Phrases like ‘digital clocking’, ‘word clock’ and ‘interface jitter’ are bandied around a lot in the pages of Sound On Sound. I’m not that much of a newbie, but I have to admit to being completely in the dark about this! Could you put me out of my misery and explain it to me?

James Coxon, via email

SOS Technical Editor Hugh Robjohns replies: Digital audio is represented by a series of samples, each one denoting the amplitude of the audio waveform at a specific point in time. The digital clocking signal — known as a ‘sample clock’ or, more usually, a ‘word clock’ — defines those points in time.

When digital audio is being transferred between equipment, the receiving device needs to know when each new sample is due to arrive, and it needs to receive a word clock to do that. Most interface formats, such as AES3, S/PDIF and ADAT, carry an embedded word-clock signal within the digital data, and usually that’s sufficient to allow the receiving device to ‘slave’ to the source device and interpret the data correctly.

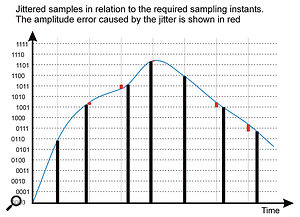

Unfortunately, that embedded clock data can be degraded by the physical properties of the connecting cable, resulting in ‘interface jitter’, which leads to instability in the retrieved clocking information. If this jittery clock is used to construct the waveform — as it often is in simple D-A and A-D converters — it will result in amplitude errors that could potentially produce unwanted noise and distortion.

For this reason, the better converters go to great lengths to avoid the effects of interface jitter, using a variety of bespoke re-clocking and jitter-reduction systems. However, when digital audio is passed between two digital devices — from a CD player to a DAW, say — the audio isn’t actually reconstructed at all. The devices are just passing and receiving one sample value after another and, provided the numbers themselves are transferred accurately, the timing isn’t critical at all. In that all-digital context, interface jitter is totally irrelevant: jitter only matters when audio is being converted to or from the digital and analogue domains.

Where an embedded clock isn’t available, or you want to synchronise the sample clocks of several devices together (as you must if you want to be able to mix digital signals from multiple sources), the master device’s word clock must be distributed to all the slave devices, and those devices specifically configured to synchronise themselves to that incoming master clock.

An orchestra can only have one conductor if you want everyone to play in time together and, in the same way, a digital system can only have one master clock device. Everything else must slave to that clock. The master device is typically the main A-D converter in most systems, which often means the computer’s audio interface, but in large and complex systems it might be a dedicated master clock device instead.

The word clock can be distributed to equipment in a variety of forms, depending on the available connectivity, but the basic format is a simple word-clock signal, which is a square wave running at the sample rate. It is traditionally carried on a 75Ω video cable equipped with BNC connectors. It can also be passed as an embedded clock on an AES3 or S/PDIF cable (often known as ‘Digital Black’ or the AES11 format), and in audio-video installations a video ‘black and burst’ signal might be used in some cases.

Спрашивают про WordClock. Это замечательно и прекрасно, что люди, занимающиеся прокатом, озадачиваются проблемами звучания, и вникают в тему. Отвечаю.

При переводе аудиосигнала из аналоговой среды в цифровую (посредством импульсно-кодовой модуляции, или PCM) происходит его конвертация, или преобразование. Непрерывная аналоговая синусоида приобретает вид последовательно записанных отдельных (дискретных) значений уровня сигнала (сэмплов). Данный сэмпл также называют «цифровым словом» (Word). Количество сэмплов в секунду называется скоростью сэмплирования, или частотой дискретизации. Максимально возможное количество битов определяет «длину цифрового слова». Наиболее распространенные сейчас – 16 бит, 20 бит и 24 бит. 1 бит отвечает за 6дБ динамического диапазона. Больше битов – больше динамический диапазон. Соответственно, 16 бит = 96дБ, 20 бит = 120дБ, 24 бит = 144дБ.

Но перейдем к частоте дискретизации. Практически любое устройство для цифрового аудио имеет внутри себя тактовый генератор, который задает эту самую частоту для работы всего устройства в целом. Обычно это частоты 44,1кГц и 48кГц, а также их удвоенные значения – 88,2кГц и 96кГц. Первоначальная частота – 44,1кГц была выбрана согласно правилу Найквиста – «скорость сэмплирования определяет верхнюю границу диапазона в соотношении 2,2х1.» Следовательно, для воспроизведения аудио 20кГц необходима скорость сэмплирования, или частота дискретизации, как минимум 44кГц. Соотвественно, если прибор работает на частоте 96кГц, то он обеспечивает верхнюю границу частотного диапазона 43.6кГц. В звукоусилении подобные требования представляются чересчур избыточными.

Проблема появляется при соединении двух и более цифровых устройств. Например, цифровой пульт, внешний ревербератор, подключенный по AES, и контроллер АС, на который сигнал также приходит в цифровом виде. Мало, чтобы у них были одинаковые параметры, например 24бит/48кГц. Необходимо, чтобы их внутренние процессоры получали тактовые импульсы одновременно. Иначе сигнал с пульта, идущий на ревербератор, будет смещен по времени относительно тактового генератора внутри ревера, затем этот смещенный сигнал идет обратно на пульт, затем вся эта каша отправляется на процессор для АС, где совершенно своя история с началом сэмплов. В итоге саунд будет очень далек от ожидаемого.

Решение у этой проблемы довольно простое – необходимо установить для всех цифровых устройств единое время (Clock) для отсчета «цифровых слов» (Word). Например, если имеется несколько цифровых устройств в цепочке, можно один сделать главным (Master), остальные будут подчиненными (Slave), и генератор Мастера будет определять начало отсчета сэмплов для всех устройств. Способ получения устройством внешнего WordClock выбирается на самом устройстве.

Он может приходить на девайс как по отдельному кабелю, так и по первому каналу AES вместе с аудио. Во втором случае устройство выделяет из приходящего сигнала тактовую частоту и просто синхронизирует внутренний генератор с приходящим сигналом.

Это, самое очевидное и простое решение, имеет серьезный минус – качество внутреннего генератора. Самое важное в WordClock – его стабильность. Для любого отдельного устройства стабильность внутреннего генератора не самое важное, важнее качество конвертеров, алгоритмы и т.п. И прибор сам по себе работает великолепно, стабильности генератора для этого достаточно. Но, когда он становится частью системы, эта достаточность превращается в проблему. Решение – внешний WordClock генератор. И здесь опять – стабильность – единственный фактор в качестве прибора. Потому как стабильность внешнего генератора отвечает за звучание системы. Это парадокс цифрового аудио, когда устройство, не имеющее непосредственно к аудиосигналу никакого отношения, определяет его качество. Хотя, почему парадокс? В аналоговом аудио качество напряжения тоже не последний фактор для звучания аудиосистемы.

Среди WordClock генераторов успешно себя зарекомендовала немецкая контора Rosendahl. Их прибор NanoClocks пока что наиболее почитаем в про-аудио среде.

Биг Бен от Апогея тоже называется WC generator, но это какое то другое WC.

Вот так, коротенько.

думаете наступит эльдорадо?

Учитывая то, что единственная функция этой штуки посылать с минимальным уровнем джиттера 0 и 1, я бы сходу эту идею не отметал, хотя скепсис понятен.

Человек из Алефа, который мне её посоветовал чинит и разрабатывает ЦАПы, т.е. вроде как в теме. Из того, что он мне говорил, я понял не всё, но главная идея в том, что эта плата построена на каком то очень качественном чипе, и что в ней встроено что то типа собственного word clock, т.е. выходящий с неё сигнал будет с минимальным уровнем джиттера. В общем она не гонит потоком то что на неё приходит, а сама формирует равномерный сигнал. Извините за кривое изложение, не специалист.

Насчёт корпуса да, нужен. Сделать его не сложно. Ещё по уму правильное питание на эту плату хорошо бы подать, хотя можно просто через USB её питать.

Я не пытаюсь адски сэкономить, просто если это будет очень хорошо, то не вижу смысла делать то же самое очень хорошо за дороже.

P.S. и уж если касаться темы скепсиса, то я с трудом верю, за любые деньги можно к этому плееру что то прикрутить, что бы оно было хотя бы не хуже по сравнению с проигрыванием в нем обычного CD диска.

-

#1

Помогите не ловится word clock out от ЦАПа на проф. студийную звуковую карточку с word clock in входом (M-audio Delta 10/10 lt но это не принципиально — думаю они все жестко стандартизированы)

Согласно пдф вот что на выходе клока у цапа :

http://www.sound4sale.com/manuals/gold4Manual.pdf

страница 6

lvds формат . 250 mV

сделали уже 2 кабеля — оба карточка не видит. Использовались контакты 1 земля и 3 M clock +

В драйверах на входе word clock пишется unlocked

На осцилографе четко видно что клок от цапа идет (кривоватый чутка, но думаю нормально. размах 300-400 mV). Нашел поиском к примеру у rme fireface — там 300 mV размах в мануале.

Вопрос в том какие стандартные параметры для студий для принимающих устройств (в пдф для звуковухи нет таких данных). Возможно размах другой, возможно волновое сопротивление надо обязательно 75 ом и это очень критично. Подскажите пожалуйста может кто сталкивался с такой проблемой.

-

#2

думаю они все жестко стандартизированы

Если мне склероз не изменяет, то дела обстоят как раз-таки с точностью до наоборот: единого стандарта на word clock не существует. Это во-первых.

Во-вторых, задекларированные вашим ЦАПом 250 mVpp на выходе (и даже измеренные 300-400) — это очень мало для «традиционных» word clock input’ов. Упомянутый вами fireface, для которого 300 mVpp на входе является достаточной величиной,- это скорее исключение и хороший образец «всеядности». Однако, если вы посмотрите word clock-выход того же fireface’а, то обнаружите там на порядок большее значение напряжения: для ff800, согласно мануалу, при работе на 75 Ом-нагрузку задекларировано 4 Vpp на выходе!

Поскольку вы располагаете осциллографом, вы самостоятельно можете измерить размах на WC-выходе вашей «дельты», чтобы примерно представить, ЧТО она желала бы видеть на своём WC-входе, и, полагаю, тогда вопрос «почему оно не работает» снимется сам собой.

Update

глянул ради интереса на 6ую страничку pdf-ки вашего ЦАПа. Ну что тут можно сказать… То, что выходит с контактов MClock+ и MClock-, к «традиционному» WC отношения не имеет по трём причинам:

1. Ваш прибор предполагает передачу сигнала по симметричной линии, в то время как традиционный WC «ассиметричный». Но это ерунда по сравнению со следующими пунктами.

2. Как упоминалось выше, выходное напряжение (0.25В) вашего ЦАП не соответствует значениям (порядка 2.5В) входного напряжения «традиционных» WC-входов.

3. Самое существенное и принципиальное отличие: выходная частота «часов» вашего ЦАП в сотни раз (если быть точным, то в 512 раз для 44.1кГц и для 48.0кГц) превышает ту, которую ожидает увидеть несчастный WC-вход «дельты».

Так что увы — без дополнительных ухищрений ваши приборы не «снюхаются».

Последнее редактирование: 29 Авг 2013

-

#3

Еще вопрос, насколько эта М-Аудио будет хорошо ходить от внешнего клока, овчинка может оказаться не стоящей выделки… Это раз, а во-вторых обычно клочат все остальные приборы от ацп, а не от цап. То есть мастером должна быть карта.

Если вышеописанное не изменило ваших намерений, то вот что еще:

Судя по описанию, на вашем цапе вход для вордклока симметричный, попробуйте подключить вордклок кабель не между землей и М+, а между М+ и М-. Это может быть критично в зависимости от схемотехники этого входа.

Далее, нога 2 разъема должна висеть в воздухе, чтобы цап работал в режиме мастера или замкнута на землю, чтобы он работал в режиме слейва. Нога 5 по идее тоже должна висеть, не знаю что там имеется в виду под networking, если синхронизация, то да.

Если и тогда не будет работать, тогда можно сымитировать вордклок от любого внешнего генератора прямоугольной волны, поиграть с амплитудой, может и действительно просто ее не хватает для захвата.

-

#4

Спасибо за подробный ответ.

Да выяснил опытным путем(теория и практика) что карточки обычно ловят от 1v (декларируется 3-5v стандарт).

Насчете lvds (он для длинным расстояний балансный), то проблемы взять только + в прицнипе нет.

Насчет частоты вот вопрос. Честно говоря тут немного озадачен. Вы может с super clock путаете ? он аля 256*fs идет, но наоборот как раз таки wc «стандартнее не бывает стандарт»

Вообщем сейчас все упирается в конкретную реализацию. Есть микросхемы lvds to ttl которые поднимут уровень, но пока буду пытаться пойти простым путем — поднять уровень трансиком повышающим.

-

#5

вообще да, там на стр 6 прямо и написано, что частота синхросигнала порядка 22-25 мегагерц

-

#6

Спасибо. Походу разобрался. word clock по умолчанию 44-48кгц и идет ? я думал он в мегагерцах как раз и нужен изначально.

Тогда действительно надо брать рме или инфрасоник — у них есть опция «вход суперклок» т.е. будет 44.1*256 = 11.2 мгц на входе видеть.

Ну и там есть выбор частоты клока входного. Для 44 выбираешь 88 кгц и искомые 22(или 24) и получатся. Вуаля…

осталось поднять уровень только. Надо профессионал по вч трансам кто подскажет реально ли на таких высоких частотах это сделать.

-

#7

Ага, обычный вордклок он на частоте дискретизации работает. А этот даже не суперклок, это называется мастерклок, как раз в районе 24 мегагерц. В описании этого приборчика в разделе спецификации есть упоминание http://www.m2tech.biz/evo_clock.html

А с трансом думаю несложно, проще чем на звуковых частотах. Надо поискать в гугле что-то типа broadband RF transformers.

-

#8

Да я тоже эту ссылку нагуглил недавно Будем посмотреть. Завтра гляну что на выходе у карточки у WC творится для начала.

-

#9

Да хреново. Надо чтобы именно Super Clock (11, 12 мгц = 256*wc) понимала карточка, а таких единицы. Рме вот нашел, а она не понимает. Может из дорогих внешних конвертеров что-то понимает ? Focusite , Presonus итп ? Их правда и список не такой большой с выходом-входом word clock на бнц в прицнипе.

-

#10

Любую карту с WC, плюс Rosendahl Nanoclocks (старый), у него есть SuperClock. Клочить все устройства от него.

Или уже не маяться дурью.

-

#11

Почему имеено старый ? есть и подешевле девайсы типа lucid. Их и думаю попробовать.

-

#12

Тут проблема в том, что от этой синхронизации просто может не быть никакой пользы. Сейчас часто производители ставят на карту вход WC и продают как профессиональные, но реализация самой этой синхронизации хуже всякой критики. В продуктах м-аудио это очень вероятно, так как они никогда особо профессиональные вещи не делали.

Ты все засинхронизируешь, а джиттер увеличится, или щелчки будут в тракте раз в минуту или еще что…

-

#13

Потому что на новом нет СуперКлока.

есть и подешевле девайсы типа lucid. Их и думаю попробовать.

Тогда смысла в применении их нет никакого смысла. Подключайте выход карты на вход ЦАПа и не дурите другим головы.

Тут проблема в том, что от этой синхронизации просто может не быть никакой пользы.

Убедить в этом будет, скорее всего, невозможно.

-

#14

Methafuzz,

Естественно об этом думаю — особенно реализация через внешний генератор вопросы имеет, хотя опять же многие пишут о пользе такого подключения. Кроме как реально проверить и самому убедиться других вариантов не вижу Посмотрим. Договорился digidesign usd взять тут попробовать.

Ifrit,

Форум создан не чтобы головы дурить, а чтобы вопросы задавать и обсуждать. За помощь спасибо. А убеждать не надо ни в чем — привык все проверять и своим ушам верить, а не форумам.

-

#15

Взял infrasonic quartet. И взял попробовать внешний генератор digidesign sync usd. На удивление и он с двумя разными карточками плохо работает. Обычно сильный шум-помехи в канале. Или нет звука вообще или проблемы со скоростью и тоже шум… пишется unlocked.

Кто сталкивался с такими проблема с синхрой ? Завтра буду другой комп пробовать. Странно…

-

#17

На удивление и он с двумя разными карточками плохо работает.

это не генератор, это скорее карточки такие…

Long

Well-Known Member

-

#18

— Траблы потому, что не существует СТАНДАРТА на WC.

Поэтому, если апппарат не лочится ко внешнему клоку — то, скорее всего,

ему элементарно не хватает амплитуды этого самого клока.

-

#1

I’m trying to connect my PC sound card with word clock input to external DAC and get best sound possible. I think that appropriate solution is to install low jitter clock into DAC and feed soundcard and CD transport from it.

The DAC is Parasound DAC1600 (CS8412->PMD100->4*PCM63P-K). Transport is Parasound CDP1000 (AKA CEC 2200). What should be done to implement this? I’m lost in external clocking of CS8412 + PMD100, please advice.

Thanks,

Victor

-

#3

I don’t think all those PLLs and VCXOs are required in this case. Just implement a good quartz oscillator in the DAC. This will have far less noise than any VCXO. Use an 8-bit counter to output the word clock every 64th edge of the main clock, and output this signal on BNC to your sound card.

I haven’t seen many PC sound cards with this ability. What kind is it?

-

#4

jwb said:

I don’t think all those PLLs and VCXOs are required in this case. Just implement a good quartz oscillator in the DAC. This will have far less noise than any VCXO. Use an 8-bit counter to output the word clock every 64th edge of the main clock, and output this signal on BNC to your sound card.

I haven’t seen many PC sound cards with this ability. What kind is it?

So jwb, how many transports are you aware of with a system clock of Fs?

BTW, are you aware that wordclock reference is Fs?

-

#5

Well it doesn’t really matter. You can either 1) output the Fs to the CD player and multiply it by 64 to get the master clock, or 2) output the master clock directly from the DAC to the CD player. You still don’t need PLLs and VCXO’s. I see no reason to try to use two clocks with a lot of circuitry to keep them syncronized. All you need is a low-jitter master clock driving the DAC, and the same clock driving all the other gear.

-

#6

jwb said:

Well it doesn’t really matter. You can either 1) output the Fs to the CD player and multiply it by 64 to get the master clock, or 2) output the master clock directly from the DAC to the CD player. You still don’t need PLLs and VCXO’s. I see no reason to try to use two clocks with a lot of circuitry to keep them syncronized. All you need is a low-jitter master clock driving the DAC, and the same clock driving all the other gear.

Oh, but it does matter.

Lets start with the dac. The dac in question uses the CS8412 and that makes master clock (MCLK) 256Fs not 64Fs, nevermind the fact that the SM5842 will not get out of bed for anything other than 256 or 384 Fs.

Then there is already present clock domain, the 256Fs one derived by the CS8412 from the SPDIF datastream. Attempting to add a second standalone XO domain without due care and attention would not be wise. One would have to synchronize the two domains for the system to work properly.

Now to the transport. It is just as likely to run at 256Fs as at 384Fs but probably not 64Fs, so simply sending MCLK across may not suffice. Now if you could just point me in the direction the clock multiplier that does not use a PLL or its digital equivalent.

-

#7

It’s incredible what you can find out on your on hard drive. I found schematics of what I want: I put it there in WMF and MS Word foramts. Do you see any flaws in it, except clock schematics (I will use KC-7, probably)?

jwb said:

I don’t think all those PLLs and VCXOs are required in this case. Just implement a good quartz oscillator in the DAC. This will have far less noise than any VCXO. Use an 8-bit counter to output the word clock every 64th edge of the main clock, and output this signal on BNC to your sound card.

That are exactly my thoughts

I haven’t seen many PC sound cards with this ability. What kind is it?

You have to look at pro and «prosumer» range of soundcards. Examples are Lynx AES16 or Two and ESI Juli@

-

#8

jwb said:

Well it doesn’t really matter. You can either 1) output the Fs to the CD player and multiply it by 64 to get the master clock, or 2) output the master clock directly from the DAC to the CD player. You still don’t need PLLs and VCXO’s. I see no reason to try to use two clocks with a lot of circuitry to keep them syncronized. All you need is a low-jitter master clock driving the DAC, and the same clock driving all the other gear.

My CDP uses 386*Fs clock, and DAC 256*Fs clock. This is the reason for PLL to exist, but I think clock for DAC and PLL for CDP is more appropriate

Library

Collection

{{searchPageHeadline}}

{{ categories.parent.title }}

{{searchPageHeadline}}

Back to All {{ categories.parent.title }}

Sounds

{{ subCategory.title }}

{{searchPageHeadline}}

No results for «{{ capitalize(pageTitle) }}»

Make sure your spelling is correct. Otherwise, try browsing our categories below.

Showing results {{ thousands_separators((getBasicPages + 1)) }} —

{{ thousands_separators(getBasicMaxPage) }} of {{ thousands_separators(totalHits) }}

{{ searchModeType }}

Clear filters

We couldn’t find any results that match your filters

About Word Clock, SMPTE, and MIDI Clock

Before we start looking at how Cubase handles synchronization, it is important to understand the different types of synchronization, its terminology, and the basic concepts behind these terms. The idea behind synchronization is that there will always be a sender/receiver relation between the source of the synchronization and the recipient of this source. There can only be one sender, but there can be many receivers to this sender. There are three basic concepts here: timecode, MIDI Clock, and Word Clock.

Timecode

The concept behind timecode is simple: It is an electronic signal used to identify a precise location on time-based media, such as audio, videotape, or in digital systems that support timecode. This electronic signal then accompanies the media that needs to be in sync with others. Imagine that a postal worker delivering mail is the locking mechanism, the houses on the street are location addresses on the timecode, and the letter has matching addresses. The postal worker reads the letter and makes sure it gets to the correct address, the same way a synchronizing device compares the timecode from a source and a destination, making sure they are all happening at the same time. This timecode is also known as SMPTE ( Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers ), and it comes in three flavors:

-

MTC (MIDI Timecode). Normally used to synchronize audio or video devices to MIDI devices such as sequencers. MTC messages are an alternative to using MIDI Clocks (a tempo-based synchronization system) and Song Position Pointer messages (telling a device where it is in relation to a song). MTC is essentially SMPTE (time-based) mutated for transmission over MIDI. On the other hand, MIDI Clocks and Song Position Pointers are based upon musical beats from the start of a song, played at a specific tempo (meter-based). For many nonmusical cues, such as sound elements that are not part of a musical arrangement but rather sound elements found on movie sound tracks (for example, Foley, dialogue, ADR, room tones, and sound effects), it’s easier for humans to reference time in some absolute way (time-based) rather than musical beats at a certain tempo (music-based). This is because these events are regulated by images that depict time passing, whereas music is regulated by bars and beats in most cases.

-

VITC (Vertical Interval Timecode). Normally used by video machines to send or receive synchronization information from and to any type of VITC-compatible device. This type of timecode is best suited for working with a Betacam or VTR device. You will rarely use this type of timecode when transferring audio-only data back and forth. VITC may be recorded as part of the video signal in an unused line, which is part of the vertical interval. It has the advantage of being readable when the playback video deck is paused .

-

LTC (Longitudinal Timecode). Also used to synchronize video machines, but contrary to VITC, it is also used to synchronize audio-only information, such as a transfer between a tape recorder and Cubase. LTC usually takes the form of an audio signal that is recorded on one of the tracks of the tape. Because LTC is an audio signal, it is silent if the tape is not moving.

Each one of these timecodes uses an hours: minutes: seconds: frames format.

NOTE

ABOUT MOVIE SOUND TRACKS

The sound track of a visual production is usually made up of different sounds mixed together. These sounds are divided into six categories: Dialogue, ADR, Foley, Ambiances, Sound Effects, and Music.

The dialogue is usually the part played by the actors or narrated off-screen .

The ADR ( Automatic Dialogue Replacement ) refers to the process of rerecording portions of dialogue that could not be properly recorded during the production stage for different reasons. For example, if a dialogue occurs while there is a lot of noise happening on location, the dialogue is not usable in the final sound track, so the actor rerecords each line from a scene in a studio. Another example of ADR is when a scene is shot in a restaurant where the atmosphere seems lively. Because it is easier to add the crowd ambiance later, the extras in the shot are asked to appear as if they are talking, but, in fact, they might be whispering to allow the audio boom operator to get a good clean recording of the principal actors’ dialogue. Then, later in a studio environment, additional recordings are made to recreate the background chatter of people in this restaurant.

The Foley (from the name of the first person who used this technique in motion pictures) consists of replacing or enhancing human- related sounds, such as footsteps, body motions (for example, noises made by leather jackets, or a cup being placed on a desk, and so on), or water sounds (such as ducks swimming in a pond, a person taking a shower, or drowning in a lake).

Ambiances, also called room tones , are placed throughout a scene requiring a constant ambiance. This is used to replace the current ambiance that was recorded with the dialogue, but due to the editing process, placement of camera, and other details that affect the continuity of the sound, it cannot be used in the final sound track. Take, for example, the rumbling and humming caused by a spaceship’s engines. Did you think that these were actually engines running on a real spaceship?

The sound effects in a motion picture sound track are usually not associated with Foley sounds (body motion simulation sounds). In other words, «sound effects» are the sounds that enhance a scene in terms of sonic content. A few examples are explosions, gun shots, the «swooshing» sound of a punch, an engine revving, a knife slashing, etc. Sound effects aren’t meant to mimic but to enhance.

And last but not least, the music, which comes in different flavors, adds the emotional backdrop to the story being told by the images.

Frame Rates

As the name implies, a frame rate is the amount of frames a film or video signal has within a second. It is also used to identify different timecode uses. The acronym for frame rate is «fps» for Frames Per Second. There are different frame rates, depending on what you are working with:

-

24 fps. This is used by motion picture films and in most cases, working with this medium will not apply to you because you likely do not have a film projector hooked up to your computer running Cubase to synchronize sound.

-

25 fps. This refers to the PAL ( Phase Alternation Line ) video standard used mostly in Asia and SECAM/EBU ( Sequential Color And Memory/European Broadcast Union ) video standard used mostly in Europe. If you live in those areas, this is the format your VCR uses. A single frame in this format is made of 625 horizontal lines.

-

29.97 fps. Also known as 29.97 nondrop and may also be seen as 30 fps in some older two-digit timecode machines (but not to be mistaken with the actual 30 fps timecode; if you can’t see the 29.97 format, chances are the 30 format is its equivalent). This refers to the NTSC ( National Television Standards Committee ) video standard used mostly in North America. If you live in this area, this is the format your VCR uses. A single frame in this format is made of 525 horizontal lines.

-

29.97 fps DF. Also known as 29.97 drop frame (hence the DF at the end). This can also be referred to as 30 DF on older video timecode machines. This is probably the trickiest timecode to understand because there is a lot of confusion about the drop frame. To accommodate the extra information needed for color when this format was first introduced, the black-and-white’s 30 fps was slowed to 29.97 fps for color. Though not an issue for most of you, in broadcast, the small difference between real time (also known as the wall or house clock) and the time registered on the video can be problematic . Over a period of one SMPTE hour, the video is 3.6 seconds or 108 extra frames longer in relation to the wall clock. To overcome this discrepancy, drop frames are used. This is calculated as follows : Every frame 00 and 01 are dropped for each minute change, except for minutes with 0’s (such as 00, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50). Therefore, two frames skipped every minute represents 120 frames per hour, except for the minutes ending with zero, so 120×12 = 108 frames. Setting your frame rate to 29.97 DF when it’s notin other words, if it’s 29.97 (Non-Drop)causes your synchronization to be off by 3.6 seconds per hour .

-

30 fps. This format was used with the first black-and-white NTSC standard. It is still used sometimes in music or sound applications in which no video reference is required.

-

30 fps DF. This is not a standard timecode protocol and usually refers to older timecode devices that were unable to display the decimal points when the 29.97 drop frame timecode was used. Try to avoid this timecode frame rate setting when synchronizing to video because it might introduce errors in your synchronization. SMPTE does not support this timecode.

Using the SMPTE Generator Plug-in

The SMPTE Generator (SX Only) is a plug-in that generates SMPTE timecode in one of two ways:

-

It uses an audio bus output to send a generated timecode signal to an external device. Typically, you can use this mode to adjust the level of SMPTE going to other devices and to make sure that there is a proper connection between the outputs of the sound card associated with Cubase and the input of the device for which the SMPTE was intended.

-

It uses an audio bus output to send a timecode signal that is linked with the play position of the project currently loaded. Typically, this tells another device the exact SMPTE location of Cubase at any time, allowing it to lock to Cubase through this synchronization signal.

Because this plug-in is not really an effect, using it on a two-output system is useless because timecode is not what you could call «a pleasant sound.» Because it uses an audio output to carry its signal, you need to use an audio output on your sound card that you don’t use for anything else, or at least one channel (left or right) that you can spare for this signal. Placing the SMPTE Generator on an empty audio track is also necessary because you do not want to process this signal in any way, or the information the signal contains will be compromised.

How To

To use the SMPTE Generator plug-in:

-

Create a new audio track.

-

Open the Track Inserts section in the Inspector area.

-

From the Plug-ins Selection drop-down menu, select the SMPTE Generator.

-

Expand the audio channel section in the Inspector area.

-

Assign the plug-in to a bus that doesn’t contain any other audio signal. If you don’t have an unused bus, see if you can use one side in a left/right setup and then pan the plug-in on one side and whatever was assigned to that bus to the other side. For example, use a bass on the left and the SMPTE Generator on the right.

-

Click the Edit button to access its panel (see Figure 14.1).

Figure 14.1. The SMPTE Generator panel.

-

Make sure the Framerate field displays the same frame rate as your project. You can access your Project Setup dialog box by pressing the Shift+S keys to verify if this is the case. Otherwise, set the Framerate field to the appropriate setting.

-

Make the connections between the output to which the plug-in is assigned and the receiving device.

-

Click the Generate button to start sending timecode. This step verifies if the signal is connected properly to the receiving device.

-

Adjust the level in either the audio channel containing the plug-in or on the receiving device’s end. This receiving device should not receive a distorted signal to lock properly.

-

After you’ve made these adjustments, click the Link button in the Plug-in Information panel.

-

Start the playback of your project to lock the SMPTE Generator, the project, and the receiving device together.

MIDI Clock

MIDI Clock is a tempo-based synchronization signal used to synchronize two or more MIDI devices together with a beats-per-minute (BPM) guide track. As you can see, this is different than a timecode because it does not refer to a real-time address (hours: minutes: seconds: frames). In this case, it sends 24 evenly spaced MIDI Clocks per quarter note. So, at a speed of 60 BPM, it sends 1,440 MIDI Clocks per minute (one every 41.67 milliseconds), whereas at a speed of 120 BPM, it sends double that amount (one every 20.83 milliseconds ). Because it is tempo-based, the MIDI Clock rate changes to follow the tempo of the master tempo source.

When a sender sends a MIDI Clock signal, it sends a MIDI Start message to tell its receiver(s) to start playing a sequence at the speed or tempo set in the sender’s sequence. When the sender sends a MIDI End message, the receiver stops playing a sequence. Up until this point, all the receiver can do is start and stop playing MIDI when it receives these messages. If you want to tell the receiver sequence where to start, the MIDI Clock has to send what is called a Song Position Pointer message , telling the receiver the location of the sender’s song position. It uses the MIDI data to count the position where the MIDI Start message is at in relation to the sender.

Using MIDI Clock should be reserved for use between MIDI devices only, not for audio. As soon as you add digital audio or video, you should avoid using MIDI Clock because it is not well-suited for these purposes. Although it keeps a good synchronization between similar MIDI devices, the audio requires much greater precision. Video, on the other hand, works with time-based events, which do not translate well in BPM.

MIDI Machine Control

Another type of MIDI-related synchronization is the MIDI Machine Control (MMC). The MMC protocol uses System Exclusive messages over a MIDI cable to remotely control hard disk recording systems and other machines used for recording or playback. Many MIDI-enabled devices support this protocol.

MMC sends MIDI to a device, giving it commands such as play, stop, rewind, go to a specific location, punch-in, and punch-out on a specific track.

To make use of MMC in a setup in which you are using a multitrack tape recorder and a sequencer, you need to have a timecode (SMPTE) track sending timecode to a SMPTE/MTC converter. Then you send the converted MTC to Cubase so that it can stay in sync with the multitrack recorder. Both devices are also connected through MIDI cables. It is the multitrack that controls Cubase’s timing, not vice versa. Cubase, in return, can transmit MMC messages through its MIDI connection with the multitrack, which is equipped with a MIDI interface. These MMC messages tell the multitrack to rewind, fast forward, and so on. When you click Play in Cubase, it tells the multitrack to go to the position at which playback in Cubase’s project begins. When the multitrack reaches this position, it starts playing the tape back. After it starts playing, it then sends timecode to Cubase, to which it then syncs.

Digital Clock

The digital clock is another way to synchronize two or more devices together by using the sampling frequency of the sender device as a reference. This type of synchronization is often used with MTC in a music application such as Cubase to lock both audio sound card and MIDI devices with video devices. In this case, the sender device is the sound card. This is by far the most precise synchronization mechanism discussed here. Because it uses the sampling frequency of your sound card, it is precise to 1/44,100th of a second when you are using a 44.1 kH sampling frequency (or 0.02 milliseconds). Compare this with the precision of SMPTE timecode (around 33 milliseconds at 30 fps) and MIDI Clock (41.67 milliseconds at 120 BPM), and you quickly realize that this synchronization is very accurate.

When you make a digital transfer between two digital devices, the digital clock of the sender device is sent to the receiver device, making sure that every bit of the digital audio from the sender device fits with the receiver device. Failure to do so results in signal errors and will lead to signal degradation. When a receiver device receives a Word Clock (a type of digital clock) from its sender, it replaces its own clock with the one provided by this sender.

A digital clock can be transmitted on one of these cables:

-

S/PDIF (Sony/Phillips Digital InterFace). This format is probably the most common way to connect two digital devices together. Although this type of connection transmits digital clock information, it is usually referred to by its name rather than Word Clock. S/PDIF connectors have RCA connectors at each end and carry digital audio information with embedded digital audio clock information. You can transmit mono or stereo audio information on a single S/PDIF connection.

-

AES/EBU (Audio Engineering Society/European Broadcast Union). This is another very common, yet not as popular type of digital connector used to transfer digital information from one device to another. AES/EBU uses an XLR connector at each end of the cable; like the S/PDIF format, it carries the digital audio clock embedded in its data stream. You can also transmit mono or stereo audio information on this type of connection. Because this type of connection uses XLR connectors, it is less susceptible to creating clicks and pops when you connect them, but because they are more expensive, you won’t find them on low-cost equipment.

-

ADAT (Alesis Digital Audio Technology). This is a proprietary format developed by Alesis that carries up to eight separate digital audio signals and Word Clock information over a single-wire, fiber- optic cable. Most sound cards do not provide ADAT connectors on them, but if yours does, use it to send and receive digital clock information from and to an ADAT compatible device.

-

TDIF (Tascam Digital InterFace). This is a proprietary format develop by Tascam that also provides eight channels of digital audio in both directions, with up to 24-bit resolution. It also carries clocking signals that are used for synchronizing the transmission and reception of the audio; however, it does not contain Word Clock information, so you typically need to connect TDIF cables along with Word Clock cables (see below) if you want to lock two digital audio devices using this type of connection.

-

Word Clock. A digital clock is called Word Clock when it is sent over its own cable. Because Word Clock signals contain high frequencies, they are usually transmitted on 75-ohm coaxial cables for reliability. Usually, a coaxial BNC connector is used for Word Clock transfers.

To be able to transfer digital audio information in sync from one digital device to another, all devices have to support the sender’s sampling rate. This is particularly important when using sampling frequencies other than 44.1 or 48 kH, since those are pretty standard on most digital audio devices.

When synchronizing two digital audio devices together, the digital clock might not be the only synchronization clock needed. If you are working with another digital hard disk recorder or multitrack analog tape recorder, you need to send transport controls to and from these devices along with the timing position generated by this digital clock. This is when you have to lock both the digital clock and timecode together. Avoid using MIDI Clock at all costs when synchronizing with digital audio. The next section discusses different possibilities and how to set up Cubase to act as a sender or a receiver in the situations described previously.

When doing digital transfers between a digital multitrack tape and Cubase, it is important that both the Word Clock (digital clock) information and the timecode information be correlated to ensure a no-loss transfer and that for every bit on one end, there’s a corresponding bit on the other. This high-precision task can be performed through ASIO Position Protocol (APP).

APP uses the ASIO driver provided for your sound card and a compatible APP digital device, such as Alesis’ ADAT. In this type of setup, the ADAT provides the master (sender) Word Clock and the timecode information to Cubase. The ASIO 2.0 compatible driver of your sound card simply follows this information and stays accurate to the last sample.