Inventors get a lot of love. Thomas Edison is held up as a tinkering genius. Steve Jobs is considered a saint in Silicon Valley. Hedy Lamar, meanwhile, may have been a Hollywood star but a new book makes clear her real legacy is in inventing the foundations of encryption. But while all these people invented things, it’s possible to invent something even more fundamental. Take Shakespeare: he invented words. And he invented more words—words that continue to shape the English language—than anyone else. By a long shot.

But what does it mean to “invent” words? How many words did Shakespeare invent? What kind of words? And which words are those exactly? Rather than just listing all the words Shakespeare invented, this post digs deeper into the how and the why (or “wherefore”) of Shakespeare’s literary creations.

How Many Words Did Shakespeare Invent?

1700! My, what a perfectly round number! Such a large and perfectly round number is misleading at best, and is more likely just wrong—there is in fact a bunch of debate about the accuracy of this number.

So who’s to blame for the uncertainty around the number of words Shakespeare invented? For starters, we can blame the Oxford English Dictionary. This famous dictionary (often called the OED for short) is famous, in part, because it provides incredibly thorough definitions of words, but also because it identifies the first time each word actually appeared in written English. Shakespeare appears as the first documented user of more words than any other writer, making it convenient to assume that he was the creator of all of those words.

In reality, though, many of these words were probably part of everyday discourse in Elizabethan England. So it’s highly likely that Shakespeare didn’t invent all of these words; he just produced the first preserved record of some of them. Ryan Buda, a writer at Letterpile, explains it like this:

But most likely, the word was in use for some time before it is seen in the writings of Shakespeare. The fact that the word first appears there does not necessarily mean that he made it up himself, but rather, he could have borrowed it from his peers or from conversations he had with others.

However, while Shakespeare might have been just the first person to write down some words, he definitely did create many words himself, plenty of which we still use to this day. The list a ways down below contains the 420 words that almost certainly originated from Shakespeare himself.

But all this leads to another question. What does it even mean to “invent” a word?

How Did Shakespeare Invent Words?

Some writers invent words in the same way Thomas Edison invented light bulbs: they cobble together bits of sound and create entirely new words without any meaning or relation to existing words. Lewis Carroll does in the first stanza of his “Jabberwocky” poem:

`Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

Carroll totally made up words like “brillig,” “slithy,” “toves,” and “mimsy”; the first stanza alone contains 11 of these made-up words, which are known as nonce words. Words like these aren’t just meaningless, they’re also disposable, intended to be used just once.

Shakespeare did not create nonce words. He took an entirely different approach. When he invented words, he did it by working with existing words and altering them in new ways. More specifically, he would create new words by:

- Conjoining two words

- Changing verbs into adjectives

- Changing nouns into verbs

- Adding prefixes to words

- Adding suffixes to words

The most exhaustive take on Shakespeare’s invented words comes from a nice little 874-page book entitled The Shakespeare Key by Charles and Mary Cowden Clarke. Here’s how they explain Shakespeare’s literary innovations:

Shakespeare, with the right and might of a true poet, and with his peculiar royal privilege as king of all poets, has minted several words that deserve to become current in our language. He coined them for his own special use to express his own special meanings in his own special passages; but they are so expressive and so well framed to be exponents of certain particulars in meanings common to us all, that they deserve to become generally adopted and used.

We can call what Shakespeare did to create new words “minting,” “coining” or “inventing.” Whatever term we use to describe it, Shakespeare was doing things with words that no one had ever thought to do before, and that’s what matters.

Shakespeare Didn’t Invent Nonsense Words

Though today readers often need the help of modern English translations to fully grasp the nuance and meaning of Shakespeare’s language, Shakespeare’s contemporary audience would have had a much easier go of it. Why? Two main reasons.

First, Shakespeare was part of a movement in English literature that introduced more prose into plays. (Earlier plays were written primarily in rhyming verse.) Shakespeare’s prose was similar to the style and cadence of everyday conversation in Elizabethan England, making it natural for members of his audience to understand.

In addition, the words he created were comprehensible intuitively because, once again, they were often built on the foundations of already existing words, and were not just unintelligible combinations of sound. Take “congreeted” for example. The prefix “con” means with, and “greet” means to receive or acknowledge someone.

It therefore wasn’t a huge stretch for people to understand this line:

That, face to face and royal eye to eye.

You have congreeted.(Henry V, Act 5, Scene 2)

Shakespeare also made nouns into verbs. He was the first person to use friend as a verb, predating Mark Zuckerberg by about 395 years.

And what so poor a man as Hamlet is

May do, to express his love and friending to you(Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 5)

Other times, despite his proclivity for making compound words, Shakespeare reached into his vast Latin vocabulary for loanwords.

His heart fracted and corroborate.

(Henry V, Act 2, Scene 1)

Here the Latin word fractus means “broken.” Take away the –us and add in the English suffix –ed, and a new English word is born.

New Words Are Nothing New

Shakespeare certainly wasn’t the first person to make up words. It’s actually entirely commonplace for new words to enter a language. We’re adding new words and terms to our “official” dictionaries every year. In the past few years, the Merriam-Webster dictionary has added several new words and phrases, like these:

- bokeh

- elderflower

- fast fashion

- first world problem

- ginger

- microaggression

- mumblecore

- pareidolia

- ping

- safe space

- wayback

- wayback machine

- woo-woo

So inventing words wasn’t something unique to Shakespeare or Elizabethan England. It’s still going on all the time.

But Shakespeare Invented a Lot of New Words

So why did Shakespeare have to make up hundreds of new words? For starters, English was smaller in Shakespeare’s time. The language contained many fewer words, and not enough for a literary genius like Shakespeare. How many words? No one can be sure. One estimates, one from Encyclopedia Americana, puts the number at 50,000-60,000, likely not including medical and scientific terms.

During Shakespeare’s time, the number of words in the language began to grow. Edmund Weiner, deputy chief editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, explains it this way:

The vocabulary of English expanded greatly during the early modern period. Writers were well aware of this and argued about it. Some were in favour of loanwords to express new concepts, especially from Latin. Others advocated the use of existing English words, or new compounds of them, for this purpose. Others advocated the revival of obsolete words and the adoption of regional dialect.

In Shakespeare’s collected writings, he used a total of 31,534 different words. Whatever the size of the English lexicon at the time, Shakespeare was in command of a substantial portion of it. Jason Kottke estimates that Shakespeare knew around 66,534 words, which suggests Shakespeare was pushing the boundaries of English vocab as he knew it. He had to make up some new words.

The Complete List of Words Shakespeare Invented

Compiling a definitive list of every word that Shakespeare ever invented is impossible. But creating a list of the words that Shakespeare almost certainly invented can be done. We generated list of words below by starting with the words that Shakespeare was the first to use in written language, and then applying research that has identified which words were probably in everyday use during Shakespeare’s time. The result are 420 bona fide words minted, coined, and invented by Shakespeare, from “academe” to “zany”:

- academe

- accessible

- accommodation

- addiction

- admirable

- aerial

- airless

- amazement

- anchovy

- arch-villain

- auspicious

- bacheolorship

- barefaced

- baseless

- batty

- beachy

- bedroom

- belongings

- birthplace

- black-faced

- bloodstained

- bloodsucking

- blusterer

- bodikins

- braggartism

- brisky

- broomstaff

- budger

- bump

- buzzer

- candle holder

- catlike

- characterless

- cheap

- chimney-top

- chopped

- churchlike

- circumstantial

- clangor

- cold-blooded

- coldhearted

- compact

- consanguineous

- control

- coppernose

- countless

- courtship

- critical

- cruelhearted

- Dalmatian

- dauntless

- dawn

- day’s work

- deaths-head

- defeat

- depositary

- dewdrop

- dexterously

- disgraceful

- distasteful

- distrustful

- dog-weary

- doit (a Dutch coin: ‘a pittance’)

- domineering

- downstairs

- dwindle

- East Indies

- embrace

- employer

- employment

- enfranchisement

- engagement

- enrapt

- epileptic

- equivocal

- eventful

- excitement

- expedience

- expertness

- exposure

- eyedrop

- eyewink

- fair-faced

- fairyland

- fanged

- fap

- far-off

- farmhouse

- fashionable

- fashionmonger

- fat-witted

- fathomless

- featureless

- fiendlike

- fitful

- fixture

- fleshment

- flirt-gill

- flowery

- fly-bitten

- footfall

- foppish

- foregone

- fortune-teller

- foul mouthed

- Franciscan

- freezing

- fretful

- full-grown

- fullhearted

- futurity

- gallantry

- garden house

- generous

- gentlefolk

- glow

- go-between

- grass plot

- gravel-blind

- gray-eyed

- green-eyed

- grief-shot

- grime

- gust

- half-blooded

- heartsore

- hedge-pig

- hell-born

- hint

- hobnail

- homely

- honey-tongued

- hornbook

- hostile

- hot-blooded

- howl

- hunchbacked

- hurly

- idle-headed

- ill-tempered

- ill-used

- impartial

- imploratory

- import

- in question

- inauspicious

- indirection

- indistinguishable

- inducement

- informal

- inventorially

- investment

- invitation

- invulnerable

- jaded

- juiced

- keech

- kickie-wickie

- kitchen-wench

- lackluster

- ladybird

- lament

- land-rat

- laughable

- leaky

- leapfrog

- lewdster

- loggerhead

- lonely

- long-legged

- love letter

- lustihood

- lustrous

- madcap

- madwoman

- majestic

- malignancy

- manager

- marketable

- marriage bed

- militarist

- mimic

- misgiving

- misquote

- mockable

- money’s worth

- monumental

- moonbeam

- mortifying

- motionless

- mountaineer

- multitudinous

- neglect

- never-ending

- newsmonger

- nimble-footed

- noiseless

- nook-shotten

- obscene

- ode

- offenseful

- offenseless

- Olympian

- on purpose

- oppugnancy

- outbreak

- overblown

- overcredulous

- overgrowth

- overview

- pageantry

- pale-faced

- passado

- paternal

- pebbled

- pedant

- pedantical

- pendulous

- pignut

- pious

- please-man

- plumpy

- posture

- prayerbook

- priceless

- profitless

- Promethean

- protester

- published

- puking (disputed)

- puppy-dog

- pushpin

- quarrelsome

- radiance

- rascally

- rawboned

- reclusive

- refractory

- reinforcement

- reliance

- remorseless

- reprieve

- resolve

- restoration

- restraint

- retirement

- revokement

- revolting

- ring carrier

- roadway

- roguery

- rose-cheeked

- rose-lipped

- rumination

- ruttish

- sanctimonious

- satisfying

- savage

- savagery

- schoolboy

- scrimer

- scrubbed

- scuffle

- seamy

- self-abuse

- shipwrecked

- shooting star

- shudder

- silk stocking

- silliness

- skim milk

- skimble-skamble

- slugabed

- soft-hearted

- spectacled

- spilth

- spleenful

- sportive

- stealthy

- stillborn

- successful

- suffocating

- tanling

- tardiness

- time-honored

- title page

- to arouse

- to barber

- to bedabble

- to belly

- to besmirch

- to bet

- to bethump

- to blanket

- to cake

- to canopy

- to castigate

- to cater

- to champion

- to comply

- to compromise

- to cow

- to cudgel

- to dapple

- to denote

- to dishearten

- to dislocate

- to educate

- to elbow

- to enmesh

- to enthrone

- to fishify

- to glutton

- to gnarl

- to gossip

- to grovel

- to happy

- to hinge

- to humor

- to impede

- to inhearse

- to inlay

- to instate

- to lapse

- to muddy

- to negotiate

- to numb

- to offcap

- to operate

- to out-Herod

- to out-talk

- to out-villain

- to outdare

- to outfrown

- to outscold

- to outsell

- to outweigh

- to overpay

- to overpower

- to overrate

- to palate

- to pander

- to perplex

- to petition

- to rant

- to reverb

- to reword

- to rival

- to sate

- to secure

- to sire

- to sneak

- to squabble

- to subcontract

- to sully

- to supervise

- to swagger

- to torture

- to un muzzle

- to unbosom

- to uncurl

- to undervalue

- to undress

- to unfool

- to unhappy

- to unsex

- to widen

- tortive

- traditional

- tranquil

- transcendence

- trippingly

- unaccommodated

- unappeased

- unchanging

- unclaimed

- unearthy

- uneducated

- unfrequented

- ungoverned

- ungrown

- unhelpful

- unhidden

- unlicensed

- unmitigated

- unmusical

- unpolluted

- unpublished

- unquestionable

- unquestioned

- unreal

- unrivaled

- unscarred

- unscratched

- unsolicited

- unsullied

- unswayed

- untutored

- unvarnished

- unwillingness

- upstairs

- useful

- useless

- valueless

- varied

- varletry

- vasty

- vulnerable

- watchdog

- water drop

- water fly

- well-behaved

- well-bred

- well-educated

- well-read

- wittolly

- worn out

- wry-necked

- yelping

- zany

Words That Shakespeare Invented – Resource List

- 10 Words Shakespeare Never Invented – Merriam-Webster does a great job dismantling myths. This article, in particular, tells you which words Shakespeare probably didn’t invent.

- 40 Words You Can Trace Back To William Shakespeare – Buzzfeed disregards the “never invented” words from Merriam, but does add a disclaimer: “That doesn’t necessarily mean he invented every word.”

- Invented Words – This page was the center of a disputatious brouhaha with the aforementioned Buzzfeed. As it stands, however, Google likes to deliver this as a top result when you search for “Words Shakespeare Invented.”

- 20 Words We Owe to Shakespeare – I like the way that the author of this article draws a parallel between Shakespeare and the LOL generation.

- Words and Phrases Coined by Shakespeare – This is a lengthy and straightforward list that mostly contains phrases rather than individual words.

- 21 everyday phrases that come straight from Shakespeare’s plays – This is a helpful resource due to the explanation of each phrase.

Words, words, words.

(Hamlet Act 2, Scene 2)

Skip to content

William Shakespeare has made a great contribution to the English language. What role did Shakespeare play in the development of vocabulary? Shakespeare invented words by changing common words into nouns, verbs, or adjectives. As you can observe, some of Shakespeare words have either prefixes or suffixes. So, how many words did Shakespeare invent? There are more than 1700 words created by Shakespeare that we can see in his writings.

William Shakespeare may have invented thousands of words, however, some argued that some of these words might not have been invented by him. Instead, this list of Shakespeare vocabulary was actually first written on his works. Most scholars argued that these words which are credited to Shakespeare might have been spoken first. This contraversial topic may be a great idea for a thesis. Our thesis writers can help you handle it. Do you know what words did Shakespeare invent? Here, we will give you some of these words with its corresponding meanings.

Do You Know Some Shakespeare Words And Meanings?

Here are 50 words invented by Shakespeare. If you’d like to improve your writing skills, we advise you to learn and use them. Each word has its corresponding meaning. These words Shakespeare created has been used in one of his plays:

- Accommodation – means adaptation, adjustment, or compromise. Used in “Measure for Measure” – “For all the accommodations that thou bear’st Are nursed by baseness.”

- Addiction – meaning obsession or dependence. This is a common word that is usually used in celebrity news. However, it was first used in “Othello” – “what sport and revels his addiction leads him”

- Agile – means capable of moving instantly or easily. Can be found in “Romeo and Juliet” – “His agile arm beats down their fatal points.”

- Allurement – refers to enticement, appeal, or attraction. It was used in “All’s Well That Ends Well” – “one Diana, to take heed of the allurement of one Count Rousillon”.

- Antipathy – this is one of the words coined by Shakespeare that means to hate or dislike. Used in “King Lear” – “No contraries hold more antipathy Than I”.

- Arch-villain – by adding the prefix “arch-”: Shakespeare created this word that means a very mean person. He used this in “Timon of Athens” – “yet an arch-villain keeps him company”.

- Assassination – this term is used to describe a violent murder or killing. It was observed in “Macbeth” – “if the assassination could trammel up the consequence”.

- Bedazzled – this word was first used to describe the gleam of sunlight. But presently it is used for marketing rhinestone-embellished jeans. Has been used in “The Taming of the Shrew” – “my mistaking eyes, that have been so bedazzled with the sun”.

- Belongings – refers to possessions or properties. This is one of the words made by Shakespeare that can be seen in “Measure for Measure” – “thy belongings are not thine own”.

- Catastrophe – refers to disaster or the spectacular event that started the outcome of the story. You can read this in “King Lear” – “he comes, like the catastrophe of the old comedy.”

- Cold-blooded – most often this word is used to depict serial killers and vampires. But it was first used in “King John” – “Thou cold-blooded slave, hast thou not spoke”.

- Critical – very significant or prone to criticism. It was used in “Othello” – “For I am nothing, if not critical.”

- Demonstrate – to display, show, or present something. Also used in “Othello” – “this may help to thicken other proofs That do demonstrate thinly.”

- Dexterously – skillfully created or done with accuracy. Can be found in “Twelfth Night” – “Dexterously, good madonna.”

- Dire – means dreadful, miserable, or ominous. Used in “Comedy of Errors” – “To bear the extremity of dire mishap!”

- Dishearten – means to disappoint or dismay. The opposite or hearten is first used in “Henry V” – lest he, by showing it, should dishearten his army”

- Dislocate – means to make it out of place. This is shown in “King Lear” – “to dislocate and tear Thy flesh and bones.”

- Emphasis – it means giving attention to something or making it prominent. Can be seen in “Antony and Cleopatra” – “Be choked with such another emphasis!”

- Eventful – it is used to describe a momentous or exciting moment. It was expressed in “As You Like It” – “that ends this strange eventful history”

- Eyeballs – is another word for the eyes. Used in “As You Like It” – “Your bugle eyeballs, nor your cheek of cream,”

- Emulate – means to copy or imitate something. Can be read in “Merry Wives of Windsor” – “I see how thine eye would emulate the diamond”.

- Exist – means to obtain a reality. Used in “King Lear” – “From whom we do exist and cease to be;”

- Extract – means to withdraw, eliminate, draw out. This is depicted in “Henry V” – “Could out of thee extract one spark of evil”.

- Fashionable – it means stylish or trendy. Centuries ago it was used in “Troilus and Cressida” – “For time is like a fashionable host”.

- Frugal – refers to a person who is economical, thrifty, stingy. It was used in “Merry Wives of Windsor” – “I was then frugal of my mirth”.

- Half-blooded – having a relationship with one parent only. First used in “King Lear” – “Half-blooded fellow, yes.”

- Hot-blooded – being passionate or showing extreme feelings. Also used in “King Lear” – “the hot-blooded France, that dowerless took our youngest born”.

- Hereditary – something that you have inherited, congenital. This is evident in “Antony and Cleopatra” – “Hereditary, rather than purchased”.

- Horrid – means horrible or dreadful. One of the common Shakespeare words that was used in “Hamlet” – “cleave the general ear with horrid speech“.

- Impertinent – refers to being insolent, irrelevant, disrespectful. This is apparent in “Tempest” – “the suit is impertinent to myself”.

- Inaudible – refers to being silent or imperceptible. Was first expressed in “All’s Well That Ends Well” – on our quick’st decrees the inaudible and noiseless foot of Time”.

- Jovial – means being happy, cheerful, or jolly. Is used in “Macbeth” – “Be bright and jovial among your guests”.

- Ladybird – refers to a small, round beetle. But during Shakespeare’s time, it does not probably refer to the beetle, but rather it could mean “sweetheart”. It was mentioned in “Romeo and Juliet” – “What, lamb! What, ladybird!”.

- Manager – meaning the administrator or the person who runs the company. It was used to depict as such in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” – “Where is our usual manager of mirth?”.

- Meditate – means to ponder, contemplate, or think. This is expressed in “Twelfth Night” – “I will meditate the while upon some horrid message”.

- Modest – means shy, moderate, or humble. It is used in “Coriolanus” – “but hunt With modest warrant”.

- Multitudinous – it means “a lot” or “too many”. Used in “Macbeth” – “this my hand will rather the multitudinous seas in incarnadine”.

- Mutiny – refers to revolution, uprising, or resistance. Is it found in “Julius Caesar” – “To such a sudden flood of mutiny”.

- New-fangled – it is used for describing the latest or the newest. Used in “Love’s Labour’s Lost” – “I no more desire a rose than wish a snow in May’s new-fangled mirth”.

- Obscene – means something indecent, immoral, or offensive. Can be observed in “Richard II” – “show so heinous, black, obscene a deed!”

- Pageantry – one of the words that Shakespeare created to describe a lavish show. It was described in “Pericles, Prince of Tyre” – “that you aptly will suppose what pageantry”.

- Pedant – someone who is perfectionist or formalist. It is used in “Twelfth Night” – “like a pedant that keeps a school”.

- Pell-mell – means something disordered, clutter, or in chaos. Used in “Love’s Labour’s Lost” – “Pell-mell, down with them!”

- Premeditated – something that is planned, intended, or deliberate. From “Henry V” – “have on them the guilt of premeditated and contrived murder”.

- Reliance – refers to assurance or dependence. From “Timon of Athens” – “And my reliances on his fracted dates”.

- Scuffle – refers to a brawl or a fight. It was first introduced in “Antony and Cleopatra” – “His captain’s heart, which in the scuffles of great fights”.

- Submerged – means immerse, sink, or underwater. This is used in “Antony and Cleopatra” – “So half my Egypt were submerged and made”.

- Swagger – means someone who is bragging or boasting. It was used in “Henry V” – “a rascal that swaggered with me last night”.

- Uncomfortable – feeling awkward or uneasy. This word was mentioned in “Romeo and Juliet” – “Uncomfortable time, why camest thou now”.

- Vast – something that is ample, very large or wide in range. Used in “Timon of Athens” – “with his great attraction Robs the vast sea”.

We hope that you have learned something from this Shakespeare words list. Knowing how many words did Shakespeare invented will make us wonder, is it also possible that we could create our new words and be understood?

Undeniably, whether or not he was the first to write down this list of words Shakespeare invented, he is still responsible for making them popular.

Even today, Shakespeare’s writings still continue to live on in our culture and tradition. It’s probably because his influence has become an important part in the development of our English language. It seems that Shakespeare’s writings have been deeply implanted in our culture, making it hard to image having a modern literature without his influence.

William Shakespeare used more than 20,000 words in his plays and poems, and his works provide the first recorded use of over 1,700 words in the English language. It is believed that he may have invented or introduced many of these words himself, often by combining words, changing nouns into verbs, adding prefixes or suffixes, and so on. Some words stuck around and some didn’t.

Although lexicographers are continually discovering new origins and earliest usages of words, below are listed words and definitions we still use today that are widely attributed to Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s Words A-Z

Alligator: (n) a large, carnivorous reptile closely related to the crocodile

Romeo and Juliet, Act 5 Scene 1

Bedroom: (n) a room for sleeping; furnished with a bed

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 2 Scene 2

Critic: (n) one who judges merit or expresses a reasoned opinion

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 3 Scene 1

Downstairs: (adv) on a lower floor; down the steps

Henry IV Part 1, Act 2 Scene 4

Eyeball: (n) the round part of the eye; organ for vision

Henry VI Part 1, Act 4 Scene 7

Fashionable: (adj) stylish; characteristic of a particular period

Troilus and Cressida, Act 3 Scene 3

Gossip: (v) to talk casually, usually about others

The Comedy of Errors, Act 5 Scene 1

Hurry: (v) to act or move quickly

The Comedy of Errors, Act 5 Scene 1

Inaudible: (adj) not heard; unable to be heard

All’s Well That Ends Well, Act 5 Scene 3

Jaded: (adj) worn out; bored or past feeling

Henry VI Part 2, Act 4 Scene 1

Kissing: (ppl adj) touching with the lips; exchanging kisses

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 5 Scene 2

Lonely: (adj) feeling sad due to lack of companionship

Coriolanus, Act 4 Scene 1

Manager: (n) one who controls or administers; person in charge

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 1 Scene 2

Nervy: (adj) sinewy or strong; bold; easily agitated

Coriolanus, Act 2 Scene 1

Obscene: (adj) repulsive or disgusting; offensive to one’s morality

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 1 Scene 1

Puppy dog: (n) a young, domestic dog

King John, Act 2 Scene 1

Questioning: (n) the act of inquiring or interrogating

As You Like It, Act 5 Scene 4

Rant: (v) to speak at length in inflated or extravagant language

Hamlet, Act 5 Scene 1

Skim milk: (n) milk with its cream removed

Henry IV Part 1, Act 2 Scene 3

Traditional: (adj) conventional; long-established, bound by tradition

Richard III, Act 3 Scene 1

Undress: (v) to remove clothes or other covering

The Taming of the Shrew, Induction Scene 2

Varied: (adj) incorporating different types or kinds; diverse

Titus Andronicus, Act 3 Scene 1

Worthless: (adj) having no value or merit; contemptible

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act 4 Scene 2

Xantippe: (n) shrewish wife of Socrates; figuratively, a bad-tempered woman

The Taming of the Shrew, Act 1 Scene 2

Yelping: (adj) uttering sharp, high-pitched cries

Henry VI Part 1, Act 4 Scene 2

Zany: (n) clown’s assistant; performer who mimics another’s antics

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act 5 Scene 2

Want to know all about the words Shakespeare invented? We’ve got you covered.

In all of his works – the plays, the sonnets and the narrative poems – Shakespeare uses 17,677 different words.

How Many Words Did Shakespeare Invent?

Across all of his written works, it’s estimated that words invented by Shakespeare number as many as 1,700. We say these are words invented by Shakespeare , though in reality many of these 1,700 words would likely have been in common use during the Elizabethan and Jacobean era, just not written down prior to Shakespeare using them in his plays, sonnets and poems. In these cases Shakespeare would have been the first known person to document these words in writing.

Historian Jonathan Hope also points out that Victorian scholars who read texts for the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary read Shakespeare’s texts more thoroughly than most, and cited him more often, meaning Shakespeare is often credited with the first use of words which can be found in other writers.

Examples Of Commonly Used Words Shakespeare Created

It is Shakespeare who is credited with creating the below list of words that we still use in our daily speech – some of them frequently.

accommodation

aerial

amazement

apostrophe

assassination

auspicious

baseless

bloody

bump

castigate

changeful

clangor

control (noun)

countless

courtship

critic

critical

dexterously

dishearten

dislocate

dwindle

eventful

exposure

fitful

frugal

generous

gloomy

gnarled

hurry

impartial

inauspicious

indistinguishable

invulnerable

lapse

laughable

lonely

majestic

misplaced

monumental

multitudinous

obscene

palmy

perusal

pious

premeditated

radiance

reliance

road

sanctimonious

seamy

sportive

submerge

suspicious

Along with these everyday words invented by Shakespeare, he also created a number of words in his plays that never quite caught on in the same way… Shakespearean words like ‘Armgaunt’, ‘Eftes’, ‘Impeticos’, ‘Insisture’, ‘Pajock’, ‘Pioned’ ‘Ribaudred’ and ‘Wappened’. We do have some ideas as to what these words may mean, though much is guesswork. Watch the video below for more insight into words Shakespeare invented that have been lost in the mists of time:

And it wasn’t just words that Shakespeare created, documented, or brought into common usage – he also put words together and created a host of new phrases. Read all about the phrases that Shakespeare invented here. And see our complete Shakespeare dictionary, which lists hundreds of commonly used Shakespeare’s words that arent; so common today, along with a simple definition.

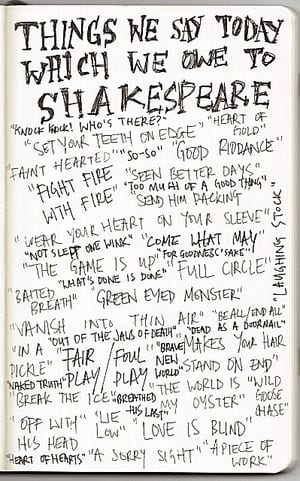

Shakespeare words – see handwritten phrases and words Shakespeare invented

Английские слова, которые придумал Шекспир

Время на прочтение

7 мин

Количество просмотров 14K

Уильям Шекспир вошел в книгу рекордов Гиннесса как самый продаваемый драматург. Через 400 лет после его смерти количество проданных копий его пьес превысило 4 миллиарда. Еще Шекспир занимает почетное третье место в топе самых переводимых авторов за всю историю литературы, уступив только Жюлю Верну и Агате Кристи.

Но сегодня мы поговорим о другом его достижении. Ведь Шекспир считается создателем больше 1700 слов, которые вошли в обиход английского языка. Это абсолютный рекорд. И о некоторых словах, вышедших из-под пера великого писателя, мы сегодня расскажем.

Исторический контекст словотворения Шекспира

Уильям Шекспир жил и трудился во второй половине XVI – первой половине XVII века. И как раз в этот период английский язык активно менялся. Под влиянием книгопечатников был принят единый Стандарт королевской канцелярии, который устанавливал статус государственного диалекта и правила написания отдельных слов.

Изменения в среднеанглийском языке были огромные. Английский активно поглощал заимствованные слова из греческого, иврита, латыни и еще целого ряда языков, благодаря дипломатии, активной колонизации и военным конфликтам. Но единого формата и правил словотворения не было — все происходило хаотично. Об этом мы подробно описали в этой статье, поэтому не будем останавливаться.

Уильям Шекспир был прогрессистом. Он полностью отринул среднеанглийский и писал на новом варианте языка, который сейчас называют ранненовоанглийским.

Строгих грамматических и лексических норм еще не было, поэтому Шекспир получил максимальную свободу творчества. Для удобства рифмования и передачи смыслов он активно создавал новые лексемы, сливая несколько слов в одно, добавляя суффиксы и префиксы, превращая одну часть речи в другую. Или же внаглую перетаскивая лексемы из других языков. Интернета тогда не было, приходилось развлекаться, как получится.

Во многом благодаря ему современный английский звучит именно так, как звучит.

Очень многие лексемы, которые сегодня воспринимаются как «обычные», создал именно Шекспир. В его время это были ого-го какие неологизмы. Но все 1700 слов разбирать не будем, возьмем только семь из них.

Bandit

Бандит, разбойник

Впервые слово встречается в пьесе «Генрих VI, часть вторая». И здесь Шекспир, не мудрствуя лукаво, берет итальянское слово banditto и без изменений вставляет его в свое произведение.

Earl of Suffolk. Come, soldiers, show what cruelty ye can,

That this my death may never be forgot!

Great men oft die by vile bezonians:

A Roman sworder and banditto slave

Murder’d sweet Tully; Brutus’ bastard hand

Stabb’d Julius Caesar; savage islanders

Pompey the Great; and Suffolk dies by pirates.Перевод Е. Бируковой, издание 1957 г.

Капитан: Так проявите всю жестокость вашу,

Чтоб смерть мою вовек не позабыли!

Великие порой от подлых гибнут.

Разбойник, гладиатор, римский раб

Зарезал Туллия; бастардом Брутом

Заколот Юлий Цезарь; дикарями –

Помпеи, а Сеффолка убьют пираты.

А что до тех, кому назначен выкуп,

Хочу я, чтоб один отпущен был. –

Идите вы за мной, а он уйдет.

В дальнейшем Шекспир еще раз использовал слово в пьесе «Жизнь Тимона Афинского», но уже во множественном числе. Его он тоже «позаимствовал» из итальянского — banditti.

После итальянский суффикс перестали использовать, приблизив написание слов ближе к английскому — bandit.

До этого для обозначения «бандитов» в английском языке существовали слова robber и brigand.

Bloody

Кровавый, чертовский

Любимое британское выражение «Bloody hell» было бы невозможным без Шекспира. Впервые он использовал его в пьесе «Как вам это понравится» (As You Like It).

Orlando. What, wouldst thou have me go and beg my food,

Or with a base and boist’rous sword enforce

A thievish living on the common road?

This I must do, or know not what to do;

Yet this I will not do, do how I can.

I rather will subject me to the malice

Of a diverted blood and bloody brother.Перевод Ю. Лифшица

Орландо. Ты предлагаешь мне пойти с сумой?

Иль на большой дороге промышлять

При помощи презренного меча?

Осталось это, больше ничего.

Но нет! Умру — на это не пойду!

И пусть кровавый брат меня убьет,

Пусть кровь мою он пьет, братоубийца!

Интересно, что bloody у Шекспира почти всегда в переносном смысле. Всего Шекспир использовал его 218 раз, и в 205 из них слово значит «чертов» или «чертовски». И лишь 13 раз — «окровавленный».

Этимология простая — взять слово blood и добавить к нему суффикс, который превращает существительное в прилагательное. Если раньше не додумались — то это проблемы лингвистов. Ну а переносное значение — это интересная придумка автора, которая аукается и сегодня.

Critic

Критик, осуждающий

Это слово Шекспир беззастенчиво стащил из французского языка. В оригинале оно писалось critique и означало «судья, цензор». Поэт же взял лексему в том значении, в котором знаем мы ее сейчас — «критик», «человек, который нелестно отзывается о чем-то».

O me, with what strict patience have I sat,

To see a king transformed to a gnat!

To see great Hercules whipping a gig,

And profound Solomon to tune a jig,

And Nestor play at push-pin with the boys,

And critic Timon laugh at idle toys!

Where lies thy grief, O, tell me, good Dumain?

And gentle Longaville, where lies thy pain?

And where my liege’s? all about the breast:

A caudle, ho!Перевод Ю Корнеева

О, как я долго молча возмущался

Тем, что монарх в букашку превращался.

Что на скрипице Геркулес пиликал,

Что джигу мудрый Соломон мурлыкал,

Что Нестор в чехарду с детьми играл

И что Тимон их игры одобрял!

Дюмен любезный, что за мрачный вид?

Лонгвиль, признайтесь, что у вас болит?

У вас, король? Живот? Грудная клетка?

Эй, рвотного!

К сожалению, в переводе лексема потерялась совсем. И «критик Тимон» превратился просто в Тимона. А ведь здесь скрыта явная отсылка на мизантропа и циника Тимона Афинского, о жизни которого Шекспир позже написал пьесу.

А еще Шекспир один раз использовал слово critic в качестве глагола — «критиковать». Его можно найти в сонете 112.

Ginger

Имбирь

Название имбиря претерпело очень много изменений в английском. Когда лексема только попала из латыни, она звучала как zíngiber (или zingiberi). Именно такое научное название имбирь сегодня носит — род растений называется Zíngiber, а знакомый нам острый корень, который подают к суши, — Zingiber officinale.

Вот только это «официальное название». На вульгарной или упрощенной латыни лексема уже другая — gingiber. В Англии она вытеснила «правильное» название имбиря. А ближе к XV веку и вовсе превратилась в gingifer.

Шекспир укоротил лексему, из чего получилось ginger. Вот, к примеру, фраза из пьесы «Генрих VI, часть I».

I have a gammon of bacon and two razors of ginger,

to be delivered as far as Charing-cross.Пер. Е. Бируковой

Мне надобно доставить в Черинг‐Кросс окорок ветчины да

два тюка имбиря.

Интересно, что автор пошел дальше и придумал слово gingerly, значение которого можно понять как «робко» или «насторожено».

Gossip

Сплетня

Неожиданно, но «сплетня» в английском — это лексический родственник «крестного отца». В староанглийском лексема godsib означала «крестный родитель» — это сокращение от «God sibb».

Кстати, отсюда пошло и слово sibling, о котором мы рассказали здесь.

В XIII веке godsib получило еще одно значение — «приятель, друг», но в довольно узком смысле — «люди, которые пришли на крещение ребенка». Так как это были преимущественно женщины, то во времена Шекспира стал популярен еще один смысл — «легкий разговор о других людях». Его и взял за основу автор при создании новой лексемы gossip.

Формально он просто взял довольно редкое слово и одно из его значений, немного изменил написание — и готово.

Впервые Шекспир использовал лексему в одной из первых своих комических пьес — «Комедии ошибок».

Solinus. With all my heart, I’ll gossip at this feast.

Пер. А Некора

Герцог. Всем сердцем принимаю приглашенье.

В дословном переводе было бы: «С удовольствием посплетничаю на этом празднике». Интересно, что само слово «сплетничать» не несло никаких негативных коннотаций. Оно всего лишь касалось обсуждения чей-то жизни или поступков.

Но уже в «Зимней сказке», которая была написана примерно через 18 лет после «Комедии ошибок», Шекспир уже использует gossip в негативном контексте, как «сплетню».

Так что сам автор искал наиболее подходящие способы использования тех слов, которые сам и придумал.

Lonely

Одинокий

Одно из слов, придуманное уже почти на закате карьеры. Шекспир взял обычное слово alone — «один» и трансформировал в lonely — «одинокий». При этом значение хоть и осталось примерно похожим, но изменилось в нюансах.

Alone — это физически один, а lonely — одинокий, чувствующий одиночество.

Впервые автор использовал его в не слишком известной на русскоязычных просторах пьесе «Кориолан» или «Трагедия о Кориолане», как еще переводят название.

My mother, you wot well

My hazards still have been your solace: and

Believe’t not lightly—though I go alone,

Like to a lonely dragon, that his fen

Makes fear’d and talk’d of more than seen—your son

Will or exceed the common or be caught

With cautelous baits and practise.

К сожалению, в единственном изданном переводе «Кориолана» на русский переводчик выбросил целый кусок сцены, в котором и встречалось слово lonely. Поэтому попробуем перевести эту часть самостоятельно:

…though I go alone, Like to a lonely dragon

впрочем, я иду один, как к одинокому дракону

Здесь становится ясно, зачем Шекспиру понадобилось новое слово, если и старое вроде бы нормальное. Но именно здесь заметна разница между alone и lonely. А после лексема вошла в обиход и ее стали использовать другие поэты и писатели.

Manager

Управляющий

Слово кажется современным, но его придумал Шекспир. Неожиданно, но правда. Хотя по смыслу в оригинале оно ближе не к «управляющему», а к «повелителю». То есть, к человеку, который чем-нибудь владеет, а не просто может управлять.

Точно с этим значением слово появляется в пьесе «Бесплодные усилия любви»:

Adieu, valour! rust rapier!

be still, drum! for your manager is in love; yea,

he loveth. Assist me, some extemporal god of rhyme,

for I am sure I shall turn sonnet. Devise, wit;

write, pen; for I am for whole volumes in folio.Перевод Ю. Корнеева

Прощай, мужество! Ржавей, клинок! Умолкни,

барабан! Повелитель ваш влюблен. Да, он любит! Приди мне

на помощь, гений импровизации. Я, вне всякого сомнения,

примусь сочинять сонеты. Изощряйся, ум! Строчи, перо! Я

расположен заполнить целые фолианты!

Сама лексема была создана из глагола manage, которое в XVI веке означало «управлять лошадью». А manage в свою очередь сформировалось из глагола man — кстати, в значении «управлять» он используется и сегодня.

К примеру, во фразе «The old man the boat». Сможете перевести ее правильно с первого раза? Проверьте тут.

Шекспира не зря называют главным поэтом англоязычного мира. Ведь именно он стоял у истоков современного английского и вложил огромное количество усилий в его развитие.

Пьесами Шекспира вдохновлялись десятки и сотни поэтов и прозаиков, именно благодаря ему в английском языке появилась культура создания неологизмов, которая в ходу и сейчас.

Хотите разобраться со всеми нюансами английского языка от Шекспира до наших дней? Регистрируйтесь на бесплатный онлайн-урок с преподавателем и изучайте английский с удовольствием.

Онлайн-школа EnglishDom.com — вдохновляем выучить английский через технологии и человеческую заботу

Только для читателей Хабра первый урок с преподавателем в интерактивном цифровом учебнике бесплатно! А при покупке занятий получите до 3 уроков в подарок!

Получи целый месяц премиум-подписки на приложение ED Words в подарок. Введи промокод december_2021 на этой странице или прямо в приложении ED Words. Промокод действителен до 10.01.2022.

Наши продукты:

-

Учи английские слова в мобильном приложении ED Words

-

Учи английский от А до Z в мобильном приложении ED Courses

-

Установи расширение для Google Chrome, переводи английские слова в интернете и добавляй их на изучение в приложении Ed Words

-

Учи английский в игровой форме в онлайн тренажере

-

Закрепляй разговорные навыки и находи друзей в разговорных клубах

-

Смотри видео лайфхаки про английский на YouTube-канале EnglishDom