Why do we call a line of poetry a line in English when it is a vers in French (though we do use verse and verses to mean ‘poetry’)? What did Middle English poets call their lines of poetry? In their (at least) trilingual world, they had plenty of words for the basic units of poetry. A metrical line is a versus in Latin (and by extension versus means a set of verses, i.e. a poem). Continental and Insular French usage follows this: a vers is a metrical line. Vers signifies the core unit of poetry, marked out by repeating segments of metre and rhyme. Poetry was in verses whether it was copied as prose (with its units marked by metrical punctuation) or lineated as verse.

Words gain and change meanings by various processes, one of which is metonymic change, shifts of meaning which occur when the name of a related or contiguous thing is transferred over to a new referent. Lines of writing on the page take their name from the ruled lines a scribe makes on a manuscript. These graphic lines of writing, the rows of letters and words the scribe makes on the page, then by extension give their name to the units of text that are written on them. From the early fifteenth century, French uses ligne to refer to metrical lines as well as to graphic lines. Also by metonymy, vers in English and French soon refers to the form poetry itself (often as opposed to prose), that which is composed of lines of verse.

When and why did poets writing in English first refer to the metrical units of their own poems and what did they call their metrical lines? For a long time poets just got on with writing lines of poetry without stopping to refer to this obvious and defining aspect of their own form. Words like baston, and later staf, appear and disappear as short-lived words to name the metrical line when desired (though confusingly both might also mean ‘stanza’). Until the end of the fourteenth century, vers(e) mainly appears in Middle English when authors introduce citations of Latin (whether this be quotations from the Bible, especially the psalms, of proverbial wisdom, or for Latin poetry) and inscriptions on buildings. It doesn’t refer to the metrical units of English poetry, but then it probably doesn’t need to: it’s obvious that verse is verse.

Chaucer uses vers conventionally to refer to citations from Latin poetry. He uses line to refer to lines of writing, i.e. graphic lines in letters and documents. But he also calls his own metrical lines vers (the same form for singular and plural), as one might exactly expect given his francophone training and reading. When Chaucer refers to the ‘next vers’ (Troilus and Criseyde) or ‘next this vers’ (Parliament of Fowls), he means not the next stanza (as an unwary modern reader might think) but the next line. In the House of Fame, he concedes that ‘som vers’ might ‘fayle in a sillable’: a metrical line might be a syllable short. The Man in Black in the Book of the Duchess sorrowfully utters his complaint ‘of rym ten vers or twelve’, and what Chaucer gives us has eleven lines.

Chaucer thus starts the fashion for metaliterary deixis. This is a specialised kind of discourse deixis, using technical terms of poetics to self-reflexively describe poetry’s own construction and/or to locate the reader in relation to elements of the construction. The particular choice of technical term tells us something about the sort of poetry this is claiming to be. Chaucer counts syllables, just as a French poet does, and not surprisingly he thinks of his lines as vers. He makes, I think, a different point when he calls Troilus and Criseyde ‘Thise woful vers’ (echoing Boethius’s description of the ‘heartbreaking verse’ and ‘woeful songs’ that he composes in his miserable imprisonment in The Consolation of Philosophy). Rather like the end of Troilus, where the poem is told to subject itself to classical poetry rather than to rival English poems, this is a small but meaningful humble-brag at the poem’s start. Calling Troilus ‘vers’ associates it with classical poetry rather than English narrative forms.

For some fifteenth-century poets, vers and line are interchangeable. James I of Scotland in the Kingis Quair (?1424) names his own stanza-units as ‘thir versis sevin’ (referring to a one-stanza song) and as ‘my buk in lynis sevin’. James articulates his lines so as to count them, to flag up his choice of Chaucerian stanza form. Just as French by 1420 uses ligne and vers, so James uses both terms, just as he uses other French terms like ‘copill’ for stanza.

John Lydgate, a Benedictine monk with a university training at Oxford, thinks a little differently. He reserves the word verse in his English poetry for references to Latin poetry (as far as I can tell). When referring to his own metrical units in the Troy Book (probably the first poem of his career, written from 1412–20), he uses the word line. He says that he needs Chaucer’s help to find some good words to put in ‘the crokid lynys rude / Which I do write’. Near the end of this long narrative, he tells us that he must ‘spende a fewe lines blake’ translating the last chapter of his source. This sounds like humility: calling his work mere graphic lines on a page, merely ink.

Humility topoi, though, are often fifteenth-century humble-brags. Just before Lydgate reaches the last chapter of his source, the Historia Destructionis Troiae, he tells us that he has nearly reached the ‘boundis set of my labour’, the edges of the plot of land set for him to work. He can hardly summon the strength to write: ‘the bestes and oxes of my plow’ are weary, faint and weak to keep climbing up the hill all day long. Soon, however, he will fix ‘a stake’ ‘at the londes ende / Of Troye boke’ and be done with his long translation. He pictures his work as a ploughed field, organized as it was in shared medieval open-field farming where individual plough-strips were marked out by stakes.

This agricultural imagery claims Lydgate’s lines as metrical verses without ever having to say so. In his encyclopaedia, the Etymologies, Isidore of Seville explains that versus means both a furrow and a metrical line because ancient poets would supposedly write from left to right and then turn the pen (like a plough turning at the end of a field) to the line below from right to left. So Lydgate’s ploughing is versification, and we are being invited to admire his long technical labour.

Something similar is going on with the idea that Lydgate’s lines are ‘crokid lynys rude’. You might think that a line of verse written on a straight ruled line can’t be crooked in any literal sense (unless the scribe was really making a mess of things). But crokid in Middle English means ‘lame’ as well as wonky. This lameness is another gesture at versification. For something to limp it must have feet (English and French poems, admittedly, don’t have feet in the classical sense, but English and French poets used ‘feet’ to mean syllable). Lydgate feigns that his verse limps, that his lines are crooked, but this humble-brag nudges the reader to remember the metricality of his verse that runs on its feet unstopped for 30,000 lines.

Eventually, verse meaning ‘metrical line’ becomes much less popular than ‘line’ for referring to a metrical unit, though we still talk about verses and verse. I think that this is because verse in the late medieval period increasingly refers to part of a song, usually the non-repeating part as opposed to the burden or chorus. Verse names a part of something which is sung, whether that is a liturgical versicle, a psalm, or a secular song. Most of the early citations for verse as ‘stanza’ appear in the context of music or singing. It wasn’t until the sixteenth century that this meaning migrated metonymically from song lyrics to lyrics-as-poems and then as a conventional way of describing stanzas. Verse in English then mostly refers to stanzas (or to poetry generally), with line having taken over as the standard term for a metrical line.

Unlike prose writing, which is written in sentences and paragraphs, poems are written in lines and stanzas. Choosing how to arrange those lines is part of the craft of poem writing. Poets consider how to situate words, lines and spaces in order to create rhythm and tempo. These poetic devices help to create a mood which supports the theme of the poem.

Lines and Stanzas

Poets arrange lines in order to support the mood and rhythms of their themes. Poetry can be arranged in stanzas, which are considered “strophic,” or in lines, which is considered “stichic.”

A stanza is set apart by using spaces above and below to indicate an individual unit. Using stanzas creates a song-like poem and sets up a structure which makes room for a change in subject matter, similar to the way paragraphs do.

Arranging poems by lines creates a structure that feels more like speech than song. Narrative poems, epic poems and free verse are usually arranged by lines.

Rhyme Scheme Arrangements

In rhymed poetry, the lines are arranged according to a rhyme scheme. If you are going to use rhyme in your poem, you will need to develop a rhyme scheme.

Rhyme schemes are presented as a series of sequenced letters that correspond to the lines of a poem. Starting with the letter “A,” each line is designated by a different letter until a rhyme appears at the end of a line.

For example, if a poem has a rhyme scheme of ABBA, the first and fourth lines will rhyme, and the second and third lines will rhyme.

In a rhyme scheme of ABCA, the first and fourth lines will rhyme, but the second and third lines will not.

Restrictions of Meter and Verse

The lines in metered poetry are arranged in a specific pattern and structure. For instance, English sonnets are poems that require fourteen lines. The first eight lines follow a specific rhyme scheme and the last six lines follow a different rhyme scheme.

The change in rhyme scheme also indicates a change in subject matter. Sonnets are usually written in iambic pentameter. This means that each line contains five iambic feet, or groups of two syllables that create a pattern of one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllable.

Each line of an English sonnet will begin at the left margin and end after each repetition of five iambic feet. In order to create poems that conform to specific structures, you will need to learn the requirements of each form. For instance, a couplet is a two-lined stanza.

Visualize It: Concrete Poetry

Line arrangement is the most important element in concrete poetry because the arrangement of the lines supports the topic of the poem.

For instance, in a poem about falling down the stairs, the writer could arrange the words and lines to look like a staircase.

In one case, Poet Jeffery Sasu arranges synonyms for “spiral” in the shape of a spiral. Jack Prelutsky, in his poem “I Was Walking in a Circle,” arranges the words in a circle. Reading the poem, the reader soon realizes that there is no end to it.

I was wondering if someone knew the word that describes a poem where each word begins with the letters of a previous word, of if such a word even exists.

An example of such a poem is this: http://crosswords.net23.net/poems/Joshua.html

(I wrote it)

Someone told me there was a word for this kind of thing, but he couldn’t remember it, either.

Mitch

70.1k28 gold badges137 silver badges260 bronze badges

asked Sep 4, 2012 at 20:00

1

You started with an acrostic of ‘JOSHUA’:

An acrostic is a poem or other form of writing in

which the first letter, syllable or word of each line, paragraph or

other recurring feature in the text spells out a word or a message.

Each instance after that is new acrostic of the word made from each letter in the original.

answered Sep 4, 2012 at 20:05

3

The scholarly term technopaegnia encompasses all kinds of interplay between the words of a poem and its structure, including (but not limited to) picture poems, acrostics, and other such puzzles. For facts about the term and links to many interesting examples of such poetry – ancient and modern – see my answer to another question.

answered Sep 4, 2012 at 21:40

MetaEdMetaEd

28.1k17 gold badges83 silver badges135 bronze badges

2

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A line is a unit of language into which a poem or play is divided. The use of a line operates on principles which are distinct from and not necessarily coincident with grammatical structures, such as the sentence or single clauses in sentences. Although the word for a single poetic line is verse, that term now tends to be used to signify poetic form more generally.[1] A line break is the termination of the line of a poem and the beginning of a new line.

The process of arranging words using lines and line breaks is known as lineation, and is one of the defining features of poetry.[2] A distinct numbered group of lines in verse is normally called a stanza. A title, in some poems, is considered a line.

General conventions in Western poetry[edit]

Conventions that determine what might constitute line in poetry depend upon different constraints, aural characteristics or scripting conventions for any given language. On the whole, where relevant, a line is generally determined either by units of rhythm or repeating aural patterns in recitation that can also be marked by other features such as rhyme or alliteration, or by patterns of syllable-count.[3]

In Western literary traditions, use of line is arguably the principal feature which distinguishes poetry from prose. Even in poems where formal metre or rhyme is weakly observed or absent, the convention of line continues on the whole to be observed, at least in written representations, although there are exceptions (see Degrees of license). In such writing, simple visual appearance on a page (or any other written layout) remains sufficient to determine poetic line, and this sometimes leads to the suggestion that the work in question is no longer a poem but «chopped up prose».[4] A dropped line is a line broken into two parts, with the second indented to remain visually sequential.

In the standard conventions of Western literature, the line break is usually but not always at the left margin. Line breaks may occur mid-clause, creating enjambment, a term that literally means ‘to straddle’. Enjambment «tend[s] to increase the pace of the poem»,[5] whereas end-stopped lines, which are lines that break on caesuras (thought-pauses[6] often represented by ellipsis), emphasize these silences and slow the poem down.[5]

Line breaks may also serve to signal a change of movement or to suppress or highlight certain internal features of the poem, such as a rhyme or slant rhyme.

Line breaks can be a source of dynamism, providing a method by which poetic forms imbue their contents with intensities and corollary meanings that would not have been possible to the same degree in other forms of text.

Distinct forms of line, as defined in various verse traditions, are usually categorised according to different rhythmical, aural or visual patterns and metrical length appropriate to the language in question. (See Metre.)

One visual convention that is optionally used to convey a traditional use of line in printed settings is capitalisation of the first letter of the first word of each line regardless of other punctuation in the sentence, but it is not necessary to adhere to this. Other formally patterning elements, such as end-rhyme, may also strongly indicate how lines occur in verse.

In the speaking of verse, a line ending may be pronounced using a momentary pause, especially when its metrical composition is end-stopped, or it may be elided such that the utterance can flow seamlessly over the line break in what can be called run-on.

Degrees of license[edit]

In more «free» forms, and in free verse in particular, conventions for the use of line become, arguably, more arbitrary and more visually determined such that they may only be properly apparent in typographical representation and/or page layout.

One extreme deviation from a conventional rule for line can occur in concrete poetry where the primacy of the visual component may over-ride or subsume poetic line in the generally regarded sense, or sound poems in which the aural component stretches the concept of line beyond any purely semantic coherence.

At another extreme, the prose poem simply eschews poetic line altogether.

Examples of line breaks[edit]

scolds Forbid

den Stop

Must

n’t Don’t

The line break ‘must/n’t’ allows a double reading of the word as both ‘must’ and ‘mustn’t’, whereby the reader is made aware that old age both enjoins and forbids the activities of youth. At the same time, the line break subverts ‘mustn’t’: the forbidding of a certain activity—in the poem’s context, the moral control the old try to enforce upon the young—only serves to make that activity more enticing.

While Cummings’s line breaks are used in a poetic form that is intended to be appreciated through a visual, printed medium, line breaks are also present in poems predating the advent of printing.

Shakespeare[edit]

Examples are to be found, for instance, in Shakespeare’s sonnets. Here are two examples of this technique operating in different ways in Shakespeare’s Cymbeline:

In the first example, the line break between the last two lines cuts them apart, emphasizing the cutting off of the head:

With his own sword,

Which he did wave against my throat, I have ta’en

His head from him.

In the second example, the text before the line break retains a meaning in isolation from the contents of the new line. This meaning is encountered by the reader before it being modified by the text after the line break, which clarifies that, instead of «I, as a person, as a mind, am ‘absolute,'» it ‘really’ means: «I am absolutely sure it was Cloten»:

I am absolute;

‘Twas very Cloten.

Metre[edit]

In every type of literature there is a metrical pattern that can be described as «basic» or even «national»[dubious – discuss]. The most famous and widely used line of verse in English prosody is the iambic pentameter,[7] while one of the most common of traditional lines in surviving classical Latin and Greek prosody was the hexameter.[8] In modern Greek poetry hexameter was replaced by line of fifteen syllables. In French poetry alexandrine[9] is the most typical pattern. In Italian literature the hendecasyllable,[10] which is a metre of eleven syllables, is the most common line. In Serbian ten syllable lines were used in long epic poems. In Polish poetry two types of line were very popular, an 11-syllable one, based on Italian verse and 13-syllable one, based both on Latin verse and French alexandrine. Classical Sanskrit poetry, such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata, was most famously composed using the shloka.

- English iambic pentameter:

- Like to Ahasuerus, that shrewd prince,

- I will begin — as is, these seven years now,

- My daily wont — and read a History

- (Written by one whose deft right hand was dust

- To the last digit, ages ere my birth)

- Of all my predecessors, Popes of Rome:

- For though mine ancient early dropped the pen,

- Yet others picked it up and wrote it dry,

- Since of the making books there is no end.

- (Robert Browning, The Ring and the Book 10, Book The Pope, lines 1-9)

- Latin hexameter:

- Arma virumque canō, Trōiae quī prīmus ab orīs

- Ītaliam, fātō profugus, Lāvīniaque vēnit

- lītora, multum ille et terrīs iactātus et altō

- vī superum saevae memorem Iūnōnis ob īram;

- multa quoque et bellō passūs, dum conderet urbem,

- inferretque deōs Latiō, genus unde Latīnum,

- Albānīque patrēs, atque altae moenia Rōmae.

- (Virgil, Aeneid, Book I, lines 1-7)

- French alexandrine:

- Comme je descendais des Fleuves impassibles,

- Je ne me sentis plus guidé par les haleurs :

- Des Peaux-Rouges criards les avaient pris pour cibles,

- Les ayant cloués nus aux poteaux de couleurs.

- (Arthur Rimbaud, Le bateau ivre, lines 1-4)

- Italian hendecasyllable:

- Per me si va ne la città dolente,

- per me si va ne l’etterno dolore,

- per me si va tra la perduta gente.

- Giustizia mosse il mio alto fattore;

- fecemi la divina podestate,

- la somma sapïenza e ’l primo amore.

- (Dante Alighieri, Divina commedia, Inferno, Canto III, lines 1-6)

Pioneers of the freer use of line in Western culture include Whitman and Apollinaire.

Characteristics[edit]

Where the lines are broken in relation to the ideas in the poem it affects the feeling of reading the poetry. For example, the feeling may be jagged or startling versus soothing and natural, which can be used to reinforce or contrast the ideas in the poem. Lines are often broken between words, but there is certainly a great deal of poetry where at least some of the lines are broken in the middles of words: this can be a device for achieving inventive rhyme schemes.

In general, line breaks divide the poetry into smaller units called lines, (this is a modernisation of the term verse) which are often interpreted in terms of their self-contained meanings and aesthetic values: hence the term «good line». Line breaks, indentations, and the lengths of individual words determine the visual shape of the poetry on the page, which is a common aspect of poetry but never the sole purpose of a line break. A dropped line is a line broken into two parts, in which the second part is indented to remain visually sequential through spacing. In metric poetry, the places where the lines are broken are determined by the decision to have the lines composed from specific numbers of syllables.

Prose poetry is poetry without line breaks in accordance to paragraph structure as opposed to stanza. Enjambment is a line break in the middle of a sentence, phrase or clause, or one that offers internal (sub)text or rhythmically jars for added emphasis. Alternation between enjambment and end-stopped lines is characteristic of some complex and well composed poetry, such as in Milton’s Paradise Lost.

A new line can begin with a lowercase or capital letter. New lines beginning with lowercase letters vaguely correspond with the shift from earlier to later poetry: for example, the poet John Ashbery usually begins his lines with capital letters prior to his 1991 book-length poem «Flow-Chart», whereas in and after «Flow-Chart» he almost invariably begins lines with lowercase letters unless the beginning of the line is also the beginning of a new sentence. There is, however, some much earlier poetry where new lines begin with lowercase letters.

Beginning a line with an uppercase letter when the beginning of the line does not coincide with the beginning of a new sentence is referred to by some as «majusculation». (this is an invented term derived from majuscule).

The correct term is a coroneted verse.

In T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, where ambiguity abounds, a line break in the opening (ll. 5–7) starts things off.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

Because the lines start with capitalized letters, Eliot could be saying «Earth» as the planet or «earth» as the soil.

See also[edit]

- Active listening

- Caesura

- Canons of page construction

- Ellipsis

- Enjambment

- Graphic design

- Part (music)

- Pausa

- Principles of organization

- Repetition (music)

- Run-on sentence

References[edit]

- ^ «Line — Glossary».

- ^ Hazelton, Rebecca (September 8, 2014). «Learning the Poetic Line». Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

Some critics go so far as to say that lineation is the defining characteristic of poetry, and many would say it’s certainly one major difference between most poetry and prose.

- ^ See, for example, the account in Geoffrey N Leech A Linguistic Guide to English Poetry, Longman, 1969. Section 7.3 «Metre and the Line of Verse», pp.111-19 in the 1991 edition.

- ^ See [1] for an example.

- ^ a b Margaret Ferguson; Mary Jo Salter; Jon Stallworthy, eds. (2005). The Norton Anthology of Poetry. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 2034. ISBN 0-393-97920-2.

- ^ ‘Classroom synonym’.com

- ^ Metre, prosody at Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Hexameter, poetry at Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Alexandrine, prosody at Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ Claudio Ciociola, Endecasillabo at Encyclopedia italiana.

STEP UP YOUR POETRY GAME WITH BETTER LINE BREAKS AND ENJAMBMENT

What makes a poem, a poem? Long story short, poetic line breaks. Of course, many other literary elements fuse to make poems croon, but poetry is visibly distinct from prose because its lines are sundered before the page’s natural end, at clearly calculated points. Poems are dialogues between the presence that is the text and the absence that is the white space revealed.

In contrast, where a line ends in a prose piece is arbitrarily dictated by a page’s margins. Hence why “prose poems,” which don’t utilize line breaks, are qualified by the word “prose.” Every prose line runs blindly towards the brink, and once it bumps its head against the uniform white space of the margin (in LTR and RTL scripts), it starts again on the next line, replicating this headlong trajectory over and over until you have pages filled with blocks of text offset by only smidgen indents. Prose flows, but it doesn’t care where it goes.

Although line breaks build poems, many “writers” have no damn clue how to use them effectively. If you’re not taking advantage of the connotative dynamism and aesthetic value of ink abutting blankness afforded by poetic line breaks, you’re not writing the best poetry. In fact, you’re not writing poetry at all.

POETIC LINE BREAKS DEFINITION

First off, let’s define a poetic line break. Quite simply:

A poetic line break is the deliberately placed threshold where a line of poetry ends and the next one begins.

Remember, there’s a difference between a “line” and a “sentence.” A sentence is that grade-school tool that expresses a complete thought. A line is the literal linear streak of text flowing across a page. A line is a container for sentences. A line is a boa constrictor stretched across a paper road, and a sentence is the still-whole squirrel in its belly. Here are some rules to remember about lines and sentences. (The / below represents poetic line breaks and is useful in environments such as this, where space is malleable and digital devices distort).

A poetic line can contain a complete sentence:

A poetic line can also contain multiple sentences:

A poetic line can also contain a sentence and an incomplete sentence:

Or multiple sentences and an incomplete sentence:

Or just an incomplete sentence:

Or even several incomplete sentences:

Already you can see that there’s much we can do within a poetic line. Think of a line as container, a bottle. Inside it, we let sail small ships of sentences and their fragment dinghies.

ENJAMBMENT IS THE KEY TO THE BEST POETIC LINE BREAKS

Now we get to the good stuff (*rubs hands gleefully*). Poetic line breaks can be just as boring as prose’s headlong flow if we schism every line at an “end stop.” An “end stop” is just another word for a period, and a period is just a little black dot that indicates that a sentence is complete. If we end at such an obvious end, our poetry becomes predictable, and this is a no-no because poetry’s greatest offering is linguistic eurekas. Thus, rather than breaking our lines at the end of each complete sentence, we should “enjamb” them.

Enjambment births sentence fragments, multi-dimensional meaning, and visual appeal through the unexpected intrusion of white space. Enjambment’s power isn’t a secret, but many “poets” — perhaps including you, dear reader — don’t fully capitalize on its potential — or worse, use it poorly. In a walnut-shell, I think of enjambment like this:

Enjambment is the point where a sentence fissures and continues on to the next poetic line.”

Let’s see how others define enjambment:

The running-over of a sentence or phrase from one poetic line to the next, without terminal punctuation; the opposite of end-stopped.”

-The Poetry Foundation

Enjambment, also called run-on, in prosody, the continuation of the sense of a phrase beyond the end of a line of verse.”

-Encyclopaedia Britannica

In other words, while I conceptualize enjambment as a point on the page, official definitions present it as a linguistic overflowing. Both modes of thinking about it are useful since enjambment’s fruit really grows from the nexus of breaking and continued meaning. Considering the specific point at where the enjambment occurs can help you craft a more potent line break.

If you’re still confused about the distinction between enjambment and poetic line breaks, here’s an easy way to think about it. There are two types of poetic line breaks. One is end-stopped. The other is enjambed. Enjambed line breaks are poetic bullion.

Enjambment can also be thought of as the intimate, subtly interrupted conversation between the final word of the enjambed line, and the first word of the subsequent line. The preceding and following words, of course, chime in and contribute to the conversation, but the lover’s dialogue happens between those final and first words.

Further, because the final word of an enjambed line bears the precariousness of the brink of white space — generally more white space than its successor — because it teeters on the edge of silence — the poet must ensure that every single end word resonates. This holds true even if the poetic line break is end-stopped, but that little pebble that is a period makes the end-stopped line less vulnerable to the massive blank silence that enjambed final words are exposed to. Similarly, the first word of the subsequent line only has to bear the antecedent uniform margin/gutter, though of course this can be played with via indents and stanza breaks, but we’ll save that for another day.

RULES FOR POETIC LINE BREAKS

In any case, in every case, each poetic line break depends upon a critical choice in diction, and an awareness of its ripple effect in sound and meaning. Here are some mandatory tips to achieve the best poetic line breaks:

Never end a poetic line on an article (a/an, the). The result will be incompleteness, rather than dynamic tension.

Never end a poetic line on a conjunction (and, or, so, nor…). It’s better to have such words at the start of the next line, but it’s even better to restructure the lines so that the conjunction lives hidden amid the momentum of livelier words.

Never end a poetic line on a pronoun (I, me, mine, his, hers, theirs, yours…). These are words that accompany, not words that can jut proudly like a figurehead on a ship’s prow.

Try really hard not to end a poetic line on a preposition. The effect is similar to enjambing on articles and conjunctions, though sometimes the broken prepositional phrase can be interesting.

Line break on unusual nouns and verbs that ring strong as standalone words. As we discussed in 8 Key Literary Elements in Every Written Masterpiece, linguistic poignancy is always crucial, but it becomes critical when the strength of your diction is tested by a page’s white space.

However, be aware that enjambment can rejuvenate common, tired words (light, home, breath, and so on) like no other poetic device. Strategic line breaks are a rare opportunity to reclaim these words from their historical overuse by imbuing them with variegated connotations.

Line break at a rhythmic point to poise meaning and weave a sonic tapestry. Luckily, poetry has shed its rhyming knickers, but that doesn’t mean you can’t play with rhyme, rhythm, and so on sporadically, internally, and effectively via the pauses and acoustic cascades created by poetic line breaks. At the same time, these pauses are sonic cues to read differently, allowing for distinctions and additions in the meaning of your words, fragments, and sentences.

POETIC LINE BREAKS IN ACTION

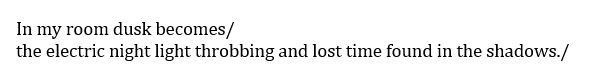

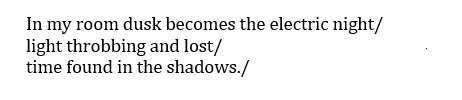

Let’s see an example where an opportunity for enjambment isn’t capitalized upon:

Example A:

*Shakes head sadly.*

If you’re a poet, you should be having a panic attack at the missed opportunities here. And yet, I can’t tell you how many workshop — and published — poems I’ve read that miss these opportunities every single time, every single line. If we instead write:

Example B:

The poem grows a hydra-head of new meanings. Enjambing on “night” means that the container of the first line now holds the idea of dusk becoming electrifying night in the room because the reveal of the artificial night “light” is delayed by the mid-sentence poetic line break. Thus, in Example B, dusk is transformed into both the captivating night as a time of day and the literal night light that gets plugged into electrical sockets, while Example A only illustrates the latter.

Further, in example A, the second line shoots its shot all in one go; there’s no room for surprise. In contrast, Example B’s second line contains an entirely new idea because of where the line begins and end: not only are we gifted the image of the throbbing night light, and later, lost time found in the shadows, we are also given “light throbbing and lost” as an unexpected standalone nugget of meaning simply because I enjambed on the words “night” and then “lost.” This image does not exist in Example A because it wasn’t extracted through the clarity of blank space strategically created via enjambment.

Yet another dimension in meaning in Example B is achieved through the 2nd line break on “lost”, which creates the final container of “time found in the shadows.” In contrast with Example A, there’s an extra gain in Example B — not only has “lost time been found in the shadows,” time itself — and thus double time, extra time — is found there as well thanks to enjambment.

These are just a few lines, so imagine what you can do in a whole poem if you wield poetic line breaks, and more specifically, enjambment, effectively. They are tools that allow you to whittle little poems within your larger piece.

It’s important to note that enjambment doesn’t remove meaning; it simply adds different meanings. All of the ideas in Example B are present in Example A, but B contains at least three other meanings because of two simple line breaks. At the same time, be aware that you will often have to choose between additional meanings when employing enjambment. Breaking on one word versus another may create an alternative, equally powerful sub-meaning, and this is when you have to consider what enjambed connotation works better within the context of your entire poem.

Also keep in mind that poetic line breaks are an editing tool; they generally come after you first scribble down your creation. This is true for several reasons. If you hand-write your first drafts, the lines will likely sprawl out with much wider spacing than what will be in their final typeset form. When the poem gets transferred to the computer, its entire appearance changes — and since the conversation between all of a poem’s line breaks and the resulting white space result in an aesthetic that’s intrinsic to the poem’s effect, you can’t polish those line breaks until you have a sense of what your poem will look like in its ultimate form.

Secondly, regardless of the mechanics of your composition, editing is a process of both adding and cutting content, so entire lines and words can disappear or rear their heads, drastically altering the look of your poem, and the corresponding enjambment. If you try to edit according to predetermined poetic line breaks, you’re going to end up with a tortured piece whose corset is too tight to allow its words to breathe.

Poetic line breaks add to a more fulfilling experience, both from a creative perspective for you as an artist, and for your readers, breathing close to pages filled with your words as their night lights throb on and off, on and off.