In grammar, a part of speech or part-of-speech (abbreviated as POS or PoS, also known as word class[1] or grammatical category[2]) is a category of words (or, more generally, of lexical items) that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are assigned to the same part of speech generally display similar syntactic behavior (they play similar roles within the grammatical structure of sentences), sometimes similar morphological behavior in that they undergo inflection for similar properties and even similar semantic behavior. Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, and determiner.

Other terms than part of speech—particularly in modern linguistic classifications, which often make more precise distinctions than the traditional scheme does—include word class, lexical class, and lexical category. Some authors restrict the term lexical category to refer only to a particular type of syntactic category; for them the term excludes those parts of speech that are considered to be function words, such as pronouns. The term form class is also used, although this has various conflicting definitions.[3] Word classes may be classified as open or closed: open classes (typically including nouns, verbs and adjectives) acquire new members constantly, while closed classes (such as pronouns and conjunctions) acquire new members infrequently, if at all.

Almost all languages have the word classes noun and verb, but beyond these two there are significant variations among different languages.[4] For example:

- Japanese has as many as three classes of adjectives, where English has one.

- Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese have a class of nominal classifiers.

- Many languages do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, or between adjectives and verbs (see stative verb).

Because of such variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, analysis of parts of speech must be done for each individual language. Nevertheless, the labels for each category are assigned on the basis of universal criteria.[4]

History[edit]

The classification of words into lexical categories is found from the earliest moments in the history of linguistics.[5]

India[edit]

In the Nirukta, written in the 6th or 5th century BCE, the Sanskrit grammarian Yāska defined four main categories of words:[6]

- नाम nāma – noun (including adjective)

- आख्यात ākhyāta – verb

- उपसर्ग upasarga – pre-verb or prefix

- निपात nipāta – particle, invariant word (perhaps preposition)

These four were grouped into two larger classes: inflectable (nouns and verbs) and uninflectable (pre-verbs and particles).

The ancient work on the grammar of the Tamil language, Tolkāppiyam, argued to have been written around 2nd century CE,[7] classifies Tamil words as peyar (பெயர்; noun), vinai (வினை; verb), idai (part of speech which modifies the relationships between verbs and nouns), and uri (word that further qualifies a noun or verb).[8]

Western tradition[edit]

A century or two after the work of Yāska, the Greek scholar Plato wrote in his Cratylus dialogue, «sentences are, I conceive, a combination of verbs [rhêma] and nouns [ónoma]».[9] Aristotle added another class, «conjunction» [sýndesmos], which included not only the words known today as conjunctions, but also other parts (the interpretations differ; in one interpretation it is pronouns, prepositions, and the article).[10]

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, grammarians had expanded this classification scheme into eight categories, seen in the Art of Grammar, attributed to Dionysius Thrax:[11]

- ‘Name’ (ónoma) translated as «Noun«: a part of speech inflected for case, signifying a concrete or abstract entity. It includes various species like nouns, adjectives, proper nouns, appellatives, collectives, ordinals, numerals and more.[12]

- Verb (rhêma): a part of speech without case inflection, but inflected for tense, person and number, signifying an activity or process performed or undergone

- Participle (metokhḗ): a part of speech sharing features of the verb and the noun

- Article (árthron): a declinable part of speech, taken to include the definite article, but also the basic relative pronoun

- Pronoun (antōnymíā): a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person

- Preposition (próthesis): a part of speech placed before other words in composition and in syntax

- Adverb (epírrhēma): a part of speech without inflection, in modification of or in addition to a verb, adjective, clause, sentence, or other adverb

- Conjunction (sýndesmos): a part of speech binding together the discourse and filling gaps in its interpretation

It can be seen that these parts of speech are defined by morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria.

The Latin grammarian Priscian (fl. 500 CE) modified the above eightfold system, excluding «article» (since the Latin language, unlike Greek, does not have articles) but adding «interjection».[13][14]

The Latin names for the parts of speech, from which the corresponding modern English terms derive, were nomen, verbum, participium, pronomen, praepositio, adverbium, conjunctio and interjectio. The category nomen included substantives (nomen substantivum, corresponding to what are today called nouns in English), adjectives (nomen adjectivum) and numerals (nomen numerale). This is reflected in the older English terminology noun substantive, noun adjective and noun numeral. Later[15] the adjective became a separate class, as often did the numerals, and the English word noun came to be applied to substantives only.

Classification[edit]

Works of English grammar generally follow the pattern of the European tradition as described above, except that participles are now usually regarded as forms of verbs rather than as a separate part of speech, and numerals are often conflated with other parts of speech: nouns (cardinal numerals, e.g., «one», and collective numerals, e.g., «dozen»), adjectives (ordinal numerals, e.g., «first», and multiplier numerals, e.g., «single») and adverbs (multiplicative numerals, e.g., «once», and distributive numerals, e.g., «singly»). Eight or nine parts of speech are commonly listed:

- noun

- verb

- adjective

- adverb

- pronoun

- preposition

- conjunction

- interjection

- article* or (more recently) determiner

Additionally, there are other parts of speech including particles (yes, no)[a] and postpositions (ago, notwithstanding) although many fewer words are in these categories.

Some traditional classifications consider articles to be adjectives, yielding eight parts of speech rather than nine. And some modern classifications define further classes in addition to these. For discussion see the sections below.

The classification below, or slight expansions of it, is still followed in most dictionaries:

- Noun (names)

- a word or lexical item denoting any abstract (abstract noun: e.g. home) or concrete entity (concrete noun: e.g. house); a person (police officer, Michael), place (coastline, London), thing (necktie, television), idea (happiness), or quality (bravery). Nouns can also be classified as count nouns or non-count nouns; some can belong to either category. The most common part of speech; they are called naming words.

- Pronoun (replaces or places again)

- a substitute for a noun or noun phrase (them, he). Pronouns make sentences shorter and clearer since they replace nouns.

- Adjective (describes, limits)

- a modifier of a noun or pronoun (big, brave). Adjectives make the meaning of another word (noun) more precise.

- Verb (states action or being)

- a word denoting an action (walk), occurrence (happen), or state of being (be). Without a verb, a group of words cannot be a clause or sentence.

- Adverb (describes, limits)

- a modifier of an adjective, verb, or another adverb (very, quite). Adverbs make language more precise.

- Preposition (relates)

- a word that relates words to each other in a phrase or sentence and aids in syntactic context (in, of). Prepositions show the relationship between a noun or a pronoun with another word in the sentence.

- Conjunction (connects)

- a syntactic connector; links words, phrases, or clauses (and, but). Conjunctions connect words or group of words

- Interjection (expresses feelings and emotions)

- an emotional greeting or exclamation (Huzzah, Alas). Interjections express strong feelings and emotions.

- Article (describes, limits)

- a grammatical marker of definiteness (the) or indefiniteness (a, an). The article is not always listed among the parts of speech. It is considered by some grammarians to be a type of adjective[16] or sometimes the term ‘determiner’ (a broader class) is used.

English words are not generally marked as belonging to one part of speech or another; this contrasts with many other European languages, which use inflection more extensively, meaning that a given word form can often be identified as belonging to a particular part of speech and having certain additional grammatical properties. In English, most words are uninflected, while the inflected endings that exist are mostly ambiguous: -ed may mark a verbal past tense, a participle or a fully adjectival form; -s may mark a plural noun, a possessive noun, or a present-tense verb form; -ing may mark a participle, gerund, or pure adjective or noun. Although -ly is a frequent adverb marker, some adverbs (e.g. tomorrow, fast, very) do not have that ending, while many adjectives do have it (e.g. friendly, ugly, lovely), as do occasional words in other parts of speech (e.g. jelly, fly, rely).

Many English words can belong to more than one part of speech. Words like neigh, break, outlaw, laser, microwave, and telephone might all be either verbs or nouns. In certain circumstances, even words with primarily grammatical functions can be used as verbs or nouns, as in, «We must look to the hows and not just the whys.» The process whereby a word comes to be used as a different part of speech is called conversion or zero derivation.

Functional classification[edit]

Linguists recognize that the above list of eight or nine word classes is drastically simplified.[17] For example, «adverb» is to some extent a catch-all class that includes words with many different functions. Some have even argued that the most basic of category distinctions, that of nouns and verbs, is unfounded,[18] or not applicable to certain languages.[19][20] Modern linguists have proposed many different schemes whereby the words of English or other languages are placed into more specific categories and subcategories based on a more precise understanding of their grammatical functions.

Common lexical category set defined by function may include the following (not all of them will necessarily be applicable in a given language):

- Categories that will usually be open classes:

- adjectives

- adverbs

- nouns

- verbs (except auxiliary verbs)

- interjections

- Categories that will usually be closed classes:

- auxiliary verbs

- clitics

- coverbs

- conjunctions

- determiners (articles, quantifiers, demonstrative adjectives, and possessive adjectives)

- particles

- measure words or classifiers

- adpositions (prepositions, postpositions, and circumpositions)

- preverbs

- pronouns

- contractions

- cardinal numbers

Within a given category, subgroups of words may be identified based on more precise grammatical properties. For example, verbs may be specified according to the number and type of objects or other complements which they take. This is called subcategorization.

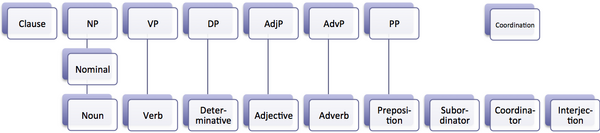

Many modern descriptions of grammar include not only lexical categories or word classes, but also phrasal categories, used to classify phrases, in the sense of groups of words that form units having specific grammatical functions. Phrasal categories may include noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP) and so on. Lexical and phrasal categories together are called syntactic categories.

Open and closed classes[edit]

Word classes may be either open or closed. An open class is one that commonly accepts the addition of new words, while a closed class is one to which new items are very rarely added. Open classes normally contain large numbers of words, while closed classes are much smaller. Typical open classes found in English and many other languages are nouns, verbs (excluding auxiliary verbs, if these are regarded as a separate class), adjectives, adverbs and interjections. Ideophones are often an open class, though less familiar to English speakers,[21][22][b] and are often open to nonce words. Typical closed classes are prepositions (or postpositions), determiners, conjunctions, and pronouns.[24]

The open–closed distinction is related to the distinction between lexical and functional categories, and to that between content words and function words, and some authors consider these identical, but the connection is not strict. Open classes are generally lexical categories in the stricter sense, containing words with greater semantic content,[25] while closed classes are normally functional categories, consisting of words that perform essentially grammatical functions. This is not universal: in many languages verbs and adjectives[26][27][28] are closed classes, usually consisting of few members, and in Japanese the formation of new pronouns from existing nouns is relatively common, though to what extent these form a distinct word class is debated.

Words are added to open classes through such processes as compounding, derivation, coining, and borrowing. When a new word is added through some such process, it can subsequently be used grammatically in sentences in the same ways as other words in its class.[29] A closed class may obtain new items through these same processes, but such changes are much rarer and take much more time. A closed class is normally seen as part of the core language and is not expected to change. In English, for example, new nouns, verbs, etc. are being added to the language constantly (including by the common process of verbing and other types of conversion, where an existing word comes to be used in a different part of speech). However, it is very unusual for a new pronoun, for example, to become accepted in the language, even in cases where there may be felt to be a need for one, as in the case of gender-neutral pronouns.

The open or closed status of word classes varies between languages, even assuming that corresponding word classes exist. Most conspicuously, in many languages verbs and adjectives form closed classes of content words. An extreme example is found in Jingulu, which has only three verbs, while even the modern Indo-European Persian has no more than a few hundred simple verbs, a great deal of which are archaic. (Some twenty Persian verbs are used as light verbs to form compounds; this lack of lexical verbs is shared with other Iranian languages.) Japanese is similar, having few lexical verbs.[30] Basque verbs are also a closed class, with the vast majority of verbal senses instead expressed periphrastically.

In Japanese, verbs and adjectives are closed classes,[31] though these are quite large, with about 700 adjectives,[32][33] and verbs have opened slightly in recent years. Japanese adjectives are closely related to verbs (they can predicate a sentence, for instance). New verbal meanings are nearly always expressed periphrastically by appending suru (する, to do) to a noun, as in undō suru (運動する, to (do) exercise), and new adjectival meanings are nearly always expressed by adjectival nouns, using the suffix -na (〜な) when an adjectival noun modifies a noun phrase, as in hen-na ojisan (変なおじさん, strange man). The closedness of verbs has weakened in recent years, and in a few cases new verbs are created by appending -ru (〜る) to a noun or using it to replace the end of a word. This is mostly in casual speech for borrowed words, with the most well-established example being sabo-ru (サボる, cut class; play hooky), from sabotāju (サボタージュ, sabotage).[34] This recent innovation aside, the huge contribution of Sino-Japanese vocabulary was almost entirely borrowed as nouns (often verbal nouns or adjectival nouns). Other languages where adjectives are closed class include Swahili,[28] Bemba, and Luganda.

By contrast, Japanese pronouns are an open class and nouns become used as pronouns with some frequency; a recent example is jibun (自分, self), now used by some young men as a first-person pronoun. The status of Japanese pronouns as a distinct class is disputed,[by whom?] however, with some considering it only a use of nouns, not a distinct class. The case is similar in languages of Southeast Asia, including Thai and Lao, in which, like Japanese, pronouns and terms of address vary significantly based on relative social standing and respect.[35]

Some word classes are universally closed, however, including demonstratives and interrogative words.[35]

See also[edit]

- Part-of-speech tagging

- Sliding window based part-of-speech tagging

Notes[edit]

- ^ Yes and no are sometimes classified as interjections.

- ^ Ideophones do not always form a single grammatical word class, and their classification varies between languages, sometimes being split across other word classes. Rather, they are a phonosemantic word class, based on derivation, but may be considered part of the category of «expressives»,[21] which thus often form an open class due to the productivity of ideophones. Further, «[i]n the vast majority of cases, however, ideophones perform an adverbial function and are closely linked with verbs.»[23]

References[edit]

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2007). «Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. Wiley. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00030.x. ISSN 1749-818X. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Payne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: a guide for field linguists. Cambridge. ISBN 9780511805066.

- ^ John Lyons, Semantics, CUP 1977, p. 424.

- ^ a b Kroeger, Paul (2005). Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-521-01653-7.

- ^ Robins RH (1989). General Linguistics (4th ed.). London: Longman.

- ^

Bimal Krishna Matilal (1990). The word and the world: India’s contribution to the study of language (Chapter 3). - ^ Mahadevan, I. (2014). Early Tamil Epigraphy — From the Earliest Times to the Sixth century C.E., 2nd Edition. p. 271.

- ^

Ilakkuvanar S (1994). Tholkappiyam in English with critical studies (2nd ed.). Educational Publisher. - ^ Cratylus 431b

- ^ The Rhetoric, Poetic and Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, translated by Thomas Taylor, London 1811, p. 179.

- ^ Dionysius Thrax. τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), ια´ περὶ λέξεως (11. On the word):

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

λόγος δέ ἐστι πεζῆς λέξεως σύνθεσις διάνοιαν αὐτοτελῆ δηλοῦσα.

τοῦ δὲ λόγου μέρη ἐστὶν ὀκτώ· ὄνομα, ῥῆμα,

μετοχή, ἄρθρον, ἀντωνυμία, πρόθεσις, ἐπίρρημα, σύνδεσμος. ἡ γὰρ προσηγορία ὡς εἶδος τῶι ὀνόματι ὑποβέβληται. - A word is the smallest part of organized speech.

Speech is the putting together of an ordinary word to express a complete thought.

The class of word consists of eight categories: noun, verb,

participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction. A common noun in form is classified as a noun.

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

- ^ The term ‘onoma’ at Dionysius Thrax, Τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), 14. Περὶ ὀνόματος translated by Thomas Davidson, On the noun

- καὶ αὐτὰ εἴδη προσαγορεύεται· κύριον, προσηγορικόν, ἐπίθετον, πρός τι ἔχον, ὡς πρός τι ἔχον, ὁμώνυμον, συνώνυμον, διώνυμον, ἐπώνυμον, ἐθνικόν, ἐρωτηματικόν, ἀόριστον, ἀναφορικὸν ὃ καὶ ὁμοιωματικὸν καὶ δεικτικὸν καὶ ἀνταποδοτικὸν καλεῖται, περιληπτικόν, ἐπιμεριζόμενον, περιεκτικόν, πεποιημένον, γενικόν, ἰδικόν, τακτικόν, ἀριθμητικόν, ἀπολελυμένον, μετουσιαστικόν.

- also called Species: proper, appellative, adjective, relative, quasi-relative, homonym, synonym, pheronym, dionym, eponym, national, interrogative, indefinite, anaphoric (also called assimilative, demonstrative, and retributive), collective, distributive, inclusive, onomatopoetic, general, special, ordinal, numeral, participative, independent.

- ^ [penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Quintilian/Institutio_Oratoria/1B*.html This translation of Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria reads: «Our own language (Note: i.e. Latin) dispenses with the articles (Note: Latin doesn’t have articles), which are therefore distributed among the other parts of speech. But interjections must be added to those already mentioned.»]

- ^ «Quintilian: Institutio Oratoria I».

- ^ See for example Beauzée, Nicolas, Grammaire générale, ou exposition raisonnée des éléments nécessaires du langage (Paris, 1767), and earlier Jakob Redinger, Comeniana Grammatica Primae Classi Franckenthalensis Latinae Scholae destinata … (1659, in German and Latin).

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar by Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker & Edmund Weine. OUP Oxford 2014. Page 35.

- ^ Zwicky, Arnold (30 March 2006). «What part of speech is «the»«. Language Log. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

…the school tradition about parts of speech is so desperately impoverished

- ^ Hopper, P; Thompson, S (1985). «The Iconicity of the Universal Categories ‘Noun’ and ‘Verbs’«. In John Haiman (ed.). Typological Studies in Language: Iconicity and Syntax. Vol. 6. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 151–183.

- ^ Launey, Michel (1994). Une grammaire omniprédicative: essai sur la morphosyntaxe du nahuatl classique. Paris: CNRS Editions.

- ^ Broschart, Jürgen (1997). «Why Tongan does it differently: Categorial Distinctions in a Language without Nouns and Verbs». Linguistic Typology. 1 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1515/lity.1997.1.2.123. S2CID 121039930.

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 99

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 179

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 181

- ^ «Sample Entry: Function Words / Encyclopedia of Linguistics».

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-470-65531-3.

- ^ Dixon, Robert M. W. (1977). «Where Have all the Adjectives Gone?». Studies in Language. 1: 19–80. doi:10.1075/sl.1.1.04dix.

- ^ Adjective classes: a cross-linguistic typology, Robert M. W. Dixon, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, OUP Oxford, 2006

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 97

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2014). Language Development. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-133-93909-2.

- ^ Categorial Features: A Generative Theory of Word Class Categories, «p. 54».

- ^ Dixon 1977, p. 48.

- ^ The Typology of Adjectival Predication, Harrie Wetzer, p. 311

- ^ The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 96

- ^ Adam (2011-07-18). «Homage to る(ru), The Magical Verbifier».

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 98

External links[edit]

Media related to Parts of speech at Wikimedia Commons

- The parts of speech

- Guide to Grammar and Writing

- Martin Haspelmath. 2001. «Word Classes and Parts of Speech.» In: Baltes, Paul B. & Smelser, Neil J. (eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Pergamon, 16538–16545. (PDF)

Содержание

Согласно определённым закономерностям в изменении формы слов при их употреблении в предложении, слова подразделяются на определённые категории, которые традиционно называются части речи (parts of speech [pʌrts əv spɪ:tʃ]). Части речи являются объектом изучения в морфологии.

Термин «часть речи» является традиционным и используется в грамматиках различных языков ещё с тех пор, как были составлены классические грамматики греческого языка, которые послужили образцом для написания грамматик для других языков. В современных же грамматиках, наряду с понятием части речи, часто используется термин «классы слов» (word classes [wə:rd klʌsɪz]).

В основе разделения слов по классам лежат три группы признаков:

-

основываясь на морфологических свойствах слова (форма слова и способы её изменения):

-

-

основываясь на синтаксической функции слова (способе соединения слов в словосочетаниях и предложениях):

-

Личные формы глагола, инфинитив, герундий, причастие называют действие или состояние, но выполняют различные синтаксические функции в предложении, в классической грамматике английского языка, основываясь на лексическом значении и морфологических признаках, эти классы слов принято объединять в один класс — глаголы. Инфинитив, герундий и причастие при этом выделяются как неличные формы глагола.

Местоимения и числительные могут выполнять различные синтаксические функции: употребляться вместо существительного или быть определителем к существительному.

Выделение определённых классов слов является не однозначным, и в различных грамматиках могут выделяться разные классы слов и на отличающихся принципах.

Самостоятельные и служебные слова (Independent and Function Words)

За исключением междометий, классы слов разделяют на две группы, это самостоятельные и служебные классы слов.

Самостоятельные слова могут самостоятельно выступать как член предложения. Предложение невозможно построить без самостоятельных слов, так как они называют предметы, действия, состояния, а также их различные признаки, по сему эти слова также называют знаменательными.

Группа служебных слов не называют ни предметов, ни действий, ни состояний, ни их признаков, и не могут самостоятельно выступать как член предложения, а только выражают отношения между самостоятельными классами слов. Служебные слова обслуживают самостоятельные слова, из них нельзя составить предложения. К классу служебных слов относят: предлоги, союзы, частицы.

Исключительность междометий заключается в том, что их функция не сводится к несению какого-либо лексического значения или выражению отношений между словами, междометия выражают эмоциональную составляющую в предложении.

The

parts of speech are classes of words, all the members of these

classes having certain characteristics in common which distinguish

them fr om the members of other classes. The problem of word

classification into parts of speech still remains one of the most

controversial problems in modern linguistics. The attitude of

grammarians with regard to parts of speech and the basis of their

classification varied a good deal at different times. Only in English

grammarians have been vacillating between 3 and 13 parts of speech.

There

are four approaches to the problem:

-

Classical

(logical-inflectional) -

Functional

-

Distributional

-

Complex

The

classical

parts of speech theory goes back to ancient times. It is based on

Latin grammar. According to the Latin classification of the parts of

speech all words were divided dichotomically into declinable

and

indeclinable

parts

of speech. This system was reproduced in the earliest English

grammars. The first of these groups, declinable words, included

nouns, pronouns, verbs and participles, the second – indeclinable

words – adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections. The

logical-inflectional classification is quite successful for Latin or

other languages with developed morphology and synthetic paradigms but

it cannot be applied to the English language because the principle of

declinability/indeclinability is not relevant for analytical

languages.

A

new approach to the problem was introduced in the XIX century by

Henry Sweet. He took into account the peculiarities of the English

language. This approach may be defined as functional.

He resorted to the functional features of words and singled out

nominative units and particles. To nominative

parts of speech belonged noun-words

(noun, noun-pronoun, noun-numeral, infinitive, gerund),

adjective-words

(adjective, adjective-pronoun, adjective-numeral, participles), verb

(finite verb, verbals – gerund, infinitive, participles), while

adverb,

preposition,

conjunction

and interjection

belonged to the group of particles.

However, though the criterion for classification was functional,

Henry Sweet failed to break the tradition and classified words into

those having morphological forms and lacking morphological forms, in

other words, declinable and indeclinable.

A distributional

approach

to

the parts to the parts of speech classification can be illustrated by

the classification introduced by Charles Fries. He wanted to avoid

the traditional terminology and establish a classification of words

based on distributive analysis, that is, the ability of words to

combine with other words of different types. At the same time, the

lexical meaning of words was not taken into account. According to

Charles Fries, the words in such sentences as 1. Woggles ugged

diggles; 2. Uggs woggled diggs; and 3. Woggs diggled uggles are quite

evident structural signals, their position and combinability are

enough to classify them into three word-classes. In this way, he

introduced four major classes

of words

and 15 form-classes.

Let us see how it worked. Three test frames

formed

the basis for his analysis:

Frame

A — The concert was good (always);

Frame B — The clerk remembered

the tax (suddenly);

Frame C – The team went there.

It

turned out that his four classes of words were practically the same

as traditional nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. What is really

valuable in Charles Fries’ classification is his investigation of

15 groups of function words (form-classes) because he was the first

linguist to pay attention to some of their peculiarities.

All

the classifications mentioned above appear to be one-sided because

parts of speech are discriminated on the basis of only one aspect of

the word: either its meaning or its form, or its function.

In

modern linguistics, parts of speech are discriminated according to

three criteria: semantic, formal and functional. This approach may be

defined as complex.

The semantic

criterion presupposes the grammatical meaning of the whole class of

words (general grammatical meaning). The formal

criterion

reveals paradigmatic properties: relevant grammatical categories, the

form of the words, their specific inflectional and derivational

features. The functional

criterion

concerns the syntactic function of words in the sentence and their

combinability. Thus, when characterizing any part of speech we are to

describe: a) its semantics; b) its morphological features; c) its

syntactic peculiarities.

The

linguistic evidence drawn fr om our grammatical study makes it

possible to divide all the words of the language into:

-

those

denoting things, objects, notions, qualities, etc. – words with

the corresponding references in the objective reality – notional

words; -

those

having no references of their own in the objective reality; most of

them are used only as grammatical means to form up and frame

utterances – function

words,

or grammatical

words.

It

is commonly recognized that the notional parts of speech are nouns,

pronouns, numerals, verbs, adjectives, adverbs; the functional parts

of speech are articles, particles, prepositions, conjunctions and

modal words.

The

division of language units into notion and function words reveals the

interrelation of lexical and grammatical types of meaning. In

notional words the lexical meaning is predominant. In function words

the grammatical meaning dominates over the lexical one. However, in

actual speech the border line between notional and function words is

not always clear cut. Some notional words develop the meanings

peculiar to function words — e.g. seminotional words – to

turn, to get, etc.

Notional

words constitute the bulk of the existing word stock while function

words constitute a smaller group of words. Although the number of

function words is limited (there are only about 50 of them in Modern

English), they are the most frequently used units.

Generally

speaking, the problem of words’ classification into parts of speech

is far fr om being solved. Some words cannot find their proper place.

The most striking example here is the class of adverbs. Some language

analysts call it a

ragbag, a dustbin

(Frank Palmer), Russian academician V.V.Vinogradov defined the class

of adverbs in the Russian language as мусорная

куча.

It can be explained by the fact that to the class of adverbs belong

those words that cannot find their place anywhere else. At the same

time, there are no grounds for grouping them together either.

Compare: perfectly

(She speaks English perfectly)

and

again

(He is here again).

Examples are numerous (all temporals). There are some words that do

not belong anywhere — e.g. after

all.

Speaking about after

all

it should be mentioned that this unit is quite often used by native

speakers, and practically never by our students. Some more striking

examples: anyway,

actually, in fact.

The problem is that if these words belong nowhere, there is no place

for them in the system of words, then how can we use them correctly?

What makes things worse is the fact that these words are devoid of

nominative power, and they have no direct equivalents in the

Ukrainian or Russian languages. Meanwhile, native speakers use these

words subconsciously, without realizing how they work.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

What is an adverb? What is a preposition? What is a…?

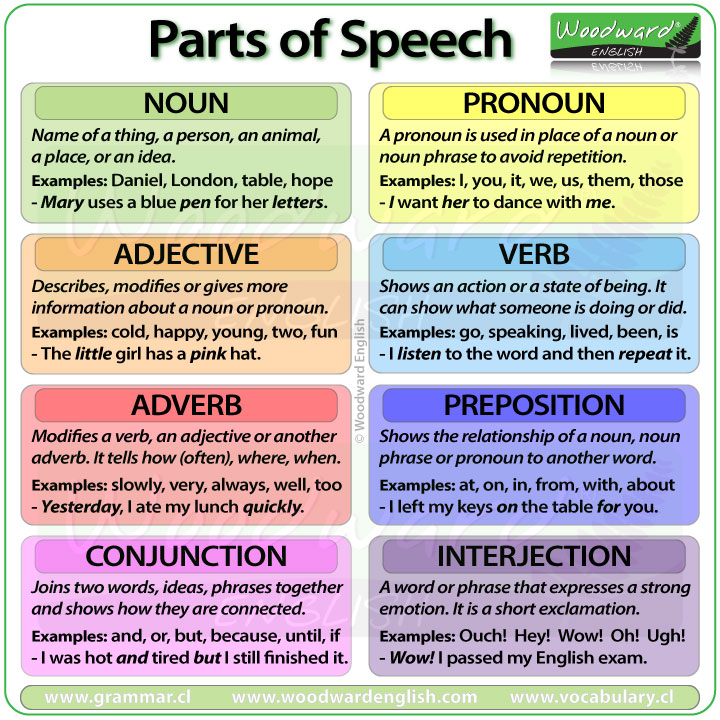

These are questions that students sometimes ask when a teacher is explaining a grammar point.

The different parts of speech (or all of those “grammar words” as some students call them) are important to know when learning English, or any other language.

In order to help solve doubts about what the different parts of speech are and what functions they have, I created a summary chart and a video explaining the main differences between each one.

Parts of Speech in English – ESL Video

In our ESL video, we look at the eight parts of speech in traditional English grammar.

These parts of speech, sometimes called word classes, include:

Nouns, Pronouns, Adjectives, Verbs, Adverbs, Prepositions, Conjunctions, and Interjections.

We give an explanation of how each word class is used and have included example sentences. For some of the parts of speech we also look at sub-classes such as subject pronouns and possessive pronouns, the different types of adverbs such as adverbs of manner, adverbs of frequency, etc.

In the final section we talk about how some teachers sometimes include a 9th part of speech which can be either Articles or Determiners. Again, we include examples.

This ESL video to ideal to give students a general overview of the different parts of speech in English.

Summary Chart

English Teacher Resource

We have created the following summary charts that can be used in the classroom or for homeschooling:

Forward to Navigation

Posted: Jan 04, 2007 12:01;

Last Modified: Jan 25, 2014 14:01

Words are different from each other in meaning—car and unwelcome mean different things, after all.

But they can also differ from each other in more than meaning: they can also differ in the way they are used in sentences.

Thus sentences can be about a word like car more easily than they can be about a word like unwelcome:

- Cars are on the road

- *Unwelcomes are on the road1

With a word like car, we also can talk about one or more examples: a car is here, cars are here. We can describe its qualities using other words like red, fast, or good: “red cars are here”, “fast cars are here”, “good cars are here”. And a word like car can be said to possess things: the car’s tires, cars’ steering wheels

None of this is true of a word like unwelcome. But unwelcome can be used in ways a word like car cannot: it can be used to describe qualities of other words (The unwelcome news, This news was unwelcome, vs. *The car news or [*This news was car); it can be made more intense using words like very or really (it was very unwelcome, vs. *It was very car).

The real test, of course, is that the two words can’t be switched in a sentence. We couldn’t replace car with unwelcome in the example above, and it is impossible2 to replace unwelcome with car in this following sentence:

- That was really unwelcome news.

- That was really *car news.

It is possible, on the other hand, to replace car and unwelcome with other words, even if the meaning of the new words is nothing like that of the words they replace:

- Bartenders are on the road.

- That was really good news.

So why can car be replaced by bartender and not unwelcome or good? And why can unwelcome be replaced by good but not bartender or car?

The answer is that car and bartender, on the one hand, and unwelcome and good, on the other, are different types of words. As we will learn, car and bartender show in normal use most of the properties we associate with nouns while unwelcome and good show in normal use most of the properties we associate with adjectives. The fact that you can replace car with bartender and unwelcome with good shows that you can replace nouns with nouns and adjectives with adjectives more easily than you can replace words of one type with words of a different type.

This tutorial explores this property in greater depth. Traditionally, word classes have been distinguished on semantic grounds (e.g. “Nouns are the names of person places or things”; “verbs are action words”). As this tutorial will demosntrate, these traditional definitions, while not usually wrong, are often quite ambiguous. This is because the class a word belongs to is largely a question of syntax rather than meaning, especially given the ease with which English can move words from one class to another without any change in morphological form.

By the end of this tutorial you should be able to distinguish among word classes confidently.

Previous: Inflections (inflectional morphology) | Next: Grammatical relations

Words and Phrases

If we continue testing like this, we will also soon discover not only that some words are more easily exchanged with one other than with others, but also that individual words can be used to replace entire groups of closely connected words (and vice versa). For example, the word bartenders can replace more than cars in the following sentences; it also can replace entire groups of closely connected words involving cars—groups like the cars, the blue cars, and even the blue cars that sold so well last year:

- Cars are on the road

- The cars are on the road

- The blue cars are on the road

- The blue cars that sold so well last year are on the road

- Bartenders are on the road.

On the other hand, we still can’t use unwelcome to replace cars:

- Cars are on the road.

- *Unwelcomes are on the road.

If we experiment, we will see that we can’t replace just any group of words using bartender: the words need to be somehow more closely related to each other than any other part of the sentence and involve a word like car. In the following sentence, for example, we can use bartenders to replace the blue cars, but not blue cars are on:

- The blue cars are on the road

- Bartenders are on the road

- The blue cars are on the road

- *The bartenders road3.

Clearly there is something about the words the blue cars that makes us think of them as being more closely connected to each other than to anything else in the sentence. And just as the fact that we can replace car with bartender but not unwelcome in the sentences above suggests that there must be something similar about car and bartender, so to the fact that we can use bartenders to replace cars and groups of closely related words like the cars or the blue cars suggests that there must be something similar about the single word cars and these particular combinations of words.

As we shall discover, combinations of closely connected words that behave in much the same way as individual words are known as Phrases. As we define the different types of words below, we will see that each type of word has an associated type of phrase to which many of the same rules apply. This principle will become very important when we come to talk about how sentences are made.

Open and Closed Word Classes

Another difference that separates words is the question of how easy or difficult it is to make up new examples. If I want to replace car or cars in the above sentences with a new word that I will make up myself—say slipshlup—I can do so very easily:

- Cars are on the road

- Slipshlups are on the road

- The cars are on the road

- The slipshlups are on the road

- The blue cars are on the road

- The blue slipshlups are on the road

- The blue cars that sold so well last year are on the road

- The blue slipshlups that sold so well last year are on the road

- Bartenders are on the road.

Likewise, it is not hard to make up a word like unwelcome. How about griopy?

- That was really unwelcome news.

- That was really griopy news.

But if it easy to make up new words parallel to cars and unwelcome, it is much harder—impossible, in fact—to make up replacements for words like the, and, but or he, she, and it. For example, try repeating the following sentence with the following made-up words: hin for the, roop for and, and fries for she.

- The cars and the boats were on the road, but they were not for sale, she said.

Doesn’t make much sense, does it?

The Parts of Speech/Word Classes

If we compare English words in the way discussed above3, we will discover that it is possible to divide words and closely associated groups of words like them into eight main types, known as the parts of speech or word classes (a minor ninth category contains interjections. like “oh dear!” and “damn!” and is not discussed further in this tutorial). We will also discover that these Word Classes themselves fall into two larger groups based on whether or not we can easily add new examples: the Open Class contains word classes that we easily can add to—nouns, adjectives, most types of verbs, and adverbs; the Closed or Structure Class contains words, like prepositions, pronouns, conjunctions, most determiners, and some adverbs, to which we can not add easily:

| Class | Word Class | Examples |

| Open Class | Nouns | car, bartender, experience |

| Adjectives | unwelcome, good, big, blue | |

| Verbs | run, glide, listen, jog | |

| Adverbs | quickly, well, sometimes, badly | |

| Closed Class | Determiners | the, this, mine, Susan’s |

| Prepositions | up, underneath, on, with | |

| Pronouns | I, they, mine, each, these | |

| Conjunctions | and, but, if, because |

Open Classes

Nouns and Noun Phrases

Nouns are naming words. Traditionally they are defined as the names of persons, places, and things, but their actual range is much broader: they can name ideas, moods, and feelings (e.g. neoconservatism, anger, and affection); actions (the hiking), or pretty much anything else known or unknown (e.g. Slipshlup, above).

Fortunately, given how hard it can be to define them by what they describe, nouns and noun phrases can be defined relatively easily by their form and the contexts in which they appear. In particular they show one or more of the following unique features:

- Nouns are the only words that use “apostrophe s” (i.e. ‘s or s’) to show possession. In the following sentence, we know that Dave, Neoconservatism, and anger are all nouns because they indicate possession by adding -‘s: Dave’s book, Neoconservatism’s origins, anger’s solution.

- Nouns are the only words that can be modified by adjectives: blue cars, unwelcome news, clever Sally.

- Nouns are the only words that can be made plural by adding -s: DVD : DVDs, cup : cups, theology : theologies.

- Nouns are the only words that can be pointed to by determiners. Determiners, as we will see below, are words such as the and a, that and this, and possessives such as his or Brigette’s that point out specific instances of a noun, e.g. the boat, a slipshlup, that hiking, Brigette’s DVD, his anger.

- Nouns and Noun Phrases are the only words that can be replaced by a pronoun: The deer grazed quietly at the side of the road : It grazed quietly at the side of the road

Other tests are not entirely exclusive, for example:

- Nouns and pronouns are the only words that can function as the subject of a sentence: The car ran through the red light : It ran through the red light.

It is important to realise in applying these tests that not all words will fit all categories. Some nouns do not form their plural with -s, for example: e.g. child : children; sheep : sheep. What is important is that one or more of these tests be true.

Verbs

Verbs are traditionally defined as “action words.” Even more than with nouns, however, this definition fails to cover more than a narrow range of possible examples or rule out obvious counter-examples. While some verbs do express action (e.g. she hit the wall with a hammer), others do not (e.g. I am the king, he knows his baseball). Moreover, actions can also be named by nouns: This hiking is very hard; I don’t like all this hitting).

Like nouns, verbs can be defined more accurately on grammatical criteria. Particularly useful ones include:

- Verbs are the only words that show tense (i.e. past or present): he loves cheesecake : he loved cheesecake; I drive fast : I drove fast.

- Verbs are the only words that indicate third person singular, present by adding -s at the end: I drive, he drives

- Verbs are the only words that can be made into participles (i.e. adjective forms) using the endings -ed, -en, or -ing: I love : loving : loved; They drive : driving : driven

Verb Phrases include the verb plus all objects and modifiers. These can get quite large. One test for some verb phrases is replacement by do in questions designed to be answered with “yes” or “no”.

- Bobbi loves getting presents in the morning, does she?

In asking the question “does she”, the speaker is summing up the whole idea “loves getting presents in the morning” by a single form of do. This shows that “loves getting presents in the morning” is a Verb Phrase.

Adjectives

Adjectives describe qualities to nouns. One easy test, though it is also true of adverbs, is placing very or really in front:

- Adjectives and adverbs are the only words that can be made more intense by adding very or really in front: the really fast car was very red

Here are some tests that are only true of adjectives:

- Adjectives are the only words that can have endings to indicate that something is more or most in relation to some quality: the fast car was red : the faster car was green : the fastest car was blue. Of course some adjectives don’t use -er and/or -est: more unwelcome not *unwelcomer; best nor goodest.

- Adjectives and adjective phrases are the only words that can appear between determiners (like the, a, or possessives) and nouns: the fast car, Dave’s really nice cake, a very sad clown.

Adverbs

Adverbs are traditionally described as words that modify verbs. In fact there are three different kinds of adverbs, each of which can be distinguished by context.

Intensifying adverbs

Intensifying adverbs are words like very that are used to qualify adjectives and other adverbs. They do not qualify verbs directly: his very angry cousin vs. *he very jumps. Some intensifying adverbs can be used with slightly different meaning to modify verbs: he skates really fast, he really skates.

Sentence adverbs

Sentence adverbs qualify sentences and clauses: Unfortunately, the boat sank; I don’t want to, however; then he knew for sure.

Verbal adverbs

Verbal adverbs qualify verbs: He jumped quickly, he wrote well. Like adjectives, they can be intensified by words like very: she drove very quickly, Beatrice cooks really well.

Closed class words

Determiners

Determiners are words that are used to point out specific instances of a noun. They include the articles (a, the), demonstratives (this/these, that/those), and all possessive nouns and pronouns (this means that a form like Dave’s in Dave’s book is both a noun and a determiner).

The test for determiners is very straightforward:

- Determiners precede nouns and any qualifying adjectives. The first word in each of the following phrases is a determiner: the book, the large book, Dave’s really ugly book, my car, my sister’s car (in this last example, both my and my sister’s are determiners: my points to sister and my sister’s points to car).

Prepositions

Prepositions serve to connect nouns or noun phrases (e.g. cars or the car) to a clause or sentence. Examples include up a mountain, down the street, with friends, beside him, without a wooden paddle.

In English, there are a relatively small number of simple prepositions, such as up, down, with. There are also a number of phrasal or compound prepositions, especially in spoken English: outside of the English, apart from Dave’s cat, round and round the mountain.

Many of the prepositions can be memorised. Otherwise, prepositions can be recognised by their syntactic context:

- Prepositions are always followed by noun phrases (i.e. nouns with any associated determiners and adjectives, or pronouns) that serve as their objects5.

Pronouns

Pronouns are words that can substitute for nouns or noun phrases. Examples include personal pronouns like she/her, I/me/my, they/them/their; demonstratives like this/these, that/those; and other forms, such as each, none, and one:

- My sister is here. She wants to talk to you.

- The green carrots are probably rotten. I wouldn’t eat them.

- My books are here. These over here are yours.

- The members of the committee were awstruck. None had expected this.

Because pronouns replace nouns, they can be identified using some of the same tests. In particular,

- Pronouns (with nouns) are the only words that can serve as the subject of a sentence: he ran the country; she scored five goals; it was hit by a train.

- Pronouns (with nouns) are the only words that can serve as the object of a verb or preposition: outside this, with him, she cut it.

- Pronouns (with nouns) are the only words that can take a possessive inflection—though unlike nouns, the possessive is never ‘s or s’ and rarely s: my books, your garage, her cannon, his snow shovel6.

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are used to join grammatical units. Unlike prepositions, which join nouns or noun phrases to sentences, conjunctions always join elements of a similar kind: nouns and noun phrases to other nouns and noun phrases, verbs to verbs, adjectives to adjectives: it is raining cats and dogs (noun to noun); I neither pushed nor pulled (verb to verb); I went out because he didn’t come in (clause to clause).

Exercises

(Click here for Answers)

The following exercises test you on your ability to apply the above material. The real test of your knowledge of grammar is not whether you are able to memorise terms and definitions, but whether you can supply examples and describe real-life sentences.

1. Place each word in the following sentence in its Word Class using the above tests. Which Word Class(es) is or are missing?:

Over the mountain lived a former mechanic. Suzy forgets his name.

2. When Hamlet says that bad acting “out-herods Herod” (Hamlet, III.ii), meaning to rage and rant, he is using a proper name for a verb. What tests can we use to show that out-herods is a verb?

3. Although it is impossible for individuals to create new Closed or Structure Class words, the English language has acquired new pronouns over the course of its history: the entire plural pronoun system they, them, their comes from Old Norse (the original English version was hie, hira and him); she is of unknown origin (the original was heo).

Can you suggest some reasons why it is possible for languages to add or change such words but not for individuals?

Notes

1 An asterisk (i.e. *) in front of a word or group of words means “This word or group of words is not something people would say”. An explanation mark (i.e. !) in front of a word or a group of words means “It is doubtful that this is something people would say” or “People might say this, but only in special circumstances”

2 “Impossible” may seem too definite at first. In fact it is almost always possible to think of a situation in which a grammatical rule might be shown to be wrong: for example, let’s say we were talking about a band called “The Unwelcome“—then they probably could replace car in our example sentences.

As a rule, however, you should always be suspicious of counter-examples that require you to create a “back-story” to explain the conditions under which an exception might work. The fact that you need a story to explain the context is evidence that the counter-example is very unusual in normal speech.

3 You could say “The bartenders’ road” or “The bartender’s road”, but that would not really count, since cars in the original sentence did not have an “apostrophe s.” In the starting sentence, cars was plural, not possessive or plural possessive.

4 Traditionally, students learned to categorise the parts of speech on the basis of meaning. For example, nouns were said to be “the name of a person, place, or thing,” while verbs were described as “action words.” While there is some truth to these definitions in many cases, the distinctions break down very easily in others. The fighting is a noun, even though it describes an action; is, on the other hand, is a verb, even though it describes a state.

Since words are a feature of grammar, the method used here attempts to identify them on the basis of their grammatical properties: the roles they can play in the sentence, the inflections they can take, how they can be converted from one part of speech to another.

5 “Always”, except in poetry, where they can sometimes follow the words they connect to the sentence.

6 This rule—pronouns never end in apostrophe -s—might be useful in helping you avoid the common stylistic/prescriptive grammar error of using it’s (actually the abbreviation for it is) in your writing instead of the possessive form, its. In speaking, of course, you can’t hear any difference.

Previous: Inflections (inflectional morphology)

Commenting is closed for this article.