2 Мистер Фогг и его друг Паспарту начали путешествие по миру.

1) Прочтите еще одну выдержку из книги. О каких пунктах назначения идет речь? Найдите места на карте. (чтение для конкретной информации)

Паспарту начал очень серьезно относиться к странным шансам(случаям) that (которые) сводили их с Фиксом. И это действительно удивительно. Здесь был пассажир, (whom) с которым они встретились сначала в Суэце, (when) когда они плыли по Монголии, а затем он вышел в Бомбее. Затем он добрался до «Рангуна» по дороге в Гонконг. Он шаг за шагом следовал за мистером Фоггом. Это было очень странно. Паспарту был уверен, что Фикс покинет Гонконг одновременно с мистером Фоггом и, вероятно, одним и тем же пароходом.

Паспарту никогда не угадал бы реальную причину (which) почему за Мистером Фоггом была слежка. Он никогда бы не подумал, что мистера Фогга преследуют по всему миру как разбойника. Но так как всем людям нравится находить объяснение всего, Паспарту нашел объяснение (that), которое казалось очень разумным. Фикс, он был уверен, был послан членами клуба реформ, чтобы убедиться, что путешествие было проведено справедливо и по соглашению.

«Должно быть, это!» — сказал Паспарту, гордый своей сообразительностью. «Он был тайно отправлен, чтобы убедиться, что мистер Фогг не вытворяет никаких трюков. Это неправильно. Aх! Джентльмены из клуба реформ, вы пожалеете о своем поведении! »

Довольный своим открытием, Паспарту решил не говорить об этом мистеру Фоггу. Он боялся, что его чувства пострадают от недоверия, проявленного его друзьями. Паспарту решил притвориться, что, по его мнению, мистер Фикс был туристическим агентом из судоходной компании.

В среду днем, 30 октября, Рангун прошел через Малаккский пролив, (which) который отделяет остров Суматру от Малайзии. Красивые маленькие острова, с их склонами, скрывали вид на Суматру от пассажиров. В четыре часа следующего утра Рангун остановился в Сингапуре. Мистер Фогг вышел на берег, чтобы отправиться на короткую прогулку. Фикс, (who) который не доверял каждому действию Фогга, тайно следовал за ним. Паспарту забавно было видеть, как он это делает. Паспарту вышел на берег, (when) когда он собирался купить фрукты.

После приятной прогулки по холмам мистер Фогг вернулся в город, а в десять часов добрался до лодки. За ним следовал детектив, (who) который конечно, никогда не терял из виду его.

В одиннадцать часов Рангун покинул Сингапур.

2) Найдите в тексте: а) географические названия (города, остров); b) собственные имена (корабли, компания, клуб). Какие артикли используются с именами? (чтение для конкретной информации)

ГДЗ #

Mr Fix was this very’ kind gentleman whom they met first at Suez, sailing on the Mongolia, getting off at Bombay, then appearing on the Rangoon.

Mr.Fix was following Mr Fogg step by step.

Fix had been sent by members of the Reform Club to see that the journey was carried out fairly.

Passepartout felt sure that Fix would leave Hong Kong.

The Rangoon passed through the Straits of Malacca.

Passepartout would never guess the real reason for which Mr Fogg was being followed.

Mr Fogg went on shore to go for a short walk.

Mr Fogg came back to the town, and at ten o’clock got on board the boat

At eleven o’clock the Rangoon steamed out of Singapore.

Грамматика в фокусе

Артикль

Артикль с географическими названиями и именами собственными

Suez, but the Suez Canal

3) Словообразование. Найдите слова в отрывке, которые формируются от следующих слов. Как они формируются? Переведите слова.

СЛОВООБРАЗОВАНИЕ

Суффиксы:

— существительных: -ation, -ness, -iour, -y

— прилагательных: -ing, -able, -ful

— наречий: -ly

Приставка: dis-

serious(серьезный) — adv

surprise (удивлять) – a

explain (объяснять)— n

reason (причина) — a

fair (честно)— adv

agree (соглашаться) — n

clever (умный) — n

secret (секрет)— adv

behave(вести себя) — n

discover (открывать)— n

trust (доверять) — n

beauty (красота)— a

act (действовать)— n

4) Заполните пробелы в отрывке относительными местоимениями: who, where, when, that, which (кто, где, когда, тот, который) (понимание грамматических структур)

Ответы подчеркнуты в тексте упр.2 (1)

Грамматика для проверки

Относительные местоимения.

Придаточные с who, where, when, which, that

Here was this kind gentleman who they met at Suez.

(Вот этот добрый джентльмен, которого они встретили в Суэце).

GS p. 200

5) Учимся переводить. В отрывке найдите предложения с аналогичной структурой. Переведите их, (понимание грамматических структур)

Грамматика для проверки

Would

Passepartout felt sure that Fix would leave Hong Kong at the same time as Mr Fogg.

Паспарту был уверен, что Фикс покинет Гонконг в то же самое время, что и мистер Фогг

GS р. 197

6) Определите, следующие утверждения верны (T) или неверны (F) в соответствии с историей. Докажите это из текста, (чтение для подробностей)

1) Мистер Фогг и Паспарту были очень удивлены встретить своего друга в Суэце. — F

2) Мистер Фогг и Паспарту впервые увидели мистера Фикса, когда они отправились в Бомбей. — T

3) Паспарту думал, что мистер Фикс был туристическим агентом. — F

4) Мистер Фикс последовал за мистером Фоггом, чтобы проверить, была ли поездка справедливой. — F

5) Мистер Фогг не знал, что за ним последовал мистер Фикс. — T

7) Заполните резюме с географическими и собственными именами из отрывка, (чтение для деталей / заметок)

Странно, что мистер Фикс следовал за мистером Фоггом и Пассепарту шаг за шагом. Они встретились с мистером Фиксом сначала в Суэце, а затем в Бомбее. Затем мистер Фикс появился на борту Рангуна по дороге в Гонконг. Паспарту считает, что мистер Фикс был отправлен членами клуба реформ, чтобы увидеть, что путешествие

было проведено справедливо. Когда корабль остановился в Сингапуре, мистер Фогг отправился на прогулку. Мистер Фикс тайно последовал за мистером Фоггом и никогда не упускал из виду его, пока пароход не покинул Сингапур

ГДЗ #

Suez (Суэц); Bombay (Бомбей); the Rangoon(Рагун); Hong Kong(Гонконг); the Reform Club (клуб реформ); Singapore(Сингапур); Singapore(Сингапур).

2 Mr Fogg and his friend Passepartout started their journey round the world.

1) Read another extract from the book. What destinations is the extract about? Find the places on the map. (reading for specific information)

Passepartout began thinking very seriously about the strange chance … kept Fix with them. And it really was surprising. Here was the passenger … they met first at Suez, … they were sailing on the Mongolia and then he got off at Bombay. Then he got aboard’ the Rangoon on his way to Hong Kong. He was following Mr Fogg step by step.I It was very strange. Passepartout was sure that Fix would leave Hong Kong at the same time as Mr Fogg, and probably by the same steamship.

Passepartout would never guess the real reason for … Mr Fogg was being followed. He would never imagine that Mr Fogg was followed round the world as a robber. But as all people like to find an explanation of everything, Passepartout found an explanation … seemed very reasonable. Fix, he was sure, had been sent by members of the Reform Club to see that the journey was carried out fairly and according to the agreement.

“It must be that!” said Passepartout, proud at his cleverness. “He has been sent secretly to make sure that Mr Fogg is not playing any tricks. That is not right. Alt! Gentlemen of the Reform Club, you will be sorry for your behaviour!”

Pleased with his discovery, Passepartout made up his mind to say nothing to Mr Fogg about it. He was afraid that his feelings would be hurt at the distrust shown by his friends. Passepartout decided to pretend that he thought Mr Fix was a travel agent from the Shipping Company.

On Wednesday afternoon, October 30th, the Rangoon passed through the Straits of Malacca,… separate the island of Sumatra from the Malays. Beautiful little islands, with their mountainsides, hid the view of Sumatra from the passengers. At four o’clock the next morning the Rangoon stopped at Singapore. Mr Fogg went on shore’1 to go for a short walk. Fix, .. distrusted every action of Fogg’s, followed him secretly. Passepartout was amused to see him doing this. Passepartout went on shore …. he was going to buy some fruit.

After a pleasant walk in the hills, Mr Fogg came back to the town, and at ten o’clock got on board the boat. He was followed by the detective, … of course, had never lost sight of him.

At eleven o’clock the Rangoon left Singapore.

2) Find in the text: a) the geographical names (the cities, the island); b) the proper names (the ships, the company, the club). What articles are used with the names? (reading for specific information)

Grammar for revision

The article

Артикль с географическими названиями и именами собственными

Suez, but the Suez Canal

GS. P 183

3) Word building. Find the words in the extract that are formed from the following words. How are they formed? Translate the words.

WORD BUILDING

Суффиксы:

существительных: -ation, -ness, -iour, -y

прилагательных: -ing, -able, -ful

наречий: -ly

Приставка: dis-

GS p. 201

serious — adv

surprise – a

explain — n

reason — a

fair — adv

agree — n

clever — n

secret — adv

behave — n

discover — n

trust — n

beauty — a

act — n

4) Fill in the gaps in the extract with the relative pronouns: who, where, when, that, which, (understanding grammar structures)

Grammar for revision

Relative clauses .

Придаточные с who, where, when, which, that

Here was this kind gentleman who they met at Suez.

GS p. 200

5) Learning to translate. In the extract, find the sentences with the similar structure. Translate them, (understanding grammar structures)

Grammar for revision

Would

Passepartout felt sure that Fix would leave Hong Kong at the same time as Mr Fogg.

Паспарту был уверен, что Фикс покинет Гонконг в то же самое время, что и мистер Фогг

GS р. 197

6) Decide if the following statements are true (T) or false (F) according to the story. Prove it from the text, (reading for detail)

1) Mr Fogg and Passepartout were very surprised to meet their friend at Suez. — F

2) Mr Fogg and Passepartout saw Mr Fix first when they travelled to Bombay. — T

3) Passepartout thought that Mr Fix was a travel agent. — F

4) Mr Fix followed Mr Fogg to check if the trip was fair. — F

5) Mr Fogg didn’t know that he was followed by Mr Fix on purpose. — T

7) Complete the summary with the geographical and proper names from the extract, (reading for detail/making notes)

It was strange that Mr Fix was following Mr Fogg and Passepartout step by step. They met Mr Fix first at Suez and then at Bombay . Then Mr Fix appeared on board of the Rangoon on them way to Hong Kong. Passepartout hought that Mr Fix was sent by the members of the Reform Club to see that the journey was carried out fairly. When the ship stopped at. Singapore, Mr Fogg went on shore to go for a walk. Mr Fix followed Mr Fogg secretly and never lost sight of him till the steamship left Singapore

На этой странице вы сможете найти и списать готовое домешнее задание (ГДЗ) для школьников по предмету Английский язык, которые посещают 8 класс из книги или рабочей тетради под названием/издательством «Решебник ГДЗ English», которая была написана автором/авторами: Кузовлев. ГДЗ представлено для списывания совершенно бесплатно и в открытом доступе.

Chapter 5 how english words are made. word-building1

Before turning to the various processes of making words, it would be useful to analyse the related problem of the composition of words, i. e. of their constituent parts.

If viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units which are called morphemes. Morphemes do not occur as free forms but only as constituents of words. Yet they possess meanings of their own.

All morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots (or radicals} and affixes. The latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes which precede the root in the structure of the word (as in re-read, mis-pronounce, un-well) and suffixes which follow the root (as in teach-er, cur-able, diet-ate).

Words which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word-building known as affixation (or derivation).

Derived words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary. Successfully competing with this structural type is the so-called root word which has only a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by a great number of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier borrowings (house, room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.), and, in Modern English, has been greatly enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion (e. g. to hand, v. formed from the noun hand; to can, v. from can, п.; to pale, v. from pale, adj.; a find, n. from to find, v.; etc.).

Another wide-spread word-structure is a compound word consisting of two or more stems2 (e. g. dining-room, bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing). Words of this structural type are produced by the word-building process called composition.

The somewhat odd-looking words like flu, pram, lab, M. P., V-day, H-bomb are called shortenings, contractions or curtailed words and are produced by the way of word-building called shortening (contraction).

The four types (root words, derived words, compounds, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word-building.

To return to the question posed by the title of this chapter, of how words are made, let us try and get a more detailed picture of each of the major types of Modern English word-building and, also, of some minor types.

Affixation

The process of affixation consists in coining a new word by adding an affix or several affixes to some root morpheme. The role of the affix in this procedure is Very important and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the main types of affixes.

From the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same two large groups as words: native and borrowed.

Some Native Suffixes1

|

Noun-forming |

-er |

worker, miner, teacher, painter, etc. |

|

-ness |

coldness, loneliness, loveliness, etc. |

|

|

-ing |

feeling, meaning, singing, reading, etc. |

|

|

-dom |

freedom, wisdom, kingdom, etc. |

|

|

-hood |

childhood, manhood, motherhood, etc. |

|

|

-ship |

friendship, companionship, mastership, etc. |

|

|

-th |

length, breadth, health, truth, etc. |

|

|

Adjective-forming |

-ful |

careful, joyful, wonderful, sinful, skilful, etc. |

|

-less |

careless, sleepless, cloudless, senseless, etc. |

|

|

-y |

cozy, tidy, merry, snowy, showy, etc. |

|

|

-ish |

English, Spanish, reddish, childish, etc. |

|

|

-ly |

lonely, lovely, ugly, likely, lordly, etc. |

|

|

-en |

wooden, woollen, silken, golden, etc. |

|

|

-some |

handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome, etc. |

|

|

Verb-forming |

-en |

widen, redden, darken, sadden, etc. |

|

Adverb-forming |

-ly |

warmly, hardly, simply, carefully, coldly, etc. |

Borrowed affixes, especially of Romance origin are numerous in the English vocabulary (Ch. 3). It would be wrong, though, to suppose that affixes are borrowed in the same way and for the same reasons as words. An affix of foreign origin can be regarded as borrowed only after it has begun an independent and active life in the recipient language, that is, is taking part in the word-making processes of that language. This can only occur when the total of words with this affix is so great in the recipient language as to affect the native speakers’ subconscious to the extent that they no longer realize its foreign flavour and accept it as their own.

* * *

Affixes can also be classified into productive and non-productive types. By productive affixes we mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in this particular period of language development. The best way to identify productive affixes is to look for them among neologisms and so-called nonce-words, i. e. words coined and used only for this particular occasion. The latter are usually formed on the level of living speech and reflect the most productive and progressive patterns in word-building. When a literary critic writes about a certain book that it is an unputdownable thriller, we will seek in vain this strange and impressive adjective in dictionaries, for it is a nonce-Word coined on the current pattern of Modern English and is evidence of the high productivity of the adjective-forming borrowed suffix -able and the native prefix un-.

Consider, for example, the following:

Professor Pringle was a thinnish, baldish, dispeptic-lookingish cove with an eye like a haddock.

(From Right-Ho, Jeeves by P. G. Wodehouse)

The adjectives thinnish and baldish bring to mind dozens of other adjectives made with the same suffix; oldish, youngish, mannish, girlish, fattish, longish, yellowish, etc. But dispeptic-lookingish is the author’s creation aimed at a humorous effect, and, at the same time, proving beyond doubt that the suffix -ish is a live and active one.

The same is well illustrated by the following popular statement: «I don’t like Sunday evenings: I feel so Mondayish». (Mondayish is certainly a nonce-word.)

One should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency of occurrence. There are quite & number of high-frequency affixes which, nevertheless, are no longer used in word-derivation (e. g. the adjective-forming native suffixes -ful, -ly; the adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin -ant, -ent, -al which are quite frequent).

Some Productive Affixes

|

Noun-forming suffixes |

-er, -ing, -ness, -ism1 (materialism), -ist1 (impressionist), -ance |

|

Adjective-forming suffixes |

-y, -ish, -ed (learned), -able, -less |

|

Adverb-forming suffixes |

-ly |

|

Verb-forming suffixes |

-ize/-ise (realize), -ate |

|

Prefixes |

un(unhappy), re(reconstruct), dis (disappoint) |

Note. Examples are given only for the affixes which are not listed in the tables at p. 82 and p. 83.

Some Non-Productive Affixes

|

Noun-forming suffixes |

-th,-hood |

|

Adjective-forming suffixes |

-ly, -some, -en, -ous |

|

Verb-forming suffix |

-en |

Note. The native noun-forming suffixes -dom and -ship ceased to be productive centuries ago. Yet, Professor I. V. Arnold in The English Word gives some examples of comparatively new formations with the suffix -dom: boredom, serfdom, slavedom [15]. The same is true about -ship (e. gsalesmanship). The adjective-forming -ish, which leaves no doubt as to its productivity nowadays, has comparatively recently regained it, after having been non-productive for many centuries.

Semantics of Affixes

The morpheme, and therefore affix, which is a type of morpheme, is generally defined as the smallest indivisible component of the word possessing a meaning of its own. Meanings of affixes are specific and considerably differ from those of root morphemes. Affixes have widely generalized meanings and refer the concept conveyed by the whole word to a certain category, which is vast and all-embracing. So, the noun-forming suffix -er could be roughly defined as designating persons from the object of their occupation or labour (painter — the one who paints) or from their place of origin or abode {southerner — the one living in the South). The adjective-forming suffix -ful has the meaning of «full of», «characterized by» (beautiful, careful) whereas -ish Olay often imply insufficiency of quality (greenish — green, but not quite; youngish — not quite young but looking it).

Such examples might lead one to the somewhat hasty conclusion that the meaning of a derived word is always a sum of the meanings of its morphemes: un/eat/able =» «not fit to eat» where not stands for unand fit for: -able.

There are numerous derived words whose meanings can really be easily deduced from the meanings of their constituent parts. Yet, such cases represent only the first and simplest stage of semantic readjustment with in derived words. The constituent morphemes within derivatives do not always preserve their current meanings and are open to subtle and complicated semantic shifts.

Let us take at random some of the adjectives formed with the same productive suffix -y, and try to deduce the meaning of the suffix from their dictionary definitions:

brainy (inform.) — intelligent, intellectual, i. e, characterized by brains

catty — quietly or slyly malicious, spiteful, i. e, characterized by features ascribed to a cat

chatty — given to chat, inclined to chat

dressy (inform.) — showy in dress, i. e. inclined to dress well or to be overdressed

fishy (e. g. in a fishy story, inform.) — improbable, hard to believe (like stories told by fishermen)

foxy — foxlike, cunning or crafty, i. e. characterized by features ascribed to a fox

stagy — theatrical, unnatural, i. e. inclined to affectation, to unnatural theatrical manners

touchy — apt to take offence on slight provocation, i. e. resenting a touch or contact (not at all inclined to be touched)1

The Random-House Dictionary defines the meaning of the -y suffix as «characterized by or inclined to the substance or action of the root to which the affix is attached». [46] Yet, even the few given examples show that, on the one hand, there are cases, like touchy or fishy that are not covered by the definition. On the other hand, even those cases that are roughly covered, show a wide variety of subtle shades of meaning. It is not only the suffix that adds its own meaning to the meaning of the root, but the suffix is, in its turn, affected by the root and undergoes certain semantic changes, so that the mutual influence of root and affix creates a wide range of subtle nuances.

But is the suffix -y probably exceptional in this respect? It is sufficient to examine further examples to see that other affixes also offer an interesting variety of semantic shades. Compare, for instance, the meanings of adjective-forming suffixes in each of these groups of adjectives.

1. eatable (fit or good to eat)2

lovable (worthy of loving)

questionable (open to doubt, to question)

imaginable (capable of being imagined)

2. lovely (charming, beautiful, i. e. inspiring love)

lonely (solitary, without company; lone; the meaning of the suffix does not seem to add anything to that of the root)

friendly (characteristic of or befitting a friend.)

heavenly (resembling or befitting heaven; beautiful, splendid)

3. childish (resembling or befitting a child)

tallish (rather tall, but not quite, i. e. approaching the quality of big size)

girlish (like a girl, but, often, in a bad imitation of one)

bookish (1) given or devoted to reading or study;

(2) more acquainted with books than with real life, i. e. possessing the quality of bookish learning)

The semantic distinctions of words produced from the same root by means of different affixes are also of considerable interest, both for language studies and research work. Compare: womanly — womanish, flowery — flowered -— flowering, starry — starred, reddened — reddish, shortened — shortish.

The semantic difference between the members of these groups is very obvious: the meanings of the suffixes are so distinct that they colour the whole words.

Womanly is used in a complimentary manner about girls and women, whereas womanish is used to indicate an effeminate man and certainly implies criticism.

Flowery is applied to speech or a style (cf. with the R. цветистый), flowered means «decorated with a patters of flowers» (e. g. flowered silk or chintz, cf. with the R, цветастый) and flowering is the same as blossoming (e. g. flowering bushes or shrubs, cf. with the R. цветущий).

Starry means «resembling stars» (e. g. starry eyes) and starred — «covered or decorated with stars» (e. g. starred skies).

Reddened and shortened both imply the result of an action or process, as in the eyes reddened with weeping or a shortened version of a story (i. e. a story that has been abridged) whereas shortish and reddish point to insufficiency of quality: reddish is not exactly red, but tinged with red, and a shortish man is probably a little taller than a man described as short.

Conversion

When in a book-review a book is referred to as a splendid read, is read to be regarded as a verb or a noun? What part of speech is room in the sentence: I was to room with another girl called Jessie. If a character in a novel is spoken about as one who had to be satisfied with the role of a has-been, what is this odd-looking has-been, a verb or a noun? One must admit that it has quite a verbal appearance, but why, then, is it preceded by the article?

Why is the word if used in the plural form in the popular proverb: If ifs and ans were pots and pans? (an = if, dial., arch.)

This type of questions naturally arise when one deals with words produced by conversion, one of the most productive ways of modern English word-building.

Conversion is sometimes referred to as an affixless way of word-building or even affixless derivation. Saying that, however, is saying very little because there are other types of word-building in which new words are also formed without affixes (most compounds, contracted words, sound-imitation words, etc.).

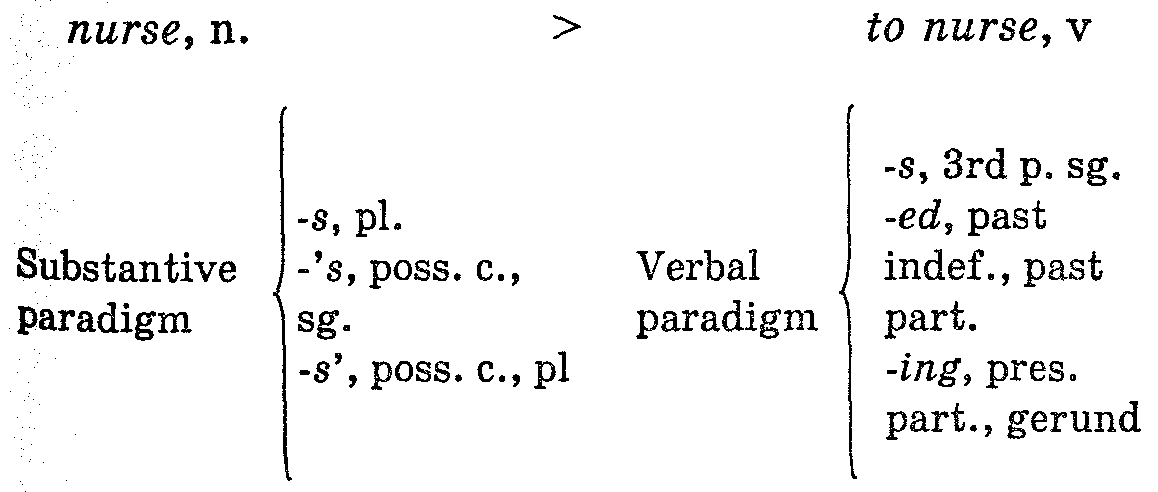

Conversion consists in making a new word from some existing word by changing the category of a part of speech, the morphemic shape of the original word remaining unchanged. The new word has a meaning Which differs from that of the original one though it can more or less be easily associated with it. It has also a new paradigm peculiar to its new category as a part of speech.

The question of conversion has, for a long time, been a controversial one in several aspects. The very essence of this process has been treated by a number of scholars (e. g. H. Sweet), not as a word-building act, but as a mere functional change. From this point of view the word hand in Hand me that book is not a verb, but a noun used in a verbal syntactical function, that is, hand (me) and hands (in She has small hands) are not two different words but one. Hence, the case cannot be treated as one of word-formation for no new word appears.

According to this functional approach, conversion may be regarded as a specific feature of the English categories of parts of speech, which are supposed to be able to break through the rigid borderlines dividing one category from another thus enriching the process of communication not by the creation of new words but through the sheer flexibility of the syntactic structures.

Nowadays this theory finds increasingly fewer supporters, and conversion is universally accepted as one of the major ways of enriching English vocabulary with new words. One of the major arguments for this approach to conversion is the semantic change that regularly accompanies each instance of conversion. Normally, a word changes its syntactic function without any shift in lexical meaning. E. g. both in yellow leaves and in The leaves were turning yellow the adjective denotes colour. Yet, in The leaves yellowed the converted unit no longer denotes colour, but the process of changing colour, so that there is an essential change in meaning.

The change of meaning is even more obvious in such pairs as hand > to hand, face > to face, to go > a go, to make > a make, etc.

The other argument is the regularity and completeness with which converted units develop a paradigm of their new category of part of speech. As soon as it has crossed the category borderline, the new word automatically acquires all the properties of the new category, so that if it has entered the verb category, it is now regularly used in all the forms of tense and it also develops the forms of the participle and the gerund. Such regularity can hardly be regarded as indicating a mere functional change which might be expected to bear more occasional characteristics. The completeness of the paradigms in new conversion formations seems to be a decisive argument proving that here we are dealing with new words and not with mere functional variants. The data of the more reputable modern English dictionaries confirm this point of view: they all present converted pairs as homonyms, i. e. as two words, thus supporting the thesis that conversion is a word-building process.

Conversion is not only a highly productive but also a particularly English way of word-building. Its immense productivity is considerably encouraged by certain features of the English language in its modern Stage of development. The analytical structure of Modern English greatly facilitates processes of making words of one category of parts of speech from words of another. So does the simplicity of paradigms of En-lush parts of speech. A great number of one-syllable Words is another factor in favour of conversion, for such words are naturally more mobile and flexible than polysyllables.

Conversion is a convenient and «easy» way of enriching the vocabulary with new words. It is certainly an advantage to have two (or more) words where there Was one, all of them fixed on the same structural and semantic base.

The high productivity of conversion finds its reflection in speech where numerous occasional cases of conversion can be found, which are not registered by dictionaries and which occur momentarily, through the immediate need of the situation. «If anybody oranges me again tonight, I’ll knock his face off, says the annoyed hero of a story by O’Henry when a shop-assistant offers him oranges (for the tenth time in one night) instead of peaches for which he is looking («Lit. tie Speck in Garnered Fruit»). One is not likely to find the verb to orange in any dictionary, but in this situation it answers the need for brevity, expressiveness and humour.

The very first example, which opens the section on conversion in this chapter (the book is a splendid read), though taken from a book-review, is a nonce-word, which may be used by reviewers now and then or in informal verbal communication, but has not yet found its way into the universally acknowledged English vocabulary.

Such examples as these show that conversion is a vital and developing process that penetrates contemporary speech as well. Subconsciously every English speaker realizes the immense potentiality of making a word into another part of speech when the need arises.

* * *

One should guard against thinking that every case of noun and verb (verb and adjective, adjective and noun, etc.) with the same morphemic shape results from conversion. There are numerous pairs of words (e. g. love, n. — to love, v.; work, n. — to work, v.; drink, n. — to drink, v., etc.) which did, not occur due to conversion but coincided as a result of certain historical processes (dropping of endings, simplification of stems) when before that they had different forms (e. g. O. E. lufu, n. — lufian, v.). On the other hand, it is quite true that the first cases of conversion (which were registered in the 14th c.) imitated such pairs of words as love, n. — to love, v. for they were numerous to the vocabulary and were subconsciously accepted by native speakers as one of the typical language patterns.

* * *

The two categories of parts of speech especially affected by conversion are nouns and verbs. Verbs made from nouns are the most numerous amongst the words produced by conversion: e. g. to hand, to back, to face, to eye, to mouth, to nose, to dog, to wolf, to monkey, to can, to coal, to stage, to screen, to room, to floor, to ^lack-mail, to blacklist, to honeymoon, and very many ethers.

Nouns are frequently made from verbs: do (e. g. This ifs the queerest do I’ve ever come across. Do — event, incident), go (e. g. He has still plenty of go at his age. Go — energy), make, run, find, catch, cut, walk, worry, show, move, etc.

Verbs can also be made from adjectives: to pale, to yellow, to cool, to grey, to rough (e. g. We decided sq rough it in the tents as the weather was warm), etc.

Other parts of speech are not entirely unsusceptible to conversion as the following examples show: to down, to out (as in a newspaper heading Diplomatist Outed from Budapest), the ups and downs, the ins and outs, like, n. (as in the like of me and the like of you).

* * *

It was mentioned at the beginning of this section that a word made by conversion has a different meaning from that of the word from which it was made though the two meanings can be associated. There are Certain regularities in these associations which can be roughly classified. For instance, in the group of verbs made from nouns some of the regular semantic associations are as indicated in the following list:

I. The noun is the name of a tool or implement, the verb denotes an action performed by the tool: to hammer, to nail, to pin, to brush, to comb, to pencil.

II. The noun is the name of an animal, the verb denotes an action or aspect of behaviour considered typical of this animal: to dog, to wolf, to monkey, to ape, to fox, to rat. Yet, to fish does not mean «to behave like a fish» but «to try to catch fish». The same meaning of hunting activities is conveyed by the verb to whale and one of the meanings of to rat; the other is «to turn informer, squeal» (sl.).

III. The name of a part of the human body — an action performed by it: to hand, to leg (sl.), to eye, to elbow, to shoulder, to nose, to mouth. However, to face does not imply doing something by or even with one’s face but turning it in a certain direction. To back means either «to move backwards» or, in the figurative sense, «to support somebody or something».

IV. The name of a profession or occupation — an activity typical of it: to nurse, to cook, to maid, to groom.

V. The name of a place — the process of occupying» the place or of putting smth./smb. in it (to room, to house, to place, to table, to cage).

VI. The name of a container — the act of putting smth. within the container (to can, to bottle, to pocket).

VII. The name of a meal — the process of taking it (to lunch, to supper).

The suggested groups do not include all the great variety of verbs made from nouns by conversion. They just represent the most obvious cases and illustrate, convincingly enough, the great variety of semantic interrelations within so-called converted pairs and the complex nature of the logical associations which specify them.

In actual fact, these associations are not only complex but sometimes perplexing. It would seem that if you know that the verb formed from the name of an animal denotes behaviour typical of the animal, it would easy for you to guess the meaning of such a verb provided that you know the meaning of the noun. Yet, it is not always easy. Of course, the meaning of to fox is rather obvious being derived from the associated reputation of that animal for cunning: to fox means «to act cunningly or craftily». But what about to wolf? How is one to know which of the characteristics of the animal was picked by the speaker’s subconscious when this verb was produced? Ferocity? Loud and unpleasant fowling? The inclination to live in packs? Yet, as the Hollowing example shows, to wolf means «to eat greedily, voraciously»: Charlie went on wolfing the chocolate. (R. Dahl)

In the same way, from numerous characteristics of | be dog, only one was chosen for the verb to dog which is well illustrated by the following example:

And what of Charles? I pity any detective who would have to dog him through those twenty months.

(From The French Lieutenant’s Woman by J. Fowles)

(To dog — to follow or track like a dog, especially with hostile intent.)

The two verbs to ape and to monkey, which might be expected to mean more or less the same, have shared between themselves certain typical features of the same animal:

to ape — to imitate, mimic (e. g. He had always aped the gentleman in his clothes and manners. — J. Fowles);

to monkey — to fool, to act or play idly and foolishly. To monkey can also be used in the meaning «to imitate», but much rarer than to ape.

The following anecdote shows that the intricacies ex semantic associations in words made by conversion may prove somewhat bewildering even for some native-speakers, especially for children.

«Mother», said Johnny, «is it correct to say you ‘water a horse’ when he’s thirsty?»

«Yes, quite correct.»

«Then», (picking up a saucer) «I’m going to milk the cat.»

The joke is based on the child’s mistaken association of two apparently similar patterns: water, п. — to water, v.; milk, n. — to milk, v. But it turns out that the meanings of the two verbs arose from different associations: to water a horse means «to give him water», but to milk implies getting milk from an animal (e. g, to milk a cow).

Exercises

I. Consider your answers to the following.

1. What are the main ways of enriching the English vocabulary?

2. What are the principal productive ways of word-building in English?

3. What do we mean by derivation?

4. What is the difference between frequency and productivity of affixes? Why can’t one consider the noun-forming suffix -age, that is commonly met in many words (cabbage, village, marriage, etc.), a productive one?

5. Give examples of your own to show that affixes have meanings.

6. Look through Chapter 3 and say what languages served as the main sources of borrowed affixes. Illustrate your answer by examples.

7. Prove that the words a finger and to finger («to touch or handle with .the fingers») are two words and not the one word finger used either as a noun or as a verb.

8. What features of Modern English have produced the high productivity of conversion? и

9. Which categories of parts of speech are especially affected by conversion?

10. Prove that the pair of words love, n. and love, v. do not present a case of conversion.

II. The italicized words in the following jokes and extracts are formed by derivation. Write them out in two columns:

A. Those formed with the help of productive affixes.

B. Those formed with the help of non-productive affixes. Explain the etymology of each borrowed affix.

1. Willie was invited to a party, where refreshments were bountifully served.

«Won’t you have something more, Willie?» the hostess said.

«No, thank you,» replied Willie, with an expression of great satisfaction. «I’m full.»

«Well, then,» smiled the hostess, «put some delicious fruit and cakes in your pocket to eat on the way home.»

«No, thank you,» came the rather startling response of Willie, «they’re full too.»

2. The scene was a tiny wayside railway platform and the sun was going down behind the distant hills. It was a glorious sight. An intending passenger was chatting with one of the porters.

«Fine sight, the sun tipping the hills with gold,» said the poetic passenger.

«Yes,» reported the porter; «and to think that there was a time when I was often as lucky as them ‘ills.»

3. A lady who was a very uncertain driver stopped her car at traffic signals which were against her. As the green flashed on, her engine stalled, and when she restarted it the colour was again red. This flurried her so much that when green returned she again stalled her engine and the cars behind began to hoot. While she was waiting for the green the third time the constable on duty stepped across and with a smile said: «Those are the only colours, showing today, ma’am.»

4. «You have an admirable cook, yet you are always growling about her to your friends.»

«Do you suppose I want her lured away?»

5. Patient: Do you extract teeth painlessly?

Dentist: Not always — the other day I nearly dislocated my wrist.

6. The inspector was paying a hurried visit to a slightly overcrowded school.

«Any abnormal children in your class?» he inquired of one harassed-looking teacher.

«Yes,» she replied, with knitted brow, «two of them have good manners.»

7. «I’d like you to come right over,» a man phoned an undertaker, «and supervise the burial of my poor, departed wife.»

«Your wife!» gasped the undertaker. «Didn’t I bury her two years ago?»

«You don’t understand,» said the man. «You see I married again.»

«Oh,» said the undertaker. «Congratulations.»

8. Dear Daddy-Long-Legs.

Please forget about that dreadful letter I sent you last week — I was feeling terribly lonely and miserable and sore-throaty the night I wrote. I didn’t know it, but I was just coming down with tonsillitis and grippe …I’m |b the infirmary now, and have been for six days. The Head nurse is very bossy. She is tall and thinnish with a Hark face and the funniest smile. This is the first time they would let me sit up and have a pen or a pencil. please forgive me for being impertinent and ungrateful.

Yours with love.

Judy Abbott

(From Daddy-Long-Legs by J. Webster)1

9. The residence of Mr. Peter Pett, the well-known financier, on Riverside Drive, New York, is one of the leading eyesores of that breezy and expensive boulevard …Through the rich interior of this mansion Mr. Pett, its nominal proprietor, was wandering like a lost spirit. There was a look of exasperation on his usually patient face. He was afflicted by a sense of the pathos of his position. It was not as if he demanded much from life. At that moment all that he wanted was a quiet spot where he might read his Sunday paper in solitary peace and he could not find one. Intruders lurked behind every door. The place was congested. This sort of thing had been growing worse and worse ever since his marriage two years previously. Marriage had certainly complicated life for Mr. Pett, as it does for the man who waits fifty years before trying it. There was a strong literary virus in Mrs. Pett’s system. She not only wrote voluminously herself — but aimed at maintaining a salon… She gave shelter beneath her terra-cotta roof to no fewer than six young unrecognized geniuses. Six brilliant youths, mostly novelists who had not yet started…

(From Piccadilly Jim by P. G. Wodehouse. Abridged)

III. Write out from any five pages of the book you are reading examples which illustrate borrowed and native affixes in the tables in Ch. 3 and 5. Comment on their productivity.

IV. Explain the etymology and productivity of the affixes given below. Say what parts of speech can be formed with their help.

-ness, -ous, -ly, -y, -dom, -ish, -tion, -ed, -en, -ess, -or, -er, -hood, -less, -ate, -ing, -al, -ful, un-, re-, im (in)-, dis-, over-, ab

V. Write out from the book yon are reading all the words with the adjective-forming suffix -ly and not less than 20 words with the homonymous adverb-forming suffix. Say what these suffixes have in common and in what way they are differentiated.

VI. Deduce the meanings of the following derivatives from the meanings of their constituents. Explain your deduction. What are the meanings of the affixes in the words under examination?

Reddish, ad].; overwrite, v.; irregular, adj.; illegals adj.; retype, v.; old-womanish, adj.; disrespectable, adj.; inexpensive, adj.; unladylike, adj.; disorganize, v.; renew, u.; eatable, adj.; overdress, u.; disinfection, п.; snobbish, adj.; handful, п.; tallish, adj.; sandy, adj.; breakable, adj.; underfed, adj.

VII. In the following examples the italicized words are formed from the same root by means of different affixes. Translate these derivatives into Russian and explain the Difference in meaning.

1. a) Sallie is the most amusing person in the world — and Julia Pendleton the least so. b) Ann was wary, but amused. 2. a) He had a charming smile, almost womanish in sweetness, b) I have kept up with you through Miss Pittypat but she gave me no information that you had developed womanly sweetness. 3. a) I have been having a delightful and entertaining conversation with my old chum, Lord Wisbeach. b) Thanks for your invitation. I’d be delighted to come. 4. a) Sally thinks everything is funny — even flunking — and Julia is bored at everything. She never makes the slightest effort to be pleasant, b) — Why are you going to America? — To make my fortune, I hope. — How pleased your father will be if you do. 5. a) Long before |he reached the brownstone house… the first fine careless rapture of his mad outbreak had passed from Jerry Mitchell, leaving nervous apprehension in its place. b) If your nephew has really succeeded in his experiments you should be awfully careful. 6. a) The trouble with college is that you are expected to know such a lot of things you’ve never learned. It’s very confusing at times. b) That platform was a confused mass of travellers, porters, baggage, trucks, boys with magazines, friends, relatives. 7. a) At last I decided that even this rather mannish efficient woman could do with a little help. b) He was only a boy not a man yet, but he spoke in a manly way. 8. a) The boy’s respectful manner changed noticeably. b) It may be a respectable occupation, but it Sounds rather criminal to me. 9. a) «Who is leading in the pennant race?» said this strange butler in a feverish whisper, b) It was an idea peculiarly suited to her temperament, an idea that she might have suggested her. self if she had thought of it …this idea of his fevered imagination. 10. Dear Daddy-Long-Legs. You only wanted to hear from me once a month, didn’t you? And I’ve been peppering you with letters every few days! But I’ve been so excited about all these new adventures that I must talk to somebody… Speaking of classics, have you ever read Hamlet? If you haven’t, do it right off. It’s perfectly exciting. I’ve been hearing about Shakespeare all my life but I had no idea he really wrote so well, I always suspected him of going largerly on his reputation. (J. Webster)1

VIII. Explain the difference between the meanings of the following words produced from the same root by means of different affixes. Translate the words into Russian.

Watery — waterish, embarrassed — embarrassing. manly — mannish, colourful — coloured, distressed — distressing, respected — respectful — respectable, exhaustive — exhausting — exhausted, bored — boring, touchy — touched — touching.

IX. Find eases of conversion in the following sentences.

1. The clerk was eyeing him expectantly. 2. Under the cover of that protective din he was able to toy with a steaming dish which his waiter had brought. 3. An aggressive man battled his way to Stout’s side. 4. Just a few yards from the front door of the bar there was an elderly woman comfortably seated on a chair, holding a hose linked to a tap and watering the pavement. 5. — What are you doing here? — I’m tidying your room. 6. My seat was in the middle of a row. I could not leave without inconveniencing a great many people, so I remained. 7. How on earth do you remember to milk the cows and give pigs their dinner? 8. In a few minutes Papa stalked off, correctly booted and well mufflered. 9. «Then it’s practically impossible to steal any diamonds?» asked Mrs. Blair with as keen an air of disappointment as though she had been journeying there for the express purpose. 10. Ten minutes later I was Speeding along in the direction of Cape Town. 11. Restaurants in all large cities have their ups and 33owns. 12. The upshot seemed to be that I was left to Пасе life with the sum of £ 87 17s 4d. 13. «A man could Hie very happy in a house like this if he didn’t have to poison his days with work,» said Jimmy. 14. I often heard that fellows after some great shock or loss have a habit, after they’ve been on the floor for a while wondering what hit them, of picking themselves up and piecing themselves together.

X. One of the italicized words in the following examples |!was made from the other by conversion. What semantic correlations exist between them?

1. a) «You’ve got a funny nose,» he added, b) He began to nose about. He pulled out drawer after drawer, pottering round like an old bloodhound. 2. a) I’d seen so many cases of fellows who had become perfect slaves |of their valets, b) I supposed that while he had been valeting old Worplesdon Florence must have trodden on this toes in some way. 3. a) It so happened that the night before I had been present at a rather cheery little supper. b) So the next night I took him along to supper with me. 4. a) Buck seized Thorton’s hand in his teeth. |Ь) The desk clerk handed me the key. 5. a) A small hairy object sprang from a basket and stood yapping in ;the middle of the room. b) There are advantages, you see, about rooming with Julia. 6. a) «I’m engaged for lunch, but I’ve plenty of time.» b) There was a time when he and I had been lads about town together, lunching and dining together practically every day. 7. a) Mr. Biffen rang up on the telephone while you were in your bath. b) I found Muriel singer there, sitting by herself at a table near the door. Corky, I took it, was out telephoning. 8. Use small nails and nail the picture on the wall. 9. a) I could just see that he was waving a letter or something equally foul in my face. b) When the bell stopped. Crane turned around and faced the students seated in rows before him. 10. a) Lizzie is a good cook. b) She cooks the meals in Mr. Priestley’s house. 11. a) The wolf was suspicious and afraid, b) Fortunately, however, the second course consisted of a chicken fricassee of such outstanding excellence that the old boy, after wolfing a plateful, handed up his dinner-pail for a second installment and became almost genial. 12. Use the big hammer for those nails and hammer them in well. 13. a) «Put a ribbon round your hair and be Alice-in-Wonderland,» said Maxim. «You look like it now with your finger in your mouth.» b) The coach fingered the papers on his desk and squinted through his bifocals. 14. a) The room was airy but small. There were, however, a few vacant spots, and in these had been placed a washstand, a chest of drawers and a midget rocker-chair, b) «Well, when I got to New York it looked a decent sort of place to me …» 15. a) These men wanted dog’s, and the dogs they wanted were heavy dogs, with strong muscles… and furry coats to protect them from the frost. b) «Jeeves,» I said, «I have begun to feel absolutely haunted. This woman dog’s me.»

XI. Explain the semantic correlations within the following pairs of words.

Shelter — to shelter, park — to park, groom — to groom, elbow — to elbow, breakfast — to breakfast, pin — to pin, trap — to trap, fish — to fish, head — to head, nurse — to nurse.

XII. Which of the two words in the following pairs is made by conversion? Deduce the meanings and use them in constructing sentences of your own.

|

star, n. — to star, v. picture, n. — to picture, v. colour, n. — to colour, v. blush, n. — to blush, v. key, n. — to key, v. fool, n. — to fool, v. breakfast, n. — to breakfast, v. house, n. — to house, v. monkey, n. — to monkey, v. fork, n. — to fork, v. slice, n. — to slice, v. |

age, n. — to age, v. touch, n. — to touch, v. make, n. — to make, v. finger, n. — to finger, v. empty, adj. — to empty, v. poor, adj. — the poor, n. pale, adj. — to pale, v. dry, adj. — to dry, v. nurse, n. — to nurse, v. dress, n. — to dress, v. floor, n. — to floor, v. |

XIII. Read the following joke, explain the type of word-building in the italicized words and say everything you can about the way they were made.

A successful old lawyer tells the following story about the beginning of his professional life:

«I had just installed myself in my office, had put in a phone, when, through the glass of my door I saw a shadow. It was doubtless my first client to see me. Picture me, then, grabbing the nice, shiny receiver of my new phone and plunging into an imaginary conversation. It ran something like this:

‘Yes, Mr. S!’ I was saying as the stranger entered the office. ‘I’ll attend to that corporation matter for you. Mr. J. had me on the phone this morning and wanted me to settle a damage suit, but I had to put him off, as I was too busy with other cases. But I’ll manage to sandwich your case in between the others somehow. Yes. Yes. All right. Goodbye.’

Being sure, then, that I had duly impressed my prospective client, I hung up the receiver and turned to him.

‘Excuse me, sir,’ the man said, ‘but I’m from the telephone company. I’ve come to connect your instrument.'»

Афанасьева О. В., Морозова Н. Н. А72 Лексикология английского языка: Учеб пособие для студентов. 3-е изд., стереотип

Подобный материал:

- Н. Н. Лексикология английского языка. М.: Высшая школа, 1999. 129 с. Арнольд, 56kb.

- Антрушина Г. Б., Афанасьева О. В., Морозова Н. Н. Лексикология английского языка, 17.18kb.

- Абрамова Г. С. А 16 Возрастная психология: Учеб пособие для студ вузов. 4-е изд., стереотип, 9632.37kb.

- Абрамова Г. С. А 16 Возрастная психология: Учеб пособие для студ вузов. 4-е изд., стереотип, 9632.44kb.

- Абрамова Г. С. А 16 Возрастная психология: Учеб пособие для студ вузов. 4-е изд., стереотип, 9728.34kb.

- Рабочая программа дисциплины лексикология современного английского языка наименование, 245.25kb.

- Программа дисциплины опд. Ф. 02. 3 Лексикология английского языка, 112.16kb.

- Владимира Дмитриевича Аракина одного из замечательных лингвистов России предисловие, 3598.08kb.

- Торговля и денежное обращение 22 Вопросы для повторения, 30.43kb.

- Антонов А. И., Медков В. М. А72 Социология семьи, 4357.97kb.

How English Words Are Made. Word-Building1

Before turning to the various processes of making words, it would be useful to analyse the related problem of the composition of words, i. e. of their constituent parts.

If viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units which are called morphemes. Morphemes do not occur as free forms but only as constituents of words. Yet they possess meanings of their own.

All morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots (or radicals} and affixes. The latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes which precede the root in the structure of the word (as in re-read, mis-pronounce, un-well) and suffixes which follow the root (as in teach-er, cur-able, diet-ate).

Words which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word-building known as affixation (or derivation).

Derived words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary. Successfully competing with this structural type is the so-called root word which has only a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by a great number of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier borrowings (house, room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.), and, in Modern English, has been greatly enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion (e. g. to hand, v. formed from the noun hand; to can, v. from can, п.; to pale, v. from pale, adj.; a find, n. from to find, v.; etc.).

Another wide-spread word-structure is a compound word consisting of two or more stems2 (e. g. dining-room, bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing). Words of this structural type are produced by the word-building process called composition.

The somewhat odd-looking words like flu, pram, lab, M. P., V-day, H-bomb are called shortenings, contractions or curtailed words and are produced by the way of word-building called shortening (contraction).

The four types (root words, derived words, compounds, shortenings) represent the main structural types of Modern English words, and conversion, derivation and composition the most productive ways of word-building.

To return to the question posed by the title of this chapter, of how words are made, let us try and get a more detailed picture of each of the major types of Modern English word-building and, also, of some minor types.

Affixation

The process of affixation consists in coining a new word by adding an affix or several affixes to some root morpheme. The role of the affix in this procedure is Very important and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the main types of affixes.

From the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same two large groups as words: native and borrowed.

Some Native Suffixes1

|

Noun-forming |

-er | worker, miner, teacher, painter, etc. |

| -ness | coldness, loneliness, loveliness, etc. | |

| -ing | feeling, meaning, singing, reading, etc. | |

| -dom | freedom, wisdom, kingdom, etc. | |

| -hood | childhood, manhood, motherhood, etc. | |

| -ship | friendship, companionship, mastership, etc. | |

| -th | length, breadth, health, truth, etc. | |

|

Adjective-forming |

-ful | careful, joyful, wonderful, sinful, skilful, etc. |

| -less | careless, sleepless, cloudless, senseless, etc. | |

| -y | cozy, tidy, merry, snowy, showy, etc. | |

| -ish | English, Spanish, reddish, childish, etc. | |

| -ly | lonely, lovely, ugly, likely, lordly, etc. | |

| -en | wooden, woollen, silken, golden, etc. | |

| -some | handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome, etc. | |

| Verb-forming | -en | widen, redden, darken, sadden, etc. |

| Adverb-forming | -ly | warmly, hardly, simply, carefully, coldly, etc. |

Borrowed affixes, especially of Romance origin are numerous in the English vocabulary (Ch. 3). It would be wrong, though, to suppose that affixes are borrowed in the same way and for the same reasons as words. An affix of foreign origin can be regarded as borrowed only after it has begun an independent and active life in the recipient language, that is, is taking part in the word-making processes of that language. This can only occur when the total of words with this affix is so great in the recipient language as to affect the native speakers’ subconscious to the extent that they no longer realize its foreign flavour and accept it as their own.

* * *

Affixes can also be classified into productive and non-productive types. By productive affixes we mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in this particular period of language development. The best way to identify productive affixes is to look for them among neologisms and so-called nonce-words, i. e. words coined and used only for this particular occasion. The latter are usually formed on the level of living speech and reflect the most productive and progressive patterns in word-building. When a literary critic writes about a certain book that it is an unputdownable thriller, we will seek in vain this strange and impressive adjective in dictionaries, for it is a nonce-Word coined on the current pattern of Modern English and is evidence of the high productivity of the adjective-forming borrowed suffix -able and the native prefix un-.

Consider, for example, the following:

Professor Pringle was a thinnish, baldish, dispeptic-lookingish cove with an eye like a haddock.

(From Right-Ho, Jeeves by P. G. Wodehouse)

The adjectives thinnish and baldish bring to mind dozens of other adjectives made with the same suffix; oldish, youngish, mannish, girlish, fattish, longish, yellowish, etc. But dispeptic-lookingish is the author’s creation aimed at a humorous effect, and, at the same time, proving beyond doubt that the suffix -ish is a live and active one.

The same is well illustrated by the following popular statement: «I don’t like Sunday evenings: I feel so Mondayish». (Mondayish is certainly a nonce-word.)

One should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency of occurrence. There are quite & number of high-frequency affixes which, nevertheless, are no longer used in word-derivation (e. g. the adjective-forming native suffixes -ful, -ly; the adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin -ant, -ent, -al which are quite frequent).

Some Productive Affixes

| Noun-forming suffixes | —er, -ing, -ness, -ism1 (materialism), -ist1 (impressionist), -ance |

| Adjective-forming suffixes | -y, -ish, -ed (learned), -able, -less |

| Adverb-forming suffixes | -ly |

| Verb-forming suffixes | -ize/-ise (realize), -ate |

| Prefixes | un- (unhappy), re- (reconstruct), dis- (disappoint) |

Note. Examples are given only for the affixes which are not listed in the tables at p. 82 and p. 83.

Some Non-Productive Affixes

| Noun-forming suffixes | -th,-hood |

| Adjective-forming suffixes | -ly, -some, -en, -ous |

| Verb-forming suffix | -en |

Note. The native noun-forming suffixes -dom and -ship ceased to be productive centuries ago. Yet, Professor I. V. Arnold in The English Word gives some examples of comparatively new formations with the suffix -dom: boredom, serfdom, slavedom [15]. The same is true about -ship (e. g- salesmanship). The adjective-forming -ish, which leaves no doubt as to its productivity nowadays, has comparatively recently regained it, after having been non-productive for many centuries.

Semantics of Affixes

The morpheme, and therefore affix, which is a type of morpheme, is generally defined as the smallest indivisible component of the word possessing a meaning of its own. Meanings of affixes are specific and considerably differ from those of root morphemes. Affixes have widely generalized meanings and refer the concept conveyed by the whole word to a certain category, which is vast and all-embracing. So, the noun-forming suffix -er could be roughly defined as designating persons from the object of their occupation or labour (painter — the one who paints) or from their place of origin or abode {southerner — the one living in the South). The adjective-forming suffix -ful has the meaning of «full of», «characterized by» (beautiful, careful) whereas -ish Olay often imply insufficiency of quality (greenish — green, but not quite; youngish — not quite young but looking it).

Such examples might lead one to the somewhat hasty conclusion that the meaning of a derived word is always a sum of the meanings of its morphemes: un/eat/able =» «not fit to eat» where not stands for un- and fit for: -able.

There are numerous derived words whose meanings can really be easily deduced from the meanings of their constituent parts. Yet, such cases represent only the first and simplest stage of semantic readjustment with in derived words. The constituent morphemes within derivatives do not always preserve their current meanings and are open to subtle and complicated semantic shifts.

Let us take at random some of the adjectives formed with the same productive suffix -y, and try to deduce the meaning of the suffix from their dictionary definitions:

brainy (inform.) — intelligent, intellectual, i. e, characterized by brains

catty — quietly or slyly malicious, spiteful, i. e, characterized by features ascribed to a cat

chatty — given to chat, inclined to chat

dressy (inform.) — showy in dress, i. e. inclined to dress well or to be overdressed

fishy (e. g. in a fishy story, inform.) — improbable, hard to believe (like stories told by fishermen)

foxy — foxlike, cunning or crafty, i. e. characterized by features ascribed to a fox

stagy — theatrical, unnatural, i. e. inclined to affectation, to unnatural theatrical manners

touchy — apt to take offence on slight provocation, i. e. resenting a touch or contact (not at all inclined to be touched)1

The Random-House Dictionary defines the meaning of the -y suffix as «characterized by or inclined to the substance or action of the root to which the affix is attached». [46] Yet, even the few given examples show that, on the one hand, there are cases, like touchy or fishy that are not covered by the definition. On the other hand, even those cases that are roughly covered, show a wide variety of subtle shades of meaning. It is not only the suffix that adds its own meaning to the meaning of the root, but the suffix is, in its turn, affected by the root and undergoes certain semantic changes, so that the mutual influence of root and affix creates a wide range of subtle nuances.

But is the suffix -y probably exceptional in this respect? It is sufficient to examine further examples to see that other affixes also offer an interesting variety of semantic shades. Compare, for instance, the meanings of adjective-forming suffixes in each of these groups of adjectives.

1. eatable (fit or good to eat)2

lovable (worthy of loving)

questionable (open to doubt, to question)

imaginable (capable of being imagined)

2. lovely (charming, beautiful, i. e. inspiring love)

lonely (solitary, without company; lone; the meaning of the suffix does not seem to add anything to that of the root)

friendly (characteristic of or befitting a friend.)

heavenly (resembling or befitting heaven; beautiful, splendid)

3. childish (resembling or befitting a child)

tallish (rather tall, but not quite, i. e. approaching the quality of big size)

girlish (like a girl, but, often, in a bad imitation of one)

bookish (1) given or devoted to reading or study;

(2) more acquainted with books than with real life, i. e. possessing the quality of bookish learning)

The semantic distinctions of words produced from the same root by means of different affixes are also of considerable interest, both for language studies and research work. Compare: womanly — womanish, flowery — flowered -— flowering, starry — starred, reddened — reddish, shortened — shortish.

The semantic difference between the members of these groups is very obvious: the meanings of the suffixes are so distinct that they colour the whole words.

Womanly is used in a complimentary manner about girls and women, whereas womanish is used to indicate an effeminate man and certainly implies criticism.

Flowery is applied to speech or a style (cf. with the R. цветистый), flowered means «decorated with a patters of flowers» (e. g. flowered silk or chintz, cf. with the R, цветастый) and flowering is the same as blossoming (e. g. flowering bushes or shrubs, cf. with the R. цветущий).

Starry means «resembling stars» (e. g. starry eyes) and starred — «covered or decorated with stars» (e. g. starred skies).

Reddened and shortened both imply the result of an action or process, as in the eyes reddened with weeping or a shortened version of a story (i. e. a story that has been abridged) whereas shortish and reddish point to insufficiency of quality: reddish is not exactly red, but tinged with red, and a shortish man is probably a little taller than a man described as short.

Conversion

When in a book-review a book is referred to as a splendid read, is read to be regarded as a verb or a noun? What part of speech is room in the sentence: I was to room with another girl called Jessie. If a character in a novel is spoken about as one who had to be satisfied with the role of a has-been, what is this odd-looking has-been, a verb or a noun? One must admit that it has quite a verbal appearance, but why, then, is it preceded by the article?

Why is the word if used in the plural form in the popular proverb: If ifs and ans were pots and pans? (an = if, dial., arch.)

This type of questions naturally arise when one deals with words produced by conversion, one of the most productive ways of modern English word-building.

Conversion is sometimes referred to as an affixless way of word-building or even affixless derivation. Saying that, however, is saying very little because there are other types of word-building in which new words are also formed without affixes (most compounds, contracted words, sound-imitation words, etc.).

Conversion consists in making a new word from some existing word by changing the category of a part of speech, the morphemic shape of the original word remaining unchanged. The new word has a meaning Which differs from that of the original one though it can more or less be easily associated with it. It has also a new paradigm peculiar to its new category as a part of speech.

The question of conversion has, for a long time, been a controversial one in several aspects. The very essence of this process has been treated by a number of scholars (e. g. H. Sweet), not as a word-building act, but as a mere functional change. From this point of view the word hand in Hand me that book is not a verb, but a noun used in a verbal syntactical function, that is, hand (me) and hands (in She has small hands) are not two different words but one. Hence, the case cannot be treated as one of word-formation for no new word appears.

According to this functional approach, conversion may be regarded as a specific feature of the English categories of parts of speech, which are supposed to be able to break through the rigid borderlines dividing one category from another thus enriching the process of communication not by the creation of new words but through the sheer flexibility of the syntactic structures.

Nowadays this theory finds increasingly fewer supporters, and conversion is universally accepted as one of the major ways of enriching English vocabulary with new words. One of the major arguments for this approach to conversion is the semantic change that regularly accompanies each instance of conversion. Normally, a word changes its syntactic function without any shift in lexical meaning. E. g. both in yellow leaves and in The leaves were turning yellow the adjective denotes colour. Yet, in The leaves yellowed the converted unit no longer denotes colour, but the process of changing colour, so that there is an essential change in meaning.

The change of meaning is even more obvious in such pairs as hand > to hand, face > to face, to go > a go, to make > a make, etc.

The other argument is the regularity and completeness with which converted units develop a paradigm of their new category of part of speech. As soon as it has crossed the category borderline, the new word automatically acquires all the properties of the new category, so that if it has entered the verb category, it is now regularly used in all the forms of tense and it also develops the forms of the participle and the gerund. Such regularity can hardly be regarded as indicating a mere functional change which might be expected to bear more occasional characteristics. The completeness of the paradigms in new conversion formations seems to be a decisive argument proving that here we are dealing with new words and not with mere functional variants. The data of the more reputable modern English dictionaries confirm this point of view: they all present converted pairs as homonyms, i. e. as two words, thus supporting the thesis that conversion is a word-building process.

Conversion is not only a highly productive but also a particularly English way of word-building. Its immense productivity is considerably encouraged by certain features of the English language in its modern Stage of development. The analytical structure of Modern English greatly facilitates processes of making words of one category of parts of speech from words of another. So does the simplicity of paradigms of En-lush parts of speech. A great number of one-syllable Words is another factor in favour of conversion, for such words are naturally more mobile and flexible than polysyllables.

Conversion is a convenient and «easy» way of enriching the vocabulary with new words. It is certainly an advantage to have two (or more) words where there Was one, all of them fixed on the same structural and semantic base.

The high productivity of conversion finds its reflection in speech where numerous occasional cases of conversion can be found, which are not registered by dictionaries and which occur momentarily, through the immediate need of the situation. «If anybody oranges me again tonight, I’ll knock his face off, says the annoyed hero of a story by O’Henry when a shop-assistant offers him oranges (for the tenth time in one night) instead of peaches for which he is looking («Lit. tie Speck in Garnered Fruit»). One is not likely to find the verb to orange in any dictionary, but in this situation it answers the need for brevity, expressiveness and humour.

The very first example, which opens the section on conversion in this chapter (the book is a splendid read), though taken from a book-review, is a nonce-word, which may be used by reviewers now and then or in informal verbal communication, but has not yet found its way into the universally acknowledged English vocabulary.

Such examples as these show that conversion is a vital and developing process that penetrates contemporary speech as well. Subconsciously every English speaker realizes the immense potentiality of making a word into another part of speech when the need arises.

* * *

One should guard against thinking that every case of noun and verb (verb and adjective, adjective and noun, etc.) with the same morphemic shape results from conversion. There are numerous pairs of words (e. g. love, n. — to love, v.; work, n. — to work, v.; drink, n. — to drink, v., etc.) which did, not occur due to conversion but coincided as a result of certain historical processes (dropping of endings, simplification of stems) when before that they had different forms (e. g. O. E. lufu, n. — lufian, v.). On the other hand, it is quite true that the first cases of conversion (which were registered in the 14th c.) imitated such pairs of words as love, n. — to love, v. for they were numerous to the vocabulary and were subconsciously accepted by native speakers as one of the typical language patterns.

* * *

The two categories of parts of speech especially affected by conversion are nouns and verbs. Verbs made from nouns are the most numerous amongst the words produced by conversion: e. g. to hand, to back, to face, to eye, to mouth, to nose, to dog, to wolf, to monkey, to can, to coal, to stage, to screen, to room, to floor, to lack-mail, to blacklist, to honeymoon, and very many ethers.

Nouns are frequently made from verbs: do (e. g. This ifs the queerest do I’ve ever come across. Do — event, incident), go (e. g. He has still plenty of go at his age. Go — energy), make, run, find, catch, cut, walk, worry, show, move, etc.

Verbs can also be made from adjectives: to pale, to yellow, to cool, to grey, to rough (e. g. We decided sq rough it in the tents as the weather was warm), etc.

Other parts of speech are not entirely unsusceptible to conversion as the following examples show: to down, to out (as in a newspaper heading Diplomatist Outed from Budapest), the ups and downs, the ins and outs, like, n. (as in the like of me and the like of you).

* * *

It was mentioned at the beginning of this section that a word made by conversion has a different meaning from that of the word from which it was made though the two meanings can be associated. There are Certain regularities in these associations which can be roughly classified. For instance, in the group of verbs made from nouns some of the regular semantic associations are as indicated in the following list:

I. The noun is the name of a tool or implement, the verb denotes an action performed by the tool: to hammer, to nail, to pin, to brush, to comb, to pencil.

II. The noun is the name of an animal, the verb denotes an action or aspect of behaviour considered typical of this animal: to dog, to wolf, to monkey, to ape, to fox, to rat. Yet, to fish does not mean «to behave like a fish» but «to try to catch fish». The same meaning of hunting activities is conveyed by the verb to whale and one of the meanings of to rat; the other is «to turn informer, squeal» (sl.).

III. The name of a part of the human body — an action performed by it: to hand, to leg (sl.), to eye, to elbow, to shoulder, to nose, to mouth. However, to face does not imply doing something by or even with one’s face but turning it in a certain direction. To back means either «to move backwards» or, in the figurative sense, «to support somebody or something».

IV. The name of a profession or occupation — an activity typical of it: to nurse, to cook, to maid, to groom.

V. The name of a place — the process of occupying» the place or of putting smth./smb. in it (to room, to house, to place, to table, to cage).

VI. The name of a container — the act of putting smth. within the container (to can, to bottle, to pocket).

VII. The name of a meal — the process of taking it (to lunch, to supper).

The suggested groups do not include all the great variety of verbs made from nouns by conversion. They just represent the most obvious cases and illustrate, convincingly enough, the great variety of semantic interrelations within so-called converted pairs and the complex nature of the logical associations which specify them.

In actual fact, these associations are not only complex but sometimes perplexing. It would seem that if you know that the verb formed from the name of an animal denotes behaviour typical of the animal, it would easy for you to guess the meaning of such a verb provided that you know the meaning of the noun. Yet, it is not always easy. Of course, the meaning of to fox is rather obvious being derived from the associated reputation of that animal for cunning: to fox means «to act cunningly or craftily». But what about to wolf? How is one to know which of the characteristics of the animal was picked by the speaker’s subconscious when this verb was produced? Ferocity? Loud and unpleasant fowling? The inclination to live in packs? Yet, as the Hollowing example shows, to wolf means «to eat greedily, voraciously»: Charlie went on wolfing the chocolate. (R. Dahl)

In the same way, from numerous characteristics of | be dog, only one was chosen for the verb to dog which is well illustrated by the following example: