На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

выбор слов

выбора слов

выборе слов

подбор слов

выбора слова

выборе слова

выбором слов

выбору слов

слова избранность

Tone is just as important as word choice.

Тон голоса так же важен, как и выбор слов.

Your word choice might not seem important, but it can actually help you sound more intelligence.

Ваш выбор слов может показаться не важным, но она может реально помочь вам звук больше интеллекта.

It’s an interesting word choice, since you already did.

Интересный выбор слова, так как ты уже настроила.

The right word choice can help change their perspective for better or for worse.

Правильный выбор слова может помочь изменить перспективу человека в лучшую или худшую сторону.

If you only make an occasional pronunciation mistake while having perfect grammar and word choice, you’ll be okay.

Если Вы делаете случайную ошибку произношения, имея идеальную грамматику и словарный запас, все в порядке.

However, word choice, style, syntax and narrative focus all indicate Faulkner as almost certainly being the author of this work.

Тем не менее, словарный запас, стиль, синтаксис и манера изложения указывают, что автором этого произведения почти наверняка является Фолкнер.

Additionally, poor word choice can lead to confusing sentences, decreasing the quality of your communication with site visitors.

Кроме того, неправильный выбор слов может привести к путанице в предложениях, что приведет к снижению качества общения с посетителями сайта.

Often, it’s just a case of word choice and simple formatting.

Часто это просто выбор слов и простое форматирование.

Even my word choice is different.

Because the word choice has no meaning.

Careful word choice is important in this field, as is an attention to detail.

Тщательный выбор слова имеет важное значение в этой области, как и внимание к деталям.

The tone and word choice throughout the copy should speak the brand’s language.

Тон и выбор слова в тексте должны соответствовать языку бренда.

You now have the opportunity to refine your word choice.

К счастью, у вас еще есть шанс пересмотреть свой выбор слов.

This is the same as a piece of literature or rhetoric delivering its information through word choice, layout, and structure.

Это то же самое, как часть литературы или Риторика доставки информации через выбор слов, макет и структуру.

Of course, my English teacher always taught me that word choice is key.

Конечно, мой преподаватель английского всегда учил меня, что выбор слов является ключевым.

The researchers measured parents’ vocal responses, word and sentence length, and word choice when they responded to their infants’ vocalizations.

Исследователи измерили голосовые ответы родителей, длину слова и предложения и выбор слова, когда они отвечали на слова и вопросы своих детей.

Compelling headlines often zero in on a common pain point that the product or service solves and include careful word choice that reflects the voice of the brand.

Убедительные заголовки часто указывают на общую болевую точку, которую решает продукт или услуга, и включают тщательный выбор слов, который отражает голос бренда.

Refine your spelling, grammar, and word choice to enhance your content

Улучшайте свое правописание, грамматику и выбор слов, чтобы улучшить содержание

Find out the choices that appeal most to your target audience, whether it’s with colors, fonts, offers, or word choice.

Узнайте, какие варианты больше всего подходят для вашей целевой аудитории, будь то цвета, шрифты, предложения или выбор слов.

Open word choice: Ask users to list 3 to 5 words that describe the design

Открытый выбор слов: попросите пользователей привести от З до 5 слов, описывающих конкретный дизайн

Результатов: 137. Точных совпадений: 137. Затраченное время: 113 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

All strong writers have something in common: they understand the value of word choice in writing. Strong word choice uses vocabulary and language to maximum effect, creating clear moods and images and making your stories and poems more powerful and vivid.

The meaning of “word choice” may seem self-explanatory, but to truly transform your style and writing, we need to dissect the elements of choosing the right word. This article will explore what word choice is, and offer some examples of effective word choice, before giving you 5 word choice exercises to try for yourself.

Word Choice Definition: The Four Elements of Word Choice

The definition of word choice extends far beyond the simplicity of “choosing the right words.” Choosing the right word takes into consideration many different factors, and finding the word that packs the most punch requires both a great vocabulary and a great understanding of the nuances in English.

Choosing the right word involves the following four considerations, with word choice examples.

1. Meaning

Words can be chosen for one of two meanings: the denotative meaning or the connotative meaning. Denotation refers to the word’s basic, literal dictionary definition and usage. By contrast, connotation refers to how the word is being used in its given context: which of that word’s many uses, associations, and connections are being employed.

A word’s denotative meaning is its literal dictionary definition, while its connotative meaning is the web of uses and associations it carries in context.

We play with denotations and connotations all the time in colloquial English. As a simple example, when someone says “greaaaaaat” sarcastically, we know that what they’re referring to isn’t “great” at all. In context, the word “great” connotes its opposite: something so bad that calling it “great” is intentionally ridiculous. When we use words connotatively, we’re letting context drive the meaning of the sentence.

The rich web of connotations in language are crucial to all writing, and perhaps especially so to poetry, as in the following lines from Derek Walcott’s Nobel-prize-winning epic poem Omeros:

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez,

the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane

down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain

marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

Sugar cane isn’t, literally, made of “feathered lances,” which would literally denote “long metal spears adorned with bird feathers”; but feathered connotes “branching out,” the way sugar cane does, and lances connotes something tall, straight, and pointy, as sugar cane is. Together, those two words create a powerfully true visual image of sugar cane—in addition to establishing the martial language (“spears,” “marching”) used elsewhere in the passage.

Whether in poetry or prose, strong word choice can unlock images, emotions, and more in the reader, and the associations and connotations that words bring with them play a crucial role in this.

2. Specificity

Use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description.

In the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms. That’s why it’s important to use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description. Words like “good,” “average,” and “awful” are far less descriptive and specific than words like “liberating” (not just good but good and freeing), “C student” (not just average but academically average), and “despicable” (not just awful but morally awful). These latter words pack more meaning than their blander counterparts.

Since more precise words give the reader added context, specificity also opens the door for more poetic opportunities. Take the short poem “[You Fit Into Me]” by Margaret Atwood.

You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

A fish hook

An open eye

The first stanza feels almost romantic until we read the second stanza. By clarifying her language, Atwood creates a simple yet highly emotive duality.

This is also why writers like Stephen King advocate against the use of adverbs (adjectives that modify verbs or other adjectives, like “very”). If your language is precise, you don’t need adverbs to modify the verbs or adjectives, as those words are already doing enough work. Consider the following comparison:

Weak description with adverbs: He cooks quite badly; the food is almost always extremely overdone.

Strong description, no adverbs: He incinerates food.

Of course, non-specific words are sometimes the best word, too! These words are often colloquially used, so they’re great for writing description, writing through a first-person narrative, or for transitional passages of prose.

3. Audience

Good word choice takes the reader into consideration. You probably wouldn’t use words like “lugubrious” or “luculent” in a young adult novel, nor would you use words like “silly” or “wonky” in a legal document.

This is another way of saying that word choice conveys not only direct meaning, but also a web of associations and feelings that contribute to building the reader’s world. What world does the word “wonky” help build for your reader, and what world does the word “seditious” help build? Depending on the overall environment you’re working to create for the reader, either word could be perfect—or way out of place.

4. Style

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing. Every writer uses words differently, and as those words come to form poems, stories, and books, your unique grasp on the English language will be recognizable by all your readers.

Style isn’t something you can point to, but rather a way of describing how a writer writes. Ernest Hemingway, for example, is known for his terse, no-nonsense, to-the-point styles of description. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, is known for writing that’s poetic, intense, and melodramatic, and James Joyce for his lofty, superfluous writing style.

Here’s a paragraph from Joyce:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.

And here’s one from Hemingway:

Bill had gone into the bar. He was standing talking with Brett, who was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed. She had no stockings on.

Style is best observed and developed through a portfolio of writing. As you write more and form an identity as a writer, the bits of style in your writing will form constellations.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Word Choice in Writing: The Importance of Verbs

Before we offer some word choice exercises to expand your writing horizons, we first want to mention the importance of verbs. Verbs, as you may recall, are the “action” of the sentence—they describe what the subject of the sentence actually does. Unless you are intentionally breaking grammar rules, all sentences must have a verb, otherwise they don’t communicate much to the reader.

Because verbs are the most important part of the sentence, they are something you must focus on when expanding the reaches of your word choice. Verbs are the most widely variegated units of language; the more “things” you can do in the world, the more verbs there are to describe them, making them great vehicles for both figurative language and vivid description.

Consider the following three sentences:

- The road runs through the hills.

- The road curves through the hills.

- The road meanders through the hills.

Which sentence is the most descriptive? Though each of them has the same subject, object, and number of words, the third sentence creates the clearest image. The reader can visualize a road curving left and right through a hilly terrain, whereas the first two sentences require more thought to see clearly.

Finally, this resource on verb usage does a great job at highlighting how to invent and expand your verb choice.

Word Choice in Writing: Economy and Concision

Strong word choice means that every word you write packs a punch. As we’ve seen with adverbs above, you may find that your writing becomes more concise and economical—delivering more impact per word. Above all, you may find that you omit needless words.

Omit needless words is, in fact, a general order issued by Strunk and White in their classic Elements of Style. As they explain it:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

It’s worth repeating that this doesn’t mean your writing becomes clipped or terse, but simply that “every word tell.” As our word choice improves—as we omit needless words and express ourselves more precisely—our writing becomes richer, whether we write in long or short sentences.

As an example, here’s the opening sentence of a random personal essay from a high school test preparation handbook:

The world is filled with a numerous amount of student athletes that could somewhere down the road have a bright future.

Most words in this sentence are needless. It could be edited down to:

Many student athletes could have a bright future.

Now let’s take some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Can you remove a single word without sacrificing an enormous richness of meaning?

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In strong writing, every single word is chosen for maximum impact. This is the true meaning of concise or economical writing.

5 Word Choice Exercises to Sharpen Your Writing

With our word choice definition in mind, as well as our discussions of verb use and concision, let’s explore the following exercises to put theory into practice. As you play around with words in the following word choice exercises, be sure to consider meaning, specificity, style, and (if applicable) audience.

1. Build Moods With Word Choice

Writers fine-tune their words because the right vocabulary will build lush, emotive worlds. As you expand your word choice and consider the weight of each word, focus on targeting precise emotions in your descriptions and figurative language.

This kind of point is best illustrated through word choice examples. An example of magnificent language is the poem “In Defense of Small Towns” by Oliver de la Paz. The poem’s ambivalent feelings toward small hometowns presents itself through the mood of the writing.

The poem is filled with tense descriptions, like “animal deaths and toughened hay” and “breeches speared with oil and diesel,” which present the small town as stoic and masculine. This, reinforced by the terse stanzas and the rare “chances for forgiveness,” offers us a bleak view of the town; yet it’s still a town where everything is important, from “the outline of every leaf” to the weightless flight of cattail seeds.

The writing’s terse, heavy mood exists because of the poem’s juxtaposition of masculine and feminine words. The challenge of building a mood produces this poem’s gravity and sincerity.

Try to write a poem, or even a sentence, that evokes a particular mood through words that bring that word to mind. Here’s an example:

- What mood do you want to evoke? flighty

- What words feel like they evoke that mood? not sure, whatever, maybe, perhaps, tomorrow, sometimes, sigh

- Try it in a sentence: “Maybe tomorrow we could see about looking at the lab results.” She sighed. “Perhaps.”

2. Invent New Words and Terms

A common question writers ask is, What is one way to revise for word choice? One trick to try is to make up new language in your revisions.

If you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

In the same way that unusual verbs highlight the action and style of your story, inventing words that don’t exist can also create powerful diction. Of course, your writing shouldn’t overflow with made-up words and pretentious portmanteaus, but if you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

A great example of an invented word is the phrase “wine-dark sea.” Understanding this invention requires a bit of history; in short, Homer describes the sea as “οἶνοψ πόντος”, or “wine-faced.” “Wine-dark,” then, is a poetic translation, a kind of kenning for the sea’s mystery.

Why “wine-dark” specifically? Perhaps because, like the sea, wine changes us; maybe the eyes of the sea are dark, as eyes often darken with wine; perhaps the sea is like a face, an inversion, a reflection of the self. In its endlessness, we see what we normally cannot.

Thus, “wine-dark” is a poetic combination of words that leads to intensive literary analysis. For a less historical example, I’m currently working on my poetry thesis, with pop culture monsters being the central theme of the poems. In one poem, I describe love as being “frankensteined.” By using this monstrous made-up verb in place of “stitched,” the poem’s attitude toward love is much clearer.

Try inventing a word or phrase whose meaning will be as clear to the reader as “wine-dark sea.” Here’s an example:

- What do you want to describe? feeling sorry for yourself because you’ve been stressed out for a long time

- What are some words that this feeling brings up? self-pity, sympathy, sadness, stress, compassion, busyness, love, anxiety, pity party, feeling sorry for yourself

- What are some fun ways to combine these words? sadxiety, stresslove

- Try it in a sentence: As all-nighter wore on, my anxiety softened into sadxiety: still edgy, but soft in the middle.

3. Only Use Words of Certain Etymologies

One of the reasons that the English language is so large and inconsistent is that it borrows words from every language. When you dig back into the history of loanwords, the English language is incredibly interesting!

(For example, many of our legal terms, such as judge, jury, and plaintiff, come from French. When the Normans [old French-speakers from Northern France] conquered England, their language became the language of power and nobility, so we retained many of our legal terms from when the French ruled the British Isles.)

Nerdy linguistics aside, etymologies also make for a fun word choice exercise. Try forcing yourself to write a poem or a story only using words of certain etymologies and avoiding others. For example, if you’re only allowed to use nouns and verbs that we borrowed from the French, then you can’t use Anglo-Saxon nouns like “cow,” “swine,” or “chicken,” but you can use French loanwords like “beef,” “pork,” and “poultry.”

Experiment with word etymologies and see how they affect the mood of your writing. You might find this to be an impactful facet of your word choice. You can Google “__ etymology” for any word to see its origin, and “__ synonym” to see synonyms.

Try writing a sentence only with roots from a single origin. (You can ignore common words like “the,” “a,” “of,” and so on.)

- What do you want to write? The apple rolled off the table.

- Try a first etymology: German: The apple wobbled off the bench.

- Try a second: Latin: The russet fruit rolled off the table.

4. Write in E-Prime

E-Prime Writing describes a writing style where you only write using the active voice. By eschewing all forms of the verb “to be”—using words such as “is,” “am,” “are,” “was,” and other “being” verbs—your writing should feel more clear, active, and precise!

E-Prime not only removes the passive voice (“The bottle was picked up by James”), but it gets at the reality that many sentences using to be are weakly constructed, even if they’re technically in the active voice.

Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

Try writing a paragraph in E-Prime:

- What do you want to write? Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

- Converted to E-Prime: Of course, E-Prime writing won’t best suit every project. The above paragraph uses E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would carry challenges. E-Prime writing endeavors to make all of your subjects active, and your verbs more impactful. While this word choice exercise can bring enjoyment and create memorable language, you probably can’t sustain it over a long writing project.

5. Write Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry, also known as Found Poetry, is a visual creative writing project. You take a page from a published source and create a poem by blacking out other words until your circled words create a new poem. The challenge is that you’re limited to the words on a page, so you need a charged use of both space and language to make a compelling blackout poem.

Blackout poetry bottoms out our list of great word choice exercises because it forces you to consider the elements of word choice. With blackout poems, certain words might be read connotatively rather than denotatively, or you might change the meaning and specificity of a word by using other words nearby. Language is at its most fluid and interpretive in blackout poems!

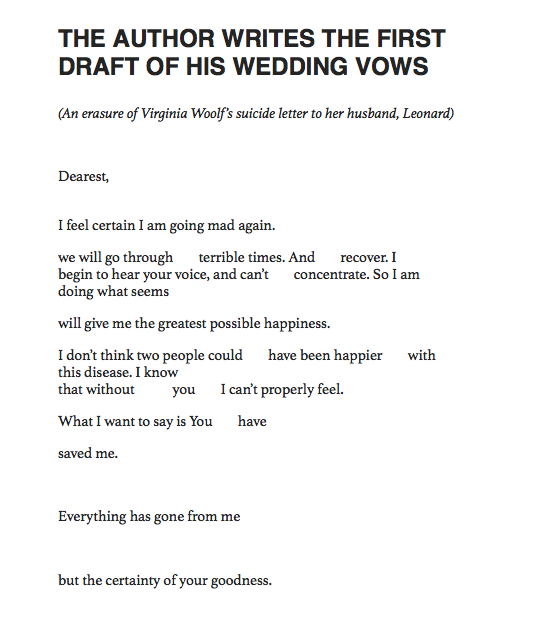

For a great word choice example using blackout poetry, read “The Author Writes the First Draft of His Wedding Vows” by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib. Here it is visually:

Source: https://decreation.tumblr.com/post/620222983530807296/from-the-crown-aint-worth-much-by-hanif

Pick a favorite poem of your own and make something completely new out of it using blackout poetry.

How to Expand Your Vocabulary

Vocabulary is a last topic in word choice. The more words in your arsenal, the better. Great word choice doesn’t rely on a large vocabulary, but knowing more words will always help! So, how do you expand your vocabulary?

The simplest way to expand your vocabulary is by reading.

The simplest answer, and the one you’ll hear the most often, is by reading. The more literature you consume, the more examples you’ll see of great words using the four elements of word choice.

Of course, there are also some great programs for expanding your vocabulary as well. If you’re looking to use words like “lachrymose” in a sentence, take a look at the following vocab builders:

- Dictionary.com’s Word-of-the-Day

- Vocabulary.com Games

- Merriam Webster’s Vocab Quizzes

Improve Your Word Choice With Writers.com’s Online Writing Courses

Looking for more writing exercises? Need more help choosing the right words? The instructors at Writers.com are masters of the craft. Take a look at our upcoming course offerings and join our community!

Download Article

Download Article

Word choice, or diction, is an essential part of any type of writing, and learning to use better word choice can greatly improve your creative writing! The more you think about your diction and practice using better word choice in your stories, the more naturally it will come. We’ve compiled this list of tips and tricks to help you start choosing even better words for your next story.

-

Reading regularly increases your vocabulary. In other words, you’ll know more words to choose from when you write stories. Read whatever is interesting and enjoyable to you, whether it’s fiction, non-fiction, short stories, novels, books, or articles. Add variety to what you read to expose yourself to different styles of diction.[1]

- Even if you typically read crime novels and you want to write crime fiction, it’s still a good idea to switch up what you read to expand your vocabulary outside your comfort zone. For example, you could read a sci-fi or fantasy novel once in a while.[2]

- You can even listen to audiobooks when you’re on the go to get your daily reading in!

- Even if you typically read crime novels and you want to write crime fiction, it’s still a good idea to switch up what you read to expand your vocabulary outside your comfort zone. For example, you could read a sci-fi or fantasy novel once in a while.[2]

Advertisement

-

There are lots of free writing apps that can help you improve your diction.[3]

Download some different ones and try them out when you write. Writing apps help you with the basics like spelling and grammar, but they also make word suggestions and offer alternative sentence structures.[4]

- To find writing apps, search online or in an app store for “writing apps.” Look for ones that have good user ratings and reviews.

- For example, there’s an app called Hemingway that helps you write more like Ernest Hemingway by highlighting sentences that are too long or dense, words that are too complicated, and unnecessary adverbs.

- Some other apps to try are Grammarly, Word to Word, OneLook Reverse Dictionary, and Vocabulary.com.

- There are also vocabulary apps that teach you a word a day to help you further expand your vocab.

-

Variety is the spice of life—and of writing. Highlight words that you use often when you write to identify where you can add some different word choices. Look up synonyms for those words in a thesaurus or brainstorm other ways to convey the meaning you want to get across. Change some of the words and sentences to add more variety to your story.[5]

- When you’re writing on a computer, use CTRL+F to search for and highlight different words.

- Reading a draft out loud can also help you identify passages that are repetitive.

- It’s an especially good idea to eliminate repetition of weak, non-descriptive words, such as “stuff,” “things,” “it,”and “got.” For example, replace “got” with “received,” “obtained,” or “acquired.”

Advertisement

-

This helps convey what you’re really trying to make readers feel. Replace neutral words with alternatives that have positive or negative emotional connotations. One word changes the entire connotation of a sentence or passage.[6]

- For example, replace the word “looked” with “glared” to convey feelings of anger. Or, replace it with “gawked” to convey feelings of disbelief or awe.

- Keep in mind that stronger words aren’t always a better choice than simpler ones. Always consider the message you want to get across when you’re choosing words. In some cases, “looked” may be perfectly adequate!

-

More precise words give the reader better context. Try to replace basic adverbs and adjectives with more descriptive words. Think of other ways you can describe people, places, and things to paint a better picture in the reader’s imagination.[7]

- For example, instead of saying “he was a very average player,” say something like “he was a bench warmer,” which gives the reader an image of the player spending most games sitting on the bench instead of just being an average player on the field.

- Here’s another example: instead of writing “she has a tendency to overcook rice,” write “the rice almost always ends up charred when she cooks it.” The reader can now picture what the rice actually looks like and maybe even imagine the taste of charred rice.

Advertisement

-

Verbs, or the action of a sentence, really bring your writing to life. Come up with 2-3 different verbs that you could use in a given sentence. Choose the best, most descriptive verb for each sentence to make your writing more vivid for the reader.[8]

- For example, instead of writing “the river comes down from the mountains,” write “the river winds down from the mountains.” Changing “comes” to “winds” helps the reader visualize a river bending from left to right as the water flows down from the mountains, instead of just giving them a vague idea of where the body of water is.

-

This can be especially helpful when you write character dialogue or thoughts. Think about how certain characters would talk or think about things in real life. Write sentences that actually sound like those characters in terms of formality.[9]

- For instance, a farmer from the deep south in the USA probably wouldn’t say “she was quite mad when I showed up late.” The man would probably speak more informally and with slang. He might say something like “she was right ticked when I got home!”

Advertisement

-

Getting rid of unnecessary words keeps your writing clear and concise. Keep an eye out for wordy sentences and try to replace them with a fewer number of words that say the same thing. Some of the most highly regarded authors, like Hemingway, are known for using short, to-the-point sentences in their writing.[10]

- For example, instead of writing “I came to the conclusion that…” write “I concluded that…” By removing 3 words from that sentence, you get your point across to the reader faster and more clearly.

-

Describing things in other ways is more impactful than using clichés. If you write something that comes to mind immediately, but it sounds familiar, that might be a warning sign that it’s a cliché. If you catch yourself writing a phrase you’ve seen a lot in other writing, pause and think of a different way to say what you mean. Try to rewrite the phrase in a shorter, more original way.[11]

- For example, instead of saying “he was as dead as a door nail,” you could just say “he was dead” to get your point across without using a played-out cliché. Or, if you want to be more descriptive, say something like “he was as dead and as cold as a rock.”

- Another example of a cliché that appears in lots of writing is: “A single tear trickled down her cheek.”

Advertisement

-

It’s totally fine if you get stuck with a phrase you’re not happy with. Mark it in your draft and come back to revise it later on. Give your mind a rest and search for inspiration, then rewrite it when you have an alternative that you know is better.[12]

- In other words, don’t feel like you have to choose the best words all the time when you write the first draft of a story. That’s why it’s called a “rough” draft!

Add New Question

-

Question

I’m really awful at describing things. Any tips?

Silvana Haynes

Community Answer

There is a pattern for description, for example the method of » Simile+ adjectives, verb with adverb following- into the- adjectives, personification, «with» description and movement words. For example: Like a ball, the blubbery, sizeable tomato lunged swiftly into the lofty plumb tree that lay before it, it frantically darted across the field with its navy green stem as it hung tightly onto the iridescent meadow. If you want, you can search up synonyms for similar words.

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

About This Article

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 24,736 times.

Did this article help you?

Основа любого языка — лексика. Можно плохо знать грамматику, но если не знаешь слов, то не сможешь сказать ничего! Именно поэтому работа над пополнением словарного запаса занимает значительную часть времени в изучении языка. В продолжение нашей статьи об ошибках сегодня расскажем о проблемах начинающих учеников в использовании слов, а также предложим варианты их решения.

Поскольку именно лексических ошибок в речи начинающих (и не только) может быть бесконечное множество, решили поделить их по группам, приведя несколько типичных примеров для каждой.

Wrong Word Choice

Самая распространенная ошибка неносителей любого уровня, но особенно новичков — это неправильный выбор слов. Такая ошибка случается, когда ученики пытаются перевести слова с родного языка сами, используя словарь. К сожалению, не все сразу умеют различать виды слов, и не знают, какое именно значение выбрать, выбирая первое попавшееся в словаре .

Например, один из моих учеников должен был в качестве домашнего задания написать небольшой текст о характере человека и затем рассказать об этом на уроке, используя свои заметки. Ученик старался использовать как можно больше “сложных” слов, и подсмотрев в словаре слово “стеснительный”, он выбрал наиболее длинное (и, как ему показалось, сложное и красивое) слово “embarassing” вместо простого, короткого, но точного “shy”, просто потому, что это слово в словаре было первым. В итоге получилось: “I am embarrassing to talk to new people”.

Чтобы избежать такой проблемы необходимо для начала научить новичков пользоваться словарем (да, это отдельный навык!), смотреть не только на первое слово, но и на другие, и что самое главное — на примеры!

Literal Translation

Другая беда начинающих учеников — буквальный перевод фраз, слов и выражений, что приводит к появлению в английской речи русизмов (и других -измов), а также забавных ситуаций.

В преддверии праздников все без исключения мои ученики (от мала до велика, от A2 до C1) рассказывали мне, как они собираются “meet the New Year”, потому что мы же “встречаем Новый год”, так почему бы его не “meet” на английском. Проблема в том, что выражения в родном и английском языке в 90% случаев не совпадают, поэтому важно учить не просто слова, но и выражения, коллокации, words chunks, чтобы не делать таких ошибок в будущем.

Другие вариации на тему: мой испаноязычный студент говорил “I have 25 years” в ответ на “How old are you?”, потому что именно так в испанском отвечают на этот вопрос. И любимое всеми русскоязычными студентами (и даже моими школьными и университетскими преподавателями) “How do you think?” 😉

Prepositions

Пропуск предлогов во фразовых глаголах и verbs with dependent prepositions, а также подстановка неверного предлога (по аналогии с родным языком) — еще один бич всех начинающих и продолжающих студентов. Предлоги для меня лично вообще — самая сложная тема в любом языке, который я изучала (кроме английского). А все потому, что в каждом языке помимо прямого значения предлога учитывается еще и его использование с определенными словами и выражениями. В английском это фразовые глаголы и verbs with dependent prepositions.

Например, от учеников можно часто услышать “listen music” без “to” (ошибка в предлоге с verbs with dependent prepositions), “on the picture” вместо “in the picture” (подстановка неверного предлога по аналогии с родным языком). Иногда ученики пропускают нужный предлог в устойчивых выражениях, которые они где-то услышали, но запомнили не до конца, например, ученица мне рассказывала о Праге и описала свои впечатления так: “I fell in love the place”, пропустив важную часть выражения в виде предлога “with”.

Misspelling

В письменной речи часто страдает правописание, а именно, ученики пишут одно слово, имея в виду другое, или просто делают ошибки в написании. Пример первой проблемы: ученики путают на письме “than” и “then”, “its” и “it’s”, “witch” и “which”, “where” и “were” и т.д., потому что для них эти слова звучат одинаково (что в случае с “witch” и “which” действительно так). Решить эту проблему можно, работая над произношением и письмом. В современном мире (особенно в онлайн обучении) правописанию уделяется мало времени, даже носители языка делают ошибки. Тем не менее, если ученикам необходима будет в дальнейшем переписка на английском языке, в их же интересах сразу учиться писать грамотно. Проводите словарные диктанты (короткие, в начале урока), просите учеников записывать свои мысли (вести краткий дневник), заметки. Это поможет им запомнить написание повторяющихся слов и избежать глупых орфографических ошибок.

Redundancy

Помимо пропуска важных элементов выражений, некоторые учащиеся пытаются добавить что-то, часто лишнее, по аналогии с родным языком. Например, наверное, это боль всех преподавателей, когда студент говорит “I feel myself well”. Конкретно с этой проблемой бороться сравнительно легко. Как только ученики понимают, что они сейчас сказали, им сразу становиться стыдно, и через чувство (стыд) запоминается правильный вариант. С другими выражениями, типа “I want to take a look on/to” и др., работаем также, как и с пропуском таких важных слов — учим слова не в изоляции, а в контексте, учим полные выражения, word chunks.

False Friends

Ложные друзья переводчика также проблема, происходящая из-за любви к переводу всего и вся. Ученики пытаются использовать слова “accurate” в значении “аккуратный”, “biscuit” в значении “бисквит”, “salute” в значении “фейерверк”, “intelligent” в значении “интеллигентный” и т.д. Другая сторона медали — использование слова лишь в одном из его значений и непонимание других. Например, “diet” в английском языке не только диета, но и рацион, т.е. То, чем человек в принципе питается. Ученики воспринимают его только как “диета”, поэтому на вопрос: “Let’s talk about your diet. What do you eat?”, — отвечают: “I don’t have a diet”, что довольно забавно.

Выйти из этой ситуации можно, объяснив ученикам, что далеко не все слова, которые одинаково звучат, означают то же самое в английском и их родном языке.

Collocation and idiom breaker

Когда ученики на начальном уровне и еще не знают полных коллокаций и идиом, но пытаются их использовать, получается коверканье идиомы или устойчивого выражения. Причина — дословный перевод, упущение некоторые слов, использование не тех слов, что нужно. В итоге получаем, “on another hand”, “love from the first sight”, “make homework”, “do mistakes” и т.д. Бороться с этим нужно в первую очередь, объяснив студентам, что не стоит сначала усложнять речь выражениями, в которых они не уверены. При этом важно обучать их не просто словам, но и интересным выражениям, фразам и идиомам (самым простым) уже с самого начала. Обращайте особое внимание на то, что в них нельзя менять слова на другие, похожие, иначе получится ерунда.

Word Formation

Особо смелые студенты, не зная правил словообразования, пытаются их придумать сами, что приводит к различным перлам в стиле: “different thinks and ideas” (существительное от глагола “to think”), “Japan food” (использование существительного вместо прилагательного, которого студент не знает) и т.д.

Чтобы это предотвратить важно при введении новой лексики иногда давать студенту еще и однокоренные слова, представляющие другие части речи, особенно для самых распространенных слов. Это не только поможет им не делать такие ошибки, но и быстрее будет развивать их словарный запас.

Wrong register

Еще одной проблемой, часто пренебрегаемой, является использование слов неформальных в формальных ситуациях и наоборот. Однажды мой студент в небольшом сочинении написал, что у него болел “tummy”, поскольку это слово он знал, а вот слово “stomach” казалось ему слишком научным. Проблема в том, что сочинение в английском языке — формальный стиль, а потому просторечия или “детские” слова типа “tummy” в нем использовать нельзя.

Для работы над этой ошибкой важно обозначать для студентов степень формальности слова на этапе его первого введения.

Inappropriate synonyms

Мы говорим студентам, что необходимо разнообразить речь, особенно на письме, используя синонимы. Ученики рады стараться, тщательно их ищут в словарях, пишут или запоминают и потом используют в речи, но почему-то не всегда попадают в точку. Почему? Дело в том, что как и в других языках, в английском синонимы не всегда полностью совпадают по значению — это еще и близкие по значению слова. Часто бывает, что близкие по значению слова оказываются из разного register, не используются в каких-то ситуациях и т.д.

Например, “handsome” и “beautiful” вроде бы синонимы, но используются по-разному, причем, сказать “a handsome woman” можно, но значение такой фразы будет совсем другое. Важно научить студентов различать эти смыслы, проверять по примерам в словаре, когда что использовать, и при введении новой лексики оговаривать эти нюансы.

Какие бы ошибки в использовании слов и выражений ни делали студенты, решение всех проблем одно — изучать лексику в контексте, вводить не только слова, но и word chunks, обращать внимание не только на значение слова, но и на произношение, написание, register, форму, синонимы, однокоренные слова и т.д.

А как вы работаете с такими ошибками? Какие лексические ошибки наиболее часто встречаются у ваших учеников?

Ждем ваших историй и идей в комментариях!

Sometimes you can tell a person’s opinion on a certain subject, item, idea, or even another individual — not by what they say, but by how they say it. The words a speaker or writer uses to describe and communicate something to others, their word choice or diction, shows their attitude or tone. Although you may not know it, the way you describe something often tells others additional information about what you think.

Many orators, writers, and master communicators have learned to choose their words carefully when communicating an idea to be as effective as possible with their message. Word choice, also known as diction, is important to help communicate the right tone and influence your audience.

Tone and Word Choice Meaning

Tone and word choice, or diction, are specific style choices writers use when composing a piece to convey their message effectively.

The tone is the author’s attitude towards the subject or even a character within a novel.

Word choice, or diction, refers to the author’s specific words, imagery, and figurative language to communicate that tone.

The specific word choices an author employs directly affect and reveal the tone.

To select the right words, authors must pay close attention to both the denotation and connotation of words.

Denotation is the literal dictionary definition of a word.

Connotation is the underlying meaning of a word or the emotional charge it carries. Connotation can be negative, positive, or neutral.

Several words can have the same denotative meaning yet carry a different connotative meaning. The connotation of a word can vary from culture to culture and based on life experiences.

Carefully chosen diction can help writers effectively communicate an idea or perspective and develop a unique voice and style. Word choice enables authentic communication and ensures the tone and message of a piece are aligned or in agreement.Carefully selected diction is crucial when defining the purpose of your writing. It is often appropriate to use detailed descriptions, figurative language, and imagery for narrative, prose, and poetry. However, if you are writing a research paper for biology, your language will be more scientific and the diction more direct and factual.

Tone and mood are often confused. While they are related, they differ in one central aspect. Tone is the author’s attitude toward a subject, idea, situation, or character, while mood is the audience’s or reader’s emotional response. The tone of a piece can be humorous, while the mood is lighthearted and fun. An author may use description to show their dislike toward a character, while the readers may relate to the character and feel empathy.

The Reason for Careful Word Choice

Carefully chosen diction is essential in writing. The types of words an author or orator decides to use depends on the purpose of their writing or speech. Carefully selected words, phrases, and descriptions can do a lot.

Word Choice Matches Your Tone and Purpose

An informative text, such as a non-fiction research article, will have more professional, content-specific, and technical diction because its purpose is to inform a specific audience. A literary fiction piece will have more detailed language, figures of speech, imagery, and conversational language because one of the primary purposes of fiction is to entice a reader, engage with the audience, and entertain.

Word Choice Creates the Right Setting

The language authors use when developing a story to describe characters, time, and place must be in agreement for readers to accept the story as realistic. Authors often use strong descriptive words to help establish the setting, create a mood, and give an authentic feeling to the story.

Word Choice Develops a Narrative Voice

A consistent narrative voice helps readers connect to the piece of writing and establishes a trustworthy relationship between reader and narrator.

Word Choice Creates Better Characters

Authors and orators often use language specific to a particular region, dialect, and accents to provide a realistic portrayal of a character or relate to the audience. Presenters who are not from Texas may use typical Texas colloquialisms, such as «y’all,» which is a combination of the words «you» and «all,» to relate to the listeners. A young character in a fiction piece may speak with a lot of slang or foul language to show immaturity. A character’s use of specific diction can indicate their gender, level of education, occupation, upbringing, or even social class.

A colloquialism is an informal word or phrase often used in daily conversation. Some colloquialisms may be specific to a region, culture, or religion.

Tone and Word Choice Examples

Some descriptive words have the same denotative meaning but carry different connotations. Using careful word choice, especially when selecting the proper synonym or a descriptive adjective, can create the desired effect and convey the appropriate tone for a piece. Consider the following table of examples.

| Word (with neutral connotation) | Denotation | Synonym with a positive connotation | Synonym with a negative connotation |

| Thin | having little flesh or fat | Slender | Skinny |

| Overweight | above a weight considered normal or desirable | Thick | Fat |

| Strict | demanding that rules are followed or obeyed | Firm | Austere |

Have you noticed a difference in someone’s tone when they call someone slender vs when they call someone skinny?

Impact of Word Choice on Meaning and Tone

Selecting words with a positive connotation will reflect a more amiable tone toward the subject, while words with a negative connotation will convey a negative attitude toward a subject. Words with a neutral connotation are best used when an author does not want to reveal their attitude or, in instances, such as a scientific paper, where only the facts are important.

Difference Between Tone and Word Choice

Word choice and tone are related. Word choice refers to the language specifically chosen by the author or orator to help convey their attitude regarding a notion, story, or setting. Word choice shapes the tone. On the other hand, the desired tone an author seeks dictates the words they use. If the author wants to establish a worried tone, some key diction and phrases within the piece might be words like «tentatively,» «shaking,» «stressed,» «nervous,» «sweaty,» «eyes darting,» and «looking over his shoulder.» To portray a more optimistic tone, an author might select words like «eagerly,» «excitedly,» «hopeful,» «reassuring,» and «anticipated.» Keyword choice is the foundation that builds a consistent tone.

The Four Components of Tone

Whether an article is a non-fiction piece, a fictive story, a poem, or an informative article, the tone the writer uses helps audience members have the appropriate reaction to the information by creating the mood. There are four basic components of tone, and diction dictates the balance of emotions. Authors aim to maintain the same tone throughout a piece to convey a consistent message. The four components of tone range from:

- Funny to serious

- Casual to formal

- Irreverent to respectful

- Enthusiastic to matter-of-fact (direct)

Writers choose the voice they want to deliver and then focus on specific word choices to maintain their tone. Pieces that move too often between distinct tones can be hard for readers to follow and cause confusion.

Types of Tones

The tone in writing indicates a particular attitude. Here are some types of tones with examples from the literature and speeches.

The diction that helps to convey the tone is highlighted.

When I pulled the trigger I did not hear the bang or feel the kick—one never does when a shot goes home—but I heard the devilish roar of glee that went up from the crowd. In that instant, in too short a time, one would have thought, even for the bullet to get there, a mysterious, terrible change had come over the elephant. He neither stirred nor fell, but every line of his body had altered. He looked suddenly stricken, shrunken, immensely old, as though the frightful impact of the bullet had paralyzed him without knocking him down.1

In this excerpt from Orwell’s essay, «Shooting an Elephant,» the gruesome tone is communicated through Orwell’s descriptive word choice. The words «terrible,» «suddenly stricken,» and «paralyzed» describe the horrific reaction the elephant has when the first bullet hits.

Inside the house lived a malevolent phantom. People said he existed, but Jem and I had never seen him. People said he went out at night when the moon was down, and peeped in windows. When people’s azaleas froze in a cold snap, it was because he had breathed on them. Any stealthy small crimes committed in Maycomb were his work. Once the town was terrorized by a series of morbid nocturnal events: people’s chickens and household pets were found mutilated; although the culprit was Crazy Addie, who eventually drowned himself in Barker’s Eddy, people still looked at the Radley Place, unwilling to discard their initial suspicions.2

In this excerpt from Chapter 1 of To Kill a Mockingbird, descriptive words help to create a foreboding tone. Words like «morbid,» «mutilated,» «terrorized,» and «malevolent phantom» reveal Scout’s sense of fear and apprehension.

Hope» is the thing with feathers —

That perches in the soul —

And sings the tune without the words —

And never stops — at all —

And sweetest — in the Gale — is heard —

And sore must be the storm —

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm —

I’ve heard it in the chillest land —

And on the strangest Sea —

Yet — never — in Extremity,

It asked a crumb — of me.3

In this poem by Emily Dickinson, the cheerful tone is communicated through the words «perches,» «sings,» and «sweetest.»

Tone and Word Choice — Key Takeaways

- Word choice refers to the specific language, words, phrases, descriptions, and figures of speech authors choose to create a desired effect.

- Tone is the author’s attitude toward a subject as conveyed by their word choice in a given piece.

- Denotation is the dictionary definition of a word and connotation is the underlying meaning of a word and its emotional charge.

- Connotation is the underlying meaning of a word or the emotional charge it carries. Connotation can be negative, positive, or neutral.

- The four components of tone are, funny to serious, casual to formal, irreverent to respectful, and enthusiastic to matter-of-fact.

1 George Orwell. «Shooting an Elephant.» 1936.

2 Lee Harper. To Kill a Mockingbird. 1960.

3 Emily Dickinson. ‘»Hope» is the thing with feathers.’ 1891.

Перевод по словам

— word [noun]

noun: слово, речь, текст, известие, обещание, замечание, пароль, разговор, девиз, лозунг

verb: вести, сформулировать, выражать словами, подбирать выражения

- a good word — хорошее слово

- many a true word is spoken in jest — в каждой шутке есть доля правды

- arrowy word — колкое словечко

- hardly understand word — с трудом понимают слово

- no word — Нет слов

- may i have a word with you — могу я поговорить с вами

- insert after the word — вставить после слова

- not utter a word — не проронил ни слова

- his word against — его слово против

- language the word — язык слово

— choice [adjective]

noun: выбор, отбор, альтернатива, избранник, пункт меню, избранница, нечто отборное

adjective: отборный, лучший, разборчивый, осторожный

- choice of profession — выбор профессии

- loads of choice — большой выбор

- there is large choice — есть большой выбор

- clear choice — Очевидный выбор

- a person of their choice — человек по своему выбору

- choice of law principles — выбор принципов права

- was the first choice — был первым выбором

- not your choice — не ваш выбор

- tool of choice — Инструмент выбора

- act of choice — акт выбора

Предложения с «word choice»

|

I just, um… helped him with punctuation and word choice and stuff like that. |

Я просто помогал ему с пунктуацией, подбором слов и всем таким. |

|

Perhaps my word choice was a little… treacherous. |

Возможно, мой подбор слов был несколько… коварен. |

|

And diabolical would not be an inappropriate word choice for her. |

Её даже злобной будет неуместно назвать. |

|

Even text communication can have patterns of grammar or word choice, known to the agent and his original service, that can hide a warning of capture. |

Даже текстовая коммуникация может иметь шаблоны грамматики или выбора слов, известные агенту и его первоначальной службе, которые могут скрывать предупреждение о захвате. |

|

The quoted article by Reinhart Hummel is not well translated, the word choice is poor and slanted, the last paragraph makes little sense. |

Цитируемая статья Райнхарта Хаммеля не очень хорошо переведена, выбор слов скуден и скошен, последний абзац имеет мало смысла. |

|

This includes vocal tone/volume, word choice, etc. |

Это включает в себя вокальный тон/громкость, выбор слов и т. д. |

|

Regardless of what the meaning of the sentence is, the word choice just doesn’t fit. |

Независимо от того, что означает предложение, выбор слова просто не подходит. |

|

Brown’s prose style has been criticized as clumsy, with The Da Vinci Code being described as ‘committing style and word choice blunders in almost every paragraph’. |

Стиль прозы Брауна критиковали как неуклюжий, а Код Да Винчи описывали как совершающий ошибки стиля и выбора слов почти в каждом абзаце. |

|

Maybe a better word choice might be in order. |

Может быть, более удачный выбор слов был бы уместен. |

|

The word choice represents a shift from Keats’s early reliance on Latinate polysyllabic words to shorter, Germanic words. |

Выбор слов представляет собой сдвиг от ранней опоры Китса на латинские многосложные слова к более коротким, германским словам . |

|

Click on a word is used to measure knowledge of vocabulary; in the paper-based test this language skill is examined by the multiple choice questions. |

Тип вопроса click on a word может использоваться для проверки знания лексики; в письменном варианте TOEFL данный языковой навык проверялся с помощью вопросов multiple choice. |

|

Maybe caveman wasn’t the right choice of word (! |

Возможно, я не так выразилась, когда говорила о пещерных людях. |

|

If you have to ask why a 12-time Teen Choice Award nominee is a celebrity judge, then you don’t really understand what the word celebrity means. |

Если ты спрашиваешь, почему 12 — кратная номинантка Teen Choice Award стала звездной судьей, значит, ты не понимаешь смысл слова звезда. |

|

And word of advice, it’s always lady’s choice. |

И дам совет, право выбора всегда за леди. |

|

Have your boys put the word out on the street that you found me. Dominic will have no choice but to reach out to make a deal. |

Если вы пустите слух, что нашли меня, у Доминика не останется вариантов, кроме как пойти на сделку. |

|

But the Hebrew word, the word timshel-‘Thou mayest’-that gives a choice. |

Но древнееврейское слово тимшел — можешь господствовать — дает человеку выбор . |

|

Yeah, society may have neglected him, yes, but it didn’t force him to do meth. That was a choice, and I’m sorry, but when you use the word victim, I think of Mariana. |

Да, общество, может, и пренебрегло им, да, но оно не заставляло его принимать наркотики это был выбор , и, я прошу прощения, но когда вы говорите слово жертва, я думаю о Мариане, |

|

It is the word of choice by the Chinese Communist Party, used to hide the persecution. |

Это слово было выбрано Коммунистической партией Китая, чтобы скрыть преследование. |

|

Lorenz’s explanation for his choice of the English word Mobbing was omitted in the English translation by Marjorie Kerr Wilson. |

Объяснение Лоренца по поводу его выбора английского слова моббинг было опущено в английском переводе Марджори Керр Уилсон. |

|

That means that most suffixes have two or three different forms, and the choice between them depends on the vowels of the head word. |

Это означает, что большинство суффиксов имеют две или три различные формы, и выбор между ними зависит от гласных главного слова . |

|

The Law Society found the use of the word, though an extremely poor choice, did not rise to the level of professional misconduct. |

Правовое общество сочло, что использование этого слова , хотя и было крайне неудачным выбором , не поднялось до уровня профессионального проступка. |

|

In it, I saw neither the word ‘unconscionable’, nor any reference to Cho; hence my choice of wording. |

В нем я не увидел ни слова бессовестный, ни какой — либо ссылки на Чо; отсюда и мой выбор формулировки. |

When writing academically, the most precise choice is most often the right one. When two words can convey the same idea, the shortest and clearest option is usually the wisest.

The process of choosing what to write involves a lot of consideration. Writing a paper requires choosing a topic, selecting a method, selecting resources, and setting up the main idea; then, when it’s time to write, selecting the words and structuring them.

Choosing the right words seems obvious, but selecting the right words will change your writing tone and content. There are several approaches to consciously choosing words, and we will explore them in this article.

Why is it important to choose the right words when writing?

There are two types of meanings for words: denotative and connotative. Definition and usage are referred to as denotation. Associating, connecting, and using words are described by their connotations. When it comes to using words in academia, these factors can be very important.

When writing a publication, using the right words is essential to its effectiveness. It is imperative to make choices when writing academically, just as when writing in other forms. The phrase, sentence, or even paragraph that most accurately conveys your argument is the first thing you should choose when you’re writing.

Readers are more likely to understand a concept when the word choice is meaningful or striking. The purpose of it is to provide clarity, convey, and enhance concepts. There are several factors that can limit an author’s ability to convey accurate information through their word choice.

Use the right words and the right images together to boost your paper’s potential

Using the right images is just as important as the right words. Beautiful designs and scientifically accurate images can also be decisive when it comes to publishing a successful science paper. Try using Mind the Graph to easily create your visuals and take your work to another level.

The best ways to avoid making mistakes with your word choice

Your reader will have difficulty understanding what you meant when you use misused words or grammar structures. If there is “ambiguity”, “vagueness” or “Unclarity” in these words, they may be ineffective. Writers know what they intend to say, but readers know only what they actually said. Therefore, it is very important to avoid making such mistakes.

Your word choice should always be based on your audience’s understanding. Thus, it is unsuitable to use slang, geographical terms, endearments, and jargon in academic writing. Avoid any phrase that is uncertain about the audience’s understanding.

When proofreading your work, keep your readers’ perspective in mind. Matching the terminology of your subject matter is also important. Clarity and concision are only part of establishing your credibility as an author.

Words can often obscure your meaning if you use too many. A larger amount of material to read and analyze makes it more difficult to read and understand your writing. If your writing has extra words, try to eliminate them.

Keep your tone positive without sounding overly assertive. If you want to brainstorm while you write, you can use the slash/option technique. If you’re stuck on a word or a sentence, write out two or more alternatives. Getting a sense of the right tone of wording for your paper is best done by writing it in at least two ways.

Word choice examples and guide

Jargon

Jargon is an unintuitive, sometimes deliberate way of confusing words or expressions in order to influence a reader’s interpretation. Example: Patients suffered from high fevers and many side effects due to diseases, which they could not handle. (too many words describing the same idea when it could just be a simple sentence,” The disease caused severe symptoms in patients.)

Clichés

When a phrase becomes so common that its meaning is lost, it is called a cliché. A very typical example is “the grass is always greener on the other side” or “last but not least”, do not use it in academic writing.

Big Words

Using big words might sound fancy, but they don’t add meaning rather lead to an inability to comprehend a subject.

Generally used adjectives and adverbs

Appropriate adjectives and adverbs hold quantifiable meanings. Therefore, it is best to use words that describe the context and are accurate.

Wordiness

If your text is too wordy, the reader has to skim through more text to find the main implications of the paper.

Bring words to life with the power of visual

Exactly, we have many templates for every type of science visual communication. Save time by working smarter. The illustrations we offer can be customized to meet your specific needs, and we have a wide range of categories to choose from. With Mind the Graph, science communication is easier than ever before.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual

communication in science.

— Exclusive Guide

— Design tips

— Scientific news and trends

— Tutorials and templates

Precision

A very important part of word choice is precision.

Through precise word selection, you can increase the clarity of your argument by enabling your readers to grasp your intended meaning quickly and accurately. At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that your word choices affect a reader’s attitudes toward your presentation and your subject matter. Therefore, you also need to choose words that will convey your ideas clearly to your readers. This kind of precise writing will help your audience understand your argument.

Regardless of the words you use, you must use them accurately. Usage errors can distract readers from your argument.

How can you ensure that words are used accurately?

Unfortunately, there is no easy way, but there are some solutions. You can revisit a text that uses the word and observe how the word is used in that instance. Additionally, you can consult a dictionary whenever you are uncertain. Be especially careful when using words that are not yet part of your usual vocabulary.

General vs. Specific Words

You can increase the clarity of your writing by using concrete, specific words rather than abstract, general ones.

Almost anything can be described either in general words or in specific ones.

General words and specific words are not opposites. General words cover a broader spectrum with a single word than specific words. Specific words narrow the scope of your writing by providing more details. For example, “car” is a general term that could be made more specific by writing “Honda Accord.”

Specific words are a subset of general words. You can increase the clarity of your writing by choosing specific words over general words. Specific words help your readers understand precisely what you mean in your writing. Here’s an example of general and specific words in a sentence:

- General: She said, “I don’t want you to go.”

- Specific: She murmured, “I don’t want you to go.”

The words “said” and “murmured” are similar. They both are a form of verbal communication. However, “murmured” gives the sentence a different feeling from “said.” Thus, as a writer, choosing specific words over general words can add description to and change the mood of your writing.

(Caveat: When writing fiction, avoid the temptation to frequently alter the dialogue tag «said.» Doing so can be distracting for readers. The tag, «said,» is so common it almost becomes invisible, letting readers keep their focus where it should be—on the actual dialogue.)

Using the Dictionary and Thesaurus Effectively

Always use a dictionary to confirm the meaning of any word about which you are unsure. Although the built-in dictionary that comes with your word processor is a great time-saver, it falls far short of college-edition dictionaries, or the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). If the spell-check tool suggests bizarre corrections for one of your words, it could be that you know a word it does not. When in doubt, always check a dictionary to be sure.

Vocabulary Choice and Style

It’s important to vary word choice. If it feels like you keep repeating a word throughout your writing, pull out a thesaurus for ideas on different, more creative choices. A thesaurus can add some color and depth to a piece that may otherwise seem repetitive and mundane. However, make sure that the word you substitute has the meaning you intend to convey.

Thesauruses provide words with similar meanings, not identical meanings. If you are unsure about the precise meaning of a replacement word, look up the new word in a dictionary.

Connotation

Connotation is the extended or suggested meaning of a word beyond its literal meaning. For example, “flatfoot” and “police detective” are often thought to be synonyms, but they connote very different things: “flatfoot” suggests a plodding, perhaps not very bright cop, while “police detective” suggests an intelligent professional.

Verbs, too, have connotations. For instance, to “suggest” that someone has overlooked a key fact is not the same as to “insinuate” it. To “devote” your time to working on a client’s project is not the same as to “spend” your time on it. The connotations of your words can shape your audience ‘s perception of your argument.

Register

“Register” refers to a word’s association with certain situations or contexts. In a restaurant ad, for example, we might expect to see the claim that it offers “amazingly delicious food.” However, we would not expect to see a research company boast in a proposal for a government contract that it is capable of conducting “amazingly good studies.” Here, the word “amazingly” is in the register of consumer advertising, but not in the register of research proposals.

Being aware of the connotation and register of your word choice will help increase your writing’s clarity.