There may be a psychoacoustic reason for why notes of a high frequency are called high and notes of a low frequency are called low.

First, perception.

When high-frequency notes are sounded (from, say, a piccolo or a violin), the notes will resonate in the smaller cavities in your body (such as your head).

When low-frequency notes are sounded (say, from a double bass), the notes will resonate in the larger cavities in your body (such as your chest).

So the higher and lower pitches are felt not just in the ears, but in the higher and lower parts of your body. This perception may have given rise to the terms.

Second, production. In the vocal production of music, singers will shift between head voice and chest voice. Head voice is used for, you guessed it, higher notes. (Think the Bee Gees if you have a leisure suit in the back of your closet. Or your favorite coloratura soprano if you saw Lucia di Lammamore or The Magic Flute recently.) Chest voice, produced lower in the body, produces lower notes.

Third, there may also be historical reasons, dating back well before oscilloscopes.

Research into musical pitches extends at least back to Pythagoras (sixth century BC).

The word gamut come from Medieval Latin, with the root coming from gamma ut, where gamma referred to the bass G and ut referred to the first note in the lowest of the hexachords. (See Etymology online.) As the lowest note, it also has the lowest number (1).

Today, the middle A is called A4 (440Hz for many orchestras). It’s about the middle of the standard 88-key piano keyboard. The A to the left of it (an octave below) is called A3 and has half the frequency (220 Hz).

Could the numbers assigned to octaves from Pythagoras (sixth century BC) and adopted by Guido d’Arrezzo (sixteenth century) have naturally conferred the sense of low to a note? A gamut or G1 is lower in pitch than a G2, corresponding to its lower notation (a 1 versus a 2).

I don’t have enough breadth to know if high and low pitches work in language systems other than those derived from Proto-Indo-European. I seem to recall from Women Fire and Dangerous things that the word anger is widely associated with heat, in part because of the physiological response when one is angered, namely, that the body temperature actually rises. Lakoff’s book may give you some more insight into other linguistic universals.

-

#1

I am confused about what words to use to talk about dynamics (loud/soft) and pitch (high/low) in Spanish. I am not interested in musical terminology that comes from Latin such as forte/piano. I am wondering about layman’s terms, regular everyday words that could be used with people who have no musical background. In particular, I am interested in what would be easily understood in Mexico or Central/South America.

Thanks so much for any help you can offer!

-

#4

Oh yeah, good point, I meant Italian. Thanks for your help!

Could anyone please confirm guitaric60’s response—is the same terminology is used/understood in Mexico?

Early in my career, I wanted to teach my Kindergarten students about pitch and high vs. low, but my collection of songs that really demonstrate this was limited to 1!

So I did some searching and asking around and came up with these 5 easy high and low songs for Kindergarten.

Using high and low songs are an easy way to reinforce broad contrasting pitch concepts. Look for songs with clear high and low as well as lyrics which may reinforce the idea. My favorites include:

- Bounce High Bounce Low

- Higher Than A House

- Twinkle Twinkle

- Someone Standing

- See-Saw Up And Down

Look ahead for notation, analysis, games, and ways to use these songs to reinforce high and low.

Hate always searching for songs? Get 30 of my favorite songs with directions for activities by clicking the link.

Why Teach High And Low?

It can be hard to know what to teach in Kindergarten music, but one of the main approaches is to work on broad, contrasting concepts such as high vs. low.

Working on high and low in Kindergarten sets students up for success in future music years in the following ways:

- Works towards pitch awareness

- Improves matching pitch

- Precursor for learning notes

- Develops an understanding of pitch

- Increases listening skills

- Can be applied to voice or instruments

In this section, I’ll mention some great high/low songs for younger grades. I’ll include the following information for your reference:

- Notation

- Source/Link (where applicable)

- Game Directions (where applicable)

- Other notes

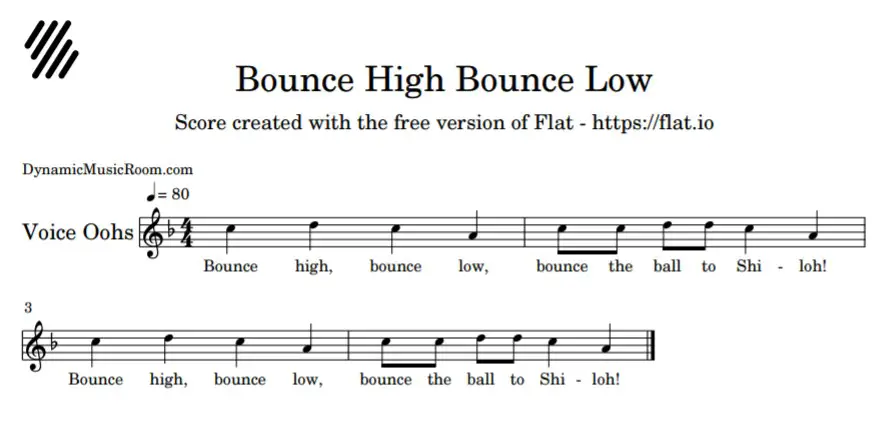

#1 Bounce High Bounce Low

Source/Link: American Folk Song Collection

Game Directions: There are 2 ways I like to play this game.

- Students bounce a ball on the word “bounce” and then pass the ball on the word “Shiloh.”

- Using a bean bag or soft, squishy ball, students toss the bag up for high, down for low, and then on to the next person.

Other notes: The melody of this song is simple, but it also shows high and low well. On top of this, the lyrics call out high and low when the melody goes high and low.

Further Reading: Name games for music class

#2 Higher Than A House

Source/Link: The Music Effect Book 2

Game Directions:

- Students move to show high and low based on the pitches of the song.

- The final phrase is changed by the leader, and the students have to show with their hands what the leader sings.

- The final phrase is changed every time to encourage students to listen better to the pitch.

- Leaders are switched to students after a while.

Other notes: The book also includes an interesting story and other visual aids.

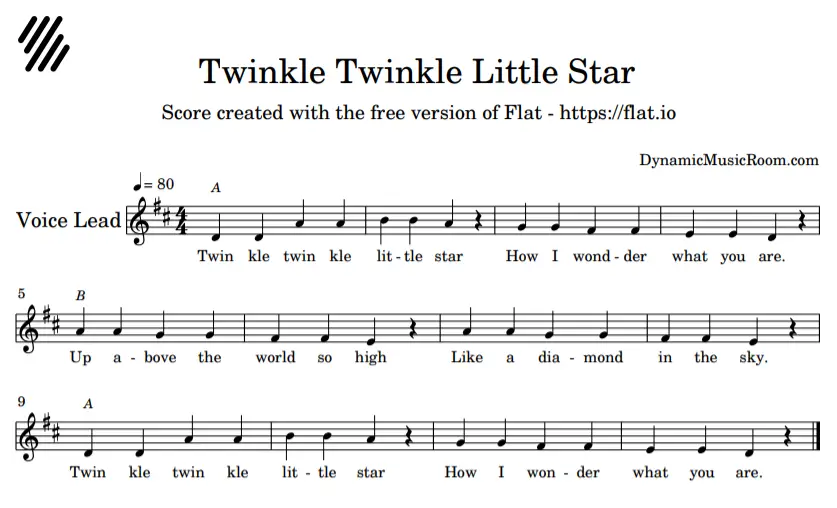

#3 Twinkle Twinkle

Source/Link: Traditional

Game Directions: No traditional “game” exists for this song, but here are a couple of ideas you may want to try.

- Perform different steady beat motions.

- Use hands in a star shape to show melodic contour.

- Create a movement B section of the song where students move to match you improvising high and low (look at Pitch Dance below for more details).

Other notes: The contour of this song would be great to talk about and show with visuals. The initial leap of the fifth is also easy to isolate and talk about high and low.

#4 Someone Standing

Visit link for notation.

Source/Link: Caldwell Organized Chaos (check out the linked article for more high and low tips)

Game Directions:

- Students stand in a single circle with an “it” person in the middle.

- During the song, students walk to the right around the circle and sing.

- At the end, they face the middle and the person in the middle sings or plays a high and low pattern.

- The class echoes the person’s pattern by singing.

- The “it” person chooses a new it and the game repeats.

You could also have a few people in the middle, and they take turns giving a pattern. This saves time.

Other notes: On top of the game which can be used to show and practice high and low, you also have a good chance to show the contour of the song and its broad low-high-low line.

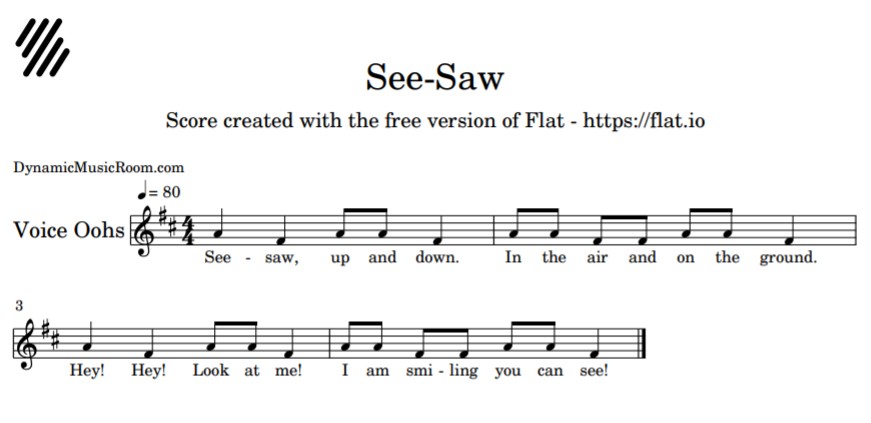

#5 See-Saw Up And Down

Source/Link: American Folk Song Collection

Game Directions: The game for this song revolves around creating different and more complicated seesaw (high/low) moves with partners.

Other notes: This song only has two pitches which can be great for reinforcing high and low. It can also be used to prepare sol-mi in older grades.

4 Ways To Teach High And Low In Kindergarten

Using these songs is great fun for Kindergarten kids, but there are some ways to teach specifically about the highs and lows in the song.

Here are 4 of my favorite activities to teach high and low in Kindergarten.

Note: Look for the button at the end of this section to download FREE resources for high and low I use in my room.

Pitch Dance

In pitch dance, you need some sort of pitched instrument to play with clear high and low selections available on the instrument (guitar or ukulele may not work well).

I prefer to use a piano.

Students should dance either up high or down low matching what the piano (or another instrument) is playing.

When the music stops, the students should freeze.

They should do this whole activity without talking.

Naturally, the teacher is improvising on the instrument and varying high and low.

At first, you may want to use an extreme difference in pitch. Then, you may gradually reduce the intervals.

Pro-tip: Expand the fun of the game by asking students to lead their dance moves with specific body parts.

For example, they now have to move high and low with their knees first.

You may even want to ask the students for body part ideas (just watch out for the obviously inappropriate ones!).

Watch The Leader

For this one, you need pictures representing high and low such as the image below.

Students sing on a general syllable (“doo,” “loo,” or “bum” work well) following the images as you point to them. (Check out this list of vocal warmups for kids to get better singing going.)

Then, you pick another student to come up and point to the pictures. The class has to try to follow them singing high and low.

Letting everyone get a turn will make everyone feel like a leader, and the game aspect of the activity will keep them interested without realizing they’re practicing a musical concept.

Arrange Your Own Song

Using star images on the board or cut out in small groups, students may arrange their own high and low song.

Don’t stress about words, although if they know a nursery rhyme or chant, they may want to apply the high and low to these words.

I enjoy having students make up these songs in small groups and then take turns playing on a xylophone in the general pitch level.

Pro-tip: Remove the F and B bars to avoid all half steps for a guaranteed good sound. This is the magic of the 5 notes of the pentatonic scale.

Draw What You Hear

This activity also works really well as an assessment tool.

Give the students a piece of paper and a couple of markers.

Have them listen to a melody line you play and draw the high/low contour of the line.

You may find it helpful to model this activity first and ask these questions as you do it:

- Does this start low or high?

- Does it go one direction or change in the middle?

- How many times does it change direction?

- How high or low did this music go?

Pro-tip: Don’t change too much or too often. Make it seem really obvious at first.

After a while and when they get the hang of it, you may want to really challenge them with difficult ones.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed these 5 high and low songs for Kindergarten.

Combined with some above learning activities, your students will leave Kindergarten with a strong grasp of pitch and be ready for expanding their knowledge in First grade.

I love including classical music wherever I can, but sometimes it’s time-consuming to create a bunch of resources.

When I discovered Maestro Classics, I knew I had to share it with others. The resources are affordable and engaging for all students.

(It’s even great for cross-curricular teaching).

This simple guide will answer what is a pitch in music, provide examples, and explain how to identify pitches in music.

What Is Pitch In Music?

Pitch is a term used to describe how high or low sounds are. Vibrations produce all sounds, and when those vibrations are heard at consistent frequencies, the listener perceives them as musical tones. Sounds that don’t have a precise musical tone to them are referred to as having indefinite pitch.

This post covers:

- What is Pitch in Music

- What is An Example of Pitch In Music

- How Do You Identify a Pitch in Music

- Why is Pitch Important in Music

- What Are the 12 Pitches in Music

- Tone vs. Pitch

- Pitch vs. Frequency

- What is the Highest Pitch in Music

In simple words, pitch in music means how high or low a specific note will sound to the listener’s ear. It is one of the most fundamental terms in music.

When a note is played on an instrument, it generates a sound wave. That sound wave is nothing but the vibration of air molecules that go back and forth, thus creating a wave of pressure that travels from the instrument to the listener’s ears.

Now one of the fundamental properties of a sound wave is its frequency.

By definition, the total number of waves produced in one second is called the frequency of that wave. In simple words, it can be said that the frequency is how fast the cycle of the wave is.

It is important to discuss so much about frequency because pitch and frequency are quite related to each other.

- High Frequency = High Pitch

- Low Frequency = Low Pitch

So pitch basically means how the human ear hears and understands the frequency.

Pitch is the quality that allows us to judge ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ in the sense of musical melodies.

Remember that pitch is each person’s subjective perception of a sound wave. So it can’t be measured directly. But it doesn’t mean that most people agree which note is high or which note is low.

Actually, the oscillations of a sound wave can be characterized in terms of frequency. Generally, the pitch is associated with and thus quantified in terms of frequency.

So the high pitch means very rapid oscillation sare occurring, while a low pitch is related to the slower oscillation.

What is An Example of Pitch In Music?

To learn more about the tone, it is also essential to have a basic understanding of the tone. A tone is a sound that is sung and played at a specific pitch.

Different ranges of tones are produced by different voices and different instruments.

For example, women generally tend to have higher voices than men.

So tones that most women sing are generally higher-pitched compared to the tones most men sing. (Of course, there can be an exception where a man has a high pitched voice)

It is also essential to consider that the physically larger instruments generally tend to produce lower-pitched tones. But on the other hand, the smaller instruments generally tend to produce higher-pitched tones.

This is because the bigger instruments move more air than the smaller instruments, and more air means a lower musical pitch.

This is because only a small cylindrical flute produces higher-pitched sounds than the big brass tubing of a tuba.

Also, some instruments, such as the piano, produce a broad range of tones compared to other instruments.

How Do You Identify a Pitch in Music?

Since the pitch is how high or how low a specific note sounds to your ears, you need to listen to the note carefully. Pitch is based on the frequency of vibrations of the sound wave. So If the sound wave vibrations are faster, you are going to get a higher pitch.

If the vibrations are slower, then it’s going to sound lower, and thus you can identify it as the lower pitch sound.

Tool: Pitch Detector – This tool allows you to quickly determine the pitch of any sound or note.

Why is Pitch Important in Music?

Pitch is important in music because it enables us to judge whether a sound is higher or lower in a sense associated with musical melodies.

What Are the 12 Pitches in Music?

As per the pitch naming scheme, each pitch is named based on the seven characters in the English Alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, G.

To better understand the types of pitches, let’s consider the case of the piano. The white keys on a piano are assigned these letters.

The pitch named A produces the lowest frequency of sound, while the pitch named G produces the highest frequency of sound.

There are also the black keys in between the white keys on the piano.

Each black key produces a frequency a little bit higher than the white key on their immediate left, but they produce a little lower frequency compared to the white key on their immediate right.

White key on immediate left < Black key < White key on the immediate right

Based on this fact, black keys are also named sharps or flats.

So actually, there are 7 (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) + 5 (flats and equivalent sharps in between) = 12 notes that produce the 12 different types of pitches.

What’s the Difference Between Tone & Pitch?

| Tone: | Pitch: |

| It refers to the quality of sound produced. | It refers to how high or low a sound is produced. |

| It depends on the strength, intensity, and pitch, and quality of the music | It depends on the frequency of a voice or instrument |

| It helps in determining the quality of the sound and overall music | It helps in determining the shrillness or frequency of the sound |

What is the Difference Between Pitch & Frequency?

| Pitch | Frequency |

| It tells us about the frequency of the sound. | It tells us how fast the cycle of sound waves is. |

| A pitch can’t be measured since it’s a sensation of the frequency of a sound. | The frequency of sound can be measured. |

What is the Highest Pitch in Music?

Considering the case of a piano, the pitch named “G” is the highest.

A high pitch means the sound wave has a higher frequency of vibration. In a standard musical staff, the higher pitch notes are represented on the treble clef.

If the pitch is quite high, then it will be several ledger lines above the treble clef staff. In a piano or a keyboard, the high pitch notes are found on the right-hand side and are usually played using the right hand.

Whereas on the stringed musical instruments, they are played high on the fingerboard.

Summary of Pitch

Pitch refers to how high or low a note sounds when it is played or sung. Pitch can also refer to how high or low someone sounds when they speak. For musical instruments, the word “pitch” means the frequency at which it vibrates. When an instrument is tuned to a certain pitch, it will sound when plucked or when blown.

We hope you found this information on pitch in music helpful.

If we missed anything, please share it in the comments.

Join us as we dive into the depths of the different music symbols and their meanings.

When it comes to reading sheet music, there are hundreds of symbols that you need to learn before you can even think of playing off of it. All the different symbols used for various musical instruments also make it even more challenging.

That’s why we have committed a few days of our time to put together all the musical symbols you need to learn in one place.

In this article, you’ll learn musical symbols ranging from lines, clefs, rhythmic symbols, key signatures, and everything in between.

Let’s dive right in.

In This Article

- Lines

- Clef

- Symbols for the Rhythmic Values of Notes and Rests

- Breaks

- Accidentals

- Key Signatures

- Microtones

- Time Signatures

- Note Relationship

- Dynamics

- Articulation Mark

- Ornaments

- Octave Signs

- Repetition and Codas

- Instrument-Based Symbols

- Conclusion

Lines

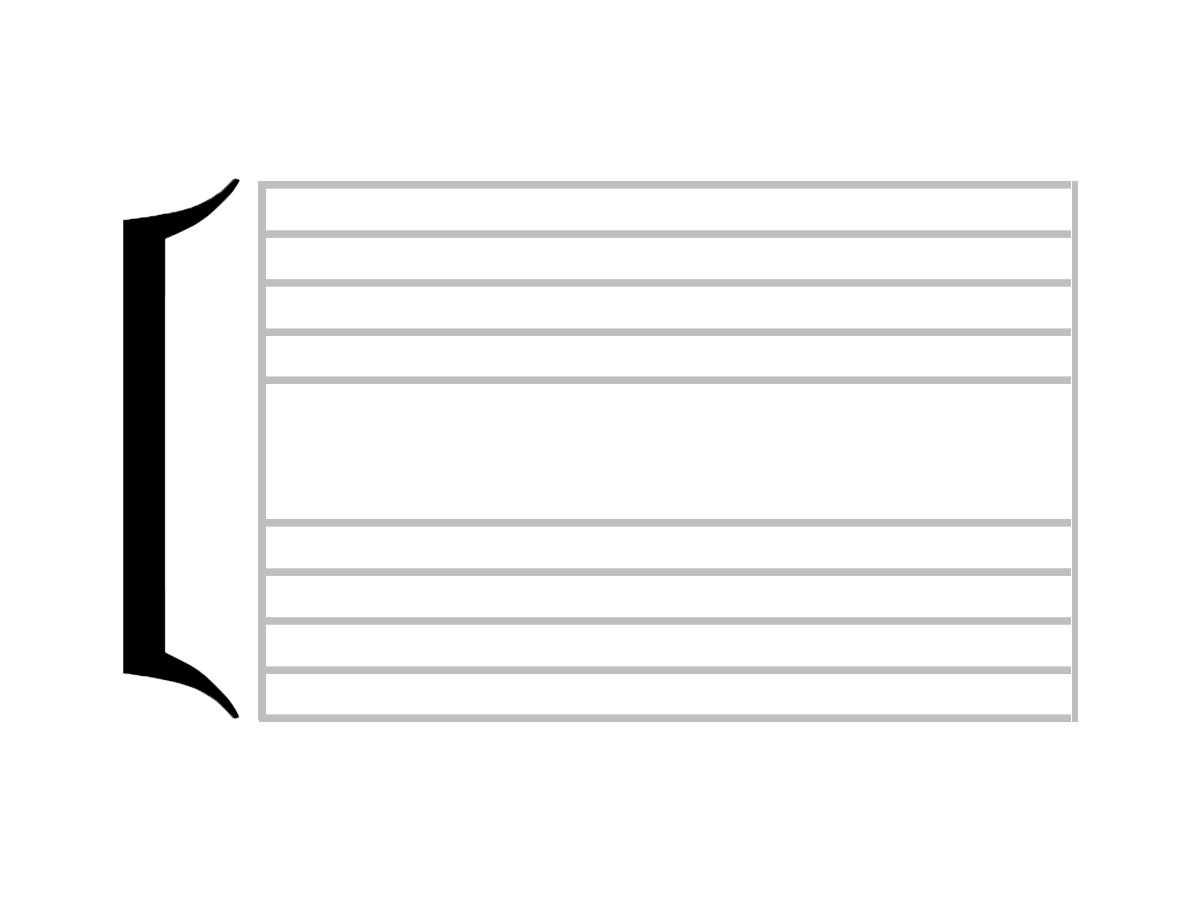

Lines symbols in musical notation often relate to the non-notation markings to help composers write and organize the clefs, notes, and other symbols involved in a piece. These lines help the performers read the sheet music better and understand where they are in the piece.

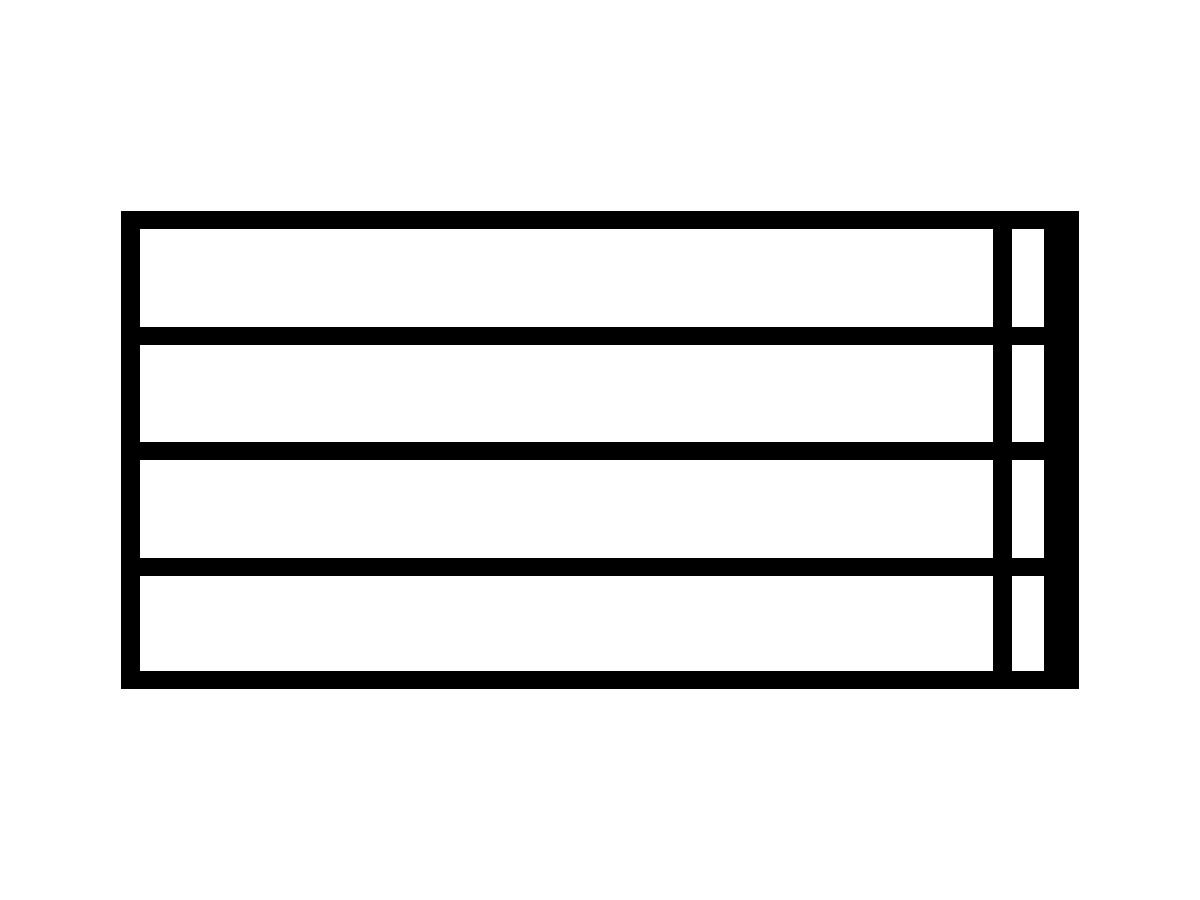

- Staff or stave

- Ledger or leger lines

- Barline

- Bracket

- Brace of accolade

Staff or stave

The staff (American) or stave (British) are five horizontal lines that indicate a different musical pitch or different percussion instruments. Each line and space refer to either specific notes or percussion instruments.

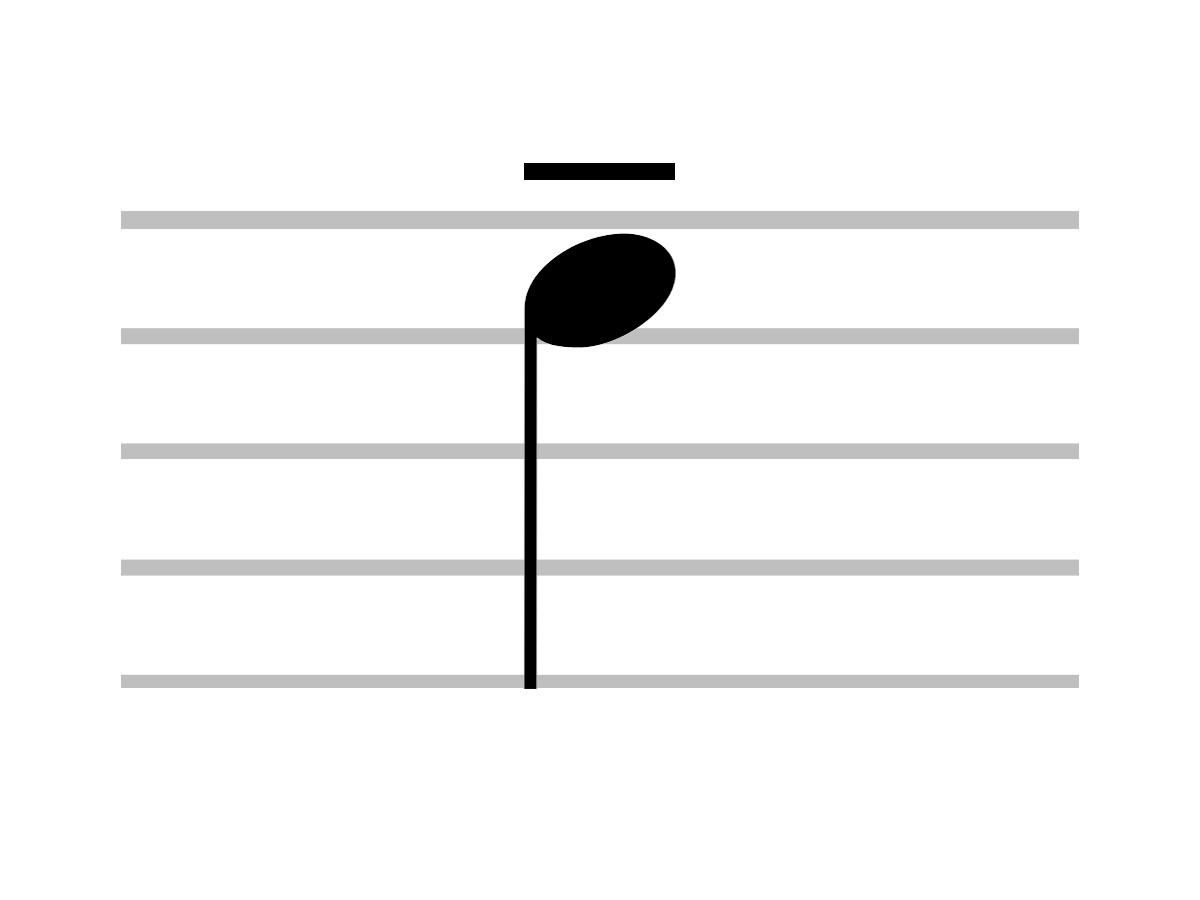

Ledger or leger lines

The ledger lines notate higher or lower pitches outside the lines and spaces of the regular musical staff. Lines above indicate a higher pitch, while lines below lower indicate a lower pitch.

Barline

Barlines separate musical bars according to the time signature of the piece. This helps musicians keep track of where they are in the sheet music.

There are several different types of barlines: double barline, bold double barline, and dotted barline.

Double barline

A double barline usually appears at the end of a section to tell the performers of the upcoming changes in the pitch, tone, or pace. Pop songs usually have a double barline between the verse and the chorus.

Bold double barline

A bold double barline marks the end of the piece. It looks like a regular double barline but with a thicker second line.

Dotted barline

A dotted barline is the modified version of a regular barline. It divides long bars into shorter segments to help performers read the sheet music.

Bracket

Brackets connect two or more lines of music that need to be played simultaneously. A bracket usually connects staves of individual instruments (e.g., flute and clarinet) or multiple vocals in modern music.

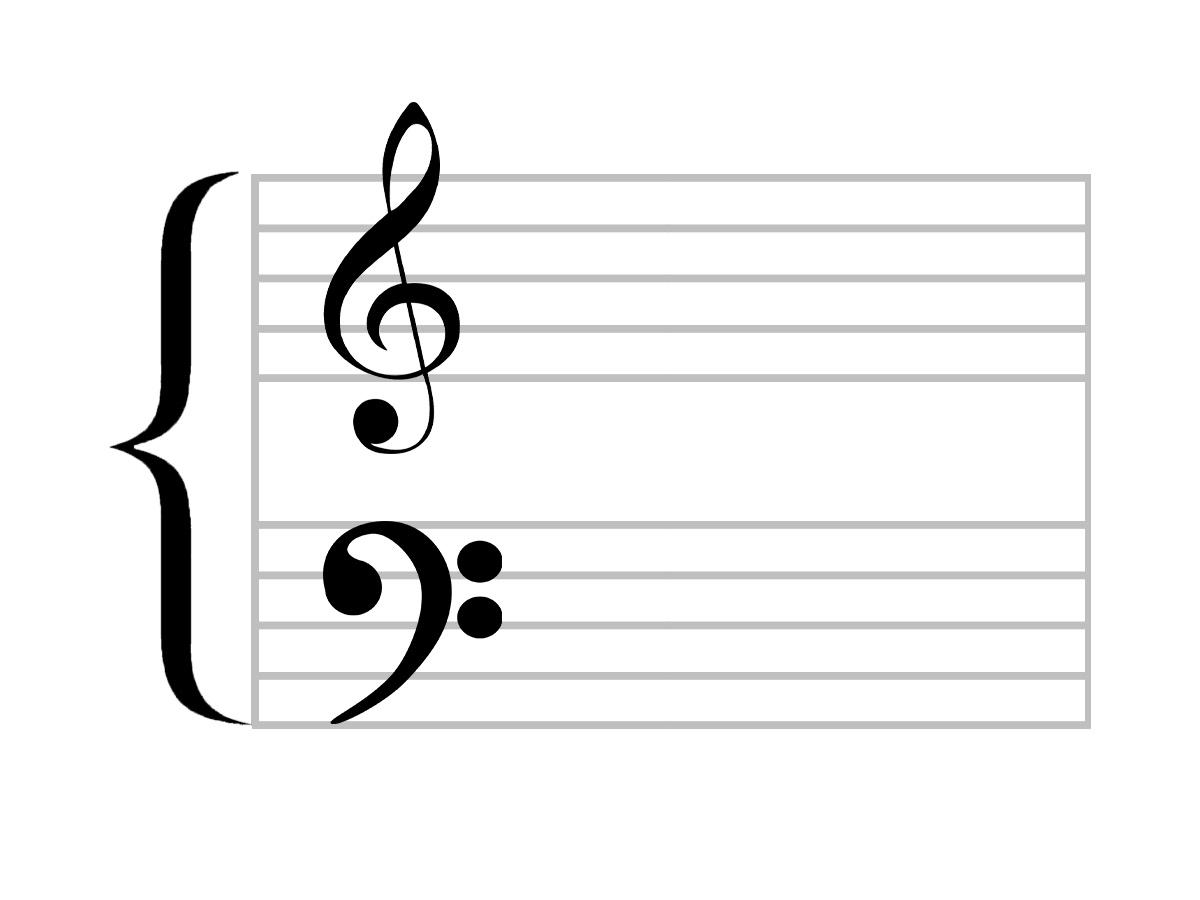

Brace or accolade

A brace connects two or more lines of music that need to be played simultaneously by a single player when using a grand staff. Braces usually connect staves for piano, celesta, harp, organ, and some pitched instruments.

Clef

A clef is a musical symbol that indicates which notes are represented by the lines and spaces on a musical staff.

These symbols often appear at the beginning of the section in a musical staff. Clef can be placed on any line or space on the musical staff, but modern notations usually only use treble, bass, alto, or tenor clef.

- G clef or treble clef

- C clef or alto and tenor clef

- F clef or bass clef

- Octave clef

- Neutral clef

- Tablature

G clef or treble clef

The spiral bit of the G clef points to where the G (or sol) is located on the staff. When the spiral is located on the second line of the staff, it’s called a treble clef.

Treble clef is the most common clef used in modern music – even more common than the alto and tenor clef.

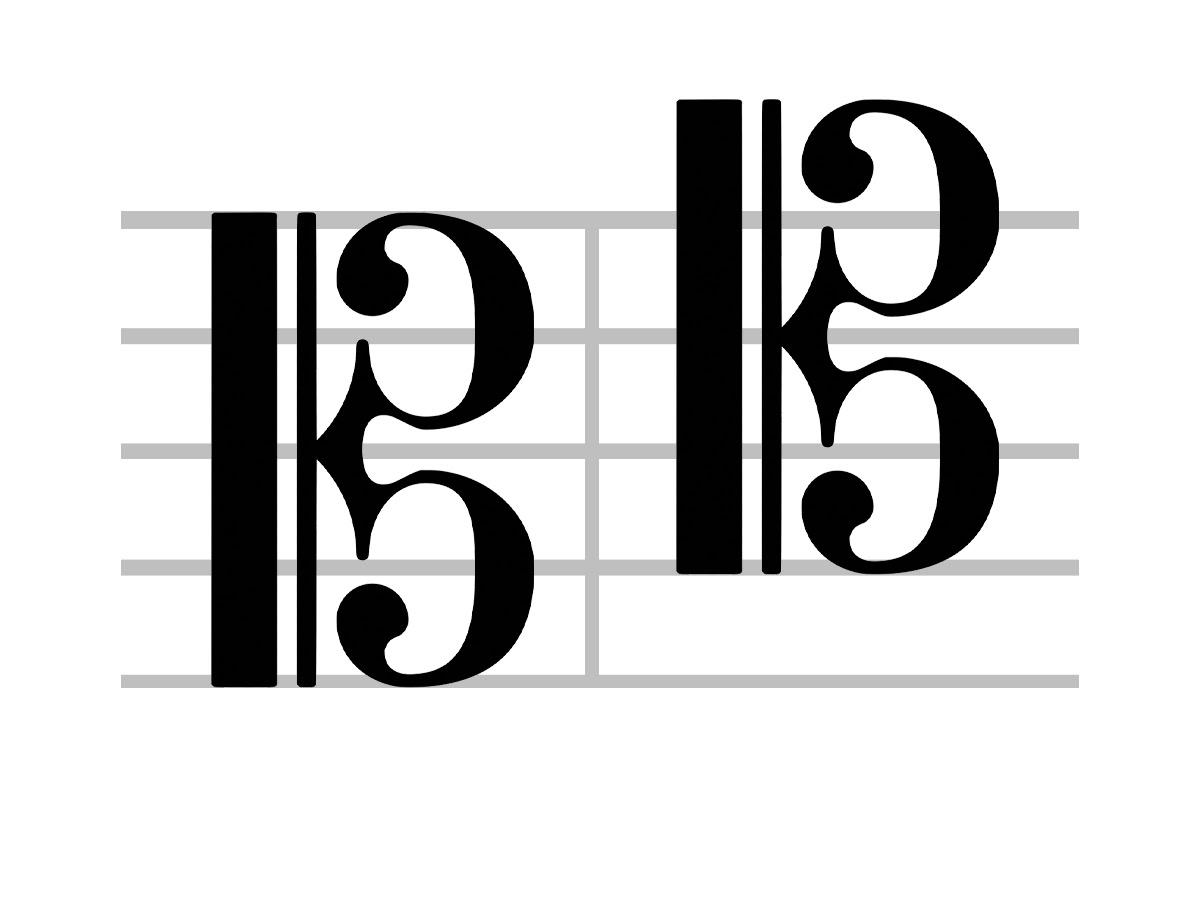

C clef or alto and tenor clef

The center part of a C clef marks the line representing middle C/do. If the center part points to the third line, it becomes an alto clef, which is common in viola. If the center point is at the fourth line on the staff, it becomes a tenor clef, which is mainly used for bass, cello, trombone, and double bass.

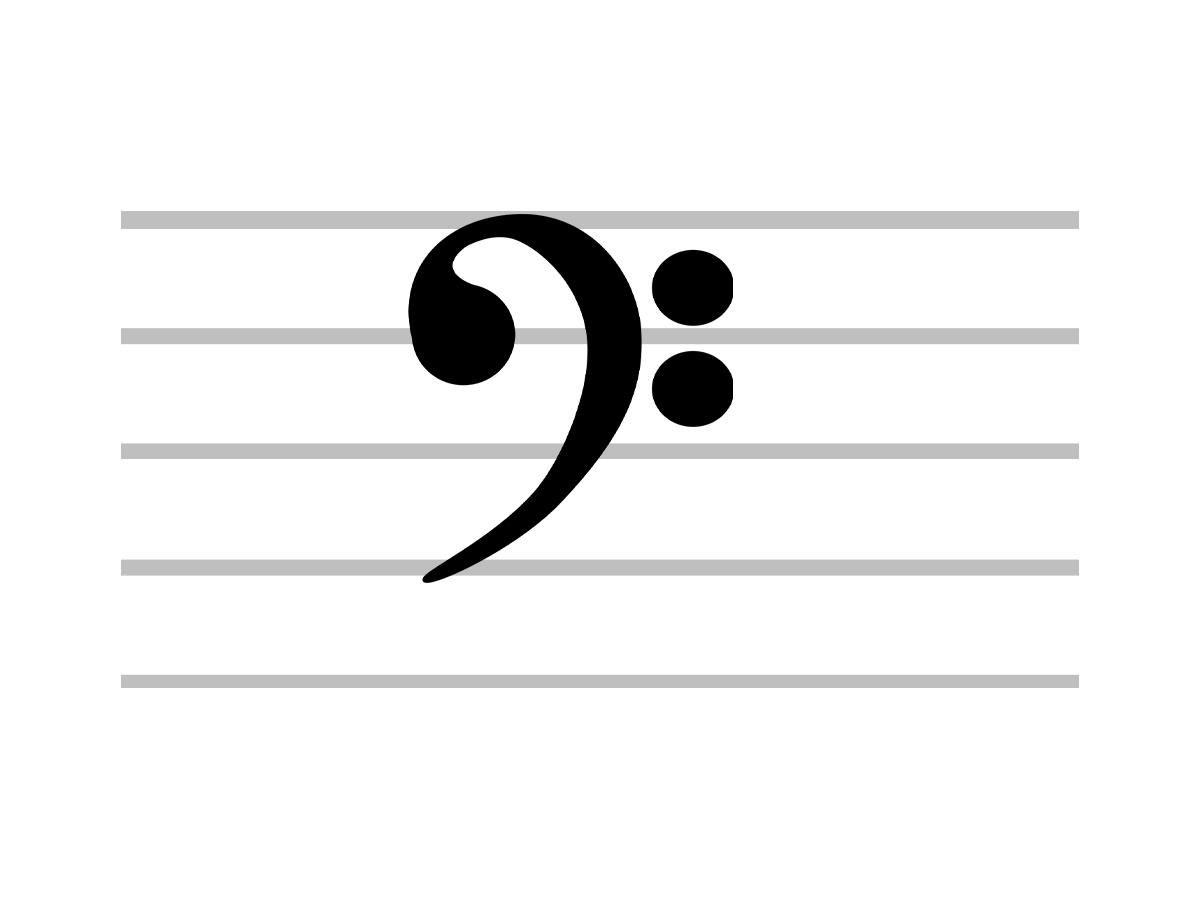

F clef or bass clef

An F clef marks the line that represents the F/fa note in between the two dots. When the F is placed on the fourth line, the symbol is called a bass clef.

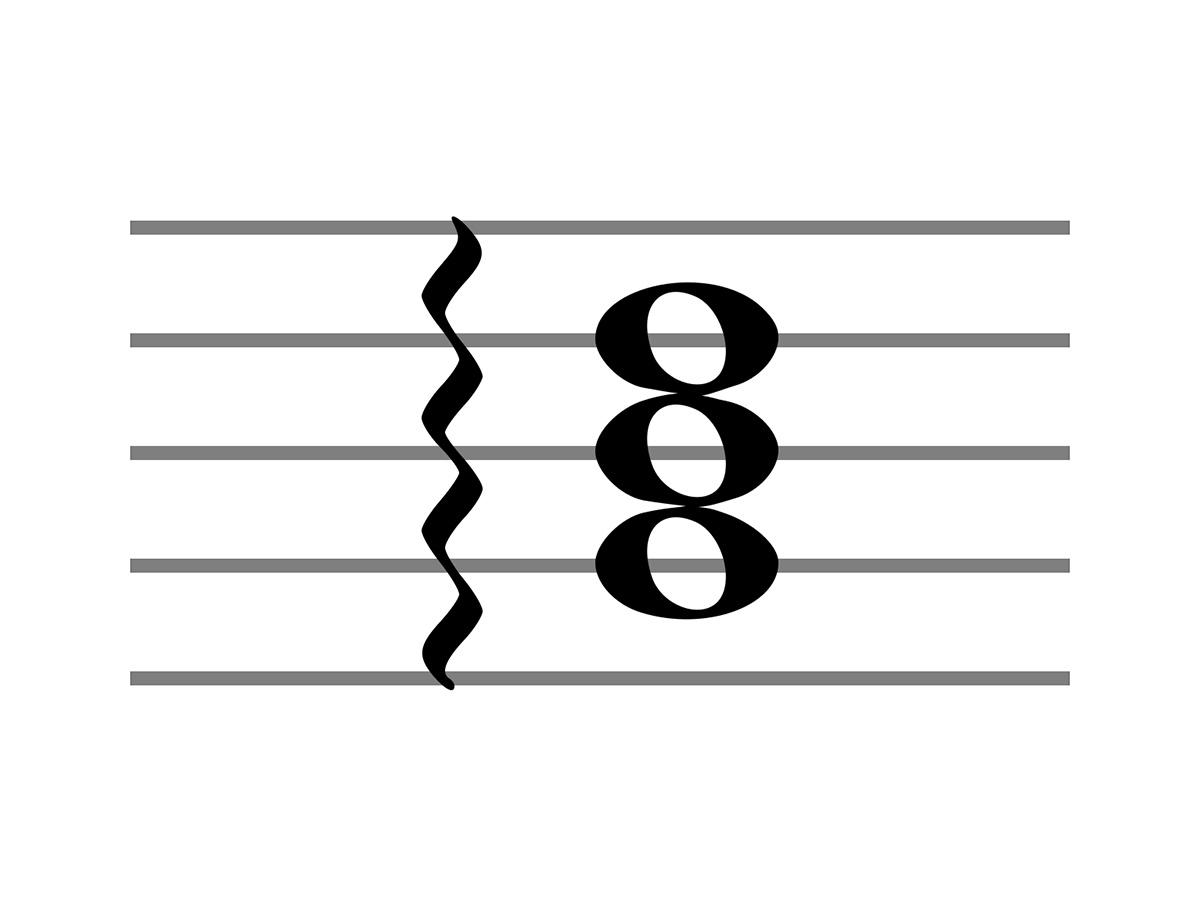

Octave clef

An octave clef modifies the treble and bass clef to indicate whether the pitch sounds higher or lower than natural. An “8” means one octave, and a “15” means two octaves.

In the example above, the note is an octave lower than natural since the “8” is placed below the staff. If it was placed above the musical staff lines, it means that the note is an octave higher than natural.

Neutral clef

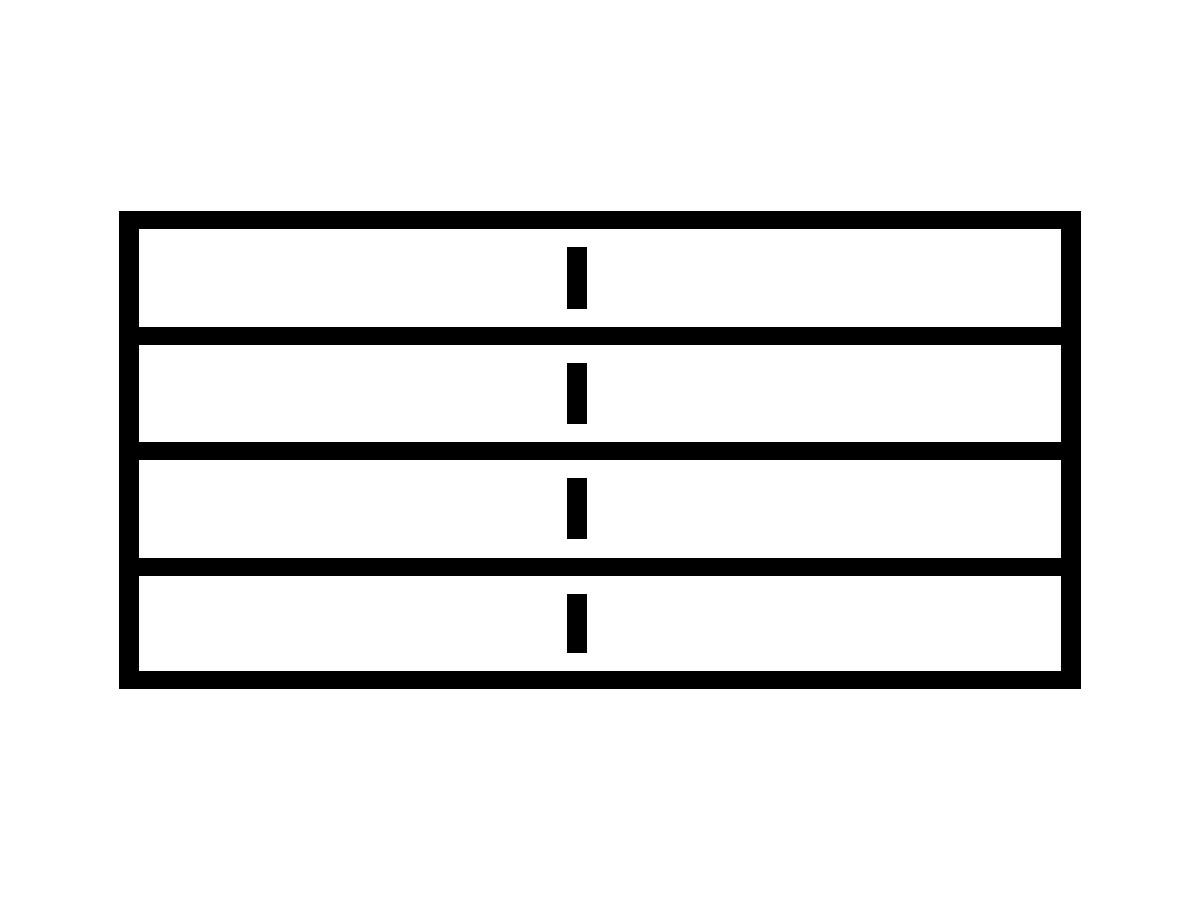

Neutral clef often appears in pitchless instruments like the drums. The lines here indicate specific instruments, such as the different drums in a drum set.

The neutral and tablature are not true clefs since they do not indicate pitches.

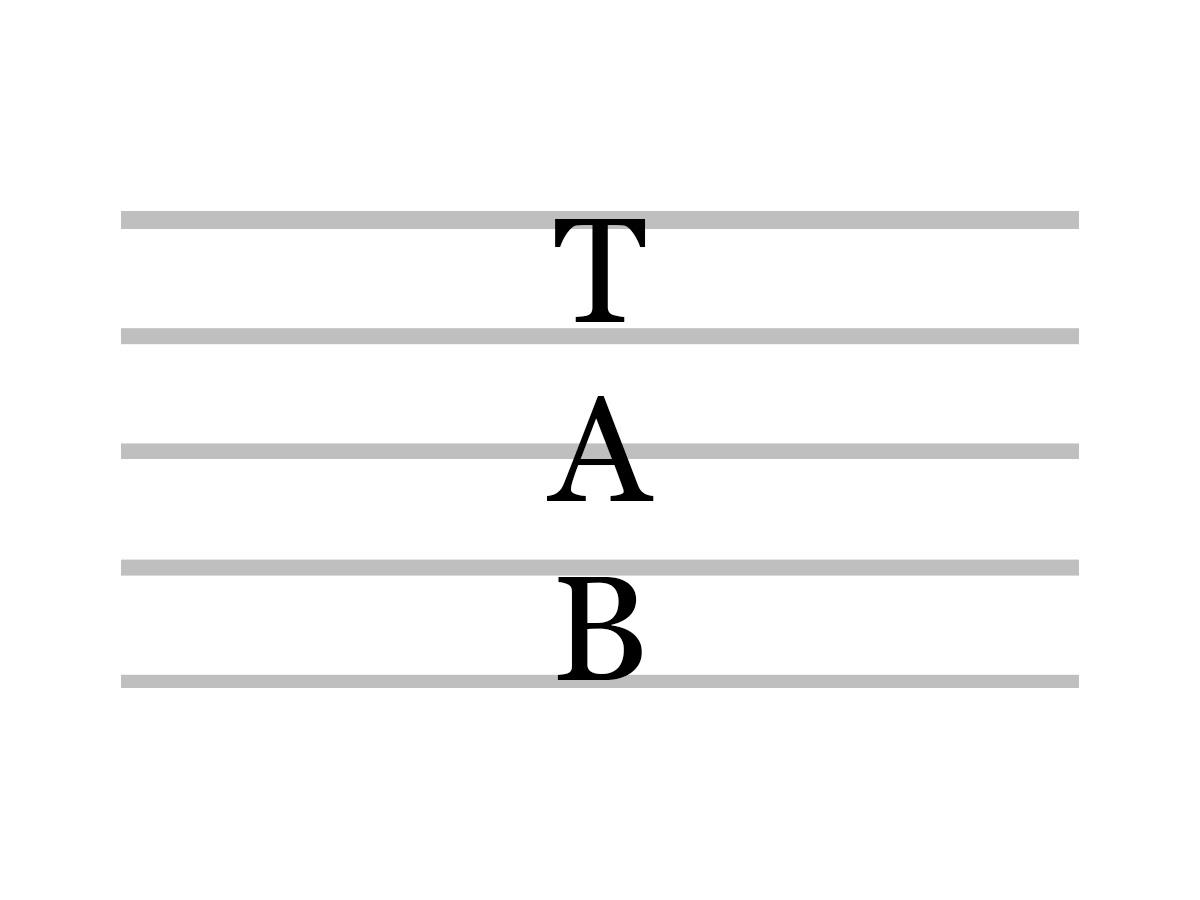

Tablature

The tablature doesn’t represent pitches in any way, but it replaces regular staff for string instruments like the guitar. The lines in a tablature represent the string of an instrument (e.g., a standard 6-string guitar would use a 6-line tablature).

Symbols for the Rhythmic Values of Notes and Rests

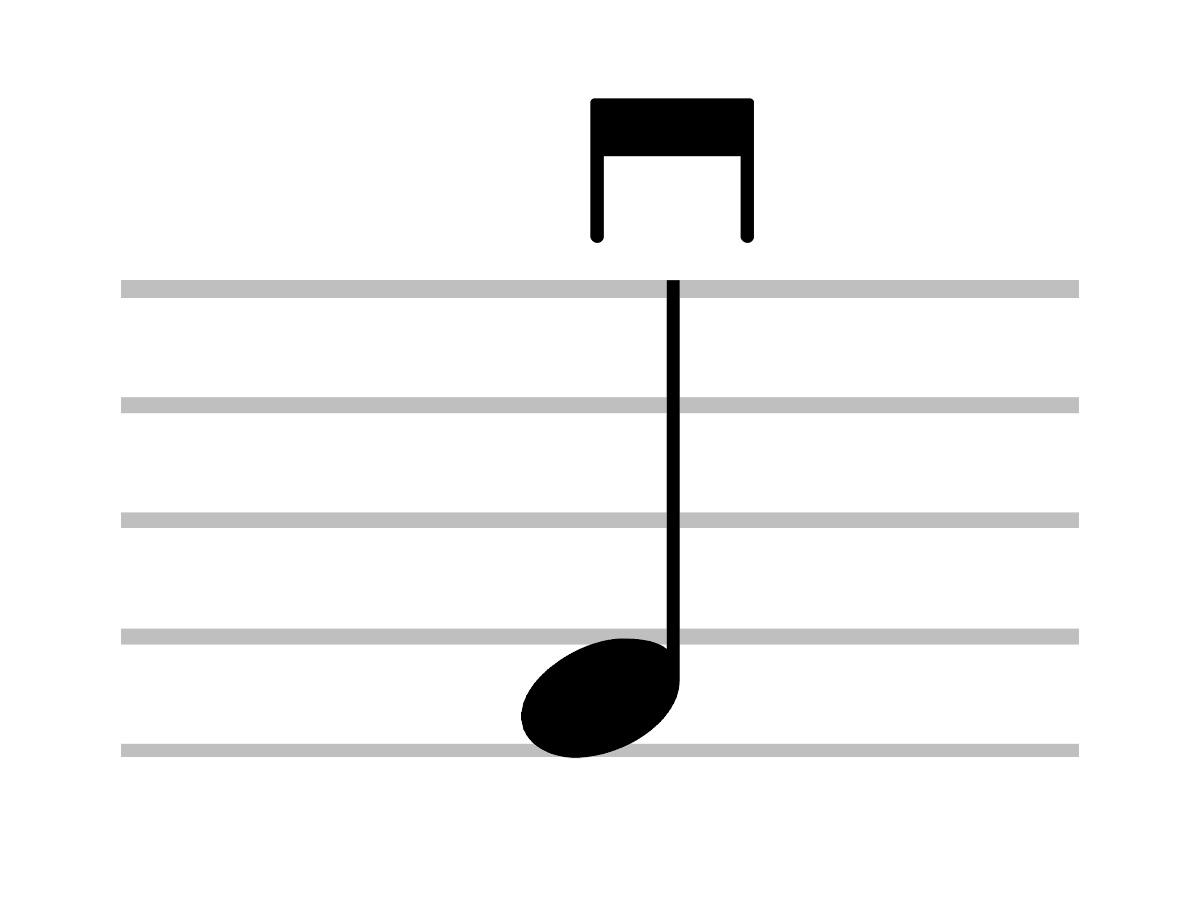

Musical notes indicate the relative duration of a note using the shape of a note head, note stem, and note flags. Rests indicate silence of the equivalent duration as the musical notes.

These symbols have two varieties: one for the musical note and another one for rests.

- Large or octuple whole note

- Long or quadruple whole note

- Breve or double whole note

- Semibreve or whole note

- Minim or half note

- Crotchet or quarter note

- Quaver or eight note

- Semiquaver or sixteenth note

- Demisemiquaver or thirty-second note

- Beamed notes

- Dotted notes

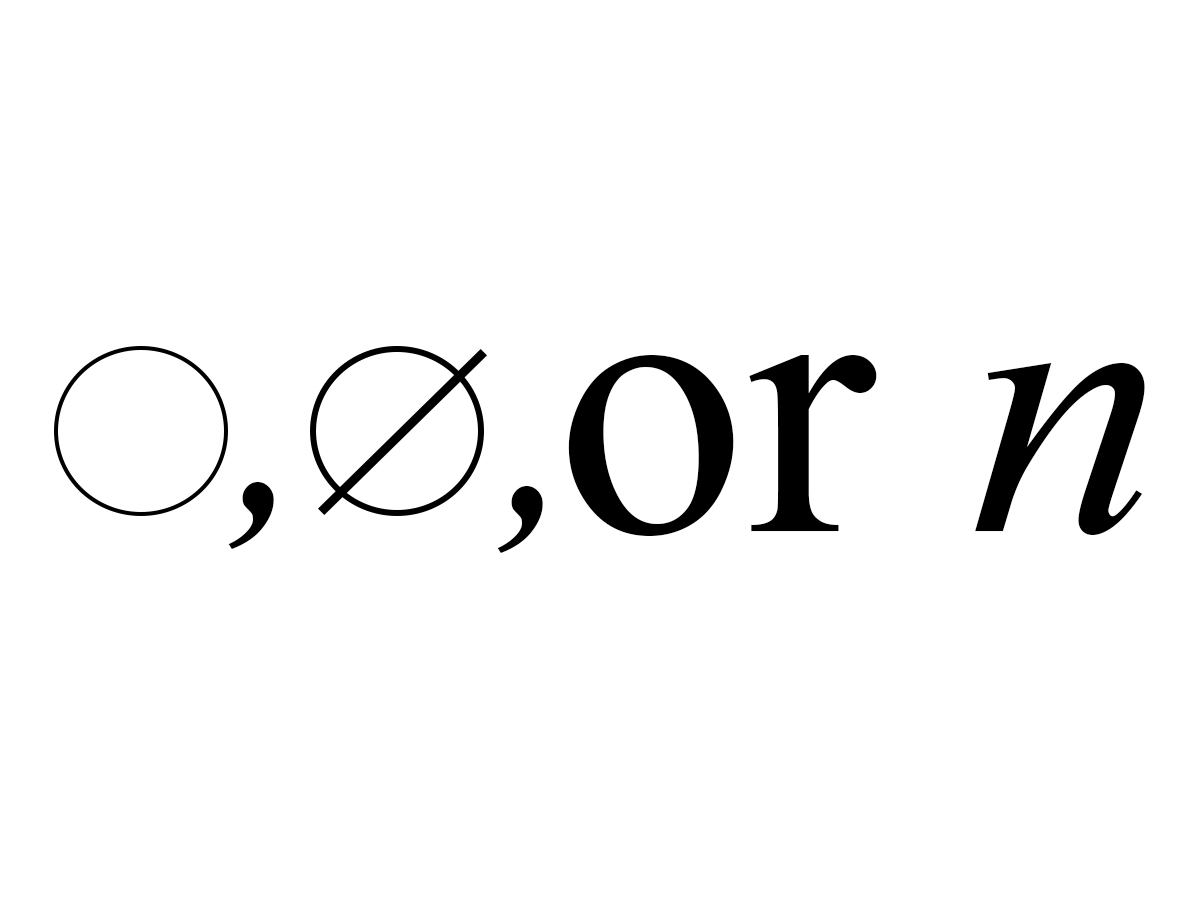

- Ghost notes

- Multi-measure rest

Large or octuple whole note

The octuple whole note or large (British) was a musical notation used in the 13th and 14th centuries. It was typically four, six, or nine times as long as a breve – but it’s no longer used in modern music.

Long or quadruple whole note

The quadruple whole note (or long, longa, or sometimes longe) is a note that could be either twice or three times as long as a breve.

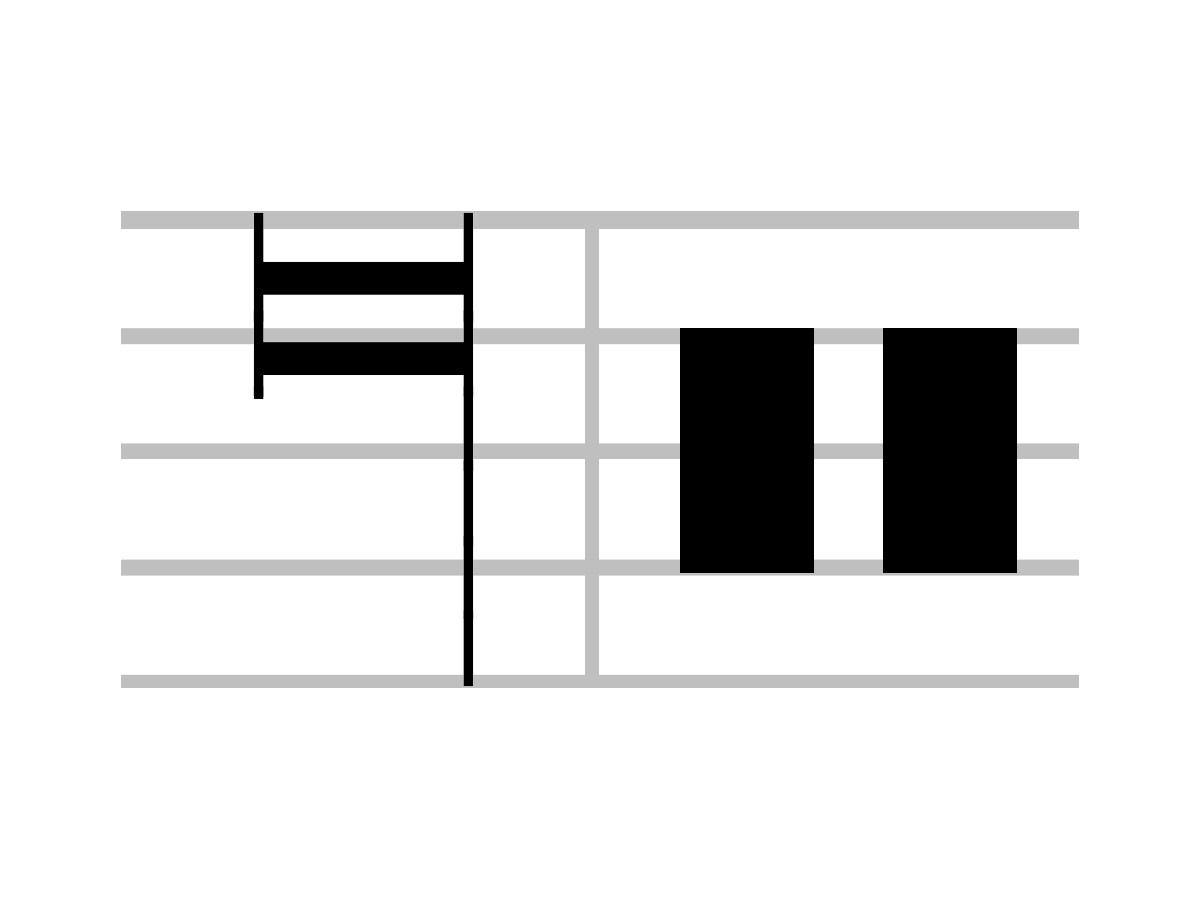

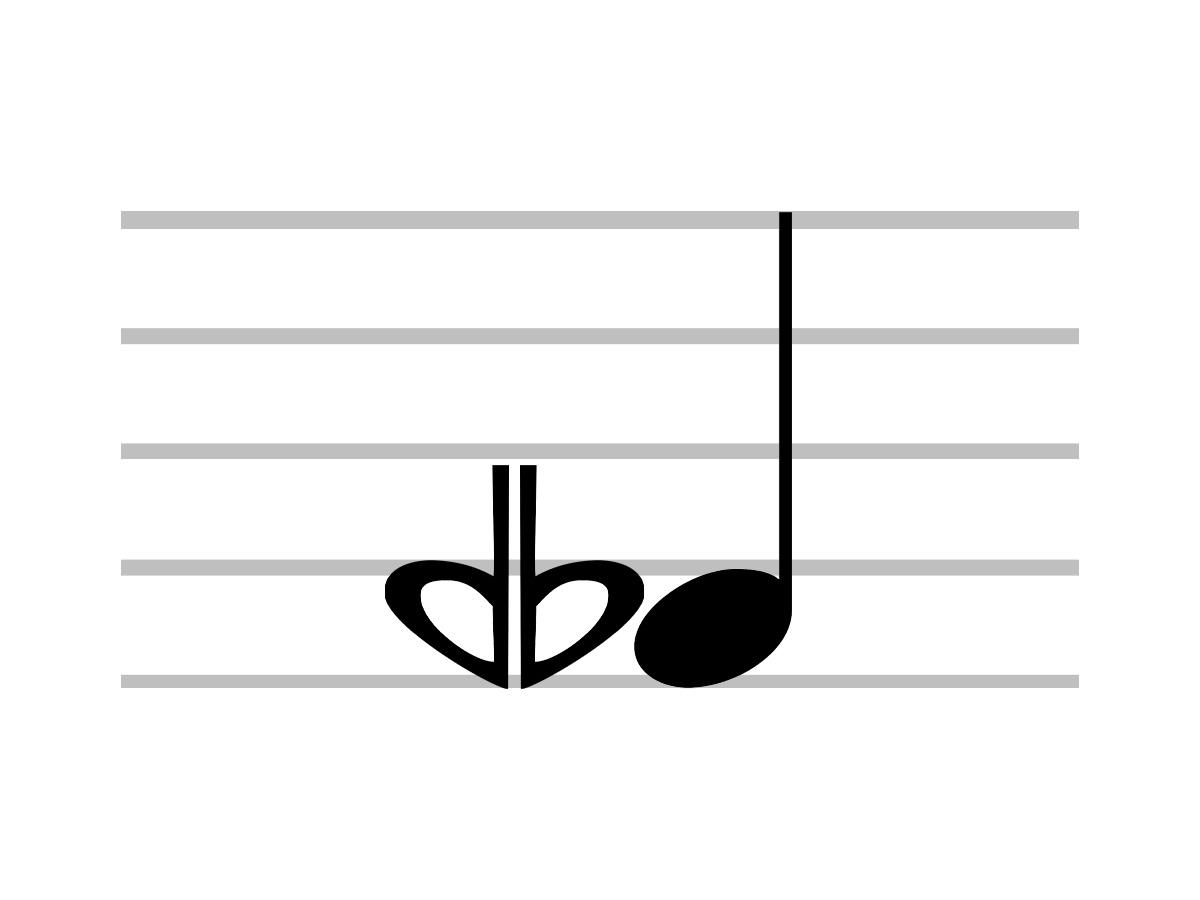

Breve or double whole note

The double whole note has twice the duration of a whole note and is the longest note in Western music notation – but it’s rarely used in modern music. It was widely used in music notation coming from the late renaissance era.

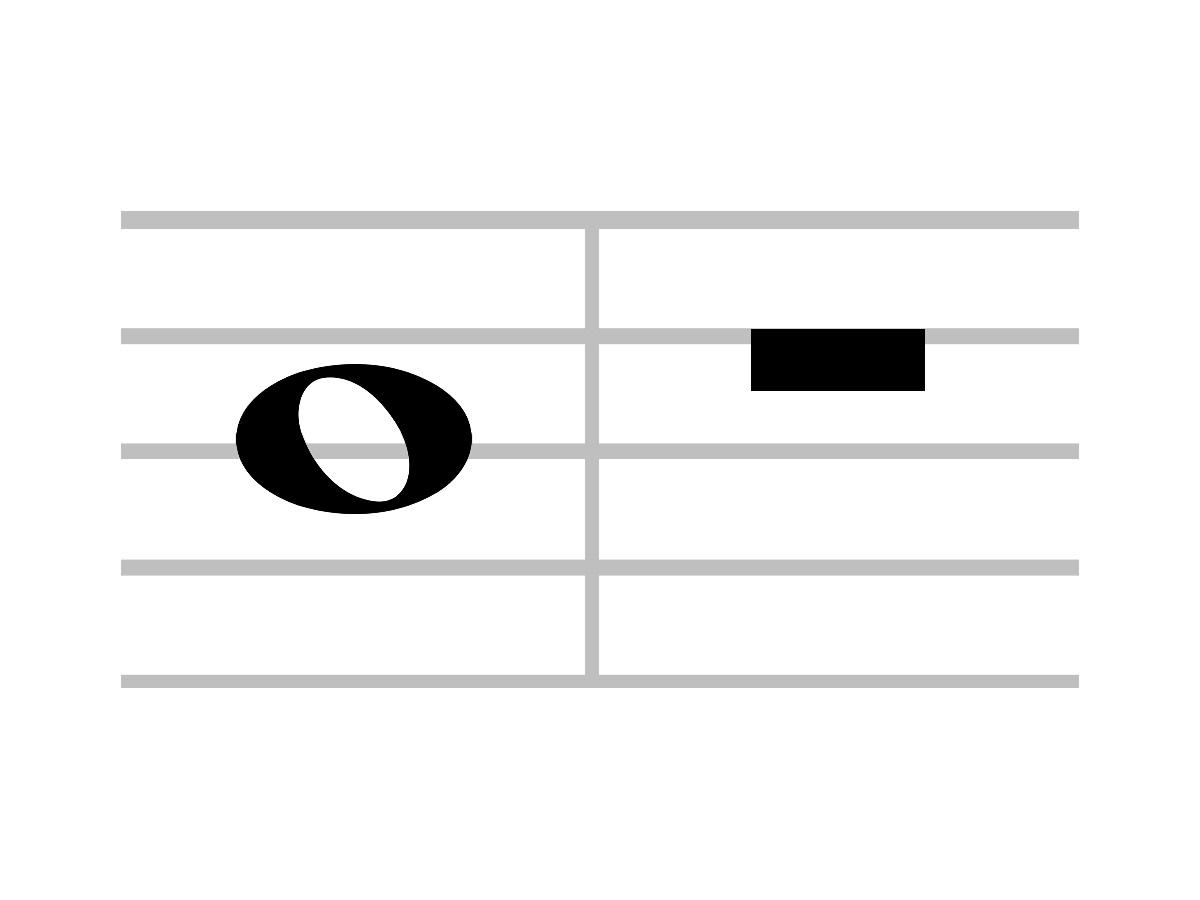

Semibreve or whole note

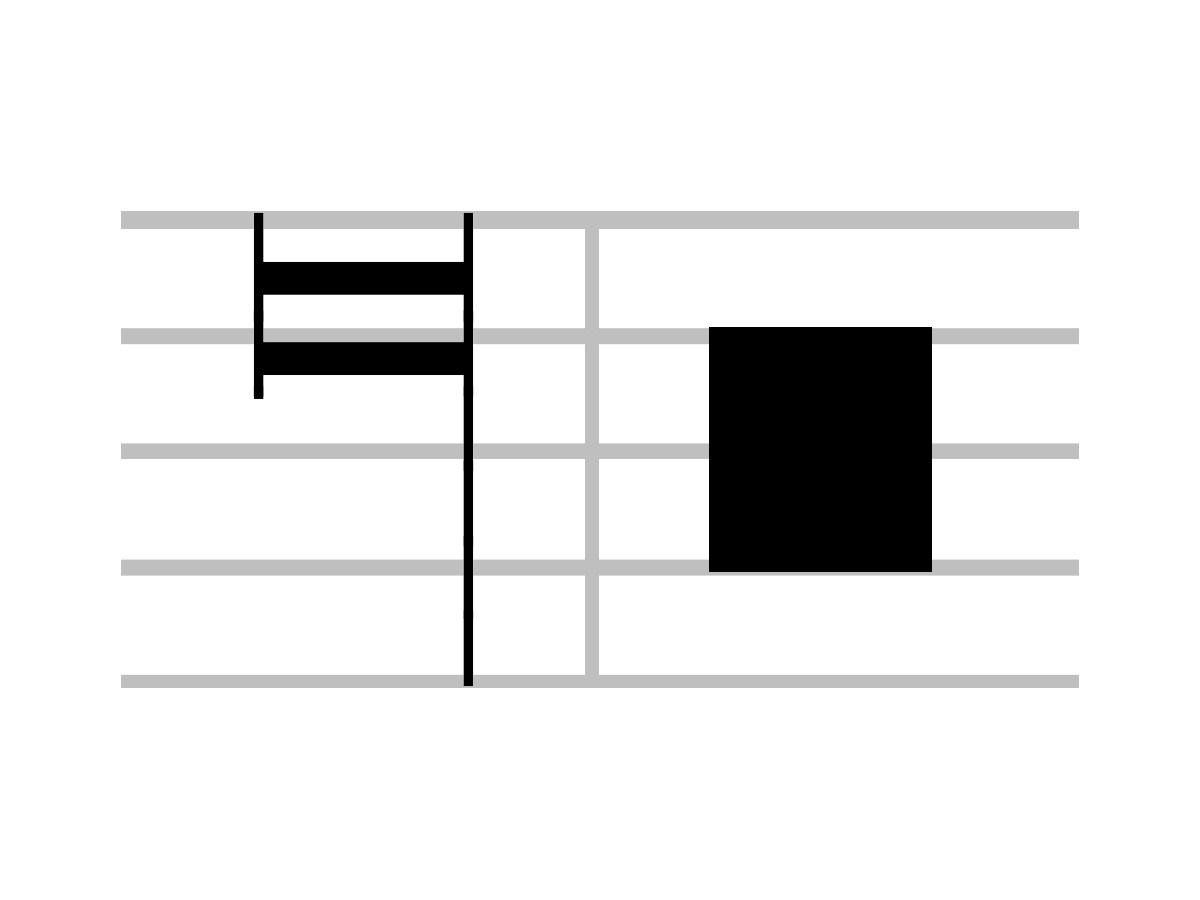

A whole note or a semibreve (British) is a musical notation that counts as four beats – and it looks like a hollow circle with no stem attached to it in a 4/4 piece.

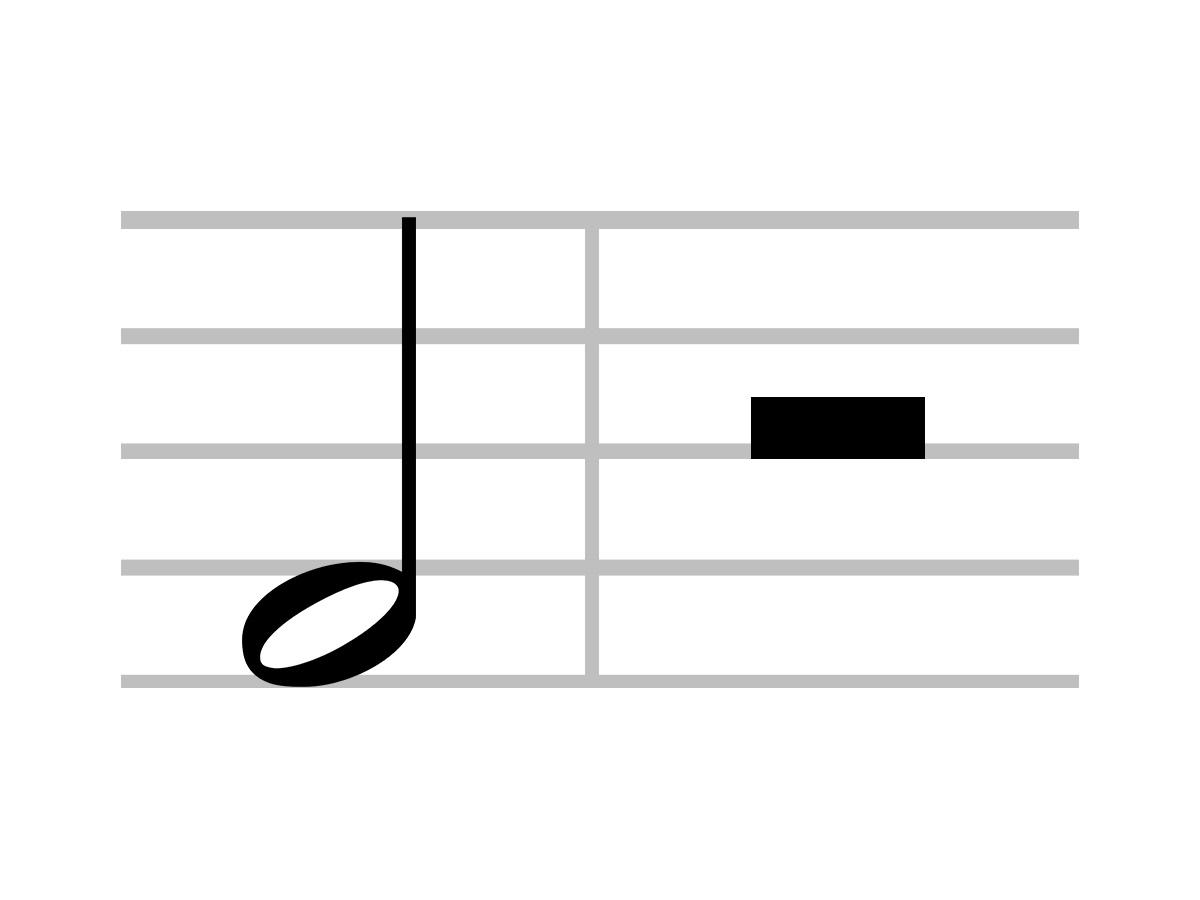

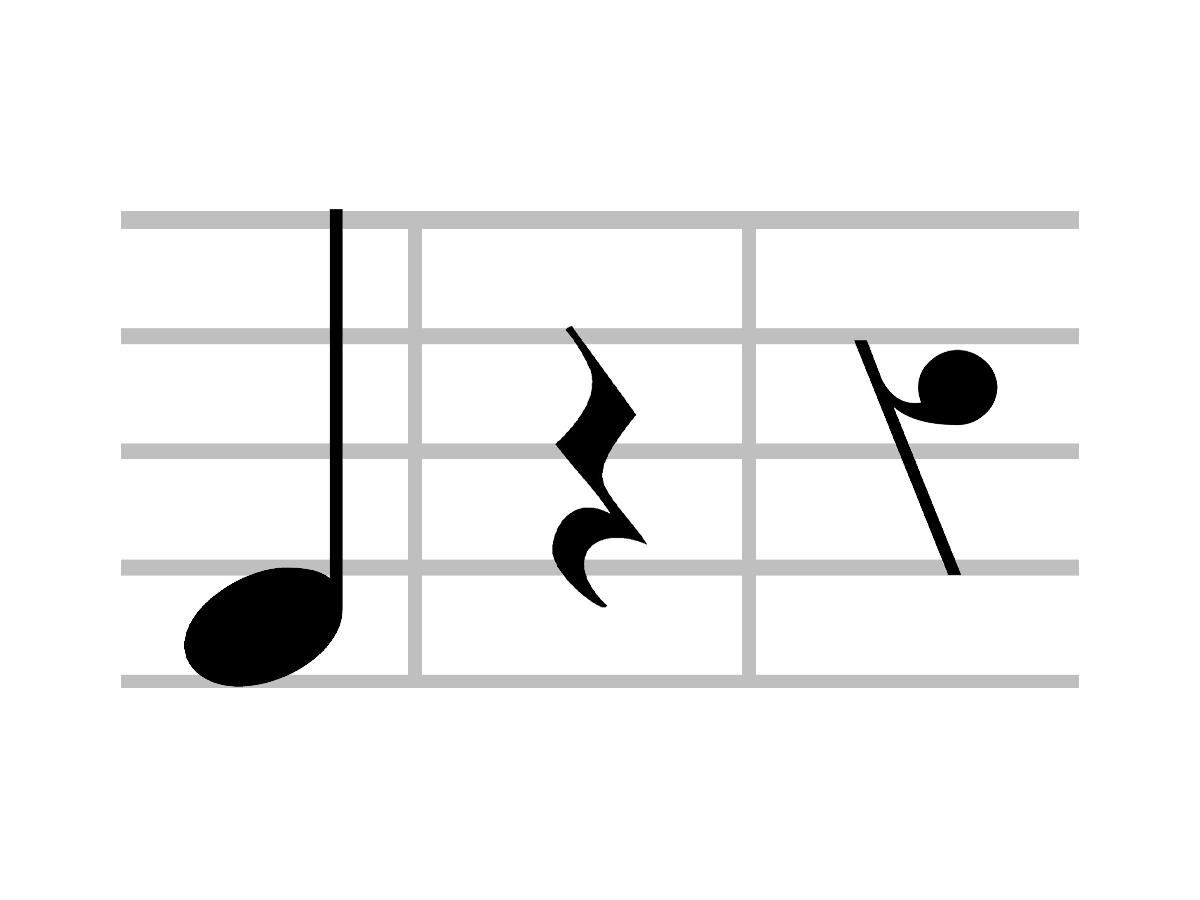

Minim or half note

A minim (British) or a half note (American) is half as long as a semibreve. It counts for two beats and is represented as a hollow note head with a stem attached to it.

Crotchet or quarter note

A crotchet (British) or a quarter note (American) is half as long as a minim or a quarter as long as a semibreve. It counts for one beat and is represented with a filled-in notehead with a stem attached to it.

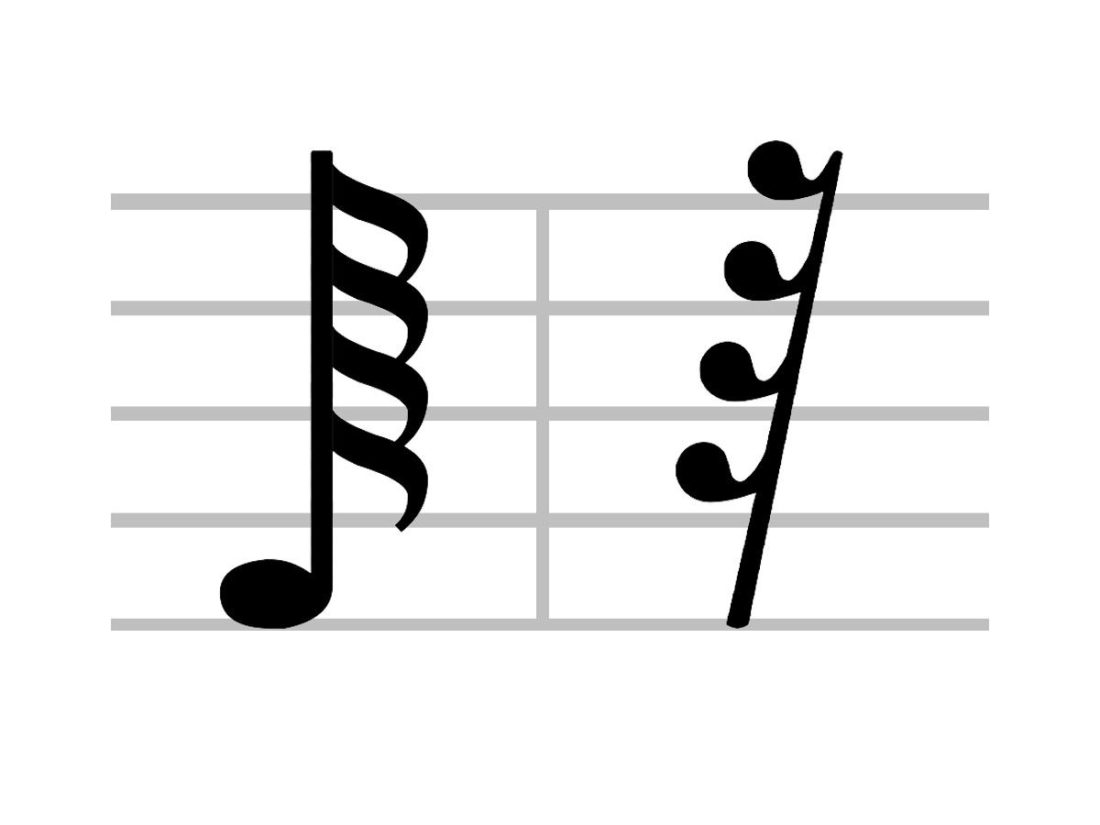

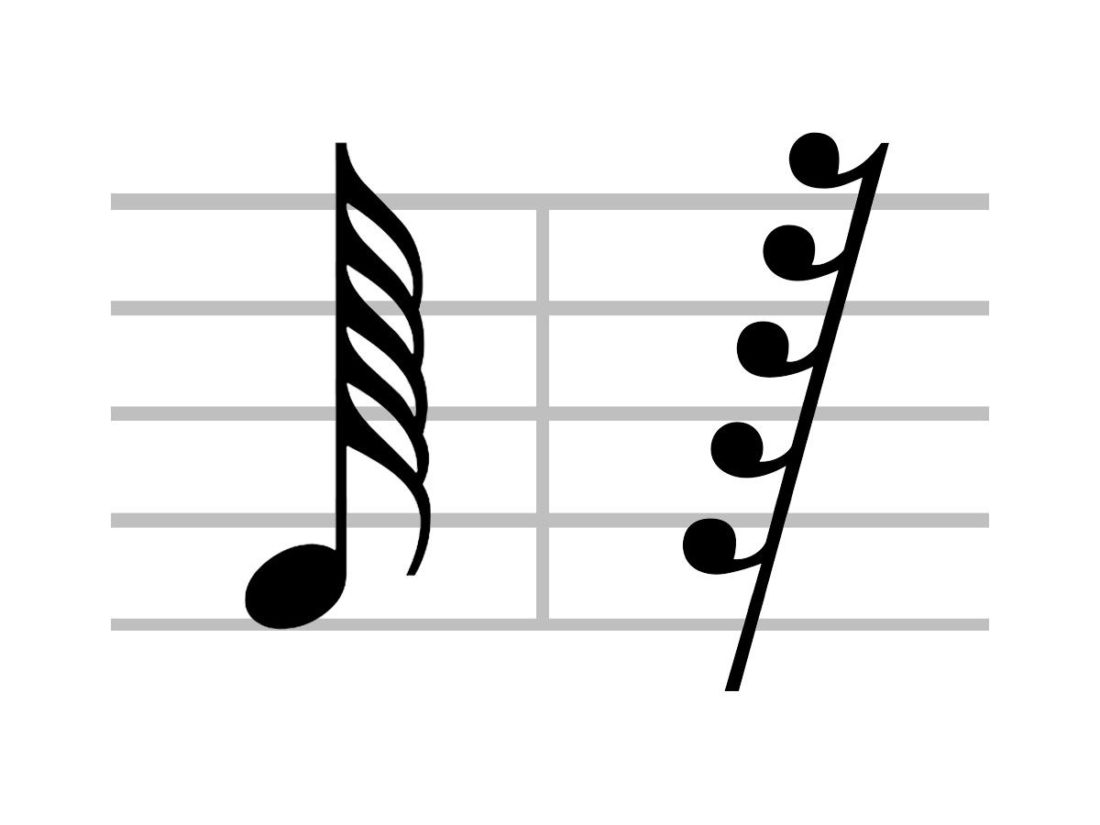

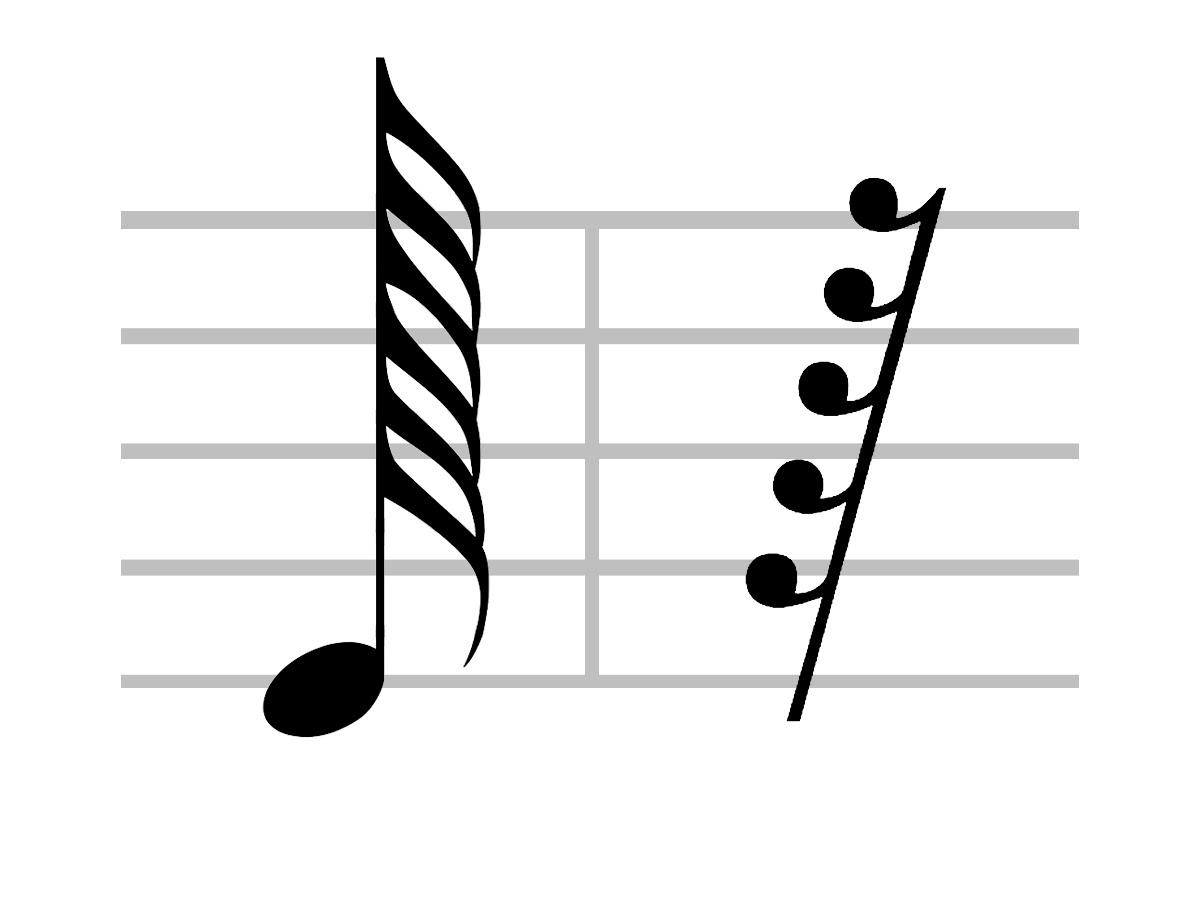

Eight note or shorter notes have an increasing number of note flags, starting from one flag (eighth note) to six flags (1/256th note).

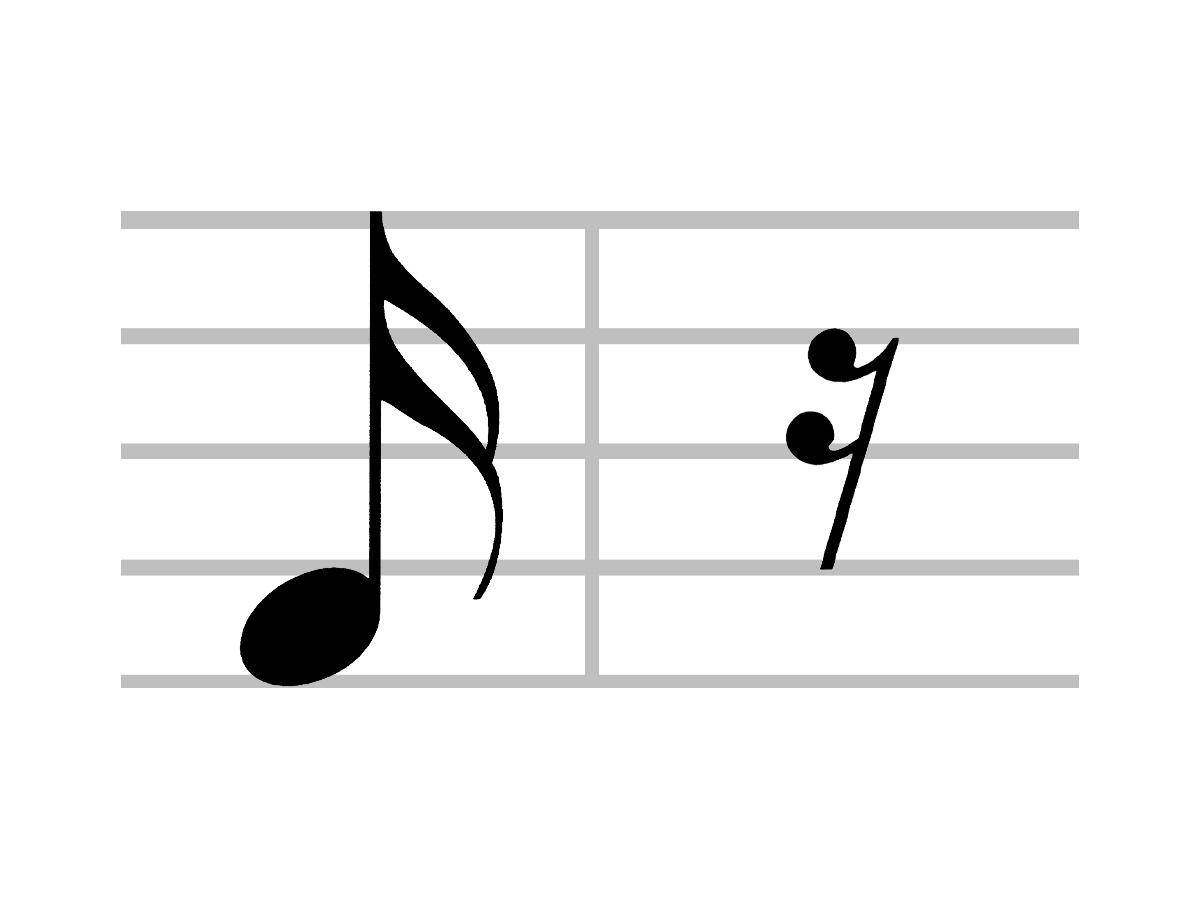

Quaver or eight note

A quaver (British) or an eight-note (American) is a musical notation that counts as one eight the duration of a whole note. One quaver counts for half a beat – two quavers complete one beat.

Semiquaver or sixteenth note

A sixteenth note (American) or a semiquaver (British) is a note that counts as half of the duration of an eighth note. One semiquaver counts for one quarter of a beat – four semiquavers complete one beat.

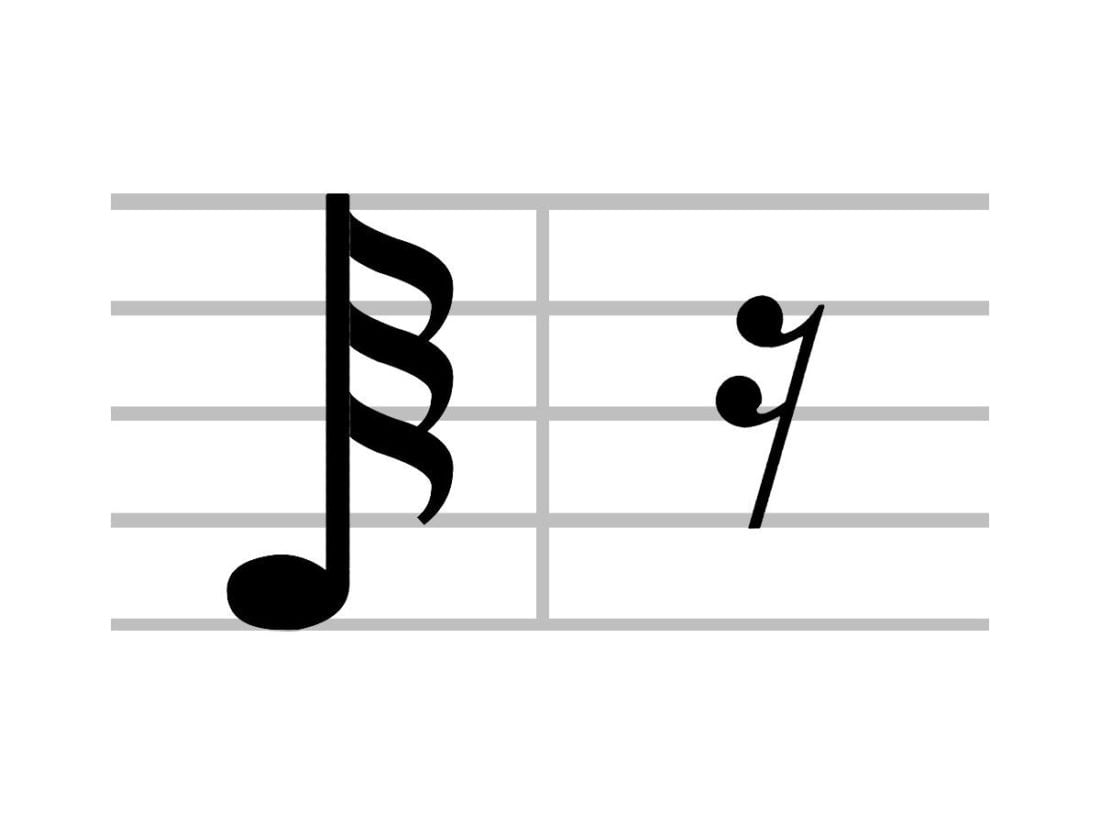

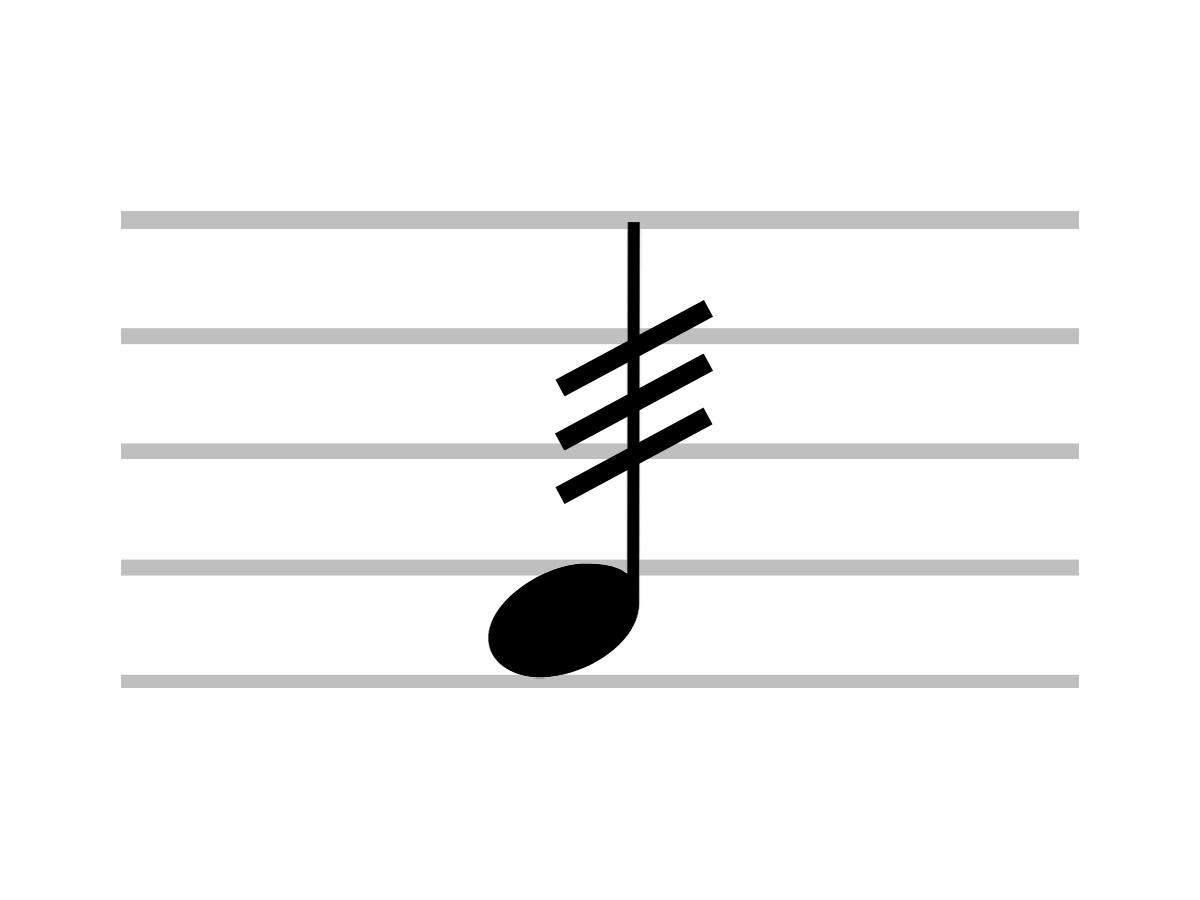

Demisemiquaver or thirty-second note

A thirty-second note or a demisemiquaver is a note that counts as 1/32 of the duration of a whole note. Eight demisemiquavers complete one beat.

Hemidemisemiquaver or sixty-fourth note

A sixty-fourth note is a musical notation that counts as 1/64 the duration of a whole note and half as long as the thirty-second note. Sixteen hemidemisemiquaver counts for one beat.

Semihemidemisemiquaver / quasihemidemisemiquaver / hundred and twenty-eighth note

As the name implies, the hundred and twenty-eighth note is a musical notation that plays for 1/128 duration of the whole note. A semihemidemisemiquaver counts for one 32nd of a beat.

Demisemihemidemisemiquaver / two hundred fifty-sixth note

The two hundred fifty-sixth note is a musical notation that plays for 1/256 of the duration of a whole note. This note counts for one sixty-fourth of a beat, which means 64 of these complete one beat.

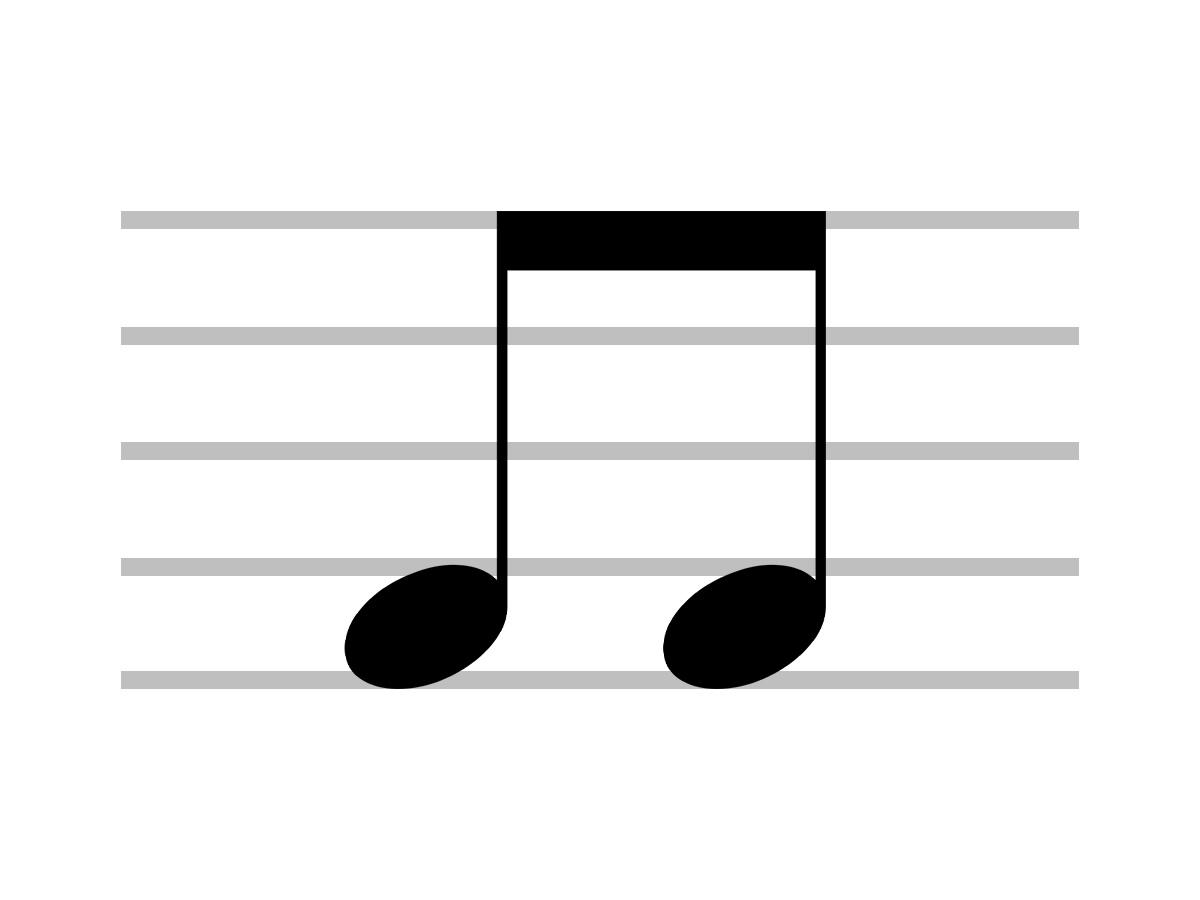

Beamed notes

A beam is a horizontal or diagonal line used to connect multiple notes that appear consecutively. Beamed notes indicate a rhythmic grouping and can only contain eight notes (quavers) or shorter notes.

In music theory, a rhythmic grouping is when two or more notes are joined together with a beam based on the time signature used in a piece.

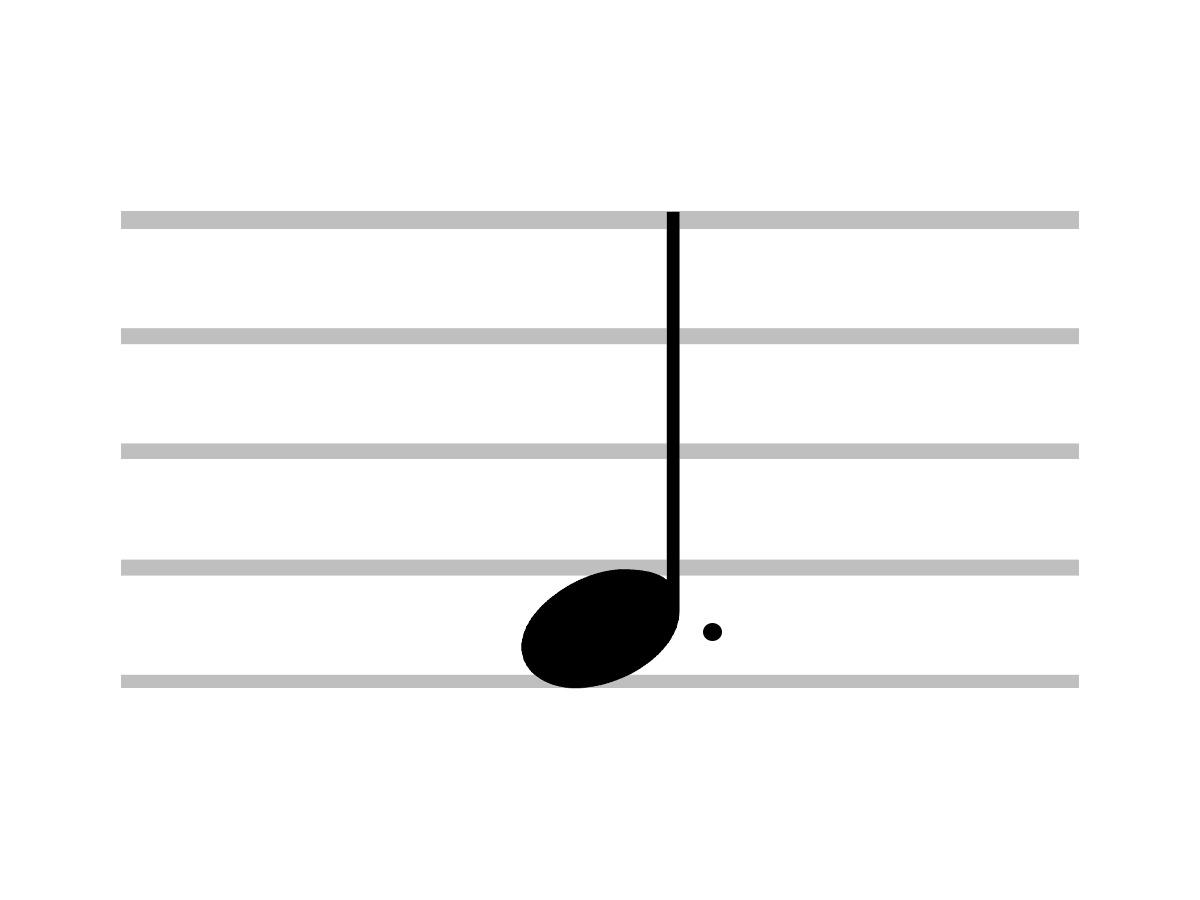

Dotted notes

A dotted note is a musical notation with a small dot placed right after it. The first dot increases the duration by half of its original length. The second dot extends the note’s duration by half of the duration of the first dot – and it goes on for the next subsequent dots.

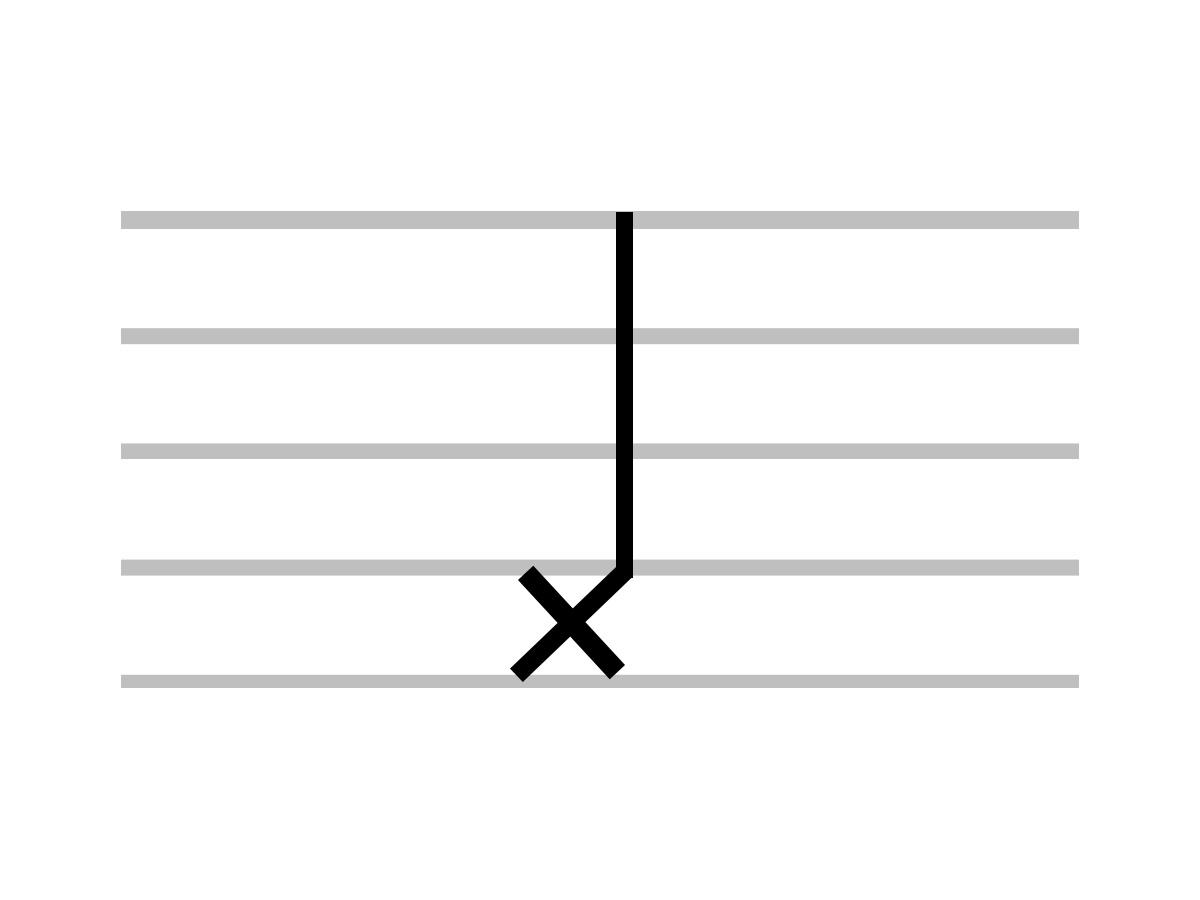

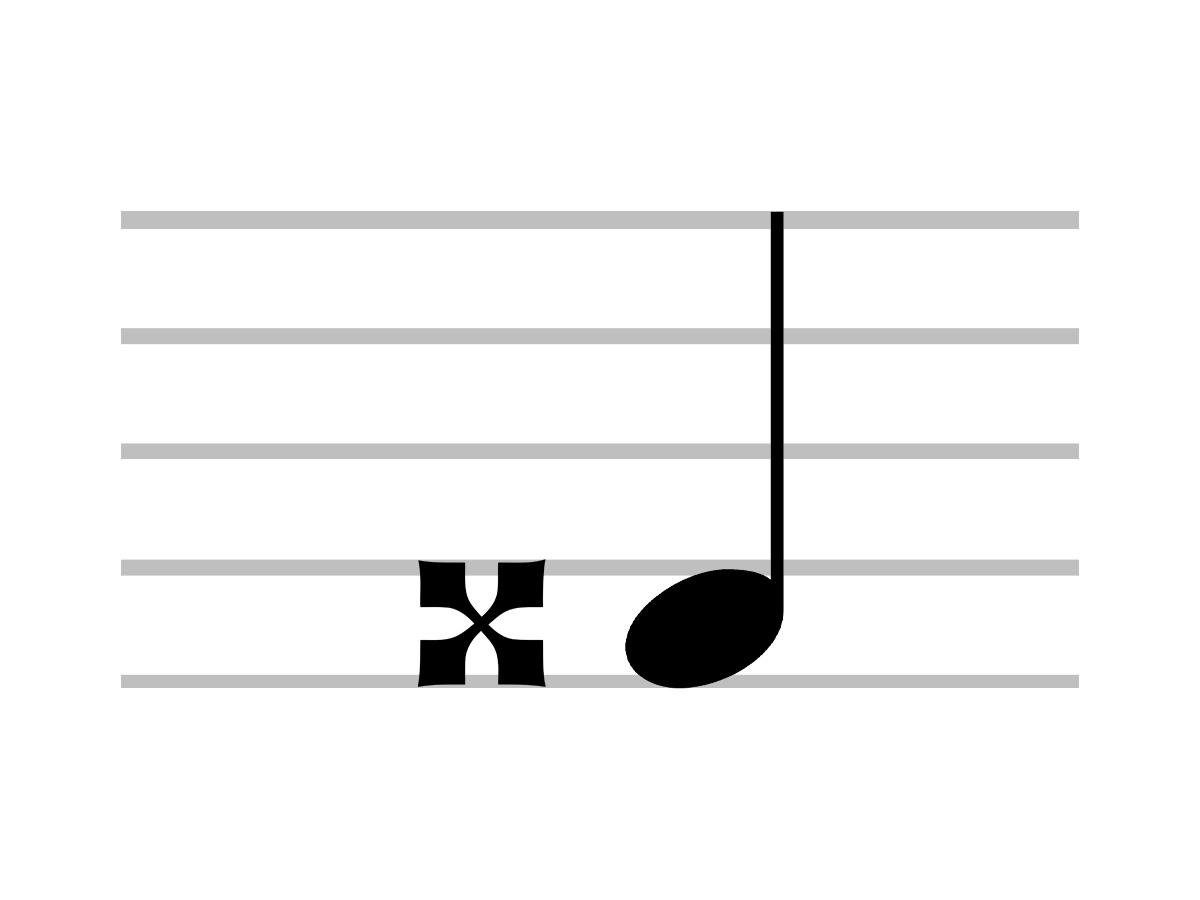

Ghost notes

A ghost note is a note that contains a rhythmic value, but not pitch or timbre. Guitarists often execute ghost notes by muting the strings, whereas drummers play ghost notes very softly in between accented beats. It’s represented by a saltire cross (that looks like an X) in the place of what usually is a note head.

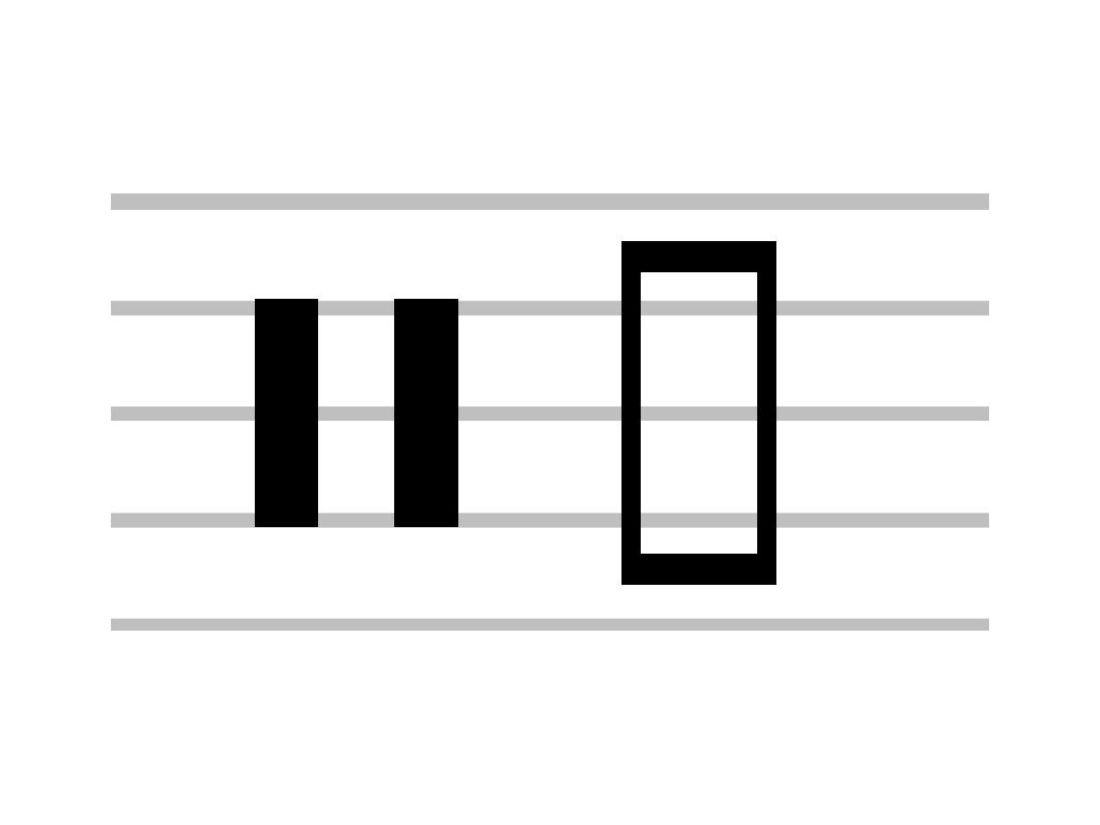

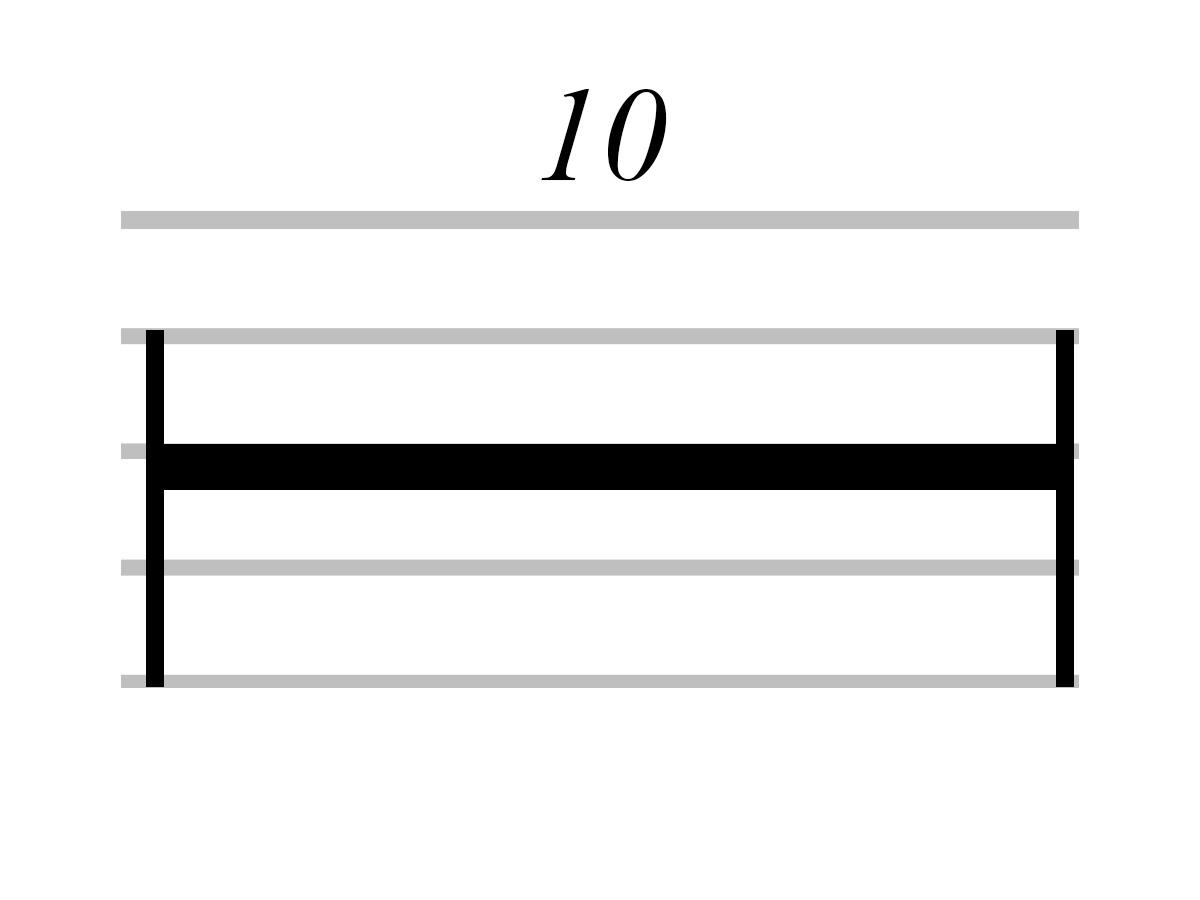

Multi-measure rest

A multi-measure rest (a.k.a gathered rest or multi-bar rest) is a symbol to indicate multiple measures of rests in a piece that go through many bars.

Breaks

Break symbols tell the performers to take short breaks, whether by breathing or allowing a brief space between notes or phrases during the piece.

Breaks are instructions for the performer’s action in playing the music, whereas rests are musical notation that translates into silences.

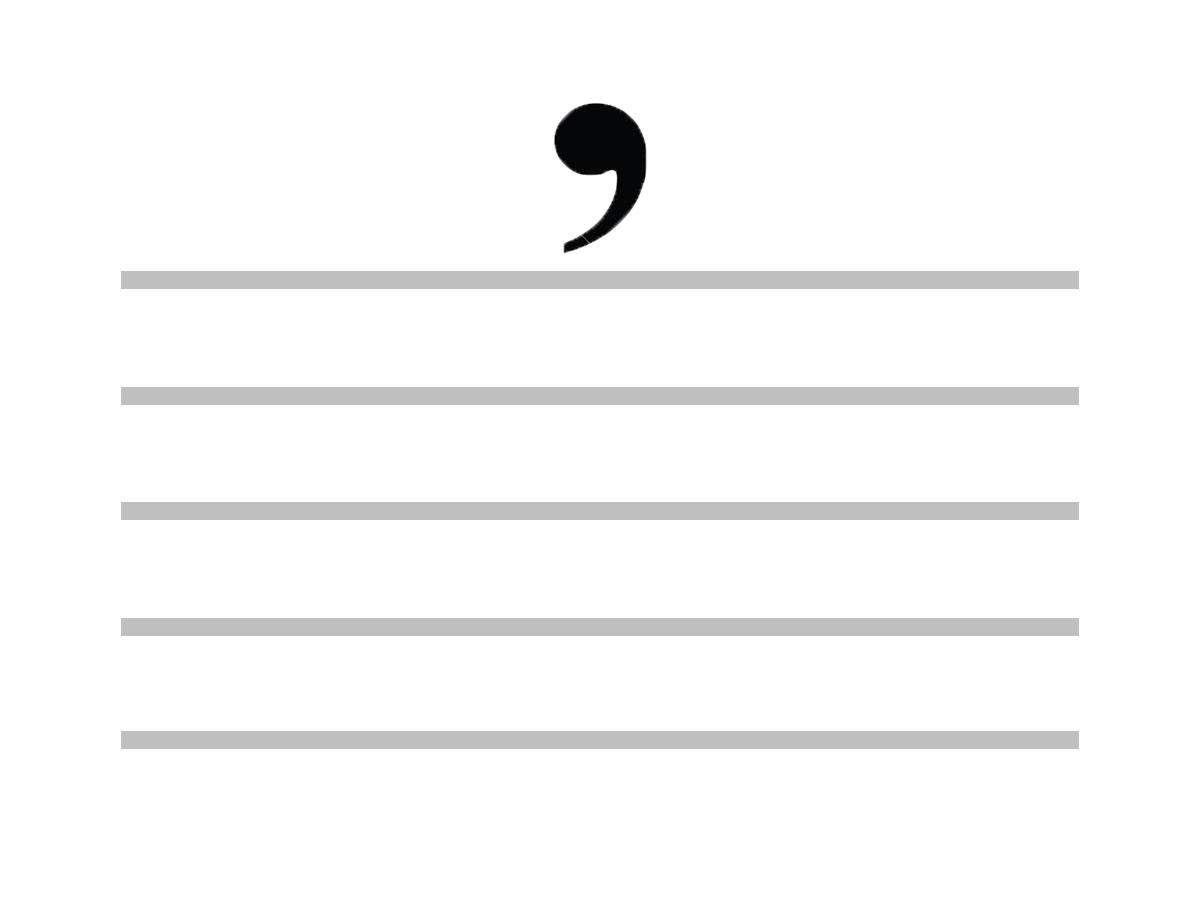

Breath marks

A breath mark instructs the aerophones performers to take a breath or other instrument players to leave a very brief space. For instruments with a bow, it instructs the player to lift the bow and start the following note with a new bowing direction.

Caesura

A caesura indicates a break or pause in a verse, usually to separate one phrase from the next. It can be symbolized by a comma, a tick, or two straight or slashed lines.

Accidentals

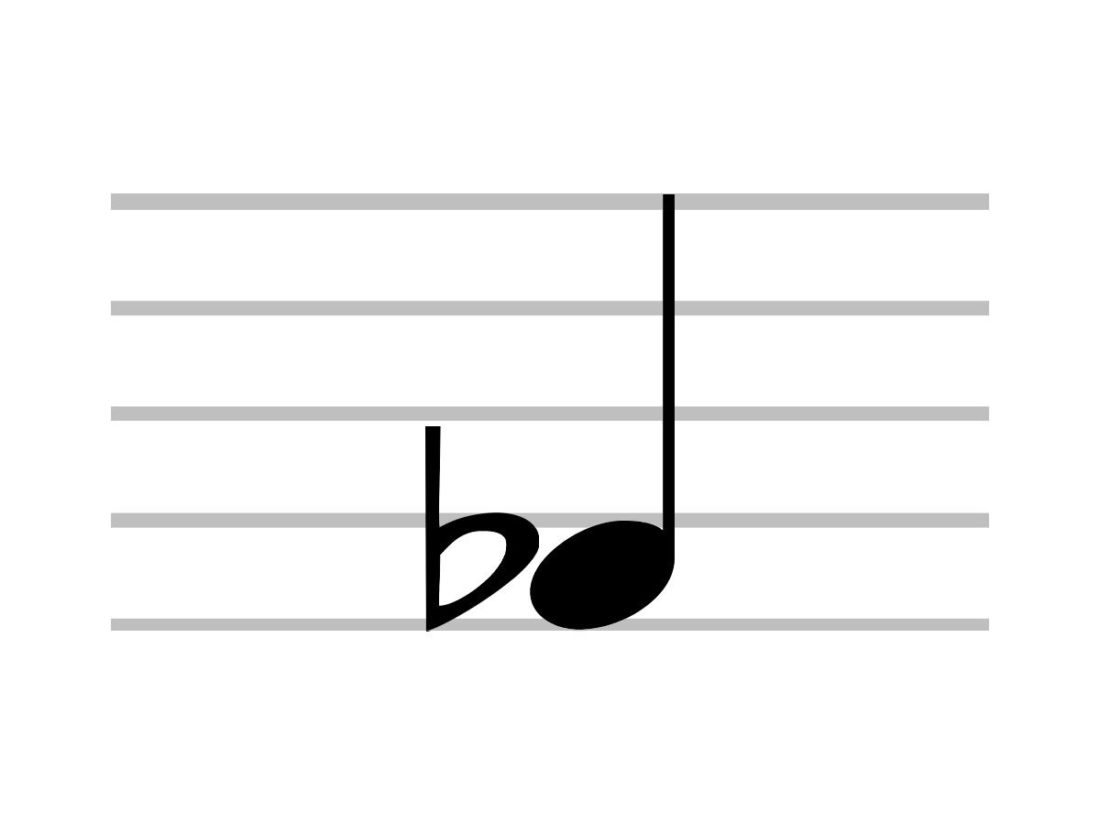

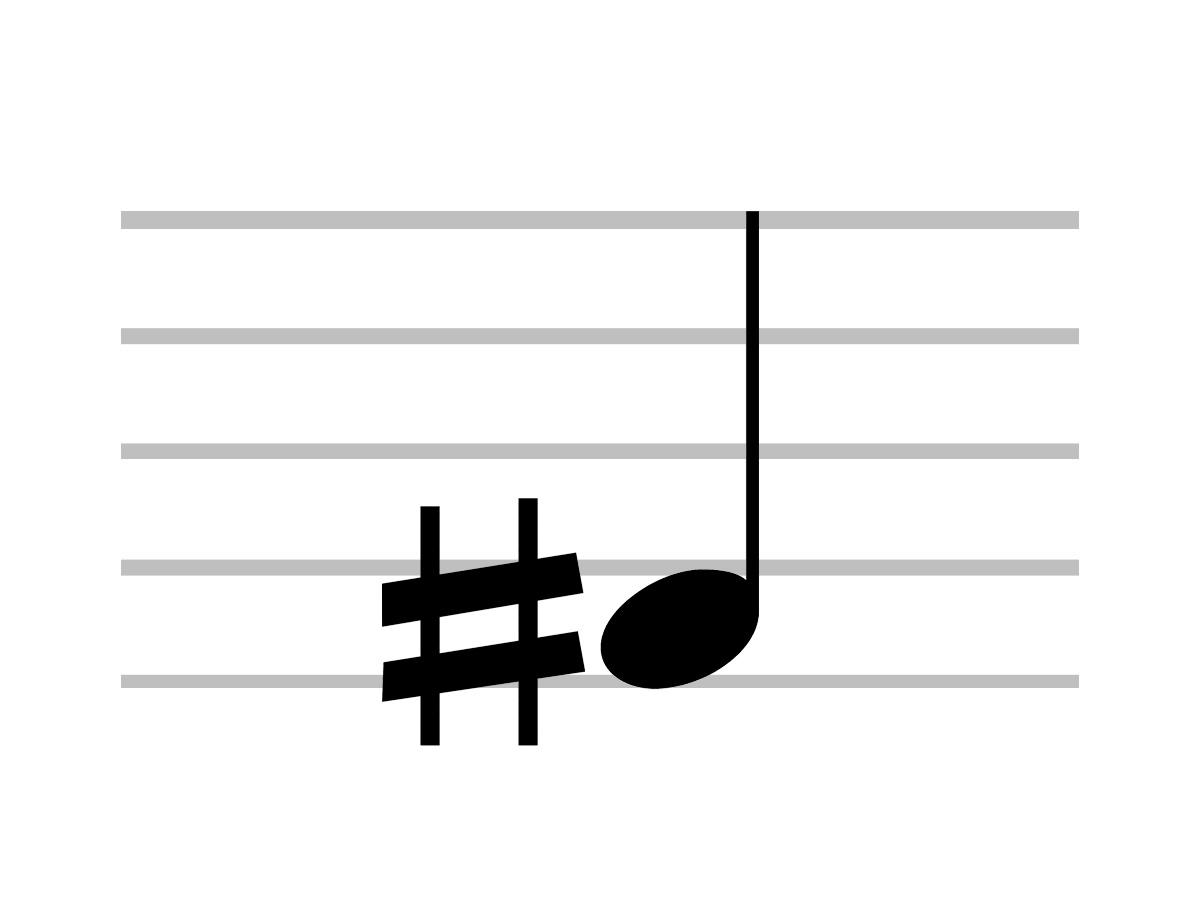

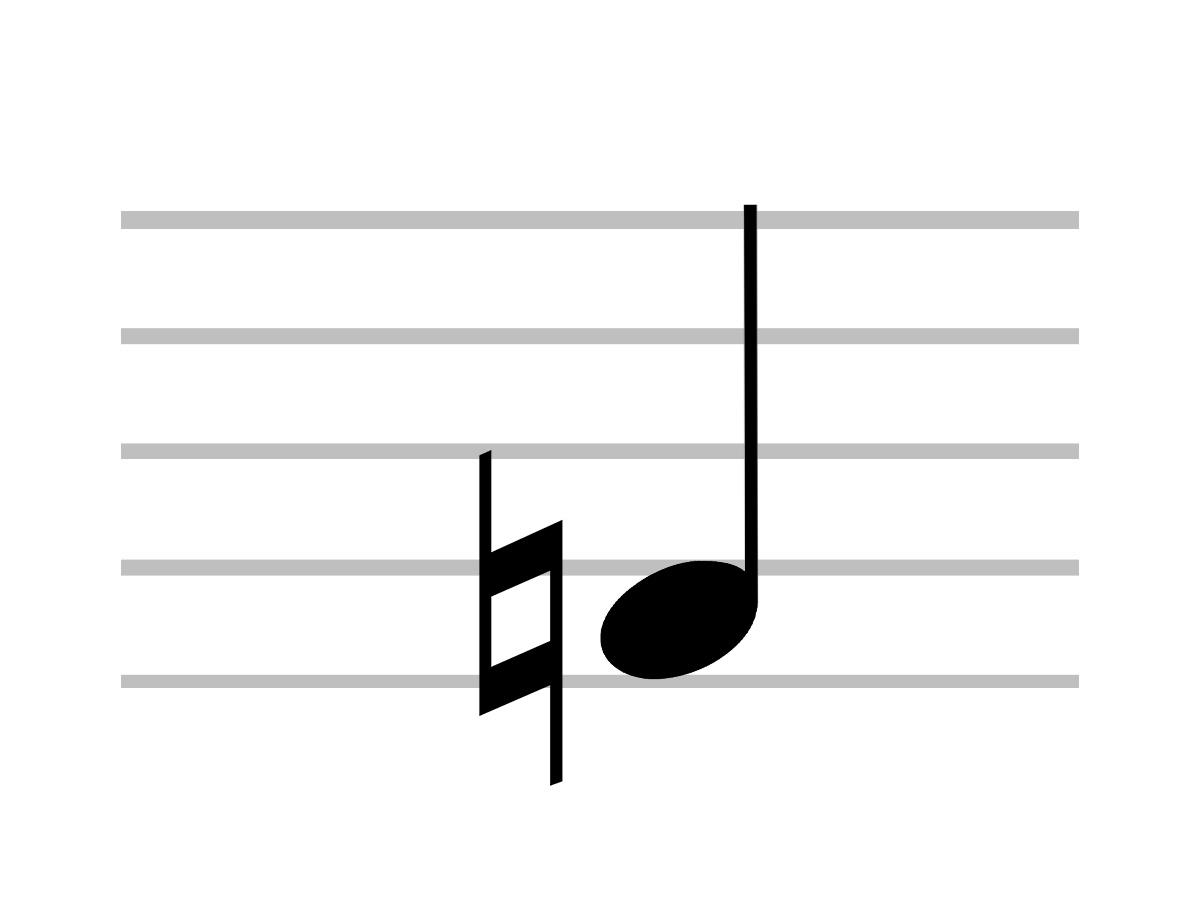

In music, accidentals are notes of a pitch that aren’t the official member of the scale indicated by the key signature. The sharp (♯), flat (♭), and natural (♮) are the most common markers for these notes.

- Flat

- Sharp

- Natural

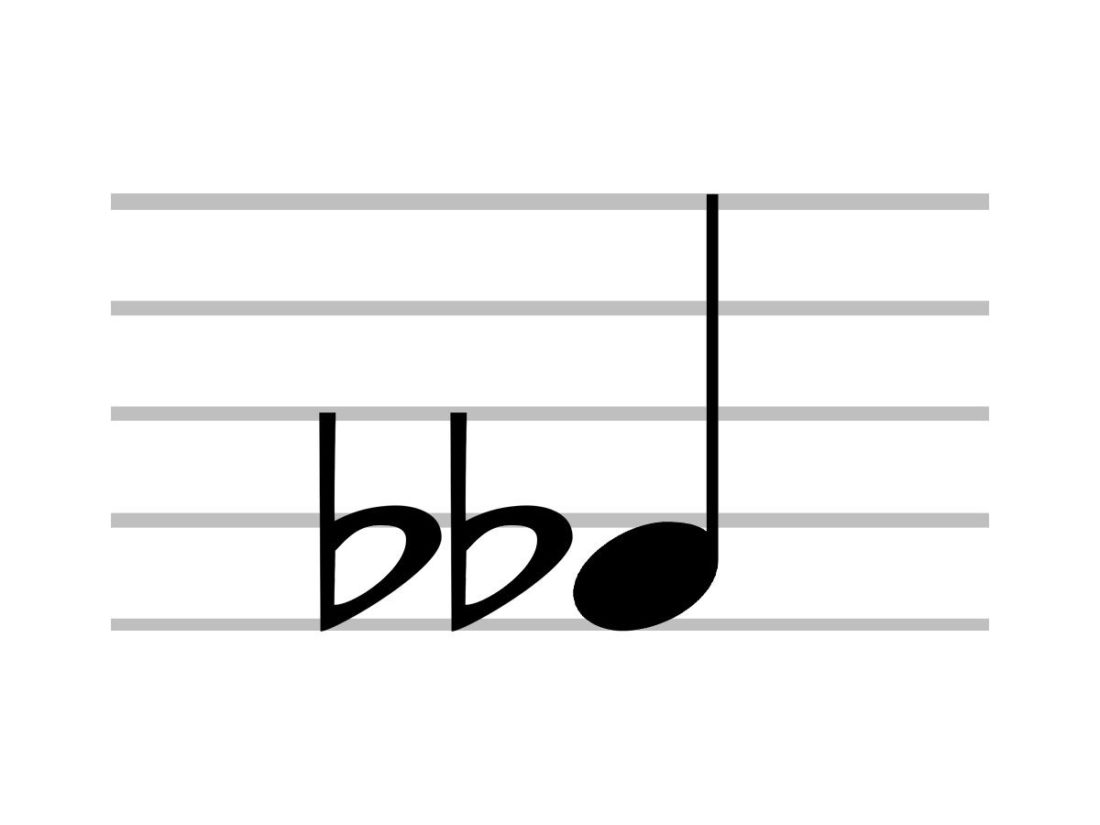

- Double flat

- Double sharp

Flat

In music, a flat means that a note is lower in pitch. A flat mark means the note has a one-semitone lower pitch than its natural form.

Semitones are also known as half-step or half-tone

Sharp

In music, a sharp means that a note is higher in pitch. A sharp mark indicates that the pitch of a note is one semitone higher than its natural form.

Natural

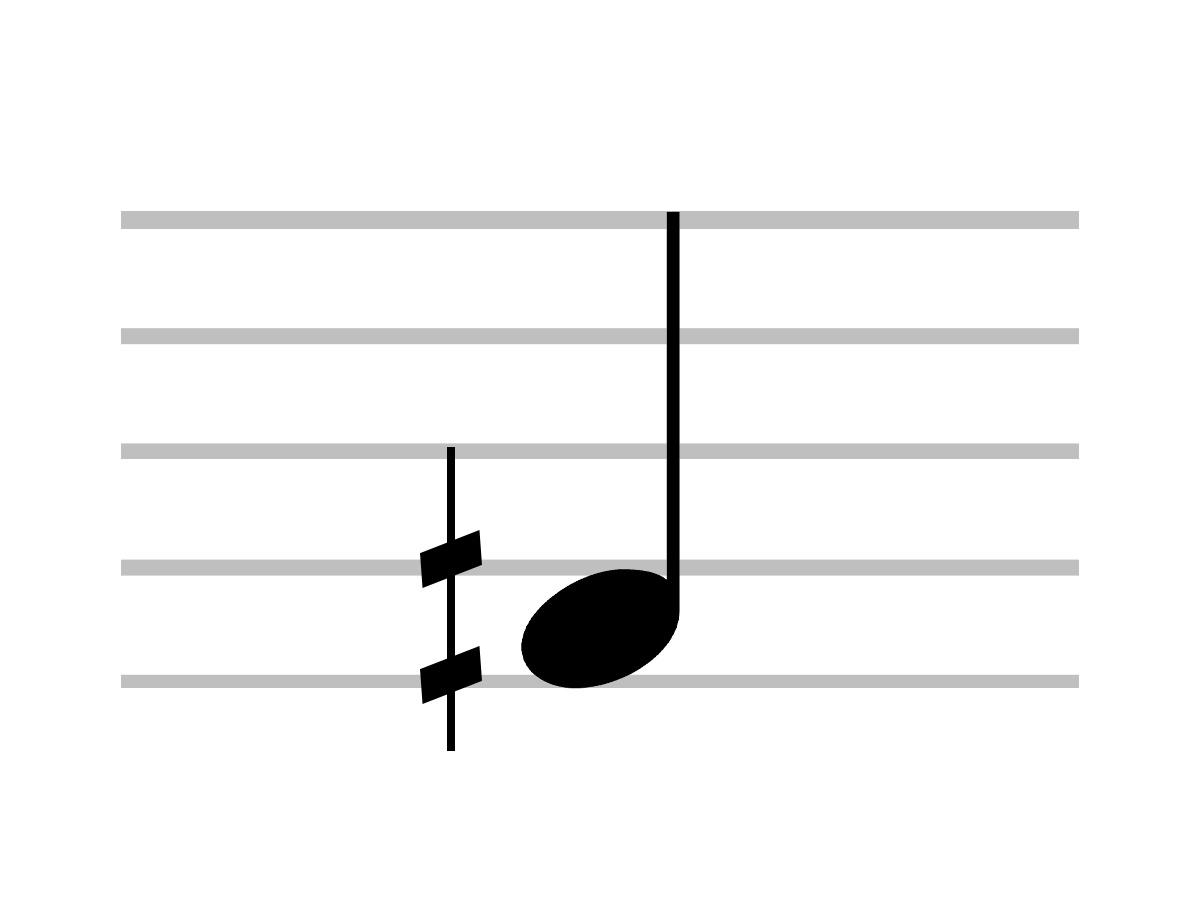

Depending on the key signature, the notes in a section may have pre-assigned sharps or flats as stated at the beginning of the staff. A natural mark neutralizes these pre-assigned sharps or flats and brings the note back to its natural pitch.

Double flat

A double flat means that the pitch of a note is two semitones lower than its natural form. The double flat is typically used when the note is already flat in the key signature.

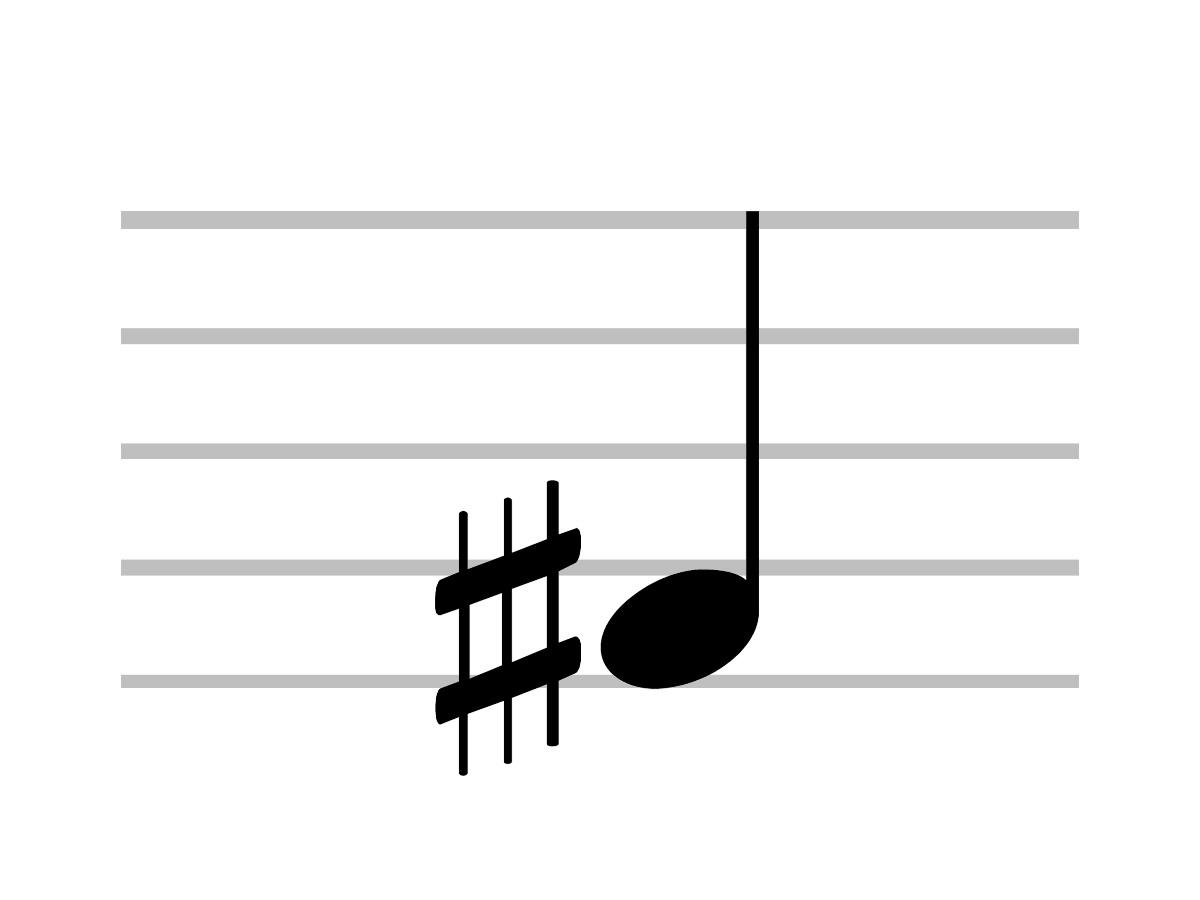

Double sharp

A double sharp means that the pitch of a note is two semitones higher than its natural form. The double sharp often appears when the note is already sharp in the key signature.

Key Signatures

Key signatures indicate which notes need to be played as sharps or flats.

Notes that are sharp or flat in a key signature dictate that they will be played as such all the way to the end of the piece.

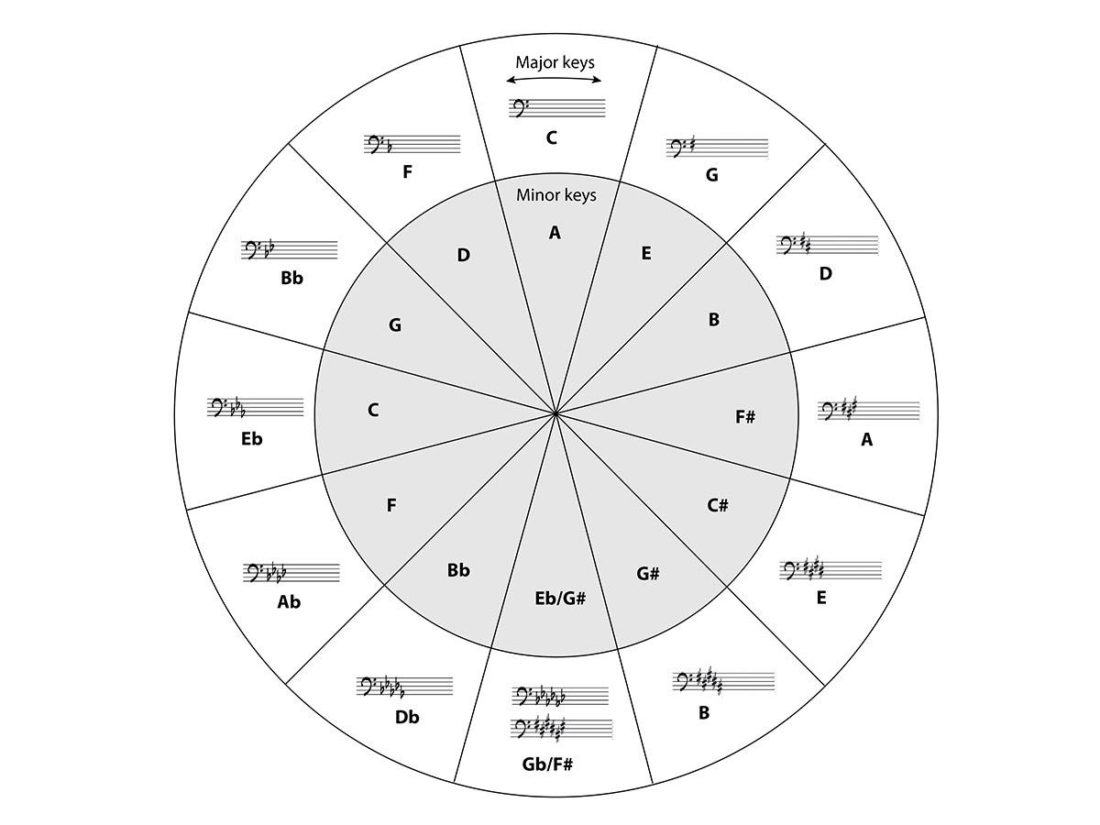

The key signatures are typically illustrated in the circle of fifths, a circular diagram used to summarize the relationship among the 12 tones of the chromatic scale, their corresponding key signatures, and the associated major and minor keys.

Understanding the circle of fifths will help you understand the relationship among 12 tones of the chromatic scale. Learn more about it here.

Microtones

Microtonal music doesn’t have a universally accepted notation method due to the varying systems used depending on the circumstances. Microtones are very common in pieces for instruments that have more flexibility and spaces between notes. It’s almost non-existent for piano pieces since the piano is limited to half semitone movements.

These are the most common microtonal notation forms right now:

- Demiflat

- Flat-and-a-half

- Demisharp

- Sharp-and-a-half

- Harmonic falt

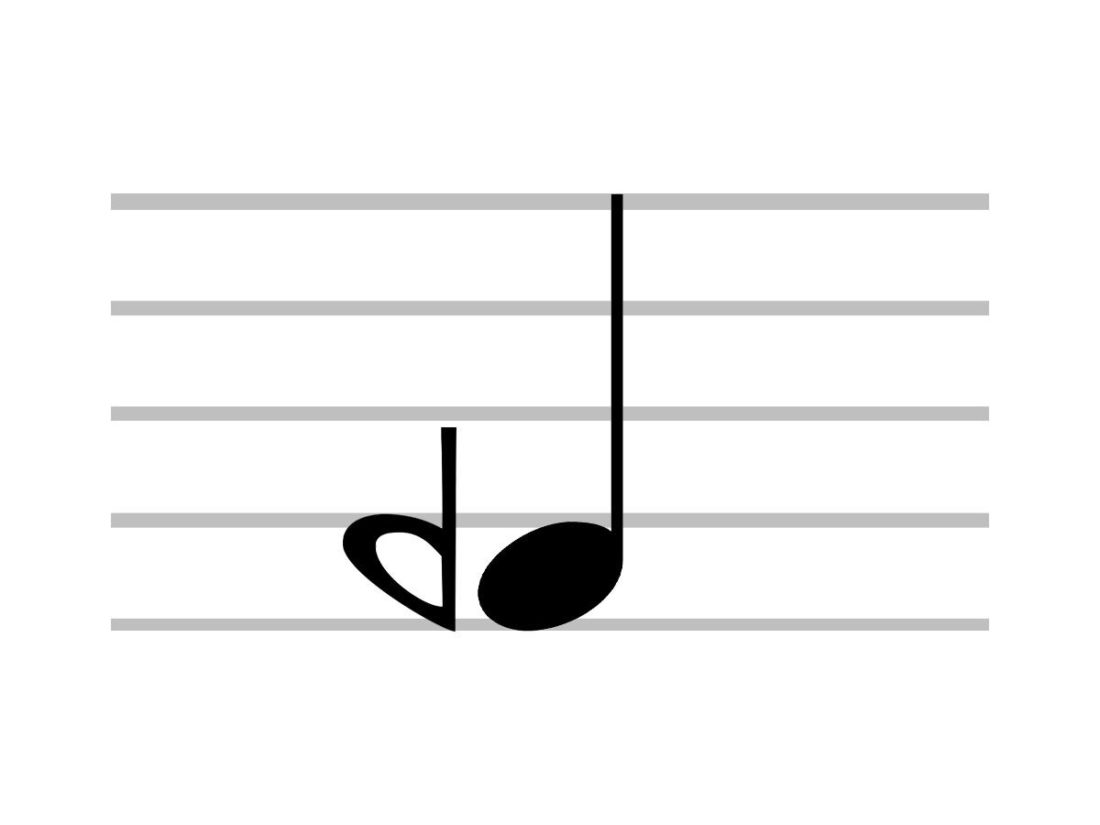

Demiflat

A demiflat is represented by a flipped flat symbol. It lowers the pitch of a note by a quarter of the natural sound. Another way to write a demiflat is by drawing a diagonal slash through a flat symbol.

Flat-and-a-half

A flat-and-a-half lowers the pitch of a tone by three-quarter tones. It’s also common for a flat-and-a-half to be represented with a slashed double flat symbol.

Demisharp

A demisharp raises the pitch of a note by one quarter of the tone.

Sharp-and-a-half

A sharp-and-a-half mark raises the pitch of a note by three-quarter tones. It also occasionally appears as two verticals and three diagonal bars.

Harmonic flat

The harmonic flat lowers the pitch of a note to match the indicated number of the harmonic series of the root note, which is the lowest note in a chord. The harmonic series of a note refers to a series of higher frequencies that occurs when a note is played.

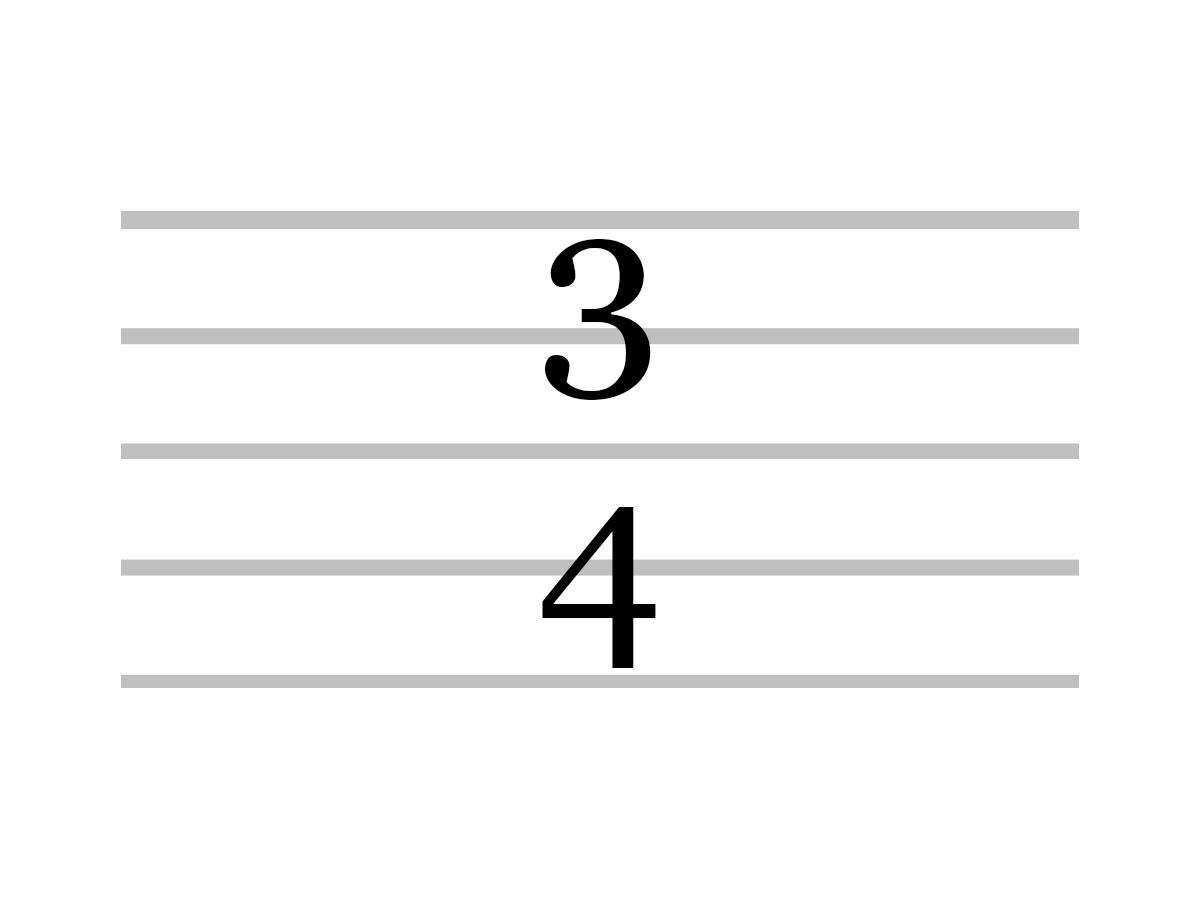

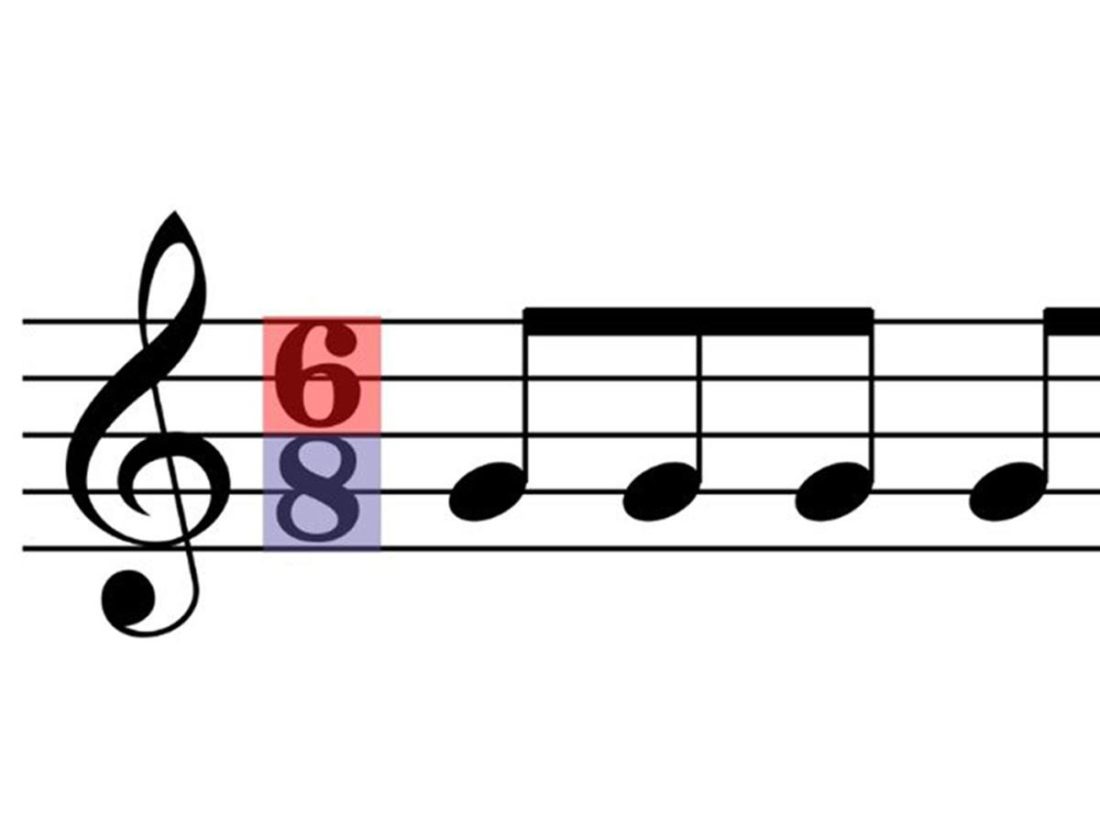

Time Signatures

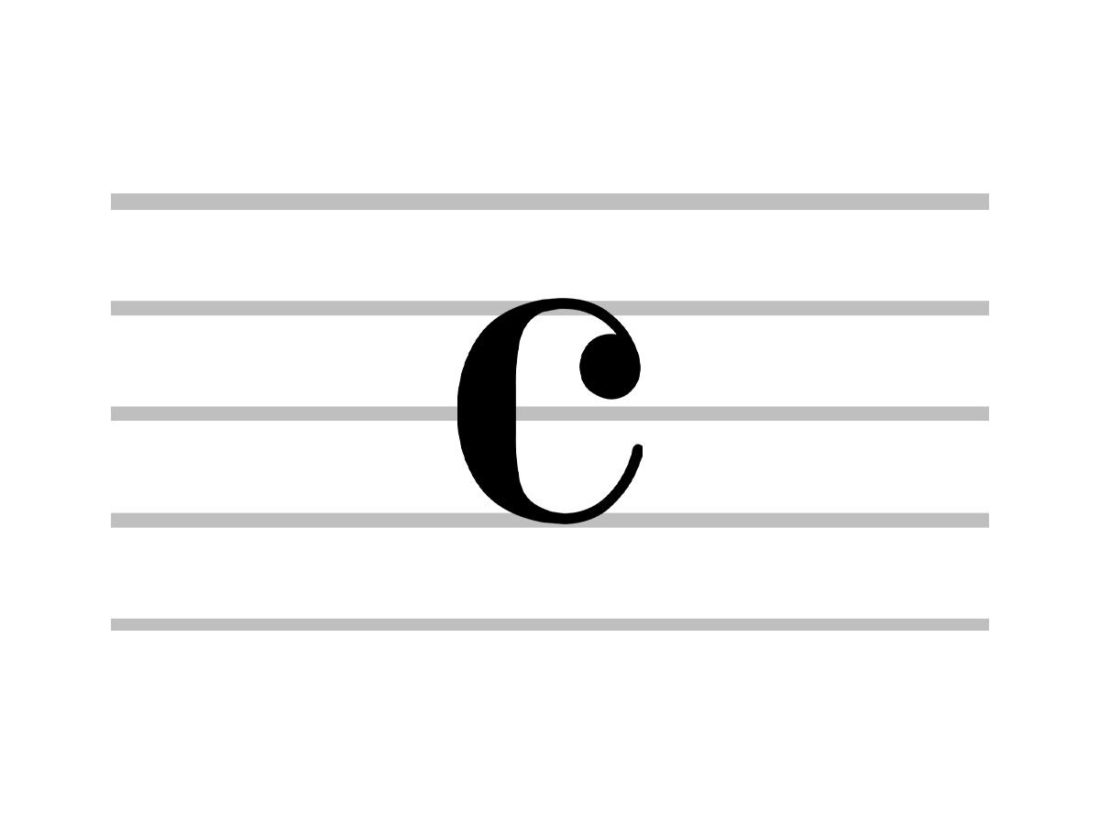

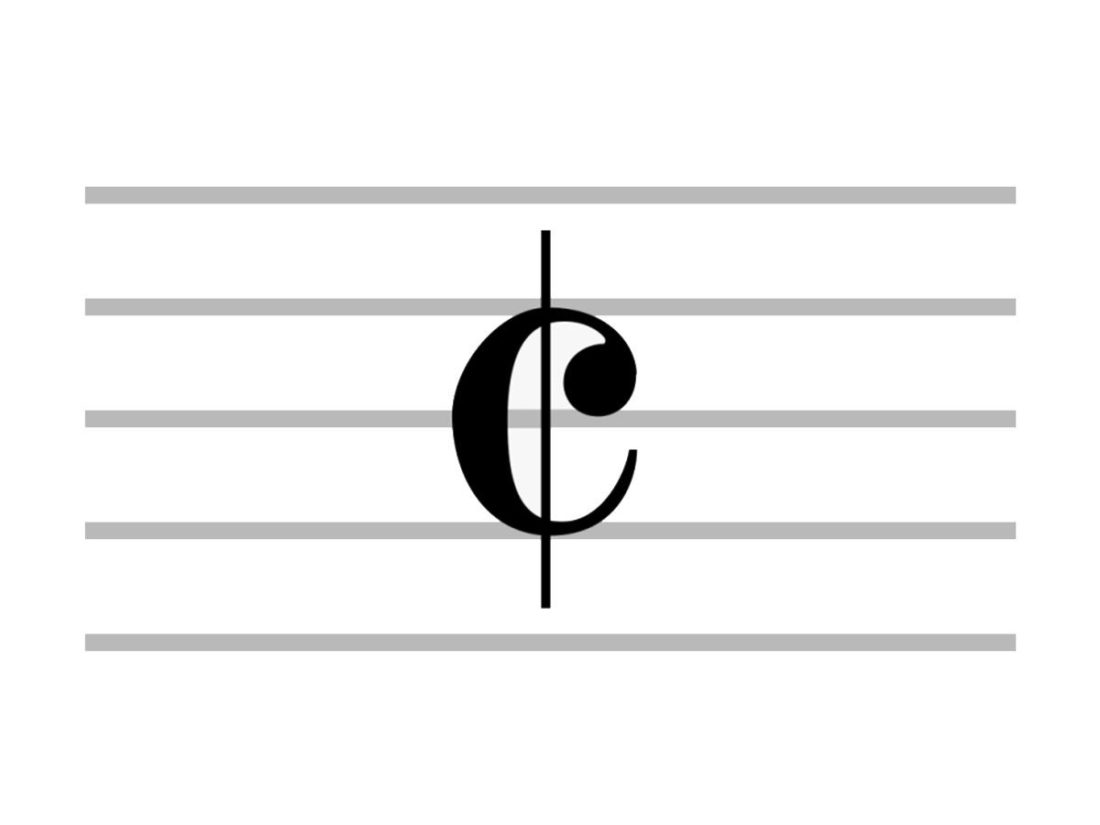

The time signature is a notational convention that specifies how many beats are in each bar and tells which note value (the duration of a note) is equivalent to a beat. In sheet music, the time signature appears at the beginning as a time symbol or a stacked numeral like C or ¾.

Most people wrongfully pronounce time signatures as fraction (i.e. three-fourth), but the correct pronunciation is ‘two-four’, ‘three-four’, ‘four-four’, etc.

- Simple time signatures

- Compound time signature

- Common time

- Alla breve

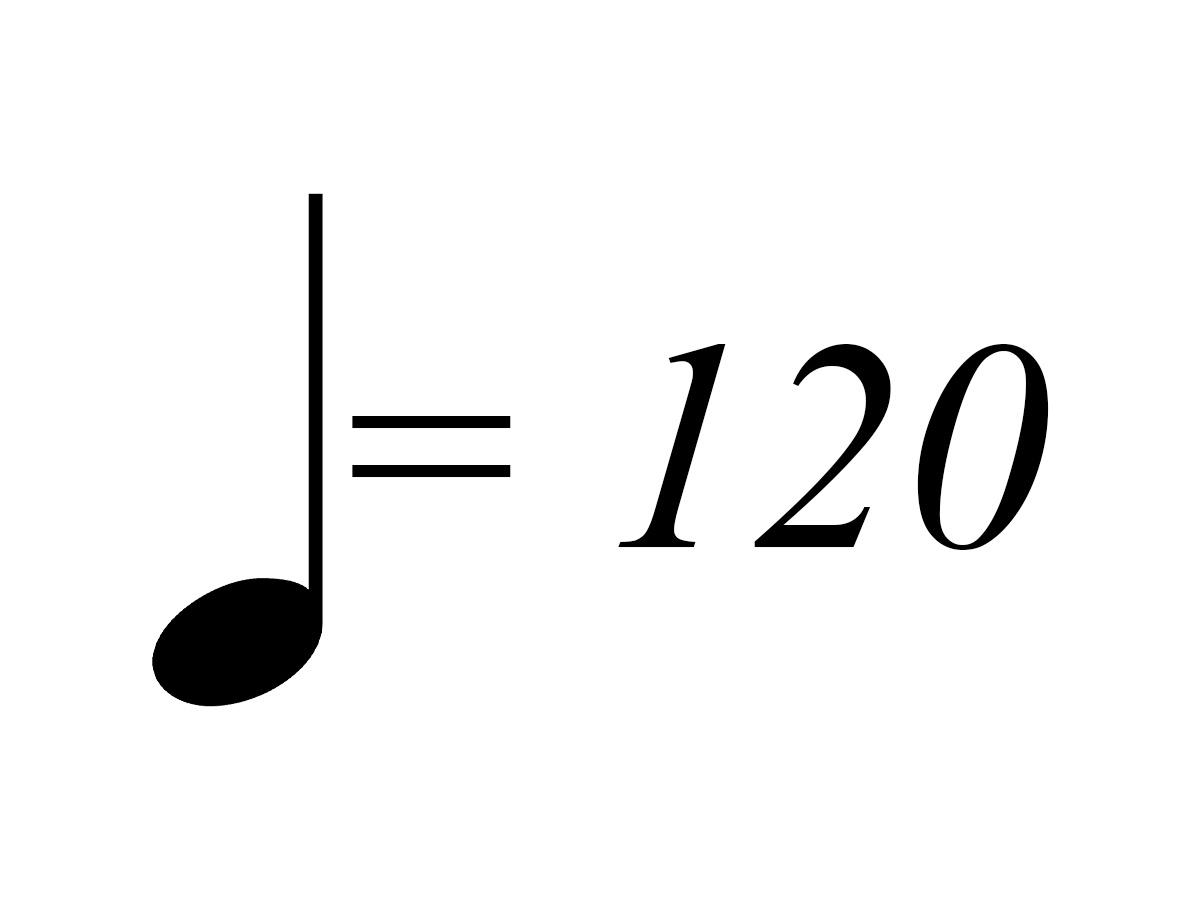

- Metronome mark

Simple time signatures

A simple time signature consists of two numbers stacked together. The upper numeral indicates the number of beats, whereas the lower numeral indicates the note value for one beat. The most common examples of simple time signatures are 4/4, 3/4, 2/4, 3/8, and 2/2.

Compound time signature

In a compound time signature, the upper number of the beat is evenly divisible by three (e.g. 6/8, 12/8, and 9/4). It signifies that the beats in the piece are broken down into three-part rhythms, with the exception of time signatures with three as the upper number.

Common time

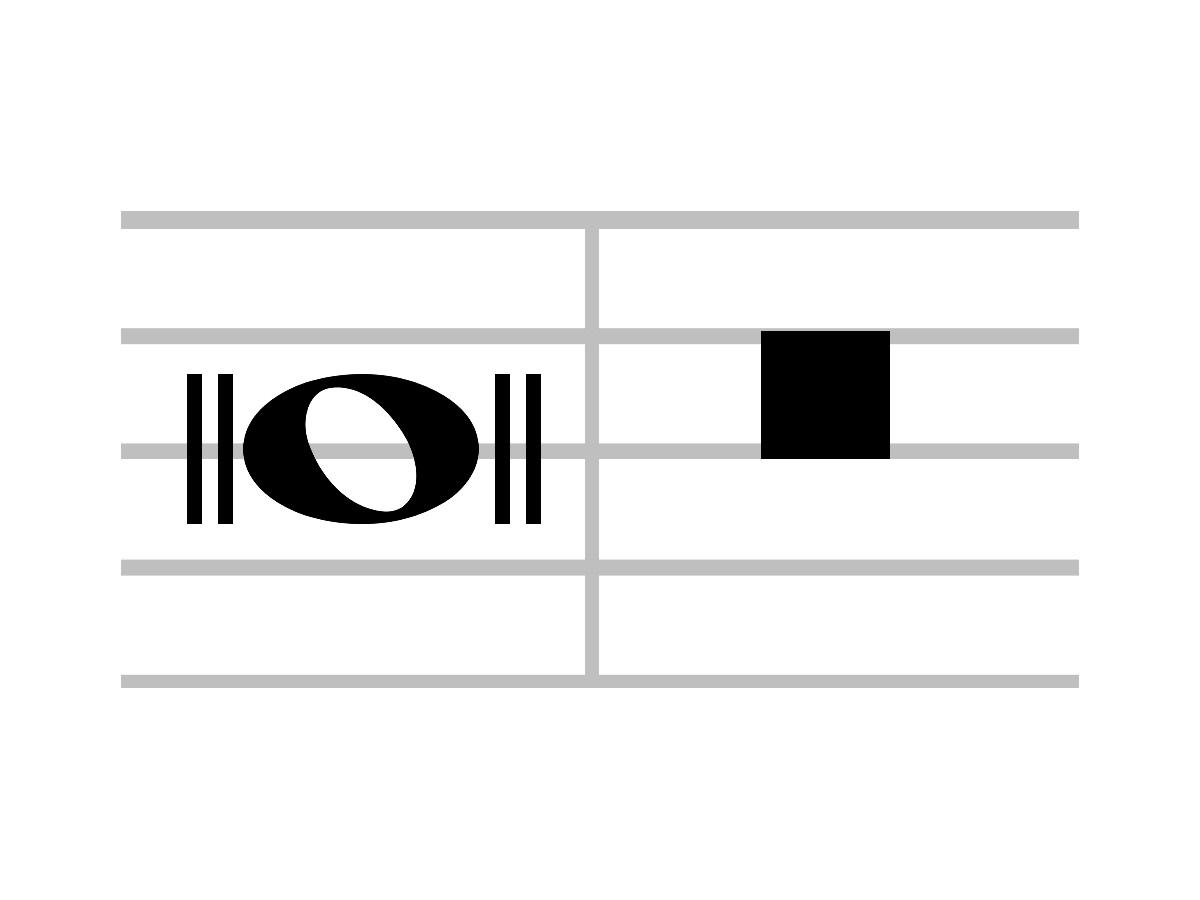

The common time signature (C) is often used to represent a 4/4 time (imperfect time). While the symbol looks like the letter C, it’s derived from a broken circle used in music notation from the 14th to 16th centuries.

Alla breve

Alla breve, or cut time, is a musical meter notated by a C with a vertical line through it. The alla breve is equivalent to 2/2 in the time signature.

Metronome mark

The metronome mark shows the speed of the music by using the beats per minute (bpm) measurement. A metronome mark can either be precise, i.e., 176 bpm, or in a range, i.e., 152-176 bpm.

Note Relationship

Symbols in this category represent the relationship between one note and another. These symbols tell the performer how to transition between notes to get the best melody and harmony.

- Tie

- Slur

- Glissando or portamento

- Tuplet

- Chord

- Arpeggiated chord

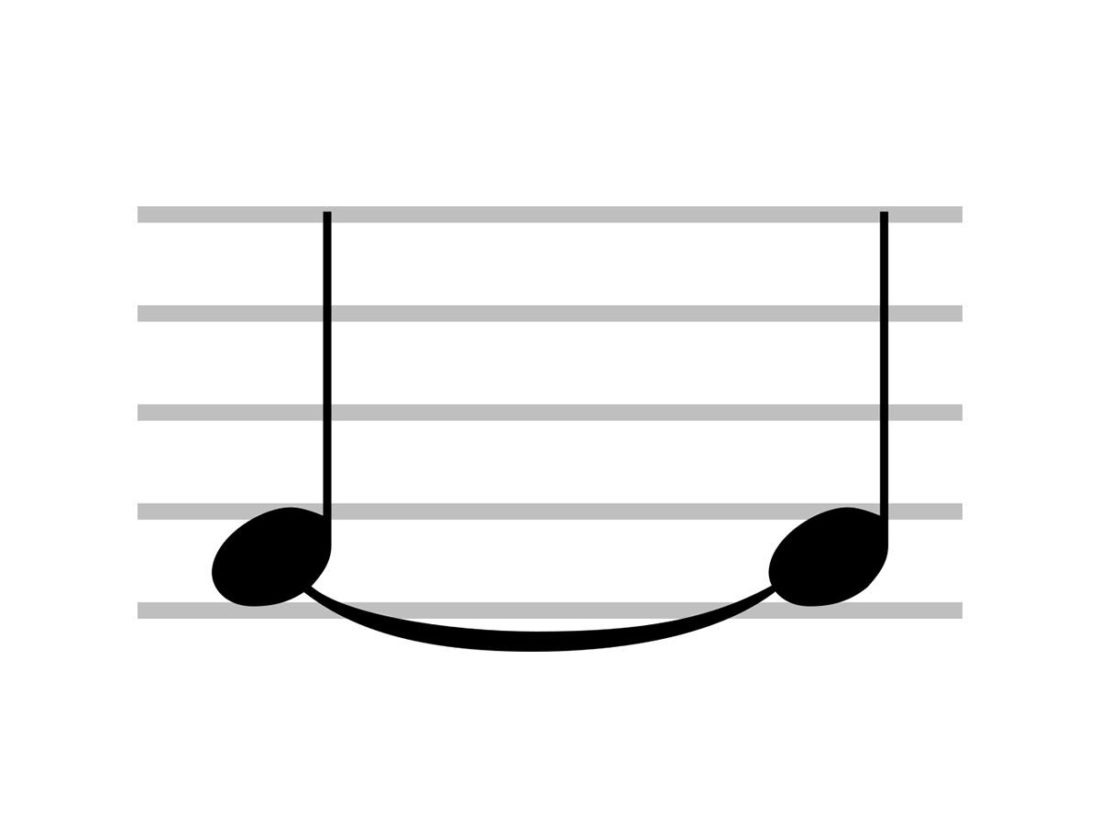

Tie

A tie is a curved line connecting the heads of two notes with the same pitch. Tied notes are an indication that they should be played as a single note with the total duration of both notes.

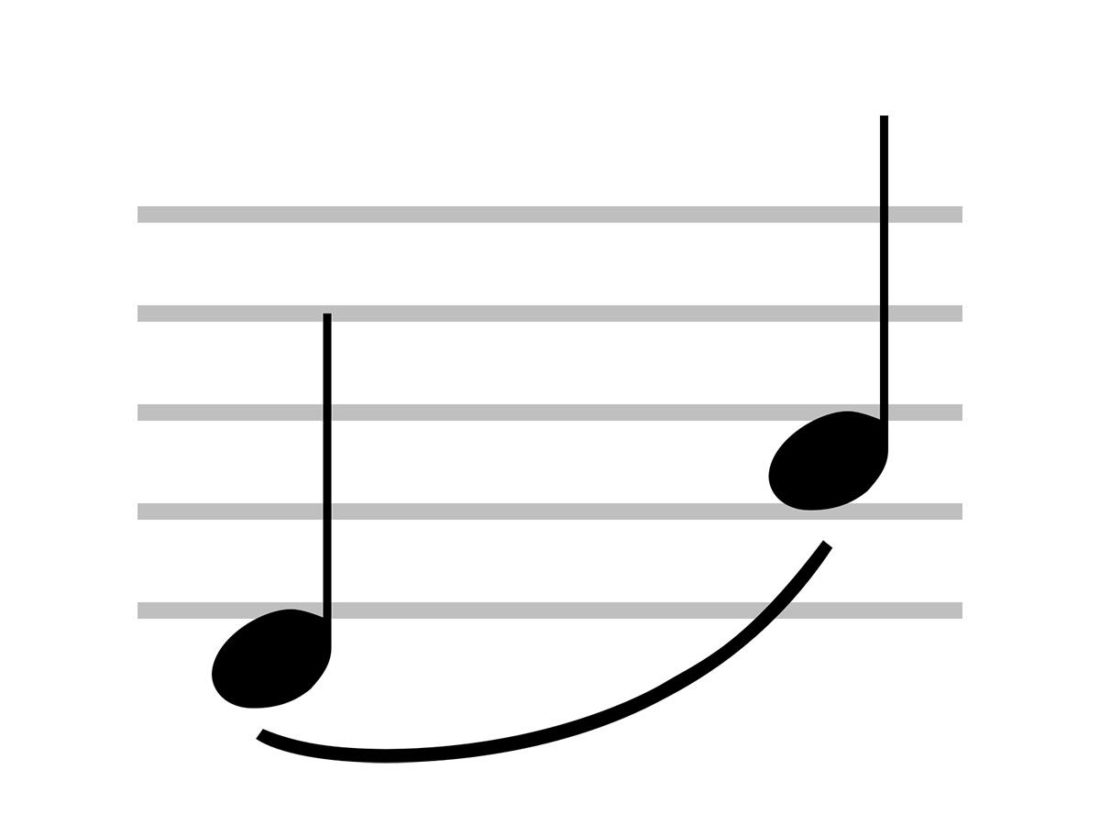

Slur

Notes bound by a slur means that the performers should play them without separation. It’s represented with a curved line above the notes if the stems point downward and below the notes, if the stems point upwards.

Glissando or portamento

A glissando represents a glide from one pitch to the next. Instruments like the trombone, timpani, and cello can continuously make this glide, which will be classified as portamento.

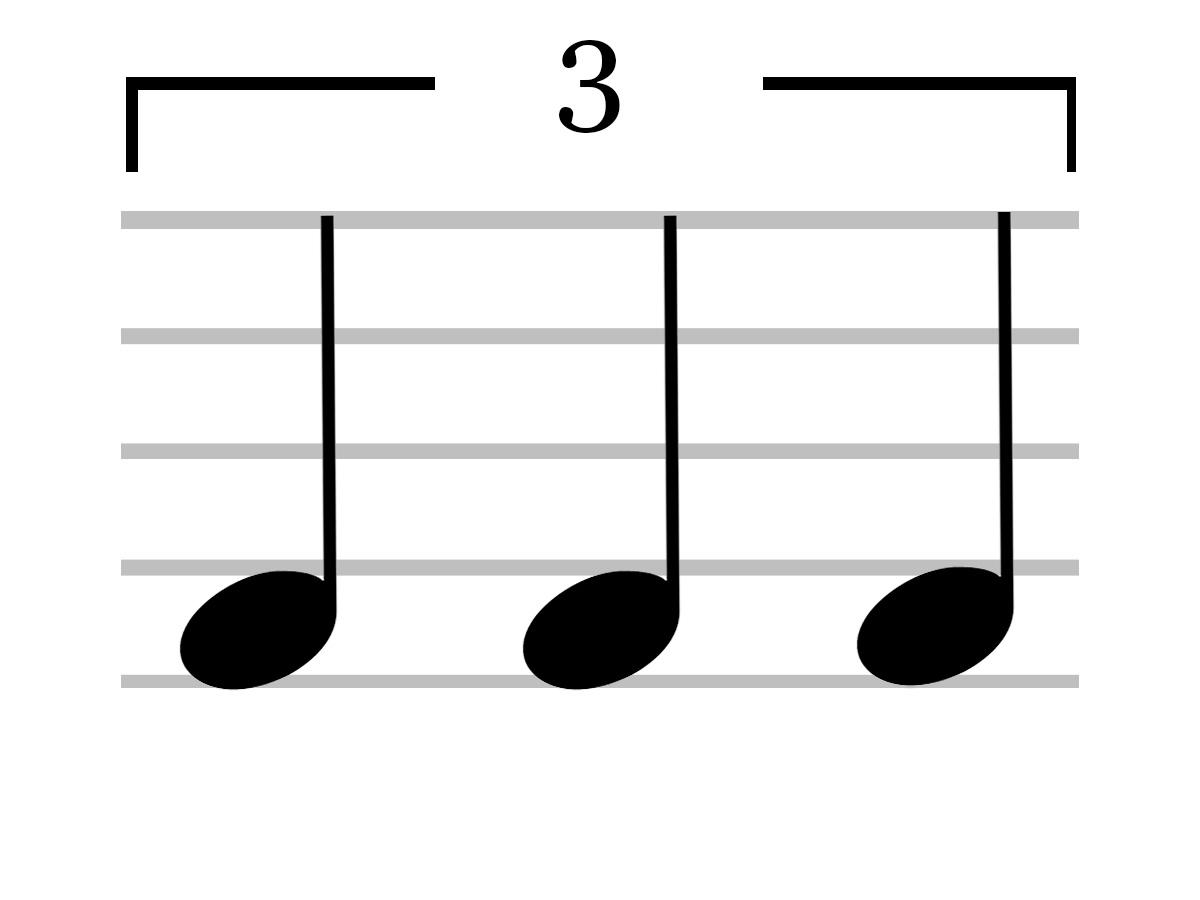

Tuplet

A tuplet is any rhythm that involves dividing a beat into subdivisions permitted by the time signature. Tuples are played by fitting in the number of fractions within the duration of the subdivision. The example means that there are 5 notes that need to be played within the duration of four notes.

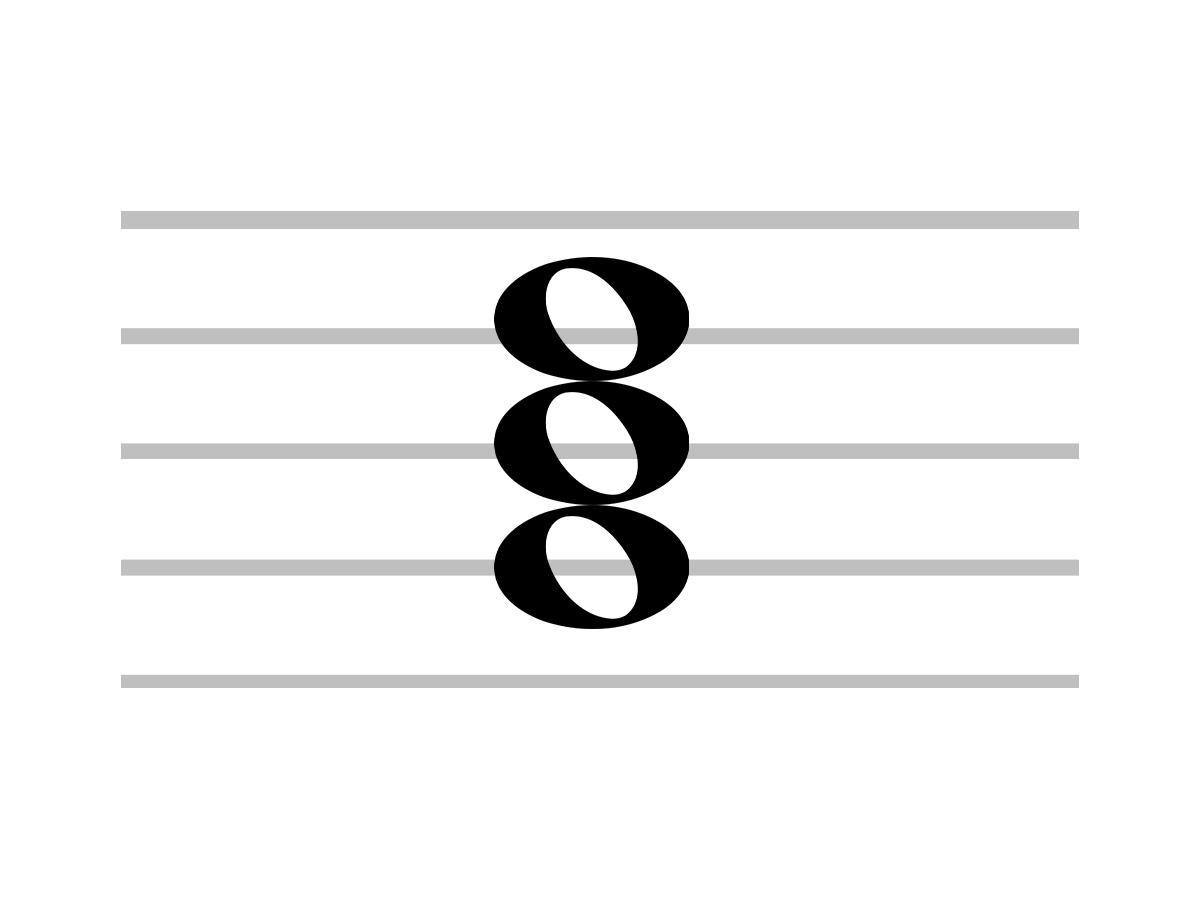

Chord

Chords are several notes that are played simultaneously to form a harmonic set of pitches or frequencies. Two-note chords are called dyads, while three-note chords are called triads.

Arpeggiated chord

Arpeggiated chord is a broken chord where the notes that compose it are played in a quick succession in an ascending or descending order. A regular squiggly line (or with an upwards arrow) means ascending order, whereas a squiggly line with a downward arrow means descending order.

The word arpeggio originates from arpeggiare, which is Italian for ‘to play on a harp.’

Dynamics

The dynamics of musical pieces indicate the level of loudness between notes or phrases. These symbols determine how loud or quiet the performer should play a note.

- Pianississimo

- Pianissimo

- Piano

- Mezzo piano

- Mezzo forte

- Forte

- Fortissimo

- Sforzando

- Crescendo

- Diminuendo

- Niente

Pianississimo

Pianississimo means that the tone has an extremely quiet pitch.

Pianissimo

Pianissimo means that the tone has a very quiet pitch.

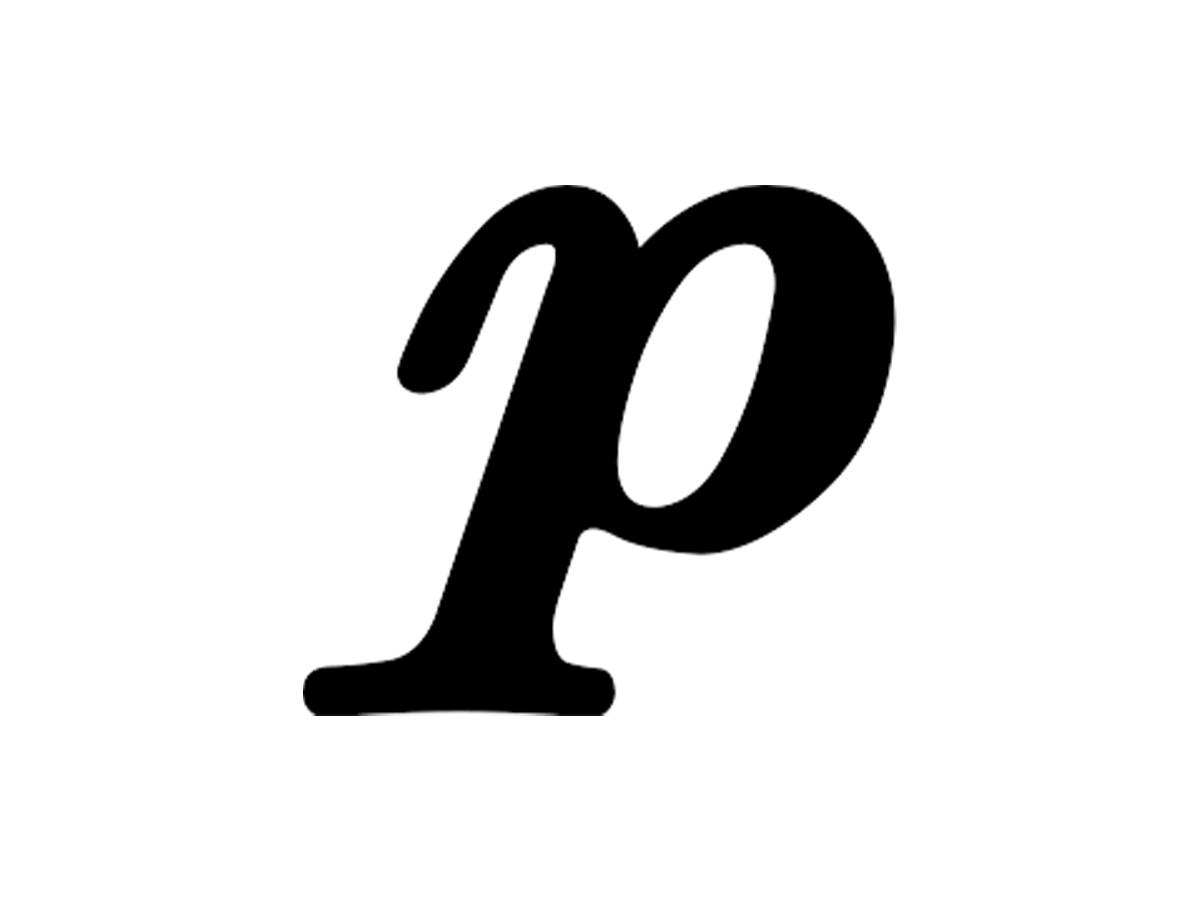

Piano

Soft, but louder than pianissimo. The word ‘Piano’ itself means “quiet.”

Mezzo piano

Mezzo piano means that the note has a slightly soft volume but is still louder than the piano.

Mezzo forte

Mezzo forte means that the note has a moderately loud volume.

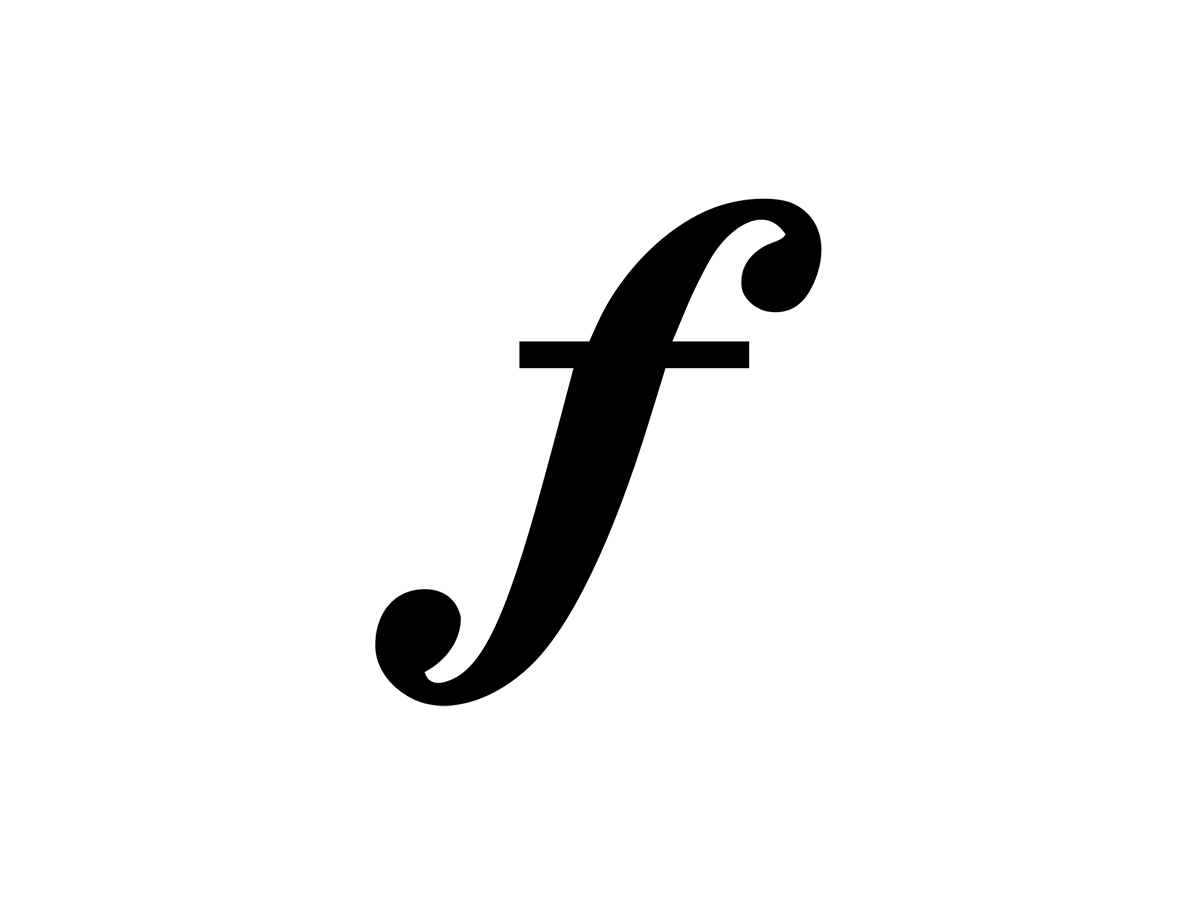

Forte

Forte means that the note is quite loud – but still at an average level.

Fortissimo

Fortissimo means that the note has a very loud volume, even louder than a regular forte.

Fortississimo

Fortississimo means that the note has an extremely loud volume.

Sforzando

It translates into “forced,” indicating an abrupt and fierce accent on a single sound.

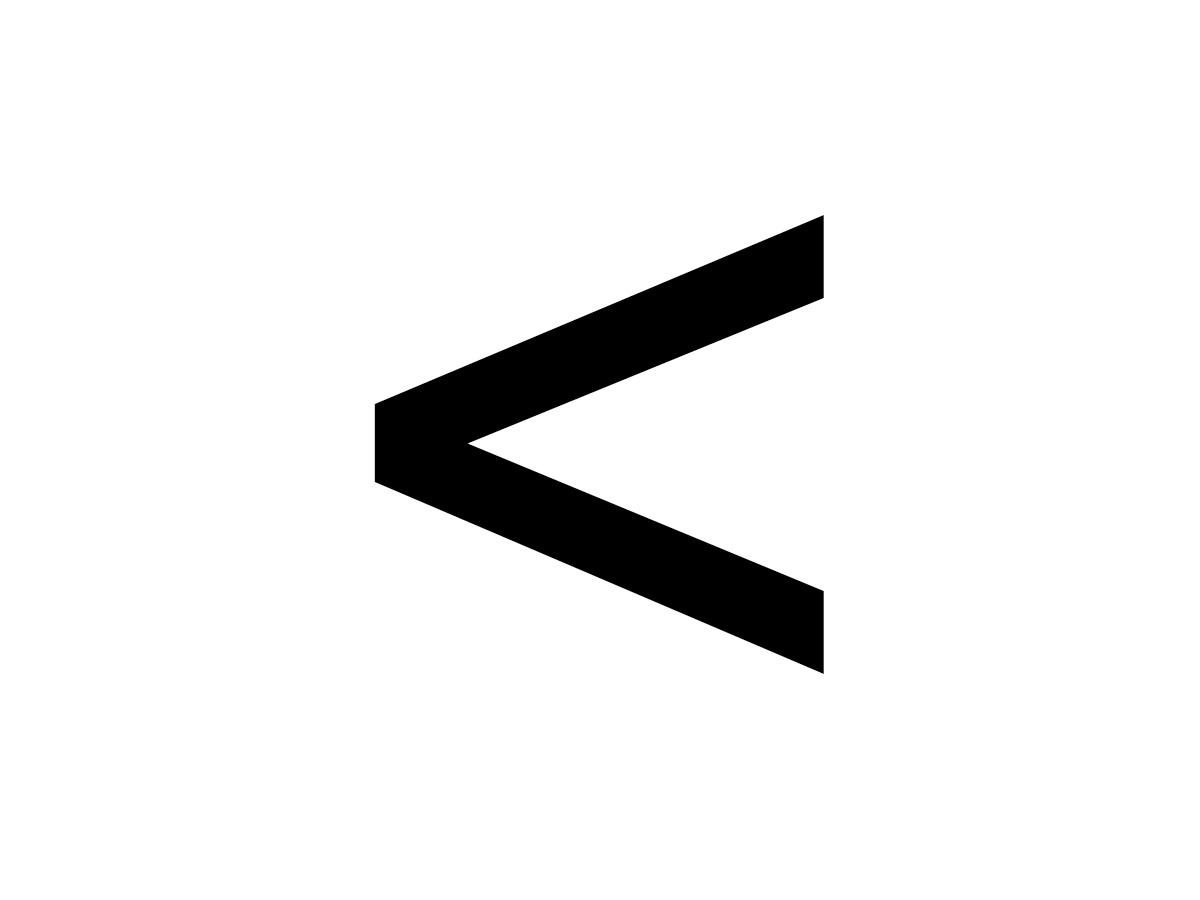

Crescendo

A crescendo means that the note will gradually get louder as it plays on.

Diminuendo

A diminuendo means that the note will slowly get quieter as it plays on.

Niente

Niente translates to “nothing.”

Mostly used at the beginning of a crescendo to indicate that the sound will start from nothing (no sound) or at the end of diminuendo to indicate the sound will fade out to nothing.

Articulation Mark

Articulation marks determine how a single note or phrase in a musical staff should be played. These marks often determine the start and end of a note and the length of its sound.

- Staccato

- Staccatissimo

- Tenuto

- Fermata

- Accent

- Marcato

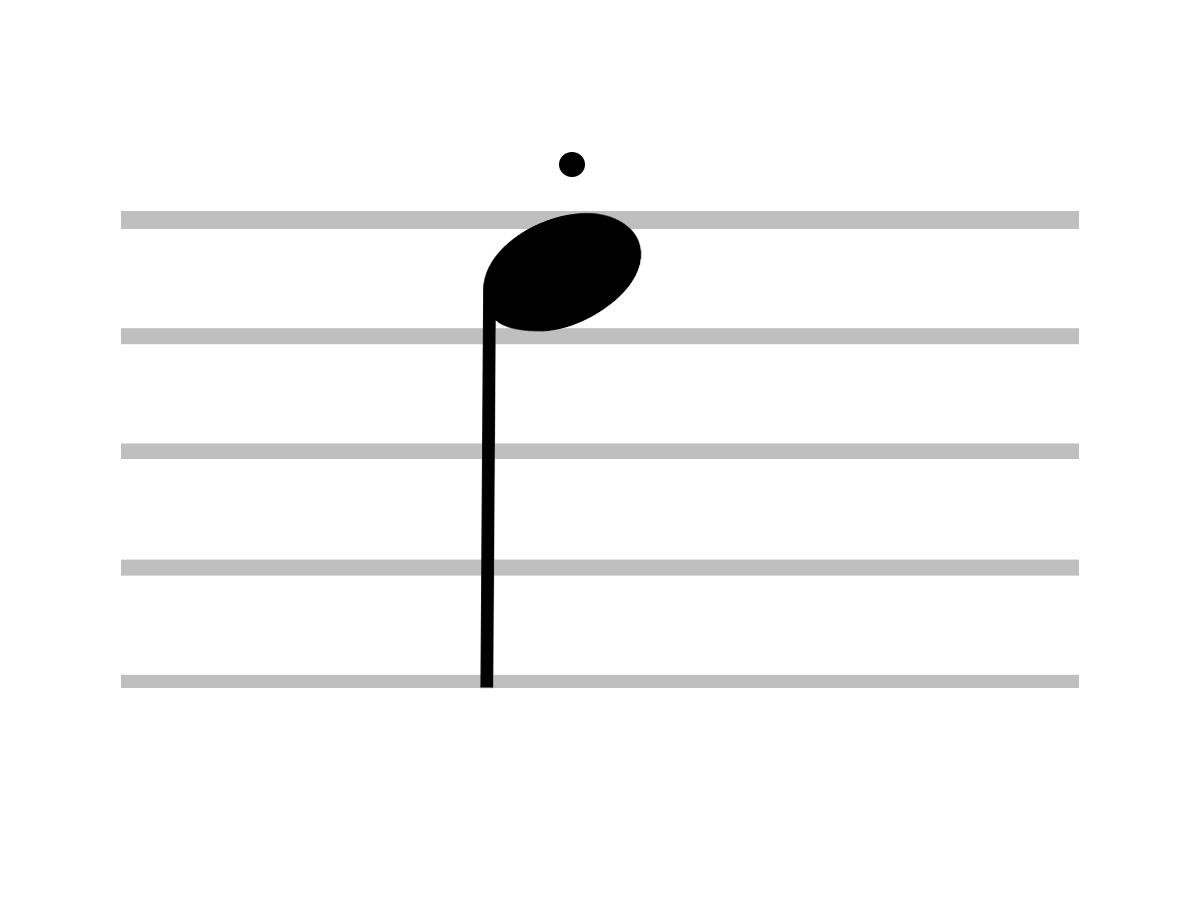

Staccato

A staccato indicates that the performer should play the note half a value shorter than what is notated and leave the remainder of the duration silent. It may appear on a note of any value and shorten the piece’s duration without speeding up the music.

Staccatissimo

A staccatissimo indicates that the performer should play the note even shorter than a staccato – usually a quarter of the original duration. It usually appears on the quarter or shorter notes.

Tenuto

A tenuto indicates that the performer should play the note at its full length or slightly longer. It sometimes also indicates a certain level of emphasis, especially when appearing together with dynamic markings.

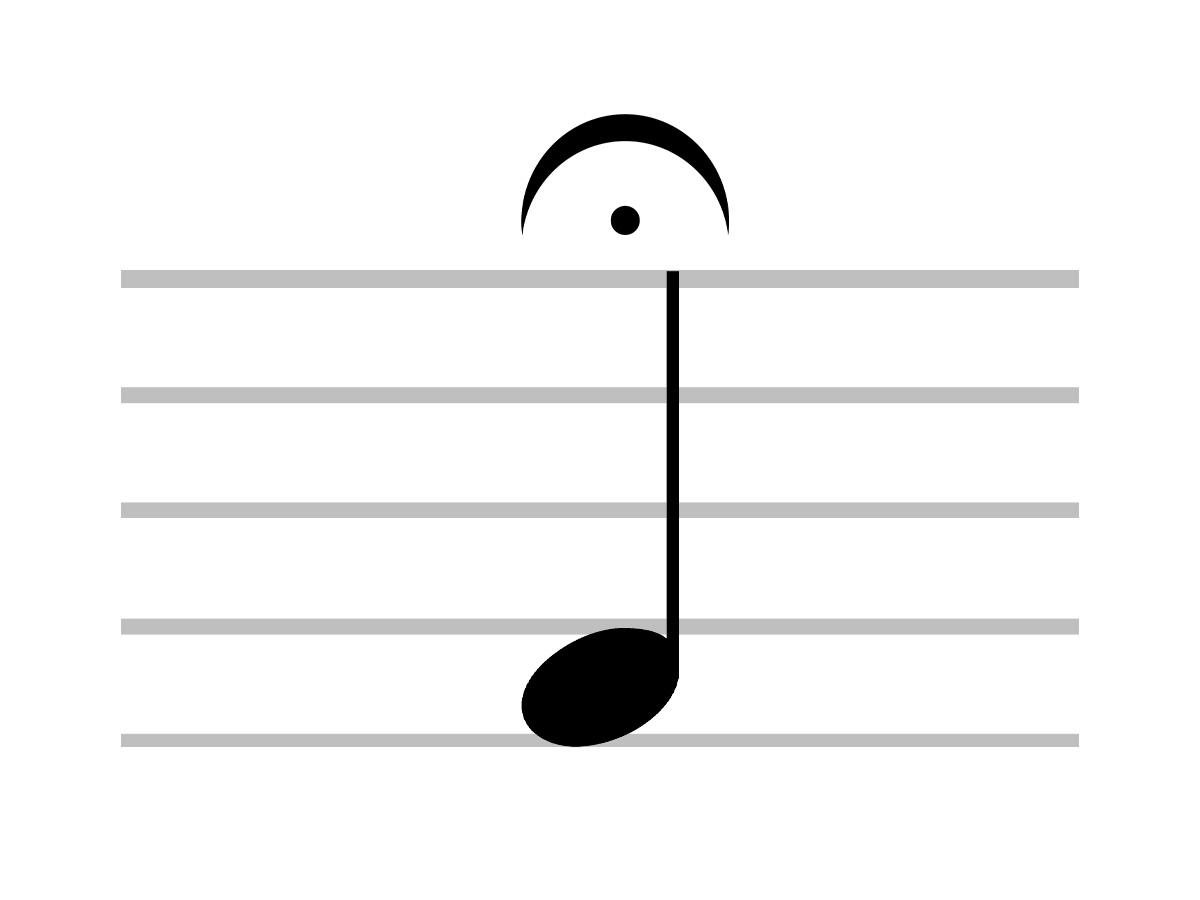

Fermata

A fermata instructs the performer to play a note, chord, or sustain a rest longer than its notated value. The duration of a fermata is entirely up to the performer or conductor.

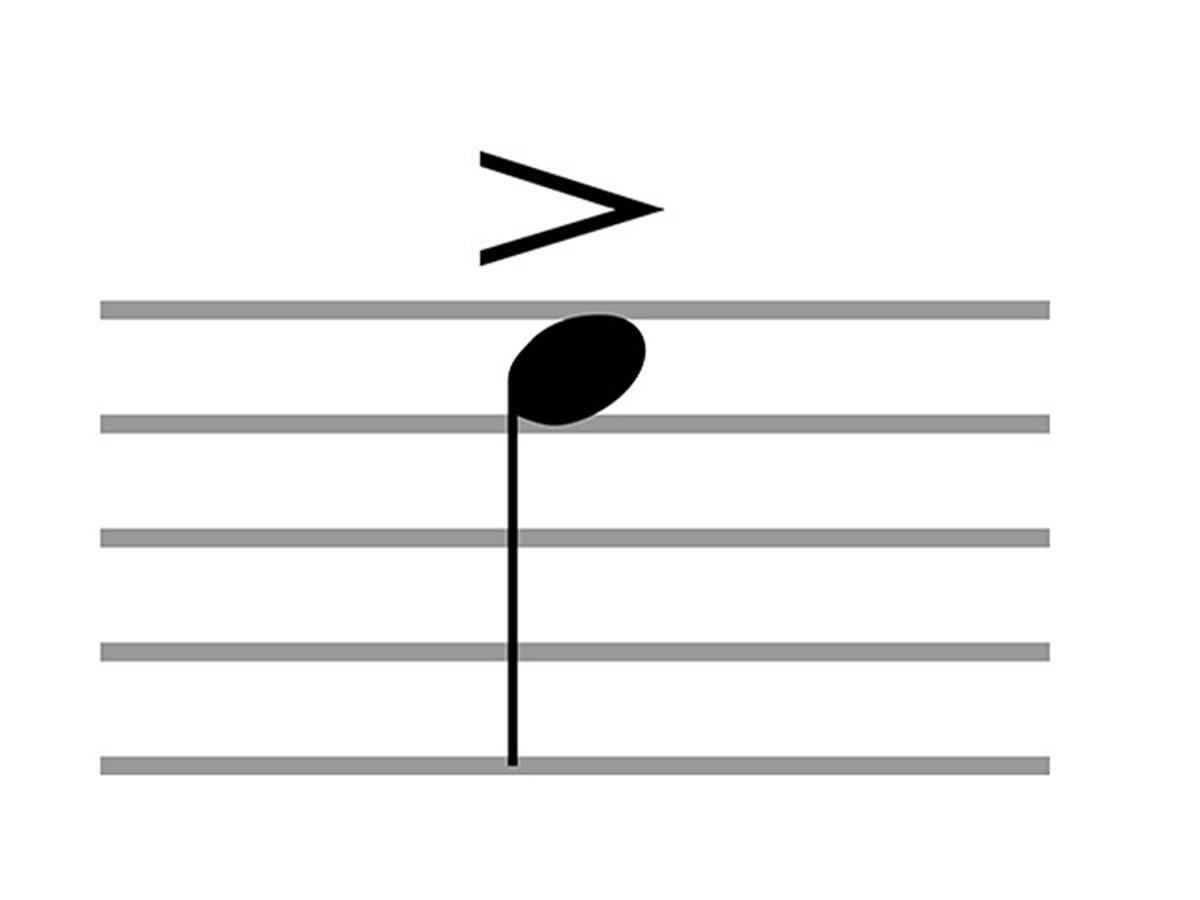

Accent

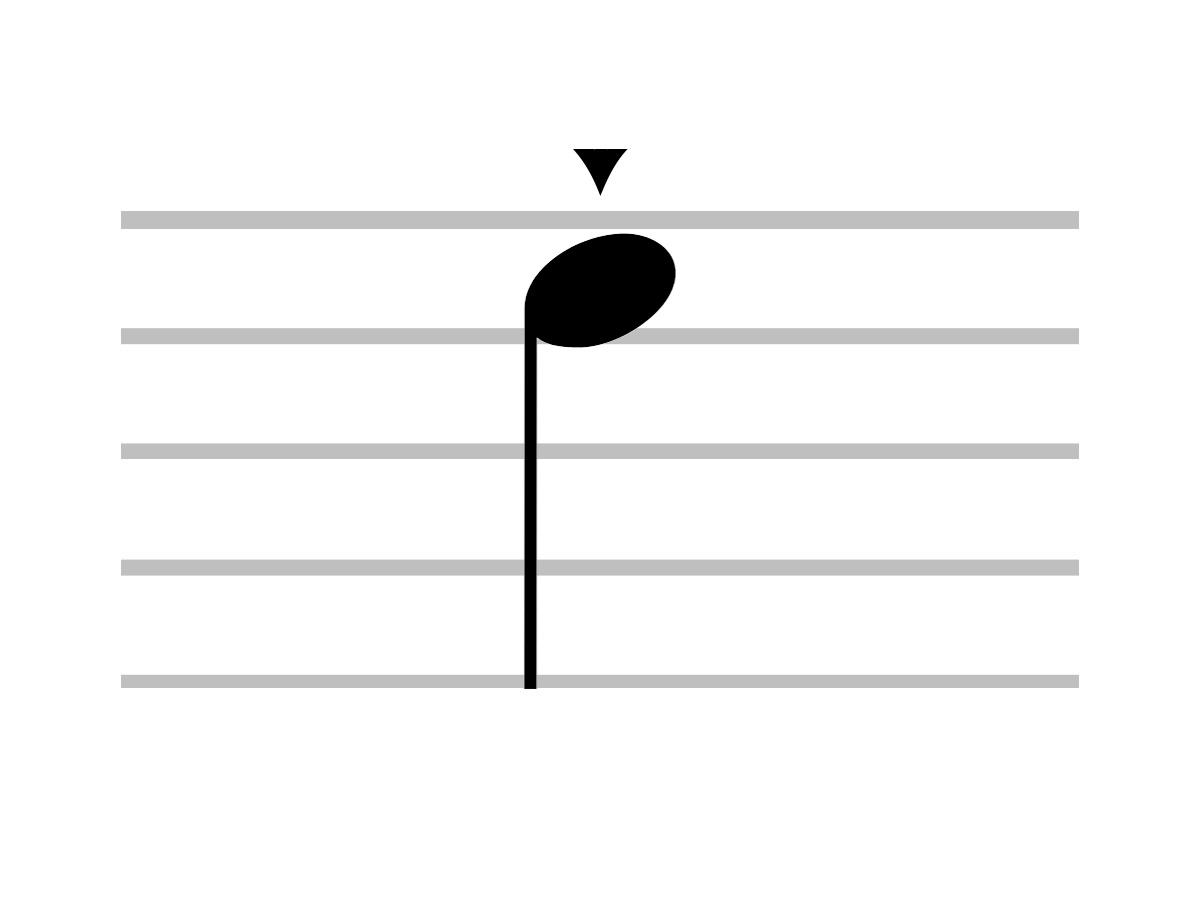

An accent indicates that the performer should play the note louder or with more emphasis than other notes. It can appear to modify notes with any duration – long or short.

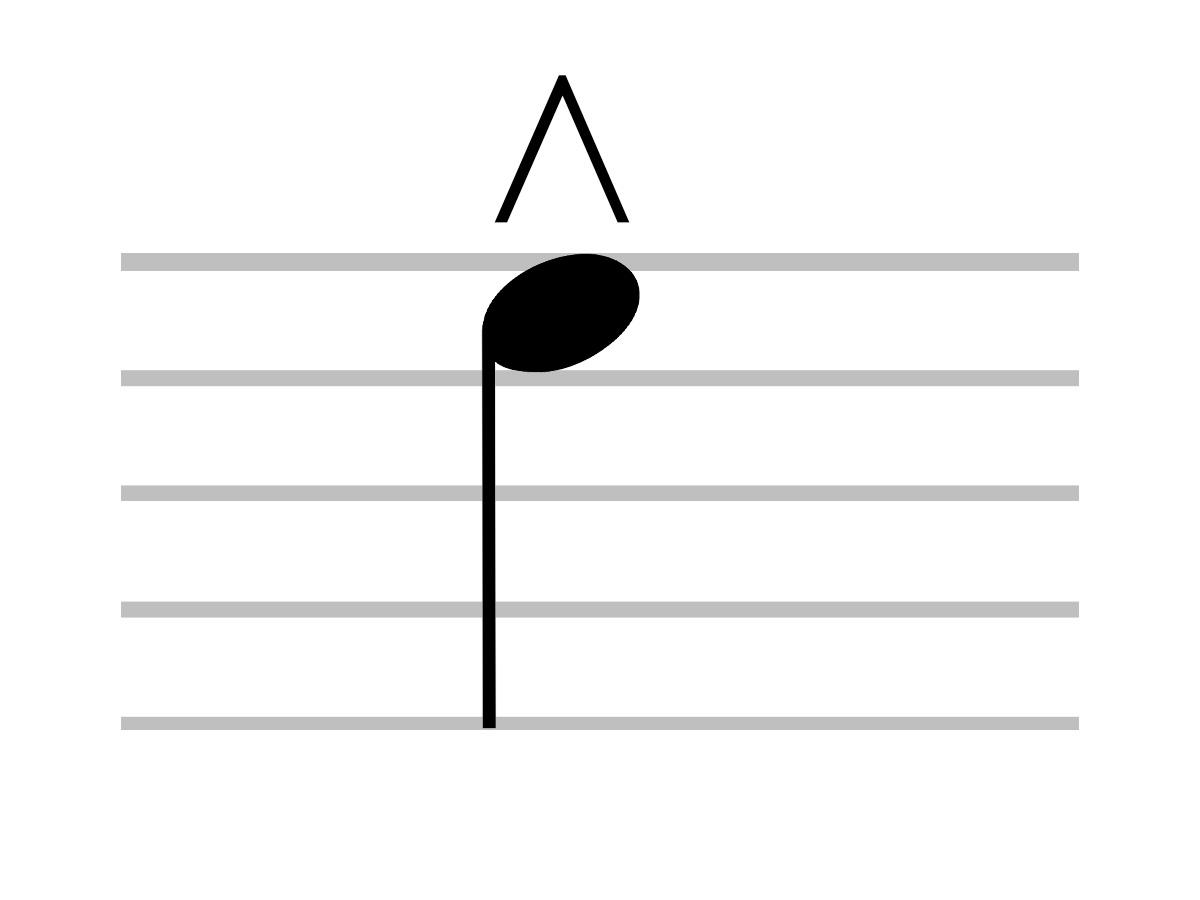

Marcato

A marcato is the extreme version of an accent. A note with a marcato marking means that the performer should play the note even louder or with harder emphasis than notes with a regular accent mark.

Ornaments

While articulation marks affect the way a note sounds (i.e. longer, shorter, stronger, etc.), ornaments are used to ‘decorate’ the note without having actual effect on the note itself to bring variety.

- Trill

- Upper mordent

- Lower mordent

- Gruppetto or turn

- Appoggiatura

- Acciaccatura

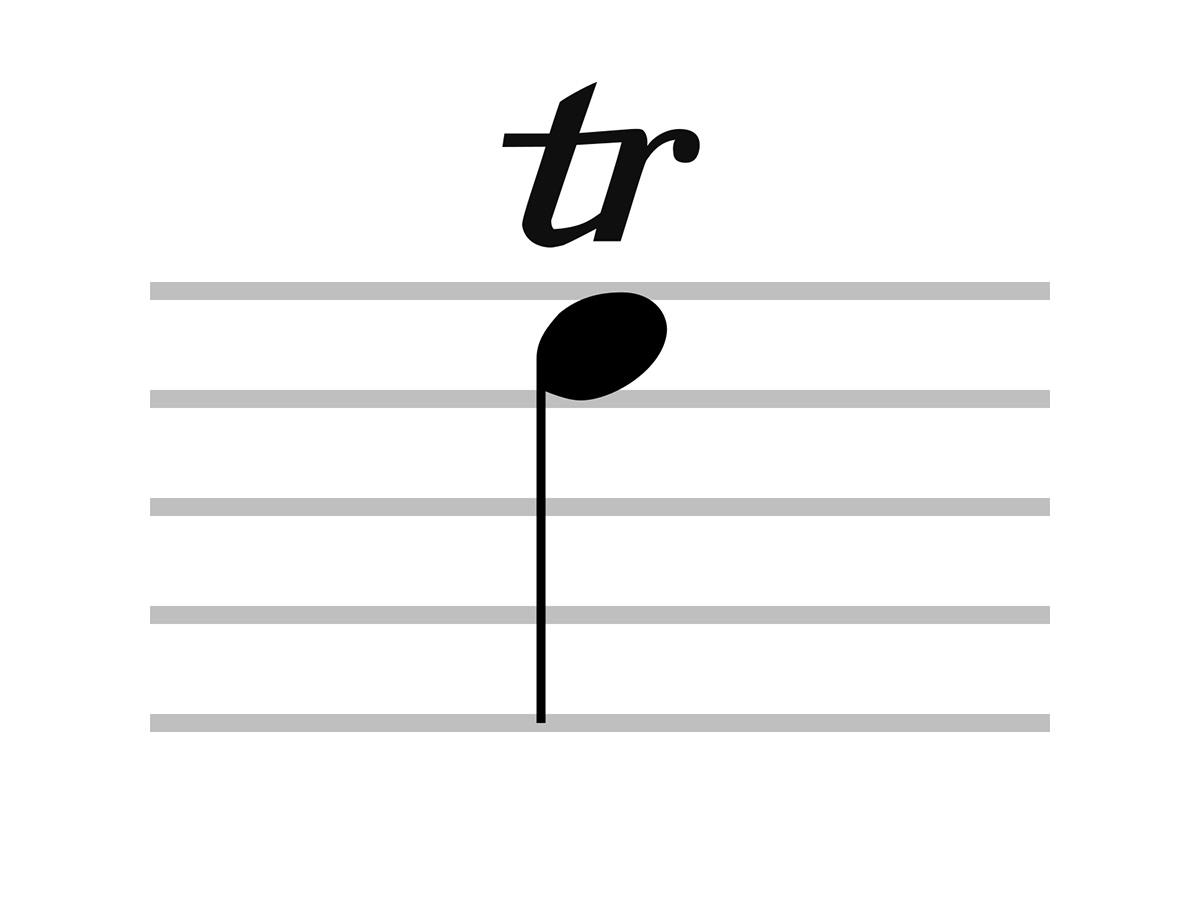

Trill

A trill marks a rapid alternation between a note and the following higher note within its duration as determined by the key signature. The rill ornament is also known as a “shake”.

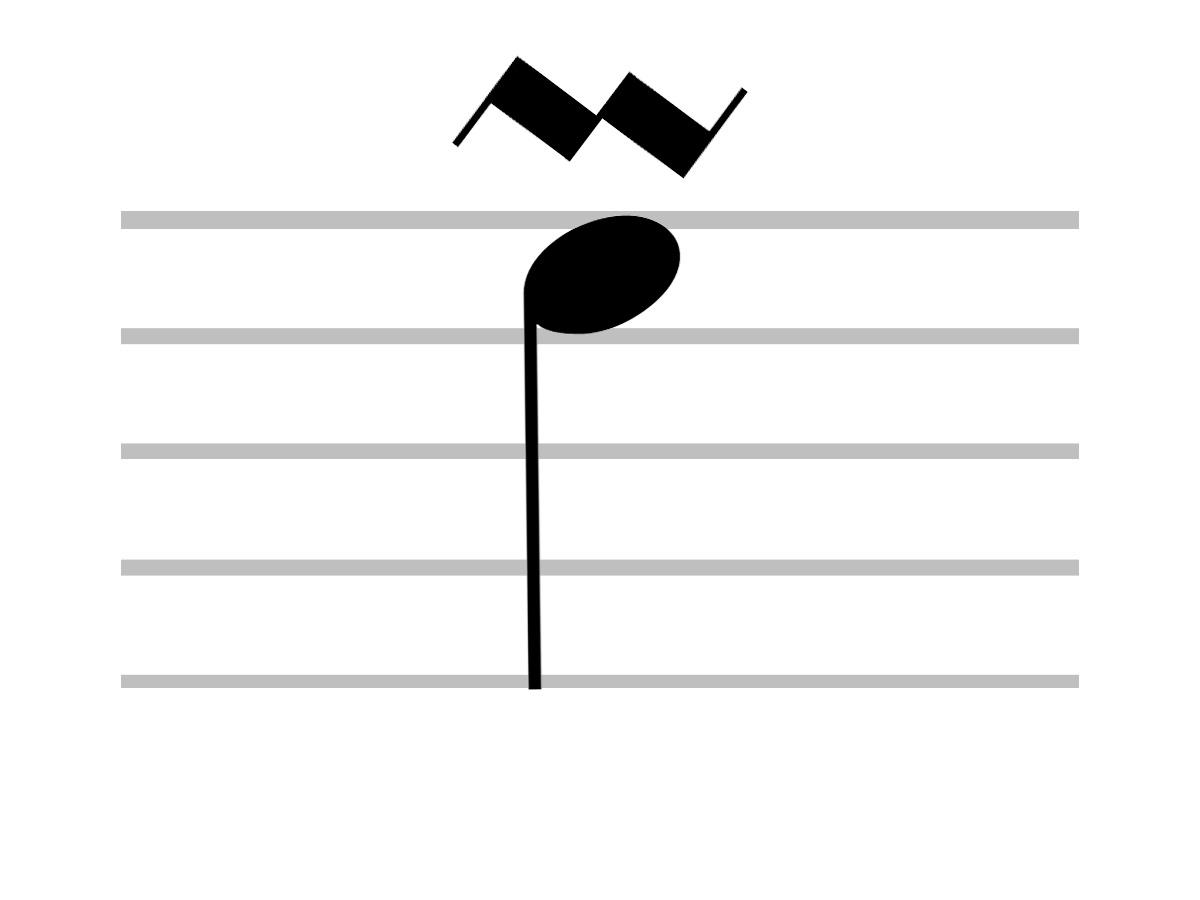

Upper mordent

Notes with an upper mordent tell the performer to play a single alternation between the primary note and the next higher note.

Both trill and upper mordent involve the primary note and the one above it. However, a trill is a rapid alternation that often has more than one or two repetitions. On the other hand, Mordent (upper or lower) only does the alternation once.

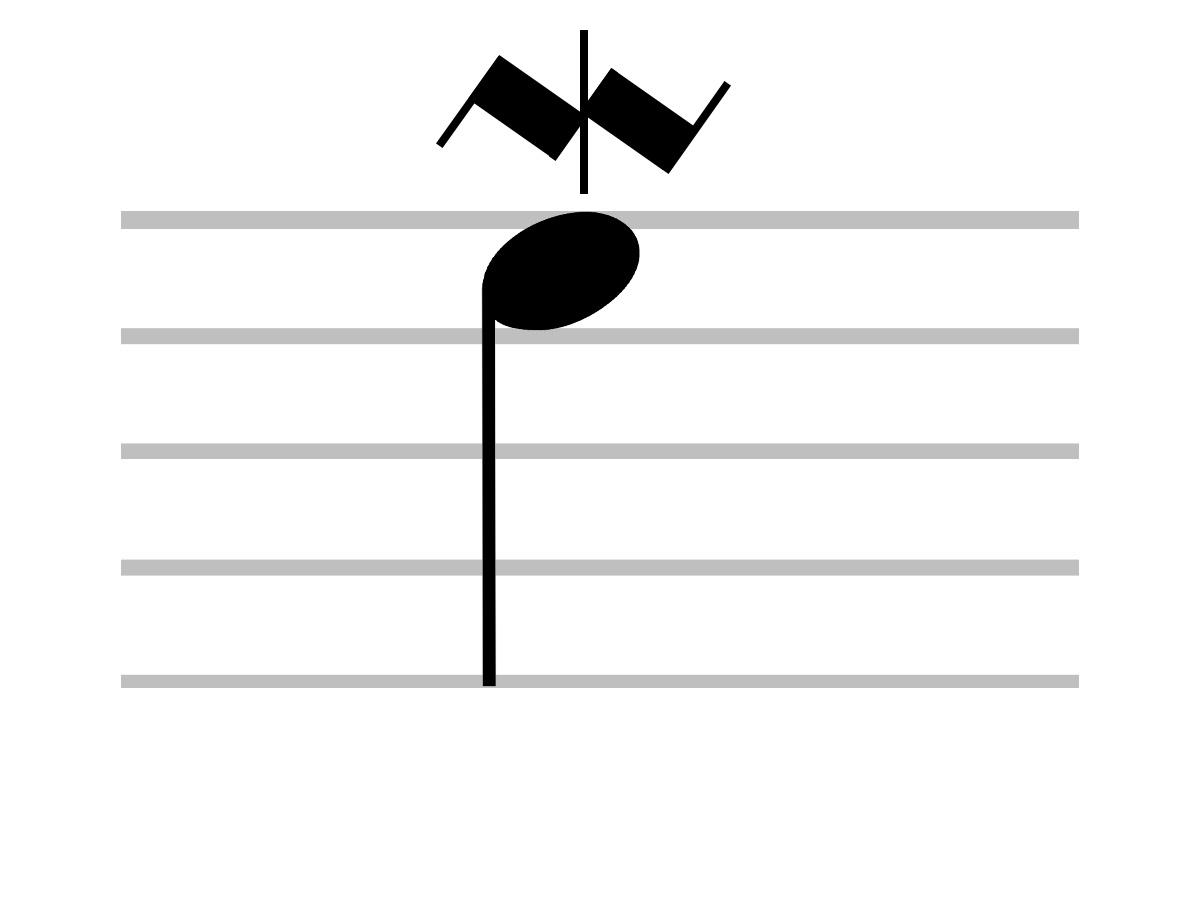

Lower mordent

Notes with a lower mordent tell the performer to play a single alternation between the primary note and the note below it.

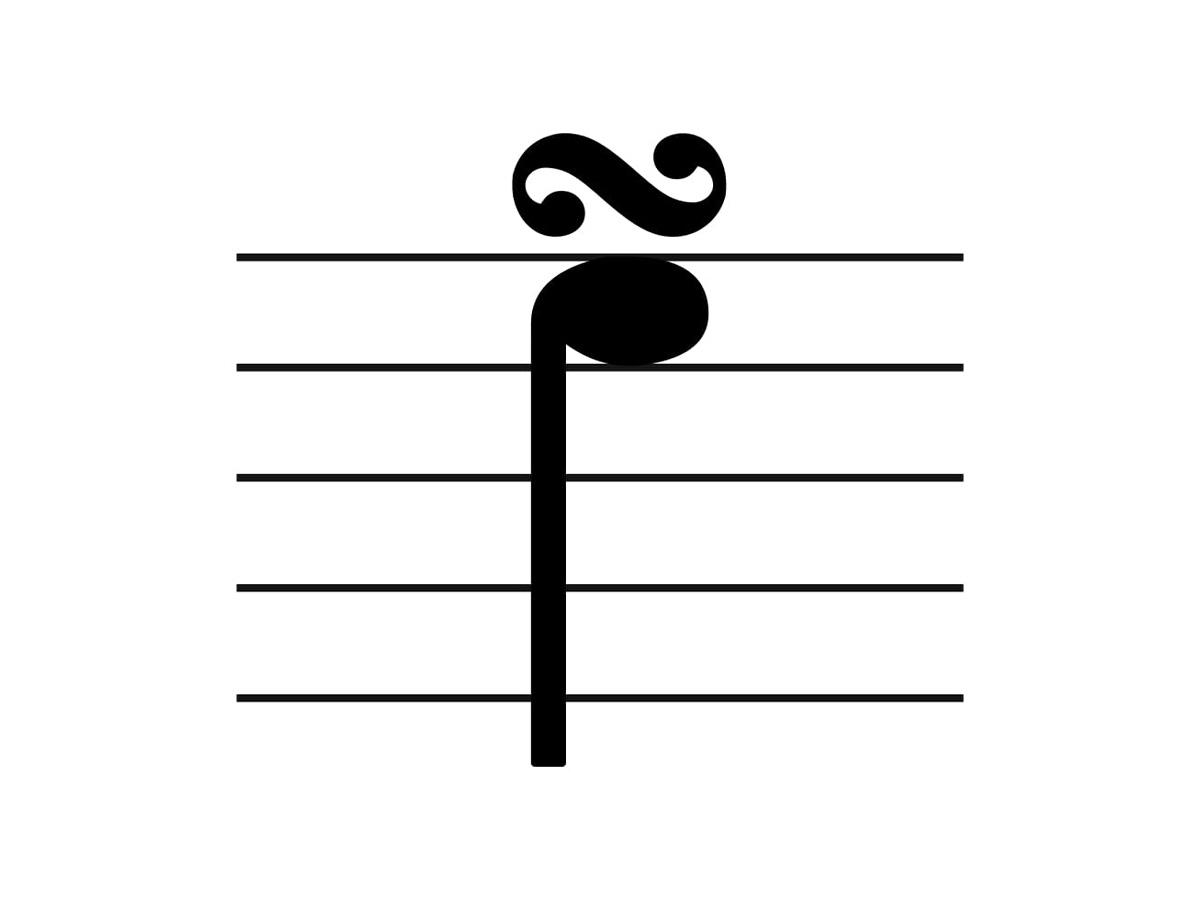

Gruppetto or turn

When a note has a gruppetto directly above it, the sequence starts with the upper auxiliary note, primary note, lower auxiliary note, and back to the primary note.

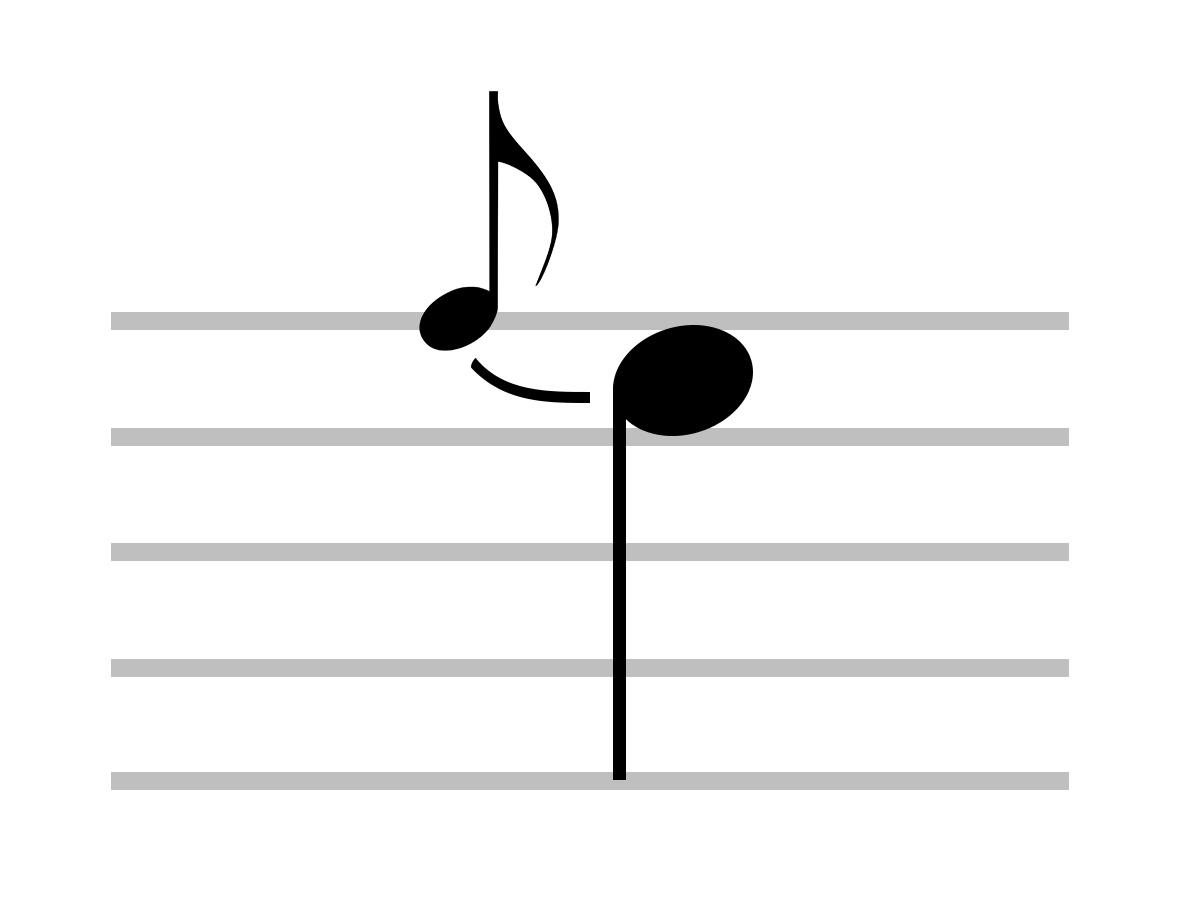

Appoggiatura

An appoggiatura is played by adding an ornamental note that temporarily displaces the chord note before going back to the chord note. It often appears in the first or third beats of the bar in 4/4 time.

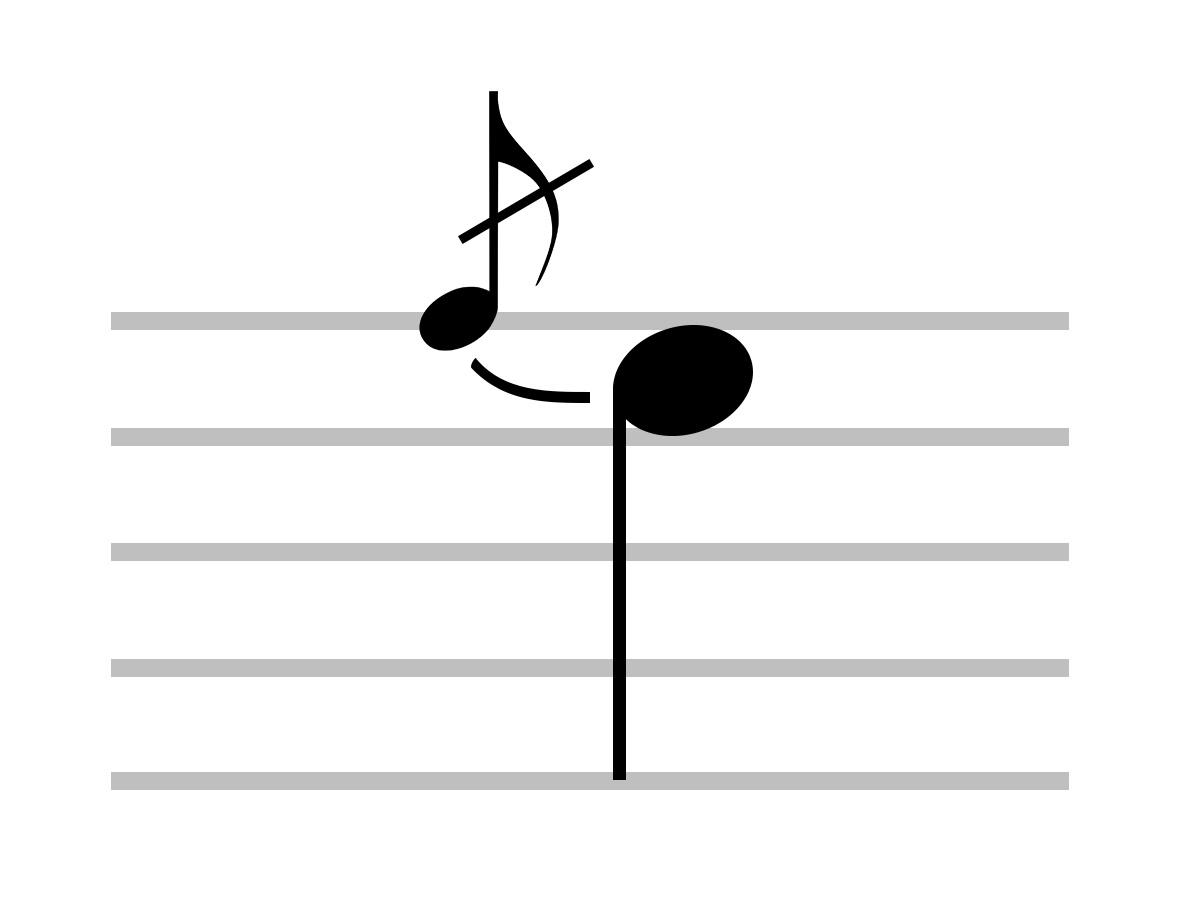

Acciaccatura

A musical ornament that modifies arpeggiated chords to be played with a chord tone a one or half tone below and immediately released.

Octave Signs

Octave signs indicate that multiple notes should be played an octave (or two octaves) higher or lower depending on the mark used. An 8va means one octave higher, and 8vb means one octave lower. When two-octave changes are involved, the mark turns into 15ma or 15mb.

Ottava

An ottava is drawn above or below the staff to instruct the performer to play the passage one octave higher or lower. There are two types of this sign: ottava alta (higher) or ottava bassa (lower).

Quindicesima

The quindicesima sign is drawn above or below the staff to instruct the performer to play the passage two octaves higher or lower.

Repetition and Codas

The repetition and codas help the performers understand the piece’s flow better by marking sections that they need to play and repeat.

- Tremolo

- Repeat signs

- Simile marks

- Volta brackets

- Da capo

- Segno

- Dal Segno

- Coda

Tremolo

A tremolo sign means that the note(s) should be played rapidly and repeatedly. If it appears between two notes, they should be played alternatively in a similar manner.

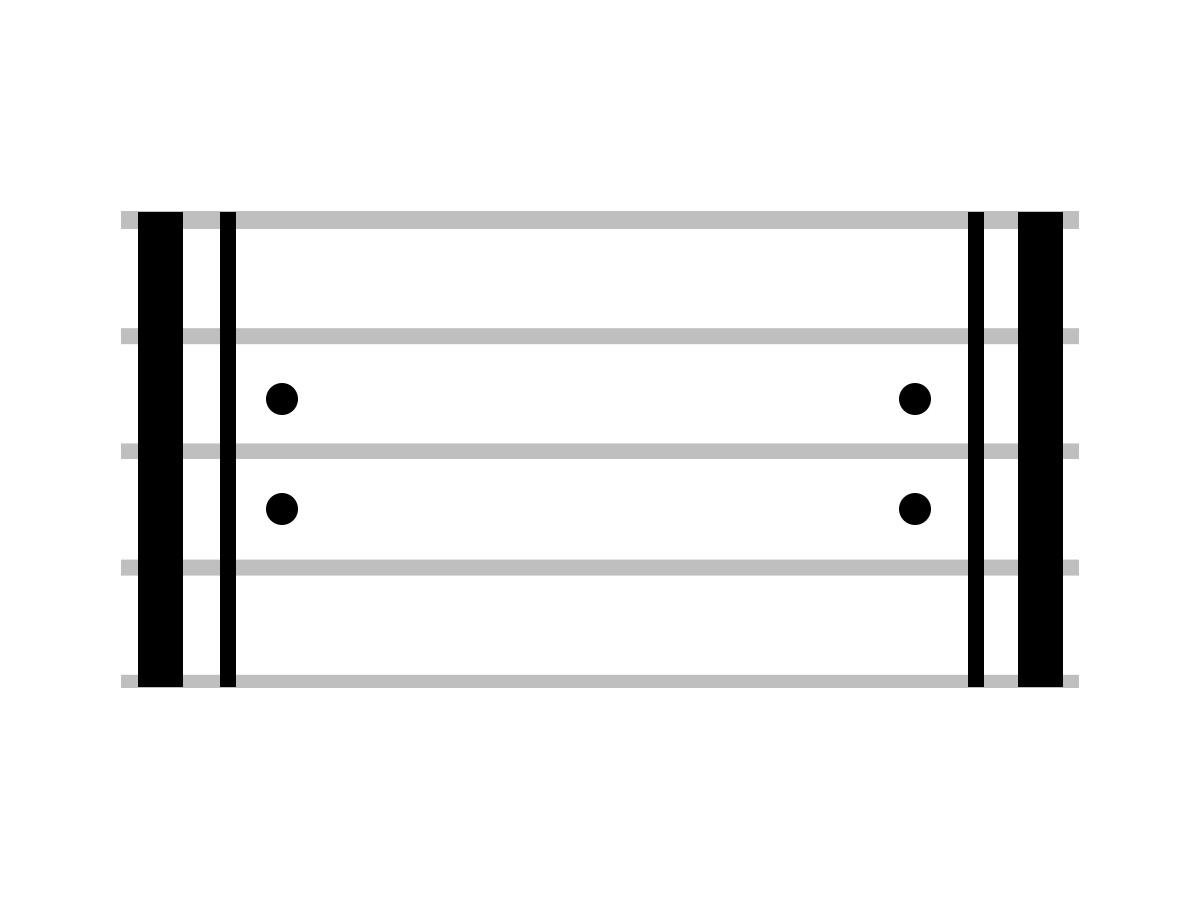

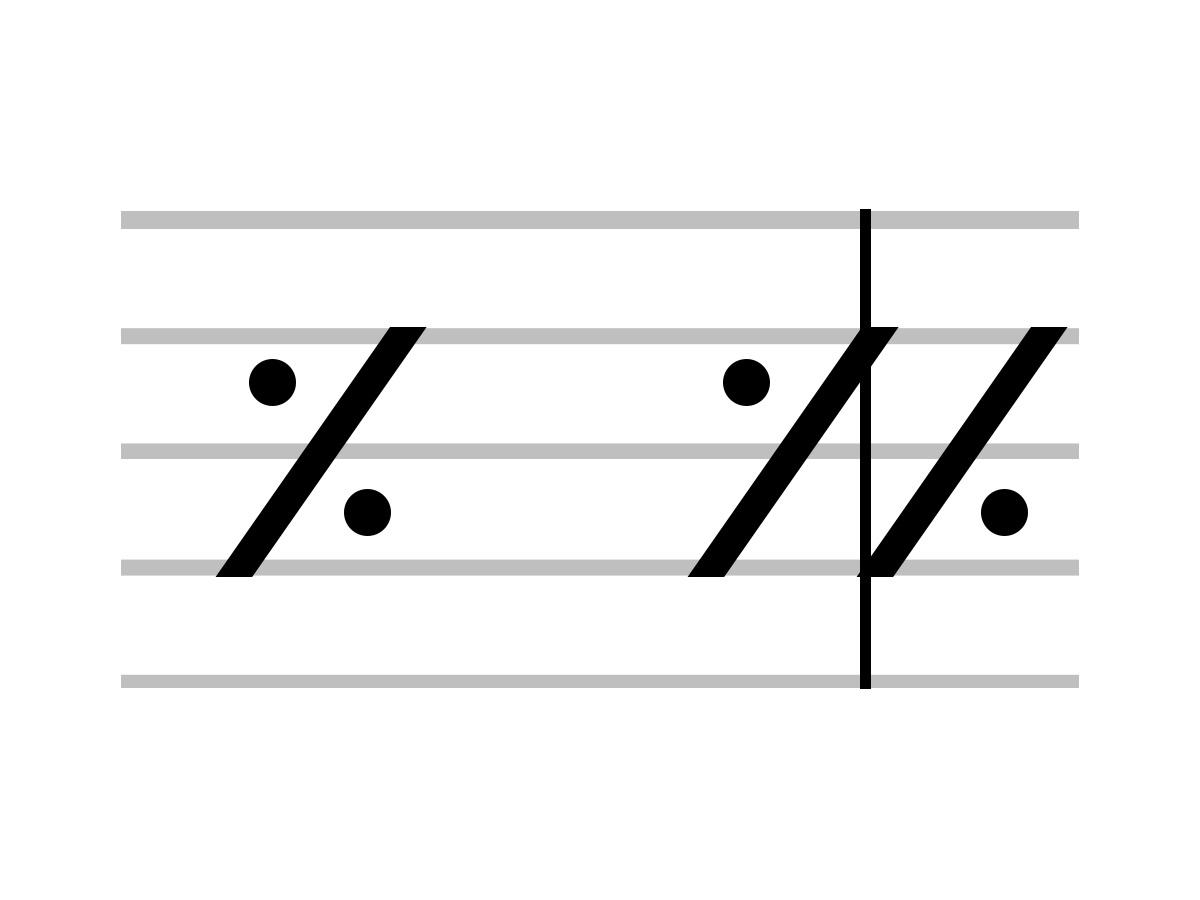

Repeat signs

Repeat signs are used to enclose a passage that needs to be played one more time. The right repeat sign indicates the point where performers need to start repeating. The left repeat sign marks where the repetition starts.

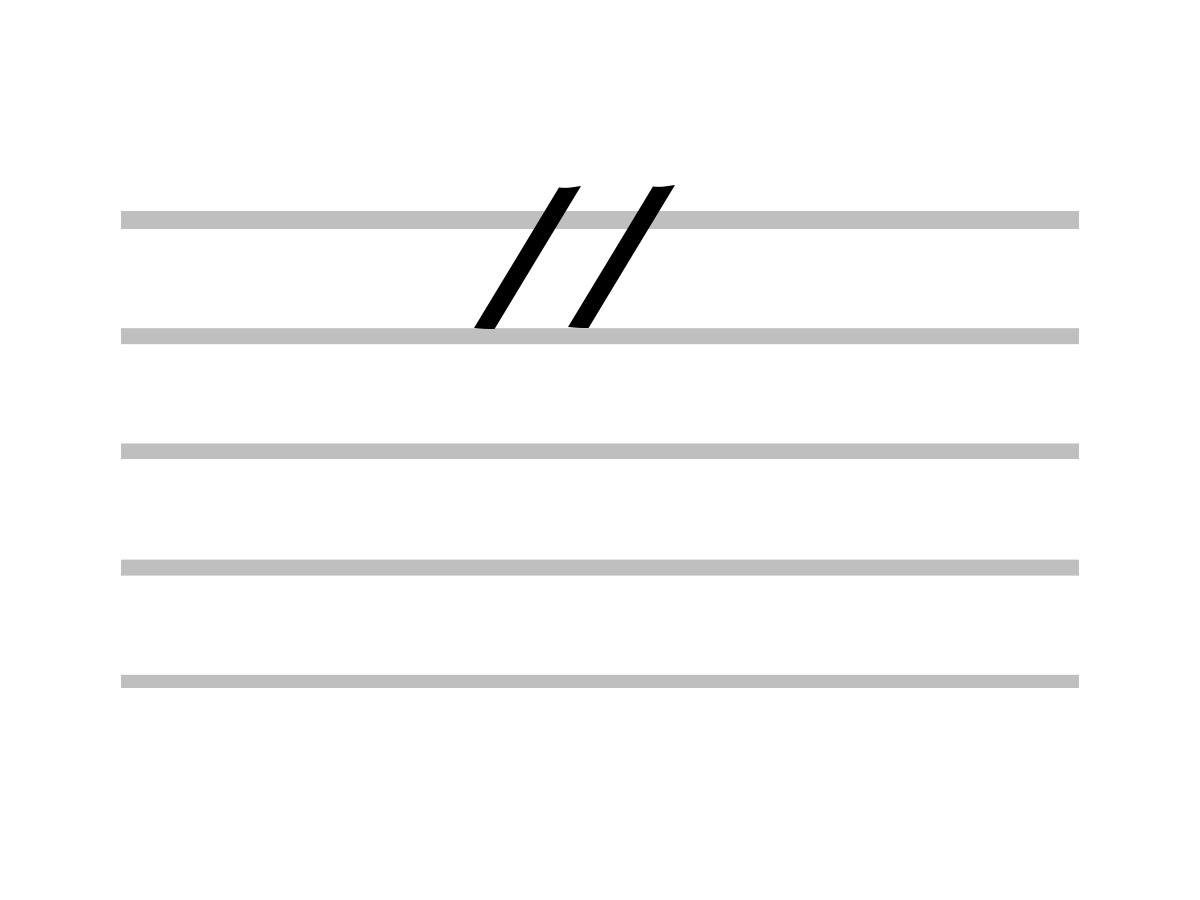

Simile marks

Tells the performer that they must repeat the previous group of bars. A singular diagonal line means to repeat the previous bar; a double diagonal line means to repeat the previous two bars.

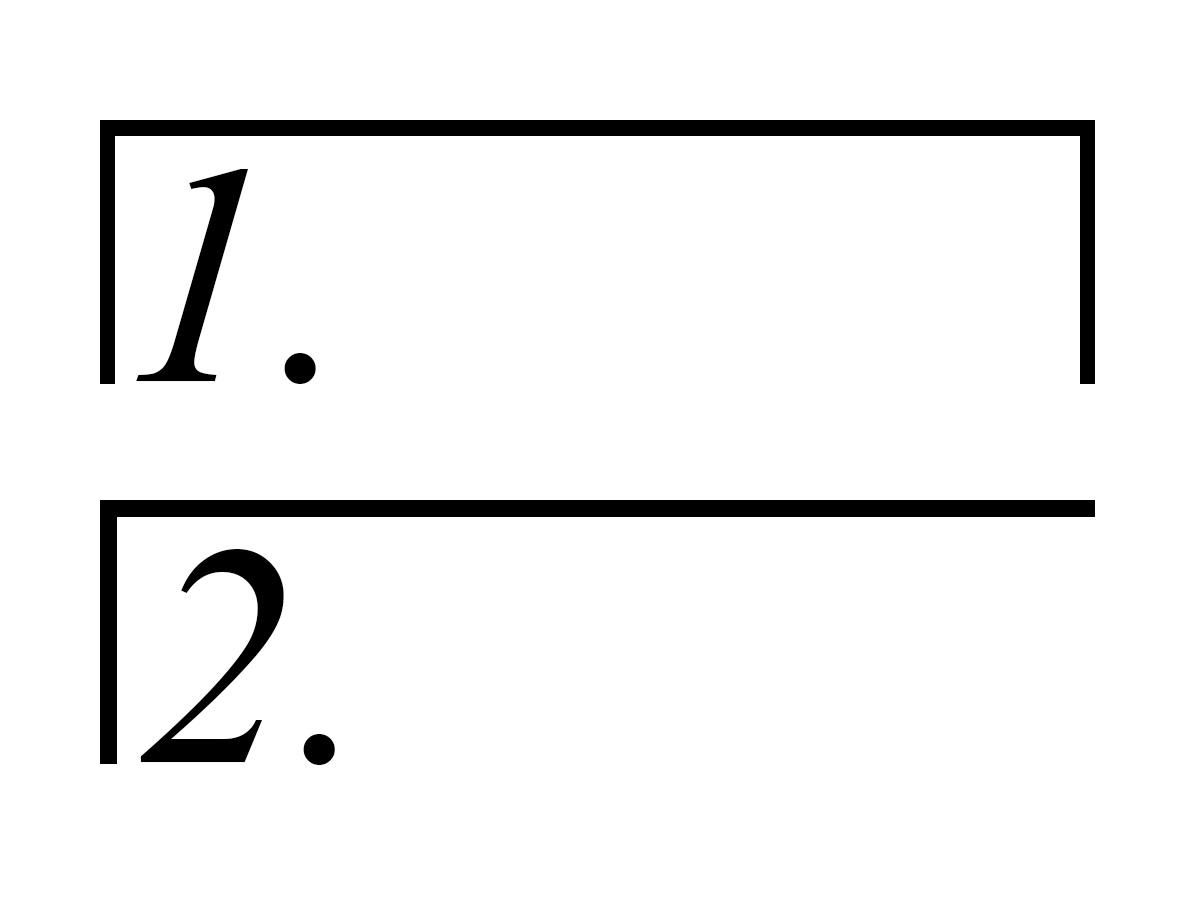

Volta brackets

The volta brackets tell the performer to play the repeated passage with different endings on each iteration. There are typically only two endings, but the usage of 3rd ending or more isn’t unknown.

Da capo

Da capo tells the performer to go back to the beginning of the music and play it over. There is usually either al fine or al coda following this mark – resulting in a D.C. al fine or a D.C. al coda.

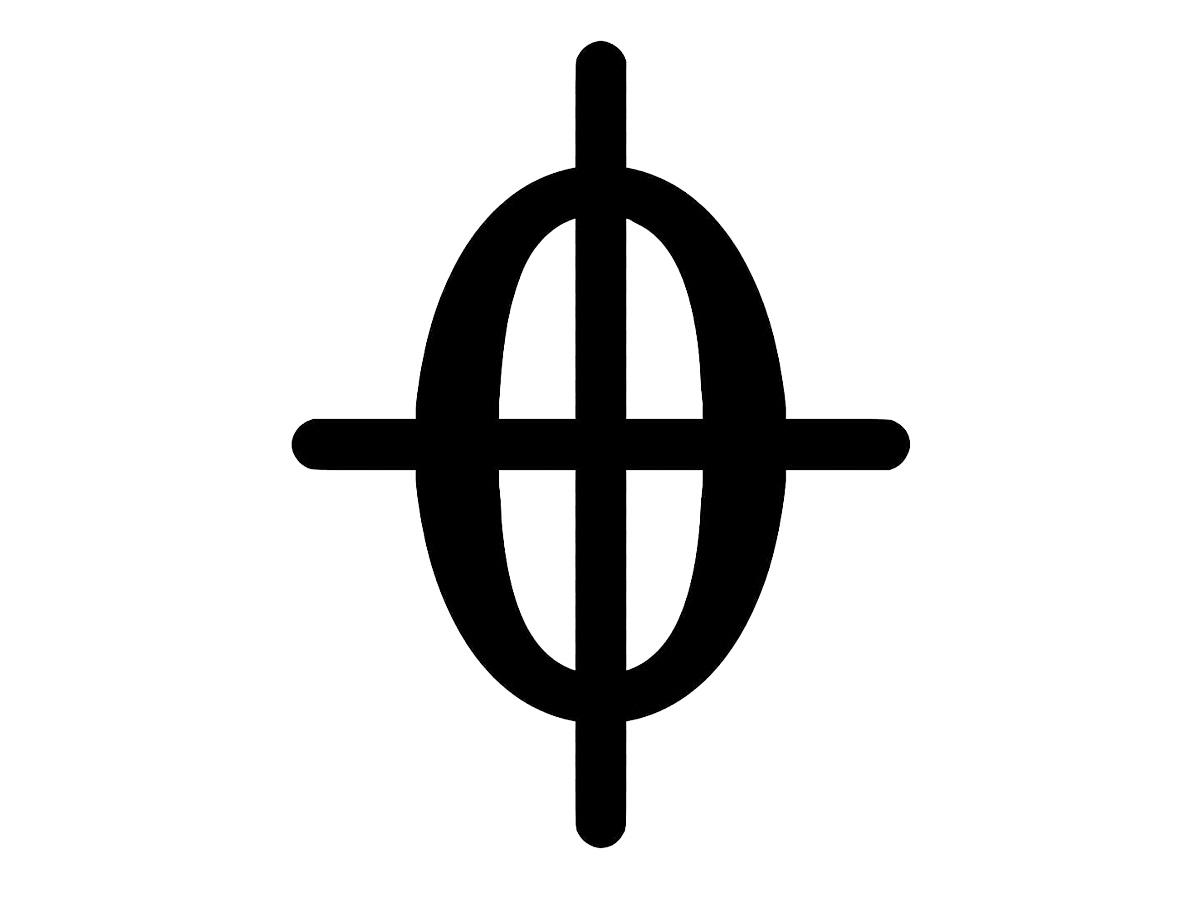

Segno

A segno is a symbol used to put a ‘mark’ on a specific passage or note. This works complementary with Dal segno.

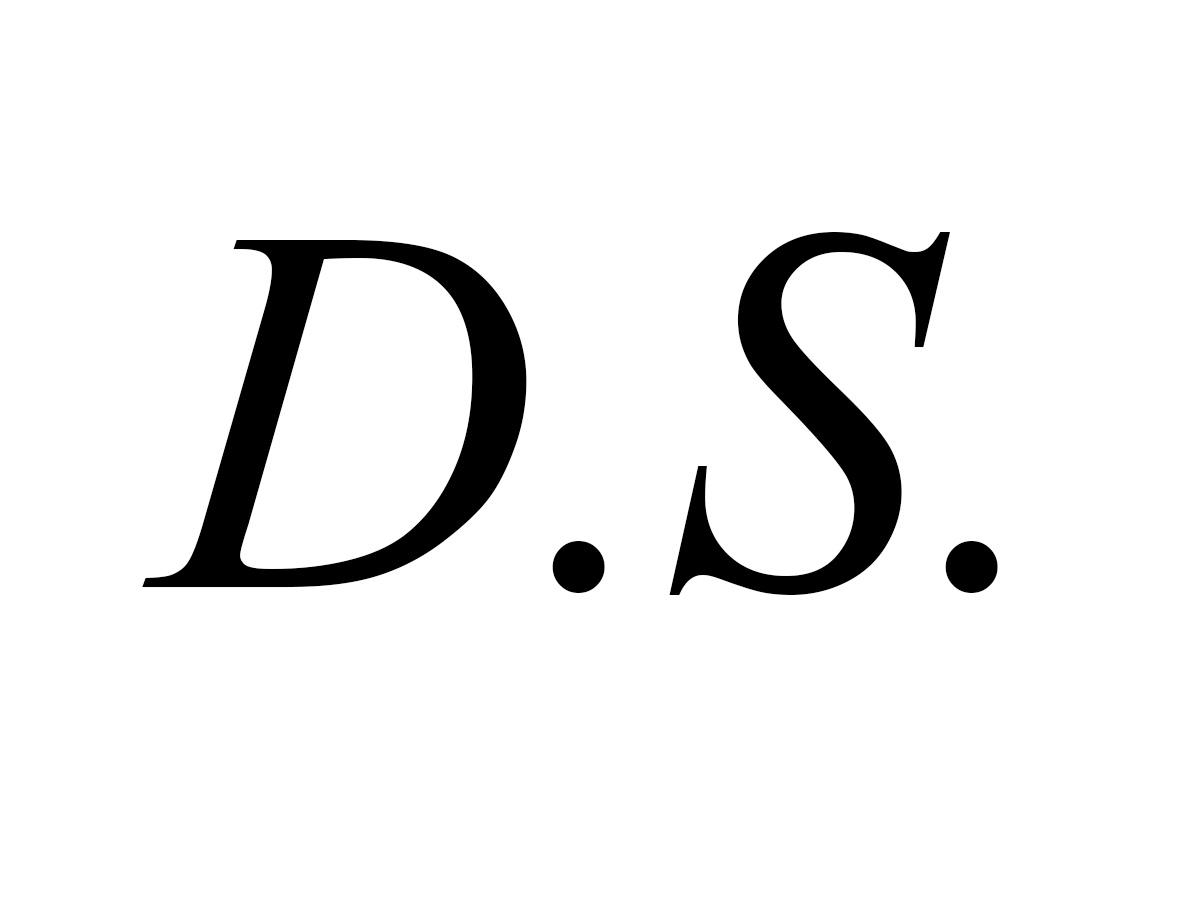

Dal segno

Dal segno tells the performer to play the music over starting from the nearest segno. Similar to da capo, there’s usually al fine or al coda following dal segno – resulting in a D.S. al fine or D.S. al coda.

Coda

A coda indicates a jump to the last passage of the music that has the same sign. This sign is only used after the performer has played through D.S. al coda or D.C. al coda.

Instrument-Based Symbols

Because each instrument is played differently, there are some symbols that exclusively work for specific instruments. Here are some of them:

- For bowed string instruments

- Guitar symbols

- Piano pedal marks

- Drum notation

For bowed string instruments

These notations are specifically used in bowed-string instruments like violin, cello, and lyra. While some of these symbols are also applicable on several other instruments, they aren’t as universal as other music symbols.

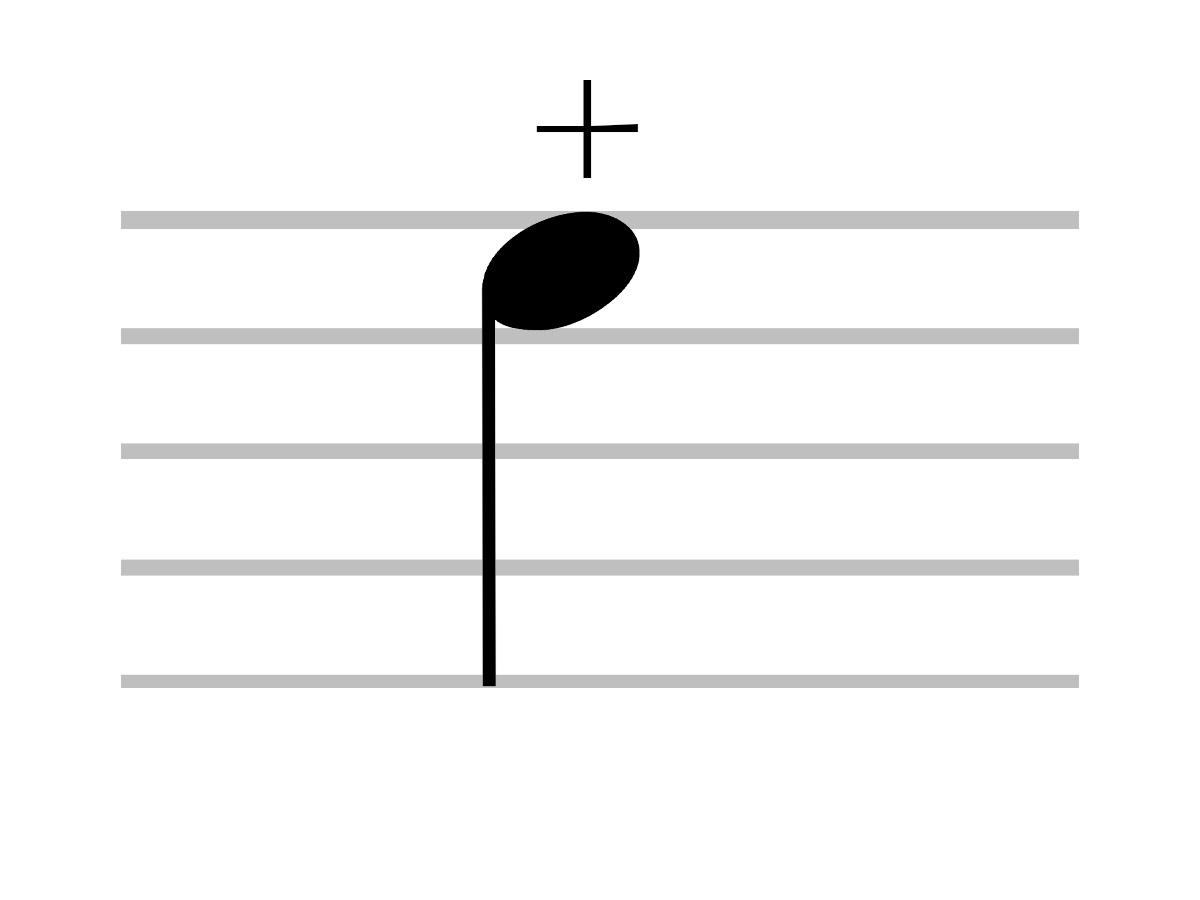

Left-hand pizzicato or stopped note

A left-hand pizzicato is a note played by plucking the string with the left hand rather than the bow on a stringed instrument.

Snap pizzicato

A snap pizzicato on a stringed instrument is a note played by pulling the string away from the instrument frame and letting it go – thus, making the ‘snap.’ It’s also known as Bartók pizzicato.

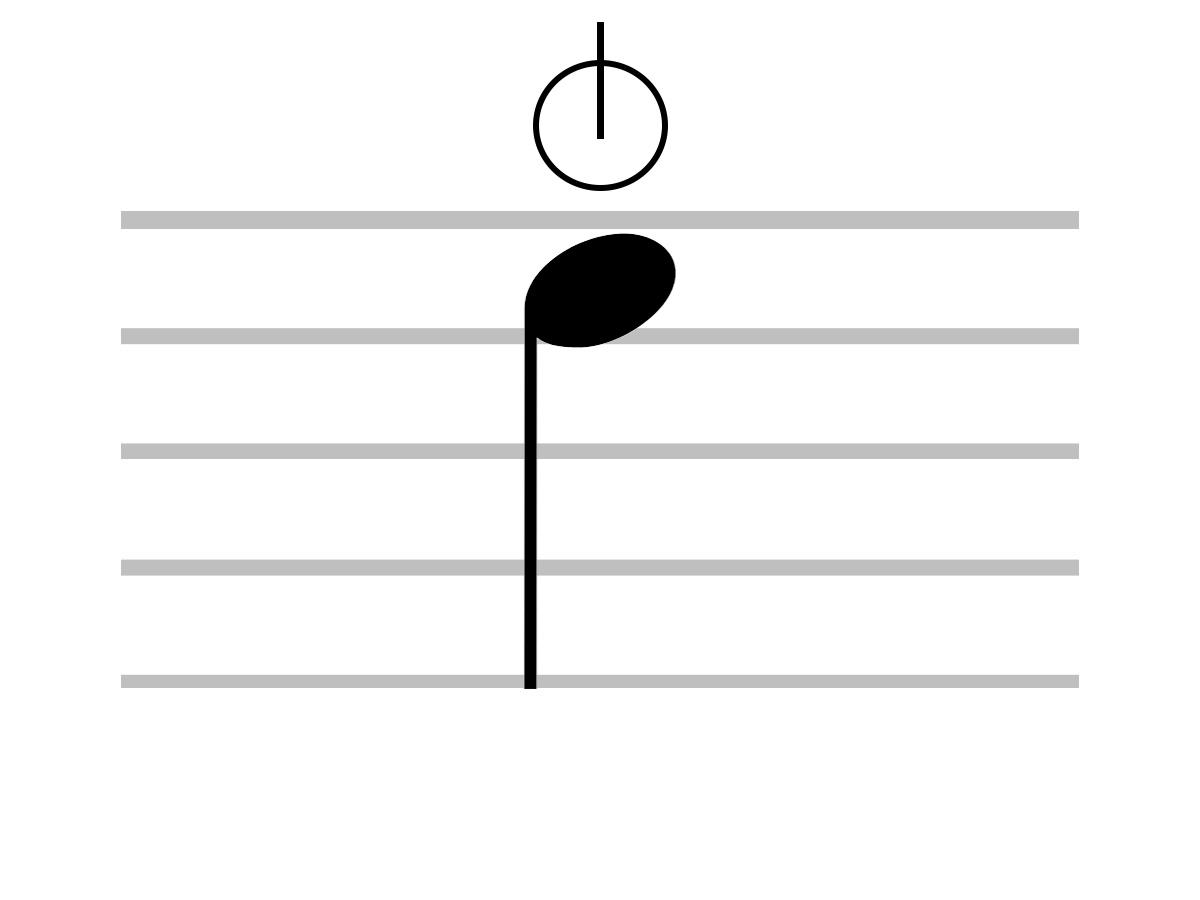

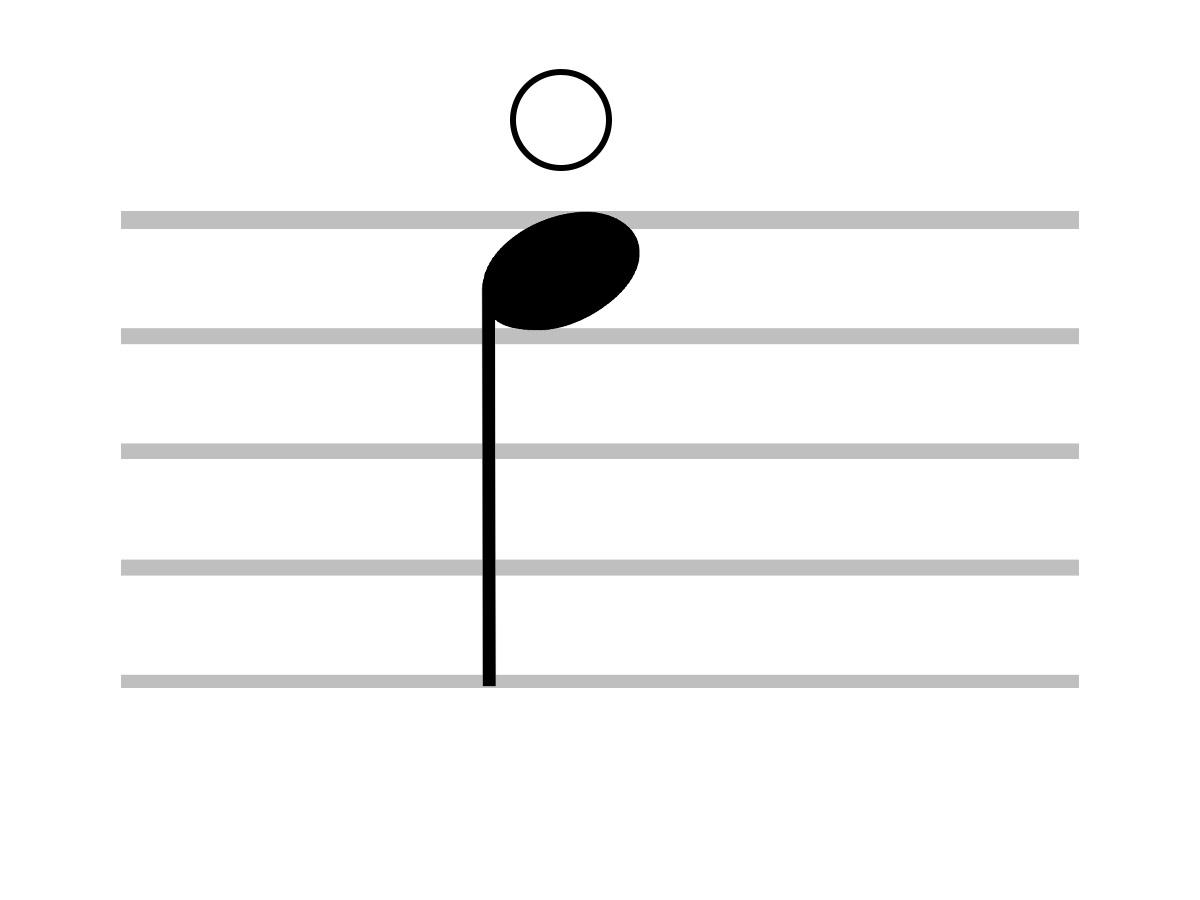

Natural harmonic or open note

A natural harmonic (also known as flageolet) is played by applying slight pressure with the finger on the various nodes of the open strings.

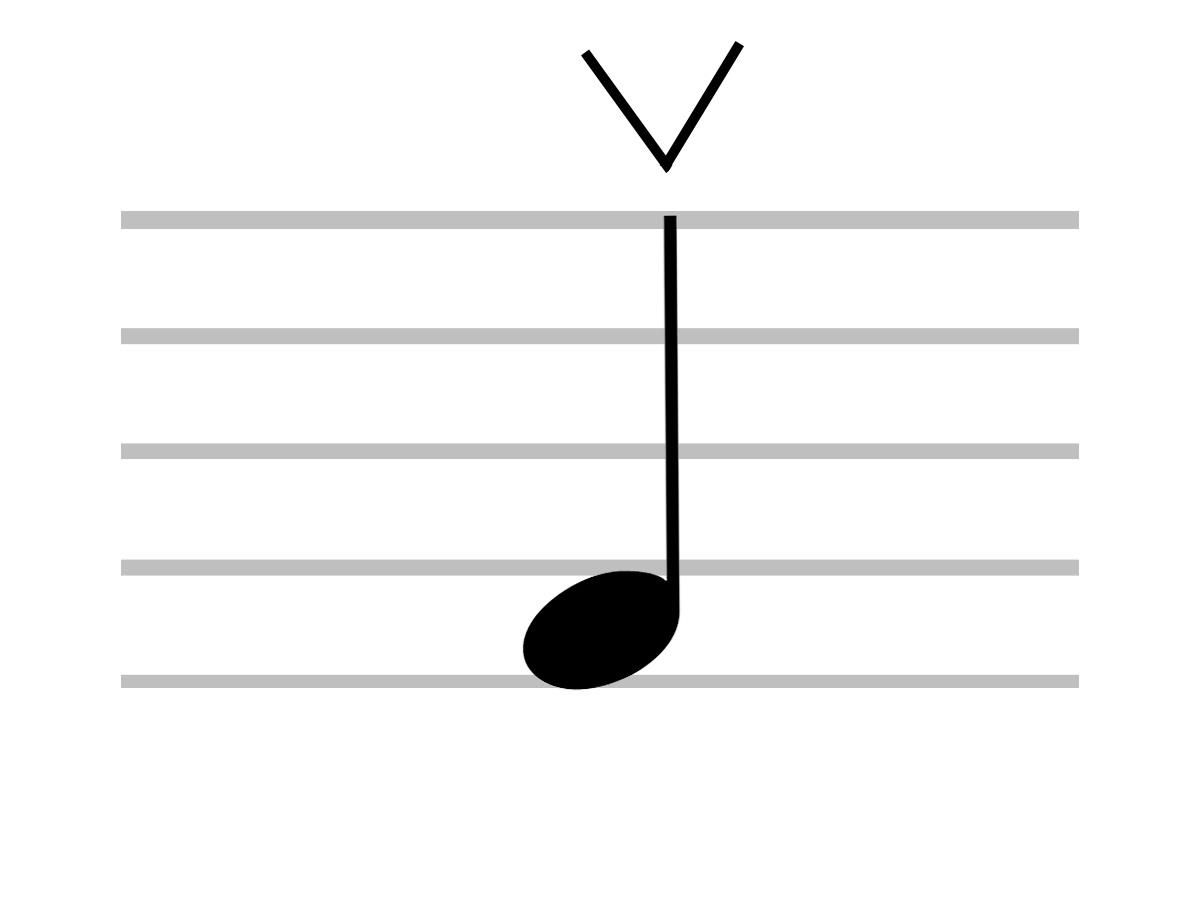

Up bow or Sull’arco

A Sull’arco note means that the note should be played while dragging the bow upward.

Down bow or Giù arco

Inversely, a Giu arco note means that the note should be played while dragging the bow downward.

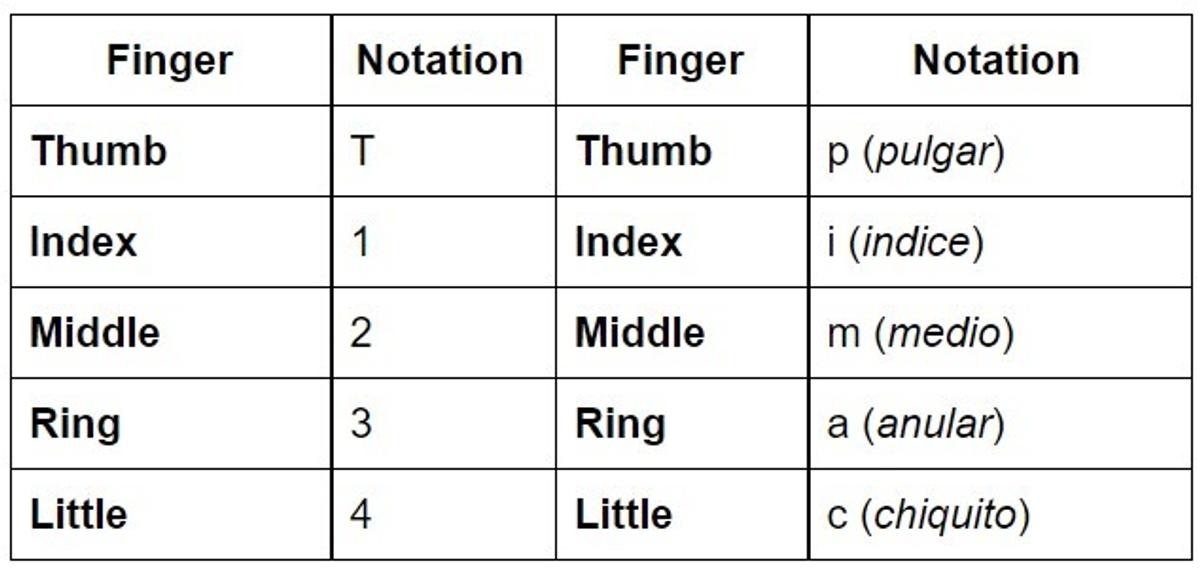

Guitar symbols

In fingerstyle (or fingerpicking) guitar notation, each finger on the left hand (which stops the strings) is indicated with a number.

The right-hand fingers (that pluck the strings) are notated with the first letter of their Spanish name.

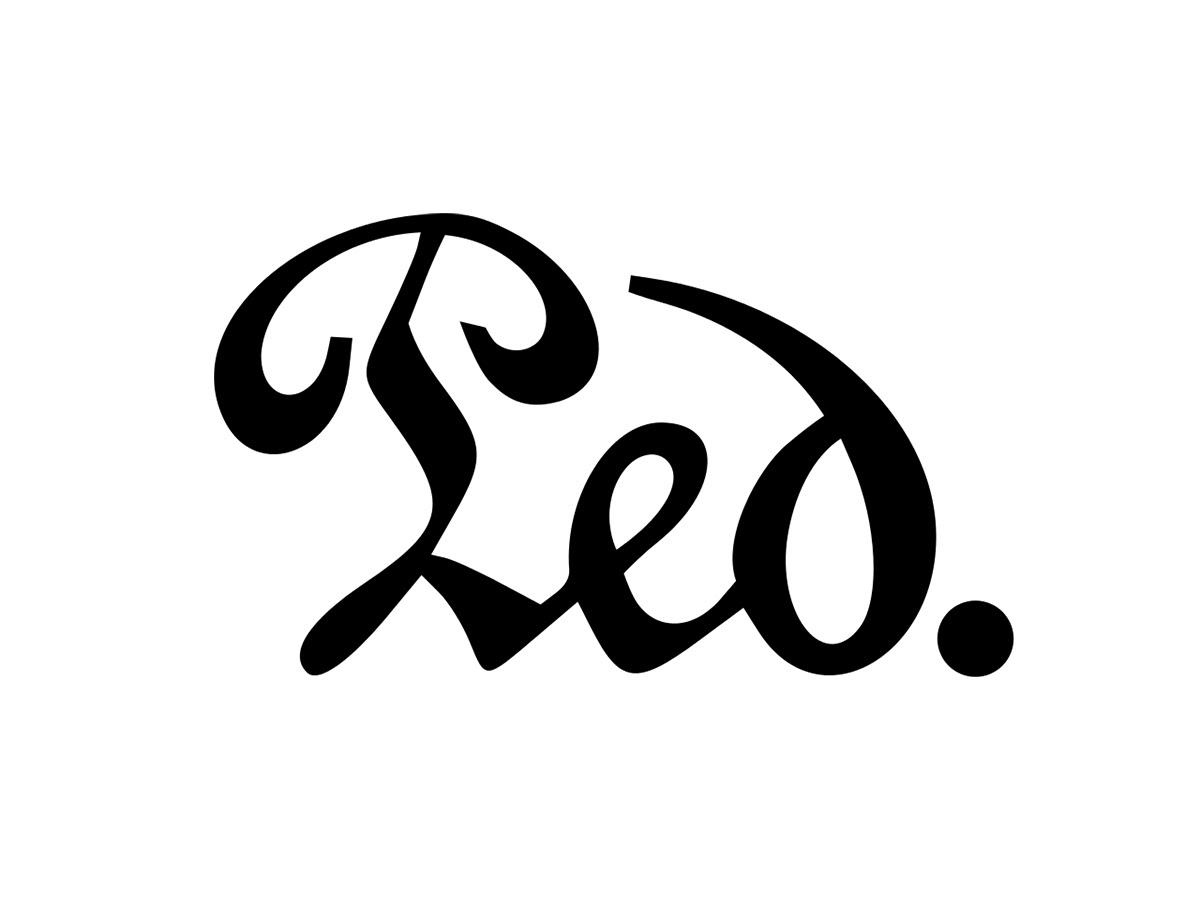

Piano pedal marks

Pedal marks often appear in musical instruments with sustain pedals, including the piano, vibraphone, and chimes. Sustain pedals allow the notes to play longer by pulling the dampers away from the strings, allowing them to vibrate more freely.

Engage pedal

The engage pedal symbol tells the performer to put the sustain pedal down.

Release pedal

The release pedal symbol tells the player to let go of the sustain pedal.

Variable pedal mark

The variable pedal mark indicates the precise usage of the sustain pedal. Lower lines tell the performer to play the notes above it with the pedal pressed down. The ∧ symbol means the performer to release the pedal momentarily.

Con sordino, una corda

Tells the performer to press on the soft pedal (piano) or apply the mute (other instruments).

Senza sordino, tre corde

Tells the performer to let go of the soft pedal (piano) or remove the mute (other instruments).

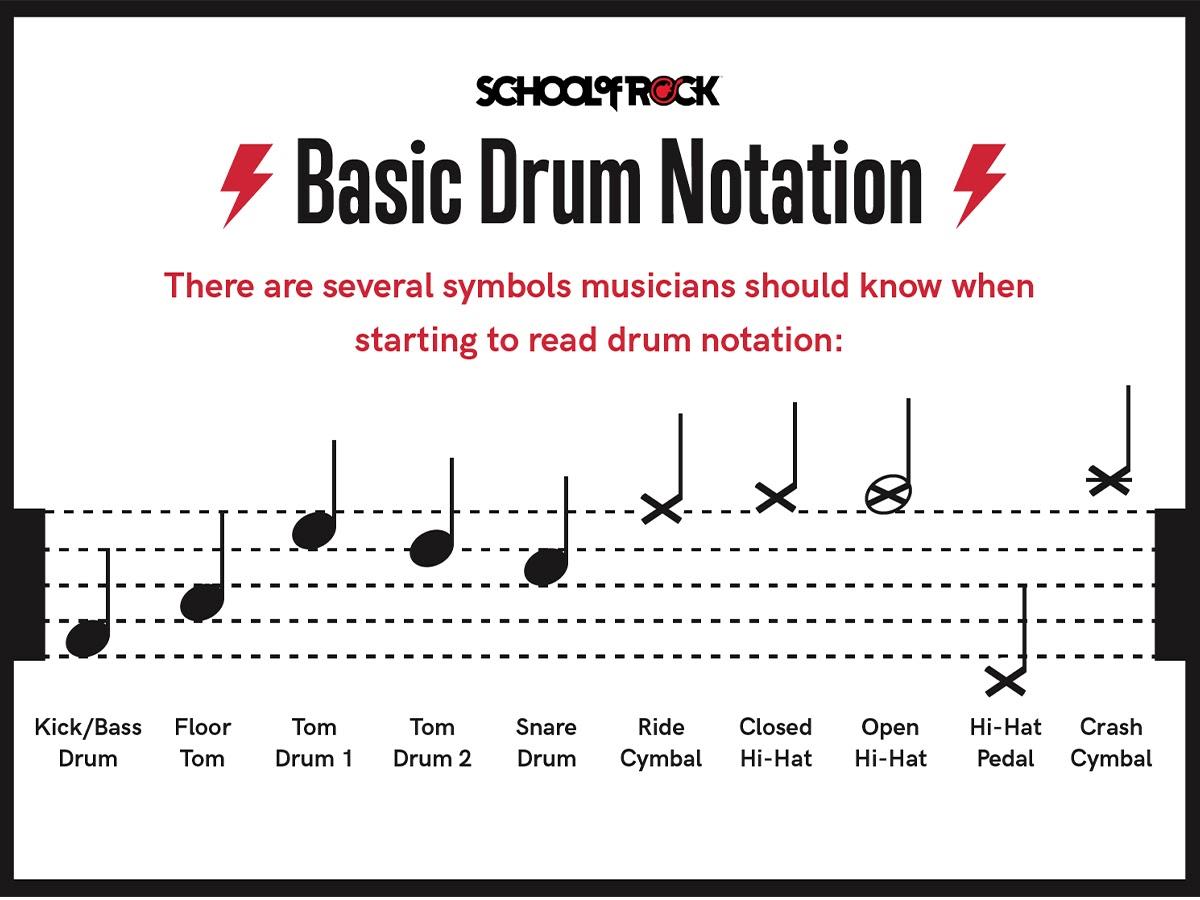

Drum notation

Drum notation is a way to write down sheet music specifically for percussion instruments – basically a language for drums.

Percussion instruments, including drum sets, use the percussion clef on the musical staff. In a drum notation, the different symbols represent different parts of the drum set.

Conclusion

Learning musical symbols is a challenging task, but it’s not impossible. As you practice using musical staff, you will slowly remember what every symbol means. Before you know it, you’ll be reading the symbols like a book.

So, if you are a classical musician, student, or fan of any music genre and want to learn more about the fantastic world of music, feel free to bookmark this article so you can come back to this as needed!

Do you know of any musical symbols that we didn’t cover here? Still confused about something? Let us know in the comments below.

A key is a group of notes on which a piece of music is based. A piece of music can use all the notes in the key, or an extract from the notes and sometimes involve other notes. Most popular music is written in a single key, but some pieces of music change key along the way.

Contents

1. Major and minor keys

A distinction is made between major keys and minor keys. Major keys are based on a major scale, and minor keys are based on a natural minor scale. For example, the key of C major consists of the notes from the C major scale, and the key of A minor consists of the notes from the A natural minor scale.

The first note in the scale is called the root note or the tonic, and it is also the root note of the key. The root note is the central note to which all other notes in the key are related. It is a stable resting place on which the melody can settle.

Below is the melody of the English lullaby ‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’. The melody consists of the notes C, D, E, F, G, and A all of which belong to the key of C major:

When listening to the melody, the note C is experienced as the natural end where the melody comes to rest. Therefore, it is evident that the root note is C, and the key is C major.

Musical compositions in major keys often sound happy and uplifting. Musical compositions in minor keys often sound sad and melancholic.

Relative keys

A major and minor key are relative to each other when they share all the same notes. For example, the keys of G major and E minor are relative to each other:

Each major key has a relative minor key and vice versa. The root note of the relative minor key is a minor third below the root note of the major key. In the example above, the root note E falls a minor third below the root note G.

Parallel keys

A major and minor key are parallel to each other when they share the same root note. For example, the keys of C major and C minor are parallel to each other:

Parallel keys have different notes. Minor keys differ from major keys in that the third, sixth, and seventh degrees in the key are lowered by a half step.

2. Key signatures

In music notation the keys are indicated with a key signature at the beginning of the staff immediately after the clef. The key signatures determine the notes of the music piece, and thus either a major key or its relative minor key.

Below is an overview of the keys and key signatures. The relative keys C major and A minor have no sharps or flats in the key signature. All other keys have between one and seven sharps or flats. Keys with up to three sharps or flats are the most common.

The circle of fifths is a helpful visual aid tool to remember the keys and their key signatures. If you remember the major keys, you can easily find the relative minor keys by going down a minor third from the root note of the major key.

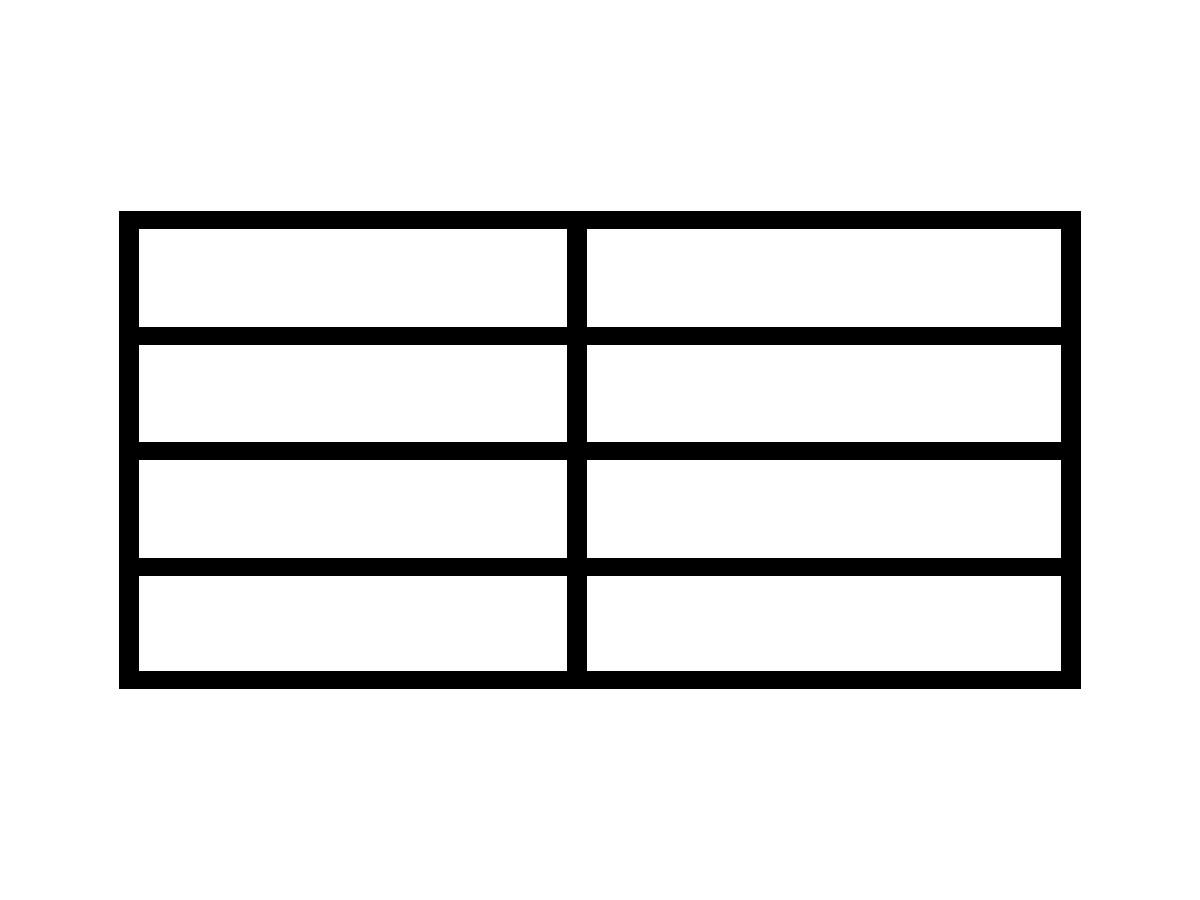

| Major | Minor | Sharps or flats | Key signature |

|---|---|---|---|

| C major | A minor | 0 |  |

Sharp key signatures

Each time the root note is raised by a perfect fifth from C major, a sharp is added to the key. For example, the key of G major (a perfect fifth above C major) has one sharp, and the key of D major (two perfect fifths above C major) has two sharps.

The root note of a major key falls a half step above the last sharp in the key signature. The order of the sharps can be remembered with the saying ‘Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle’. Below is an overview of sharp key signatures:

| Major | Minor | Number of sharps | Sharp notes | Key signature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G major | E minor | 1 | F♯ |  |

| D major | B minor | 2 | F♯, C♯ |  |

| A major | F♯ minor | 3 | F♯, C♯, G♯ |  |

| E major | C♯ minor | 4 | F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯ |  |

| B major | G♯ minor | 5 | F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯ |  |

| F♯ major | D♯ minor | 6 | F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯ |  |

| C♯ major | A♯ minor | 7 | F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯ |  |

Flat key signatures

Each time the root note is lowered by a perfect fifth from C major, a flat is added to the key. For example, the key of F major (a perfect fifth below C major) has one flat, and the key of B♭ major (two perfect fifths below C major) has two flats.

The root note of a major key is identical with the second last notated flat in the key signature (with the exception of F major). The order of the flats can be remembered with the saying ‘Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles’ Father’. Please note that it corresponds to the order of sharps but in reverse order. Below is an overview of flat key signatures:

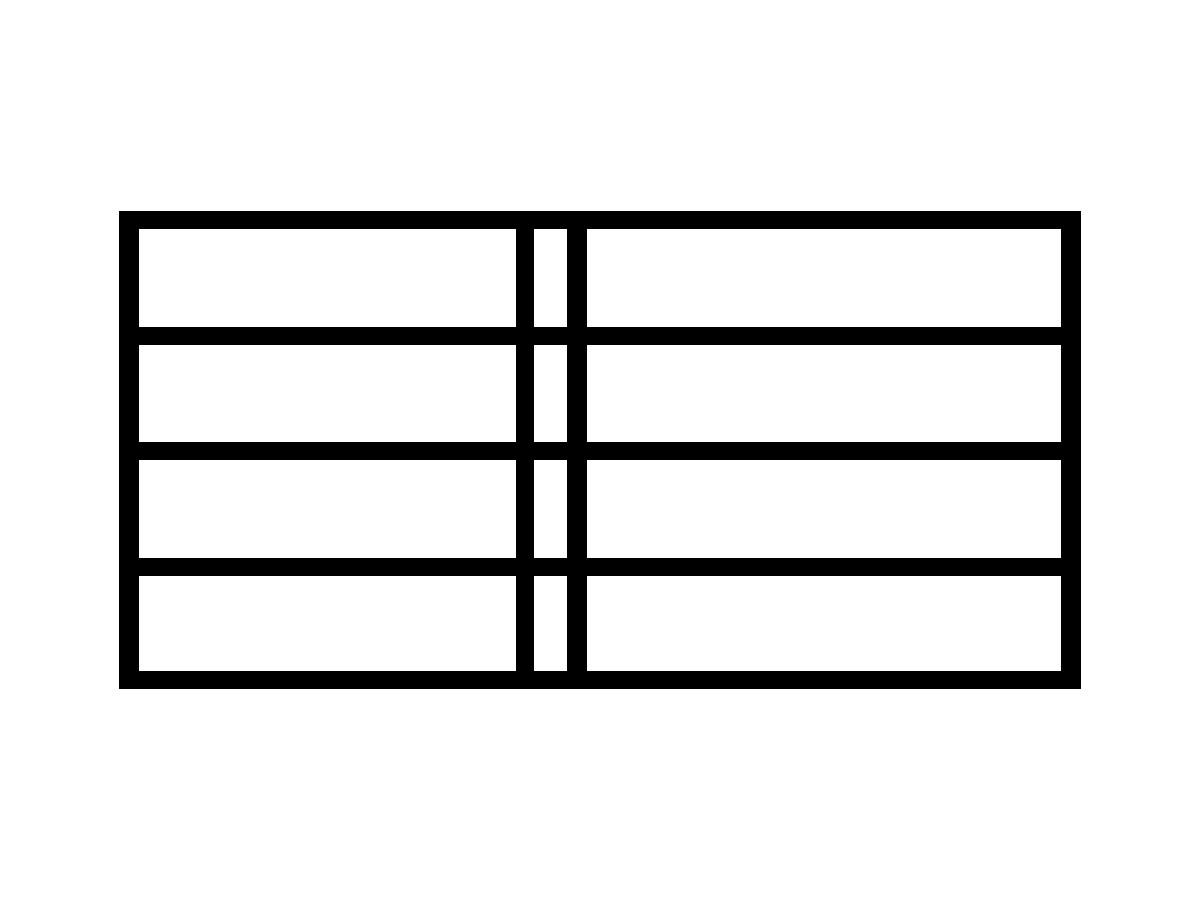

| Major | Minor | Number of flats | Flat notes | Key signature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F major | D minor | 1 | B♭ |  |

| B♭ major | G minor | 2 | B♭, E♭ |  |

| E♭ major | C minor | 3 | B♭, E♭, A♭ |  |

| A♭ major | F minor | 4 | B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭ |  |

| D♭ major | B♭ minor | 5 | B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭ |  |

| G♭ major | E♭ minor | 6 | B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭ |  |

| C♭ major | A♭ minor | 7 | B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭ |  |

Enharmonic keys

Keys with an identical pitch (i.e. notes that fall on the same key on the piano) that have different names and notation are called enharmonic keys. The key of G♭ major and E♭ minor are the enharmonic equivalents to F♯ major and D♯ minor, respectively.

Keys with seven sharps or flats (C♯ major/A♯ minor and C♭ major/A♭ minor) are rarely used. Normally, enharmonic equivalent keys are used (D♭ major/B♭ minor and B major/G♯ minor) with five sharps or flats instead, as they are easier to read.

3. Chords in a key

The notes in any key can be composed to seven different triads: three major chords, three minor chords, and a diminished chord. The triads are composed by stacking two thirds on each note in the key.

In major keys, the notes are made up of a major scale, and the chords at each degrees of the scale are major, minor, minor, major, major, minor, and diminished. Below are the chords in C major:

Most pieces of music mainly use chords composed of notes from the piece of music’s key as they fit together well. Usually, the chords of the key’s first, fourth, and fifth degree are most commonly used. In major keys, all three are major chords.

In minor keys, the notes are made up of a natural minor scale and the chords at each degree of the scale are minor, diminished, major, minor, minor, major, and major. Below are the chords in A minor:

In minor keys, as in major keys, the chords of first, fourth, and fifth degree are most commonly used. In minor keys all three are minor chords. However, in minor keys it is common to play the chord on fifth degree as a major chord instead of a minor chord. By changing the chord to a major chord, the leading tone of the key is included in the chord, which then has a greater force of attraction towards the chord on the first degree.

In the example above, the chord on the fifth degree is an Em (consisting of the notes E, G, and B). By changing the chord to E (consisting of the notes E, G♯, and B), the note G♯ is included in the chord, which is the leading tone to A, which is the root note of the key.

Relative keys such as C major and A minor share all the same notes and chords, but the chords used most on the first, fourth and fifth degree of the key are different. In C major the chords most used are C, F and G, and in A minor they are Am, Dm, and Em (or E if the chord is played as a major chord).

The chords in a key can be varied by adding one or more notes. It is relatively common to add a seventh to the chords, especially to the chord on the fifth degree. Below are the chords in C major with an added seventh:

The chords at each stage of the major keys are called tonic chord, supertonic chord, mediant chord, subdominant chord, dominant chord, submediant chord, and leading-tone chord. In minor keys, the chords have the same names, except for the last chord, which is called the subtonic chord, because minor keys do not have a leading tone on the seventh degree.

Overview of the chords

Below is an overview of the chords for each of the seven degrees in major keys with up to six sharps or flats. The circle of fifths is a helpful visual tool to find the chords in a key.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Dm | Em | F | G | Am | Bo |

| D♭ | E♭m | Fm | G♭ | A♭ | B♭m | Co |

| D | Em | F♯m | G | A | Bm | C♯o |

| E♭ | Fm | Gm | A♭ | B♭ | C♭m | Do |

| E | F♯m | G♯m | A | B | C♯m | D♯o |

| F | Gm | Am | B♭ | C | Dm | Eo |

| F♯ | G♯m | A♯m | B | C♯ | D♯m | E♯o |

| G♭ | A♭m | B♭m | C♭ | D♭ | E♭m | Fo |

| G | Am | Bm | C | D | Em | F♯o |

| A♭ | B♭m | Cm | D♭ | E♭ | Fm | Go |

| A | Bm | C♯m | D | E | F♯m | G♯o |

| B♭ | Cm | Dm | E♭ | F | Gm | Ao |

| B | C♯m | D♯m | E | F♯ | G♯m | A♯o |

4. Key identification

The key of a piece of music can be found by examining the key signature, chords, and melody of the piece. Studying the piece of music’s chords and, if possible, its key signature will often suffice for determining the key. Please note that the key may change throughout the piece of music (see section 6).

Key signatures

If the piece of music is available as sheet music, the key signature establishes a specific major key or its relative minor key (see section 2). To determine whether the key is major or minor, the chords and, sometimes the melody must be examined.

Any accidentals do not normally affect the key. Accidentals are relatively common in almost all musical genres. If the key changes along the way, normally you will not use accidentals, but introduce a new key signature.

Chords

Most pieces of music both start and end with the chord on the first degree of the key. Therefore, if a piece of music starts and ends with the chord Cm, for example, it is a clear indication that the key is C minor.

Pieces of music primarily use the chords on the first, fourth, and fifth degree of the key (see section 3). The chords can thus establish a specific key, and at the same time they allow for a separation of a major key from its relative minor key.

For example, the keys of C major and A minor share the same key signature, but the primary chords on the first, fourth, and fifth degree are different. In C major, the primary chords are C, F, and G, and in A minor they are Am, Dm, and Em (the latter is often played as a major chord).

In the example below from ‘Imagine’ (John Lennon, 1971), the key signature indicates that the key is either C major, or A minor. The chords confirm that the key is C major:

Melody

The melody of a piece of music does not necessarily use all seven different notes in the key. Often, however, very few notes will suffice for determining the scale and thereby narrowing the possible keys.

For example, if a melody uses the notes E and F, the key can only be C major, F major, or one of their two relative minor keys. It cannot be a sharp key because the note F has a sharp in all sharp keys. It cannot be a flat key with two or more flats because the note E has a flat in all these keys.

In some cases, minor keys are recognized by the use of accidentals in the melody. This is because the leading tone on the seventh degree in minor keys can only be notated using an accidental. For example, the key of A minor has no sharps or flats in the key signature, but the leading tone G♯ is notated using an accidental.

The melody often strives towards the root note and often falls to rest on the root note, without the listener feeling the need for the melody to continue. Furthermore, the last note of the melody is often the same as the root note. The notes and movement of the melody can thereby determine the key.

5. Music modes

Most music is written in a major key or minor key, but there is also music written in one of the music modes. The music modes are the seven scales originating from the Middle Ages which today are used mainly in folk music, jazz, and rock. Their names are Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian.

The music modes consist of the same notes as a major scale, but they start on each of the seven degrees of the major scale. For example, a C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, and B) contain D Dorian on the second degree (D, E, F, G, A, B, and C) and G Mixolydian on the fifth degree (G, A, B, C, D, E, and F). If you don’t know them, you can read about the music modes in the text about scales.

For each major scale there is a relative minor scale with the same notes. Likewise, there are seven music modes with the same notes for each major scale. Therefore, music modes cannot be identified based on the notes alone. It is also necessary to determine the root note.

In the example below, the folk tune ‘What Shall We Do’ has no sharps or flats in the key signature and uses all seven different natural notes (C, D, E, F, G, A, and B). Normally, this means that the key is C major or A minor, but it is clearly heard that the root note is a D. The note D falls on the second degree of the key C major, and therefore the key is D Dorian:

Notation of music modes

Music modes can be notated in two ways. Sometimes, music modes are notated with the same key signature as the major key with which they share the notes. This is the case in the example above, where D Dorian is notated with no sharps or flats in the key signature, like C major, because it shares all the same notes with C major.

In other cases, the music modes are notated with the same key signature as the major or minor key with which they share the root note. With this method of notation, D Dorian is notated with the same key signature as D minor, because it shares the root note with D minor. Below is the example from earlier in D Dorian, but this time notated with the same key signature as D minor:

The advantage of the latter notation method is that the key signature gives an indication of the root note of the piece of music, because the key signature belongs to the minor key with the same root note. The disadvantage is that the key signature does not reflect the notes and therefore accidentals must be used to correct the notes afterwards.

The music modes Lydian and Mixolydian are often notated with the key signature as the major key with which they share root note, because there is only one note’s difference and because the need for accidentals therefore is small. For example, the only difference between G Mixolydian (G, A, B, C, D, E, and F) and G major (G, A, B, C, D, E, and F♯) is the last note.

The music modes Dorian and Phrygian are often notated with the same key signature as the minor key with which they share the root note, because there is only one note’s difference and because the need for accidentals therefore is small. For example, the only difference between D Dorian (D, E, F, G, A, B, and C) and D minor (D, E, F, G, A, B, and C) is the second-last note.

The relation to major and minor keys

The Ionian mode is identical to the major scale, and the Aeolian mode is identical to the natural minor scale. For example, C Ionian is identical to C major and A Aeolian is identical to A natural minor. In other words, the major and minor keys are a continuation of the music modes Ionian and Aeolian, but with new names.

Some people do not distinguish between major and Ionian or minor and Aeolian. They use the names synonymously. Others attach particular importance to the music modes because they originate in the modal music of the Middle Ages. They only use the names of the music modes in connection with modal music, new and old.

6. Modulation

A modulation is a change from one key to another. When a piece of music changes the key, it is said that the piece of music modulates to a new key. Modulations are relatively common in most music, but are used especially in longer pieces of classical music to create variation, momentum and provide renewed energy to the music.

A modulation is recognized by a change in the notes of the piece of music. It can be expressed by using new chords and notes in the melody, which do not belong to the existing key. In music notation, modulations usually involve either a change of key signature or the introduction of accidentals.

An exception to this is modulations to the relative key, which use the same notes as the main key. In this case, there is no change to the notes and the key signature, but the melody and the chords adapt to the new root note. In practice, this means, among other things, that the primary chords on the first, fourth, and fifth degree change.

In the following example from ‘You’ll Be in My heart’ (Phil Collins, 1999) the piece of music modulates from F♯ major in the verse to E♭ major in the chorus. The modulation is reflected by a change of the key signature and by a change of the chords above the staff. The chords B♭, E♭, and A♭/E♭ belong to the new key:

If a piece of music changes its key briefly, it is usually called a tonicization rather than a modulation. In a tonicization the new key is abandoned fairly quickly, usually returning to the original key, therefore the key is not established.

Common modulations

Some modulations are more common than others. In popular music, one of the most common modulations is a modulation to the key a half step or a whole step above the existing key. This modulation is often used in the last chorus to give the song a boost, so the listener experiences it with renewed energy.

‘Love on Top’ (Beyoncé, 2011) is an example of a song that modulates up a half step several times. The chorus repeats four times at the end of the song, each time modulated up a half step. The key of the song is C major, and the last four choruses are in D♭ major, D major, E♭ major and E major, respectively.

Another common modulation in both classical and popular music is a modulation to the relative key. Since the two keys share all the same notes, this modulation is not significantly experienced. A characteristic of this modulation is a change from major to minor and vice versa.

‘Mirrors’ (Justin Timberlake, 2009) is an example of a song that modulates to the relative key. The key of the song is C minor, but in all the choruses the song modulates to E♭ major. After each chorus, the song modulates back to C minor.

A third and relatively common modulation in both classical and popular music is a modulation to the parallel key. Since the two keys have different notes, this modulation is experienced as more significant than a modulation to the relative key. In popular music, this modulation is often used between verse and chorus.

‘Happy Together’ (The Turtles, 1967) is an example of a song that modulates to the parallel key. The key of the song is F♯ minor, but in all the choruses the song modulates to F♯ major. The modulation from minor to major adds a positive energy to the song’s chorus.

In classical music, it is also common to modulate to the dominant key (up a perfect fifth) and to the subdominant key (down a perfect fifth). These keys are closely related to the main key, as the only difference is one note making it easy to create a smooth transition to the new key.

Types of modulation

Basically, there are two different types of modulation:

- Direct modulation (also called phrase modulation). A modulation directly to the new key without any prior notice or preparation.

- Common chord modulation (also called pivot chord modulation). A modulation to the new key using one or more chords belonging to both keys.

The direct modulation is the most common type of modulation in popular music. The above songs, ‘Love on Top’ and ‘Happy together’ are both examples of direct modulations. Another example is ‘Wouldn’t It Be Nice’ (The Beach Boys, 1966), which suddenly modulates from A major to F major, when the song starts:

The common chord modulation is more common in classical music, but is also used in popular music. The chords used to create a smooth transition from one key to another are called pivot chords. For example, the chord Fm belongs to both C minor (fourth degree) and F minor (first degree), and can therefore be used as a pivot chord.

In the example below, ‘Save me’ (Queen, 1980) modulates the piece of music from G major in the verse to D major in the chorus. The pivot chords G and D are used in the transition between the two keys. The chords fall on the first and fifth degree in G major and on the fourth and first degree in D major:

Common chord modulations often take place between keys that are closely related with many chords in common. The more chords two keys have in common, the better is the possibility of using pivot chords for the modulation.

7. Transposition

Transposition is the process of moving a piece of music from one key to another. In practice, this means that all notes and chords move a specific interval up or down. For example, a transposition from C major to E♭ major involves moving all notes and chords up a minor third because there is a minor third from C up to E♭.

A transposition changes the pitch of the notes only, and not the structure of the notes and chords. In other words, the piece of music remains the same but is moved to a higher or lower register. In the example below, the English lullaby ‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’ is first played in C major and then transposed to E♭ major:

Transposition is used in many situations, such as:

- If a song is too high or low for a singer. The song is transposed to a key with a register that better matches the singer’s voice.

- If a piece of music is difficult to play because it has a key signature with many sharps or flats. The piece of music is transposed into a simpler key.

- If two musicians are going to play together, but have each learned a piece of music in a different key. One musician transposes the piece of music to the other’s key.

If a piece of music is available in music notation software, it is often possible to transpose the piece of music to a different key automatically. Alternatively, there are several methods of transposition, as described below. Combining the methods can be useful.

Transposition using intervals

All notes and chords are moved up or down an interval corresponding to the distance between the keys. For example, if a piece of music is to be transposed from C major to E major, all notes and chords must be moved up a major third.

Here is an example of four chords in C major: C, Dm, G7, and Am. Here, the same four chords have moved up a major third to E major: E, F♯m, B7, and C♯m. Please note that the transposition only changes the root notes and not the chord types.

Transposition using movements

The first note and chord are moved up or down an interval corresponding to the distance between the keys. The subsequent notes and chords are transposed by copying intervallic movement from note to note, and chord to chord.

Here is an example of four chords in D major: D, Em7, F♯m, and G. The root note of the chords moves stepwise up in the key. Here, the first chord is transposed to D major and the subsequent stepwise motion is copied: C, Dm7, Em, and F.

Transposition using degrees

All notes and chords are moved from the degree of the existing key to the corresponding degree in the new key. For example, in order to transpose a chord on the fourth degree in G major to F major, it must be moved to the fourth degree in F major.

Here is an example of four chords in G major: G, Am7, D7, and Em. The chords fall on the first, second, fifth and sixth degrees in the key. Here are the same four chords transposed to the same four degrees in F major: F, Gm7, C7, and Dm.

Transposition using key signatures

This method can only be used if the music is available as sheet music. The key signature at the beginning of the staff is changed to the new key. All notes and chords are then moved up or down a number of degrees corresponding to the number of degrees between the keys. Any accidentals do not matter when the notes are moved.

Finally, notes with accidentals are corrected. If a note in the original key has an accidental, the note is changed accordingly in the transposed version. Below is an example from ‘The Entertainer’ (Scott Joplin, 1902) in C major:

In the following example, the piece of music is transposed to A major. The transposition has been done by changing the key signatures to three sharps, and by moving all notes down three degrees (because there are three degrees from C down to A). Finally, the two notes with an accidental are raised a half step, just as they are in the original key:

In the example above, the accidentals are the same in both the original key and the new key; however, this is not always the case. For example, if a note has a flat in the key signature of the new key, the note is raised by a half step using a natural sign and not by using a sharp.