- W

- Languages

- NATO Phonetic Alphabet

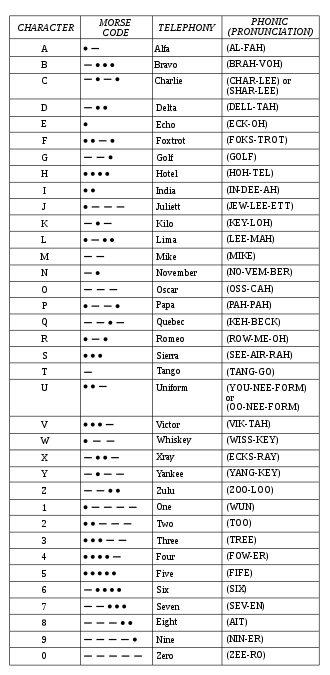

The NATO phonetic alphabet is a Spelling Alphabet, a set of words used instead of letters in oral communication (i.e. over the phone or military radio). Each word («code word») stands for its initial letter (alphabetical «symbol»). The 26 code words in the NATO phonetic alphabet are assigned to the 26 letters of the English alphabet in alphabetical order as follows:

| Symbol | Code Word | Morse Code |

Phonic (pronunciation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Alfa/Alpha | ● ▬ | AL FAH |

| B | Bravo | ▬ ● ● ● | BRAH VOH |

| C | Charlie | ▬ ● ▬ ● | CHAR LEE |

| D | Delta | ▬ ● ● | DELL TAH |

| E | Echo | .● | ECK OH |

| F | Foxtrot | ● ● ▬ ● | FOKS TROT |

| G | Golf | ▬ ▬ ● | GOLF |

| H | Hotel | ● ● ● ● | HOH TELL |

| I | India | ● ● | IN DEE AH |

| J | Juliett | ● ▬ ▬ ▬ | JEW LEE ETT |

| K | Kilo | ▬ ● ▬ | KEY LOH |

| L | Lima | ● ▬ ● ● | LEE MAH |

| M | Mike | ▬ ▬ | MIKE |

| N | November | ▬ ● | NO VEMBER |

| O | Oscar | ▬ ▬ ▬ | OSS CAH |

| P | Papa | ● ▬ ▬ ● | PAH PAH |

| Q | Quebec | ▬ ▬ ● ▬ | KEH BECK |

| R | Romeo | ● ▬ ● | ROW ME OH |

| S | Sierra | ● ● ● | SEE AIRRAH |

| T | Tango | ▬ | TANG OH |

| U | Uniform | ● ● ▬ | YOU NEE FORM |

| V | Victor | ● ● ● ▬ | VIK TAH |

| W | Whiskey | ● ▬ ▬ | WISS KEY |

| X | X-ray | ▬ ● ● ▬ | ECKS RAY |

| Y | Yankee | ▬ ▬ ● ● | YANG KEY |

| Z | Zulu | ▬ ▬ ▬ ▬ ▬ | ZOO LOO |

Notes

- The NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) Phonetic Alphabet is currently officially denoted as the International Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet (IRSA) or the ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization) phonetic alphabet or ITU (International Telecommunication Union) phonetic alphabet. Thus this alphabet can be reffered as the ICAO/ITU/NATO Phonetic Alphabet or International Phonetic Alphabet..

- This alphabet is used by the U.S. military and has also been adopted by the FAA (American Federal Aviation Administration), ANSI (American National Standards Institute), and ARRL (American Radio Relay League).

- Contrary to what its name suggests, the NATO Phonetic Alphabet is not a phonetic alphabet. Phonetic alphabets are used to indicate, through symbols or codes, what a speech sound or letter sounds like. The NATO Phonetic Alphabet is instead a spelling alphabet (also known as telephone alphabet, radio alphabet, word-spelling alphabet, or voice procedure alphabet).

- Spelling alphabets, such as the NATO Phonetic Alphabet, consists of a set of words used to stand for alphabetical letters in oral communication. These are used to avoid misunderstanding due to difficult to spell words, different pronunciations or poor line communication.

- A typical use of the NATO Phonetic Alphabet would be to spell out each letter in a word over the phone by saying, for example: «S as in Sierra» (or «S for Sierra»), «E as in Echo, Y as in Yankee, F as in Foxtrot, R as in Romeo, I as in India, E as in Echo, D as in Delta» to communicate the spelling of the name «Seyfried» correctly.

See Also:

- English Alphabet

voice recording: ICAO spelling alphabet

The (International) Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet, commonly known as the NATO phonetic alphabet, is the most widely used set of clear code words for communicating the letters of the Roman alphabet. Technically a radiotelephonic spelling alphabet, it goes by various names, including NATO spelling alphabet, ICAO phonetic alphabet and ICAO spelling alphabet. The ITU phonetic alphabet and figure code is a rarely used variant that differs in the code words for digits.

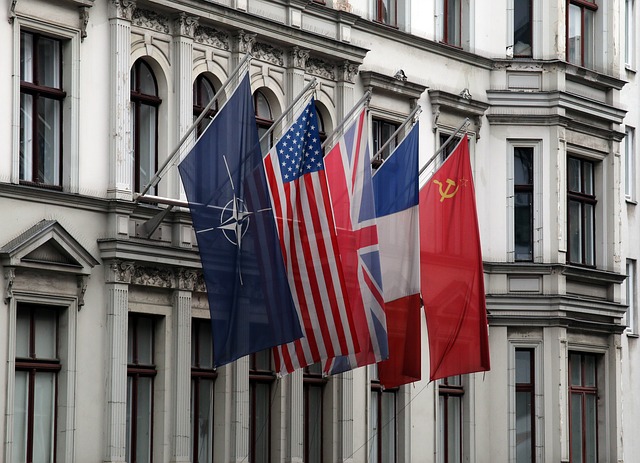

To create the code, a series of international agencies assigned 26 code words acrophonically to the letters of the Roman alphabet, with the intention of the letters and numbers being easily distinguishable from one another over radio and telephone, regardless of language barriers and connection quality. The specific code words varied, as some seemingly distinct words were found to be ineffective in real-life conditions. In 1956, NATO modified the then-current set of code words used by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO); this modification then became the international standard when it was accepted by ICAO that year and by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) a few years later.[1] The words were chosen to be accessible to speakers of English, French and Spanish.

Although spelling alphabets are commonly called «phonetic alphabets», they should not be confused with phonetic transcription systems such as the International Phonetic Alphabet.

The 26 code words are as follows (ICAO spellings): Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo, Foxtrot, Golf, Hotel, India, Juliett, Kilo, Lima, Mike, November, Oscar, Papa, Quebec, Romeo, Sierra, Tango, Uniform, Victor, Whiskey, X-ray, Yankee, Zulu.[2] «Alfa» and «Juliett» are intentionally spelled as such to avoid mispronunciation; NATO would do the same with «Xray».[3] Numbers are spoken as English digits, but with the pronunciations of three, four, five, nine, and thousand modified.[4]

The code words are fairly stable. A 1955 NATO memo stated that:

It is known that [the spelling alphabet] has been prepared only after the most exhaustive tests on a scientific basis by several nations. One of the firmest conclusions reached was that it was not practical to make an isolated change to clear confusion between one pair of letters. To change one word involves reconsideration of the whole alphabet to ensure that the change proposed to clear one confusion does not itself introduce others.[5]

International adoption[edit]

Soon after the code words were developed by ICAO (see history below), they were adopted by other national and international organizations, including the ITU, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the United States Federal Government as Federal Standard 1037C: Glossary of Telecommunications Terms[6] and its successors ANSI T1.523-2001[7] and ATIS Telecom Glossary (ATIS-0100523.2019)[8] (all three using the spellings «Alpha» and «Juliet»), the United States Department of Defense,[9] the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) (using the spelling «Xray»), the International Amateur Radio Union (IARU), the American Radio Relay League (ARRL), the Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials-International (APCO), and by many military organizations such as NATO (using the spelling «Xray») and the now-defunct Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO).

The same alphabetic code words are used by all agencies, but each agency chooses one of two different sets of numeric code words. NATO uses the regular English numeric words (zero, one, two &c., though with some differences in pronunciation), whereas the ITU (beginning on 1 April 1969)[10] and the IMO define compound numeric words (nadazero, unaone, bissotwo &c.). In practice these are used very rarely, as they are not held in common between agencies.

Usage[edit]

A spelling alphabet is used to spell parts of a message containing letters and numbers to avoid confusion, because many letters sound similar, for instance «n» and «m» or «f» and «s»; the potential for confusion increases if static or other interference is present. For instance the message «proceed to map grid DH98» could be transmitted as «proceed to map grid Delta-Hotel-Niner-Ait». Using «Delta» instead of «D» avoids confusion between «DH98» and «BH98» or «TH98». The unusual pronunciation of certain numbers was designed to reduce confusion as well.

In addition to the traditional military usage, civilian industry uses the alphabet to avoid similar problems in the transmission of messages by telephone systems. For example, it is often used in the retail industry where customer or site details are spoken by telephone (to authorize a credit agreement or confirm stock codes), although ad-hoc coding is often used in that instance. It has been used often by information technology workers to communicate serial or reference codes (which are often very long) or other specialised information by voice. Most major airlines use the alphabet to communicate passenger name records (PNRs) internally, and in some cases, with customers. It is often used in a medical context as well, to avoid confusion when transmitting information.

Several letter codes and abbreviations using the spelling alphabet have become well-known, such as Bravo Zulu (letter code BZ) for «well done»,[11] Checkpoint Charlie (Checkpoint C) in Berlin, and Zulu Time for Greenwich Mean Time or Coordinated Universal Time. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. government referred to the Viet Cong guerrillas and the group itself as VC, or Victor Charlie; the name «Charlie» became synonymous with this force.

Pronunciation of code words[edit]

The final choice of code words for the letters of the alphabet and for the digits was made after hundreds of thousands of comprehension tests involving 31 nationalities. The qualifying feature was the likelihood of a code word being understood in the context of others. For example, Football has a higher chance of being understood than Foxtrot in isolation, but Foxtrot is superior in extended communication.[12]

Pronunciations were set out by the ICAO before 1956 with advice from the governments of both the United States and United Kingdom.[13] To eliminate national variations in pronunciation, posters illustrating the pronunciation desired by ICAO are available.[14] However, there remain differences in the pronunciations published by ICAO and other agencies, and ICAO has apparently conflicting Latin-alphabet and IPA transcriptions. At least some of these differences appear to be typographic errors. In 2022 the Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN) attempted to resolve these conflicts.[15]

Just as words are spelled out as individual letters, numbers are spelled out as individual digits. That is, 17 is rendered as «one seven» and 60 as «six zero», though thousand is also used, and for whole hundreds (when the sequence 00 occurs at the end of a number), the word hundred may be used. That is, 1300 may be read as «one three zero zero» (e.g. as a transponder code) or as «one thousand three hundred» (e.g. as an altitude or distance).

The ICAO, NATO, and FAA use modifications of English digits as code words, with 3, 4, 5 and 9 being pronounced tree, fower (rhymes with lower), fife and niner. The digit 3 is specified as tree so that it is not pronounced sri; the long pronunciation of 4 (still found in some English dialects) keeps it somewhat distinct from for; 5 is pronounced with a second «f» because the normal pronunciation with a «v» is easily confused with «fire» (a command to shoot); and 9 has an extra «r» to keep it distinct from the German word nein «no». (Prior to 1956, three and five had been pronounced with the English consonants, but as two syllables.)

For direction presented as the hour-hand position on a clock, «ten», «eleven» and «twelve» may be used with «o’clock».[14]: 5–7

The ITU and IMO, however, specify a different set of code words. These are compounds of the ICAO words with a Latinesque prefix.[16]

The IMO’s GMDSS procedures permits the use of either set of code words.[16]

Tables[edit]

There are two IPA transcriptions of the letter names, from the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN). Both authorities indicate that a non-rhotic pronunciation is standard. That of the ICAO, first published in 1950 and reprinted many times without correction (vd. the error in ‘golf’), uses a large number of vowels. For instance, it has six low/central vowels: [æ a aː ɑ ɑː ə]. The DIN consolidated all six into the single low-central vowel [a]. The DIN vowels are partly predictable, with [ɪ ɛ ɔ] in closed syllables and [i e/ei̯ o] in open syllables apart from echo and sierra, which have [ɛ] as in English, German and Italian. The DIN also reduced the number of stressed syllables in bravo and x-ray, consistent with the ICAO English respellings of those words and with the NATO change of spelling of x-ray to xray so that people would know to pronounce it as a single word.

| Symbol | Code word | DIN 5009 (2022) IPA[15] |

ICAO (1950)[14] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | respelling | |||

| A | Alfa [sic] | ˈalfa | ˈælfa | AL fah |

| B | Bravo | ˈbravo | ˈbraːˈvo [sic] | BRAH voh |

| C | Charlie | ˈtʃali or ˈʃali | ˈtʃɑːli or ˈʃɑːli | CHAR lee or SHAR lee |

| D | Delta | ˈdɛlta | ˈdeltɑ | DELL tah |

| E | Echo | ˈɛko | ˈeko | ECK oh |

| F | Foxtrot | ˈfɔkstrɔt | ˈfɔkstrɔt | FOKS trot |

| G | Golf | ˈɡɔlf | ɡʌlf [sic] | golf |

| H | Hotel | hoˈtɛl | hoːˈtel | ho TELL |

| I | India | ˈɪndia | ˈindi.ɑ | IN dee ah |

| J | Juliett [sic] | ˈdʒuliˈɛt | ˈdʒuːli.ˈet | JEW lee ETT |

| K | Kilo | ˈkilo | ˈkiːlo | KEY loh |

| L | Lima | ˈlima | ˈliːmɑ | LEE mah |

| M | Mike | ˈmai̯k | mɑik | mike |

| N | November | noˈvɛmba | noˈvembə | no VEM ber |

| O | Oscar | ˈɔska | ˈɔskɑ | OSS cah |

| P | Papa | paˈpa | pəˈpɑ | pah PAH |

| Q | Quebec | keˈbɛk [sic] | keˈbek | keh BECK |

| R | Romeo | ˈromio | ˈroːmi.o | ROW me oh |

| S | Sierra | siˈɛra | siˈerɑ | see AIR rah |

| T | Tango | ˈtaŋɡo | ˈtænɡo | TANG go |

| U | Uniform | ˈjunifɔm or ˈunifɔm | ˈjuːnifɔːm or ˈuːnifɔrm [sic] | YOU nee form or OO nee form |

| V | Victor | ˈvɪkta | ˈviktɑ | VIK tah |

| W | Whiskey | ˈwɪski | ˈwiski | WISS key |

| X | Xray, x-ray | ˈɛksrei̯ | ˈeksˈrei [sic] | ECKS ray |

| Y | Yankee | ˈjaŋki | ˈjænki | YANG key |

| Z | Zulu | ˈzulu | ˈzuːluː | ZOO loo |

There is no authoritative IPA transcription of the digits. However, there are respellings into both English and French, which can be compared to clarify some of the ambiguities and inconsistencies.

| Symbol | Code word | Respellings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICAO[14] (English) |

SIA[17] (French) |

CCEB 2016[18] | FAA[19] | ITU-R 2007 (WRC-07)[20] IMO (English)[21] |

IMO (French)[21] |

U.S. Navy 1957[22] |

U.S. Army[23] | ||

| 1 | One, unaone | WUN | OUANN [ˈwan] | wun | wun | OO-NAH-WUN | OUNA-OUANN | wun | wun, won (USMC)[24] |

| 2 | Two, bissotwo | TOO /ˈtuː/ | TOU [ˈtu] | too | too | BEES-SOH-TOO | BIS-SO-TOU | too | too |

| 3 | Three, terrathree | TREE /ˈtriː/ | TRI [ˈtri] | tree | tree | TAY-RAH-TREE | TÉ-RA-TRI | thuh-ree | tree |

| 4 | Four, kartefour | FOW-er /ˈfoʊ.ə/ | FO eur [ˈfo.ør] | FOW-er | fow-er | KAR-TAY-FOWER | KAR-TÉ-FO-EUR | fo-wer | fow-er |

| 5 | Five, pantafive | FIFE /ˈfaɪf/ | FA ÏF [sic] [ˈfaif] | fife | fife | PAN-TAH-FIVE | PANN-TA-FAIF | fi-yiv | fife |

| 6 | Six, soxisix | SIX /ˈsɪks/ | SIKS [ˈsiks] | six | six | SOK-SEE-SIX | SO-XI-SICKS | six | six |

| 7 | Seven, setteseven | SEV-en /ˈsɛv(ə)n/ | SÈV n [ˈsɛv.n] | SEV-en | sev-en | SAY-TAY-SEVEN | SÉT-TÉ-SEV’N [sic] | seven | sev-en |

| 8 | Eight, oktoeight | AIT /ˈeɪt/ | EÏT [ˈeit] | ait | ait | OK-TOH-AIT | OK-TO-EIT | ate | ait |

| 9 | Nine, novenine[25] | NIN-er /ˈnaɪnə/ | NAÏ neu [ˈnainø] | NINE-er | nin-er | NO-VAY-NINER | NO-VÉ-NAI-NEU | niner | nin-er |

| 0 | Zero, nadazero | ZE-RO[26] /ˈziːˈroʊ/ | ZI RO [ˈziˈro] | ZE-ro | ze-ro / zee-ro | NAH-DAH-ZAY-ROH[27][28] | NA-DA-ZE-RO[27][28] | zero | ze-ro |

| 00 | Hundred | HUN-dred /ˈhʌndrɛd/ | HUN-dred [ˈœ̃drɛd] | (zero zero) | (hundred) | hun-dred | |||

| 000 | Thousand | TOU-SAND[26] /ˈtaʊˈzænd/ | TAOU ZEND [ˈtauˈzɑ̃d] | (zero zero zero) | (thousand) | thow-zand | tou-sand | ||

| (decimal point) | Decimal, (FAA) point | DAY-SEE-MAL[26] /ˈdeɪˈsiːˈmæl/ | DÈ SI MAL [ˈdeˈsiˈmal] | (decimal) | (point) | DAY-SEE-MAL | DÉ-SI-MAL |

CCEB code words for punctuation include:

| . | stop (when not a decimal point) |

| , | comma (when not a decimal point) |

| — | hyphen (FAA ‘dash’) |

| / | slant |

| ( | brackets on |

| ) | brackets off |

Others are: ‘colon’, ‘semi-colon’, ‘exclamation mark’, ‘question mark’, ‘apostrophe’, ‘quote’ and ‘unquote’.[18]

History[edit]

Prior to World War I and the development and widespread adoption of two-way radio that supported voice, telephone spelling alphabets were developed to improve communication on low-quality and long-distance telephone circuits.

The first non-military internationally recognized spelling alphabet was adopted by the CCIR (predecessor of the ITU) during 1927. The experience gained with that alphabet resulted in several changes being made during 1932 by the ITU. The resulting alphabet was adopted by the International Commission for Air Navigation, the predecessor of the ICAO, and was used for civil aviation until World War II.[13] It continued to be used by the IMO until 1965.

Throughout World War II, many nations used their own versions of a spelling alphabet. The U.S. adopted the Joint Army/Navy radiotelephony alphabet during 1941 to standardize systems among all branches of its armed forces. The U.S. alphabet became known as Able Baker after the words for A and B. The Royal Air Force adopted one similar to the United States one during World War II as well. Other British forces adopted the RAF radio alphabet, which is similar to the phonetic alphabet used by the Royal Navy during World War I. At least two of the terms are sometimes still used by UK civilians to spell words over the phone, namely F for Freddie and S for Sugar.

To enable the U.S., UK, and Australian armed forces to communicate during joint operations, in 1943 the CCB (Combined Communications Board; the combination of US and UK upper military commands) modified the U.S. military’s Joint Army/Navy alphabet for use by all three nations, with the result being called the US-UK spelling alphabet. It was defined in one or more of CCBP-1: Combined Amphibious Communications Instructions, CCBP3: Combined Radiotelephone (R/T) Procedure, and CCBP-7: Combined Communication Instructions. The CCB alphabet itself was based on the U.S. Joint Army/Navy spelling alphabet. The CCBP (Combined Communications Board Publications) documents contain material formerly published in U.S. Army Field Manuals in the 24-series. Several of these documents had revisions, and were renamed. For instance, CCBP3-2 was the second edition of CCBP3.

During World War II, the U.S. military conducted significant research into spelling alphabets. Major F. D. Handy, directorate of Communications in the Army Air Force (and a member of the working committee of the Combined Communications Board), enlisted the help of Harvard University’s Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory, asking them to determine the most successful word for each letter when using «military interphones in the intense noise encountered in modern warfare.». He included lists from the US, Royal Air Force, Royal Navy, British Army, AT&T, Western Union, RCA Communications, and that of the International Telecommunications Convention. According to a report on the subject:

The results showed that many of the words in the military lists had a low level of intelligibility, but that most of the deficiencies could be remedied by the judicious selection of words from the commercial codes and those tested by the laboratory. In a few instances where none of the 250 words could be regarded as especially satisfactory, it was believed possible to discover suitable replacements. Other words were tested and the most intelligible ones were compared with the more desirable lists. A final NDRC list was assembled and recommended to the CCB.[29]

After World War II, with many aircraft and ground personnel from the allied armed forces, «Able Baker» was officially adopted for use in international aviation. During the 1946 Second Session of the ICAO Communications Division, the organization adopted the so-called «Able Baker» alphabet[12] that was the 1943 US–UK spelling alphabet. However, many sounds were unique to English, so an alternative «Ana Brazil» alphabet was used in Latin America. In spite of this, International Air Transport Association (IATA), recognizing the need for a single universal alphabet, presented a draft alphabet to the ICAO during 1947 that had sounds common to English, French, Spanish and Portuguese.

From 1948 to 1949, Jean-Paul Vinay, a professor of linguistics at the Université de Montréal worked closely with the ICAO to research and develop a new spelling alphabet.[30][12] The directions of ICAO were that «To be considered, a word must:

- Be a live word in each of the three working languages.

- Be easily pronounced and recognized by airmen of all languages.

- Have good radio transmission and readability characteristics.

- Have a similar spelling in at least English, French, and Spanish, and the initial letter must be the letter the word identifies.

- Be free from any association with objectionable meanings.»[29]

After further study and modification by each approving body, the revised alphabet was adopted on 1 November 1951, to become effective on 1 April 1952 for civil aviation (but it may not have been adopted by any military).[13]

Problems were soon found with this list. Some users believed that they were so severe that they reverted to the old «Able Baker» alphabet. Confusion among words like Delta and Extra, and between Nectar and Victor, or the poor intelligibility of other words during poor receiving conditions were the main problems. Later in 1952, ICAO decided to revisit the alphabet and their research. To identify the deficiencies of the new alphabet, testing was conducted among speakers from 31 nations, principally by the governments of the United Kingdom and the United States. In the United States, the research was conducted by the USAF-directed Operational Applications Laboratory (AFCRC, ARDC), to monitor a project with the Research Foundation of Ohio State University. Among the more interesting of the research findings was that «higher noise levels do not create confusion, but do intensify those confusions already inherent between the words in question».[29]

By early 1956 the ICAO was nearly complete with this research, and published the new official phonetic alphabet in order to account for discrepancies that might arise in communications as a result of multiple alphabet naming systems coexisting in different places and organizations. NATO was in the process of adopting the ICAO spelling alphabet, and apparently felt enough urgency that it adopted the proposed new alphabet with changes based on NATO’s own research, to become effective on 1 January 1956,[31] but quickly issued a new directive on 1 March 1956[32] adopting the now official ICAO spelling alphabet, which had changed by one word (November) from NATO’s earlier request to ICAO to modify a few words based on U.S. Air Force research.

After all of the above study, only the five words representing the letters C, M, N, U, and X were replaced. The ICAO sent a recording of the new Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet to all member states in November 1955.[12] The final version given in the table above was implemented by the ICAO on 1 March 1956,[13] and the ITU adopted it no later than 1959 when they mandated its usage via their official publication, Radio Regulations.[33] Because the ITU governs all international radio communications, it was also adopted by most radio operators, whether military, civilian, or amateur. It was finally adopted by the IMO in 1965.

During 1947 the ITU adopted the compound Latinate prefix-number words (Nadazero, Unaone, etc.), later adopted by the IMO during 1965.[citation needed]

- Nadazero — from Spanish or Portuguese nada + NATO/ICAO zero

- Unaone — generic Romance una, from Latin ūna + NATO/ICAO one

- Bissotwo — from Latin bis + NATO/ICAO two. (1959 ITU proposals bis and too)[34]

- Terrathree — from Italian terzo + NATO/ICAO three («tree») (1959 ITU proposals ter and tree)

- Kartefour — from French quatre (Latin quartus) + NATO/ICAO four («fow-er») (1959 ITU proposals quarto and fow-er)

- Pantafive — from French penta- + NATO/ICAO five («fife») (From 1959 ITU proposals penta and fife)

- Soxisix — from French soix + NATO/ICAO six (1959 ITU proposals were saxo and six)

- Setteseven — from Italian sette + NATO/ICAO seven (1959 ITU proposals sette and sev-en)

- Oktoeight — generic Romance octo-, from Latin octō + NATO/ICAO eight (1959 ITU proposals octo and ait)

- Novenine — from Italian nove + NATO/ICAO nine («niner») (1959 ITU proposals were nona and niner)

In the official version of the alphabet,[4] two spellings deviate from the English norm: Alfa and Juliett. Alfa is spelled with an f as it is in most European languages because the spelling Alpha may not be pronounced properly by native speakers of some languages – who may not know that ph should be pronounced as f. The spelling Juliett is used rather than Juliet for the benefit of French speakers, because they may otherwise treat a single final t as silent. For similar reasons, Charlie and Uniform have alternative pronunciations where the ch is pronounced «sh» and the u is pronounced «oo». Early on, the NATO alliance changed X-ray to Xray in its version of the alphabet to ensure that it would be pronounced as one word rather than as two,[35] while the global organization ICAO keeps the spelling X-ray.

The alphabet is defined by various international conventions on radio, including:

- Universal Electrical Communications Union (UECU), Washington, D.C., December 1920[36]

- International Radiotelegraph Convention, Washington, 1927 (which created the CCIR)[37]

- General Radiocommunication and Additional Regulations (Madrid, 1932)[38]

- Instructions for the International Telephone Service, 1932 (ITU-T E.141; withdrawn in 1993)

- General Radiocommunication Regulations and Additional Radiocommunication Regulations (Cairo, 1938)[39]

- Radio Regulations and Additional Radio Regulations (Atlantic City, 1947),[40] where «it was decided that the International Civil Aviation Organization and other international aeronautical organizations would assume the responsibility for procedures and regulations related to aeronautical communication. However, ITU would continue to maintain general procedures regarding distress signals.»

- 1959 Administrative Radio Conference (Geneva, 1959)[41]

- International Telecommunication Union, Radio

- Final Acts of WARC-79 (Geneva, 1979).[42] Here the alphabet was formally named «Phonetic Alphabet and Figure Code».

- International Code of Signals for Visual, Sound, and Radio Communications, United States Edition, 1969 (revised 2003)[43]

Tables[edit]

| Letter | 1920 UECU[36] | 1927 (Washington, D.C.) International Radiotelegraph Convention (CCIR)[37] | 1932 General Radiocommunication and Additional Regulations (CCIR/ICAN)[44][45] | 1938 (Cairo) International Radiocommunication Conference code words[39] | 1947 (Atlantic City) International Radio Conference[46] | 1947 ICAO (from 1943 US–UK)[47]

[48][45] |

1947 ICAO alphabet (from ARRL[citation needed])[49] | 1947 ICAO Latin America/Caribbean[29] | 1947 IATA proposal to ICAO[29] | 1949 ICAO code words[29] | 1951 ICAO code words[30] | 1956 ICAO final code words[14] | 1959 (Geneva) ITU Administrative Radio Conference code words[41] | 1959 ITU pronunciations[41] | 2008 – present ICAO code words[14] | 2008 – present ICAO pronunciations[14] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Argentine | Amsterdam | Amsterdam | Amsterdam | Amsterdam | ABLE | ADAM | ANA | ALPHA | Alfa | Alfa | Alfa | Alfa | AL FAH | Alfa | AL FAH |

| B | Brussels | Baltimore | Baltimore | Baltimore | Baltimore | BAKER | BAKER | BRAZIL | BETA | Beta | Bravo | Bravo | Bravo | BRAH VOH | Bravo | BRAH VOH |

| C | Canada | Canada | Casablanca | Casablanca | Casablanca | CHARLIE | CHARLIE | COCO | CHARLIE | Coca | Coca | Charlie | Charlie | CHAR LEE or SHAR LEE | Charlie | CHAR LEE or SHAR LEE |

| D | Damascus | Denmark | Danemark | Danemark | Danemark | DOG | DAVID | DADO | DELTA | Delta | Delta | Delta | Delta | DELL TAH | Delta | DELL TAH |

| E | Ecuador | Eddystone | Edison | Edison | Edison | EASY | EDWARD | ELSA | EDWARD | Echo | Echo | Echo | Echo | ECK OH | Echo | ECK OH |

| F | France | Francisco | Florida | Florida | Florida | FOX | FREDDIE | FIESTA | FOX | Foxtrot | Foxtrot | Foxtrot | Foxtrot | FOKS TROT | Foxtrot | FOKS TROT |

| G | Greece | Gibraltar | Gallipoli | Gallipoli | Gallipoli | GEORGE | GEORGE | GATO | GRAMMA | Golf | Gold | Golf | Golf | GOLF | Golf | GOLF |

| H | Hanover | Hanover | Havana | Havana | Havana | HOW | HARRY | HOMBRE | HAVANA | Hotel | Hotel | Hotel | Hotel | HOH TELL | Hotel | HO TELL |

| I | Italy | Italy | Italia | Italia | Italia | ITEM | IDA | INDIA | ITALY | India | India | India | India | IN DEE AH | India | IN DEE AH |

| J | Japan | Jerusalem | Jérusalem | Jérusalem | Jerusalem | JIG | JOHN | JULIO | JUPITER | Julietta | Juliett | Juliett | Juliett | JEW LEE ETT | Juliett | JEW LEE ETT |

| K | Khartoum | Kimberley | Kilogramme | Kilogramme | Kilogramme | KING | KING | KILO | KILO | Kilo | Kilo | Kilo | Kilo | KEY LOH | Kilo | KEY LOH |

| L | Lima | Liverpool | Liverpool | Liverpool | Liverpool | LOVE | LEWIS | LUIS | LITER | Lima | Lima | Lima | Lima | LEE MAH | Lima | LEE MAH |

| M | Madrid | Madagascar | Madagascar | Madagascar | Madagascar | MIKE | MARY | MAMA | MAESTRO | Metro | Metro | Mike | Mike | MIKE | Mike | MIKE |

| N | Nancy | Neufchatel | New York | New-York | New York | NAN | NANCY | NORMA | NORMA | Nectar | Nectar | November | November | NO VEM BER | November | NO VEM BER |

| O | Ostend | Ontario | Oslo | Oslo | Oslo | OBOE | OTTO | OPERA | OPERA | Oscar | Oscar | Oscar | Oscar | OSS CAH | Oscar | OSS CAH |

| P | Paris | Portugal | Paris | Paris | Paris | PETER | PETER | PERU | PERU | Polka | Papa | Papa | Papa | PAH PAH | Papa | PAH PAH |

| Q | Quebec | Quebec | Québec | Québec | Quebec | QUEEN | QUEEN | QUEBEC | QUEBEC | Quebec | Quebec | Quebec | Quebec | KEH BECK | Quebec | KEH BECK |

| R | Rome | Rivoli | Roma | Roma | Roma | ROGER | ROBERT | ROSA | ROGER | Romeo | Romeo | Romeo | Romeo | ROW ME OH | Romeo | ROW ME OH |

| S | Sardinia | Santiago | Santiago | Santiago | Santiago | SUGAR | SUSAN | SARA | SANTA | Sierra | Sierra | Sierra | Sierra | SEE AIR RAH | Sierra | SEE AIR RAH |

| T | Tokio | Tokio | Tripoli | Tripoli | Tripoli | TARE | THOMAS | TOMAS | THOMAS | Tango | Tango | Tango | Tango | TANG GO | Tango | TANG GO |

| U | Uruguay | Uruguay | Upsala | Upsala | Upsala | UNCLE | UNION | URUGUAY | URSULA | Union | Union | Uniform | Uniform | YOU NEE FORM or OO NEE FORM |

Uniform | YOU NEE FORM or OO NEE FORM |

| V | Victoria | Victoria | Valencia | Valencia | Valencia | VICTOR | VICTOR | VICTOR | VICTOR | Victor | Victor | Victor | Victor | VIK TAH | Victor | VIK TAH |

| W | Washington | Washington | Washington | Washington | Washington | WILLIAM | WILLIAM | WHISKEY | WHISKEY | Whiskey | Whiskey | Whiskey | Whiskey | WISS KEY | Whiskey | WISS KEY |

| X | Xaintrie | Xantippe | Xanthippe | Xanthippe | Xanthippe | XRAY | X-RAY | EQUIS | X-RAY | eXtra | eXtra | X-ray | X-ray | ECKS RAY | X-ray | ECKS RAY |

| Y | Yokohama | Yokohama | Yokohama | Yokohama | Yokohama | YOKE | YOUNG | YOLANDA | YORK | Yankey | Yankee | Yankee | Yankee | YANG KEY | Yankee | YANG KEY |

| Z | Zanzibar | Zululand | Zürich | Zurich | Zurich | ZEBRA | ZEBRA | ZETA | ? | Zebra | Zulu | Zulu | Zulu | ZOO LOO | Zulu | ZOO LOO |

| 0 | Jérusalem[Note 1] | Jerusalem[Note 1] | Zero | Juliett[Note 1] | (alt. proposals: ZE-RO, ZERO) | zero | ZE-RO | |||||||||

| 1 | Amsterdam[Note 1] | Amsterdam[Note 1] | Wun | Alfa[Note 1] | (alt. proposals: WUN, WUN) | one | WUN | |||||||||

| 2 | Baltimore[Note 1] | Baltimore[Note 1] | Too | Bravo[Note 1] | (alt. proposals: TOO, BIS) | two | TOO | |||||||||

| 3 | Casablanca[Note 1] | Casablanca[Note 1] | Thuh-ree | Charlie[Note 1] | (alt. proposals: TREE, TER) | three | TREE | |||||||||

| 4 | Danemark[Note 1] | Danemark[Note 1] | Fo-wer | Delta[Note 1] | (alt. proposals: FOW-ER, QUARTO) | four | FOW-er | |||||||||

| 5 | Edison[Note 1] | Edison[Note 1] | Fi-yiv | Echo[Note 1] | (alt. proposals: FIFE, PENTA) | five | FIFE | |||||||||

| 6 | Florida[Note 1] | Florida[Note 1] | Six | Foxtrot[Note 1] | (alt. proposals: SIX, SAXO) | six | SIX | |||||||||

| 7 | Gallipoli[Note 1] | Gallipoli[Note 1] | Seven | Golf[Note 1] | (alt. proposals: SEV-EN, SETTE) | seven | SEV-en | |||||||||

| 8 | Havana[Note 1] | Havana[Note 1] | Ate | Hotel[Note 1] | (alt. proposals: AIT, OCTO) | eight | AIT | |||||||||

| 9 | Italia[Note 1] | Italia[Note 1] | Niner | India[Note 1] | (alt. proposals: NIN-ER, NONA) | nine | NIN-er | |||||||||

| . (decimal point) | (proposals: DAY-SEE-MAL, DECIMAL) | decimal | DAY-SEE-MAL | |||||||||||||

| Hundred | hundred | HUN-dred | ||||||||||||||

| Thousand | (proposals: TOUS-AND, –) | thousand | TOU-SAND | |||||||||||||

| , | Kilogramme[Note 1] | Kilogramme[Note 1] | Kilo[Note 1] | |||||||||||||

| / (fraction bar) | Liverpool[Note 1] | Liverpool[Note 1] | Lima[Note 1] | |||||||||||||

| (break signal) | Madagascar[Note 1] | Madagascar[Note 1] | Mike[Note 1] | |||||||||||||

| . (punctuation) | New-York[Note 1] | New York[Note 1] | November[Note 1] |

For the 1938 and 1947 phonetics, each transmission of figures is preceded and followed by the words «as a number» spoken twice.

The ITU adopted the IMO phonetic spelling alphabet in 1959,[50] and in 1969 specified that it be «for application in the maritime mobile service only».[51]

Pronunciation was not defined prior to 1959. For the post-1959 phonetics, the underlined syllable of each letter word should be emphasized, and each syllable of the code words for the post-1969 figures should be equally emphasized.

International aviation[edit]

The Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet is used by the International Civil Aviation Organization for international aircraft communications.[4][14]

| Letter | 1932 General Radiocommunication and Additional Regulations (CCIR/ICAN)[44][45] | 1946 ICAO Second Session of the Communications Division (same as Joint Army/Navy)[29] | 1947 ICAO (same as 1943 US-UK)[47]

[48][45] |

1947 ICAO alphabet (adopted exactly from ARRL[49] | 1947 ICAO Latin America/Caribbean[29] | 1949 ICAO code words[29] | 1951 ICAO code words[30] | 1956 – present ICAO code words[14] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Amsterdam | Able | ABLE | ADAM | ANA | Alfa | Alfa | Alfa |

| B | Baltimore | Baker | BAKER | BAKER | BRAZIL | Beta | Bravo | Bravo |

| C | Casablanca | Charlie | CHARLIE | CHARLIE | COCO | Coca | Coca | Charlie |

| D | Danemark | Dog | DOG | DAVID | DADO | Delta | Delta | Delta |

| E | Edison | Easy | EASY | EDWARD | ELSA | Echo | Echo | Echo |

| F | Florida | Fox | FOX | FREDDIE | FIESTA | Foxtrot | Foxtrot | Foxtrot |

| G | Gallipoli | George | GEORGE | GEORGE | GATO | Golf | Gold | Golf |

| H | Havana | How | HOW | HARRY | HOMBRE | Hotel | Hotel | Hotel |

| I | Italia | Item | ITEM | IDA | INDIA | India | India | India |

| J | Jérusalem | Jig | JIG | JOHN | JULIO | Julietta | Juliett | Juliett |

| K | Kilogramme | King | KING | KING | KILO | Kilo | Kilo | Kilo |

| L | Liverpool | Love | LOVE | LEWIS | LUIS | Lima | Lima | Lima |

| M | Madagascar | Mike | MIKE | MARY | MAMA | Metro | Metro | Mike |

| N | New York | Nan (later Nickel) | NAN | NANCY | NORMA | Nectar | Nectar | November |

| O | Oslo | Oboe | OBOE | OTTO | OPERA | Oscar | Oscar | Oscar |

| P | Paris | Peter | PETER | PETER | PERU | Polka | Papa | Papa |

| Q | Québec | Queen | QUEEN | QUEEN | QUEBEC | Quebec | Quebec | Quebec |

| R | Roma | Roger | ROGER | ROBERT | ROSA | Romeo | Romeo | Romeo |

| S | Santiago | Sail/Sugar | SUGAR | SUSAN | SARA | Sierra | Sierra | Sierra |

| T | Tripoli | Tare | TARE | THOMAS | TOMAS | Tango | Tango | Tango |

| U | Upsala | Uncle | UNCLE | UNION | URUGUAY | Union | Union | Uniform |

| V | Valencia | Victor | VICTOR | VICTOR | VICTOR | Victor | Victor | Victor |

| W | Washington | William | WILLIAM | WILLIAM | WHISKEY | Whiskey | Whiskey | Whisky |

| X | Xanthippe | X-ray | XRAY | X-RAY | EQUIS | X-RAY | eXtra | X-ray |

| Y | Yokohama | Yoke | YOKE | YOUNG | YOLANDA | Yankey | Yankee | Yankee |

| Z | Zürich | Zebra | ZEBRA | ZEBRA | ZETA | Zebra | Zulu | Zulu |

| 0 | Zero | Zero | Zero | |||||

| 1 | One | Wun | One | |||||

| 2 | Two | Too | Two | |||||

| 3 | Three | Thuh-ree | Three | |||||

| 4 | Four | Fo-wer | Four | |||||

| 5 | Five | Fi-yiv | Five | |||||

| 6 | Six | Six | Six | |||||

| 7 | Seven | Seven | Seven | |||||

| 8 | Eight | Ate | Eight | |||||

| 9 | Nine | Niner | Niner | |||||

| . | Decimal | |||||||

| 100 | Hundred | |||||||

| 1000 | Thousand |

International maritime mobile service[edit]

The ITU-R Radiotelephony Alphabet is used by the International Maritime Organization for international marine communications.

| Letter | 1932–1965 IMO code words[52] | 1965 – present (WRC-03) IMO code words[53] | 1967 WARC code words[54] | 2000 – present IMO SMCP pronunciations[53] | 1967 WARC pronunciations[54] | 2007 – present ITU-R pronunciations[20] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Amsterdam | Alfa | Alfa | Alfa | AL FAH | AL FAH |

| B | Baltimore | Bravo | Bravo | Bravo | BRAH VOH | BRAH VOH |

| C | Casablanca | Charlie | Charlie | Charlie | CHAR LEE or SHAR LEE | CHAR LEE or SHAR LEE |

| D | Danemark | Delta | Delta | Delta | DELL TAH | DELL TAH |

| E | Edison | Echo | Echo | Echo | ECK OH | ECK OH |

| F | Florida | Foxtrot | Foxtrot | Foxtrot | FOKS TROT | FOKS TROT |

| G | Gallipoli | Golf | Golf | Golf | GOLF | GOLF |

| H | Havana | Hotel | Hotel | Hotel | HOH TELL | HOH TELL |

| I | Italia | India | India | India | IN DEE AH | IN DEE AH |

| J | Jérusalem | Juliett | Juliett | Juliet | JEW LEE ETT | JEW LEE ETT |

| K | Kilogramme | Kilo | Kilo | Kilo | KEY LOH | KEY LOH |

| L | Liverpool | Lima | Lima | Lima | LEE MAH | LEE MAH |

| M | Madagascar | Mike | Mike | Mike | MIKE | MIKE |

| N | New-York | November | November | November | NO VEM BER | NO VEM BER |

| O | Oslo | Oscar | Oscar | Oscar | OSS CAH | OSS CAH |

| P | Paris | Papa | Papa | Papa | PAH PAH | PAH PAH |

| Q | Québec | Quebec | Quebec | Quebec | KEH BECK | KEH BECK |

| R | Roma | Romeo | Romeo | Romeo | ROW ME OH | ROW ME OH |

| S | Santiago | Sierra | Sierra | Sierra | SEE AIR RAH | SEE AIR RAH |

| T | Tripoli | Tango | Tango | Tango | TANG GO | TANG GO |

| U | Upsala | Uniform | Uniform | Uniform | YOU NEE FORM or OO NEE FORM |

YOU NEE FORM or OO NEE FORM |

| V | Valencia | Victor | Victor | Victor | VIK TAH | VIK TAH |

| W | Washington | Whisky | Whisky | Whisky | WISS KEY | WISS KEY |

| X | Xanthippe | X-ray | X-ray | X-ray | ECKS RAY | ECKS RAY |

| Y | Yokohama | Yankee | Yankee | Yankee | YANG KEY | YANG KEY |

| Z | Zurich | Zulu | Zulu | Zulu | ZOO LOO | ZOO LOO |

| 0 | Zero | ZEERO | NADAZERO | ZEERO | NAH-DAH-ZAY-ROH | NAH-DAH-ZAY-ROH |

| 1 | One | WUN | UNAONE | WUN | OO-NAH-WUN | OO-NAH-WUN |

| 2 | Two | TOO | BISSOTWO | TOO | BEES-SOH-TOO | BEES-SOH-TOO |

| 3 | Three | TREE | TERRATHREE | TREE | TAY-RAH-TREE | TAY-RAH-TREE |

| 4 | Four | FOWER | KARTEFOUR | FOWER | KAR-TAY-FOWER | KAR-TAY-FOWER |

| 5 | Five | FIFE | PANTAFIVE | FIFE | PAN-TAH-FIVE | PAN-TAH-FIVE |

| 6 | Six | SIX | SOXISIX | SIX | SOK-SEE-SIX | SOK-SEE-SIX |

| 7 | Seven | SEVEN | SETTESEVEN | SEVEN | SAY-TAY-SEVEN | SAY-TAY-SEVEN |

| 8 | Eight | AIT | OKTOEIGHT | AIT | OK-TOH-AIT | OK-TOH-AIT |

| 9 | Nine | NINER | NOVENINE | NINER | NO-VAY-NINER | NO-VAY-NINER |

| . | DECIMAL | DAY-SEE-MAL | DAY-SEE-MAL | |||

| . | Full stop | STOP | STOP | STOP | ||

| , | Comma | |||||

| Break signal | ||||||

| ⁄ | Fraction bar | |||||

| 1000 | TOUSAND | TOUSAND |

Variants[edit]

Since ‘Nectar’ was changed to ‘November’ in 1956, the code has been mostly stable. However, there is occasional regional substitution of a few code words, such as replacing them with earlier variants, because of local taboos or confusing them with local terminology.[citation needed]

- As of 2013, it was reported that «Delta» was often replaced by «David» or «Dixie» at Atlanta International Airport, where Delta Air Lines is based, because «Delta» is also the airline’s callsign.[55] Air traffic control once referred to Taxiway D at the same airport as «Taxiway Dixie», though this practice was officially discontinued in 2020.[56][57][58]

See also[edit]

- International Code of Signals

- Spelling alphabet

- Allied military phonetic spelling alphabets

- APCO radiotelephony spelling alphabet (used by some US police departments)

- Language-specific spelling alphabets

- Finnish Armed Forces radio alphabet

- German spelling alphabet

- Greek spelling alphabet

- Japanese radiotelephony alphabet

- Korean spelling alphabet

- Russian spelling alphabet

- Swedish Armed Forces radio alphabet

- Radiotelephony procedure

- Procedure word

- Brevity code

- Ten-code

- Q code

- List of military time zones

- PGP word list

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap Each sequence of figures is both preceded and followed by «as a number» (or, for punctuation only) «as a mark», spoken twice.

References[edit]

- ^ «The NATO phonetic alphabet – Alfa, Bravo, Charlie…» NATO.

- ^ In print, these code words are commonly capitalized for emphasis, or written in all caps (CCEB 2016).

- ^ «NATO phonetic alphabet, codes & signals» (PDF). North Atlantic Treaty Organization. 15 January 2018.

- ^ a b c «Alphabet — Radiotelephony». International Civil Aviation Organization. n.d. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ «SGM-675-55: Phonetic Alphabet for NATO Use» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2018.

- ^ «Definition: phonetic alphabet». Federal Standard 1037C: Glossary of Telecommunication Terms. National Communications System. 23 August 1996. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ «T1.523-2001 — Telecom Glossary 2000». Washington, DC: American National Standards Institute. 2001. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ «ATIS Telecom Glossary (ATIS-0100523.2019)». Washington, DC: Alliance for Telecommunications Industry Solutions. 2019. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ «Joint Publication 1-02: Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms» (PDF). p. 414, PDF page 421. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2012.

- ^ ITU 1967, pp. 177–179.

- ^ «Where does the term «Bravo Zulu» originate?». 6 March 2005. Archived from the original on 6 March 2005. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ a b c d «The Postal History of ICAO: Annex 10 — Aeronautical Telecommunications». ICAO. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d L.J. Rose, «Aviation’s ABC: The development of the ICAO spelling alphabet», ICAO Bulletin 11/2 (1956) 12–14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Annex 10 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation: Aeronautical Telecommunications; Volume II Communication Procedures including those with PANS status (7th ed.). International Civil Aviation Organization. July 2016. p. §5.2.1.3, Figure 5–1. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Deutsches Institut für Normung (2022). «Appendix B: Buchstabiertafel der ICAO („Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet»)». DIN 5009:2022-06.

- ^ a b «Phonetic Alphabet». GMDSS Courses and Simulators. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ Service de l’Information Aéronautique, Radiotéléphonie Archived 2 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 2nd edition, 2006

- ^ a b «COMMUNICATIONS INSTRUCTIONS RADIOTELEPHONE PROCEDURES: ACP125 (G)» (PDF). p. 3-2 – 3-7. Alt URL

- ^ «FAA Order JO 7110.65Z — Air Traffic Control». 2 December 2021. §2-4-16, TBL 2-4-1. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ a b «ITU Phonetic Alphabet and Figure Code» (PDF). ITU-R. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ a b International Maritime Organisation (2005). International Code of Signals, p. 22–23. Fourth edition, London.

- ^ «Radioman 3 & 2 Training Course Manual NAVPERS 10228-B» (PDF). 1957. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2018.

- ^ «Military phonetic alphabet by US Army». Army.com. 14 March 2014. Archived from the original on 2 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ «RP 0506 – Field Communication» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Written ‘nine’ in the examples, but pronunciation given as ‘niner’

- ^ a b c The ICAO specifically mentions that all syllables in these words are to be equally stressed (§5.2.1.4.3 note)

- ^ a b With the code words for the digits and decimal, each syllable is stressed equally.

- ^ a b Only the second (English) component of each code word is used by the Aeronautical Mobile Service.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i «The Evolution and Rationale of the ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization) Word-Spelling Alphabet, July 1959» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ a b c «Alpha, Bravo, Charlie: how was Nato’s phonetic alphabet chosen?». Archived from the original on 30 October 2017.

- ^ «North Atlantic Military Committee SGM-217-55 memorandum» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2017.

- ^ «North Atlantic Military Committee SGM-156-56 memorandum» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2017.

- ^ Radio Regulations 1959, pp. 430–431.

- ^ «Radio Regulations and Additional Radio Regulations (Geneva, 1959). Recommendation No. 30 — Relating to the Phonetic Figure Table». International Telecommunication Union (ITU). pp. 605–607.

- ^ Albert Pelsser, La storia postale dell’ ICAO, translated by Nico Michelini

- ^ a b «Draft of Convention and Regulations, Washington, D.C., December, 1920». 1921. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019.

- ^ a b «General Regulations and Additional Regulations (Radiotelegraph)». Washington: International Radiotelegraph Convention. 1927. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ «General Radiocommunication and Additional Regulations». Madrid: International Telecommunication Union. 1932. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ a b «General Radiocommunication Regulations and Additional Radiocommunication Regulations». Cairo: International Telecommunication Union. 1938. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ Radio Regulations and Additional Radio Regulations. Atlantic City: International Telecommunication Union. 1947. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Radio Regulations; Additional Radio Regulations; Additional Protocol; Resolutions and Recommendations (PDF). Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. 1959. pp. 430, 607. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ «Final Acts of WARC-79 (Geneva, 1979)» (PDF). Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. 1980. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ International Code of Signals for Visual, Sound, and Radio Communications, United States Edition, 1969 (Revised 2003) (PDF), 1969, archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2015, retrieved 31 October 2017

- ^ a b «(Don’t Get) Lost in Translation» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d Alcorn, John. «Radiotelegraph and Radiotelephone Codes, Prowords And Abbreviations» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2016.

- ^ «International Radio Conference (Atlantic City, 1947)». International Telecommunication Union. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ a b Myers, G. B.; Charles, B. P. (14 February 1945). CCBP 3-2: Combined Radiotelephone (R/T) Procedure. Washington, D.C.: Combined Communications Board. pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b «FM 24-12,:Army Extract of Combined Operating Signals (CCBP 2-2)» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b «Item 48 in the Friedman Collection: Letter from Everett Conder to William F. Friedman, February 11, 1952» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2016.

- ^ «Documents of the World Administrative Radio Conference to deal with matters relating to the maritime mobile service (WARC Mar)». Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. 1967. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ «Report on the Activities of The International Telecommunication Union in 1967». Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. 1968. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ ITU 1947, p. 275E.

- ^ a b «IMO Standard Marine Communication Phrases (SMCP)» (PDF). Rijeka: International Maritime Organization. 4 April 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ a b «Final Acts of WARC Mar». Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. 1967. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ Van Hare, Thomas (1 March 2013). «Uncle Sam’s Able Fox ‹ HistoricWings.com :: A Magazine for Aviators, Pilots and Adventurers». fly.historicwings.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ twincessna340a (20 August 2020). «8/18/20 — Taxiway DIXIE at ATL has Reverted to D». Airliners.net. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Klapper, Ethan [@ethanklapper] (21 August 2020). «Taxiway D at ATL has long been known as «Dixie» since it’s a mega hub for Delta and it was thought this would cause radio confusion. It’s now taxiway D — like at every other airport. !ATL 08/177 ATL TWY DIXIE CHANGED TO TWY D 2008181933-PERM» (Tweet). Retrieved 7 October 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Notice To Air Missions: Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Intl Airport, Atlanta, Georgia: Federal Aviation Administration, 18 August 2020, archived from the original on 6 January 2023, retrieved 6 January 2023,

!ATL 08/177 ATL TWY DIXIE CHANGED TO TWY D 2008181933-PERM

External links[edit]

- «The Postal History of ICAO: Annex 10 — Aeronautical Telecommunications». ICAO. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- «NATO Declassified — The NATO Phonetic Alphabet». North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

You may not think that spelling can be a life or death matter. But, the alphabets have actually been invented to avoid the fatal results that some spelling mistakes can have. Spelling alphabets are used to make radio messages as easily understood as possible especially by the military. The most prominent modern-day code is the NATO phonetic alphabet.

Let’s consider a scenario.

Imagine that you’re on the ground in a military operation. You might even be behind enemy lines!

You receive orders to make your way to the extraction point: go to map grid DH98. But instead, your unit heads for BA98, having misheard the radio message.

Avoiding a critical situation like this is why we have phonetic spelling alphabets.

You’ve probably heard spelling alphabets being used in movies and on TV.

You may have even visited a historical landmark which uses a spelling alphabet, like Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin. This marked the crossing between East and West Berlin during the Cold War. Officially called Checkpoint C.

The code word “Charlie” was used to avoid confusion between different checkpoints. For Example, B, C, and D, all of which sound very similar, especially over radio communication.

Thus, comes a unified alphabet system that can minimize the chances of miscommunication — the NATO Phonetic Alphabet.

What is the NATO Phonetic Alphabet?

The NATO phonetic alphabet is an alphabet used specifically for spelling out voice messages.

More accurately known as the International Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet (IRSA), or ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization) alphabet.

It’s the official one used by NATO allies to communicate when spelling out letters or digits. The alphabet was declassified by NATO and can be heard in both military and civilian situations.

Why Do We Need a Phonetic Alphabet?

Have you ever had problems spelling out your name or another message over the phone?

It’s quite common that the person you’re speaking to can mishear you.

Many English letters sound very similar and they can be easy to mix up. Especially, when you’re not speaking face-to-face and lack the usual visual cues which help you interpret speech.

These issues are compounded in combat areas. Mostly because the soldiers may be faced with loud background noise, radio static or interference.

Letters like m and n, b and d, c and v sound so alike. One can easily misunderstand them over long-distance communication.

While this is merely annoying in civilian life, it can have fatal results in a military context.

A phonetic alphabet makes voice messages and letter combinations clear and easy to understand.

How Does It Work?

Instead of spelling out things like map coordinates with letters, military personnel substitutes a code word for each letter.

Map grid DH98, for example, becomes “Delta-Hotel-Niner-Ait.”

This makes communication clear and avoids confusion.

With just using letters and numbers, messages can easily be confusing.

The alphabet uses code words that correspond to the 26 letters of the English alphabet. These codes are acrophonical, meaning that each letter’s name (or in this case, code word), begins with the letter itself.

For example, the letter A corresponds to the codeword Alpha, B to Bravo, C to Charlie and so on.

Check out this 26 code words for the NATO phonetic alphabet list in alphabetical order —

| The NATO Phonetic Alphabet Chart | ||

| Sl. No. | Letter | Nato Code |

| 1 | A | Alpha |

| 2 | B | Bravo |

| 3 | C | Charlie |

| 4 | D | Delta |

| 5 | E | Echo |

| 6 | F | Foxtrot |

| 7 | G | Golf |

| 8 | H | Hotel |

| 9 | I | India |

| 10 | J | Juliett |

| 11 | K | Kilo |

| 12 | L | Lima |

| 13 | M | Mike |

| 14 | N | November |

| 15 | O | Oscar |

| 16 | P | Papa |

| 17 | Q | Quebec |

| 18 | R | Romeo |

| 19 | S | Sierra |

| 20 | T | Tango |

| 21 | U | Uniform |

| 22 | V | Victor |

| 23 | W | Whiskey |

| 24 | X | X-ray |

| 25 | Y | Yankee |

| 26 | Z | Zulu |

Numbers also have their own particular assigned pronunciation for radio communication.

For example, 9 turns into niner and 5 is pronounced fifer, with an f instead of a v.

History of Spelling Alphabets

The current NATO phonetic alphabet is by no means the first of its kind.

The British and American militaries have been using their own locally invented code words for over a century now.

There are recorded spelling alphabets dating back to World War I. Back then, the British Armed Forces and the Royal Navy, in particular, used their own code words.

The Royal Navy used the official variant, with the letters A-E being represented by the words Apples, Butter, Charlie, Duff, and Edward.

Soldiers at the Western front used their own slang version, called “Signalese.”

Signalese had almost the same ideology behind it. But, the code words were different.

For example, Apples became Ack, Butter became Beer, and so on.

British armed forces changed to the RAF “Telephony Spelling Alphabet” and continued to use that up until 1956.

However, they made continuous changes over the years.

Over time, Apples changed to Ace and then Able or Affirm. Butter changed officially to Beer and then was eventually replaced by Baker.

The RAF alphabet was very similar to the U.S. system at the time. The U.S. developed their own phonetic alphabet used in the 1940s and 50s.

Some of their code words were Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog, Easy and Fox.

Eventually, the alphabet became known as “Able Baker” after the first two letters!

Fans of Vietnam War movies like Platoon have probably heard the American characters referring to the Vietnamese as “Charlie.”

If you’ve ever wondered why exactly, it’s actually because the Viet Cong were referred to by the U.S. military as VC or “Victor Charlie.”

However, the soldiers used the shorter version — Charlie.

The Need for a Unified System — The Birth of NATO Phonetic Alphabet

The problem was that these alphabets were only intended to be used by people from the same nation, and couldn’t be used internationally.

The codes rely on English-centric words and needed to be more relatable to worldwide users.

The solution was the ICAO alphabet, which was tested by users from 31 countries so that people could communicate no matter where they came from.

Britain and America both changed to the ICAO in 1956 to facilitate communication between nations.

The first internationally recognized spelling alphabet was actually instituted by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in 1927.

NATO forces used the ICAO since 1956 before it was eventually de-classified and came to replace the original ITU alphabet.

The Fundamentals of the ICAO Code

The code words weren’t just chosen at random!

The goal was to make the code as much clear and easy to understand as possible. There must be thousands of words in the English language that start with A, B, and any other letter.

When selecting the final code words, hundreds of comprehension tests were performed to see which words were the easiest to understand over voice communication.

The code words had to be understood by people of 31 nationalities and heard not only in isolation but in the context of a message.

The word Football was most easily understood as an isolated word.

However, Foxtrot became the official code for the letter F. Because it had better results when used in an extended message.

Some other rejected code words include Nectar, which was replaced by November.

Similarly, Extra, which was substituted with X-ray after complaints that the original words were too hard to understand in poor radio conditions.

Code words have changed over the years, with experience fuelling improved word choices for maximum intelligibility.

Practical Uses in Modern Days

Military personnels have been using the phonetic alphabets for a hundred years, but they’re also a major part of the aviation industry.

In fact, the ICAO alphabet was the creation of an aviation organization and air traffic controllers used it to communicate with pilots. Airlines also use it to communicate passenger name records.

Transport organizations in general use spelling alphabets to transmit codes, with the International Maritime Organization also contributing to the evolution of code words.

Medical professionals, law enforcement officials, banks or civilians who often need to talk over the radio or even telephone, like call center workers, for example, find a spelling alphabet useful at times.

Most often, civilians just make up their own code words as most people haven’t memorized the particular ICAO alphabet unless their profession demands it.

There are a few phonetic alphabets in use these days.

The ICAO may seem a bit too militaristic for civilian use. In that case, try the Western Union Phonetic Alphabet which uses more civilian-friendly (although very U.S. based) words like Adams, Boston, and Chicago.

Try the LAPD Phonetic alphabet if you’re a fan of TV cop shows like Starsky and Hutch, who called their car “Zebra 3” instead of just “Z3.”

Final Words

It’s not hard to find chances to use a phonetic alphabet in your daily life. If you have kids, teach them phonics (how to recognize letter sounds) by using the NATO phonetic alphabet, or better yet, help them make up their own code words!

Also, you should ask your kids to have a better grasp at these sight words as these are the most common words in the English language.

Websites like SpellQuiz.com can help you and your kids practice English spelling test by developing your awareness of phonics and the sounds associated with the letters of the alphabet. Try this vocabulary tester to understand your current skill level!

The next time you have to spell your name, or any other word for that matter, why not try using a few code words to get your message across clearly, as well as adding some fun into spelling?

Now you can take part in online Spelling Bee too! Check out the SBO section on Spellquiz today!

Oh how I loved secret codes when I was a kid. The ability to write a coded letter without anyone but the recipient was just plain fun. Today on Kids Activities Blog we have 5 secret codes for kids to write their own coded letter.

Shhhh…don’t say it out loud! Write a secret coded letter for someone to decode (or try to decode). Use these 5 secret code examples as inspiration for your next secretive adventure.

1. Reversed Words Letter Code

This is a simple code to solve – just read the words backwards! Even though it seems simple once you know the secret, it can be a hard one to figure out when you don’t.

Decode: REMMUS NUF A EVAH

Answer: Have a fun summer

2. Half-Reversed Alphabet Letter Codes

Write out the alphabet letters from A to M then write the letters from N to Z directly below them. Simply exchange the top letters for the bottom letters and vice versa.

Decode: QBT

Answer: DOG

Number Lettering Code Variation

Just like seen above in the half-reversed alphabet, you can assign numbers to letters in a tricky way and then substitute those numbers for the letters in the words and sentences. The most common numbers the alphabet 1-26, but that is easy to decode.

Can you come up with a better number lettering code?

3. Block Cipher Secret Codes

Write the message in a rectangular block, one row at a time – we used 5 letters in each row (alphabet letters in order A-E).

Can you figure out what the KEY is to the block cipher pictured above? Each letter is shifted one place in the second row. You can make any key correspond to the rows making it as simple or complex to figure out. Then write down the letters as they appear in the columns.

Decode: AEC

Answer: BAD

4. Every Second Number Letter Code

Read every second letter starting at the first letter, and when you finish, start again on the letters you missed.

Decode: WEEVLEIRKYE – STUOMCMAEMRP (mistake made on lower line)

Answer: We Like to camp every summer

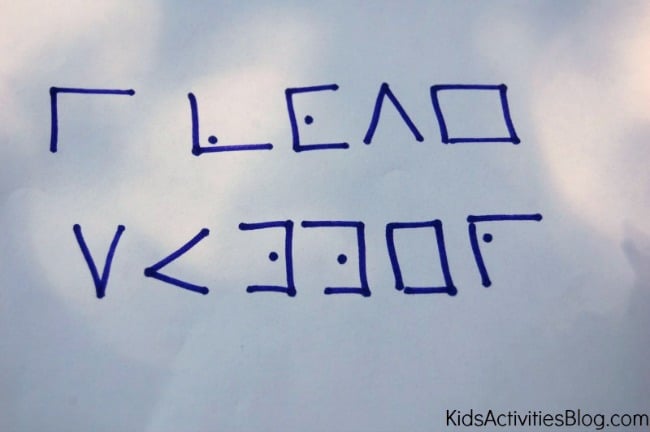

5. PigPen Secret Code

The PigPen code is easier than it looks and is my children’s favorite. First, draw out the two grids below and fill in the letters:

Each letter is represented by the lines around it (or pigpen).

Decode: image above

Answer: I LOVE SUMMER

Write a Coded Letter

We practiced writing our names and silly words before moving to coding whole sentences.

Related: Write a Valentine code

The letters and messages you can write can be fun, but make sure you send along a key so the recipient can figure it all out!

This article contains affiliate links.

Secret Code Toys for Kids We Love

If your child loved these secret code activities, then you might consider some of these fun and mind-stretching toys:

- Melissa & Doug On the Go Secret Decoder Deluxe Activity Set and Super Sleuth Toy – gives kids a chance to crack codes, uncover hidden clues, reveal secret messages and be super sleuths.

- Secret Codes for Kids: Cryptograms and Secret Words for Children – this book includes 50 cryptograms for children to solve including secret and hidden words written as number codes from super easy to super difficult.

- Secret Code Breaking Puzzles for Kids: Create and Crack 25 Codes and Cryptograms for Children – this book is good for kids 6-10 years old and contains clues and answers for kids to make and break their own codes.

- Over 50 Secret Codes – this entertaining book will put kids code-cracking skills to the test while learning how to disguise their own secret language.

More Writing Fun from Kids Activities Blog

- You’ve mastered the art of secret code! Why not try to our crack the code printable now?

- Check out this cool ways to write numbers.

- Interested in poetry? Let us show you how to write a limerick.

- Draw cars

- Help your child with their writing skills and donate their time to a good cause by writing cards to the elderly.

- Your little one will love our kids abc printables.

- Draw a simple flower

- Here are some great ideas to teach your child to learn to write their name.

- Make writing fun with these unique activities!

- Aid your child’s learning with these alphabet handwriting worksheets for kindergarten kids.

- Drawing a butterfly

- Avoid any accidents while writing. Instead of an electric or razored pencil sharpener, try this traditional pencil sharpener instead.

- Work on your child’s motor skills with these free Halloween tracing worksheets.

- These tracing sheets for toddlers will also help your child’s motor skills as well.

- Need more tracing sheets? We got them! Take a look at the preschool tracing pages.

- US Teacher Appreciation Week

- Is your kid not doing well with writing? Try these kids learning tips.

- Maybe it isn’t the lack of interest, perhaps they aren’t using the proper writing grip.

- These fun harry potter crafts will teach you to make the cutest pencil holder.

- We have even more learning activities! Your little one will enjoy these learning colors activities.

How did your coded letter turn out? Did you keep your message a secret?

Rebecca Darling, momma of 3 sassy Texas kiddos, writes a blog dedicated to family travel at R We There Yet Mom?. Although she swears she is not crafty, this momma never lacks in creativity and enthusiasm — her ultimate goal is making exceptional memories for her family. Follow her memory making at R We There Yet Mom?, on Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest.

Symbol Test Box

You can copy & paste, or drag & drop any symbol to textbox below, and see how it looks like.

Miscellaneous Symbols

- A Alphabet

- 🐱 Animal Symbols

- → Arrows Symbols

- 💪 Body Part Emojis

- ‣ Bullets Symbols

- ✓ Check Mark Symbols

- © Copyright Symbol

- ° Degree Sign

- 🏁 Flag Symbols

- 🍔 Food Emojis

- ♂ Gender Symbols

- ♥ Heart Symbols

- ∞ Infinity Symbol

- ♺ Recycling Symbols

- ✝ Latin Cross

- ♫ Music Note Symbols

- ☮ Peace Sign Symbol

- ® Registered Mark

- ☠ Skull And Crossbones

- ❄ Snowflakes Symbols

- ☺ Emoticons Smiley

- ♃ Planet Symbols Astrological

- ★ Star Symbols

- ☢ Radioactive Hazard Symbols

- ☏ Telephone Symbols

- ™ TM Symbol Trademark

- ☼ Weather Symbols

- ♓ Zodiac Signs

How to Use Symbols

First select the symbol then you can drag&drop or just copy&paste it anywhere you like.

Alt-Codes can be typed on Microsoft Operating Systems:

- First make sure that numlock is on,

- Then press and hold the ALT key,

- While keeping ALT key pressed type the code for the symbol that you want and release the ALT key.

Unicode codes can not be typed. Codes can be used within HTML, Java..etc programming languages. To use them in facebook, twitter, textbox or elsewhere just follow the instructions at top.