Basic Terms and Terminology Relating to Interpreting the Meaning of Words and Phrases Using Context

- Slang and jargon: Slang and jargon are words that have a special meaning to those included in a particular group and without any meaning to those not included in that particular group.

- Colloquialisms; informal words and phrases that are conversational, everyday words and phrases that are acceptable in informal writing and speech, but not acceptable in terms of formal writing and speech.

- Idioms: A collection or a group of words that has become somewhat acceptable in the English language because of their ongoing and consistent use, despite the fact that the group of words does not have a literal meaning. Idioms have figurative meanings, therefore, the meaning of an idiom cannot be inferred or deduced in the same manner that words and phrases with literal meanings do.

- Literal meaning of words: The meaning of a phrase, clause or sentence that can be logically inferred and deduced from the true dictionary accurate definitions of the words in a phrase, clause or sentence. The literal meaning of words is the opposite of the figurative meaning of words.

- Figurative meaning of words: The meaning of a phrase, clause or sentence that cannot be logically inferred and deduced from the true dictionary accurate definitions of the words in a phrase, clause or sentence. The figurative meaning of words is the opposite of the literal meaning of words.

- The root of a word: Also referred to as the base of a word and the stem of a word, is the main part of a word without any syllables before the root of the word, which is a prefix, or after the root of the word, which is a suffix.

- Prefixes: The part of a word that is connected to and before the stem or root of a word

- Suffixes: The part of a word that is connected to and after the stem of the word. Some suffixes, like «s», «es», «d» and «ed» which make words plural or of the past tense, are quite simple but others are more complex.

- Antonyms: Words that have opposite meanings and can give the reader a context clue to determine the meaning of words and phrases

- Synonyms: Words that have the same meaning and can give the reader a context clue to determine the meaning of words and phrases

- Homophones are two or more words that sound identical and the same but are spelled differently and have different meanings.

- Homographs are words that, as the name suggests, look the same and are spelled (graph) the same (homo) but have two distinctly different meanings and that are either pronounced differently or pronounced the same. For obvious reasons, these words are.

- Contronyms: Words that are spelled the same but they have different meanings; these contronyms can give the reader a context clue to determine the meaning of words and phrases

- Context: Simply defined, context is the surrounding information and clues that occur prior to and after the word or phrase that is not known or misunderstood.

In reality, it is most likely that no human being is able to instantly and spontaneously know the meaning of ALL words and phrases using their memory and by rote. For this reason, many, if not most, human beings use electronic and hard copy references to determine the meanings of words and phrases. For example, when a reader does not know the meaning of a particular word or phrase they can, and should, look it up using a reference such as:

- An online electronic dictionary

- An online electronic thesaurus

- A hard copy dictionary such as the Miriam Webster Dictionary

- A hard copy thesaurus such as Roget’s Thesaurus

Please note that the above references cannot be used on the TEAS examination, therefore, you must employ other skills to determine the meanings of words and phrases that are not known to you.

Skills, other than those used to utilize online and hardcopy references to determine the meanings of words and phrases, will be discussed and described in the section below.

Barriers Relating to the Determination of the Meanings of Words and Phrases

Although there are several skills that can be successfully and accurately employed to discover the meaning of unknown words and phrases, some of these words and phrases are more challenging and difficult than others. Knowledge of some of these more challenging and difficult words and phrases can assist you to discover and decipher the meanings of unknown words and phrases.

Some of the barriers relating to the determination of the meanings of words and phrases include the use of:

- Slang and Jargon

- Colloquialisms

- Idioms

- Figurative Meanings

- Figures of Speech

Slang and Jargon

Slang and jargon are words that have a special meaning to those included in a particular group and without any meaning to those outside of the group and not included in that particular group. Examples of some of these groups that may know the meaning of a particular slang word and jargon include nurses, the young age group, the older age group, school teachers and those in the military.

Because slang and jargon are only readily recognized and defined by only some or a few, it is necessary for others to employ other skills to discover the meaning of slang and jargon in a reading text or with the spoken word.

Examples of slang words include:

- Dig it (Meaning understand it)

- Gig (Meaning a job)

- On the up and up (Meaning proper and honest)

- The cat’s meow (Meaning stylish)

- Spiffy (Meaning fashionable and stylish)

- Left holding the bag (Meaning being falsely accused of something)

- Psych out (Meaning being tricked or deceived)

- Far out (Meaning in style or advanced)

- Hip (Meaning cool and contemporary)

- Cool it (Meaning calm down)

- The skinny (Meaning the facts and the truth)

- Cool (Meaning cool and contemporary)

Examples of slang words that have a special meaning to those included in a group and without any meaning for those not included in the particular group include:

- The brig (Meaning military prison)

- Hall duty (A teacher’s assignment to monitor the hallways when students are moving from one classroom to another or exiting the building at the end of the school day)

- On the beat (Meaning working for police officers)

- On the job (Meaning employed as a police officer)

- Shift (Meaning hours of scheduled work for nurses and police officers)

Many uses of jargon in the written word and with the spoken word include abbreviations while others do not.

Examples of jargon that has a special meaning to those included in a group and without any meaning for those not included in the particular group include:

- NPO (The abbreviation for the Latin term nil per os which means nothing by mouth which is used by nurses and other health care workers)

- AWOL (The military abbreviation for absent without leave. Absent without leave means an unauthorized failure to appear for duty as scheduled)

- Etiology (A cause of a disease or disorder. Etiology is often used among nurses and other healthcare professionals)

Colloquialisms

Colloquialisms are informal words and phrases that are conversational, everyday words and phrases that are acceptable in informal writing and speech, but not acceptable in terms of formal writing and speech. Many colloquialisms are misspelled and some are only understandable to a particular geographic area of the United States. Additionally, colloquialisms have figurative meanings rather than literal meanings. For this reason, skills other than using online and hardcopy resources to discover the meanings of these colloquialisms are necessary.

Some colloquialisms include:

- Put out (Meaning inconvenienced)

- Shove off (Meaning leave)

- Go nuts (Meaning going insane)

- Sort of (Meaning kind of)

- What’s up (Meaning what’s happening)

- Wanna (Meaning want to)

- Going bananas (Meaning going crazy or getting angry)

- All wet (Meaning confused and incorrect)

- Gonna (Meaning going to)

- Buzz off (Meaning go away)

- The middle finger (Meaning a profane gesture)

- Go to hell (Meaning a curse)

Colloquialisms may also vary and differ among various geographical regions in the United States. For example, the southern states of our nation may use the colloquialism like «y’all» which is understandable by southern Americans to mean «all of you» but not always understandable to those in other regions of our country.

Idioms

Idioms are a collection or a group of words that has become somewhat acceptable in the English language because of their ongoing and consistent use, despite the fact that the group of words do not have a literal meaning. Idioms have figurative meanings, therefore, the meaning of an idiom cannot be inferred or deduced in the same manner that the meanings of words and phrases with literal meanings can be inferred or deduced.

Many idioms are proverbs such as, «You cannot judge a book by its cover» and «The pen is mightier than the sword». These proverbs do not have literal meanings, but instead, they have figurative meanings. For example, the proverb «You cannot judge a book by its cover» does not mean that the contents of a book cannot be judged by its exterior cover. Instead, this proverb, as a proverb and an idiom, means that first impressions of people, places and things are not always accurate and they can be highly misleading. For example, a person’s attire does not necessarily offer any facts or reliable information about the person, their character or their values, for example. And the proverb or idiom «The pen is mightier than the sword» has little to do with a pen or a sword. Instead, this proverb suggests that we are much more likely to convince people and succeed with others with our written or oral words rather than force, aggression and/or hostility.

Some commonly used idioms and their figurative meanings are listed below:

- A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

Figurative meaning: Having something is worth more than having to get more with effort or taking the chance of losing the «one bird» that you already have.

- Stuck between a rock and a hard place

Figurative meaning: Both choices are equally difficult

- Spill the beans

Figurative meaning: Divulging a secret

- Kick the bucket

Figurative meaning: Die

- Hit the sack or hit the hay

Figurative meaning: Going to bed

- Cold shoulder

Figurative meaning: Unfriendly and cold

- A piece of cake

Figurative meaning: Simple and easy

- This situation is black or white

Figurative meaning: A situation that is clear and unambiguous

- Killing two birds with one stone

Figurative meaning: Accomplishing more than one thing with a singular action

- Chickening out

Figurative meaning: Opting out of something because of fear and nervousness

As you are taking your TEAS examination, you may be asked to demonstrate your ability to comprehend a reading passage that contains one or more idioms. If you don’t understand the idiom, you should attempt to discover its meaning by looking at the idiom in the context of the sentence, or the paragraph or the entire reading passage. Context often gives us a lot of information about not only idioms but also about words that you do not know the meaning of.

Figurative Meanings of Words and Phrases

A figurative meaning of a word is the opposite, or antonym, for the literal meaning of a word.

The literal meaning of words is defined as the dictionary definition of the word; the literal meaning of a phrase, clause or sentence can be logically inferred and deduced from the true dictionary accurate definitions of the words in a phrase, clause or sentence. The literal meaning of words is the opposite of the figurative meaning of words.

The figurative meaning of words is defined as the meaning of a phrase, clause or sentence that cannot be logically inferred and deduced from the true dictionary accurate definitions of the words in a phrase, clause or sentence. The figurative meaning of words is the opposite of the literal meaning of words.

Although you may be very certain of some figurative meanings, you may not at all be able to understand and decipher many others. For this reason you will have to use and employ skills other than dictionary skills to determine the meaning of a word or phrase.

Figures of Speech

Some figures of speech like a simile, a metaphor and personification pose challenges to the understanding of comprehension of words and phrases in a reading text as well as with the spoken word.

Similes are a figure of speech that compares two unlike things; similes typically include the word «like» or «as». A metaphor is the figure of speech that involves a comparison of two things that are not similar but they have some single characteristic in common; and personification is also a figure of speech. Personification entails giving lifelike and human characteristics to an inanimate and/or non human thing or being.

Figures of speech, similar to slang, jargon, colloquialisms, idioms, and figurative meanings add confusion with their special challenges to reading comprehension. In fact these elements in the spoken and written word make the English language one of the most, if not the most, difficult language to master.

An example of a simile is «She was as red as a beet».

An example of a metaphor is «Her skin was snow white».

An example of personification is «The wind pranced through the trees.»

In summary, some of the barriers relating to the determination of the meanings of words and phrases, such as those used with and in slang, jargon, colloquialisms, idioms and words with a figurative meaning, are challenging and difficult, however, the skillful use of noncontextual and contextual reading comprehension skills can often overcome these barriers.

Using Skills Other Than Contextual Skills to Discover the Meanings of Unknown Words and Phrases

As just stated above, the skillful use of noncontextual and contextual reading comprehension skills can often overcome barriers to this comprehension.

Some of the skills, other than the use of contextual skills, that facilitate the comprehension and understanding of words and phrases that are unknown to the reader of a text and the receiver of a spoken message include

- Deciphering the Meanings of Words by Mastering the Meanings of Prefixes, Suffixes and Stems of Words

The following can be read more about within our Using Context Clues to Determine the Meaning of Words or Phrases section:

- Getting Clues From Antonyms and Synonyms

The following can be read more about within our Using Conventions of Standard English Spelling section:

- Learning Homophones and Homographs

RELATED TEAS CRAFT & STRUCTURE CONTENT:

- Distinguishing Between Fact and Opinion, Biases, and Stereotypes

- Recognizing the Structure of Texts in Various Formats (Currently here)

- Interpreting the Meaning of Words and Phrases Using Context

- Determining the Denotative Meaning of Words

- Evaluating the Author’s Purpose in a Given Text

- Evaluating the Author’s Point of View in a Given Text

- Using Text Features

- Author

- Recent Posts

Alene Burke, RN, MSN

Alene Burke RN, MSN is a nationally recognized nursing educator. She began her work career as an elementary school teacher in New York City and later attended Queensborough Community College for her associate degree in nursing. She worked as a registered nurse in the critical care area of a local community hospital and, at this time, she was committed to become a nursing educator. She got her bachelor’s of science in nursing with Excelsior College, a part of the New York State University and immediately upon graduation she began graduate school at Adelphi University on Long Island, New York. She graduated Summa Cum Laude from Adelphi with a double masters degree in both Nursing Education and Nursing Administration and immediately began the PhD in nursing coursework at the same university. She has authored hundreds of courses for healthcare professionals including nurses, she serves as a nurse consultant for healthcare facilities and private corporations, she is also an approved provider of continuing education for nurses and other disciplines and has also served as a member of the American Nurses Association’s task force on competency and education for the nursing team members.

Latest posts by Alene Burke, RN, MSN (see all)

-

The

object of Comparative Lexicology as a branch of linguistic science

Lexicology

(from Gr lexis

‘word’

and logos

‘learning’)

is the part of

linguistics dealing with the vocabulary of the language and the

properties

of words as the main units of language. The term vocabulary

is used to denote the system formed by the sum total of all the words

and

word equivalents

that the language possesses. The term word

denotes the basic unit of a given language resulting from the

association of a particular meaning with a particular group of sounds

capable of a particular grammatical employment. A word therefore is

simultaneously a semantic, grammatical and phonological unit.

Thus,

in the word boy

the

group of sounds [bOI]

is associated with the meaning ‘a male child up to the age of 17 or

18’ (also with some other

meanings, but this is the most frequent) and with a definite

grammatical

employment, i.e. it is a noun and thus has a plural form — boys,

it

is a personal noun and has the Genitive form boy’s

(e.

g. the

boy’s mother), it

may be used in certain syntactic functions.

The

general study of words and vocabulary, irrespective of the specific

features of any particular language, is known as general

lexicology.

Linguistic phenomena and properties common to all languages are

generally referred to as language

universals.

Special

lexicology

devotes

its attention to the description

of the characteristic peculiarities in the vocabulary of a given

language.

Every

special lexicology is based on the principles

of general lexicology, and the latter forms a part of general

linguistics.

The

relatively new branch of study is called contrastive

lexicology:

a theoretical basis on which the vocabularies of different languages

can be compared and

described.

The

evolution of any vocabulary, as well as of its single elements, forms

the object of historical

lexicology

or etymology which

discusses the origin of various words, their

change and development, and investigates the linguistic and

extra-linguistic

forces modifying their structure, meaning and usage.

Descriptive

lexicology

deals with the vocabulary of a

given language at a given stage of its development. It studies the

functions

of words and their specific structure as a characteristic inherent in

the system. The descriptive lexicology of the English language deals

with the English word in its morphological and semantical structures,

investigating the interdependence between these two aspects. These

structures

are identified and distinguished by contrasting the nature and

arrangement of their elements.

It

will, for instance, contrast the word boy

with

its derivatives: boyhood,

boyish, boyishly, etc.

It will describe its semantic structure comprising

alongside with its most frequent meaning, such variants as ‘a

son of any age’, ‘a male servant’, and observe its syntactic

functioning and

combining possibilities. This word, for instance, can be also used

vocatively

in such combinations as old

boy, my dear boy, and

attributively, meaning ‘male’, as in boy-friend.

Lexicology

also studies all kinds of semantic grouping and semantic relations:

synonymy,

antonymy, hyponymy, semantic fields,

etc.

Meaning

relations as a whole are dealt with in semantics

— the

study of meaning which is relevant both for lexicology and grammar.

The

distinction between the two basically different ways in which

language

may be viewed, the historical

or diachronic

(Gr

dia

‘through’

and chronos

‘time’)

and the descriptive

or synchronic

(Gr syn

‘together’,

‘with’), is a methodological distinction, a difference of

approach, artificially separating for the purpose

of study what in real language is inseparable, because every

linguistic structure and system exists in a state of constant

development.

The

distinction between a synchronic and a diachronic approach is

due to the Swiss philologist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913).1

Indebted

as we are to him for this important dichotomy, we cannot accept

either his axiom that synchronic linguistics is concerned with

systems and diachronic linguistics with single units or the rigorous

separation

between the two. Subsequent investigations have shown the possibility

and the necessity of introducing the historical point of view into

systematic studies of languages.

Language

being

a means of communication

the social essence is intrinsic

to the language itself. Whole groups of speakers, for example, must

coincide in a deviation, if it is to result in linguistic change.

The

branch of linguistics, dealing with causal relations between the way

the language works and develops, on the one hand, and the facts

of social life, on the other, is termed sociolinguistics.

Some

scholars use this term in a narrower sense, and maintain that it is

the analysis of speech behaviour in small social groups that is the

focal point of sociolinguistic analysis. A. D. Schweitzer has proved

that

such microsociological approach alone cannot give a complete picture

of the sociology of language. It should be combined with the study of

such macrosociological factors as the effect of mass media, the

system of

education, language planning, etc. An analysis of the social

stratification

of languages takes into account the stratification of society as a

whole.

Although

the important distinction between a diachronic and a synchronic, a

linguistic and an extralinguistic approach must always be borne

in mind,

yet it is of paramount importance for the student to take into

consideration that in language reality all the aspects are

interdependent

and cannot be understood one without the other. Every linguistic

investigation must strike a reasonable balance between them.

The

lexicology of present-day English, therefore, although having aims

of its own, different from those of its historical counterpart,

cannot be

divorced from the latter. In what follows not only the present status

of

the English vocabulary is discussed: the description would have been

sadly

incomplete if we did not pay attention to the historical aspect of

the problem — the ways and tendencies of vocabulary development.

Being

aware of the difference between the synchronic approach involving

also social and place variations, and diachronic approach we shall

not tear them asunder, and, although concentrating mainly on the

present

state of the English vocabulary, we shall also have to consider its

development. Much yet remains to be done in elucidating the complex

problems and principles of this process before we can present a

complete and accurate picture of the English vocabulary as a system,

with

specific peculiarities of its own, constantly developing and

conditioned

by the history of the English people and the structure of the

language.

-

The

connection of Comparative Lexicology with other branches of

linguistics

The

treatment of words in lexicology cannot be divorced from the study

of all the other elements in the language system to which words

belong. It should be always borne in mind that in reality, in the

actual process

of communication, all these elements are interdependent and stand in

definite relations to one another. We separate them for convenience

of study, and yet to separate them for analysis is pointless, unless

we

are afterwards able to put them back together to achieve a synthesis

and see their interdependence and development in the language system

as a whole.

The

word, as it has already been stated, is studied in several branches

of

linguistics and not in lexicology only, and the latter, in its turn,

is closely

connected with general linguistics, the history of the language,

phonetics,

stylistics, grammar and such new branches of our science as

sociolinguistics,

paralinguistics, pragmalinguistics and some others.1

The

importance of the connection between lexicology and phonetics

stands explained if we remember that a word is an association of a

given group of sounds with a given meaning, so that top

is

one word, and tip

is

another. Phonemes have no meaning of their own but they serve to

distinguish between meanings. Their function is building

up morphemes, and it is on the level of morphemes that the

form-meaning

unity is introduced into language. We may say therefore that phonemes

participate in signification.

Word-unity

is conditioned by a number of phonological features. Phonemes

follow each other in a fixed sequence so that [pit] is different from

[tip]. The importance of the phonemic make-up may be revealed by the

substitution

test

which isolates the central phoneme of hope

by

setting it against hop,

hoop, heap or

hip.

An

accidental or jocular transposition of the initial sounds of two or

more words, the so-called spoonerisms

illustrate the same

Discrimination

between the words may be based upon stress: the word ‘import

is

recognised as a noun and distinguished from the verb im’port

due

to the position of stress. Stress also distinguishes compounds from

otherwise homonymous word-groups: ‘blackbird

: : ‘black

‘bird.

Each

language also possesses certain phonological features marking

word-limits.

Historical

phonetics and historical phonology can be of great use in

the diachronic study of synonyms, homonyms and polysemy. When sound

changes loosen the ties between members of the same word-family, this

is an important factor in facilitating semantic changes.

The

words whole,

heal, hail, for

instance, are etymologically related.

The

word whole

originally

meant ‘unharmed’, ;unwounded’.

The early verb whole

meant

to make whole’, hence ‘heal’. Its sense of ‘healthy’ led

to its use as a salutation, as in hail!

Having

in the course of historical development

lost their phonetic similarity, these words cannot now exercise

any restrictive influence upon one another’s semantic development.

Thus, hail

occurs

now in the meaning of ‘call’, even with the purpose to stop and

arrest (used by sentinels).

Meaning

in its turn is indispensable to phonemic analysis because to

establish the phonemic difference between [ou] and [o] it is

sufficient to

know that [houp] means something different from [hop].

All

these considerations are not meant to be in any way exhaustive, they

can only give a general idea of the possible interdependence of the

two

branches of linguistics.

Stylistics,

although from a different angle, studies many problems

treated in lexicology. These are the problems of meaning,

connotations,

synonymy, functional differentiation of vocabulary according to the

sphere of communication and some other issues. For a reader

without some awareness of the connotations and history of words, the

images hidden in their root and their stylistic properties, a

substantial part of the meaning of a literary text, whether prosaic

or poetic, may be lost.

Thus,

for instance, the mood of despair in O. Wilde’s poem “Taedium

Vitae”

(Weariness of Life) is felt due to an accumulation of epithets

expressed

by words with negative, derogatory connotations, such as: desperate,

paltry, gaudy, base, lackeyed, slanderous, lowliest, meanest.

An

awareness of all the characteristic features of words is not only

rewarded

because one can feel the effect of hidden connotations and imagery,

but because without it one cannot grasp the whole essence of the

message the poem has to convey.

The

difference and interconnection between grammar

and lexicology

is

one of the important controversial issues in linguistics and as it is

basic to the problems under discussion in this book, it is necessary

to dwell upon it a little more than has been done for phonetics and

stylistics.

A

close connection between lexicology and grammar is conditioned by

the manifold and inseverable ties between the objects of their study.

Even

isolated words as presented in a dictionary bear a definite relation

to

the grammatical system of the language because they belong to some

part

of speech and conform to some lexico-grammatical characteristics of

the word class to which they belong. Words seldom occur in isolation.

They

are arranged in certain patterns conveying the relations between the

things for which they stand, therefore alongside with their lexical

meaning

they possess some grammatical meaning. Сf.

head

of the committee

and

to

head a committee.

The

two kinds of meaning are often interdependent. That is to say,

certain

grammatical functions and meanings are possible only for the words

whose lexical meaning makes them fit for these functions, and, on

the other hand, some lexical meanings in some words occur only in

definite

grammatical functions and forms and in definite grammatical patterns.

For

example, the functions of a link verb with a predicative expressed by

an adjective cannot be fulfilled by every intransitive verb but are

often taken up by verbs of motion: come

true, fall ill, go wrong, turn red,

run dry and

other similar combinations all render the meaning of ‘become

sth’. The function is of long standing in English and can be

illustrated

by a line from A. Pope who, protesting against blank verse, wrote:

It

is not poetry, but prose run mad.1

On

the other hand the grammatical form and function of the word affect

its lexical meaning. A well-known example is the same verb go

when

in the continuous tenses, followed by to

and

an infinitive (except go

and

come),

it

serves to express an action in the near and immediate future, or an

intention of future action: You’re

not going to sit there saying

nothing all the evening, both of you, are you? (Simpson)

The

number of words in each language being very great, any lexical

meaning has a much lower probability of occurrence than grammatical

meanings and therefore carries the greatest amount of information in

any discourse determining what the sentence is about.

W.

Chafe, whose influence in the present-day semantic syntax is quite

considerable, points out the many constraints which limit the

co-occurrence of words. He considers the verb as of paramount

importance in sentence semantic structure, and argues that it is the

verb that dictates the presence and character of the noun as its

subject or object. Thus, the verbs frighten,

amuse and

awaken

can

have only animate nouns as their objects.

The

constraint is even narrower if we take the verbs say,

talk or

think

for

which only animate human subjects are possible. It is obvious that

not all animate nouns are human.

This

view is, however, if not mistaken, at least one-sided, because the

opposite is also true: it may happen that the same verb changes its

meaning, when used with personal (human) names and with names of

objects. Compare: The

new girl gave him a strange smile (she

smiled at him) and The

new teeth gave him a strange smile.

These

are by no means the only relations of vocabulary and grammar. We

shall not attempt to enumerate all the possible problems. Let us turn

now to another point of interest, namely the survival of two

grammatically equivalent forms of the same word when they help to

distinguish between its lexical meanings. Some nouns, for instance,

have two separate plurals, one keeping the etymological plural form,

and the other with the usual English ending -s.

For

example, the form brothers

is

used to express the family relationship, whereas the old form

brethren

survives

in ecclesiastical usage or serves to indicate the members of some

club or society; the scientific plural of index,

is

usually indices,

in

more general senses the plural is indexes.

The

plural of genius

meaning

a person

of exceptional intellect is geniuses,

genius in

the sense of evil or good spirit

has the plural form genii.

It

may also happen that a form that originally expressed grammatical

meaning, for example, the plural of nouns, becomes a basis for a new

grammatically conditioned lexical meaning. In this new meaning it is

isolated from the paradigm, so that a new word comes into being.

Arms,

the

plural of the noun arm,

for

instance, has come to mean ‘weapon’. E.g. to

take arms against a sea of troubles (Shakespeare).

The grammatical form is lexicalised; the new word shows itself

capable of further development, a new grammatically conditioned

meaning appears, namely, with the verb in the singular arms

metonymically

denotes the military profession. The abstract noun authority

becomes

a collective in the term authorities

and

denotes ‘a group of persons having the right to control and

govern’. Compare also colours,

customs, looks, manners, pictures, works

which are the best known examples of this isolation, or, as is also

called, lexicalisation

of a grammatical form. In all these

words the suffix -s

signals

a new word with a new meaning.

It

is also worthy of note that grammar and vocabulary make use of the

same technique,

i.e. the formal distinctive features of some

derivational oppositions

between different words are the same

as those of oppositions contrasting different grammatical forms (in

affixation, juxtaposition of stems and sound interchange). Compare,

for example, the oppositions occurring in the lexical system, such as

work

::

worker,

power ::

will-power,

food ::

feed

with

grammatical oppositions:

work

(Inf.)

:: worked

(Past

Ind.), pour

(Inf.)

:: will

pour (Put.

Ind.), feed

(Inf.)

:: fed

(Past

Ind.). Not only are the methods and patterns similar, but the very

morphemes are often homonymous. For

example, alongside the derivational suffixes -en,

one

of which occurs in

adjectives (wooden),

and

the other in verbs (strengthen),

there

are two functional

suffixes, one for Participle II (written),

the

other for the archaic plural form (oxen).

Furthermore,

one and the same word may in some of its meanings function

as a notional word, while in others it may be a form word, i.e. it

may serve to indicate the relationships and functions of other words.

Compare, for instance, the notional and the auxiliary do

in

the following:

What

you do’s nothing to do with me, it doesn’t interest me.

Last

but not least all grammatical meanings have a lexical counterpart

that expresses the same concept. The concept of futurity may be

lexically expressed in the words future,

tomorrow, by and by, time to come, hereafter or

grammatically in the verbal forms shall

come and

will

come. Also

plurality may be described by plural forms of various words:

houses,

boys, books or lexically

by the words: crowd,

party, company,

group, set, etc.

The

ties between lexicology and grammar are particularly strong in

the sphere of word-formation which before lexicology became a

separate branch of linguistics had even been considered as part of

grammar. The characteristic features of English word-building, the

morphological structure of the English word are dependent upon the

peculiarity of the English

grammatical system. The analytical character of the language is

largely responsible for the wide spread of conversion1

and for the remarkable

flexibility of the vocabulary manifest in the ease with which many

nonce-words2

are formed on the spur of the moment.

This

brief account of the interdependence between the two important parts

of linguistics must suffice for the present. In future we shall have

to return to the problem and treat some parts of it more extensively.

-

A word

as a fundamental unit of the language

The

important point to remember about

definitions

is that they should indicate the most essential characteristic

features of the notion expressed by the term under discussion, the

features by which this notion is distinguished from other similar

notions. For instance, in defining the word one must distinguish it

from other linguistic units, such as the phoneme, the morpheme, or

the word-group. In contrast with a definition, a description

aims at enumerating all the essential features of a notion.

To

make things easier we shall begin by a preliminary description,

illustrating it with some examples.

The

word

may be described as the basic unit of language. Uniting meaning and

form, it is composed of one or more morphemes, each consisting of one

or more spoken sounds or their written representation. Morphemes as

we have already said are also meaningful units but they cannot be

used independently, they are always parts of words whereas words can

be used as a complete utterance (e. g. Listen!).

The

combinations of morphemes within words are subject to certain linking

conditions. When a derivational affix is added a new word is formed,

thus, listen

and

listener

are

different words. In fulfilling different grammatical functions words

may take functional affixes: listen

and

listened

are

different forms of the same word. Different forms of the same word

can be also built analytically with the help of auxiliaries. E.g.:

The

world should listen then as I am listening now (Shelley).

When

used in sentences together with other words they

are syntactically organised.

Their freedom of entering into syntactic constructions is limited by

many factors, rules and constraints (e. g.: They

told me this story but

not *They

spoke me this story).

The

definition of every basic notion is a very hard task: the definition

of a word is one of the most difficult in linguistics because the

simplest word has many different aspects. It has a sound form because

it is a certain arrangement of phonemes; it has its morphological

structure, being also a certain arrangement of morphemes; when used

in actual speech, it may occur in different word forms, different

syntactic functions and signal various meanings. Being the central

element of any language system, the word is a sort of focus for the

problems of phonology, lexicology, syntax, morphology and also for

some other sciences that have to deal with language and speech, such

as philosophy and psychology, and probably quite a few other branches

of knowledge. All attempts to characterise the word are necessarily

specific for each domain of science and are therefore considered

one-sided by the representatives of all the other domains and

criticised for incompleteness. The variants of definitions were so

numerous that some authors (A. Rossetti, D.N. Shmelev) collecting

them produced works of impressive scope and bulk.

A

few examples will suffice to show that any definition is conditioned

by the aims and interests of its author.

Thomas

Hobbes (1588-1679),

one

of the great English philosophers, revealed a materialistic approach

to the problem of nomination when he wrote that words are not mere

sounds but names of matter. Three centuries later the great Russian

physiologist I.P. Pavlov (1849-1936)

examined

the word in connection with his studies of the second signal system,

and defined it as a universal signal that can substitute any other

signal from the environment in evoking a response in a human

organism. One of the latest developments of science and engineering

is machine translation. It also deals with words and requires a

rigorous definition for them. It runs as follows: a word is a

sequence of graphemes which can occur between spaces, or the

representation of such a sequence on morphemic level.

Within

the scope of linguistics the word has been defined syntactically,

semantically, phonologically and by combining various approaches.

It

has been syntactically defined for instance as “the minimum

sentence” by H. Sweet and much later by L. Bloomfield as “a

minimum free form”. This last definition, although structural in

orientation, may be said to be, to a certain degree, equivalent to

Sweet’s, as practically it amounts to the same thing: free forms

are later defined as “forms which occur as sentences”.

E.

Sapir takes into consideration the syntactic and semantic aspects

when he calls the word “one of the smallest completely satisfying

bits of isolated ‘meaning’, into which the sentence resolves

itself”. Sapir also points out one more, very important

characteristic of the word, its indivisibility:

“It cannot be cut into without a disturbance of meaning, one or two

other or both of the several parts remaining as a helpless waif on

our hands”. The essence of indivisibility will be clear from a

comparison of the article a

and

the prefix a-

in

a

lion and

alive.

A lion is

a word-group because we can separate its elements and insert other

words between them: a

living lion, a dead lion. Alive is

a word: it is indivisible, i.e. structurally impermeable: nothing can

be inserted between its elements. The morpheme a-

is

not free, is not a word. The situation becomes more complicated if we

cannot be guided by solid spelling.’ “The Oxford English

Dictionary», for instance, does not include the

reciprocal pronouns each

other and

one

another under

separate headings, although

they should certainly be analysed as word-units, not as word-groups

since they have become indivisible: we now say with

each other and

with

one another instead

of the older forms one

with another or

each

with the other.1

Altogether

is

one word according to its spelling, but how is one to treat all

right, which

is rather a similar combination?

When

discussing the internal cohesion of the word the English linguist

John Lyons points out that it should be discussed in terms of two

criteria “positional

mobility”

and

“uninterruptability”.

To illustrate the first he segments into morphemes the following

sentence:

the

—

boy

—

s

—

walk

—

ed

—

slow

—

ly

—

up

—

the

—

hill

The

sentence may be regarded as a sequence of ten morphemes, which occur

in a particular order relative to one another. There are several

possible changes in this order which yield an acceptable English

sentence:

slow

—

ly

—

the

—

boy

—

s

—

walk

—

ed

—

up

—

the

—

hill

up —

the

—

hill

—

slow

—

ly

—

walk

—

ed

—

the

—

boy

—

s

Yet

under all the permutations certain groups of morphemes behave as

‘blocks’ —

they

occur always together, and in the same order relative to one another.

There is no possibility of the sequence s

—

the

—

boy,

ly —

slow,

ed —

walk.

“One

of the characteristics of the word is that it tends to be internally

stable (in terms of the order of the component morphemes), but

positionally mobile (permutable with other words in the same

sentence)”.2

A

purely semantic treatment will be found in Stephen Ullmann’s

explanation: with him connected discourse, if analysed from the

semantic point of view, “will fall into a certain number of

meaningful segments which are ultimately composed of meaningful

units. These meaningful units are called words.»3

The

semantic-phonological approach may be illustrated by A.H.Gardiner’s

definition: “A word is an articulate sound-symbol in its aspect of

denoting something which is spoken about.»4

The

eminent French linguist A. Meillet (1866-1936)

combines

the semantic, phonological and grammatical criteria and advances a

formula which underlies many subsequent definitions, both abroad and

in our country, including the one given in the beginning of this

book: “A word is defined by the association of a particular meaning

with a particular group of sounds capable of a particular grammatical

employment.»1

This

definition does not permit us to distinguish words from phrases

because not only child,

but

a

pretty child as

well are combinations of a particular group of sounds with a

particular meaning capable of a particular grammatical employment.

We

can, nevertheless, accept this formula with some modifications,

adding that a word is the smallest significant unit of a given

language capable of functioning alone and characterised by positional

mobility

within

a sentence, morphological

uninterruptability

and semantic

integrity.2

All these criteria are necessary because they permit us to create a

basis for the oppositions between the word and the phrase, the word

and the phoneme, and the word and the morpheme: their common feature

is that they are all units of the language, their difference lies in

the fact that the phoneme is not significant, and a morpheme cannot

be used as a complete utterance.

Another

reason for this supplement is the widespread scepticism concerning

the subject. It has even become a debatable point whether a word is a

linguistic unit and not an arbitrary segment of speech. This opinion

is put forth by S. Potter, who writes that “unlike a phoneme or a

syllable, a word is not a linguistic unit at all.»3

He calls it a conventional and arbitrary segment of utterance, and

finally adopts the already mentioned

definition of L. Bloomfield. This position is, however, as

we have already mentioned, untenable, and in fact S. Potter himself

makes ample use of the word as a unit in his linguistic analysis.

The

weak point of all the above definitions is that they do not establish

the relationship between language and thought, which is formulated if

we treat the word as a dialectical unity of form and content, in

which the form is the spoken or written expression which calls up a

specific meaning, whereas the content is the meaning rendering the

emotion or the concept in the mind of the speaker which he intends to

convey to his listener.

Summing

up our review of different definitions, we come to the conclusion

that they are bound to be strongly dependent upon the line of

approach, the aim the scholar has in view. For a comprehensive word

theory, therefore, a description seems more appropriate than a

definition.

The

problem of creating a word theory based upon the materialistic

understanding of the relationship between word and thought on the one

hand, and language and society, on the other, has been one of the

most discussed for many years. The efforts of many eminent scholars

such as V.V. Vinogradov, A. I. Smirnitsky, O.S. Akhmanova, M.D.

Stepanova, A.A. Ufimtseva —

to

name but a few, resulted in throwing light

on

this problem and achieved a clear presentation of the word as a basic

unit of the language. The main points may now be summarised.

The

word

is the

fundamental

unit

of language.

It is a dialectical

unity

of form

and

content.

Its content or meaning is not identical to notion, but it may reflect

human notions, and in this sense may be considered as the form of

their existence. Concepts fixed in the meaning of words are formed as

generalised and approximately correct reflections of reality,

therefore in signifying them words reflect reality in their content.

The

acoustic aspect of the word serves to name objects of reality, not to

reflect them. In this sense the word may be regarded as a sign. This

sign, however, is not arbitrary but motivated by the whole process of

its development. That is to say, when a word first comes into

existence it is built out of the elements already available in the

language and according to the existing patterns.

The

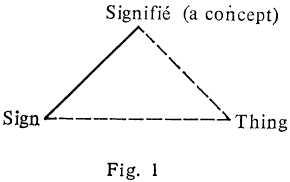

account of meaning given by Ferdinand de Saussure implies the

definition of a word as a linguistic sign. He calls it ‘signifiant’

(signifier) and what it refers to —

‘signifie’

(that which is signified). By the latter term he understands not the

phenomena of the real world but the ‘concept’ in the speaker’s

and listener’s mind. The situation may be represented by a triangle

(see Fig. 1).

-

Motivation

as a language universal. Types of motivation.

The

term motivation

is used to denote the relationship existing between the phonemic or

morphemic composition and structural pattern of the word on the one

hand, and its meaning on the other. There are three main types of

motivation: phonetical

motivation,

morphological

motivation,

and

semantic

motivation.

When

there is a certain similarity between the sounds that make up the

word and those referred to by the sense, the motivation

is phonetical.

Examples

are: bang,

buzz, cuckoo, giggle, gurgle, hiss, purr, whistle,

etc.

Here the sounds of a word are imitative of sounds in nature because

what is referred to is a sound or at least, produces a characteristic

sound (cuckoo).

Although

there exists a certain arbitrary element in the resulting phonemic

shape of the word, one can see that this type of motivation is

determined by the phonological system of each language as shown by

the difference of echo-words for the same concept in different

languages.

Within

the English vocabulary there are different words, all sound

imitative, meaning ‘quick, foolish, indistinct talk’: babble,

chatter, gabble, prattle. In

this last group echoic creations combine phonological and

morphological motivation because they contain verbal suffixes -le

and

-er

forming

frequentative verbs. We see therefore that one word may combine

different types of motivation.

Words

denoting noises produced by animals are mostly sound imitative. In

English they are motivated only phonetically so that nouns and verbs

are exactly the same. In Russian the motivation combines phonetical

and morphological motivation. The Russian words блеять

v

and блеяние

n

are equally represented in English by bleat.

Сf.

also: purr

(of

a cat), moo

(of

a cow), crow

(of

a cock), bark

(of

a dog), neigh

(of

a horse) and their Russian equivalents.

The

morphological

motivation

may be quite regular. Thus,

the prefix ex-

means

‘former’ when added to human nouns: ex-filmstar,

ex-president, ex-wife. Alongside

with these cases there is a more general use of ex-:

in

borrowed words it is unstressed and motivation is faded (expect,

export, etc.).

The

derived word re-think

is

motivated inasmuch as its morphological structure suggests the idea

of thinking again. Re-

is

one of the most common prefixes of the English language, it means

‘again’ and ‘back’ and is added to verbal stems or abstract

deverbal noun stems, as in rebuild,

reclaim, resell, resettlement. Here

again these newer formations should be compared with older borrowings

from Latin and French where re-

is

now unstressed, and the motivation faded. Compare re-cover

‘cover

again’ and recover

‘get

better’. In short: morphological motivation is especially obvious

in newly coined words, or at least words created in the present

century. Сf.

detainee,

manoeuvrable, prefabricated, racialist, self-propelling, vitaminise,

etc.

In older words, root words and morphemes motivation is established

etymologically, if at all.

From

the examples given above it is clear that motivation is the way in

which a given meaning is represented in the word. It reflects the

type of nomination process chosen by the creator of the new word.

Some scholars of the past used to call the phenomenon the inner

word

form.

In

deciding whether a word of long standing in the language is

morphologically motivated according to present-day patterns or not,

one should be very careful. Similarity in sound form does not always

correspond to similarity in morphological pattern. Agential suffix

-er

is

affixable to any verb, so that V+-er

means

‘one who V-s’ or ‘something that V-s’: writer,

receiver, bomber, rocker, knocker. Yet,

although the verb numb

exists

in English, number

is

not ‘one who numbs’ but is derived from OFr nombre

borrowed

into English and completely assimilated.

The

cases of regular morphological motivation outnumber irregularities,

and yet one must remember the principle of “fuzzy sets” in coming

across the word smoker

with

its variants: ‘one who smokes tobacco’ and ‘a railway car in

which passengers may smoke’.

Many

writers nowadays instead of the term morphological

motivation,

or

parallel to it,

introduce the term word-building

meaning.

In what follows the term will be avoided because actually it is not

meaning that is dealt with in this concept, but the form of

presentation.

The

third type of motivation is called semantic

motivation.

It is based on the co-existence of direct and figurative meanings of

the same word within the same synchronous system. Mouth

continues

to denote a part of the human face, and at the same time it can

metaphorically apply to any opening or outlet: the

mouth of a river, of a cave, of a furnace. Jacket is

a short coat and also a protective cover for a book, a phonograph

record or an electric wire. Ermine

is

not only the name of a small animal, but also of its fur, and the

office and rank of an English judge because in England ermine was

worn by judges in court. In their direct meaning neither mouth

nor

ermine

is

motivated.

As

to compounds, their motivation is morphological if the meaning of the

whole is based on the direct meaning of the components, and semantic

if the combination of components is used figuratively. Thus, eyewash

‘a

lotion for the eyes’ or headache

‘pain

in the head’, or watchdog

‘a

dog kept for watching property’ are all morphologically motivated.

If, on the other hand, they are used metaphorically as ‘something

said or done

to deceive a person so that he thinks that what he sees is good,

though in

fact it is not’, ‘anything or anyone very annoying’ and ‘a

watchful human guardian’, respectively, then the motivation is

semantic. Compare also heart-breaking,

time-server, lick-spittle, sky-jack v.

An

interesting example of complex morpho-semantic motivation passing

through several stages in its history is the word teenager

‘a

person in his or her teens’. The motivation may be historically

traced as follows: the inflected form of the numeral ten

produced

the suffix -teen.

The

suffix later produces a stem with a metonymical meaning (semantic

motivation), receives the plural ending -s,

and then produces a new noun teens

‘the

years of a person’s life of which the numbers end in -teen,

namely

from 13

to

19’.

In

combination with age

or

aged

the

adjectives teen-age

and

teen-aged

are

coined, as in teen-age

boy, teen-age fashions. A

morphologically motivated noun teenager

is

then formed with the help of the suffix -er

which

is often added to compounds or noun phrases producing personal names

according to the pattern *one connected with…’.

The

pattern is frequent enough. One must keep in mind, however, that not

all words with a similar morphemic composition will have the same

derivational history and denote human beings. E. g. first-nighter

and

honeymooner

are

personal nouns, but two-seater

is

‘a car or an aeroplane seating two persons’, back-hander

is

‘a back-hand stroke in tennis’ and three-decker

‘a

sandwich made of three pieces of bread with two layers of filling’.

When

the connection between the meaning of the word and its form is

conventional that is there is no perceptible reason for the word

having this particular phonemic and morphemic composition, the word

is said to be non-motivated

for the present stage of language development.

Every

vocabulary is in a state of constant development. Words that seem

non-motivated at present may have lost their motivation. The verb

earn

does

not suggest at present any necessary connection with agriculture. The

connection of form and meaning seems purely conventional. Historical

analysis shows, however, that it is derived from OE (ze-)earnian

‘to

harvest’. In Modern English this connection no longer exists and

earn

is

now a non-motivated word. Complex morphological structures tend to

unite and become indivisible units, as St. Ullmann demonstrates

tracing the history of not

which

is a reduced form of nought

from

OE nowiht1

<no-wiht

‘nothing’.

When

some people recognise the motivation, whereas others do not,

motivation is said to be faded.

Sometimes

in an attempt to find motivation for a borrowed word the speakers

change its form so as to give it a connection with some well-known

word. These cases of mistaken motivation received the name

of folk

etymology.

The phenomenon is not very frequent. Two

examples will suffice: A

nightmare is

not ‘a she-horse that appears at night’ but ‘a terrifying dream

personified in folklore as a female monster’. (OE таrа

‘an

evil spirit’.) The international radio-telephone signal may-day

corresponding

to the telegraphic SOS used by aeroplanes and ships in distress has

nothing to do with the First of May but is a phonetic rendering of

French m’aidez

‘help

me’.

+

Some linguists consider one more type of motivation closely akin to

the imitative forms, namely sound

symbolism.

Some words are supposed to illustrate the meaning more immediately

than do ordinary words. As the same combinations of sounds are used

in many semantically similar words, they become more closely

associated with the meaning. Examples are: flap,

flip, flop, flitter, flimmer, flicker, flutter, flash, flush, flare;

glare, glitter, glow, gloat, glimmer; sleet, slime, slush, where

fl-

is

associated with quick movement, gl-

with

light and fire, sl-

with

mud.

This

sound symbolism phenomenon is not studied enough so far, so that it

is difficult to say to what extent it is valid. There are, for

example, many English words, containing the initial fl-

but

not associated with quick or any other movement: flat,

floor, flour, flower. There

is also nothing muddy in the referents of sleep

or

slender.

To

sum up this discussion of motivation: there are processes in the

vocabulary that compel us to modify the Saussurian principle

according to which linguistic units are independent of the substance

in which they are realised and their associations is a matter of

arbitrary convention. It is already not true for phonetic motivation

and only partly true for all other types. In the process of

vocabulary development, and we witness everyday its intensity, a

speaker of a language creates new words and is understood because the

vocabulary system possesses established associations of form and

meaning.

5.

There

are broadly speaking two schools to

Meaning

of thought in present-day linguistics representing the main lines

of

contemporary thinking on the problem: the referential approach, which

seeks

to formulate the essence of meaning by establishing the

interdependence

between

words and the things or concepts they denote, and the

functional

approach, which studies the functions of a word in speech and

is

less concerned with what meaning is than with how it works.

The

criticism of the referential theories of meaning may be briefly

summarised

as follows:

1.

Meaning, as understood in the referential approach, comprises the

interrelation

of linguistic signs with categories and phenomena outside the

scope

of language. As neither referents (i.e. actual things,

phenomenaeither to the study of the interrelation of the linguistic

sign and referent or

that

of the linguistic sign and concept, all of which, properly speaking,

is

not

the object of linguistic study.

2.

The great stumbling block in referential theories of meaning has

always

been

that they operate with subjective and intangible mental processes.

The

results of semantic investigation therefore depend to a certain

extent

on “the feel of the language” and cannot be verified by another

investigator

analysing

the same linguistic data. It follows that semasiology

has

to rely too much on linguistic intuition and unlike other fields of

linguistic

inquiry

(e.g. phonetics, history of language) does not possess objective

methods

of investigation. Consequently it is argued, linguists

should

either give up the study of meaning and the attempts to define

meaning

altogether, or confine their efforts to the investigation of the

function

of linguistic signs in speech.

Functional

Approach to Meaning

The

functional approach maintains

that

the meaning of a linguistic unit may be studied only through its

relation

to other linguistic-units and not through its relation to either

concept

or

referent. In a very simplified form this view may be illustrated by

the

following: we know, for instance, that the meaning of the two words

move

and

movement

is

different because they function in speech differently.

Comparing

the contexts in which we find these words we cannot fail

to

observe that they occupy different positions in relation to other

words.

(To)

move, e.g.,

can be followed by a noun (move

the

chair), preceded by

a

pronoun (we move),

etc.

The position occupied by the word movement

is

different: it may be followed by a preposition (movement

of

smth),

preceded

by

an adjective (slow movement),

and

so on. As the distribution l

of

the

two words is different, we are entitled to the conclusion that not

only

do

they belong to different classes of words, but that their meanings

are

different

too.

The

same is true of the different meanings of one and the same word.

Analysing

the function of a word in linguistic contexts and comparing

these

contexts, we conclude that; meanings are different (or the same) and

this

fact can be proved by an objective investigation of linguistic data.

Grammatical

Meaning

We

notice, e.g., that word-forms, such as girls,

winters,

joys, tables, etc.

though denoting

widely

different objects of reality have something in common. This

common

element is the grammatical meaning of plurality which can be

found

in all of them.

Thus

grammatical meaning may be defined ,as the component of meaning

recurrent

in identical sets of individual forms of different words, as, e.g.,

the

tense meaning in the word-forms of verbs (asked,

thought, walked,

etc.)

or the case meaning in the word-forms of various nouns (girl’s,

boy’s,

night’s, etc.).

Lexical

Meaning

Thus,

e.g. the word-forms go,

goes, went, going, gone

possess

different grammatical meanings of tense, person and so on, but in

each

of these forms we find one and the same semantic component denoting

the

process of movement. This is the lexical meaning of the word

which

may be described as the component of meaning proper to the word

as

a linguistic unit, i.e. recurrent in all the forms of this word.

The

difference between the lexical and the grammatical components of

meaning

is not to be sought in the difference of the concepts underlying

the

two types of meaning, but rather in the way they are conveyed. The

concept

of plurality, e.g., may be expressed by the lexical meaning of the

world

plurality;

it

may also be expressed in the forms of various words

irrespective

of their lexical meaning, e.g. boys,

girls, joys, etc.

The concept

of

relation may be expressed by the lexical meaning of the word relation

and

also by any of the prepositions, e.g. in,

on, behind, etc.

(cf.

the

book

is in/on,

behind the

table). “

Parf-of-Speech

Meaning(lex-gram)

It

is usual to classify lexical items into major

word-classes

(nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs)

and

minor word-classes (articles, prepositions, conjunctions, etc.).

All

members of a major word-class share a distinguishing semantic

component

which though very abstract may be viewed as the lexical component

of

part-of-speech meaning. For example, the meaning of ‘thingness’

or

substantiality may be found in all the nouns e.g. table,

love,

sugar,

though

they possess different grammatical meanings of number,

case,

etc. It should be noted, however, that the grammatical aspect of the

part-of-speech

meanings is conveyed as a rule by a set of forms. If we describe

the

word as a noun we mean to say that it is bound to possess a set of

forms expressing the grammatical meaning of number (cf. table—

tables), case

(cf. boy,

boy’s) and

so on. A verb is understood to possesssets of forms expressing, e.g.,

tense meaning (worked

— works), mood

meaning (work!

— (I) work), etc.

The

part-of-speech meaning of the words that possess only one form,

e.g.

prepositions, some adverbs, etc., is observed only in their

distribution

(cf.

to

come in (here, there) and

in

(on, under) the

table).

Denotational

and

Connotational Meaning

Proceeding

with the semantic analysis we

observe

that lexical meaning is not homogenous

either

and may be analysed as including denotational and connotational

components.

As

was mentioned above one of the functions of words is to denote

things,

concepts and so on. Users of a language cannot have any knowledge

or

thought of the objects or phenomena of the real world around them

unless

this knowledge is ultimately embodied in words which have essentially

the

same meaning for all speakers of that language. This is the d e —

n

o t a t i o n a l m e a n i n g , i.e. that component of the lexical

meaning

which

makes communication possible. There is no doubt that a

physicist

knows

more about the atom than a singer does, or that an arctic explorer

possesses

a much deeper knowledge of what arctic ice is like than a

man

who has never been in the North. Nevertheless they use the words

atom,

Arctic, etc.

and understand each other.

The

second component of the lexical meaning is the c o n n o t a —

t

i o n a l c o m p o n e n t , i.e. the emotive charge and the

stylistic

value

of the word.

Emotive

Charge

Words

contain an element of emotive evaluation as part of the connotational

meaning;

e.g. a

hovel denotes

‘a small house or cottage’ and besides

implies

that it is a miserable dwelling place, dirty, in bad repair and in

general

unpleasant to live in. When examining synonyms large,

big, tremendous

and

like,

love, worship or

words such as girl,

girlie; dear,

dearie

we

cannot fail to observe the difference in the emotive charge of

the

members of these sets. The emotive charge of the words tremendous,

worship

and

girlie

is

heavier than that of the words large,

like and

girl.

This

does not depend on the “feeling” of the individual speaker but is

true

for

all speakers of English. The emotive charge varies in different

wordclasses.

In

some of them, in interjections, e.g., the emotive element prevails,

whereas

in conjunctions the emotive charge is as a rule practically

non-existent.

Sfylistic

Reference

Words

differ not only in their emotive charge but

also

in their stylistic reference. Stylistically words

can

be roughly subdivided into literary, neutral and colloquial layers.1

The

greater part of the l i t e r а

r у

l a y e r of Modern English vocabulary

are

words of general use, possessing no specific stylistic reference

and

known as n e u t r a l w o r d s . Against

the background of

neutral

words we can distinguish two major subgroups — st a n d a r d

c

o l l o q u i a l words and l i t e r a r y or b o o k i s h words.

This

may be best illustrated by comparing words almost identical in their

denotational

meaning, e. g., ‘parent

— father — dad’.

etc.

The colloquial words may be subdivided into:

1)

Common colloquial words.

2)

Slang, i.e. words which are often regarded as a violation of the

norms

of Standard English, e.g. governor

for

‘father’, missus

for

‘wife’, a

gag

for

‘a joke’, dotty

for

‘insane’.

3)

Professionalisms, i.e. words used in narrow groups bound by the

same

occupation, such as, e.g., lab

for

‘laboratory’, hypo

for

‘hypodermic

syringe’,

a

buster for

‘a bomb’, etc.

4)

Jargonisms, i.e. words marked by their use within a particular social

group

and bearing a secret and cryptic character, e.g. a

sucker —

‘a person

who

is easily deceived’, a

squiffer —

‘a concertina’.

5)

Vulgarisms, i.e. coarse words that are not generally used in public,

e.g.

bloody,

hell, damn, shut up, etc.

6)

Dialectical words, e.g. lass,

kirk, etc.

7)

Colloquial coinages, e.g. newspaperdom,

allrightnik, etc.

Emotive

Charge and

Stylistic

Reference

Stylistic

reference and emotive charge of

words

are closely connected and to a certain

degree

interdependent.1 As a rule stylistically

coloured

words, i.e. words belonging to all stylistic layers except the

neutral

style

are observed to possess a considerable emotive charge. That can

be

proved by comparing stylistically labelled words with their neutral

synonyms.

The colloquial words daddy,

mammy are

more emotional than

the

neutral father,

mother; the

slang words mum,

bob are

undoubtedly

more

expressive than their neutral counterparts silent,

shilling, the

poetic

yon

and

steed

carry

a noticeably heavier emotive charge than their neutral

synonyms

there

and

horse.

Words

of neutral style, however, may also

differ

in the degree of emotive charge. We see, e.g., that the words large,

big,

tremendous, though

equally neutral as to their stylistic reference are

not

identical as far as their emotive charge is concerned.

7.-8.

Nature

of Semantic

Chang

There

are two kinds of association

involved

as a rule in various semantic changes namely: a) similarity of

meanings,

and b) contiguity of meanings.

S

i m i l a r i t y of m e a n i n g s or metaphor may be described

as

a semantic process of associating two referents, one of which in some

way

resembles the other. The word hand,

e.g.,

acquired in the 16th century

the

meaning of ‘a pointer of a clock of a watch’ because of the

similarity

of

one of the functions performed by the hand (to point at something)

and

the function of the clockpointer. Since metaphor is based on the

perception

of similarities it is only natural that when an analogy is obvious,

it

should give rise to a metaphoric meaning. This can be observed in