Since different instruments use different verbs for «play» (弾く、叩く、吹く、even 歌う), is there one nice word to wrap them up? [奏]{かな}でる and its variants (演奏、合奏) sound too formal to me. プレイする?

The scenario would be interviewing the members of the band, asking their most/least favourite of their songs to play.

<The «play» verb> の(が)好き[な、じゃない]曲は?

asked Oct 7, 2016 at 5:47

istrasciistrasci

43.5k4 gold badges105 silver badges253 bronze badges

演奏していて楽しい曲 doesn’t sound overly formal to me, but you can also say やっていて楽しい曲 or 弾【ひ】いていて楽しい曲. The generic word you can use with 楽器 is 弾く (i.e., 楽器を弾く). A drummer won’t complain if you ask this to multiple members in a band simultaneously. When you want to include a vocalist, too, probably やる is the only possible choice. 奏でる would sound needlessly poetic when an interviewer asks something like this.

Chocolate♦

64.4k5 gold badges97 silver badges201 bronze badges

answered Oct 7, 2016 at 6:43

narutonaruto

289k12 gold badges306 silver badges584 bronze badges

As naruto mentioned, «演奏する» sounds like a perfectly reasonable candidate, and is not too formal.

Another option is to use the «演» of «演奏»; «演じる». This is however perhaps most commonly used in regards to theatrical pieces, such as opera and plays.

answered Oct 7, 2016 at 6:50

楽器をなにか演奏しますか is what I found in jisho.

answered Nov 29, 2017 at 4:32

shoryuushoryuu

1,4731 gold badge12 silver badges22 bronze badges

3

You must log in to answer this question.

Not the answer you’re looking for? Browse other questions tagged

.

Not the answer you’re looking for? Browse other questions tagged

.

Hey epic gamers, welcome to another incredible article from Bondlingo. Now today we have a very interesting and special article for you, we are going to be discussing all about gaming language in Japanese. This is dedicated to all those gamers out there. We want to make sure that you can enjoy your intense gaming in a Japanese setting too. What better way to immerse yourself in the language while doing something you love.

We are going to look at some of the top vocabulary today that pops up the most throughout most games. This is just an overview but if you have anything specific you want to know about that we haven’t mentioned, please make sure to leave a comment.

Right. Let’s get right into it guys!

Contents

- 1 The Killer gaming Vocabulary

- 2 a game; a match

- 3 Learn Japanese Kanji with BondLingo?

- 4 Study in Japan?

- 4.1 Recommend

- 4.2 Related

The Killer gaming Vocabulary

Right we are now going to break down and contextualise all of the killer gaming vocabulary in Japanese that you are going to need to know to own some noobs in your gaming exploits. Lets start with this word first:

レベル

Reburu

Level

So as you can imagine you can use this in numerous ways, you could ask what level is your competitor on or what level they are. Let’s look at the next.

ラスボス戦

Rasubosu Sen

last boss battle

This will be useful to know when you are about to lock horns with the final boss in your game. So as you can see we have “rasubosu” which means “last boss” and then “sen” which means battle.

雑魚

ざこ

Zako

You know those pesky little mobs that get in your way all the time? Yeah, this is how you talk about those creatures.

試合

しあい

shiai

a game; a match

This is one of the most essential in todays list. You can use this to ask when the match or game will being and also what type your friends or competitors are looking to play.

経験値

けいけんち

keikenchi

EXP

Ah, the integral XP bar, oh the hours spent grinding to reach the top levels! This is how you can refer to XP in your games.

攻撃

こうげき

kougeki

Attack

This is the word for attack, certainly an absolute necessity in any violent gaming ventures. Whether its attacking a city or an enemy, you can use kougeki to say “attack”

防御

ぼうぎょ

bougyo

Defense

Now you can’t have a good attack without a good defense, these two go hand in hand.

相手

あいて

aite

opponent

Whether your facing off against a 4 armed titan or an evil badger, you can use the word aite to mean “opponent”

必殺技

ひっさつわざ

hissatsuwaza

most powerful attack

Are you ready to unleash your most powerful attack? If you are looking to finish your enemy and have saved up enough stamina to unleash your ultimate technique, you can say, “hissatsuwaza“ to describe your final / ultimate attack.

シーン

Sheen

Cutscene

Ah the pesky cut scene, if you can’t skip this then unfortunately your going to have to endure without some intense gaming for the time being. TO be fair, sometimes the story’s from certain cut scenes are awesome and can get you hyped for the next level.

ポーズ

Poozu

Pause

Husband, wife, mum or dad calling you down for dinner? Time to pause the game. Looking to rest those thumbs for a while? Looks like a pause is your best option herer. For this you can say: “Poozu“

メニュー

Menyuu

Menu

This word has to be included in our list as this is your access point into the game itself. It’s pretty easy to remember as its very close to the English “menu”

設定

Settei

Settings

Lastly we have “settings” this is where you can change the language of your game so if you want to change something into Japanese, head here first. There can be a lot of difficult kanji here too so make sure to brush up on that too.

So there we have it guys, make sure to get all of this vocabulary into your anki system and try and make as many examples sentences as you can to help retain the vocabulary. Obviously, the more gaming that you do with native Japanese speakers, the better you will become with the language. You will also get more confident with speaking and interaction too so that’s why its definitely something that we encourage.

Okay all you gamers we really hope that you have enjoyed today’s special gaming article from us. If you have any questions at all or any more ideas for content that you would like us to cover, please do not hesitate to get in touch as we always live to hear from you guys. We hope you are all doing well with your studies and stay tuned for more articles coming soon.

Learn Japanese Kanji with BondLingo?

Study in Japan?

Recommend

-

#1

In a story of the Washington Post : In Japan, a campaign against high heels targets comformity and discrimination,

there are sentences as follows.

«I want to stop this culture of requiring women to wear high heels and pumps at work,» the former model wrote,

«Why do we have to work with our feet injured while men are wearing flat shoes?»

From that tweet, a movement was born, chrstened #KuToo in a nod to the #MeToo movement, the phrase a play on

the Japanese word kutsu, meaning shoes, and kutsu, meaning pain.

Question) Would you please explain the sentence underlined grammartically, especially the phase a play on the Japanese

word? Does the phrase refer to a play on the Japanese word? I can’t find the main verb in the sentence.

Thank you.

Kazu

-

#2

The main verb is ‘was’ in ‘was born’. The words from ‘the phrase’ to the end are a verbless clause, that is a subject ‘the phrase’ and an implied verb ‘being’ before the predicate. You could add ‘being’. Simpler examples of this structure:

She stood in the doorway, her arms folded. [subordinate clause, meaning: her arms are folded]

Hands on hips, she stood in the doorway.

-

#3

the phrase a play on the Japanese word

The phrase «KuToo» is a play on (sounds like) a Japanese word «kutsu»(靴) («shoes») and another Japanese word «kutsu» (苦痛) («pain»). Since Japanese has no «tu/too» syllable, Japanese speakers will pronounce «KuToo» the same as «kutsu».

But it is written (in English letters) «#KuToo» so it looks similar to the famous «#MeToo» movement.

Last edited: Jun 14, 2020

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Japanese wordplay relies on the nuances of the Japanese language and Japanese script for humorous effect. Double entendres have a rich history in Japanese entertainment (such as in kakekotoba)[1] due to the language’s large number of homographs (different meanings for a given spelling) and homophones (different meanings for a given pronunciation).

Kakekotoba[edit]

Kakekotoba (掛詞) or «pivot words» are an early form of Japanese wordplay used in waka poetry, wherein some words represent two homonyms. The presence of multiple meanings within these words allowed poets to impart more meaning into fewer words.[1]

Goroawase[edit]

Goroawase (語呂合わせ, «phonetic matching») is an especially common form of Japanese wordplay, wherein homophonous words are associated with a given series of letters, numbers or symbols, in order to associate a new meaning with that series. The new words can be used to express a superstition about certain letters or numbers. More commonly, however, goroawase is used as a mnemonic technique, especially in the memorization of numbers such as dates in history, scientific constants and phone numbers.[2]

Numeric substitution[edit]

Every digit has a set of possible phonetic values, due to the variety of valid Japanese kanji readings (kun’yomi and on’yomi) and English-origin pronunciations for numbers in Japanese. Often, readings are created by taking the standard reading and retaining only the first syllable (for example, roku becomes ro). Goroawase substitutions are well known as mnemonics, notably in the selection of memorable telephone numbers used by companies and the memorization of numbers such as years in the study of history.

Mnemonics are formed by selecting a suitable reading for a given number; the tables below list the most common readings, though other readings are also possible. Variants of readings may be produced through consonant voicing (via a dakuten or handakuten) or gemination (via a sokuon), vowel lengthening (via a chōonpu), or the insertion of the nasal mora n (ん).

| Number | Kun’yomi readings | On’yomi readings | Transliterations from English readings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | maru, ma, wa | rei, re | ō, zero, ze |

| 1 | hitotsu, hito, hi | ichi, i | wan |

| 2 | futatsu, fu, futa, ha | ni, ji, aru | tsu, tsū, tū |

| 3 | mittsu, mi | san, sa, za | su, surī |

| 4 | yon, yo, yottsu | shi | fō, fā, ho |

| 5 | itsutsu, itsu, i | go, ko | faibu, faivu |

| 6 | muttsu, mu | roku, ro, ri, ra, ru,[3] ryū | shikkusu |

| 7 | nana, nanatsu, na | shichi | sebun, sevun |

| 8 | yattsu, ya | hachi, ha, ba | eito |

| 9 | kokonotsu, ko | kyū, ku | nain |

| 10 | tō, to, ta | ju, ji | ten[a] |

General examples[edit]

- 16 can be read as «hi-ro», Hiro being a common Japanese given name. 16 is also a common age for anime and manga protagonists[citation needed] (i.e. heroes).

- 26 can be read as «fu-ro» (風呂), meaning «bath». Public baths in Japan have reduced entry fees on the 26th day of every month.[4]

- 29 can be read as «ni-ku» (肉), meaning «meat». Restaurants and grocery stores have special offers on the 29th day of every month.

- 39 can be read as «san-kyū», referring to «thank you» in English.

- 428 can be read as «shi-bu-ya», referring to the Shibuya area of Tokyo.

- 526 can be read as «ko-ji-ro» in reference to Sasaki Kojiro, a samurai from the Edo period.

- 634 can be read as «mu-sa-shi». The Tokyo Skytree’s height was intentionally set at 634 meters so it would sound like Musashi Province, an old name for the area in which the building stands.[5]

- 801 can be read as «ya-o-i» or yaoi, a genre of homoerotic manga typically aimed at women.

- 893 can be read as «ya-ku-za» (やくざ) or «Yakuza».[6] It is traditionally a bad omen for a student to receive this candidate number for an exam.[citation needed]

- 4649 can be read as «yo-ro-shi-ku» (よろしく), meaning «best regards».

As mnemonics[edit]

1492, the year of discovery of America, can be read as «i-yo-ku-ni» and appended with «ga mieta» to form the phrase «Alright! I can see land!» (いいよ!国が見えた!). Additionally, «i-yo-ku-ni» itself could simply be interpreted as «alright, country» (いいよ、国). The alternative reading «i-shi-ku-ni» is not typically associated with a particular meaning, but is used to memorize the year.

23564, the length of a sidereal day (23 hours, 56 minutes, 4 seconds), can be read as «ni-san-go-ro-shi», which sounds similar to «nii-san koroshi» (兄さん殺し) or in English, «killing one’s older brother».

3.14159265, the first nine digits of pi, can be read as «san-i-shi-i-ko-ku-ni-mu-kou» (産医師異国に向こう), meaning «an obstetrician faces towards a foreign country.»

42.19, the length of a marathon course in kilometres, can be read as «shi-ni-i-ku» (死に行く), meaning «to go to die.»

Popular culture examples[edit]

Anime, manga, and television[edit]

- 152 can be read as «hi-ko-ni», meaning «unofficial» (非公認, hikōnin), and is part of the license plate number of the Machine Itashar in Unofficial Sentai Akibaranger.

- 18782 + 18782 = 37564 can be read as «i-ya-na-ya-tsu + i-ya-na-ya-tsu = mi-na-go-ro-shi» (嫌な奴+嫌な奴=皆殺し, bad person + bad person = massacre).[7][8]

- In Initial D, Rin Hojo’s Nissan Skyline GT-R R32 has the number 37654 on its license plate, befitting his nickname of «Shinigami».

- 315, or «sa-i-go», is used as a transformation code in Kamen Rider 555: Paradise Lost due to being pronounced similarly to «Psyga».

- 39 can be read as «za-ku,» referring to the Zaku mecha from the Gundam franchise.[9]

- 428, read as «yo-tsu-ba», can refer to the character Yotsuba Nakano from The Quintessential Quintuplets, who wears T-shirts with that number.

- 4869 can be read as «shi-ya-ro-ku» (しやろく); when «ya» is written small, it becomes «sharoku» (しゃろく), which resembles «Sherlock» (シャーロック, Shārokku). This number is Conan Edogawa’s phone PIN and the name of an experimental drug in Case Closed.

- 56 can be read as «go-mu», meaning «rubber» (ゴム, gomu), referring to One Piece protagonist Monkey D. Luffy’s elastic abilities.

- 59 can be read as «go-ku» and is sometimes used in reference to Goku from Dragon Ball.

- 63 can be read as » mu-zan» or «miserable», which refers to Muzan Kibutsuji, the main antagonist of Demon Slayer. The official Demon Slayer Twitter account refers to June 3rd as «Muzan Day».

- 723 can be read as «na-tsu-mi» or Natsumi and is commonly used in Sgt. Frog to symbolically refer to the character Natsumi Hinata.

- July 23rd (7/23) is the birthday of Date A Live character Natsumi Kyouno.

- 819 can be read as «ha-i-kyū» (排球), meaning volleyball. The community around the anime series Haikyu!! considers 19 August (8/19) to be «Haikyu!! Day».

- 86239 can be read as «hachi-roku-ni-san-kyū», and was used in Initial D as the number on the license plate of a Toyota 86. It translates to «thank you, eight-six».

- 89 years can be read as «ya-ku-sai». This is homophonous with the Japanese word for «calamity» (厄災 yakusai), being a fitting age for the JoJolion character Satoru Akefu, who has a calamity related ability.

- 913 can be read as «ka-i-sa», as in Kamen Rider Kaixa, hence it being the transformation activation code.

- An anagram of this is 193, read as «i-ku-sa» (as in Kamen Rider IXA), which serves as the code to activate Rising Mode.

Music[edit]

- 382 can be read as «mi-ya-bi» (みやび), used by Miyavi.

- 39 can be read as «mi-ku», usually in reference to the Vocaloid character Hatsune Miku.[9]

- 610 can be read as «ro-ten» or «rotten», and is often used on merchandise of the rock band ROTTENGRAFFTY.

- 616 can be read as «ro-i-ro», referring to lowiro, the developer and publisher of the rhythm game Arcaea.

- 712 can be read as «na-i-fu» (i.e. knife), and is used in the Shonen Knife album 712.

- 75, read as «na-ko», is used by Nako Yabuki in her Instagram and Twitter handles.

- 96 can be read as «ku-ro» meaning «black», as in 96猫 («kuroneko»; «black cat»). 96猫 is a popular Japanese singer who covers songs on Niconico, and provides the singing voice of Tsukimi Eiko in Ya Boy Kongming!.

Video games[edit]

- 193, when read as «i-ku-sa» and interpreted to mean «Iku-san», can refer to Touhou Project character Iku Nagae, or IJN submarine I-19 in Kantai Collection.

- 2424 can be read as Puyo Puyo. This numerical correspondence has been used and referenced ever since the series’ debut, and has also been used in various teasers for some of the games. The series celebrated its 24th anniversary in 2015.

- 283 can be read as «tsu-ba-sa» (翼), meaning «wing». This is used for the name of the 283 Production agency in THE iDOLM@STER: Shiny Colors.

- 315 can be read as «sa-i-kō» (最高), meaning «highest», «supreme», or «ultimate». This is used as the name for 315 Production in The Idolmaster SideM, where the idols under the label use «saikō» as a rallying chant.[10][11]

- 34 is a frequent target of goroawase in the mystery franchise When They Cry, often being the name of the culprit or an accomplice, such as Miyo (三四) in Higurashi When They Cry, Sayo (紗代) in Umineko When They Cry, and Mitsuyo in Ciconia When They Cry.

- 346 can be read as «mi-shi-ro», meaning «beautiful castle». This is used for the name of 346 Production in THE iDOLM@STER: Cinderella Girls.

- 51 can be read as «go-ichi». These two numbers are the latter part of «SUDA51», the alias of Goichi Suda.

- 573 can be read as «ko-na-mi» and is often used by Konami; for example, it is used in Konami telephone numbers and as a high score in Konami games, as well as in promotional materials and sometimes as a character name.[clarification needed]

- .59 can be read as «ten-go-ku» (天国), meaning «heaven» (an example being the song «.59» in Beatmania IIDX 2nd Style and Dance Dance Revolution 4thMix).

- 765 can be read as «na-mu-ko» or Namco. Derivatives of this number can be found in dozens of Namco-produced video games. It was also the central studio of The Idolmaster and its sequels.

- After merging with Bandai, their goroawase number became 876 (ba-na-mu); the handle of Bandai Namco Games’ Japanese Twitter account is «@bnei876».[12]

- 86 can be read as «ha-ru» or HAL. HAL Laboratory often puts this number somewhere in the video games it creates as parts of secrets and easter eggs, most notably in the Kirby series.

- In Pokémon Sword and Shield, all Gym Leaders and some extra characters have a three-digit jersey number that relates to their name, role, or typing they specialize in. For example, Opal has the jersey number 910, which can be read as «kyu-to» or cute, relating to her specialization in Fairy-type Pokémon.

Other[edit]

- 15 can be read as «ichi-go» and is commonly used to refer to strawberries («ichigo»). It can also mean «strawberry face», a term used to describe equipping the front end of a Nissan Silvia (S15) onto another S-chassis car.[13]

- 23 can be read as «ni-san». Car manufacturer Nissan frequently enters cars with the number 23 into motorsports events.

- 2434 can be read as «ni-ji-san-ji», which refers to the virtual YouTuber agency Nijisanji. Some Japanese members of the company use this number in their Twitter handles.

- 2525 can be read as «ni-ko-ni-ko» (ニコニコ) and refers to Niconico, a Japanese online video platform. Its «mylists», which function similarly to lists of bookmarks, are limited to 25 per user.

- 510, read as «go-tō», is used by professional wrestler Hirooki Goto in his Twitter handle.

- 563 can be read as «ko-ro-san» (ころさん); amounts of 563 yen are commonly donated to virtual YouTuber Inugami Korone of Hololive Production, who is sometimes referred to as «Koro-san».

- Hololive founder Motoaki «YAGOO» Tanigo’s nickname is occasionally represented with the number 85 («ya-go») or 850 («ya-go-ō»).[14]

- 69 can be read as «ro-ki», as in Hi69 («Hiroki»), one of the ring names of professional wrestler Hiroki Tanabe.

See also[edit]

- Japanese rebus monogram

- Rebus § Japan

- Tetraphobia

- Word play

Notes[edit]

- ^ The reading ten is more commonly achieved by reading the decimal point as ten (点), meaning «point».[citation needed]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Backhaus, Mio; Backhaus, Peter (27 May 2013). «Oyaji gyagu, more than just cheesy puns». The Japan Times. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ «Goroawase: Japanese Numbers Wordplay». Tofugu. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

The idea is that you can basically use any of these sounds associated with any of these letters to create mnemonics to help someone to remember a phone number.

- ^ Ptaszynski, Michal. «PUNDA Numbears: Proposal of Goroawase Generating System for Japanese». Academia.

The reading ri is referred to as the number «six».

- ^ 埼玉県. «生活衛生営業/お風呂の日(毎月26日)は銭湯へ» (in Japanese). Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ Kyodo News, «Tower’s developers considered several figures before finally settling on 634», Japan Times, 23 May 2012, p. 2

- ^ «What is the origin of yakuza?». www.sljfaq.org. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ 弁護士のブログ. «弁護士のブログ — 「18782(嫌な奴)」+「18782(嫌な奴)」=「37564(皆殺し)」の波紋――過剰反応では?» (in Japanese). Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ «【嫌な奴+嫌な奴=皆殺し】とはどういう意味ですか? — 日本語に関する質問». HiNative (in Japanese). Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ a b «3/9 Marks Happy «Miku» & «Zaku» Day In Japan, Fan Artists Mark The Occasion». Crunchyroll. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ 315!!の日☆

- ^ 315 Production

- ^ «バンダイナムコエンターテインメント公式». Twitter (in Japanese). Retrieved 4 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Strawberry Fields: A Well-Dressed S-Chassis Slider». Speedhunters. 21 April 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ «【Baseballお知らせ #1Baseball】10月3日(日)は冠協賛試合『hololive dayBaseball』始球式にはカバー株式会社代表取締役社長「谷郷元昭」が登板いたします». Twitter (in Japanese). Retrieved 4 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

By

Last updated:

December 23, 2022

Who doesn’t love playing a good game?

Believe it or not, games can also be great teachers.

Learning with games—especially word games—is an amazing way to learn Japanese.

We have put together a list of some seriously awesome, super useful and free Japanese word games to help you increase your vocabulary, sharpen your Japanese alphabet knowledge and improve your overall Japanese fluency.

Contents

- How Japanese Word Games Can Help You Learn Japanese

-

- Fun and educational

- Hone in on specific skills

- Build your vocabulary

- Our Favorite Free, Online Japanese Word Games

-

- 1. しりとり — Taking the End a.k.a. “Shiritori”

- 2. Japanese Word Bingo

- 3. Tanoshii Japanese Word Games

- 4. Digital Dialect’s Japanese Word Games

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

How Japanese Word Games Can Help You Learn Japanese

Fun and educational

Playing games and using other entertaining learning methods makes learning a new language fun, rather than a chore.

Let’s be real here, learning a language can sometimes be a pain rather than an exciting adventure.

Keep things playful and fresh! Play a game or two! Binge watch a Japanese drama!

Throwing some fun into your study session can keep it fresh and reinforce your learning in a way that does not feel like learning.

Hone in on specific skills

Many of these games focus on memorizing kanji and improving listening skills.

These aspects of Japanese are incredibly important for improving fluency!

Build your vocabulary

Whether you are a beginner Japanese learner or the best of the best at this language, you are bound to run into vocabulary words that will turn you for a loop.

Japanese word games can help you memorize difficult words, brush up on words you may have forgotten and reinforce your growing vocabulary bank.

Our Favorite Free, Online Japanese Word Games

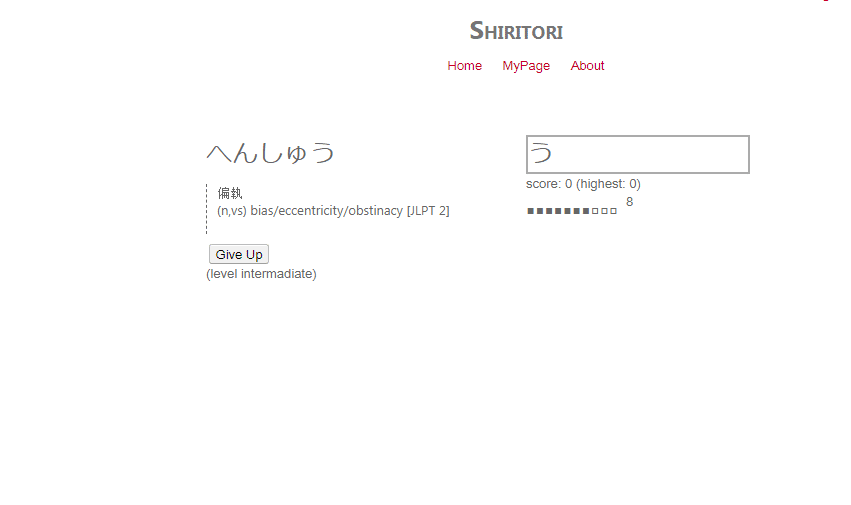

1. しりとり — Taking the End a.k.a. “Shiritori”

しりとり is a classic Japanese word game that is super popular in Japan. To play, you must come up with a word that begins with the last character of the previous word.

Before you begin, you are required to choose your learning level, ensuring the vocabulary that appears will be geared towards your level.

Every word is shown with its hiragana/katakana and kanji, JLPT level and definitions.

If you fail to write in the next word on time, the game presents you with possible words you could have used, along with their definitions. It is a fantastic way to build your vocabulary!

The game even allows you to log in with your Gmail account for detailed records of your past games if you want to visualize your progress.

Since you may need to type in Japanese, it would be wise to have a romanji-to-hiragana converter handy as well as a digital Japanese keyboard.

If you have the chance to play the game analog-style with a native speaker, do it!

When you play with two or more people, take turns saying words. If someone cannot figure out a new word, they and are automatically booted from the game.

The premise and rules of the game are simple, whether you are playing against a computer or a real person:

- Only nouns are allowed.

- The character ん is not permitted, as no Japanese word starts with it, making it impossible to continue the game. In some variations of しりとり, accidentally using a word with ん means forfeiture of the game.

- No words can be repeated during a single game.

- Optional: Pronouns and names of places may be permitted.

- Optional: Words can only be part of a particular genre, such as nature or science.

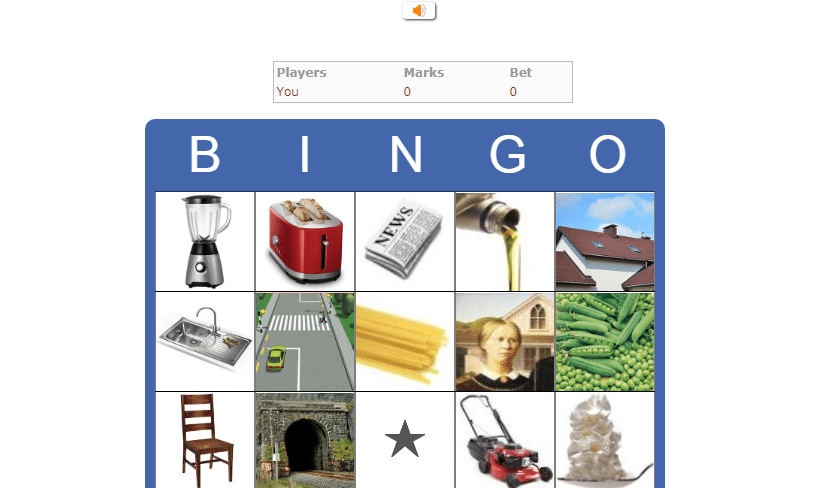

2. Japanese Word Bingo

Everybody has played Bingo before, right?

In case you have not, the rules are simple: When a word is called out, you mark the corresponding space on your Bingo sheet. When you have five spaces in a row marked, you win!

This Japanese word game is a simple version of Bingo, in which you must match the spoken Japanese word with its image at increasing speeds. Just click on the audio button and listen up!

Stay sharp, though: Once you start the game, the audio will read words at short intervals. If you have an image to match the word, click on it. If you do not, wait for the next.

No alphabets or written Japanese is used in this game. It is all audio and imagery, which is ideal for perfecting listening skills. You will also be improving vocabulary recognition by associating spoken words with images.

Any level of learner can play this game, but complete beginners may find it a bit too difficult since there is no writing to rely on.

There is also no way to check what the words mean, so if you find yourself struggling, I recommend that you spend one round simply writing down words you are unfamiliar with and looking them up.

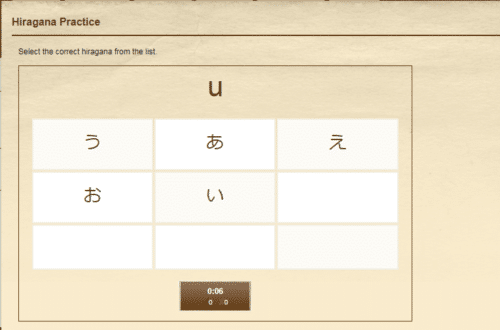

3. Tanoshii Japanese Word Games

Are you a fan of options? So am I! That is why I love this multi-level option-packed resource from Tanoshii Japanese.

On top of offering a Japanese online dictionary, lessons, forums and additional Japanese language-learning resources, this site also has some seriously fun practice games available to play for free.

You can easily improve your reading, listening, writing and speaking skills all in one place. You also have the option to focus on hiragana, katakana, kanji or vocabulary words in either multi-game or single-game levels.

To play, select which alphabet you want to focus on, or choose vocabulary. Then, choose between reading, writing or speaking practice and select your game.

There are matching games, stroke order games, flashcards and more. For most of the alphabet games, you can choose to play based on characters you already know or characters you are currently learning.

To top it all off, you can also select how long you want the game to last.

Beginner, intermediate and advanced students can all gain something from this interesting lesson-based word game.

4. Digital Dialect’s Japanese Word Games

Tanoshii Japanese sure had a lot of options, but this massive flash game section from Digital Dialects really takes the cake when it comes to variety.

This site offers over 20 different word games that focus on improving Japanese listening, reading and speaking skills.

The options are rich in variety and include:

- Katakana, hiragana and kanji games

- Matching and memory games

- Scrabble-like games that focus on vocabulary

- Grammar- and phrase-association games

- Audio and visual options

- After-game quizzes for proficiency

The animations are a little low-budget and cheesy, but if you can get past the corniness you will certainly benefit from these games.

While all levels of Japanese learners can use this site, you may have to search around for a game that fits your particular level.

Like what you see? Digital Dialects also offers weekly parallel text e-books with audio to try out for free.

How rad are these Japanese word games?

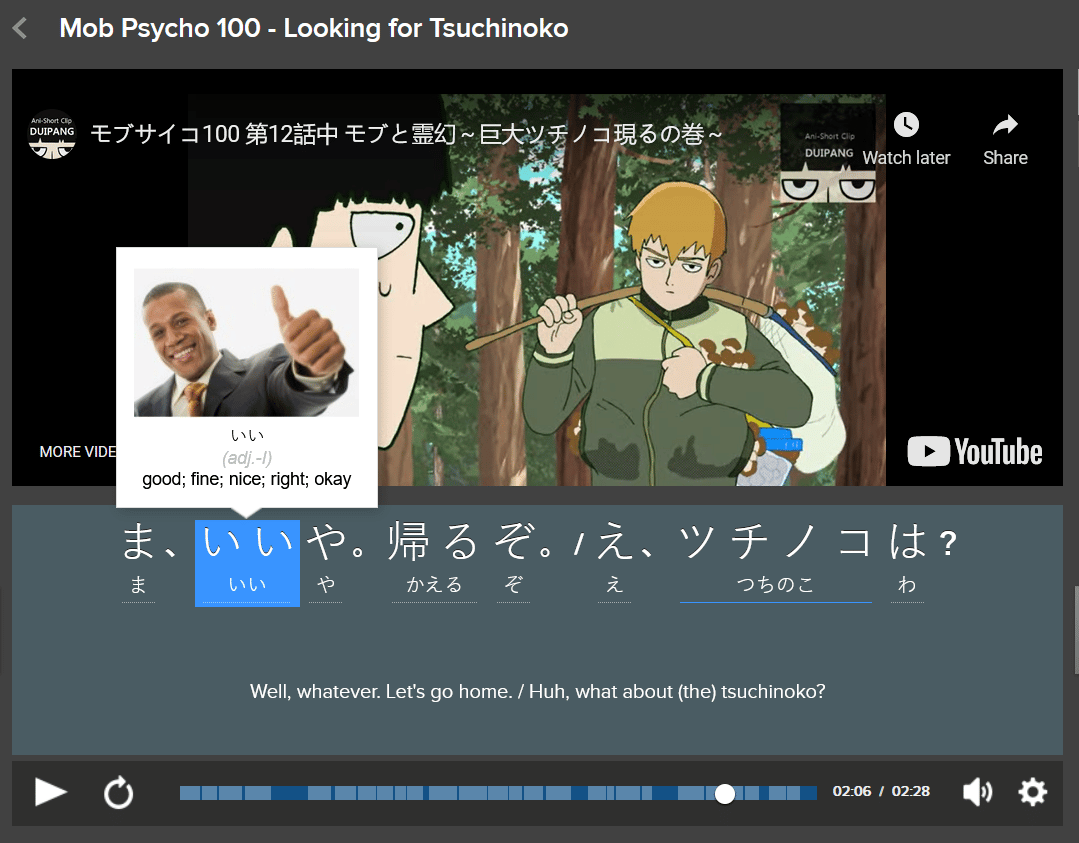

To keep growing your vocabulary, make sure you add some authentic content to your studies. You might learn new words with these games, but you’ll also want to know how to actually use them when the time arises.

Use a program like FluentU to help you retain new vocabulary through immersive content like movie clips, music videos, vlogs and more. You can search for the terms you pick up from word games to find Japanese media clips that mention them, then create multimedia flashcard decks for extra practice. Flashcards can, in turn, be reviewed through personalized quizzes that adapt to your learning speed.

Spicing things up with word games will push you forward on your Japanese language-learning journey—in a fun and engaging way.

Good luck with your fluent future!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Emily Casalena is a published author, freelance writer and music columnist. She writes about a lot of stuff, from music to films to language.