Lecture №3. Productive and Non-productive Ways of Word-formation in Modern English

Productivity is the ability to form new words after existing patterns which are readily understood by the speakers of language. The most important and the most productive ways of word-formation are affixation, conversion, word-composition and abbreviation (contraction). In the course of time the productivity of this or that way of word-formation may change. Sound interchange or gradation (blood-to bleed, to abide-abode, to strike-stroke) was a productive way of word building in old English and is important for a diachronic study of the English language. It has lost its productivity in Modern English and no new word can be coined by means of sound gradation. Affixation on the contrary was productive in Old English and is still one of the most productive ways of word building in Modern English.

WORDBUILDING

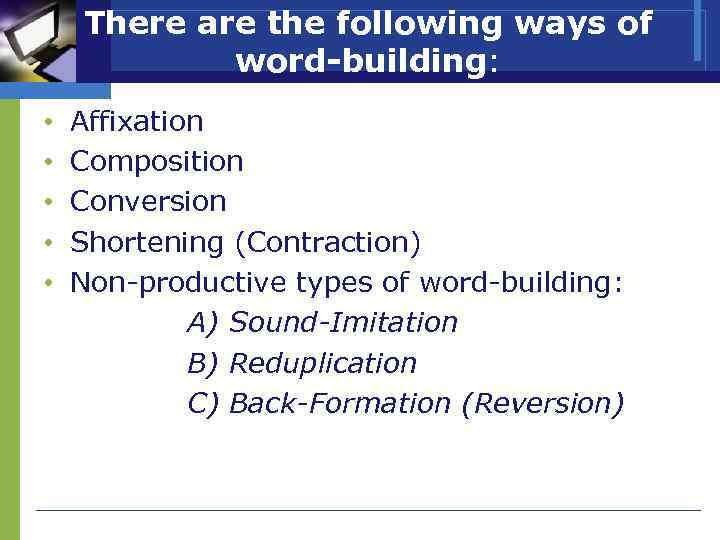

Word-building is one of the main ways of enriching vocabulary. There are four main ways of word-building in modern English: affixation, composition, conversion, abbreviation. There are also secondary ways of word-building: sound interchange, stress interchange, sound imitation, blends, back formation.

AFFIXATION

Affixation is one of the most productive ways of word-building throughout the history of English. It consists in adding an affix to the stem of a definite part of speech. Affixation is divided into suffixation and prefixation.

Suffixation

The main function of suffixes in Modern English is to form one part of speech from another, the secondary function is to change the lexical meaning of the same part of speech. (e.g. «educate» is a verb, «educator» is a noun, and music» is a noun, «musical» is also a noun or an adjective). There are different classifications of suffixes :

1. Part-of-speech classification. Suffixes which can form different parts of speech are given here :

a) noun-forming suffixes, such as: —er (criticizer), —dom (officialdom), —ism (ageism),

b) adjective-forming suffixes, such as: —able (breathable), less (symptomless), —ous (prestigious),

c) verb-forming suffixes, such as —ize (computerize) , —ify (minify),

d) adverb-forming suffixes , such as : —ly (singly), —ward (tableward),

e) numeral-forming suffixes, such as —teen (sixteen), —ty (seventy).

2. Semantic classification. Suffixes changing the lexical meaning of the stem can be subdivided into groups, e.g. noun-forming suffixes can denote:

a) the agent of the action, e.g. —er (experimenter), —ist (taxist), -ent (student),

b) nationality, e.g. —ian (Russian), —ese (Japanese), —ish (English),

c) collectivity, e.g. —dom (moviedom), —ry (peasantry, —ship (readership), —ati (literati),

d) diminutiveness, e.g. —ie (horsie), —let (booklet), —ling (gooseling), —ette (kitchenette),

e) quality, e.g. —ness (copelessness), —ity (answerability).

3. Lexico—grammatical character of the stem. Suffixes which can be added to certain groups of stems are subdivided into:

a) suffixes added to verbal stems, such as: —er (commuter), —ing (suffering), — able (flyable), —ment (involvement), —ation (computerization),

b) suffixes added to noun stems, such as: —less (smogless), —ful (roomful), —ism (adventurism), —ster (pollster), —nik (filmnik), —ish (childish),

c) suffixes added to adjective stems, such as: —en (weaken), —ly (pinkly), —ish (longish), —ness (clannishness).

4. Origin of suffixes. Here we can point out the following groups:

a) native (Germanic), such as —er,-ful, —less, —ly.

b) Romanic, such as : —tion, —ment, —able, —eer.

c) Greek, such as : —ist, —ism, -ize.

d) Russian, such as —nik.

5. Productivity. Here we can point out the following groups:

a) productive, such as: —er, —ize, —ly, —ness.

b) semi-productive, such as: —eer, —ette, —ward.

c) non-productive , such as: —ard (drunkard), —th (length).

Suffixes can be polysemantic, such as: —er can form nouns with the following meanings: agent, doer of the action expressed by the stem (speaker), profession, occupation (teacher), a device, a tool (transmitter). While speaking about suffixes we should also mention compound suffixes which are added to the stem at the same time, such as —ably, —ibly, (terribly, reasonably), —ation (adaptation from adapt). There are also disputable cases whether we have a suffix or a root morpheme in the structure of a word, in such cases we call such morphemes semi-suffixes, and words with such suffixes can be classified either as derived words or as compound words, e.g. —gate (Irangate), —burger (cheeseburger), —aholic (workaholic) etc.

Prefixation

Prefixation is the formation of words by means of adding a prefix to the stem. In English it is characteristic for forming verbs. Prefixes are more independent than suffixes. Prefixes can be classified according to the nature of words in which they are used: prefixes used in notional words and prefixes used in functional words. Prefixes used in notional words are proper prefixes which are bound morphemes, e.g. un— (unhappy). Prefixes used in functional words are semi-bound morphemes because they are met in the language as words, e.g. over— (overhead) (cf. over the table). The main function of prefixes in English is to change the lexical meaning of the same part of speech. But the recent research showed that about twenty-five prefixes in Modern English form one part of speech from another (bebutton, interfamily, postcollege etc).

Prefixes can be classified according to different principles:

1. Semantic classification:

a) prefixes of negative meaning, such as: in— (invaluable), non— (nonformals), un— (unfree) etc,

b) prefixes denoting repetition or reversal actions, such as: de— (decolonize), re— (revegetation), dis— (disconnect),

c) prefixes denoting time, space, degree relations, such as: inter— (interplanetary) , hyper— (hypertension), ex— (ex-student), pre— (pre-election), over— (overdrugging) etc.

2. Origin of prefixes:

a) native (Germanic), such as: un-, over-, under— etc.

b) Romanic, such as: in-, de-, ex-, re— etc.

c) Greek, such as: sym-, hyper— etc.

When we analyze such words as adverb, accompany where we can find the root of the word (verb, company) we may treat ad-, ac— as prefixes though they were never used as prefixes to form new words in English and were borrowed from Romanic languages together with words. In such cases we can treat them as derived words. But some scientists treat them as simple words. Another group of words with a disputable structure are such as: contain, retain, detain and conceive, receive, deceive where we can see that re-, de-, con— act as prefixes and —tain, —ceive can be understood as roots. But in English these combinations of sounds have no lexical meaning and are called pseudo-morphemes. Some scientists treat such words as simple words, others as derived ones. There are some prefixes which can be treated as root morphemes by some scientists, e.g. after— in the word afternoon. American lexicographers working on Webster dictionaries treat such words as compound words. British lexicographers treat such words as derived ones.

COMPOSITION

Composition is the way of word building when a word is formed by joining two or more stems to form one word. The structural unity of a compound word depends upon: a) the unity of stress, b) solid or hyphеnated spelling, c) semantic unity, d) unity of morphological and syntactical functioning. These are characteristic features of compound words in all languages. For English compounds some of these factors are not very reliable. As a rule English compounds have one uniting stress (usually on the first component), e.g. hard-cover, best—seller. We can also have a double stress in an English compound, with the main stress on the first component and with a secondary stress on the second component, e.g. blood—vessel. The third pattern of stresses is two level stresses, e.g. snow—white, sky—blue. The third pattern is easily mixed up with word-groups unless they have solid or hyphеnated spelling.

Spelling in English compounds is not very reliable as well because they can have different spelling even in the same text, e.g. war—ship, blood—vessel can be spelt through a hyphen and also with a break, insofar, underfoot can be spelt solidly and with a break. All the more so that there has appeared in Modern English a special type of compound words which are called block compounds, they have one uniting stress but are spelt with a break, e.g. air piracy, cargo module, coin change, penguin suit etc. The semantic unity of a compound word is often very strong. In such cases we have idiomatic compounds where the meaning of the whole is not a sum of meanings of its components, e.g. to ghostwrite, skinhead, brain—drain etc. In nonidiomatic compounds semantic unity is not strong, e. g., airbus, to bloodtransfuse, astrodynamics etc.

English compounds have the unity of morphological and syntactical functioning. They are used in a sentence as one part of it and only one component changes grammatically, e.g. These girls are chatter-boxes. «Chatter-boxes» is a predicative in the sentence and only the second component changes grammatically. There are two characteristic features of English compounds:

a) Both components in an English compound are free stems, that is they can be used as words with a distinctive meaning of their own. The sound pattern will be the same except for the stresses, e.g. «a green-house» and «a green house». Whereas for example in Russian compounds the stems are bound morphemes, as a rule.

b) English compounds have a two-stem pattern, with the exception of compound words which have form-word stems in their structure, e.g. middle-of-the-road, off—the—record, up—and—doing etc. The two-stem pattern distinguishes English compounds from German ones.

WAYS OF FORMING COMPOUND WORDS

Compound words in English can be formed not only by means of composition but also by means of:

a) reduplication, e.g. too—too, and also by means of reduplication combined with sound interchange , e.g. rope-ripe,

b) conversion from word-groups, e.g. to micky—mouse, can—do, makeup etc,

c) back formation from compound nouns or word-groups, e.g. to bloodtransfuse, to fingerprint etc ,

d) analogy, e.g. lie—in (on the analogy with sit-in) and also phone—in, brawn—drain (on the analogy with brain—drain) etc.

CLASSIFICATIONS OF ENGLISH COMPOUNDS

1. According to the parts of speech compounds are subdivided into:

a) nouns, such as: baby-moon, globe-trotter,

b) adjectives, such as : free-for-all, power-happy,

c) verbs, such as : to honey-moon, to baby-sit, to henpeck,

d) adverbs, such as: downdeep, headfirst,

e) prepositions, such as: into, within,

f) numerals, such as : fifty—five.

2. According to the way components are joined together compounds are divided into: a) neutral, which are formed by joining together two stems without any joining morpheme, e.g. ball—point, to windowshop,

b) morphological where components are joined by a linking element: vowels «o» or «i» or the consonant «s», e.g. («astrospace», «handicraft», «sportsman»),

c) syntactical where the components are joined by means of form-word stems, e.g. here-and-now, free-for-all, do-or-die.

3. According to their structure compounds are subdivided into:

a) compound words proper which consist of two stems, e.g. to job-hunt, train-sick, go-go, tip-top,

b) derivational compounds, where besides the stems we have affixes, e.g. ear—minded, hydro-skimmer,

c) compound words consisting of three or more stems, e.g. cornflower—blue, eggshell—thin, singer—songwriter,

d) compound-shortened words, e.g. boatel, VJ—day, motocross, intervision, Eurodollar, Camford.

4. According to the relations between the components compound words are subdivided into:

a) subordinative compounds where one of the components is the semantic and the structural centre and the second component is subordinate; these subordinative relations can be different: with comparative relations, e.g. honey—sweet, eggshell—thin, with limiting relations, e.g. breast—high, knee—deep, with emphatic relations, e.g. dog—cheap, with objective relations, e.g. gold—rich, with cause relations, e.g. love—sick, with space relations, e.g. top—heavy, with time relations, e.g. spring—fresh, with subjective relations, e.g. foot—sore etc

b) coordinative compounds where both components are semantically independent. Here belong such compounds when one person (object) has two functions, e.g. secretary-stenographer, woman-doctor, Oxbridge etc. Such compounds are called additive. This group includes also compounds formed by means of reduplication, e.g. fifty-fifty, no-no, and also compounds formed with the help of rhythmic stems (reduplication combined with sound interchange) e.g. criss-cross, walkie-talkie.

5. According to the order of the components compounds are divided into compounds with direct order, e.g. kill—joy, and compounds with indirect order, e.g. nuclear—free, rope—ripe.

CONVERSION

Conversion is a characteristic feature of the English word-building system. It is also called affixless derivation or zero-suffixation. The term «conversion» first appeared in the book by Henry Sweet «New English Grammar» in 1891. Conversion is treated differently by different scientists, e.g. prof. A.I. Smirntitsky treats conversion as a morphological way of forming words when one part of speech is formed from another part of speech by changing its paradigm, e.g. to form the verb «to dial» from the noun «dial» we change the paradigm of the noun (a dial, dials) for the paradigm of a regular verb (I dial, he dials, dialed, dialing). A. Marchand in his book «The Categories and Types of Present-day English» treats conversion as a morphological-syntactical word-building because we have not only the change of the paradigm, but also the change of the syntactic function, e.g. I need some good paper for my room. (The noun «paper» is an object in the sentence). I paper my room every year. (The verb «paper» is the predicate in the sentence). Conversion is the main way of forming verbs in Modern English. Verbs can be formed from nouns of different semantic groups and have different meanings because of that, e.g.:

a) verbs have instrumental meaning if they are formed from nouns denoting parts of a human body e.g. to eye, to finger, to elbow, to shoulder etc. They have instrumental meaning if they are formed from nouns denoting tools, machines, instruments, weapons, e.g. to hammer, to machine-gun, to rifle, to nail,

b) verbs can denote an action characteristic of the living being denoted by the noun from which they have been converted, e.g. to crowd, to wolf, to ape,

c) verbs can denote acquisition, addition or deprivation if they are formed from nouns denoting an object, e.g. to fish, to dust, to peel, to paper,

d) verbs can denote an action performed at the place denoted by the noun from which they have been converted, e.g. to park, to garage, to bottle, to corner, to pocket,

e) verbs can denote an action performed at the time denoted by the noun from which they have been converted e.g. to winter, to week-end.

Verbs can be also converted from adjectives, in such cases they denote the change of the state, e.g. to tame (to become or make tame), to clean, to slim etc.

Nouns can also be formed by means of conversion from verbs. Converted nouns can denote: a) instant of an action e.g. a jump, a move,

b) process or state e.g. sleep, walk,

c) agent of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e.g. a help, a flirt, a scold,

d) object or result of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e.g. a burn, a find, a purchase,

e) place of the action expressed by the verb from which the noun has been converted, e.g. a drive, a stop, a walk.

Many nouns converted from verbs can be used only in the Singular form and denote momentaneous actions. In such cases we have partial conversion. Such deverbal nouns are often used with such verbs as: to have, to get, to take etc., e.g. to have a try, to give a push, to take a swim.

CRITERIA OF SEMANTIC DERIVATION

In cases of conversion the problem of criteria of semantic derivation arises: which of the converted pair is primary and which is converted from it. The problem was first analized by prof. A.I. Smirnitsky. Later on P.A. Soboleva developed his idea and worked out the following criteria:

1. If the lexical meaning of the root morpheme and the lexico-grammatical meaning of the stem coincide the word is primary, e.g. in cases pen — to pen, father — to father the nouns are names of an object and a living being. Therefore in the nouns «pen» and «father» the lexical meaning of the root and the lexico-grammatical meaning of the stem coincide. The verbs «to pen» and «to father» denote an action, a process therefore the lexico-grammatical meanings of the stems do not coincide with the lexical meanings of the roots. The verbs have a complex semantic structure and they were converted from nouns.

2. If we compare a converted pair with a synonymic word pair which was formed by means of suffixation we can find out which of the pair is primary. This criterion can be applied only to nouns converted from verbs, e.g. «chat» n. and «chat» v. can be compared with «conversation» – «converse».

3. The criterion based on derivational relations is of more universal character. In this case we must take a word-cluster of relative words to which the converted pair belongs. If the root stem of the word-cluster has suffixes added to a noun stem the noun is primary in the converted pair and vica versa, e.g. in the word-cluster: hand n., hand v., handy, handful the derived words have suffixes added to a noun stem, that is why the noun is primary and the verb is converted from it. In the word-cluster: dance n., dance v., dancer, dancing we see that the primary word is a verb and the noun is converted from it.

SUBSTANTIVIZATION OF ADJECTIVES

Some scientists (Yespersen, Kruisinga) refer substantivization of adjectives to conversion. But most scientists disagree with them because in cases of substantivization of adjectives we have quite different changes in the language. Substantivization is the result of ellipsis (syntactical shortening) when a word combination with a semantically strong attribute loses its semantically weak noun (man, person etc), e.g. «a grown-up person» is shortened to «a grown-up». In cases of perfect substantivization the attribute takes the paradigm of a countable noun, e.g. a criminal, criminals, a criminal’s (mistake), criminals’ (mistakes). Such words are used in a sentence in the same function as nouns, e.g. I am fond of musicals. (musical comedies). There are also two types of partly substantivized adjectives: 1) those which have only the plural form and have the meaning of collective nouns, such as: sweets, news, finals, greens; 2) those which have only the singular form and are used with the definite article. They also have the meaning of collective nouns and denote a class, a nationality, a group of people, e.g. the rich, the English, the dead.

«STONE WALL» COMBINATIONS

The problem whether adjectives can be formed by means of conversion from nouns is the subject of many discussions. In Modern English there are a lot of word combinations of the type, e.g. price rise, wage freeze, steel helmet, sand castle etc. If the first component of such units is an adjective converted from a noun, combinations of this type are free word-groups typical of English (adjective + noun). This point of view is proved by O. Yespersen by the following facts:

1. «Stone» denotes some quality of the noun «wall».

2. «Stone» stands before the word it modifies, as adjectives in the function of an attribute do in English.

3. «Stone» is used in the Singular though its meaning in most cases is plural, and adjectives in English have no plural form.

4. There are some cases when the first component is used in the Comparative or the Superlative degree, e.g. the bottomest end of the scale.

5. The first component can have an adverb which characterizes it, and adjectives are characterized by adverbs, e.g. a purely family gathering.

6. The first component can be used in the same syntactical function with a proper adjective to characterize the same noun, e.g. lonely bare stone houses.

7. After the first component the pronoun «one» can be used instead of a noun, e.g. I shall not put on a silk dress, I shall put on a cotton one.

However Henry Sweet and some other scientists say that these criteria are not characteristic of the majority of such units. They consider the first component of such units to be a noun in the function of an attribute because in Modern English almost all parts of speech and even word-groups and sentences can be used in the function of an attribute, e.g. the then president (an adverb), out-of-the-way villages (a word-group), a devil-may-care speed (a sentence). There are different semantic relations between the components of «stone wall» combinations. E.I. Chapnik classified them into the following groups:

1. time relations, e.g. evening paper,

2. space relations, e.g. top floor,

3. relations between the object and the material of which it is made, e.g. steel helmet,

4. cause relations, e.g. war orphan,

5. relations between a part and the whole, e.g. a crew member,

6. relations between the object and an action, e.g. arms production,

7. relations between the agent and an action e.g. government threat, price rise,

8. relations between the object and its designation, e.g. reception hall,

9. the first component denotes the head, organizer of the characterized object, e.g. Clinton government, Forsyte family,

10. the first component denotes the field of activity of the second component, e.g. language teacher, psychiatry doctor,

11. comparative relations, e.g. moon face,

12. qualitative relations, e.g. winter apples.

ABBREVIATION

In the process of communication words and word-groups can be shortened. The causes of shortening can be linguistic and extra-linguistic. By extra-linguistic causes changes in the life of people are meant. In Modern English many new abbreviations, acronyms, initials, blends are formed because the tempo of life is increasing and it becomes necessary to give more and more information in the shortest possible time. There are also linguistic causes of abbreviating words and word-groups, such as the demand of rhythm, which is satisfied in English by monosyllabic words. When borrowings from other languages are assimilated in English they are shortened. Here we have modification of form on the basis of analogy, e.g. the Latin borrowing «fanaticus» is shortened to «fan» on the analogy with native words: man, pan, tan etc. There are two main types of shortenings: graphical and lexical.

Graphical abbreviations

Graphical abbreviations are the result of shortening of words and word-groups only in written speech while orally the corresponding full forms are used. They are used for the economy of space and effort in writing. The oldest group of graphical abbreviations in English is of Latin origin. In Russian this type of abbreviation is not typical. In these abbreviations in the spelling Latin words are shortened, while orally the corresponding English equivalents are pronounced in the full form, e.g. for example (Latin exampli gratia), a.m. – in the morning (ante meridiem), No – number (numero), p.a. – a year (per annum), d – penny (dinarius), lb – pound (libra), i. e. – that is (id est) etc.

Some graphical abbreviations of Latin origin have different English equivalents in different contexts, e.g. p.m. can be pronounced «in the afternoon» (post meridiem) and «after death» (post mortem). There are also graphical abbreviations of native origin, where in the spelling we have abbreviations of words and word-groups of the corresponding English equivalents in the full form. We have several semantic groups of them: a) days of the week, e.g. Mon – Monday, Tue – Tuesday etc

b) names of months, e.g. Apr – April, Aug – August etc.

c) names of counties in UK, e.g. Yorks – Yorkshire, Berks – Berkshire etc

d) names of states in USA, e.g. Ala – Alabama, Alas – Alaska etc.

e) names of address, e.g. Mr., Mrs., Ms., Dr. etc.

f) military ranks, e.g. capt. – captain, col. – colonel, sgt – sergeant etc.

g) scientific degrees, e.g. B.A. – Bachelor of Arts, D.M. – Doctor of Medicine. (Sometimes in scientific degrees we have abbreviations of Latin origin, e.g., M.B. – Medicinae Baccalaurus).

h) units of time, length, weight, e.g. f./ft – foot/feet, sec. – second, in. – inch, mg. – milligram etc.

The reading of some graphical abbreviations depends on the context, e.g. «m» can be read as: male, married, masculine, metre, mile, million, minute, «l.p.» can be read as long-playing, low pressure.

Initial abbreviations

Initialisms are the bordering case between graphical and lexical abbreviations. When they appear in the language, as a rule, to denote some new offices they are closer to graphical abbreviations because orally full forms are used, e.g. J.V. – joint venture. When they are used for some duration of time they acquire the shortened form of pronouncing and become closer to lexical abbreviations, e.g. BBC is as a rule pronounced in the shortened form. In some cases the translation of initialisms is next to impossible without using special dictionaries. Initialisms are denoted in different ways. Very often they are expressed in the way they are pronounced in the language of their origin, e.g. ANZUS (Australia, New Zealand, United States) is given in Russian as АНЗУС, SALT (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks) was for a long time used in Russian as СОЛТ, now a translation variant is used (ОСВ – Договор об ограничении стратегических вооружений). This type of initialisms borrowed into other languages is preferable, e.g. UFO – НЛО, CП – JV etc. There are three types of initialisms in English:

a) initialisms with alphabetical reading, such as UK, BUP, CND etc

b) initialisms which are read as if they are words, e.g. UNESCO, UNO, NATO etc.

c) initialisms which coincide with English words in their sound form, such initialisms are called acronyms, e.g. CLASS (Computor-based Laboratory for Automated School System). Some scientists unite groups b) and c) into one group which they call acronyms. Some initialisms can form new words in which they act as root morphemes by different ways of wordbuilding:

a) affixation, e.g. AVALism, ex- POW, AIDSophobia etc.

b) conversion, e.g. to raff, to fly IFR (Instrument Flight Rules),

c) composition, e.g. STOLport, USAFman etc.

d) there are also compound-shortened words where the first component is an initial abbreviation with the alphabetical reading and the second one is a complete word, e.g. A-bomb, U-pronunciation, V -day etc. In some cases the first component is a complete word and the second component is an initial abbreviation with the alphabetical pronunciation, e.g. Three -Ds (Three dimensions) – стереофильм.

Abbreviations of words

Abbreviation of words consists in clipping a part of a word. As a result we get a new lexical unit where either the lexical meaning or the style is different form the full form of the word. In such cases as «fantasy» and «fancy», «fence» and «defence» we have different lexical meanings. In such cases as «laboratory» and «lab», we have different styles. Abbreviation does not change the part-of-speech meaning, as we have it in the case of conversion or affixation, it produces words belonging to the same part of speech as the primary word, e.g. prof. is a noun and professor is also a noun. Mostly nouns undergo abbreviation, but we can also meet abbreviation of verbs, such as to rev. from to revolve, to tab from to tabulate etc. But mostly abbreviated forms of verbs are formed by means of conversion from abbreviated nouns, e.g. to taxi, to vac etc. Adjectives can be abbreviated but they are mostly used in school slang and are combined with suffixation, e.g. comfy, dilly etc. As a rule pronouns, numerals, interjections. conjunctions are not abbreviated. The exceptions are: fif (fifteen), teen-ager, in one’s teens (apheresis from numerals from 13 to 19). Lexical abbreviations are classified according to the part of the word which is clipped. Mostly the end of the word is clipped, because the beginning of the word in most cases is the root and expresses the lexical meaning of the word. This type of abbreviation is called apocope. Here we can mention a group of words ending in «o», such as disco (dicotheque), expo (exposition), intro (introduction) and many others. On the analogy with these words there developed in Modern English a number of words where «o» is added as a kind of a suffix to the shortened form of the word, e.g. combo (combination) – небольшой эстрадный ансамбль, Afro (African) – прическа под африканца etc. In other cases the beginning of the word is clipped. In such cases we have apheresis, e.g. chute (parachute), varsity (university), copter (helicopter), thuse (enthuse) etc. Sometimes the middle of the word is clipped, e.g. mart (market), fanzine (fan magazine) maths (mathematics). Such abbreviations are called syncope. Sometimes we have a combination of apocope with apheresis, when the beginning and the end of the word are clipped, e.g. tec (detective), van (vanguard) etc. Sometimes shortening influences the spelling of the word, e.g. «c» can be substituted by «k» before «e» to preserve pronunciation, e.g. mike (microphone), Coke (coca-cola) etc. The same rule is observed in the following cases: fax (facsimile), teck (technical college), trank (tranquilizer) etc. The final consonants in the shortened forms are substituded by letters characteristic of native English words.

NON-PRODUCTIVE WAYS OF WORDBUILDING

SOUND INTERCHANGE

Sound interchange is the way of word-building when some sounds are changed to form a new word. It is non-productive in Modern English, it was productive in Old English and can be met in other Indo-European languages. The causes of sound interchange can be different. It can be the result of Ancient Ablaut which cannot be explained by the phonetic laws during the period of the language development known to scientists, e.g. to strike – stroke, to sing – song etc. It can be also the result of Ancient Umlaut or vowel mutation which is the result of palatalizing the root vowel because of the front vowel in the syllable coming after the root (regressive assimilation), e.g. hot — to heat (hotian), blood — to bleed (blodian) etc. In many cases we have vowel and consonant interchange. In nouns we have voiceless consonants and in verbs we have corresponding voiced consonants because in Old English these consonants in nouns were at the end of the word and in verbs in the intervocalic position, e.g. bath – to bathe, life – to live, breath – to breathe etc.

STRESS INTERCHANGE

Stress interchange can be mostly met in verbs and nouns of Romanic origin: nouns have the stress on the first syllable and verbs on the last syllable, e.g. `accent — to ac`cent. This phenomenon is explained in the following way: French verbs and nouns had different structure when they were borrowed into English, verbs had one syllable more than the corresponding nouns. When these borrowings were assimilated in English the stress in them was shifted to the previous syllable (the second from the end). Later on the last unstressed syllable in verbs borrowed from French was dropped (the same as in native verbs) and after that the stress in verbs was on the last syllable while in nouns it was on the first syllable. As a result of it we have such pairs in English as: to af«fix -`affix, to con`flict- `conflict, to ex`port -`export, to ex`tract — `extract etc. As a result of stress interchange we have also vowel interchange in such words because vowels are pronounced differently in stressed and unstressed positions.

SOUND IMITATION

It is the way of word-building when a word is formed by imitating different sounds. There are some semantic groups of words formed by means of sound imitation:

a) sounds produced by human beings, such as : to whisper, to giggle, to mumble, to sneeze, to whistle etc.

b) sounds produced by animals, birds, insects, such as: to hiss, to buzz, to bark, to moo, to twitter etc.

c) sounds produced by nature and objects, such as: to splash, to rustle, to clatter, to bubble, to ding-dong, to tinkle etc.

The corresponding nouns are formed by means of conversion, e.g. clang (of a bell), chatter (of children) etc.

BLENDS

Blends are words formed from a word-group or two synonyms. In blends two ways of word-building are combined: abbreviation and composition. To form a blend we clip the end of the first component (apocope) and the beginning of the second component (apheresis) . As a result we have a compound- shortened word. One of the first blends in English was the word «smog» from two synonyms: smoke and fog which means smoke mixed with fog. From the first component the beginning is taken, from the second one the end, «o» is common for both of them. Blends formed from two synonyms are: slanguage, to hustle, gasohol etc. Mostly blends are formed from a word-group, such as: acromania (acronym mania), cinemaddict (cinema adict), chunnel (channel, canal), dramedy (drama comedy), detectifiction (detective fiction), faction (fact fiction) (fiction based on real facts), informecial (information commercial), Medicare (medical care), magalog (magazine catalogue) slimnastics (slimming gymnastics), sociolite (social elite), slanguist (slang linguist) etc.

BACK FORMATION

It is the way of word-building when a word is formed by dropping the final morpheme to form a new word. It is opposite to suffixation, that is why it is called back formation. At first it appeared in the language as a result of misunderstanding the structure of a borrowed word. Prof. Yartseva explains this mistake by the influence of the whole system of the language on separate words. E.g. it is typical of English to form nouns denoting the agent of the action by adding the suffix -er to a verb stem (speak- speaker). So when the French word «beggar» was borrowed into English the final syllable «ar» was pronounced in the same way as the English —er and Englishmen formed the verb «to beg» by dropping the end of the noun. Other examples of back formation are: to accreditate (from accreditation), to bach (from bachelor), to collocate (from collocation), to enthuse (from enthusiasm), to compute (from computer), to emote (from emotion), to televise (from television) etc.

As we can notice in cases of back formation the part-of-speech meaning of the primary word is changed, verbs are formed from nouns.

23

Word-building in Modern English

By word-building are understood processes of producing new words from the resources of this particular language. Together with borrowing, word-building provides for enlarging and enriching the vocabulary of the language.

Morpheme is the smallest recurrent unit of language directly related to meaning

All morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots (or radicals) and affixes. The latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes which precede the root in the structure of the word (as in reread, mispronounce, unwell) and suffixes which follow the root (as in teach-er, cur-able, diet-ate).

We can distinguish words due to a morphological structure Words which consist of a root are called root words: house, room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.

We can distinguish words due to a morphological structure Words which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word-building known as affixation (or derivation): re-read, mis-pronounce, un-well, teach-er.

We can distinguish words due to a morphological structure A compound word is made when two words are joined to form a new word: dining-room, bluebell (колокольчик), mother-in-law, good-for-nothing(бездельник)

We can distinguish words due to a morphological structure Сompound-derivatives are words in which the structural integrity of the two free stems is ensured by a suffix referring to the combination as a whole, not to one of its elements: kind-hearted, old-timer, schoolboyishness, teenager.

There are the following ways of word-building: • • • Affixation Composition Conversion Shortening (Contraction) Non-productive types of word-building: A) Sound-Imitation B) Reduplication C) Back-Formation (Reversion)

Affixation The process of affixation consists in coining a new word by adding an affix or several affixes to some root morpheme.

The role of the affix in this procedure is very important and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the main types of affixes. From the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same two large groups as words: native and borrowed.

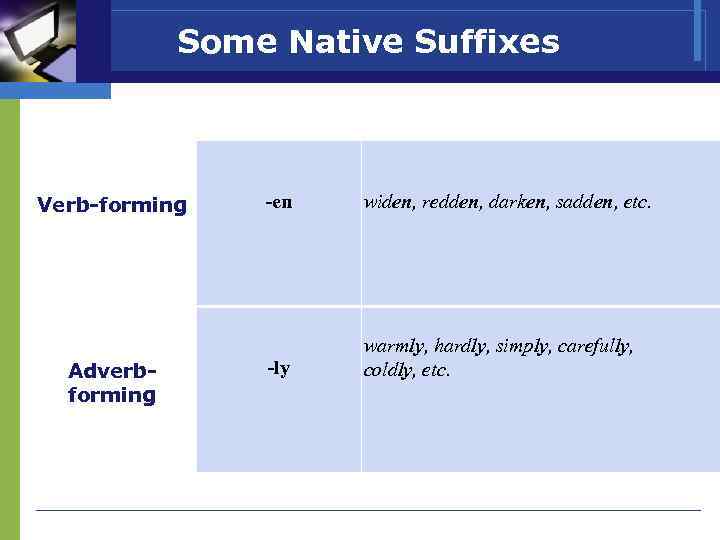

Some Native Suffixes -er Nounforming worker, miner, teacher, painter, etc. -ness coldness, loneliness, loveliness, etc. -ing feeling, meaning, singing, reading, etc. -dom freedom, wisdom, kingdom, etc. -hood childhood, manhood, motherhood, etc. -ship friendship, companionship, mastership, etc. -th length, breadth, health, truth, etc.

Some Native Suffixes -ful Adjectiveforming -less -y careful, joyful, wonderful, sinful, skilful, etc. careless, sleepless, cloudless, senseless, etc. cozy, tidy, merry, snowy, showy, etc. -ish English, Spanish, reddish, childish, etc. -ly lonely, lovely, ugly, likely, lordly, etc. -en wooden, woollen, silken, golden, etc. -some handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome, etc.

Some Native Suffixes Verb-forming Adverbforming -en widen, redden, darken, sadden, etc. -ly warmly, hardly, simply, carefully, coldly, etc.

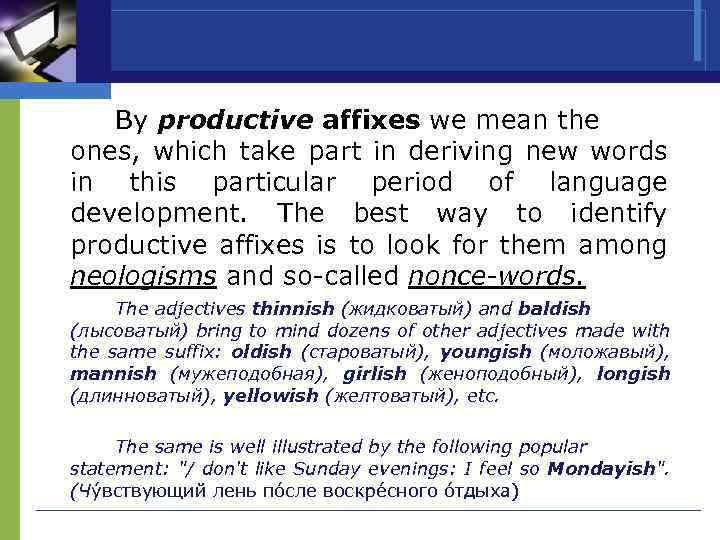

By productive affixes we mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in this particular period of language development. The best way to identify productive affixes is to look for them among neologisms and so-called nonce-words. The adjectives thinnish (жидковатый) and baldish (лысоватый) bring to mind dozens of other adjectives made with the same suffix: oldish (староватый), youngish (моложавый), mannish (мужеподобная), girlish (женоподобный), longish (длинноватый), yellowish (желтоватый), etc. The same is well illustrated by the following popular statement: «/ don’t like Sunday evenings: I feel so Mondayish». (Чу вствующий лень по сле воскре сного о тдыха)

One should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency of occurrence. There are quite a number of high-frequency affixes which, nevertheless, are no longer used in wordderivation e. g. the adjective-forming native suffixes -ful, -ly; the adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin -ant, -ent, -al which are quite frequent

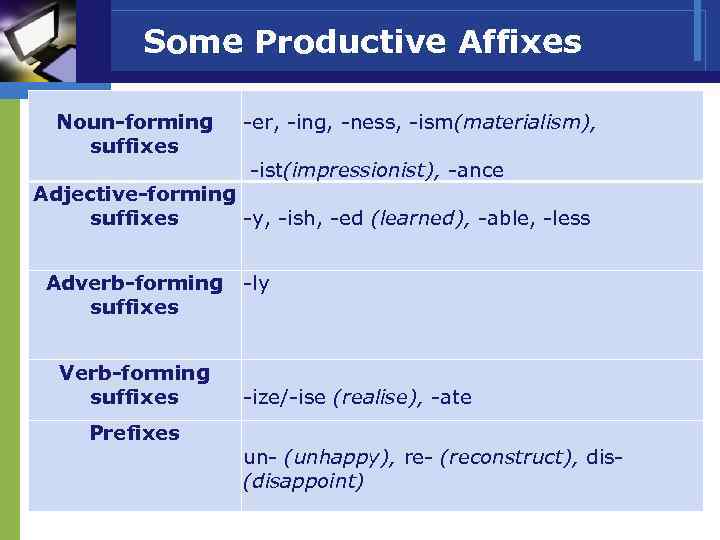

Some Productive Affixes Noun-forming suffixes -er, -ing, -ness, -ism(materialism), -ist(impressionist), -ance Adjective-forming suffixes -y, -ish, -ed (learned), -able, -less Adverb-forming -ly suffixes Verb-forming suffixes Prefixes -ize/-ise (realise), -ate un- (unhappy), re- (reconstruct), dis- (disappoint)

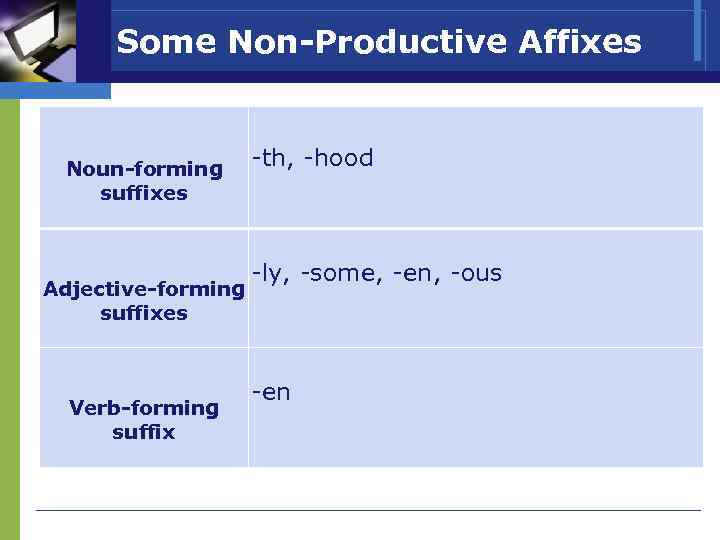

Some Non-Productive Affixes Noun-forming suffixes Adjective-forming suffixes Verb-forming suffix -th, -hood -ly, -some, -en, -ous -en

Composition is a type of word-building, in which new words are produced by combining two or more stems

Compounds are not homogeneous in structure. Traditionally three types are distinguished: vneutral vmorphological vsyntactic

Neutral In neutral compounds the process of compounding is realised without any linking elements, by a mere juxtaposition of two stems, as in blackbird(дрозд) shopwindow(витрина) sunflower(подсолнух) bedroom(спальня) etc.

There are three subtypes of neutral compounds depending on the structure of the constituent stems. The examples: shopwindow(витрина), sunflower(подсолнух), bedroom(спальня) represent the subtype which may be described as simple neutral compounds: they consist of simple affixless stems.

The third subtype of neutral compounds is called contracted compounds. These words have a shortened (contracted) stem in their structure: V-day (день победы) (Victory day), G -man (агент ФБР) (Government man «FBI agent»), H-bag (сумочка) (handbag), T-shirt(футболка), etc.

Morphological compounds are few in number. This type is nonproductive. It is represented by words in which two compounding stems are combined by a linking vowel or consonant: e. g. Anglo-Saxon, Franko. Prussian, handiwork(изделие ручной работы), statesman (политический деятель/политик)

Syntactic These words are formed from segments of speech, preserving in their structure numerous traces of syntagmatic relations typical of speech: articles, prepositions, adverbs. e. g. father-in-law, mother-inlaw etc.

Conversion consists in making a new word from some existing word by changing the category of a part of speech, the morphemic shape of the original word remaining unchanged.

It has also a new paradigm peculiar to its new category as a part of speech. Conversion is a convenient and «easy» way of enriching the vocabulary with new words. The two categories of parts of speech especially affected by conversion are nouns and verbs.

Verbs made from nouns are the most numerous amongst the words produced by conversion: e. g. to hand(передавать) to back(поддерживать) to face(стоять лицом к кому-либо) to eye(рассматривать) to nose(разнюхивать) to dog(выслеживать)

Nouns are frequently made from verbs: e. g. make(марка) run(бег) find(находка) walk(прогулка) worry(тревога) show(демонстрация) move(движение)

Verbs can also be made from adjectives: e. g. to pale(побледнеть) to yellow(желтеть) to cool(охлаждать) Other parts of speech are not entirely unsusceptible to conversion.

Shortening (Contraction) This comparatively new way of word-building has achieved a high degree of productivity nowadays, especially in American English. Shortenings (or contracted words) are produced in two different ways.

The first way The first is to make a new word from a syllable (rarer, two) of the original word. The latter may lose its beginning (as in phone made from telephone, fence from defence), its ending (as in hols from holidays, vac from vacation, props from properties, ad from advertisement) or both the beginning and ending (as in flu from influenza, fridge from refrigerator)

The second way of shortening is to make a new word from the initial letters of a word group: U. N. O. from the United Nations Organisation, B. B. C. from the British Broadcasting Corporation, M. P. from Member of Parliament. This type is called initial shortenings.

Both types of shortenings are characteristic of informal speech in general and of uncultivated speech particularly: E. g. Movie (from moving-picture), gent (from gentleman), specs (from spectacles), circs (from circumstances, e. g. under the circs), I. O. Y. (from I owe you), lib (from liberty), cert (from certainty), exhibish (from exhibition), posish (from position)

Non-productive types of word -building Sound-Imitation Words coined by this interesting type of word-building are made by imitating different kinds of sounds that may be produced by human beings: to whisper (шептать), to whistle (свистеть), to sneeze (чихать), to giggle (хихикать);

animals, birds, insects: to hiss (шипеть), to buzz (жужжать), to bark (лаять), to moo (мычать); inanimate objects: to boom (гудеть), to ding-dong (звенеть), to splash (брызгать);

Reduplication In reduplication new words are made by doubling a stem, either without any phonetic changes as in bye-bye (coll, for good-bye) or with a variation of the root-vowel

This type of word-building is greatly facilitated in Modern English by the vast number of monosyllables. Stylistically speaking, most words made by reduplication represent informal groups: colloquialisms and slang. E. g. walkietalkie («a portable radio»), riff-raff («the worthless or disreputable element of society»; «the dregs of society»), chichi (sl. for chic as in a chi-chi girl)

In a modern novel an angry father accuses his teenager son of doing nothing but dillydallying all over the town. (dillydallying — wasting time, doing nothing)

Another example of a word made by reduplication may be found in the following quotation from “The Importance of Being Earnest” by O. Wilde: Lady Bracknell: I think it is high time that Mr. Bunbury made up his mind whether he was going to live or to die. This shilly-shallying with the question is absurd. (shilly-shallying — irresolution, indecision)

Back-formation Forming the allegedly original stem from a supposed derivative on the analogy of the existing pairs, i. e. the singling-out of a stem from a word which is wrongly regarded as a derivative.

The earliest examples of this type of word-building are the verb to beg (попрошайничать) that was made from the French borrowing beggar (нищий, бедняк), to burgle (незаконно проникать в помещение) from burglar (вор-домушник). In all these cases the verb was made from the noun by subtracting what was mistakenly associated with the English suffix -er.

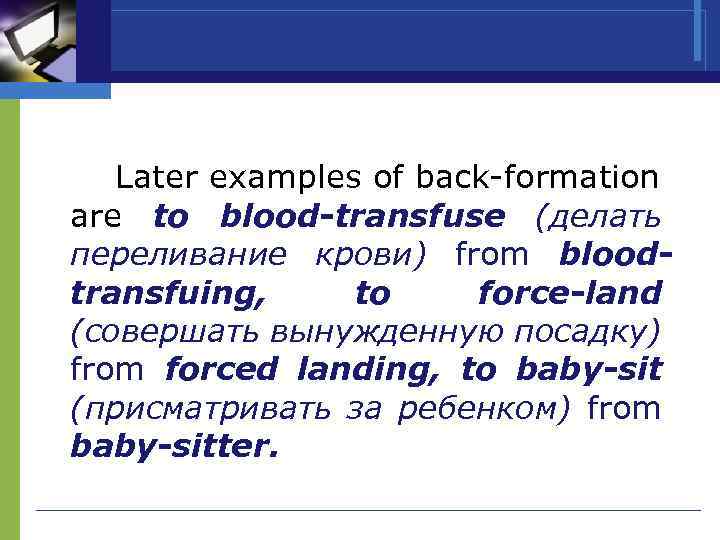

Later examples of back-formation are to blood-transfuse (делать переливание крови) from bloodtransfuing, to force-land (совершать вынужденную посадку) from forced landing, to baby-sit (присматривать за ребенком) from baby-sitter.

Для знания иностранного языка богатство словарного запаса ничуть не менее важно, чем понимание грамматики. Чем большим количеством слов владеет человек, тем свободнее он себя чувствует в иноязычной среде.

Многообразие лексики во многом определяется богатством словообразования в английском языке. Построение новых слов основано на общих принципах. И тот, кто знает эти принципы, чувствует себя среди незнакомой лексики гораздо увереннее.

Структура слова и ее изменение

Новые слова усваиваются постепенно. Чаще всего, сначала мы только понимаем их в текстах или чужой речи, а уже потом начинаем активно использовать в своей. Поэтому освоение новой лексики – процесс длительный и требует от ученика терпения, активной практики чтения, слушания и работы со словарем.

Один из методов быстро расширить свой словарный запас – освоить способы словообразования в английском языке. Поняв принципы, по которым строятся слова, можно из уже известного слова вывести значения его однокоренных слов.

Строительный материал для каждого слова – это корень, приставки и суффиксы. Корень – это та часть слова, которая несет основной смысл. Слово без корня не может существовать. Тогда как приставки и суффиксы – необязательная часть, однако прибавляясь к корню, именно они помогают образовать новые слова. Поэтому, описывая словообразование в английском, мы будем разделять приставочные и суффиксальные способы.

Все приставки и суффиксы обладают собственным значением. Обычно оно довольно размыто и служит для изменения основного значения слова. Когда к корню добавляется приставка или суффикс (или же оба элемента), то их значение прибавляется к значению корня. Так получается новое слово.

Образование новых слов может приводить не только к изменению значения, но и менять части речи. В этой функции чаще выступают суффиксы. Прибавляясь к корню, они переводят слово из одной части речи в другую, например, делают прилагательное из глагола или глагол из существительного.

Так, от одного корня может образоваться целая группа, все элементы которой связаны между собой. Поэтому словообразование помогает изучающим английский видеть смысловые отношения между словами и лучше ориентироваться в многообразии лексики.

Получить новое слово можно не только за счет приставок и суффиксов. Еще один способ – это словосложение, при котором в одно слово объединяются два корня, образуя новый смысл. Кроме того, к словообразованию относится сокращение слов и создание аббревиатур.

Приставки как способ словообразования в английском

Приставка (также употребляется термин «префикс») – элемент слова, который ставится перед корнем. Приставочное словообразование английский язык редко использует для смены частей речи (в качестве исключения можно назвать префикс «en-» / «em-» для образования глаголов). Зато приставки активно используются для изменения значения слова. Сами префиксы могут иметь различные значения, но среди них выделяется большая группа приставок со схожей функцией: менять смысл слова на противоположный.

1. Приставки с отрицательным значением:

- un-: unpredictable (непредсказуемый), unable (неспособный)

- dis-: disapproval (неодобрение), disconnection (отделение от)

- im-, in-, il -,ir-: inactive (неактивный), impossible (невозможный), irregular (нерегулярный), illogical (нелогичный). То, какая из этих приставок будет присоединяться к слову, зависит от следующего за ней звука. «Im-» ставится только перед согласными «b», «p», «m» (impatient — нетерпеливый). «Il-» возможно только перед буквой «l» (illegal — незаконный), «ir-» – только перед «r» (irresponsible — безответственный). Во всех остальных случаях употребляется приставка «in-» (inconvenient – неудобный, стесняющий).

- mis-: misfortune (несчастье, беда). Приставка «mis-» может использоваться не только для образования прямых антонимов, но и иметь более общее значение отрицательного воздействия (misinform — дезинформировать, вводить в заблуждение, misunderstand — неправильно понять).

2. Другие приставочные значения

- re-: rebuild (отстроить заново, реконструировать). Приставка описывает повторные действия (rethink — переосмыслить) или указывает на обратное направление (return — возвращаться).

- co-: cooperate (сотрудничать). Описывает совместную деятельность (co-author – соавтор).

- over-: oversleep (проспать). Значение префикса — избыточность, излишнее наполнение (overweight — избыточный вес) или прохождение определенной черты (overcome — преодолеть).

- under-: underact (недоигрывать). Приставку можно назвать антонимом к приставке «over-», она указывает на недостаточную степень действия (underestimate — недооценивать). Кроме того, приставка используется и в изначальном значении слова «under» — «под» (underwear — нижнее белье, underground — подземка, метро).

- pre-: prehistoric (доисторический). Приставка несет в себе идею предшествования (pre-production — предварительная стадия производства).

- post-: post-modern (постмодернизм). В отличие от предыдущего случая, приставка указывает на следование действия (postnatal – послеродовой).

- en-, em-: encode (кодировать). Префикс служит для образования глагола и имеет значение воплощения определенного качества или состояния (enclose — окружать). Перед звуками «b», «p», «m» приставка имеет вид «em-» (empoison — подмешивать яд), в остальных случаях – «en-» (encourage — ободрять).

- ex-: ex-champion (бывший чемпион). Используется для обозначения бывшего статуса или должности (ex-minister — бывший министр).

Образование новых слов при помощи суффиксов

Суффиксы занимают позицию после корня. За ними может также следовать окончание (например, показатель множественного числа «-s»). Но в отличие от суффикса окончание не образует слова с новым значением, а только меняет его грамматическую форму (boy – мальчик, boys – мальчики).

По суффиксу часто можно определить, к какой части речи принадлежит слово. Среди суффиксов существуют и такие, которые выступают только как средство образования другой части речи (например, «-ly» для образования наречий). Поэтому рассматривать эти элементы слова мы будем в зависимости от того, какую часть речи они характеризуют.

Словообразование существительных в английском языке

Среди суффиксов существительных можно выделить группу, обозначающую субъектов деятельности и группу абстрактных значений.

1. Субъект деятельности

- -er, -or: performer (исполнитель). Такие суффиксы описывают род занятий (doctor — доктор, farmer — фермер) или временные роли (speaker — оратор, visitor — посетитель). Могут использоваться и в качестве характеристики человека (doer — человек дела, dreamer — мечтатель).

- -an, -ian: magician (волшебник). Суффикс может участвовать в образовании названия профессии (musician — музыкант) или указывать на национальность (Belgian — бельгийский / бельгиец).

- -ist: pacifist (пацифист). Этот суффикс описывает принадлежность к определенному роду деятельности (alpinist – альпинист) или к социальному течению, направлению в искусстве (realist — реалист).

- -ant, -ent: accountant (бухгалтер), student (студент).

- -ee: employee (служащий), conferee (участник конференции).

- -ess : princess (принцесса). Суффикс используется для обозначения женского рода (waitress – официантка).

2. Абстрактные существительные

Основа этой группы значений – обозначение качества или состояния. Дополнительным значением может выступать объединение группы людей и обозначение определенной совокупности.

- -ity: activity (деятельность), lability (изменчивость).

- -ance, -ence, -ancy, -ency: importance (важность), dependence (зависимость), brilliancy (великолепие), efficiency (эффективность).

- -ion, -tion, -sion: revision (пересмотр, исправление), exception (исключение), admission (допущение), information (информация).

- -ism: realism (реализм). В отличие от суффикса «-ist» обозначает не представителя некоторого течения, а само течение (modernism — модернизм) или род занятий (alpinism — альпинизм).

- -hood: childhood (детство). Может относиться не только к состоянию, но и описывать группу людей, форму отношений: brotherhood (братство).

- -ure: pleasure (удовольствие), pressure (давление).

- -dom: wisdom (мудрость). Также используется при обозначении группы людей, объединения по некоторому признаку: kingdom (королевство).

- -ment: announcement (объявление), improvement (улучшение).

- -ness: darkness (темнота), kindness (доброта).

- -ship: friendship (дружба). К дополнительным значениям относится указание на титул (lordship — светлость), умение (airmanship — лётное мастерство) или на объединение круга людей определенными отношениями (membership — круг членов, partnership — партнерство).

- -th: truth (правда), length (длина).

Словообразование прилагательных в английском языке

- -ful: helpful (полезный). Указывает на обладание определенным качеством (joyful — радостный, beautiful — красивый).

- -less: countless (бессчетный). Значение суффикса близко к отрицанию и характеризует отсутствие определенного качества, свойства (careless — беззаботный). Этот суффикс можно определить как антоним для «-ful» (hopeless — безнадежный, а hopeful — надеющийся).

- -able: comfortable (комфортный). «Able» (способный) существует и как самостоятельное прилагательное. Оно определяет значение суффикса – возможный для выполнения, доступный к осуществлению (acceptable – приемлемый, допустимый, detectable – тот, который можно обнаружить).

- -ous: famous (знаменитый), dangerous (опасный).

- -y: windy (ветреный), rusty (ржавый).

- -al: accidental (случайный), additional (добавочный).

- -ar: molecular (молекулярный), vernacular (народный).

- -ant, -ent: defiant (дерзкий), evident (очевидный).

- -ary, -ory: secondary (второстепенный), obligatory (обязательный).

- -ic: democratic (демократический), historic (исторический).

- -ive: creative (творческий), impressive (впечатляющий).

- -ish: childish (детский, ребяческий). Суффикс описывает характерный признак с негативной оценкой (liquorish – развратный) или с ослабленной степенью качества (reddish — красноватый). Кроме того, суффикс может отсылать к национальности (Danish — датский).

- -long: livelong (целый, вечный). Такой суффикс обозначает длительность (lifelong — пожизненный) или направление (sidelong — косой, вкось) и может принадлежать не только прилагательному, но и наречию.

Словообразование глаголов

Для глагольных суффиксов сложно определить конкретные значения. Основная функция таких суффиксов — перевод в другую часть речи, то есть само образование глагола.

- -ate: activate (активизировать), decorate (украшать).

- -ify, -fy: notify (уведомлять), verify (проверять).

- -ise, -ize: summarize (суммировать), hypnotize (гипнотизировать).

- -en: weaken (ослабевать), lengthen (удлинять).

- -ish: demolish (разрушать), embellish (украшать).

Словообразование наречий

- -ly: occasionally (случайно).

- -wise: otherwise (иначе). Обозначает способ действия (archwise — дугообразно).

- -ward(s): skyward/skywards (к небу). Обозначает направление движения (northward — на север, shoreward — по направлению к берегу).

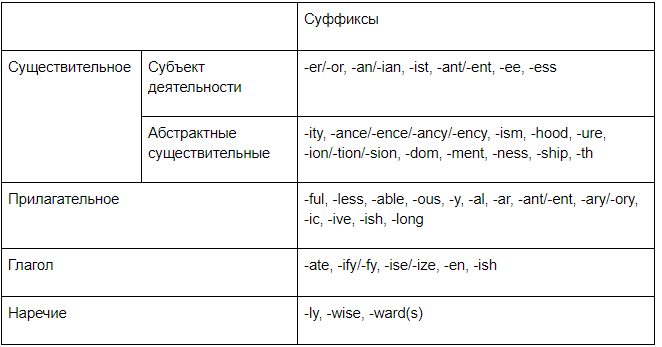

Суффиксы: таблица словообразования по частям речи

Приведенный список суффиксов – это далеко не все возможности английского языка. Мы описали наиболее распространенные и интересные случаи. Для того чтобы разобраться в этом множестве вариантов и лучше усвоить образование слов в английском языке, таблица резюмирует, для каких частей речи какие суффиксы характерны.

Поскольку суффиксальное преобразование слов в английском языке различается по частям речи, таблица разбита на соответствующие группы. Одни и те же суффиксы могут добавляться к разным частям речи, но в результате они определяют, к какой части речи принадлежит новое слово.

Объединение суффиксов и приставок

Важная характеристика словообразования – это его продуктивность. От одного корня можно образовать целую группу слов, добавляя разные приставки и суффиксы. Приведем несколько примеров.

- Для possible словообразование может выглядеть следующим образом: possible (возможный) — possibility (возможность) — impossibility (невозможность).

- Цепочка переходов для слова occasion: occasion (случай) — occasional (случайный) — occasionally (случайно).

- Для слова agree словообразование можно выстроить в цепочки с приставкой и без приставки: agree (соглашаться) — agreeable (приемлемый / приятный) — agreeably (приятно) — agreement (соглашение, согласие).

agree (соглашаться) — disagree (противоречить, расходиться в мнениях) — disagreeable (неприятный) — disagreeably (неприятно) — disagreement (разногласие).

Словосложение и сокращение слов

Словосложение — еще один способ образовать новое слово, хотя и менее распространенный. Он основан на соединении двух корней (toothbrush — зубная щетка, well-educated — хорошо образованный). В русском языке такое словообразование тоже встречается, например, «кресло-качалка».

Если корень активно используется в словосложении, то он может перейти в категорию суффиксов. В таком случае сложно определить, к какому типу – суффиксам или словосложению – отнести некоторые примеры:

- -man: fireman (пожарный), spiderman (человек-паук)

- -free: sugar-free (без сахара), alcohol-free (безалкогольный)

- -proof: fireproof (огнестойкий), soundproof (звукоизолирующий)

Помимо объединения нескольких корней, возможно также сокращение слов и создание аббревиатур: science fiction — sci-fi (научная фантастика), United States of America – USA (Соединенные Штаты Америки, США).

Новые слова без внешних изменений

К особенности словообразования в английском языке относится и то, что слова могут выступать в разных частях речи без изменения внешнего вида. Это явление называется конверсией:

I hope you won’t be angry with me — Надеюсь, ты не будешь на меня злиться (hope – глагол «надеяться»).

I always had a hope to return to that city — У меня всегда оставалась надежда вернуться в этот город (hope – существительное «надежда»).

The sea is so calm today — Море так спокойно сегодня (calm – прилагательное «спокойный»).

With a calm she realized that her life was probably at its end — Со спокойствием она осознала, что ее жизнь, вероятно, подходила к концу (calm – существительное «спокойствие, невозмутимость»).

I beg you to calm down — Я умоляю тебя успокоиться (calm – глагол «успокоиться»).

Изображение слайда

2

Слайд 2: By word-building are understood processes of producing new words from the resources of this particular language. Together with borrowing, word-building provides for enlarging and enriching the vocabulary of the language

Изображение слайда

3

Слайд 3: Morpheme is the smallest recurrent unit of language directly related to meaning

Изображение слайда

4

Слайд 4: All morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots (or radicals) and affixes. The latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes which precede the root in the structure of the word (as in re-read, mispronounce, unwell) and suffixes which follow the root (as in teach- er, cur-able, diet-ate)

Изображение слайда

5

Слайд 5: We can distinguish words due to a morphological structure

Words which consist of a root are called root words :

house, room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.

Изображение слайда

6

Слайд 6: We can distinguish words due to a morphological structure

Words which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called derived words or derivatives and are produced by the process of word-building known as affixation (or derivation) :

re-read, mis -pronounce, un — well, teach- er.

Изображение слайда

7

Слайд 7: We can distinguish words due to a morphological structure

A compound word is made when two words are joined to form a new word:

dining-room, bluebell (колокольчик), mother-in-law, good-for-nothing (бездельник)

Изображение слайда

8

Слайд 8: We can distinguish words due to a morphological structure

С ompound-derivatives are words in which the structural integrity of the two free stems is ensured by a suffix referring to the combination as a whole, not to one of its elements:

kind-hearted, old-timer, schoolboyishness, teenager.

Изображение слайда

9

Слайд 9: There are the following ways of word-building :

Affixation

Composition

Conversion

Shortening (Contraction)

Non-productive types of word-building:

A) Sound-Imitation

B) Reduplication

C) Back-Formation (Reversion)

Изображение слайда

The process of affixation consists in coining a new word by adding an affix or several affixes to some root morpheme.

Изображение слайда

The role of the affix in this procedure is very important and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the main types of affixes. From the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same two large groups as words: native and borrowed.

Изображение слайда

12

Слайд 12: Some Native Suffixes

Noun- f orming

-er

work er, min er, teach er,

paint er, etc.

-ness

coldn ess, loneli ness,

loveli ness, etc.

-ing

feel ing, mean ing, sing ing,

read ing, etc.

-dom

free dom, wis dom, king dom, etc.

-hood

child hood, man hood, mother hood, etc.

-ship

friend ship, companion ship, master ship, etc.

-th

leng th, bread th, heal th, tru th, etc.

Изображение слайда

13

Слайд 13: Some Native Suffixes

Adjective-forming

-ful

care ful, joy ful, wonder ful, sin ful,

skil ful, etc.

-less

care less, sleep less, cloud less, sense less,

etc.

-y

coz y, tid y, merr y, snow y, show y, etc.

-ish

Engl ish, Span ish, redd ish, child ish, etc.

-ly

lone ly, love ly, ug ly, like ly, lord ly, etc.

-en

wood en, wooll en, silk en, gold en, etc.

-some

hand some, quarrel some, tire some, etc.

Изображение слайда

14

Слайд 14: Some Native Suffixes

Verb-forming

-en

wid en, redd en, dark en, sadd en, etc.

Adverb-forming

-ly

warm ly, hard ly, simp ly, careful ly,

cold ly, etc.

Изображение слайда

An affix of foreign origin can be regarded as borrowed only after it has begun an independent and active life in the recipient language and it is taking part in the word-making processes of that language. This can only occur when the total of words with this affix is so great in the recipient language as to affect the native speakers’ subconscious to the extent that they no longer realize its foreign flavour and accept it as their own.

Изображение слайда

By productive affixes we mean the ones, which take part in deriving new words in this particular period of language development. The best way to identify productive affixes is to look for them among neologisms and so-called nonce-words.

The adjectives thinnish ( жидковатый) and baldish ( лысоватый) bring to mind dozens of other adjectives made with the same suffix: oldish (староватый), youngish (моложавый), mannish (мужеподобная), girlish (женоподобный), longish (длинноватый), yellowish (желтоватый), etc.

The same is well illustrated by the following popular statement: «/ don’t like Sunday evenings: I feel so Mondayish «. ( Ч у́вствующий лень по́сле воскре́сного о́тдыха)

Изображение слайда

One should not confuse the productivity of affixes with their frequency of occurrence. There are quite a number of high-frequency affixes which, nevertheless, are no longer used in word-derivation

e. g. the adjective-forming native suffixes — ful, -ly ; the adjective-forming suffixes of Latin origin -ant, -ent, -al which are quite frequent

Изображение слайда

18

Слайд 18: Some Productive Affixes

Noun-forming suffixes

— er, -ing, -ness, -ism (materialism),

-ist (impressionist), -ance

Adjective-forming suffixes

-y, -ish, -ed (learned), -able, -less

Adverb-forming suffixes

-ly

Verb-forming suffixes

-ize/-ise (realise), -ate

Prefixes

un- (unhappy), re- (reconstruct), dis- (disappoint)

Изображение слайда

19

Слайд 19: Some Non-Productive Affixes

Noun-forming suffixes

-th, -hood

Adjective-forming suffixes

-ly, -some, -en, -ous

Verb-forming suffix

-en

Изображение слайда

Composition is a type of word-building, in which new words are produced by combining two or more stems

Изображение слайда

Compounds are not homogeneous in structure. Traditionally three types are distinguished:

neutral

morphological

syntactic

Изображение слайда

In neutral compounds the process of compounding is realised without any linking elements, by a mere juxtaposition of two stems, as in

blackbird (дрозд)

shopwindow (витрина) sunflower (подсолнух) bedroom (спальня) etc.

Изображение слайда

There are three subtypes of neutral compounds depending on the structure of the constituent stems.

The examples : shopwindow (витрина), sunflower (подсолнух), bedroom (спальня) represent the subtype which may be described as simple neutral compounds : they consist of simple affixless stems.

Изображение слайда

Compounds which have affixes in their structure are called derived or derivational compounds.

E.g. blue-eyed (голубоглазый),

broad-shouldered (широкоплечий)

Изображение слайда

The third subtype of neutral compounds is called contracted compounds. These words have a shortened (contracted) stem in their structure:

V-day (день победы) (Victory day), G-man (агент ФБР) (Government man «FBI agent»), H-bag (сумочка) (handbag), T-shirt (футболка), etc.

Изображение слайда

26

Слайд 26: Morphological

Morphological compounds are few in number. This type is non-productive. It is represented by words in which two compounding stems are combined by a linking vowel or consonant:

e. g. Anglo-Saxon, Franko-Prussian, handiwork( изделие ручной работы), statesman (политический деятель/политик)

Изображение слайда

These words are formed from segments of speech, preserving in their structure numerous traces of syntagmatic relations typical of speech: articles, prepositions, adverbs.

e.g. father-in-law, mother-in-law etc.

Изображение слайда

Conversion consists in making a new word from some existing word by changing the category of a part of speech, the morphemic shape of the original word remaining unchanged.

Изображение слайда

It has also a new paradigm peculiar to its new category as a part of speech. Conversion is a convenient and «easy» way of enriching the vocabulary with new words. The two categories of parts of speech especially affected by conversion are nouns and verbs.

Изображение слайда

Verbs made from nouns are the most numerous amongst the words produced by conversion:

e. g. to hand ( передавать )

to back (поддерживать)

to face (стоять лицом к кому-либо)

to eye (рассматривать)

to nose (разнюхивать)

to dog (выслеживать)

Изображение слайда

Nouns are frequently made from verbs:

e.g. make (марка)

run (бег)

find (находка)

walk (прогулка)

worry (тревога)

show (демонстрация)

move (движение)

Изображение слайда

Verbs can also be made from adjectives:

e. g. to pale (побледнеть)

to yellow (желтеть)

to cool (охлаждать)

Other parts of speech are not entirely unsusceptible to conversion.

Изображение слайда

33

Слайд 33: Shortening (Contraction)

This comparatively new way of word-building has achieved a high degree of productivity nowadays, especially in American English.

Shortenings (or contracted words) are produced in two different ways.

Изображение слайда

34

Слайд 34: The first way

The first is to make a new word from a syllable (rarer, two) of the original word.

The latter may lose its beginning (as in phone made from telephone, fence from defence ), its ending (as in hols from holidays, vac from vacation, props from properties, ad from advertisement ) or both the beginning and ending (as in flu from influenza, fridge from refrigerator )

Изображение слайда

35

Слайд 35: The second way

The second way of shortening is to make a new word from the initial letters of a word group:

U.N.O. from the United Nations Organisation, B.B.C. from the British Broadcasting Corporation, M.P. from Member of Parliament. This type is called initial shortenings.

Изображение слайда

Both types of shortenings are characteristic of informal speech in general and of uncultivated speech particularly:

E. g. Movie (from moving-picture ), gent (from gentleman ), specs (from spectacles ), circs (from circumstances, e. g. under the circs), I. O. Y. (from I owe you ), lib (from liberty ), cert (from certainty ), exhibish (from exhibition ), posish ( from position )

Изображение слайда

37

Слайд 37: Non-productive types of word-building

Sound-Imitation

Words coined by this interesting type of word-building are made by imitating different kinds of sounds that may be produced by

human beings : to whisper ( шептать), to whistle (свистеть), to sneeze (чихать), to giggle (хихикать) ;

Изображение слайда

animals, birds, insects : to hiss (шипеть), to buzz (жужжать), to bark (лаять), to moo (мычать) ;

inanimate objects : to boom (гудеть), to ding-dong (звенеть), to splash (брызгать);

Изображение слайда

Reduplication

In reduplication new words are made by doubling a stem, either without any phonetic changes as in bye-bye (coll, for good-bye )

or with a variation of the root-vowel or consonant as in ping-pong, chit-chat (this second type is called gradational reduplication ).

Изображение слайда

This type of word-building is greatly facilitated in Modern English by the vast number of monosyllables. Stylistically speaking, most words made by reduplication represent informal groups: colloquialisms and slang. E. g. walkie-talkie («a portable radio»), riff-raff («the worthless or disreputable element of society»; «the dregs of society»), chi-chi (sl. for chic as in a chi-chi girl)

Изображение слайда

In a modern novel an angry father accuses his teenager son of doing nothing but dilly-dallying all over the town. ( dilly-dallying — wasting time, doing nothing)

Изображение слайда

Another example of a word made by reduplication may be found in the following quotation from “The Importance of Being Earnest” by O. Wilde:

Lady Bracknell: I think it is high time that Mr. Bunbury made up his mind whether he was going to live or to die. This shilly-shallying with the question is absurd. ( shilly-shallying — irresolution, indecision)

Изображение слайда

Back-formation

Forming the allegedly original stem from a supposed derivative on the analogy of the existing pairs, i. e. the singling-out of a stem from a word which is wrongly regarded as a derivative.

Изображение слайда

The earliest examples of this type of word-building are the verb to beg ( попрошайничать) that was made from the French borrowing beggar (нищий, бедняк), to burgle (незаконно проникать в помещение) from burglar (вор-домушник).

In all these cases the verb was made from the noun by subtracting what was mistakenly associated with the English suffix -er.

Изображение слайда

45

Последний слайд презентации: Word-building in Modern English

Later examples of back-formation are to blood-transfuse (делать переливание крови) from blood-transfuing, to force-land (совершать вынужденную посадку) from forced landing, to baby-sit ( присматривать за ребенком) from baby-sitter.

Изображение слайда

The

outline of the problem discussed

1.

The main types of words in English and their morphological structure.

2.

Affixation (or derivation).

3.

Compounding.

4.

Conversion.

5.

Abbreviation (shortening).

Word-formation

is the process of creating new words from the material

available

in the language.

Before

turning to various processes of word-building in English, it would be

useful

to analyze the main types of English words and their morphological

structure.

If

viewed structurally, words appear to be divisible into smaller units

which are

called

morphemes.

Morphemes

do not occur as free forms but only as constituents of

words.

Yet they possess meanings of their own.

All

morphemes are subdivided into two large classes: roots

(or

radicals)

and

affixes.

The

latter, in their turn, fall into prefixes

which

precede the root in the

structure

of the word (as in re-real,

mis-pronounce, un-well) and

suffixes

which

follow

the root (as in teach-er,

cur-able, dict-ate).

Words

which consist of a root and an affix (or several affixes) are called

derived

words or

derivatives

and

are produced by the process of word-building

known

as affixation

(or

derivation).

Derived

words are extremely numerous in the English vocabulary.

Successfully

competing with this structural type is the so-called root

word which

has

only

a root morpheme in its structure. This type is widely represented by

a great

number

of words belonging to the original English stock or to earlier

borrowings

(house,

room, book, work, port, street, table, etc.), and,

in Modern English, has been

greatly

enlarged by the type of word-building called conversion

(e.g.

to

hand, v.

formed

from the noun hand;

to can, v.

from can,

n.;

to

pale,

v. from pale,

adj.;

a

find,

n.

from to

find, v.;

etc.).

Another

wide-spread word-structure is a compound

word consisting

of two or

more

stems (e.g. dining-room,

bluebell, mother-in-law, good-for-nothing).

Words of

this

structural type are produced by the word-building process called

composition.

The

somewhat odd-looking words like flu,

lab, M.P., V-day, H-bomb are

called

curtailed

words and

are produced by the way of word-building called shortening

(abbreviation).

The

four types (root words, derived words, compounds, shortenings)

represent

the

main structural types of Modern English words, and affixation

(derivation),

conversion,

composition and shortening (abbreviation) — the most productive ways

of

word-building.

83

The

process of affixation

consists

in coining a new word by adding an affix or

several

affixes to some root morpheme. The role of the affix in this

procedure is very

important

and therefore it is necessary to consider certain facts about the

main types

of

affixes.

From

the etymological point of view affixes are classified into the same

two

large

groups as words: native and borrowed.

Some

Native Suffixes

-er

worker,

miner,

teacher,

painter,

etc.

-ness

coldness,

loneliness,

loveliness,

etc.

-ing

feeling,

meaning,

singing,

reading,

etc.

-dom

freedom,

wisdom,

kingdom,

etc.

-hood

childhood,

manhood,

motherhood,

etc.

-ship

friendship,

companionship,

mastership,

etc.

Noun-forming

-th

length,

breadth,

health,

truth,

etc.

-ful

careful,

joyful,

wonderful,

sinful,

skilful,

etc.

-less

careless,

sleepless,

cloudless,

senseless,

etc.

-y

cozy,

tidy,

merry,

snowy,

showy,

etc.

-ish

English,

Spanish,

reddish,

childish,

etc.

-ly

lonely,

lovely,

ugly,

likely,

lordly,

etc.

-en

wooden,

woollen,

silken,

golden,

etc.

Adjective-forming

-some

handsome, quarrelsome, tiresome, etc.

Verb-

forming

-en

widen,

redden,

darken,

sadden,

etc.

Adverb-

forming

-ly

warmly,

hardly,

simply,

carefully,