Table of Contents

- Why are the words an author chooses so important?

- How can interpreting an author’s information into your own words help your audience understand your topic?

- Which term describes the particular way in which an author chooses words and forms them into sentences?

- What happen if proper diction is not observed?

- What is the purpose of diction?

- What are the 4 types of diction?

- Is diction a word choice?

- Which is the most likely effect of an ending that was not foreshadowed?

- Which option is best example of hyperbole?

- Which sentence contains an example of foreshadowing Elsa?

- Which sentence is an example of an inciting incident?

- Which sentence contains a dangling modifier?

- Which words should be changed to make the sentence more appropriate for a general audience?

- When writing for a general audience Students should choose words that are technical?

- Which sentence contains a nonrestrictive clause and is punctuated correctly?

- When writing for a general audience the writer should keep in mind?

- How do you identify your audience in writing?

- What are the different types of audiences in writing?

- What are the 5 types of audiences?

Diction: An author’s choice of words. Since words have specific meanings, and since one’s choice of words can affect feelings, a writer’s choice of words can have great impact in a literary work.

An authors choice of words authors words have significant meaning so their choice of words can have a significant effect on feelings creates tone imagery etc. The substitution of a mild or less negative word or phrase for a harsh one. Upon may also cause confusion between two cents of the same written or spoken word.

How can interpreting an author’s information into your own words help your audience understand your topic?

Answer: Doing this can help the audience understand your topic more because they can see your opinion, rather somebody else´s. It is better said in your words, because maybe some of your audience has heard the same words from the same topic. Using your own perspective makes things more interesting.

Which term describes the particular way in which an author chooses words and forms them into sentences?

Diction is simply the words the writer chooses to convey a particular meaning. When analyzing diction, look for specific words or short phrases that seem stronger than the others (ex.

What happen if proper diction is not observed?

Answer: If improper diction or poor choice of words and phrases is not observed, there will be a misunderstanding between the reader and the author. The point of view of the author wouldn’t be delivered very well to the reader and the reader might give the phrase another meaning.

What is the purpose of diction?

Diction refers to a writer’s purposeful word choice. Along with syntax, diction can be used to create tone and imagery in creative writing. Think about your writing’s purpose and the message you want to convey. Naturally, your choice of words for a persuasive piece will be quite different from a poem about heartbreak.

What are the 4 types of diction?

There are eight common types of diction:

- Formal diction. Formal diction is the use of sophisticated language, without slang or colloquialisms.

- Informal diction.

- Pedantic diction.

- Colloquial diction.

- Slang diction.

- Abstract diction.

- Concrete diction.

- Poetic diction.

Is diction a word choice?

Diction is word choice. When writing, use vocabulary suited for the type of assignment. Words that have almost the same denotation (dictionary meaning) can have very different connotations (implied meanings).

Which is the most likely effect of an ending that was not foreshadowed?

If the ending is not foreshadowed, readers will be surprised because there were no former hints leading up to it. The reader may feel confused, as the ending will be out of the blue with no prior explanation.

Which option is best example of hyperbole?

Hyperbole can be defined as a figure of speech that uses extreme exaggeration for dramatic effect and that is not meant to be taken literally. Taking into account this definition, we may say that the best example of hyperbole is D. Stalin’s reference to Hitler throwing soldiers onto the battlefield.

Which sentence contains an example of foreshadowing Elsa?

The sentence that contains an example of foreshadowing is: A. Elsa hears a report that the buses are running late as she rushes out the door to an important meeting. Explanation: The above sentence is an example of foreshadowing because it gives a hint that something will happen in the story.

Which sentence is an example of an inciting incident?

The sentence which stands as an example of an inciting incident in American Born Chinese is: B. The guard won’t let the Monkey King into the party because he is a monkey.An inciting incident is a definite point, an event of a plot which leads to a particular conflict and makes an emphasis on it.

Which sentence contains a dangling modifier?

The sentence that contains a dangling modifier is C. Dressed in a snowsuit, the cold weather did not bother the child. Explanation: A dangling modifier refers to a word or phrase that modifies a word that has not been clearly stated in the sentence.

Which words should be changed to make the sentence more appropriate for a general audience?

Explanation: When writing for general audiences, we should choose words that are conversational. That means adapting our writing to make sure people in general can understand the message, instead of focusing on a group of people with specific vocabulary.

When writing for a general audience Students should choose words that are technical?

When writing for a general audience, students should choose words that are technical. O conversational.

Which sentence contains a nonrestrictive clause and is punctuated correctly?

Answer. The correct sentence is – The teacher packed picnic lunches for all the students—which they loved—and ate lunch outside with them at recess. A nonrestrictive clause is a type of adjective clause offering additional detail on a word that already has a specific meaning.

When writing for a general audience the writer should keep in mind?

When writing for a general audience,the writer should keep in mind that a general audience most likely •knows little about the topic. knows a lot about the topic.

How do you identify your audience in writing?

Determining Your Audience

- One of the first questions you should ask yourself is, “Who are the readers?”

- Decide what your readers know or think they know about your subject.

- Next, ask yourself “What will my readers expect from my writing?”

- You also need to consider how you can interest your readers in your subject.

What are the different types of audiences in writing?

Three categories of audience are the “lay” audience, the “managerial” audience, and the “experts.” The “lay” audience has no special or expert knowledge.

What are the 5 types of audiences?

Let’s take a look at the 5 types of audiences in writing and what that means for your writing approach today.

- Audience #1 – The Experts.

- Audience #2 – The Laypeople.

- Audience #3 – The Managers.

- Audience #4 – The Technicians.

- Audience #5 – The Hybrids.

The words a writer chooses are the building materials from which he or she constructs any given piece of writing—from a poem to a speech to a thesis on thermonuclear dynamics. Strong, carefully chosen words (also known as diction) ensure that the finished work is cohesive and imparts the meaning or information the author intended. Weak word choice creates confusion and dooms a writer’s work either to fall short of expectations or fail to make its point entirely.

Factors That Influence Good Word Choice

When selecting words to achieve the maximum desired effect, a writer must take a number of factors into consideration:

- Meaning: Words can be chosen for either their denotative meaning, which is the definition you’d find in a dictionary or the connotative meaning, which is the emotions, circumstances, or descriptive variations the word evokes.

- Specificity: Words that are concrete rather than abstract are more powerful in certain types of writing, specifically academic works and works of nonfiction. However, abstract words can be powerful tools when creating poetry, fiction, or persuasive rhetoric.

- Audience: Whether the writer seeks to engage, amuse, entertain, inform, or even incite anger, the audience is the person or persons for whom a piece of work is intended.

- Level of Diction: The level of diction an author chooses directly relates to the intended audience. Diction is classified into four levels of language:

- Formal which denotes serious discourse

- Informal which denotes relaxed but polite conversation

- Colloquial which denotes language in everyday usage

- Slang which denotes new, often highly informal words and phrases that evolve as a result sociolinguistic constructs such as age, class, wealth status, ethnicity, nationality, and regional dialects.

- Tone: Tone is an author’s attitude toward a topic. When employed effectively, tone—be it contempt, awe, agreement, or outrage—is a powerful tool that writers use to achieve a desired goal or purpose.

- Style: Word choice is an essential element in the style of any writer. While his or her audience may play a role in the stylistic choices a writer makes, style is the unique voice that sets one writer apart from another.

The Appropriate Words for a Given Audience

To be effective, a writer must choose words based on a number of factors that relate directly to the audience for whom a piece of work is intended. For example, the language chosen for a dissertation on advanced algebra would not only contain jargon specific to that field of study; the writer would also have the expectation that the intended reader possessed an advanced level of understanding in the given subject matter that at a minimum equaled, or potentially outpaced his or her own.

On the other hand, an author writing a children’s book would choose age-appropriate words that kids could understand and relate to. Likewise, while a contemporary playwright is likely to use slang and colloquialism to connect with the audience, an art historian would likely use more formal language to describe a piece of work about which he or she is writing, especially if the intended audience is a peer or academic group.

«Choosing words that are too difficult, too technical, or too easy for your receiver can be a communication barrier. If words are too difficult or too technical, the receiver may not understand them; if words are too simple, the reader could become bored or be insulted. In either case, the message falls short of meeting its goals . . . Word choice is also a consideration when communicating with receivers for whom English is not the primary language [who] may not be familiar with colloquial English.»

(From «Business Communication, 8th Edition,» by A.C. Krizan, Patricia Merrier, Joyce P. Logan, and Karen Williams. South-Western Cengage, 2011)

Word Selection for Composition

Word choice is an essential element for any student learning to write effectively. Appropriate word choice allows students to display their knowledge, not just about English, but with regard to any given field of study from science and mathematics to civics and history.

Fast Facts: Six Principles of Word Choice for Composition

- Choose understandable words.

- Use specific, precise words.

- Choose strong words.

- Emphasize positive words.

- Avoid overused words.

- Avoid obsolete words.

(Adapted from «Business Communication, 8th Edition,» by A.C. Krizan, Patricia Merrier, Joyce P. Logan, and Karen Williams. South-Western Cengage, 2011)

The challenge for teachers of composition is to help students understand the reasoning behind the specific word choices they’ve made and then letting the students know whether or not those choices work. Simply telling a student something doesn’t make sense or is awkwardly phrased won’t help that student become a better writer. If a student’s word choice is weak, inaccurate, or clichéd, a good teacher will not only explain how they went wrong but ask the student to rethink his or her choices based on the given feedback.

Word Choice for Literature

Arguably, choosing effective words when writing literature is more complicated than choosing words for composition writing. First, a writer must consider the constraints for the chosen discipline in which they are writing. Since literary pursuits as such as poetry and fiction can be broken down into an almost endless variety of niches, genres, and subgenres, this alone can be daunting. In addition, writers must also be able to distinguish themselves from other writers by selecting a vocabulary that creates and sustains a style that is authentic to their own voice.

When writing for a literary audience, individual taste is yet another huge determining factor with regard to which writer a reader considers a «good» and who they may find intolerable. That’s because «good» is subjective. For example, William Faulker and Ernest Hemmingway were both considered giants of 20th-century American literature, and yet their styles of writing could not be more different. Someone who adores Faulkner’s languorous stream-of-consciousness style may disdain Hemmingway’s spare, staccato, unembellished prose, and vice versa.

All strong writers have something in common: they understand the value of word choice in writing. Strong word choice uses vocabulary and language to maximum effect, creating clear moods and images and making your stories and poems more powerful and vivid.

The meaning of “word choice” may seem self-explanatory, but to truly transform your style and writing, we need to dissect the elements of choosing the right word. This article will explore what word choice is, and offer some examples of effective word choice, before giving you 5 word choice exercises to try for yourself.

Word Choice Definition: The Four Elements of Word Choice

The definition of word choice extends far beyond the simplicity of “choosing the right words.” Choosing the right word takes into consideration many different factors, and finding the word that packs the most punch requires both a great vocabulary and a great understanding of the nuances in English.

Choosing the right word involves the following four considerations, with word choice examples.

1. Meaning

Words can be chosen for one of two meanings: the denotative meaning or the connotative meaning. Denotation refers to the word’s basic, literal dictionary definition and usage. By contrast, connotation refers to how the word is being used in its given context: which of that word’s many uses, associations, and connections are being employed.

A word’s denotative meaning is its literal dictionary definition, while its connotative meaning is the web of uses and associations it carries in context.

We play with denotations and connotations all the time in colloquial English. As a simple example, when someone says “greaaaaaat” sarcastically, we know that what they’re referring to isn’t “great” at all. In context, the word “great” connotes its opposite: something so bad that calling it “great” is intentionally ridiculous. When we use words connotatively, we’re letting context drive the meaning of the sentence.

The rich web of connotations in language are crucial to all writing, and perhaps especially so to poetry, as in the following lines from Derek Walcott’s Nobel-prize-winning epic poem Omeros:

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez,

the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane

down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain

marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

Sugar cane isn’t, literally, made of “feathered lances,” which would literally denote “long metal spears adorned with bird feathers”; but feathered connotes “branching out,” the way sugar cane does, and lances connotes something tall, straight, and pointy, as sugar cane is. Together, those two words create a powerfully true visual image of sugar cane—in addition to establishing the martial language (“spears,” “marching”) used elsewhere in the passage.

Whether in poetry or prose, strong word choice can unlock images, emotions, and more in the reader, and the associations and connotations that words bring with them play a crucial role in this.

2. Specificity

Use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description.

In the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms. That’s why it’s important to use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description. Words like “good,” “average,” and “awful” are far less descriptive and specific than words like “liberating” (not just good but good and freeing), “C student” (not just average but academically average), and “despicable” (not just awful but morally awful). These latter words pack more meaning than their blander counterparts.

Since more precise words give the reader added context, specificity also opens the door for more poetic opportunities. Take the short poem “[You Fit Into Me]” by Margaret Atwood.

You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

A fish hook

An open eye

The first stanza feels almost romantic until we read the second stanza. By clarifying her language, Atwood creates a simple yet highly emotive duality.

This is also why writers like Stephen King advocate against the use of adverbs (adjectives that modify verbs or other adjectives, like “very”). If your language is precise, you don’t need adverbs to modify the verbs or adjectives, as those words are already doing enough work. Consider the following comparison:

Weak description with adverbs: He cooks quite badly; the food is almost always extremely overdone.

Strong description, no adverbs: He incinerates food.

Of course, non-specific words are sometimes the best word, too! These words are often colloquially used, so they’re great for writing description, writing through a first-person narrative, or for transitional passages of prose.

3. Audience

Good word choice takes the reader into consideration. You probably wouldn’t use words like “lugubrious” or “luculent” in a young adult novel, nor would you use words like “silly” or “wonky” in a legal document.

This is another way of saying that word choice conveys not only direct meaning, but also a web of associations and feelings that contribute to building the reader’s world. What world does the word “wonky” help build for your reader, and what world does the word “seditious” help build? Depending on the overall environment you’re working to create for the reader, either word could be perfect—or way out of place.

4. Style

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing. Every writer uses words differently, and as those words come to form poems, stories, and books, your unique grasp on the English language will be recognizable by all your readers.

Style isn’t something you can point to, but rather a way of describing how a writer writes. Ernest Hemingway, for example, is known for his terse, no-nonsense, to-the-point styles of description. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, is known for writing that’s poetic, intense, and melodramatic, and James Joyce for his lofty, superfluous writing style.

Here’s a paragraph from Joyce:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.

And here’s one from Hemingway:

Bill had gone into the bar. He was standing talking with Brett, who was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed. She had no stockings on.

Style is best observed and developed through a portfolio of writing. As you write more and form an identity as a writer, the bits of style in your writing will form constellations.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Word Choice in Writing: The Importance of Verbs

Before we offer some word choice exercises to expand your writing horizons, we first want to mention the importance of verbs. Verbs, as you may recall, are the “action” of the sentence—they describe what the subject of the sentence actually does. Unless you are intentionally breaking grammar rules, all sentences must have a verb, otherwise they don’t communicate much to the reader.

Because verbs are the most important part of the sentence, they are something you must focus on when expanding the reaches of your word choice. Verbs are the most widely variegated units of language; the more “things” you can do in the world, the more verbs there are to describe them, making them great vehicles for both figurative language and vivid description.

Consider the following three sentences:

- The road runs through the hills.

- The road curves through the hills.

- The road meanders through the hills.

Which sentence is the most descriptive? Though each of them has the same subject, object, and number of words, the third sentence creates the clearest image. The reader can visualize a road curving left and right through a hilly terrain, whereas the first two sentences require more thought to see clearly.

Finally, this resource on verb usage does a great job at highlighting how to invent and expand your verb choice.

Word Choice in Writing: Economy and Concision

Strong word choice means that every word you write packs a punch. As we’ve seen with adverbs above, you may find that your writing becomes more concise and economical—delivering more impact per word. Above all, you may find that you omit needless words.

Omit needless words is, in fact, a general order issued by Strunk and White in their classic Elements of Style. As they explain it:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

It’s worth repeating that this doesn’t mean your writing becomes clipped or terse, but simply that “every word tell.” As our word choice improves—as we omit needless words and express ourselves more precisely—our writing becomes richer, whether we write in long or short sentences.

As an example, here’s the opening sentence of a random personal essay from a high school test preparation handbook:

The world is filled with a numerous amount of student athletes that could somewhere down the road have a bright future.

Most words in this sentence are needless. It could be edited down to:

Many student athletes could have a bright future.

Now let’s take some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Can you remove a single word without sacrificing an enormous richness of meaning?

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In strong writing, every single word is chosen for maximum impact. This is the true meaning of concise or economical writing.

5 Word Choice Exercises to Sharpen Your Writing

With our word choice definition in mind, as well as our discussions of verb use and concision, let’s explore the following exercises to put theory into practice. As you play around with words in the following word choice exercises, be sure to consider meaning, specificity, style, and (if applicable) audience.

1. Build Moods With Word Choice

Writers fine-tune their words because the right vocabulary will build lush, emotive worlds. As you expand your word choice and consider the weight of each word, focus on targeting precise emotions in your descriptions and figurative language.

This kind of point is best illustrated through word choice examples. An example of magnificent language is the poem “In Defense of Small Towns” by Oliver de la Paz. The poem’s ambivalent feelings toward small hometowns presents itself through the mood of the writing.

The poem is filled with tense descriptions, like “animal deaths and toughened hay” and “breeches speared with oil and diesel,” which present the small town as stoic and masculine. This, reinforced by the terse stanzas and the rare “chances for forgiveness,” offers us a bleak view of the town; yet it’s still a town where everything is important, from “the outline of every leaf” to the weightless flight of cattail seeds.

The writing’s terse, heavy mood exists because of the poem’s juxtaposition of masculine and feminine words. The challenge of building a mood produces this poem’s gravity and sincerity.

Try to write a poem, or even a sentence, that evokes a particular mood through words that bring that word to mind. Here’s an example:

- What mood do you want to evoke? flighty

- What words feel like they evoke that mood? not sure, whatever, maybe, perhaps, tomorrow, sometimes, sigh

- Try it in a sentence: “Maybe tomorrow we could see about looking at the lab results.” She sighed. “Perhaps.”

2. Invent New Words and Terms

A common question writers ask is, What is one way to revise for word choice? One trick to try is to make up new language in your revisions.

If you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

In the same way that unusual verbs highlight the action and style of your story, inventing words that don’t exist can also create powerful diction. Of course, your writing shouldn’t overflow with made-up words and pretentious portmanteaus, but if you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

A great example of an invented word is the phrase “wine-dark sea.” Understanding this invention requires a bit of history; in short, Homer describes the sea as “οἶνοψ πόντος”, or “wine-faced.” “Wine-dark,” then, is a poetic translation, a kind of kenning for the sea’s mystery.

Why “wine-dark” specifically? Perhaps because, like the sea, wine changes us; maybe the eyes of the sea are dark, as eyes often darken with wine; perhaps the sea is like a face, an inversion, a reflection of the self. In its endlessness, we see what we normally cannot.

Thus, “wine-dark” is a poetic combination of words that leads to intensive literary analysis. For a less historical example, I’m currently working on my poetry thesis, with pop culture monsters being the central theme of the poems. In one poem, I describe love as being “frankensteined.” By using this monstrous made-up verb in place of “stitched,” the poem’s attitude toward love is much clearer.

Try inventing a word or phrase whose meaning will be as clear to the reader as “wine-dark sea.” Here’s an example:

- What do you want to describe? feeling sorry for yourself because you’ve been stressed out for a long time

- What are some words that this feeling brings up? self-pity, sympathy, sadness, stress, compassion, busyness, love, anxiety, pity party, feeling sorry for yourself

- What are some fun ways to combine these words? sadxiety, stresslove

- Try it in a sentence: As all-nighter wore on, my anxiety softened into sadxiety: still edgy, but soft in the middle.

3. Only Use Words of Certain Etymologies

One of the reasons that the English language is so large and inconsistent is that it borrows words from every language. When you dig back into the history of loanwords, the English language is incredibly interesting!

(For example, many of our legal terms, such as judge, jury, and plaintiff, come from French. When the Normans [old French-speakers from Northern France] conquered England, their language became the language of power and nobility, so we retained many of our legal terms from when the French ruled the British Isles.)

Nerdy linguistics aside, etymologies also make for a fun word choice exercise. Try forcing yourself to write a poem or a story only using words of certain etymologies and avoiding others. For example, if you’re only allowed to use nouns and verbs that we borrowed from the French, then you can’t use Anglo-Saxon nouns like “cow,” “swine,” or “chicken,” but you can use French loanwords like “beef,” “pork,” and “poultry.”

Experiment with word etymologies and see how they affect the mood of your writing. You might find this to be an impactful facet of your word choice. You can Google “__ etymology” for any word to see its origin, and “__ synonym” to see synonyms.

Try writing a sentence only with roots from a single origin. (You can ignore common words like “the,” “a,” “of,” and so on.)

- What do you want to write? The apple rolled off the table.

- Try a first etymology: German: The apple wobbled off the bench.

- Try a second: Latin: The russet fruit rolled off the table.

4. Write in E-Prime

E-Prime Writing describes a writing style where you only write using the active voice. By eschewing all forms of the verb “to be”—using words such as “is,” “am,” “are,” “was,” and other “being” verbs—your writing should feel more clear, active, and precise!

E-Prime not only removes the passive voice (“The bottle was picked up by James”), but it gets at the reality that many sentences using to be are weakly constructed, even if they’re technically in the active voice.

Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

Try writing a paragraph in E-Prime:

- What do you want to write? Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

- Converted to E-Prime: Of course, E-Prime writing won’t best suit every project. The above paragraph uses E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would carry challenges. E-Prime writing endeavors to make all of your subjects active, and your verbs more impactful. While this word choice exercise can bring enjoyment and create memorable language, you probably can’t sustain it over a long writing project.

5. Write Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry, also known as Found Poetry, is a visual creative writing project. You take a page from a published source and create a poem by blacking out other words until your circled words create a new poem. The challenge is that you’re limited to the words on a page, so you need a charged use of both space and language to make a compelling blackout poem.

Blackout poetry bottoms out our list of great word choice exercises because it forces you to consider the elements of word choice. With blackout poems, certain words might be read connotatively rather than denotatively, or you might change the meaning and specificity of a word by using other words nearby. Language is at its most fluid and interpretive in blackout poems!

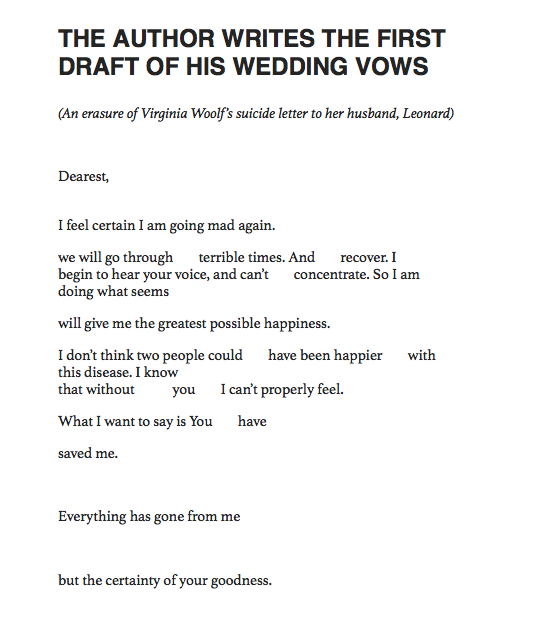

For a great word choice example using blackout poetry, read “The Author Writes the First Draft of His Wedding Vows” by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib. Here it is visually:

Source: https://decreation.tumblr.com/post/620222983530807296/from-the-crown-aint-worth-much-by-hanif

Pick a favorite poem of your own and make something completely new out of it using blackout poetry.

How to Expand Your Vocabulary

Vocabulary is a last topic in word choice. The more words in your arsenal, the better. Great word choice doesn’t rely on a large vocabulary, but knowing more words will always help! So, how do you expand your vocabulary?

The simplest way to expand your vocabulary is by reading.

The simplest answer, and the one you’ll hear the most often, is by reading. The more literature you consume, the more examples you’ll see of great words using the four elements of word choice.

Of course, there are also some great programs for expanding your vocabulary as well. If you’re looking to use words like “lachrymose” in a sentence, take a look at the following vocab builders:

- Dictionary.com’s Word-of-the-Day

- Vocabulary.com Games

- Merriam Webster’s Vocab Quizzes

Improve Your Word Choice With Writers.com’s Online Writing Courses

Looking for more writing exercises? Need more help choosing the right words? The instructors at Writers.com are masters of the craft. Take a look at our upcoming course offerings and join our community!

Sometimes you can tell a person’s opinion on a certain subject, item, idea, or even another individual — not by what they say, but by how they say it. The words a speaker or writer uses to describe and communicate something to others, their word choice or diction, shows their attitude or tone. Although you may not know it, the way you describe something often tells others additional information about what you think.

Many orators, writers, and master communicators have learned to choose their words carefully when communicating an idea to be as effective as possible with their message. Word choice, also known as diction, is important to help communicate the right tone and influence your audience.

Tone and Word Choice Meaning

Tone and word choice, or diction, are specific style choices writers use when composing a piece to convey their message effectively.

The tone is the author’s attitude towards the subject or even a character within a novel.

Word choice, or diction, refers to the author’s specific words, imagery, and figurative language to communicate that tone.

The specific word choices an author employs directly affect and reveal the tone.

To select the right words, authors must pay close attention to both the denotation and connotation of words.

Denotation is the literal dictionary definition of a word.

Connotation is the underlying meaning of a word or the emotional charge it carries. Connotation can be negative, positive, or neutral.

Several words can have the same denotative meaning yet carry a different connotative meaning. The connotation of a word can vary from culture to culture and based on life experiences.

Carefully chosen diction can help writers effectively communicate an idea or perspective and develop a unique voice and style. Word choice enables authentic communication and ensures the tone and message of a piece are aligned or in agreement.Carefully selected diction is crucial when defining the purpose of your writing. It is often appropriate to use detailed descriptions, figurative language, and imagery for narrative, prose, and poetry. However, if you are writing a research paper for biology, your language will be more scientific and the diction more direct and factual.

Tone and mood are often confused. While they are related, they differ in one central aspect. Tone is the author’s attitude toward a subject, idea, situation, or character, while mood is the audience’s or reader’s emotional response. The tone of a piece can be humorous, while the mood is lighthearted and fun. An author may use description to show their dislike toward a character, while the readers may relate to the character and feel empathy.

The Reason for Careful Word Choice

Carefully chosen diction is essential in writing. The types of words an author or orator decides to use depends on the purpose of their writing or speech. Carefully selected words, phrases, and descriptions can do a lot.

Word Choice Matches Your Tone and Purpose

An informative text, such as a non-fiction research article, will have more professional, content-specific, and technical diction because its purpose is to inform a specific audience. A literary fiction piece will have more detailed language, figures of speech, imagery, and conversational language because one of the primary purposes of fiction is to entice a reader, engage with the audience, and entertain.

Word Choice Creates the Right Setting

The language authors use when developing a story to describe characters, time, and place must be in agreement for readers to accept the story as realistic. Authors often use strong descriptive words to help establish the setting, create a mood, and give an authentic feeling to the story.

Word Choice Develops a Narrative Voice

A consistent narrative voice helps readers connect to the piece of writing and establishes a trustworthy relationship between reader and narrator.

Word Choice Creates Better Characters

Authors and orators often use language specific to a particular region, dialect, and accents to provide a realistic portrayal of a character or relate to the audience. Presenters who are not from Texas may use typical Texas colloquialisms, such as «y’all,» which is a combination of the words «you» and «all,» to relate to the listeners. A young character in a fiction piece may speak with a lot of slang or foul language to show immaturity. A character’s use of specific diction can indicate their gender, level of education, occupation, upbringing, or even social class.

A colloquialism is an informal word or phrase often used in daily conversation. Some colloquialisms may be specific to a region, culture, or religion.

Tone and Word Choice Examples

Some descriptive words have the same denotative meaning but carry different connotations. Using careful word choice, especially when selecting the proper synonym or a descriptive adjective, can create the desired effect and convey the appropriate tone for a piece. Consider the following table of examples.

| Word (with neutral connotation) | Denotation | Synonym with a positive connotation | Synonym with a negative connotation |

| Thin | having little flesh or fat | Slender | Skinny |

| Overweight | above a weight considered normal or desirable | Thick | Fat |

| Strict | demanding that rules are followed or obeyed | Firm | Austere |

Have you noticed a difference in someone’s tone when they call someone slender vs when they call someone skinny?

Impact of Word Choice on Meaning and Tone

Selecting words with a positive connotation will reflect a more amiable tone toward the subject, while words with a negative connotation will convey a negative attitude toward a subject. Words with a neutral connotation are best used when an author does not want to reveal their attitude or, in instances, such as a scientific paper, where only the facts are important.

Difference Between Tone and Word Choice

Word choice and tone are related. Word choice refers to the language specifically chosen by the author or orator to help convey their attitude regarding a notion, story, or setting. Word choice shapes the tone. On the other hand, the desired tone an author seeks dictates the words they use. If the author wants to establish a worried tone, some key diction and phrases within the piece might be words like «tentatively,» «shaking,» «stressed,» «nervous,» «sweaty,» «eyes darting,» and «looking over his shoulder.» To portray a more optimistic tone, an author might select words like «eagerly,» «excitedly,» «hopeful,» «reassuring,» and «anticipated.» Keyword choice is the foundation that builds a consistent tone.

The Four Components of Tone

Whether an article is a non-fiction piece, a fictive story, a poem, or an informative article, the tone the writer uses helps audience members have the appropriate reaction to the information by creating the mood. There are four basic components of tone, and diction dictates the balance of emotions. Authors aim to maintain the same tone throughout a piece to convey a consistent message. The four components of tone range from:

- Funny to serious

- Casual to formal

- Irreverent to respectful

- Enthusiastic to matter-of-fact (direct)

Writers choose the voice they want to deliver and then focus on specific word choices to maintain their tone. Pieces that move too often between distinct tones can be hard for readers to follow and cause confusion.

Types of Tones

The tone in writing indicates a particular attitude. Here are some types of tones with examples from the literature and speeches.

The diction that helps to convey the tone is highlighted.

When I pulled the trigger I did not hear the bang or feel the kick—one never does when a shot goes home—but I heard the devilish roar of glee that went up from the crowd. In that instant, in too short a time, one would have thought, even for the bullet to get there, a mysterious, terrible change had come over the elephant. He neither stirred nor fell, but every line of his body had altered. He looked suddenly stricken, shrunken, immensely old, as though the frightful impact of the bullet had paralyzed him without knocking him down.1

In this excerpt from Orwell’s essay, «Shooting an Elephant,» the gruesome tone is communicated through Orwell’s descriptive word choice. The words «terrible,» «suddenly stricken,» and «paralyzed» describe the horrific reaction the elephant has when the first bullet hits.

Inside the house lived a malevolent phantom. People said he existed, but Jem and I had never seen him. People said he went out at night when the moon was down, and peeped in windows. When people’s azaleas froze in a cold snap, it was because he had breathed on them. Any stealthy small crimes committed in Maycomb were his work. Once the town was terrorized by a series of morbid nocturnal events: people’s chickens and household pets were found mutilated; although the culprit was Crazy Addie, who eventually drowned himself in Barker’s Eddy, people still looked at the Radley Place, unwilling to discard their initial suspicions.2

In this excerpt from Chapter 1 of To Kill a Mockingbird, descriptive words help to create a foreboding tone. Words like «morbid,» «mutilated,» «terrorized,» and «malevolent phantom» reveal Scout’s sense of fear and apprehension.

Hope» is the thing with feathers —

That perches in the soul —

And sings the tune without the words —

And never stops — at all —

And sweetest — in the Gale — is heard —

And sore must be the storm —

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm —

I’ve heard it in the chillest land —

And on the strangest Sea —

Yet — never — in Extremity,

It asked a crumb — of me.3

In this poem by Emily Dickinson, the cheerful tone is communicated through the words «perches,» «sings,» and «sweetest.»

Tone and Word Choice — Key Takeaways

- Word choice refers to the specific language, words, phrases, descriptions, and figures of speech authors choose to create a desired effect.

- Tone is the author’s attitude toward a subject as conveyed by their word choice in a given piece.

- Denotation is the dictionary definition of a word and connotation is the underlying meaning of a word and its emotional charge.

- Connotation is the underlying meaning of a word or the emotional charge it carries. Connotation can be negative, positive, or neutral.

- The four components of tone are, funny to serious, casual to formal, irreverent to respectful, and enthusiastic to matter-of-fact.

1 George Orwell. «Shooting an Elephant.» 1936.

2 Lee Harper. To Kill a Mockingbird. 1960.

3 Emily Dickinson. ‘»Hope» is the thing with feathers.’ 1891.

For every author, making informed word choices while writing a paper is paramount to their success. While writing a manuscript, you frequently and meticulously select words that let you express your ideas with utmost clarity. Subsequently, you determine a befitting way to regroup those words into phrases, sentences, and at times, paragraphs. Therefore, it is always prudent to be aware of and eschew from errors in word usage that could affect the clarity of your manuscript.

Here are a few of the most frequent mistakes when it comes to word choice:

Incorrectly used words

Original version: Everyone complemented Chloé Baker for winning the Nobel Peace Prize.

Revised version: Everyone complimented Chloé Baker for winning the Nobel Peace Prize.

Reason for revision: “Complement” means something that completes or adds further features to something else, whereas “Compliment” means to praise someone.

Words with undesirable implications or meanings

Original version: I sprayed the caterpillars in their personal zones.

Revised version: I sprayed the caterpillars in their hiding zones.

Reason for revision: The original version has a word (personal) that can be interpreted in two ways. The revised version communicates the intended meaning with clarity.

Complicated words in place of a simpler/shorter term

Original version: No one was convinced that her story wasn’t apocryphal.

Revised version: No one was convinced that her story wasn’t untrue.

Reason for revision: The original version has a complicated word (apocryphal); the revised version replaces it with a simpler and shorter word—untrue.

Awkward words

Original version: High school athletes’ inclination towards sports science in the 21st century is in total contrast with the attitude shared by the previous generation.

Revised version: The inclination towards sports science among the high school athletes in the 21st century is in total contrast with the attitude shared by the previous generation.

Reason for revision: The italicized phrase in the original version is difficult to read, and a little unclear, whereas the revised version is easily comprehensible.

Similar meaning words used in the wrong context

Original version: As the number of cholera patients skyrocketed during the winter, the doctors worked overtime to hastily treat as many patients as possible to avoid any patients missing out on treatment.

Revised version: As the number of cholera patients skyrocketed during the winter, the doctors worked overtime to promptly treat as many patients as possible to avoid any patients missing out on treatment.

Reason for revision: “Hastily” is similar to “promptly,” but in the context of medical care for a serious disease, the word “hastily” is inappropriate as it can easily mean “speed with recklessness.”

Words that communicate nuances of meaning

Original version: A conversation between the presidents of both countries is necessary to avoid further escalation of the precarious political situation.

Revised version: A discourse between the Presidents of both countries is necessary to avoid further escalation of the precarious political situation.

Reason for revision: The word “conversation” isn’t suitable considering the seriousness of the matter. “Discourse” is more suitable, given the gravity and formal nature of the situation.

Furthermore, it is best to figure out the most effective way to convey your message succinctly in academic writing. Here are a few notable examples:

|

Longer phrase |

The concise word |

| Shown beyond doubt | Proven |

| From my standpoint | Personally |

| In the course of | During |

| On the assumption that | If |

| After a period of time | Afterward |

| At the same time | Though |

| For the reason that | Because |

| On all occasions | Always |

| A number of | Several |

| Throughout the world | Worldwide |

| In the ancient past | Historically |

| At that point in time | Then |

| Leading up to | Before |

| All Things Considered | Considering |

These are a few tips to make sure you always select the correct words when writing an academic paper and avoid the mistakes enlisted in the article:

-

- Always check the meaning of unfamiliar words before using them in your manuscript, for instance, nonplussed, admonish, arcane, esoteric, expunge, phlegmatic, platitude, quixotic.

- Avoid using fancy words to impress the reader/reviewer with your extensive vocabulary. It’s a strategy that can backfire, and it also makes the reading experience unnecessarily difficult. For instance, use “optimistic” instead of “sanguine”; use “breeze” instead of “zephyr.”

- Make sure you use accurate phrasing. For instance, instead of “the pasty doctor,” use “the pale obstetrician.”

- Whenever possible, avoid repetition. For instance, instead of “new innovations,” use “innovations”; instead of “revert back,” simply write “revert.”

And if you are looking for a proven tool to enhance your writing dynamically, then try out Trinka, the world’s first language enhancement tool that is custom-built for academic and technical writing. It has several exclusive features to make your manuscript ready for the global audience.

Presentation on theme: «An author’s word choice.»— Presentation transcript:

1

An author’s word choice.

DICTION An author’s word choice. HOW an author says something is a big part of what he has to say. It varies depending on the message, the occasion, and the audience. It influences the TONE of the message.

2

The DICTIONARY meaning of a word; the exact meaning.

DENOTATION The DICTIONARY meaning of a word; the exact meaning.

3

CONNOTATION The associations called up by a word that goes beyond its dictionary meaning; the psychological, emotional, social, or cultural connections made to words

4

TONE The speaker or author’s attitude toward the subject. The general character or attitude of a place, piece of writing, situation, etc.

Definition of Diction

As a literary device, diction refers to the choice of words and style of expression that an author makes and uses in a work of literature. Diction can have a great effect on the tone of a piece of literature, and how readers perceive the characters.

One of the primary things that diction does is establish whether a work is formal or informal. Choosing more elevated words will establish a formality to the piece of literature, while choosing slang will make it informal. For example, consider the difference between “I am much obliged to you, sir” and “Thanks a bunch, buddy!” The former expression of gratitude sounds much more formal than the latter, and both would sound out of place if used in the wrong situation.

Common Examples of Diction

We alter our diction all the time depending on the situation we are in. Different communication styles are necessary at different times. We would not address a stranger in the same way as a good friend, and we would not address a boss in that same way as a child. These different choices are all examples of diction. Some languages have codified diction to a greater extent. For example, Spanish is one of many languages that has a different form of address and verb conjugation if you are speaking to a stranger or superior than if you are speaking to a friend or younger person. Here are more examples of different diction choices based on formality:

- “Could you be so kind as to pass me the milk?” Vs. “Give me that!”

- “I regret to inform you that that is not the case.” Vs. “You’re wrong!”

- “It is a pleasure to see you again! How are you today?” Vs. “Hey, what’s up?”

- “I’m a bit upset,” Vs. “I’m so pissed off.”

- “I would be delighted!” Vs. “Sure, why not?”

- “I’ll do it right away, sir,” Vs. “Yeah, just a sec.”

Significance of Diction in Literature

Authors make conscious and unconscious word choices all the time when writing literature, just as we do when speaking to one another. The diction in a piece establishes many different aspects of how we read the work of literature, from its formality to its tone even to the type of story we are reading. For example, there could be two practically identical spy novels, but in one we are privileged to the main character’s innermost thoughts about the situation while in the other we only see what the main character does. The author has chosen verbs either of introspection or action, and this type of diction thus determines what kind of story the book presents. This is the difference between spy novels by, for example, John le Carré (Tinker, Tailor, Solider, Spy; A Most Wanted Man) and Dan Brown (The Da Vinci Code; Inferno).

Examples of Diction in Literature

Example #1

MACBETH: Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee.

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? Or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressèd brain?

Vs.

MACBETH: I have done the deed. – Didst thou not hear a noise?

LADY MACBETH: I heard the owl scream and the crickets cry.

Did not you speak?

MACBETH: When?

LADY MACBETH: Now.

MACBETH: As I descended?

LADY MACBETH: Ay.

(Macbeth by William Shakespeare)

This is an interesting example of diction from Shakespeare’s famous tragedy Macbeth. As modern readers, we often consider Shakespeare’s language to be quite formal, as it is filled with words like “thou” and “thy” as well as archaic syntax such as in Macbeth’s questions “Didst thou not hear a noise?” However, there is striking difference in the diction between these two passages. In the first, Macbeth is contemplating a murder in long, expressive sentences. In the second excerpt, Macbeth has just committed a murder and has a rapid-fire exchange with his wife, Lady Macbeth. The different word choices that Shakespeare makes shows the different mental states that Macbeth is in in these two nearby scenes.

Example #2

It seemed to me that a careful examination of the room and the lawn might possibly reveal some traces of this mysterious individual. You know my methods, Watson. There was not one of them which I did not apply to the inquiry. And it ended by my discovering traces, but very different ones from those which I had expected.

(The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle)

This diction example is quite formal, even though Sherlock Holmes is speaking to his close friend Dr. Watson. He speaks in very full sentences and with elevated language (“might possibly reveal some traces” and “not one of them which I did not apply to the inquiry”). When speaking to such a close acquaintance, most people would choose other constructions and less formal language. However, this diction employed by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle shows that Sherlock Holmes is always a very formal character, no matter the situation.

Example #3

You just hold your head high and keep those fists down. No matter what anybody says to you, don’t you let ’em get your goat. Try fighting with your head for a change.

(To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee)

This is a quote from Atticus Finch, the father of To Kill a Mockingbird’s narrator, Scout. Atticus uses very formal language in his profession, as he is a celebrated lawyer. When speaking to his daughter, though, he changes his diction and uses short, simple phrases and words. He also uses the clichés “hold your head high” and “don’t you let ‘em get your goat.” This informal diction shows his close relationship to his daughter and makes him seem more approachable than if we only saw him in his lawyerly role.

Example #4

His adolescent nerdliness vaporizing any iota of a chance he had for young love. Everybody else going through the terror and joy of their first crushes, their first dates, their first kisses while Oscar sat in the back of the class, behind his DM’s screen, and watched his adolescence stream by. Sucks to be left out of adolescence, sort of like getting locked in the closet on Venus when the sun appears for the first time in a hundred years.

(The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Díaz)

Contemporary writer Junot Díaz is noted for using a very distinct diction in his books. He often sprinkles in Spanish words and phrases in his works to make his characters—many of whom are from the Dominican Republic—seem more authentic. In this excerpt from his novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Díaz uses very informal language, even creating the word “nerdliness.” He uses the slang term “sucks” to reinforce the sense of his character Oscar’s youth.

Test Your Knowledge of Diction

1. What is the correct diction definition as a literary device?

A. The choice of words an author makes in writing a piece of literature.

B. The enunciation that a speaker uses.

C. The way the reader feels when reading a work of literature.

| Answer to Question #1 | Show |

|---|---|

2. Which of the following famous lines from Shakespeare’s Hamlet employs informal diction?

A. POLONIUS: Neither a borrower nor a lender be; For loan oft loses both itself and friend, and borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.

B. HAMLET: Get thee to a nunnery, go.

C. QUEEN GERTRUDE: The lady doth protest too much, methinks.

| Answer to Question #2 | Show |

|---|---|

Consider the following excerpt from Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

He told them that it was only because of her love that he’d been able to do the thing that he had done, the thing they could no longer stop, told them if they killed him they would probably feel nothing and their children would probably feel nothing either, not until they were old and weak or about to be struck by a car and then they would sense him waiting for them on the other side and over there he wouldn’t be no fatboy or dork or kid no girl had ever loved; over there he’d be a hero, an avenger.

Which of the following phrases show that this is an example of informal diction?

A. He told them that it was only because of her love…

B. …if they killed him they would probably feel nothing…

C. He wouldn’t be no fatboy or dork…

| Answer to Question #3 | Show |

|---|---|

Read each sentence from Dr. King’s «I Have a Dream» speech. Mark the elements that are parallel. Then, note what type of parallel structure is being used-words, phrases, or clauses.

a. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.

b. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.

c. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.