Gender-inclusive language isn’t typically something you learn in school, but its use is incredibly important to make life easier for nonbinary peers.

There are ways to practice gender-inclusive language beyond just respecting gender-neutral pronouns. For instance, replacing “ladies and gentlemen” with “everybody” helps include people who do not identify as ladies or gentlemen.

“Using gendered terms — such as “ladies [and] gentlemen” — is highly presumptuous, especially in today’s society, in which many persons are aware that they don’t identify as male or female and therefore are uncomfortable with this type of language,” Dara Hoffman-Fox, LPC, explains.

To help our nonbinary friends feel more included and safe around us, here are four more ways to practice gender-inclusive language:

Refrain from defaulting to «-man» in descriptors, i.e. “postman.”

Remove gendered language — like using “postman” as the default word rather than “postal worker” — from everyday speech. By not using a word ending in “-man” as the default phrase for a descriptor, we can normalize the idea that anyone can perform a job, regardless of their gender identity.

“When we speak about ‘mankind’ or ‘the achievements of man,’ what we’re doing is confirming the subconscious bias that men are intellectually, morally, and physically superior to women, which is clearly untrue,” Sam Dowd, a British didactics expert from language-learning app Babbel, says. “By using such language, we exclude women — and, for that matter, nonbinary people — from history.”

We can avoid erasing women and nonbinary people from everyday conversations by using gender-neutral descriptions. Some examples include:

- Folks, folx, or everybody instead of guys or ladies/gentleman

- Humankind instead of mankind

- People instead of man/men

- Members of Congress instead of congressmen

- Councilperson instead of councilman/councilwoman

- First-year student instead of freshman

- Machine-made, synthetic, or artificial instead of man-made

- Parent or pibling instead of mother/father

- Child instead of son/daughter

- Kiddo instead of boy/girl

- Sibling instead of sister/brother

- Nibling instead of niece/nephew

- Partner, significant other, or spouse instead of girlfriend/boyfriend or wife/husband

- Flight attendant instead of steward/stewardess

- Salesperson or sales representative instead of salesman/saleswoman

- Server instead of waiter/waitress

- Firefighter instead of fireman

“Some people may argue that such concerns are unimportant, but if you consider that language is the primary filter through which we perceive the world, it’s obvious that it affects how we relate to and make judgments about one another,” Dowd tells Teen Vogue. “Until now, history has been written and told by men, to the detriment of others. Part of any attempt to create a society in which all people — regardless of gender, sexuality or race — have equal opportunities and freedoms is to use language that no longer excludes certain groups or creates unconscious bias.”

Just because a nonbinary person isn’t present doesn’t make it OK to use binary language.

Many nonbinary people aren’t as vocal about their identity and pronouns as others, and you can’t know someone’s gender by looking at them, Hoffman-Fox stresses. Nonbinary people reflect a wide variety of gender expressions and are sometimes still identified as male or female because they don’t present as androgynous.

“It’s fairly common for people to assume that a nonbinary person isn’t in the room,” Hoffman-Fox said. “The truth is, there is no way someone could know that, unless they have had conversations with every person in the vicinity and have asked them if they use binary terms to describe themselves.”

Hold those around you accountable.

Don’t be afraid to correct those around you, such as your classmates and even teachers, about using exclusive, gendered language, but do understand not everyone receives criticism in the same way.

“Some people will be comfortable with being very direct, like: ‘Excuse me, but when you used ladies to describe our friend group, it leaves out those who are uncomfortable with being gendered as female,’” Hoffman-Fox tells Teen Vogue. “Some may want to take a more subtle approach, such as repeatedly using a gender-neutral term within earshot of the person using binary language.”

Pay attention to which responses work better for certain people.

“Depending on the situation, you can address the situation with the person publicly or privately, in person or through a message,” Hoffman-Fox adds. “Try to keep it as simple as possible, explaining briefly what binary language is and how it can often result in people feeling invisible.”

Remember that binary language also harms cisgender and binary transgender people.

Nonbinary people aren’t the only ones hurt by binary language. Binary transgender people (or trans people who aren’t nonbinary) and cisgender people are also affected — and often harmed — by the gender binary and how ingrained it can be in our language. For instance, many women prefer not to be lumped into a group of “ladies” because of society’s expectations of how a lady should act.

“There are people who aren’t nonbinary who are uncomfortable with binary gendered terms, thanks to these terms also being experienced as stereotypical,” Hoffman-Fox says. “Shifting to gender-neutral language is of benefit not only to those who are nonbinary but to many others in society who feel that binary terms are inaccurate ways of describing them.”

| Gender neutral language |

|

Gender neutral language in English is easier than gender neutral language (also called gender inclusive language) in many other languages, because its grammatical gender is less pervasive than in, say, German or French. See the main article on gender neutral language for general reasons to use neutral language, common problems in using it, and its use for nonbinary people.

History[edit | edit source]

Although English has grammatical gender, it’s only a vestige of what it once had. Old English once had grammatical gender for inanimate objects, but this practice started to disappear in the 700s, and vanished in the 1200s. The population of England at that time spoke several languages, and the same inanimate objects had different genders in those different languages. They may have stopped using that part entirely just to make it simpler. English stopped using grammatical gender for inanimate objects, but it still uses grammatical gender for people and personal pronouns.[1] There is enough to make a challenge for nonbinary people who don’t want gendered language to be used for them.

Gender-neutral language has become common in English today largely thanks to the pioneering work by feminists Casey Miller and Kate Swift. During the 1970s, they began the work of encouraging inclusive language, as an alternative to sexist language that excludes or dehumanizes women. Miller and Swift wrote a manual on gender-neutral language, The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing (1980). Miller and Swift also proposed a set of gender-neutral pronouns, tey, although they later favored singular they, or he or she.[2] There are several books on gender-neutral English, such as Rosalie Maggio’s book The Nonsexist Word Finder: A Dictionary of Gender-Free Usage (1989).

Words and alternatives[edit | edit source]

This is a list of both standard (dictionary) and non-standard (created) terms and pronouns to include nonbinary identities. It should be noted that while some are genderless or third gender, others are multigender. Terms will be marked with the implied gender identity when possible.

Pronouns[edit | edit source]

See main article at English neutral pronouns.

Titles[edit | edit source]

For gender-neutral replacements of titles like Ms and Mr, see main article at Gender neutral titles.

Honorifics[edit | edit source]

Ma’am/Sir[edit | edit source]

Standard English doesn’t have a gender neutral word that’s used in the same way as Ma’am and Sir — a formal form of address used in some places to show respect, and commonly required for use by customer service professionals. People have created some words to fill this lexical gap, but they remain uncommon words. People have also suggested using other words in place of Ma’am and Sir, but they tend to fail the tests of formality and simplicity that customer service professionals (and their managers) apply to such usage.

- Common words

- Friend: Neutral, informal.

- Tiz: A gender-neutral replacement for ma’am/sir, from Citizen.

- Citizen; neutral.

- Comrade; neutral, not suitable for all situations due to leftist connotations, which may be triggering for survivors of certain ‘socialist’ regimes.

- Friend; neutral, very informal.

- Laddam; queer, a mix of Lad and Madam.

- Mezz; pronounced [mɛz].[3]

- Mir; queer, a mix of Sir and Madam.

- Mirdam; queer, a mix of Sir and Madam, although it still sounds similar to Madam.

- Mistdam; queer, a mix of Mister and Madam.

- Mistrum: queer; a neutral alternative to Mister and Mistress.

- Pe’n: Neutral, short for «person», pronounced «pen»

- Sa’am; a mix of sir and ma’am. Sounds like a masculine leaning name.

- Sir; neutral, Sir is used neutrally in the military, although this doesn’t work as well outside of that.

- Sir’ram; queer, a mix of Sir and Ma’am.

- Shazam. Neutral, coined by a highschool student wishing to address a nonbinary teacher with a formal term of respect.[4]

- Tiz; neutral, short for citizen.

- Zam. Neutral, based on shazam, coined by Arin Wolfe.[5]

- Ser; neutral, based on Final Fantasy XIV’s usage for both male and female knights of Ishgard.

Common nouns[edit | edit source]

| Type of common noun | Feminine | Masculine | Gender inclusive (could be masculine or feminine) | Specifically nonbinary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young person | Girl, maiden | Boy, youth | Child, kid, infant, teen, teenager, tween, young person, youth | Enby |

| Adult person | Woman, gal, lady | Man, gentleman, lad | Adult, gentlebeing, gentleperson, grownup | Enby, enban |

| Person of any age | Female | Male | Being, human, human being, one, person, somebody, someone | Enby |

(Note that using «male» and «female» as nouns for people, e.g. «my dentist is a male», is seen as dehumanising in English, and in particular «female» as a noun is considered sexist.)

(Note 2: Some nonbinary people dislike «enby» and feel it is infantilizing.[6])

Family and relationship words[edit | edit source]

See also: family and intimacy.

Parent[edit | edit source]

Parents as in the formal words mother or father, or the informal mama or dada. Gender-neutral and gender-inclusive words for a parent of any gender, or non-standard specifically nonbinary, queer, or genderqueer words.

- Common words

- Parent: Neutral, formal[7]

- Baba. «Neutral, based on mama and dada. (Note, baba means dad in some languages and grandmother in others.)»[7]

- Bibi. «Queer, based on the B in NB [nonbinary], similar to mama and papa/dada.»[7]

- Cenn. «Neutral, short for cennend,» which see.[7]

- Cennend. «Neutral, Old English (Anglo-Saxon) meaning parent.»[7]

- Da. «Queer mixture (note: sounds like Ma, Pa). However, «Da'» is used in some areas of Britain and Ireland as a shortened form of «Dad».

- Dommy. «Queer, mixture of mommy and daddy (note: sounds like Dom/me, a BDSM term).»[7]

- Mada. Queer, mixture of mama and dad.

- Maddy. «Queer, mixture of mummy/mommy and daddy.»[7] Note: Sometimes used to mean a trans woman who has children.[8]

- Moddy. «Queer, mixture of mommy and daddy.»[7]

- Moppa / Mopa. A mix of mommy and papa.[9]

- Muddy. «Queer, mixture of mummy and daddy.»[7]

- Nibi. «A mix of bibi and nini.»

- Nini. «Queer, based on the N in NB, similar to mama and papa/dada.»[7]

- Non. Follows a similar pattern (CvC) to Mom or Dad, could be short for «nonbinary».

- Nonny. Based on the N in NB, similar to Mommy or Daddy, generally used when a child is referring to their nonbinary parent.

- Numa. A nickname that was repurposed to be a parent name. Coincidentally like a combination of Nonbinary Mumma.

- Par. «Neutral, short for parent.»[7]

- Pare: Short for parent. Can call to mind an au pair, which is a live in childcare worker (usually a woman but not always). The term means equal to, implying that one is equal to a mother or father. Also similar to père, or the French word for father. Other associations include pear (the fruit) or pair, as in the other half of a couple.

- Parental Unit (PU). Neutral, informal, humorous, possibly disrespectful. Used by the alien family in Coneheads, and taken up by popular culture.[7]

- Per. «Neutral, short for parent.»[7] (See also: per pronouns and Pr title.)

- Ren. Derived from «parent.» Gender-neutral. The equivalent to mommy or daddy is «renny.» Coined or popularized by Katie Hall in 2017.[10]

- Rent. Short form of parent.

- Zaza. «Queer, based on mama and papa/dada.»[7][8]

- Zither. «Queer, based on mother and father. (Note, zither is also the name of a musical instrument.)»[7]

Child[edit | edit source]

Some of these gender-inclusive or gender-queer words refer only to relationship (as in daughter, son, or offspring), others only to age (girl, boy, or young one), and some to both (children).

- Common words

- Baby: Standard neutral word for very young offspring or very young people.

- Child: Standard gender neutral word for a young person or an offspring. Implied age isn’t adult, but may be.

- Kid: Standard informal gender neutral term for young children or young offspring.

- Bitsy. Non-standard genderqueer term for a very young person.[7]

- Charge. Standard gender neutral word for a person in the care of another, often one’s child.

- Chitlin. A way of saying child, often[citation needed] used when referring to a nonbinary child. (More commonly means «pig intestines.»)[11]

- Dependent. A person who relies on another— usually a family member who may or may not be their parent— for financial support; this is most often used as a standard gender-neutral word for a child too young to work. Formal.

- Enby. From «NB (nonbinary)», a nonbinary equivalent of the words «boy» and «girl.» However, some adults call themselves enbies.[12]

- Get. Poetic language for offspring.

- Little one. Neutral word for a very young child or young offspring.

- Minor. Standard gender-neutral word for a person under the legal age of consent.

- Nesser. Non-standard genderqueer term for «daughter/son».[7]

- Offspring. Neutral, standard word, but not usually used for people, except in legal language.

- Oldest. Neutral, a way of speaking of one’s offspring by saying «my oldest,» rather than saying «my daughter/son.»[7]

- Second-born. Neutral, a way of speaking of one’s offspring by saying «my second-born,» rather than saying «my daughter/son.» Also works for third-, fourth-, or fifth-born, etc. [7]

- Sprog. Neutral, crude word for a young person.[7][8]

- Youth. Neutral, poetic word for a young person, but usually implied to be male.

- Young. Neutral, standard word for offspring, but not usually used for people («my young.»)

- Youngest. Neutral, a way of speaking of one’s offspring by saying «my youngest,» rather than saying «my daughter/son.»[7]

- Young one. Neutral, poetic. Alternatively: young’un.

- Young person. Neutral, standard, formal.

- Ward. Standard gender-neutral word for a person, usually a child, under the care of an adult, who may or may not be their parent. Formal.

Aunt/Uncle[edit | edit source]

Standard English doesn’t have a gender neutral word for one’s parent’s sibling. People have created some words to fill this lexical gap, but they are still uncommon words.

- Common words

- Auncle: Combination of aunt and uncle.[13]

- Avaunt. It derives from the roots of both «aunt» and «uncle», the anglo-French «aunte» and the Latin «avunculus».

- Bibi. «Queer, based on the B in NB [nonbinary], similar to Titi/Zizi.»[7]

- Cousin. «Neutral, as sometimes people say aunt/uncle for parents’ cousins, or much older cousins.»[7]

- Nibi. Combination of Nini and Bibi, based on NB.

- Entle. «Non-standard alternative that combines the sounds of aunt and uncle in a single word.»[14]

- Nini. «Queer, based on the N in NB, similar to Titi/Zizi.»[7]

- Ommer. Non-standard genderqueer term for «aunt/uncle».

- Oggy. Non-standard genderqueer/nonbinary term for parents sibling.

- Pibling. «Neutral, your parent’s sibling.»[7]

- Titi. «Neutral, from the Spanish for Aunt (Tia) and Uncle (Tio). (however, it is often a diminuative of aunt.) Tie is also gaining popularity the neutral e becoming more prevalent in casual Spanish. «[7] «Titi» also happens to be a vulgar Filipino term for penis.[citation needed]

- Zizi. «Neutral, from the Italian for Aunt (Zia) and Uncle (Zio). (Note: zizi is also a French children’s ‘cute’ word for penis.)»[7]

- Untie/Unty. «Queer, combination of uncle and auntie/aunty.»[7]

Niece/Nephew[edit | edit source]

Standard English doesn’t have a gender neutral word for one’s sibling’s child. People have created some words to fill this lexical gap, but they are still uncommon words.

- Common words

- Nibling: Non-standard gender neutral term for «niece/nephew».[15]

- Chibling. «Neutral, the children of your sibling.»[7]

- Cousin. «Neutral, as sometimes people say niece/nephew for cousins’ children, or much younger cousins.»[7]

- Nespring. A mix of offspring and the Latin word nepos, from which both niece and nephew are derived.

- Niecew. «Queer, mixture of niece and nephew.»[7]

- Nieph. «Queer, mixture of niece and nephew.»[7]

- Niephling. Neutral, mixture of niece, nephew, and sibling. [16]

- Nephiece. «Queer, mixture of nephew and niece.»[7]

- Sibkid. «Neutral, short for sibling’s kid.»[7]

- Niephew. «A mixture of niece and nephew.»[17]

Grandparent[edit | edit source]

Gender-neutral or genderqueer words for grandparent.

- Common words

- Grandparent: Neutral, formal.[7]

- Bibi. «Queer, based on the B in NB, similar to nana and papa.»[7]

- Grandwa. «Queer, based on grandma and grandpa.»[7]

- Grandy.’ «Neutral, short for Grandparent, Grandma or Grandpa.»[7][8]

- Nini. «Queer, based on the N in NB, similar to nana and papa.»[7]

- Gran. Short for grandparent, grandmother, or grandfather.

Sibling[edit | edit source]

Gender-neutral or genderqueer words for sibling.

- Common words

- Sibling: Standard gender neutral term for sister or brother.

- Sib: Short for sibling, equivalent of bro or sis.

- Emmer. Non-standard genderqueer term for sibling.

- Sibster. «Queer, combination of sibling and sister.»[7]

- Sibter. «Queer, combination of sibling and brother.»[7]

Partner[edit | edit source]

Gender-inclusive or genderqueer words for tentative romantic and sexual partners (as in girlfriend, boyfriend, or date) as well as permanent ones (as in wife, husband, or spouse).

Date[edit | edit source]

Gender-neutral and genderqueer words for a non-committed relationship, such as boyfriend, girlfriend, or date.

- Common words

- Date: Neutral, the person you are dating.[7]

- Love/Lover: Neutral, often implies sexual relationship, but simply refers to someone you love/who loves you.[7]

- Sweetie/Sweetheart: Neutral, cheesy or old-fashioned.[7]

- Birlfriend. «Queer, mix of boyfriend and girlfriend.»[7] Birl is also a particular gender identity.

- Boifriend. «Queer, boi is a particular gender identity.»[7]

- Boo. From «beau». Originated as African American slang, but now used more widely.

- Bothfriend. «Queer, for bigender or androgynous people.»[7]

- Boygirlfriend. «Queer, for bigender or androgynous people.»[7]

- Cuddle Buddy. «Neutral, cheesy.»[7]

- Darling. Neutral, a general term of affection, similar to sweetheart but not antiquated.

- Datefriend. «Neutral, the person you are dating, but fitting the boyfriend/girlfriend pattern.»[7]

- Datemate. «Neutral, a rhyming version of datefriend, the person you are dating.»[7][8]

- Enbyfriend. «Queer, based on boyfriend and girfriend. (note: enby comes from NB, non-binary).»[7]

- Feyfriend. Queer, due to the implications of «fey.»[7]

- Genderfriend. «Queer, based on boyfriend and girlfriend.»[7]

- Girlboyfriend. «Queer, for bigender or androgynous people.»[7]

- [name]friend. «Queer, based on girlfriend and boyfriend.»[7]

- Paramour. «Neutral, someone you are having a sexual relationship with.»[7]

- Personfriend. «Neutral, leaning towards queer, based on boyfriend and girlfriend.»[7]

- Theyfriend. «Neutral, based on a combination of pronouns and boyfriend and girlfriend.»

- Joyfriend. «Neutral, cute, based on girlfriend, boyfriend, and theyfriend. [18][19]

Significant other[edit | edit source]

Gender-neutral and genderqueer words for a girlfriend, boyfriend, or partner in a committed relationship.

- Common words

- Beloved: Neutral, one who one loves.

- Partner: Neutral, often (but not necessarily) queer.

- Significant Other (SO): Neutral, quite formal. Implies monogamy.[7]

- Birlfriend. «Queer, mix of boyfriend and girlfriend.»[7] Birl is also a particular gender identity.

- Boifriend. «Queer, boi is a particular gender identity.»[7]

- Boofriend. «Neutral, playing off of ‘Boo’ (above).» Great cute option!

- Bothfriend. «Queer, for bigender or androgynous people.»[7]

- Boygirlfriend. «Queer, for bigender or androgynous people.»[7]

- Companion. «Neutral, reference to Doctor Who’s companions, or Firefly’s Companions.»[7]

- Cuddle Buddy. «Neutral, cheesy.»[7]

- Darling. Neutral, a general term of affection, similar to sweetheart but not antiquated.

- Datemate. Queer, for nonbinary people.

- Enbyfriend. «Queer, based on boyfriend and girfriend. (note: enby comes from NB, non-binary).»[7]

- Feyfriend. Queer, due to the implications of «fey.»[7]

- Genderfriend. «Queer, based on boyfriend and girlfriend.»[7]

- Girlboyfriend. «Queer, for bigender or androgynous people.»[7]

- Imzadi. «Neutral, from Star Trek, a Betazed word similar to beloved.»[7]

- Loveperson. «Neutral, a person that you love.»[7]

- [name]friend. «Queer, based on girlfriend and boyfriend.»[7]

- Other Half. «Neutral, informal, and implies monogamy.»[7]

- Paramour. «Neutral, someone you are having a sexual relationship with.»[7]

- Personfriend. «Neutral, leaning towards queer, based on boyfriend and girlfriend.»[7]

- Signif. Neutral. Slang abbreviation of «significant other.»[20]

- S.O.. Neutral. Widely used abbreviation of «significant other.»

- Soul Mate. «Neutral, slightly cheesy, implies belief in soul mates.»[7] Implies monogamy.

- Steady. «Neutral, as in ‘going steady’ or ‘steady girlfriend/boyfriend’.»[7] Implies monogamy.

- Sweetie. «Neutral, slightly cheesy.»[7]

- Sweetheart. «Neutral, cheesy or old-fashioned.»[7]

Fiancée/Fiancé[edit | edit source]

In addition to the above list of words for significant other.

- Betrothed. «Neutral, formal.»[7] Usually means an arranged marriage.

- Spouse-to-be.

- Intended. Implies intent to marry.

- Epoxi; neutral, from the French ‘époux’ which means husband/spouse.

- Fiancé. While traditionally only used for men, it is becoming more common to use it gender-neutrally, for example: «Matt called his fiancé and told her to come to the office.»[21][22]

Spouse[edit | edit source]

In addition to the above list of words for significant other.

- Spouse. «Standard, neutral, formal.»[7]

- Epox; neutral, from the French ‘époux’ which means husband/spouse.

Other family relationships[edit | edit source]

Gender-neutral and genderqueer words for other kinds of family relationships.

- Godparent. Standard gender neutral term for godfather or godmother.

- Godren

- Grandchild. Standard gender neutral term for grandson or granddaughter.

Boy/Girl

- Enby- From NB or nonbinary

- Neut as in Neutral

- Null gender is null

- Newt another form of neutral/neut

Professions[edit | edit source]

- Bartender or Bar tender. Standard gender neutral term for barman or barmaid.

- Business person. Standard gender neutral term for businessman or businesswoman.

- Clergy member. Standard gender neutral term for clergyman, priest, priestess, and many religious titles.

- Consort. Term for the Queen or Prince Consort, dropping the gendered part.

- Cowhand. Standard gender neutral term for cowboy or cowgirl.

- Comedian. Standard gender neutral term. Although some people use «comedienne» for women, «comedian» is generally considered non-gendered.

- Flight attendant. Standard gender neutral term for stewardess/steward (on a plane).

- Heroix. Proposed nonbinary equivalent to hero or heroine that specifies an individual doing heroic work is nonbinary.

- Horse rider/Equestrian. Standard gender neutral term for horseman or horsewoman.

- -ling. Gender neutral Old English suffix for someone involved in something. Can be used in place of «-man», «-person» or «-woman» as a suffix for occupation, such as «businessling».[23]

- Minister. Standard gender neutral term for priest or priestess.

- Monarch. Standard gender neutral term for a king or queen.

- Monarch’s heir. Gender neutral term for a prince or princess.

- Movie star or TV star. Standard gender neutral terms for «actor»/»actress», although increasingly the word «actor» is being used regardless of gender,[24] including by some nonbinary stars such as Asia Kate Dillon.[25]

- Noble. A nobleman/noblewoman, lord/lady, prince/princess, duke/duchess, or many other noble ranks that lack specific gender neutral titles.

- Prime. Derived from Latin. Gender Neutral term for a prince or princess.

- Princexx/Princex/Prinx/Prin/Prinxe/Princet/Princette/Princev/Princen/Princus/Heir Other gender neutral terms for Prince/Princess/Royalty incorporating the letter x; a common indicator of gender neutral language.

- Pilot. Standard gender neutral term for aviator or aviatrix.

- Police officer or cop. Standard gender neutral terms for policeman or policewoman.

- Priestx. Other gender neutral term to substitute for Priest or Priestess, mainly used in Pagan community.

- Quing. Neologistic gender-neutral term for a monarch.

- Royalty. Standard. Usually refers to a family but can be used as a Gender Neutral term for a prince/princess or a king/queen.

- Server. Standard gender neutral term for a person who provides items to customers, such as a «waiter/waitress» or «steward/stewardess».

- Wix. Neologistic gender neutral term for a magic user (akin to «witch»/»wizard»). Originated in Harry Potter fandom[26], created by tumblr blog magicqueers.[27] However, many people view «witch» as gender neutral instead of specific to women.[28][29][30]

Descriptions[edit | edit source]

- Attractive. Gender neutral term equally applicable to «handsome» or «beautiful» individuals. Implies the speaker experiences some form of attraction, so might not be suitable for people who are aromantic or asexual.

- Good-looking. Standard gender neutral term.

- Gorgeous. Gender neutral alternative to «handsome» or «beautiful,» but tends to be feminine.

- Youthful. Gender neutral alternative to «boyish» or perhaps «girlish,» but tends to be masculine.

- Dapper. Gender neutral alternative to «handsome» or «beautiful,» but tends to be masculine.

- Charming. Gender neutral alternative to «handsome» or «beautiful,» but tends to be masculine.

- Snazzy. Gender neutral alternative to «handsome» or «beautiful,» tends to be a more playful term.

Deity titles[edit | edit source]

- Absolute Being. Standard term for a monotheistic deity, without implied gender.

- Almighty. Standard term for a monotheistic deity, without implied gender.

- Creator. Standard term for a deity who created the world and/or humankind.

- Deity. Standard gender neutral term for a god or goddess.

- Divine, the. Common gender neutral term for a deity or supernatural forces.

- Divine being. Common gender neutral term for a deity or supernatural entity.

- God. Standard gender neutral term for a god or goddess, but tends to be presumed male.

- Goddex. «Queer, based on the God/dess ending.»[7]

- Goddette. «Queer, based on the God/ess ending.»[7]

- Goddeq. «Queer, based on the God/ess ending.»[7]

- Heavens, the. Common gender neutral term for a deity, deities, or supernatural forces.

- Higher Power. Standard gender neutral term for a deity, deities, or supernatural forces.

- Liege. Neutral equivalent of lord or lady.

- Powers that be. Common gender neutral term for a god, goddess, or similar supernatural beings or forces.

- Ruler. Neutral equivalent of lord or lady.

- Sovereign. Neutral equivalent of lord or lady.

- Wild Divine, the. New Age name for God, Goddess, or primal supernatural forces.

Other terms[edit | edit source]

- Bachelorx. Neutral, alternative to bachelor and bachelorette.[31]

- Fanenby. Queer, using enby after fanboy or fangirl.[7]

- Fanby. Queer. Similar to Fanenby

- Fankid. Neutral, after fanboy or fangirl.

- Fanchild. Neutral. Similar to fankid.

- Fellowship of the Rings. Neutral alternative to a party of nonbinary Wedding Ushers.

- Wedding usher. Neutral, alternative to bridesmaid or groomsman.

See also[edit | edit source]

- Gender neutral language

- Glossary of English gender and sex terminology

External links[edit | edit source]

- «Gender neutral/queer titles.» Gender Queeries. http://genderqueeries.tumblr.com/titles

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Dictionary.com. «English used to have gendered nouns?! Yes!» May 16, 2012. Dictionary.com (blog). http://blog.dictionary.com/oldenglishgender/

- ↑ Elizabeth Isele, «Casey Miller and Kate Swift: Women who dared to disturb the lexicon.» http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/old-WILLA/fall94/h2-isele.html

- ↑ Moser, Charles; Devereux, Maura (2016). «Gender neutral pronouns: A modest proposal». International Journal of Transgenderism. 20 (2–3): 331–332. doi:10.1080/15532739.2016.1217446. ISSN 1553-2739.

- ↑ «Facebook Groups». www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- ↑ «Facebook Groups». www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- ↑ https://nonbinarywiki.tumblr.com/post/621003149724041217/on-enby-and-age

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 7.25 7.26 7.27 7.28 7.29 7.30 7.31 7.32 7.33 7.34 7.35 7.36 7.37 7.38 7.39 7.40 7.41 7.42 7.43 7.44 7.45 7.46 7.47 7.48 7.49 7.50 7.51 7.52 7.53 7.54 7.55 7.56 7.57 7.58 7.59 7.60 7.61 7.62 7.63 7.64 7.65 7.66 7.67 7.68 7.69 7.70 7.71 7.72 7.73 7.74 7.75 7.76 7.77 7.78 7.79 7.80 7.81 7.82 7.83 7.84 «Gender neutral/queer titles.» Gender Queeries. http://genderqueeries.tumblr.com/titles

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Lane, S. Nicole (26 June 2019). «LGBTQ Glossary». Chicago Reader. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ Parents, Same Sex (2019-03-22). «Gender Neutral/Non-Binary Parent Titles». Same Sex Parents. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- ↑ Katie Hall. June 11, 2017.

https://ithelpstodream.tumblr.com/post/161695436793 - ↑ «Definition of CHITLINS». www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- ↑ On “enby” and age, 15 June 2020, Gender Census

- ↑ Poll on Twitter.

- ↑ Gender neutral variant of aunt/uncle by Over Explaining Autistic

- ↑ Coined by linguist Samuel E. Martin in 1951 from nephew/niece by analogy with sibling.

- ↑ Jed Hartman. «nibling, niephling, niefling, etc» Oct. 27, 2008. Neology (blog) https://www.kith.org/journals/neology/2008/10/nibling_niephling_niefling_etc.html

- ↑ Lang, Nico (21 August 2019). «Cory Booker: Nonbinary ‘Niephew’ Taught Me How to Be Trans Ally». out.com. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ↑ https://realtransfacts.tumblr.com/post/187145281108/enbyfriend-theyfriend-joyfriend

- ↑ @ThatBoyYouLike (15 August 2019). «If your partner is non-binary you got a joyfriend» – via Twitter.

- ↑ Elijah (26 January 2016). «today my professor shortened the term «significant others» to «signifs» reblog to make signif the new gender neutral term for the person you’re dating». Archived from the original on 29 November 2020.

- ↑ «fiancé». Wiktionary, The Free Dictionary. 26 May 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ↑ «Fiancé vs. Fiancée: Which One Is Which?». Dictionary.com. 6 May 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

there appears to be a growing trend toward using fiancé as the gender-neutral form for both a man and a woman.

- ↑ https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/52135/3-facts-about-english%E2%80%99s-most-adorable-suffix-ling

- ↑ Hartzer, Paul (2 January 2020). «Gender Neutral: Actor». Medium. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ↑ Dillon, Asia Kate (10 June 2020). «‘Billions’ Star Asia Kate Dillon Calls for SAG Awards to Abolish Gender-Specific Categories (EXCLUSIVE)». Variety. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ↑ https://wixenzine.tumblr.com/about

- ↑ https://fanlore.org/wiki/Wix

- ↑ Are you still a witch if:

- ↑ The term “witch” is gender neutral, pass it on

- ↑ A witch is a witch regardless of gender

- ↑ «bachelorx». Wiktionary, The Free Dictionary. 19 October 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

Gender-neutral language is language that avoids assumptions about the social gender or biological sex of people referred to in speech or writing. In contrast to most other Indo-European languages, English does not retain grammatical gender and most of its nouns, adjectives and pronouns are therefore not gender-specific. In most other Indo-European languages, nouns are grammatically masculine (as in Spanish el humano) or grammatically feminine (as in French la personne), or sometimes grammatically neuter (as in German das Mädchen), regardless of the actual gender of the referent.

In addressing natural gender, English speakers use linguistic strategies that may reflect the speaker’s attitude to the issue or the perceived social acceptability of such strategies.

DebateEdit

Supporters of gender-neutral language argue that making language less biased is not only laudable but also achievable. Some people find the use of non-neutral language to be offensive.[1]

[There is] a growing awareness that language does not merely reflect the way we think: it also shapes our thinking. If words and expressions that imply that women are inferior to men are constantly used, that assumption of inferiority tends to become part of our mindset… Language is a powerful tool: poets and propagandists know this – as, indeed, do victims of discrimination.[2]

The standards advocated by supporters of the gender-neutral modification in English have been applied differently and to differing degrees among English speakers worldwide. This reflects differences in culture and language structure, for example American English in contrast to British English.

Support forEdit

Supporters of gender-neutral language argue that the use of gender-specific language often implies male superiority or reflects an unequal state of society.[3][4] According to The Handbook of English Linguistics, generic masculine pronouns and gender-specific job titles are instances «where English linguistic convention has historically treated men as prototypical of the human species.»[5] That masculine forms are used to represent all human beings is in accord with the traditional gender hierarchy, which grants men more power and higher social status than women.[6]

Supporters also argue that words that refer to women often devolve in meaning, frequently developing sexual overtones.[7]

The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing says that the words children hear affect their perceptions of the gender-appropriateness of certain careers (e.g. firemen vs firefighters).[8] Men and women apply for jobs in more equal proportions when gender-neutral language is used in the advertisement, as opposed to the generic he or man.[9] Some critics claim that these differences in usage are not accidental, but have been deliberately created for the purpose of upholding a patriarchal society.[10]

OppositionEdit

Various criticisms have been leveled against the use of gender-neutral language, most focusing on specific usages, such as the use of «human» instead of «man» and «they» instead of «he». Opponents argue that the use of any other forms of language other than gender-specific language could «lead one into using awkward or grating constructions» or neologisms that are so ugly as to be «abominations».[11]

Opponents of gender-neutral language often argue that its proponents are impinging on the right of free expression and promoting censorship, as well as being overly accommodating to the sensitivities of a minority.[12] A few commentators do not disagree with the usage of gender-neutral language, but they do question the effectiveness of gender-neutral language in overcoming sexism.[9][13]

In religionEdit

Much debate over the use of gender-neutral language surrounds questions of liturgy and Bible translation. Some translations of the Bible in recent years have used gender-inclusive pronouns, but these translations have not been universally accepted.[14]

Naming practicesEdit

Some critics oppose the practice of women changing their names upon marriage, on the grounds that it makes women historically invisible: «In our society ‘only men have real names’ in that their names are permanent and they have ‘accepted the permanency of their names as one of the rights of being male.’… Essentially this practice means that women’s family names do not count and that there is one more device for making women invisible.»[15] Up until the 1970s, as women were granted greater access to professions, they would be less likely to change their names, either professionally or legally; names were seen as tied to reputations and women were less likely to change their names when they had higher reputations.[16] However, that trend was reversed starting in the 1970s; since that time, increasingly more women have been taking their husband’s surname upon marriage, especially among well-educated women in high-earning occupations.[17] Increasingly, studies have shown women’s decisions on the issue are guided by factors other than political or religious ideas about women’s rights or marital roles, as often believed.

The practice of referring to married women by their husband’s first and last names, which only died out in the late 20th century, has been criticized since the 19th century. When the Reverend Samuel May «moved that Mrs Stephen Smith be placed on a Committee» of the National Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, Lucretia Mott quickly replied: «Woman’s Rights’ women do not like to be called by their husbands’ names, but by their own».[18] Elizabeth Cady Stanton refused to be addressed as «Mrs Henry B. Stanton».[19] The practice was developed in the mid-18th century and was tied to the idea of coverture, the idea that «By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law; that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage.»[20]

There is a tendency among scientists to refer to women by their first and last name and to men by their last name only. This may result in female scientists being perceived as less eminent than their male colleagues.[21]

Examples of gender neutral languageEdit

Job titlesEdit

Gender-neutral job titles do not specify the gender of the person referred to, particularly when the gender is not in fact known, or is not yet specified (as in job advertisements). Examples include firefighter instead of fireman; flight attendant instead of steward or stewardess; bartender instead of barman or barmaid; and chairperson or chair instead of chairman or chairwoman.

There are also cases where a distinct female form exists, but the basic (or «male») form does not intrinsically indicate a male (such as by including man), and can equally well be applied to any member of the profession, whether male or female or of unspecified sex. Examples include actor and actress; usher and usherette; comedian and comedienne. In such cases, proponents of gender-neutral language generally advocate the non-use of the distinct female form (always using comedian rather than comedienne, for example, even if the referent is known to be a woman).

Terms such as male nurse, male model or female judge are sometimes used in cases where the gender is irrelevant or already understood (as in «my brother is a male nurse»). Many advisors on non-sexist usage discourage such phrasing, as it implies that someone of that gender is an inferior or atypical member of the profession. Another discouraged form is the prefixing of an ordinary job title with lady, as in lady doctor: here woman or female is preferred if it is necessary to specify the gender. Some jobs are known colloquially with a gender marker: washerwoman or laundress (now usually referred to as a laundry worker), tea lady (formerly in offices, still in hospitals), lunch lady (American English) or dinner lady (British English), cleaning lady for cleaner (formerly known as a charwoman or charlady), and so on.

Generic words for humansEdit

Another issue for gender-neutral language concerns the use of the words man, men and mankind to refer to a person or people of unspecified sex or to persons of both sexes.

Although the word man originally referred to both males and females, some feel that it no longer does so unambiguously.[22] In Old English, the word wer referred to males only and wif to females only, while man referred to both,[23] although in practice man was sometimes also used in Old English to refer only to males.[24] In time, wer fell out of use, and man came to refer sometimes to both sexes and sometimes to males only; «[a]s long as most generalizations about men were made by men about men, the ambiguity nestling in this dual usage was either not noticed or thought not to matter.»[25] By the 18th century, man had come to refer primarily to males; some writers who wished to use the term in the older sense deemed it necessary to spell out their meaning. Anthony Trollope, for example, writes of «the infinite simplicity and silliness of mankind and womankind»,[26] and when «Edmund Burke, writing of the French Revolution, used men in the old, inclusive way, he took pains to spell out his meaning: ‘Such a deplorable havoc is made in the minds of men (both sexes) in France….'»[27]

Proponents of gender-neutral language argue that seemingly generic uses of the word «man» are often not in fact generic. Miller and Swift illustrate with the following quotation:

As for man, he is no different from the rest. His back aches, he ruptures easily, his women have difficulties in childbirth….

«If man and he were truly generic, the parallel phrase would have been he has difficulties in childbirth«, Miller and Swift comment.[28] Writing for the American Philosophical Association, Virginia L. Warren follows Janice Moulton and suggests truly generic uses of the word man would be perceived as «false, funny, or insulting», offering as an example the sentence «Some men are female.»[29]

Further, some commentators point out that the ostensibly gender-neutral use of man has in fact sometimes been used to exclude women:[30]

Thomas Jefferson did not make the same distinction in declaring that «all men are created equal» and «governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.» In a time when women, having no vote, could neither give nor withhold consent, Jefferson had to be using the word men in its principal sense of males, and it probably never occurred to him that anyone would think otherwise.[27]

For reasons like those above, supporters of gender-neutral language argue that linguistic clarity as well as equality would be better served by having man and men refer unambiguously to males, and human(s) or people to all persons;[31] similarly, the word mankind replaced by humankind or humanity.[32]

The use of the word man as a generic word referring to all humans has been declining, particularly among female speakers and writers.[8]

PronounsEdit

Another target of frequent criticism by proponents of gender-neutral language is the use of the masculine pronoun he (and its derived forms him, his and himself) to refer to antecedents of indeterminate gender. Although this usage is traditional, some critics argue that it was invented and propagated by males, whose explicit goal was the linguistic representation of male superiority.[33] The use of the generic he was approved in an Act of Parliament, the Interpretation Act 1850 (the provision continues in the Interpretation Act 1978, although this states equally that the feminine includes the masculine). On the other hand, in 1879 the word «he» in by-laws was used to block admission of women to the Massachusetts Medical Society.[34]

Proposed alternatives to the generic he include he or she (or she or he), s/he, or the use of singular they. Each of these alternatives has met with objections. The use of he or she has been criticized for reinforcing the gender binary.[35] Some[36] see the use of singular they to be a grammatical error, but according to most references, they, their and them have long been grammatically acceptable as gender-neutral singular pronouns in English, having been used in the singular continuously since the Middle Ages, including by a number of prominent authors, such as Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare, and Jane Austen.[37] Linguist Steven Pinker goes further and argues that traditional grammar proscriptions regarding the use of singular «they» are themselves incorrect:

The logical point that you, Holden Caulfield, and everyone but the language mavens intuitively grasp is that everyone and they are not an «antecedent» and a «pronoun» referring to the same person in the world, which would force them to agree in number. They are a «quantifier» and a «bound variable», a different logical relationship. Everyone returned to their seats means «For all X, X returned to X’s seat.» The «X» does not refer to any particular person or group of people; it is simply a placeholder that keeps track of the roles that players play across different relationships. In this case, the X that comes back to a seat is the same X that owns the seat that X comes back to. The their there does not, in fact, have plural number, because it refers neither to one thing nor to many things; it does not refer at all.[38]

Some style guides (e.g. APA[39]) accept singular they as grammatically correct,[40] while others[which?] reject it. Some, such as The Chicago Manual of Style, hold a neutral position on the issue, and contend that any approach used is likely to displease some readers.[41]

Research has found that the use of masculine pronouns in a generic sense creates «male bias» by evoking a disproportionate number of male images and excluding thoughts of women in non-sex specific instances.[42][43] Moreover, a study by John Gastil found that while they functions as a generic pronoun for both males and females, males may comprehend he/she in a manner similar to he.[44]

HonorificsEdit

Proponents of gender-neutral language point out that while Mr is used for men regardless of marital status, the titles Miss and Mrs indicate a woman’s marital status, and thus signal her sexual availability in a way that men’s titles do not.[45] The honorific «Ms» can be used for women regardless of marital status.

The gender-neutral honorific Mx (usually «mix», MUKS) can be used in place of gendered honorifics to provide gender neutrality.[46][47][48] Adoption of the honorific has been relatively rapid and thorough in the UK. In 2013, Brighton and Hove City Council in Sussex, England, voted to allow its use on council forms,[49] and in 2014, The Royal Bank of Scotland included the title as an option.[50] In 2015, recognition spread more broadly across UK institutions, including the Royal Mail, government agencies responsible for documents such as drivers’ licenses, and several other major banks.[51] In 2015, it was included in the Oxford English Dictionary.[52]

Style guidance by publishers and othersEdit

Many editing houses, corporations, and government bodies have official policies in favor of in-house use of gender-neutral language. One of the first was The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing: For writers, editors, and speakers, published in 1980; linguist Deborah Cameron argues that the work by Casey Miller and Kate Swift brought «the issue of sexist language into the mainstream».[53]

In some cases, laws exist regarding the use of gender-neutral language in certain situations, such as job advertisements. Different authorities have presented guidelines on whether and how to use gender-neutral, or «non-sexist» language. Several are listed below:

- The «Publication Manual» of the American Psychological Association has an oft-cited section on «Guidelines to Reduce Bias in Language». ISBN 1-55798-791-2

- American Philosophical Association Archived 2003-04-13 at the Wayback Machine—published 1986

- The Guardian—see section «gender issues»

- Avoiding Heterosexual Bias in Language, published by the Committee on Lesbian and Gay Concerns, American Psychological Association.

In addition, gender-neutral language has gained support from some major textbook publishers, and from professional and academic groups such as the American Psychological Association and the Associated Press. Newspapers such as the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal use gender-neutral language. Many law journals, psychology journals, and literature journals will only print articles or papers that use gender-inclusive language.[34]

Employee policy manuals sometimes include strongly worded statements prescribing avoidance of language that potentially could be considered discriminatory. One such example is from the University of Saskatchewan: «All documents, publications or presentations developed by all constituencies…shall be written in gender neutral and/or gender inclusive language.»[54]

In 1989 the American Bar Association’s House of Delegates adopted a resolution stating that «the American Bar Association and each of its entities should use gender-neutral language in all documents establishing policy and procedure.»[55]

In 2015 the Union for Reform Judaism in North America passed a «Resolution on the Rights of Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People» stating in part: «THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED THAT the Union for Reform Judaism…[u]rges Reform Movement institutions to review their use of language in prayers, forms and policies in an effort to ensure people of all gender identities and gender expressions are welcomed, included, accepted and respected. This includes developing statements of inclusion and/or non-discrimination policies pertaining to gender identity and gender expression, the use when feasible of gender-neutral language, and offering more than two gender options or eliminating the need to select a gender on forms».[56][57]

See alsoEdit

- Epicene

- Gender in English

- Gender role

- Gender neutrality in languages with grammatical gender

- Gender neutrality in genderless languages

- Gender marking in job titles

- Generic antecedent

- Markedness

- Unisex name

- «You guys»

CitationsEdit

- ^ Chappell, Virginia (2007). «Tips for Using Inclusive, Gender Neutral Language». Marquette.edu. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ «Guidelines on Gender-Neutral Language», page 4. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 1999. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0011/001149/114950mo.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2007.

- ^ Spender (1980), p. x

- ^ Miller & Swift (1988), pp. 45, 64, 66

- ^ Aarts, Bas and April M. S. McMahon. The Handbook of English Linguistics. Malden, MA; Oxford: Blackwell Pub., 2006, ISBN 978-1-4051-1382-3.

- ^ Prewitt-Freilino, J.L.; Caswell, T.A.; Laakso, E.K. (2012). «The Gendering of Language: A Comparison of Gender Equality in Countries with Gendered, Natural Gender, and Genderless Languages». Sex Roles. SpringerLink. 66 (3–4): 268–281. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-0083-5. S2CID 145066913. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Spender (1980), p. 18

- ^ a b Miller & Swift (1988)

- ^ a b Mills (1995)

- ^ Spender (1980), pp. 1–6

- ^ Lynch, Jack. «Guide to Grammar and Style». rutgers.edu. Archived from the original on July 7, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ Louis Markos (August 4, 2009). «One Eternal Day: A world safe from male pronouns». One-eternal-day.com. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ Pauwels, Anne (2003). «Linguistic Sexism and Feminist Linguistic Activism». The Handbook and Language of Gender: 550–570. doi:10.1002/9780470756942.ch24. ISBN 9780470756942.

- ^ «The Gender-Neutral Language Controversy». Bible Research. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Spender (1980), p. 24

- ^ Stannard (1977), pp. 164–166

- ^ Sue Shelenbarger (May 8, 2011). «The Name Change Dilemma — The Juggle». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ Quoted in Stannard (1977), p. 3

- ^ Stannard (1977), p. 4

- ^ Henry Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, quoted in Stannard (1977), p. 9

- ^ «Calling men by their surname gives them an unfair career boost». Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ Miller & Swift (1988), pp. 11–17

- ^ Curzan (2003), p. 134

- ^ Curzan (2003), p. 163

- ^ Miller & Swift (1988), p. 12

- ^ Quoted in Miller & Swift (1988), p. 26

- ^ a b Miller & Swift (1988), p. 12

- ^ Miller & Swift (1988), p. 15

- ^ Warren, Virginia L. «Guidelines for Non-Sexist Use of Language». American Philosophical Association. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Freeman (1979), p. 492

- ^ Freeman (1979), p. 493

- ^ Miller & Swift (1988), pp. 27

- ^ Spender (1980), pp. 147. Among writers defending the usage of generic he, the author cites a Thomas Wilson, writing in 1553, and grammarian Joshua Poole (1646).

- ^ a b Carolyn Jacobsen. «Some Notes on Gender-Neutral Language». english.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ Chak, Avinash (7 December 2015). «Beyond ‘he’ and ‘she’: The rise of non-binary pronouns». BBC News. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ «Pronouns | Pronoun Examples and Rules».

- ^ Churchyard, Henry. «Jane Austen and other famous authors violate what everyone learned in their English class». Archived from the original on 2009-04-30. Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- ^ Pinker (2000)

- ^ «APA Styleguide».

- ^ Peters, Pam (2004). The Cambridge Guide to English Usage. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62181-6.

- ^ University of Chicago. Press (2003). The Chicago Manual of Style. University of Chicago Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-226-10403-4.

- ^ Miller, Megan M.; James, Lorie E. (2009). «Is the generic pronoun he still comprehended as excluding women?». The American Journal of Psychology. 122 (4): 483–96. doi:10.2307/27784423. JSTOR 27784423. PMID 20066927. S2CID 44644673.

- ^ Hamilton, Mykol C. (1988). «Using masculine generics: Does generic he increase male bias in the user’s imagery?». Sex Roles. 19 (11–12): 785–99. doi:10.1007/BF00288993. S2CID 144493073.

- ^ Gastil, John (1990). «Generic pronouns and sexist language: The oxymoronic character of masculine generics». Sex Roles. 23 (11–12): 629–43. doi:10.1007/BF00289252. S2CID 33772213.

- ^ Freeman (1979), p. 491

- ^ Jane Fae (18 January 2013). «It’s going to be Mr, Mrs or ‘Mx’ in Brighton as city goes trans friendly». Gay Star News. Archived from the original on 2021-01-22. Retrieved 2013-09-10.

- ^ «Honorifics could be dropped from official letters by council». The Telegraph. October 25, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ «Trans Equality Scrutiny Panel» (PDF). Brighton & Hove City Council. January 2013. Retrieved 2013-09-10.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «Mx (Mixter) title adopted in Brighton for transgender people». BBC News. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Saner, Emine (17 November 2014). «RBS: the bank that likes to say Mx». The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ «Now pick Mr, Mrs, Miss, Ms . . . or Mx for no specific gender». The Times. Archived from the original on 2017-07-08.

- ^ «Mx». Oxford dictionaries. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ «Sexism in language: A problem that hasn’t gone away». Discover Society. 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ^ «Gender Neutral Language». University of Saskatchewan Policies. 2001. Archived from the original on 2006-10-28. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ^ «American Bar Association section of tort and insurance practice and the commission on women in the profession» (PDF). americanbar.org. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ Barbara Liston (November 5, 2015). «U.S. Reform Jews adopt sweeping transgender rights policy». Yahoo News. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ «Resolution on the Rights of Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People». Urj.org. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

ReferencesEdit

- Curzan, Anne (2003). Gender shifts in the history of English. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82007-3.

- Freeman, Jo (1979). Women, a feminist perspective. Mayfield Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87484-422-1.

- Miller, Casey; Swift, Kate (1988). The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-273173-9.

- Mills, Sara (1995). Feminist Stylistics. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05027-2.

- Pinker, Steven (2000). The Language Instinct: How the mind creates language. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-095833-6.

- Spender, Dale (1980). Man Made Language. Pandora. ISBN 978-0-04-440766-9.

- Stannard, Una (1977). Mrs Man. GermainBooks. ISBN 978-0-914142-02-7.

Further readingEdit

- Ansary, H.; Babaii, E. (March 2003). «Subliminal sexism in current ESL EFL textbooks». The Asian EFL Journal. Archived from the original on February 10, 2006. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- Beisner, E. Calvin (2003). «Does the Bible really support gender-inclusive language?». Christiananswers.net. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- Guyatt, Gordon H.; Cook, Deborah J.; Griffith, Deborah J.; Walter, Stephen D.; Risdon, Catherine; Liutkus, Joanne (1997). «Attitudes toward the use of gender-inclusive language among residency trainees». Can Med Assoc (CMAJ). 156 (9): 1289–93. PMC 1227330. PMID 9145055.

- The American Heritage Book of English Usage: A Practical and Authoritative Guide to Contemporary English. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1996. ISBN 978-0-547-56321-3.

- Hyde, Martin (2001). «Appendix 1 – Use of gender-neutral pronouns». Democracy Education and the Canadian Voting Age (Thesis). pp. 144–146. doi:10.14288/1.0055498.

- Shetter, William Z. (2000). «Female Grammar: Men’s speech and women’s speech». bluemarble.net. Archived from the original on May 31, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- Zijlstra, Maria (August 26, 2006). «Anyone who had a heart would know their own language». Lingua Franca. ABC Radio National. Retrieved July 16, 2016. Transcript of ABC Radio program on the singular they.

External linksEdit

- Regender can translate English web pages so as to swap genders. Reading such gender-swapped pages can be an interesting exercise in detecting «gender-biased language».

- «CBT Policy on Gender-Inclusive Language». Bible-researcher.com. 1992. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- «Guidelines for Gender-Fair Use of Language». Ncte.org. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

Gender neutral is a term used when referring to a person of neutral gender, someone who is neither male nor female, but genderless.[1] It is also another term for agender, with the words often being used in conjunction with one another as both an identity and a describing characteristic.[2][3] It is also a term used to signal a safe and inclusive space for LGBTQIA+ individual, and a term used to describe pronouns or language that defies the binary.[4]

Etymology

As an adjective, gender neutral describes the use of words wherever appropriate that are free of reference to gender: firefighter, police officer, and flight attendant are gender neutral terms.[1]

Pronouns

Gender-neutral pronouns are similar to binary pronouns (she/her and he/him) but are altered to individual preference. One might prefer the commonly used gender neutral pronouns they/them. In place of Mr. or Mrs./Ms., a gender-neutral title would be Mx.[5] Mx was first recorded in April 1977 in an edition of The Single Parent.[6]

History

Gender-neutral language has existed for hundreds of years. One of the first usages of gender neutral language in literature is in the 1386 novel of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and also in famous literary works such as Shakespeare’s Hamlet in 1599. Jane Austen used they/them pronouns in her infamous novel, Pride and Prejudice.[7] By 1841, there were several pronouns that were used, many of which were gender neutral.[8] The first notable use of gender neutral pronouns came in 1911 by Fred S. Pond, an insurance broker. They grew in popularity in January 1912, when Ella Fagg Young — the first female superintendent of Chicago schools, proposed a new term that would end the awkwardness of speech. Her idea was «he’er, his’er, and ‘him’er«.[9]

In recent years, gender neutral has expanded beyond pronouns and language to include fashion. The uptick in demand for gender neutral fashion increased in 2019, which inspired many companies to create new fashion lines. This allowed people to wear clothing that were not inherently made for a masculine or feminine individual.[10]

Distinction

Controversy

One of the largest arguments around gender neutral language is the role it plays in «proper grammar». The traditional gender agreement rule states that pronouns must agree with the nouns they stand for both in gender and in number. While everyone loves their mother is grammatically correct, using they/them in a singular context is considered grammatically incorrect.[11]

In 2015, when the University of Tennessee updated their website to include a guide to gender-neutral pronouns, many conservative politicians were angered. Hundreds of calls were placed to the university’s president to protest the addition. Because of the backlash and intense scrutiny given by the lawmakers in the state, including two special meetings to review the governance, the president of the university chose to remove the guide. Other colleges across the United States had begun to implement a similar guide. Vanderbilt University, Harvard University, and the University of California each include gender neutral pronouns and language in their handbooks. The latter universities even allowed students to specify their gender identities on documents.[12]

Restrooms

The use of gendered restrooms makes many LGBTQIA+ individuals feel uncomfortable or as if they aren’t being seen, especially in the workplace. By offering a third or additional option of a gender neutral bathroom, a workplace is seen as taking action toward diversity and inclusion.[13] In 2009, 67% of transgender and non-binary people felt unsafe in a public gendered bathroom.[14] Gender neutral restrooms have been called an important alternative for non-binary, gender non-conforming, agender, transgender, and others on the gender spectrum.[15]

In April 2014, Vancouver Park board installed gender neutral restrooms in their public buildings. They were not the first to do this, as gender neutral facilities had existed in many regions. However, Vancouver was the first municipality to require buildings have gender neutral restrooms.[16] Trevor Loke, the commissioner, stated that their goal was use more inclusive language based on the BC Human Rights Code. They also used a pink triangle, a sign commonly used in the LGBTQIA+ community, to signal the gender neutral restrooms. They even called for public opinion on the signage.[17]

In 2014 and following years, China, India, Japan, and Nepal followed suit in implementing gender neutral restrooms.[18][19]

Media

- Gender neutral books on Goodreads

- Eth — Eth’s Skin

Public Figures

- Miley Cyrus[20]

Trivia

- In 2020, Trevor Project ran a survey that found one in four LGBTQ youths (ages 13–24) use gender neutral pronouns. 4% of those surveyed used neopronouns such as xe/xim and ze/zir.[21]

- In a study down by Outandequal.org, they found that 78% of respondents (all from Generation Z) defined gender as being fluid. Of those same respondents, 56% of them knew someone with gender neutral pronouns.[22]

- In a study conducted by researchers, using gender-neutral language and pronouns to describe individuals reduces biases in the workplace. It improved positive feelings between women and LGBTQIA+ people.[23]

- The word «they» was Merriam Webster’s online Dictionary word of the year, after adding the singular use of the word to their website.[24]

Resources

- Gender-neutral language on Wikipedia

References

|

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Gender-neutral language or gender-inclusive language is language that avoids bias towards a particular sex or gender. In English, this includes use of nouns that are not gender-specific to refer to roles or professions,[1] formation of phrases in a coequal manner, and discontinuing the blanket use of male or female terms.[2] For example, the words policeman[3][4] and stewardess[5][6] are gender-specific job titles; the corresponding gender-neutral terms are police officer[7][8] and flight attendant.[9][10] Other gender-specific terms, such as actor and actress, may be replaced by the originally male term; for example, actor used regardless of gender.[11][12][13] Some terms, such as chairman,[14][15] that contain the component -man but have traditionally been used to refer to persons regardless of sex are now seen by some as gender-specific.[16] An example of forming phrases in a coequal manner would be using husband and wife instead of man and wife.[17] Examples of discontinuing the blanket use of male terms in English are referring to those with unknown or indeterminate gender as singular they, and using humans, people, or humankind, instead of man or mankind.[18]

History[edit]

The notion that parts of the English language were sexist was brought to mainstream attention in Western English cultures by feminists in the 1970s.[19] Simultaneously, the link between language and ideologies (including traditional gender ideologies) was becoming apparent in the academic field of linguistics.[20] In 1975, the National Council of Teachers of English published a set of guidelines on the use of «non-sexist» language.[21][22] Backlash ensued, as did the debate on whether gender-neutral language ought to be enforced.[22][19] In Britain, feminist Maija Blaubergs’ countered eight commonly used oppositional arguments in 1980.[23] In 1983, New South Wales, Australia required the use of they in place of he and she in subsequent laws.[24] In 1985, the Canadian Corporation for Studies in Religion passed a motion for all its ensuing publications to include «non-sexist» language.[25] By 1995, academic institutions in Canada and Britain had implemented «non-sexist» language policies.[26][27] More recently, revisions to the Women’s Press publications of The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing and The A–Z of Non-Sexist Language were made to de-radicalize the original works.[27] In 2006, «non-sexist» was challenged: the term refers solely to the absence of sexism.[27] In 2018, the State of New York enacted policy to formally use the gender-neutral terms police officer and firefighter.[24]

Terminology and views[edit]

General[edit]

Historically, the use of masculine pronouns in place of generic was regarded as non-sexist, but various forms of gender-neutral language have become a common feature in written and spoken versions of many languages in the late twentieth century. Feminists argue that previously the practice of assigning masculine gender to generic antecedents stemmed from language reflecting «the prejudices of the society in which it evolved, and English evolved through most of its history in a male-centered, patriarchal society.»[28] During the 1970s, feminists Casey Miller and Kate Swift created a manual, The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing, on gender neutral language that was set to reform the existing sexist language that was said to exclude and dehumanize women.[29] In 1995, the Women’s Press published The A–Z of Non-Sexist Language, by Margaret Doyle.[30] Both publications were written by American authors, originally without the consideration of the British-English dialect.[30] Many feminist efforts were made to reform the androcentric language.[31] It has become common in some academic and governmental settings to rely on gender-neutral language to convey inclusion of all sexes or genders (gender-inclusive language).[32][33]

Various languages employ different means to achieve gender neutrality:

- Gender neutrality in languages with grammatical gender

- Gender neutrality in genderless languages

- Gender neutrality in English

Other particular issues are also discussed:

- Gender marking in job titles

- Gender-specific and gender-neutral pronouns

Gender indication[edit]

There are different approaches in forming a «gender-neutral language»:

- Neutralising any reference to gender or sex, like using «they» as a third-person singular pronoun instead of «he» or «she», and proscribing words like actress (female actor) and prescribing the use of words like actor for persons of any gender. Although it has generally been accepted in the English language, some argue that using «they» as a singular pronoun is considered grammatically incorrect, but acceptable in informal writing.[34]

- Creating alternative gender-neutral pronouns, such as «hir» or «hen» in Swedish.[35]

- Indicating the gender by using wordings like «he or she» and «actors and actresses».

- Avoiding the use of «him/her» or the third-person singular pronoun «they» by using «the» or restructuring the sentence all together to avoid all three.[34]

- NASA now prefers the use of «crewed» and «uncrewed» instead of «manned» and «unmanned», including when discussing historical spaceflight (except proper nouns).[36]

| Gendered title | Gender-neutral title |

|---|---|

| businessman, businesswoman | business person/person in business, business people/people in business |

| chairman, chairwoman | chair, chairperson |

| mailman, mailwoman, postman, postwoman | mail carrier, letter carrier, postal worker |

| policeman, policewoman | police officer |

| salesman, saleswoman | salesperson, sales associate, salesclerk, sales executive |

| steward, stewardess | flight attendant |

| waiter, waitress | server, table attendant, waitron |

| fireman, firewoman | firefighter |

| barman, barwoman | bartender |

Controversy[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2021) |

Canada[edit]

University of Toronto psychology professor Jordan Peterson uploaded a video to YouTube expressing his opposition to Bill C-16 – An Act to amend the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code, a bill introduced by Justin Trudeau’s government, in October 2016.[38] The proposed piece of legislation was to add the terms «gender identity» and «gender expression» to the Canadian Human Rights Act and to the Criminal Code‘s hate crimes provisions.[38] In the video, Peterson argued that legal protection of gender pronouns results in «compelled speech», which would violate the right to freedom of expression outlined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[38] In the view of Peterson, legal pronoun protections would force an individual to say something that one opposes. The bill passed in the House of Commons and in the Senate, becoming law once it received Royal Assent on 19 June 2017.[39] In response to the passing of the bill, Peterson has stated he will not use gender-neutral pronouns if asked in the classroom by a student.[38]

France[edit]

In 2021, controversy spiked in France when the dictionary Petit Robert included the gender neutral term iel – composed of il (‘he’) and elle (‘she’). The dictionary’s director, Charles Bimbenet, stated it was added as researchers noted «an increasing usage» of the neutral pronoun in «a large body of texts drawn from various sources.»[40] However, a number of French politicians have opposed the new addition.

Jean-Michel Blanquer, the French Minister of Education, publicly tweeted: «inclusive writing is not the future of the French language.»[41] Similarly, François Jolivet, a French politician, accused the dictionary of pushing a «woke» ideology that «undermines [their] common language and its influence», in a letter addressed to the Académie Française.[42] The controversy weighs into the ongoing debate regarding masculine dominance in the French language.

United States[edit]

The American English language contains gendered connotations that make it challenging for gender-neutral language to achieve the desired linguistic equality. «Male default» is especially prominent in the United States and often when gender-neutral language is used around traditionally male institutions, the neutrality doesn’t prevent people from automatically translating «they» to the default «he.»[43] A study conducted in June 2021 at UCLA School of Law Williams Institute found that 1.2 Million LGBTQ adults identify as nonbinary.[44]

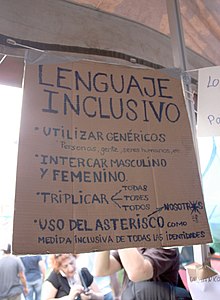

Argentina[edit]

Argentina’s capital, Buenos Aires, implemented a policy in June 2022 that forbade public educational institutions from using gender-neutral language on the basis gender-neutral language is grammatically incorrect and causes developmental learning issues for students.[45] In the Spanish language nouns are either feminine (usually ending in «a») or masculine (usually ending in «o»), but in recent years gender-neutral endings like «x» and «e» have gained popularity; For example, «Latinx» has become the gender-neutral option for the previously binary «Latino» or «Latina.»[46] Buenos Aires’ objection to gender-neutral language in the classroom stems from concerns about linguistic correctness and preservation of the Spanish language.[45] Those who support the development of gender-neutral language have expressed frustration with the male-dominance of the Spanish language: a group of students who are all female is «compañeras,» but if one male student enters the group, the grammatically correct term for the students becomes «compañeros» with the masculine «o» ending.[46]

Italy[edit]

The Italian language contains grammatical gender where nouns are either masculine or feminine with corresponding gendered pronouns, which differs from English in that nouns do not encode grammatical gender.[47] For example, «tavola» (in English table) in Italian is feminine. Developing a gender-neutral option in Italian is linguistically challenging because the Italian language marks only the masculine and feminine grammatical genders: «friends» in Italian is either «amici» or «amiche» where the masculine «-i» pluralized ending is used as an all-encompassing term, and «amiche» with the feminine «-e» pluralized ending refers specifically to a group of female friends.[47] Italian linguistically derived from Latin, which does contain a third «neuter» or neutral option.[47]

The use of a schwa <ə> has been suggested to create an Italian gender-neutral language option.[48] Some Italian linguists have signed a petition opposing the use of the schwa on the basis it’s not linguistically correct.[49] Other solutions proposed are the asterisk <*>, the <x>, the at sign <@>, the <u> and omitting gender-specific suffixes altogether.[50]

See also[edit]

In specific languages[edit]

- Gender neutrality in languages with grammatical gender

- Gender neutrality in English

- Gender neutrality in Spanish

- Gender neutrality in Portuguese

[edit]

- Epicenity

- Gender in Bible translation

- Gender binary

- Gender neutrality

- Gender role

- Genderless language

- Generic antecedent

- International Gender and Language Association, an interdisciplinary academic organization

- Markedness

- Non-binary gender

- Unisex name

- Gender-neutral pronoun

- Neopronoun

- Spivak pronoun

- Ri (pronoun), Esperanto

- Elle (Spanish pronoun)

- Hen (pronoun), Swedish

- Iel (pronoun), French

- Neopronoun

- Pronoun game

- Feminist language reform

- Lavender linguistics

- Gender marking in job titles

References[edit]

- ^ Fowler, H.W. (2015). Butterfield, Jeremy (ed.). Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966135-0.

- ^ Sarrasin, Oriane; Gabriel, Ute; Gygax, Pascal (2012-01-01). «Sexism and Attitudes Toward Gender-Neutral Language». Swiss Journal of Psychology. 71 (3): 113–4. doi:10.1024/1421-0185/a000078. ISSN 1421-0185.

- ^ «policeman — Definition and pronunciation — Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com». Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ «policeman definition, meaning — what is policeman in the British English Dictionary & Thesaurus — Cambridge Dictionaries Online». Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ «stewardess — Definition and pronunciation — Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com». Retrieved 10 October 2014.