Is it correct to say “A world with no borders, no time and no place.“?

Why do I get the feeling that “boundaries” is a better word choice in this case? Also is it better to say “A world without borders“?

Which word combination should I use in this sentence?

The context is an attempt to explain how some companies believe in sharing educational knowledge around the world. Here is more of the paragraph:

“We see the world coming together in the virtual realm to share knowledge that will raise us all up to a higher level: A world with no borders, no time and no place, where each individual has their own special spark to contribute to the new discourse taking place.”

Answer

A world with ‘no time’ and ‘no place’ would not be a world anyone would be capable of perceiving or living in—so I assume that what you mean is no borders (or boundaries) in either or space: neither time nor space is divided by any boundaries (or borders).

Border in English generally denotes the area adjoining a boundary: the decorated edging on a piece of cloth or on a garment, or the border area alongside a national or district boundary. Border as a designation for the line separating two areas is by and large reserved for national boundaries: we speak of border crossings and border guards and the US-Canada border. The name of the French organization Medecins sans frontieres is translated Doctors Without Borders.

I think boundary probably fits your need better, unless you are writing specifically of national boundaries. In particular, we speak of boundless or unbounded freedom or opportunity, which seem to be the sort of connotations you want. And boundaries is a more sonorous word, if you are writing for the ear.

So: a world without boundaries of time or of space has a nice rhythm; alternatively, a world unbounded in time or space flows a bit quicker.

Attribution

Source : Link , Question Author : Alon Eitan , Answer Author : StoneyB on hiatus

Is it correct to say «A world with no borders, no time and no place.«?

Why do I get the feeling that «boundaries» is a better word choice in this case? Also is it better to say «A world without borders«?

Which word combination should I use in this sentence?

The context is an attempt to explain how some companies believe in sharing educational knowledge around the world. Here is more of the paragraph:

«We see the world coming together in the virtual realm to share knowledge that will raise us all up to a higher level: A world with no borders, no time and no place, where each individual has their own special spark to contribute to the new discourse taking place.»

J.R.♦

109k9 gold badges160 silver badges288 bronze badges

asked Feb 25, 2013 at 21:06

1

A world with ‘no time’ and ‘no place’ would not be a world anyone would be capable of perceiving or living in—so I assume that what you mean is no borders (or boundaries) in either or space: neither time nor space is divided by any boundaries (or borders).

Border in English generally denotes the area adjoining a boundary: the decorated edging on a piece of cloth or on a garment, or the border area alongside a national or district boundary. Border as a designation for the line separating two areas is by and large reserved for national boundaries: we speak of border crossings and border guards and the US-Canada border. The name of the French organization Medecins sans frontieres is translated Doctors Without Borders.

I think boundary probably fits your need better, unless you are writing specifically of national boundaries. In particular, we speak of boundless or unbounded freedom or opportunity, which seem to be the sort of connotations you want. And boundaries is a more sonorous word, if you are writing for the ear.

So: a world without boundaries of time or of space has a nice rhythm; alternatively, a world unbounded in time or space flows a bit quicker.

answered Feb 25, 2013 at 23:26

StoneyB on hiatusStoneyB on hiatus

174k13 gold badges257 silver badges453 bronze badges

Mostly ditto on StoneyB. I’d just like to add that «no time and no place» really makes no sense in this context. «A world with no time and no place» sounds like some kind of science fiction story about a realm of disembodied minds or something. It does not indicate a lack of limitations but rather an other-worldliness.

I presume your intent is to say something like «a world not limited by time and place». But even that doesn’t really make sense in context. I’m not sure whether by «no borders» you mean sharing knowledge across national borders, cultural or ethnic boundaries, across professions, etc. Or maybe you mean all of these. In a sense then, you would be removing or overcoming limitations of place. But what does this have to do with time? I don’t suppose that you are sharing knowledge with the ancient Romans or with people from the future, unless these companies you are talking about have invented time travel.

Perhaps if I read the whole context this would make sense. Perhaps you explain later. If not, though, you probably want to reword this part.

answered Feb 26, 2013 at 15:41

JayJay

59.5k1 gold badge63 silver badges128 bronze badges

You must log in to answer this question.

Not the answer you’re looking for? Browse other questions tagged

.

Not the answer you’re looking for? Browse other questions tagged

.

All strong writers have something in common: they understand the value of word choice in writing. Strong word choice uses vocabulary and language to maximum effect, creating clear moods and images and making your stories and poems more powerful and vivid.

The meaning of “word choice” may seem self-explanatory, but to truly transform your style and writing, we need to dissect the elements of choosing the right word. This article will explore what word choice is, and offer some examples of effective word choice, before giving you 5 word choice exercises to try for yourself.

Word Choice Definition: The Four Elements of Word Choice

The definition of word choice extends far beyond the simplicity of “choosing the right words.” Choosing the right word takes into consideration many different factors, and finding the word that packs the most punch requires both a great vocabulary and a great understanding of the nuances in English.

Choosing the right word involves the following four considerations, with word choice examples.

1. Meaning

Words can be chosen for one of two meanings: the denotative meaning or the connotative meaning. Denotation refers to the word’s basic, literal dictionary definition and usage. By contrast, connotation refers to how the word is being used in its given context: which of that word’s many uses, associations, and connections are being employed.

A word’s denotative meaning is its literal dictionary definition, while its connotative meaning is the web of uses and associations it carries in context.

We play with denotations and connotations all the time in colloquial English. As a simple example, when someone says “greaaaaaat” sarcastically, we know that what they’re referring to isn’t “great” at all. In context, the word “great” connotes its opposite: something so bad that calling it “great” is intentionally ridiculous. When we use words connotatively, we’re letting context drive the meaning of the sentence.

The rich web of connotations in language are crucial to all writing, and perhaps especially so to poetry, as in the following lines from Derek Walcott’s Nobel-prize-winning epic poem Omeros:

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez,

the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane

down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain

marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

Sugar cane isn’t, literally, made of “feathered lances,” which would literally denote “long metal spears adorned with bird feathers”; but feathered connotes “branching out,” the way sugar cane does, and lances connotes something tall, straight, and pointy, as sugar cane is. Together, those two words create a powerfully true visual image of sugar cane—in addition to establishing the martial language (“spears,” “marching”) used elsewhere in the passage.

Whether in poetry or prose, strong word choice can unlock images, emotions, and more in the reader, and the associations and connotations that words bring with them play a crucial role in this.

2. Specificity

Use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description.

In the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms. That’s why it’s important to use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description. Words like “good,” “average,” and “awful” are far less descriptive and specific than words like “liberating” (not just good but good and freeing), “C student” (not just average but academically average), and “despicable” (not just awful but morally awful). These latter words pack more meaning than their blander counterparts.

Since more precise words give the reader added context, specificity also opens the door for more poetic opportunities. Take the short poem “[You Fit Into Me]” by Margaret Atwood.

You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

A fish hook

An open eye

The first stanza feels almost romantic until we read the second stanza. By clarifying her language, Atwood creates a simple yet highly emotive duality.

This is also why writers like Stephen King advocate against the use of adverbs (adjectives that modify verbs or other adjectives, like “very”). If your language is precise, you don’t need adverbs to modify the verbs or adjectives, as those words are already doing enough work. Consider the following comparison:

Weak description with adverbs: He cooks quite badly; the food is almost always extremely overdone.

Strong description, no adverbs: He incinerates food.

Of course, non-specific words are sometimes the best word, too! These words are often colloquially used, so they’re great for writing description, writing through a first-person narrative, or for transitional passages of prose.

3. Audience

Good word choice takes the reader into consideration. You probably wouldn’t use words like “lugubrious” or “luculent” in a young adult novel, nor would you use words like “silly” or “wonky” in a legal document.

This is another way of saying that word choice conveys not only direct meaning, but also a web of associations and feelings that contribute to building the reader’s world. What world does the word “wonky” help build for your reader, and what world does the word “seditious” help build? Depending on the overall environment you’re working to create for the reader, either word could be perfect—or way out of place.

4. Style

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing. Every writer uses words differently, and as those words come to form poems, stories, and books, your unique grasp on the English language will be recognizable by all your readers.

Style isn’t something you can point to, but rather a way of describing how a writer writes. Ernest Hemingway, for example, is known for his terse, no-nonsense, to-the-point styles of description. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, is known for writing that’s poetic, intense, and melodramatic, and James Joyce for his lofty, superfluous writing style.

Here’s a paragraph from Joyce:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.

And here’s one from Hemingway:

Bill had gone into the bar. He was standing talking with Brett, who was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed. She had no stockings on.

Style is best observed and developed through a portfolio of writing. As you write more and form an identity as a writer, the bits of style in your writing will form constellations.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Word Choice in Writing: The Importance of Verbs

Before we offer some word choice exercises to expand your writing horizons, we first want to mention the importance of verbs. Verbs, as you may recall, are the “action” of the sentence—they describe what the subject of the sentence actually does. Unless you are intentionally breaking grammar rules, all sentences must have a verb, otherwise they don’t communicate much to the reader.

Because verbs are the most important part of the sentence, they are something you must focus on when expanding the reaches of your word choice. Verbs are the most widely variegated units of language; the more “things” you can do in the world, the more verbs there are to describe them, making them great vehicles for both figurative language and vivid description.

Consider the following three sentences:

- The road runs through the hills.

- The road curves through the hills.

- The road meanders through the hills.

Which sentence is the most descriptive? Though each of them has the same subject, object, and number of words, the third sentence creates the clearest image. The reader can visualize a road curving left and right through a hilly terrain, whereas the first two sentences require more thought to see clearly.

Finally, this resource on verb usage does a great job at highlighting how to invent and expand your verb choice.

Word Choice in Writing: Economy and Concision

Strong word choice means that every word you write packs a punch. As we’ve seen with adverbs above, you may find that your writing becomes more concise and economical—delivering more impact per word. Above all, you may find that you omit needless words.

Omit needless words is, in fact, a general order issued by Strunk and White in their classic Elements of Style. As they explain it:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

It’s worth repeating that this doesn’t mean your writing becomes clipped or terse, but simply that “every word tell.” As our word choice improves—as we omit needless words and express ourselves more precisely—our writing becomes richer, whether we write in long or short sentences.

As an example, here’s the opening sentence of a random personal essay from a high school test preparation handbook:

The world is filled with a numerous amount of student athletes that could somewhere down the road have a bright future.

Most words in this sentence are needless. It could be edited down to:

Many student athletes could have a bright future.

Now let’s take some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Can you remove a single word without sacrificing an enormous richness of meaning?

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In strong writing, every single word is chosen for maximum impact. This is the true meaning of concise or economical writing.

5 Word Choice Exercises to Sharpen Your Writing

With our word choice definition in mind, as well as our discussions of verb use and concision, let’s explore the following exercises to put theory into practice. As you play around with words in the following word choice exercises, be sure to consider meaning, specificity, style, and (if applicable) audience.

1. Build Moods With Word Choice

Writers fine-tune their words because the right vocabulary will build lush, emotive worlds. As you expand your word choice and consider the weight of each word, focus on targeting precise emotions in your descriptions and figurative language.

This kind of point is best illustrated through word choice examples. An example of magnificent language is the poem “In Defense of Small Towns” by Oliver de la Paz. The poem’s ambivalent feelings toward small hometowns presents itself through the mood of the writing.

The poem is filled with tense descriptions, like “animal deaths and toughened hay” and “breeches speared with oil and diesel,” which present the small town as stoic and masculine. This, reinforced by the terse stanzas and the rare “chances for forgiveness,” offers us a bleak view of the town; yet it’s still a town where everything is important, from “the outline of every leaf” to the weightless flight of cattail seeds.

The writing’s terse, heavy mood exists because of the poem’s juxtaposition of masculine and feminine words. The challenge of building a mood produces this poem’s gravity and sincerity.

Try to write a poem, or even a sentence, that evokes a particular mood through words that bring that word to mind. Here’s an example:

- What mood do you want to evoke? flighty

- What words feel like they evoke that mood? not sure, whatever, maybe, perhaps, tomorrow, sometimes, sigh

- Try it in a sentence: “Maybe tomorrow we could see about looking at the lab results.” She sighed. “Perhaps.”

2. Invent New Words and Terms

A common question writers ask is, What is one way to revise for word choice? One trick to try is to make up new language in your revisions.

If you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

In the same way that unusual verbs highlight the action and style of your story, inventing words that don’t exist can also create powerful diction. Of course, your writing shouldn’t overflow with made-up words and pretentious portmanteaus, but if you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

A great example of an invented word is the phrase “wine-dark sea.” Understanding this invention requires a bit of history; in short, Homer describes the sea as “οἶνοψ πόντος”, or “wine-faced.” “Wine-dark,” then, is a poetic translation, a kind of kenning for the sea’s mystery.

Why “wine-dark” specifically? Perhaps because, like the sea, wine changes us; maybe the eyes of the sea are dark, as eyes often darken with wine; perhaps the sea is like a face, an inversion, a reflection of the self. In its endlessness, we see what we normally cannot.

Thus, “wine-dark” is a poetic combination of words that leads to intensive literary analysis. For a less historical example, I’m currently working on my poetry thesis, with pop culture monsters being the central theme of the poems. In one poem, I describe love as being “frankensteined.” By using this monstrous made-up verb in place of “stitched,” the poem’s attitude toward love is much clearer.

Try inventing a word or phrase whose meaning will be as clear to the reader as “wine-dark sea.” Here’s an example:

- What do you want to describe? feeling sorry for yourself because you’ve been stressed out for a long time

- What are some words that this feeling brings up? self-pity, sympathy, sadness, stress, compassion, busyness, love, anxiety, pity party, feeling sorry for yourself

- What are some fun ways to combine these words? sadxiety, stresslove

- Try it in a sentence: As all-nighter wore on, my anxiety softened into sadxiety: still edgy, but soft in the middle.

3. Only Use Words of Certain Etymologies

One of the reasons that the English language is so large and inconsistent is that it borrows words from every language. When you dig back into the history of loanwords, the English language is incredibly interesting!

(For example, many of our legal terms, such as judge, jury, and plaintiff, come from French. When the Normans [old French-speakers from Northern France] conquered England, their language became the language of power and nobility, so we retained many of our legal terms from when the French ruled the British Isles.)

Nerdy linguistics aside, etymologies also make for a fun word choice exercise. Try forcing yourself to write a poem or a story only using words of certain etymologies and avoiding others. For example, if you’re only allowed to use nouns and verbs that we borrowed from the French, then you can’t use Anglo-Saxon nouns like “cow,” “swine,” or “chicken,” but you can use French loanwords like “beef,” “pork,” and “poultry.”

Experiment with word etymologies and see how they affect the mood of your writing. You might find this to be an impactful facet of your word choice. You can Google “__ etymology” for any word to see its origin, and “__ synonym” to see synonyms.

Try writing a sentence only with roots from a single origin. (You can ignore common words like “the,” “a,” “of,” and so on.)

- What do you want to write? The apple rolled off the table.

- Try a first etymology: German: The apple wobbled off the bench.

- Try a second: Latin: The russet fruit rolled off the table.

4. Write in E-Prime

E-Prime Writing describes a writing style where you only write using the active voice. By eschewing all forms of the verb “to be”—using words such as “is,” “am,” “are,” “was,” and other “being” verbs—your writing should feel more clear, active, and precise!

E-Prime not only removes the passive voice (“The bottle was picked up by James”), but it gets at the reality that many sentences using to be are weakly constructed, even if they’re technically in the active voice.

Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

Try writing a paragraph in E-Prime:

- What do you want to write? Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

- Converted to E-Prime: Of course, E-Prime writing won’t best suit every project. The above paragraph uses E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would carry challenges. E-Prime writing endeavors to make all of your subjects active, and your verbs more impactful. While this word choice exercise can bring enjoyment and create memorable language, you probably can’t sustain it over a long writing project.

5. Write Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry, also known as Found Poetry, is a visual creative writing project. You take a page from a published source and create a poem by blacking out other words until your circled words create a new poem. The challenge is that you’re limited to the words on a page, so you need a charged use of both space and language to make a compelling blackout poem.

Blackout poetry bottoms out our list of great word choice exercises because it forces you to consider the elements of word choice. With blackout poems, certain words might be read connotatively rather than denotatively, or you might change the meaning and specificity of a word by using other words nearby. Language is at its most fluid and interpretive in blackout poems!

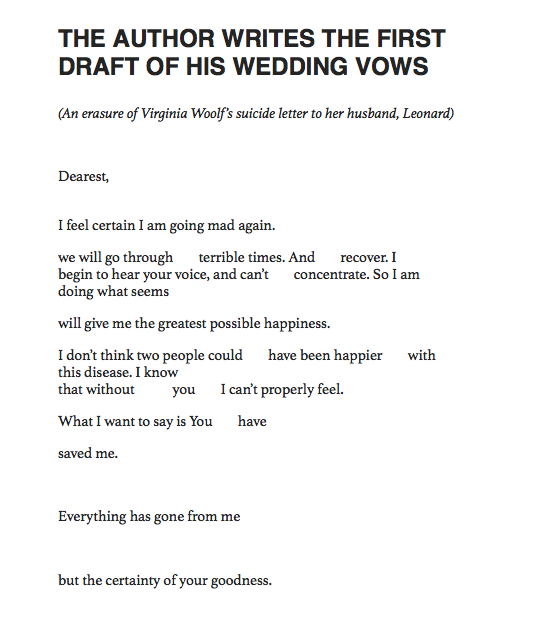

For a great word choice example using blackout poetry, read “The Author Writes the First Draft of His Wedding Vows” by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib. Here it is visually:

Source: https://decreation.tumblr.com/post/620222983530807296/from-the-crown-aint-worth-much-by-hanif

Pick a favorite poem of your own and make something completely new out of it using blackout poetry.

How to Expand Your Vocabulary

Vocabulary is a last topic in word choice. The more words in your arsenal, the better. Great word choice doesn’t rely on a large vocabulary, but knowing more words will always help! So, how do you expand your vocabulary?

The simplest way to expand your vocabulary is by reading.

The simplest answer, and the one you’ll hear the most often, is by reading. The more literature you consume, the more examples you’ll see of great words using the four elements of word choice.

Of course, there are also some great programs for expanding your vocabulary as well. If you’re looking to use words like “lachrymose” in a sentence, take a look at the following vocab builders:

- Dictionary.com’s Word-of-the-Day

- Vocabulary.com Games

- Merriam Webster’s Vocab Quizzes

Improve Your Word Choice With Writers.com’s Online Writing Courses

Looking for more writing exercises? Need more help choosing the right words? The instructors at Writers.com are masters of the craft. Take a look at our upcoming course offerings and join our community!

I’d (he’d, etc) = I would

(he would, etc) like (to do sth) мне

(ему

и

т.

п.)

хотелось

бы

(что-н

сделать)

show sb around (about) (a

factory, a place, a town, etc)

показать

кому-н

завод

(город

и

т.

п.)

take

sb

aside

отвести, отозвать кого-н в сторону

be

delighted

(with

sb/sth)

восторгаться, восхищаться (кем-н/чем-н)

now

and

again

= now

and

then

то и дело, время от времени

make

notes

делать заметки

work

sth

out

1. решить, разрешить что-н; 2. разработать

что-н

that‘s

it

(вот и) всё; вот именно

Exercises comprehension

Ex 1 Answer the

following questions.

1.

When did Chaplin first meet Professor Einstein? 2. What was Professor

Einstein doing in California? 3. How did Chaplin learn that Professor

Einstein would like to meet him? 4. Why was he so thrilled by the

invitation? 5. What made Chaplin believe that Mrs. Einstein enjoyed

being the wife of the great man? 6. What happened while the Professor

was being shown around the studio? 7. Why were so few people invited

to dinner at Chaplin’s house? 8. What story did Mrs. Einstein tell

Chaplin at dinner? 9. How did Mrs. Einstein immediately know that

something was troubling her husband when he came down to breakfast on

the morning the theory of relativity first came to his mind? 10. Why

did the Doctor only mention the fact that he had a marvelous idea?

11. Why couldn’t he tell his wife more about it? 12. Why didn’t

Einstein want anyone to disturb him while he was working out the

problem? 13. How long did it take the scientist to work it out? 14.

How much truth was there about the discovery in Mrs. Einstein’s

story?

Ex 2 Look through the

text once again, and:

1.

See if you can prove that Ch. Chaplin is telling the story (i)

seriously; (ii) humorously. 2. Explain why Ch. Chaplin chose to tell

the story of the world’s greatest discovery in physics as related by

Mrs Einstein. 3. Say what picture you get of (i) Mrs Einstein; (ii)

Professor Einstein; (iii) the narrator.

Ex 3 Find in the text

the English equivalents for the following phrases, and use them in

retelling and discussing the text.

впервые познакомиться

с кем-н; великий ученый; читать лекции;

с радостью принять приглашение;

встретиться на обеде; великий физик;

даже не пытаться скрывать что-н; показывать

кому-н студию; отвести кого-н в сторону;

быть в восторге; теория относительности;

прийти в голову; как обычно; почти не

притронуться к еде; почувствовать что-то

неладное; чудесная (великолепная) мысль;

подняться наверх в кабинет; совершать

моцион; наконец; выглядеть бледным и

усталым; держать в руке два листа бумаги;

положить на стол.

Key structures and word study

Ex 4 Give the four

forms of the following verbs.

meet,

say, speak, hide, show, take, think, drink, make, send, hold.

Ex

5 Make up five groups, each with three words that are associated in

meaning or area of usage.

|

assistant |

letter |

scientist |

piano |

professor |

|

telephone |

violin |

studio |

telegram |

camera |

|

physicist |

teacher |

flute |

film |

astronomer |

Ex 6 From the

following groups of words, pick out the word which, in your opinion,

is the most general in meaning.

(a) party, entertainment,

dinner party, affair^ gathering, ball, reception, luncheon, social.

(b) chat, talk, conversation,

discussion, debate, conference, dialogue, interview.

Ex 7 Complete the

following, choosing a suitable word from the list.

Example: a sheet

of paper

slice, box, cake (tablet),

bar, bottle (carton), suit, length, lump, pack, pair

1.

cards. 2. material. 3. matches. 4. gloves. 5. sugar. 6. cake. 7.

chocolate. 8. soap. 9. clothes. 10. milk.

Ex 8 Change the meaning

of the sentences to the opposite adding the prefix ‘dis-‘ to the

words in bold type and making other necessary changes. Translate the

sentences into Russian.

1.

She was pleased

with the arrangement. 2. He

appeared in our

town two years ago and at that time his

appearance made a

great noise. 3.

I don’t see how you could

believe her story.

4. We agree on

some questions. 5. I can’t say I

like the idea. 6.

This is what I call an

honest answer.

Ex 9 Rewrite the

sentences, using verbs instead of nouns and phrases in bold type.

Make other necessary changes.

(A)

1. At the gate the car

came to a stop. 2.

Nobody will hear you if you

speak in a whisper.

3. What’s the

trouble? 4.

I felt

a light touch on my

shoulder and turned around. 5. I hear he has published two stories in

big magazines this month. That’s a nice

start for a young

writer. 6. On what day do they plan their

return to town? 7.

His pictures have

been on show at the

National Gallery.

(B)

1. Who made the

discovery that

lightning is electricity? 2. Who will help you with the

preparations for

the conference? 3. Nobody wanted you to

make a quick decision.

4. Have you heard of his

refusal to take

part in the match yet? 5. The new bridge is the

pride of the young

engineer. 6. These books

are on sale in the

book shop at the corner. 7. We had

little choice in

the matter. 8. She always

makes her appearance

when she is least of all expected.

Ex 10 In the following

groups of sentences, explain the meaning of the words in bold type;

say which phrase is used literally and which has a figurative

meaning. Translate them into Russian.

1.

(i) I called at his office yesterday, but

found him out. (ii)

He was unable to

find out the

answer. 2. (i) The secretary

took out several

sheets of paper and prepared to take notes, (ii) He called every

Saturday night to

take the girl out

to dinner or, perhaps, to a dance. 3. (i) He

brought out his

stamp album and proudly showed his latest buy. (ii) The discussion

brought out all the

different ideas that we had on the matter. (iii) I’m sure that a

study of the problem will

bring out many

surprising things. 4. (i) Are you

coming out with me?

(ii) When did the book

come out? (iii) It

came out that she

knew the truth all the time. 5. (i) She smiled and

held out her hand

to me. (ii) My opponent was an expert chess-player and I didn’t

believe I could hold

out against him

much longer.

Ex 11 Translate the

following sentences into English, using a different phrasal verb in

each.

work out (2), sell out, think

out, hand out, help out, hear out

1.

План был хорошо

продуман.

2. Тетради были

розданы,

просмотрены и снова возвращены

преподавателю. 3. Она попросила меня

выслушать

ее. 4. Как всегда, он надеялся, что

кто-нибудь

выручит его.

5. Прошло несколько дней, прежде чем было

выработано

решение. 6. Пока еще трудно сказать,

сколько времени у него уйдет на то, чтобы

разработать

тему. 7.

Словарь

был

распродан

менее

чем

за

неделю.

Ех

12 Compare the meaning of the words in bold type with words of the

same root in Russian.

1.

There are unlimited

reserves of

energy in the

atoms of different

chemical elements.

2. Scientists think that only the

planet Earth has

oceans.

3. Without sea there is no life, no weather, no

atmosphere. The sea

makes our climate

neither very hot nor very cold. 4. Great

progress has been

made in mechanising

heavy work in

industry, building

and transport.

5. In building work, new

types of

excavators are

being used to

mechanise excavation

work. 6. In the oil industry

turbine methods are

being practised.

7. New types of

mechanical, optical

and electrical

control-regulating apparatuses

for automatising

production and for

scientific work have been

constructed. 8. The

radio was born in Russia. On May 7, 1895 at a meeting of the Russian

Physical and

Chemical Society in St Petersburg the first

radio-receiving set

in the world was

demonstrated by the

great Russian scientist A. S. Popov. 9. The world’s first cracking

of oil at high temperature was

experimented with

in Russia. The theory

of the cracking

process was worked

out by A. A. Letny, a Russian engineer,

in 1875. 10. The world’s first

airplane, built by

A. F. Mozhaisky, rose into the air in Russia in 1882. 11. The

monumental building

of the Mineralogical

Museum of the Academy of Science, which was founded in the time of

Peter I, has one of the world’s richest

collections of

minerals.

Ex 13 Fill in the

blanks with ‘hard’ or ‘hardly’.

1.

It — ever snows in this part of the country. 2. It’s a —

question. She’ll — know the answer. 3. The man spoke a very strange

kind of Russian. I could — understand him. 4. The work was too —

for Carrie. When she left the shop in the evening she was so tired

that she could — move. 5. What do you mean by saying that you have

— any money left? 6. The girl was so excited that she — knew what

she was saying. 7. The boy had had a — life. His parents had been

killed in the war when he was — eight.

Ex 14 Translate the

following sentences, using ‘keep’ or ‘hold’ according to the sense.

1.

Где он

держит

марки? 2. Ребенок упадет, если вы не будете

держать

его за руку. 3. Он всегда держит

комнату в чистоте. 4.

Держитесь

правой стороны! 5. Он все еще

держит

первое место по стрельбе? 6. Вы всегда

держите

свое слово? 7. Как вы можете

держать

все эти факты в голове? 8. Он

держал

сигарету в руке, но не курил. 9. Не

выпускайте детей на улицу,

держите

их дома. Сегодня

сильный

мороз.

10. Не

держите

продукты

долго

в

холодильнике.

Ех

15 Translate the following sentences, using ‘receive’, ‘accept’ or

‘take’ according to the sense.

1.

Его

приняли

очень тепло. 2. Новый проект молодого

архитектора был

принят

на конкурс. 3. Они еще не

приняли

никакого решения до первому вопросу.

4. Не думаю, что он

принял

ваши слова серьезно. 5. Недавно наш

институт

принимал

делегацию студентов из Латинской

Америки. 6. — Почему вы не хотите

принять

участие в экскурсии? — Я себя что-то

плохо чувствую. 7. Их не

приняли,

так как было уже поздно и рабочий день

закончился. 8. —Почему не

приняли

вашу Статью? — В ней есть ряд ошибок.

Мне надо их исправить. 9. Его приняли

как старого друга. 10. Они с готовностью

приняли

наш совет. 11. Благодарим за ваше

приглашение, но мы не можем

принять

его. Мы

уезжаем.

Ех

16 Paraphrase the following sentences according to the example.

Example:

After he drank

coffee, he went to the piano and started to play.

After drinking

coffee, he went to the piano and started to play.

1.

After he spent a month in the mountains, he was in good form again.

2. After they thought the matter over, they took a decision. 3. After

he had travelled all over the country, he sat down to write a book.

4. They came to an agreement after they had argued for some time. 5.

After he had arranged his affairs, he went on a holiday. 6. After the

family moved in, they started to make preparations for a

house-warming party.

Ex 17 Study the

following phrases and (a) recall the sentences in which they are used

in the text, (b) use them in sentences of your own.

invite

sb to

a place (party); meet

at a place (for

lunch); show sb around/about

a place; take sb

aside; have a chat

(talk, walk, etc)

with sb; at

dinner, come to

one’s mind; work sth

out; go (walk)

upstairs/downstairs;

return to

one’s work; hold (have) sth

in one’s hand.

Ex 18 Fill in the

blanks with prepositions or adverbs.

(A)

1. «I don’t see what’s wrong — my whispering a few words —

your ear?» «You mustn’t do a thing like that with other

people present.» 2. I don’t know yet what to do, but we shall

work something —, I am sure. 3. I wonder if you could meet me —

the self-service cafeteria — lunch — half an hour? I’d like to

have a chat — you. 4. There hardly passes a day without the boy

getting — some kind — trouble. 5. She invited us — her place

promising that there would be only her family — dinner. 6. I am not

surprised — all that he has so much trouble — his car; he hardly

knows a thing — cars and motors. 7. If you are afraid that you may

forget something, make a note — it. 8. He told us how everything

had happened, but still we felt that he was hiding something — us.

9. The telephone started ringing and she reached — it without

getting — — the sofa. 10. She was very proud — her son and

could hardly wait to see him returning home after an absence —

three years. 11. The party is to be held — the biggest hall — the

town; it is to be the kind — affair one remembers the rest — his

life. 12. I wonder why he hasn’t mentioned — you that —

first there was a lot of trouble — the new machine. 13. I really

don’t see how I can get you — — trouble. 14. Your love of

excitement is going to get you — trouble some day. 15. His picture

was accepted — the exhibition.

(B)

You may remember that I was invited — N. to lecture — the young

gentlemen of the University there. — the afternoon of that day I

was having a chat — one of the young men who some time before the

lecture had shown me — the place. Before the lecture he took me —

and said he had an uncle who had never laughed or smiled — the past

few years. And with tears — his eyes this young man said, «Oh,

if I could only see him laugh once more!»

I

was touched. I said I would do my best and work something —. I

would try to make him laugh or cry. «I have some jokes — the

lecture that will make him laugh and I’ve got some others that will

make him cry or kill him.»

He

brought his uncle and placed him — the hall full — people right —

front — me. I started — simple jokes, then I shot — him old

jokes. I threw — him all kinds — jokes that came — my mind, but

I never moved him once.

I

was surprised. I closed the lecture — last and sat — tired.

«What’s

the matter — that old man?» I asked the president. «He

never laughed or cried once.»

«Why, he never heard a

thing! The old man has been deaf — years.»

(After «How I was Sold in

Newark» by Mark Twain)

Ex

19 Fill in the blanks with a suitable word. Use the correct form.

Translate the sentences into Russian.

disturb

(2), accept, trouble n

(2), hide, hold v,

touch v

(2), reach v

(2), appear, discover (2), law, proud (2), hardly

1.

The — of gravitation which was — by the English physicist Isaac

Newton caused a revolution in science. 2. When the news that

Tutankhamen’s body had been found — the world, newspaper reporters

— in large numbers in Luxor. 3. Not a sound was heard. Nothing —

the quiet of the place. 4. When the mistake was — it was already

too late for anything. 5. The children were not to — the dog, not

before it was washed at least. 6. When she finished her story she

repeated once again she had nothing to — from us and if we chose to

disbelieve her, it was our own business. 7. The Professor said he

would be busy in his laboratory and did not want anyone to — him

there. 8. I could see the boy was having a bad time but he was too —

to ask for help. 9. The question was rather unexpected and she —

knew what to say. 10. The girl sitting opposite me in the compartment

was — an open book but I clearly saw that her thoughts were

somewhere else. 11. «Home at last!» we sang out happily

when we felt the plane — ground at the airport. 12. He readily

agreed to buy a few things for me. It would be no — at all, he

said. He would be shopping anyway. 13. The hour was getting late but

no decision had been — yet. 14. You cannot do anything about facts,

you can only— them. 15. As far as I can see, the only —with you

is that it always takes you years to make up your mind. 16. He was

extremely — that he had been chosen to open the conference.

Ex 20 Replace the

Russian words and phrases with suitable English equivalents in the

correct form. Retell the passage.

Michael

Faraday was born in London in 1791 to a poor family, and as a boy he

did not learn much.

In

1804, when he was thirteen, he got a job in a book-seller’s shop. He

lived among books, and he

(начал)

to read some of them. The boy could not read every book in the shop

because he was busy and did not have much time. So he began

(выбирать)

the books which he liked best. He soon

(обнаружил)

that his main interest was in

(науке),

and especially in electricity.

(Как

всякий

истинный

ученый)

Faraday wanted to make experiments, but he did not have enough money

to do so.

Faraday

heard of talks on science which were being given by one of the

greatest

(ученых)

of the time, Sir Humphry Davy. As he sat and listened to the great

man he

(делал

записи).

Faraday wanted to give his life to

(науке),

so he wrote a letter to Sir Humphry Davy and asked for his help.

Sir

Humphry

(пригласил)

Faraday to come to see him, and gave him some

(научную

работу)

to do. Faraday

(был

в

восторге).

His work at

first was only to wash and

(готовить)

all the things which Davy and his fellow-scientists were to use in

their experiments, but he

(проводил

много

времени

с

учеными)

and could listen to what they said, and he (мог

наблюдать

их

за

работой).

Sir

Humphry sometimes

(путешествовал)

in Europe, where he went to meet the great

(ученые)

of other countries, and one day he

(решил)

to make another

of these trips. He asked Faraday if he

(хотел

бы),

to come with him.

Faraday,

of course, was thrilled and

(с

радостью

принял

приглашение).

He had never been more than a few miles from London in his life.

Faraday

(получил

большое

удовольствие

от)

his time in Europe, but he was not really sorry at the end of the

journey because he was now able to

(продолжить

свою

собственную

работу)

and experiments in England.

He

was wondering whether a magnet could

(кaким-то образом)

be made to give an electric current. Faraday

(был

совершенно

уверен)

that a current

could be made, but he had very little time for experiments. His

outside

work

(занимала

все

его

время).

Не

could stop his outside work, of course, but if he did so, he would

lose most of the £ 1,200 a year which he

(получал).

Не

had to

(выбирать)

between

(наукой)

and money, and he

(выбрал

науку).

At

first he was quite unable to make an electric current with his

magnets. But

one

day

(ему в голову пришла великолепная мысль).

Не (провел) the

magnet

near

the

wire.

And then he got

what he wanted: an electric current in the wire. Of course, he still

had to

(разработать

идею).

After

(нескольких)

experiments

(этого

рода)

he made a machine. It was the beginning of all the great machines

that make electricity today. All

(современные)

turbines are made on the principles that

(были

разработаны)

by Faraday. His

(открытие)

was the beginning of the electrical age, which

(изменил)

the face of the earth.

(After «Who Did It First»

by G. C. Thornley)

Ex

21 Speak on the following topics, using the words and phrases

given below.

1.

Professor Einstein Takes a Trip to California

a

famous scientist; a great physicist; be famous for; theories of

relativity; make many important discoveries; make a revolution in

physics; be invited to some place.

2.

Chaplin Meets the Einsteins

a

telephone call; a surprise; receive an invitation to lunch; be

thrilled; be eager to meet sb; accept the invitation gladly; meet the

Professor, his wife; meet for lunch; be proud (of); enjoy being the

wife of the great man; be unable to hide one’s feelings.

3.

Chaplin Invites the Professor to his House

take

sb aside; whisper sth into sb’s ear; give sb an excellent idea; be

delighted with the idea; admire sb greatly; invite to dinner; make

the necessary arrangements (for); a small affair; have a nice, quiet

chat (talk).

4.

The Story of the Discovery as Told by Mrs. Einstein

come

down for breakfast; as usual; wear a dressing-gown; notice sth

unusual about sb; hardly touch a thing; be lost in thought;

immediately see that sth is wrong; be upset; wonder what is troubling

a person; ask what the matter is; be eager to learn sth; refuse to

say anything; except; have a wonderful (marvelous) idea; go up to

one’s study; not disturb sb in his work; spend all one’s time in the

study working hard; work sth out; rise early; walk a little for

exercise; make notes; remain in one’s room for days; at last; appear;

hold in one’s hand; have the whole theory on two sheets of paper.

Ex

22 Test

translation.

1. Открытия, которые

были сделаны столетия назад, продолжают

играть большую роль в современной науке.

2. В Сибири недавно были открыты

месторождения природного газа. 3. Когда

мы обнаружили, что сбились с пути, было

уже поздно. Нам пришлось развести костер

и заночевать в лесу. 4. Он давно интересуется

книгами о научных открытиях. Не

удивительно, что он знает не только

имена многих ученых, но и открытия,

которые они сделали. 5. Я так спешил, что

оставил все деньги дома..6. Почему бы не

пригласить их поехать вместе с нами в

отпуск? Ч уверен, что они с удовольствием

согласятся. 7. Теперь уже трудно вспомнить,

кому эта идея пришла в голову. 8. Боюсь,

что директор не сможет вас завтра

принять. Он весь день будет занят на

конференции. 9. Никто не удивился, когда

картину молодого художника приняли на

выставку. 10. Я получил приглашение на

вечер, но не смогу пойти. Я завтра уезжаю.

11. Институт может гордиться своей

баскетбольной командой. Она заняла

первое место. 12. Они разговаривали

шепотом, так как было поздно и в доме

все спали. 13. Он едва проронил слово за

весь вечер. Он был чем-то расстроен. 14.

Все были глубоко тронуты его рассказом.

Он говорил с чувством, и его слушали с

большим интересом. 15. Я очень расстроился,

когда услышал, что у него неприятности.

Ты случайно не знаешь, в чем там дело?

16. Этот ребенок ужасно избалован и всегда

доставляет много хлопот. 17. Когда они

наконец добрались до лагеря, они

чувствовали себя очень усталыми. 18. Мне

бы хотелось поговорить с ним по этому

вопросу сегодня. 19. Когда вы переходите

улицу, посмотрите сначала налево, а

дойдя до середины дороги, посмотрите

направо. 20. Надеюсь, что я вам не помешаю,

если я останусь здесь на несколько

минут. 21. Мне не хотелось беспокоить его

в такой поздний час, но у меня не было

иного выхода. Мне очень нужен был его

совет. 22. Его появление было для нас

неожиданным. 23. План научной работы уже

разработан и будет обсуждаться на

следующем заседании.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

a range of functions

a network of sth.

an approach to sth

to create/to establish a bias

to exhibit -«-

to justify -«-

to outdo electoral promises

it cannot but take account of sth

horse trading

круг обязанностей

сеть ч-л

подход к чему-либо

сформировать предпочтение,

предубеждение

проявлять/отдавать предпочтение

ч-л

оправдывать предпочтения

перевыполнить предвыборные

обязательства

она не может

не учитывать/не принимать

во внимание

поиск компромисса

SKIM reading: Work in pairs:look through the text and bring out the to pical sentences conveying the main ideas of the text.

TEXT 2: PARTY SYSTEMS

Political parties are important not only because of the range of functions they carry out, but also because the complex interrelationships between and among parties are crucial in structuring how political systems work in practice. This network of relationships is called a party system. The most familiar way of distinguishing

dot ween different types of party system is by reference to the number nl parties competing for power. Although such a typology is commonly used, party systems cannot simply be reduced to a ‘numbers game’.

As important as the number of parties competing for power is their idative size, as reflected in their electoral and legislative strength. What is vital is to establish the ‘relevance’ of parties in relation to the [urination of governments, and in particular whether their size gives ilicm the prospect of winning, or at least sharing, government power. lhis approach is often reflected in the distinction made between major’, or government-orientated, parties and more peripheral, ‘minor’ ones (although neither category can be defined with mathematical accuracy).

A third consideration is how these ‘relevant’ parties relate to one.mother. Is the party system characterised by cooperation and lonsensus, by conflict and polarisation? This is closely linked to the ideological complexion of the party system and the traditions and history of the parties that compose it.

The mere presence of parties does not, however, guarantee the existence of a party system. The pattern of relationships amongst parties only constitutes a system if it is characterised by stability and a Ji-gree of orderliness. Where neither stability nor order exists, a party system may be in the process of emerging, or a transition from one ivpc of party system to another may be occurring.

One-party systems

Strictly speaking, the term one-party system is contradictory since system’ implies interaction amongst a number of entities. The term is nevertheless helpful in distinguishing between political systems in which a single party enjoys a monopoly of power through the fulusion of all other parties (by political or constitutional means).iiui ones characterised by a competitive struggle amongst a number of parties. Because monopolistic parties effectively function as permanent governments, with no mechanism (short of a coup or ii’volmion) through which they can be removed from power, they invariably develop an entrenched relationship with the state machine. Mns allows such states to be classified as ‘one-party states’, their machinery being seen as a fused ‘party-state’ apparatus.

two-party systems

A two-party system is duopolistic in that it is dominated by two major’ parties that have a roughly equal prospect of winning

government power. In its classical form, a two-party system can be identified by three criteria:

• Although a number of ‘minor’ parties may exist, only two parties enjoy sufficient electoral and legislative strength to have a realistic prospect of winning government power.

• The larger party is able to rule alone (usually on the basis of a legislative majority); the other provides the opposition.

• Power alternates between these parties; both are ‘electable’, the opposition serving as a ‘government in the wings’.

Two-party politics was once portrayed as the surest way of

reconciling responsiveness with order, representative government with

effective government. Its key advantage is that it makes possible a

system of party government, supposedly characterised by stability,

choice and accountability. The two major parties are able to offer the

electorate a straightforward choice between rival programmes and

alternative governments. Voters can support a party knowing that, if it

wins the election, it will have the capacity to carry out its manifesto

promises without having to negotiate or compromise with coalition

partners, Two-partyism, moreover, creates a bias in favour of

moderation, as the two contenders for power have to battle for|

‘floating’ votes in the centre ground. ;

However two-party politics and party government have not beetf so well regarded since the 1970s. Instead of guaranteeing moderation;1 two-party systems such as the UK’s, have displayed a periodic tendency towards adversary politics. This is reflected in ideological polarisation and an emphasis on conflict and argument rather thart consensus and compromise.

A further problem with the two-party system is that two evenly’ matched parties are encouraged to compete for votes by outdoing each other’s electoral promises, perhaps causing spiralling publi* spending and fuelling inflation. A final weakness of two-party syste: is the obvious restrictions they impose in terms of electoral an ideological choice. While a choice between just two programmes » government was perhaps sufficient in an era of partisan alignment a class solidarity, it has become quite inadequate in a period of grea individualism and social diversity.

Dominant-party systems

Dominant-party systems should not be confused with one-part systems, although they may at times exhibit similar characteristics, dominant-party system is competitive in the sense that a number parties compete for power in regular and popular elections, but if

dominated by a single major party that consequently enjoys prolonged periods in power.

The most prominent feature of a dominant-party system is the tendency for the political focus to shift from competition between parties to factional conflict within the dominant party itself. Although Hie resulting infighting may be seen as a means of guaranteeing argument and debate in a system in which small parties are usually marginalised, factionalism tends to revolve more around personal differences than it does around policy or ideological divisions.

Whereas other competitive party systems have their supporters, or.11 least apologists, few are prepared to come to the defence of the dominant-party system. Apart from a tendency towards stability and predictability, dominant-partyism is usually seen as a regrettable and unhealthy phenomenon. In the first place, it tends to erode the important constitutional distinction between the state and the party in power. When governments cease to come and go, an insidious process of politicisation takes place through which state officials and institutions adjust to the ideological and political priorities of the dominant party.

Secondly, an extended period in power can engender complacency, arrogance and even corruption in the dominant party.

Thirdly, a dominant-party system is characterised by weak and ineffective opposition. Criticism and protest can more easily be snored if they stem from parties that are no longer regarded as yniuine rivals for power. Finally, the existence of a ‘permanent’ party ot government may corrode the democratic spirit by encouraging the.-K-ctorate to fear change and to stick with the ‘natural’ party of government. A genuinely democratic political culture arguably squires a general public that has a healthy distrust of all parties, and most importantly, a willingness to remove governments that have t.uled.

Multiparty systems

A multiparty system is characterised by competition amongst more tkm two parties reducing the chances of single-party government and UK leasing the likelihood of coalitions. However, it is difficult to ditiiie multiparty systems in terms of the number of major parties, as.’.uh systems sometimes operate through coalitions including smaller j.uiies that are specifically designed to exclude larger parties from I’liwrntnent.

The strength of the multiparty systems is that they create internal. links and balances within government and exhibit a bias in favour of Muie. conciliation and compromise. The process of coalition

formation and the dynamics of coalition maintenance ensure a broad responsiveness that cannot but take account of competing views and contending interests.

The principle criticisms of multiparty systems relate to the pitfalls and difficulties of coalition formation. The post-election negotiations and horse trading that take place when no single party is strong enough to govern alone can take weeks, or (as in Israel and Italy) sometimes months, to complete. More seriously, coalition governments may be fractured and unstable, paying greater attention to squabbles amongst coalition partners than to the tasks of government.

A final problem is that the tendency towards moderation and compromise may mean that multiparty systems are so dominated by the political centre that they are unable to offer clear ideological alternatives. Coalition politics tends, naturally, to be characterised by negotiation and conciliation, a search for common ground, rather than by conviction and the politics of principle. This process can be criticised as being implicitly corrupt, in that parties are encouraged to abandon policies and principles in their quest for power.

♦ Discuss/check your considerations with the rest of the

class.

|

Функция спроса населения на данный товар Функция спроса населения на данный товар: Qd=7-Р. Функция предложения: Qs= -5+2Р,где… |

Аальтернативная стоимость. Кривая производственных возможностей В экономике Буридании есть 100 ед. труда с производительностью 4 м ткани или 2 кг мяса… |

Вычисление основной дактилоскопической формулы Вычислением основной дактоформулы обычно занимается следователь. Для этого все десять пальцев разбиваются на пять пар… |

Расчетные и графические задания Равновесный объем — это объем, определяемый равенством спроса и предложения… |

|

Условия приобретения статуса индивидуального предпринимателя. В соответствии с п. 1 ст. 23 ГК РФ гражданин вправе заниматься предпринимательской деятельностью без образования юридического лица с момента государственной регистрации в качестве индивидуального предпринимателя. Каковы же условия такой регистрации и… Седалищно-прямокишечная ямка Седалищно-прямокишечная (анальная) ямка, fossa ischiorectalis (ischioanalis) – это парное углубление в области промежности, находящееся по бокам от конечного отдела прямой кишки и седалищных бугров, заполненное жировой клетчаткой, сосудами, нервами и… Основные структурные физиотерапевтические подразделения Физиотерапевтическое подразделение является одним из структурных подразделений лечебно-профилактического учреждения, которое предназначено для оказания физиотерапевтической помощи… |