This article is about the men’s player of the year award from 1991–2009, and the women’s player of the year award from 2001–2015. For the men’s player of the year award from 2010–2015, see FIFA Ballon d’Or. For the men’s award since 2016, see The Best FIFA Men’s Player. For the women’s award since 2016, see The Best FIFA Women’s Player.

The FIFA World Player of the Year was an association football award presented annually by the sport’s governing body, FIFA, between 1991 and 2015 at the FIFA World Player Gala. Coaches and captains of international teams and media representatives selected the player they deem to have performed the best in the previous calendar year.

| FIFA World Player of the Year | |

|---|---|

Ronaldo, the youngest recipient of the award aged 20, won it three times. |

|

| Presented by | FIFA |

| First awarded | 1991 |

| Last awarded | 2009 |

| Most awards | (3 awards each) |

| Website | fifa.com |

| Related | FIFA Ballon d’Or The Best FIFA Men’s Player |

| FIFA Women’s World Player of the Year | |

|---|---|

Marta, the youngest recipient of the award aged 20, won it five times. |

|

| Presented by | FIFA |

| First awarded | 2001 |

| Last awarded | 2015 |

| Most awards | |

| Website | fifa.com |

| Related | The Best FIFA Women’s Player |

Originally a single award for the world’s best men’s player, parallels awards for men and women were awarded from 2001 to 2009. The men’s award was subsumed into the FIFA Ballon d’Or in 2010 while the women’s award remained until 2015. After 2015 both men’s and women’s awards became part of The Best FIFA Football Awards.

During the men’s era, Brazilian players won 8 out of 19 years, compared to three wins – the second most – for French players. In terms of individual players, Brazil again led with five, followed by Italy and Portugal with two each.[1][2] The youngest winner was Ronaldo, who won at 20 years old in 1996, and the oldest winner was Fabio Cannavaro, who won aged 33 in 2006.[3][4] Ronaldo and Zinedine Zidane each won the award three times, while Ronaldo and Ronaldinho were the only players to win in successive years. From 2010 to 2015, the equivalent men’s award was the FIFA Ballon d’Or, following a merging of the FIFA World Player of the Year and the France Football Ballon d’Or awards.[5][6] Since 2016, the awards have been replaced by The Best FIFA Men’s Player and The Best FIFA Women’s Player awards.[7]

Eight women’s footballers – three Germans, three Americans, one Brazilian, and one Japanese – have won the award. Marta, the youngest recipient at age 20 in 2006, has won five successive awards, the most of any player. Birgit Prinz won three times in a row and Mia Hamm won twice in a row. The oldest winner is Nadine Angerer, who was 35 when she won in 2013; she is also the only goalkeeper of either sex to win.

Voting and selection processEdit

The winners are chosen by the coaches and captains of national teams as well as by international media representatives invited by FIFA.[8] In a voting system based on positional voting, each voter is allotted three votes, worth five points, three points and one point, and the three finalists are ordered based on total number of points. Following criticism from some sections of the media over nominations in previous years, FIFA has since 2004 provided shortlists from which its voters can select their choices.[9]

FIFA World Player of the YearEdit

| Year | Rank | Player | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 1st | Lothar Matthäus | Inter Milan | 128 |

| 2nd | Jean-Pierre Papin | Marseille | 113 | |

| 3rd | Gary Lineker | Tottenham Hotspur | 40 | |

| 1992 | 1st | Marco van Basten | Milan | 166 |

| 2nd | Hristo Stoichkov | Barcelona | 88 | |

| 3rd | Thomas Häßler | Roma | 61 | |

| 1993 | 1st | Roberto Baggio | Juventus | 152 |

| 2nd | Romário[note 1] | Barcelona | 84 | |

| 3rd | Dennis Bergkamp[note 2] | Inter Milan | 58 | |

| 1994 | 1st | Romário | Barcelona | 346 |

| 2nd | Hristo Stoichkov | Barcelona | 100 | |

| 3rd | Roberto Baggio | Juventus | 80 | |

| 1995 | 1st | George Weah[note 3] | Milan | 170 |

| 2nd | Paolo Maldini | Milan | 80 | |

| 3rd | Jürgen Klinsmann[note 4] | Bayern Munich | 58 | |

| 1996 | 1st | Ronaldo[note 5] | Barcelona | 329 |

| 2nd | George Weah | Milan | 140 | |

| 3rd | Alan Shearer[note 6] | Newcastle United | 123 | |

| 1997 | 1st | Ronaldo[note 7] | Inter Milan | 480 |

| 2nd | Roberto Carlos | Real Madrid | 85 | |

| 3rd | Dennis Bergkamp | Arsenal | 62 | |

| Zinedine Zidane | Juventus | |||

| 1998 | 1st | Zinedine Zidane | Juventus | 518 |

| 2nd | Ronaldo | Inter Milan | 164 | |

| 3rd | Davor Šuker | Real Madrid | 108 | |

| 1999 | 1st | Rivaldo | Barcelona | 543 |

| 2nd | David Beckham | Manchester United | 194 | |

| 3rd | Gabriel Batistuta | Fiorentina | 79 | |

| 2000 | 1st | Zinedine Zidane | Juventus | 370 |

| 2nd | Luís Figo[note 8] | Real Madrid | 329 | |

| 3rd | Rivaldo | Barcelona | 263 | |

| 2001 | 1st | Luís Figo | Real Madrid | 250 |

| 2nd | David Beckham | Manchester United | 238 | |

| 3rd | Raúl | Real Madrid | 96 | |

| 2002 | 1st | Ronaldo[note 9] | Real Madrid | 387 |

| 2nd | Oliver Kahn | Bayern Munich | 171 | |

| 3rd | Zinedine Zidane | Real Madrid | 148 | |

| 2003 | 1st | Zinedine Zidane | Real Madrid | 264 |

| 2nd | Thierry Henry | Arsenal | 200 | |

| 3rd | Ronaldo | Real Madrid | 176 | |

| 2004 | 1st | Ronaldinho | Barcelona | 620 |

| 2nd | Thierry Henry | Arsenal | 552 | |

| 3rd | Andriy Shevchenko | Milan | 253 | |

| 2005 | 1st | Ronaldinho | Barcelona | 956 |

| 2nd | Frank Lampard | Chelsea | 306 | |

| 3rd | Samuel Eto’o | Barcelona | 190 | |

| 2006 | 1st | Fabio Cannavaro[note 10] | Real Madrid | 498 |

| 2nd | Zinedine Zidane | Real Madrid | 454 | |

| 3rd | Ronaldinho | Barcelona | 380 | |

| 2007 | 1st | Kaká | Milan | 1,047 |

| 2nd | Lionel Messi | Barcelona | 504 | |

| 3rd | Cristiano Ronaldo | Manchester United | 426 | |

| 2008 | 1st | Cristiano Ronaldo | Manchester United | 935 |

| 2nd | Lionel Messi | Barcelona | 678 | |

| 3rd | Fernando Torres | Liverpool | 203 | |

| 2009 | 1st | Lionel Messi | Barcelona | 1,073 |

| 2nd | Cristiano Ronaldo[note 11] | Real Madrid | 352 | |

| 3rd | Xavi | Barcelona | 196 |

Source:[1]

From 2010 to 2015, the award was merged with the Ballon d’Or to become the FIFA Ballon d’Or in a six-year partnership with France Football. In 2016, FIFA rebranded the award as The Best FIFA Men’s Player.

A single article from the Portuguese magazine A Bola reporting about the 1992 award mentions the former award winners Lothar Matthäus in 1991, but also Diego Maradona in 1990. There is no other evidence of the award being presented by FIFA prior to 1991.[10]

Wins by playerEdit

Wins by countryEdit

Wins by clubEdit

FIFA Women’s World Player of the YearEdit

| Year | Rank | Player | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 1st | Mia Hamm | Washington Freedom | 154 |

| 2nd | Sun Wen | Atlanta Beat | 79 | |

| 3rd | Tiffeny Milbrett | New York Power | 47 | |

| 2002 | 1st | Mia Hamm | Washington Freedom | 161 |

| 2nd | Birgit Prinz | 1. FFC Frankfurt Carolina Courage |

96 | |

| 3rd | Sun Wen | Atlanta Beat Shanghai SVA |

58 | |

| 2003 | 1st | Birgit Prinz | Carolina Courage 1. FFC Frankfurt |

268 |

| 2nd | Mia Hamm | Washington Freedom | 133 | |

| 3rd | Hanna Ljungberg | Umeå IK | 84 | |

| 2004 | 1st | Birgit Prinz | 1. FFC Frankfurt | 376 |

| 2nd | Mia Hamm | Washington Freedom | 286 | |

| 3rd | Marta | Santa Cruz Umeå IK |

281 | |

| 2005 | 1st | Birgit Prinz | 1. FFC Frankfurt | 513 |

| 2nd | Marta | Umeå IK | 429 | |

| 3rd | Shannon Boxx | Ajax America Women | 235 | |

| 2006 | 1st | Marta | Umeå IK | 475 |

| 2nd | Kristine Lilly | KIF Örebro DFF | 388 | |

| 3rd | Renate Lingor | 1. FFC Frankfurt | 305 | |

| 2007 | 1st | Marta | Umeå IK | 988 |

| 2nd | Birgit Prinz | 1. FFC Frankfurt | 507 | |

| 3rd | Cristiane | VfL Wolfsburg | 150 | |

| 2008 | 1st | Marta | Umeå IK | 1,002 |

| 2nd | Birgit Prinz | 1. FFC Frankfurt | 328 | |

| 3rd | Cristiane[note 12] | Corinthians | 275 | |

| 2009 | 1st | Marta[note 13] | Santos | 833 |

| 2nd | Birgit Prinz | 1. FFC Frankfurt | 290 | |

| 3rd | Kelly Smith[note 14] | Boston Breakers | 252 | |

| 2010 | 1st | Marta | FC Gold Pride | 38.20% |

| 2nd | Birgit Prinz | 1. FFC Frankfurt | 15.18% | |

| 3rd | Fatmire Bajramaj | 1. FFC Turbine Potsdam | 9.96% | |

| 2011 | 1st | Homare Sawa | INAC Kobe Leonessa | 28.51% |

| 2nd | Marta[note 15] | Western New York Flash | 17.28% | |

| 3rd | Abby Wambach | magicJack | 13.26% | |

| 2012 | 1st | Abby Wambach | Unattached | 20.67% |

| 2nd | Marta | Tyresö FF | 13.50% | |

| 3rd | Alex Morgan | Seattle Sounders | 10.87% | |

| 2013 | 1st | Nadine Angerer[note 16] | Brisbane Roar | 18.85% |

| 2nd | Abby Wambach | Western New York Flash | 15.02% | |

| 3rd | Marta | Tyresö FF | 14.02% | |

| 2014 | 1st | Nadine Keßler | VfL Wolfsburg | 17.52% |

| 2nd | Marta[note 17] | FC Rosengård | 14.16% | |

| 3rd | Abby Wambach | Western New York Flash | 13.33% | |

| 2015 | 1st | Carli Lloyd | Houston Dash | 35.28% |

| 2nd | Célia Šašić | 1. FFC Frankfurt | 12.60% | |

| 3rd | Aya Miyama | Okayama Yunogo Belle | 9.88% |

Source:[1]

In 2016, FIFA created The Best FIFA Women’s Player award instead.

Wins by playerEdit

Wins by countryEdit

Wins by clubEdit

See alsoEdit

- List of sports awards honoring women

- Ballon d’Or

- FIFA Ballon d’Or

- The Best FIFA Football Awards

- FIFPRO World 11

NotesEdit

- ^ Romário was signed by Barcelona from PSV Eindhoven midway through 1993.

- ^ Bergkamp was signed by Inter Milan from Ajax midway through 1993.

- ^ Weah was signed by Milan from Paris Saint-Germain midway through 1995.

- ^ Klinsmann was signed by Bayern Munich from Tottenham Hotspur midway through 1995.

- ^ Ronaldo was signed by Barcelona from PSV Eindhoven midway through 1996.

- ^ Shearer was signed by Newcastle United from Blackburn Rovers midway through 1996.

- ^ Ronaldo was signed by Inter Milan from Barcelona midway through 1997.

- ^ Figo was signed by Real Madrid from Barcelona midway through 2000.

- ^ Ronaldo was signed by Real Madrid from Inter Milan midway through 2002.

- ^ Cannavaro was signed by Real Madrid from Juventus midway through 2006.

- ^ Cristiano Ronaldo was signed by Real Madrid from Manchester United midway through 2009.

- ^ Cristiane was signed by Corinthians from Linköpings F.C. midway through 2008.

- ^ Marta was signed by Santos from Los Angeles Sol midway through 2009.

- ^ Smith was signed by Boston Breakers from Arsenal Ladies midway through 2009.

- ^ Marta was signed by Western New York Flash from Santos midway through 2011.

- ^ Angerer was signed by Brisbane Roar from 1. FFC Frankfurt midway through 2013.

- ^ Marta was signed by FC Rosengård from Tyresö FF midway through 2014.

ReferencesEdit

- ^ a b c «FACTSheet FIFA awards» (PDF). FIFA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ «FIFA Awards». RSSSF.com. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ «Brazil legend Ronaldo retires from football». BBC Sport. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ «Cannavaro discusses highs and lows». Football Federation Australia. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ «The FIFA Ballon d’Or is born». FIFA.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ «FIFA Ballon d’Or World Player of the Year: Award History». FIFA.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ «The birth of The Best FIFA Football Awards». FIFA.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ «Messi, Lloyd, Luis Enrique and Ellis triumph at FIFA Ballon d’Or 2015». FIFA. 12 January 2016. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ «Thirty-five stars make Zurich shortlist». FIFA.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ «Guerin Sportivo World Player of the Year awards 1979-1986». BigSoccer Forum. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

In this age of misinformation—of “fake news,” conspiracy theories, Twitter trolls, and deepfakes—gaslighting has emerged as a word for our time.

A driver of disorientation and mistrust, gaslighting is “the act or practice of grossly misleading someone especially for one’s own advantage.” 2022 saw a 1740% increase in lookups for gaslighting, with high interest throughout the year.

Its origins are colorful: the term comes from the title of a 1938 play and the movie based on that play, the plot of which involves a man attempting to make his wife believe that she is going insane. His mysterious activities in the attic cause the house’s gas lights to dim, but he insists to his wife that the lights are not dimming and that she can’t trust her own perceptions.

When gaslighting was first used in the mid 20th century it referred to a kind of deception like that in the movie. We define this use as:

: psychological manipulation of a person usually over an extended period of time that causes the victim to question the validity of their own thoughts, perception of reality, or memories and typically leads to confusion, loss of confidence and self-esteem, uncertainty of one’s emotional or mental stability, and a dependency on the perpetrator

But in recent years, we have seen the meaning of gaslighting refer also to something simpler and broader: “the act or practice of grossly misleading someone, especially for a personal advantage.” In this use, the word is at home with other terms relating to modern forms of deception and manipulation, such as fake news, deepfake, and artificial intelligence.

The idea of a deliberate conspiracy to mislead has made gaslighting useful in describing lies that are part of a larger plan. Unlike lying, which tends to be between individuals, and fraud, which tends to involve organizations, gaslighting applies in both personal and political contexts. It’s at home in formal and technical writing as well as in colloquial use:

Patients who have felt that their symptoms were inappropriately dismissed as minor or primarily psychological by doctors are using the term “medical gaslighting” to describe their experiences and sharing their stories.— The New York Times, 28 March 2022

The “I’m sorry you feel that way” approach, along with avoiding an argument in lieu of admitting fault, is good old fashioned gaslighting. — Psychology Today, 29 March 2022

My Committee’s investigation leaves no doubt that, in the words of one company official, Big Oil is ‘gaslighting’ the public. These companies claim they are part of the solution to climate change, but internal documents reveal that they are continuing with business as usual. — Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney, Chairwoman of the Committee on Oversight and Reform, 14 September 2022

After their fight awkwardly cleared the daybed, the two parted ways and Genevieve caught Victoria up on the unexpected blowout. “He told me I’m gaslighting him. I’ve never even been told that in my life,” Gen said. “Yeah that’s a big word to use… He doesn’t know what that means. He’s just using a buzzword, he’s stupid. He’s dumb,” Victoria replied. — Nicole Gallucci, Decider (decider.com), 2 November 2022

English has plenty of ways to say “lie,” from neutral terms like falsehood and untruth to the straightforward deceitfulness and the formally euphemistic prevarication and dissemble, to the innocuous-sounding fib. And the Cold War brought us the espionage-tinged disinformation.

In recent years, with the vast increase in channels and technologies used to mislead, gaslighting has become the favored word for the perception of deception. This is why (trust us!) it has earned its place as our Word of the Year.

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, countries including the U.S. and United Kingdom placed sanctions on Russian oligarchs and their families. Lookups for oligarch spiked 621% in early March 2022.

In its Greek roots oligarchy literally means “rule by the few.” In English the word can carry the same meaning, but it also has a meaning specific to Russia and other countries that succeeded the Soviet Union:

: one of a class of individuals who through private acquisition of state assets amassed great wealth that is stored especially in foreign accounts and properties and who typically maintain close links to the highest government circles

Throughout 2022 we have seen stories about various authorities seizing the yachts owned by these rich Russian allies of President Putin.

The war in Ukraine has also driven spikes in lookups for sanction, Armageddon, and conscript.

The World Health Organization uses Greek letters (alpha, beta, gamma, delta) to designate variants of the COVID virus. In November 2021, it used omicron, the 15th letter of the Greek alphabet, to name the most recent version of the virus. That variant became one of the most widespread forms of COVID in 2022.

Major spikes in lookups accompanied a surge in cases in early January, and following reports in November that the omicron booster was not significantly more effective than the older vaccines.

Endemic, used to describe a disease that is constantly present in a particular place, increased 874% in January.

Photo: Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Lookups for codify increased 193% for the year in 2022, driven by the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade on June 24th.

Codify refers to a process by which Congress can make laws; the word literally means “to make a code” with code here essentially a synonym of “law.” Code ultimately comes from the Latin word codex, meaning “trunk of a tree,” referring to documents on wooden tablets.

There were several notable spikes in lookups of codify:

May 3 (leak of the draft of the Dobbs v. Jackson decision): 5347%

June 24 (the decision announcement): 1293%

June 30 (President Biden’s endorsement of ending the filibuster in order to codify the right to abortion): 8304%

We also saw spikes in other lookups connected to this story: abortion lookups were higher in June, and both take for granted and mercurial, used to describe Chief Justice John Roberts, were higher in May.

The acronym LGBTQIA adds some letters to the older and more familiar abbreviations LGBT and LGBTQ, with the full abbreviation standing for “lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning (one’s sexual or gender identity), intersex, and asexual/aromantic/agender.”

The abbreviation was looked up frequently (up 1178%) during the entire month of June, Pride month, when the rights, equality, and culture of LGBTQ people are celebrated around the world. Lookups also spiked in late November after the shooting at a gay nightclub in Colorado Springs. With LGBTQ and the longer acronym both used in news stories about the event, interest in the difference between the two was apparent. Overall, LGBTQIA saw an 800% increase over 2021.

In June, when a Google engineer claimed the company’s AI chatbot had developed a human-like consciousness, lookups of sentient increased 480%. The claim was vigorously denied by Google, and the engineer was placed on paid leave, but the question of how human-like AI is, or will be, became a topic of much interest.

Loamy

2022 was also the year that many people discovered the joy in puzzling out five-letter words: both Wordle (in which the puzzler has six tries to identify one word) and Quordle (nine guesses to identify four words) sent people to the dictionary, with numerous seldom-searched-for words tapped out on keyboards everywhere. When loamy (“consisting of loam, a soil consisting of a friable mixture of varying proportions of clay, silt, and sand”) was a Quordle answer on August 29th, the entry surged 4.5 million percent. In May, the Quordle answer voilà inspired a lookup spike of 2.5 million percent.

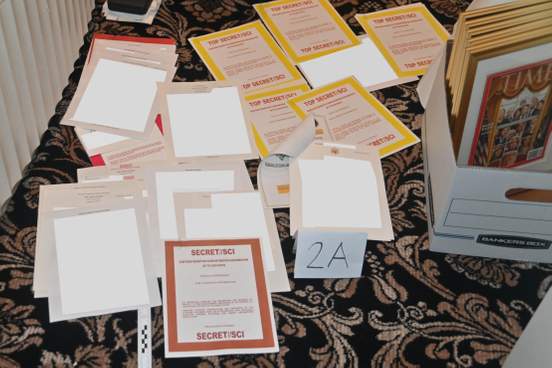

Photo: United States Department of Justice

When the FBI executed a search warrant at former president Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home in early August, the event was labeled by some as a “raid,” sending lookups of raid up 970%. The relevant meaning of raid, “a sudden invasion by officers of the law,” was used to suggest that the search was unfair. In late August the Justice Department responded to that charge by releasing a redacted affidavit, sending lookups of redact and redacted up 1000%.

For the remainder of the year, this story created additional spikes in lookups. The large quantity of documents—33 boxes’ worth—was often called a “trove” by journalists, a trove being a valuable collection, or more generally a large amount of something collected. Trove was up 344% for the year. Defenders of the former president accused the government of behaving like a banana republic—that is, like a small and despotically run country, driving a lookup increase of of 3750%.

The death of Queen Elizabeth II was the end of an era, and the focus of international attention and fascination. The public’s interest in the monarchy is often connected with the ceremonies and rituals of the institution, including coronations, royal weddings—and funerals. Among the most looked-up terms following the Queen’s death was pomp and circumstance, as images of processions and pageantry were broadcast around the world. Monarch itself was also looked up frequently.

Announcements of the Queen’s death acknowledged the new King and his wife, Camilla, referred to by her proper title of Queen Consort, and that term quickly shot to the top of lookups. Since England had not had a king since 1952, it’s understandable that this title was unfamiliar. Camilla is not the successor to the Queen, but is instead the wife of the reigning king. A parallel title for the husband of a reigning queen, prince consort, was the title held by the late Prince Philip.

Another royal milestone sent people to the dictionary in May and June to look up jubilee, meaning “a special anniversary.” The term described the official celebrations for Queen Elizabeth’s unprecedented 70th anniversary on the throne.

Words games may seem like of the simplest games to play, but make no mistake they can be just as challenging as the toughest puzzle games. They can also be immensely fun especially since many of them allow you to play with others through some sort of online multiplayer or Co-op feature, although not all of them allow this. Whether you like playing word games by yourself or with others though, there’s no doubt these tongue twisting word filled masterpieces will keep you coming back for more. Expand you vocabulary and check out our picks for the best Word game of the year.

Winner: Lex

Lex is a wonderful little word game that seeks to not only delight your affinity for language, but it also wants to delight your senses a little bit by introducing some cool features like the kaleidoscope images that appear on screen as you pick letters. It also adds in some breath taking music and adds an element of urgency by giving you a time limit with which to get as many words on screen as you can to form points. The soundtrack is also player generated just the like the imagery, being conducted by every move you make. It includes leaderboards and achievements for those who have a competitive side and love to get a hold of those bragging rights. Think you got what it takes to best Lex?

Runner Up: Synonymy

If you love words, then you absolutely have to check out Synonymy. Instead of tasking you with finding words to put up on a board from a set of letters given to you, Synonymy asks you to to uncover the paths between two seemingly un-linked words by finding the synonyms of words placed in front of you on screen. The words you’re given in this game may seem random, but there is a network of synonyms between them that led from one word to the other, and your job is to find them. The game supports multiplayer and weekly challenges where you can compete to set the start and end words added in future updates in the game. It may seem tough if you don’t know enough about synonyms, but this would make for good practice and nice little challenge right?

Honorable Mention:

CardCast

Technology

Best Free VPN to Use in 2023 – Expert’s Top Pick

Smriti Razdan — February 14, 2023

Using the internet and scrolling through different websites is now our daily habit, but along with that, we need to focus on security. Day by day, the cases of hacking are increasing, so you need to keep your eyes…

The Oxford word of the year will be voted for by the public for the first time, it has been announced. Since “the true arbiters of language” are “people around the world”, Oxford Languages has decided to put the final decision on the 2022 word in the hands of the English-speaking public.

Voting is now open online, and over the next two weeks English speakers can cast their vote, choosing from three words selected by Oxford University Press (OUP)’s lexicographers, each of which is believed to capture “the mood and ethos of the last year in its own way”. The shortlisted words are “goblin mode”, a slang term that refers to behaviour that is “unapologetically self-indulgent, lazy, slovenly, or greedy, typically in a way that rejects social norms or expectations”; “#IStandWith”, a hashtag used to express solidarity online; and “metaverse”, a term coined in Neal Stephenson’s 1992 science-fiction novel Snow Crash to refer to a virtual reality environment, which has seen a dramatic growth in usage over the past year.

Casper Grathwohl, president of Oxford Languages, said the decision to open the final call to the public was partly due to living in a “post-Covid era”.

“Over the past year the world reopened, and it is in that spirit we’re opening up the selection process for the word of the year to language-lovers everywhere,” he said. “We are all participants in the evolving story of English, and after making it through another hard year we thought word-lovers would appreciate being brought into the process with us.”

The “word” of the year has come to be defined somewhat loosely, as it is open to slang terms such as last year’s choice “vax” as well as compound words and phrases. Eyebrows may well be raised by the inclusion of a hashtag on this year’s shortlist, but senior editor at OUP Fiona McPherson said that while hashtags are technically “a stylised form of word”, they are eligible for the word of the year because they are “a really important feature” of current language usage. She also noted that people have begun to refer to hashtags in spoken as well as in written English.

Discussing the first part of the 2022 selection process, McPherson and fellow senior editor Jonathan Dent revealed some of the words that were in contention for the shortlist, including “platty jubes” and “quiet quitting”. Ultimately, however, the three shortlisted words were identified using OUP’s data as having experienced a dramatic spike in usage as well as having “captured one of the significant preoccupations of the year”.

In a further move to engage with the public, OUP will be sharing insights into the grammatical and linguistic behaviour of all three choices on the shortlist throughout the voting period, while encouraging social media users to use the hashtags #TeamMetaverse, #TeamGoblinMode, or #TeamIStandWith.

Voting will close on 2 December, and the word of the year will be announced on 5 December.