All strong writers have something in common: they understand the value of word choice in writing. Strong word choice uses vocabulary and language to maximum effect, creating clear moods and images and making your stories and poems more powerful and vivid.

The meaning of “word choice” may seem self-explanatory, but to truly transform your style and writing, we need to dissect the elements of choosing the right word. This article will explore what word choice is, and offer some examples of effective word choice, before giving you 5 word choice exercises to try for yourself.

Word Choice Definition: The Four Elements of Word Choice

The definition of word choice extends far beyond the simplicity of “choosing the right words.” Choosing the right word takes into consideration many different factors, and finding the word that packs the most punch requires both a great vocabulary and a great understanding of the nuances in English.

Choosing the right word involves the following four considerations, with word choice examples.

1. Meaning

Words can be chosen for one of two meanings: the denotative meaning or the connotative meaning. Denotation refers to the word’s basic, literal dictionary definition and usage. By contrast, connotation refers to how the word is being used in its given context: which of that word’s many uses, associations, and connections are being employed.

A word’s denotative meaning is its literal dictionary definition, while its connotative meaning is the web of uses and associations it carries in context.

We play with denotations and connotations all the time in colloquial English. As a simple example, when someone says “greaaaaaat” sarcastically, we know that what they’re referring to isn’t “great” at all. In context, the word “great” connotes its opposite: something so bad that calling it “great” is intentionally ridiculous. When we use words connotatively, we’re letting context drive the meaning of the sentence.

The rich web of connotations in language are crucial to all writing, and perhaps especially so to poetry, as in the following lines from Derek Walcott’s Nobel-prize-winning epic poem Omeros:

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez,

the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane

down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain

marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

Sugar cane isn’t, literally, made of “feathered lances,” which would literally denote “long metal spears adorned with bird feathers”; but feathered connotes “branching out,” the way sugar cane does, and lances connotes something tall, straight, and pointy, as sugar cane is. Together, those two words create a powerfully true visual image of sugar cane—in addition to establishing the martial language (“spears,” “marching”) used elsewhere in the passage.

Whether in poetry or prose, strong word choice can unlock images, emotions, and more in the reader, and the associations and connotations that words bring with them play a crucial role in this.

2. Specificity

Use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description.

In the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms. That’s why it’s important to use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description. Words like “good,” “average,” and “awful” are far less descriptive and specific than words like “liberating” (not just good but good and freeing), “C student” (not just average but academically average), and “despicable” (not just awful but morally awful). These latter words pack more meaning than their blander counterparts.

Since more precise words give the reader added context, specificity also opens the door for more poetic opportunities. Take the short poem “[You Fit Into Me]” by Margaret Atwood.

You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

A fish hook

An open eye

The first stanza feels almost romantic until we read the second stanza. By clarifying her language, Atwood creates a simple yet highly emotive duality.

This is also why writers like Stephen King advocate against the use of adverbs (adjectives that modify verbs or other adjectives, like “very”). If your language is precise, you don’t need adverbs to modify the verbs or adjectives, as those words are already doing enough work. Consider the following comparison:

Weak description with adverbs: He cooks quite badly; the food is almost always extremely overdone.

Strong description, no adverbs: He incinerates food.

Of course, non-specific words are sometimes the best word, too! These words are often colloquially used, so they’re great for writing description, writing through a first-person narrative, or for transitional passages of prose.

3. Audience

Good word choice takes the reader into consideration. You probably wouldn’t use words like “lugubrious” or “luculent” in a young adult novel, nor would you use words like “silly” or “wonky” in a legal document.

This is another way of saying that word choice conveys not only direct meaning, but also a web of associations and feelings that contribute to building the reader’s world. What world does the word “wonky” help build for your reader, and what world does the word “seditious” help build? Depending on the overall environment you’re working to create for the reader, either word could be perfect—or way out of place.

4. Style

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing. Every writer uses words differently, and as those words come to form poems, stories, and books, your unique grasp on the English language will be recognizable by all your readers.

Style isn’t something you can point to, but rather a way of describing how a writer writes. Ernest Hemingway, for example, is known for his terse, no-nonsense, to-the-point styles of description. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, is known for writing that’s poetic, intense, and melodramatic, and James Joyce for his lofty, superfluous writing style.

Here’s a paragraph from Joyce:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.

And here’s one from Hemingway:

Bill had gone into the bar. He was standing talking with Brett, who was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed. She had no stockings on.

Style is best observed and developed through a portfolio of writing. As you write more and form an identity as a writer, the bits of style in your writing will form constellations.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Word Choice in Writing: The Importance of Verbs

Before we offer some word choice exercises to expand your writing horizons, we first want to mention the importance of verbs. Verbs, as you may recall, are the “action” of the sentence—they describe what the subject of the sentence actually does. Unless you are intentionally breaking grammar rules, all sentences must have a verb, otherwise they don’t communicate much to the reader.

Because verbs are the most important part of the sentence, they are something you must focus on when expanding the reaches of your word choice. Verbs are the most widely variegated units of language; the more “things” you can do in the world, the more verbs there are to describe them, making them great vehicles for both figurative language and vivid description.

Consider the following three sentences:

- The road runs through the hills.

- The road curves through the hills.

- The road meanders through the hills.

Which sentence is the most descriptive? Though each of them has the same subject, object, and number of words, the third sentence creates the clearest image. The reader can visualize a road curving left and right through a hilly terrain, whereas the first two sentences require more thought to see clearly.

Finally, this resource on verb usage does a great job at highlighting how to invent and expand your verb choice.

Word Choice in Writing: Economy and Concision

Strong word choice means that every word you write packs a punch. As we’ve seen with adverbs above, you may find that your writing becomes more concise and economical—delivering more impact per word. Above all, you may find that you omit needless words.

Omit needless words is, in fact, a general order issued by Strunk and White in their classic Elements of Style. As they explain it:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

It’s worth repeating that this doesn’t mean your writing becomes clipped or terse, but simply that “every word tell.” As our word choice improves—as we omit needless words and express ourselves more precisely—our writing becomes richer, whether we write in long or short sentences.

As an example, here’s the opening sentence of a random personal essay from a high school test preparation handbook:

The world is filled with a numerous amount of student athletes that could somewhere down the road have a bright future.

Most words in this sentence are needless. It could be edited down to:

Many student athletes could have a bright future.

Now let’s take some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Can you remove a single word without sacrificing an enormous richness of meaning?

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In strong writing, every single word is chosen for maximum impact. This is the true meaning of concise or economical writing.

5 Word Choice Exercises to Sharpen Your Writing

With our word choice definition in mind, as well as our discussions of verb use and concision, let’s explore the following exercises to put theory into practice. As you play around with words in the following word choice exercises, be sure to consider meaning, specificity, style, and (if applicable) audience.

1. Build Moods With Word Choice

Writers fine-tune their words because the right vocabulary will build lush, emotive worlds. As you expand your word choice and consider the weight of each word, focus on targeting precise emotions in your descriptions and figurative language.

This kind of point is best illustrated through word choice examples. An example of magnificent language is the poem “In Defense of Small Towns” by Oliver de la Paz. The poem’s ambivalent feelings toward small hometowns presents itself through the mood of the writing.

The poem is filled with tense descriptions, like “animal deaths and toughened hay” and “breeches speared with oil and diesel,” which present the small town as stoic and masculine. This, reinforced by the terse stanzas and the rare “chances for forgiveness,” offers us a bleak view of the town; yet it’s still a town where everything is important, from “the outline of every leaf” to the weightless flight of cattail seeds.

The writing’s terse, heavy mood exists because of the poem’s juxtaposition of masculine and feminine words. The challenge of building a mood produces this poem’s gravity and sincerity.

Try to write a poem, or even a sentence, that evokes a particular mood through words that bring that word to mind. Here’s an example:

- What mood do you want to evoke? flighty

- What words feel like they evoke that mood? not sure, whatever, maybe, perhaps, tomorrow, sometimes, sigh

- Try it in a sentence: “Maybe tomorrow we could see about looking at the lab results.” She sighed. “Perhaps.”

2. Invent New Words and Terms

A common question writers ask is, What is one way to revise for word choice? One trick to try is to make up new language in your revisions.

If you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

In the same way that unusual verbs highlight the action and style of your story, inventing words that don’t exist can also create powerful diction. Of course, your writing shouldn’t overflow with made-up words and pretentious portmanteaus, but if you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

A great example of an invented word is the phrase “wine-dark sea.” Understanding this invention requires a bit of history; in short, Homer describes the sea as “οἶνοψ πόντος”, or “wine-faced.” “Wine-dark,” then, is a poetic translation, a kind of kenning for the sea’s mystery.

Why “wine-dark” specifically? Perhaps because, like the sea, wine changes us; maybe the eyes of the sea are dark, as eyes often darken with wine; perhaps the sea is like a face, an inversion, a reflection of the self. In its endlessness, we see what we normally cannot.

Thus, “wine-dark” is a poetic combination of words that leads to intensive literary analysis. For a less historical example, I’m currently working on my poetry thesis, with pop culture monsters being the central theme of the poems. In one poem, I describe love as being “frankensteined.” By using this monstrous made-up verb in place of “stitched,” the poem’s attitude toward love is much clearer.

Try inventing a word or phrase whose meaning will be as clear to the reader as “wine-dark sea.” Here’s an example:

- What do you want to describe? feeling sorry for yourself because you’ve been stressed out for a long time

- What are some words that this feeling brings up? self-pity, sympathy, sadness, stress, compassion, busyness, love, anxiety, pity party, feeling sorry for yourself

- What are some fun ways to combine these words? sadxiety, stresslove

- Try it in a sentence: As all-nighter wore on, my anxiety softened into sadxiety: still edgy, but soft in the middle.

3. Only Use Words of Certain Etymologies

One of the reasons that the English language is so large and inconsistent is that it borrows words from every language. When you dig back into the history of loanwords, the English language is incredibly interesting!

(For example, many of our legal terms, such as judge, jury, and plaintiff, come from French. When the Normans [old French-speakers from Northern France] conquered England, their language became the language of power and nobility, so we retained many of our legal terms from when the French ruled the British Isles.)

Nerdy linguistics aside, etymologies also make for a fun word choice exercise. Try forcing yourself to write a poem or a story only using words of certain etymologies and avoiding others. For example, if you’re only allowed to use nouns and verbs that we borrowed from the French, then you can’t use Anglo-Saxon nouns like “cow,” “swine,” or “chicken,” but you can use French loanwords like “beef,” “pork,” and “poultry.”

Experiment with word etymologies and see how they affect the mood of your writing. You might find this to be an impactful facet of your word choice. You can Google “__ etymology” for any word to see its origin, and “__ synonym” to see synonyms.

Try writing a sentence only with roots from a single origin. (You can ignore common words like “the,” “a,” “of,” and so on.)

- What do you want to write? The apple rolled off the table.

- Try a first etymology: German: The apple wobbled off the bench.

- Try a second: Latin: The russet fruit rolled off the table.

4. Write in E-Prime

E-Prime Writing describes a writing style where you only write using the active voice. By eschewing all forms of the verb “to be”—using words such as “is,” “am,” “are,” “was,” and other “being” verbs—your writing should feel more clear, active, and precise!

E-Prime not only removes the passive voice (“The bottle was picked up by James”), but it gets at the reality that many sentences using to be are weakly constructed, even if they’re technically in the active voice.

Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

Try writing a paragraph in E-Prime:

- What do you want to write? Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

- Converted to E-Prime: Of course, E-Prime writing won’t best suit every project. The above paragraph uses E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would carry challenges. E-Prime writing endeavors to make all of your subjects active, and your verbs more impactful. While this word choice exercise can bring enjoyment and create memorable language, you probably can’t sustain it over a long writing project.

5. Write Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry, also known as Found Poetry, is a visual creative writing project. You take a page from a published source and create a poem by blacking out other words until your circled words create a new poem. The challenge is that you’re limited to the words on a page, so you need a charged use of both space and language to make a compelling blackout poem.

Blackout poetry bottoms out our list of great word choice exercises because it forces you to consider the elements of word choice. With blackout poems, certain words might be read connotatively rather than denotatively, or you might change the meaning and specificity of a word by using other words nearby. Language is at its most fluid and interpretive in blackout poems!

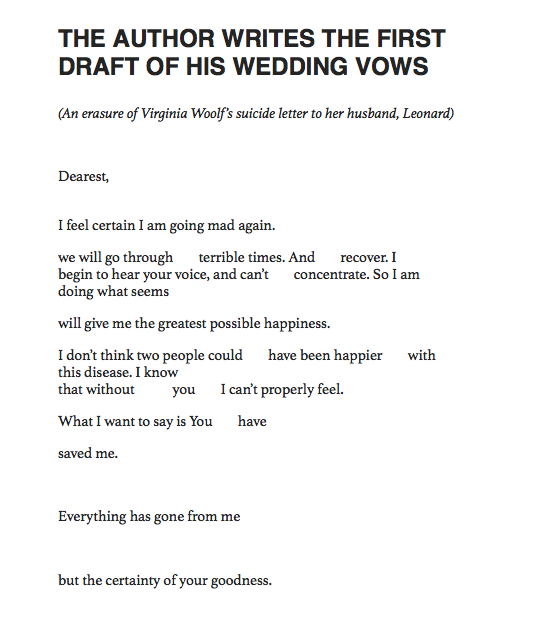

For a great word choice example using blackout poetry, read “The Author Writes the First Draft of His Wedding Vows” by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib. Here it is visually:

Source: https://decreation.tumblr.com/post/620222983530807296/from-the-crown-aint-worth-much-by-hanif

Pick a favorite poem of your own and make something completely new out of it using blackout poetry.

How to Expand Your Vocabulary

Vocabulary is a last topic in word choice. The more words in your arsenal, the better. Great word choice doesn’t rely on a large vocabulary, but knowing more words will always help! So, how do you expand your vocabulary?

The simplest way to expand your vocabulary is by reading.

The simplest answer, and the one you’ll hear the most often, is by reading. The more literature you consume, the more examples you’ll see of great words using the four elements of word choice.

Of course, there are also some great programs for expanding your vocabulary as well. If you’re looking to use words like “lachrymose” in a sentence, take a look at the following vocab builders:

- Dictionary.com’s Word-of-the-Day

- Vocabulary.com Games

- Merriam Webster’s Vocab Quizzes

Improve Your Word Choice With Writers.com’s Online Writing Courses

Looking for more writing exercises? Need more help choosing the right words? The instructors at Writers.com are masters of the craft. Take a look at our upcoming course offerings and join our community!

The words a writer chooses are the building materials from which he or she constructs any given piece of writing—from a poem to a speech to a thesis on thermonuclear dynamics. Strong, carefully chosen words (also known as diction) ensure that the finished work is cohesive and imparts the meaning or information the author intended. Weak word choice creates confusion and dooms a writer’s work either to fall short of expectations or fail to make its point entirely.

Factors That Influence Good Word Choice

When selecting words to achieve the maximum desired effect, a writer must take a number of factors into consideration:

- Meaning: Words can be chosen for either their denotative meaning, which is the definition you’d find in a dictionary or the connotative meaning, which is the emotions, circumstances, or descriptive variations the word evokes.

- Specificity: Words that are concrete rather than abstract are more powerful in certain types of writing, specifically academic works and works of nonfiction. However, abstract words can be powerful tools when creating poetry, fiction, or persuasive rhetoric.

- Audience: Whether the writer seeks to engage, amuse, entertain, inform, or even incite anger, the audience is the person or persons for whom a piece of work is intended.

- Level of Diction: The level of diction an author chooses directly relates to the intended audience. Diction is classified into four levels of language:

- Formal which denotes serious discourse

- Informal which denotes relaxed but polite conversation

- Colloquial which denotes language in everyday usage

- Slang which denotes new, often highly informal words and phrases that evolve as a result sociolinguistic constructs such as age, class, wealth status, ethnicity, nationality, and regional dialects.

- Tone: Tone is an author’s attitude toward a topic. When employed effectively, tone—be it contempt, awe, agreement, or outrage—is a powerful tool that writers use to achieve a desired goal or purpose.

- Style: Word choice is an essential element in the style of any writer. While his or her audience may play a role in the stylistic choices a writer makes, style is the unique voice that sets one writer apart from another.

The Appropriate Words for a Given Audience

To be effective, a writer must choose words based on a number of factors that relate directly to the audience for whom a piece of work is intended. For example, the language chosen for a dissertation on advanced algebra would not only contain jargon specific to that field of study; the writer would also have the expectation that the intended reader possessed an advanced level of understanding in the given subject matter that at a minimum equaled, or potentially outpaced his or her own.

On the other hand, an author writing a children’s book would choose age-appropriate words that kids could understand and relate to. Likewise, while a contemporary playwright is likely to use slang and colloquialism to connect with the audience, an art historian would likely use more formal language to describe a piece of work about which he or she is writing, especially if the intended audience is a peer or academic group.

«Choosing words that are too difficult, too technical, or too easy for your receiver can be a communication barrier. If words are too difficult or too technical, the receiver may not understand them; if words are too simple, the reader could become bored or be insulted. In either case, the message falls short of meeting its goals . . . Word choice is also a consideration when communicating with receivers for whom English is not the primary language [who] may not be familiar with colloquial English.»

(From «Business Communication, 8th Edition,» by A.C. Krizan, Patricia Merrier, Joyce P. Logan, and Karen Williams. South-Western Cengage, 2011)

Word Selection for Composition

Word choice is an essential element for any student learning to write effectively. Appropriate word choice allows students to display their knowledge, not just about English, but with regard to any given field of study from science and mathematics to civics and history.

Fast Facts: Six Principles of Word Choice for Composition

- Choose understandable words.

- Use specific, precise words.

- Choose strong words.

- Emphasize positive words.

- Avoid overused words.

- Avoid obsolete words.

(Adapted from «Business Communication, 8th Edition,» by A.C. Krizan, Patricia Merrier, Joyce P. Logan, and Karen Williams. South-Western Cengage, 2011)

The challenge for teachers of composition is to help students understand the reasoning behind the specific word choices they’ve made and then letting the students know whether or not those choices work. Simply telling a student something doesn’t make sense or is awkwardly phrased won’t help that student become a better writer. If a student’s word choice is weak, inaccurate, or clichéd, a good teacher will not only explain how they went wrong but ask the student to rethink his or her choices based on the given feedback.

Word Choice for Literature

Arguably, choosing effective words when writing literature is more complicated than choosing words for composition writing. First, a writer must consider the constraints for the chosen discipline in which they are writing. Since literary pursuits as such as poetry and fiction can be broken down into an almost endless variety of niches, genres, and subgenres, this alone can be daunting. In addition, writers must also be able to distinguish themselves from other writers by selecting a vocabulary that creates and sustains a style that is authentic to their own voice.

When writing for a literary audience, individual taste is yet another huge determining factor with regard to which writer a reader considers a «good» and who they may find intolerable. That’s because «good» is subjective. For example, William Faulker and Ernest Hemmingway were both considered giants of 20th-century American literature, and yet their styles of writing could not be more different. Someone who adores Faulkner’s languorous stream-of-consciousness style may disdain Hemmingway’s spare, staccato, unembellished prose, and vice versa.

Download Article

Download Article

Word choice, or diction, is an essential part of any type of writing, and learning to use better word choice can greatly improve your creative writing! The more you think about your diction and practice using better word choice in your stories, the more naturally it will come. We’ve compiled this list of tips and tricks to help you start choosing even better words for your next story.

-

Reading regularly increases your vocabulary. In other words, you’ll know more words to choose from when you write stories. Read whatever is interesting and enjoyable to you, whether it’s fiction, non-fiction, short stories, novels, books, or articles. Add variety to what you read to expose yourself to different styles of diction.[1]

- Even if you typically read crime novels and you want to write crime fiction, it’s still a good idea to switch up what you read to expand your vocabulary outside your comfort zone. For example, you could read a sci-fi or fantasy novel once in a while.[2]

- You can even listen to audiobooks when you’re on the go to get your daily reading in!

- Even if you typically read crime novels and you want to write crime fiction, it’s still a good idea to switch up what you read to expand your vocabulary outside your comfort zone. For example, you could read a sci-fi or fantasy novel once in a while.[2]

Advertisement

-

There are lots of free writing apps that can help you improve your diction.[3]

Download some different ones and try them out when you write. Writing apps help you with the basics like spelling and grammar, but they also make word suggestions and offer alternative sentence structures.[4]

- To find writing apps, search online or in an app store for “writing apps.” Look for ones that have good user ratings and reviews.

- For example, there’s an app called Hemingway that helps you write more like Ernest Hemingway by highlighting sentences that are too long or dense, words that are too complicated, and unnecessary adverbs.

- Some other apps to try are Grammarly, Word to Word, OneLook Reverse Dictionary, and Vocabulary.com.

- There are also vocabulary apps that teach you a word a day to help you further expand your vocab.

-

Variety is the spice of life—and of writing. Highlight words that you use often when you write to identify where you can add some different word choices. Look up synonyms for those words in a thesaurus or brainstorm other ways to convey the meaning you want to get across. Change some of the words and sentences to add more variety to your story.[5]

- When you’re writing on a computer, use CTRL+F to search for and highlight different words.

- Reading a draft out loud can also help you identify passages that are repetitive.

- It’s an especially good idea to eliminate repetition of weak, non-descriptive words, such as “stuff,” “things,” “it,”and “got.” For example, replace “got” with “received,” “obtained,” or “acquired.”

Advertisement

-

This helps convey what you’re really trying to make readers feel. Replace neutral words with alternatives that have positive or negative emotional connotations. One word changes the entire connotation of a sentence or passage.[6]

- For example, replace the word “looked” with “glared” to convey feelings of anger. Or, replace it with “gawked” to convey feelings of disbelief or awe.

- Keep in mind that stronger words aren’t always a better choice than simpler ones. Always consider the message you want to get across when you’re choosing words. In some cases, “looked” may be perfectly adequate!

-

More precise words give the reader better context. Try to replace basic adverbs and adjectives with more descriptive words. Think of other ways you can describe people, places, and things to paint a better picture in the reader’s imagination.[7]

- For example, instead of saying “he was a very average player,” say something like “he was a bench warmer,” which gives the reader an image of the player spending most games sitting on the bench instead of just being an average player on the field.

- Here’s another example: instead of writing “she has a tendency to overcook rice,” write “the rice almost always ends up charred when she cooks it.” The reader can now picture what the rice actually looks like and maybe even imagine the taste of charred rice.

Advertisement

-

Verbs, or the action of a sentence, really bring your writing to life. Come up with 2-3 different verbs that you could use in a given sentence. Choose the best, most descriptive verb for each sentence to make your writing more vivid for the reader.[8]

- For example, instead of writing “the river comes down from the mountains,” write “the river winds down from the mountains.” Changing “comes” to “winds” helps the reader visualize a river bending from left to right as the water flows down from the mountains, instead of just giving them a vague idea of where the body of water is.

-

This can be especially helpful when you write character dialogue or thoughts. Think about how certain characters would talk or think about things in real life. Write sentences that actually sound like those characters in terms of formality.[9]

- For instance, a farmer from the deep south in the USA probably wouldn’t say “she was quite mad when I showed up late.” The man would probably speak more informally and with slang. He might say something like “she was right ticked when I got home!”

Advertisement

-

Getting rid of unnecessary words keeps your writing clear and concise. Keep an eye out for wordy sentences and try to replace them with a fewer number of words that say the same thing. Some of the most highly regarded authors, like Hemingway, are known for using short, to-the-point sentences in their writing.[10]

- For example, instead of writing “I came to the conclusion that…” write “I concluded that…” By removing 3 words from that sentence, you get your point across to the reader faster and more clearly.

-

Describing things in other ways is more impactful than using clichés. If you write something that comes to mind immediately, but it sounds familiar, that might be a warning sign that it’s a cliché. If you catch yourself writing a phrase you’ve seen a lot in other writing, pause and think of a different way to say what you mean. Try to rewrite the phrase in a shorter, more original way.[11]

- For example, instead of saying “he was as dead as a door nail,” you could just say “he was dead” to get your point across without using a played-out cliché. Or, if you want to be more descriptive, say something like “he was as dead and as cold as a rock.”

- Another example of a cliché that appears in lots of writing is: “A single tear trickled down her cheek.”

Advertisement

-

It’s totally fine if you get stuck with a phrase you’re not happy with. Mark it in your draft and come back to revise it later on. Give your mind a rest and search for inspiration, then rewrite it when you have an alternative that you know is better.[12]

- In other words, don’t feel like you have to choose the best words all the time when you write the first draft of a story. That’s why it’s called a “rough” draft!

Add New Question

-

Question

I’m really awful at describing things. Any tips?

Silvana Haynes

Community Answer

There is a pattern for description, for example the method of » Simile+ adjectives, verb with adverb following- into the- adjectives, personification, «with» description and movement words. For example: Like a ball, the blubbery, sizeable tomato lunged swiftly into the lofty plumb tree that lay before it, it frantically darted across the field with its navy green stem as it hung tightly onto the iridescent meadow. If you want, you can search up synonyms for similar words.

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

About This Article

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 24,736 times.

Did this article help you?

Word choice is a critical component of good writing.

Have you ever read a sentence and wondered what it was trying to say? Ever gotten hung up on a word that felt out of place because the meaning of the word didn’t fit the context? When was the last time you spotted a word that was unnecessarily repeated throughout a page, chapter, or book?

There are two sides to any piece of writing. The first is the message, idea, or story. The other side is the craft of stringing words together into sentences and using sentences to build paragraphs. Adept writing flows smoothy and makes sense. Readers shouldn’t have to stop and dissect sentences or get hung up on words that are repetitive or confusing.

Which is why word choice is such an important skill for any writer to possess.

Common Word-Choice Mistakes

The right word can make or break a sentence. If we want our prose to be rich, vibrant, and meaningful, then we need to develop a robust vocabulary. As we write, revise, and proofread, there are plenty of common word-choice mistakes to watch out for. If we can catch those mistakes and fix them, we’ll end up with better writing.

Here are some word-choice to mistakes to watch out for in your writing:

Repetition: When the same words and phrases are repeated in a short space, they act like clichés, becoming tiresome and meaningless. Some words have to be repeated, especially articles, prepositions, and conjunctions. If we’re writing a story set on a submarine, the word submarine (or sub) will get repeated frequently. That’s to be expected. However, repetitive descriptive words get monotonous. Every girl is pretty, every stride is long, everybody taps their keyboards. The fix: look for words that can be replaced with synonyms or alternative wording and avoid using the same descriptive words over and over again.

Connotation: With all the synonyms available, choosing the right word can be a challenge. Each word has a meaning, but most words also have connotations, which skew the meaning in a particular direction. Connotations are implied or emotional undertones that flavor a word’s meaning. If your character is going home, there is a much different implication than if the character is going to her house. The fix: when choosing synonyms, consider the connotation and emotional flavor of each option.

Precision: The best word choices are specific. One word will be vague and nondescript while another will be vivid and descriptive. Consider the following sentences:

He wrote a poem on a piece of paper.

He wrote a poem on a sheet of vellum.

The second sentence is more visual because the word choice (vellum) is more precise. The fix: whenever possible, choose the most precise word available.

Simplicity: Readers don’t want to have to run to the dictionary to get through a page of your writing, and most don’t appreciate the haughtiness that erudite writing evokes. If you’re writing to a highbrow audience, then by all means, feel free to pontificate, but to reach a wider audience, make your language accessible. The fix: check your text for rare and long words, and if you can replace them with more common or shorter words, do it.

Musicality: Sometimes, word choice comes down to musicality. How does one word sound in your sentence as opposed to another? If you’re trying to choose between words like bin and container, you might make your decision based on which word sounds better in the sentence. The fix: read sentences and paragraphs aloud to see how different words sound.

Thoughtful Word Choices for Better Writing

Whether you agonize over word choice while you’re drafting or during revisions, there are some incredibly useful tools for making word choice a breeze. In addition to using the tools that are at your disposal, consistently working to expand your vocabulary will do wonders for improving your language and word-choice skills:

- The thesaurus and the dictionary are your friends. Use them (especially the thesaurus).

- Read voraciously. Nothing will improve your writing and your vocabulary as well as the simple act of reading.

- Read and write poetry. Poems are full of vivacious words. You’ll develop a knack for word choice and grow a bountiful vocabulary if you study a little poetry.

- Play word games like Scrabble, Scattergories, and Words with Friends, which force you to actively use your vocabulary.

- Sign up for Word of the Day and commit to learning 365 words over the next year.

Have you ever gotten frustrated by reading a book that was peppered with poor word choices? Do you make a conscious effort to use the right words in your writing? How far will you go to find the perfect word for a sentence? Share your thoughts on how thoughtful word choices result in better writing by leaving a comment, and keep writing!

For every author, making informed word choices while writing a paper is paramount to their success. While writing a manuscript, you frequently and meticulously select words that let you express your ideas with utmost clarity. Subsequently, you determine a befitting way to regroup those words into phrases, sentences, and at times, paragraphs. Therefore, it is always prudent to be aware of and eschew from errors in word usage that could affect the clarity of your manuscript.

Here are a few of the most frequent mistakes when it comes to word choice:

Incorrectly used words

Original version: Everyone complemented Chloé Baker for winning the Nobel Peace Prize.

Revised version: Everyone complimented Chloé Baker for winning the Nobel Peace Prize.

Reason for revision: “Complement” means something that completes or adds further features to something else, whereas “Compliment” means to praise someone.

Words with undesirable implications or meanings

Original version: I sprayed the caterpillars in their personal zones.

Revised version: I sprayed the caterpillars in their hiding zones.

Reason for revision: The original version has a word (personal) that can be interpreted in two ways. The revised version communicates the intended meaning with clarity.

Complicated words in place of a simpler/shorter term

Original version: No one was convinced that her story wasn’t apocryphal.

Revised version: No one was convinced that her story wasn’t untrue.

Reason for revision: The original version has a complicated word (apocryphal); the revised version replaces it with a simpler and shorter word—untrue.

Awkward words

Original version: High school athletes’ inclination towards sports science in the 21st century is in total contrast with the attitude shared by the previous generation.

Revised version: The inclination towards sports science among the high school athletes in the 21st century is in total contrast with the attitude shared by the previous generation.

Reason for revision: The italicized phrase in the original version is difficult to read, and a little unclear, whereas the revised version is easily comprehensible.

Similar meaning words used in the wrong context

Original version: As the number of cholera patients skyrocketed during the winter, the doctors worked overtime to hastily treat as many patients as possible to avoid any patients missing out on treatment.

Revised version: As the number of cholera patients skyrocketed during the winter, the doctors worked overtime to promptly treat as many patients as possible to avoid any patients missing out on treatment.

Reason for revision: “Hastily” is similar to “promptly,” but in the context of medical care for a serious disease, the word “hastily” is inappropriate as it can easily mean “speed with recklessness.”

Words that communicate nuances of meaning

Original version: A conversation between the presidents of both countries is necessary to avoid further escalation of the precarious political situation.

Revised version: A discourse between the Presidents of both countries is necessary to avoid further escalation of the precarious political situation.

Reason for revision: The word “conversation” isn’t suitable considering the seriousness of the matter. “Discourse” is more suitable, given the gravity and formal nature of the situation.

Furthermore, it is best to figure out the most effective way to convey your message succinctly in academic writing. Here are a few notable examples:

|

Longer phrase |

The concise word |

| Shown beyond doubt | Proven |

| From my standpoint | Personally |

| In the course of | During |

| On the assumption that | If |

| After a period of time | Afterward |

| At the same time | Though |

| For the reason that | Because |

| On all occasions | Always |

| A number of | Several |

| Throughout the world | Worldwide |

| In the ancient past | Historically |

| At that point in time | Then |

| Leading up to | Before |

| All Things Considered | Considering |

These are a few tips to make sure you always select the correct words when writing an academic paper and avoid the mistakes enlisted in the article:

-

- Always check the meaning of unfamiliar words before using them in your manuscript, for instance, nonplussed, admonish, arcane, esoteric, expunge, phlegmatic, platitude, quixotic.

- Avoid using fancy words to impress the reader/reviewer with your extensive vocabulary. It’s a strategy that can backfire, and it also makes the reading experience unnecessarily difficult. For instance, use “optimistic” instead of “sanguine”; use “breeze” instead of “zephyr.”

- Make sure you use accurate phrasing. For instance, instead of “the pasty doctor,” use “the pale obstetrician.”

- Whenever possible, avoid repetition. For instance, instead of “new innovations,” use “innovations”; instead of “revert back,” simply write “revert.”

And if you are looking for a proven tool to enhance your writing dynamically, then try out Trinka, the world’s first language enhancement tool that is custom-built for academic and technical writing. It has several exclusive features to make your manuscript ready for the global audience.

If you’ve been writing for any length of time at all, you know that word choice is crucial. I’ve written professionally for 15 years and word choice still sometimes stumps me.

What is a non-specific word choice?

A non-specific word choice is a word choice that is vague and does not convey a sense of the specific details. Non-specific word choices include generic words like “thing,” “stuff,” “them,” or “that.”

The best way to learn about non-specific word choice is to see actual examples. That’s why I’ve included a table of clear examples below so that you can understand without any confusion.

Keep reading to learn when and how to use non-specific word choice, and seven simple ways to fix non-specific word choice in your writing.

My favorite tool for quickly improving, rephrasing, simplifying, or expanding my writing is by far the Jasper AI Writer (formerly known as Jarvis).

(This post may have afilliate links. Please see my full disclosure)

I thought it might be helpful to include a table of examples of non-specific word choices. I’ll bold the non-specific word choice so they stand out.

Study this table so that you absorb all the variations.

By doing so, you’ll be able to identify non-specific word choices in your writing—whether in essays, emails, reports, papers, articles, or stories.

| Example Sentence | Non-Specific Word |

|---|---|

| I want that. | That |

| She went to the place. | Place |

| A person called me. | Person |

| Meet me at the location. | Location |

| This happened long ago. | This |

| Everyone came to the party. | Everyone |

| He walked the animal. | Animal |

| You should go to the event. | Event |

| The vehicle drove away. | Vehicle |

| I’ll be in the room. | Room |

| It has become very clear that… | It |

| There are several reasons to believe. | Reasons |

| The evidence is clear. | Evidence |

| We can rely on the results. | Results |

| The presentation was informative. | Presentation |

| He is able to attend the meetings. | Meetings |

| The project is developing smoothly. | Project |

| She needs support from people at work. | People |

| Their team will be doing an important job. | Job |

| Everybody participated and shared their ideas and knowledge. | Everybody |

Please note that these sentences include non-specific words mostly because they exist in isolation.

Yes, you can improve most of the sentences with a bit more specifics, however, some of the sentences might work in the context of a larger, more specific paragraph offering the reader details.

How To Easily Spot a Non-Specific Word Choice

The easiest way to spot a non-specific word choice is to ask a simple question of all of your sentences.

The simple question is, “What detail is missing?”

Here are other variations of this question you might want to use:

- Who exactly?

- Where exactly?

- When exactly?

- What exactly?

Let’s look at an example. Suppose you write the sentence, “I can’t stand the person!” Since this sentence is about a person, you can ask, “Who exactly?” As in, “Who exactly can’t you stand?”

The identity of the person in the sentence is not identified, so someone eavesdropping on the conversation would not understand your meaning. To fix this sentence, you could change it to read, “I can’t stand Chad!”

Now, anyone listening knows you don’t like Chad, specifically. They might know Chad, but you are still writing a clear and defined sentence.

Is Non-Specific Word Choice Bad?

By now, you might be wondering if using non-specific word choice is always bad. The answer is no.

There are times to use non-specific words and times you probably want to avoid vague or unclear words. It really depends on the context. In school, teachers often focus on writing more specific sentences.

That’s why many of us mistakenly believe specific is always better.

It’s also true that writing with more detail is often the correct choice. Most of the time, adding specific information to clarify your meaning improves your writing.

However, this is not always the case, every time.

Since I want you to master non-specific word choice, we’re going to look at when to use it to maximize your writing.

When To Use Non-Specific Word Choice? (9 Best Times)

There are writing circumstances where non-specific word choice is preferred over specific word choice.

Here’s a quick list of some of these circumstances:

- When you intentionally want your meaning to be vague

- When you want to create mystery or suspense

- When knowing the details would ruin a later surprise

- When the details don’t matter

- When you have already mentioned the details earlier (so there’s no need to repeat them in every sentence)

- When the reader (or person receiving your writing) knows what you mean

- When you speak in slang or jargon for privacy or confedentiality

- When a character in your story speaks in non-specific sentences (part of their characterization)

- When a character in your story is intentionally being unclear or vague

You might notice that the common denominator in all of these reasons is intention. Only use non-specific words on purpose.

Also, check out this related video on word choice:

When To Use Specific Word Choice?

There are also times to use specific word choices. As I mentioned earlier, MOST of the time, you want to write more detailed sentences. Most writing suffers from a lack of clarity, not over-specificity.

When to use specific word choices?

I agree with Mark Twain who once famously said, “The difference between the right word and the wrong word is the difference between lightning and lightning bug.”

Word choice matters.

Here are seven times you should use specific word choices:

- When you want the best short word

- When you want the most evocative word

- When you want a contrasting word

- When you want a concrete word

- When you need the most clear word

- When you prefer a lyrical word

- When you want to find the “right” word

We’re going to take each of these reasons one at a time.

Why you should use short words

You should use short words because short words are simple and short sentences are often more effective.

Short words also increase the speed at which you write and communicate. Short sentences force clarity. Short, simple words can improve your technical writing, help your readers understand what you’re saying, and make your writing more enjoyable for everyone involved.

Short, hyper-specific words also pack more punch.

Example: Use “fox” instead of animal and “sin” instead of wrongdoing.

Why you should use evocative words

You should use evocative words because evocative words generate emotion through meaning and association (shame, baby, funeral).

Not all writing requires emotion or visceral reactions (say, a work autoresponder email message letting your colleagues know you’re on vacation).

However, for most nontechnical writing, a little emotion can go a long way. Specific words can be very evocative.

Example: The first time I laid eyes on my baby, my soul swooned.

Why you should use contrast words

You should use contrast words because they grab attention with an odd pairing: wet sand, cold fire, beautiful atrocity.

Applying contrast words in your writing can simultaneously elevate and deepen your writing.

At its core, contrast makes for better writing by creating interest and drama by pairing seemingly incompatible ideas.

For example, the sound of shouting or the sound of silence.

Why you should use concrete words

Concrete words are visual, sensory words that lend to showing, not telling. Instead of saying something is “good” or “beautiful,” you can say that it’s “wide-eyed and bright-faced.”

Instead of telling the reader that a character is nervous, you can describe the jittery dance of his fingers.

Concrete words invoke concrete images.

Examples: Shards of glass. Shattered hoof.

Why you should use clear words

Clear words improve understanding and convey accurate meaning. Keeping clear words in your writing will help retain the interest of readers. Clear word choice also reduces confusion and improves retention.

Example: Tuesday, November 13th, instead of “next week.”

Why you should use lyrical words

Lyrical words flow, lilt, and play music in the “ear” of the reader. They are lyrical because they sound musical, sing-songy, or melodious. However, they tend to be more subtle. They create sounds or images in the “mind’s ear” of your readers.

Lyrical words paint pictures that stretch the imagination and imbue your writing with a sense of sound.

Example: Prose, serendipity, facetious.

Why you should use the “right” words

The “right” words are words that best fit into the collective narrative of the sentence. When writing, you have to consider the “tone of voice” or how you want the sentence or scene to feel (to the reader).

If a sentence is light-hearted and funny, then the words used should match that tone. If a sentence is serious and strict, then the words should match that tone as well.

Always consider the context of the sentence, paragraph, page, scene, and story. As an editor once told me, “beautiful girls don’t ‘plop’.”

Final Thoughts: What Is a Non-Specific Word Choice?

The bottom line is that a non-specific word choice is unclear. It’s a barrier to good communication. You can immediately improve most sentences by making them more clear.

My secret sauce for writing that gets results is Jasper (AI Writer formerly known as Jarvis).

Yes, it still takes your skill and guidance, but it’s hands-down the best way to quickly scale your writing production and improve your results. Jasper helps you write emails, essays, papers, reports, articles, even books. Click on the image below to check out what Jasper can do for you!

For more articles on writing, read these blog posts next:

- How To Write Jasper/Jarvis Blog Posts (7 Best Tips)

- Stephen King Twitter (9 Things You Need To Know)

- Is Medium Worth It? (SOLVED for Readers and Writers)

Resources:

Writers.com

Word choice: Hidden Meaning

Chapter 17 Word Choice

Everyone’s a Wordsmith

If you are going to write for either personal or professional reasons, you should carefully choose your words. Make sure your words say what you mean by controlling wordiness, using appropriate language, choosing precise wording, and using a dictionary or thesaurus effectively.

17.1 Controlling Wordiness and Writing Concisely

Learning Objectives

- Recognize and eliminate repetitive ideas.

- Recognize and remove unneeded repeated words.

- Recognize unneeded words and revise sentences to be more concise.

It is easy to let your sentences become cluttered with words that do not add value to what you are trying to say. You can manage cluttered sentences by eliminating repetitive ideas, removing repeated words, and rewording to eliminate unneeded words.

Eliminating Repetitive Ideas

Unless you are providing definitions on purpose, stating one idea in two ways within a single sentence is redundant and not necessary. Read each example and think about how you could revise the sentence to remove repetitive phrasing that adds wordiness. Then study the suggested revision below each example.

Examples

Original: Use a very heavy skillet made of cast iron to bake an extra juicy meatloaf.

Revision: Use a cast iron skillet to bake a very juicy meatloaf.

Original: Joe thought to himself, “I think I’ll make caramelized grilled salmon tonight.”

Revision: Joe thought, “I think I’ll make caramelized grilled salmon tonight.”

Removing Repeated Words

As a general rule, you should try not to repeat a word within a sentence. Sometimes you simply need to choose a different word. But often you can actually remove repeated words. Read this example and think about how you could revise the sentence to remove a repeated word that adds wordiness. Then check out the revision below the sentence.

Example

Original: The student who won the cooking contest is a very talented and ambitious student.

Revision: The student who won the cooking contest is very talented and ambitious.

Rewording to Eliminate Unneeded Words

If a sentence has words that are not necessary to carry the meaning, those words are unneeded and can be removed to reduce wordiness. Read each example and think about how you could revise the sentence to remove phrasing that adds wordiness. Then check out the suggested revisions to each sentence.

Examples

Original: Andy has the ability to make the most fabulous twice-baked potatoes.

Revision: Andy makes the most fabulous twice-baked potatoes.

Original: For his part in the cooking class group project, Malik was responsible for making the mustard reduction sauce.

Revision: Malik made the mustard reduction sauce for his cooking class group project.

Key Takeaways

- State ideas only once within a single sentence, as opposed to repeating a key idea in an attempt to clarify.

- Avoid unnecessarily repeating words within a sentence.

- Write concisely by eliminating unneeded words.

Exercise

-

Rewrite the following sentences by eliminating unneeded words.

- I was late because of the fact that I could not leave the house until such time as my mother was ready to go.

- I used a pair of hot pads to remove the hot dishes from the oven.

- The bus arrived at 7:40 a.m., I got on the bus at 7:41 a.m., and I was getting off the bus by 7:49 a.m.

- The surface of the clean glass sparkled.

17.2 Using Appropriate Language

Learning Objectives

- Be aware that some words are commonly confused with each other.

- Recognize and use appropriate words, taking care to avoid jargon or slang.

- Write in a straightforward manner and with the appropriate level of formality.

As a writer, you do not want inappropriate word choice to get in the way of your message. For this reason, you need to strive to use language that is accurate and appropriate for the writing situation. Learn for yourself which words you tend to confuse with each other. Omit jargonVocabulary of a special group or profession. (technical words and phrases common to a specific profession or discipline) and slangPlayful, informal vocabulary, often recently invented and specific to a certain group. (invented words and phrases specific to a certain group of people), unless your audience and purpose call for such language. Avoid using outdated words and phrases, such as “dial the number.” Be straightforward in your writing rather than using euphemismsSubstitution with a gentler way of expressing something. (a gentler, but sometimes inaccurate, way of saying something). Be clear about the level of formality needed for each different piece of writing and adhere to that level.

Focusing on Easily Confused Words

Words in homophone sets are often mistaken for each other. (See Chapter 19 «Mechanics», Section 19.1.3 «Homophones» for more about homophones.) Table 17.1 «Commonly Confused Words» presents some examples of commonly confused words other than homophones. You will notice that some of the words in the table have similar sounds that lead to their confusion. Other words in the table are confused due to similar meanings. Keep your personal list handy as you discover pairings of words that give you trouble.

Table 17.1 Commonly Confused Words

| affect | effect | good | well | |

| all ready | already | lay | lie | |

| allusion | illusion | leave | let | |

| among | between | ordinance | ordnance | |

| are | our | precede | proceed | |

| award | reward | quiet | quite | |

| breath | breathe | quote | quotation | |

| can | may | sit | set | |

| conscience | conscious | statue | statute | |

| desert | dessert | that | which | |

| emigrate | immigrate | through | thorough | |

| especially | specially | who | whom | |

| explicit | implicit |

Writing without Jargon or Slang

Jargon and slang both have their places. Using jargon is fine as long as you can safely assume your readers also know the jargon. For example, if you are a lawyer, and you are writing to others in the legal profession, using legal jargon is perfectly fine. On the other hand, if you are writing for people outside the legal profession, using legal jargon would most likely be confusing, and you should avoid it. Of course, lawyers must use legal jargon in papers they prepare for customers. However, those papers are designed to navigate within the legal system.

You are, of course, free to use slang within your personal life, but unless you happen to be writing a sociolinguistic study of slang itself, it really has no place in academic writing. Even if you are writing somewhat casual responses in an online discussion for a class, you should avoid using slang or other forms of abbreviated communication common to IM (instant messaging) and texting.

Choosing to Be Straightforward

Some writers choose to control meaning with flowery or pretentious language, euphemisms, and double-talkTalk that includes extra verbiage in an effort to camouflage the message.. All these choices obscure direct communication and therefore have no place in academic writing. Study the following three examples that clarify each of these misdirection techniques.

| Technique | Example | Misdirection Involved | Straightforward Alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flowery or pretentious language | Your delightful invitation arrived completely out of the blue, and I would absolutely love to attend such a significant and important event, but we already have a commitment. | The speaker seems to be trying very hard to relay serious regrets for having to refuse an invitation. But the overkill makes it sound insincere. | We are really sorry, but we have a prior commitment. I hope you have a great event. |

| Euphemisms | My father is follicly challenged. | The speaker wants to talk about his or her father’s lack of hair without having to use the word “bald.” | My father is bald. |

| Double-talk | I was unavoidably detained from arriving to the evening meeting on time because I became preoccupied with one of my colleagues after the close of the work day. | The speaker was busy with a colleague after work and is trying to explain being tardy for an evening meeting. | I’m sorry to be late to the meeting. Work ran later than usual. |

Presenting an Appropriate Level of Formality

Look at the following three sentences. They all three carry roughly the same meaning. Which one is the best way to write the sentence?

- The doctor said, “A full eight hours of work is going to be too much for this patient to handle for at least the next two weeks.”

- The doctor said I couldn’t work full days for the next two weeks.

- my md said 8 hrs of wrk R 2M2H for the next 2 wks.

If you said, “It depends,” you are right! Each version is appropriate in certain situations. Every writing situation requires you to make a judgment regarding the level of formality you want to use. Base your decision on a combination of the subject matter, the audience, and your purpose for writing. For example, if you are sending a text message to a friend about going bowling, the formality shown in example three is fine. If, on the other hand, you are sending a text message to that same friend about the death of a mutual friend, you would logically move up the formality of your tone at least to the level of example two.

Key Takeaways

- Some words are confused because they sound alike, look alike, or both. Others are confused based on similar meanings.

- Confine use of jargon to situations where your audience recognizes it.

- Use slang and unofficial words only in your informal, personal writing.

- Write in a straightforward way without using euphemisms or flowery language to disguise what you are saying.

- Make sure you examine the subject matter, audience, and purpose to determine whether a piece of writing should be informal, somewhat casual, or formal.

Exercises

- Choose five of the commonly confused words from Table 17.1 «Commonly Confused Words» that are sometimes problems for you. Write a definition for each word and use each word in a sentence.

- Start a computer file of words that are a problem for you. For each word, write a definition and a sentence. Add to the file whenever you come across another word that is confusing for you. Use the file for a quick reference when you are writing.

- List five examples of jargon from a field of your choice. Then list two situations in which you could use the jargon and two situations in which you should not use the jargon.

- Work with a small group. Make a list of at least fifty slang words or phrases. For each word or phrase, indicate where, as a college student, you could properly use the slang. Share your final project with the class.

- Work with a partner. Write five sentences that include euphemisms or flowery language. Then trade papers and rewrite your partner’s sentences using straightforward language.

- Make a list of five situations where you should use very formal writing and five situations where more casual or even very informal writing would be acceptable.

17.3 Choosing Precise Wording

Learning Objectives

- Understand connotations of words and choose words with connotations that work best for your purposes.

- Incorporate specific and concrete words as well as figurative language into your writing.

- Recognize and avoid clichés and improperly used words.

By using precise wording, you can most accurately relay your thoughts. Some strategies that can help you put your thoughts into words include focusing on denotations and connotations, balancing specific and concrete words with occasionally figurative language, and being on guard against clichés and misused words.

Focusing on Both Denotations and Connotations

Consider that the words “laid-back” and “lackadaisical” both mean “unhurried and slow-moving.” If someone said you were a “laid-back” student, you would likely be just fine with that comment, but if someone said you were a “lackadaisical” student, you might not like the connotationThe emotional sense of a word; the various ways in which it can be received by a listener or reader.. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs all have both denotationsThe definition of a word. and connotations. The denotation is the definition of a word. The connotation is the emotional sense of a word. For example, look at these three words:

- excited

- agitated

- flustered

The three words all mean to be stirred emotionally. In fact, you might see one of the words as a definition of another one of them. And you would definitely see the three words in a common list in a thesaurus. So the denotations for the three words are about the same. But the connotations are quite different. The word “excited” often has a positive, fun underlying meaning; “agitated” carries a sense of being upset; and “flustered” suggests a person is somewhat out of control. When you are choosing a word to use, you should first think of a word based on its denotation. Then you should consider if the connotation fits your intent. For more on using a dictionary or thesaurus to enhance and add precision to your word choices, see Section 17.4 «Using the Dictionary and Thesaurus Effectively».

Choosing Specific and Concrete Words

You will always give clearer information if you write with specific wordsA detail within a category (e.g., cat within the category animals). rather than general wordsA category (e.g., animals).. Look at the following example and think about how you could reword it using specific terms. Then check out the following revision to see one possible option.

Examples

Original: The animals got out and ruined the garden produce.

Revision: The horses got out and ruined the tomatoes and cucumbers.

Another way to make your writing clearer and more interesting is to use concrete wordsA word that evokes a physical sense such as taste, smell, hearing, sight, or touch. rather than abstract wordsA word that does not have physical properties.. Abstract words do not have physical properties. But concrete words evoke senses of taste, smell, hearing, sight, and touch. For example, you could say, “My shoe feels odd.” This statement does not give a sense of why your shoe feels odd since odd is an abstract word that doesn’t suggest any physical characteristics. Or you could say, “My shoe feels wet.” This statement gives you a sense of how your shoe feels to the touch. It also gives a sense of how your shoe might look as well as how it might smell. Look at the following example and think about how you could reword it using concrete words. Then check out the following revision to see one possible option.

Examples

Original: The horses got out and ruined the tomatoes and cucumbers.

Revision: The horses stampeded out and squished and squirted the tomatoes and cucumbers.

Study this table for some additional examples of words that provide clarity to writing.

| General Words | Specific Words |

|---|---|

| children | Tess and Abby |

| animals | dogs |

| food | cheeseburger and a salad |

| Abstract Words | Concrete Words |

|---|---|

| noise | clanging and squealing |

| success | a job I like and enough money to live comfortably |

| civility | treating others with respect |

Enhancing Writing with Figurative Language

Figurative languageA writing tool that plays on the senses, creates special effects, or both. is a general term that includes writing tools such as alliterationRepetition of single letters or sets of letters., analogiesThe comparison of familiar and unfamiliar ideas or items by showing a feature they have in common., hyperboleA greatly exaggerated point., idiomsA group of words that carries a meaning other than the actual meanings of the words., metaphorsAn overall comparison of two ideas or items by stating that one is the other., onomatopoeiaA single word that sounds like the idea it is describing., personificationAttributing human characteristics to nonhuman things., and similesUsing the word “like” or “as” to indicate that one item or idea resembles another.. By using figurative language, you can make your writing both more interesting and easier to understand.

Figurative Language

Alliteration: Repetition of single letters or sets of letters.

Effect: Gives a poetic, flowing sound to words.

Example: Dana danced down the drive daintily.

Analogy: The comparison of familiar and unfamiliar ideas or items by showing a feature they have in common.

Effect: Makes an unfamiliar idea or item easier to understand.

Example: Writing a book is like raising a toddler. It takes all your time and attention, but you’ll enjoy every minute of it!

Hyperbole: A greatly exaggerated point.

Effect: Emphasizes the point.

Example: I must have written a thousand pages this weekend.

Idiom: A group of words that carries a meaning other than the actual meanings of the words.

Effect: A colorful way to send a message.

Example: I think this assignment will be a piece of cake.

Metaphor: An overall comparison of two ideas or items by stating that one is the other.

Effect: Adds the connotations of one compared idea to the other compared idea.

Example: This shirt is a rag.

Onomatopoeia: A single word that sounds like the idea it is describing.

Effect: A colorful way to describe an idea while adding a sense of sound.

Example: The jazz band was known for its wailing horns and clattering drums.

Personification: Attributing human characteristics to nonhuman things.

Effect: Adds depth such as humor, drama, or interest.

Example: The spatula told me that the grill was just a little too hot today.

Simile: Using the word “like” or “as” to indicate that one item or idea resembles another.

Effect: A colorful way to explain an item or idea.

Example: Hanging out with you is like eating watermelon on a summer day.

Using Clichés Sparingly

ClichésA phrase that was once an original and interesting creation but that became so often used that it has ceased to be interesting and is now viewed as overworked. are phrases that were once original and interesting creations but that became so often used that they have ceased to be interesting and are now viewed as overworked. If you have a tendency to use a cliché or see one while you are proofreading, replace it with plain language instead.

Example

I’m loose as a goose today.

Replace cliché: I’m very relaxed today.

Table 17.2 A Few Common Clichés

| as fresh as a daisy | as slow as molasses | as white as snow |

| beat around the bush | being led down the primrose path | big as life |

| bottomless pit | busy as a bee | can’t see the forest for the trees |

| chip off the old block | dead of winter | dirt cheap |

| don’t upset the apple cart | down to earth | flat as a pancake |

| for everything there is a season | from feast to famine | go with the flow |

| gone to pot | green with envy | growing like a weed |

| heaven on earth | here’s mud in your eye | in a nutshell |

| in the doghouse | just a drop in the bucket | knock on wood |

| light as a feather | like a duck out of water | made in the shade |

| muddy the water | naked as a jaybird | nutty as a fruitcake |

| old as dirt | our neck of the woods | plain as the nose on your face |

| raking in the dough | sick as a dog | stick in the mud |

| stubborn as a mule | sweet as apple pie | thorn in my side |

| two peas in a pod | under the weather | walks on water |

| water under the bridge | when pigs fly |

Guarding against Misusing Words

If you are uncertain about the meaning of a word, look the word up before you use it. Also, if your spellchecker identifies a misspelled word, don’t automatically accept the suggested replacement word. Make an informed decision about each word you use.

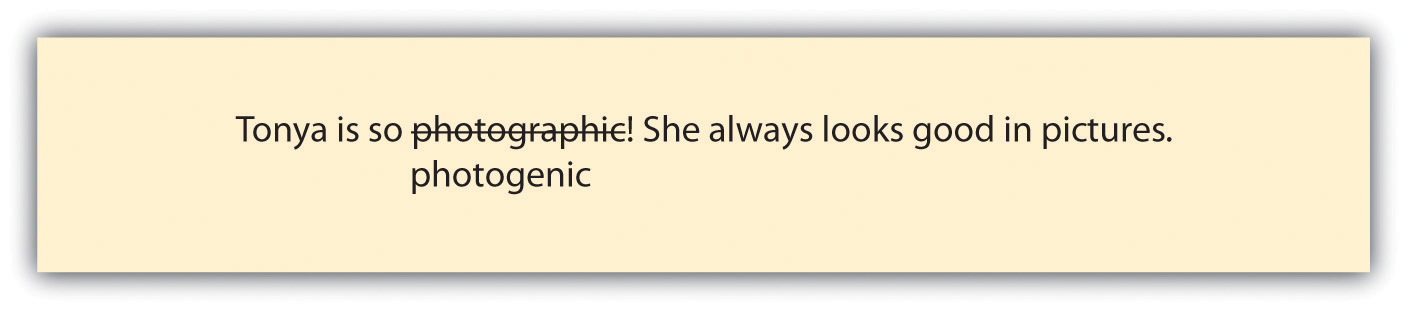

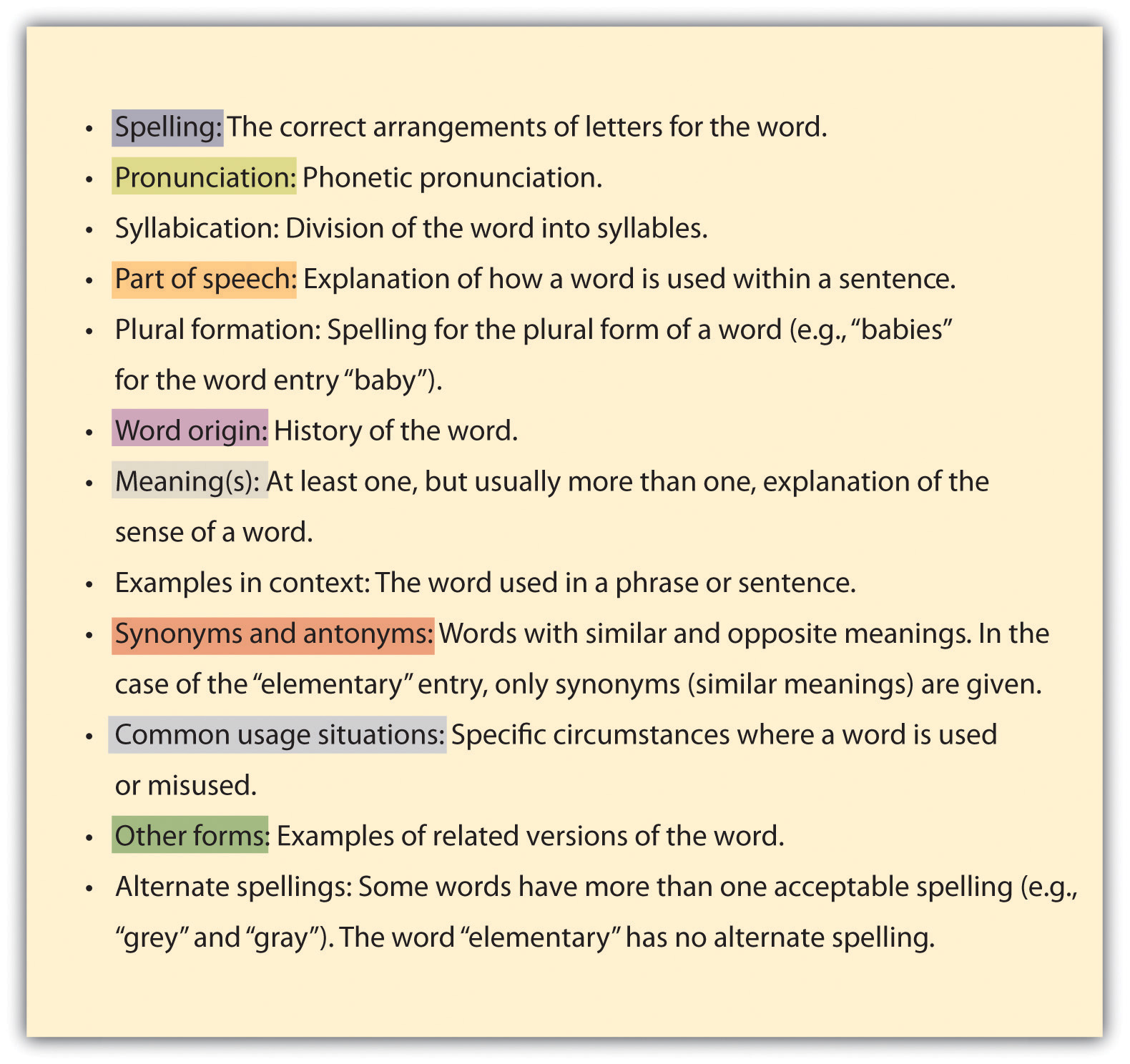

Look at the Figure 17.1.

Figure 17.1

Equipment and memories can be photographic, but to look good in pictures is to be photogenic. To catch an error of this nature, you clearly have to realize the word in question is a problem. The truth is, your best chance at knowing how a wide range of words should be used is to read widely and frequently and to pay attention to words as you read.

Key Takeaways

- Words have both denotations and connotations, and you need to focus on both of these meanings when you choose your words.

- Specific words, such as “fork” or “spoon” instead of “silverware,” and concrete words, such as a “piercing siren” instead of a “loud sound,” create more interesting writing.

- Figurative language, including alliteration, analogies, hyperbole, idioms metaphors, onomatopoeia, personification, and similes, helps make text more interesting and meaningful.

- Both clichés and improperly used words detract from your writing. Reword clichés using straightforward language. Eliminate improperly used words by researching words about which you are not sure.

Exercises

-

Fill in the blank in this sentence with a word that carries a connotation suggesting Kelly was still full of energy after her twenty laps:

Kelly ____ out of the pool at the end of her twenty laps.

-

Identify the general word used in this sentence and replace it with a specific word:

I put my clothes somewhere and can’t find them.

-

Identify the abstract word used in this sentence and replace it with a concrete word:

I smelled something strong when I opened the refrigerator door.

-

Identify the cliché used in the following sentence and rewrite the sentence using straightforward language:

We should be up and running by ten o’clock tomorrow morning.

-

Identify the misused word in the following sentence and replace it with a correct word:

I’d rather walk then have to wait an hour for the bus.

- Write a sentence using one of the types of figurative language presented in Section 17.3.3 «Enhancing Writing with Figurative Language».

- Over the course of a week, record any instances of clichés or trite, overused expressions you hear in conversations with friends, coworkers, or family; in music, magazines, or newspapers; on television, film, or the Internet; or in your own language. Share your list with members of your group or the class as a whole.

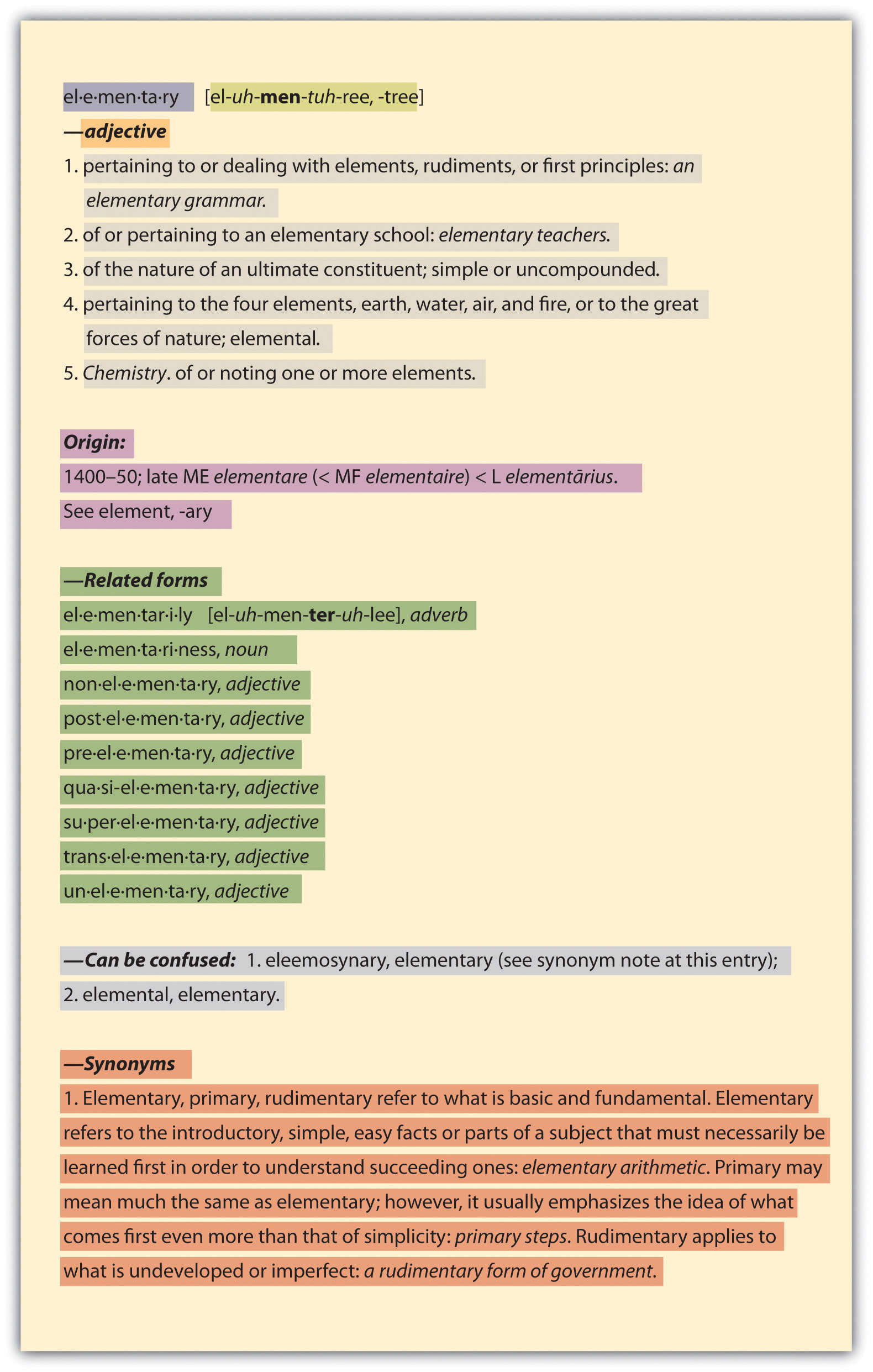

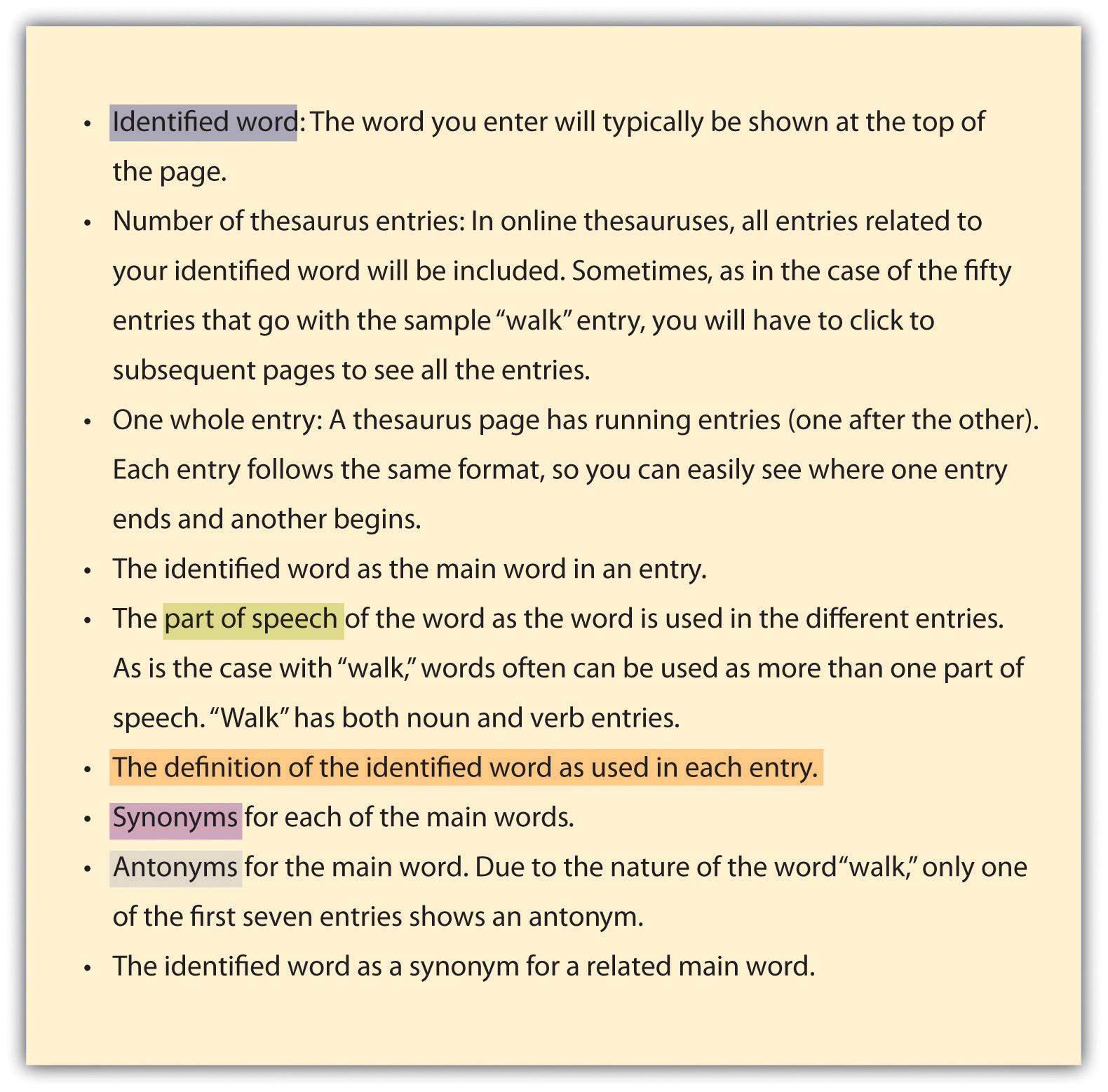

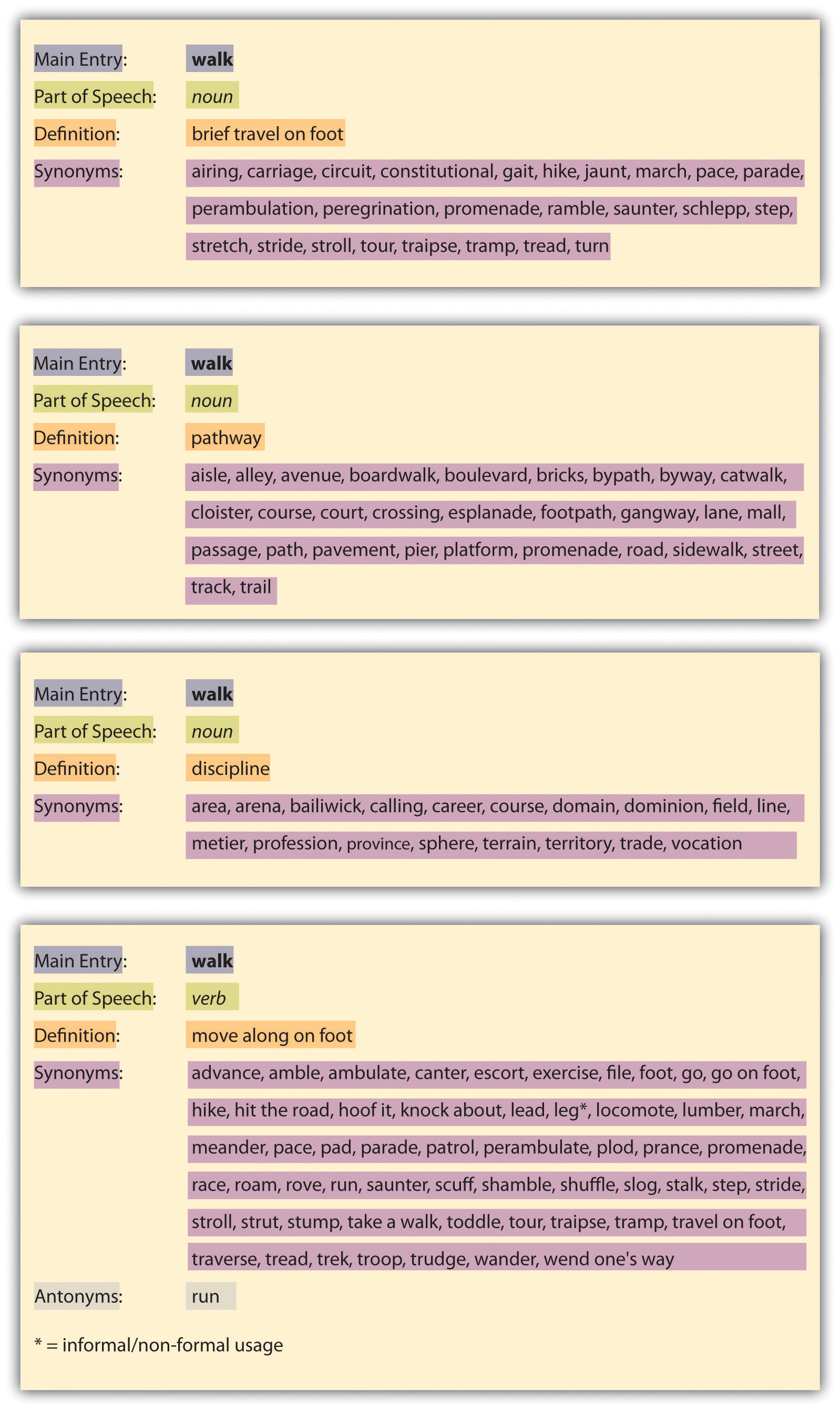

17.4 Using the Dictionary and Thesaurus Effectively

Learning Objectives

- Understand the information available in a dictionary entry.

- Understand the benefits and potential pitfalls of a thesaurus.

- Use dictionaries and thesauruses as writing tools.