Select your language

Suggested languages for you:

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmelden

Words don’t only mean something; they also do something. In the English language, words are grouped into word classes based on their function, i.e. what they do in a phrase or sentence. In total, there are nine word classes in English.

Word class meaning and example

All words can be categorised into classes within a language based on their function and purpose.

An example of various word classes is ‘The cat ate a cupcake quickly.’

-

The = a determiner

-

cat = a noun

-

ate = a verb

-

a = determiner

-

cupcake = noun

-

quickly = an adverb

Word class function

The function of a word class, also known as a part of speech, is to classify words according to their grammatical properties and the roles they play in sentences. By assigning words to different word classes, we can understand how they should be used in context and how they relate to other words in a sentence.

Each word class has its own unique set of characteristics and rules for usage, and understanding the function of word classes is essential for effective communication in English. Knowing our word classes allows us to create clear and grammatically correct sentences that convey our intended meaning.

Word classes in English

In English, there are four main word classes; nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. These are considered lexical words, and they provide the main meaning of a phrase or sentence.

The other five word classes are; prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These are considered functional words, and they provide structural and relational information in a sentence or phrase.

Don’t worry if it sounds a bit confusing right now. Read ahead and you’ll be a master of the different types of word classes in no time!

| All word classes | Definition | Examples of word classification |

| Noun | A word that represents a person, place, thing, or idea. | cat, house, plant |

| Pronoun | A word that is used in place of a noun to avoid repetition. | he, she, they, it |

| Verb | A word that expresses action, occurrence, or state of being. | run, sing, grow |

| Adjective | A word that describes or modifies a noun or pronoun. | blue, tall, happy |

| Adverb | A word that describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or other adverb. | quickly, very |

| Preposition | A word that shows the relationship between a noun or pronoun and other words in a sentence. | in, on, at |

| Conjunction | A word that connects words, phrases, or clauses. | and, or, but |

| Interjection | A word that expresses strong emotions or feelings. | wow, oh, ouch |

| Determiners | A word that clarifies information about the quantity, location, or ownership of the noun | Articles like ‘the’ and ‘an’, and quantifiers like ‘some’ and ‘all’. |

The four main word classes

In the English language, there are four main word classes: nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Let’s look at all the word classes in detail.

Nouns

Nouns are the words we use to describe people, places, objects, feelings, concepts, etc. Usually, nouns are tangible (touchable) things, such as a table, a person, or a building.

However, we also have abstract nouns, which are things we can feel and describe but can’t necessarily see or touch, such as love, honour, or excitement. Proper nouns are the names we give to specific and official people, places, or things, such as England, Claire, or Hoover.

Cat

House

School

Britain

Harry

Book

Hatred

‘My sister went to school.‘

Verbs

Verbs are words that show action, event, feeling, or state of being. This can be a physical action or event, or it can be a feeling that is experienced.

Lexical verbs are considered one of the four main word classes, and auxiliary verbs are not. Lexical verbs are the main verb in a sentence that shows action, event, feeling, or state of being, such as walk, ran, felt, and want, whereas an auxiliary verb helps the main verb and expresses grammatical meaning, such as has, is, and do.

Run

Walk

Swim

Curse

Wish

Help

Leave

‘She wished for a sunny day.’

Adjectives

Adjectives are words used to modify nouns, usually by describing them. Adjectives describe an attribute, quality, or state of being of the noun.

Long

Short

Friendly

Broken

Loud

Embarrassed

Dull

Boring

‘The friendly woman wore a beautiful dress.’

Adverbs

Adverbs are words that work alongside verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs. They provide further descriptions of how, where, when, and how often something is done.

Quickly

Softly

Very

More

Too

Loudly

‘The music was too loud.’

All of the above examples are lexical word classes and carry most of the meaning in a sentence. They make up the majority of the words in the English language.

The other five word classes

The other five remaining word classes are; prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These words are considered functional words and are used to explain grammatical and structural relationships between words.

For example, prepositions can be used to explain where one object is in relation to another.

Prepositions

Prepositions are used to show the relationship between words in terms of place, time, direction, and agency.

In

At

On

Towards

To

Through

Into

By

With

‘They went through the tunnel.’

Pronouns

Pronouns take the place of a noun or a noun phrase in a sentence. They often refer to a noun that has already been mentioned and are commonly used to avoid repetition.

Chloe (noun) → she (pronoun)

Chloe’s dog → her dog (possessive pronoun)

There are several different types of pronouns; let’s look at some examples of each.

- He, she, it, they — personal pronouns

- His, hers, its, theirs, mine, ours — possessive pronouns

- Himself, herself, myself, ourselves, themselves — reflexive pronouns

- This, that, those, these — demonstrative pronouns

- Anyone, somebody, everyone, anything, something — Indefinite pronouns

- Which, what, that, who, who — Relative pronouns

‘She sat on the chair which was broken.’

Determiners

Determiners work alongside nouns to clarify information about the quantity, location, or ownership of the noun. It ‘determines’ exactly what is being referred to. Much like pronouns, there are also several different types of determiners.

- The, a, an — articles

- This, that, those — you might recognise these for demonstrative pronouns are also determiners

- One, two, three etc. — cardinal numbers

- First, second, third etc. — ordinal numbers

- Some, most, all — quantifiers

- Other, another — difference words

‘The first restaurant is better than the other.’

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that connect other words, phrases, and clauses together within a sentence. There are three main types of conjunctions;

-

Coordinating conjunctions — these link independent clauses together.

-

Subordinating conjunctions — these link dependent clauses to independent clauses.

- Correlative conjunctions — words that work in pairs to join two parts of a sentence of equal importance.

For, and, nor, but, or, yet, so — coordinating conjunctions

After, as, because, when, while, before, if, even though — subordinating conjunctions

Either/or, neither/nor, both/and — correlative conjunctions

‘If it rains, I’m not going out.’

Interjections

Interjections are exclamatory words used to express an emotion or a reaction. They often stand alone from the rest of the sentence and are accompanied by an exclamation mark.

Oh

Oops!

Phew!

Ahh!

‘Oh, what a surprise!’

Word class: lexical classes and function classes

A helpful way to understand lexical word classes is to see them as the building blocks of sentences. If the lexical word classes are the blocks themselves, then the function word classes are the cement holding the words together and giving structure to the sentence.

In this diagram, the lexical classes are in blue and the function classes are in yellow. We can see that the words in blue provide the key information, and the words in yellow bring this information together in a structured way.

Word class examples

Sometimes it can be tricky to know exactly which word class a word belongs to. Some words can function as more than one word class depending on how they are used in a sentence. For this reason, we must look at words in context, i.e. how a word works within the sentence. Take a look at the following examples of word classes to see the importance of word class categorisation.

The dog will bark if you open the door.

The tree bark was dark and rugged.

Here we can see that the same word (bark) has a different meaning and different word class in each sentence. In the first example, ‘bark’ is used as a verb, and in the second as a noun (an object in this case).

I left my sunglasses on the beach.

The horse stood on Sarah’s left foot.

In the first sentence, the word ‘left’ is used as a verb (an action), and in the second, it is used to modify the noun (foot). In this case, it is an adjective.

I run every day

I went for a run

In this example, ‘run’ can be a verb or a noun.

Word Class — Key takeaways

-

We group words into word classes based on the function they perform in a sentence.

-

The four main word classes are nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs. These are lexical classes that give meaning to a sentence.

-

The other five word classes are prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, and interjections. These are function classes that are used to explain grammatical and structural relationships between words.

-

It is important to look at the context of a sentence in order to work out which word class a word belongs to.

Frequently Asked Questions about Word Class

A word class is a group of words that have similar properties and play a similar role in a sentence.

Some examples of how some words can function as more than one word class include the way ‘run’ can be a verb (‘I run every day’) or a noun (‘I went for a run’). Similarly, ‘well’ can be an adverb (‘He plays the guitar well’) or an adjective (‘She’s feeling well today’).

The nine word classes are; Nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, prepositions, pronouns, determiners, conjunctions, interjections.

Categorising words into word classes helps us to understand the function the word is playing within a sentence.

Parts of speech is another term for word classes.

The different groups of word classes include lexical classes that act as the building blocks of a sentence e.g. nouns. The other word classes are function classes that act as the ‘glue’ and give grammatical information in a sentence e.g. prepositions.

The word classes for all, that, and the is:

‘All’ = determiner (quantifier)

‘That’ = pronoun and/or determiner (demonstrative pronoun)

‘The’ = determiner (article)

Final Word Class Quiz

Word Class Quiz — Teste dein Wissen

Question

A word can only belong to one type of noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

This is false. A word can belong to multiple categories of nouns and this may change according to the context of the word.

Show question

Question

Name the two principal categories of nouns.

Show answer

Answer

The two principal types of nouns are ‘common nouns’ and ‘proper nouns’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following is an example of a proper noun?

Show answer

Question

Name the 6 types of common nouns discussed in the text.

Show answer

Answer

Concrete nouns, abstract nouns, countable nouns, uncountable nouns, collective nouns, and compound nouns.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a concrete noun and an abstract noun?

Show answer

Answer

A concrete noun is a thing that physically exists. We can usually touch this thing and measure its proportions. An abstract noun, however, does not physically exist. It is a concept, idea, or feeling that only exists within the mind.

Show question

Question

Pick out the concrete noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

Pick out the abstract noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

What is the difference between a countable and an uncountable noun? Can you think of an example for each?

Show answer

Answer

A countable noun is a thing that can be ‘counted’, i.e. it can exist in the plural. Some examples include ‘bottle’, ‘dog’ and ‘boy’. These are often concrete nouns.

An uncountable noun is something that can not be counted, so you often cannot place a number in front of it. Examples include ‘love’, ‘joy’, and ‘milk’.

Show question

Question

Pick out the collective noun from the following:

Show answer

Question

What is the collective noun for a group of sheep?

Show answer

Answer

The collective noun is a ‘flock’, as in ‘flock of sheep’.

Show question

Question

The word ‘greenhouse’ is a compound noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

This is true. The word ‘greenhouse’ is a compound noun as it is made up of two separate words ‘green’ and ‘house’. These come together to form a new word.

Show question

Question

What are the adjectives in this sentence?: ‘The little boy climbed up the big, green tree’

Show answer

Answer

The adjectives are ‘little’ and ‘big’, and ‘green’ as they describe features about the nouns.

Show question

Question

Place the adjectives in this sentence into the correct order: the wooden blue big ship sailed across the Indian vast scary ocean.

Show answer

Answer

The big, blue, wooden ship sailed across the vast, scary, Indian ocean.

Show question

Question

What are the 3 different positions in which an adjective can be placed?

Show answer

Answer

An adjective can be placed before a noun (pre-modification), after a noun (post-modification), or following a verb as a complement.

Show question

Question

In this sentence, does the adjective pre-modify or post-modify the noun? ‘The unicorn is angry’.

Show answer

Answer

The adjective ‘angry’ post-modifies the noun ‘unicorn’.

Show question

Question

In this sentence, does the adjective pre-modify or post-modify the noun? ‘It is a scary unicorn’.

Show answer

Answer

The adjective ‘scary’ pre-modifies the noun ‘unicorn’.

Show question

Question

What kind of adjectives are ‘purple’ and ‘shiny’?

Show answer

Answer

‘Purple’ and ‘Shiny’ are qualitative adjectives as they describe a quality or feature of a noun

Show question

Question

What kind of adjectives are ‘ugly’ and ‘easy’?

Show answer

Answer

The words ‘ugly’ and ‘easy’ are evaluative adjectives as they give a subjective opinion on the noun.

Show question

Question

Which of the following adjectives is an absolute adjective?

Show answer

Question

Which of these adjectives is a classifying adjective?

Show answer

Question

Convert the noun ‘quick’ to its comparative form.

Show answer

Answer

The comparative form of ‘quick’ is ‘quicker’.

Show question

Question

Convert the noun ‘slow’ to its superlative form.

Show answer

Answer

The comparative form of ‘slow’ is ‘slowest’.

Show question

Question

What is an adjective phrase?

Show answer

Answer

An adjective phrase is a group of words that is ‘built’ around the adjective (it takes centre stage in the sentence). For example, in the phrase ‘the dog is big’ the word ‘big’ is the most important information.

Show question

Question

Give 2 examples of suffixes that are typical of adjectives.

Show answer

Answer

Suffixes typical of adjectives include -able, -ible, -ful, -y, -less, -ous, -some, -ive, -ish, -al.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a main verb and an auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

A main verb is a verb that can stand on its own and carries most of the meaning in a verb phrase. For example, ‘run’, ‘find’. Auxiliary verbs cannot stand alone, instead, they work alongside a main verb and ‘help’ the verb to express more grammatical information e.g. tense, mood, possibility.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a primary auxiliary verb and a modal auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

Primary auxiliary verbs consist of the various forms of ‘to have’, ‘to be’, and ‘to do’ e.g. ‘had’, ‘was’, ‘done’. They help to express a verb’s tense, voice, or mood. Modal auxiliary verbs show possibility, ability, permission, or obligation. There are 9 auxiliary verbs including ‘could’, ‘will’, might’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are primary auxiliary verbs?

-

Is

-

Play

-

Have

-

Run

-

Does

-

Could

Show answer

Answer

The primary auxiliary verbs in this list are ‘is’, ‘have’, and ‘does’. They are all forms of the main primary auxiliary verbs ‘to have’, ‘to be’, and ‘to do’. ‘Play’ and ‘run’ are main verbs and ‘could’ is a modal auxiliary verb.

Show question

Question

Name 6 out of the 9 modal auxiliary verbs.

Show answer

Answer

Answers include: Could, would, should, may, might, can, will, must, shall

Show question

Question

‘The fairies were asleep’. In this sentence, is the verb ‘were’ a linking verb or an auxiliary verb?

Show answer

Answer

The word ‘were’ is used as a linking verb as it stands alone in the sentence. It is used to link the subject (fairies) and the adjective (asleep).

Show question

Question

What is the difference between dynamic verbs and stative verbs?

Show answer

Answer

A dynamic verb describes an action or process done by a noun or subject. They are thought of as ‘action verbs’ e.g. ‘kick’, ‘run’, ‘eat’. Stative verbs describe the state of being of a person or thing. These are states that are not necessarily physical action e.g. ‘know’, ‘love’, ‘suppose’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are dynamic verbs and which are stative verbs?

-

Drink

-

Prefer

-

Talk

-

Seem

-

Understand

-

Write

Show answer

Answer

The dynamic verbs are ‘drink’, ‘talk’, and ‘write’ as they all describe an action. The stative verbs are ‘prefer’, ‘seem’, and ‘understand’ as they all describe a state of being.

Show question

Question

What is an imperative verb?

Show answer

Answer

Imperative verbs are verbs used to give orders, give instructions, make a request or give warning. They tell someone to do something. For example, ‘clean your room!’.

Show question

Question

Inflections give information about tense, person, number, mood, or voice. True or false?

Show answer

Question

What information does the inflection ‘-ing’ give for a verb?

Show answer

Answer

The inflection ‘-ing’ is often used to show that an action or state is continuous and ongoing.

Show question

Question

How do you know if a verb is irregular?

Show answer

Answer

An irregular verb does not take the regular inflections, instead the whole word is spelt a different way. For example, begin becomes ‘began’ or ‘begun’. We can’t add the regular past tense inflection -ed as this would become ‘beginned’ which doesn’t make sense.

Show question

Question

Suffixes can never signal what word class a word belongs to. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

False. Suffixes can signal what word class a word belongs to. For example, ‘-ify’ is a common suffix for verbs (‘identity’, ‘simplify’)

Show question

Question

A verb phrase is built around a noun. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

False. A verb phrase is a group of words that has a main verb along with any other auxiliary verbs that ‘help’ the main verb. For example, ‘could eat’ is a verb phrase as it contains a main verb (‘could’) and an auxiliary verb (‘could’).

Show question

Question

Which of the following are multi-word verbs?

-

Shake

-

Rely on

-

Dancing

-

Look up to

Show answer

Answer

The verbs ‘rely on’ and ‘look up to’ are multi-word verbs as they consist of a verb that has one or more prepositions or particles linked to it.

Show question

Question

What is the difference between a transition verb and an intransitive verb?

Show answer

Answer

Transitive verbs are verbs that require an object in order to make sense. For example, the word ‘bring’ requires an object that is brought (‘I bring news’). Intransitive verbs do not require an object to complete the meaning of the sentence e.g. ‘exist’ (‘I exist’).

Show question

Answer

An adverb is a word that gives more information about a verb, adjective, another adverb, or a full clause.

Show question

Question

What are the 3 ways we can use adverbs?

Show answer

Answer

We can use adverbs to modify a word (modifying adverbs), to intensify a word (intensifying adverbs), or to connect two clauses (connecting adverbs).

Show question

Question

What are modifying adverbs?

Show answer

Answer

Modifying adverbs are words that modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. They add further information about the word.

Show question

Question

‘Additionally’, ‘likewise’, and ‘consequently’ are examples of connecting adverbs. True or false?

Show answer

Answer

True! Connecting adverbs are words used to connect two independent clauses.

Show question

Question

What are intensifying adverbs?

Show answer

Answer

Intensifying adverbs are words used to strengthen the meaning of an adjective, another adverb, or a verb. In other words, they ‘intensify’ another word.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are intensifying adverbs?

-

Calmly

-

Incredibly

-

Enough

-

Greatly

Show answer

Answer

The intensifying adverbs are ‘incredibly’ and ‘greatly’. These strengthen the meaning of a word.

Show question

Question

Name the main types of adverbs

Show answer

Answer

The main adverbs are; adverbs of place, adverbs of time, adverbs of manner, adverbs of frequency, adverbs of degree, adverbs of probability, and adverbs of purpose.

Show question

Question

What are adverbs of time?

Show answer

Answer

Adverbs of time are the ‘when?’ adverbs. They answer the question ‘when is the action done?’ e.g. ‘I’ll do it tomorrow’

Show question

Question

Which of the following are adverbs of frequency?

-

Usually

-

Patiently

-

Occasionally

-

Nowhere

Show answer

Answer

The adverbs of frequency are ‘usually’ and ‘occasionally’. They are the ‘how often?’ adverbs. They answer the question ‘how often is the action done?’.

Show question

Question

What are adverbs of place?

Show answer

Answer

Adverbs of place are the ‘where?’ adverbs. They answer the question ‘where is the action done?’. For example, ‘outside’ or ‘elsewhere’.

Show question

Question

Which of the following are adverbs of manner?

-

Never

-

Carelessly

-

Kindly

-

Inside

Show answer

Answer

The words ‘carelessly’ and ‘kindly’ are adverbs of manner. They are the ‘how?’ adverbs that answer the question ‘how is the action done?’.

Show question

Discover the right content for your subjects

No need to cheat if you have everything you need to succeed! Packed into one app!

Study Plan

Be perfectly prepared on time with an individual plan.

Quizzes

Test your knowledge with gamified quizzes.

Flashcards

Create and find flashcards in record time.

Notes

Create beautiful notes faster than ever before.

Study Sets

Have all your study materials in one place.

Documents

Upload unlimited documents and save them online.

Study Analytics

Identify your study strength and weaknesses.

Weekly Goals

Set individual study goals and earn points reaching them.

Smart Reminders

Stop procrastinating with our study reminders.

Rewards

Earn points, unlock badges and level up while studying.

Magic Marker

Create flashcards in notes completely automatically.

Smart Formatting

Create the most beautiful study materials using our templates.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We’ll assume you’re ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish. Accept

Privacy & Cookies Policy

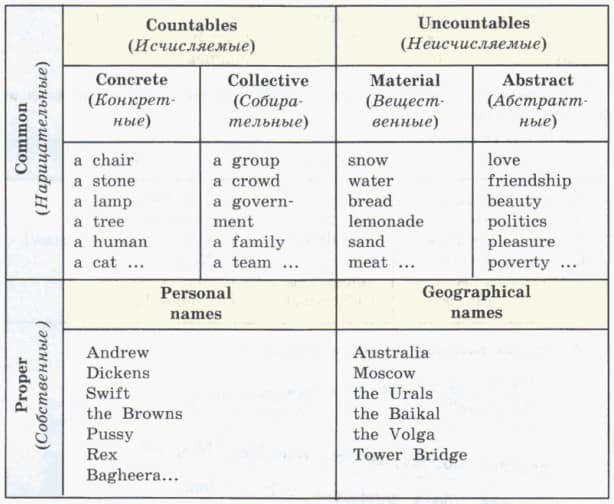

Nouns fall under two classes: (A) proper

nouns; (B) common

nouns.1

1 The name

proper is

from Lat. proprius ‘one’s

own’. Hence a proper name means

one’s own individual name, as distinct from a common

name, that can be given to a class of

individuals. The name common is

from Lat. communis and

means that which is shared by several things or individuals

possessing some common characteristic.

A. Proper nouns are

individual names given to separate persons or things. As regards

their meaning proper nouns may be personal names (Mary,

Peter, Shakespeare), geographical names

(Moscow, London, the Caucasus), the

names of the months and of the days of the week (February,

Monday), names of ships, hotels, clubs

etc.

A large number of nouns now proper were originally

common nouns (Brown, Smith, Mason).

Proper nouns may change their meaning and become

common nouns:

George went over to the table and took a

sandwich and a glass of

champagne.

(Aldington)

В. Common nouns are

names that can be applied to any individual of a class of persons or

things (e. g. man, dog, book),

collections of similar individuals or

things regarded as a single

unit (e. g. peasantry, family),

materials (e. g. snow,

iron, cotton) or abstract notions (e.

g. kindness, development).

Thus there are different groups of common nouns:

class nouns,

collective nouns,

nouns of material and

abstract nouns.

Nouns may also be classified from another point of

view: nouns denoting things (the word thing

is used in a broad sense) that can be

counted are called countable

nouns; nouns denoting things that cannot be counted are called

uncountable nouns.

1. Class nouns denote

persons or things belonging to a class. They are countables and have

two numbers: sinuglar and plural. They are generally used with an

article.1

1 On the use

of articles with class nouns see Chapter II, § 2, 3.

“Well, sir,” said Mrs. Parker, “I wasn’t

in the shop above

a great deal.”

(Mansfield)

He goes to the part of the town where the shops

are. (Lessing)

2. Collective nouns

denote a number or collection of

similar individuals or things regarded as a single unit.

Collective nouns fall under the following groups:

(a) nouns used only in the singular and denoting a

number of things collected together and regarded as a single object:

foliage, machinery.

It was

not restful, that green foliage.

(London)

Machinery new to

the industry in Australia was

introduced for preparing

land. (Agricultural

Gazette)

(b) nouns which are singular in form though plural

in meaning: police, poultry, cattle,

people, gentry. They are usually called

nouns of multitude. When the subject of the sentence is a noun of

multitude the verb used as predicate is in the plural:

I had no idea the police

were so

devilishly prudent. (Shaw)

Unless cattle are

in good condition in calving, milk

production will never

reach a high level. (Agricultural

Gazette)

The weather was warm and the people

were sitting

at their doors. (Dickens)

(c) nouns that may be both singular and plural:

family, crowd, fleet, nation. We

can think of a number of crowds, fleets or different nations as well

as of a single crowd, fleet, etc.

A small crowd is

lined up to see the guests arrive. (Shaw)

Accordingly they were soon afoot, and walking in

the direction of the scene of

action, towards which crowds

of people were already pouring from a

variety

of quarters. (Dickens)

3. Nouns of material

denote material: iron,

gold, paper, tea, water. They are

uncountables and are generally used without any article.1

1 On the use

of articles with nouns of material see Chapter II, § 5, 6, 7.

There was a scent of honey

from the lime-trees in flower.

(Galsworthy)

There was coffee

still in the urn. (Wells)

Nouns of material are used in the plural to denote

different sorts of a given material.

…that his senior counted upon him in this

enterprise, and had consigned a quantity of select wines

to him… (Thackeray)

Nouns of material may turn into class nouns (thus

becoming countables) when they come to express an individual object

of definite shape.

C o m p a r e:

To the left were clean panes of glass.

(Ch. Bronte)

“He came in here,” said the waiter looking at

the light through the tumbler,

“ordered a glass of

this ale.” (Dickens)

But the person in the glass

made a face at her, and Miss Moss went

out.

(Mansfield)

4. Abstract nouns

denote some quality, state, action or

idea: kindness, sadness, fight. They

are usually uncountables, though some of them may be countables (e.

g. idea, hour).2

2 On the use

of articles with abstract nouns see Chapter II, § 8, 9, 10, 11.

Therefore when the youngsters saw that mother

looked neither frightened nor

offended, they gathered new courage.

(Dodge)

Accustomed to John Reed’s abuse — I never had

an idea of

replying to it.

(Ch. Bronte)

It’s these people with fixed ideas.

(Galsworthy)

Abstract nouns may change their meaning and become

class nouns. This change is marked by the use of the article and of

the plural number:

|

beauty |

a beauty |

beauties |

|

sight |

a sight |

sights |

He was responsive to beauty

and here was cause to respond. (London)

She was a beauty.

(Dickens)

…but she isn’t one of those horrid regular

beauties.

(Aldington)

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

The head of a noun phrase either takes the form of a noun or a pronoun. The head determines such features of the noun phrase as number (singular or plural) and gender (masculine, feminine or neuter). In terms of meaning, the head determines what kind or type of entity the whole noun phrase refers to.

Thus, the following noun phrases have the same noun, car, as head and therefore refer to the same kind of entity, namely some kind of car. The exact reference of the full noun phrases differ because of the different determiners and modifiers that accompany the head.

(1) the blue car that Lisa bought

(2) the yellow car that is parked outside my office

(3) a French car with four-wheel steering

Nouns can be grouped into different classes based on their grammatical properties.

A first major distinction among nouns is that between proper nouns and common nouns. Simply put, proper nouns are nouns that functions as names of people, cities, countries, etc. Typical examples are: Bill, Stockholm, and Denmark. All other nouns are common nouns, e.g. car, water, and democracy.

The distinction is relevant to capitalisation. Thus, proper nouns always start with a capital letter.

- More on capitalisation

Since proper nouns are used to refer to unique individuals, places, and so on, they do not show a distinction between definite and indefinite forms, which for common nouns is signalled by the definite and indefinite articles. Most proper nouns occur without an article, like Sweden, Lund, Bill, etc. However, there are also classes of poper nouns which have a definite article as part of their name. Examples include names of daily newspapers (The Times, the Observer, etc.), names of theatres, museums, hotels, restaurants, and similar establishments (the Metropolitan, the British Museum, the Hilton, the Ritz, etc. If the name of such an establishment consists of a noun or noun phase in the genitive, then even these proper nouns occur without an article (McDonald’s, Sloppy Joe’s).

Proper nouns in the plural form another important class that occur with the definite article. Typical examples include names of mountain ranges (the Himalayas), groups of islands (The Canaries), and others (the Midlands, the Neherlands, the Balkans).

Common nouns may be divided into countable and uncountable nouns. As the terminology suggests, countable nouns can combine with numerals like one, two, three, etc., whereas uncountable nouns cannot. Moreover, uncountable nouns are always singular, whereas most countable nouns may be either singular or plural. A number of properties related to this basic difference distinguish the two classes of nouns. The following table lists the most important ones, and provides examples of both types of noun. (The asterisk * marks an example as ungrammatical.)

| countable nouns | uncountable nouns |

|

accept the indefinite article: |

do not accept the indefinite article: |

|

typically have a plural form: |

have no plural form: money — *moneys, evidence — *evidences, nonsense — *nonsenses |

|

can, and sometimes must, be replaced by the pronoun one: |

cannot be replaced by the pronoun one: |

| in the plural, combine with plural quantifiers like many, a great number of, etc.: many cars, a great number of houses |

only combine with singular quantifiers like much, a great deal of, etc.: much evidence, a great deal of money |

There are certain quantifiers that are used in connection with uncountable nouns and others that are used in connection with countable nouns. In (1), quantifiers that can only be used with countable nouns have erroneously been used in connection with uncountable nouns. The resulting constructions are ungrammatical:

(1) *many pork; *quite a few pork; or *a large number of pork.

What we have to say is instead is, for instance

(2) much pork; a large amount of pork; or lots of pork.

Note in relation to this that the relatively informal quantifying expressions a lot of, lots of, and loads of can be used to quantify both countable and uncountable nouns. However, they cannot be used in formal academic writing.

In addition to the ways of quantifying uncountables just mentioned, we can also make use use what is called ‘partitive constructions’. Examples of partitive constructions include the following:

(3) a bottle of water; a clap of thunder; a grain of wheat; a slice of ham; a state of mind; a piece of bread; a box of chocolate; an act of violence

A partitive construction is thus a construction where we make use of a countable noun that can be used to denote a certain portion of something uncountable. By doing this, we can can now count the portions, even though their content as such is uncountable. For example, we can use the following noun phrases:

(4) seven bottles of water; six slices of ham; two boxes of chocolate

As we may conclude from the examples in (iii) and (iv) above, some partitive expressions denote portions or quantities that are fairly well defined, while others are rather inexact. For instance, it is not at all obvious how much violence is included in an act of violence.

For language users in general, it is important to learn the idiomatic partitive expressions that go together with the various uncountable nouns that you somehow want to quantify. Your language will easily be too dull, informal, and inexact if you constantly make use of general expressions such as a piece of X or a bunch of X. Moreover, only using quantifying expressions, such as some X or a great deal of X, is not an option either, since they are too inexact for most purposes.

A good dictionary will help you find the right partitive expressions, but you can also get some help from the following list:

a word of advice a round of applausea work of art

a pile of ashes

a bar of chocolatea box of chocolatea cup of chocolatea packet of cigarettesa web of deceita speck of dusta work of fictiona suit of furniturea blade of grassa body of knowledgea roar of laughtera beam of lighta flash of lightninga stroke of good lucka fit of madness a piece of musica piece/item of news a piece of piean area of researcha body of researcha bag of ricea field of studya lump of sugara cloud of suspiciona web of trusta shot of whiskya gust of wind a log of wooda splinter of wooda piece of work

It is important to understand that even though a certain noun is basically countable, it may also have a fairly frequent uncountable use (and vice versa). Take the word beer, for instance. It is basically uncountable, as are all liquids and substances. In spite of beer being basically uncountable, we can naturally say things such as (1) and (2):

(1) She had three beers yesterday.

(2) This is actually a beer that I don’t like.

These examples show that one and the same noun can have both a countable and an uncountable use. In fact, this is not at all uncommon.

It is also important to understand that this distinction between countable and uncountable nouns is not ad hoc. Instead, it is based on what the world is like, or at least on how language users view the world and the various types of entities in it that can be denoted by nouns.

What is meant by this is that whether a noun is categorised as countable or uncountable in a certain language depends on whether or not the speakers of that language think that the entity that the noun is typically used to refer to is possible to count or not. If something is possible to count, it can relatively easily be defined and observed where one of this entity begins and ends and where another one begins and ends, as it were.

Given this brief and simplified account of the ontological and cognitive basis of the uncountable/countable distinction, we should be able to form the hypothesis that fairly closely related languages like English and Swedish, which are primarily spoken by people from relatively similar cultures, should not differ very much when it comes to which nouns are countable and which are uncountable.This hypothesis is correct. For the large majority of nouns, there is no difference in countability between the English noun and its Swedish counterpart. This is good news, of course.

However, there are also a number of important exceptions that we need to be aware of (in addition to remembering that one and the same noun may be used in more than one way), partly in order to get the agreement between subject and verb right. Estling Vanneståhl (2007:99) provides the following list of nouns which are uncountable in English, but countable or plural in Swedish (please note that the list is not intended to be exhaustive):

| UNCOUNTABLE IN ENGLISH |

COUNTABLE OR PLURAL IN SWEDISH |

| abuse | skällsord |

| advice | råd |

| applause | applåd/er/ |

| behaviour | beteende/n/ |

| cash | kontanter |

| change | växel/pengar/ |

| equipment | utrustning/ar/ |

| evidence | bevis |

| furniture | möbel, möbler |

| garbage | sopor |

| gear (informal) | grejer, prylar |

| hardware | järnvaror |

| homework | läxa, läxor |

| information | upplysning/ar/ |

| interest | ränta, räntor |

| jewellery | smycke, smycken |

| knowledge | kunskap/er/ |

| lightning | blixt/ar/ |

| money | peng/ar/ |

| news | nyhet/er/ |

| nonsense | dumheter |

| pollution | förorening/ar/ |

| progress | framsteg |

| proof | bevis |

| revenue | statsinkomster |

| rubbish | sopor |

| stationery | pappersvaror |

| stuff (informal) | grejer, prylar |

| underwear | underkläder |

Notice that quite a few of the words on this list are words that are quite frequent, both in academic and everyday uses of English.

Some nouns are such that they cannot be used in the singular, that is, they are always regarded as denoting something plural, and they always take plural agreement. Important members of this category appear in the following examples:

(4) My new jeans are Italian.

(5) We have to buy Peter new pyjamas, since his old ones are worn out.

(6) In this experiment, headphones are to be used.

(7) The ship’s doctor made use of tweezers to remove the foreign object.

(8) The minutes were kept by Sheila.

(9) The goods have been exported to Germany.

(10) All our valuables have been stolen.

(11) The police are investigating the case.

(12) There were hundreds of police present in Stockholm in connection with the royal wedding.

(13) Do you know how many people are here?

(14) The cattle were seen grazing in the field.

(15) We do not want vermin in our house, but they are here anyway.

This may not seem so problematic at first sight. Sometimes we use the corresponding nouns in much the same way in Swedish. This is the case with jeans, for instance which requires a plural adjective in Swedish:

(1) Mina nya jeans var inte dyra.

This is often explained by the fact that jeans, trousers (‘byxor’), tights, etc. somehow consist of two parts. The Swedish noun pyjamas, however, is different from its English counterpart, in spite of the fact that pyjamas traditionally consist of two parts. In Swedish we get (2), while the corresponding English sentence would be (3):

(2) Jag måste köpa honom en ny pyjamas.

(3) I must buy him new pyjamas.

In other words, we cannot use *a new pyjamas, since pyjamas is always plural in English.

Headphones corresponds to Swedish hörlurar, which is also normally plural, even though (4) is fully grammatical:

(4) Min ena hörlur är trasig.

The Swedish word corresponding to the English tweezers is pincett. This noun is not plural in Swedish, even though it can be said to consist of two parts. It seems as if this rule or tendency (i.e. that nouns that denote objects that consist of two parts are treated as plural) is stronger in English than in Swedish. This means, for instance, that (5) does not correspond to (6) or (7), but to (8):

(5) Jag behöver en pincett nu.

(6) *I need a tweezers now.

(7) *I need a tweezer now.

(8) I need (some) tweezers now.

Even though minutes is plural in English, the corresponding Swedish word protokoll is a regular noun that can be either singular or plural:

(9) Protokollet var välskrivet.

(10) Protokollen hade inte blivit justerade.

Goods corresponds to Swedish varor. However, in Swedish it is perfectly normal to use the singular vara (11), while good is not normally used in the singular in English (12):

(11) Jag letar efter en viss vara.

(12) *I’m looking for a certain good.

However, in the field of economics, the singular good is actually used, as in the authentic (13):

(13) Money is a good that acts as a medium of exchange in transactions. Classically it is said that money acts as a unit of account, a store of value, and a medium of exchange. Most authors find that the first two are nonessential properties that follow from the third. In fact, other goods are often better than money at being intertemporal stores of value, since most monies degrade in value over time through inflation or the overthrow of governments (https://www.thoughtco.com/definition-of-money-in-economics-p2-1146354, emphasis by AWELU).

Just like valuables is plural in English, värdesaker is plural in Swedish. The singular värdesak is normally not used in Swedish, even though it occurs. So does in fact the singular valuable in English, but this, too, is rather infrequent.

Finally in this subsection we have some nouns that do not end in a plural -s, but which are problematic because they are always plural, often in a collective or generic sense. For instance, when we use the police, we normally refer to the whole police force, and when we talk about people, we often talk about people in general.

It is important, however, that we understand that there is a clear difference between being uncountable and being inherently plural with a (typically) collective/generic meaning. Grammatically, the most important difference is that while uncountable nouns always take singular subject-verb agreement, plural nouns always take plural agreement.

Even though these nouns are inherently plural and collective in English, this need not be the case in other languages, such as Swedish. For instance while (14) is fully grammatical in Swedish, (15) is not possible to use in English. Instead we have to use (16):

(14) Polisen var ung och stilig.

(15) *The police was young and handsome.

(16) The policeman was young and handsome.

Nouns that end in —ics look plural, but are actually most often treated as singular. Thus, when heading a noun phrase which functions as the subject, they trigger singular agreement on the verb.

(16) Statistics is becoming increasingly popular among our students.

(17) Mathematics is an integral part of our culture.

(18) Western economics has tended not to be influenced by theories from other parts of the world.

In the examples above, the nouns in —ics denote academic disciplines. However, some of these nouns may also be used to denote the practical application of the discipline, and are then treated as ordinary plurals, e.g. by taking plural determiners and by triggering plural agreement on the verb.

(19) These statistics show that our production of beef has almost doubled.

(20) The acoustics of the new concert hall are very lively.

Zero plural nouns are nouns that look the same in the plural as they do in the singular. A well-known example is the noun sheep. Since sheep is a zero plural noun, it looks the same in the two sentences below. However, this does not prevent it from being singular in the first sentence and plural in the second one, as indicated by the different verb forms, is and are:

(21) My sheep is black.

(22) My sheep are black.

Other nouns that belong to this category are aircraft, Chinese, deer, elk, headquarters, horsepower, hovercraft, means, offspring, Portuguese, salmon, series, species, trout, and Vietnamese. When in doubt, please consult a good dictionary.

There is a group of nouns whose members are commonly referred to as ‘foreign plurals’. What the nouns in this group have in common is that both their singular and their plural forms have been borrowed from other languages, which means that the plural ending is not the regular English —s, but something else.

Examples of such foreign plural nouns that are important to remember, especially when writing academic texts (since many of these words tend to be academic in nature), are analysis-analyses, basis-bases, criterion-criteria, diagnosis-diagnoses, hypothesis-hypotheses, parenthesis-parentheses, phenomenon-phenomena, stimulus-stimuli, and thesis-theses.

What usually happens when a word is borrowed into English (or into some other language) is that it is changed in line with the morphology of the language into which it has been borrowed. Consequently, there are some foreign words in English that have both a foreign and an English plural form. Examples include appendix-appendixes/appendices, cactus-cactuses/cacti, focus-focuses/foci, and index-indexes/indices.

A couple of etymologically plural nouns are sometimes used as (uncountable) singulars. The two most common examples are media and data. The singular uses are not universally accepted, however, so non-native writers are well-advised to use them as plurals in examples like the following:

(23) These data show that our initial assumption was right.

(24) The media have become more interested in environmental issues.

Как вы уже, очевидно знаете, английские имена существительные подразделяются на собственные и нарицательные. Нарицательные, в свою очередь, бывают исчисляемыми и неисчисляемыми.

С исчисляемыми и неисчисляемыми существительными вы можете подробнее ознакомится в нашем видеоуроке:

Видеоурок английского языка: исчисляемые и неисчисляемые имена существительные

А теперь рассмотрим более подробную классификацию:

Concrete Nouns – Конкретные имена существительные

Конкретные имена существительные обозначают предметы или людей и имеют форму единственного и множественного числа. Такие существительные в единственном числе обязательно должны сопровождаться определителем: артиклем (a/the), притяжательным или указательным местоимением (my, his, this etc.), либо числительным one.

- Do you need an umbrella? – Тебе нужен зонт?

- My room is quite large. – Моя комната довольно большая.

- This sweater is made of wool. – Этот свитер сделан из шерсти

- I can see one car on the parking-lot. – Я вижу одну машину на парковке.

Конкретные и. сущ.могут также употребляться во множественном числе с артиклем или без, в зависимости от контекста.

- Those are nice chairs. – Это хорошие стулья.

- Most of my friends are students. – Большинство моих друзей – студенты.

- The children playing at the sportsground live nearby. – Дети, которые играют на спортплощадке, живут поблизости.

- Copy out the new words at page 25.- Спишите новые слова на странице 25.

Collective nouns — Собирательные имена существительные

К собирательным в английском языке относятся существительные, обозначающие группу людей, животных, предметов, явлений и т. д., которые воспринимаются говорящим как единое целое.

Основной вопрос касательно собирательных существительных – следует ли согласовывать с ними глагол единственного или множественного числа?

Некоторые собирательные существительные согласуются с глаголом только в единственном числе – machinery (механизмы, оборудование), species (биологический вид), means (средство, способ). Другие существительные согласуются с глаголом только во множественном числе: people (люди), police (полиция), cattle (скот), poultry (птица).

Отдельной группой идут собирательные существительные, допускающие согласование с глаголом как в единственном, так и во множественном числе. Это слова, относящиеся к объединениям и организациям, группам людей: team (команда), crowd (толпа), public (публика), audience (зрители, аудитория), class (класс), staff (персонал), company (компания), committee (комитет) и др. Как же определить, в какое числе следует поставить глагол? Это зависит от того, действуют ли «собранные» члены, составляющие этот предмет, самостоятельно или образуют единое целое.

Следует использовать глагол в ед. числе, чтобы подчеркнуть, что организация рассматривается как единый объект, а глагол множественного числа – если рассматривается как коллектив отдельных людей.

- The committee usually raise their hands to vote ‘Yes’ – комитет обычно голосует «за» поднятием рук (глагол во мн. числе, т.к. поднимают руки члены комитета, а не комитет в целом)

- The class has its final test on Friday — В пятницу класс сдает последний зачет. (глагол в ед. числе, т.к. имеется в виду класс как структурная единица учебного коллектива, одно целое)

Часто возможно употребление формы как единственного, так и множественного числа практически без различия в значении, но в формальном контексте с собирательными существительными согласуется глагол в единственном числе.

- The volleyball team play / plays twice a week in the summer. – Волейбольная команда играет дважды в неделю в летний сезон.

- The orchestra perform / performs classical concerts throughout the year. – Оркестр дает концерты классической музыки весь год.

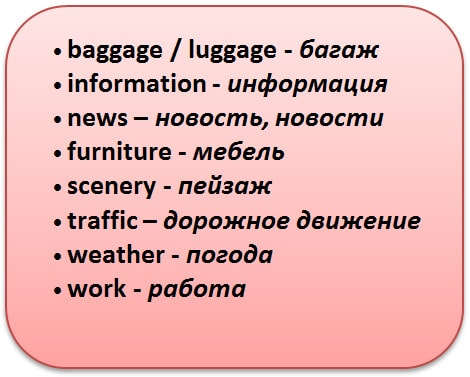

Material nouns – вещественные имена существительные

Вещественные имена существительные – это, прежде всего, продукты, вещества и материалы (meat, sugar, butter, water, glass, iron). К этой же группе можно отнести следующие слова:

Все эти существительные неисчисляемые и бывают только единственного числа.

- (At the café) Two coffees and an orange juice, please. – (В кафе) Два кофе и один сок, пожалуйста

- Luke ate three ice creams yesterday afternoon. – Вчера утром Люк съел 3 порции мороженого.

Abstract nouns — абстрактные имена существительные

В эту категорию относятся существительные, обозначающие нематериальные вещи и абстрактные понятия: advice (совет/советы), chaos (хаос), luck (удача), permission (разрешение), progress (прогресс), optimism (оптимизм), philosophy (философия) etc.

Все эти существительные также стоят всегда только в единственном числе.

Personal names – Собственные имена существительные

К собственным именам существительным относятся имена и фамилии людей, клички животных, названия газет и журналов, а также географические названия. Как правило, собственные имена существительные употребляются без артикля, за исключением определенных случаев:

- если речь идет о всей семье the Smiths, the Ivanovs

- с некоторыми географическими названиями (см. подробнее в нашем посте об употреблении артикля) – the Volga, the Philippines, The Black Sea

In linguistics, a noun class is a particular category of nouns. A noun may belong to a given class because of the characteristic features of its referent, such as gender, animacy, shape, but such designations are often clearly conventional. Some authors use the term «grammatical gender» as a synonym of «noun class», but others consider these different concepts. Noun classes should not be confused with noun classifiers.

Notion[edit]

There are three main ways by which natural languages categorize nouns into noun classes:

- according to similarities in their meaning (semantic criterion);

- by grouping them with other nouns that have similar form (morphology);

- through an arbitrary convention.

Usually, a combination of the three types of criteria is used, though one is more prevalent.

Noun classes form a system of grammatical agreement. A noun in a given class may require:

- agreement affixes on adjectives, pronouns, numerals, etc. in the same noun phrase,

- agreement affixes on the verb,

- a special form of pronoun to replace the noun,

- an affix on the noun,

- a class-specific word in the noun phrase.

Modern English expresses noun classes through the third person singular personal pronouns he (male person), she (female person), and it (object, abstraction, or animal), and their other inflected forms. Countable and uncountable nouns are distinguished by the choice of many/much. The choice between the relative pronoun who (persons) and which (non-persons) may also be considered a form of agreement with a semantic noun class. A few nouns also exhibit vestigial noun classes, such as stewardess, where the suffix -ess added to steward denotes a female person. This type of noun affixation is not very frequent in English, but quite common in languages which have the true grammatical gender, including most of the Indo-European family, to which English belongs.

In languages without inflectional noun classes, nouns may still be extensively categorized by independent particles called noun classifiers.

Common criteria for noun classes[edit]

Common criteria that define noun classes include:

- animate vs. inanimate (as in Ojibwe)

- rational vs. non-rational (as in Tamil)

- human vs. non-human

- human vs. animal (zoic) vs. inanimate (as in Polish in masculine virile[1])

- male vs. other

- male human vs. other

- masculine vs. feminine

- masculine vs. feminine vs. neuter

- common vs. neuter

- strong vs. weak

- augmentative vs. diminutive

- countable vs. uncountable

Language families[edit]

Algonquian languages[edit]

The Ojibwe language and other members of the Algonquian languages distinguish between animate and inanimate classes. Some sources argue that the distinction is between things which are powerful and things which are not. All living things, as well as sacred things and things connected to the Earth are considered powerful and belong to the animate class. Still, the assignment is somewhat arbitrary, as «raspberry» is animate, but «strawberry» is inanimate.

Athabaskan languages[edit]

In Navajo (Southern Athabaskan) nouns are classified according to their animacy, shape, and consistency. Morphologically, however, the distinctions are not expressed on the nouns themselves, but on the verbs of which the nouns are the subject or direct object. For example, in the sentence Shi’éé’ tsásk’eh bikáa’gi dah siłtsooz «My shirt is lying on the bed», the verb siłtsooz «lies» is used because the subject shi’éé’ «my shirt» is a flat, flexible object. In the sentence Siziiz tsásk’eh bikáa’gi dah silá «My belt is lying on the bed», the verb silá «lies» is used because the subject siziiz «my belt» is a slender, flexible object.

Koyukon (Northern Athabaskan) has a more intricate system of classification. Like Navajo, it has classificatory verb stems that classify nouns according to animacy, shape, and consistency. However, in addition to these verb stems, Koyukon verbs have what are called «gender prefixes» that further classify nouns. That is, Koyukon has two different systems that classify nouns: (a) a classificatory verb system and (b) a gender system. To illustrate, the verb stem -tonh is used for enclosed objects. When -tonh is combined with different gender prefixes, it can result in daaltonh which refers to objects enclosed in boxes or etltonh which refers to objects enclosed in bags.

Australian Aboriginal languages[edit]

The Dyirbal language is well known for its system of four noun classes, which tend to be divided along the following semantic lines:[2]

- animate objects, men

- women, water, fire, violence

- edible fruit and vegetables

- miscellaneous (includes things not classifiable in the first three)

The class usually labeled «feminine», for instance, includes the word for fire and nouns relating to fire, as well as all dangerous creatures and phenomena. (This inspired the title of the George Lakoff book Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things.)

The Ngangikurrunggurr language has noun classes reserved for canines and hunting weapons. The Anindilyakwa language has a noun class for things that reflect light. The Diyari language distinguishes only between female and other objects. Perhaps the most noun classes in any Australian language are found in Yanyuwa, which has 16 noun classes, including nouns associated with food, trees and abstractions, in addition to separate classes for men and masculine things, women and feminine things. In the men’s dialect, the classes for men and for masculine things have simplified to a single class, marked the same way as the women’s dialect marker reserved exclusively for men.[3]

Basque[edit]

Basque has two classes, animate and inanimate; however, the only difference is in the declension of locative cases (inessive, ablative, allative, terminal allative, and directional allative). For inanimate nouns, the locative case endings are attached directly if the noun is singular, and plural and indefinite number are marked by the suffixes -eta- and -(e)ta-, respectively, before the case ending (this is in contrast to the non-locative cases, which follow a different system of number marking where the indefinite form of the ending is the most basic). For example, the noun etxe «house» has the singular ablative form etxetik «from the house», the plural ablative form etxeetatik «from the houses», and the indefinite ablative form etxetatik (the indefinite form is mainly used with determiners that precede the noun: zenbat etxetatik «from how many houses»). For animate nouns, on the other hand, the locative case endings are attached (with some phonetic adjustments) to the suffix -gan-, which is itself attached to the singular, plural, or indefinite genitive case ending. Alternatively, -gan- may attach to the absolutive case form of the word if it ends in a vowel. For example, the noun ume «child» has the singular ablative form umearengandik or umeagandik «from the child», the plural ablative form umeengandik «from the children», and the indefinite ablative form umerengandik or umegandik (cf. the genitive forms umearen, umeen, and umeren and the absolutive forms umea, umeak, and ume). In the inessive case, the case suffix is replaced entirely by -gan for animate nouns (compare etxean «in/at the house» and umearengan/umeagan «in/at the child»).

Caucasian languages[edit]

Some members of the Northwest Caucasian family, and almost all of the Northeast Caucasian languages, manifest noun class. In the Northeast Caucasian family, only Lezgian, Udi, and Aghul do not have noun classes. Some languages have only two classes, whereas Bats has eight. The most widespread system, however, has four classes: male, female, animate beings and certain objects, and finally a class for the remaining nouns. The Andi language has a noun class reserved for insects.

Among Northwest Caucasian languages, only Abkhaz and Abaza have noun class, making use of a human male/human female/non-human distinction.

In all Caucasian languages that manifest class, it is not marked on the noun itself but on the dependent verbs, adjectives, pronouns and postpositions or prepositions.

Atlantic–Congo languages[edit]

Atlantic–Congo languages can have ten or more noun classes, defined according to non-sexual criteria. Certain nominal classes are reserved for humans. The Fula language has about 26 noun classes (the exact number varies slightly by dialect). According to Steven Pinker, the Kivunjo language has 16 noun classes including classes for precise locations and for general locales, classes for clusters or pairs of objects and classes for the objects that come in pairs or clusters, and classes for abstract qualities.[4]

Bantu languages[edit]

According to Carl Meinhof, the Bantu languages have a total of 22 noun classes called nominal classes (this notion was introduced by W. H. J. Bleek). While no single language is known to express all of them, most of them have at least 10 noun classes. For example, by Meinhof’s numbering, Shona has 20 classes, Swahili has 15, Sotho has 18 and Ganda has 17.

Additionally, there are polyplural noun classes. A polyplural noun class is a plural class for more than one singular class.[5] For example, Proto-Bantu class 10 contains plurals of class 9 nouns and class 11 nouns, while class 6 contains plurals of class 5 nouns and class 15 nouns. Classes 6 and 10 are inherited as polyplural classes by most surviving Bantu languages, but many languages have developed new polyplural classes that are not widely shared by other languages.

Specialists in Bantu emphasize that there is a clear difference between genders (such as known from Afro-Asiatic and Indo-European) and nominal classes (such as known from Niger–Congo). Languages with nominal classes divide nouns formally on the base of hyperonymic meanings. The category of nominal class replaces not only the category of gender, but also the categories of number and case.

Critics of the Meinhof’s approach notice that his numbering system of nominal classes counts singular and plural numbers of the same noun as belonging to separate classes. This seems to them to be inconsistent with the way other languages are traditionally considered, where number is orthogonal to gender (according to the critics, a Meinhof-style analysis would give Ancient Greek 9 genders). If one follows broader linguistic tradition and counts singular and plural as belonging to the same class, then Swahili has 8 or 9 noun classes, Sotho has 11 and Ganda has 10.

The Meinhof numbering tends to be used in scientific works dealing with comparisons of different Bantu languages. For instance, in Swahili the word rafiki ‘friend’ belongs to the class 9 and its «plural form» is marafiki of the class 6, even if most nouns of the 9 class have the plural of the class 10. For this reason, noun classes are often referred to by combining their singular and plural forms, e.g., rafiki would be classified as «9/6», indicating that it takes class 9 in the singular, and class 6 in the plural.

However not all Bantu languages have these exceptions. In Ganda each singular class has a corresponding plural class (apart from one class which has no singular–plural distinction; also some plural classes correspond to more than one singular class) and there are no exceptions as there are in Swahili. For this reason Ganda linguists use the orthogonal numbering system when discussing Ganda grammar (other than in the context of Bantu comparative linguistics), giving the 10 traditional noun classes of that language.

The distinction between genders and nominal classes is blurred still further by Indo-European languages that have nouns that behave like Swahili’s rafiki. Italian, for example, has a group of nouns deriving from Latin neuter nouns that acts as masculine in the singular but feminine in the plural: il braccio/le braccia; l’uovo/le uova. (These nouns are still placed in a neuter gender of their own by some grammarians.)

Nominal classes in Swahili[edit]

| Class number | Prefix | Typical meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | m-, mw-, mu- | singular: persons |

| 2 | wa-, w- | plural: persons (a plural counterpart of class 1) |

| 3 | m-, mw-, mu- | singular: plants |

| 4 | mi-, my- | plural: plants (a plural counterpart of class 3) |

| 5 | ji-, j-, Ø- | singular: fruits |

| 6 | ma-, m- | plural: fruits (a plural counterpart of class 5, 9, 11, seldom 1) |

| 7 | ki-, ch- | singular: things |

| 8 | vi-, vy- | plural: things (a plural counterpart of class 7) |

| 9 | n-, ny-, m-, Ø- | singular: animals, things |

| 10 | n-, ny-, m-, Ø- | plural: animals, things (a plural counterpart of class 9 and 11) |

| 11, 14 | u-, w-, uw- | singular: no clear semantics |

| 15 | ku-, kw- | verbal nouns |

| 16 | pa- | locative meanings: close to something |

| 17 | ku- | indefinite locative or directive meaning |

| 18 | mu-, m- | locative meanings: inside something |

«Ø-» means no prefix. Some classes are homonymous (esp. 9 and 10). The Proto-Bantu class 12 disappeared in Swahili, class 13 merged with 7, and 14 with 11.

Class prefixes appear also on adjectives and verbs, e.g.:

The class markers which appear on the adjectives and verbs may differ from the noun prefixes:

‘My child bought a book.’

In this example, the verbal prefix a- and the pronominal prefix wa- are in concordance with the noun prefix m-: they all express class 1 despite of their different forms.

Zande[edit]

The Zande language distinguishes four noun classes:[6]

| Criterion | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| human (male) | kumba | man |

| human (female) | dia | wife |

| animate | nya | beast |

| other | bambu | house |

There are about 80 inanimate nouns which are in the animate class, including nouns denoting heavenly objects (moon, rainbow), metal objects (hammer, ring), edible plants (sweet potato, pea), and non-metallic objects (whistle, ball). Many of the exceptions have a round shape, and some can be explained by the role they play in Zande mythology.

Noun classes versus grammatical gender[edit]

The term gender, as used by some linguists, refers to a noun-class system composed with 2, 3, or 4 classes, particularly if the classification is semantically based on a distinction between masculine and feminine. Genders are then considered a sub-class of noun classes. Not all linguists recognize a distinction between noun-classes and genders, however, and instead use either the term «gender» or «noun class» for both.

Noun classes versus noun classifiers[edit]

Some languages, such as Japanese, Chinese and the Tai languages, have elaborate systems of particles that go with nouns based on shape and function, but are free morphemes rather than affixes. Because the classes defined by these classifying words are not generally distinguished in other contexts, there are many linguists who take the view that they do not create noun classes.

List of languages by type of noun classification[edit]

Languages with noun classes[edit]

- all Bantu languages such as

- Ganda: ten classes called simply Class I to Class X and containing all sorts of arbitrary groupings but often characterised as people, long objects, animals, miscellaneous objects, large objects and liquids, small objects, languages, pejoratives, infinitives, mass nouns, plus four ‘locative’ classes. Alternatively, the Meinhof system of counting singular and plural as separate classes gives a total of 21 classes including the four locatives.

- Swahili

- Zulu

- Northeast Caucasian languages such as Bats

- Dyirbal: Masculine, feminine, vegetable and other. (Some linguists do not regard the noun-class system of this language as grammatical gender.)

- Atlantic languages

- Fula (Fulfulde, Pulaar, Pular)

- Wolof

- Arapesh languages such as Mufian

Languages with grammatical genders[edit]

See also[edit]

- Animacy

- Classifier (linguistics)

- Declension

- Grammatical agreement

- Grammatical category

- Grammatical conjugation

- Grammatical gender

- Grammatical number

- Inflection

- Redundancy (linguistics)

- Synthetic language

References[edit]

Inline[edit]

- ^ «Slavic Languages».

- ^ Corbett 1991, p. 15.

- ^ Jean F Kirton. ‘Yanyuwa, a dying language’. In Michael J Ray (ed.), Aboriginal language use in the Northern Territory: 5 reports. Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics. Darwin: Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1988, p. 1–18.

- ^ Pinker, Steven (1994) The Language Instinct, William Morrow and Company.

- ^ «Remarks on a few «polyplural» classes in Bantu» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-11. Retrieved 2014-03-06.

- ^ Corbett 1991, p. 14.

General[edit]

- Craig, Colette G. (1986). Noun classes and categorization: Proceedings of a symposium on categorization and noun classification, Eugene, Oregon, October 1983. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins.

- Corbett, Greville G. (1991). Gender. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139166119. ISBN 9780521329392. – A comprehensive study; looks at 200 languages.

- Corbett, Geville (1994) «Gender and gender systems». En R. Asher (ed.) The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, Oxford: Pergamon Press, pp. 1347–1353.

- Greenberg, J. H. (1978) «How does a language acquire gender markers?». En J. H. Greenberg et al. (eds.) Universals of Human Language, Vol. 4, pp. 47–82.

- Hockett, Charles F. (1958) A Course in Modern Linguistics, Macmillan.

- Ibrahim, M. (1973) Grammatical gender. Its origin and development. La Haya: Mouton.

- Iturrioz, J. L. (1986) «Structure, meaning and function: a functional analysis of gender and other classificatory techniques». Función 1. 1-3.

- Meissner, Antje & Anne Storch (eds.) (2000) Nominal classification in African languages, Institut für Afrikanische Sprachwissenschaften, Johann-Wolfgang-Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. ISBN 3-89645-014-X.

- Ohly, R., Kraska-Szlenk, i., Podobińska, Z. (1998) Język suahili. Wydawnictwo Akademickie «Dialog». Warszawa. ISBN 83-86483-87-3

- Pinker, Steven (1994) The Language Instinct, William Morrow and Company.

- Мячина, Е.Н. (1987) Краткий грамматический очерк языка суахили. In: Суахили-русский словарь. Kamusi ya Kiswahili-Kirusi. Москва. «Русский Язык».

- SIL: Glossary of Linguistic Terms: What is a noun class?

External links[edit]

- World Atlas of Language Structures

-

- Global map and discussion of languages by type of noun class at WALS: Number of Genders

- Swahili

-

- Contini-Morava, Ellen. Noun Classification in Swahili. 1994.

- On nominal classes in Swahili