Skip to content

Word and Phrase, a corpus-based resource created by Mark Davies of Brigham Young University, has been retired in Fall 2021. Its disappearance is not a complete surprise, as the site announced in 2020 that the resource would be phased out by or during 2021. The corpus had been helpful for exploring the specific ways in which writers had previously used language. It was particularly useful for investigating collocations, words that are often used together. Thank you and farewell, Word and Phrase! You will be missed.

The good news is that searching COCA in the Word search mode provides similar support for the same 60,000 words (or lemmas) covered by the Word and Phrase corpus. In some ways, COCA offers more support for those words, but (not surprisingly) if you frequently used Word and Phrase, you might notice aspects of that resource that are missing from a COCA search in Word mode.

Consider visiting the COCA resource, which Word and Phrase was derived from, and registering for that. Registration is free. Watching our fifth COCA screencast, near the bottom of the page here, will guide you to understand where and how you can access word use information (e.g., collocates, clusters of words, and sample sentences or excerpts) on the same words that were included in the Word and Phrase corpus.

Naturally, we’ve removed the Word and Phrase screencasts that were available here. But we’ll leave this page visible, because writers, students, and perhaps corpus linguists might be given a link to this page for some time to come.

Above guide and screencast tutorials developed by Rene D. Caputo

Brought to you by the Duke University Thompson Writing Program

The Word and Phrase Tool: Vocabulary and Writing in Academia

By Devin, a Writing Coach

Update: Since the time of publishing, the Word and Phrase Tool has been integrated into the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). For tips on using the COCA for word choice, check out our recent blog post Mastering Word Choice with the Corpus of Contemporary American English.

The Word and Phrase Tool is a resource that I use to answer questions about my language use. How is this word usually used in a sentence? Does this sound right? Is this formal enough? All of these come to mind as I write. While a dictionary or a thesaurus can help me research these questions, I sometimes want a collection of real examples of the way language is used in real sentences. That language resource exists: it’s called a corpus.

Corpora and the Word and Phrase Tool

A corpus is a collection of language examples. The one I’ll look at today–the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA)–was created by Professor Mark Davies. It contains more than 1 billion words, in nearly a half-million texts, evenly divided across six genres (TV/movie subtitles, spoken, fiction, popular magazines, newspapers, and academic journals) to give writers a sense of how specific word usages vary in different contexts. The corpus even details how language use differs between different academic disciplines.

In 2012, Prof. Davies released the Word and Phrase Tool, which allows users to perform queries within the COCA using a web interface. The tool is a free, powerful, and simple language tool that I think should be in every writer’s repertoire. That said, the website itself has a bit of a learning curve. I’ll admit that it can be intimidating at first. But, as I worked through some of the examples below, I gradually familiarized myself with the tool and its functions.

Using the Word and Phrase Tool

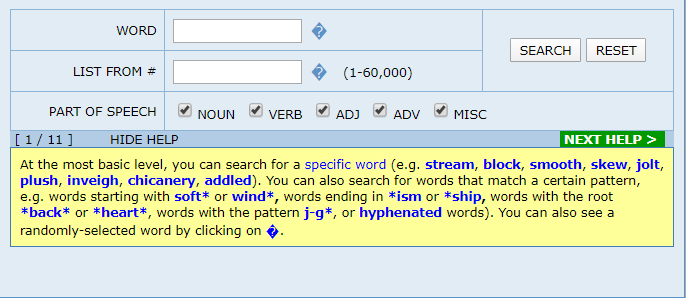

To access the Word and Phrase Tool, I went to https://www.wordandphrase.info/old/. The tool offers two main functions. The first function, the frequency list, lets me search for usage information about particular words. The second function, input/analyze texts, uploads phrases or larger blocks of text to analyze how our language use compares to examples in the corpus. For today, I’m just going to focus on the first function, so I clicked on the “Frequency list” link and looked at the search bar in the upper-left part of the screen.

Searching for a word and interpreting results

I’m looking for a synonym of “praise” because I’ve been repeating it in an academic paper about a performance I saw earlier this semester at Memorial Hall. To spice up my language, I’ve consulted a thesaurus for synonyms for praise, and I found the word “lionize.” So, I type “lionize” into the WORD box and click search. The page returns a LOT of information all at once. Too much information, in fact. I need to go through it bit by bit.

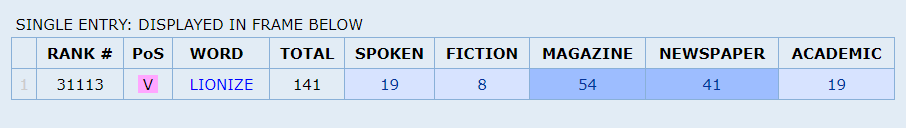

The area to the right of the search box gives information about the word “lionize.” “RANK #” ranks the word within the top 60,000 most frequently-used words in the entire corpus. Words with low ranks are more commonly used than words with higher ranks. “PoS” means part of speech; lionize is listed as “V” for verb. Many words in English belong to multiple parts of speech. If I search for a word that has multiple entries in the upper-right part of the screen, I just click on the “PoS” value (in this example, the purple “V”) to select only a particular form of the word. “TOTAL” indicates the number of times “lionize” appears in the entire corpus, followed by subtotals in each genre. OK, after figuring out all these parts, the corpus is starting to make sense to me.

As it turns out, the frequency information is also shown in a bar graph near the middle of the screen. From this bar, I can see that academic writers seldom use the term “lionize,” but non-academic writers–those who write magazine articles and newspaper articles– seem to like the word. It’s probably not the best choice for my academic paper, but I’ll look at the definition to the right of the bar graph to be sure. “Assign great social importance” isn’t the kind of “praise” I had in mind, so “lionize” is definitely not the synonym I want.

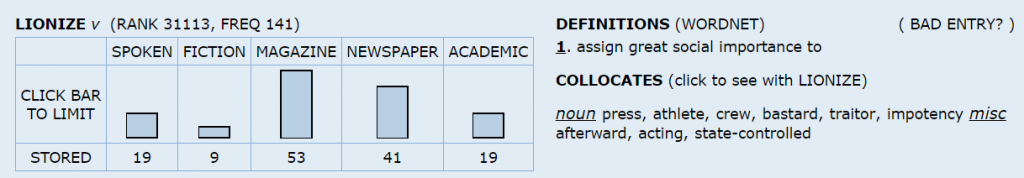

After deciding against “lionize,” I go back to the thesaurus. This time, I choose “laud” from the list, look it up in the dictionary, and discover it means “to praise” – great! Just to make sure that “laud” is appropriate for my paper, I also decide to search for the word in the Word and Phrase Tool.

Although laud is most frequently used in newspapers, it certainly appears in academic writing, too. Also, this definition of “laud” is exactly what I’m looking for, so this seems like a great word for the performance review! But how do I use it in a sentence? Thankfully, collocates can help.

Using collocates to learn how to use a word in a sentence

Look just below the definition of “laud” at the “COLLOCATES” section. Collocates are words that frequently appear together, and this feature can help me find natural sounding combinations for my new word. The paper I’m writing is about a performance I’ve recently seen, and performance just happens to be in the list of words that commonly appear with “laud.”

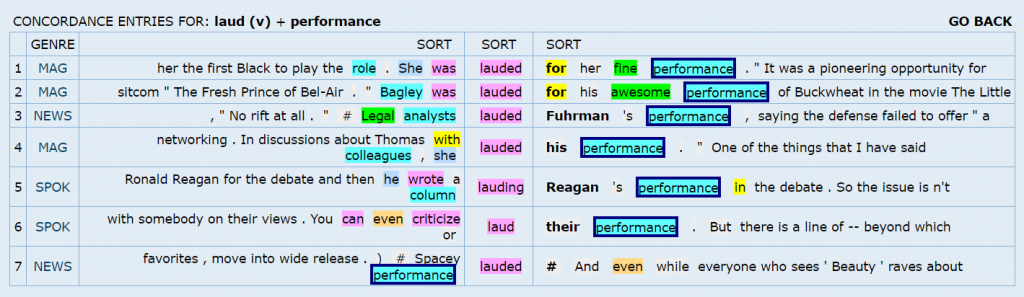

When I click on “performance” from this list, the bottom part of the screen changes to provide a list of all the sentences in the corpus that contain both “performance” and “laud” close to one another in the sentence. After analyzing the examples, I see that both performers and their performances are lauded, and that someone is lauded for something.

Disciplinary differences in word use

So far, we’ve been exploring the frequency list to see how a word’s use can change across the entire corpus, including academic and non-academic contexts. For other projects, sometimes I like to explore how a word is used in different disciplines within academic writing. To do so, I click the ACADEMIC button at the very top of the page, underneath “INFO” in the page title. This part of the page functions identically to what we’ve already seen, except the results are broken down by academic discipline. With this function, I can get a sense of how to use a word in political science for one paper and art history for the next!

Understanding the meaning of no results

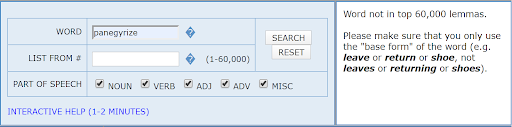

Now I’m going to head back to the Word and Phrase Tool’s homepage to search for another synonym for praise: “panegyrize”. That word isn’t used very frequently at all, which results in the blank results screen shown below. That’s important information because it might indicate that the word is archaic or obsolete. It’s probably best to avoid archaic or obsolete language (like panegyrize), as this sort of language will only impede my readers’ understanding.

On the other hand, finding no results in the COCA does not automatically mean I shouldn’t use the word at all. Many words used by academics are highly specialized and may not appear in the top 60,000 words in the corpus, even if they’re in use. If my search results come back with nothing and I think it’s because the word is specialized language, I verify my suspicion by doing a keyword search through some documents that use the appropriate specialized language (such as journal articles). I may be building my academic vocabulary by using unfamiliar words, but I need to make sure the words aren’t so unusual that my readers don’t know what I’m talking about.

One extra tip for interpreting a “no results” for a word search is to remember that the Word and Phrase Tool only works for word roots. For example, even though “praise” appears in the corpus, “praised” does not. If I find that a seemingly common word isn’t in the corpus, I pop it into a dictionary to see if it has a root form.

Not too much at one time

The Word and Phrase Tool is an incredibly powerful language resource, but it isn’t necessary to use the tool’s advanced capacities for it to be helpful. I find the frequencies, definitions, and collocates most helpful in my writing right now. As I continue to use these and other functions, I get a better sense of what works best for me.

This blog showcases the perspectives of UNC Chapel Hill community members learning and writing online. If you want to talk to a Writing and Learning Center coach about implementing strategies described in the blog, make an appointment with a writing coach or an academic coach today. Have an idea for a blog post about how you are learning and writing remotely? Contact us here.

This session covers some selected useful corpora, concordance tools, and corpus tools for teachers and provides them with the skills needed to explore corpus data and discover patterns of language use.

1. The British National Corpus (BNC)

The British National Corpus (BNC) was originally created by the Oxford University Press in the 1980s –early 1990s, and it is an essential tool for linguistic data analysis. It contains 100-million-word texts of British English. It not only includes written texts but also transcriptions of spoken data. It is completely free but requires registration.

The official website: http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/

1.1 Registration

(BNC registration link)

In this short video clip, Prof. Handke explains how to create a BNC account and how to use this well-known corpus.

Linguistic Data Analysis – Using the BNC. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WaOLPEUm1oI

1.2 The BNC frequency search:

In this particular case, the “frequency-of- occurrence” analysis of words in the British National Corpus. The central research question is to generate a list of the occurrences of word-forms derived from the base GENERATE.

The BNC frequency searchs. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gpxgh34pSAI

1.3 BNC Frequency Search with POS-Tags:

How do we find all verbs that have been derived by means of en- prefixation? The use of BNC-option part-of-speech (POS)-Tag in conjunction with the frequency search is the answer which Prof. Handke discusses in this short video clip.

BNC Frequency Search with POS-Tags Tags. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hyeCAGzmrVY

2. BYU Corpora

The BYU Corpora was created by Mark Davies, Professor of Corpus Linguistics at Brigham Young University. It contains multiple corpora, which are probably the most widely-used corpora currently available– more than130,000 distinctresearchers, teachers, and students each month. There are also many corpus-based resources provided.

The official website: https://corpus.byu.edu/

3. Corpus Of Contemporary American English (COCA)

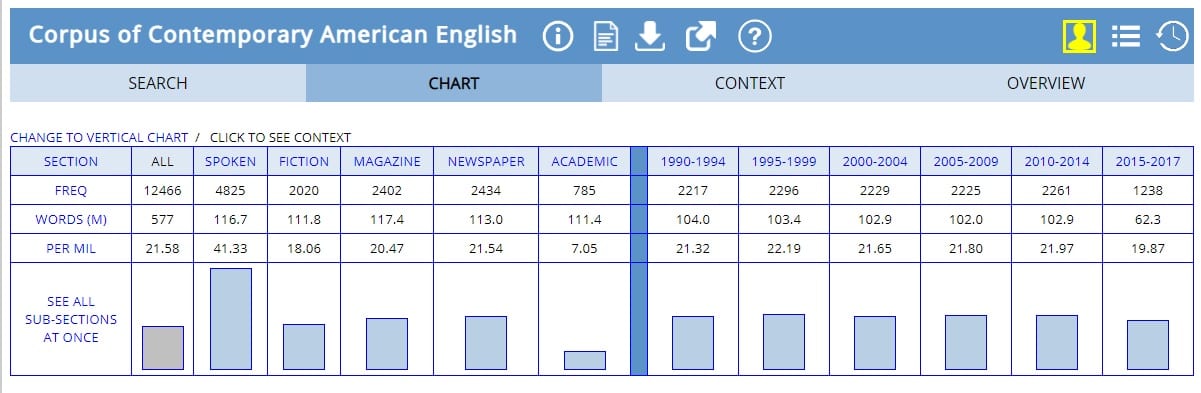

The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) was created by Mark Davies, Professor of Corpus Linguistics at Brigham Young University. It is the largest freely-available corpus of English, and the only large and balanced corpus of American English. COCA is probably the most widely-used corpus of English, and it is related to many other corpora of English that we have created, which offer unparalleled insights into variation in English. The corpus contains more than 560 million words of text (20 million words each year 1990-2017) and it is equally divided among spoken language, fiction, popular magazines, newspapers, and academic texts.

The official website: https://corpus.byu.edu/coca/

3.1 Introduction to the COCA

This is a series of short videos developed by Dr. Angel Ma from EdUHK, which introduces a variety of search functions available on the COCA website, including Basic Frequency Search, Wildcard Search, Part of speech Search, Synonym Search, Collocates, Compare and KWIC next, and the Chart function:

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLgogrye_oIvbdUzsJLwlbxsT6fsNAwt96

Gaining familiarity of these search functions could help you design vocabulary teaching and learning activities for students.

Introduction to COCA functions by Dr Angel Ma (EdUHK)

EdUHK Corpus Tutorial: Register

EdUHK Corpus Tutorial Part 1: Basic Search

EdUHK Corpus Tutorial Part 2: Wildcard Search

EdUHK Corpus Tutorial Part 3: Part of Speech

EdUHK Corpus Tutorial Part 4: Synonym

EdUHK Corpus Tutorial Part 5: Collocates

EdUHK Corpus Tutorial Part 6: Compare

EdUHK Corpus Tutorial Part 7: KWIC

EdUHK Corpus Tutorial Part 8: Chart

EdUHK Corpus Tutorial Part 9: Word

4. Word And Phrase

4.1 Introduction to Word and Phrase

The official website: https://www.wordandphrase.info/

Using Word and Phrase: Introduction. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMS-SJ0o83g

4.2 Explore collocates in Word and Phrase

This tutorial demonstrates how you can use Word and Phrase to explore collocates.

Using Word and Phrase: Exploring collocates. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7qvhGS8IDRE

4.3 Doing academic searches

This tutorial demonstrates how you can use Academic function of Word and Phrase to improve language usage.

Using Word and Phrase: Doing academic searches. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r9qe6Z11RyE

4.4 Using Word and Phrase to analyze and improve learners’ writing

This video covers the basic functions of Analyze Texts in Word and Phrase and demonstrates how this function can greatly enhance learners’ writing.

Word and Phrase. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UkZF2ql9NQI

How to register for Word and Phrase

How to use the “Text Analysis” function in Word and Phrase

5. Compleat Lexical Tutor

Compleat Lexical Tutor was developed by Tom Cobb of University of Quebec at Montreal (UQAM), aiming to provide applications for testing, improving, and researching vocabulary learning. The site provides resources not only for teaching English, but also French, German and Spanish. It also includes concordance, vocabulary profiler, exercise maker, interactive resources, and much more.

The official website: https://www.lextutor.ca/

5.1 How can we use Compleat Lexical Tutor in the classroom?

This tutorial is an introduction to Compleat Lexical Tutor covering Hypertext builder, Dictator, Interactive quiz option, Cloze builder, frequency list, frequency based vocabulary tests.

How to use the “Cloze builder” functions in Compleat Lexical tutor

Other useful tools at http://lextutor.ca–Concord Writer

5.2 Corpus Concordance English

Corpus Concordance English is a powerful and user-friendly concordancer tool in Compleat Lexical Tutor, where you can search collocations, check to see whether use of a word is appropriate. It covers various corpora for language teaching and learning at different school levels. The official website: https://www.lextutor.ca/conc/eng/

How to search words in Corpus Concordance English

How to search for “insist”

How to search the phrase “make sure”

6. AntConc

AntConc is a concordance tool for analysing electronic texts in order to discover patterns in language use. It was created by Laurence Anthony of Waseda University. It is one of the most well-designed and user-friendly corpus tools. For teachers, it is an effect way to select target words, design lessons and prepare teaching materials.

The official website: http://www.laurenceanthony.net/software/antconc/

6.1 Getting started with AntConc

This video demonstrates how to download and get started with AntConc.

AntConc 3.4.0 Tutorial 1: Getting Started. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O3ukHC3fyuc

6.2 Basic features of Concordance function in AntConc

This video shows the basic features of the AntConc concordance.

AntConc 3.4.0 Tutorial 2: Concordance Tool – Basic Features. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uAYCA8dYbr4

6.3 Advanced features of Concordance function in AntConc

This video shows the advanced features of the AntConc concordance

AntConc 3.4.0 Tutorial 3: Concordance Tool – Advanced Features. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2rvsBaM6W8Y&t=16s

Objectives: You will be able to…

- Recognize common sources of word choice

problems, such as using wrong forms (wrong spelling or part of speech),

style (informal word choice), idiomatic errors (using wrong articles or

prepositions for phrasal verbs), collocation errors - Consider various aspects of vocabulary (part

of speech, register, spelling, collocation, meaning in context, frequency,

synonymy, etc.) when choosing the “right word” to use in academic writing. - Use Google, Word and Phrase. Info, Corpus of

Contemporary American English (COCA) as

reference tools when choosing the “right word” to use in academic writing. - Recognize important considerations for

successful word search using the reference tools above

— Good for beginners (user-friendly, dictionary-like interface)

— Fewer number of words than regular COCA (only 120 out of 450 million words of texts)

— Less custom search functions available compared to the regular interface

— Only one line of a text is available to study the context

— Good for experienced users and researchers with some linguistic background knowledge

— More number of words than Word and Phrase Info

— More custom search functions, such as phrase search, customized wild card search (wild card words with certain part of speech/collocation options, collocation search, synonym search)

— Can read more than one line to study the context -> «Expanded text» function (Click either the year or the genre code to see the expanded text)

Task 3: Register for free on COCA Website and explore on your own.

Helpful Resources:

Tips for More Effective COCA Search

- For setting up a good search string, choose the right search key word (an anchor word) carefully. Not all adjacent words are relevant for a search (or interpretation of the search). E.g.) if you are looking for a content word that goes into the blank in I hope to ___?___ the goal, you should use the goal as an anchor word (the key word for search) because it determines the kind of the verb you should use in the blank. You should not use hope to as an anchor word.

- Use a search (word) string that is an appropriate size. If the search string is too short (only one or two words), it is difficult to get a reliable answer quickly. (e.g. using only «implications» as a search word to find the preposition for «implications ___ teaching ESL») If the search string is too long (too specific), it is difficult to find many matching texts. (e.g. using «implications for teaching ESL»)

- For interpreting the results, Go for MORE FREQUENTLY used phrases. «Hot debate» and «Heated debate» are both possible collocates in English, but «heated debate» is much more commonly used.

- Always check the CONTEXT and GENRE. It is often dangerous to look at only the frequency count and decide which one to use. Having a higher frequency counts does not always mean both words are possible in a given context. For example, «totally» and «fully» are considered synonyms, but only one of them is desirable in academic English. Also, «received the phone call» and «answer the phone» are both possible/frequent in English, but only one of them would work in a given context.

- If there is no or few result showing, it happened for one of the following reasons: 1) one of the words could be spelled wrong, or an ungrammatical word or 2) the word combination is impossible or rare.

Intro

425 million words from 1990-2011.

I believe that one of the best resources out there for linguists (or anyone interested in language) is the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). Mark Davies has put together a bunch of corpora and put together an easy-to-use interface so you can make sophisticated queries on vast amounts of data. It’s a lot bigger than most of the corpora you may be going to now (CELEX, Switchboard, etc). And while its sentences aren’t annotated with tree structures, it does have part-of-speech info (and makes it really easy to get collocates).

This post is really about getting started with COCA, but I’ll try to do it in the framework of a particular linguistic phenomenon. But if you get nothing out of this post but USE COCA, that’ll be enough. It also makes it easy to compare to historical American English, the BNC, and Google Books/N-gram (though I won’t be showing that here).

Wh-exclamatives

A few months ago Anna Chernilovskaya came by and presented work she and and Rick Nouwe had been doing on exclamatives like:

(1) What a beautiful song John wrote!

Their work is set against Rett (2011), which sees wh-exclamatives as being a speaker expressing something that is noteworthy in the given context–in other words, to say (1) you think there’s something noteworthy about John’s song relative to the standard beauty of songs.

If you don’t have a degree adjective like “beautiful” (instead something like What a song John wrote!), Rett says you have an operator that acts like a silent adjective, so you’re exclaiming about beauty, weirdness, or complexity. Chernilovskaya and Nouwe are saying, “Nah, it’s simpler–it’s just direct noteworthiness. Drop all this degree stuff.”

My question: how are wh-exclamatives actually used by English speakers? My intuition is with C&N that it’s just about noteworthiness. But is that all?

First steps with COCA

Go to http://corpus.byu.edu/coca/, look over to the upper right–you can log in or register, as appropriate.

Most of the action is going to be in the panel on the left. Some of the stuff is hidden to reduce complexity, so if you want to see part-of-speech tags, just click on the text that says “POS LIST” and you’ll get a drop-down menu you can choose stuff from. If you want to do collocation stuff, just click “COLLOCATES”, etc.

COCA’s left-pane

Let’s go ahead and start collecting examples of wh-exclamatives. In the “WORD(S)” text box, we could type:

what [at*]

And that would get us 82,074 sentences, including both what a and what an. It would also get us what the, what every, and what no. Including sentences like Her would-be opponents are pondering these questions and what the answers mean for their own possible candidacies.

That’s rather too much. Let’s try the following–the [y*] means “any punctuation”.

[y*] what [at*]

Now we have 18,063 sentences. This may help us see that I mean, what the heck is interesting, but perhaps it’s still taking us too far afield. Let’s just do what you are probably thinking we should’ve done from the beginning:

[y*] what a|an

8,919 results. Looking through the results, this is a pretty good query. We could restrict which punctuation we care about, but if you go ahead and do this query yourself, I think you’ll see why we want to keep most punctuation.

Search results in COCA (click to make ’em bigger)

The top right box shows all the matches lumped together by punctuation/article, click on any of them and the actual sentences will show up below. Notice the drop-down Help box on the far right above the sentences. Use that to find out more about query syntax.

Noteworthiness

Let’s see what the most common words are that go with a what a|an construction. We have a few options, we can run queries like:

what a|an [j*] [n*]

what a|an [j*]

what a|an [n*]

This third one is pretty interesting because it helps us see which sorts of exclamations are made without an adjectives. (One person in our semantics/pragmatics group confided that his father always said What a baby! when confronted by an unattractive child–there’s a pressure to exclaim something but he doesn’t want to lie, so this strategy manages to give the right form without quite meaning the meaning that the parents might take away.)

Here are the top 15, though the first one ends up not really being part of our pattern a lot of the time.

| 1 | WHAT A LOT | 507 |

| 2 | WHAT A DIFFERENCE | 321 |

| 3 | WHAT A WASTE | 187 |

| 4 | WHAT A MAN | 183 |

| 5 | WHAT A SHAME | 168 |

| 6 | WHAT A MESS | 159 |

| 7 | WHAT A PERSON | 156 |

| 8 | WHAT A RELIEF | 152 |

| 9 | WHAT A DAY | 150 |

| 10 | WHAT A SURPRISE | 142 |

| 11 | WHAT A WOMAN | 126 |

| 12 | WHAT A PLEASURE | 117 |

| 13 | WHAT A WAY | 104 |

| 14 | WHAT A STORY | 101 |

| 15 | WHAT A PITY | 95 |

And in case you were curious about the one-word exclamatives with actual exclamation marks:

what a|an [n*] !

| 1 | WHAT A MESS ! | 30 |

| 2 | WHAT A SURPRISE ! | 27 |

| 3 | WHAT A RELIEF ! | 26 |

| 4 | WHAT A SIGHT ! | 23 |

| 5 | WHAT A DAY ! | 22 |

One of the things C&N say Rett can’t handle is something like What an extremely nice man since the extremely and nice should interfere on Rett’s account. You can’t say *John is more extremely nice than Bill or *John is too extremely nice. How does this pattern work in the data?

what a|an [r*]

| 1 | WHAT A VERY | 24 |

| 2 | WHAT A TRULY | 13 |

| 3 | WHAT A REALLY | 12 |

| 4 | WHAT A GREAT | 10 |

| 5 | WHAT AN ABSOLUTELY | 9 |

| 6 | WHAT AN INCREDIBLY | 9 |

| 7 | WHAT A WONDERFULLY | 7 |

Now another way of looking at stuff is to look for collocational strength.

Getting collocation info

The important stuff here is that I clicked on “COLLOCATES” and put in the part of speech (adverb=[r*]) and chose the window I was looking at–in this case two the right. I also adjusted the “MINIMUM” to be based on mutual information and I set it to ignore things with a mutual information of less than 2 (a standard strength measure is 3.0, but I wanted to get a few more than that).

A few other things:

- You may want to restrict yourself to just SPOKEN stuff (that’s in the middle of the left-pane).

- If you have a big query you probably want to change # HITS FREQ to something big (the default is 100).

- Often it’s more useful to GROUP BY lemmas than words (though here it doesn’t matter, think about if I were doing something about verbs)

- If you choose SAVE LISTS, you’ll get prompted to enter a list name ABOVE the top results. It’s really easy to miss.

But back to the results. The adverbs with the highest mutual information are truly, incredibly, wonderfully, extraordinarily, and remarkably, though the absolute counts are pretty low. Still clicking around on examples may help.

Now if we do adjectives, we get these results:

| Num | Adj | CtTogether | AdjCt | Perc | MI |

| 1 | [GREAT] | 428 | 248,858 | 0.17 | 5.4 |

| 2 | [WONDERFUL] | 263 | 29,277 | 0.9 | 7.78 |

| 3 | [BEAUTIFUL] | 161 | 43,750 | 0.37 | 6.5 |

| 4 | [GOOD] | 133 | 409,451 | 0.03 | 2.99 |

| 5 | [LOVELY] | 102 | 10,246 | 1 | 7.93 |

| 6 | [NICE] | 100 | 50,448 | 0.2 | 5.6 |

| 7 | [TERRIBLE] | 84 | 20,290 | 0.41 | 6.67 |

| 8 | [STRANGE] | 78 | 26,432 | 0.3 | 6.18 |

| 9 | [AMAZING] | 60 | 17,204 | 0.35 | 6.42 |

| 10 | [STUPID] | 47 | 13,524 | 0.35 | 6.41 |

Notice how exclamatives skew positive. (That’s why the What a baby! trick works!)

And nouns, though let’s increase the window to 4 to the right.

| Num | Noun | CtTogether | NounCt | Perc | MI |

| 1 | [THING] | 264 | 438,956 | 0.06 | 2.88 |

| 2 | [DAY] | 242 | 486,452 | 0.05 | 2.61 |

| 3 | [IDEA] | 209 | 133,349 | 0.16 | 4.27 |

| 4 | [WAY] | 198 | 521,448 | 0.04 | 2.22 |

| 5 | [DIFFERENCE] | 195 | 89,269 | 0.22 | 4.74 |

| 6 | [WASTE] | 166 | 31,419 | 0.53 | 6.02 |

| 7 | [SURPRISE] | 165 | 35,267 | 0.47 | 5.84 |

| 8 | [MAN] | 153 | 460,880 | 0.03 | 2.03 |

| 9 | [SHAME] | 151 | 9,431 | 1.6 | 7.62 |

| 10 | [STORY] | 148 | 178,875 | 0.08 | 3.34 |

Noteworthiness?

Here is C&N’s definition of noteworthiness:

an entity is noteworthy iff its intrinsic characteristics (i.e. those char-

acteristics that are independent of the factual situation) stand out con-

siderably with respect to a comparison class of entities (C&N 2012: 5).

In the last section, we saw that what a (adj) story was a prominent use (#10). If we restrict ourselves just to the spoken portion of the corpus, this leaps up to #1. That’s because the spoken portion comes from talk shows and news programs (like Good Morning America, Dateline, and Larry King). If you look at the transcripts–and if you have ever listened to American news, you’ll know that what a (great/emotional/amazing/astonishing/inspiring) story comes up usually after the story is done and a segue is happening. And this is also true for how what a pleasure and many of the other items are. What a is used in these talk show/news programs as a way of simultaneously evaluating and moving between topics (usually out of, but also sometimes into).

All of these makes me skeptical about the definition C&N provide.

Consider this Good Morning American clip from last August (fast forward to about 56:20), where two stories, back-to-back are described in terms “what a” noteworthiness:

{Story about a woman surviving in the wilderness for 3 days}

Thank you, David.

What a story.

And what a story we have coming up for you.

{Uh, that’s about the making of a boy band.}

I would contend that these stories are not really that noteworthy (they also occur at the tail end of the show and so may be the most cuttable if things earlier had gone long). You may or may not agree with me. But at a minimum we probably need to say that such exclamatives are claims about noteworthiness, not factual observations about things that are intrinsically noteworthy. Any sort of judgment about noteworthiness has to have a judge, so that seems to be a problem for arguments about intrinsic qualities.

Part of Rett’s discussion does have the speaker in the mix (pages 4-5), but then towards the end of the paper she says of

(2) How very unexpected John’s news is!

(3) What a surprise John’s height is!

“To the extent that they sound natural, are interpreted as reflecting an objective surprise or unexpectedness rather than one oriented to the speaker” (Rett 2011: 19). Her main point is that gradable properties get their values from context–it’s not that they reflect the speaker’s attitude.

I’m a big fan of information theoretic accounts of language, which gives measures of surprise. The surprise of “x” and “y” co-occurring is based on prior probabilities of them occurring separately and together. But the truth is that they are always defined against some perceiver’s experience. Psycholinguists use corpora to estimate how surprising word y is following word x, but if some subject had a remarkably different experience with “x” and “y” than most of us, well, we’d expect effects to be different.

After looking through the actual uses of what a, I propose you HAVE to build in the speaker. And what is more, these what a sentences really are doing more than just expressing an observation of the world. More than expressing an internal state. And more than just an evaluation. They are social in their nature (what a (stupid/amazing/dumb) thing to say), so I would contend that theories should also look at consequences of the use in terms of the relationship between the speaker and their audience. My inclination is also to believe that we ought to say something about how they tend to skew positively in terms of adjectival collocates and probably how they hold that positive-skew as a default interpretation even when there’s no adjective, as in the what a baby! example.

But what a long post this is. I’ll stop.

Tags: coca, emotion, english, exclamatives, fav, pragmatics, semantics, syntax, wh-words

- The British National Corpora (BNC) is a collection of 100 million samples of written and spoken language in four domains: academic writing, imaginative writing, newspaper texts, and spontaneous conversation. The written part (90%) includes newspapers, periodicals, journals, books, letters, memoranda and essays. The spoken part (10%) includes transcriptions of informal conversations, formal meetings, and radio shows.

How to use it?

Type a word or phrase in the search box and press the Go button to see up to 50 random hits from the corpus. You can search for a single word or a phrase, restrict searches by part of speech, search in parts of the corpus only, and much more. Start using BNC now by clicking here.

The BNC has several versions (you need to apply for approval to download them) that gather several special collections: the BNC Baby edition (4 million, 1 million from each of the 4 domains), the BNC Sampler (1 million words), the BNC World Edition (second edition of 2002), and the BNC XML (full) Edition, the 2007 third edition.

- The Corpus of Global Web-based English, GloWbe (pronounced “globe”), has 1.9 billion words from 1.8 million web pages from 20 countries (nearly 20 times larger than BNC) and was released in 2013.

How to use it?

You can search words, phrases, grammatical constructions, synonyms, customized lists, and collocates (nearby words, which provide insight into meaning and usage). You can compare British and American English or limit the search to one or two countries (e.g., Australia and South Africa). Start using GloWbe now by clicking here.

- The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) is the largest freely-available corpus of English that contains more than 450 million words of text and is equally divided among spoken, fiction, popular magazines, newspapers, and academic texts. It includes 20 million words each year from 1990-2012 and the corpus is also updated regularly.

How to use it?

You can search for exact words or phrases, wildcards, lemmas, part of speech, or any combinations of these. You can search for surrounding words (collocates) within a ten-word window (e.g. all nouns somewhere near faint, all adjectives near woman, or all verbs near feelings). You can limit searches by frequency and compare the frequency of words, phrases, and grammatical constructions. Start using COCA now by clicking here.

- The Corpus of Historical American English (COHA) is the largest structured corpus of historical English. Starting in March 2015, you can now download COHA for use on your own computer. The COHA data includes 385 million words of text in 116,000 different texts from the 1810s-2000s, in fiction, popular magazines, newspapers, and non-fiction (books).

How to use it?

You can search by words (grieved), phrases (of no little or faint + noun), lemmas (all forms of words, like sing or tall), wildcards (un*ly or r?n*), and more complex searches such as un-X-ed adjectives or a most + ADJ + NOUN. Notice that from the “frequency results” window you can click on the word or phrase to see it in context in this lower window. Start using COHA now by clicking here.

Other corpora

- Davies also provides a list of corpora that you might find very useful. Check out his page: http://corpus.byu.edu/. It includes:

- The Hansard Corpus (speeches from the British Parliament)

- Wikipedia Corpus

- Time Magazine Corpus

- Strathy Corpus (Canada)

- Google books corpora

- Corpora in Spanish and Portuguese

6. For corpora in English and other languages, check out my updated section TermFinder (at the bottom of the list).

Sources:

The British National Corpora (BNC)

Wikipedia: British National Corpus

Full-text corpus data

Image source here

It’s essential that lesson materials are current and relevant. Where can a teacher find information about the features of current spoken English, what language is used currently to carry out certain language functions (e.g. giving directions). So where can a teacher find at a wide range of ongoing changes in the language? The answer is simple — use the corpus.

What is a corpus?

A corpus — is a very large systematic collection of naturally occurring both written and spoken language, usually stored as an electronic database. It consists of texts that have been produced in ‘natural contexts’ (published books, ordinary conversation, newspapers, lectures, etc), which means it mirrors natural language.

A well-composed corpus can be used to answer questions about language use, such as:

- Is the idiom “raining cats and dogs” still used by native speakers?

- Which words most often go together with the word “sense”?

- Is “secede out of Russia” is the correct concordance for ‘secede’?

- What’s the difference between “tactic” and “strategy”?

- Does ‘wicked’ generally mean ‘good’ or ‘bad’? Has this meaning changed over time? Does the use differ between different kinds of text? Do different (kinds of) speakers use the word in the same way?

A corpus a very useful tool when we want to know about frequent patterns in English as it can tell us about which words and phrases are most frequent (and hence the most useful for students to learn).

For example, you want to compare how often the phrasal verb “come up with” is used in written and spoken American English. So you go to any online Corpus you prefer, for example, https://www.english-corpora.org/

So we can see that “come up with” is more used in Spoken English and the usage of it has dropped since 2014.

You can check a corpus if you want to know how the language is used. Just type a word and see the most typical combinations and examples of the phrase in context.

Here are the most frequent collocations with the word ‘changes’ according to COCA:

There are several online corpora:

- The Cambridge English Corpus (CEC) is the largest, reliable, multi-billion word collection of updated written and spoken language, taken from a huge range of sources, including newspapers, the internet, books, magazines, radio, schools, universities, the workplace, and even everyday conversation — and is constantly being updated. The Cambridge English Corpus contains a number of specialized corpora: Cambridge Academic English Corpus, Cambridge Business English Corpus, Cambridge Legal English Corpus, Cambridge Financial English Corpus, etc. It also includes the Cambridge Learner Corpus (CLC) which currently contains over 50 million words taken from Cambridge exam scripts submitted by over 220,000 students from 173 countries, and these numbers keep growing each year. The CLC allows us to conduct internationally relevant and country-specific research into how learners use English differently to expert speakers, as well as allowing us to analyse the different types of mistakes that learners make and what they get right. This research informs our ELT courses.

Find more about the CEC in the video below.

About Cambridge Sketch Engine here.

- The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) — a more than 560-million-word corpus of American English. The corpus is divided into five genres: spoken, fiction, popular magazines, newspapers, and academic journals. The texts come from a variety of sources: transcripts of unscripted conversation from nearly 150 different TV and radio programs, short stories and plays, first chapters of books 1990–present, and movie scripts, magazines, newspapers, and academic Journals. The corpus is free to search through its web interface with a limit on the number of queries per day.

Find more about COCA in the video below.

- The American National Corpus (ANC) is a text corpus of American English containing 22 million words of written and spoken data produced since 1990. Currently, the ANC includes a range of genres, including emerging genres such as email, tweets, and web data. It is annotated for part of speech and lemma, shallow parse, and named entities.

- The British National Corpus (BNC) is a 100-million-word text corpus of samples of written and spoken English from a wide range of sources. The corpus covers British English of the late 20th century from a wide variety of genres, with the intention that it be a representative sample of spoken and written British English of that time.

The corpora mentioned above are the biggest, there are even more different online corpora.

There is also a number of sub-corpora as well, for example, sub-corpora of MICASE with lectures and seminars.

Use corpora to ensure that the language taught in your lessons is natural, accurate and up-to-date; to select the most useful, common words and phrases for a topic or level and to analyse spoken language so that we can teach effective speaking and listening strategies.

Our next articles will be on how to use corpora in lessons and how the language is actually changing. Stay tuned!

- coca (parent phrase)

- cola (parent phrase)

- coca cola

Sentences with «coca cola» (usage examples):

- My nephews birthday is December 23rd and he loves coca cola! (sweetrecipeas.com)

- Fruit juice is proclaimed as being healthy, but it contains just as much sugar as coca cola, milk chocolate, or a slice of birthday cake. (supernaturalacnetreatment.com)

- karma has come and bit him on his french butt.time to party, but i will put the coca cola on ice until after we pick up our losers medals at wembley next weekend. (justarsenal.com)

- (see

more)