As reading interventionists, we can quickly tell by our students’ efforts what the significant adults in our young readers’ lives have been emphasizing. One student might try so hard to sound out every word that it sounds like he or she is spitting out word parts that do not sound like any words we have ever heard. Another student might study the pictures for clues and completely invent a story to go along with the pictures, without paying any attention to the groups of letters on the page. Of course, these are examples at each end of the spectrum, but believe us when we tell you that we have seen many students with each of these reading profiles year after year. Many parents of beginning readers are so focused on getting their child to read the words in the book that they tend to forget to discuss what’s happening in the book! Until we can teach beginning readers more effective and efficient strategies, these students will continue to struggle learning to read.

Students have to learn how words work and they have to think about what they are reading, but reading for meaning is far more important than reading every single word accurately. It is perfectly fine if a reader misreads a word here and there as long as it makes sense and sounds right. For example, a student might read: The dog jumps over the fence instead of The dog jumped over the gate. The child used some visual information and the child was reading for meaning. The child’s reading made sense and sounded right. The child used one-to-one matching, meaning that the number of words read matched the number of words in the text. This is developmentally appropriate for a beginning reader. Even adults who are reading at a fast pace will misread words from time to time. Sit and listen to a friend read a passage. Notice that he or she may insert the word in or omit the word the, however those errors don’t change the meaning. This is completely normal.

What an adult says about the student’s efforts will influence the strategies the student will choose to use in the future. If an adult focuses on accuracy instead of meaning and corrects jumps/jumped and fence/gate without praising the child’s reading for making sense, the child will believe that reading each word correctly is more important than reading for meaning. The child might slow down and try to sound out every word without thinking about what would make sense. This would be a sad mistake because the child was actually using more effective strategies before the adult corrected him or her.

Interact with your child when he or she is reading, and it will be so fun for your child. Make comments about the characters. Ask questions! Laugh at the funny parts. Talk about the story with your child. The proliferation of book clubs for adults is an indication that literate people love to talk about what they are reading or have read. Beginning readers like to do this, too! Ask your child to show you his or her favorite parts by going back into the story. Children need to learn to look back in the story to find the evidence to support their responses. Searching for information (or looking back in the story) is a great strategy! Do not discourage this behavior.

You may find the following questions useful when you start a book discussion with your child:

What was your favorite part of the story? Why?

Which character(s) did you like best? Why?

What do you think will happen next?

What kind of person/animal is ____________ (character name)?

Does this story remind you of another book you’ve read?

Does this story remind you of something in your life?

What did you learn from this story?

Did you like the ending of the story?

What do you think _______ will do next?

Why did _____ do ________? Was this a good idea?

Would you have done anything differently?

Is this a real or an imaginary story?

Note: This list is not all inclusive. The possibilities are endless. Feel free to add questions of your own. This list of questions is not meant to be a test. We are providing some questions that could be used with most stories to foster a good book discussion.

Comprehension is the essence of reading. Without it, a child is just simply calling out words. The next time you are sitting with your child and listening to him or her read, be an active participant. Enjoy the book together and really have your child think about what he or she is reading. Reading is such a complex process. Your child is juggling so many balls in the air! Just remember how important it is to focus on his or her comprehension. Stay tuned and continue reading our blog to find out what common errors children make when reading.

Turaeva G. Kh.,

Uzbekistan

Instructors want to produce students who, even if they do not have complete control of the grammar or an extensive lexicon, can fend for themselves in communication situations. In the case of reading, this means producing students who can use reading strategies to maximize their comprehension of text and identify relevant and non-relevant information.

The Reading Process

To accomplish this goal, instructors focus on the process of reading rather than on its product.

· They allow students to practice the full repertoire of reading strategies by using authentic reading tasks. They encourage students to read to learn (and have an authentic purpose for reading) by giving students some choice of reading material.

· When working with reading tasks in class, they show students the strategies that will work best for the reading purpose and the type of text. They explain how and why students should use the strategies.

· They encourage students to evaluate their comprehension and self-report their use of strategies. They build comprehension checks into in-class and out-of-class reading assignments, and periodically review how and when to use particular strategies.

· They explicitly mention how a particular strategy can be used in a different type of reading task or with another skill. [ 1]

By raising students’ awareness of reading as a skill that requires active engagement, and by explicitly teaching reading strategies, instructors help students develop both the ability and the confidence to handle communication situations they may encounter beyond the classroom.

Reading Comprehension Strategies

Instruction in reading comprehension strategies is not an add-on, but rather an integral part of the use of reading activities in the classroom. Instructors can help their students become effective readers by teaching them how to use strategies before, during, and after reading.

Before reading: Plan for the reading task

· Set a purpose or decide in advance what to read for

· Decide if more linguistic or background knowledge is needed

During and after reading: Monitor comprehension

· Decide what is and is not important to understand

· Reread to check comprehension

After reading: Evaluate comprehension and strategy use

· Evaluate overall progress in reading and in particular types of reading tasks

· Decide if the strategies were appropriate for the purpose and for the task

Using Authentic Materials and Approaches

To develop communicative competence in reading, classroom and homework activities must resemble ( be) real-life reading tasks that involve meaningful communication. They must therefore be authentic in three ways.

1. The reading material must be authentic: It must be the kind of material that students will need and want to be able to read when studying abroad, or using the language in other contexts outside the classroom.

When selecting texts for student assignments, remember that the difficulty of a reading text is less a function of the language, and more a function of the conceptual difficulty and the task(s) that students are expected to complete.

2. The reading purpose must be authentic: Students must be reading for reasons that make sense and have relevance to them. “Because the teacher assigned it” is not an authentic reason for reading a text.

Ask students how they plan to use the language they and what topics they are interested in reading and learning about. Give opportunities to choose assignments, and encourage them to use the library, the Internet to find other things they would like to read.

3. The reading approach must be authentic: Students should read the text in a way that matches the reading purpose, the type of text, and the way people normally read. This means that reading aloud will take place only outside the classroom, such as reading for pleasure. The majority of students’ reading should be done silently.

Students whose language skills are limited are not able to process at this level, and end up having to drop one or more of the elements. Usually the dropped element is comprehension, and reading aloud becomes word calling: simply pronouncing a series of words without regard for the meaning . [2]

Studies show that when students read they improve not only their reading fluency, but they also build new vocabulary knowledge and expand their outlook also. Reading can help students write better, improve listening and speaking skills and develop positive attitudes toward reading in English.

REFERENCES:

- Alderson J.C. & Urquhart A.H. Reading in a foreign language. London: Longman, 1984.

- Breen, M.P. Authenticity in the language classroom Applied Linguistics,1985.

Review

I am so grateful to Kelly for bringing together so much important research and communicating it so effectively. Kelly puts readers of this book on the cutting edge of reading comprehension instruction for a significant and under-served population of students. Thank you, Kelly, and thank you to everyone who reads this book and works to bring all readers to deep comprehension. —Nell K. Duke Michigan State University

About the Author

«My hope in writing Word Callers,» writes Kelly Cartwright,» is to share insights into what makes word callers tick, as well as effective interventions that can help these children learn to enjoy the rich meaningful world of reading that they are missing.» Her research has long focused on the importance of flexible thinking for skilled comprehension, and her word-and-picture card assessment and intervention developed as she observed that some students could read fluently but had surprising difficulty focusing on meaning. Kelly is an expert on reading comprehension, children’s (and adults’) thinking, and the development of literacy processes. Currently she is Professor of Psychology, Neuroscience, and Teacher Preparation at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia, where she serves as Chair of the Department of Psychology. Kelly is editor of Literacy Processes: Cognitive Flexibility in Learning and Teaching, which was nominated for the Ed Fry book award in 2008, and she has published articles in journals such as The Reading Teacher, the Journal of Educational Psychology, the Journal of Literacy Research, the Journal of Child Language, Early Education and Development, and the Journal of Cognition and Development. Kelly consults regularly with teachers and reading specialists in public and private schools around the country and is passionate about helping teachers discover the source of word callers’ difficulties so that they can better differentiate instruction for children who struggle with reading comprehension. Kelly’s work with word callers has struck a chord with reading teachers such as Sarah Sullivan from Gilberts, Illinois, who «consider it a much needed break-through in literacy pertaining to our collective need for a way to tap into reading comprehension via assessment and instruction.» Another teacher writes, «I have read many books in my ten years as an educator about trying to reach these students, but NOTHING I have ever read was as well-written and simple to follow as this book. It should be required reading for every intermediate teacher.» When she is not learning and teaching about reading and thinking, Kelly is actively involved in service to the broader reading community. Kelly serves the Virginia State Reading Association as President of Virginia College Reading Educators and as University Liaison to the Newport News Reading Council. She is a member of the editorial review boards of the Journal of Literacy Research and the Literacy Research Association Yearbook. In her home state, she served on the Higher Education Review Panel for the latest revision of the Virginia Standards of Learning in K-12 English Language Arts and Reading. Most recently Kelly consulted with the Virginia General Assembly’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, which studied statewide reading performance in third grade. Their final report cited Word Callers as an excellent resource for meeting the needs of high-fluency/low-comprehrension readers. Kelly has served in national roles as Area Co-Chair for Elementary and Early Literacy Processes for the Literacy Research Association and as a member of the International Reading Association Professional Standards and Ethics Committee. Kelly is a member of the American Psychological Association Division 15 — Educational Psychology; the American Educational Research Association, Division C — Learning and Instruction; the Cognitive Development Society; the International Mind, Brain, and Education Society; the International Reading Association; the Literacy Research Association; the Society for Research in Child Development; and she is a voting member of the Society for the Scientific Study of Reading. In her local community, Kelly has worked with colleagues in the public schools to establish Literacy Partners, a tutoring program for struggling elementary readers (Cartwright, Savage, Morgan, & Nichols, 2009). She is currently working with university and K-12 colleagues to develop a Literacy Collaborative at a local elementary school: a partnership dedicated to sustained excellence in literacy learning and instruction. Kelly lives in Yorktown, Virginia, with three rescue dogs and enjoys reading, writing, and walking with her canine companions. For more information on, visit kellycartwright.com.

Nell K. Duke, Ed.D., is a professor in literacy, language, and culture and also in the combined program in education and psychology at the University of Michigan. Duke received her Bachelor’s degree from Swarthmore College and her Masters and Doctoral degrees from Harvard University. Duke’s work focuses on early literacy development, particularly among children living in economic poverty. Her specific areas of expertise include the development of informational reading and writing in young children, comprehension development and instruction in early schooling, and issues of equity in literacy education. She has served as Co-Principal Investigator of projects funded by the Institute of Education Sciences, the National Science Foundation, the Spencer Foundation, and the George Lucas Educational Foundation, among other organizations. Duke has been named one of the most influential education scholars in the U.S. in EdWeek. In 2014, Duke was awarded the P. David Pearson Scholarly Influence Award from the Literacy Research Association, and in 2018 she received the International Literacy Association’s William S. Gray Citation of Merit for outstanding contributions to research, theory, practice, and policy. She has also received the Michigan Reading Association Advocacy Award, the American Educational Research Association Early Career Award, the Literacy Research Association Early Career Achievement Award, the International Reading Association Dina Feitelson Research Award, the National Council of Teachers of English Promising Researcher Award, and the International Reading Association Outstanding Dissertation Award. Duke is author and co-author of numerous journal articles and book chapters. Her most recent book is Inside Information: Developing Powerful Readers and Writers of Informational Text through Project-based Instruction. She is co-author of the books Reading and Writing Informational Text in the Primary Grades: Research-Based Practices; Literacy and the Youngest Learner: Best Practices for Educators of Children from Birth to Five; Beyond Bedtime Stories: A Parent’s Guide to Promoting Reading, Writing, and Other Literacy Skills From Birth to 5, now in its second edition; and Reading and Writing Genre with Purpose in K — 8 Classrooms. She is co-editor of the Handbook of Effective Literacy Instruction: Research-based Practice K to 8 and Literacy Research Methodologies. She is also editor of The Research-Informed Classroom book series and co-editor of the Not This, But That book series. Duke has taught preservice, inservice and doctoral courses in literacy education, speaks and consults widely on literacy education, and is an active member of several literacy-related organizations. Among other roles, she currently serves as advisor for the Public Broadcasting Service/Corporation for Public Broadcasting Ready to Learn initiative, an expert for NBC News Learn, and advisor to the Council of Chief State School Officers Early Literacy Networked Improvement Community. She has served as author or consultant on several educational programs, including Connect4Learning: The Pre-K Curriculum; Information in Action: Reading, Writing, and Researching with Informational Text; Engaging Families in Children’s Literacy Development: A Complete Workshop Series; Buzz About IT (Informational Text); iOpeners; National Geographic Science K-2; and the DLM Early Childhood Express. Duke also has a strong interest in improving the quality of educational research training in the U.S.

-

March 23, 2020 -

Alphabet Animals Reading Skills, Literacy

CVC words meaning: a three letter word made up of a consonant, vowel, consonant (ex. cat). The CVC pattern will always go in the order of consonant, vowel, consonant. The consonants and vowels change but the c-v-c pattern will remain the same. Sometimes these words are referred to as ‘CVC a words’ or ‘a CVC words’. This tells you what vowel will be in the middle of the word. For example, ‘i CVC words’ or ‘CVC i words’ would include words such as six, fin, or tin; always with an i as the vowel.

Below is a list of CVC words. This CVC words list gives some examples of CVC words for kindergarten.

Students are introduced to CVC words once they begin to learn the letters and the sounds the letters make. They can begin to put the sounds together to make words. This can be done in reading, writing, or hearing and producing the spoken sounds (as in phonemic awareness activities).

How to Teach CVC Words

Teaching CVC words is important when students are learning to read. One way to teach CVC words is with Elkonin Boxes. In a small group setting, give each student a mat with a different picture and three small manipulatives that fit inside each box. Have students place one manipulative under each box on their page. Tell them a CVC word, starting with one of the student’s pictures (ex. Teacher says, “Sally’s picture is a fox, let’s sound out fox.”) All students in your group follow the next steps even if their picture is not the word you call out. As you and students say each sound in the word, they slide one manipulative in a box, going from left to right. Once you have gone over all three sounds and all manipulatives are in the boxes, have students slide their finger under the boxes from left to right slowly and blend the sounds together. Then have them slide their finger fast under the boxes and read the word. Continue with other CVC words, use the pictures that are on the other students’ Elkonin Box pages. You can also have students sound out any CVC word in the boxes, it does not have to match the picture. Start with simple CVC words.

Reading CVC Words

We teach many reading strategies when students are learning to read. One reading strategy we teach is Sound Out The Word. When teaching and practicing this strategy, it is best to have books that have a lot of CVC words in them. This gives them practice focusing on this one strategy of decoding CVC words. There are some great CVC books to use when teaching this strategy. See below for our favorites, BOB books and I Can Read. Don’t have any of these and teaching the lesson soon? Look through the pages of the books you already have for CVC words. Dr. Seuss books usually have plenty of CVC kindergarten words. You can read the book and when you get to a CVC word, stop and let the student/s read that word. We love Dr. Seuss books when students are learning to read CVC words. They are filled with fun and easy CVC words.

Click on the books to purchase on Amazon.

Sample Reading CVC Words Lesson

Start off the lesson by showing them a CVC word written on a sentence strip or white board. Show them how to read CVC words by sounding out each letter, then blending the letters together to form the word. Do this with a few CVC words, and invite them to help you with the sounds and blending them together. Then show them the book they are to read and tell them they will be using this strategy to help them read the book. If some of your students are having trouble producing the sounds, it might be helpful to show them some CVC words with pictures. The pictures can help them produce the sounds of the letters.

Writing CVC Words

When teaching how to write with cvc words, we ask students to say the words as slowly as they can listening to each sound they hear. We ask them to use this writing strategy to write all of their words, but sometimes they skip over some of their sounds or add in extra sounds. So we take time to practice sounding out words together. Students sit on the learning carpet with a dry erase board, dry erase marker, and eraser. We call out CVC words, one at a time, and students say them slowly and put down the sounds they hear. This is a great lesson to watch and see where they might be having trouble and be able to guide them in the right direction.

CVC Word Practice Packets

There were many times where I felt that, towards the end of the year, most of my students mastered the skill of blending CVC words, but I still had one or two students who were struggling. I was lucky enough to have a paraprofessional in my class for a few hours a day, so I had her work with these students to catch them up. I made a packet of many different CVC word worksheets. Every morning during sign in, my paraprofessional pulled those students to a table for some CVC practice. She worked on the worksheets with them. This only took five minutes each morning, but it was such a big help! The students showed tremendous growth. Our CVC worksheets are self-explanatory and ready to be put into a packet. So if you don’t have a wonderful paraprofessional in your class, you can send this home for extra CVC word practice with their parents.

Worksheets for CVC Words

We have made some excellent kindergarten CVC words worksheets! There are twenty three pages of activities for CVC words that include:

- Sound out and write the words underneath the pictures. (one page for each vowel and a few pages with mixed vowels)

- Use a word bank to fill in the CVC words.

- CVC Reading: Circle the CVC word that matches the picture.

- Circle and color the CVC pictures that end with the matching letters at the beginning of each row.

- Unscramble the CVC word, write the word, then color the matching picture. (These pages are for students who are ready for a little more challenge.)

Frequently Asked Questions

CVC words means 3 letter words with consonant vowel consonant in that order. You can find samples of consonant vowel consonant words in the common CVC words list above.

CVC pattern words are mostly learned in kindergarten. Although some kids learn some of these words at an earlier or later age. See the list above for an example of CVC words kindergarten uses.

A CVC verb is any verb with the consonant, vowel, consonant pattern. The words run, sit, jog, dig are all CVC verbs.

Students should work on a variety of CVC words; words with each vowel and different consonants at the beginning and the end. The more they practice, the easier it will be for them to read new CVC words.

CVCC words are consonant, vowel, consonant, consonant words like mash or jump. CCVC words are consonant, consonant, vowel, consonant like flap or stop.

More CVC Word Work?

Are you teaching CVC words activities, like CVC Build a Word, that you don’t see here? We love hearing new ways of teaching all subjects. Please share with us in the comments.

Looking for more reading skills worksheets? We have plenty!! Check out our Alphabet Animals Reading Skills Curriculum. You can get the whole curriculum or just the worksheets you need for your class now. We hope you enjoy using our products. If you have any questions or comments, please leave them below. We will get back to you as soon as possible!

This page contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase I will get a small commission with no additional cost to you.

One Response

-

Thank you.

The examples were great help

Leave a Reply

More Blog Posts

How to Use Elkonin Boxes

November 15, 2022

Elkonin boxes are a great tool to use when teaching reading. Also called sound boxes, they are used to guide students to listen for sounds

Read More »

Hi, we’re Jackie,

LeighAnn and Jessica

We are a team of kindergarten teachers turned educational consultants. We help teachers like you with:

- easy to implement resources

- kindergarten curriculum

- fantastic ideas and tips to start in your classroom immediately

Our goal is to help you achieve success in your classroom while having fun with your students!

Subscribe to get the latest updates and all the freebies!

On the blog…

Reading wars, Whole word VS. Phonics, whole language advocates vs. phonetics enthusiasts…

Who would imagine that learning to read could be such a controversial topic?

But sadly, it is!

And I use the word SADLY for a good reason: Because the ones that normally pay the consequences of this disagreement are our children!

In this article we will look at the differences between the whole word approach and the phonics approach, so you can learn the ins and outs of this hot debate and form your own opinion.

If your child is learning to read, this is a crucial topic for you to understand as a parent. The reading success of your child can depend very much upon the actual approach used to teach your child to read; and, as you will discover on this article, schools do not always use the most effective method.

When it comes to teaching children to read there are two main teaching methods.

These two main methods are the whole word approach (also called the “sight words” approach) and the phonetic or phonics approach.

Some prefer the whole word method, while others use the phonics approach.

There are also educators that use a mix of different approaches.

But, who is right?

The Whole Word Approach

The whole word approach relies on what are called “sight words”. This method basically consists of getting children to memorize lists of words and teaching them various strategies of figuring out the text from a series of clues. Using the whole word approach, English is being taught as an ideographic language, such as Chinese or Japanese.

One of the biggest arguments of whole word advocates is that teaching to read using phonics breaks up the words into letters and syllables which have no actual meaning. Yet they fail to acknowledge that once the child is able to decode the word, they will be able to actually read that entire word, pronounce it and understand its meaning. So, in practicality, this is a very weak argument, from our point of view.

Unlike Chinese, English is an alphabet-based language. This means the letters of the English alphabet are not ideograms (also called ideographs), like Chinese characters are.

An ideogram (or ideograph) is a graphic symbol that represents an idea or a concept. Simply put, ideograms are like logos.

So, in a way, you could say that in the Chinese language you need to teach children to memorize “logos” and the meaning of each of them.

It is not logic to think that English should be taught using an ideographic approach…

So, the very popular reading programs that use a whole word approach simply get children to memorize words using different strategies, but without teaching any proper decoding methodology.

Think of the example we used before of the logos and the Chinese language.

Besides, there is no scientific evidence to suggest that teaching your child to using the whole word approach is an effective method. However, there are large numbers of studies which have consistently stated that teaching children to read using phonics and phonemic awareness is a highly effective method.

The Whole-Word Approach in Schools…

So, is your child learning to read using sight words? Or maybe a mixture of phonetics and sight words? What is the standard approach in our education system?

Well, every country – and even every educator / school – is different.

However, in English speaking countries in general -with the exception of the UK, which has been encouraging schools to adopt a systematic synthetic phonics approach since 2011- reading instruction is normally more heavily weighted towards the teaching of sight words, emphasizing the learning of “word shapes”.

Despite all the evidence to suggest otherwise, the whole word method of teaching still dominates how reading is taught at schools.

Why? Well, our guess is that children can appear to make fast progress with the whole language approach, and that makes everybody happy…

That is until their progress stalls, which is what usually happens, because with this method many children do not learn the relationships between letters and sounds correctly.

Some children can finally understand the letter-sound relationships from the words they have learned, but unfortunately many children aren’t able to figure this out. So, they are left with only one strategy for learning to read: memory and continuous repetition.

This is a very poor strategy these children are left with, in our opinion.

On the other hand, the reading ability of children is normally exaggerated on whole word programs as the texts used are very repetitive and extremely predictable. The children know what to expect. So… They are basically guessing!

When children are presented with a less predictable text without pictures, they struggle with words they had previously been able to figure out in a repetitive text with illustrations.

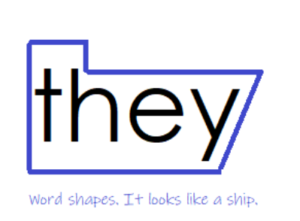

Another strategy used in whole word programs consists of focusing on word shapes.

Just have a look at this image. This is a “reading strategy” used on whole word programs.

Encouraging children to learn to read by looking at word shapes is completely madness! They are told to look at words as if they were “pictures”, focusing on the overhangs in the shapes of words! This does not apply for the English language!! Again, this is a method used for ideographic languages, such us Chinese or Japanese.

It does not make sense! There are just so many words with very similar shapes!

For example, look at this:

- hat vs. bat

- tree vs. free

- fall vs. tall vs hall

- hunt vs. hurt vs. hard

And the list goes on and on and on… Honestly, we could find thousands of words that have similar shape if we had the time to do this exercise!

The Whole- Word Method and Spelling

Even if a child has some early success learning to read using whole words programs, it gets him/her into the habit of ignoring the letters in words. This causes serious reading problems later on (when texts get more complicated), including spelling problems.

Another strategy that we are told to do on whole word programs is encouraging our children to look at the pictures in storybooks to “guess” or “predict” words.

-

Can they use the picture to help?

-

Can they look at the initial letter and predict what word would make sense that starts with that letter?

-

What word makes sense based on the context?

A little bit of history on the Whole-Word Approach

The main idea behind this theory is that if you see words enough number of times, you eventually store them in your memory as visual images.

They also embrace the idea that kids can naturally learn to read if they are exposed a lot of books.

Since the 1980s, these beliefs had strongly influenced the way children in North America and most English speaking countries are taught to read and write.

These ideas start to emerge in the 1970’s, and they become extremely popular for teaching reading in the 80’s and 90’s.

There is a strong focus on meaning, rather than sounds.

The Phonics Approach

At the opposite end of the spectrum, we find reading instruction based on phonemic awareness and phonics.

The phonics approach focuses on the sounds in words, which are represented by the letters (or groups of letters) in the alphabet.

There is a myriad of methods and systems within the phonics approach itself, but the the two main methodologies for teaching phonics are Synthetic and Analytic phonics.

Even though they both have the label “Phonics” attached to them, they are in fact quite different ways for teaching children to read.

However, for the sake of this article (and to keep things simple) we will just say that the main difference is that in the Synthetic Phonics approach skills are taught in a highly structured ‘systematic’ way.

Children start with very simple sounds and decoding regular words. Gradually, they are introduced to more complex sounds (such us letter combination sounds) and to irregularities and exceptions. Every step of the way is planned, and children only move to the next stage of phonics once they have mastered the previous one.

In the Analytic Phonics approach, reading instruction is less structured, and learning happens in a more ‘embedded’ fashion. Children are encouraged to analyze groups of whole words to identify similar sounds and letter patterns. Instruction relies a lot on the analysis of “families of words”.

For instance, the family of words ending up in -all, such us “tall, fall, mall, hall, small”, or the family of words ending up in -at, such “mat, cat, rat, bat, fat, pat”.

If you are interested in knowing more about the differences between analytics and synthetic phonics, you can check this video.ç

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/twDjIsFkhFM” title=”YouTube video player” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>

Is there a Winner in the Reading Wars?

What Research / Modern Science has to say…

The best way to put an end to this controversy and start making decisions that are RIGHT for our kids – and not based on personal preferences or ideology- is by looking at what research and scientific studies have to say.

However, you may think that if opinions on the topic are still so divided, then it must be that the results of these studies are somehow inconclusive.

Well, not really…

Look at these statements by the US National Reading

“Teaching children to manipulate phonemes in words was highly effective under a variety of teaching conditions with a variety of learners across a range of grade and age levels and that teaching phonemic awareness to children significantly improves their reading more than instruction that lacks any attention to Phonemic Awareness.”

“Conventional wisdom has suggested that kindergarten students might not be ready for phonics instruction, this assumption was not supported by the data. The effects of systematic early phonics instruction were significant and substantial in kindergarten and the 1st grade, indicating that systematic phonics programs should be implemented at those age and grade levels.”

^* Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Excerpts from the meta-analysis of over 1,900 scientific studies.

Overwhelmingly research has found that phonemic awareness and phonics is a superior way for teaching children to read!

But wait there is more…

Modern Scientific Research on the Brain and How we learn to read

For a very long time many experts have embraced the idea that we store words in our memory in the same way we store visual memories, such us faces or objects. That belief is at the core of the whole word approach.

And, in fact, many reading experts still believe this is the cse.

However, modern scientific research proves otherwise…

But before I tell you how we actually store words in our memory, look at the following factors already pointing out at how visual memory -contrary to still popular belief – is NOT involved:

-

We can read mixed case letters without difficulties.

-

We can read words with different fonts, in print and cursive, and handwritting without difficulties.

-

Word recognition works faster than object recognition, indicating that we are using different storage and retrieval processes.

Let me tell you about the sound scientific evidence now…

Brain scans show that the parts of the brain activated while performing visual memory tasks are different than the parts of the brain activated while reading…

Moreover, scientists in the visual memory area (not related to reading research, therefore unbiased) have indicated that we don’t have the cognitive capacity to remember 30 – 90,000 words for immediate retrieval.

As reading instruction still assumes that we store words as visual images, students who struggle to remember words are many times presumed to have poor visual memory.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. There is only a small relationship between visual memory and our capacity to store words for immediate retrieval while reading.

However, there is a very strong relationship between HEARING skills and our capacity to store words for immediate retrieval while reading (fluent reading capacity).

To be more specific, children that have been trained to hear the actual sounds that form words (phonemic /phonological skills) and are capable to recognize and store those common strings of sounds and visually link them to the letters / words they know become fluent readers.

There is no evidence to suggest that visual memory has a role in word recognition /reading fluency once the letters and the connection between letters and sounds have been learned.

If there seems to be a winner on the ‘Reading Wars’, why do we keep arguing?

Phonics instruction cons…

These are the main arguments against phonics instruction:

- Children only read phonics books: This is one of the main pillars of a proper phonics system. Children should only attempt to read books that are in line with their level of phonics. Otherwise, it is overwhelming for them and can get confused, since they may be exposed to too many exceptions and irregularities. While this is true, that doesn’t mean that parents can’t read more difficult books to their children. And, in fact, they are encouraged to do so.

- Phonics doesn’t help with reading comprehension. Besides, teaching to read using phonics breaks up the words into letters and syllables, which have no actual meaning. However, once the child is able to decode the word, he/she will be able to actually read that entire word, pronounce it and understand its meaning.

- Children learn to read naturally, therefore they don’t need tedious phonics instruction. Whereas it is truth that some children can learn to read by themselves, most won’t be able to figure it out. Besides, there is no harm in receiving phonics instruction for those that are able to learn to decode by themselves.

- There are just too many exceptions and irregularities in English. While it is true that English is full of irregularities and exceptions, there are less of these than what we are led to believe. Besides, there are some rules, patterns and tips and tricks that apply to those “irregular” words that certainly do help in the process of learning to read.

So, saying that phonics has won the war is quite far from what happens in reality.

As we stated at the beginning of the article, there are different ways for teaching phonics.

What our schools have evolved to do to keep both sides of the war happy is establishing a “balanced literacy” strategy that combines both whole word and phonics principles.

What in practicality ends up happening is that there is only a little bit of phonics instruction here and there, rather than a proper curriculum based on phonics.

That is an ineffective method for teaching phonics, and certainly doesn’t work. And this is precisely the sort of evidence that whole word enthusiasts hold on to.

Final thoughts on the Reading Wars

The debate is still hot. This is bizarre as, in our opinion, based on the latest scientific evidence, the number one skill that we need to develop in our children is phonemic awareness.

This way we would have far fewer students with reading difficulties.

And, after having developed strong phonological / phonemic awareness skills, using a proper phonics approach (and not just a little bit of phonics instruction here and there) seems like the way to go.

Free Resources you may be interested in!

Phonemic Awareness Activity Worksheets

Nursery Rhymes Ebook

44+ English sounds chart

List of CVC Words