Word-composition

(compounding)

is the formation of words by morphologically joining two or more

stems.

A

compound

word

is a word consisting of at least two stems which usually occur in the

language as free forms, e.g. university

teaching award committee member.

The

compound inherits

most of its semantic and syntactic information from its head,

i.e. the most important member of a compound word modified by the

other component.

The

structural

pattern

of English compounds

[

X Y]

y

X

= {root, word, phrase},

Y

= {root, word},

y

= grammatical properties inherited from Y

According

to the

type

of the linking element:

compounds

without

a linking element, e.g. toothache,

bedroom, sweet-heart;

compounds

with a

vowel linking element,

e.g. handicraft,

speedometer;

compounds

with a

consonant linking element,

e.g. statesperson,

craftsman;

compounds

with a

preposition linking stem,

e.g. son-in-law,

lady-in-waiting;

compounds

with a

conjunction linking stem,

e.g. bread-and-butter.

According

to the

type

of relationship

between the components

-in

coordinative

(copulative)

compounds neither of the components dominates the other, e.g.

fifty-fifty,

whisky-and-soda, driver-conductor;

-in

subordinative

(determinative)

compounds the components are neither structurally nor semantically

equal in importance but are based on the domination of one component

over the other, e.g. coffeepot,

Oxford-educated, to headhunt,

blue-eyed,

red-haired

etc.

According

to the

type

of relationship

between the components, subordinative compounds are classified into:

-syntactic

compounds

if their components are placed in the order that resembles the order

of words in free phrases made up according to the rules of Modern

English syntax, e.g. a

know-nothing

— to know nothing, a

blackbird

– a black bird;

-asyntactic

compounds

if they do not conform to the grammatical patterns current in

present-day English, e.g. baby-sitting

– to sit with a baby, oil-rich

– to be rich in oil.

According

to the

way of composition:

—compound

proper

is a compound formed after a composition pattern, i.e. by joining

together the stems of words already available in the language, with

or without the help of special linking elements, e.g. seasick,

looking-glass, helicopter-rescued, handicraft;

-derivational

compound is

a compound which is formed by two simultaneous processes of

composition and derivation; in a derivational compound the structural

integrity of two free stems is ensured by a suffix referring to the

combination as a whole, e.g. long-legged,

many-sided, old-timer, left-hander.

According

to the

semantic relations

between the constituents:

non-idiomatic

compounds,

whose meanings can be described as the sum of their constituent

meanings, e.g. a

sleeping-car, an evening-gown, a snowfall;

compounds

one of the components of which has undergone semantic derivation,

i.e. changed its meaning, e.g. a

blackboard,

a

bluebell;

idiomatic

compounds,

the meaning of which cannot be deduced from the meanings of the

constituents, e.g. a

ladybird,

a

tallboy,

horse-marine.

The

bahuvrihi compounds

(Sanskrit ‘much riced’) are idomatic formations in which a

person, animal or thing is metonymically named after some striking

feature (mainly in their appearance) they possess; their

word-building pattern is an

adjectival stem + a noun stem,

e.g.

bigwig,

fathead, highbrow, lowbrow, lazy-bones.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION 3

CHAPTER 1. THEORETICAL BACKGROUNDS OF WORD-COMPOSITION AS A WAY OF

WORD-FORMATION IN ENGLISH 6

1.1 The means of word-formation in English language 6

1.2 The concept and the essence word-composition 14

CHAPTER 2. STRUCTURAL-SEMANTIC AND FUNCTIONAL FEATURES OF COMPOUND WORDS 19

2.1 The analysis of semantic features of compound words 19

2.2 The analysis of functional features of compound words 24

CHAPTER 3. ANALYTICAL BASES OF USE OF WORD-COMPOSITION 36

3.1 Practical examples of compound words in modern English 36

3.2 New tendencies of use of word-composition as a way of word-formation in

English 38

CONCLUSION 41

LITERATURE 44

APPENDIXES 46

Appendix 1 46

Appendix 2 49

Appendix 3 52

Appendix 4 54

INTRODUCTION

In linguistics, word formation is the creation of a new word. Word formation is sometimes contrasted with semantic

change, which is a change in a

single word’s meaning. The line between word formation and semantic

change is sometimes a bit

blurry; what one person views as a new use of an old word, another person might

view as a new word derived from an old one and identical to it in form. Word

formation can also be contrasted with the formation of idiomatic expressions, though sometimes words can form from

multi-word phrases.

The

subject-matter of the Course Paper is to investigate the

word – composition in the English system of word – formation.

The

topicality of the problem results from the necessity to devote

to description of theoretical bases of allocation of word-composition as way of

word-formation in modern English language.

The

novelty of the problem arises from the necessity to define the

role of word-composition way which is, along with abbreviations, stays one of

the most productive for last decades..

The

main aim of the Course Paper is to summarize and systemize

different methods of word — composition in English.

The

aim

of the course Paper presupposes the solutions of the following tasks:

·

To

expand and update the definition of the term “word — composition”

·

to

define the role of word-composition

According the tasks of the Course

Paper its structure is arranged in the following way:

Introduction,

the Main Part, Conclusion, Resume, Literature, test of Reference Material, List

of Electronic References.

In

the Introduction we provide the explanation of the theme choice, state the

topicality of it, establish the main aim, and the practical tasks of the Paper.

In

the main part we analyze

the character features of the modern classification of word – composition in

the English system of word – formation.

In conclusion we

generalize the results achieved.

CHAPTER 1. THEORETICAL BACKGROUNDS OF WORD-COMPOSITION AS A

WAY OF WORD-FORMATION IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE.

1.1 The means of word-composition in English language The chapter is devoted to

description of theoretical bases of allocation of word-composition as way of

word-formation in modern English language. We try to define the role of

word-composition way which is, along with abbreviations, stays one of the most

productive for last decades. The main way of enrichment of lexicon of any

language is word-formation. All innovations in branches of human knowledge are

fixed in new words and expressions.

The

word-formation system of language is in constant development, as it reflects

evolution of the language. At different stages of language development ways of

word-formation become more or less productive. However there are also ways of

the word-formation which stay productive for a very long time. One of such

methods is word-composition.

Word-composition is a very ancient way of word-formation, and it

serves as powerful tool of the replenishment of language and its grammatical

system perfection for hundred years.

Many researches are devoted composition studying. So, the

considerable contribution to studying of this problem was brought by V.Guz’s,

G.Marchand’s, S.Ulman’s researches, and also the studies of I.V.Arnold,

N.V.Kosarev, E.S.Kubrjakov, O.D.Meshkova, V.J.Ryazanov, A.I.Smirnitsky,

M.D.Stepanova, M.V.Tsareva. That is the problem is widely studied both in domestic,

and in foreign practice.

However it should be noticed that the majority of word-composition studies

concern 70-80 years of the last century, and during last 20 years no serious

researches appeared.

Besides,

the analysis of researches reveals considerable confrontation in opinions of

different authors both in questions of defying the concept of word-formation,

and in approaches of classification of its kinds. There

are different

opinions in concerning quantity of ways of word-formation.

These divergences speak that various ways change the activity and

become more or less productive in a definite period. Anyhow, it is conventional

that modern English has different ways of word-formation: Affixation, suffixation, shortening, prefixation, conversion and

composition or compound. Compounding or word-composition is

one of the productive types of word-formation in Modern English. Composition

like all other ways of deriving words has its own peculiarities as to the means used, the nature of

bases and their distribution, as to the range of application, the scope of

semantic classes and the factors conducive to productivity. Compounding or

word composition is one of the productive types of

word-formation in Modern English. Composition like all other ways of deriving

words has its own peculiarities as to the means used , the nature of bases

and their distribution , as to the range of application , the scope of

semantic classes and the factors conducive to productivity. Compounds are

made up of two ICs which are both derivational bases. Compound words are

inseparable vocabulary units. They are formally and semantically dependent on

the constituent bases and the semantic relations between them which mirror the

relations between the motivating units. The ICs of compound words represent

bases of all three structural types.

1.

The

bases built on stems may be of different degree

2. Of complexity as,

e.g., week-end,

office-management, postage-stamp, aircraft-carrier, fancy-dress-maker, etc. However, this complexity of

structure of bases is not typical of the bulk of Modern English compounds. In this connection

care should be taken not to confuse compound words with polymorphic words of

secondary derivation, i.e. derivatives built according to an affixal

pattern but on a compound stem for its base such as, e.g., school-mastership ([n+n]+suf), ex—housewife (prf+[n+n]),to weekend, to

spotlight ([n+n]+conversion).

CHAPTER 2. STRUCTURAL-SEMANTIC AND FUNCTIONAL

FEATURES OF COMPOUND WORDS

2.1 Structural

features

Compound words like all

other inseparable vocabulary units take shape in a definite system of

grammatical forms, syntactic and semantic features. Compounds, on the one hand,

are generally clearly distinguished from and often opposed to free word-groups,

on the other hand they lie astride the border-line between words and

word-groups and display close ties and correlation with the system of free

word-groups. The structural inseparability of compound words

finds expression in the unity of their specific

distributional pattern and specific

stress

and spelling pattern.

Structurally compound

words are characterized by the specific order and arrangement in which bases

follow one another. The order in which the two bases are placed within a

compound is rigidly fixed in

Modern English and it is the second IC that makes the head-member of the word,

i.e. its structural and semantic centre. The head-member is of basic importance

as it preconditions both the lexico-grammatical and semantic features of the

first component. It is of interest to note that the difference between stems

(that serve as bases in compound words) and word-forms they coincide with is most

obvious in some compounds, especially in compound adjectives. Adjectives

like long, wide,

rich are

characterized by grammatical forms of degrees of comparison longer, wider, richer. The

corresponding stems functioning as bases in compound words lack grammatical

independence and forms proper to the words and retain only the part-of-speech

meaning; thus compound adjectives with adjectival stems for their second

components, e. g. age-long, oil-rich, inch-wide, do not form degrees of comparison as the compound

adjective oil-rich does not form

them the way the word rich does, but conforms to the general rule of

polysyllabic adjectives and has analytical forms of degrees of comparison. The

same difference between words and stems is not so noticeable in compound nouns

with the noun-stem for the second component.

Phonetically compounds

are also marked by a specific structure of their own. No phonemic changes of

bases occur in composition but the compound word acquires a new stress pattern,

different from the stress in the motivating words, for example words key and hole or hot and house each possess

their own stress but when the stems of these words are brought together to make

up a new compound word, ‘keyhole — ‘a hole in a lock into which a key fits’, or ‘hothouse — ‘a heated

building for growing delicate plants’, the latter is given a different stress

pattern — a unity stress on the first component in our case. Compound words

have three stress patterns: a high or unity stress on the first component as

in ‘honeymoon,

‘doorway, etc. a double stress, with a primary stress on the first

component and a weaker, secondary stress on the second component, e. g. ‘blood-ֻvessel, ‘mad-ֻdoctor, ‘washing-ֻmachine,

etc. It is not infrequent, however, for both ICs to have level stress as in,

for instance, ‘arm-‘chair,

‘icy-‘cold, ‘grass-‘green, etc.

Graphically most

compounds have two types of spelling — they are spelt either solidly or with a

hyphen. Both types of spelling when accompanied by structural and phonetic

peculiarities serve as a sufficient indication of inseparability of compound

words in contradistinction to phrases. It is true that hyphenated spelling by

itself may be sometimes misleading, as it may be used in word-groups to

emphasize their phraseological character as in e. g. daughter-in-law, man-of-war,

brother-in-arms or in longer combinations of words to indicate

the semantic unity of a string of words used attributively as, e.g., I-know-what-you’re-going-to-say

expression, we-are-in-the-know jargon, the young-must-be-right attitude. The two types of

spelling typical of compounds, however, are not rigidly observed and there are

numerous fluctuations between solid or hyphenated spelling on the one hand and

spelling with a break between the components on the other, especially in

nominal compounds of then+n type. The spelling of these compounds varies

from author to author and from dictionary to dictionary. For example, the

words war-path,

war-time, money-lender are spelt both with a hyphen and solidly; blood-poisoning, money-order,

wave-length, war-ship— with a hyphen and with a break; underfoot, insofar, underhand—solidly

and with a break25.

It is noteworthy that new compounds of this type tend to solid or hyphenated

spelling. This inconsistency of spelling in compounds, often accompanied by a

level stress pattern (equally typical of word-groups) makes the problem of

distinguishing between compound words (of the n + n type in particular) and word-groups

especially difficult.

In

this connection it should be stressed that Modern English nouns (in the Common

Case, Sg.) as has been universally recognized possess an attributive function

in which they are regularly used to form numerous nominal phrases as, e.

g. peace years,

stone steps, government office, etc. Such variable nominal phrases are semantically

fully derivable from the meanings of the two nouns and are based on the

homogeneous attributive semantic relations unlike compound words. This system

of nominal phrases exists side by side with the specific and numerous classes

of nominal compounds which as a rule carry an additional semantic component

not found in phrases.

It

is also important to stress that these two classes of vocabulary units —

compound words and free phrases — are not only opposed but also stand in close

correlative relations to each other.

2.2

Semantic features

Semantically compound

words are generally motivated units. The meaning of the compound is first of

all derived from the combined lexical meanings of its components. The semantic

peculiarity of the derivational bases and the semantic difference between the

base and the stem on which the latter is built is most obvious in compound

words. Compound words with a common second or first component can serve as

illustrations. The stem of the word board is polysemantic and its multiple meanings serve as

different derivational bases, each with its own selective range for the

semantic features of the other component, each forming a separate set of

compound words, based on specific derivative relations. Thus the base board meaning ‘a flat

piece of wood square or oblong’ makes a set of compounds chess-board, notice-board,

key-board, diving-board, foot-board, sign-board; compounds paste-board, cardboard are built on the

base meaning ‘thick, stiff paper’; the base board– meaning ‘an authorized body of men’, forms

compounds school-board,

board-room. The

same can be observed in words built on the polysemantic stem of the word foot. For example,

the base foot– in foot-print, foot-pump,

foothold, foot-bath, foot-wear has the meaning of ‘the terminal

part of the leg’, in foot-note, foot-lights, foot-stone the base foot– has the

meaning of ‘the lower part’, and in foot-high, foot-wide, footrule — ‘measure of

length’. It is obvious from the above-given examples that the meanings of the

bases of compound words are interdependent and that the choice of each is

delimited as in variable word-groups by the nature of the other IC of the word.

It thus may well be said that the combination of bases serves as a kind of

minimal inner context distinguishing the particular individual lexical meaning

of each component. In this connection we should also remember the significance

of the differential meaning found in both components which becomes especially

obvious in a set of compounds containing identical bases.

CLASSIFICATION

OF WORD — COMPOSITION

Compound

words can be described from different points of view and consequently may be

classified according to different principles. They may be viewed from the point

of view:

·

of

general relationship and degree of semantic independence of components;

·

of

the parts of speech compound words represent;

·

of

the means of composition used to link the two ICs together;

·

of

the type of ICs that are brought together to form a compound;

·

of

the correlative relations with the system of free word-groups.

From the point of view of degree of semantic independence there are two types

of relationship between the ICs of compound words that are generally

recognized in linguistic literature: the relations of coordination and

subordination, and accordingly compound words fall into two classes: coordinative compounds (often

termed copulative or additive) and subordinative (often termed determinative).

In coordinative compounds

the two ICs are semantically equally important as in fighter-bomber, oak-tree,

girl-friend, Anglo-American. The constituent bases belong to the

same class and той often to the same

semantic group. Coordinative compounds make up a comparatively small group of

words. Coordinative compounds fall into three groups:

1.

Reduplicative compounds

which are made up by the repetition of the same base as in goody-goody, fifty-fifty,

hush-hush, pooh-pooh. They are all only partially motivated.

2.

Compounds

formed by joining the phonically variated rhythmic twin forms which either

alliterate with the same initial consonant but vary the vowels as in chit-chat, zigzag, sing-song, or

rhyme by varying the initial consonants as in clap-trap, a walky-talky, helter-skelter. This subgroup

stands very much apart. It is very often referred to pseudo-compounds and

considered by some linguists irrelevant to productive word-formation owing to

the doubtful morphemic status of their components. The constituent members of

compound words of this subgroup are in most cases unique, carry very vague or

no lexical meaning of their own, are not found as stems of independently

functioning words. They are motivated mainly through the rhythmic doubling of

fanciful sound-clusters.

3.

Coordinative compounds of both subgroups

(a, b) are mostly restricted to the colloquial layer, are marked by a heavy

emotive charge and possess a very small degree of productivity.

The bases of additive compounds such as a queen-bee, an actor-manager,

unlike the compound words of the first two subgroups, are built on stems of the

independently functioning words of the same part of speech. These bases often

semantically stand in the genus-species relations. They denote a person or an

object that is two things at the same time. A secretary-stenographer is thus a person who is

both a stenographer and a secretary, a bed-sitting-room (a bed-sitter) is both a bed-room and a sitting-room at

the same time. Among additive compounds there is a specific subgroup of

compound adjectives one of ICs of which is a bound root-morpheme. This group is

limited to the names of nationalities such as Sino-Japanese, Anglo-Saxon, Afro-Asian, etc.

Additive compounds of this group are

mostly fully motivated but have a very limited degree of productivity.

However it must be stressed that though

the distinction between coordinative and subordinative compounds is generally

made, it is open to doubt and there is no hard and fast border-line between

them. On the contrary, the border-line is rather vague. It often happens that

one and the same compound may with equal right be interpreted either way — as a

coordinative or a subordinative compound, e. g. a woman-doctor may be

understood as ‘a woman who is at the same time a doctor’ or there can be traced

a difference of importance between the components and it may be primarily felt

to be ‘a doctor who happens to be a woman’ (also a mother-goose, a clock-tower). In

subordinative compounds the components are neither structurally nor

semantically equal in importance but are based on the domination of the

head-member which is, as a rule, the second IC. The second IC thus is the

semantically and grammatically dominant part of the word, which preconditions

the part-of-speech meaning of the whole compound as in stone-deaf, age-long which

are obviously adjectives, a wrist-watch, road-building, a baby-sitter which

are nouns.

Functionally compounds are viewed as words

of different parts of speech. It is the head-member of the compound, i.e. its

second IC that is indicative of the grammatical and lexical category the

compound word belongs to.

Compound words are found in all parts of

speech, but the bulk of compounds are nouns and adjectives. Each part of

speech is characterized by its set of derivational patterns and their semantic

variants. Compound adverbs, pronouns and connectives are represented by an

insignificant number of words, e. g. somewhere, somebody, inside, upright, otherwise moreover,

elsewhere, by means of, etc. No new compounds are coined on this pattern.

Compound pronouns and adverbs built on the repeating first and second IC

like body, ever,

thing make

closed sets of words

SOME |

+ |

BODY |

ANY |

THING |

|

EVERY |

ONE |

|

NO |

WHERE |

On the whole composition is not productive

either for adverbs, pronouns or for connectives. Verbs are of special

interest. There is a small group of compound verbs made up of the combination

of verbal and adverbial stems that language retains from earlier stages, e.

g. to bypass, to

inlay, to offset. This type according to some authors, is no longer

productive and is rarely found in new compounds. There are many polymorphic

verbs that are represented by morphemic sequences of two root-morphemes,

like to weekend,

to gooseflesh, to spring-clean, but derivationally they are all words of secondary

derivation in which the existing compound nouns only serve as bases for

derivation. They are often termed pseudo-compound verbs. Such polymorphic

verbs are presented by two groups: 1)verbs formed by means of conversion from

the stems of compound nouns as in to spotlight from a spotlight, to sidetrack from a side-track, to

handcuff from handcuffs, to blacklist from a blacklist, to

pinpoint from a pin-point;

2) verbs formed by back-derivation from

the stems of compound nouns, e. g. to baby-sit from a baby-sitter, to playact from play-acting, to

housekeep from house-keeping, to spring-clean from spring-cleaning.

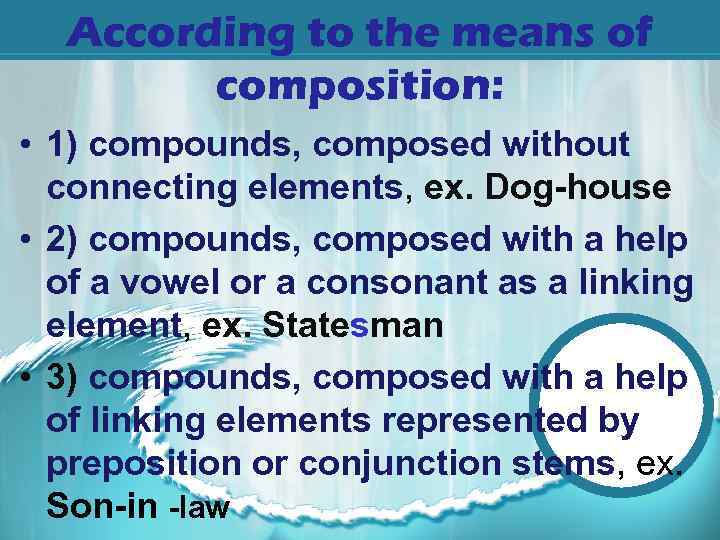

From the point of view of the means by

which the components are joined together, compound words may be classified

into:

Words formed by merely placing one constituent

after another in a definite order which thus is indicative of both

the semantic value and the morphological unity of the compound, e. g. rain-driven, house-dog,

pot-pie (as opposed to dog-house, pie-pot). This means of linking

the components is typical of the majority of Modern English compounds in all

parts of speech.

As to the order of components,

subordinative compounds are often classified as:

Ø asyntactic compounds in which the order of

bases runs counter to the order in which the motivating words can be brought

together under the rules of syntax of the language. For example, in variable

phrases adjectives cannot be modified by preceding adjectives and noun

modifiers are not placed before participles or adjectives, yet this kind of

asyntactic arrangement is typical of compounds, e. g. red-hot, bluish-black,

pale-blue, rain-driven, oil-rich. The asyntactic order is

typical of the majority of Modern English compound words;

Ø syntactic compounds whose components are

placed in the order that resembles the order of words in free phrases arranged

according to the rules of syntax of Modern English. The order of the components

in compounds like blue-bell, mad-doctor, blacklist ( a + n ) reminds one of the order and

arrangement of the corresponding words in phrases a blue bell, a mad doctor, a

black list (

A + N ), the order of compounds of the typedoor-handle, day-time,

spring-lock (

n + n ) resembles the order of words in nominal phrases with

attributive function of the first noun ( N + N ),e. g. spring time, stone steps, peace movement.

Ø Compound words whose ICs are joined

together with a

special linking-element — the linking vowels [ou] and occasionally

[i] and the linking consonant [s/z] — which is indicative of composition as in,

for example, speedometer,

tragicomic, statesman. Compounds of this type can be both nouns and

adjectives, subordinative and additive but are rather few in number since they

are considerably restricted by the nature of their components. The additive

compound adjectives linked with the help of the vowel [ou] are limited to the

names of nationalities and represent a specific group with a bound root for the

first component, e. g. Sino-Japanese, Afro-Asian, Anglo-Saxon.

In subordinative adjectives and nouns the

productive linking element is also [ou] and compound words of the type are most

productive for scientific terms. The main peculiarity of compounds of the type

is that their constituents are non-assimilated bound roots borrowed mainly from

classical languages, e. g. electro-dynamic, filmography, technophobia, videophone,

sociolinguistics, videodisc.

A small group of compound nouns may also

be joined with the help of linking consonant [s/z], as in sportsman, landsman,

saleswoman, bridesmaid.This small group of words is restricted by the second

component which is, as a rule, one of the three bases man–, woman–, people–.

The commonest of them is man–.

Compounds may be also classified according

to the nature of the bases and the interconnection with other ways of

word-formation into the so-called compounds proper and derivational compounds.

Compounds

proper are formed by joining together bases

built on the stems or on the word-forms of independently functioning words with

or without the help of special linking element such as doorstep, age-long,

baby-sitter, looking-glass, street-fighting, handiwork, sportsman. Compounds

proper constitute the bulk of English compounds in all parts of speech, they

include both subordinative and coordinative classes, productive and

non-productive patterns.

Derivational

compounds, e. g. long-legged, three-cornered, a

break-down, a pickpocket differ from compounds proper in the nature of bases

and their second IC. The two ICs of the compound long-legged — ‘having long

legs’ — are the suffix –ed meaning ‘having’ and the base built on a free

word-group long

legs whose

member words lose their grammatical independence, and are reduced to a single

component of the word, a derivational base. Any other segmentation of such

words, say into long– and legged– is impossible

because firstly, adjectives like *legged do not exist in Modern English and secondly, because

it would contradict the lexical meaning of these words. The derivational

adjectival suffix –ed converts this newly formed base into a word. It can be

graphically represented as long legs à [ (long–leg) + –ed] à long–legged.

The suffix –ed becomes the grammatically

and semantically dominant component of the word, its head-member. It imparts

its part-of-speech meaning and its lexical meaning thus making an adjective

that may be semantically interpreted as ‘with (or having) what is denoted by

the motivating word-group’. Comparison of the pattern of compounds proper

like baby-sitter,

pen-holder

[ n +

( v + –er ) ] with the pattern of derivational compounds

like long-legged [ (a + n) + –ed ] reveals the

difference: derivational compounds are formed by a derivational means, a suffix

in case if words of the long-legged type, which is applied to a base that each time is

formed anew on a free word-group and is not recurrent in any other type if

words. It follows that strictly speaking words of this type should be treated

as pseudo-compounds or as a special group of derivatives. They are habitually

referred to derivational compounds because of the peculiarity of their

derivational bases which are felt as built by composition, i.e. by bringing

together the stems of the member-words of a phrase which lose their

independence in the process. The word itself, e. g. long-legged, is built by the

application of the suffix, i.e. by derivation and thus may be described as a

suffixal derivative.

Derivational compounds or pseudo-compounds

are all subordinative and fall into two groups according to the type of variable

phrases that serve as their bases and the derivational means used:

Ø derivational

compound adjectives formed

with the help of the highly-productive adjectival suffix –ed applied to bases

built on attributive phrases of the A + N, Num + N, N + N type, e. g. long legs, three corners, doll

face. Accordingly

the derivational adjectives under discussion are built after the patterns [ (a + n ) + –ed], e.

g. long-legged,

flat-chested, broad-minded; [ ( пит + n) + –ed], e. g. two-sided, three-cornered; [ (n + n ) + –ed], e. g. doll-faced, heart-shaped.

Ø derivational

compound nouns formed

mainly by conversion applied to bases built on three types of variable phrases

— verb-adverb phrase, verbal-nominal and attributive phrases.

The commonest type of phrases that serves

as derivational bases for this group of derivational compounds is the V + Adv type

of word-groups as in, for instance, a breakdown, a breakthrough, a castaway, a layout.

Semantically derivational compound nouns form lexical groups typical of

conversion, such as an act or instance of the action, e. g. a holdup — ‘a delay in

traffic’’ from to

hold up — ‘delay, stop by use of force’; a result of the

action, e. g. a

breakdown —

‘a failure in machinery that causes work to stop’ from to break down — ‘become

disabled’; an active agent orrecipient of the action, e. g. cast-offs — ‘clothes that he

owner will not wear again’ from to cast off — ‘throw away as unwanted’; a show-off —

‘a person who shows off’ from to show off — ‘make a display of one’s abilities

in order to impress people’. Derivational compounds of this group are spelt

generally solidly or with a hyphen and often retain a level stress.

Semantically they are motivated by transparent derivative relations with the

motivating base built on the so-called phrasal verb and are typical of the

colloquial layer of vocabulary. This type of derivational compound nouns is

highly productive due to the productivity of conversion.

The semantic subgroup of derivational

compound nouns denoting agents calls for special mention. There is a group of

such substantives built on an attributive and verbal-nominal type of phrases.

These nouns are semantically only partially motivated and are marked by a heavy

emotive charge or lack of motivation and often belong to terms as, for

example, a

kill-joy, a wet-blanket — ‘one who kills enjoyment’; a turnkey —

‘keeper of the keys in prison’; a sweet-tooth — ‘a person who likes sweet

food’; a

red-breast — ‘a bird called the robin’. The analysis of these

nouns easily proves that they can only be understood as the result of

conversion for their second ICs cannot be understood as their structural or

semantic centres, these compounds belong to a grammatical and lexical groups

different from those their components do. These compounds are all animate

nouns whereas their second ICs belong to inanimate objects. The meaning of the

active agent is not found in either of the components but is imparted as a

result of conversion applied to the word-group which is thus turned into a

derivational base.

These compound nouns are often referred to

in linguistic literature as «bahuvrihi» compounds or exocentric compounds, i.e.

words whose semantic head is outside the combination. It seems more correct to

refer them to the same group of derivational or pseudo-compounds as the above

cited groups.

This small group of derivational nouns is

of a restricted productivity, its heavy constraint lies in its idiomaticity and

hence its stylistic and emotive colouring.

The linguistic analysis of extensive language

data proves that there exists a regular correlation between the system of free

phrases and all types of subordinative (and additive) compounds26. Correlation

embraces both the structure and the meaning of compound words, it underlies the

entire system of productive present-day English composition conditioning the

derivational patterns and lexical types of compounds.

Compounds are words produced by combining

two or more stems which occur in the language as free forms. They may be classified

proceeding from different criteria:

according to the parts of speech to which

they belong;

according to the means of composition used

to link their ICs together;

according to the structure of their ICs;

according to their semantic characteristics.

3.1 Correlation

types of compounds

The

description of compound words through the correlation with variable word-groups

makes it possible to classify them into four major classes: adjectival-nominal,

verbal-nominal, nominal and verb – adverb compounds.

I. A d j e c t i v a l — n o m i n a l

comprise four subgroups of compound

adjectives, three of them are proper

compounds and one derivational.

All four subgroups are productive and

semantically as a rule motivated.

The main constraint on the productivity in

all the four subgroups is

the lexical-semantic types of the

head-members and the lexical valency of

the head of the correlated word-groups.

Adjectival-nominal compound adjectives

have the following patterns:

1) the polysemantic n+a

pattern

that gives rise to two types:

a) compound adjectives based on semantic

relations of resemblance

with adjectival bases denoting most

frequently colours, size, shape, etc. for

the second IC. The type is correlative

with phrases of comparative type as

A +as + N,

e.g.

snow-white,

skin-deep, age-long, etc.

b) compound adjectives based on a variety

of adverbial relations. The

type is correlative with one of the most

productive adjectival phrases of

the A +

prp

+

N

type

and consequently semantically varied, cf. colourblind,

road-weary, care-free, etc.

2) the monosemantic pattern n+ven

based

mainly on the instrumental, locative and temporal relations between the ICs

which are:

conditioned by the lexical meaning and

valency of the verb, e.g. stateowned,

home-made. The type is highly

productive. Correlative relations

are established with word-groups of the Ven+

with/by

+

N

type.

3) the monosemantic пит

+

п pattern

which gives rise to a small and

peculiar group of adjectives, which are

used only attributively, e.g. (a) twoday

(beard), (a) seven-day

(week),

etc. The type correlates with attributive

phrases with a numeral for their first

member.

4) a highly productive monosemantic

pattern of derivational compound

adjectives based on semantic relations of

possession conveyed by the suffix

-ed. The basic variant is [(a+n)+ -ed],

e.g.

low-ceilinged,

long- legged.

The pattern has two more variants: [(пит

+

n)

+

-ed),

l(n+n)+ -ed], e.g.

one-sided, bell-shaped, doll-faced. The

type correlates accordingly with

phrases with (having) + A+N,

with

(having) + Num +

N,

with

+

N + N

or with +

N + of + N.

The system of productive types of compound

adjectives is summarised

in Table 1. (Appendix)

II. V e r b a l — n o m i n a l compounds

may be described through one derivational structure n+nv,

i.e.

a combination of a noun-base (in most

cases simple) with a deverbal, suffixal

noun-base. The structure includes

four patterns differing in the character

of the deverbal noun- stem and accordingly

in the semantic subgroups of compound

nouns. All the patterns

correlate in the final analysis with V+N

and

V+prp+N

type

which depends

on the lexical nature of the verb:

1) [n+(v+-er)],

e.g.

bottle-opener,

stage-manager, peace-fighter. The

pattern is monosemantic and is based on

agentive relations that can be interpreted

‘one/that/who does smth’.

2) [n+(v+

-ing)],

e.g.

stage-managing,

rocket-flying. The pattern is

monosemantic and may be interpreted as

‘the act of doing smth’. The pattern

has some constraints on its productivity

which largely depends on the

lexical and etymological character of the

verb.

3) [n+(v+ -tion/ment)], e.g.

office-management,

price-reduction. The

pattern is a variant of the above-mentioned

pattern (No 2). It has a heavy

constraint which is embedded in the

lexical and etymological character of

the verb that does not permit

collocability with the suffix -ing or deverbal

nouns.

4) [n+(v +

conversion)],

e.g.

wage-cut,

dog-bite, hand-shake, the pattern

is based on semantic relations of result,

instance, agent, etc.

III. N o m i n a l c o m p o u n d s are

all nouns with the most

polysemantic and highly-productive

derivational pattern n+n; both bases

re generally simple stems, e.g. windmill,

horse-race, pencil-case. The

pattern conveys a variety of semantic

relations, the most frequent are the

relations of purpose, partitive, local and

temporal relations. The pattern

correlates with nominal word-groups of the

N+prp+N

type.

IV. V e r b — a d v e r b compounds are

all derivational nouns, highly

productive and built with the help of

conversion according to the pattern l(v + adv) + conversion].

The

pattern correlates with free phrases

V + Adv

and

with all phrasal verbs of different degree of stability. The pattern

is polysemantic and reflects the manifold

semantic relations typical of

conversion pairs.

The system of productive types of compound

nouns is summarized in

Table

2. (Appendix)

ANALYTICAL BASES

OF USE OF WORD-COMPOSITION 36

3.1 Practical examples of compound words.

Here are the

practical examples of compound words in “Theater” of W. Somerset Maugham.

Business – like [n+(v

+

conversion)],

is

based on semantic relations of result, – довольно по

деловому

(ch.1 p 3)

well – known

(ch

1 p

4) [a+v]

– хорошо известный

ink – stand (ch 1 p 4) [n+v] —

чернильница

heavily – painted lips (ch 1 p 5)

[a+v+ed] ярко- накрашенные губы

dressing – table (ch 1 p

туалетный

столик

eyebrow — (ch 1 p

satinwood — (ch 1 p

атласное дерево

CONCLUSION

1. Compound words are made up of two ICs,

both of which are derivational bases.

2. The structural and semantic centre of

acompound, i.e. its head-member, is its second IC, which preconditions the part

of speech the compound belongs to and its lexical class.

3. Phonetically compound words are marked

by three stress patterns

— a unity stress, a double stress and a

level stress. The first two are the

commonest stress patterns in compounds.

4. Graphically as a rule compounds are

marked by two types of spelling

— solid spelling and hyphenated spelling.

Some types of compound

words are characterised by fluctuations

between hyphenated spelling and

spelling with a space between the components.

5. Derivational patterns in compound words

may be mono- and

polysemantic, in which case they are based

on different semantic relations

between the components.

6. The meaning of compound words is

derived from the combined

lexical meanings of the components and the

meaning of the derivational

pattern.

7. Compound words may be described from

different points of view:

a) According to the degree of semantic

independence of components

compounds are classified into coordinative

and subordinative. The bulk of

present-day English compounds are

subordinative.

b) According to different parts of speech.

Composition is typical in

Modern English mostly of nouns and

adjectives.

c) According to the means by which

components are joined together

they are classified into compounds formed

with the help of a linking element

and without. As to the order of ICs it may

be asyntactic and syntactic.

d) According to the type of bases

compounds are classified into compounds

proper and derivational compounds.

e) According to the structural semantic

correlation with free phrases

compounds are subdivided into

adjectival-nominal compound adjectives,

verbal-nominal, verb-adverb and nominal

compound nouns.

8. Structural and semantic correlation is

understood as a regular interdependence

between compound words and variable

phrases. A potential

possibility of certain types of phrases

presupposes a possibility of compound

words

conditioning their structure and semantic type.

APPENDIX

TABLE 1. Productive Types of

Compound Adjectives

|

Free |

Compound |

|||

|

Compounds |

Derivational Compounds |

Pattern |

Semantic |

|

|

1) (a). as white |

snow-white |

— |

n |

relations |

|

(b). in tired care-free, |

oil-rich, power-greedy, pleasuretired |

— |

— |

various adverbial relations |

|

2.c bound |

snow-covered duty-bound |

n |

instrumental (or agentive relations |

|

|

3. two days |

(a) two-day (beard) (b) seven-year (plan) |

— |

num |

quantitative |

|

wi t h ( h a v i |

long-legged |

[(a |

possessive |

APENDIX 2.

TABLE 2. Productive Types of Compound Nouns

|

Free |

Compound |

||

|

Compounds Proper |

Derivational Compounds |

Pattern |

|

|

Verbal prices prices shake |

1) price-reducing price-reduction hand-shake |

— |

— -ing)] ment)] |

|

Nominal ashes a run woman sword |

1) neck house 5) 6) |

— |

— [n’ + |

|

Verb to away |

a break-down a castaway a runaway |

[(v + |

-

Скачать презентацию (0.24 Мб)

-

12 загрузок -

0.0 оценка

Ваша оценка презентации

Оцените презентацию по шкале от 1 до 5 баллов

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Комментарии

Добавить свой комментарий

Аннотация к презентации

Скачать презентацию (0.24 Мб). Тема: «Word composition». Содержит 15 слайдов. Посмотреть онлайн с анимацией. Загружена пользователем в 2019 году. Оценить. Быстрый поиск похожих материалов.

-

Формат

pptx (powerpoint)

-

Количество слайдов

15

-

Слова

-

Конспект

Отсутствует

Содержание

-

-

Слайд 2

Word composition is the type of word- formation, in which new words are produced by combining two or more Immediate Constituents ( ICs), which are both derivational bases.

-

Слайд 3

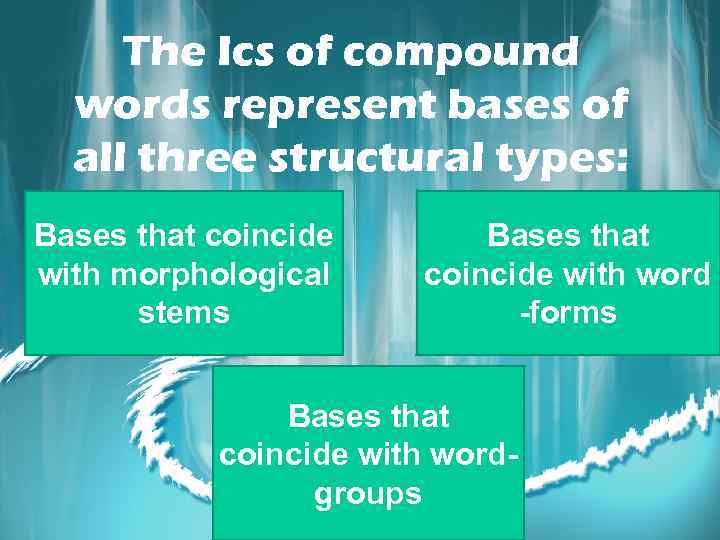

The Ics of compound words represent bases of all three structural types:

Bases that coincide with morphological stems

Bases that coincide with word-forms

Bases that coincide with word-groups -

Слайд 4

The bases built on stems may be of different degrees of complexity:

Simple week-end

2) Derived letter-writer

3) Compound aircraft-carrier -

Слайд 5

The meaning of compound word is made up of two components: structural and lexical.

-

Слайд 6

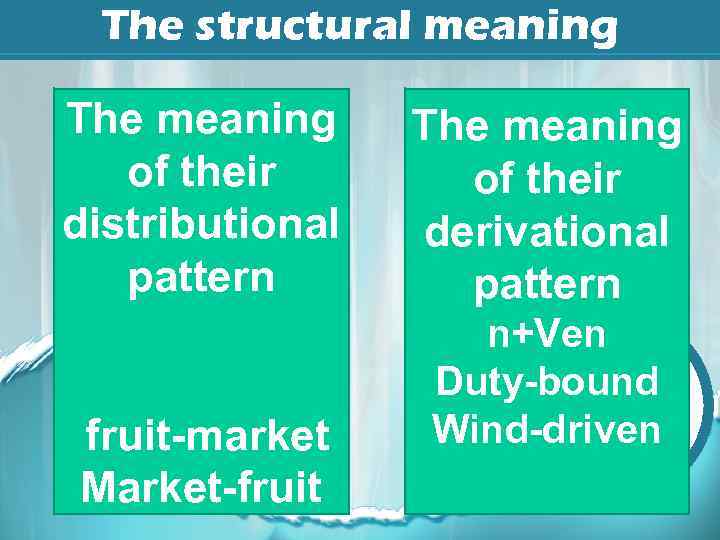

The structural meaning

The meaning of their distributional pattern

fruit-market

Market-fruit

The meaning of their derivational pattern

n+Ven

Duty-bound

Wind-driven -

Слайд 7

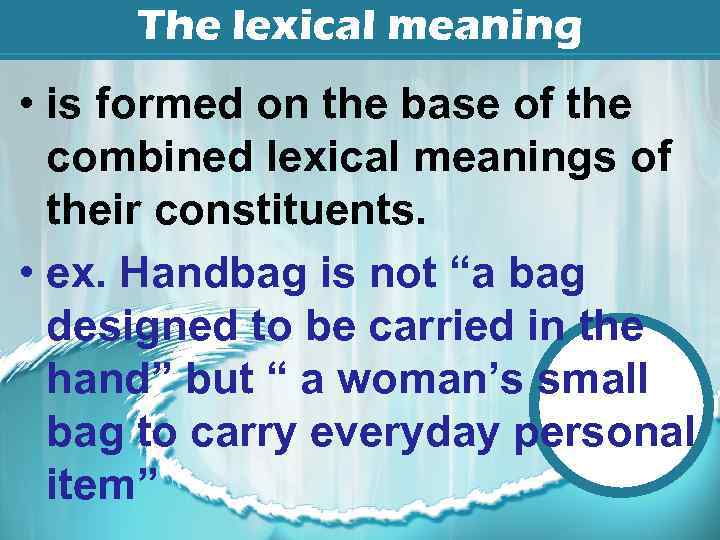

The lexical meaning

is formed on the base of the combined lexical meanings of their constituents.

ex. Handbag is not “a bag designed to be carried in the hand” but “ a woman’s small bag to carry everyday personal item” -

Слайд 8

Classification of compound words

-

Слайд 9

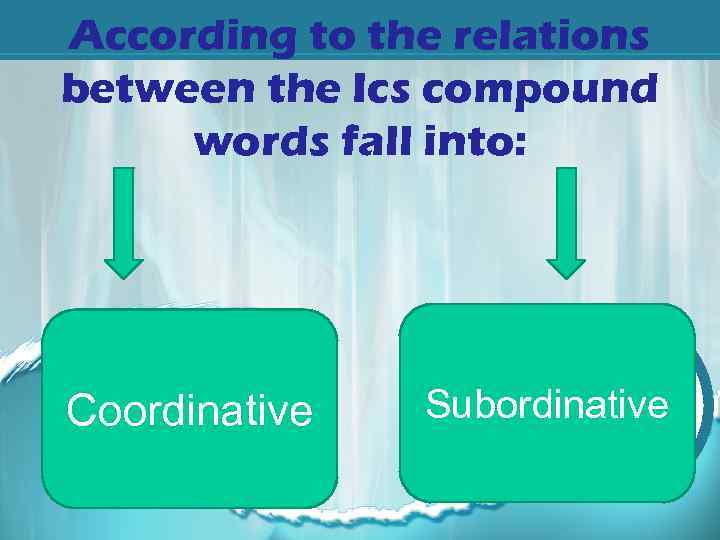

According to the relations between the Ics compound words fall into:

Coordinative

Subordinative -

Слайд 10

Coordinative compounds:

A) reduplicative : poof-poof, fifty-fifty

B) compounds formed by joining the phonically variated rhythmic twin forms: chit-chat, zig-zag

C) additive compounds: actor -manager -

Слайд 11

Subordinative compounds

Based on the domination of the head-member which is the second IC.

ex. Stone-deaf, age-long -

Слайд 12

According to the part of speech compounds fall into:

Compound nouns- sunbeam

Compound Adjectives – heart-free

Compound pronouns- somebody, nothing -

Слайд 13

Compound adverbs- nowhere, inside

Compound verbs- to bypass -

Слайд 14

According to the means of composition:

1) compounds, composed without connecting elements, ex. Dog-house

2) compounds, composed with a help of a vowel or a consonant as a linking element, ex. Statesman

3) compounds, composed with a help of linking elements represented by preposition or conjunction stems, ex. Son-in -law -

Слайд 15

According to the type of bases

Compounds proper

ex. Door-step

Derivational compoundsEx. Long-legged

Посмотреть все слайды

Сообщить об ошибке

Похожие презентации

Спасибо, что оценили презентацию.

Мы будем благодарны если вы поможете сделать сайт лучше и оставите отзыв или предложение по улучшению.

Добавить отзыв о сайте

Ответы на госы по лексикологии

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 1

1. Lexicology, its aims and significance

Lexicology is a branch of linguistics which deals with a systematic description and study of the vocabulary of the language as regards its origin, development, meaning and current use. The term is composed of 2 words of Greek origin: lexis + logos. A word about words, or the science of a word. It also concerns with morphemes, which make up words and the study of a word implies reference to variable and fixed groups because words are components of such groups. Semantic properties of such words define general rules of their joining together. The general study of the vocabulary irrespective of the specific features of a particular language is known as general lexicology. Therefore, English lexicology is called special lexicology because English lexicology represents the study into the peculiarities of the present-day English vocabulary.

Lexicology is inseparable from: phonetics, grammar, and linguostylistics b-cause phonetics also investigates vocabulary units but from the point of view of their sounds. Grammar- grammatical peculiarities and grammatical relations between words. Linguostylistics studies the nature, functioning and structure of stylistic devices and the styles of a language.

Language is a means of communication. Thus, the social essence is inherent in the language itself. The branch of linguistics which deals with relations between the language functions on the one hand and the facts of social life on the other hand is termed sociolinguistics.

Modern English lexicology investigates the problems of word structure and word formation; it also investigates the word structure of English, the classification of vocabulary units, replenishment3 of the vocabulary; the relations between different lexical layers4 of the English vocabulary and some other. Lexicology came into being to meet the demands of different branches of applied linguistic! Namely, lexicography — a science and art of compiling dictionaries. It is also important for foreign language teaching and literary criticism.

2. Referential approach to meaning

SEMASIOLOGY

There are different approaches to meaning and types of meaning

Meaning is the object of semasiological study -> semasiology is a branch of lexicology which is concerned with the study of the semantic structure of vocabulary units. The study of meaning is the basis of all linguistic investigations.

Russian linguists have also pointed to the complexity of the phenomenon of meaning (Потебня, Щерба, Смирницкий, Уфимцева и др.)

There are 3 main types of definition of meaning:

(a) Analytical or referential definition

(b) Functional or contextual approach

(c) Operational or information-oriented definition of meaning

REFERENTIAL APPROACH

Within the referential approach linguists attempt at establishing interdependence between words and objects of phenomena they denote. The idea is illustrated by the so-called basic triangle:

Concept

Sound – form_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Referent

[kæt] (concrete object)

The diagram illustrates the correlation between the sound form of a word, the concrete object it denotes and the underlying concept. The dotted line suggests that there is no immediate relation between sound form and referent + we can say that its connection is conventional (human cognition).

However the diagram fails to show what meaning really is. The concept, the referent, or the relationship between the main and the concept.

The merits: it links the notion of meaning to the process of namegiving to objects, process of phenomena. The drawbacks: it cannot be applied to sentences and additional meanings that arise in the conversation. It fails to account for polysemy and synonymy and it operates with subjective and intangible mental process as neither reference nor concept belong to linguistic data.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 2

1. Functional approach to meaning

SEMASIOLOGY

There are different approaches to meaning and types of meaning

Meaning is the object of semasiological study -> semasiology is a branch of lexicology which is concerned with the study of the semantic structure of vocabulary units. The study of meaning is the basis of all linguistic investigations.

Russian linguists have also pointed to the complexity of the phenomenon of meaning (Потебня, Щерба, Смирницкий, Уфимцева и др.)

There are 3 main types of definition of meaning:

(a) Analytical or referential definition

(b) Functional or contextual approach

(c) Operational or information-oriented definition of meaning

FUNCTIONAL (CONTEXTUAL) APPROACH

The supporters of this approach define meaning as the use of word in a language. They believe that meaning should be studied through contexts. If the distribution (position of a linguistic unit to other linguictic units) of two words is different we can conclude that heir meanings are different too (Ex. He looked at me in surprise; He’s been looking for him for a half an hour.)

However, it is hardly possible to collect all contexts for reliable conclusion. In practice a scholar is guided by his experience and intuition. On the whole, this approach may be called complimentary to the referential definition and is applied mainly in structural linguistics.

2. Classification of morphemes

A morpheme is the smallest indivisible two-facet language unit which implies an association of a certain meaning with a certain sound form. Unlike words, morphemes cannot function independently (they occur in speech only as parts of words).

Classification of Morphemes

Within the English word stock maybe distinguished morphologically segment-able and non-segment-able words (soundless, rewrite – segmentable; book, car — non-segmentable).

Morphemic segmentability may be of three types:

a) Complete segmentability is characteristic of words with transparent morphemic structure (morphemes can be easily isolated, e.g. heratless).

b) Conditional segmentability characterizes words segmentation of which into constituent morphemes is doubtful for semantic reasons (retain, detain, contain). Pseudo-morphemes

c) Defective morphemic segmentability is the property of words whose component morphemes seldom or never occur in other words. Such morphemes are called unique morphemes (cran – cranberry (клюква), let- hamlet (деревушка)).

· Semantically morphemes may be classified into: 1) root morphemes – radicals (remake, glassful, disorder — make, glass, order- are understood as the lexical centres of the words) and 2) non-root morphemes – include inflectional (carry only grammatical meaning and relevant only for the formation of word-forms) and affixational morphemes (relevant for building different types of stems).

· Structurally, morphemes fall into: free morphemes (coincides with the stem or a word-form. E.g. friend- of thenoun friendship is qualified as a free morpheme), bound morphemes (occurs only as a constituent part of a word. Affixes are bound for they always make part of a word. E.g. the suffixes –ness, -ship, -ize in the words darkness, friendship, to activize; the prefixes im-, dis-, de- in the words impolite, to disregard, to demobilize) and semi-free or semi-bound morphemes (can function both as affixes and free morphemes. E.g. well and half on the one hand coincide with the stem – to sleep well, half an hour, and on the other in the words – well-known, half-done).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 3

1. Types of meaning

The word «meaning» is not homogeneous. Its components are described as «types of meaning». The two main types of meaning are grammatical and lexical meaning.

The grammatical meaning is the component of meaning, recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of words (e.g. reads, draws, writes – 3d person, singular; books, boys – plurality; boy’s, father’s – possessive case).

The lexical meaning is the meaning proper to the linguistic unit in all its forms and distribution (e.g. boy, boys, boy’s, boys’ – grammatical meaning and case are different but in all of them we find the semantic component «male child»).

Both grammatical meaning and lexical meaning make up the word meaning and neither of them can exist without the other.

There’s also the 3d type: lexico-grammatical (part of speech) meaning. Third type of meaning is called lexico-grammatical meaning (or part-of-speech meaning). It is a common denominator of all the meanings of words belonging to a lexical-grammatical class (nouns, verbs, adjectives etc. – all nouns have common meaning oа thingness, while all verbs express process or state).

Denotational meaning – component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible. The second component of the lexical meaning is the connotational component – the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word.

2. Syntactic structure and pattern of word-groups

The meaning of word groups can be defined as the combined lexical meaning of the component words but it is not a mere additive result of all the lexical meanings of components. The meaning of the word group itself dominates the meaning of the component members (Ex. an easy rule, an easy person).

The meaning of the word group is further complicated by the pattern of arrangement of its constituents (Ex. school grammar- grammar school).

That’s why we should bear in mind the existence of lexical and structural components of meaning in word groups, since these components are independent and inseparable. The syntactic structure (formula) implies the description of the order and arrangement of member-words as parts of speech («to write novels» — verb + noun; «clever at mathematics»- adjective + preposition + noun).

As a rule, the difference in the meaning of the head word is presupposed by the difference in the pattern of the word group in which the word is used (to get + noun = to get letters / presents; to get + to + noun = to get to town). If there are different patterns, there are different meanings. BUT: identity of patterns doesn’t imply identity of meanings.

Semanticallv. English word groups are analyzed into motivated word groups and non-motivated word groups. Word groups are lexically motivated if their meanings are deducible from the meanings of components. The degree of motivation may be different.

A blind man — completely motivated

A blind print — the degree of motivation is lower

A blind alley (= the deadlock) — the degree of motivation is still less.

Non-motivated word-groups are usually described as phraseological units.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 4

1. Classification of phraseological units

The term «phraseological unit» was introduced by Soviet linguist (Виноградов) and it’s generally accepted in this country. It is aimed at avoiding ambiguity with other terms, which are generated by different approaches, are partially motivated and non-motivated.

The first classification of phraseological units was advanced for the Russian language by a famous Russian linguist Виноградов. According to the degree of idiomaticity phraseological units can be classified into three big groups: phraseological collocations (сочетания), phraseological unities (единства) and phraseological fusions (сращения).

Phraseological collocations are not motivated but contain one component used in its direct meaning, while the other is used metaphorically (e.g. to break the news, to attain success).

Phraseological unities are completely motivated as their meaning is transparent though it is transferred (e.g. to shoe one’s teeth, the last drop, to bend the knee).

Phraseological fusions are completely non-motivated and stable (e.g. a mare’s nest (путаница, неразбериха; nonsense), tit-for-tat – revenge, white elephant – expensive but useless).

But this classification doesn’t take into account the structural characteristic, besides it is rather subjective.

Prof. Смирнитский treats phraseological units as word’s equivalents and groups them into: (a) one-summit units => they have one meaningful component (to be tied, to make out); (b) multi-summit units => have two or more meaningful components (black art, to fish in troubled waters).

Within each of these groups he classifies phraseological units according to the part of speech of the summit constituent. He also distinguishes proper phraseological units or units with non-figurative meaning and idioms that have transferred meaning based on metaphor (e.g. to fall in love; to wash one’s dirty linen in public).

This classification was criticized as inconsistent, because it contradicts the principle of idiomaticity advanced by the linguist himself. The inclusion of phrasal verbs into phraseology wasn’t supported by any convincing argument.

Prof. Амазова worked out the so-called contextual approach. She believes that if 3 word groups make up a variable context. Phraseological units make up the so-called fixed context and they are subdivided into phrases and idioms.

2. Procedure of morphemic analysis

Morphemic analysis deals with segmentable words. Its procedure flows to split a word into its constituent morphemes, and helps to determine their number and type. It’s called the method of immediate and ultimate constituents. This method is based on the binary principle which allows to break morphemic structure of a word into 2 components at each stage. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents unable of any further division. E.g. Louis Bloomfield — classical example:

ungentlemanly

I. un-(IC/UC) +gentlemanly (IC) (uncertain, unhappy)

II. gentleman (IC) + -ly (IC/UC) (happily, certainly)

III. gentle (IC) +man (IC/UC) (sportsman, seaman)

IV. gent (IC/UC) + le (IC/UC) (gentile, genteel)

The aim of the analysis is to define the number and the type of morphemes.

As we break the word we obtain at any level only 2 immediate constituents, one of which is the stem of the given word. The morphemic analysis may be based either on the identification of affixational morphemes within a set of words, or root morphemes.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 5

1. Causes, nature and results of semantic change

The set of meanings the word possesses isn’t fixed. If approached diachronically, the polysemy reflects sources and types of semantic changes. The causes of such changes may be either extra-linguistic including historical and social factors, foreign influence and the need for a new name, or linguistic, which are due to the associations that words acquire in speech (e.g. «atom» has a Greek origin, now is used in physics; «to engage» in the meaning «to invite» appeared in English due to French influence = > to engage for a dance). To unleash war – развязать войну – but originally – to unleash dogs)

The nature of semantic changes may be of two main types: 1) Similarity of meaning (metaphor). It implies a hidden comparison (bitter style – likeness of meaning or metonymy). It is the process of associating two references, one of which is part of the other, or is closely connected with it. In other words, it is nearest in type, space or function (e.g. «table» in the meaning of “food” or “furniture” [metonymy]).

The semantic change may bring about following results: 1. narrowing of meaning (e.g. “success” – was used to denote any kind of result, but today it is onle “good results”);

2. widening of meaning (e.g. “ready” in Old English was derived from “ridan” which went to “ride” – ready for a ride; but today there are lots of meanings),

3. degeneration of meaning — acquisition by a word of some derogatory or negative emotive charge (e.g. «villain» was borrowed from French “farm servant”; but today it means “a wicked person”).

4. amelioration of meaning — acquisition by a word of some positive emotive charge (e.g. «kwen» in Old English meant «a woman» but in Modern English it is «queen»).

It is obvious that 3, 4 result illustrate the change in both denotational and connotational meaning. 1, 2 change in the denotational.

The change of meaning can also be expressed through a change in the number and arrangement of word meanings without any other changes in the semantic structure of a word.

2. Productivity of word-formation means

According to Смирницкий, word-formation is the system of derivative types of words and the process of creating new words from the material available in the language. Words are formed after certain structural and semantic patterns. The main two types of word-formation are: word-derivation and word-composition (compounding).

The degree of productivity of word-formation and factors that favor it make an important aspect of synchronic description of every derivational pattern within the two types of word-formation. The two general restrictions imposed on the derivational patterns are: 1. the part of speech in which the pattern functions; 2. the meaning which is attached to it.

Three degrees of productivity are distinguished for derivational patterns and individual derivational affixes: highly productive, productive or semi-productive and non-productive.

Productivity of derivational patterns and affixes shouldn’t be identified with frequency of occurrence in speech (e.g.-er — worker, -ful – beautiful are active suffixes because they are very frequently used. But if -er is productive, it is actively used to form new words, while -ful is non-productive since no new words are built).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 6

1. Morphological, phonetical and semantic motivation

A new meaning of a word is always motivated. Motivation — is the connection between the form of the word (i.e. its phonetic, morphological composition and structural pattern) and its meaning. Therefore a word may be motivated phonetically, morphologically and semantically.

Phonetically motivated words are not numerous. They imitate the sounds (e.g. crash, buzz, ring). Or sometimes they imitate quick movement (e.g. rain, swing).

Morphological motivation is expressed through the relationship of morphemes => all one-morpheme words aren’t motivated. The words like «matter» are called non-motivated or idiomatic while the words like «cranberry» are partially motivated because structurally they are transparent, but «cran» is devoid of lexical meaning; «berry» has its lexical meaning.

Semantic motivation is the relationship between the direct meaning of the word and other co-existing meanings or lexico-semantic variants within the semantic structure of a polysemantic word (e.g. «root»— «roots of evil» — motivated by its direct meaning, «the fruits of peace» — is the result).

Motivation is a historical category and it may fade or completely disappear in the course of years.

2. Classification of compounds

The meaning of a compound word is made up of two components: structural meaning of a compound and lexical meaning of its constituents.

Compound words can be classified according to different principles.

1. According to the relations between the ICs compound words fall into two classes: 1) coordinative compounds and 2) subordinative compounds.

In coordinative compounds the two ICs are semantically equally important. The coordinative compounds fall into three groups:

a) reduplicative compounds which are made up by the repetition of the same base, e.g. pooh-pooh (пренебрегать), fifty-fifty;

b) compounds formed by joining the phonically variated rhythmic twin forms, e.g. chit-chat, zig-zag (with the same initial consonants but different vowels); walkie-talkie (рация), clap-trap (чепуха) (with different initial consonants but the same vowels);

c) additive compounds which are built on stems of the independently functioning words of the same part of speech, e.g. actor-manager, queen-bee.

In subordinative compounds the components are neither structurally nor semantically equal in importance but are based on the domination of the head-member which is, as a rule, the second IС, e.g. stone-deaf, age-long. The second IС preconditions the part-of-speech meaning of the whole compound.

2. According to the part of speech compounds represent they fall into:

1) compound nouns, e.g. sunbeam, maidservant;

2) compound adjectives, e.g. heart-free, far-reaching;

3) compound pronouns, e.g. somebody, nothing;

4) compound adverbs, e.g. nowhere, inside;

5) compound verbs, e.g. to offset, to bypass, to mass-produce.

From the diachronic point of view many compound verbs of the present-day language are treated not as compound verbs proper but as polymorphic verbs of secondary derivation. They are termed pseudo-compounds and are represented by two groups: a) verbs formed by means of conversion from the stems of compound nouns, e.g. to spotlight (from spotlight); b) verbs formed by back-derivation from the stems of compound nouns, e.g. to babysit (from baby-sitter).

However synchronically compound verbs correspond to the definition of a compound as a word consisting of two free stems and functioning in the sentence as a separate lexical unit. Thus, it seems logical to consider such words as compounds by right of their structure.

3. According to the means of composition compound words are classified into:

1) compounds composed without connecting elements, e.g. heartache, dog-house;

2)compounds composed with the help of a vowel or a consonant as a linking element, e.g. handicraft, speedometer, statesman;

3) compounds composed with the help of linking elements represented by preposition or conjunction stems, e.g. son-in-law, pepper-and-salt.

4. According to the type of bases that form compounds the following classes can be singled out:

1) compounds proper that are formed by joining together bases built on the stems or on the word-forms with or without a linking element, e.g. door-step, street-fighting;

2) derivational compounds that are formed by joining affixes to the bases built on the word-groups or by converting the bases built on the word-groups into other parts of speech, e.g. long-legged —> (long legs) + -ed; a turnkey —> (to turn key) + conversion. Thus, derivational compounds fall into two groups: a) derivational compounds mainly formed with the help of the suffixes -ed and -er applied to bases built, as a rule, on attributive phrases, e.g. narrow-minded, doll-faced, lefthander; b) derivational compounds formed by conversion applied to bases built, as a rule, on three types of phrases — verbal-adverbial phrases (a breakdown), verbal-nominal phrases (a kill-joy) and attributive phrases (a sweet-tooth).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 7

1. Diachronic and synchronic approaches to polysemy

Diachronically, polysemy is understood as the growth and development of the semantic structure of the word. Historically we differentiate between the primary and secondary meanings of words.

The relation between these meanings isn’t only the one of order of appearance but it is also the relation of dependence = > we can say that secondary meaning is always the derived meaning (e.g. dog – 1. animal, 2. despicable person)

Synchronically it is possible to distinguish between major meaning of the word and its minor meanings. However it is often hard to grade individual meaning of the word in order of their comparative value (e.g. to get the letter — получить письмо; to get to London — прибыть в Лондон — minor).

The only more or less objective criterion in this case is the frequency of occurrence in speech (e.g. table – 1. furniture, 2. food). The semantic structure is never static and the primary meaning of a word may become synchronically one of the minor meanings and vice versa. Stylistic factors should always be taken into consideration

Polysemy of words: «yellow»- sensational (Am., sl.)

The meaning which has the highest frequency is the one representative of the whole semantic structure of the word. The Russian equivalent of «a table» which first comes to your mind and when you hear this word is ‘cтол» in the meaning «a piece of furniture». And words that correspond in their major meanings in two different languages are referred to as correlated words though their semantic structures may be different.

Primary meaning — historically first.

Major meaning — the most frequently used meaning of the word synchronically.

2. Typical semantic relations between words in conversion pairs

We can single out the following typical semantic relation in conversion pairs:

1) Verbs converted from nouns (denominal verbs):

a) Actions characteristic of the subject (e.g. ape – to ape – imitate in a foolish way);

b) Instrumental use of the object (e.g. whip — to whip – strike with a whip);

c) Acquisition or addition of the objects (e.g. fish — to fish — to catch fish);

d) Deprivation of the object (e.g. dust — to dust – remove dust).

2) Nouns converted from verbs (deverbal nouns):

a) Instance of the action (e.g. to move — a move = change of position);

b) Agent of an action (e.g. to cheat — a cheat – a person who cheats);

c) Place of the action (e.g. to walk-a walk – a place for walking);

d) Object or result of the action (e.g. to find- a find – something found).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 8

1. Classification of homonyms

Homonyms are words that are identical in their sound-form or spelling but different in meaning and distribution.

1) Homonyms proper are words similar in their sound-form and graphic but different in meaning (e.g. «a ball»- a round object for playing; «a ball»- a meeting for dances).

2) Homophones are words similar in their sound-form but different in spelling and meaning (e.g. «peace» — «piece», «sight»- «site»).

3) Homographs are words which have similar spelling but different sound-form and meaning (e.g. «a row» [rau]- «a quarrel»; «a row» [rəu] — «a number of persons or things in a more or less straight line»)

There is another classification by Смирницкий. According to the type of meaning in which homonyms differ, homonyms proper can be classified into:

I. Lexical homonyms — different in lexical meaning (e.g. «ball»);

II. Lexical-grammatical homonyms which differ in lexical-grammatical meanings (e.g. «a seal» — тюлень, «to seal» — запечатывать).

III. Grammatical homonyms which differ in grammatical meaning only (e.g. «used» — Past Indefinite, «used»- Past Participle; «pupils»- the meaning of plurality, «pupil’s»- the meaning of possessive case).

All cases of homonymy may be subdivided into full and partial homonymy. If words are identical in all their forms, they are full homonyms (e.g. «ball»-«ball»). But: «a seal» — «to seal» have only two homonymous forms, hence, they are partial homonyms.

2. Classification of prefixes