Word choice means the judicious of words considering various factors, including meaning, specificity, level, tone, and general audience. The insightful selection of words can make a mediocre writer a better one or transform a dull subject into engaging. The selection of words is paramount for composition, especially content writing. Picking exact words will enable you to expand the effect on your readers.

Image credited to Pixalbay.Com

” Proper Words in Proper Places make the true definition of style.” -Jonathan Swift

A sentence should I not only be faultless in its idiom and grammar but must at the same time express the meaning intended clearly and exactly. We might as well make a few general observations on the right selection of words.

The literary composition is admittedly a fine art and efficiency in this art as in any other, depends upon a knowledge of the rules and principles peculiar to it followed assiduously in practice as also an imitation of a good model. In other words, good reading, knowledge of grammar, idioms and vocabulary, and constant and careful exercise in writing are essential. For the written article is three-fold art comprising

- clear, consistent and orderly thinking

- the right expression; and

- Correct orthography

In the first place, the writer must be clear and definite as to what he has to say and arrange his thoughts logically and methodically before he begins to write. Secondly, the language used must be adequate and correct. It must be a faithful rendering of his thoughts and faultless from the point of view of grammar and usage. Thirdly the writing must be free from errors of spelling, punctuation etc., and should be uniform and legible.

A right selection of words is thus an integral part of the composition from the standpoint of both the writer and the reader. It is the duty of the former to make himself clearly, accurately and easily intelligible. To this end, he must find the words that exactly and completely express his thought or feeling. On the other hand, the reader is not always anxious to inquire whether the writing is an adequate or faithful expression of what falls in the writer’s mind. All that he expects and cares about is that “what is placed before him to read is in itself complete, appropriate and clear. These are the minimum qualities which will include him to read any piece of composition. The liberties of the writer are, therefore, restricted to this extent- must be clear and he must be interesting”(Classen).

1. Prefer simple and familiar words or phrase to difficult or uncommon one, provided the sense is practically the same:

The Choice of words

- very important, NOT critical

- to show great zeal NOT evince or exhibit great enthusiasm

- sent a carriage NOT conveyance

- but NOT be it that it may be

- shut the door NOT closed

- am free in the morning, not forenoon

- he was set for NOT summoned

- a brave soldier NOT valiant

- I have nothing to say NOT remark or mention

- buy the book NOT purchase

- he wants some medicine NOT physic

- don’t hide NOT conceal

- finish this page NOT complete

- our test begins on 10th NOT commences

- his pay is very low NOT his emoluments

- he suffered a heavy loss

- If NOT on the off chance

- also NOT additionally

- the fire was put out NOT the conflagration was extinguished

- it was a positive lie NOT veritable

- we had lunch at two NOT luncheon

- there was no room for me NOT accommodation

- a sad event NOT happening

- the results will be given out NOT announced

- the trouble was made worse NOT aggravated

- what has brought about this state of affairs? NOT what is the raison d’etre of

2. Avoid Roundabout Ways of Expression. Be brief and direct:

- I got or received prize NOT was the recipient of

- The doctor was sent for or called NOT the services of a physician were called into requisition.

- He is senior in service NOT as far as his service is concerned

- Since he is senior NOT in view of the fact that he is senior etc.

- There is no news NOT not a complete dearth of

- This is false NOT not in my favour

- Kindly grant me leave NOT leave in my favour

- Kindly note his arrival NOT note the time when he arrived

- My brother, the doctor NOT my brother who is a doctor

- I want to know who left early NOT I want to be told the names of all those that left the place before the time was over

- Arif and Ali like each other NOT Arif like Ali and Ali like Arif.

3. Be Sure of The Exact Meaning Of Word

- You must be sure about the exact meaning of a word or phrase before you use it.

- He advised ( not persuaded) me to stay but I left.

- I worked hard (not tried) but failed in the test.

- I like this cool breeze(not cold) after the heat of the day.

- I never expected( not hoped) that he would fail.

- His look frightened me( not horrified).

- You have no reason to suspect him(no doubt).

4.Conformity To The Required Meaning

When there are two or more words having apparently the same signification, make sure which of them conforms to the idiom or give the required meaning:

- His position has improved so much, etc.(not well).

- I must impress this fact on your mind (not emphasis).

- The situation is too bad for us to ignore( not bad enough, etc.).

- All the requests have been collected( assembled).

- The man said, “It is a great hour you have done me, etc.”( not spoke or told).

- You talk like a fool(not say).

- He turned his eyes in another direction( not glance).

- The proposal is worthy of being seriously considered( not worth).

- It is not worth the trouble( not worthy of trouble).

- Try to look cheerful( not happy).

- He was moved to pity at the site( not sympathy).

- Who started the trouble( not began).

- The removal of these grievances will relieve the situation (not pacify; but will pacify the strikers).

- He refused to see you and denied having seen you already.

5. Use Short Words or Phrases

- Other things being equal, a short word, phrase, or a sentence is generally better than a long one:

- He came late and left early( not he arrived late and departed early)

- They are often to blame( not frequently).

- I want your help( not assistance).

- It is absurd to think so( not preposterous to have such an opinion).

- The greater part of our students are weak in English( not proportion).

- This is an interesting story( not intriguing).

6. Avoid Use of Slang, Colloquial, Redundant, and Archaic Words

In serious composition avoid words or phrases that are merely colloquial, slang, archaic or restricted to poetry:

He will be here before long( not here); the closing of our college( not closure); a wonderful tale( not wondrous); all books except one(not save); do you know anything( not aught) about it? It is true(not be); to that he did not reply(not there too); throw it away (not cast); I should like to go( not love); he knew very little about it( not precious).

7. Good Readability

Finally, a sentence should read well; that is, it should be balanced and rhythmical. As far as possible, avoid repetition of words or sounds( jingles), and let not a sentence rise gradually and fall abruptly or end with a weak and empty word. Here are some examples to understand this.

- I saw him after I had seen everybody else( not after…else I saw him).BUT After everybody else, I saw him in the evening.

- The staff is not sufficient, or if it is sufficient, it is not efficient( not rather than – the staff is not sufficient, or if it is sufficient, it is not sufficiently efficient).

- He lived practically alone( not practically exclusively, etc.).

- This may have been due to excessive power placed in the hands( not due to undue power).

Ask Your Question?

Check Your Progress

What does the choice of words mean?

What is word choice in writing?

How do I fix word choice?

How do you write good words?

All strong writers have something in common: they understand the value of word choice in writing. Strong word choice uses vocabulary and language to maximum effect, creating clear moods and images and making your stories and poems more powerful and vivid.

The meaning of “word choice” may seem self-explanatory, but to truly transform your style and writing, we need to dissect the elements of choosing the right word. This article will explore what word choice is, and offer some examples of effective word choice, before giving you 5 word choice exercises to try for yourself.

Word Choice Definition: The Four Elements of Word Choice

The definition of word choice extends far beyond the simplicity of “choosing the right words.” Choosing the right word takes into consideration many different factors, and finding the word that packs the most punch requires both a great vocabulary and a great understanding of the nuances in English.

Choosing the right word involves the following four considerations, with word choice examples.

1. Meaning

Words can be chosen for one of two meanings: the denotative meaning or the connotative meaning. Denotation refers to the word’s basic, literal dictionary definition and usage. By contrast, connotation refers to how the word is being used in its given context: which of that word’s many uses, associations, and connections are being employed.

A word’s denotative meaning is its literal dictionary definition, while its connotative meaning is the web of uses and associations it carries in context.

We play with denotations and connotations all the time in colloquial English. As a simple example, when someone says “greaaaaaat” sarcastically, we know that what they’re referring to isn’t “great” at all. In context, the word “great” connotes its opposite: something so bad that calling it “great” is intentionally ridiculous. When we use words connotatively, we’re letting context drive the meaning of the sentence.

The rich web of connotations in language are crucial to all writing, and perhaps especially so to poetry, as in the following lines from Derek Walcott’s Nobel-prize-winning epic poem Omeros:

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez,

the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane

down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain

marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

Sugar cane isn’t, literally, made of “feathered lances,” which would literally denote “long metal spears adorned with bird feathers”; but feathered connotes “branching out,” the way sugar cane does, and lances connotes something tall, straight, and pointy, as sugar cane is. Together, those two words create a powerfully true visual image of sugar cane—in addition to establishing the martial language (“spears,” “marching”) used elsewhere in the passage.

Whether in poetry or prose, strong word choice can unlock images, emotions, and more in the reader, and the associations and connotations that words bring with them play a crucial role in this.

2. Specificity

Use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description.

In the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms. That’s why it’s important to use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description. Words like “good,” “average,” and “awful” are far less descriptive and specific than words like “liberating” (not just good but good and freeing), “C student” (not just average but academically average), and “despicable” (not just awful but morally awful). These latter words pack more meaning than their blander counterparts.

Since more precise words give the reader added context, specificity also opens the door for more poetic opportunities. Take the short poem “[You Fit Into Me]” by Margaret Atwood.

You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

A fish hook

An open eye

The first stanza feels almost romantic until we read the second stanza. By clarifying her language, Atwood creates a simple yet highly emotive duality.

This is also why writers like Stephen King advocate against the use of adverbs (adjectives that modify verbs or other adjectives, like “very”). If your language is precise, you don’t need adverbs to modify the verbs or adjectives, as those words are already doing enough work. Consider the following comparison:

Weak description with adverbs: He cooks quite badly; the food is almost always extremely overdone.

Strong description, no adverbs: He incinerates food.

Of course, non-specific words are sometimes the best word, too! These words are often colloquially used, so they’re great for writing description, writing through a first-person narrative, or for transitional passages of prose.

3. Audience

Good word choice takes the reader into consideration. You probably wouldn’t use words like “lugubrious” or “luculent” in a young adult novel, nor would you use words like “silly” or “wonky” in a legal document.

This is another way of saying that word choice conveys not only direct meaning, but also a web of associations and feelings that contribute to building the reader’s world. What world does the word “wonky” help build for your reader, and what world does the word “seditious” help build? Depending on the overall environment you’re working to create for the reader, either word could be perfect—or way out of place.

4. Style

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing. Every writer uses words differently, and as those words come to form poems, stories, and books, your unique grasp on the English language will be recognizable by all your readers.

Style isn’t something you can point to, but rather a way of describing how a writer writes. Ernest Hemingway, for example, is known for his terse, no-nonsense, to-the-point styles of description. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, is known for writing that’s poetic, intense, and melodramatic, and James Joyce for his lofty, superfluous writing style.

Here’s a paragraph from Joyce:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.

And here’s one from Hemingway:

Bill had gone into the bar. He was standing talking with Brett, who was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed. She had no stockings on.

Style is best observed and developed through a portfolio of writing. As you write more and form an identity as a writer, the bits of style in your writing will form constellations.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Word Choice in Writing: The Importance of Verbs

Before we offer some word choice exercises to expand your writing horizons, we first want to mention the importance of verbs. Verbs, as you may recall, are the “action” of the sentence—they describe what the subject of the sentence actually does. Unless you are intentionally breaking grammar rules, all sentences must have a verb, otherwise they don’t communicate much to the reader.

Because verbs are the most important part of the sentence, they are something you must focus on when expanding the reaches of your word choice. Verbs are the most widely variegated units of language; the more “things” you can do in the world, the more verbs there are to describe them, making them great vehicles for both figurative language and vivid description.

Consider the following three sentences:

- The road runs through the hills.

- The road curves through the hills.

- The road meanders through the hills.

Which sentence is the most descriptive? Though each of them has the same subject, object, and number of words, the third sentence creates the clearest image. The reader can visualize a road curving left and right through a hilly terrain, whereas the first two sentences require more thought to see clearly.

Finally, this resource on verb usage does a great job at highlighting how to invent and expand your verb choice.

Word Choice in Writing: Economy and Concision

Strong word choice means that every word you write packs a punch. As we’ve seen with adverbs above, you may find that your writing becomes more concise and economical—delivering more impact per word. Above all, you may find that you omit needless words.

Omit needless words is, in fact, a general order issued by Strunk and White in their classic Elements of Style. As they explain it:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

It’s worth repeating that this doesn’t mean your writing becomes clipped or terse, but simply that “every word tell.” As our word choice improves—as we omit needless words and express ourselves more precisely—our writing becomes richer, whether we write in long or short sentences.

As an example, here’s the opening sentence of a random personal essay from a high school test preparation handbook:

The world is filled with a numerous amount of student athletes that could somewhere down the road have a bright future.

Most words in this sentence are needless. It could be edited down to:

Many student athletes could have a bright future.

Now let’s take some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Can you remove a single word without sacrificing an enormous richness of meaning?

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In strong writing, every single word is chosen for maximum impact. This is the true meaning of concise or economical writing.

5 Word Choice Exercises to Sharpen Your Writing

With our word choice definition in mind, as well as our discussions of verb use and concision, let’s explore the following exercises to put theory into practice. As you play around with words in the following word choice exercises, be sure to consider meaning, specificity, style, and (if applicable) audience.

1. Build Moods With Word Choice

Writers fine-tune their words because the right vocabulary will build lush, emotive worlds. As you expand your word choice and consider the weight of each word, focus on targeting precise emotions in your descriptions and figurative language.

This kind of point is best illustrated through word choice examples. An example of magnificent language is the poem “In Defense of Small Towns” by Oliver de la Paz. The poem’s ambivalent feelings toward small hometowns presents itself through the mood of the writing.

The poem is filled with tense descriptions, like “animal deaths and toughened hay” and “breeches speared with oil and diesel,” which present the small town as stoic and masculine. This, reinforced by the terse stanzas and the rare “chances for forgiveness,” offers us a bleak view of the town; yet it’s still a town where everything is important, from “the outline of every leaf” to the weightless flight of cattail seeds.

The writing’s terse, heavy mood exists because of the poem’s juxtaposition of masculine and feminine words. The challenge of building a mood produces this poem’s gravity and sincerity.

Try to write a poem, or even a sentence, that evokes a particular mood through words that bring that word to mind. Here’s an example:

- What mood do you want to evoke? flighty

- What words feel like they evoke that mood? not sure, whatever, maybe, perhaps, tomorrow, sometimes, sigh

- Try it in a sentence: “Maybe tomorrow we could see about looking at the lab results.” She sighed. “Perhaps.”

2. Invent New Words and Terms

A common question writers ask is, What is one way to revise for word choice? One trick to try is to make up new language in your revisions.

If you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

In the same way that unusual verbs highlight the action and style of your story, inventing words that don’t exist can also create powerful diction. Of course, your writing shouldn’t overflow with made-up words and pretentious portmanteaus, but if you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

A great example of an invented word is the phrase “wine-dark sea.” Understanding this invention requires a bit of history; in short, Homer describes the sea as “οἶνοψ πόντος”, or “wine-faced.” “Wine-dark,” then, is a poetic translation, a kind of kenning for the sea’s mystery.

Why “wine-dark” specifically? Perhaps because, like the sea, wine changes us; maybe the eyes of the sea are dark, as eyes often darken with wine; perhaps the sea is like a face, an inversion, a reflection of the self. In its endlessness, we see what we normally cannot.

Thus, “wine-dark” is a poetic combination of words that leads to intensive literary analysis. For a less historical example, I’m currently working on my poetry thesis, with pop culture monsters being the central theme of the poems. In one poem, I describe love as being “frankensteined.” By using this monstrous made-up verb in place of “stitched,” the poem’s attitude toward love is much clearer.

Try inventing a word or phrase whose meaning will be as clear to the reader as “wine-dark sea.” Here’s an example:

- What do you want to describe? feeling sorry for yourself because you’ve been stressed out for a long time

- What are some words that this feeling brings up? self-pity, sympathy, sadness, stress, compassion, busyness, love, anxiety, pity party, feeling sorry for yourself

- What are some fun ways to combine these words? sadxiety, stresslove

- Try it in a sentence: As all-nighter wore on, my anxiety softened into sadxiety: still edgy, but soft in the middle.

3. Only Use Words of Certain Etymologies

One of the reasons that the English language is so large and inconsistent is that it borrows words from every language. When you dig back into the history of loanwords, the English language is incredibly interesting!

(For example, many of our legal terms, such as judge, jury, and plaintiff, come from French. When the Normans [old French-speakers from Northern France] conquered England, their language became the language of power and nobility, so we retained many of our legal terms from when the French ruled the British Isles.)

Nerdy linguistics aside, etymologies also make for a fun word choice exercise. Try forcing yourself to write a poem or a story only using words of certain etymologies and avoiding others. For example, if you’re only allowed to use nouns and verbs that we borrowed from the French, then you can’t use Anglo-Saxon nouns like “cow,” “swine,” or “chicken,” but you can use French loanwords like “beef,” “pork,” and “poultry.”

Experiment with word etymologies and see how they affect the mood of your writing. You might find this to be an impactful facet of your word choice. You can Google “__ etymology” for any word to see its origin, and “__ synonym” to see synonyms.

Try writing a sentence only with roots from a single origin. (You can ignore common words like “the,” “a,” “of,” and so on.)

- What do you want to write? The apple rolled off the table.

- Try a first etymology: German: The apple wobbled off the bench.

- Try a second: Latin: The russet fruit rolled off the table.

4. Write in E-Prime

E-Prime Writing describes a writing style where you only write using the active voice. By eschewing all forms of the verb “to be”—using words such as “is,” “am,” “are,” “was,” and other “being” verbs—your writing should feel more clear, active, and precise!

E-Prime not only removes the passive voice (“The bottle was picked up by James”), but it gets at the reality that many sentences using to be are weakly constructed, even if they’re technically in the active voice.

Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

Try writing a paragraph in E-Prime:

- What do you want to write? Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

- Converted to E-Prime: Of course, E-Prime writing won’t best suit every project. The above paragraph uses E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would carry challenges. E-Prime writing endeavors to make all of your subjects active, and your verbs more impactful. While this word choice exercise can bring enjoyment and create memorable language, you probably can’t sustain it over a long writing project.

5. Write Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry, also known as Found Poetry, is a visual creative writing project. You take a page from a published source and create a poem by blacking out other words until your circled words create a new poem. The challenge is that you’re limited to the words on a page, so you need a charged use of both space and language to make a compelling blackout poem.

Blackout poetry bottoms out our list of great word choice exercises because it forces you to consider the elements of word choice. With blackout poems, certain words might be read connotatively rather than denotatively, or you might change the meaning and specificity of a word by using other words nearby. Language is at its most fluid and interpretive in blackout poems!

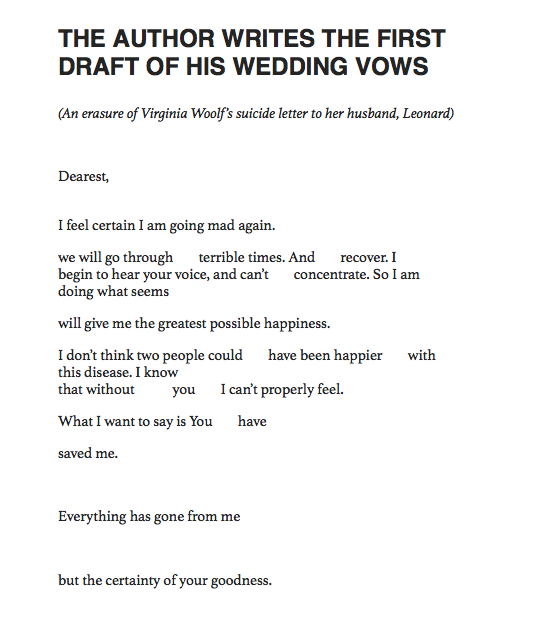

For a great word choice example using blackout poetry, read “The Author Writes the First Draft of His Wedding Vows” by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib. Here it is visually:

Source: https://decreation.tumblr.com/post/620222983530807296/from-the-crown-aint-worth-much-by-hanif

Pick a favorite poem of your own and make something completely new out of it using blackout poetry.

How to Expand Your Vocabulary

Vocabulary is a last topic in word choice. The more words in your arsenal, the better. Great word choice doesn’t rely on a large vocabulary, but knowing more words will always help! So, how do you expand your vocabulary?

The simplest way to expand your vocabulary is by reading.

The simplest answer, and the one you’ll hear the most often, is by reading. The more literature you consume, the more examples you’ll see of great words using the four elements of word choice.

Of course, there are also some great programs for expanding your vocabulary as well. If you’re looking to use words like “lachrymose” in a sentence, take a look at the following vocab builders:

- Dictionary.com’s Word-of-the-Day

- Vocabulary.com Games

- Merriam Webster’s Vocab Quizzes

Improve Your Word Choice With Writers.com’s Online Writing Courses

Looking for more writing exercises? Need more help choosing the right words? The instructors at Writers.com are masters of the craft. Take a look at our upcoming course offerings and join our community!

Word usage errors in research papers written by non-native speakers of English are more common than other mistakes and are only topped by errors in style. Since the main purpose of academic writing is to clearly convey information, knowing how to use words correctly and effectively is absolutely crucial.

Some problems with word choice stem from the fact that the English language contains pairs or sets of words that sound alike (homophones) and/or look alike (homonyms) but have different meanings. Additionally, there are words that sound and look different but have similar meanings. Other mistakes occur when ESL authors think in their mother language while writing and try to translate entire expressions into English. And sometimes, the wrong word is actually the right word spelled incorrectly. Here, we list examples of typical errors in word usage that we frequently come across in academic texts written by ESL authors and provide tips on how to avoid them.

Table of Contents:

- Words with Similar Sounds but Different Meanings

- Words with Similar Meanings but Different Connotations

- Using the Correct Word Stem with the Wrong Prefix or Suffix

- Translation Errors and Collocations

- Spelling Mistakes That Can Change Your Meaning

Words with Similar Sounds but Different Meanings

Confusing similar words that have different meanings is one of the most common errors in word choice, and one that happens to native speakers as well. In spoken English, many of these might not be very obvious or just sound like a slip of the tongue. However, when writing any kind of academic text, you should check for such mistakes to make sure the reader clearly understands what you are trying to convey.

1. Affect vs effect / affective versus effective

Affect as a noun describes the strong experience of feelings or emotions, while the verb to affect means to impact. The noun effect, in contrast, is the result of something, and the verb to effect means to cause something to happen or to bring about a certain result. In brief, if something affects something else, it leads to a certain effect.

NO Sleep deprivation clearly effected the patients’ overall well-being.

YES Sleep deprivation clearly affected the patients’ overall well-being.

NO The affect of exercise on depression is not clearly understood.

YES The effect of exercise on depression is not clearly understood.

2. Then vs than

Than is a conjunction/preposition that is used for comparison, while then is an adverb that means at that time or subsequently.

YES The effect of exercise on depression is less obvious than that of medication.

YES Patients were debriefed, and then asked to fill in a questionnaire.

NO The effect of exercise on depression is less obvious then that of medication

3. Principal vs principle

Principal as an adjective means the main or the most important, while as a noun, it means head of a school. A principle, on the other hand, is a general theorem or law or a system’s underlying foundation.

NO Our approach is based on the scientific principals of behavioral analysis.

YES Our approach is based on the scientific principles of behavioral analysis.

YES The principal idea of our approach is that early socialization affects behavior.

4. Advice vs advise

Since to advise means to give advice, the main difference between the two is that one is a noun and one is a verb. You therefore don’t have to worry about meaning when using these two, but only about correct grammar.

NO Patients should be adviced against smoking after cancer treatment

YES Patients should be advised against smoking after cancer treatment.

YES Our advice to patients after cancer treatment is to stop smoking.

5. Accept vs except

Accept and except sound almost identical but mean very different things – accept means to consent or to receive, while the verb and the preposition (to) except both mean to not include.

NO Subjects were called back after 2 weeks, accept for those who had dropped out.

YES Subjects were called back after 2 weeks, except for those who had dropped out.

YES Smoking is widely accepted as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease

6. Alternate vs alternative

An alternative is an additional or different option or choice, while alternating refers to the action of switching between choices, states or actions

NO TMS has emerged as an alternate treatment option for anxiety.

YES TMS has emerged as an alternative treatment option for anxiety.

YES We explored the role of alternate care sites in responsiveness to COVID-19

8. Adapt vs adopt

To adopt is to take something and make it your own, while to adapt means changing an existing idea or approach so that it suits your needs. These words often seem to be used interchangeably, but because they sound so similar, you have to make sure you are using the correct one that conveys your intended meaning.

YES Many recent studies have adopted a similar cross-sectional design.

YES We adapted the usual clinical design to better reflect patient characteristics.

9. Access vs assess

To access means to enter or approach or take hold of something, while to assess means to evaluate, determine, or judge.

NO The aim of this study was to access the clinical outcomes of the seton procedure.

YES The aim of this study was to assess the clinical outcomes of the seton procedure.

YES Author KA was granted access to patient data by the hospital ethics committee.

Words with Similar Meanings but Different Connotations

1. Infer vs Imply

Implying means to suggest something while not directly showing or saying it. Inferring, on the other hand, means that you come to a conclusion, based on clear evidence, on your own assumptions, or on what your data or someone else imply.

YES These findings imply that neuropeptides play a role in feeding behavior.

YES Intuitive responders infer that everybody responds as they do

2. Among vs Between

Many authors, native as well as non-native speakers of English, seem to be confused about how to use among and between correctly. The problem is that there are essentially two rules on how to use these two, one that is well-known but in essence an oversimplification and one that is lesser known but explains the difference more precisely. Rule 1 says that you use between for comparisons between two things and among when you refer to groups or sets of more than two elements.

While you will very often choose the correct word when you follow this rule, this approach can lead to “overcorrections” that sound awkward. That’s where Rule 2 comes into play, which states that you can use between for any number of elements, as long as all the elements are separate and distinct. You can choose between eggs and cereals or between eggs, cereals, and toast for breakfast. Among is used for people or things that are not distinct and viewed as a group rather than as individual elements. Negotiations between Italy and Denmark (a comparison of two distinct countries) or among the EU member states (seen as a group) can fail. You share secrets between friends (from person to person) but you feel comfortable with or among your friends.

YES MoO3 showed the best performance among the investigated HDO catalysts.

YES There was no behavioral difference between the test and the control group.

3. Amount vs Number

These words might seem similar in meaning, but their correct usage is related to the concept of countable and uncountable nouns in English. Number can only be used with countable nouns, while amount is used with uncountable nouns.

NO The number of literatures included in this meta-analysis is enormous.

YES The amount of literature included in this meta-analysis is enormous.

YES The number of earlier studies on this topic is low.

Using the Correct Word Stem with the Wrong Prefix or Suffix

Additions to the beginning (prefixes) or end (suffixes) of root words can change a word from an adjective (e.g., happy) into a noun (happiness), or an adverb (happily), into its opposite (unhappy), or affect the tense of a verb. The problem with prefixes and suffixes is that they cannot be used with every word and that they do not always have the same effect. You therefore need to make sure you don’t create words that do not exist or change your intended meaning by adding the wrong prefix or suffix.

NO Changes were determinated using a computer-controlled spectrophotometer.

YES Changes were determined using a computer-controlled spectrophotometer.

NO Protein instableness is a common issue in protein pharmaceuticals.

YES Protein instability is a common issue in protein pharmaceuticals.

NO We assessed sources of diagnostic inaccurateness of cardiac markers.

YES We assessed sources of diagnostic inaccuracy of cardiac markers.

Translation Errors and Collocations

Thinking in your native language and translating phrases literally into English because they sound “natural” is one of the most common reasons for incorrect or awkward expressions in English texts written by non-native authors. While understanding and correcting such mistakes might seem more difficult than grasping the difference between two similar verbs, there are ways for you to avoid such errors.

For example, you can check your wording with Google Scholar or the Merriam-Webster online dictionary, and self-editing your text with the help of our lists of common expressions in research papers or the most useful verbs for the different parts of a paper will make your writing much stronger. And while you are at it, you are also well-advised (not “adviced”) to check your use of prepositions, another common source of mistakes in English writing. If you are not even sure what kind of expressions you might need to check, the following list of commonly mistranslated/misused expressions can give you an idea.

NO Patients underwent dizziness and worsening symptoms.

YES Patients experienced dizziness and reported worsening symptoms.

YES Patients presented with dizziness and showed worsening symptoms over time.

NO Patients underwent a questionnaire after the experiment.

YES Patients filled in a questionnaire after the experiment.

NO Patients succeeded complete remission.

YES Patients achieved complete remission.

NO The difference between groups was obtained with one-way ANOVA.

YES The difference between groups was assessed with one-way ANOVA.

Make sure who does or shows or undergoes something and that the subjects and verbs of your sentences always correspond to each other.

NO Patients performed liver biopsy.

YES Patients underwent liver biopsy.

YES Two experienced surgeons performed liver biopsy.

You also need to pay attention to the difference between people and things, because some verbs only go with one or the other.

NO The study was not able to analyze age differences, due to its design.

YES We were not able to analyze age differences, due to the design of our study.

NO PET alone was not able to diagnose our patients.

YES We were not able to diagnose our patients using PET alone.

Spelling Mistakes That Change Your Meaning

Some mistakes simply stem from phonemic differences between English and other languages. For example, native speakers of languages that do not clearly distinguish between “r” and “l” might misspell words in English without noticing. This is no problem when you make a real spelling mistake and your spellchecker catches it. But sometimes, the incorrect spelling results in a correct word that a spell checker will not flag. Such mistakes can only be avoided by careful proofreading.

NO Collect doses were determined by a series of tests.

YES Correct doses were determined by a series of tests.

NO We did not arrow participants to leave the room between sessions.

YES We did not allow participants to leave the room between sessions.

Before submitting your academic document to journals, be sure to receive professional editing services, including paper editing services, to fix any remaining language and style issues. And to correct your writing errors in real-time, try our ai online editor, Wordvice AI.

If you’ve been writing for any length of time at all, you know that word choice is crucial. I’ve written professionally for 15 years and word choice still sometimes stumps me.

What is a non-specific word choice?

A non-specific word choice is a word choice that is vague and does not convey a sense of the specific details. Non-specific word choices include generic words like “thing,” “stuff,” “them,” or “that.”

The best way to learn about non-specific word choice is to see actual examples. That’s why I’ve included a table of clear examples below so that you can understand without any confusion.

Keep reading to learn when and how to use non-specific word choice, and seven simple ways to fix non-specific word choice in your writing.

My favorite tool for quickly improving, rephrasing, simplifying, or expanding my writing is by far the Jasper AI Writer (formerly known as Jarvis).

(This post may have afilliate links. Please see my full disclosure)

I thought it might be helpful to include a table of examples of non-specific word choices. I’ll bold the non-specific word choice so they stand out.

Study this table so that you absorb all the variations.

By doing so, you’ll be able to identify non-specific word choices in your writing—whether in essays, emails, reports, papers, articles, or stories.

| Example Sentence | Non-Specific Word |

|---|---|

| I want that. | That |

| She went to the place. | Place |

| A person called me. | Person |

| Meet me at the location. | Location |

| This happened long ago. | This |

| Everyone came to the party. | Everyone |

| He walked the animal. | Animal |

| You should go to the event. | Event |

| The vehicle drove away. | Vehicle |

| I’ll be in the room. | Room |

| It has become very clear that… | It |

| There are several reasons to believe. | Reasons |

| The evidence is clear. | Evidence |

| We can rely on the results. | Results |

| The presentation was informative. | Presentation |

| He is able to attend the meetings. | Meetings |

| The project is developing smoothly. | Project |

| She needs support from people at work. | People |

| Their team will be doing an important job. | Job |

| Everybody participated and shared their ideas and knowledge. | Everybody |

Please note that these sentences include non-specific words mostly because they exist in isolation.

Yes, you can improve most of the sentences with a bit more specifics, however, some of the sentences might work in the context of a larger, more specific paragraph offering the reader details.

How To Easily Spot a Non-Specific Word Choice

The easiest way to spot a non-specific word choice is to ask a simple question of all of your sentences.

The simple question is, “What detail is missing?”

Here are other variations of this question you might want to use:

- Who exactly?

- Where exactly?

- When exactly?

- What exactly?

Let’s look at an example. Suppose you write the sentence, “I can’t stand the person!” Since this sentence is about a person, you can ask, “Who exactly?” As in, “Who exactly can’t you stand?”

The identity of the person in the sentence is not identified, so someone eavesdropping on the conversation would not understand your meaning. To fix this sentence, you could change it to read, “I can’t stand Chad!”

Now, anyone listening knows you don’t like Chad, specifically. They might know Chad, but you are still writing a clear and defined sentence.

Is Non-Specific Word Choice Bad?

By now, you might be wondering if using non-specific word choice is always bad. The answer is no.

There are times to use non-specific words and times you probably want to avoid vague or unclear words. It really depends on the context. In school, teachers often focus on writing more specific sentences.

That’s why many of us mistakenly believe specific is always better.

It’s also true that writing with more detail is often the correct choice. Most of the time, adding specific information to clarify your meaning improves your writing.

However, this is not always the case, every time.

Since I want you to master non-specific word choice, we’re going to look at when to use it to maximize your writing.

When To Use Non-Specific Word Choice? (9 Best Times)

There are writing circumstances where non-specific word choice is preferred over specific word choice.

Here’s a quick list of some of these circumstances:

- When you intentionally want your meaning to be vague

- When you want to create mystery or suspense

- When knowing the details would ruin a later surprise

- When the details don’t matter

- When you have already mentioned the details earlier (so there’s no need to repeat them in every sentence)

- When the reader (or person receiving your writing) knows what you mean

- When you speak in slang or jargon for privacy or confedentiality

- When a character in your story speaks in non-specific sentences (part of their characterization)

- When a character in your story is intentionally being unclear or vague

You might notice that the common denominator in all of these reasons is intention. Only use non-specific words on purpose.

Also, check out this related video on word choice:

When To Use Specific Word Choice?

There are also times to use specific word choices. As I mentioned earlier, MOST of the time, you want to write more detailed sentences. Most writing suffers from a lack of clarity, not over-specificity.

When to use specific word choices?

I agree with Mark Twain who once famously said, “The difference between the right word and the wrong word is the difference between lightning and lightning bug.”

Word choice matters.

Here are seven times you should use specific word choices:

- When you want the best short word

- When you want the most evocative word

- When you want a contrasting word

- When you want a concrete word

- When you need the most clear word

- When you prefer a lyrical word

- When you want to find the “right” word

We’re going to take each of these reasons one at a time.

Why you should use short words

You should use short words because short words are simple and short sentences are often more effective.

Short words also increase the speed at which you write and communicate. Short sentences force clarity. Short, simple words can improve your technical writing, help your readers understand what you’re saying, and make your writing more enjoyable for everyone involved.

Short, hyper-specific words also pack more punch.

Example: Use “fox” instead of animal and “sin” instead of wrongdoing.

Why you should use evocative words

You should use evocative words because evocative words generate emotion through meaning and association (shame, baby, funeral).

Not all writing requires emotion or visceral reactions (say, a work autoresponder email message letting your colleagues know you’re on vacation).

However, for most nontechnical writing, a little emotion can go a long way. Specific words can be very evocative.

Example: The first time I laid eyes on my baby, my soul swooned.

Why you should use contrast words

You should use contrast words because they grab attention with an odd pairing: wet sand, cold fire, beautiful atrocity.

Applying contrast words in your writing can simultaneously elevate and deepen your writing.

At its core, contrast makes for better writing by creating interest and drama by pairing seemingly incompatible ideas.

For example, the sound of shouting or the sound of silence.

Why you should use concrete words

Concrete words are visual, sensory words that lend to showing, not telling. Instead of saying something is “good” or “beautiful,” you can say that it’s “wide-eyed and bright-faced.”

Instead of telling the reader that a character is nervous, you can describe the jittery dance of his fingers.

Concrete words invoke concrete images.

Examples: Shards of glass. Shattered hoof.

Why you should use clear words

Clear words improve understanding and convey accurate meaning. Keeping clear words in your writing will help retain the interest of readers. Clear word choice also reduces confusion and improves retention.

Example: Tuesday, November 13th, instead of “next week.”

Why you should use lyrical words

Lyrical words flow, lilt, and play music in the “ear” of the reader. They are lyrical because they sound musical, sing-songy, or melodious. However, they tend to be more subtle. They create sounds or images in the “mind’s ear” of your readers.

Lyrical words paint pictures that stretch the imagination and imbue your writing with a sense of sound.

Example: Prose, serendipity, facetious.

Why you should use the “right” words

The “right” words are words that best fit into the collective narrative of the sentence. When writing, you have to consider the “tone of voice” or how you want the sentence or scene to feel (to the reader).

If a sentence is light-hearted and funny, then the words used should match that tone. If a sentence is serious and strict, then the words should match that tone as well.

Always consider the context of the sentence, paragraph, page, scene, and story. As an editor once told me, “beautiful girls don’t ‘plop’.”

Final Thoughts: What Is a Non-Specific Word Choice?

The bottom line is that a non-specific word choice is unclear. It’s a barrier to good communication. You can immediately improve most sentences by making them more clear.

My secret sauce for writing that gets results is Jasper (AI Writer formerly known as Jarvis).

Yes, it still takes your skill and guidance, but it’s hands-down the best way to quickly scale your writing production and improve your results. Jasper helps you write emails, essays, papers, reports, articles, even books. Click on the image below to check out what Jasper can do for you!

For more articles on writing, read these blog posts next:

- How To Write Jasper/Jarvis Blog Posts (7 Best Tips)

- Stephen King Twitter (9 Things You Need To Know)

- Is Medium Worth It? (SOLVED for Readers and Writers)

Resources:

Writers.com

Word choice: Hidden Meaning

You’ve done your research, picked out your keywords, and now all that is left to do is actually write the article. Rather than just cranking it out and sending it on its way, however, make sure that you pay attention to style and word choice as you’re writing. Paying attention to detail and writing up your content in a more compelling style could make the difference between a quick sell and an article that takes months to sell.

Write with Your Keywords in Mind

Gone are the days of overly plush prose and titles with no clear connection the content. If you’re a web writing pro then this isn’t news to you, but if you have a penchant for hyperbole, pay attention. Since search queries rely on keywords to scroll content, it’s important to use your keywords throughout the article, especially in prominent places like the title, subheadings, and topic sentences. Keeping the keywords in mind lets webmasters know that you’ve considered SEO and integrated its best practices into your writing process so that the article will be easier to find on the web.

Don’t Get Too Repetitive

While it’s important to use keywords in your web writing, don’t overdo it. If your sentences start to seem repetitive, or if the article’s readability degrades due to “keyword stuffing,” then you’ve gone too far and need to figure out how to add a bit more variety to the piece. Website owners know that keyword stuffing is a “black hat” SEO practice, but even if you’re not committing one of the cardinal sins of SEO, relying too much on the same words and turns of phrase can become redundant to the reader, causing him to lose interest. Try to incorporate a number of transitional words and phrases so that your writing flows seamlessly from one point to the next, and write with a thesaurus so that you’re not using the same words over and over again. If your article reads well, then it’s more likely to sell.

Keep It Short and Sweet

Although some of history’s greatest writers wrote pages and pages of prose with hardly a period between it all, when most of us try to do the same we end up confusing both the reader and ourselves. Long sentences made up of several independent clauses run the risk of losing their internal logic or contradicting themselves. Also, writing lots of unusually long sentences increases the threat of sentence structure errors since these sentences tend to rely on several commas and conjunctions to tie clauses together. Even if you manage to avoid grammar mistakes, too many long sentences tend to weigh down a piece on the whole. Aim for a fresh, clear style of writing and you’ll have a greater chance of convincing content seekers that they just have to buy your article.

Don’t Forget about Grammar

Good writing usually follows the rules of grammar, and writing an error-free article could make all the difference between a compelling read and one that is hard to follow. Avoiding sentence fragments and respecting subject-verb agreement are two strategies that you should bear in mind during the writing process. Most native English speakers have an intuitive sense of subject-verb agreement, although it’s easy to mess it up occasionally, especially when the subject is separated from the verb. Take this sentence for example: “That guy who was wearing the corduroy sweater and bumped into us when we were in line to meet the Knicks was kind of a jerk.” In this example, “That guy” is the subject and “was” is the verb that agreed with it, but you could have lost track of this when reading the sentence due to the “who” clause between the subject and the verb. Since “Knicks” is a plural noun, you might think that “was” should be plural as well if you forgot which noun is the subject of the sentence.

There are many other grammar and sentence structure standards that are essential to good writing, including parallelism, avoiding typos, and pronoun-antecedent agreement. By paying attention to the details and thinking creatively, you could separate yourself from the pack and become a writer who sells almost as soon as he hits “Submit.”

The words a writer chooses are the building materials from which he or she constructs any given piece of writing—from a poem to a speech to a thesis on thermonuclear dynamics. Strong, carefully chosen words (also known as diction) ensure that the finished work is cohesive and imparts the meaning or information the author intended. Weak word choice creates confusion and dooms a writer’s work either to fall short of expectations or fail to make its point entirely.

Factors That Influence Good Word Choice

When selecting words to achieve the maximum desired effect, a writer must take a number of factors into consideration:

- Meaning: Words can be chosen for either their denotative meaning, which is the definition you’d find in a dictionary or the connotative meaning, which is the emotions, circumstances, or descriptive variations the word evokes.

- Specificity: Words that are concrete rather than abstract are more powerful in certain types of writing, specifically academic works and works of nonfiction. However, abstract words can be powerful tools when creating poetry, fiction, or persuasive rhetoric.

- Audience: Whether the writer seeks to engage, amuse, entertain, inform, or even incite anger, the audience is the person or persons for whom a piece of work is intended.

- Level of Diction: The level of diction an author chooses directly relates to the intended audience. Diction is classified into four levels of language:

- Formal which denotes serious discourse

- Informal which denotes relaxed but polite conversation

- Colloquial which denotes language in everyday usage

- Slang which denotes new, often highly informal words and phrases that evolve as a result sociolinguistic constructs such as age, class, wealth status, ethnicity, nationality, and regional dialects.

- Tone: Tone is an author’s attitude toward a topic. When employed effectively, tone—be it contempt, awe, agreement, or outrage—is a powerful tool that writers use to achieve a desired goal or purpose.

- Style: Word choice is an essential element in the style of any writer. While his or her audience may play a role in the stylistic choices a writer makes, style is the unique voice that sets one writer apart from another.

The Appropriate Words for a Given Audience

To be effective, a writer must choose words based on a number of factors that relate directly to the audience for whom a piece of work is intended. For example, the language chosen for a dissertation on advanced algebra would not only contain jargon specific to that field of study; the writer would also have the expectation that the intended reader possessed an advanced level of understanding in the given subject matter that at a minimum equaled, or potentially outpaced his or her own.

On the other hand, an author writing a children’s book would choose age-appropriate words that kids could understand and relate to. Likewise, while a contemporary playwright is likely to use slang and colloquialism to connect with the audience, an art historian would likely use more formal language to describe a piece of work about which he or she is writing, especially if the intended audience is a peer or academic group.

«Choosing words that are too difficult, too technical, or too easy for your receiver can be a communication barrier. If words are too difficult or too technical, the receiver may not understand them; if words are too simple, the reader could become bored or be insulted. In either case, the message falls short of meeting its goals . . . Word choice is also a consideration when communicating with receivers for whom English is not the primary language [who] may not be familiar with colloquial English.»

(From «Business Communication, 8th Edition,» by A.C. Krizan, Patricia Merrier, Joyce P. Logan, and Karen Williams. South-Western Cengage, 2011)

Word Selection for Composition

Word choice is an essential element for any student learning to write effectively. Appropriate word choice allows students to display their knowledge, not just about English, but with regard to any given field of study from science and mathematics to civics and history.

Fast Facts: Six Principles of Word Choice for Composition

- Choose understandable words.

- Use specific, precise words.

- Choose strong words.

- Emphasize positive words.

- Avoid overused words.

- Avoid obsolete words.

(Adapted from «Business Communication, 8th Edition,» by A.C. Krizan, Patricia Merrier, Joyce P. Logan, and Karen Williams. South-Western Cengage, 2011)

The challenge for teachers of composition is to help students understand the reasoning behind the specific word choices they’ve made and then letting the students know whether or not those choices work. Simply telling a student something doesn’t make sense or is awkwardly phrased won’t help that student become a better writer. If a student’s word choice is weak, inaccurate, or clichéd, a good teacher will not only explain how they went wrong but ask the student to rethink his or her choices based on the given feedback.

Word Choice for Literature

Arguably, choosing effective words when writing literature is more complicated than choosing words for composition writing. First, a writer must consider the constraints for the chosen discipline in which they are writing. Since literary pursuits as such as poetry and fiction can be broken down into an almost endless variety of niches, genres, and subgenres, this alone can be daunting. In addition, writers must also be able to distinguish themselves from other writers by selecting a vocabulary that creates and sustains a style that is authentic to their own voice.

When writing for a literary audience, individual taste is yet another huge determining factor with regard to which writer a reader considers a «good» and who they may find intolerable. That’s because «good» is subjective. For example, William Faulker and Ernest Hemmingway were both considered giants of 20th-century American literature, and yet their styles of writing could not be more different. Someone who adores Faulkner’s languorous stream-of-consciousness style may disdain Hemmingway’s spare, staccato, unembellished prose, and vice versa.

Should I use this word or that one? Does this sentence mean what I think it means? If you have had such a thought, you are not the only one. Errors in word usage account for a significant proportion of language problems in research papers written by non-native English speakers. Just as every discipline has its own set of conventions, there are certain errors that researchers in every discipline are prone to. Our editors have identified some recurrent errors that are more commonly found in the physical sciences research papers than in other fields.

In a research paper, language is the medium to disseminate your findings, so using words effectively is crucial importance. Therefore, it is best to be aware of and avoid the errors in word usage that could have an impact on the clarity of your manuscript. This article lists some examples of commonly observed errors in word usage and provides tips on how you can avoid them.

1. Words with similar sounds or meanings

Using a word that sounds similar to the intended word but has a different meaning is one of the most common errors in word choice. Among native speakers, such an error is often just a slip of the tongue. Among non-native speakers, however, it could be the result of genuine confusion.

In many cases, similar-sounding words may have similar (but not the same) meaning, which adds to the confusion. Let’s see how.

Example 1: Attained and obtained

Incorrect: The sensors attained steady state readings at high temperatures.

Correct: The sensors obtained steady state readings at high temperatures.

Attain means reach and is mostly used when talking about a condition or stage (e.g., “the larva attains maturity”), while Obtain simply means get (e.g., “he obtained data from hospital records”).

Example 2: Principal and principle

Incorrect: The principle components of the thermochemical state were used to derive the transport equations.

Correct: The principal components of the thermochemical state were used to derive the transport equations.

The word principle is a noun meaning a rule or law (e.g., “principle of conservation of mass”), whereas principal is an adjective meaning main or important or primary (e.g., “principal findings of the study”). These two are often mistakenly interchanged because of their similar sounds.

2. Spelling errors due to differences in pronunciation

Sometimes, the cultural aspects play a role in spelling errors. For instance, our editors have noticed a common case of confusion among Japanese authors, which most of you must already be aware of. It is the classic confusion between the letters “l” and “r.” This, as you know, is because of the phonemic differences between English and Japanese.

In most cases, a spellcheck program will catch such errors. But sometimes, the incorrect version may be a valid spelling too. For instance, spell check won’t recognize the problem when an author says “correct” instead of “collect,” “arrow” instead of “allow,” or “rock” instead of “lock.” The only way to avoid these errors is to be extra careful when writing them, looking up spellings of at least the “r/l” words you use most frequently in a paper, and doing a thorough proofread at the end, once you have completed writing the entire manuscript.

Example

Incorrect: The poles were displaced in the direction of the applied pressure.

Correct: The pores were displaced in the direction of the applied pressure.

3. Words with similar meanings but different connotations

Now let’s see how words that don’t sound similar but have similar or overlapping meanings can be misused.

Example 1: Devised and developed

Incorrect: We have devised a method to calculate the exergy efficiency.

Correct: We have developed a new method to calculate the exergy efficiency.

Both devise and develop mean coming up with something new, but the meaning of devise is restricted to an idea or a plan, whereas develop is generally used for a product or system invented.

Example 2: Alternate and alternative

Incorrect: Alternate measures were developed to reliably calculate the losses.

Correct: Alternative measures were developed to reliably calculate the losses.

While both alternate and alternative mean a substitute or a different choice of something, the word alternate could also be used to indicate something that is in a constant state of change (e.g., “alternating current”).

4. Using non-standard or non-existent forms of words

Sometimes, authors may add a prefix or suffix to a root word to form verbs, nouns, or adjectives that are either non-standard or non-existent.

Example 1

Incorrect: The structural changes were determinated through microscopy studies.

Correct: The structural changes were determined through microscopy studies.

Verbs, nouns, and adjectives can be formed from other words (called root words) by adding appropriate suffixes (e.g., –ify, –er, –al, –ate, -ly, –able, –ish, –ion). But these have to be standard, accepted spellings and cannot be arbitrarily created. In the example above, the author has erroneously added the suffix –ated to the root word determine, whereas the correct term is determined. (Note that the tense and plural forms of words are also achieved by appending suffixes.)

Example 2

Incorrect: The unbalance between the compositions of the combustion residues can cause changes in accuracy and efficiency.

Correct: The imbalance between the compositions of the combustion residues can cause changes in accuracy and efficiency.

Antonyms of English words can be formed by adding several prefixes: in–, im–, un–, a–, an–, il–, ir–, non–, and so on. There is generally a linguistic/etymological rationale for which prefixes are used with which words. But the rules are highly variable and seem arbitrary. A dictionary or a thesaurus is the best guide for choosing the right form.

In the example above, the author has used unbalance, which is in fact more commonly used as a verb (e.g., “to unbalance someone”). The standard noun form is imbalance.

Example 3

Incorrect: Because of the unstableness of this process, the steady-state condition may vary.

Correct: Because of the instability in this process, the steady-state condition may vary.

Since the root word here is unstable, the author has assumed that the noun form will have the suffix –ness. However, instability is the right noun form. Some other examples of words that are used in non-standard forms are clean (incorrect: cleanness, correct: cleanliness), inaccurate (incorrect: inaccurateness, correct: inaccuracy), and intelligent (incorrect: intelligentness, correct: intelligence). This is a non-exhaustive list, so please be sure to always check the appropriate form of usage.

5. Use of plurals (countable or uncountable)

One of the most common hurdles encountered by authors who are unfamiliar with the finer nuances of the English language is the differentiation between countable and uncountable nouns. Countable nouns are those that refer to something that can be counted and then expressed in a unique singular/plural form, e.g., sample/samples, temperature/temperatures, and atom/atoms. Uncountable nouns are often used to represent collective forms using either the singular or plural reference, but never both.

Examples of words used exclusively in uncountable form:

Information (e.g., “this information is crucial to the subsequent modeling process,”

Performance (e.g., “the performance of the samples was evaluated”, “a series of tests were conducted”)

Examples of words that have countable forms but are preferably used in uncountable form: Data (plural of “datum”; this word is recommended to be used in singular form in the APA and Chicago styles but always in the plural form in the IEEE style), research (the plural form of this word “researches” can often be mistaken as a verb, so the singular form is always recommended)

Sometimes, authors get confused when using words that indicate quantity. Words that clearly indicate discrete values should be used with countable nouns. The only exclusion to this rule would be units of measurement, which are always written in singular form when accompanied by numbers (e.g., 3 second, 4.2 meter, 6 ampere, 285 kelvin, 685 joule).

Words such as number or series are by themselves singular, but may take on plural forms depending on context. “A number” can be singular or plural depending on the parameter it modifies (e.g., “A number of samples were examined” is plural because the term “samples” is plural, “A number X is chosen to represent the length of the vector” is singular because the variable “X” is a singular parameter). Similarly, the word “series” is always considered singular when accompanied by the article “a” (e.g., “a series of measurements is obtained”, “these series of values were analyzed to obtain the means and distribution characteristics”).

6. Incorrect collocations

Collocations are combinations of words that appear together very frequently and have evolved as natural phrasing in English. For example, “heavy rain” and “strong wind” are collocations. The words rain and wind can be described by many adjectives, but heavy and strong, respectively, are among the more common ones. You would not say “strong rain” or “heavy wind;” that does not sound natural.

To native speakers, these collocations come naturally, but non-native speakers often struggle to get them right. Please go through the following sentences carefully, focusing on the words in blue. The corrections (in red) show which words go better with those in blue.

Examples:

- Researchers should

maintainexercise extreme caution when performing this procedure. - The device was

constructeddesigned to withstand extreme variations in temperature. - Only 40% of the samples showed

entirefull compliance for the required characteristics.

The original word choices (strikethrough text) may have seemed grammatically and logically correct to the author when used with the words in blue, but these combinations sound odd because they go against the natural instinct of a native-speaking reader.

Related reading:

- Avoid the most common errors of grammar in research papers

- Punctuation…?: A useful guide for academic writing