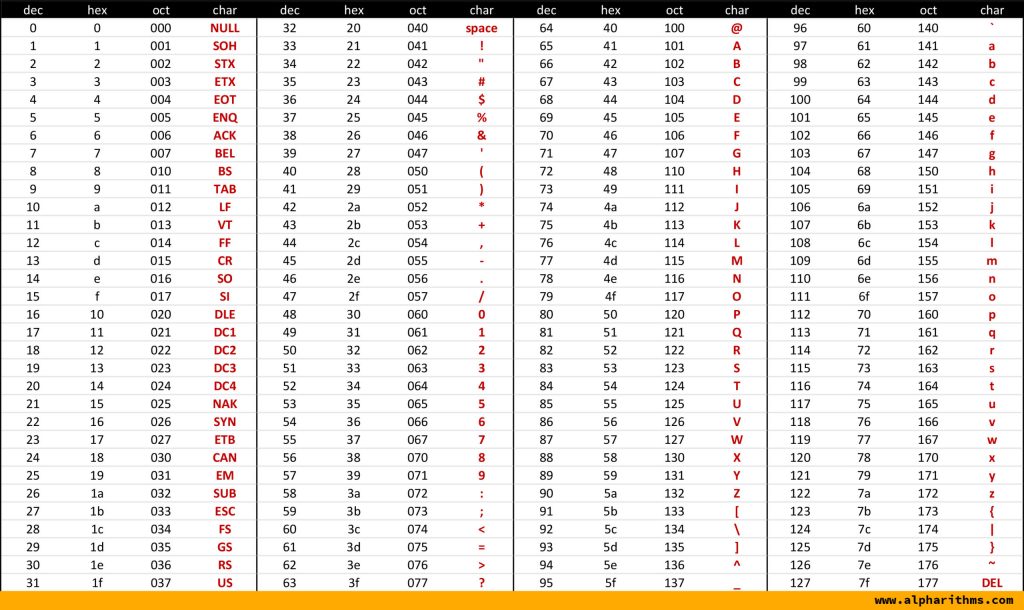

Список из 256 символов и их коды в ASCII.

1

Управляющие символы

| DEC | OCT | HEX | BIN | Символ | Escape послед. | HTML код | Описание |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 000 | 0x00 | 00000000 | NUL | � | Нулевой байт | |

| 1 | 001 | 0x01 | 00000001 | SOH |  | Начало заголовка | |

| 2 | 002 | 0x02 | 00000010 | STX |  | Начало текста | |

| 3 | 003 | 0x03 | 00000011 | ETX |  | Конец «текста» | |

| 4 | 004 | 0x04 | 00000100 | EOT |  | конец передачи | |

| 5 | 005 | 0x05 | 00000101 | ENQ |  | «Прошу подтверждения!» | |

| 6 | 006 | 0x06 | 00000110 | ACK |  | «Подтверждаю!» | |

| 7 | 007 | 0x07 | 00000111 | BEL | a |  | Звуковой сигнал – звонок |

| 8 | 010 | 0x08 | 00001000 | BS | b |  | Возврат на один символ (BACKSPACE) |

| 9 | 011 | 0x09 | 00001001 | TAB | t | Табуляция | |

| 10 | 012 | 0x0A | 00001010 | LF | n | Перевод строки | |

| 11 | 013 | 0x0B | 00001011 | VT | v |  | Вертикальная табуляция |

| 12 | 014 | 0x0C | 00001100 | FF | f |  | Прогон страницы, новая страница |

| 13 | 015 | 0x0D | 00001101 | CR | r | Возврат каретки | |

| 14 | 016 | 0x0E | 00001110 | SO |  | Переключиться на другую ленту (кодировку) | |

| 15 | 017 | 0x0F | 00001111 | SI |  | Переключиться на исходную ленту (кодировку) | |

| 16 | 020 | 0x10 | 00010000 | DLE |  | Экранирование канала данных | |

| 17 | 021 | 0x11 | 00010001 | DC1 |  | 1-й символ управления устройством | |

| 18 | 022 | 0x12 | 00010010 | DC2 |  | 2-й символ управления устройством | |

| 19 | 023 | 0x13 | 00010011 | DC3 |  | 3-й символ управления устройством | |

| 20 | 024 | 0x14 | 00010100 | DC4 |  | 4-й символ управления устройством | |

| 21 | 025 | 0x15 | 00010101 | NAK |  | «Не подтверждаю!» | |

| 22 | 026 | 0x16 | 00010110 | SYN |  | Символ для синхронизации | |

| 23 | 027 | 0x17 | 00010111 | ETB |  | Конец текстового блока | |

| 24 | 030 | 0x18 | 00011000 | CAN |  | Отмена | |

| 25 | 031 | 0x19 | 00011001 | EM |  | Конец носителя | |

| 26 | 032 | 0x1A | 00011010 | SUB |  | Подставить | |

| 27 | 033 | 0x1B | 00011011 | ESC | e |  | Escape (Расширение) |

| 28 | 034 | 0x1C | 00011100 | FS |  | Разделитель файлов | |

| 29 | 035 | 0x1D | 00011101 | GS |  | Разделитель групп | |

| 30 | 036 | 0x1E | 00011110 | RS |  | Разделитель записей | |

| 31 | 037 | 0x1F | 00011111 | US |  | Разделитель юнитов | |

| 127 | 177 | 0x7F | 01111111 | Delete | | Символ для удаления (на перфолентах) |

2

Печатные символы

| DEC | OCT | HEX | BIN | Символ | HTML код | Мнемоника |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32 | 040 | 0x20 | 00100000 | Пробел | ||

| 33 | 041 | 0x21 | 00100001 | ! | ! | |

| 34 | 042 | 0x22 | 00100010 | « | " | " |

| 35 | 043 | 0x23 | 00100011 | # | # | |

| 36 | 044 | 0x24 | 00100100 | $ | $ | |

| 37 | 045 | 0x25 | 00100101 | % | % | |

| 38 | 046 | 0x26 | 00100110 | & | & | & |

| 39 | 047 | 0x27 | 00100111 | ‘ | ' | ' |

| 40 | 050 | 0x28 | 00101000 | ( | ( | |

| 41 | 051 | 0x29 | 00101001 | ) | ) | |

| 42 | 052 | 0x2A | 00101010 | * | * | |

| 43 | 053 | 0x2B | 00101011 | + | + | |

| 44 | 054 | 0x2C | 00101100 | , | , | |

| 45 | 055 | 0x2D | 00101101 | — | - | |

| 46 | 056 | 0x2E | 00101110 | . | . | |

| 47 | 057 | 0x2F | 00101111 | / | / | |

| 48 | 060 | 0x30 | 00110000 | 0 | 0 | |

| 49 | 061 | 0x31 | 00110001 | 1 | 1 | |

| 50 | 062 | 0x32 | 00110010 | 2 | 2 | |

| 51 | 063 | 0x33 | 00110011 | 3 | 3 | |

| 52 | 064 | 0x34 | 00110100 | 4 | 4 | |

| 53 | 065 | 0x35 | 00110101 | 5 | 5 | |

| 54 | 066 | 0x36 | 00110110 | 6 | 6 | |

| 55 | 067 | 0x37 | 00110111 | 7 | 7 | |

| 56 | 070 | 0x38 | 00111000 | 8 | 8 | |

| 57 | 071 | 0x39 | 00111001 | 9 | 9 | |

| 58 | 072 | 0x3A | 00111010 | : | : | |

| 59 | 073 | 0x3B | 00111011 | ; | ; | |

| 60 | 074 | 0x3C | 00111100 | < | < | < |

| 61 | 075 | 0x3D | 00111101 | = | = | |

| 62 | 076 | 0x3E | 00111110 | > | > | > |

| 63 | 077 | 0x3F | 00111111 | ? | ? | |

| 64 | 100 | 0x40 | 01000000 | @ | @ | |

| 65 | 101 | 0x41 | 01000001 | A | A | |

| 66 | 102 | 0x42 | 01000010 | B | B | |

| 67 | 103 | 0x43 | 01000011 | C | C | |

| 68 | 104 | 0x44 | 01000100 | D | D | |

| 69 | 105 | 0x45 | 01000101 | E | E | |

| 70 | 106 | 0x46 | 01000110 | F | F | |

| 71 | 107 | 0x47 | 01000111 | G | G | |

| 72 | 110 | 0x48 | 01001000 | H | H | |

| 73 | 111 | 0x49 | 01001001 | I | I | |

| 74 | 112 | 0x4A | 01001010 | J | J | |

| 75 | 113 | 0x4B | 01001011 | K | K | |

| 76 | 114 | 0x4C | 01001100 | L | L | |

| 77 | 115 | 0x4D | 01001101 | M | M | |

| 78 | 116 | 0x4E | 01001110 | N | N | |

| 79 | 117 | 0x4F | 01001111 | O | O | |

| 80 | 120 | 0x50 | 01010000 | P | P | |

| 81 | 121 | 0x51 | 01010001 | Q | Q | |

| 82 | 122 | 0x52 | 01010010 | R | R | |

| 83 | 123 | 0x53 | 01010011 | S | S | |

| 84 | 124 | 0x54 | 01010100 | T | T | |

| 85 | 125 | 0x55 | 01010101 | U | U | |

| 86 | 126 | 0x56 | 01010110 | V | V | |

| 87 | 127 | 0x57 | 01010111 | W | W | |

| 88 | 130 | 0x58 | 01011000 | X | X | |

| 89 | 131 | 0x59 | 01011001 | Y | Y | |

| 90 | 132 | 0x5A | 01011010 | Z | Z | |

| 91 | 133 | 0x5B | 01011011 | [ | [ | |

| 92 | 134 | 0x5C | 01011100 | \ | ||

| 93 | 135 | 0x5D | 01011101 | ] | ] | |

| 94 | 136 | 0x5E | 01011110 | ^ | ^ | |

| 95 | 137 | 0x5F | 01011111 | _ | _ | |

| 96 | 140 | 0x60 | 01100000 | ` | ` | |

| 97 | 141 | 0x61 | 01100001 | a | a | |

| 98 | 142 | 0x62 | 01100010 | b | b | |

| 99 | 143 | 0x63 | 01100011 | c | c | |

| 100 | 144 | 0x64 | 01100100 | d | d | |

| 101 | 145 | 0x65 | 01100101 | e | e | |

| 102 | 146 | 0x66 | 01100110 | f | f | |

| 103 | 147 | 0x67 | 01100111 | g | g | |

| 104 | 150 | 0x68 | 01101000 | h | h | |

| 105 | 151 | 0x69 | 01101001 | i | i | |

| 106 | 152 | 0x6A | 01101010 | j | j | |

| 107 | 153 | 0x6B | 01101011 | k | k | |

| 108 | 154 | 0x6C | 01101100 | l | l | |

| 109 | 155 | 0x6D | 01101101 | m | m | |

| 110 | 156 | 0x6E | 01101110 | n | n | |

| 111 | 157 | 0x6F | 01101111 | o | o | |

| 112 | 160 | 0x70 | 01110000 | p | p | |

| 113 | 161 | 0x71 | 01110001 | q | q | |

| 114 | 162 | 0x72 | 01110010 | r | r | |

| 115 | 163 | 0x73 | 01110011 | s | s | |

| 116 | 164 | 0x74 | 01110100 | t | t | |

| 117 | 165 | 0x75 | 01110101 | u | u | |

| 118 | 166 | 0x76 | 01110110 | v | v | |

| 119 | 167 | 0x77 | 01110111 | w | w | |

| 120 | 170 | 0x78 | 01111000 | x | x | |

| 121 | 171 | 0x79 | 01111001 | y | y | |

| 122 | 172 | 0x7A | 01111010 | z | z | |

| 123 | 173 | 0x7B | 01111011 | { | { | |

| 124 | 174 | 0x7C | 01111100 | | | | | |

| 125 | 175 | 0x7D | 01111101 | } | } | |

| 126 | 176 | 0x7E | 01111110 | ~ | ~ |

3

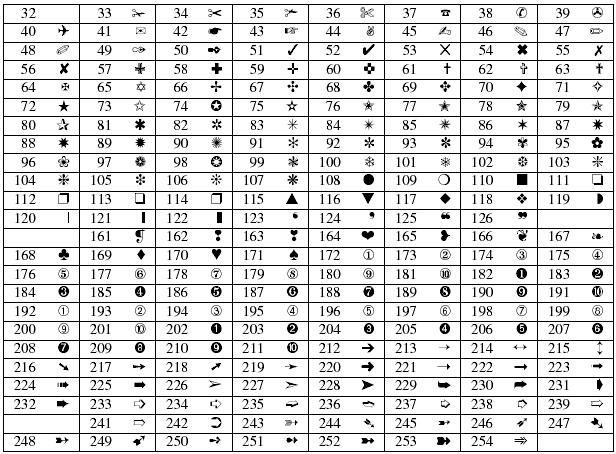

Расширенные символы ASCII Win-1251 кириллица

| DEC | OCT | HEX | BIN | Символ | HTML код | Мнемоника |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 128 | 200 | 0x80 | 10000000 | Ђ | € | |

| 129 | 201 | 0x81 | 10000001 | Ѓ | | |

| 130 | 202 | 0x82 | 10000010 | ‚ | ‚ | ‚ |

| 131 | 203 | 0x83 | 10000011 | ѓ | ƒ | |

| 132 | 204 | 0x84 | 10000100 | „ | „ | „ |

| 133 | 205 | 0x85 | 10000101 | … | … | … |

| 134 | 206 | 0x86 | 10000110 | † | † | † |

| 135 | 207 | 0x87 | 10000111 | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ |

| 136 | 210 | 0x88 | 10001000 | € | ˆ | € |

| 137 | 211 | 0x89 | 10001001 | ‰ | ‰ | ‰ |

| 138 | 212 | 0x8A | 10001010 | Љ | Š | |

| 139 | 213 | 0x8B | 10001011 | ‹ | ‹ | ‹ |

| 140 | 214 | 0x8C | 10001100 | Њ | Œ | |

| 141 | 215 | 0x8D | 10001101 | Ќ | | |

| 142 | 216 | 0x8E | 10001110 | Ћ | Ž | |

| 143 | 217 | 0x8F | 10001111 | Џ | | |

| 144 | 220 | 0x90 | 10010000 | Ђ | | |

| 145 | 221 | 0x91 | 10010001 | ‘ | ‘ | ‘ |

| 146 | 222 | 0x92 | 10010010 | ’ | ’ | ’ |

| 147 | 223 | 0x93 | 10010011 | “ | “ | “ |

| 148 | 224 | 0x94 | 10010100 | ” | ” | ” |

| 149 | 225 | 0x95 | 10010101 | • | • | • |

| 150 | 226 | 0x96 | 10010110 | – | – | – |

| 151 | 227 | 0x97 | 10010111 | — | — | — |

| 152 | 230 | 0x98 | 10011000 | Начало строки | ˜ | |

| 153 | 231 | 0x99 | 10011001 | ™ | ™ | ™ |

| 154 | 232 | 0x9A | 10011010 | љ | š | |

| 155 | 233 | 0x9B | 10011011 | › | › | › |

| 156 | 234 | 0x9C | 10011100 | њ | œ | |

| 157 | 235 | 0x9D | 10011101 | ќ | | |

| 158 | 236 | 0x9E | 10011110 | ћ | ž | |

| 159 | 237 | 0x9F | 10011111 | џ | Ÿ | |

| 160 | 240 | 0xA0 | 10100000 | Неразрывный пробел | | |

| 161 | 241 | 0xA1 | 10100001 | Ў | ¡ | |

| 162 | 242 | 0xA2 | 10100010 | ў | ¢ | |

| 163 | 243 | 0xA3 | 10100011 | Ј | £ | |

| 164 | 244 | 0xA4 | 10100100 | ¤ | ¤ | ¤ |

| 165 | 245 | 0xA5 | 10100101 | Ґ | ¥ | |

| 166 | 246 | 0xA6 | 10100110 | ¦ | ¦ | ¦ |

| 167 | 247 | 0xA7 | 10100111 | § | § | § |

| 168 | 250 | 0xA8 | 10101000 | Ё | ¨ | |

| 169 | 251 | 0xA9 | 10101001 | © | © | © |

| 170 | 252 | 0xAA | 10101010 | Є | ª | |

| 171 | 253 | 0xAB | 10101011 | « | « | « |

| 172 | 254 | 0xAC | 10101100 | ¬ | ¬ | ¬ |

| 173 | 255 | 0xAD | 10101101 | Мягкий перенос | | ­ |

| 174 | 256 | 0xAE | 10101110 | ® | ® | ® |

| 175 | 257 | 0xAF | 10101111 | Ї | ¯ | |

| 176 | 260 | 0xB0 | 10110000 | ° | ° | ° |

| 177 | 261 | 0xB1 | 10110001 | ± | ± | ± |

| 178 | 262 | 0xB2 | 10110010 | І | ² | |

| 179 | 263 | 0xB3 | 10110011 | і | ³ | |

| 180 | 264 | 0xB4 | 10110100 | ґ | ´ | |

| 181 | 265 | 0xB5 | 10110101 | µ | µ | µ |

| 182 | 266 | 0xB6 | 10110110 | ¶ | ¶ | ¶ |

| 183 | 267 | 0xB7 | 10110111 | · | · | · |

| 184 | 270 | 0xB8 | 10111000 | ё | ¸ | |

| 185 | 271 | 0xB9 | 10111001 | № | ¹ | |

| 186 | 272 | 0xBA | 10111010 | є | º | |

| 187 | 273 | 0xBB | 10111011 | » | » | » |

| 188 | 274 | 0xBC | 10111100 | ј | ¼ | |

| 189 | 275 | 0xBD | 10111101 | Ѕ | ½ | |

| 190 | 276 | 0xBE | 10111110 | ѕ | ¾ | |

| 191 | 277 | 0xBF | 10111111 | ї | ¿ | |

| 192 | 300 | 0xC0 | 11000000 | А | À | |

| 193 | 301 | 0xC1 | 11000001 | Б | Á | |

| 194 | 302 | 0xC2 | 11000010 | В | Â | |

| 195 | 303 | 0xC3 | 11000011 | Г | Ã | |

| 196 | 304 | 0xC4 | 11000100 | Д | Ä | |

| 197 | 305 | 0xC5 | 11000101 | Е | Å | |

| 198 | 306 | 0xC6 | 11000110 | Ж | Æ | |

| 199 | 307 | 0xC7 | 11000111 | З | Ç | |

| 200 | 310 | 0xC8 | 11001000 | И | È | |

| 201 | 311 | 0xC9 | 11001001 | Й | É | |

| 202 | 312 | 0xCA | 11001010 | К | Ê | |

| 203 | 313 | 0xCB | 11001011 | Л | Ë | |

| 204 | 314 | 0xCC | 11001100 | М | Ì | |

| 205 | 315 | 0xCD | 11001101 | Н | Í | |

| 206 | 316 | 0xCE | 11001110 | О | Î | |

| 207 | 317 | 0xCF | 11001111 | П | Ï | |

| 208 | 320 | 0xD0 | 11010000 | Р | Ð | |

| 209 | 321 | 0xD1 | 11010001 | С | Ñ | |

| 210 | 322 | 0xD2 | 11010010 | Т | Ò | |

| 211 | 323 | 0xD3 | 11010011 | У | Ó | |

| 212 | 324 | 0xD4 | 11010100 | Ф | Ô | |

| 213 | 325 | 0xD5 | 11010101 | Х | Õ | |

| 214 | 326 | 0xD6 | 11010110 | Ц | Ö | |

| 215 | 327 | 0xD7 | 11010111 | Ч | × | |

| 216 | 330 | 0xD8 | 11011000 | Ш | Ø | |

| 217 | 331 | 0xD9 | 11011001 | Щ | Ù | |

| 218 | 332 | 0xDA | 11011010 | Ъ | Ú | |

| 219 | 333 | 0xDB | 11011011 | Ы | Û | |

| 220 | 334 | 0xDC | 11011100 | Ь | Ü | |

| 221 | 335 | 0xDD | 11011101 | Э | Ý | |

| 222 | 336 | 0xDE | 11011110 | Ю | Þ | |

| 223 | 337 | 0xDF | 11011111 | Я | ß | |

| 224 | 340 | 0xE0 | 11100000 | а | à | |

| 225 | 341 | 0xE1 | 11100001 | б | á | |

| 226 | 342 | 0xE2 | 11100010 | в | â | |

| 227 | 343 | 0xE3 | 11100011 | г | ã | |

| 228 | 344 | 0xE4 | 11100100 | д | ä | |

| 229 | 345 | 0xE5 | 11100101 | е | å | |

| 230 | 346 | 0xE6 | 11100110 | ж | æ | |

| 231 | 347 | 0xE7 | 11100111 | з | ç | |

| 232 | 350 | 0xE8 | 11101000 | и | è | |

| 233 | 351 | 0xE9 | 11101001 | й | é | |

| 234 | 352 | 0xEA | 11101010 | к | ê | |

| 235 | 353 | 0xEB | 11101011 | л | ë | |

| 236 | 354 | 0xEC | 11101100 | м | ì | |

| 237 | 355 | 0xED | 11101101 | н | í | |

| 238 | 356 | 0xEE | 11101110 | о | î | |

| 239 | 357 | 0xEF | 11101111 | п | ï | |

| 240 | 360 | 0xF0 | 11110000 | р | ð | |

| 241 | 361 | 0xF1 | 11110001 | с | ñ | |

| 242 | 362 | 0xF2 | 11110010 | т | ò | |

| 243 | 363 | 0xF3 | 11110011 | у | ó | |

| 244 | 364 | 0xF4 | 11110100 | ф | ô | |

| 245 | 365 | 0xF5 | 11110101 | х | õ | |

| 246 | 366 | 0xF6 | 11110110 | ц | ö | |

| 247 | 367 | 0xF7 | 11110111 | ч | ÷ | |

| 248 | 370 | 0xF8 | 11111000 | ш | ø | |

| 249 | 371 | 0xF9 | 11111001 | щ | ù | |

| 250 | 372 | 0xFA | 11111010 | ъ | ú | |

| 251 | 373 | 0xFB | 11111011 | ы | û | |

| 252 | 374 | 0xFC | 11111100 | ь | ü | |

| 253 | 375 | 0xFD | 11111101 | э | ý | |

| 254 | 376 | 0xFE | 11111110 | ю | þ | |

| 255 | 377 | 0xFF | 11111111 | я | ÿ |

The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) is a means of encoding characters for digital communications. It was originally developed in the early 1960s as early networked communications were being developed.

A 1969 RFC20 outlined the recommendation for adopting this 7-bit system for numerical representation within network interchange. By the late 1980s, the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) had assumed oversight of the ASCII standard.

Control Characters

Note the first 32 characters, decimal values 0-31, have been reserved for non-display characters. These are referred to as control characters and were originally intended as machine control signals to trigger events like system sounds (beep), network acknowledgments (ACK), and end of text (EOT).

Printable Characters

The ASCII-encoded characters for decimal values 0-31 do not print or render to displays like other characters. As such, attempting to use these characters for non-control functions typically results in the display of a default missing character symbol or other unwanted (and irrelevant) characters.

Modern Expanded ASCII

With the rise of 16, 32, and 64-bit machines, ASCII has seen several significant expansions over the years. The first expansion, called extended ASCII, used an 8-bit representation and extended to the range of 0-255. This range included common symbols and some internationalized versions of the American English alphabet.

This expansion to the original ASCII character codes has evolved in response to the growing need for more sophisticated ways to represent language around the world. After all, we’re a ways past the Internet being limited to a few researchers sending messages around the Southern California area.

ASCII Chart Uses

Today, ASCII is still used for certain internet mail protocols like SMTP (7-bit ASCII) such that transmitted data is first encoded into 7-bit ASCII, send across the network, and then decoded by the receiving host. This works for all kinds of files, including media!

Hexadecimal to ASCII

Hexadecimal can represent a wide range of values and is suited for use with modern 64-bit architectures. When converting hex to binary, decimal, or even octal—it can be convenient to have an easy reference to more commonly used values: like 5, 8, or 13. As such, ASCII number charts like the one here are often shown to include hexadecimal values.

Modern Integrations

Basic text editors like Notepad++ create ASCII text and more advanced programs like Microsoft Word generally have a “save as text” option. In addition, other more advanced encoding sets like UTF and Unicode are considered “supersets” of ASCII and mirror the first 128 characters to the ASCII characters. More than just a tribute; this mapping allows better compatibility across varying programs and programming languages. For example, Python’s ord() built-in function will return the ASCII value of any value character.

This article is about the character encoding. For other uses, see ASCII (disambiguation).

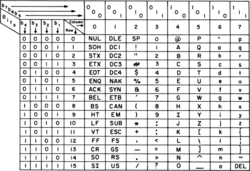

ASCII chart from MIL-STD-188-100 (1972) |

|

| MIME / IANA | us-ascii |

|---|---|

| Alias(es) | ISO-IR-006,[1] ANSI_X3.4-1968, ANSI_X3.4-1986, ISO_646.irv:1991, ISO646-US, us, IBM367, cp367[2] |

| Language(s) | English (made for; does not support all loanwords), Malay, Rotokas, Interlingua, Ido, and X-SAMPA |

| Classification | ISO/IEC 646 series |

| Extensions |

|

| Preceded by | ITA 2, FIELDATA |

| Succeeded by | ISO/IEC 8859, ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode) |

|

ASCII ( ASS-kee),[3]: 6 abbreviated from American Standard Code for Information Interchange, is a character encoding standard for electronic communication. ASCII codes represent text in computers, telecommunications equipment, and other devices. Because of technical limitations of computer systems at the time it was invented, ASCII has just 128 code points, of which only 95 are printable characters, which severely limited its scope. Many computer systems instead use Unicode, which has millions of code points, but the first 128 of these are the same as the ASCII set.

The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) prefers the name US-ASCII for this character encoding.[2]

ASCII is one of the IEEE milestones.

Overview[edit]

ASCII was developed from telegraph code. Its first commercial use was as a seven-bit teleprinter code promoted by Bell data services.[when?] Work on the ASCII standard began in May 1961, with the first meeting of the American Standards Association’s (ASA) (now the American National Standards Institute or ANSI) X3.2 subcommittee. The first edition of the standard was published in 1963,[4][5] underwent a major revision during 1967,[6][7] and experienced its most recent update during 1986.[8] Compared to earlier telegraph codes, the proposed Bell code and ASCII were both ordered for more convenient sorting (i.e., alphabetization) of lists and added features for devices other than teleprinters.[8]

The use of ASCII format for Network Interchange was described in 1969.[9] That document was formally elevated to an Internet Standard in 2015.[10]

Originally based on the (modern) English alphabet, ASCII encodes 128 specified characters into seven-bit integers as shown by the ASCII chart above.[11] Ninety-five of the encoded characters are printable: these include the digits 0 to 9, lowercase letters a to z, uppercase letters A to Z, and punctuation symbols. In addition, the original ASCII specification included 33 non-printing control codes which originated with Teletype machines; most of these are now obsolete,[12] although a few are still commonly used, such as the carriage return, line feed, and tab codes.

For example, lowercase i would be represented in the ASCII encoding by binary 1101001 = hexadecimal 69 (i is the ninth letter) = decimal 105.

Despite being an American standard, ASCII does not have a code point for the cent (¢). It also does not support English terms with diacritical marks such as résumé and jalapeño, or proper nouns with diacritical marks such as Beyoncé.

History[edit]

ASCII (1963). Control Pictures of equivalent controls are shown where they exist, or a grey dot otherwise.

The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) was developed under the auspices of a committee of the American Standards Association (ASA), called the X3 committee, by its X3.2 (later X3L2) subcommittee, and later by that subcommittee’s X3.2.4 working group (now INCITS). The ASA later became the United States of America Standards Institute (USASI),[3]: 211 and ultimately became the American National Standards Institute (ANSI).

With the other special characters and control codes filled in, ASCII was published as ASA X3.4-1963,[5][13] leaving 28 code positions without any assigned meaning, reserved for future standardization, and one unassigned control code.[3]: 66, 245 There was some debate at the time whether there should be more control characters rather than the lowercase alphabet.[3]: 435 The indecision did not last long: during May 1963 the CCITT Working Party on the New Telegraph Alphabet proposed to assign lowercase characters to sticks[a][14] 6 and 7,[15] and International Organization for Standardization TC 97 SC 2 voted during October to incorporate the change into its draft standard.[16] The X3.2.4 task group voted its approval for the change to ASCII at its May 1963 meeting.[17] Locating the lowercase letters in sticks[a][14] 6 and 7 caused the characters to differ in bit pattern from the upper case by a single bit, which simplified case-insensitive character matching and the construction of keyboards and printers.

The X3 committee made other changes, including other new characters (the brace and vertical bar characters),[18] renaming some control characters (SOM became start of header (SOH)) and moving or removing others (RU was removed).[3]: 247–248 ASCII was subsequently updated as USAS X3.4-1967,[6][19] then USAS X3.4-1968, ANSI X3.4-1977, and finally, ANSI X3.4-1986.[8][20]

Revisions of the ASCII standard:

- ASA X3.4-1963[3][5][19][20]

- ASA X3.4-1965 (approved, but not published, nevertheless used by IBM 2260 & 2265 Display Stations and IBM 2848 Display Control)[3]: 423, 425–428, 435–439 [21][19][20]

- USAS X3.4-1967[3][6][20]

- USAS X3.4-1968[3][20]

- ANSI X3.4-1977[20]

- ANSI X3.4-1986[8][20]

- ANSI X3.4-1986 (R1992)

- ANSI X3.4-1986 (R1997)

- ANSI INCITS 4-1986 (R2002)[22]

- ANSI INCITS 4-1986 (R2007)[23]

- (ANSI) INCITS 4-1986[R2012][24]

- (ANSI) INCITS 4-1986[R2017][25]

In the X3.15 standard, the X3 committee also addressed how ASCII should be transmitted (least significant bit first),[3]: 249–253 [26] and how it should be recorded on perforated tape. They proposed a 9-track standard for magnetic tape, and attempted to deal with some punched card formats.

Design considerations[edit]

Bit width[edit]

The X3.2 subcommittee designed ASCII based on the earlier teleprinter encoding systems. Like other character encodings, ASCII specifies a correspondence between digital bit patterns and character symbols (i.e. graphemes and control characters). This allows digital devices to communicate with each other and to process, store, and communicate character-oriented information such as written language. Before ASCII was developed, the encodings in use included 26 alphabetic characters, 10 numerical digits, and from 11 to 25 special graphic symbols. To include all these, and control characters compatible with the Comité Consultatif International Téléphonique et Télégraphique (CCITT) International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA2) standard of 1924,[27][28] FIELDATA (1956[citation needed]), and early EBCDIC (1963), more than 64 codes were required for ASCII.

ITA2 was in turn based on the 5-bit telegraph code that Émile Baudot invented in 1870 and patented in 1874.[28]

The committee debated the possibility of a shift function (like in ITA2), which would allow more than 64 codes to be represented by a six-bit code. In a shifted code, some character codes determine choices between options for the following character codes. It allows compact encoding, but is less reliable for data transmission, as an error in transmitting the shift code typically makes a long part of the transmission unreadable. The standards committee decided against shifting, and so ASCII required at least a seven-bit code.[3]: 215 §13.6, 236 §4

The committee considered an eight-bit code, since eight bits (octets) would allow two four-bit patterns to efficiently encode two digits with binary-coded decimal. However, it would require all data transmission to send eight bits when seven could suffice. The committee voted to use a seven-bit code to minimize costs associated with data transmission. Since perforated tape at the time could record eight bits in one position, it also allowed for a parity bit for error checking if desired.[3]: 217 §c, 236 §5 Eight-bit machines (with octets as the native data type) that did not use parity checking typically set the eighth bit to 0.[29]

Internal organization[edit]

The code itself was patterned so that most control codes were together and all graphic codes were together, for ease of identification. The first two so-called ASCII sticks[a][14] (32 positions) were reserved for control characters.[3]: 220, 236 8, 9) The «space» character had to come before graphics to make sorting easier, so it became position 20hex;[3]: 237 §10 for the same reason, many special signs commonly used as separators were placed before digits. The committee decided it was important to support uppercase 64-character alphabets, and chose to pattern ASCII so it could be reduced easily to a usable 64-character set of graphic codes,[3]: 228, 237 §14 as was done in the DEC SIXBIT code (1963). Lowercase letters were therefore not interleaved with uppercase. To keep options available for lowercase letters and other graphics, the special and numeric codes were arranged before the letters, and the letter A was placed in position 41hex to match the draft of the corresponding British standard.[3]: 238 §18 The digits 0–9 are prefixed with 011, but the remaining 4 bits correspond to their respective values in binary, making conversion with binary-coded decimal straightforward (for example, 5 in encoded to 0110101, where 5 is 0101 in binary).

Many of the non-alphanumeric characters were positioned to correspond to their shifted position on typewriters; an important subtlety is that these were based on mechanical typewriters, not electric typewriters.[30] Mechanical typewriters followed the de facto standard set by the Remington No. 2 (1878), the first typewriter with a shift key, and the shifted values of 23456789- were "#$%_&'() – early typewriters omitted 0 and 1, using O (capital letter o) and l (lowercase letter L) instead, but 1! and 0) pairs became standard once 0 and 1 became common. Thus, in ASCII !"#$% were placed in the second stick,[a][14] positions 1–5, corresponding to the digits 1–5 in the adjacent stick.[a][14] The parentheses could not correspond to 9 and 0, however, because the place corresponding to 0 was taken by the space character. This was accommodated by removing _ (underscore) from 6 and shifting the remaining characters, which corresponded to many European typewriters that placed the parentheses with 8 and 9. This discrepancy from typewriters led to bit-paired keyboards, notably the Teletype Model 33, which used the left-shifted layout corresponding to ASCII, differently from traditional mechanical typewriters.

Electric typewriters, notably the IBM Selectric (1961), used a somewhat different layout that has become de facto standard on computers – following the IBM PC (1981), especially Model M (1984) – and thus shift values for symbols on modern keyboards do not correspond as closely to the ASCII table as earlier keyboards did. The /? pair also dates to the No. 2, and the ,< .> pairs were used on some keyboards (others, including the No. 2, did not shift , (comma) or . (full stop) so they could be used in uppercase without unshifting). However, ASCII split the ;: pair (dating to No. 2), and rearranged mathematical symbols (varied conventions, commonly -* =+) to :* ;+ -=.

Some then-common typewriter characters were not included, notably ½ ¼ ¢, while ^ ` ~ were included as diacritics for international use, and < > for mathematical use, together with the simple line characters | (in addition to common /). The @ symbol was not used in continental Europe and the committee expected it would be replaced by an accented À in the French variation, so the @ was placed in position 40hex, right before the letter A.[3]: 243

The control codes felt essential for data transmission were the start of message (SOM), end of address (EOA), end of message (EOM), end of transmission (EOT), «who are you?» (WRU), «are you?» (RU), a reserved device control (DC0), synchronous idle (SYNC), and acknowledge (ACK). These were positioned to maximize the Hamming distance between their bit patterns.[3]: 243–245

Character order[edit]

ASCII-code order is also called ASCIIbetical order.[31] Collation of data is sometimes done in this order rather than «standard» alphabetical order (collating sequence). The main deviations in ASCII order are:

- All uppercase come before lowercase letters; for example, «Z» precedes «a»

- Digits and many punctuation marks come before letters

An intermediate order converts uppercase letters to lowercase before comparing ASCII values.

Character groups[edit]

Control characters[edit]

Early symbols assigned to the 32 control characters, space and delete characters. (MIL-STD-188-100, 1972)

ASCII reserves the first 32 codes (numbers 0–31 decimal) for control characters, which are characters originally intended not to represent printable information, but rather to control devices (such as printers) that make use of ASCII, or to provide meta-information about data streams such as those stored on magnetic tape.

For example, character 0x0A represents the «line feed» function (which causes a printer to advance its paper), and character 8 represents «backspace». RFC 2822 refers to control characters that do not include carriage return, line feed or white space as non-whitespace control characters.[32] Except for the control characters that prescribe elementary line-oriented formatting, ASCII does not define any mechanism for describing the structure or appearance of text within a document. Other schemes, such as markup languages, address page and document layout and formatting.

The original ASCII standard used only short descriptive phrases for each control character. The ambiguity this caused was sometimes intentional, for example where a character would be used slightly differently on a terminal link than on a data stream, and sometimes accidental, for example with the meaning of «delete».

Probably the most influential single device affecting the interpretation of these characters was the Teletype Model 33 ASR, which was a printing terminal with an available paper tape reader/punch option. Paper tape was a very popular medium for long-term program storage until the 1980s, less costly and in some ways less fragile than magnetic tape. In particular, the Teletype Model 33 machine assignments for codes 17 (control-Q, DC1, also known as XON), 19 (control-S, DC3, also known as XOFF), and 127 (delete) became de facto standards. The Model 33 was also notable for taking the description of control-G (code 7, BEL, meaning audibly alert the operator) literally, as the unit contained an actual bell which it rang when it received a BEL character. Because the keytop for the O key also showed a left-arrow symbol (from ASCII-1963, which had this character instead of underscore), a noncompliant use of code 15 (control-O, shift in) interpreted as «delete previous character» was also adopted by many early timesharing systems but eventually became neglected.

When a Teletype 33 ASR equipped with the automatic paper tape reader received a control-S (XOFF, an abbreviation for transmit off), it caused the tape reader to stop; receiving control-Q (XON, transmit on) caused the tape reader to resume. This so-called flow control technique became adopted by several early computer operating systems as a «handshaking» signal warning a sender to stop transmission because of impending buffer overflow; it persists to this day in many systems as a manual output control technique. On some systems, control-S retains its meaning but control-Q is replaced by a second control-S to resume output.

The 33 ASR also could be configured to employ control-R (DC2) and control-T (DC4) to start and stop the tape punch; on some units equipped with this function, the corresponding control character lettering on the keycap above the letter was TAPE and TAPE respectively.[33]

Delete vs backspace[edit]

The Teletype could not move its typehead backwards, so it did not have a key on its keyboard to send a BS (backspace). Instead, there was a key marked RUB OUT that sent code 127 (DEL). The purpose of this key was to erase mistakes in a manually-input paper tape: the operator had to push a button on the tape punch to back it up, then type the rubout, which punched all holes and replaced the mistake with a character that was intended to be ignored.[34] Teletypes were commonly used with the less-expensive computers from Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC); these systems had to use what keys were available, and thus the DEL character was assigned to erase the previous character.[35][36] Because of this, DEC video terminals (by default) sent the DEL character for the key marked «Backspace» while the separate key marked «Delete» sent an escape sequence; many other competing terminals sent a BS character for the backspace key.

The Unix terminal driver could only use one character to erase the previous character, this could be set to BS or DEL, but not both, resulting in recurring situations of ambiguity where users had to decide depending on what terminal they were using (shells that allow line editing, such as ksh, bash, and zsh, understand both). The assumption that no key sent a BS character allowed control+H to be used for other purposes, such as the «help» prefix command in GNU Emacs.[37]

Escape[edit]

Many more of the control characters have been assigned meanings quite different from their original ones. The «escape» character (ESC, code 27), for example, was intended originally to allow sending of other control characters as literals instead of invoking their meaning, an «escape sequence». This is the same meaning of «escape» encountered in URL encodings, C language strings, and other systems where certain characters have a reserved meaning. Over time this interpretation has been co-opted and has eventually been changed.

In modern usage, an ESC sent to the terminal usually indicates the start of a command sequence usually in the form of a so-called «ANSI escape code» (or, more properly, a «Control Sequence Introducer») from ECMA-48 (1972) and its successors, beginning with ESC followed by a «[» (left-bracket) character. In contrast, an ESC sent from the terminal is most often used as an out-of-band character used to terminate an operation or special mode, as in the TECO and vi text editors. In graphical user interface (GUI) and windowing systems, ESC generally causes an application to abort its current operation or to exit (terminate) altogether.

End of line[edit]

The inherent ambiguity of many control characters, combined with their historical usage, created problems when transferring «plain text» files between systems. The best example of this is the newline problem on various operating systems. Teletype machines required that a line of text be terminated with both «carriage return» (which moves the printhead to the beginning of the line) and «line feed» (which advances the paper one line without moving the printhead). The name «carriage return» comes from the fact that on a manual typewriter the carriage holding the paper moves while the typebars that strike the ribbon remain stationary. The entire carriage had to be pushed (returned) to the right in order to position the paper for the next line.

DEC operating systems (OS/8, RT-11, RSX-11, RSTS, TOPS-10, etc.) used both characters to mark the end of a line so that the console device (originally Teletype machines) would work. By the time so-called «glass TTYs» (later called CRTs or «dumb terminals») came along, the convention was so well established that backward compatibility necessitated continuing to follow it. When Gary Kildall created CP/M, he was inspired by some of the command line interface conventions used in DEC’s RT-11 operating system.

Until the introduction of PC DOS in 1981, IBM had no influence in this because their 1970s operating systems used EBCDIC encoding instead of ASCII, and they were oriented toward punch-card input and line printer output on which the concept of «carriage return» was meaningless. IBM’s PC DOS (also marketed as MS-DOS by Microsoft) inherited the convention by virtue of being loosely based on CP/M,[38] and Windows in turn inherited it from MS-DOS.

Requiring two characters to mark the end of a line introduces unnecessary complexity and ambiguity as to how to interpret each character when encountered by itself. To simplify matters, plain text data streams, including files, on Multics used line feed (LF) alone as a line terminator.[39]: 357 Unix and Unix-like systems, and Amiga systems, adopted this convention from Multics. On the other hand, the original Macintosh OS, Apple DOS, and ProDOS used carriage return (CR) alone as a line terminator; however, since Apple has now replaced these obsolete operating systems with the Unix-based macOS operating system, they now use line feed (LF) as well. The Radio Shack TRS-80 also used a lone CR to terminate lines.

Computers attached to the ARPANET included machines running operating systems such as TOPS-10 and TENEX using CR-LF line endings; machines running operating systems such as Multics using LF line endings; and machines running operating systems such as OS/360 that represented lines as a character count followed by the characters of the line and which used EBCDIC rather than ASCII encoding. The Telnet protocol defined an ASCII «Network Virtual Terminal» (NVT), so that connections between hosts with different line-ending conventions and character sets could be supported by transmitting a standard text format over the network. Telnet used ASCII along with CR-LF line endings, and software using other conventions would translate between the local conventions and the NVT.[40] The File Transfer Protocol adopted the Telnet protocol, including use of the Network Virtual Terminal, for use when transmitting commands and transferring data in the default ASCII mode.[41][42] This adds complexity to implementations of those protocols, and to other network protocols, such as those used for E-mail and the World Wide Web, on systems not using the NVT’s CR-LF line-ending convention.[43][44]

End of file/stream[edit]

The PDP-6 monitor,[35] and its PDP-10 successor TOPS-10,[36] used control-Z (SUB) as an end-of-file indication for input from a terminal. Some operating systems such as CP/M tracked file length only in units of disk blocks, and used control-Z to mark the end of the actual text in the file.[45] For these reasons, EOF, or end-of-file, was used colloquially and conventionally as a three-letter acronym for control-Z instead of SUBstitute. The end-of-text character (ETX), also known as control-C, was inappropriate for a variety of reasons, while using control-Z as the control character to end a file is analogous to the letter Z’s position at the end of the alphabet, and serves as a very convenient mnemonic aid. A historically common and still prevalent convention uses the ETX character convention to interrupt and halt a program via an input data stream, usually from a keyboard.

The Unix terminal driver uses the end-of-transmission character (EOT), also known as control-D, to indicate the end of a data stream.

In the C programming language, and in Unix conventions, the null character is used to terminate text strings; such null-terminated strings can be known in abbreviation as ASCIZ or ASCIIZ, where here Z stands for «zero».

Control code chart[edit]

| Binary | Oct | Dec | Hex | Abbreviation | Unicode Control Pictures[b] | Caret notation[c] | C escape sequence[d] | Name (1967) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | 1965 | 1967 | ||||||||

| 000 0000 | 000 | 0 | 00 | NULL | NUL | ␀ | ^@ | Null | ||

| 000 0001 | 001 | 1 | 01 | SOM | SOH | ␁ | ^A | Start of Heading | ||

| 000 0010 | 002 | 2 | 02 | EOA | STX | ␂ | ^B | Start of Text | ||

| 000 0011 | 003 | 3 | 03 | EOM | ETX | ␃ | ^C | End of Text | ||

| 000 0100 | 004 | 4 | 04 | EOT | ␄ | ^D | End of Transmission | |||

| 000 0101 | 005 | 5 | 05 | WRU | ENQ | ␅ | ^E | Enquiry | ||

| 000 0110 | 006 | 6 | 06 | RU | ACK | ␆ | ^F | Acknowledgement | ||

| 000 0111 | 007 | 7 | 07 | BELL | BEL | ␇ | ^G | a | Bell | |

| 000 1000 | 010 | 8 | 08 | FE0 | BS | ␈ | ^H | b | Backspace[e][f] | |

| 000 1001 | 011 | 9 | 09 | HT/SK | HT | ␉ | ^I | t | Horizontal Tab[g] | |

| 000 1010 | 012 | 10 | 0A | LF | ␊ | ^J | n | Line Feed | ||

| 000 1011 | 013 | 11 | 0B | VTAB | VT | ␋ | ^K | v | Vertical Tab | |

| 000 1100 | 014 | 12 | 0C | FF | ␌ | ^L | f | Form Feed | ||

| 000 1101 | 015 | 13 | 0D | CR | ␍ | ^M | r | Carriage Return[h] | ||

| 000 1110 | 016 | 14 | 0E | SO | ␎ | ^N | Shift Out | |||

| 000 1111 | 017 | 15 | 0F | SI | ␏ | ^O | Shift In | |||

| 001 0000 | 020 | 16 | 10 | DC0 | DLE | ␐ | ^P | Data Link Escape | ||

| 001 0001 | 021 | 17 | 11 | DC1 | ␑ | ^Q | Device Control 1 (often XON) | |||

| 001 0010 | 022 | 18 | 12 | DC2 | ␒ | ^R | Device Control 2 | |||

| 001 0011 | 023 | 19 | 13 | DC3 | ␓ | ^S | Device Control 3 (often XOFF) | |||

| 001 0100 | 024 | 20 | 14 | DC4 | ␔ | ^T | Device Control 4 | |||

| 001 0101 | 025 | 21 | 15 | ERR | NAK | ␕ | ^U | Negative Acknowledgement | ||

| 001 0110 | 026 | 22 | 16 | SYNC | SYN | ␖ | ^V | Synchronous Idle | ||

| 001 0111 | 027 | 23 | 17 | LEM | ETB | ␗ | ^W | End of Transmission Block | ||

| 001 1000 | 030 | 24 | 18 | S0 | CAN | ␘ | ^X | Cancel | ||

| 001 1001 | 031 | 25 | 19 | S1 | EM | ␙ | ^Y | End of Medium | ||

| 001 1010 | 032 | 26 | 1A | S2 | SS | SUB | ␚ | ^Z | Substitute | |

| 001 1011 | 033 | 27 | 1B | S3 | ESC | ␛ | ^[ | e[i] | Escape[j] | |

| 001 1100 | 034 | 28 | 1C | S4 | FS | ␜ | ^ | File Separator | ||

| 001 1101 | 035 | 29 | 1D | S5 | GS | ␝ | ^] | Group Separator | ||

| 001 1110 | 036 | 30 | 1E | S6 | RS | ␞ | ^^[k] | Record Separator | ||

| 001 1111 | 037 | 31 | 1F | S7 | US | ␟ | ^_ | Unit Separator | ||

| 111 1111 | 177 | 127 | 7F | DEL | ␡ | ^? | Delete[l][f] |

Other representations might be used by specialist equipment, for example ISO 2047 graphics or hexadecimal numbers.

Printable characters[edit]

Codes 20hex to 7Ehex, known as the printable characters, represent letters, digits, punctuation marks, and a few miscellaneous symbols. There are 95 printable characters in total.[m]

Code 20hex, the «space» character, denotes the space between words, as produced by the space bar of a keyboard. Since the space character is considered an invisible graphic (rather than a control character)[3]: 223 [46] it is listed in the table below instead of in the previous section.

Code 7Fhex corresponds to the non-printable «delete» (DEL) control character and is therefore omitted from this chart; it is covered in the previous section’s chart. Earlier versions of ASCII used the up arrow instead of the caret (5Ehex) and the left arrow instead of the underscore (5Fhex).[5][47]

| Binary | Oct | Dec | Hex | Glyph | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | 1965 | 1967 | ||||

| 010 0000 | 040 | 32 | 20 | space | ||

| 010 0001 | 041 | 33 | 21 | ! | ||

| 010 0010 | 042 | 34 | 22 | « | ||

| 010 0011 | 043 | 35 | 23 | # | ||

| 010 0100 | 044 | 36 | 24 | $ | ||

| 010 0101 | 045 | 37 | 25 | % | ||

| 010 0110 | 046 | 38 | 26 | & | ||

| 010 0111 | 047 | 39 | 27 | ‘ | ||

| 010 1000 | 050 | 40 | 28 | ( | ||

| 010 1001 | 051 | 41 | 29 | ) | ||

| 010 1010 | 052 | 42 | 2A | * | ||

| 010 1011 | 053 | 43 | 2B | + | ||

| 010 1100 | 054 | 44 | 2C | , | ||

| 010 1101 | 055 | 45 | 2D | — | ||

| 010 1110 | 056 | 46 | 2E | . | ||

| 010 1111 | 057 | 47 | 2F | / | ||

| 011 0000 | 060 | 48 | 30 | 0 | ||

| 011 0001 | 061 | 49 | 31 | 1 | ||

| 011 0010 | 062 | 50 | 32 | 2 | ||

| 011 0011 | 063 | 51 | 33 | 3 | ||

| 011 0100 | 064 | 52 | 34 | 4 | ||

| 011 0101 | 065 | 53 | 35 | 5 | ||

| 011 0110 | 066 | 54 | 36 | 6 | ||

| 011 0111 | 067 | 55 | 37 | 7 | ||

| 011 1000 | 070 | 56 | 38 | 8 | ||

| 011 1001 | 071 | 57 | 39 | 9 | ||

| 011 1010 | 072 | 58 | 3A | : | ||

| 011 1011 | 073 | 59 | 3B | ; | ||

| 011 1100 | 074 | 60 | 3C | < | ||

| 011 1101 | 075 | 61 | 3D | = | ||

| 011 1110 | 076 | 62 | 3E | > | ||

| 011 1111 | 077 | 63 | 3F | ? | ||

| 100 0000 | 100 | 64 | 40 | @ | ` | @ |

| 100 0001 | 101 | 65 | 41 | A | ||

| 100 0010 | 102 | 66 | 42 | B | ||

| 100 0011 | 103 | 67 | 43 | C | ||

| 100 0100 | 104 | 68 | 44 | D | ||

| 100 0101 | 105 | 69 | 45 | E | ||

| 100 0110 | 106 | 70 | 46 | F | ||

| 100 0111 | 107 | 71 | 47 | G | ||

| 100 1000 | 110 | 72 | 48 | H | ||

| 100 1001 | 111 | 73 | 49 | I | ||

| 100 1010 | 112 | 74 | 4A | J | ||

| 100 1011 | 113 | 75 | 4B | K | ||

| 100 1100 | 114 | 76 | 4C | L | ||

| 100 1101 | 115 | 77 | 4D | M | ||

| 100 1110 | 116 | 78 | 4E | N | ||

| 100 1111 | 117 | 79 | 4F | O | ||

| 101 0000 | 120 | 80 | 50 | P | ||

| 101 0001 | 121 | 81 | 51 | Q | ||

| 101 0010 | 122 | 82 | 52 | R | ||

| 101 0011 | 123 | 83 | 53 | S | ||

| 101 0100 | 124 | 84 | 54 | T | ||

| 101 0101 | 125 | 85 | 55 | U | ||

| 101 0110 | 126 | 86 | 56 | V | ||

| 101 0111 | 127 | 87 | 57 | W | ||

| 101 1000 | 130 | 88 | 58 | X | ||

| 101 1001 | 131 | 89 | 59 | Y | ||

| 101 1010 | 132 | 90 | 5A | Z | ||

| 101 1011 | 133 | 91 | 5B | [ | ||

| 101 1100 | 134 | 92 | 5C | ~ | ||

| 101 1101 | 135 | 93 | 5D | ] | ||

| 101 1110 | 136 | 94 | 5E | ↑ | ^ | |

| 101 1111 | 137 | 95 | 5F | ← | _ | |

| 110 0000 | 140 | 96 | 60 | @ | ` | |

| 110 0001 | 141 | 97 | 61 | a | ||

| 110 0010 | 142 | 98 | 62 | b | ||

| 110 0011 | 143 | 99 | 63 | c | ||

| 110 0100 | 144 | 100 | 64 | d | ||

| 110 0101 | 145 | 101 | 65 | e | ||

| 110 0110 | 146 | 102 | 66 | f | ||

| 110 0111 | 147 | 103 | 67 | g | ||

| 110 1000 | 150 | 104 | 68 | h | ||

| 110 1001 | 151 | 105 | 69 | i | ||

| 110 1010 | 152 | 106 | 6A | j | ||

| 110 1011 | 153 | 107 | 6B | k | ||

| 110 1100 | 154 | 108 | 6C | l | ||

| 110 1101 | 155 | 109 | 6D | m | ||

| 110 1110 | 156 | 110 | 6E | n | ||

| 110 1111 | 157 | 111 | 6F | o | ||

| 111 0000 | 160 | 112 | 70 | p | ||

| 111 0001 | 161 | 113 | 71 | q | ||

| 111 0010 | 162 | 114 | 72 | r | ||

| 111 0011 | 163 | 115 | 73 | s | ||

| 111 0100 | 164 | 116 | 74 | t | ||

| 111 0101 | 165 | 117 | 75 | u | ||

| 111 0110 | 166 | 118 | 76 | v | ||

| 111 0111 | 167 | 119 | 77 | w | ||

| 111 1000 | 170 | 120 | 78 | x | ||

| 111 1001 | 171 | 121 | 79 | y | ||

| 111 1010 | 172 | 122 | 7A | z | ||

| 111 1011 | 173 | 123 | 7B | { | ||

| 111 1100 | 174 | 124 | 7C | ACK | ¬ | | |

| 111 1101 | 175 | 125 | 7D | } | ||

| 111 1110 | 176 | 126 | 7E | ESC | | | ~ |

Character set[edit]

| ASCII (1977/1986) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| 0x | NUL | SOH | STX | ETX | EOT | ENQ | ACK | BEL | BS | HT | LF | VT | FF | CR | SO | SI |

| 1x | DLE | DC1 | DC2 | DC3 | DC4 | NAK | SYN | ETB | CAN | EM | SUB | ESC | FS | GS | RS | US |

| 2x | SP | ! | » | # | $ | % | & | ‘ | ( | ) | * | + | , | — | . | / |

| 3x | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | : | ; | < | = | > | ? |

| 4x | @ | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O |

| 5x | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | [ | ] | ^ | _ | |

| 6x | ` | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o |

| 7x | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z | { | | | } | ~ | DEL |

|

Changed or added in 1963 version Changed in both 1963 version and 1965 draft |

Usage[edit]

ASCII was first used commercially during 1963 as a seven-bit teleprinter code for American Telephone & Telegraph’s TWX (TeletypeWriter eXchange) network. TWX originally used the earlier five-bit ITA2, which was also used by the competing Telex teleprinter system. Bob Bemer introduced features such as the escape sequence.[4] His British colleague Hugh McGregor Ross helped to popularize this work – according to Bemer, «so much so that the code that was to become ASCII was first called the Bemer–Ross Code in Europe».[48] Because of his extensive work on ASCII, Bemer has been called «the father of ASCII».[49]

On March 11, 1968, US President Lyndon B. Johnson mandated that all computers purchased by the United States Federal Government support ASCII, stating:[50][51][52]

I have also approved recommendations of the Secretary of Commerce [Luther H. Hodges] regarding standards for recording the Standard Code for Information Interchange on magnetic tapes and paper tapes when they are used in computer operations.

All computers and related equipment configurations brought into the Federal Government inventory on and after July 1, 1969, must have the capability to use the Standard Code for Information Interchange and the formats prescribed by the magnetic tape and paper tape standards when these media are used.

ASCII was the most common character encoding on the World Wide Web until December 2007, when UTF-8 encoding surpassed it; UTF-8 is backward compatible with ASCII.[53][54][55]

Variants and derivations[edit]

As computer technology spread throughout the world, different standards bodies and corporations developed many variations of ASCII to facilitate the expression of non-English languages that used Roman-based alphabets. One could class some of these variations as «ASCII extensions», although some misuse that term to represent all variants, including those that do not preserve ASCII’s character-map in the 7-bit range. Furthermore, the ASCII extensions have also been mislabelled as ASCII.

7-bit codes[edit]

From early in its development,[56] ASCII was intended to be just one of several national variants of an international character code standard.

Other international standards bodies have ratified character encodings such as ISO 646 (1967) that are identical or nearly identical to ASCII, with extensions for characters outside the English alphabet and symbols used outside the United States, such as the symbol for the United Kingdom’s pound sterling (£); e.g. with code page 1104. Almost every country needed an adapted version of ASCII, since ASCII suited the needs of only the US and a few other countries. For example, Canada had its own version that supported French characters.

Many other countries developed variants of ASCII to include non-English letters (e.g. é, ñ, ß, Ł), currency symbols (e.g. £, ¥), etc. See also YUSCII (Yugoslavia).

It would share most characters in common, but assign other locally useful characters to several code points reserved for «national use». However, the four years that elapsed between the publication of ASCII-1963 and ISO’s first acceptance of an international recommendation during 1967[57] caused ASCII’s choices for the national use characters to seem to be de facto standards for the world, causing confusion and incompatibility once other countries did begin to make their own assignments to these code points.

ISO/IEC 646, like ASCII, is a 7-bit character set. It does not make any additional codes available, so the same code points encoded different characters in different countries. Escape codes were defined to indicate which national variant applied to a piece of text, but they were rarely used, so it was often impossible to know what variant to work with and, therefore, which character a code represented, and in general, text-processing systems could cope with only one variant anyway.

Because the bracket and brace characters of ASCII were assigned to «national use» code points that were used for accented letters in other national variants of ISO/IEC 646, a German, French, or Swedish, etc. programmer using their national variant of ISO/IEC 646, rather than ASCII, had to write, and, thus, read, something such as

ä aÄiÜ = 'Ön'; ü

instead of

{ a[i] = 'n'; }

C trigraphs were created to solve this problem for ANSI C, although their late introduction and inconsistent implementation in compilers limited their use. Many programmers kept their computers on US-ASCII, so plain-text in Swedish, German etc. (for example, in e-mail or Usenet) contained «{, }» and similar variants in the middle of words, something those programmers got used to. For example, a Swedish programmer mailing another programmer asking if they should go for lunch, could get «N{ jag har sm|rg}sar» as the answer, which should be «Nä jag har smörgåsar» meaning «No I’ve got sandwiches».

In Japan and Korea, still as of the 2020s, a variation of ASCII is used, in which the backslash (5C hex) is rendered as ¥ (a Yen sign, in Japan) or ₩ (a Won sign, in Korea). This means that, for example, the file path C:UsersSmith is shown as C:¥Users¥Smith (in Japan) or C:₩Users₩Smith (in Korea).

In Europe, teletext character sets, which are variants of ASCII, are used for broadcast TV subtitles, defined by World System Teletext and broadcast using the DVB-TXT standard for embedding teletext into DVB transmissions.[58] In the case that the subtitles were initially authored for teletext and converted, the derived subtitle formats are constrained to the same character sets.

8-bit codes[edit]

Eventually, as 8-, 16-, and 32-bit (and later 64-bit) computers began to replace 12-, 18-, and 36-bit computers as the norm, it became common to use an 8-bit byte to store each character in memory, providing an opportunity for extended, 8-bit relatives of ASCII. In most cases these developed as true extensions of ASCII, leaving the original character-mapping intact, but adding additional character definitions after the first 128 (i.e., 7-bit) characters.

Encodings include ISCII (India), VISCII (Vietnam). Although these encodings are sometimes referred to as ASCII, true ASCII is defined strictly only by the ANSI standard.

Most early home computer systems developed their own 8-bit character sets containing line-drawing and game glyphs, and often filled in some or all of the control characters from 0 to 31 with more graphics. Kaypro CP/M computers used the «upper» 128 characters for the Greek alphabet.

The PETSCII code Commodore International used for their 8-bit systems is probably unique among post-1970 codes in being based on ASCII-1963, instead of the more common ASCII-1967, such as found on the ZX Spectrum computer. Atari 8-bit computers and Galaksija computers also used ASCII variants.

The IBM PC defined code page 437, which replaced the control characters with graphic symbols such as smiley faces, and mapped additional graphic characters to the upper 128 positions. Operating systems such as DOS supported these code pages, and manufacturers of IBM PCs supported them in hardware. Digital Equipment Corporation developed the Multinational Character Set (DEC-MCS) for use in the popular VT220 terminal as one of the first extensions designed more for international languages than for block graphics. The Macintosh defined Mac OS Roman and Postscript defined another character set: both sets contained «international» letters, typographic symbols and punctuation marks instead of graphics, more like modern character sets.

The ISO/IEC 8859 standard (derived from the DEC-MCS) finally provided a standard that most systems copied (at least as accurately as they copied ASCII, but with many substitutions). A popular further extension designed by Microsoft, Windows-1252 (often mislabeled as ISO-8859-1), added the typographic punctuation marks needed for traditional text printing. ISO-8859-1, Windows-1252, and the original 7-bit ASCII were the most common character encodings until 2008 when UTF-8 became more common.[54]

ISO/IEC 4873 introduced 32 additional control codes defined in the 80–9F hexadecimal range, as part of extending the 7-bit ASCII encoding to become an 8-bit system.[59]

Unicode[edit]

Unicode and the ISO/IEC 10646 Universal Character Set (UCS) have a much wider array of characters and their various encoding forms have begun to supplant ISO/IEC 8859 and ASCII rapidly in many environments. While ASCII is limited to 128 characters, Unicode and the UCS support more characters by separating the concepts of unique identification (using natural numbers called code points) and encoding (to 8-, 16-, or 32-bit binary formats, called UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32, respectively).

ASCII was incorporated into the Unicode (1991) character set as the first 128 symbols, so the 7-bit ASCII characters have the same numeric codes in both sets. This allows UTF-8 to be backward compatible with 7-bit ASCII, as a UTF-8 file containing only ASCII characters is identical to an ASCII file containing the same sequence of characters. Even more importantly, forward compatibility is ensured as software that recognizes only 7-bit ASCII characters as special and does not alter bytes with the highest bit set (as is often done to support 8-bit ASCII extensions such as ISO-8859-1) will preserve UTF-8 data unchanged.[60]

See also[edit]

- 3568 ASCII, an asteroid named after the character encoding

- Alt codes – Method for entering characters into a computer

- ASCII 8 – ASCII code 08, «BS» or Backspace

- ASCII art – Computer art form using text characters

- ASCII Ribbon Campaign – Campaign for plain text (only) emails

- Basic Latin (Unicode block) (ASCII as a subset of Unicode)

- Extended ASCII – Nick-name for 8-bit ASCII-derived character sets

- HTML decimal character rendering

- Jargon File, a glossary of computer programmer slang which includes a list of common slang names for ASCII characters

- List of computer character sets

- List of Unicode characters

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e The 128 characters of the 7-bit ASCII character set are divided into eight 16-character groups called sticks 0–7, associated with the three most-significant bits.[14] Depending on the horizontal or vertical representation of the character map, sticks correspond with either table rows or columns.

- ^ The Unicode characters from the «Control Pictures» area U+2400 to U+2421 reserved for representing control characters when it is necessary to print or display them rather than have them perform their intended function. Some browsers may not display these properly.

- ^ Caret notation is often used to represent control characters on a terminal. On most text terminals, holding down the Ctrl key while typing the second character will type the control character. Sometimes the shift key is not needed, for instance

^@may be typable with just Ctrl and 2. - ^ Character escape sequences in C programming language and many other languages influenced by it, such as Java and Perl (though not all implementations necessarily support all escape sequences).

- ^ The Backspace character can also be entered by pressing the ← Backspace key on some systems.

- ^ a b The ambiguity of Backspace is due to early terminals designed assuming the main use of the keyboard would be to manually punch paper tape while not connected to a computer. To delete the previous character, one had to back up the paper tape punch, which for mechanical and simplicity reasons was a button on the punch itself and not the keyboard, then type the rubout character. They therefore placed a key producing rubout at the location used on typewriters for backspace. When systems used these terminals and provided command-line editing, they had to use the «rubout» code to perform a backspace, and often did not interpret the backspace character (they might echo «^H» for backspace). Other terminals not designed for paper tape made the key at this location produce Backspace, and systems designed for these used that character to back up. Since the delete code often produced a backspace effect, this also forced terminal manufacturers to make any Delete key produce something other than the Delete character.

- ^ The Tab character can also be entered by pressing the Tab ↹ key on most systems.

- ^ The Carriage Return character can also be entered by pressing the ↵ Enter or Return key on most systems.

- ^ The e escape sequence is not part of ISO C and many other language specifications. However, it is understood by several compilers, including GCC.

- ^ The Escape character can also be entered by pressing the Esc key on some systems.

- ^ ^^ means Ctrl+^ (pressing the «Ctrl» and caret keys).

- ^ The Delete character can sometimes be entered by pressing the ← Backspace key on some systems.

- ^ Printed out, the characters are:

!"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~

References[edit]

- ^ ANSI (1975-12-01). ISO-IR-6: ASCII Graphic character set (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-03-10.

- ^ a b «Character Sets». Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA). 2007-05-14. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Mackenzie, Charles E. (1980). Coded Character Sets, History and Development (PDF). The Systems Programming Series (1 ed.). Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 6, 66, 211, 215, 217, 220, 223, 228, 236–238, 243–245, 247–253, 423, 425–428, 435–439. ISBN 978-0-201-14460-4. LCCN 77-90165. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 26, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ a b Brandel, Mary (1999-07-06). «1963: The Debut of ASCII». CNN. Archived from the original on 2013-06-17. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ^ a b c d «American Standard Code for Information Interchange, ASA X3.4-1963». American Standards Association (ASA). 1963-06-17. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- ^ a b c USA Standard Code for Information Interchange, USAS X3.4-1967 (Technical report). United States of America Standards Institute (USASI). 1967-07-07.

- ^ Jennings, Thomas Daniel (2016-04-20) [1999]. «An annotated history of some character codes or ASCII: American Standard Code for Information Infiltration». Sensitive Research (SR-IX). Retrieved 2020-03-08.

- ^ a b c d American National Standard for Information Systems — Coded Character Sets — 7-Bit American National Standard Code for Information Interchange (7-Bit ASCII), ANSI X3.4-1986 (Technical report). American National Standards Institute (ANSI). 1986-03-26.

- ^ Vint Cerf (1969-10-16). ASCII format for Network Interchange. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC0020. RFC 20.

- ^ Barry Leiba (2015-01-12). «Correct classification of RFC 20 (ASCII format) to Internet Standard». IETF.

- ^ Shirley, R. (August 2007). Internet Security Glossary, Version 2. doi:10.17487/RFC4949. RFC 4949. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ^ Maini, Anil Kumar (2007). Digital Electronics: Principles, Devices and Applications. John Wiley and Sons. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-470-03214-5.

In addition, it defines codes for 33 nonprinting, mostly obsolete control characters that affect how the text is processed.

- ^ Bukstein, Ed (July 1964). «Binary Computer Codes and ASCII». Electronics World. 72 (1): 28–29. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ^ a b c d e f Bemer, Robert William (1980). «Chapter 1: Inside ASCII» (PDF). General Purpose Software. Best of Interface Age. Vol. 2. Portland, OR, USA: dilithium Press. pp. 1–50. ISBN 978-0-918398-37-6. LCCN 79-67462. Archived from the original on 2016-08-27. Retrieved 2016-08-27, from:

- Bemer, Robert William (May 1978). «Inside ASCII – Part I». Interface Age. 3 (5): 96–102.

- Bemer, Robert William (June 1978). «Inside ASCII – Part II». Interface Age. 3 (6): 64–74.

- Bemer, Robert William (July 1978). «Inside ASCII – Part III». Interface Age. 3 (7): 80–87.

- ^ Brief Report: Meeting of CCITT Working Party on the New Telegraph Alphabet, May 13–15, 1963.

- ^ Report of ISO/TC/97/SC 2 – Meeting of October 29–31, 1963.

- ^ Report on Task Group X3.2.4, June 11, 1963, Pentagon Building, Washington, DC.

- ^ Report of Meeting No. 8, Task Group X3.2.4, December 17 and 18, 1963

- ^ a b c Winter, Dik T. (2010) [2003]. «US and International standards: ASCII». Archived from the original on 2010-01-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g Salste, Tuomas (January 2016). «7-bit character sets: Revisions of ASCII». Aivosto Oy. urn:nbn:fi-fe201201011004. Archived from the original on 2016-06-13. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ^ «Information». Scientific American (special edition). 215 (3). September 1966. JSTOR e24931041.

- ^ Korpela, Jukka K. (2014-03-14) [2006-06-07]. Unicode Explained – Internationalize Documents, Programs, and Web Sites (2nd release of 1st ed.). O’Reilly Media, Inc. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-596-10121-3.

- ^ ANSI INCITS 4-1986 (R2007): American National Standard for Information Systems – Coded Character Sets – 7-Bit American National Standard Code for Information Interchange (7-Bit ASCII), 2007 [1986]

- ^ «INCITS 4-1986[R2012]: Information Systems — Coded Character Sets — 7-Bit American National Standard Code for Information Interchange (7-Bit ASCII)». 2012-06-15. Archived from the original on 2020-02-28. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ «INCITS 4-1986[R2017]: Information Systems — Coded Character Sets — 7-Bit American National Standard Code for Information Interchange (7-Bit ASCII)». 2017-11-02 [2017-06-09]. Archived from the original on 2020-02-28. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ Bit Sequencing of the American National Standard Code for Information Interchange in Serial-by-Bit Data Transmission, American National Standards Institute (ANSI), 1966, X3.15-1966

- ^ «BruXy: Radio Teletype communication». 2005-10-10. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

The transmitted code use International Telegraph Alphabet No. 2 (ITA-2) which was introduced by CCITT in 1924.

- ^ a b Smith, Gil (2001). «Teletype Communication Codes» (PDF). Baudot.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ Sawyer, Stanley A.; Krantz, Steven George (1995). A TeX Primer for Scientists. CRC Press. p. 13. Bibcode:1995tps..book…..S. ISBN 978-0-8493-7159-2. Archived from the original on 2016-12-22. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ Savard, John J. G. «Computer Keyboards». Archived from the original on 2014-09-24. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- ^ «ASCIIbetical definition». PC Magazine. Archived from the original on 2013-03-09. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ^ Resnick, P. (April 2001). Resnick, P (ed.). Internet Message Format. doi:10.17487/RFC2822. RFC 2822. Retrieved 2016-06-13. (NB. NO-WS-CTL.)

- ^ McConnell, Robert; Haynes, James; Warren, Richard. «Understanding ASCII Codes». Archived from the original on 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

- ^ Barry Margolin (2014-05-29). «Re: editor and word processor history (was: Re: RTF for emacs)». help-gnu-emacs (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- ^ a b «PDP-6 Multiprogramming System Manual» (PDF). Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). 1965. p. 43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- ^ a b «PDP-10 Reference Handbook, Book 3, Communicating with the Monitor» (PDF). Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). 1969. p. 5-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-11-15. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- ^ «Help — GNU Emacs Manual». Archived from the original on 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ^ Tim Paterson (2007-08-08). «Is DOS a Rip-Off of CP/M?». DosMan Drivel. Archived from the original on 2018-04-20. Retrieved 2018-04-19.

- ^ Ossanna, J. F.; Saltzer, J. H. (November 17–19, 1970). «Technical and human engineering problems in connecting terminals to a time-sharing system» (PDF). Proceedings of the November 17–19, 1970, Fall Joint Computer Conference (FJCC). AFIPS Press. pp. 355–362. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-08-19. Retrieved 2013-01-29.

Using a «new-line» function (combined carriage-return and line-feed) is simpler for both man and machine than requiring both functions for starting a new line; the American National Standard X3.4-1968 permits the line-feed code to carry the new-line meaning.

- ^ O’Sullivan, T. (1971-05-19). TELNET Protocol. Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). pp. 4–5. doi:10.17487/RFC0158. RFC 158. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ Neigus, Nancy J. (1973-08-12). File Transfer Protocol. Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). doi:10.17487/RFC0542. RFC 542. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ Postel, Jon (June 1980). File Transfer Protocol. Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). doi:10.17487/RFC0765. RFC 765. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ «EOL translation plan for Mercurial». Mercurial. Archived from the original on 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2017-06-24.

- ^ Bernstein, Daniel J. «Bare LFs in SMTP». Archived from the original on 2011-10-29. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ CP/M 1.4 Interface Guide (PDF). Digital Research. 1978. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-29. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ^ Cerf, Vinton Gray (1969-10-16). ASCII format for Network Interchange. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC0020. RFC 20. Retrieved 2016-06-13. (NB. Almost identical wording to USAS X3.4-1968 except for the intro.)

- ^ Haynes, Jim (2015-01-13). «First-Hand: Chad is Our Most Important Product: An Engineer’s Memory of Teletype Corporation». Engineering and Technology History Wiki (ETHW). Retrieved 2023-02-14.

There was the change from 1961 ASCII to 1968 ASCII. Some computer languages used characters in 1961 ASCII such as up arrow and left arrow. These characters disappeared from 1968 ASCII. We worked with Fred Mocking, who by now was in Sales at Teletype, on a type cylinder that would compromise the changing characters so that the meanings of 1961 ASCII were not totally lost. The underscore character was made rather wedge-shaped so it could also serve as a left arrow.

- ^ Bemer, Robert William. «Bemer meets Europe (Computer Standards) – Computer History Vignettes». Trailing-edge.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2008-04-14. (NB. Bemer was employed at IBM at that time.)

- ^ «Robert William Bemer: Biography». 2013-03-09. Archived from the original on 2016-06-16.

- ^ Johnson, Lyndon Baines (1968-03-11). «Memorandum Approving the Adoption by the Federal Government of a Standard Code for Information Interchange». The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on 2007-09-14. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ^ Richard S. Shuford (1996-12-20). «Re: Early history of ASCII?». Newsgroup: alt.folklore.computers. Usenet: Pine.SUN.3.91.961220100220.13180C-100000@duncan.cs.utk.edu.

- ^ Folts, Harold C.; Karp, Harry, eds. (1982-02-01). Compilation of Data Communications Standards (2nd revised ed.). McGraw-Hill Inc. ISBN 978-0-07-021457-6.

- ^ Dubost, Karl (2008-05-06). «UTF-8 Growth on the Web». W3C Blog. World Wide Web Consortium. Archived from the original on 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- ^ a b Davis, Mark (2008-05-05). «Moving to Unicode 5.1». Official Google Blog. Archived from the original on 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- ^ Davis, Mark (2010-01-28). «Unicode nearing 50% of the web». Official Google Blog. Archived from the original on 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- ^ «Specific Criteria», attachment to memo from R. W. Reach, «X3-2 Meeting – September 14 and 15», September 18, 1961

- ^ Maréchal, R. (1967-12-22), ISO/TC 97 – Computers and Information Processing: Acceptance of Draft ISO Recommendation No. 1052

- ^ «DVB-TXT (Teletext) Specification for conveying ITU-R System B Teletext in DVB bitstreams».

- ^ The Unicode Consortium (2006-10-27). «Chapter 13: Special Areas and Format Characters» (PDF). In Allen, Julie D. (ed.). The Unicode standard, Version 5.0. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, US: Addison-Wesley Professional. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-321-48091-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2015-03-13.

- ^ «utf-8(7) – Linux manual page». Man7.org. 2014-02-26. Archived from the original on 2014-04-22. Retrieved 2014-04-21.

Further reading[edit]

- Bemer, Robert William (1960). «A Proposal for Character Code Compatibility». Communications of the ACM. 3 (2): 71–72. doi:10.1145/366959.366961. S2CID 9591147.

- Bemer, Robert William (2003-05-23). «The Babel of Codes Prior to ASCII: The 1960 Survey of Coded Character Sets: The Reasons for ASCII». Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2016-05-09, from:

- Bemer, Robert William (December 1960). «Survey of coded character representation». Communications of the ACM. 3 (12): 639–641. doi:10.1145/367487.367493. S2CID 21403172.

- Smith, H. J.; Williams, F. A. (December 1960). «Survey of punched card codes». Communications of the ACM. 3 (12): 642. doi:10.1145/367487.367491.

- «American National Standard Code for Information Interchange | ANSI X3.4-1977» (PDF). National Institute for Standards. 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. (facsimile, not machine readable)

- Robinson, G. S.; Cargill, C. (1996). «History and impact of computer standards». Computer. Vol. 29, no. 10. pp. 79–85. doi:10.1109/2.539725.

- Mullendore, Ralph Elvin (1964) [1963]. Ptak, John F. (ed.). «On the Early Development of ASCII – The History of ASCII». JF Ptak Science Books (published March 2012). Archived from the original on 2016-05-26. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to ASCII.

- «C0 Controls and Basic Latin – Range: 0000–007F» (PDF). The Unicode Standard 8.0. Unicode, Inc. 2015 [1991]. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-05-26. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Fischer, Eric. «The Evolution of Character Codes, 1874–1968». CiteSeerX 10.1.1.96.678. [1]

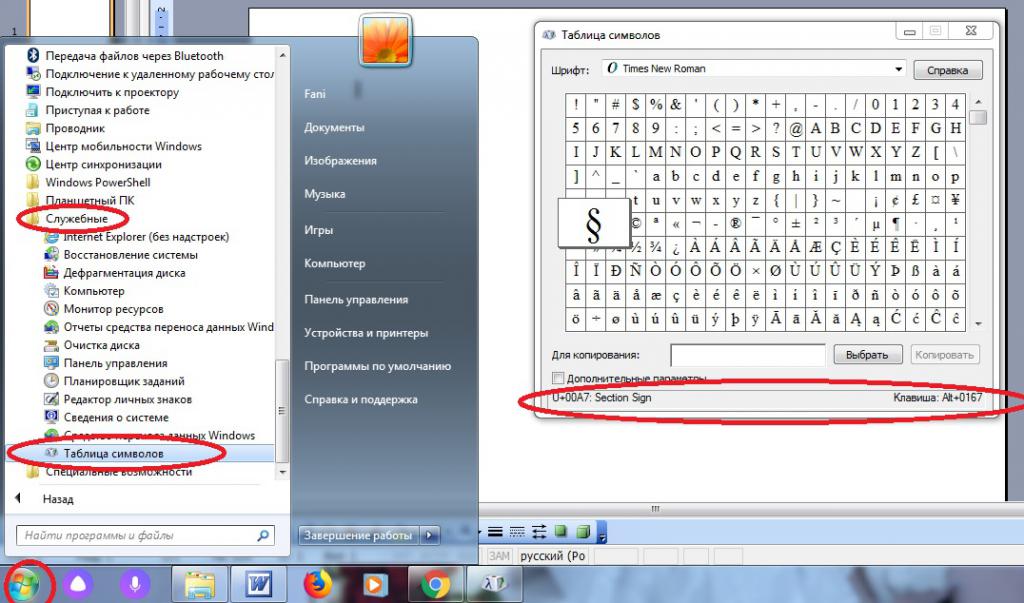

На чтение 9 мин Просмотров 2.1к. Опубликовано 07.05.2019

Содержание

- Определение

- Какими бывают

- Где искать в Windows

- В MS Word

- Способы обработки кода

- В этой статье

- Вставка символа ASCII или Юникода в документ

- Вставка символов ASCII

- Вставка символов Юникода

- Использование таблицы символов

- Word. Библиотека значков или как вставить забавный рисунок в текст документа

Таблица кодов символов в современных компьютерах может быть использована любым юзером. Что это такое? И где найти подобный элемент? Как им пользоваться и для каких целей? Далее постараемся дать ответы на все перечисленные вопросы. Обычно таблицы символов позволяют печатать уникальные знаки в текстовых документов. Главное — знать, какими они бывают, а также где искать соответствующую информацию. Все намного проще, чем кажется.

Определение

Что такое таблица кодов символов? Это, как нетрудно догадаться, база данных. В ней пользователи могут увидеть сочетание числовых значений, при обработке которых в указанное место текста вставляется символ. Например, знак ♥ или ♫. На клавиатуре таких символов нет и быть не может.

Таблица символов помогает пользователям вставлять уникальные знаки в текстовые документы. Здесь можно увидеть кодировку элемента и способ его интерпретации.

Какими бывают

Кодировки символов — тип сочетания букв, цифр и знаков, которые после обработки операционной системой преобразовываются в знак. Они бывают разными.

Сегодня можно столкнуться с такими кодировками:

- ASCII — способ печати специальных знаков, уникальные коды которых представлены цифрами. Это самый распространенный тип кодировки. Он был разработан в 1963 году в США. Кодировка является семибитной.

- Windows-1251 — стандартная кодировка для русскоязычной «Виндовс». Она не слишком обширна и почти не пользуется спросом у юзеров.

- Unicode — 16-битная кодировка для современных операционных систем. Она служит для представления символов и букв на любом языке. Используется современными пользователями наравне с ASCII.

Теперь понятно, какими бывают кодировки. Заострим внимание на первом и последнем варианте. Они пользуются самым большим спросом у современных пользователей ПК.

Где искать в Windows

Таблицы кодов символов по умолчанию вмонтированы в операционную систему «Виндовс». С их помощью юзер сможет печатать буквы и специальные знаки в любом текстовом редакторе или документе.

Для того, чтобы найти таблицу символов в «Виндовс», нужно:

- Открыть пункт меню «Пуск».

- Развернуть раздел «Все программы».

- Выбрать папку «Стандартные»

- Кликнуть по надписи «Служебные».

- Заглянуть в приложение «Таблица символов».

Дело сделано. Теперь можно изучить все возможные знаки, которые только могут восприниматься операционной системой. Если дважды кликнуть по миниатюре того или иного символа, а затем щелкнуть по кнопке «Скопировать», соответствующий знак будет перенесен в буфер обмена. Из него можно выгрузить данные в текстовый документ.

Важно: в нижней части окна справа можно увидеть сочетание клавиш для быстрой печати выбранного элемента, а слева — «Юникод» для набора в тексте.

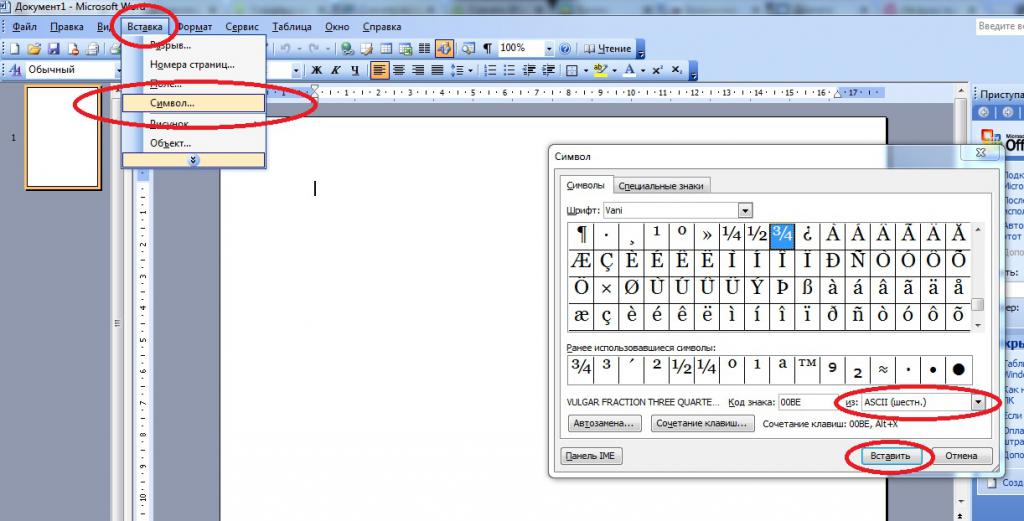

В MS Word

Таблицу кодов символов можно найти даже в текстовых редакторах. Рассмотрим алгоритм действий в MS Word. Это наиболее популярная и распространенная утилита для работы с документами в «Виндовс».

Открытие таблицы кодов символов осуществляется так:

- Зайти в Word на компьютере. Можно открыть как пустой документ, так и с текстом.

- Нажать в верхней части она по пункту «Вставка». Желательно развернуть весь список опций.

- Навести курсор и щелкнуть ЛКМ по надписи «Специальный знак. «.

Вот и все. По центру экрана появится таблица символов. Здесь можно посмотреть таблицу ASCII, «Юникода» и не только. Для этого в нижней части окна в выпадающем списке нужно выбрать после надписи «из. » подходящую кодировку.

Вставка знака может осуществляться через двойной клик по элементу в таблице или путем активации кнопки «Вставить».

Способы обработки кода

Как мы уже говорили, таблица кодов символов помогает изучить цифро-алфавитный код того или иного символа. Как можно провести преобразование оных?

Как правило, «Юникод» обрабатывается следующим образом: