The

theory of phrase or word combination in linguistics has a long

tradition going back to the 18-th century. According to Russian

scholars the term ‘word combination’ (словосочетание)

can be applied only to such groups of words which contain at least

two notional words forming a grammatical unit. Thus Soviet linguists

restrict the use of the term ‘word combination’ to combination of

notional words. Western scholars hold a different view of the

problem. They consider that every combination of two or more words

constitutes a unit which they term ‘phrase’. In other words,

western linguists do not limit the term ‘phrase’ to combination

of notional words and do not draw a sharp distinction between the two

types of word-groups such as ‘wise men’ and ‘to the

lighthouse’. The first and the most important difference of opinion

on the question between soviet and western scholarsconcerns the

constituents of the word groups forming grammatical units.

Another

debatable problem in soviet linguistics was whether a predicative

combination of words forms a word combination.

It

is generally known that a sentence is based on predication and its

purpose in communication. A word combination has no such aim. Word

combinations are more like words because they are employed for naming

things, actions, qualities and so on. In contrast with soviet

linguists some western scholars make no difference between subject –

predicate combinations of words and other word combinations, though

some western theories bear considerable resemblance to Russian ideas.

There’s

no traditional terminology in the works of English and American

scholars discussing combinations of words; and different terms are

used to express the same idea (phrase, combination of words, cluster

of words, word group).

9. The Sentence

When

we speak or write we convey our thougths through sentences. A

sentence is the only unit of language which is capable of expressing

a communication containing some kind of information. But linguistics

is at difficulty to define it. One of the definitions is ‘the

sentence is the smallest communication unit expressing a more or less

complete thought and having a definite grammatical structure and

intonation’. In most sentences intonation functions as part of a

whole system of formal characteristics.

The sentence and the word group (phrase)

Neither

words no word groups can express communication. Cf. the arrival of

the delegation is expected next week (a sentence). It is a structure

in which words are grouped (arranged) according to definite rules

(patterns).

Another

difference between the sentence and the phrase is predicativity.

Predicativity comprises tense and mood components. The sentence

together with predicativity expresses a fact, while a phrase gives a

nomination without time reference:

The

doctor arrived. The doctor’s arrival.

Predication

is a word or combination of words expressing predicativity. Thus the

essential property of sentence is predicativity and intonation.

Classification of Sentences

Sentences

are classified 1) according to the types of communication and 2)

according to their structure.

In

accordance with the types of communication sentences are divided

into:

Declarative

(giving information). E.g. the book is interesting (statement).

Interrogative

(asking for information). E.g. is the book interesting? (question).

Imperative

(asking for action). E.g. give me the book! (command, request).

Each

of these 3 kinds of sentences may be in the affirmative and negative

form, exclamatory and non- exclamatory.

Types of

Sentences According to Structure

I

a) Simple sentences containing one predication (subject-predicate

relationship)

b)

Composite sentences containing one or more predications Composite

sentences are divided into compound and complex sentences.

II.

Simple sentences and main clauses may be two-member and one-member

sentences.

The

two-member sentence pattern is typical of the vast majority of

sentences in English. It is a sentence with full predication. (The

Sun shines. She walks fast).

If

a simple sentence contains the subject and the predicate only, it is

called unextended. E.g. spring came.

If

a sentence comprises secondary parts besides the main parts, it is

called extended. E.g. Dick came home late.

The

one-member sentence contains only one principle part, which is

neither the subject nor the predicate. E.g. Thieves! Fire! A cup of

tea, please! A one-member sentence sometimes resembles a two-member

sentence. E.g. No birds singing in the dawn. It may be complex in

structure: e.g. And what if he had seen them embracing in the

moonlight?

Imperative

sentences with no subject also belong here: Get away from me!

If

the main part is expressed by an infinitive, such a one-member

sentence is called an infinitive sentence: Oh, to be in England!

The

exclamatory character is a necessary feature of these sentences.

Infinitive sentences are very common in represented speech.

Types of

One-member Sentences in English

Nominative

(substantive) E.g. Another day of fog.

Verbal

(Imperative: Don’t believe him! ,Infinitive: Only to think of it!

,Gerundial: No playing with fire!)

Adjectival

one-member sentences: Splendid! How romantic!

Types of

Sentences According to their Completeness

-

Complete

(non-elliptical) sentences. -

Incomplete

(elliptical) sentences.

Elliptical

sentences are such sentences in which one or several parts are

missing as compared with analogous sentences where there is no

ellipsis. Elliptical sentences may freely be changed into complete

sentences, the missing part of the sentence being supplied from the

preceding or following context, by means of intonation: e.g. I sat

near the window, he – near the door (= he sat near the door).

Playing, children? (= are you playing, children?) Cf. A small but

cosy room (a one-member sentence); in the background stands/ is a

little writing table (an elliptical two-member sentence). The main

sphere of elliptical sentences is of course dialogue.

Соседние файлы в папке Gosy

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Fluent speakers of any language will have intuitions on what word order sounds «natural» or «correct», but languages differ in what order they put words in. Linguists (specifically syntacticians) are interested in figuring out what ways languages can differ in how they organize sentences, as well as how they are similar. In this blogpost I will discuss some word-order differences across languages and how linguists model these differences though Phrase Structure Rules.

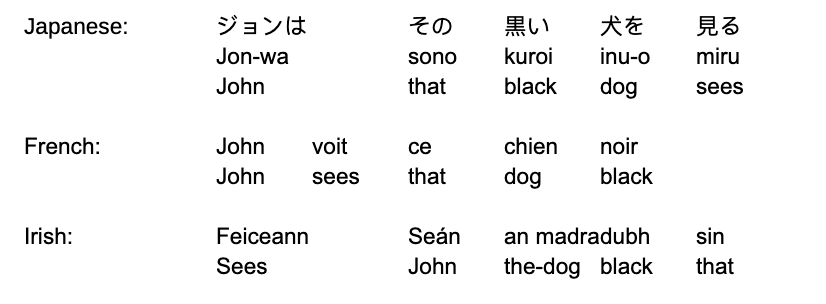

First, let’s take a look at the English sentence below, and its translation into Japanese, French, and Irish.

English: John sees that black dog

Ignoring the particles in the Japanese example and the article “an” in the Irish example, these sentences all have the same kinds of words: a word for “seeing”, a word for “that”, and so on, and yet they all put these words in different orders.

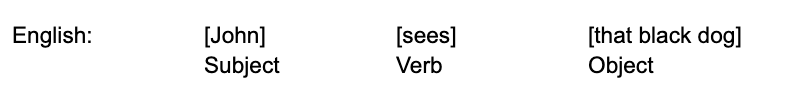

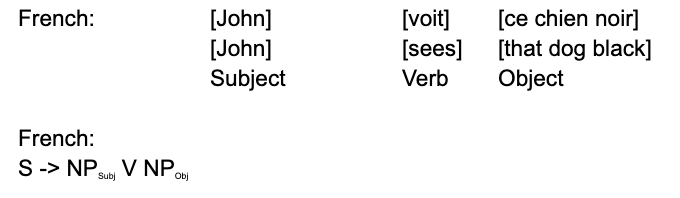

At a first glance, it may not be clear if there is a pattern to be seen, but it turns out that there is. In English grammar classes, you may have been taught to identify a subject, verb, and object, and we see all of these in each language. Let’s take a look at the English first:

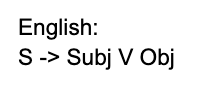

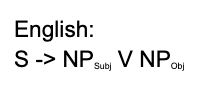

There are two things to notice here. The first is that English has Subject-Verb-Object order, where the subject precedes the verb and the verb precedes the object. We can represent this by saying that English has a Phrase Structure Rule that says that a sentence S consists of a subject, verb, and object in that order.

Phrase Structure Rules are composed of an “input”, which designates the kind of phrase which you one is building, and an “output”, which designates the smaller parts (or constituents) that the “input” consists of, and the order in which those constituents appear.

This rule has the sentence S on the left side, which corresponds to Subj V Obj on the right side. While the Verb is (appropriately called) a verb, the subject and object are both noun phrases, that is, they both contain nouns and optionally other things which modify the noun. So another way of writing this more clearly may be shown below, where we denote the subject and object as noun phrases (NP).

The second thing to notice is that in the example, while the subject “John” and the verb “sees” are both one word, the object “that black dog” is three words, but takes up a single role in the sentence. Groups of words within some phrase which combine together to form a unit are called phrases. So we can say that “that”, “black”, and “dog” form a phrase separate from “John” or “sees”. We already have a name for this kind of phrase, namely a noun phrase (NP).

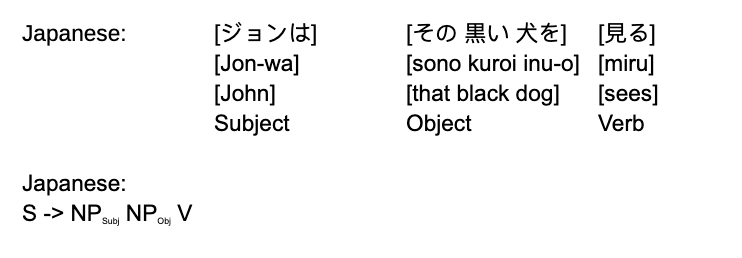

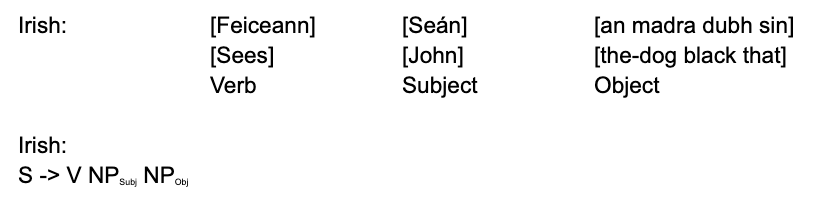

Let’s take a look at the other languages we have to see how they measure up:

French seems similar to English, both have the subject first, followed by the verb, and then the object. We can thus write the rule that we did for English for French:

Japanese has the object placed before the verb, what is typically called SOV order. Many other languages like Turkish, Korean, Hindi, and Burmese. We will write its rule accordingly.

Finally, Irish has the verb placed before the subject: this is typically called VSO order. Other VSO languages include Hawaiian, Classical Arabic, and Mayan. We will also write its rule accordingly.

In all of these languages, the object of this sentence stays as a single unit, even though it may be in different positions within the sentence. This means that across languages, even though word order may be different, it is still restricted to a certain set of word orders, where the main constituents of a phrase are next to each other.

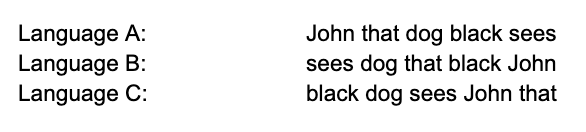

An interesting result of this observation is that we can predict that certain languages can exist while others can’t. For example, we can imagine three languages which would translate our English sentence into the following orders:

Language A and Language B could be actual human languages, as “that black dog” stays a single unit (though their word order changes). Language C, however, splits “that black dog” so that “that” appears disconnected from “black dog”. The Phrase Structure Rules for a sentence can determine the position of subject, verb, and object, but cannot break the object so that part of it appears before the verb and part of it appears after. Because of this, there is no Phrase Structure Rule to give us Language C, and we predict that no language like that exists.

While languages seem to differ in huge ways in terms of word order, we can use our rewriting rules to condense their differences into simple, easy to read diagrams. While we’ve only looked at a small subset of the world’s languages, and at a fairly simple sentence, we are still able to make predictions about the world’s languages and find connections between all languages, simply by using the Phrase Structure Rules. As an extra, try figuring out the Phrase Structure Rules for each of the four languages NPs, given the orders of the words for “dog”, “black”, and “that” in each language!

A phrase is a group of words functioning as a syntactical unit. It’s a broad term, comprising groups of words of many different types and functions. Phrases function as all parts of speech, as both subjects and predicates, as clauses, as idioms, and as figures of speech. This is by no means a complete list of the functions of phrases, though, as virtually any small group of words can be called a phrase.

Background

There are no rules governing what does and what does not constitute a phrase. The term is not as specifically defined as, say, a clause. Think of a phrase as a group of words that go together somehow. For example, the dog on the roof is a phrase that functions as a noun, but the phrase can be broken down further into a noun phrase, the dog, and a prepositional phrase (which also functions as an adjectival phrase), on the roof.

Unlike a sentence or a clause, a phrase doesn’t need both a subject and a predicate. What can be said about phrases is that they usually have focal points, sometimes known as heads. For example, in the phrase the dog on the roof, the noun dog is the head because it determines the nature of the phrase. But not all phrases have heads. For example, the phrase big, red, and smelly is just a list of adjectives, so it does not have a head.

Types of phrases

Adverbial phrases

An adverbial phrase is a group of two or more words that together function adverbially. Adverbial phrases that have both subjects and predicates are usually referred to as adverbial clauses.

In the simple sentence He ran, the verb ran can be modified in several ways. It can be modified with a single-word adverb—for example, He ran quickly, He ran wildly, or He ran backwards. Or the verb can be modified with a phrase—for example, He ran toward the ball, He ran for five miles, or He ran faster than a speeding bullet. In each of these examples, the phrase following ran qualifies the verb and is thus an adverbial phrase. Incidentally, the first two (toward the ball and for five miles) also qualify as prepositional phrases.

Here are some other examples of adverbial phrases:

Mrs Hilal speaks in a low, deep voice. [The phrase in a low, deep voice modifies speaks.]

Those concerns over possible double-dealing spiked a week ago … [Washington Post] [The phrase a week ago modifies spiked.]

The United States generally erred on the side of caution. [National Interest] [The phrase on the side of caution modifies erred.]

Adverbial phrases are commonly used to start sentences. These are usually set apart by commas—for example:

For decades, Utah let condemned prisoners choose whether to die by hanging or the firing squad … [New York Times] [For decades modifies let.]

In 1690, the Massachusetts Bay Colony became the first government in the Western world to issue paper money. [Wall Street Journal] [In 1690 modifies became.]

Noun phrases

A noun phrase consists of a noun accompanied by its modifiers. The modifiers may be adjectives, conjunctions, other nouns, prepositional phrases, or any other words that apply directly to the noun.

The main noun of a noun phrase is the head. It’s the one essential element of the phrase.

For example, this sentence has two noun phrases, overtures to Washington and recent days:

China has also made overtures to Washington in recent days. [NY Times]

The heads of these noun phrases are overtures and days.

And this sentence has two very long noun phrases:

He also warned that the problem of financial institutions being perceived as “too big to fail” has become prevalent, despite proposals in Congress that seek to permanently end taxpayer bailouts of large financial institutions. [NY Times]

The head of the of the noun phrase the problem of financial institutions being perceived as “too big to fail” is problem. The head of the noun phrase proposals in Congress that seek to permanently end taxpayer bailouts of large financial institutions is proposals. Both noun phrases contain smaller noun phrases—including financial institutions and taxpayer bailouts of large financial institutions.

Prepositional phrases

A prepositional phrase is a phrase consisting of a preposition, its prepositional object, and any words modifying that object.

Prepositional phrases may be nouns—for example, for him to do that in this sentence:

For him to do that took courage.

Prepositional phrases may also be adverbs (in which case they’re also known as adverbial phrases). In this sentence, for example, above the tree line modifies the verb walked:

We walked above the tree line.

And they may function as adjectives. In this sentence, for example, of the city modifies the noun streets:

We strolled the streets of the city.

Adjectival and adverbial phrases should be placed as near as possible to the words they modify. Otherwise, confusion can result. For example, this sentence is misleading:

I’m looking for a girl who was here an hour ago in a red dress.

This sentence would be clearer as,

I’m looking for a girl in a red dress who was here an hour ago.

Also, when a prepositional phrase modifies multiple elements in a list, the phrase should follow the last element—for example:

The bread, the apples, and the peanut butter in the kitchen all belong to Bill.

|

phrase | word | Synonyms | Word is a synonym of phrase.Word is a conjunction of phrase.In transitive terms the difference between phrase and wordis that phrase is to express (an action, thought or idea) by means of words while word is to ply or overpower with words. As nouns the difference between phrase and wordis that phrase is a short written or spoken expression while word is the smallest unit of language which has a particular meaning and can be expressed by itself; the smallest discrete, meaningful unit of language. Contrast morpheme. As verbs the difference between phrase and wordis that phrase is to perform a passage with the correct phrasing while word is to say or write (something) using particular words; to phrase (something). As an interjection word istruth, indeed, to tell or speak the truth; the shortened form of the statement, «My word is my bond,» an expression eventually shortened to «Word is bond,» before it finally got cut to just «Word,» which is its most commonly used form. Other Comparisons: What’s the difference?

|

Normally, sentences in the English language take a simple form. However, there are times it would be a little complex. In these cases, the basic rules for how words appear in a sentence can help you.

Word order typically refers to the way the words in a sentence are arranged. In the English language, the order of words is important if you wish to accurately and effectively communicate your thoughts and ideas.

Although there are some exceptions to these rules, this article aims to outline some basic sentence structures that can be used as templates. Also, the article provides the rules for the ordering of adverbs and adjectives in English sentences.

Basic Sentence Structure and word order rules in English

For English sentences, the simple rule of thumb is that the subject should always come before the verb followed by the object. This rule is usually referred to as the SVO word order, and then most sentences must conform to this. However, it is essential to know that this rule only applies to sentences that have a subject, verb, and object.

For example

Subject + Verb + Object

He loves food

She killed the rat

Sentences are usually made of at least one clause. A clause is a string of words with a subject(noun) and a predicate (verb). A sentence with just one clause is referred to as a simple sentence, while those with more than one clause are referred to as compound sentences, complex sentences, or compound-complex sentences.

The following is an explanation and example of the most commonly used clause patterns in the English language.

Inversion

Inversion

The English word order is inverted in questions. The subject changes its place in a question. Also, English questions usually begin with a verb or a helping verb if the verb is complex.

For example

Verb + Subject + object

Can you finish the assignment?

Did you go to work?

Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive Verbs

Some sentences use verbs that require no object or nothing else to follow them. These verbs are generally referred to as intransitive verbs. With intransitive verbs, you can form the most basic sentences since all that is required is a subject (made of one noun) and a predicate (made of one verb).

For example

Subject + verb

John eats

Christine fights

Linking Verbs

Linking Verbs

Linking verbs are verbs that connect a subject to the quality of the subject. Sentences that use linking verbs usually contain a subject, the linking verb and a subject complement or predicate adjective in this order.

For example

Subject + verb + Subject complement/Predicate adjective

The dress was beautiful

Her voice was amazing

Transitive Verbs

Transitive Verbs

Transitive verbs are verbs that tell what the subject did to something else. Sentences that use transitive verbs usually contain a subject, the transitive verb, and a direct object, usually in this order.

For example

Subject + Verb + Direct object

The father slapped his son

The teacher questioned his students

Indirect Objects

Indirect Objects

Sentences with transitive verbs can have a mixture of direct and indirect objects. Indirect objects are usually the receiver of the action or the audience of the direct object.

For example

Subject + Verb + IndirectObject + DirectObject

He gave the man a good job.

The singer gave the crowd a spectacular concert.

The order of direct and indirect objects can also be reversed. However, for the reversal of the order, there needs to be the inclusion of the preposition “to” before the indirect object. The addition of the preposition transforms the indirect object into what is called a prepositional phrase.

For example

Subject + Verb + DirectObject + Preposition + IndirectObject

He gave a lot of money to the man

The singer gave a spectacular concert to the crowd.

Adverbials

Adverbials

Adverbs are phrases or words that modify or qualify a verb, adjective, or other adverbs. They typically provide information on the when, where, how, and why of an action. Adverbs are usually very difficult to place as they can be in different positions in a sentence. Changing the placement of an adverb in a sentence can change the meaning or emphasis of that sentence.

Therefore, adverbials should be placed as close as possible to the things they modify, generally before the verbs.

For example

He hastily went to work.

He hurriedly ate his food.

However, if the verb is transitive, then the adverb should come after the transitive verb.

For example

John sat uncomfortably in the examination exam.

She spoke quietly in the class

The adverb of place is usually placed before the adverb of time

For example

John goes to work every morning

They arrived at school very late

The adverb of time can also be placed at the beginning of a sentence

For example

On Sunday he is traveling home

Every evening James jogs around the block

When there is more than one verb in the sentence, the adverb should be placed after the first verb.

For example

Peter will never forget his first dog

She has always loved eating rice.

Adjectives

Adjectives

Adjectives commonly refer to words that are used to describe someone or something. Adjectives can appear almost anywhere in the sentence.

Adjectives can sometimes appear after the verb to be

For example

He is fat

She is big

Adjectives can also appear before a noun.

For example

A big house

A fat boy

However, some sentences can contain more than one adjective to describe something or someone. These adjectives have an order in which they can appear before a now. The order is

Opinion – size – physical quality – shape – condition – age – color – pattern – origin – material – type – purpose

If more than one adjective is expected to come before a noun in a sentence, then it should follow this order. This order feels intuitive for native English speakers. However, it can be a little difficult to unpack for non-native English speakers.

For example

The ugly old woman is back

The dirty red car parked outside your house

When more than one adjective comes after a verb, it is usually connected by and

For example

The room is dark and cold

Having said that, Susan is tall and big

Get an expert to perfect your paper