, as distinct from absence of religion»;[5] while the Oxford English dictionary defines it as want of religion; hostility to or disregard of religious principles; irreligious conduct;[6] and the Merriam Webster dictionary defines it as «neglectful of religion : lacking religious emotions, doctrines, or practices».[7]

Types[edit]

- Agnostic atheism is a philosophical position that encompasses both atheism and agnosticism. Agnostic atheists are atheistic because they do not hold a belief in the existence of any deity and agnostic because they claim that the existence of a deity is either unknowable in principle or currently unknown in fact.

- Agnosticism is the view that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable.

- Alatrism or alatry (Greek: from the privative ἀ— + λατρεία (latreia) = worship) is the recognition of the existence of one or more gods, but with a deliberate lack of worship of any deity. Typically, it includes the belief that religious rituals have no supernatural significance, and that gods ignore all prayers and worship.

- Antireligion is opposition or rejection of religion of any kind.

- Apatheism is the attitude of apathy or indifference towards the existence or non-existence of god(s).

- Atheism is the lack of belief that any deities exist or, in a narrower sense, positive atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities. There are ranges from negative and positive atheism.

- Antitheism is the opposition to theism. The term has had a range of applications. It typically refers to direct opposition to the belief in any deity.

- Deism is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation of the natural world are exclusively logical, reliable, and sufficient to determine the existence of a Supreme Being as the creator of the universe.

- Freethought holds that positions regarding truth should be formed on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism, rather than authority, tradition, revelation, or other dogma.

- Ignosticism, also known as igtheism, is the idea that the question of the existence of God is meaningless because the word «God» has no coherent and unambiguous definition.

- Naturalism is the idea or belief that only natural (as opposed to supernatural or spiritual) laws and forces operate in the universe.

- Secular humanism is a system of thought that prioritizes human rather than divine matters.

- Post-theism is a variant of nontheism that proposes that the division of theism vs. atheism is obsolete, that God belongs to a stage of human development now past. Within nontheism, post-theism can be contrasted with antitheism.

- Secularism is overwhelmingly used to describe a political conviction in favour of minimizing religion in the public sphere, that may be advocated regardless of personal religiosity. Yet it is sometimes, especially in the United States, also a synonym for naturalism or atheism.[8]

- «Spiritual but not religious» (SBNR) is a designation coined by Robert C. Fuller for people who reject traditional or organized religion but have strong metaphysical beliefs. The SBNR may be included under the definition of nonreligion,[9] but are sometimes classified as a wholly distinct group.[10]

- Theological noncognitivism is the argument that religious language – specifically, words such as God – are not cognitively meaningful. It is sometimes considered as synonymous with ignosticism.

- Transtheism, refers to a system of thought or religious philosophy that is neither theistic nor atheistic, but is beyond them.

Human rights[edit]

In 1993, the UN’s human rights committee declared that article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights «protects theistic, non-theistic and atheistic beliefs, as well as the right not to profess any religion or belief.»[11] The committee further stated that «the freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief necessarily entails the freedom to choose a religion or belief, including the right to replace one’s current religion or belief with another or to adopt atheistic views.» Signatories to the convention are barred from «the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers» to recant their beliefs or convert.[12][13]

Most democracies protect the freedom of religion, and it is largely implied in respective legal systems that those who do not believe or observe any religion are allowed freedom of thought.

A noted exception to ambiguity, explicitly allowing non-religion, is Article 36 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (as adopted in 1982), which states that «No state organ, public organization or individual may compel citizens to believe in, or not to believe in, any religion; nor may they discriminate against citizens who believe in, or do not believe in, any religion.»[14] Article 46 of China’s 1978 Constitution was even more explicit, stating that «Citizens enjoy freedom to believe in religion and freedom not to believe in religion and to propagate atheism.»[15]

Demographics[edit]

Although 11 countries listed below have nonreligious majorities, it does not necessary correlate with non-identification. For example, 58% of the Swedish population identify with the Lutheran Church.[17] Also, though Scandinavian countries have among the highest measures of nonreligiosity and even atheism in Europe, 47% of atheists who live in those countries are still formally members of the national churches.[18]

Determining objective irreligion, as part of societal or individual levels of secularity and religiosity, requires cultural sensitivity from researchers. This is especially so outside the West, where the Western Christian concepts of «religious» and «secular» are not rooted in local civilization. Many East Asians identify as «without religion» (wú zōngjiào in Chinese, mu shūkyō in Japanese, mu jong-gyo in Korean), but «religion» in that context refers only to Buddhism or Christianity. Most of the people «without religion» practice Shinto and other folk religions. In the Muslim world, those who claim to be «not religious» mostly imply not strictly observing Islam, and in Israel, being «secular» means not strictly observing Orthodox Judaism. Vice versa, many American Jews share the worldviews of nonreligious people though affiliated with a Jewish denomination, and in Russia, growing identification with Eastern Orthodoxy is mainly motivated by cultural and nationalist considerations, without much concrete belief.[19]

A Pew 2015 global projection study for religion and nonreligion, projects that between 2010 and 2050, there will be some initial increases of the unaffiliated followed by a decline by 2050 due to lower global fertility rates among this demographic.[20] Sociologist Phil Zuckerman’s global studies on atheism have indicated that global atheism may be in decline due to irreligious countries having the lowest birth rates in the world and religious countries having higher birth rates in general.[21] Since religion and fertility are positively related and vice versa, non-religious identity is expected to decline as a proportion of the global population throughout the 21st century.[22] By 2060, according to projections, the number of unaffiliated will increase by over 35 million, but the percentage will decrease to 13% because the total population will grow faster.[23][24]

According to Pew Research Center’s 2012 global study of 230 countries and territories, 16% of the world’s population is not affiliated with a religion, while 84% are affiliated.[1] A 2012 Worldwide Independent Network/Gallup International Association report on a poll from 57 countries reported that 59% of the world’s population identified as religious person, 23% as not religious person, 13% as «convinced atheists», and also a 9% decrease in identification as «religious» when compared to the 2005 average from 39 countries.[25] Their follow-up report, based on a poll in 2015, found that 63% of the globe identified as religious person, 22% as not religious person, and 11% as «convinced atheists».[26] Their 2017 report found that 62% of the globe identified as religious person, 25% as not religious person, and 9% as «convinced atheists».[27] However, researchers have advised caution with the WIN/Gallup International figures since other surveys which use the same wording, have conducted many waves for decades, and have a bigger sample size, such as World Values Survey; have consistently reached lower figures for the number of atheists worldwide.[28] In 2020, the World Religion Database estimated that the countries with the highest percentage of atheists were North Korea and Sweden.[29]

Being nonreligious is not necessarily equivalent to being an atheist or agnostic. Pew Research Center’s global study from 2012 noted that many of the nonreligious actually have some religious beliefs. For example, they observed that «belief in God or a higher power is shared by 7% of Chinese unaffiliated adults, 30% of French unaffiliated adults and 68% of unaffiliated U.S. adults.»[30] Being unaffiliated with a religion on polls does not automatically mean objectively nonreligious since there are, for example, unaffiliated people who fall under religious measures and vice versa.[31] Out of the global nonreligious population, 76% reside in Asia and the Pacific, while the remainder reside in Europe (12%), North America (5%), Latin America and the Caribbean (4%), sub-Saharan Africa (2%) and the Middle East and North Africa (less than 1%).[30]

The term «nones» is sometimes used in the U.S. to refer to those who are unaffiliated with any organized religion. This use derives from surveys of religious affiliation, in which «None» (or «None of the above») is typically the last choice. Since this status refers to lack of organizational affiliation rather than lack of personal belief, it is a more specific concept than irreligion. A 2015 Gallup poll concluded that in the U.S. «nones» were the only «religious» group that was growing as a percentage of the population.[32]

By population[edit]

The Pew Research Centre in the table below reflects «religiously unaffiliated» which «include atheists, agnostics and people who do not identify with any particular religion in surveys».

The Zuckerman data on the table below only reflect the number of people who have an absence of belief in a deity only (atheists, agnostics). Does not include the broader number of people who do not identify with a religion such as deists, spiritual but not religious, pantheists, New Age spiritualism, etc.

| Country | Pew (2012)[41] | Zuckerman (2004)[42][43] |

|---|---|---|

| 700,680,000 | 103,907,840 – 181,838,720 | |

| 102,870,000 | ||

| 72,120,000 | 81,493,120 – 82,766,450 | |

| 26,040,000 | 66,978,900 | |

| 23,180,000 | 34,507,680 – 69,015,360 | |

| 20,350,000 | 33,794,250 – 40,388,250 | |

| 17,580,000 | 25,982,320 – 32,628,960 | |

| 18,684,010 – 26,519,240 | ||

| 22,350,000 | 14,579,400 – 25,270,960 | |

| 9,546,400 | ||

| 50,980,000 | 8,790,840 – 26,822,520 | |

| 6,364,020 – 7,179,920 | ||

| 6,176,520 – 9,752,400 | ||

| 6,042,150 – 9,667,440 | ||

| 5,460,000 | ||

| 5,240,000 | ||

| 5,328,940 – 6,250,121 | ||

| 4,779,120 – 4,978,250 | ||

| 4,346,160 – 4,449,640 | ||

| 4,133,560 – 7,638,100 | ||

| 3,483,420 – 8,708,550 | ||

| 17,350,000 | 3,404,700 | |

| 3,210,240 – 4,614,720 | ||

| 2,556,120 – 3,007,200 | ||

| 2,327,590 – 4,330,400 | ||

| 1,956,990 — 6,320,550 | ||

| 1,752,870 | ||

| 1,703,680 | ||

| 1,665,840 – 1,817,280 | ||

| 1,565,800 – 3,131,600 | ||

| 1,471,500 – 2,125,500 | ||

| 1,460,200 – 3,129,000 | ||

| 1,418,250 – 3,294,000 | ||

| 1,266,670 – 2,011,770 | ||

| 929,850 – 2,293,630 | ||

| 798,800 – 878,680 | ||

| 791,630 | ||

| 703,850 – 764,180 | ||

| 657,580 | ||

| 618,380 | ||

| 566,020 | ||

| 542,400 – 1,518,720 | ||

| 469,040 | ||

| 461,200 – 668,740 | ||

| 420,960 – 947,160 | ||

| 118,740 | ||

| 407,880 | ||

| 355,670 | ||

| 314,790 | ||

| 283,600 | ||

| 247,590 | ||

| 47,040 – 67,620 | ||

| 15,410,000 |

Historical trends[edit]

According to political/social scientist Ronald F. Inglehart, «influential thinkers from Karl Marx to Max Weber to Émile Durkheim predicted that the spread of scientific knowledge would dispel religion throughout the world», but religion continued to prosper in most places during the 19th and 20th centuries.[44] Inglehart and Pippa Norris argue faith is «more emotional than cognitive», and advance an alternative thesis termed «existential security.» They postulate that rather than knowledge or ignorance of scientific learning, it is the weakness or vulnerability of a society that determines religiosity. They claim that increased poverty and chaos make religious values more important to a society, while wealth and security diminish its role. As need for religious support diminishes, there is less willingness to «accept its constraints, including keeping women in the kitchen and gay people in the closet».[45]

Prior to the 1980s[edit]

Rates of people identifying as non-religious began rising in most societies as least as early as the turn of the 20th century.[46] In 1968, sociologist Glenn M. Vernon wrote that US census respondents who identified as «no religion» were insufficiently defined because they were defined in terms of a negative. He contrasted the label with the term «independent» for political affiliation, which still includes people who participate in civic activities. He suggested this difficulty in definition was partially due to the dilemma of defining religious activity beyond membership, attendance, or other identification with a formal religious group.[46] During the 1970s, social scientists still tended to describe irreligion from a perspective that considered religion as normative for humans. Irreligion was described in terms of hostility, reactivity, or indifference toward religion, and or as developing from radical theologies.[47]

1981–2019[edit]

In a study of religious trends in 49 countries from 1981 to 2019, Inglehart and Norris found an overall increase in religiosity from 1981 to 2007. Respondents in 33 of 49 countries rated themselves higher on a scale from one to ten when asked how important God was in their lives. This increase occurred in most former communist and developing countries, but also in some high-income countries. A sharp reversal of the global trend occurred from 2007 to 2019, when 43 out of 49 countries studied became less religious. This reversal appeared across most of the world.[44] The United States was a dramatic example of declining religiosity – with the mean rating of importance of religion dropping from 8.2 to 4.6 – while India was a major exception. Research in 1989 recorded disparities in religious adherence for different faith groups, with people from Christian and tribal traditions leaving religion at a greater rate than those from Muslim, Hindu, or Buddhist faiths.[48]

Inglehart and Norris speculate that the decline in religiosity comes from a decline in the social need for traditional gender and sexual norms, («virtually all world religions instilled» pro-fertility norms such as «producing as many children as possible and discouraged divorce, abortion, homosexuality, contraception, and any sexual behavior not linked to reproduction» in their adherents for centuries) as life expectancy rose and infant mortality dropped. They also argue that the idea that religion was necessary to prevent a collapse of social cohesion and public morality was belied by lower levels of corruption and murder in less religious countries. They argue that both of these trends are based on the theory that as societies develop, survival becomes more secure: starvation, once pervasive, becomes uncommon; life expectancy increases; murder and other forms of violence diminish. As this level of security rises, there is less social/economic need for the high birthrates that religion encourages and less emotional need for the comfort of religious belief.[44] Change in acceptance of «divorce, abortion, and homosexuality» has been measured by the World Values Survey and shown to have grown throughout the world outside of Muslim-majority countries.[44]

See also[edit]

- Antireligion

- Importance of religion by country

- Infidel

- Laїcité

- Pantheism

- Post-theism

- Secular religion

- Transtheism

References[edit]

- ^ a b Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life (18 December 2012). «The Global Religious Landscape». Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Lipka, Michael (2 April 2015). «7 Key Changes in the Global Religious Landscape». Pew Research Center.

- ^ Zuckerman, Phil; Galen, Luke W.; Pasquale, Frank L. (2016). «Secularity Around the World». In: The Nonreligious: Understanding Secular People and Societies. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 6–8, 13–15, 32–34.

- ^ «Irreligie». Instituut voor Nederlandse Lexicologie. Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal. 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Campbell, Colin (1998). «Irreligion». In Swatos, William H., Jr. (ed.). Encyclopedia of religion and society. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press. p. 239. ISBN 0-7619-8956-0. OCLC 37361790.

- ^ «irreligion». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Merriam Webster, irreligious

- ^ Jacques Berlinerblau, How to be Secular: A Field Guide for Religious Moderates, Atheists and Agnostics (2012, Houghton-Mifflin Harcourt). p. 53.

- ^ Zuckerman, Galen et al., p. 119.

- ^ Zuckerman, Shook, (in bibliography), p. 575.

- ^ «CCPR General Comment 22: 30/07/93 on ICCPR Article 18». Minorityrights.org. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015.

- ^ International Federation for Human Rights (1 August 2003). «Discrimination against religious minorities in Iran» (PDF). fdih.org. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ^ Davis, Derek H. «The Evolution of Religious Liberty as a Universal Human Right» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ^ «CHAPTER TWO – THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND DUTIES OF CITIZENS». Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ 中华人民共和国宪法 (1978年) [People’s Republic of China 1978 Constitution] (in Chinese). 1978. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ «Religious Composition by Country, 2010–2050». Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ «Statistik». www.svenskakyrkan.se.

- ^ Zuckerman, Phil, ed. (2010). «Ch. 9 Atheism And Secularity: The Scandinavian Paradox». Atheism and Secularity Vol.2. Praeger. ISBN 978-0313351815.

- ^ Zuckerman, Galen et al., «Secularity Around the World». pp. 30–32, 37–40, 44, 50–51.

- ^ «The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010–2050». Pew Research Center. 5 April 2012.

- ^ Zuckerman, Phil (2007). Martin, Michael (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Atheism. Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0521603676.

- ^ Ellis, Lee; Hoskin, Anthony W.; Dutton, Edward; Nyborg, Helmuth (8 March 2017). «The Future of Secularism: a Biologically Informed Theory Supplemented with Cross-Cultural Evidence». Evolutionary Psychological Science. 3 (3): 224–43. doi:10.1007/s40806-017-0090-z. S2CID 88509159.

- ^ «Why People With No Religion Are Projected To Decline As A Share Of The World’s Population». Pew Research Center. 7 April 2017.

- ^ «The Changing Global Religious Landscape: Babies Born to Muslims will Begin to Outnumber Christian Births by 2035; People with No Religion Face a Birth Dearth». Pew Research Center. 5 April 2017.

- ^ «Global Index of Religion and Atheism» (PDF). WIN/Gallup International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ «Losing our Religion? Two Thirds of People Still Claim to be Religious» (PDF). WIN/Gallup International. 13 April 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2015.

- ^ «Religion prevails in the world» (PDF). WIN/Gallup International. 14 November 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Keysar, Ariela; Navarro-Rivera, Juhem (2017). «36. A World of Atheism: Global Demographics». In Bullivant, Stephen; Ruse, Michael (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Atheism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199644650.

- ^ «Atheist World Rankings». ARDA. 19 April 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ a b «Religiously Unaffiliated». The Global Religious Landscape. Pew Research Center: Religion & Public Life. 18 December 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Todd; Zurlo, Gina (2016). «Unaffiliated, Yet Religious: A Methodological and Demographic Analysis». In Cipriani, Roberto; Garelli, Franco (eds.). Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion: Volume 7: Sociology of Atheism. Leiden: Brill. pp. 56The intersection of religion among the global uaffliated –60. ISBN 9789004317536.

- ^ Inc, Gallup (24 December 2015). «Percentage of Christians in U.S. Drifting Down, but Still High». Gallup.com.

- ^ Keysar, Ariela; Navarro-Rivera, Juhem (2017). «36. A World of Atheism: Global Demographics». In Bullivant, Stephen; Ruse, Michael (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Atheism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199644650.

- ^ «Global Religious Landscape» (PDF). Pew Research Center. 18 December 2012. pp. 45–50.

- ^ «Religion prevails in the world» (PDF). Gallup International. 14 November 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ «Losing our Religion? Two-Thirds of People Still Claim to be Religious» (PDF). WIN/Gallup International. 13 April 2015.

- ^ «WIN-Gallup International ‘Religiosity and Atheism Index’ reveals atheists are a small minority in the early years of 21st century». WIN-Gallup International. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ «GLOBAL INDEX OF RELIGIOSITY AND ATHEISM – 2012» (PDF). WIN-Gallup International. 27 July 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Dentsu Communication Institute 電通総研・日本リサーチセンター編「世界60カ国価値観データブック (in Japanese)

- ^ Zuckerman, Phil (2006). «Atheism: Contemporary Numbers and Patterns». In Martin, Michael (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Atheism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–66. ISBN 9780521842709.

- ^ «Religiously Unaffiliated». 18 December 2012.

- ^ «The Cambridge Companion to Atheism – PDF Drive».

- ^ «81-F77-Aeb-A404-447-C-8-B95-Dd57-Adc11-E98».

- ^ a b c d Inglehart, Ronald F. (September–October 2020). «Giving Up on God The Global Decline of Religion». Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Ikenberry, G. John (November–December 2004). «Book review. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide». Foreign Affairs. doi:10.2307/20034150. JSTOR 20034150. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ a b Vernon, Glenn M. (1968). «The Religious «Nones»: A Neglected Category». Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 7 (2): 219–229. doi:10.2307/1384629. JSTOR 1384629.

- ^ Schumaker, John F. (1992). Religion and Mental Health. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-19-506985-4.

- ^ Duke, James T.; Johnson, Barry L. (1989). «The Stages of Religious Transformation: A Study of 200 Nations». Review of Religious Research. 30 (3): 209–224. doi:10.2307/3511506. JSTOR 3511506.

Bibliography[edit]

- Coleman, Thomas J.; Hood, Ralph W.; Streib, Heinz (2018). «An introduction to atheism, agnosticism, and nonreligious worldviews». Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 10 (3): 203–206. doi:10.1037/rel0000213. S2CID 149580199.

- Arie Johan Vanderjagt, Richard Henry Popkin, ed. (1993). Scepticism and irreligion in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09596-0.

- Eric Wright (2010). Irreligion: Thought, Rationale, History. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-171-06863-1.

- Dillon, Michele (2015). «Christian Affiliation and Disaffiliation in the United States: Generational and Cultural Change». In Hunt, Stephen J. (ed.). Handbook of Global Contemporary Christianity: Themes and Developments in Culture, Politics, and Society. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 10. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 346–365. doi:10.1163/9789004291027_019. ISBN 978-90-04-26538-7. ISSN 1874-6691.

- Eller, Jack David (2010). «What Is Atheism?». In Zuckerman, Phil (ed.). Atheism and Secularity. Volume 1: Issues, Concepts, Definitions. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-0-313-35183-9.

- ——— (2017). «Varieties of Secular Experience». In Zuckerman, Phil; Shook, John R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Secularism. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 499ff. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199988457.013.31. ISBN 978-0-19-998845-7.

- Glasner, Peter E. (1977). The Sociology of Secularisation: A Critique of a Concept. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-8455-2.

- Iversen, Hans Raun (2013). «Secularization, Secularity, Secularism». In Runehov, Anne L. C.; Oviedo, Lluis (eds.). Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. pp. 2116–2121. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8265-8_1024. ISBN 978-1-4020-8265-8.

- Josephson, Jason Ānanda (2012). The Invention of Religion in Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226412337.

- Lois Lee, Secular or nonreligious? Investigating and interpreting generic ‘not religious’ categories and populations. Religion, Vol. 44, no. 3. October 2013.

- Mullins, Mark R. (2011). «Religion in Contemporary Japanese Lives». In Lyon Bestor, Victoria; Bestor, Theodore C.; Yamagata, Akiko (eds.). Routledge Handbook of Japanese Culture and Society. Abingdon, England: Routledge. pp. 63–74. ISBN 978-0-415-43649-6.

- Schaffner, Caleb; Cragun, Ryan T. (2020). «Chapter 20: Non-Religion and Atheism». In Enstedt, Daniel; Larsson, Göran; Mantsinen, Teemu T. (eds.). Handbook of Leaving Religion. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 18. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 242–252. doi:10.1163/9789004331471_021. ISBN 978-90-04-33092-4. ISSN 1874-6691.

- Smith, James K. A. (2014). How (Not) to Be Secular: Reading Charles Tayor. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-8028-6761-2.

- Taylor, Charles (2007). A Secular Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02676-6.

- ——— (2011). «Why We Need a Radical Redefinition of Secularism». In Mendieta, Eduardo; VanAntwerpen, Jonathan (eds.). The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 34–59. ISBN 978-0-231-52725-5. JSTOR 10.7312/butl15645.6.

- Warner, Michael; VanAntwerpen, Jonathan; Calhoun, Craig, eds. (2010). Varieties of Secularism in a Secular Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04857-7.

- Zuckerman, Phil; Galen, Luke W.; Pasquale, Frank L. (2016). «Secularity Around the World». The Nonreligious: Understanding Secular People and Societies. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199924950.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-992494-3.

- Zuckerman, Phil; Shook, John R. (2017). «Introduction: The Study of Secularism». In Zuckerman, Phil; Shook, John R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Secularism. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–17. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199988457.013.1. ISBN 978-0-19-998845-7.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Irreligion.

- The Understanding Unbelief program in the University of Kent.

- «Will religion ever disappear?», from BBC Future, by Rachel Nuwer, in December 2014

Wiki User

∙ 10y ago

Best Answer

Copy

Often the word atheist is used to describe someone who rejects God or gods. The dictionary didn’t have a term for religion-less, however, that term could be used.

Wiki User

∙ 10y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: Is there another word for a person with no religion?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

No Word for Religion/Dharma

by Acharya Harish Chandra

October 2015

A community coins a word for something that matters to it. Sanskrit has no word for religion — a faith-based sectarian organization. Its essential elements include: 1) a founder, 2) a place of worship, and 3) a holy book. Dharma is a moral code of conduct for the entire humanity and if not followed then there will be a chaos. This is a Sanskrit word and the western languages don’t quite have a word for it. India was a land of Dharma and nothing to do with religion and the western world has no idea of Dharma. India went through a massive spiritual decline resulting into the MahaBharata War, coinciding with decline of Dharma. Interestingly, all religions took birth afterwards – the oldest being Zoroastrianism and Judaism, about 4500 years ago. Now we find ourselves in the midst of a plethora of religions, sects and sub-sects. Most of the wars are in the name of religion. A typical Hindu is utterly confused and believes Hinduism is a religion as opposed to Satya Sanatana Vedic Dharma. He is rushing towards shaping his religion in the three-fold box: 1) Founder: he doesn’t know it but then has cooked up a concept that God reincarnates such as Rama and Krishna, 2) Place of Worship: he is building newer and grander temples, and 3) Holy Book: he is confused and names Gita, or Ramayana or whatever comes handy and could even be Hanuman-Chalisa.

Arya Samaj should assert that we belong to Dharma. If forced upon to reveal the three-fold parameters then, we should say: God- the Dharma-Raj, Heart (not the pumping heart that circulates blood) but deep in skull where the soul resides, called Hrit in Sanskrit – the only place where one can meet God, and the Vedas. Arya Samaj Bhavan (also referred to as temples by some people) is merely a place of assembly and learning.