This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

Morphology

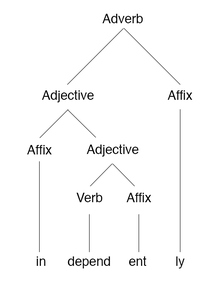

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Noun

How do you spell that word?

“Please” is a useful word.

Our teacher often used words I didn’t know.

What is the French word for car?

Describe the experience in your own words.

The lawyer used Joe’s words against him.

She gave the word to begin.

We will wait for your word before we serve dinner.

Verb

Could we word the headline differently?

tried to word the declaration exactly right

See More

Recent Examples on the Web

Despite the red flags, hundreds of investors were receiving their dividends on time and word was spreading.

—

For Lin, surviving sepsis left him determined to make sure that the word gets out about sepsis — and not just in English.

—

Hayes became the first woman to earn the honor in 1977, earning the title after her Grammy win for best spoken word recording for Great American Documents.

—

The Clue: This word starts with a consonant and ends with a vowel.

—

The word comes in the wake a ransomware attack that diverted attention from the company’s plans to address lagging profitability.

—

Because such people possessed no special skill or status, the word gradually fell into disrepute.

—

Detroit police on Monday called for help from the public – a week after Kemp on Jan. 23 reported Kelly missing and began spreading the word via social media and notifying news outlets.

—

The word Tuesday was that more than 12,000 tickets had been sold.

—

Tennessee passed a bill that is seen as possibly banning most drag performances in the state, although a federal judge temporarily blocked it last week on the basis that it was too vaguely worded to draw boundaries.

—

On Thursday, the meeting in New Delhi of the foreign ministers of the Group of 20, representing the world’s largest economies, failed to release a joint agreement due to opposition from China and Russia on wording about the Ukraine war.

—

Despite the changes, top Democrat in the Arkansas House said the bill was worded too vaguely.

—

What that percentage is will need to be calculated on a basis aligned with the nature of the product, the nature of the generative AI app, and the nature of how the product placement is worded.

—

Make sure to word your instructions carefully.

—

How is the city’s referendum worded?

—

In addition, how a query was worded influenced the accuracy of the model’s response.

—

The players all share a loose but focused way about them, words infielder David Fletcher used to describe the clubhouse.

—

See More

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word ‘word.’ Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Although

the borderline between various linguistic units is not always sharp

and clear, we shall try to define every new term on its first

appearance at once simply and unambiguously, if not always very

rigorously. The approximate definition of the term word

has already been given in the opening page of the book.

The

important point to remember about

definitions

is that they should indicate the most essential characteristic

features of the notion expressed by the term under discussion, the

features by which this notion is distinguished from other similar

notions. For instance, in defining the word one must distinguish it

from other linguistic units, such as the phoneme, the morpheme, or

the word-group. In contrast with a definition, a description

aims at enumerating all the essential features of a notion.

To

make things easier we shall begin by a preliminary description,

illustrating it with some examples.

The

word

may be described as the basic unit of language. Uniting meaning and

form, it is composed of one or more morphemes, each consisting of one

or more spoken sounds or their written representation. Morphemes as

we have already said are also meaningful units but they cannot be

used independently, they are always parts of words whereas words can

be used as a complete utterance (e. g. Listen!).

The

combinations of morphemes within words are subject to certain linking

conditions. When a derivational affix is added a new word is formed,

thus, listen

and

listener

are

different words. In fulfilling different grammatical functions words

may take functional affixes: listen

and

listened

are

different forms of the same word. Different forms of the same word

can be also built analytically with the help of auxiliaries. E.g.:

The

world should listen then as I am listening now (Shelley).

When

used in sentences together with other words they are syntactically

organised. Their freedom of entering into syntactic constructions is

limited by many factors, rules and constraints (e. g.: They

told me this story but

not *They

spoke me this story).

The

definition of every basic notion is a very hard task: the definition

of a word is one of the most difficult in linguistics because the

27

simplest

word has many different aspects. It has a sound form because it is a

certain arrangement of phonemes; it has its morphological structure,

being also a certain arrangement of morphemes; when used in actual

speech, it may occur in different word forms, different syntactic

functions and signal various meanings. Being the central element of

any language system, the word is a sort of focus for the problems of

phonology, lexicology, syntax, morphology and also for some other

sciences that have to deal with language and speech, such as

philosophy and psychology, and probably quite a few other branches of

knowledge. All attempts to characterise the word are necessarily

specific for each domain of science and are therefore considered

one-sided by the representatives of all the other domains and

criticised for incompleteness. The variants of definitions were so

numerous that some authors (A. Rossetti, D.N. Shmelev) collecting

them produced works of impressive scope and bulk.

A

few examples will suffice to show that any definition is conditioned

by the aims and interests of its author.

Thomas

Hobbes (1588-1679),

one

of the great English philosophers, revealed a materialistic approach

to the problem of nomination when he wrote that words are not mere

sounds but names of matter. Three centuries later the great Russian

physiologist I.P. Pavlov (1849-1936)

examined

the word in connection with his studies of the second signal system,

and defined it as a universal signal that can substitute any other

signal from the environment in evoking a response in a human

organism. One of the latest developments of science and engineering

is machine translation. It also deals with words and requires a

rigorous definition for them. It runs as follows: a word is a

sequence of graphemes which can occur between spaces, or the

representation of such a sequence on morphemic level.

Within

the scope of linguistics the word has been defined syntactically,

semantically, phonologically and by combining various approaches.

It

has been syntactically defined for instance as “the minimum

sentence” by H. Sweet and much later by L. Bloomfield as “a

minimum free form”. This last definition, although structural in

orientation, may be said to be, to a certain degree, equivalent to

Sweet’s, as practically it amounts to the same thing: free forms

are later defined as “forms which occur as sentences”.

E.

Sapir takes into consideration the syntactic and semantic aspects

when he calls the word “one of the smallest completely satisfying

bits of isolated ‘meaning’, into which the sentence resolves

itself”. Sapir also points out one more, very important

characteristic of the word, its indivisibility:

“It cannot be cut into without a disturbance of meaning, one or two

other or both of the several parts remaining as a helpless waif on

our hands”. The essence of indivisibility will be clear from a

comparison of the article a

and

the prefix a-

in

a

lion and

alive.

A lion is

a word-group because we can separate its elements and insert other

words between them: a

living lion, a dead lion. Alive is

a word: it is indivisible, i.e. structurally impermeable: nothing can

be inserted between its elements. The morpheme a-

is

not free, is not a word. The

28

situation

becomes more complicated if we cannot be guided by solid spelling.’

“The Oxford English Dictionary», for instance, does not

include the

reciprocal pronouns each

other and

one

another under

separate headings, although

they should certainly be analysed as word-units, not as word-groups

since they have become indivisible: we now say with

each other and

with

one another instead

of the older forms one

with another or

each

with the other.1

Altogether

is

one word according to its spelling, but how is one to treat all

right, which

is rather a similar combination?

When

discussing the internal cohesion of the word the English linguist

John Lyons points out that it should be discussed in terms of two

criteria “positional

mobility”

and

“uninterruptability”.

To illustrate the first he segments into morphemes the following

sentence:

the

—

boy

—

s

—

walk

—

ed

—

slow

—

ly

—

up

—

the

—

hill

The

sentence may be regarded as a sequence of ten morphemes, which occur

in a particular order relative to one another. There are several

possible changes in this order which yield an acceptable English

sentence:

slow

—

ly

—

the

—

boy

—

s

—

walk

—

ed

—

up

—

the

—

hill

up —

the

—

hill

—

slow

—

ly

—

walk

—

ed

—

the

—

boy

—

s

Yet

under all the permutations certain groups of morphemes behave as

‘blocks’ —

they

occur always together, and in the same order relative to one another.

There is no possibility of the sequence s

—

the

—

boy,

ly —

slow,

ed —

walk.

“One

of the characteristics of the word is that it tends to be internally

stable (in terms of the order of the component morphemes), but

positionally mobile (permutable with other words in the same

sentence)”.2

A

purely semantic treatment will be found in Stephen Ullmann’s

explanation: with him connected discourse, if analysed from the

semantic point of view, “will fall into a certain number of

meaningful segments which are ultimately composed of meaningful

units. These meaningful units are called words.»3

The

semantic-phonological approach may be illustrated by A.H.Gardiner’s

definition: “A word is an articulate sound-symbol in its aspect of

denoting something which is spoken about.»4

The

eminent French linguist A. Meillet (1866-1936)

combines

the semantic, phonological and grammatical criteria and advances a

formula which underlies many subsequent definitions, both abroad and

in our country, including the one given in the beginning of this

book: “A word is defined by the association of a particular meaning

with a

1

E. Language.

An Introduction to the Study of Speech. London, 1921,

P.

35.

2 Lyons,

John. Introduction

to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge: Univ. Press, 1969.

P. 203.

3 Ullmann

St. The

Principles of Semantics. Glasgow, 1957.

P.

30.

4 Gardiner

A.H. The

Definition of the Word and the Sentence //

The

British Journal of Psychology. 1922.

XII.

P. 355

(quoted

from: Ullmann

St.,

Op.

cit., P. 51).

29

particular

group of sounds capable of a particular grammatical employment.»1

This

definition does not permit us to distinguish words from phrases

because not only child,

but

a

pretty child as

well are combinations of a particular group of sounds with a

particular meaning capable of a particular grammatical employment.

We

can, nevertheless, accept this formula with some modifications,

adding that a word is the smallest significant unit of a given

language capable of functioning alone and characterised by positional

mobility

within

a sentence, morphological

uninterruptability

and semantic

integrity.2

All these criteria are necessary because they permit us to create a

basis for the oppositions between the word and the phrase, the word

and the phoneme, and the word and the morpheme: their common feature

is that they are all units of the language, their difference lies in

the fact that the phoneme is not significant, and a morpheme cannot

be used as a complete utterance.

Another

reason for this supplement is the widespread scepticism concerning

the subject. It has even become a debatable point whether a word is a

linguistic unit and not an arbitrary segment of speech. This opinion

is put forth by S. Potter, who writes that “unlike a phoneme or a

syllable, a word is not a linguistic unit at all.»3

He calls it a conventional and arbitrary segment of utterance, and

finally adopts the already mentioned

definition of L. Bloomfield. This position is, however, as

we have already mentioned, untenable, and in fact S. Potter himself

makes ample use of the word as a unit in his linguistic analysis.

The

weak point of all the above definitions is that they do not establish

the relationship between language and thought, which is formulated if

we treat the word as a dialectical unity of form and content, in

which the form is the spoken or written expression which calls up a

specific meaning, whereas the content is the meaning rendering the

emotion or the concept in the mind of the speaker which he intends to

convey to his listener.

Summing

up our review of different definitions, we come to the conclusion

that they are bound to be strongly dependent upon the line of

approach, the aim the scholar has in view. For a comprehensive word

theory, therefore, a description seems more appropriate than a

definition.

The

problem of creating a word theory based upon the materialistic

understanding of the relationship between word and thought on the one

hand, and language and society, on the other, has been one of the

most discussed for many years. The efforts of many eminent scholars

such as V.V. Vinogradov, A. I. Smirnitsky, O.S. Akhmanova, M.D.

Stepanova, A.A. Ufimtseva —

to

name but a few, resulted in throwing light

1

A. Linguistique

historique et linguistique generate. Paris,

1926.

Vol.

I. P. 30.

2 It

might be objected that such words as articles, conjunctions and a few

other words

never occur as sentences, but they are not numerous and could be

collected into a

list of exceptions.

3 See:

Potter

S. Modern

Linguistics. London, 1957.

P.

78.

30

on this problem and achieved a

clear presentation of the word as a basic unit of the language. The

main points may now be summarised.

The

word

is the

fundamental

unit

of language.

It is a dialectical

unity

of form

and

content.

Its content or meaning is not identical to notion, but it may reflect

human notions, and in this sense may be considered as the form of

their existence. Concepts fixed in the meaning of words are formed as

generalised and approximately correct reflections of reality,

therefore in signifying them words reflect reality in their content.

The

acoustic aspect of the word serves to name objects of reality, not to

reflect them. In this sense the word may be regarded as a sign. This

sign, however, is not arbitrary but motivated by the whole process of

its development. That is to say, when a word first comes into

existence it is built out of the elements already available in the

language and according to the existing patterns.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

The etymology of a word refers to its origin and historical development: that is, its earliest known use, its transmission from one language to another, and its changes in form and meaning. Etymology is also the term for the branch of linguistics that studies word histories.

What’s the Difference Between a Definition and an Etymology?

A definition tells us what a word means and how it’s used in our own time. An etymology tells us where a word came from (often, but not always, from another language) and what it used to mean.

For example, according to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, the definition of the word disaster is «an occurrence causing widespread destruction and distress; a catastrophe» or «a grave misfortune.» But the etymology of the word disaster takes us back to a time when people commonly blamed great misfortunes on the influence of the stars.

Disaster first appeared in English in the late 16th century, just in time for Shakespeare to use the word in the play King Lear. It arrived by way of the Old Italian word disastro, which meant «unfavorable to one’s stars.»

This older, astrological sense of disaster becomes easier to understand when we study its Latin root word, astrum, which also appears in our modern «star» word astronomy. With the negative Latin prefix dis- («apart») added to astrum («star»), the word (in Latin, Old Italian, and Middle French) conveyed the idea that a catastrophe could be traced to the «evil influence of a star or planet» (a definition that the dictionary tells us is now «obsolete»).

Is the Etymology of a Word Its True Definition?

Not at all, though people sometimes try to make this argument. The word etymology is derived from the Greek word etymon, which means «the true sense of a word.» But in fact the original meaning of a word is often different from its contemporary definition.

The meanings of many words have changed over time, and older senses of a word may grow uncommon or disappear entirely from everyday use. Disaster, for instance, no longer means the «evil influence of a star or planet,» just as consider no longer means «to observe the stars.»

Let’s look at another example. Our English word salary is defined by The American Heritage Dictionary as «fixed compensation for services, paid to a person on a regular basis.» Its etymology can be traced back 2,000 years to sal, the Latin word for salt. So what’s the connection between salt and salary?

The Roman historian Pliny the Elder tells us that «in Rome, a soldier was paid in salt,» which back then was widely used as a food preservative. Eventually, this salarium came to signify a stipend paid in any form, usually money. Even today the expression «worth your salt» indicates that you’re working hard and earning your salary. However, this doesn’t mean that salt is the true definition of salary.

Where Do Words Come From?

New words have entered (and continue to enter) the English language in many different ways. Here are some of the most common methods.

- Borrowing

The majority of the words used in modern English have been borrowed from other languages. Although most of our vocabulary comes from Latin and Greek (often by way of other European languages), English has borrowed words from more than 300 different languages around the world. Here are just a few examples:

futon (from the Japanese word for «bedclothes, bedding») - hamster (Middle High German hamastra)

- kangaroo (Aboriginal language of Guugu Yimidhirr, gangurru , referring to a species of kangaroo)

- kink (Dutch, «twist in a rope»)

- moccasin (Native American Indian, Virginia Algonquian, akin to Powhatan mäkäsn and Ojibwa makisin)

- molasses (Portuguese melaços, from Late Latin mellceum, from Latin mel, «honey»)

- muscle (Latin musculus, «mouse»)

- slogan (alteration of Scots slogorne, «battle cry»)

- smorgasbord (Swedish, literally «bread and butter table»)

- whiskey (Old Irish uisce, «water,» and bethad, «of life»)

- Clipping or Shortening

Some new words are simply shortened forms of existing words, for instance indie from independent; exam from examination; flu from influenza, and fax from facsimile. - Compounding

A new word may also be created by combining two or more existing words: fire engine, for example, and babysitter. - Blends

A blend, also called a portmanteau word, is a word formed by merging the sounds and meanings of two or more other words. Examples include moped, from mo(tor) + ped(al), and brunch, from br(eakfast) + (l)unch. - Conversion or Functional Shift

New words are often formed by changing an existing word from one part of speech to another. For example, innovations in technology have encouraged the transformation of the nouns network, Google, and microwave into verbs. - Transfer of Proper Nouns

Sometimes the names of people, places, and things become generalized vocabulary words. For instance, the noun maverick was derived from the name of an American cattleman, Samuel Augustus Maverick. The saxophone was named after Sax, the surname of a 19th-century Belgian family that made musical instruments. - Neologisms or Creative Coinages

Now and then, new products or processes inspire the creation of entirely new words. Such neologisms are usually short lived, never even making it into a dictionary. Nevertheless, some have endured, for example quark (coined by novelist James Joyce), galumph (Lewis Carroll), aspirin (originally a trademark), grok (Robert A. Heinlein). - Imitation of Sounds

Words are also created by onomatopoeia, naming things by imitating the sounds that are associated with them: boo, bow-wow, tinkle, click.

Why Should We Care About Word Histories?

If a word’s etymology is not the same as its definition, why should we care at all about word histories? Well, for one thing, understanding how words have developed can teach us a great deal about our cultural history. In addition, studying the histories of familiar words can help us deduce the meanings of unfamiliar words, thereby enriching our vocabularies. Finally, word stories are often both entertaining and thought provoking. In short, as any youngster can tell you, words are fun.

- Top Definitions

- Synonyms

- Quiz

- Related Content

- Examples

- British

- Idioms And Phrases

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

noun

a unit of language, consisting of one or more spoken sounds or their written representation, that functions as a principal carrier of meaning. Words are composed of one or more morphemes and are either the smallest units susceptible of independent use or consist of two or three such units combined under certain linking conditions, as with the loss of primary accent that distinguishes the one-wordblackbird (primary stress on “black”, and secondary stress on “bird”) from black bird (primary stress on both words). Words are usually separated by spaces in writing, and are distinguished phonologically, as by accent, in many languages.

(used in combination with the first letter of an offensive or unmentionable word, the first letter being lowercase or uppercase, with or without a following hyphen): My mom married at 20, and she mentions the m-word every time I meet someone she thinks is eligible.See also C-word, F-word, N-word.

words,

- speech or talk: to express one’s emotion in words;Words mean little when action is called for.

- the text or lyrics of a song as distinguished from the music.

- contentious or angry speech; a quarrel: We had words and she walked out on me.

a short talk or conversation: Marston, I’d like a word with you.

an expression or utterance: a word of warning.

warrant, assurance, or promise: I give you my word I’ll be there.

news; tidings; information: We received word of his death.

a verbal signal, as a password, watchword, or countersign.

an authoritative utterance, or command: His word was law.

Also called machine word. Computers. a string of bits, characters, or bytes treated as a single entity by a computer, particularly for numeric purposes.

(initial capital letter)Also called the Word, the Word of God.

- the Scriptures; the Bible.

- the Logos.

- the message of the gospel of Christ.

a proverb or motto.

verb (used with object)

to express in words; select words to express; phrase: to word a contract with great care.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Idioms about word

at a word, in immediate response to an order or request; in an instant: At a word they came to take the situation in hand.

be as good as one’s word, to hold to one’s promises.

eat one’s words, to retract one’s statement, especially with humility: They predicted his failure, but he made them eat their words.

have a word, to talk briefly: Tell your aunt that I would like to have a word with her.

have no words for, to be unable to describe: She had no words for the sights she had witnessed.

in a word, in summary; in short: In a word, there was no comparison.Also in one word.

in so many words, in unequivocal terms; explicitly: She told them in so many words to get out.

keep one’s word, to fulfill one’s promise: I said I’d meet the deadline, and I kept my word.

man of his word / woman of her word, a person who can be trusted to keep a promise; a reliable person.

(upon) my word! (used as an exclamation of surprise or astonishment.)

of few words, laconic; taciturn: a woman of few words but of profound thoughts.

of many words, talkative; loquacious; wordy: a person of many words but of little wit.

put in a good word for, to speak favorably of; commend: He put in a good word for her with the boss.Also put in a word for.

take one at one’s word, to take a statement to be literal and true.

take the words out of one’s mouth, to say exactly what another person was about to say.

weigh one’s words, to choose one’s words carefully in speaking or writing: It was an important message, and he was weighing his words.

Origin of word

First recorded before 900; Middle English, Old English; cognate with Dutch woord, German Wort, Old Norse orth, orð, Gothic waurd, waúrd, all from Germanic wurdam (unattested); akin to Latin verbum “word,” Greek rhḗtōr (dialect wrḗtōr ) “public speaker, orator, rhetorician,” Old Prussian wirds “word,” Lithuanian var̃das “name”

OTHER WORDS FROM word

in·ter·word, adjectiveout·word, verb (used with object)well-word·ed, adjective

Words nearby word

Worcester china, Worcester sauce, Worcestershire, Worcestershire sauce, Worcs, word, word accent, wordage, word association, word association test, word-blind

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Words related to word

conversation, talk, account, advice, announcement, comment, expression, information, message, news, remark, report, rumor, saying, speech, concept, name, phrase, sound, term

How to use word in a sentence

-

In other words, the large-scale burning this summer shows that these campaigns have yet to effectively prevent deforestation or the subsequent uncontrolled wildfires in Brazil.

-

In this example, I went with the word “shoes” as this is a product listing for shoes.

-

That may feel like a strange word to describe a perennial 50-game winner — one that’s been so good, and so close — with a generational scoring talent.

-

Think of good synonyms or words connected to the brand, without compromising your Google ranking.

-

If you mouse over the word, you’ll see original English word.

-

This is acting in every sense of the word—bringing an unevolved animal to life and making it utterly believable.

-

She vowed to repay the money—no official word, however, on whether she ever did that.

-

But news of the classes is spread mainly by word of mouth, and participants bring along their friends and families.

-

Still other people have moved away from the word “diet” altogether.

-

Back in Iran, he once got word that the Iranians were going to raid a village where his men were stationed.

-

Not a word now,” cried Longcluse harshly, extending his hand quickly towards him; “I may do that which can’t be undone.

-

Every word that now fell from the agitated Empress was balm to the affrighted nerves of her daughter.

-

When we were mounted Mac leaned over and muttered an admonitory word for Piegan’s ear alone.

-

Now for the tempering of the Gudgeons, I leave it to the judgment of the Workman; but a word or two of the polishing of it.

-

Huxley quotes with satirical gusto Dr. Wace’s declaration as to the word «Infidel.»

British Dictionary definitions for word (1 of 3)

noun

one of the units of speech or writing that native speakers of a language usually regard as the smallest isolable meaningful element of the language, although linguists would analyse these further into morphemesRelated adjective: lexical, verbal

an instance of vocal intercourse; chat, talk, or discussionto have a word with someone

an utterance or expression, esp a brief onea word of greeting

news or informationhe sent word that he would be late

a verbal signal for action; commandwhen I give the word, fire!

an undertaking or promiseI give you my word; he kept his word

an autocratic decree or utterance; orderhis word must be obeyed

a watchword or slogan, as of a political partythe word now is «freedom»

computing a set of bits used to store, transmit, or operate upon an item of information in a computer, such as a program instruction

as good as one’s word doing what one has undertaken or promised to do

at a word at once

by word of mouth orally rather than by written means

in a word briefly or in short

my word!

- an exclamation of surprise, annoyance, etc

- Australian an exclamation of agreement

of one’s word given to or noted for keeping one’s promisesI am a man of my word

put in a word for or put in a good word for to make favourable mention of (someone); recommend

take someone at his word or take someone at her word to assume that someone means, or will do, what he or she sayswhen he told her to go, she took him at his word and left

take someone’s word for it to accept or believe what someone says

the last word

- the closing remark of a conversation or argument, esp a remark that supposedly settles an issue

- the latest or most fashionable design, make, or modelthe last word in bikinis

- the finest example (of some quality, condition, etc)the last word in luxury

the word the proper or most fitting expressioncold is not the word for it, it’s freezing!

upon my word!

- archaic on my honour

- an exclamation of surprise, annoyance, etc

word for word

- (of a report, transcription, etc) using exactly the same words as those employed in the situation being reported; verbatim

- translated by substituting each word in the new text for each corresponding word in the original rather than by general sense

word of honour a promise; oath

(modifier) of, relating to, or consisting of wordsa word list

verb

(tr) to state in words, usually specially selected ones; phrase

(tr often foll by up) Australian informal to inform or advise (a person)

Word Origin for word

Old English word; related to Old High German wort, Old Norse orth, Gothic waurd, Latin verbum, Sanskrit vratá command

British Dictionary definitions for word (2 of 3)

noun the Word

Christianity the 2nd person of the Trinity

Scripture, the Bible, or the Gospels as embodying or representing divine revelationOften called: the Word of God

Word Origin for Word

translation of Greek logos, as in John 1:1

British Dictionary definitions for word (3 of 3)

n combining form

(preceded by the and an initial letter) a euphemistic way of referring to a word by its first letter because it is considered to be in some way unmentionable by the userthe C-word, meaning cancer

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Other Idioms and Phrases with word

In addition to the idioms beginning with word

- word for word

- word of honor

- word of mouth, by

- words fail me

- words of one syllable, in

- words stick in one’s throat

- words to that effect

- word to the wise, a

also see:

- actions speak louder than words

- at a loss (for words)

- at a word

- break one’s word

- eat one’s words

- famous last words

- fighting words

- four-letter word

- from the word go

- get a word in edgewise

- give the word

- go back on (one’s word)

- good as one’s word

- hang on someone’s words

- have a word with

- have words with

- in brief (a word)

- in other words

- in so many words

- keep one’s word

- last word

- leave word

- man of his word

- mark my words

- mince matters (words)

- mum’s the word

- not breathe a word

- not open one’s mouth (utter a word)

- of few words

- picture is worth a thousand words

- play on words

- put in a good word

- put into words

- put words in someone’s mouth

- swallow one’s words

- take someone at his or her word

- take the words out of someone’s mouth

- true to (one’s word)

- weasel word

- weigh one’s words

The American Heritage® Idioms Dictionary

Copyright © 2002, 2001, 1995 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Definition of a Word

A word is a speech sound or a combination of sound having a particular meaning for an idea, object or thought and has a spoken or written form. In English language word is composed by an individual letter (e.g., ‘I’), I am a boy, or by combination of letters (e.g., Jam, name of a person) Jam is a boy. Morphology, a branch of linguistics, deals with the structure of words where we learn under which rules new words are formed, how we assigned a meaning to a word? how a word functions in a proper context? how to spell a word? etc.

Examples of word: All sentences are formed by a series of words. A sentence starts with a word, consists on words and ends with a word. Therefore, there is nothing else in a sentence than a word.

Some different examples are: Boy, kite, fox, mobile phone, nature, etc.

Different Types of Word

There are many types of word; abbreviation, acronym, antonym, back formation, Clipped words (clipping), collocation, compound words, Content words, contractions, derivation, diminutive, function word, homograph, homonym, homophone, legalism, linker, conjunct, borrowed, metonym, monosyllable, polysyllable, rhyme, synonym, etc. Read below for short introduction to each type of word.

Abbreviation

An abbreviation is a word that is a short form of a long word.

Example: Dr for doctor, gym for gymnasium

Acronym

Acronym is one of the commonly used types of word formed from the first letter or letters of a compound word/ term and used as a single word.

Example: PIA for Pakistan International Airline

Antonym

An antonym is a word that has opposite meaning of an another word

Example: Forward is an antonym of word backward or open is an antonym of word close.

Back formation

Back formation word is a new word that is produced by removing a part of another word.

Example: In English, ‘tweeze’ (pluck) is a back formation from ‘tweezers’.

Clipped words

Clipped word is a word that has been clipped from an already existing long word for ease of use.

Example: ad for advertisement

Collocation

Collocation is a use of certain words that are frequently used together in form of a phrase or a short sentence.

Example: Make the bed,

Compound words

Compound words are created by placing two or more words together. When compound word is formed the individual words lose their meaning and form a new meaning collectively. Both words are joined by a hyphen, a space or sometime can be written together.

Example: Ink-pot, ice cream,

Content word

A content word is a word that carries some information or has meaning in speech and writing.

Example: Energy, goal, idea.

Contraction

A Contraction is a word that is formed by shortening two or more words and joining them by an apostrophe.

Example: ‘Don’t’ is a contraction of the word ‘do not’.

Derivation

Derivation is a word that is derived from within a language or from another language.

Example: Strategize (to make a plan) from strategy (a plan).

Diminutive

Diminutive is a word that is formed by adding a diminutive suffix with a word.

Example: Duckling by adding suffix link with word duck.

Function word

Function word is a word that is mainly used for expressing some grammatical relationships between other words in a sentence.

Example: (Such as preposition, or auxiliary verb) but, with, into etc.

Homograph

Homograph is a word that is same in written form (spelled alike) as another word but with a different meaning, origin, and occasionally pronounced with a different pronunciation

Example: Bow for ship and same word bow for shooting arrows.

Homonym

Homonyms are the words that are spelled alike and have same pronunciation as another word but have a different meaning.

Example: Lead (noun) a material and lead (verb) to guide or direct.

Homophone

Homophones are the words that have same pronunciation as another word but differ in spelling, meaning, and origin.

Example: To, two, and too are homophones.

Hyponym

Hyponym is a word that has more specific meaning than another more general word of which it is an example.

Example: ‘Parrot’ is a hyponym of ‘birds’.

Legalism

Legalism is a type of word that is used in law terminology.

Example: Summon, confess, judiciary

Linker/ conjuncts

Linker or conjuncts are the words or phrase like ‘however’ or ‘what’s more’ that links what has already been written or said to what is following.

Example: however, whereas, moreover.

Loanword/ borrowed

A loanword or borrowed word is a word taken from one language to use it in another language without any change.

Example: The word pizza is taken from Italian language and used in English language

Metonym

Metonym is a word which we use to refer to something else that it is directly related to that.

Example: ‘Islamabad’ is frequently used as a metonym for the Pakistan government.

Monosyllable

Monosyllable is a word that has only one syllable.

Example: Come, go, in, yes, or no are monosyllables.

Polysyllable

Polysyllable is a word that has two or more than two syllables.

Example: Interwoven, something or language are polysyllables.

Rhyme

Rhyme is a type of word used in poetry that ends with similar sound as the other words in stanza.

Example; good, wood, should, could.

Synonym

Synonym is a word that has similar meaning as another word.

Example: ‘happiness’ is a synonym for ‘joy’.