-

#1

Hello, folks. I’m reading a Shirley Jackson’s story -The Lottery- and I came across this expression or word or whatever it is I can’t understand. Here you are:

“Thought my old man was out back stacking wood,” Mrs. Hutchinson went on, “and then I looked out the window and the kids was gone, and then I remembered it was the twenty-seventh and came a-running.”

What does a-running mean? I haven’t a clue, but I guess it can be a very simple thing. Could you help me?

Thank you, Bones.

-

#2

It’s colloquial, and it’s just a variation of running.

He came a-calling.

I came a-running.

She went a-screaming.

It’s rather old fashioned these days, something you’d expect to hear from older folks.

-

#3

Thank you, nyc. But I don’t understand if this adds some quality or something to the current word. Is a-running a faster way to run, for example? Thank you, Bones.

-

#4

A-running means that they have more incentive to arrive to the place to which they are running.

When I told her there were bagels in the conference room, she came a-running.

The same applies with the others:

She refused to come over for dinner, but she came a-calling when she needed someone to feed her cat for the weekend.

Bien

-

#5

Thank you, Bienvenidos. Bones.

-

#6

Another interesting lesson, though not much use in modern English as we tend not to use the a-prefix versions these days.

The a- prefix to verbs of motion, in particular, is an intensifier.

Here is what the OED says after lengthy explanations about the different reasons that words acquired a- prefixes …

Hence, it naturally happened that all these a- prefixes were at length confusedly lumped together in idea, and the resultant a- looked upon as vaguely intensive, rhetorical, euphonic, or even archaic, and wholly otiose.

Don’t you just love the sound of that sentence

-

#7

Don’t you just love the sound of that sentence

![Smile :) :)]()

Yes indeed. Thank you, Panj.

-

#8

Hi everyone, I’ve been reading Oliver Twist, by Charles Dickens and I find it somehow difficult to understand, at least for an english learner like me… I’m keeping a doubt for about some time and I thought that maybe you guys could help me figuring it out: there’s a constant writing of the verbs composed of an ‘a’ and the verb in the gerund. For ex.: «I was only a-telling, a-coming, a-going to say». I know this book comes from a very different epoch, and these expressions come, so far, from very peculiar characters, but I was wondering what does it have to do with? is it simply derived from the pronunciation, or something else? Is it normal?

Thank you for any eventual answer to this doubt!

-

#9

I believe it is probably meant to be street dialect for the time. It also serves to develop the character through the use of the singsong sound of a-going, a-doing etc. No, it is not common usage.

-

#11

The use of a- before any gerund/participle is old — recorded from the 16th century.

Two meanings are noted, both seeming to reinforce the verb:

Engaged in — The bells are a-ringing, the band is a-playing.

Motion to, into — I’m going a-shopping. The bus is a-coming.

Over time the a- prefix has been omitted, but it remained in colloquial speech until broadcast media wiped it out.

(Paraphrased from the OED and Fowler, with a touch of embroidery.)

So I expect that Dickens’ use of this form reflects its ongoing use in common speech in the 19th century.

Still, what’s good enough for Dylan ….

(The times they are a-changin’)

-

#12

Of course! How could I have forgotten Bob?

-

#13

Ahh, also let’s not forget ‘And a Partridge in a Pear Tree’, the sixteenth century Christmas Carol, so definitely archaic.

On the seventh day of Christmas,

my true love sent to me

Seven swans a-swimming,

Six geese a-laying, …and so on.

-

#14

a-prefixing is not necessarily archaic. It’s still quite common in Appalachian English.

Anais

Ahh, … so definitely archaic.

On the seventh day of Christmas,

my true love sent to me

Seven swans a-swimming,

Six geese a-laying, …and so on.

-

#15

That is really interesting! I really don’t know much about Appalachian English, but could it be considered a dialect based on archaic English? Just curious…

-

#17

Thanks Anais, I went a-hunting where you suggested and found Michael’s article very interesting. Whatever the origin, it is really quite evocative and musical language with its own quite specific rules of usage!

-

#18

My grandmother and mother’s older sisters used a’

with a verb—usually a’fixin’

Example:

He was a’fixin’ to go to the store.

I think my brother-in-law in Missouri still uses the a’fixin’ to do something.

-

#19

The use of a- before present participles is old-fashioned or dialectal; but the insertion of an extra schwa before past participles in some contexts is alive and well in speech, e.g. ‘If I hadn’t a-been here… ‘

-

#20

The use of a- before present participles is old-fashioned or dialectal; but the insertion of an extra schwa before past participles in some contexts is alive and well in speech, e.g. ‘If I hadn’t a-been here… ‘

I don’t think that’s the insertion of something extra. Is it not the mark of the abridgement of something which shouldn’t have been there to begin with? It’s probably easier to explain if I change the negative to positive here — «If I had have been there». Sometimes «of» is used instead of the ‘have’ — particularly in Ireland —> «If I had of been there» Ouch!

-

#21

Yes Maxiogee, I agree with the ‘a’ being an abridgement. Sentences like ‘he was a-fixing to go to the store’ contain a gerund since ‘a’ really means that ‘he was bent on going’ to the store.

-

#22

Yes Maxiogee, I agree with the ‘a’ being an abridgement.

My hypothesis is that the ‘a-‘ pronounced in ‘If I hadn’t a-been’ is not an abridgement of anything, but is the same syllable as regularly appears before past participles in written Middle and Old English, for example the i in icumen here http://www.bartleby.com/101/1.html. In this hypothesis, forms such as ‘If he hadn’t of been’ or ‘If he hadn’t have been’ are overcorrections / hypercorrections committed by speakers who would naturally say ‘a-been’ but don’t know how to write or say this a- in standard English.

There was a thread on this subject but I can’t find it!

-

#24

As an afterthought, don’t we still use this form in words like «awaiting»?

-

#25

I suppose not, since that verb is formed by the latin element ad- ...

-

#26

I don’t detect any real difference of meaning between the a-verbing and verbing versions, so I’m not convinced you need to worry about these in translation. Of course these forms may be used to create an archaic effect in English. I don’t know if you can find any equivalent technique in another language — I mean, a way to use your own language to create the same effect as a- prefixes create in English.

-

#27

England. Year 1775.

Mr. A told something really odd to Mr. B, so that Mr. B would report it to other people. B says: «Bust me if I don’t think he’d been a drinking!». I guess this is a colloquial manner of speech to say «if I don’t think he had been drinking».

-

#28

Hello again Veraz. That a- is a prefix you used to see a lot on the front of -ing words (it’s a relic from Old English ge-, I believe). It now sounds

very

old-fashioned, but folk sometimes still use it for comic effect.

-

#29

I would rather say «archaic», than «old-fashioned», and I’m sure Ewie would agree.

You will see a’ + present participle in lots of old folk songs, but don’t use it today!

Let us go a’dancing-oh!

Have you been a’courting today?

He was a’singing and a’playing the fiddle like a man possessed by the fairies!

-

#30

Thank you again, ewie!

And thank you, Emma!

-

#31

Hello again Veraz. That a- is a prefix you used to see a lot on the front of -ing words (it’s a relic from Old English ge-, I believe). It now sounds

very

old-fashioned, but folk sometimes still use it for comic effect.

Absolutely, but not just in front of -ing words. The Oxford English Dictionary gives the example ‘a bed’ as meaning ‘in bed’. A quotation from Shakespeare’s Macbeth (II. i.12) is given: «The King’s a bed». The words ‘alive’, ‘asleep’ etc are formed on the same basis. This preposition ‘a’ is described as a ‘worn out proclitic’ and the entry also gives ‘a begging’ under the same heading.

-

#32

Hello again Veraz. That a- is a prefix you used to see a lot on the front of -ing words (it’s a relic from Old English ge-, I believe). It now sounds

very

old-fashioned, but folk sometimes still use it for comic effect.

Actually, there are dialects in the U.S. where this is still very common.

«He commenced to pitch a fit, a-cussin’ and a-swearin’ to beat the band!»

Strangely enough, I found an example of this in print, from a Massachusetts newspaper in 1997:

http://archive.southcoasttoday.com/daily/08-97/08-22-97/c01li098.htm

He’s Cussin’ and Lovin’ it

Maybe it’s a generational thing. Most everyone I hang around with swears as much as I do, some even more. But my grandparents would definitely be horrified if they could observe me in my natural state, a-cussin’ and a-swearin’. My grandfather, who is far from a taciturn type of man, gets a stern look on his face when I say, «Wow, it’s hot as hell in here.»

Loretta Lynn sang a song with the title: «Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’ with Lovin’ On Your Mind».

-

#33

This is very interesting! Lost in England but alive and kicking in the States.

-

#34

I agree with JamesM. Here in Tennessee it’s not uncommon to hear it at all!

-

#35

This is very interesting! Lost in England but alive and kicking in the States.

Actually, that happens a lot.

-

#37

Thinking more about it, I wouldn’t be at all surprised if this construction were not still kicking around in a few dialects in the UK; the south west springs to mind (Dorset, Devon etc). I am guessing, though.

-

#38

I was trying (in post #2) to avoid saying No-one’s used this construction since 1823 because, as I suspected and JamesM and Sísepuede have since confirmed, it’s alive and well in certain parts of the English-speaking world. (Perhaps, yes, in the Southwest of the UK too, Emma.)

I wasn’t going to go into the fact that I use it often in my own writing [fiction] ~ more to add a kind of quirkiness than for outright comic effect.

It seems to me one of those curious phenomena in English: anyone who’s ever read just about anything, or seen just about any film set in a period before the 20th century, or listened to Loretta Lynn (!), will have heard it and be familiar with it … and yet it is no longer at all used in ~ ahem ~ ‘mainstream’ English.

-

#39

Yes, it’s indeed still used a lot in the US. Mostly only in rural areas, though. It would be rather funny to hear someone with a strong New Yorker accent say something like «a-walkin'».

-

#40

This usage is still alive and ‘a kicking’ in the south west of England!

-

#41

Hello again Veraz. That a- is a prefix you used to see a lot on the front of -ing words (it’s a relic from Old English ge-, I believe). It now sounds

very

old-fashioned, but folk sometimes still use it for comic effect.

I was thinking about what you say here, Ewie. I’m not at all acquainted with Old English, but since it «shared blood» with present-day German, I guess this «ge-» went only before past participles, not gerunds or present participles. In the other thread someone has talked about «a-» before past participles too.

-

#42

The OED says that the a-verbing form derives from a worn-down proclitic form of the Old English preposition an, on.

-

#44

Sorry for the false trail: that was just a guess on my part.

(But yes, Veraz, I’m pretty certain that Old English ge- and Modern German ge- are exactly the same thing, a kind of ‘advance warning’ that a past participle is on the way.)

-

#45

Absolutely, but not just in front of -ing words. The Oxford English Dictionary gives the example ‘a bed’ as meaning ‘in bed’. A quotation from Shakespeare’s Macbeth (II. i.12) is given: «The King’s a bed». The words ‘alive’, ‘asleep’ etc are formed on the same basis. This preposition ‘a’ is described as a ‘worn out proclitic’ and the entry also gives ‘a begging’ under the same heading.

Other examples of it occurring in current standard speech in a form no longer obvious to the average native speaker of English, taken from page 2 of The Century Dictionary (available online), are the a in nowadays and the a in twice a day. The latter has undergone a reinterpretation to make it an example of the indefinite article, changing to an before a vowel sound, as in four miles an hour.

-

#46

The a- prefix appears in the following songs by Bob Dylan:

«The times they’re a-changing», «A hard rain’s a-gonna fall».

Is it archaic or something? Does it change the meaning of the verb somehow?

-

#47

I believe there’s a couple of previous threads about this but I can’t find them. It does not change the meaning at all. I believe that it’s AE jargon that came from uneducated portions of the US decades ago. I believe that Dylan wrote some of his songs that way to convey that «poor working man» quality.

-

#49

It’s been around for a long time, and it’s not only American. Here’s the OED: an edited version of sense 11 (and retaining only one example for each sub-sense).

11. Expressing action, with a verbal noun or gerund taken actively. Now arch. and regional.

a. After be (or occasionally another verb expressing state) and before a verbal noun: engaged in (some activity). Also with of and object. Cf. IN prep.1 11c, ON prep. 12b.

N.E.D. (1884) states: ‘In literary English the a is omitted, and the verbal noun treated as a participle agreeing with the subject, and governing its case, to be fishing, fighting, making anything. But most of the southern dialects, and the vulgar speech both in England and America, retain the earlier usage.’ 2003 Daily Tel. 18 Nov. 23/1 The invitation has been such a long time a-coming.b. After a verb denoting or implying motion and before a verbal noun: to, into (some action). Cf. IN prep.1 11c, ON prep. 23.

2005 Daily Tel. 20 June 9/1 Eligible bachelors..meet marriageable ladies..at a country pub to go a-courting in the Cotswolds.c. Before the gerund of a transitive verb and its object. 2000 O. SENIOR in N. Hopkinson Whispers from Cotton Tree Root 139 This fish not just moving, it dancing. A-wiggling and a-moving its tail.

d. Before a gerund used as subject or object complement generally, equivalent to (and generally considered to be) a present participle. 2006 Nature 4 May p. vii/1 Male túngara frogs a-wooing produce a species-specific call to attract females.

-

#50

Lyric writers often use this device as a way of adding an extra unstressed syllable to fit the scansion of the line.

Rover

In syntax, verb-initial (V1) word order is a word order in which the verb appears before the subject and the object. In the more narrow sense, this term is used specifically to describe the word order of V1 languages (a V1 language being a language where the word order is obligatorily or predominantly verb-initial). V1 clauses only occur in V1 languages and other languages with a dominant V1 order displaying other properties that correlate with verb-initiality and that are crucial to many analyses of V1.[1] V1 languages are estimated to make up 12–19% of the world’s languages.[2]

V1 languages constitute a diverse group from different language families. They include Berber, Biu-Mandara, Surmic, and Nilo-Saharan languages in Africa; Celtic languages in Europe; Mayan and Oto-Manguean languages in North and Central America; Salish, Wakashan, and Tsimshianic languages in North America; Arawakan languages in South America; Austronesian languages in Southeast Asia.[1] Some languages are ordered strictly as verb-subject-object (VSO), for example Q’anjob’al (Mayan). Others are ordered strictly as verb–object–subject (VOS), for example Malagasy (Austronesian). Many alternate between VSO and VOS, an example being Ojibwe (Algonquian).[1]

Examples[edit]

The following examples illustrate the rigid VOS and VSO languages and the VOS/VSO-alternating languages.:[1]

Q’anjob’al (VSO)

(1)

‘The woman drank coffee.’

Malagasy (VOS)

(2)

‘The chicken saw the rat.’

Ojibwe (VOS/VSO)

(3)

VSO order:

W-gii-sham-a-an

3ERG—PST-feed-3ANIM—OBV

‘The woman fed the blueberries to the child.’

(4)

VOS order:

W-gii-sham-a-an

3ERG—PST-feed-3ANIM—OBV

‘The woman fed the blueberries to the child.’

Word-order correlations[edit]

Verb-initial languages pattern with SVO languages on many of their word orders. The similarity between the word orders typical for both verb-initial languages and SVO languages has led many typologists to refer to all of these as simply VO languages. According to Matthew Dryer’s 1992 study of a worldwide sample of languages, the majority of VO languages (of which verb-initial languages are a subtype) have the following word order tendencies:

Strong tendencies:

- Adjective comes before standard of comparison

- Verb comes before adpositional phrase

- Adpositions come before the noun phrase (i.e. they are prepositions)

- Verb comes before manner adverb

- Copula comes before nominal or adjectival predicate

- Auxiliary comes before verb (for those languages that have auxiliaries)

- Negative auxiliary comes before verb (for those languages that have negative auxiliaries)

- Complementizer comes before sentence

- Adverbial subordinator comes before sentence

Weak tendencies:

- Head noun comes before genitive noun

- Question particle comes before sentence (in those languages that have question particles)

- Article comes before noun (in those languages that have articles)

Theoretical approaches[edit]

Functionalist approach[edit]

Many functional linguists do not posit an underlying syntactic tree in which a verb-initial language is SVO. Rather than try to find ways to derive the structures of verb-initial languages from underlyingly SVO structures, functional linguists would look at how cognitive principles make it possible for languages to have different word orders and why certain word orders are more common, less common, or almost non-existent. Russell Tomlin (in his 1986 paper «Basic word order. Functional principles») argued that there are three cognitively grounded principles which can account for the observed distributions of the frequencies of word order in human languages. The three principles are:

- Topic-first principle (more topical NPs come before less topical NPs)

- Animate-first principle (NPs with more animate referents come before NPs with less animate referents)

- Verb-object bonding principle (objects are more closely linked to the verb than subjects are)

Since subjects are generally more likely than objects to be topics and to have animate referents, the topic-first principle and the animate-first principle both cause a strong tendency in languages to prefer the subject to go before the object. Thus, languages where the object comes before the subject are rare.

Of the three possible word orders in which the subject comes before the object (VSO, SVO, and SOV), the VSO is less common because of the verb-object bonding principle, which states that objects tend to be more closely tied to verbs than subjects are (which is supported by phenomena such as object incorporation being found in many languages). Because of this principle, the two orders in which the object and verb are placed next to each other (SVO and SOV) are more common than VSO.

The way the three principles interact to produce stark differences in frequencies between the word orders is illustrated by the table below (the assumption is that the more of the three principles a particular word order satisfies the more frequent it would be):

| Verb-object bonding principle | Topic-first principle | Animate-first principle | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | yes | yes | yes |

| SVO | yes | yes | yes |

| VSO | no | yes | yes |

| VOS | yes | no | no |

| OVS | yes | no | no |

| OSV | no | no | no |

According to the table above, the application of these three principles would predict the following hierarchy in the relative frequencies of word order:

SOV=SVO > VSO > VOS=OVS > OSV

This prediction roughly corresponds to the real frequencies observed in the world’s languages:

- SOV: 44.8%

- SVO: 41.8%

- VSO: 9.2%

- VOS: 3.0%

- OVS: 1.2%

- OSV: 0.0%

Generative approach[edit]

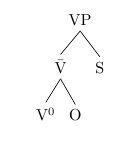

There are a number of different solutions proposed for deriving V1 word order in the generative framework. These solutions include the movement of the verb or verbal phrase from traditional SVO sentences, lowering the subject from a higher position, such as Spec-IP to adjoin to a projection of the verb, or stipulating that the specifier is right branching instead of the more common left branching specifiers found in X-bar theory.

Verb movement[edit]

A common analysis for V1 word order is the head-raising of the verb from a base-generated SVO sentence into a position higher than the subject. This is a popular proposal for Irish and other Celtic languages,[3] but also has been applied to Afroasiatic V1 languages such as Berber and Arabic (Ouhalla 1994). The V0 raising account has also been proposed for a number of Austronesian languages, but there is no existing proposal for Mayan languages.[1]

To derive VSO word order, the verb raises through head movement and raises to either C or T.[1]

Deriving VOS order through V head-raising is less straightforward. The common solution is scrambling, which has been proposed for deriving Tongan (Otsuka 2002) and Tagalog (Rackowski 2002) sentences. The scrambling mechanism involves the object moving to a high position, such as Spec-TP (Otsuka 2002), in order to check information structure features.

The head-movement analysis is motivated by ellipsis data in Celtic and Semitic languages, and by verb-adjacent particles and adverbs in Austronesian languages.

In Irish, eliding all postverbal arguments is possible, suggesting that the subject and the verb belong to one functional projection, and the verb is outside of it (McCloskey 1991).

In Tagalog, there can be adverbs between the verb and the object in VOS order, implying that the verb and the object can be separated, and do not form a constituent.[4] In Tongan, there is an asymmetry between case-marked arguments and clitic pronouns: the clitics surface pre-verbally, whereas the case-marked nouns can only surface post-verbally (Otsuka 2005). Otsuka (2005) proposed that the subject clitic undergoes head-movement to T0, and attaches to the verb, whereas the case-marked subject moves to Spec-TP. He concludes that only verb head-movement can explain such a syntactic asymmetry in Tongan.

Phrasal movement[edit]

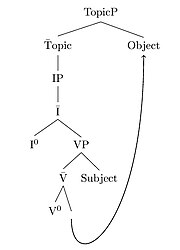

V1 word order can also be analyzed as a derivation from the more common SVO order through verbal phrase movement. This solution is commonly proposed for Austronesian languages.[1] Accounts on phrasal movement differ on 1) the highest maximal projection that moves (VP, vP, or TP), 2) the landing site of the moved phrase (Spec-TP or higher), and 3) the motivation for movement (generally agreed to be the EPP).

VOS order can be derived straightforwardly by raising the VP to a specifier position in a higher projection, such as the TP.

VP movement to derive VOS word order.

VSO order, on the other hand, has to be derived by remnant movement of the VP after evacuating the object from the phrase first.

VP movement to derive VOS word order.

An argument for VP raising is the island constraints that arise in the VP in VOS sentences, due to The Freezing Principle,[5] which says that there can be no movement out of a moved constituent.

Various Austronesian languages follow this constraint to various levels. Seediq for example is strict in that only VP-external constituents can go under A’-movement.[1][6] Toba Batak,[7][8] Tagalog,[1] and Malagasy[1] on the other hand, have this restriction only for VP-internal arguments, while allowing adverbs and indirect objects to surface clause-initially. One proposal to solve this problem is to propose that adjuncts evacuate from the VP, before it raises.[8]

Mayan languages, on the other hand, do not have such a restriction. Ch’ol, for example, allows object extraction in WH-questions from VOS word orders.[9] For such cases, it has been proposed that the object evacuates before the phrasal movement to a higher position than the subject, and thus can undergo WH-movement later.[9]

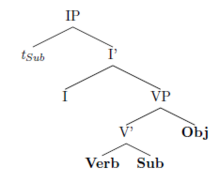

Right-hand specifier[edit]

Verb phrase in X-bar structure with a right specifier.

Demonstration of a possible derivation of VSO word order in a rightward specifier theory.

Some researchers have proposed deriving verb-initial word order by modifying the basic X-bar structure to permit right ward specifiers. This analysis has been particularly influential for Mayan languages, notably by Judith Aissen for Tzotzil.[10] This is notable because it goes against standard X-bar theory and modern Minimalist theories where all specifiers are required to be leftward.

Derivation of VOS word order with subject movement in a rightward specifier theory.

The difference between VSO and VOS word orders in a right-hand specifier theory is accomplished via a combination of controlling which specifiers are right-ward and controlling which argument(s) moves. VOS word can be derived from the base positions of a VP with a right-specifier (note that the majority of this literature assumes the VP-Internal hypothesis). From the base position, VOS can also be derived by moving the subject up to any right-specifier position (e.g. the specifier of IP).

VSO word order is derived from the same base order. The object then moves to a right-specifier position above the VP (the specific landing site will vary from language to language).

Movement of either the subject or object arguments was originally motivated by positing an EPP feature on the landing site. Modern analyses are more likely to argue that movement is motivated by a need to give the argument case or for purposes of information structure.

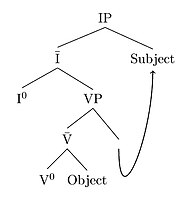

Subject-lowering[edit]

Another type of approach to derive verb-initial word orders involves subject lowering, resulting in a structure in which the subject follows the verb. Whereas proposals for V-raising and VP-raising generally assume that the linear order of a sentence is derived in syntax, the subject lowering account assumes that phonological well-formedness determines the linear word order.[1] Subject lowering has been proposed by Sabbagh (2013).[4] He treats subject lowering as a prosodic phenomenon.

Basic syntactic structure featuring subject lowering.

The basic idea is as follows. After the syntactic derivation is done, the subject is in SpecIP/SpecTP. On its way to phonological realization, the end result of the syntactic derivation can be manipulated in order to satisfy phonological and morphological requirements. In the case of subject lowering, the subject will move to V and right-adjoin to it, as illustrated by the tree below (taken from Clemens & Polinsky).[1]

Different languages are said to feature subject lowering, namely Berber (Choe 1987), Chamorro (Chung 1990, 1998), Tagalog (Sabbagh 2005, 2013).[1]

As Clemens & Polinsky (2015) explain, support for subject lowering comes from coordination facts.[1] When two sentences are coordinated, the subject must be able to have scope over the coordination, even though it shows up in a lower position in the clause.[1] To be able to have this scope, the subject needs to occupy a high position in the syntactic derivation.

Syntactic structure of transitive sentence in Tagalog

Subject lowering in syntactic structure of transitive sentence in Tagalog.

Prosodic structure of transitive sentence in Tagalog.

Subject lowering in prosodic structure of transitive sentence in Tagalog.

Sabbagh (2013) proposes a prosodic constraint to motivate subject lowering in Tagalog.[1][4] This constraint is called Weak Start and it says that «[a] prosodic constituent begins with a leftmost daughter, which is no higher on the prosodic hierarchy than the constituent that immediately follows.»[4] This proposal is situated in Match Theory (Selkirk 2011[11]). Match Theory states that clauses (CP and IP/TP) with illocutionary force correspond to intonational phrases (ɩ), XPs correspond to phonological phrases (φ), and X⁰s correspond to phonological words (ω).[1] Sabbagh (2013) proposes that the prosodic hierarchy is as follows:

Prosodic hierarchy: ɩ > φ > ω.[1]

The prosodic constraint Weak Start regulates the order in which different members of the hierarchy can appear in a single prosodic phrase.[1] The hierarchy states that elements that are relatively high on the prosodic hierarchy need to be preceded by elements that are equal or lower to them on the prosodic hierarchy (Sabbagh 2013).[4] In other words, phonological phrases (φ) need to be preceded by phonological words (ω).

This structure does not meet the requirement that Weak Start imposes on it (i.e. elements high on the prosodic hierarchy need to be preceded by elements that are equal or lower on the hierarchy). The subject, which is a phonological phrase (φ), precedes the verb, a phonological word (ω). This means that there is a mismatch between syntax and phonology.[4] In other words, for syntactic reasons, the subject must be high (because of scope over coordinations), but for phonology, the subject needs to follow the verb, instead of preceding it. Lowering the subject resolves this mismatch. The structure after subject lowering is illustrated in the structures below.

In these structures the verb (ω) precedes the hierarchically higher subject (φ). This structure obeys Weak Start. Thus, subject lowering is applied in order to satisfy this prosodic structure constraint.[4]

Syntactic structures involving subject lowering obey syntactic and phonological principles. The subject has moved to SpecIP/SpecTP, which gives it its necessary scope (as can be inferred from coordination structures). Lowering the subject in the prosodic structure causes the structure to obey the phonological constraint Weak Start as well.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Clemens, Lauren Eby; Polinsky, Maria (2015). «Verb-initial word orders (primarily in Austronesian and Mayan languages)» (PDF). The Blackwell Companion to Syntax.

- ^ Tomlin, Russell (1986). Basic Word Order: Functional Principles. London: Croom Helm.

- ^ Carnie, Andrew; Dooley, Sheila Ann; Harley, Heidi, eds. (2005). Verb first: On the Syntax of Verb Initial Languages. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sabbagh, Joseph (2013). «Word order and prosodic structure constraints in Tagalog». Syntax. 17: 40–89. doi:10.1111/synt.12012.

- ^ Wexler, Kenneth; Culicover, Peter (1980). Formal Principles of Language Acquisition. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262730662.

- ^ Aldridge, Edith (2002). «Nominalization and WH-movement in Seediq and Tagalog» (PDF). Language and Linguistics.

- ^ Sternefeld, Wolfgang (1995). «Voice phrases and their specifiers». Seminar für Sprachwissenschaft.

- ^ a b Cole, Peter; Hermon, Gabriella (2008). «VP raising in VOS language». Syntax. 11 (2): 144–197. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9612.2008.00106.x.

- ^ a b Coon, Jessica (2010). «VOS as predicate fronting in Chol Mayan». Lingua. 120 (2): 354–378. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2008.07.006.

- ^ Aissen, Judith (1992). «Topic and Focus in Mayan». Language. 68 (1): 43–80. doi:10.2307/416369. JSTOR 416369.

- ^ Selkirk, Elisabeth (2011). «The Syntax‐Phonology Interface». In Goldsmith, John; Riggle, Jason; Yu, Alan (eds.). The syntax-phonology interface. The Handbook of Phonological Theory. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 435–484. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.222.5571. doi:10.1002/9781444343069.ch14. ISBN 9781444343069.

While English is usually very strict about word order, when it comes to adverbs and the verb they modify, it can go either way. You can say «we worked tirelessly» or «we tirelessly worked». Both mean the same thing.

Without doing a statistical analysis, I think we usually put the adverb after the verb. «I worked tirelessly», «I ran quickly to the door», «I grabbed selfishly», etc.

Just to make it more complicated, if the verb has a direct object, you can put the adverb before the verb or after the direct object, but not between the verb and the direct object. Like you could say, «I suddenly found the solution», or you could also say, «I found the solution suddenly.» But a fluent speaker would NOT say, «I found suddenly the solution.»

As to when to put the adverb first and when to put it later, I can’t think of any general rule. If someone else on here can suggest a rule, I’m happy to hear it. I think it’s mostly about emphasis. If the adverb is important, you tend to put it after. Like if I said, «I worked tirelessly», that puts more emphasis on the claim that I was tireless, but if I said «I tirelessly worked», that puts more emphasis on the fact that I simply worked. But it’s often a very subtle difference.

When to put to before a verb. When used to after and with a verb in English

When should you put to in front of a verb in English? This question is more complicated than it seems at first glance. Many beginners to learn English make a lot of mistakes in using this particle. In order to always put it only in the right place, it is enough to learn a few simple rules.

Use cases for the to particle

It is important not to confuse to with a preposition. The to particle in English is always used with the initial verb, and the preposition is usually used with nouns. You can always ask the question «where?»

The to particle may not be used before every verb. Two simple rules prevent this. Firstly, the to particle should be placed only before (the initial form of the verb), and secondly, in this case, the to particle may not be placed before every infinitive, since there is also a «bare infinitive» or bare infinitive. We have prepared for you a list of the main cases when the to particle is needed before the verb:

- With the help of a verb with an infinitive, a certain purpose is expressed.

- The adverbs too or enough precede the infinitive.

- The infinitive is paired with would, would prefer, or would love.

- The sentence contains the word only, which expresses dissatisfaction with a certain event or result.

- After something, anyone, somewhere and nothing.

- The sentence contains a combination of be the first (the second, etc.), be the next, be the last, or be the best.

She turned around to ask him some questions She turned to ask him a few questions.

My aunt is too obstinate to apologize “My aunt is too stubborn to apologize.

I would visit London — I would like to visit London.

She went to a beach house only to meet her annoying relatives “She went to the beach house just to meet her boring relatives.

I have nothing to tell you — I have nothing to tell you.

She is the next to choose where to go on the weekend “She’s next deciding where to go for the weekend.

Free lesson on the topic:

Irregular verbs of the English language: table, rules and examples

Discuss this topic with your personal tutor in a free online lesson at Skyeng School

Leave your contact details and we will contact you to register for the lesson

The to particle is required after some verbs, including: want, need, learn, afford, agree, decide, expect, help, forget, hope, offer, pretend, try, want, seem, plan, promise, remember, would.

I want to give you advice — I want to give you advice.

I agree to take him to the pool — I agree to take him to the pool.

He forgot to replace his furniture — He forgot to replace his furniture.

I would inform you about our meeting — I would like to inform you about our meeting.

To particle with modal verbs

After, i.e. verbs expressing intention and possibility (may, should, can, must, shall, would, will, etc.), the same «bare infinitive» or bare infinitive will be used.

I can swim faster — I can swim faster.

She should tell you the truth “She must tell you the truth.

He may ask you about it — He can ask you about it.

We shall give him some food — We have to give him some food.

I will call you — I’ll call you.

In English, there are several modal verbs that should always be used with the to particle, among them are verbs dare, have, ought и be.

I have to drive carefully — I have to drive carefully.

He ought to call her — He should call her.

How dare she tell me what to ask? — How dare she tell me what to ask?

I have to ask you about it — I have to ask you about it.

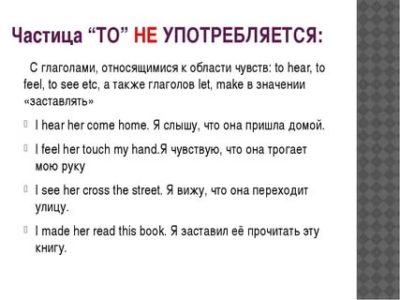

When the to particle is not used

In English, there are a number of cases in which the to particle is not required before the verb. There are not so many of these cases, so they are very easy to remember. The to particle will not be used:

- After the verbs make, let, see, feel and hear (except for the passive voice).

- After the expressions would rather and had better.

- In questions starting with Why not?

- When in one sentence there are two indefinite verbs, and between them there is and or or, the particle to is not placed before the second verb.

- When the verb make is in the meaning of «force».

Let me know where are you — Let me know where you are.

You’d better stay strong “You better stay strong.

.Why not go to the theater? — Why not go to the theater?

I want to eat and drink — I am hungry and thirsty.

She makes me care about him — She makes me take care of him.

about the to particle in English:

The infinitive is usually used with the to particle, which is its grammatical attribute. However, the particle to is sometimes omitted, and the infinitive is used without it:

1. After auxiliary and modal verbs: can, could, must, may, might, will, shall, would, should (and their negative forms cannot = can’t, must not = mustn’t, etc.).

Source: https://mmostar.ru/vazhnaya-informaciya-pro-gepatit/kogda-nuzhno-stavit-to-pered-glagolom-kogda-upotreblyaetsya-to-posle-i-s-glagolom-v/

ᐉ Using to after and with a verb in English

Hi there! It’s time to get acquainted with the very important preposition «to» for the English language and to study the use of to after and with the verb in English. Often, students at the beginning of their studies experience difficulties precisely because of its use. Having learned one use case, it is difficult to switch to another option, which also requires this preposition. In fact, everything is not so difficult and sad with the nasty «to». Let’s consider those situations where it is needed and where it should not be.

Using «to» with an infinitive

Using «to» with an infinitive

Infinitive — this is an impersonal form of the verb that answers the question «What to do?», «What to do?» To my students who are just starting their studies, I always give a very simple hint — ask a question for action, if the option of infinitive questions (see above) is appropriate, then dare to leave the «to» part.

For example, a student translates a sentence I want to read a book on the train, he comes to the first verb want (want) and asks the question «what am I doing?»

Then we move on to read (read), ask the question «what to do?» I want to read a book on the train.

Here are some examples of infinitives in English, you can check them by asking the right questions:

I am glad to see you here!

(Glad to see you here!)

My grandmother s to write letters and hates messengers.

(My grandmother loves to write letters and hates instant messengers.)

We hope to meet you at the party on Friday.

(We hope to meet you at the party on Friday.)

They will try to come but they may be busy.

(They will try to come, but they may be busy.)

She asked her child to take the basket.

(She asked her child to take the basket.)

Use of the preposition «to» with the Dative Case / Noun with the preposition «to»

Use of the preposition «to» with the Dative Case / Noun with the preposition «to»

The use of a noun with the preposition «to» corresponds to the dative case in the Russian language (answers the question «to whom?», «What?»). But it is worthwhile to understand the use cases, since there are two possible options, one of which does not require a preposition in front of the object.

Case # 1 Direct object

The preposition «to» is used with direct object in English.

For those who are not super deeply friends with the grammar of the Russian language, I will explain a little easier — if you want to say: I write (what?) A message (to whom?) To you, then in the English version “to” must be placed before the one at whom the action is directed, that is, we immediately say “what”, and then before “whom” we put the preposition: Iamwritingamessagetoyou.

More examples:

He brought a huge bunch of roses to her.

(He brought her a huge bouquet of roses.)

They presented the best gift to their mother.

(They gave the best present to their mom.)

You can order three pizzas to children, they are always hungry.

(You can order three pizzas for the kids, they are always hungry.)

Source: https://english-skype.net/grammatika/upotreblenie-to-posle-i-s-glagolom-v-anglijskom-jazyke/

The use of the infinitive in English

Have you ever seen the to particle with verbs after it? Have you ever thought about its purpose? Well, it’s time to explain something about one of the most important topics in the English language.

When a verb is placed after the to particle and the whole thing is placed in a sentence, the name for all this is an infinitive. The thing is important and necessary. I propose to figure out why and for what.

INFINITIVE AS A FORM OF THE QUESTION «FOR WHAT», «WHY»

We use the infinitive to express intent (the question «why», «why»). Roughly speaking, in this case, we can say that the infinitive corresponds to the Russian word «to».

The prisoner locked the door to keep the policeman out. The inmate closed the door to prevent the police from entering the cell

Husband bought his wife two plastic flowers to express the most important. The husband bought two plastic flowers for his wife to tell the main thing.

The infinitive follows certain verbs

We use the infinitive after certain verbs, in particular after verbs expressing thoughts and feelings (choose, decide, expect, forget, hope, learn, plan, remember, want, would) and after verbs related to speech (agree, promise, refuse )

Entrepreneurs decided to go bankrupt mutually. The entrepreneurs decided to break up the business together.

Remember to sleep while smoking on train… Remember to spit when you smoke on the train. (Inscription in China)

It should be added that after some verbs (advice, ask, invite, tell, warn, expect, would) the direct addition follows, and then the infinitive:

Travel agent adviced me to visit brand-new country — ISIS. A travel agent advised me to visit a completely new country — ISIS.

Infinitive after adjectives

The infinitive is placed after certain adjectives to express the reason for that adjective (happy, glad, sad, pleased, surprised, proud)

Osama Bin Laden was happy to get an announcement of war on terrorism as birthday present. Osama bin Laden was delighted to receive a declaration of war on terrorism as a gift.

Leonardo Di Caprio is proud to be named in honor of ninja turtle. Leonardo DiCaprio is proud to be named after the Ninja Turtle.

Infinitive as «post-attribute»

Source: http://londonnsk.ru/grammatika/103-ispolzovanie-infinitiva-v-anglijskom-yazyke

Questions with a preposition at the end in English

In traditional grammatical rules, it is believed that prepositions in questions should not be put at the end of a phrase or a sentence. And this is really correct from the point of view of English grammar. However, in informal speech, the preposition is often put separately from the word with which it is associated. In this case, such an order of words is not considered an error.

Compare:

In which restaurants are we having lunch? (formally)

Which restaurants are we having lunch in? (informally)

For whom is Jack waiting for? (formally)

Who is Jack waiting for? (informally)

A preposition is a part of speech that indicates spatial, causal, temporal and other types of relationships between words in a sentence. Thus, prepositions in English have the same function as cases in Russian.

Prepositions can be used at the end of a sentence in the following cases:

IN INFORMAL SPEECH OR DURING COMMUNICATION IN QUESTIONAL PROPOSALS,

BEGINNING WITH WHAT, WHO, WHERE, WHİCH.

It is not only possible, but even necessary to end sentences with an excuse in informal communication. Such designs give speech a more natural and casual tone.

For example:

Who should I give this book to? — Who do I need to give this book to?

What apartment did you stayat / in? — What apartment are you staying in?

Which of the suburbs do you live in? — In which district do you live?

What was tom thinking about? — What was Tom just thinking?

Which city does Alice live in? — Where does Alice live?

what are you looking at? — What are you looking at?

Who is jack waiting for? — Who is Jack waiting for?

What conference room did Sam eat into? — Which meeting room Sam went into.

IN DIFFICULT SUBORDINATED PROPOSALS AND IN PREV.

You can use a preposition not only in interrogative sentences, but also in affirmative complex sentences with a definitive clause.

For example:

Jason told me what he was looking for. — Jason told me what he was looking for.

Ask Jack about it. Only he knows which home Jessica lives in. — Ask Jack about it. Only he knows which house Jessica lives in.

I don’t understand what you are askingfor. “I don’t understand what you are asking.

Daniel was always curious what Jack was dreaming about. — Daniel always wondered what Jack was dreaming of.

IN OFFERS WITH A PASSIVE BEDDING.

You can also put a preposition at the end of a sentence if it is part of a passive construct.

For example:

Jessica was the only one they laughedat — Jessica was the only one they laughed at.

IN PROPOSALS WHEN THE PROPOSAL IS AN INDIVIDUAL PART OF THE INFINITIVE.

For example:

This situation is not difficult to put up with. — This situation is easy to put up with.

Jack just wants to come by. “Jack just wants to come over to visit.

What information should you know to sign in? — What information do you need to register.

Olga asked him to stay in. — Olga asked him to stay.

Kate doesn’t know what to begin with? — Kate doesn’t know where to start.

Olga finally decided to break up with Ivan… — Olga finally decided to part with Ivan.

It seems that I forgot to log out. — Looks like I forgot to sign out of my account.

This is the article that I want to how toone. — This is the very article that I want to comment on.

It is better to avoid constructions with a preposition at the end in the following cases:

FOR FORMAL COMMUNICATION OR CORRESPONDENCE.

As you can see from the rules listed above, a preposition at the end of a sentence is not a grammatical error. However, this is appropriate when dealing exclusively with friends. But if you are writing a scientific paper, a business plan, or sending a letter to a foreign colleague, try to avoid such constructions.

For example:

False: Which edition was your work publishedin? — In which edition was your work published?

Right: In which edition of your work was published? — In which edition was your work published?

Source: https://www.wallstreetenglish.ru/blog/voprosy-s-predlogom-na-kontse-v-angliyskom-yazyke/

When used to after and with a verb in English

An extremely important preposition in English. When should you use it and when not? I’ll tell you in this article.

Hello guys! Today I would like to tell you about a very important preposition of the English language. About the preposition «to». Many people find it very difficult at the beginning of the study. Yes, and I remember myself. I constantly asked the tutor to tell me about the rules for its use. He was very often confused, used it when necessary and when not. So let’s see when we should use it and when we shouldn’t.

Using the preposition «to» with the Dative Case

Indeed, in the article «Prepositions in English» I have already partially voiced the rules for using «to». And I said that it serves to convey the meaning of the Dative Case.

But, it all depends on where we put the add-on. It can be both direct and indirect. With the direct addition, we must use the preposition «to». Let’s better use examples:

I’ll send a letter to you tomorrow.

(I’ll send you a letter tomorrow)

In this case, a letter is a direct object, i.e. it comes immediately after the verb. Another example:

Give this book to me please.

(Please give me this book)

I wrote a message to him last night, but he didn’t respond.

(I wrote him a letter last night but he didn’t answer)

If the object is indirect, then the preposition «to» is omitted. For example, we could say this:

I’ll send you a letter tomorrow.

Give me this book please.

I wrote him a message last night, but he didn’t respond.

The meanings of the sentences are absolutely the same, but the preposition «to» is no longer used. This is a very important point, and it often causes difficulties and confusion when communicating with people. Just try to remember the following common constructs:

to send smb smth / to say smth to smb

(send something to someone / send something to someone)

to give smb smth / to give smth to smb

to write smb / to write smth to smb

This rule does not apply to the verb «to explain to explain». With this word, the preposition «to» is used regardless of the type of object.

Could you explain this rule to me?

Could you explain this rule to me?

(Could you explain this rule to me?)

The same situation is with the verb «to listen to listen». Also, without «to» is not used:

Listen to me please.

(Listen to me please)

Listening to music at work is not good.

(Listening to music at work is not good)

Listen to him and say what you think.

(Listen to him and tell him what you think)

I don’t want to listen to you.

(I don’t want to listen to you)

Please note that in the case of using these words one by one, i.e. without additions, the preposition «to» can be omitted.

Please listen! I don’t want you to take offence at me.

(Please listen! I don’t want you to take offense at me)

Why have you done it? Please explain!

(Why did you do this? Please explain!)

In addition to the verbs «to listen» and «to explain», there are a number of words that are used with the preposition «to»:

| Used with “to” | Transfer |

| Boast to somebody | brag to someone |

| Complain to somebody | complain to anyone |

| Confess to somebody | confess to someone |

| Confide to somebody | trust someone |

| Convey to somebody | transfer to someone |

| Explain to somebody | explain to someone |

| Listen to somebody | listen to anyone |

| Reply to somebody | answer someone |

| related to it somebody | relate to someone / something |

| Repeat to somebody | repeat to someone |

| Report to somebody | report to anyone |

| Say to somebody | tell anyone |

| State to somebody | present to anyone |

| Suggest to somebody | suggest to someone |

Also, moments where the use of to after verbs is not allowed:

| Used without “to” | Transfer |

| advise somebody | advise anyone |

| Answer somebody | answer someone |

| Ask somebody | ask anyone |

| hear somebody | hear anyone |

| Instruction somebody | instruct someone |

| Call somebody | call someone |

| Tell somebody | tell anyone |

| Warning somebody | warn anyone |

Using «to» with an infinitive

The preposition «to» is always used with the infinitive of a verb. For example:

I to read.

(I like to read)

I don’t want to eat it.

(I don’t want to eat this)

I’d to tell you about it.

(I would like to tell you about this)

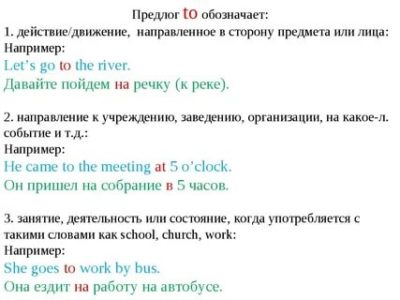

The use of «to» to indicate the direction of travel.

If we are talking about the direction of movement, then we should also use the preposition «to».

I’m going to University.

(I’m going to the university)

He goes to school.

(He goes to school)

Let’s go to the cinema.

(Let’s go to the movies)

I’ll come to you tomorrow.

(I will come to you tomorrow)

I moved to Moscow last year.

(I moved to Moscow last year)

HO!

Source: https://enjoyenglish-blog.com/razgovornyj-anglijskij/upotreblenie-to-v-anglijskom.html

Verbs to be and to do in English: features of use

One of the most popular language confusion is the use of verbs to be и to do… This refers to the substitution of one verb for another, which occurs as a result of a misunderstanding of the functions and meanings of these words.

We have already covered the verb to be in detail, so now we will focus on comparing the use of verbs in situations in which confusion occurs most often.

Strong and weak verb

There are two broad categories of verbs in English — strong and weak.

Strong verbs include modal verbs and their equivalents, have got, auxiliary verbs (do / does / did) and to be… Strong verbs independently form negative constructs and questions:

Must he go to the dentist? — I must go to the dentist./I mustn’t eat apples.

In the case of weak verbs, we are not able to construct a question or negation without auxiliary ones, avoiding an error:

I live to Paris.

Live you in Paris? — error/

It is correct to say: Do you live in Paris?

He livesNote inParis. — error/

It is correct to say: He doesn’t live inParis.

So, we use the auxiliary do or two of its other forms (does / did) in order to correctly form questions and denials.

A mistake is born when students (by this word we mean all foreign language learners, young and old) begin to use auxiliary verbs for the forms to be:

He is Liza’s brother.

Does he is Liza’s brother? — error

He doesn’t is Liza’s brother. — error

Undoubtedly verb forms to be do not look like their original shape. We believe this is what can be confusing.

Remember: am, is, are, was, were are strong verbs and never use auxiliary do:

Is he Liza’s brother? — right

He is not Liza’s brither. — right

Rђ RІRѕS, do against. By itself how semantic this verb is weak and has a meaning делать… Accordingly, he needs the help of an auxiliary one that matches him in spelling and pronunciation doWhich is not translated into Russian and performs a purely grammatical function:

I do exercise every day.

Do I do exercise every day? — right

I don’t do exercise every day. — right

Do I exercise every day? — error

I do not exercise every day. — error / This sentence is meaningless and will be translated “I don’t exercise every day”. I would like to immediately ask “do not that? exercises»

Auxiliary

The second serious problem sometimes becomes choice of auxiliary verb.

Most of the courses are structured in such a way that acquaintance with English grammar and the language in general begins with the verb to be — to be, to be, to be somewhere.

Students are so used to designs with to bethat for them it becomes completely logical to use them as an auxiliary verb… It actually loses its meaning and sentences of this kind become grammatically equal:

She is inParis.

She lives inParis.

Let’s say that contextually it is possible to translate both of them as “She lives in Paris”. The following happens:

Is she in Paris? — right

Is she live in Paris? — ERROR

To benever will not be used as an auxiliary verb

Source: http://begin-english.ru/article/glagoly-to-be-i-to-do-v-angliyskom-yazyke-osobennosti-ispolzovaniya/

Such have to. Modal verb Have To in English

Modal verb have to (sometimes called a modal construction) is used to express a duty or need (in an affirmative or interrogative form) or a lack of duty and necessity (in a negative form). Also the verb have to can express confidence, certainty, probability.

have it is synonymous with modal verb must, and has a tinge of compulsion due to some circumstances.

For example:

This answer has to be correct.

This answer, should be, correct. (Expresses confidence, certainty.)

They Had to leave early.

Them had leave early. (Expresses obligation, compulsion due to circumstances.)

The soup has to be stirred continuously to prevent burning.

Soup from time to time necessary stir so that it does not burn. (Expresses the need.)

Use of the modal verb have to in the present, past and future tenses

In most cases, the use of modal verbs in the past and future tense differs from other verbs. The table below shows use of a modal verb have to in different situations.

Remember:

Design do not have to means no need, but not a prohibition, while the construction must not means a categorical prohibition.

Your application is accepted

Our manager will contact you soon

Close

An error occurred while sending

Send again

The verb system of the English language is significantly different from the Russian one. You can often hear: “English is so complicated! And modal verbs are something from the realm of fantasy. » In fact, there is nothing complicated about them: you need to take a closer look at them.

In this article we will deal with one such verb — “have to”.

Tense forms of the verb have to

The modal verb have to can be used in the present, past and future tenses. The table shows in detail the formation of different forms of the verb.

Present simple

Source: https://499c.ru/takoe-have-to-modalnyi-glagol-have-to-v-angliiskom-yazyke/

Using the to particle after modal verbs

I am glad to welcome you, friends! When you remember all the rules you have learned at school in English lessons, what you have heard dozens of times becomes clear in your memory:

«After modal verbs, the -to particle is not used, except for the following exceptions.»

After the word “exclusion,” the thread of memory is interrupted. I believe that a similar situation is observed among many school leavers, and in general, it will be useful for beginners to learn about this rule. Let’s put things right by putting in place the words that are exceptions and those that aren’t.

The to particle after the modal verb

The general rule is that a modal verb is always followed by an infinitive verb

It is well known that the grammatical feature of a verb in the infinitive is nothing more than the particle –to. A continuation of the above rule is a very important point that the verb is placed in the infinitive, but without the -to particle, indicating the infinitive.

Modal verbs that combine with the to particle

As mentioned, there are a few modal verbs that are exceptions when used in conjunction with –to.

| Used from -to parts | ||

| Verb | Example | Transfer |

| Right to | You ought to say this thing to him. | You need to tell him that. |

| Have (got) to | You have to go with him, if you are free. He has got to be at work by 7:45 am. | You should go with him if you’re free. He should be at work at 7:45 AM. |

| Be to | The bus is to leave in 8 minutes.When are we to return? | The bus leaves in 8 minutes, when do we need to get back? |

Using to with the verbs need and dare

In addition to the first and second groups of verbs, there are several modal verbs in English, which in some cases require the use of the -to particle after themselves, in some its use ceases to be necessary, these include:

-Need has not only one shape, but two — sufficient (or correct) and insufficient.

Insufficient form is used most often when specifying a one-time action. Observed only in negative and interrogative types of sentences in the present tense and used without -to to indicate the need for action

- Need we go now? — Do we really need to go now?

But the sufficient form –need is used to indicate repetitive actions in the meaning of «need», «required». Has the form of present and past tenses and can be used in all three types of sentences.

- Do you need to help them every day? — Do you need to help them every day?

- Do we need to go there every Sunday? — Should we go there every Sunday?

-Dare is a semi-modal verb due to the fact that it stands on the border between full-valued and modal

The modal –dare means “to have arrogance / courage”, has the forms of the present and the past, after which the infinitive is not used.

- How dare she tell him this thing? — How dare she say that to him?

The full-valued –dare has all the properties and characteristics of an ordinary verb, which is why it is followed by a verb in the infinitive with –to after it, as after an ordinary one.

- John dares to lie to him. — John dares to lie to him.

- He did not dare to lay a hand on her. “He dared not touch her.

Features of the modal verb used to

Another verb that should be mentioned in this article is -used to, always used with -to. Until now, its belonging to the category of modal words remains controversial, some linguists attribute it to the usual — full-valued. However, I am inclined to believe that its essence is closer to modal.

Its main difference from other modal words is that it has only one temporary form — the past.

- John used to be so serious when we knew him. “John was so serious when we knew him.

The auxiliary verb -do can be used to form negations and questions with -used to.

- I did not use to think of computer as a common thing when I was your age. “I didn’t treat the computer as a completely ordinary thing when I was your age.

- Did she use to visit them? — Did she visit them?

It is possible to construct these types of sentences without -do, which is another feature of this word.

- I used not to worry about my clothes when I was 10 years old. — I didn’t pay attention to my clothes when I was 10.

- Used you to play the piano? — Did you play the piano?

Hopefully you’ve figured out how to use –to after English modal verbs.

Good Luck!

Modal verbs in English

Source: https://englishfull.ru/grammatika/to-posle-modalnih-glagolov.html

Wiki User

∙ 13y ago

Best Answer

Copy

No. Before is not a verb.

It is usually used as an adjective or an adverb.

Wiki User

∙ 13y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: Is the word before a verb?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

Normally, sentences in the English language take a simple form. However, there are times it would be a little complex. In these cases, the basic rules for how words appear in a sentence can help you.

Word order typically refers to the way the words in a sentence are arranged. In the English language, the order of words is important if you wish to accurately and effectively communicate your thoughts and ideas.

Although there are some exceptions to these rules, this article aims to outline some basic sentence structures that can be used as templates. Also, the article provides the rules for the ordering of adverbs and adjectives in English sentences.

Basic Sentence Structure and word order rules in English

For English sentences, the simple rule of thumb is that the subject should always come before the verb followed by the object. This rule is usually referred to as the SVO word order, and then most sentences must conform to this. However, it is essential to know that this rule only applies to sentences that have a subject, verb, and object.

For example

Subject + Verb + Object

He loves food

She killed the rat

Sentences are usually made of at least one clause. A clause is a string of words with a subject(noun) and a predicate (verb). A sentence with just one clause is referred to as a simple sentence, while those with more than one clause are referred to as compound sentences, complex sentences, or compound-complex sentences.

The following is an explanation and example of the most commonly used clause patterns in the English language.

Inversion

Inversion

The English word order is inverted in questions. The subject changes its place in a question. Also, English questions usually begin with a verb or a helping verb if the verb is complex.

For example

Verb + Subject + object

Can you finish the assignment?

Did you go to work?

Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive Verbs

Some sentences use verbs that require no object or nothing else to follow them. These verbs are generally referred to as intransitive verbs. With intransitive verbs, you can form the most basic sentences since all that is required is a subject (made of one noun) and a predicate (made of one verb).

For example

Subject + verb

John eats

Christine fights

Linking Verbs

Linking Verbs

Linking verbs are verbs that connect a subject to the quality of the subject. Sentences that use linking verbs usually contain a subject, the linking verb and a subject complement or predicate adjective in this order.

For example

Subject + verb + Subject complement/Predicate adjective

The dress was beautiful

Her voice was amazing

Transitive Verbs

Transitive Verbs

Transitive verbs are verbs that tell what the subject did to something else. Sentences that use transitive verbs usually contain a subject, the transitive verb, and a direct object, usually in this order.

For example

Subject + Verb + Direct object

The father slapped his son

The teacher questioned his students

Indirect Objects

Indirect Objects

Sentences with transitive verbs can have a mixture of direct and indirect objects. Indirect objects are usually the receiver of the action or the audience of the direct object.

For example

Subject + Verb + IndirectObject + DirectObject

He gave the man a good job.

The singer gave the crowd a spectacular concert.

The order of direct and indirect objects can also be reversed. However, for the reversal of the order, there needs to be the inclusion of the preposition “to” before the indirect object. The addition of the preposition transforms the indirect object into what is called a prepositional phrase.

For example

Subject + Verb + DirectObject + Preposition + IndirectObject

He gave a lot of money to the man

The singer gave a spectacular concert to the crowd.

Adverbials

Adverbials

Adverbs are phrases or words that modify or qualify a verb, adjective, or other adverbs. They typically provide information on the when, where, how, and why of an action. Adverbs are usually very difficult to place as they can be in different positions in a sentence. Changing the placement of an adverb in a sentence can change the meaning or emphasis of that sentence.

Therefore, adverbials should be placed as close as possible to the things they modify, generally before the verbs.

For example

He hastily went to work.

He hurriedly ate his food.

However, if the verb is transitive, then the adverb should come after the transitive verb.

For example

John sat uncomfortably in the examination exam.

She spoke quietly in the class

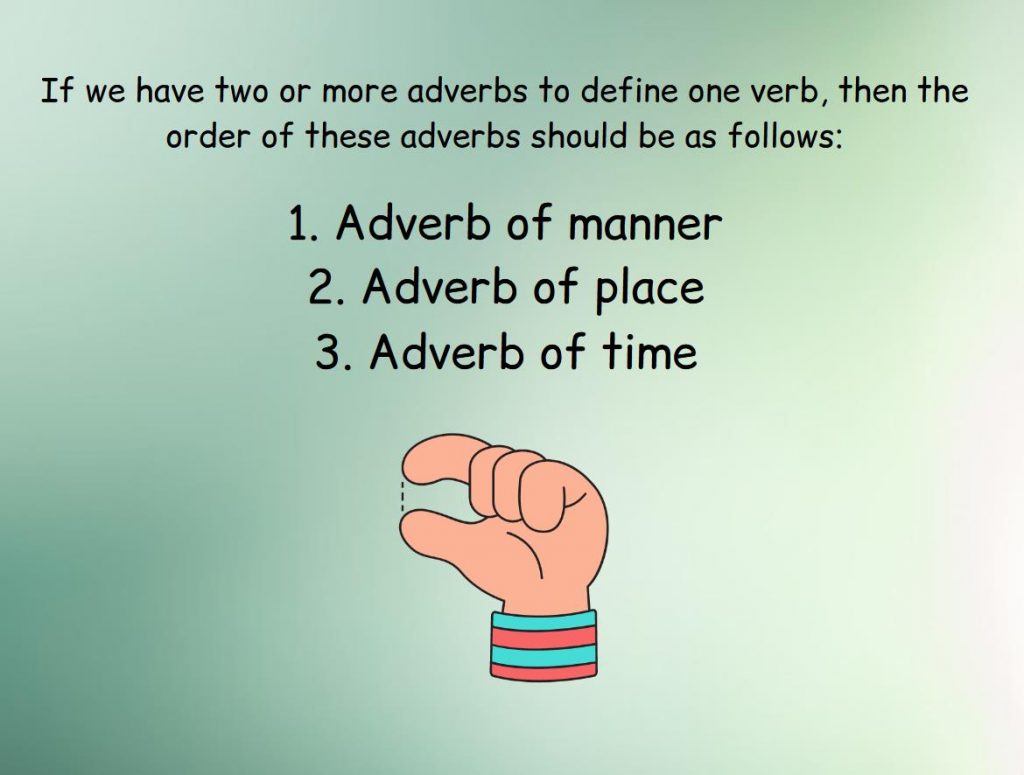

The adverb of place is usually placed before the adverb of time

For example

John goes to work every morning

They arrived at school very late

The adverb of time can also be placed at the beginning of a sentence

For example

On Sunday he is traveling home

Every evening James jogs around the block

When there is more than one verb in the sentence, the adverb should be placed after the first verb.

For example

Peter will never forget his first dog

She has always loved eating rice.

Adjectives

Adjectives

Adjectives commonly refer to words that are used to describe someone or something. Adjectives can appear almost anywhere in the sentence.

Adjectives can sometimes appear after the verb to be

For example

He is fat

She is big

Adjectives can also appear before a noun.

For example

A big house

A fat boy

However, some sentences can contain more than one adjective to describe something or someone. These adjectives have an order in which they can appear before a now. The order is

Opinion – size – physical quality – shape – condition – age – color – pattern – origin – material – type – purpose

If more than one adjective is expected to come before a noun in a sentence, then it should follow this order. This order feels intuitive for native English speakers. However, it can be a little difficult to unpack for non-native English speakers.

For example

The ugly old woman is back

The dirty red car parked outside your house

When more than one adjective comes after a verb, it is usually connected by and

For example

The room is dark and cold

Having said that, Susan is tall and big

Get an expert to perfect your paper

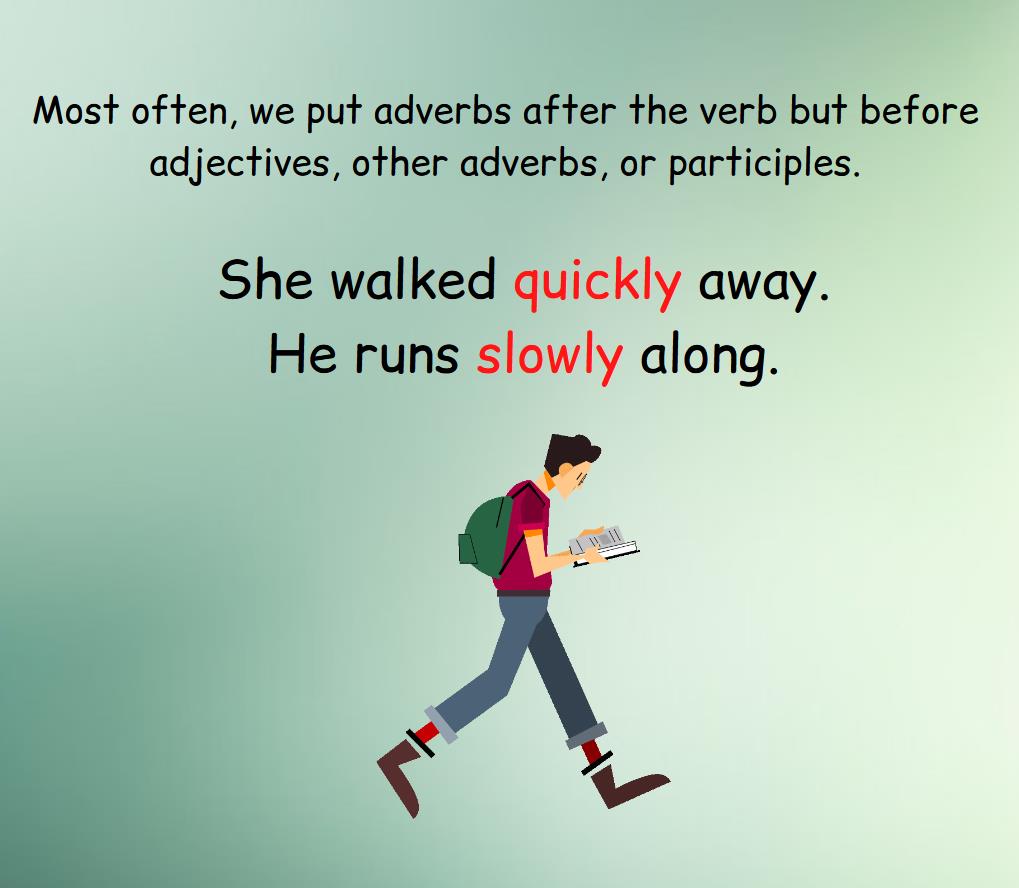

Adverbs can take different positions in a sentence. It depends on the type of sentence and on what role the adverb plays and what words the adverb defines, characterizes, describes.

Most often, we put adverbs after the verb but before adjectives, other adverbs, or participles.

She walked quickly away.

He runs slowly along.

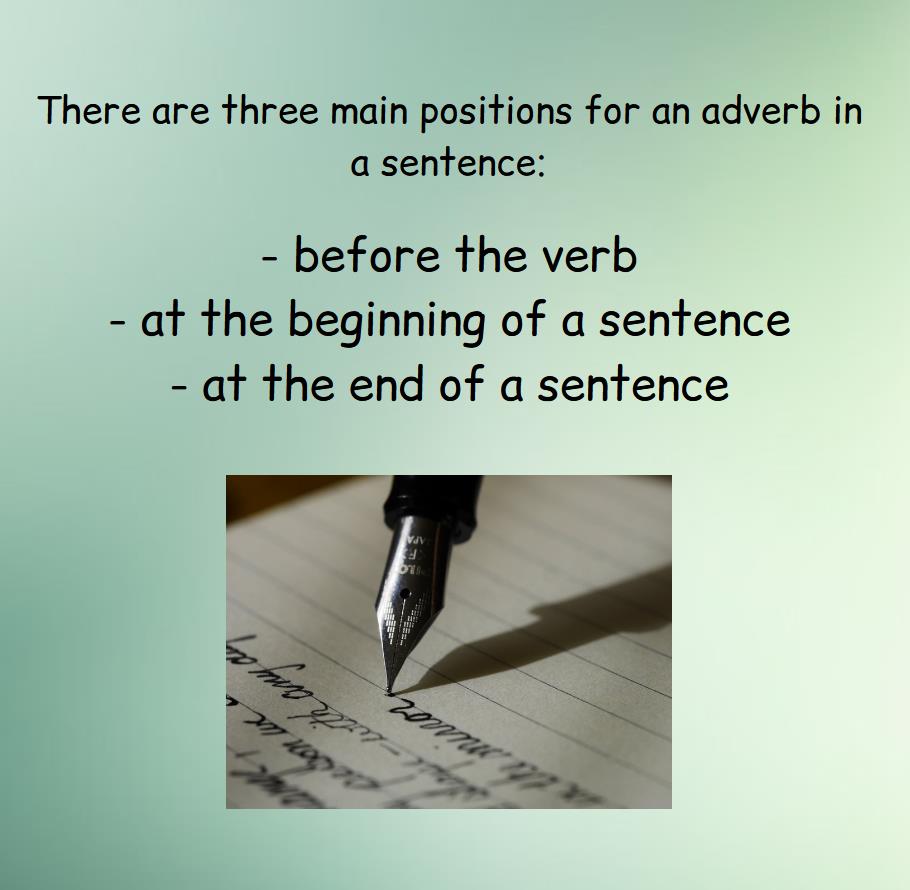

Adverb and three main positions

There are three main positions for an adverb in a sentence:

- before the verb

- at the beginning of a sentence

- at the end of a sentence

Let’s look at these positions separately.

At the end

We put an Adverb at the end of a sentence after the predicate and the object.

The water is rising fast.

At the beginning

We put an adverb at the beginning of a sentence before the subject.

Today I have a piano lesson.

In the middle

Most often, we put an adverb in the middle of a sentence. But “middle” is not an accurate concept. Where exactly this middle is located, it depends on the words next to which we use the adverb.

- In interrogative sentences, we put an adverb between the subject and the main verb.

Did he often go out like that?

- If the predicate in the sentence is only one verb, then we put the adverb before the verb.

You rarely agree with me.

- If the predicate contains more than one word, then we put the adverb after the modal verb or after the auxiliary verb (if there is a modal verb or auxiliary verb).

You must never do this again.

There are adverbs that we can put before a modal verb or an auxiliary verb.

He surely can prepare for this.

Adverb placement depending on the type of adverb

The place of an adverb depends on what type of adverbs it belongs to. Different adverbs can appear in different places.

Adverbs of manner

We usually use Adverbs of manner:

- before main verbs

- after auxiliary verbs

- at the end of the sentence

- If the verb is in the Passive Voice, then we use an adverb between the auxiliary verb and the verb in the third form.

- We usually use Adverbs of manner after the verb or after the Object.

- We can NOT use an Adverb of manner between the verb and direct object. If the sentence has a verb and a direct object, then we use an adverb of manner before the verb or after the object.

- Usually we put an adverb of manner that answers the question HOW after the verb or after the verb and the object.

She held the baby gently.

We are running slowly.

- We usually put the adverbs well, fast, quickly, immediately, slowly at the end of a sentence.

I wrote him an answer immediately.

The truck picked up speed slowly.

Adverbs of Frequency

Adverbs of frequency are adverbs that indicate how often, with what frequency an action occurs.

Adverbs of frequency answer the question “How often?“

- Most often we put Adverbs of frequency before the main verb.

- We can use normally, occasionally, sometimes, usually at the beginning of a sentence or at the end of a sentence.

- We usually put Adverbs of frequency that accurately describe the time (weekly, every day, every Saturday) at the end of a sentence.

We have another board meeting on Monday.

I wish we could have fried chicken every week.

Maybe we could do this every month.

- We put Adverbs of frequency after the verb to be if the sentence contains the verb to be in the form of Present Simple or Past Simple.

My routine is always the same.

- We often use usually, never, always, often, sometimes, ever, rarely in the middle of a sentence.

I often wish I knew more about gardening.

- We can use usually at the beginning of a sentence.

Usually, I keep it to myself.

Adverbs of degree

Adverbs of degree express the degree to which something is happening. These are such adverbs as:

- almost

- absolutely

- completely

- very

- quite

- extremely

- rather

- just

- totally

- We put Adverbs of degree in the middle of a sentence.

- We put Adverbs of degree after Auxiliary Verbs.

- We put Adverbs of degree after modal verbs.

I feel really guilty about that.

- We put Adverbs of degree before adjectives.

When guns speak it is too late to argue.

- We put Adverbs of degree before other adverbs.

He loses his temper very easily.

- Sometimes we put Adverbs of degree before modal verbs and before auxiliary verbs. Usually, we use such adverbs as:

- certainly

- definitely

- really

- surely

You definitely could have handled things better.

I think I really could have won.

- The adverb enough is an exception to this rule. We put the Adverb enough after the word it characterizes.

I have lived long enough.

Adverbs of place and time

Let’s see where we use the adverbs of place and adverbs of time.

- Most often we put the adverb of place and time at the end of the sentence.

I thought you didn’t have family nearby.

They found her place in Miami yesterday.

- We put monosyllabic adverbs of time (for example, such as now, then, soon) before main verbs but after auxiliary verbs including the verb to be.

Now imagine you see another woman.

Yes, he is now a respectable man.

- We can use adverbs of place and time at the very beginning of a sentence when we want to make the sentence more emotional.

Today, we have to correct his mistakes.

- We put the adverbs here and there at the end of the sentence.

Independent thought is not valued there.

- Most often we put adverbs of place and time after the verb or verb + object.

I can’t change what happened yesterday.

You have to attend my wedding next month.

- Most often we put such adverbs as towards, outside, backward, everywhere, nearby, downstairs, southward, at the end of the sentence or in the middle of the sentence, but immediately after the verb.

I made iced tea and left it downstairs.

With this speaker, you can hear everything outside.

I can run backward!

- We put adverbs of time that accurately define the time (for example, yesterday, now, tomorrow) at the end of the sentence.

The ship is going to be back tomorrow.

He wants it to happen now.

If we want to emphasize time, we can put an adverb that accurately specifies the time at the beginning of the sentence.

Tomorrow I’m moving to Palais Royal.

Adverbs that show the speaker’s degree of confidence.

Let’s talk about the place in the sentence occupied by Adverbs that show the speaker’s degree of confidence in what the speaker is saying.

- We can put at the beginning of the sentence such adverbs as:

- definitely

- perhaps

- probably

- certainly

- clearly

- maybe

- obviously

Certainly, you have an opinion about that.

Definitely think twice before correcting one of your mistakes again.

Maybe someone else was in her apartment that night.

We can also put adverbs like this in the middle of a sentence:

They’ll probably name a street after me.

This assumption is clearly no longer valid.

Adverbs that emphasize the meaning of the word they describe

The next group of adverbs is adverbs that emphasize the meaning of the word they describe.

- Look at the following adverbs:

- very

- really