From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The naming of the Americas, or America, occurred shortly after Christopher Columbus’s first voyage to the Americas in 1492. It is generally accepted that the name derives from Amerigo Vespucci, the Italian explorer, who explored the new continents in the following years on behalf of Spain and Portugal. However, some have suggested other explanations, including being named after the Amerrisque mountain range in Nicaragua, or after Richard Amerike, a merchant from Bristol, England.

Usage[edit]

In modern English, North and South America are generally considered separate continents, and taken together are called the Americas in the plural, parallel to similar situations such as the Carolinas and the Dakotas. When conceived as a unitary continent, the form is generally the continent of America in the singular. However, without a clarifying context, singular America in English commonly refers to the United States of America.[1]

Historically, in the English-speaking world, the term America used to refer to a single continent until the 1950s (as in Van Loon’s Geography of 1937): According to historians Kären Wigen and Martin W. Lewis,[2]

While it might seem surprising to find North and South America still joined into a single continent in a book published in the United States in 1937, such a notion remained fairly common until World War II. It cannot be coincidental that this idea served American geopolitical designs at the time, which sought both Western Hemispheric domination and disengagement from the «Old World» continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa. By the 1950s, however, virtually all American geographers had come to insist that the visually distinct landmasses of North and South America deserved separate designations.

This shift did not seem to happen in most other cultural hemispheres on Earth, such as Romance-speaking (including France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Romania, Switzerland, and the postcolonial Romance-speaking countries of Latin America and Africa), Germanic (but excluding English) speaking (including Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, The Netherlands, Luxembourg, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands), Baltic-Slavic languages (including Czechia, Slovakia, Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, Russia, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria) and elsewhere, where America is still considered a continent encompassing the North America and South America subcontinents,[3][4] as well as Central America.[5][6][7][8][9][10]

Earliest use of name[edit]

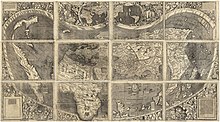

World map of Waldseemüller (Germany, 1507), which first used the name America (in the lower-left section, over South America)[11]

The earliest known use of the name America dates to April 25, 1507, when it was applied to what is now known as South America.[11] It appears on a small globe map with twelve time zones, together with the largest wall map made to date, both created by the German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller in Saint-Dié-des-Vosges in France.[12] These were the first maps to show the Americas as a land mass separate from Asia. An accompanying book, Cosmographiae Introductio, anonymous but apparently written by Waldseemüller’s collaborator Matthias Ringmann,[13] states, «I do not see what right any one would have to object to calling this part [that is, the South American mainland], after Americus who discovered it and who is a man of intelligence, Amerigen, that is, the Land of Americus, or America: since both Europa and Asia got their names from women». America is also inscribed on the Paris Green Globe (or Globe vert) which has been attributed to Waldseemüller and dated to 1506–07: as well as the single name inscribed on the northern and southern parts of the New World, the continent also bears the inscription: America ab inuentore nuncupata (America, named after its discoverer).[14]

Mercator on his map called North America «America or New India» (America sive India Nova).[15]

America ab inventore nuncupata (America, called after its discoverer) on the Globe vert, c. 1507

Amerigo Vespucci[edit]

Americus Vesputius was the Latinized version of the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci’s name, the forename being an old Italianization (compare modern Italian Enrico) of Medieval Latin Emericus (see Saint Emeric of Hungary), from the Old High German name Emmerich, which may have been a merger of several Germanic names – Amalric, Ermanaric and Old High German Haimirich, from Proto-Germanic *amala- (‘vigor, bravery’), *ermuna- (‘great; whole’) or *haima- (‘home’) + *rīk- (‘ruler’) (compare *Haimarīks).[16][better source needed]

Amerigo Vespucci (March 9, 1454 – February 22, 1512) was an Italian explorer, financier, navigator and cartographer who may have been the first to assert that the West Indies and corresponding mainland were not part of Asia’s eastern outskirts as initially conjectured from Columbus’s voyages, but instead constituted an entirely separate landmass hitherto unknown to the Europeans.[17][18]

Vespucci was apparently unaware of the use of his name to refer to the new landmass, as Waldseemüller’s maps did not reach Spain until a few years after his death.[13] Ringmann may have been misled into crediting Vespucci by the widely published Soderini Letter, a sensationalized version of one of Vespucci’s actual letters reporting on the mapping of the South American coast, which glamorized his discoveries and implied that he had recognized that South America was a continent separate from Asia.[19] Spain officially refused to accept the name America for two centuries, saying that Columbus should get credit, and Waldseemüller’s later maps, after Ringmann’s death, did not include it; in 1513 he labelled it «Terra Incognita» with a note about Columbus’s discovery of the land.[20]

Following Waldseemüller, the Swiss scholar Heinrich Glarean included the name America in a 1528 work of geography published in Basel. There, four years later, the German scholar Simon Grinaeus published a map, which Hans Holbein and Sebastian Münster (who had made sketches of Waldseemüller’s 1507 map) contributed to; this labelled the continent America Terra Nova (America, the New Land). In 1534, Joachim von Watt labelled it simply America.[20] Gerardus Mercator applied the names North and South America on his influential 1538 world map; by this point, the naming was irrevocable.[20] Acceptance may have been aided by the «natural poetic counterpart» that the name America made with Asia, Africa, and Europa.[13]

Named after a Nicaraguan mountain range[edit]

In 1874, Thomas Belt published the indigenous name of the Amerrisque Mountains in present-day Nicaragua.[21] The next year, Jules Marcou suggested a derivation of the continent’s name from this mountain range.[22] Marcou corresponded with Augustus Le Plongeon, who wrote: «The name AMERICA or AMERRIQUE in the Mayan language means, a country of perpetually strong wind, or the Land of the Wind, and … the [suffixes] can mean … a spirit that breathes, life itself.»[23]

In this view, native speakers shared this indigenous word with Columbus and members of his crew, and Columbus made landfall in the vicinity of these mountains on his fourth voyage.[22][23] The name America then spread via oral means throughout Europe relatively quickly even reaching Waldseemüller, who was preparing a map of newly reported lands for publication in 1507.[23] Waldseemüller’s work in the area of denomination takes on a different aspect in this view. Jonathan Cohen of Stony Brook University writes:

The baptismal passage in the Cosmographiae Introductio has commonly been read as argument, in which the author said that he was naming the newly discovered continent in honor of Vespucci and saw no reason for objections. But, as etymologist Joy Rea has suggested, it could also be read as an explanation, in which he indicates that he has heard the New World was called America, and the only explanation lay in Vespucci’s name.[23]

Among the reasons which proponents give in adopting this theory include the recognition of, in Cohen’s words, «the simple fact that place names usually originate informally in the spoken word and first circulate that way, not in the printed word».[23][24] In addition, Waldseemüller not only is exonerated from the charge of having arrogated to himself the privilege of naming lands, which privilege was reserved to monarchs and explorers, but also is freed from the charge of violating the long-established and virtually inviolable ancient European tradition of using only the first name of royal individuals as opposed to the last name of commoners (such as Vespucci) in bestowing names to lands.[22]

Richard Amerike[edit]

Bristol antiquarian Alfred Hudd suggested in 1908 that the name was derived from the surname «Amerike» or «ap Meryk» and was used on early British maps that have since been lost. Richard ap Meryk, anglicised to Richard Amerike (or Ameryk) (c. 1445–1503) was a wealthy Anglo-Welsh merchant, royal customs officer and sheriff of Bristol.[25] According to some historians, he was the principal owner of the Matthew, the ship sailed by John Cabot during his voyage of exploration to North America in 1497.[25] The idea that Richard Amerike was a ‘principal supporter’ of Cabot has gained popular currency in the 21st century.[25] There is no known evidence to support this.[citation needed] Similarly, and contrary to a recent tradition that names Amerike as principal owner and main funder of the Matthew, Cabot’s ship of 1497,[25] academic enquiry does not connect Amerike with the ship. Her ownership at that date remains uncertain.[26] Macdonald asserts that the caravel was specifically built for the Atlantic crossing.[27]

Hudd proposed his theory in a paper which was read at the 21 May 1908 meeting of the Clifton Antiquarian Club, and which appeared in Volume 7 of the club’s Proceedings. In «Richard Ameryk and the name America,» Hudd discussed the 1497 discovery of North America by John Cabot, an Italian who had sailed on behalf of England. Upon his return to England after his first (1497) and second (1498–1499) voyages, Cabot received two pension payments from Henry VII. Of the two customs officials at the Port of Bristol who were responsible for delivering the money to Cabot, the more senior was Richard Ameryk (High Sheriff of Bristol in 1503).[23][28] Hudd postulated that Cabot named the land that he had discovered after Ameryk, from whom he received the pension conferred by the king.[29] He stated that Cabot had a reputation for being free with gifts to his friends, such that his expression of gratitude to the official would not be unexpected. Hudd also thought it unlikely that America would have been named after Vespucci’s given name rather than his family name. Hudd used a quote from a late 15th-century manuscript (a calendar of Bristol events), the original of which had been lost in an 1860 Bristol fire, that indicated the name America was already known in Bristol in 1497.[23][30]

This year (1497), on St. John the Baptist’s day (June 24th), the land of America was found by the merchants of Bristow, in a ship of Bristowe called the ‘Mathew,’ the which said ship departed from the port of Bristowe the 2nd of May and came home again the 6th August following.[30]

Hudd reasoned that the scholars of the 1507 Cosmographiae Introductio, unfamiliar with Richard Ameryk, assumed that the name America, which he claimed had been in use for ten years, was based on Amerigo Vespucci and, therefore, mistakenly transferred the honour from Ameryk to Vespucci.[23][30] While Hudd’s speculation has found support from some authors, there is no strong evidence to substantiate his theory that Cabot named America after Richard Ameryk.[23][25][31]

Moreover, because Amerike’s coat of arms was similar to the flag later adopted by the independent United States, a legend grew that the North American continent had been named for him rather than for Amerigo Vespucci.[25] It is not widely accepted — the origin is usually attributed to the flag of the British East India Company.

Native naming of the continent[edit]

In 1977, the World Council of Indigenous Peoples (Consejo Mundial de Pueblos Indígenas) proposed using the term Abya Yala instead of «America» when referring to the continent. There are also names in other indigenous languages such as Ixachitlan and Runa Pacha. Some scholars have adopted the term as an objection to colonialism.[32]

References[edit]

- ^ «America.» The Oxford Companion to the English Language (ISBN 0-19-214183-X). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 33: «[16c: from the feminine of Americus, the Latinized first name of the explorer Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512). The name America first appeared on a map in 1507 by the German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, referring to the area now called Brazil]. Since the 16c, a name of the western hemisphere, often in the plural Americas and more or less synonymous with the New World. Since the 18c, a name of the United States of America. The second sense is now primary in English … However, the term is open to uncertainties.»

- ^ «The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography (Chapter 1)». University of California Press. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ «The Continents of the World». nationsonline.org. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

Africa, the Americas, Antarctica, Asia, Australia together with Oceania, and Europe are considered to be Continents.

- ^ «Map And Details Of All 7 Continents». worldatlas.com. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

In some parts of the world students are taught that there are only six continents, as they combine North America and South America into one continent called the Americas.

- ^ «CENTRAL AMERICA». central-america.org. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

Central America is not a continent but a subcontinent since it lies within the continent America.

- ^ «Six or Seven Continents on Earth». Retrieved December 18, 2016. «In Europe and other parts of the world, many students are taught of six continents, where North and South America are combined to form a single continent of America. Thus, these six continents are Africa, America, Antarctica, Asia, Australia, and Europe.»

- ^ «Continents». Retrieved December 18, 2016. «six-continent model (used mostly in France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Romania, Greece, and Latin America) groups together North America+South America into the single continent America.»

- ^ «AMÉRIQUE» (in French). Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ^ «America» (in Italian). Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ^ «Amerika». Duden (in German). Berlin, Germany: Bibliographisches Institut GmbH. Retrieved 2019-08-19.

- ^ a b «Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii alioru[m]que lustrationes». Archived from the original on January 9, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2014.

- ^ Martin Waldseemüller. «Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii alioru[m]que lustrationes». Washington, DC: Library of Congress. LCCN 2003626426. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c Toby Lester, December (2009). «Putting America on the Map». Smithsonian. 40: 9.

- ^ Monique Pelletier, «Le Globe vert et l’oeuvre cosmographique du Gymnase Vosgien”, Bulletin du Comité français de cartographie, 163, 2000, pp. 17-31.[1] Archived 2020-09-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Mercator 1587 | Envisioning the World | The First Printed Maps». lib-dbserver.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2020-09-12.

- ^ Harrison, Henry (8 February 2017). Surnames of the United Kingdom: A Concise Etymological Dictionary. Genealogical Publishing Com. ISBN 9780806301716.

- ^ Davidson, M. H. (1997). Columbus Then and Now: A Life Re-examined. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 417.

- ^ «Szalay, Jessie. Amerigo Vespuggi: Facts, Biography & Naming of America (citing Erika Cosme of Mariners Museum & Park, Newport News VA). 20 September 2017 (accessed 23 June 2019)». Live Science. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ «UK | Magazine | The map that changed the world». BBC News. October 28, 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2007). Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America (1st ed.). New York: Random House. pp. 186–187. ISBN 978-1400062812. OCLC 608082366.

- ^ Marcou, Jules (1890). «Amerriques, Ameriggo Vespucci, and America». Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (PDF). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 647.

- ^ a b c Marcou, Jules (March 1875). «Origin of the Name America». The Atlantic Monthly: 291–295. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cohen, Jonathan. «The Naming of America: Fragments We’ve Shored Against Ourselves». Stony Brook University. Archived from the original on 7 June 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Rea, Joy (1 January 1964). «On the Naming of America». American Speech. 39 (1): 42–50. doi:10.2307/453925. JSTOR 453925.

- ^ a b c d e f Macdonald, Peter (17 February 2011). «BBC History in Depth; The Naming of America; Richard Amerike». BBC History website. BBC. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Evan T. Jones, «The Matthew of Bristol and the financiers of John Cabot’s 1497 voyage to North America», English Historical Review (2006)

- ^ Macdonald, Peter (1997), Cabot & the Naming of America, Bristol: Petmac Publications, p. 29, ISBN 0-9527009-2-1

- ^ Macdonald 1997, p. 46

- ^ Macdonald 1997, p. 33

- ^ a b c Alfred E. Hudd, F.S.A., Hon. Secretary. «Richard Ameryk and the name America» (PDF). Proceedings of the Clifton Antiquarian Club. VII: 8–24. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Quinn, David B. (1990). Explorers and Colonies: America, 1500–1625. A&C Black. p. 398. ISBN 9781852850241. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Julia Roth. Latein/Amerika, in: Susan Arndt and Nadja Ofuatey-Alazard: Wie Rassismus aus Wörtern spricht. Unrast-Verlag.

Bibliography[edit]

- The Columbus Myth: Did Men of Bristol Reach America before Columbus? Ian Wilson (1974; reprint 1991: ISBN 0-671-71167-9)

- Terra Incognita: The True Story of How America Got Its Name, Rodney Broome (US 2001: ISBN 0-944638-22-8)

- Amerike: The Briton America Is Named After, Rodney Broome (UK 2002: ISBN 0-7509-2909-X)

External links[edit]

- «The man who inspired America?», BBC Features, 29 April 2002

- Jonathan Cohen, «It’s All in a Name», Bristol Times

- «Bristol Voyages», Heritage

- «Correcting One of History’s Mistakes…Maybe», Peninsula Pulse, 12 September 2013

Wiki User

∙ 13y ago

Best Answer

Copy

Yes, the word ‘America’ is thought to honor Amerigo Vespucci [March 9, 1454-February 22, 1512]. Vespucci put his considerable skills as navigator, explorer, and cartographer to good use in voyages to the New World. It’s thought that the name ‘America’ represents the feminine version of Vespucci’s name in Latin, ‘Americus’.

Wiki User

∙ 13y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: Is the word ‘America’ taken from the Italian language?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

| Categories | |

|

Nooks and crannies |

|

|

Yesteryear |

|

|

Semantic enigmas |

|

|

The body beautiful |

|

|

Red tape, white lies |

|

|

Speculative science |

|

|

This sceptred isle |

|

|

Root of all evil |

|

|

Ethical conundrums |

|

|

This sporting life |

|

|

Stage and screen |

|

|

Birds and the bees |

|

YESTERYEAR

Just how did America get to be named after Amerigo Vespucci, who was fairly obscure? I understand that it may have been a blunder by an early map-maker.

Geoffrey C. Bobker, London

- There’s no conclusive evidence, just several contending (and contentious) theories, but it seems unlikely that the two continents are named after Vespucci (after all, it would be Vespucia, or Ameriga, wouldn’t it?) The most convincing theory I’ve heard (on the purely subjective grounds that I used to live in Bristol) is that the land mass was named by John Cabot after Dafydd ap Meric (anglicised to David Merrick), who has been variously described as his mapmaker, or his financial backer. Take your pick. There’s probably plenty more theories to come on this one …

Mark Power, Dublin

- Amerigo Vespucci was a navigator who made at least two voyages to the Americas, the first time in 1499. He was probably the first to realize that a new continent had been discobvered, not just the coast of Asia.

Vespucci published two letters in 1503/1504 in which he described his voyages, and entitled Novus Mundus (thus coining the term «the New World»). The letters were a sensation, and were reprinted in every European language. Waldseemueller, the publisher of the «Introduction to Cosmography», was so impressed that he decided to name the new land America in Vespucci’s honour.Richard Thompson, Allerod Denmark

- Columbus was disgraced by the Spanish court for, amongst other things, his sympathetic treatment of the natives of the New World, and Vespucci, who succeeded where Columbus had failed by finding the mainland, was glorified as the «discoverer» of the Americas. It was only long after his death that Columbus was finally acknowledged as the first European to cross the Atlantic. Of course, the Irish Saint Breandán had already sailed to North America in the 6th Century, and the Vikings are believed to have settled in Canada, which they called Vinland, a few centuries later, so the Italians were certainly not the first Europeans to achieve this feat.

Peadar Mac Con Aonaigh, Brixton, London

- I read somewhere that he happened to discover the land

and the map makers needed a name.Who cares if he was «obscure» whatever that means. I am sure that the people of the USA would have quickly changed it if they had not been contented.Jack Hill, St Albans England UK

- Why does Peadar Mac Con Aonaigh say «Of course» an Irish Saint had already got to America, while the Vikings are only «believed» to have done so? The evidence for the former is somewhat thin to say the least, while for the latter there are at least two written historical records backed up with hard archaeological evidence.

Tom Booth, Hampstead Norreys UK

- Not only was America named for Cabot’s sponsor, Richard Amerike/Ap Meryk but aparently the ‘stars and stripes’ flag is taken from his coat of arms!

For details see…

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/discovery/exploration/naming_04.shtml

Mark Dallas, London

- According to a book that I have been reading entitled The Island of Lost Maps by Miles Harvey I am reasonably sure this is the correct answer. In 1507 the cartographer, Martin Waldseemuller made one of the

first maps to depict the «New

World» and he was under the

mistaken impression that

Amerigo Vespucci had discovered

the the land mass and so he named

the southern part of the

continent, «America»,he later on found out about his error

and deleted Vespucci’s name from his further editions,but by that time the name «America» had stuck to the whole continent so it was too late to change that name.Ray Sinclair, Pickering Ontario Canada

- According to a book that I have been reading entitled

«The Island of Lost Maps»

by Miles Harvey,and I am reasonably sure this is the correct answer. In 1507 the cartographer, Martin Waldseemuller made one of the

first maps to depict the «New

World» and he was under the

mistaken impression that

Amerigo Vespucci had discovered

the the land mass and so he named

the southern part of the

continent, «America»,he later on found out about his error

and deleted Vespucci’s name from his further editions,but by that time the name «America» had stuck to the whole continent so it was too late to change that name.Ray Sinclair, Pickering.Ontario Canada

- A Florentine businessman who moved to Seville, where he ran a ship supply busines (Incidentally supplying one for Cristophe Colon — Columbus) he visited the new world only three or four times as a lowly officer or passenger. He was not an accomplished seaman. However, in 1504-5 letters of unknown authorship began circulating in Florence stating that Vespucci had been Captain of voyages to the new world. The mistake would have gone no further except that an instructor at a small college in eastern France — Martin Waldseemuller — was working on a revised edition of Ptolemy and updated it with a new map of the world. He came across the letters with the spurious account of Vespucci’s exploits and named the continent in his honour. First translating Amerigo into the Latin ‘Americus’ and then into its feminine form (as with Europe and Asia) America.

Interestingly Vespucci is thought to have been the brother of Simonetti Vespucci — Boticelli’s Venus!!All of this is taken from ‘Made in America’ by Bill Bryson.

Ben Roome, London

- Regarding the question, «why not Vespucia, then?» It was common in Italy in those days to refer to famous people by their first names such as Dante, Petrarch, Michealangelo, etc. It was also common to use the Latin form of the name, especially since most documents were in Latin. Americus is Latin for the Italian Amerigo.

Angel Herrera, New York, USA

- Regarding the above, although throughout Europe family names were not universally used in the medieval period Amerigo Vespucci is not an example of someone known only by his first name. There is no reason why anything named after him would not be called ‘Vespuccia’, and every reason to think that it should have been so named, as place names are derived from the latin form of the surname, never the first name.

Philip, Cambridge, UK

- If America wasn’t named after Amerigo, than where would it have come from? Maybe it was the «Amerigo’s» at first, but over time, cultural contamination and time could have warped it to America. either way, it isn’t like we can ask him, is it?

Vlad, Golden, Colorado

- According to both Columbus and Vespucci, they had found a country, more thickly populated by people and animals than their Europe, Asia, or Africa. Is it not probable then that these lands were already named by the inhabitants thereof? From the records of those natives in the POPOL VUH; no other sacred book of these people sets forth so completely as the Popol Vuh the initiatory rituals of a great school of mystical philosophy, and this volume alone is sufficient to establish incontestably the philosophical excellence of the red race, that these red, «Children of the Sun», adore the plumed serpent, who is the messenger of the Sun. He was the God, QUETZALCOATL to the Aztecs, GUCAMATZ to the Mayans, and AMARU to the Incas. And from the latter name comes our word America. Amruca is, literally translated, «Land of the Plumed Serpent». Map makers are known to have stirred up quite a mischeif from time to time but not in this case. It is from the original native language.

Lindy Cotner, Fort Smith USA

- I believe the story as told above: that the map-making and naming process was bungled; i.e., that America was, in fact, named «America» to honour the funding source of Cabot — Richard «Amerike» (later changed to ‘Merriken’. But I am admittedly a bit prejudiced — he was an ‘ornament on my family tree’ and we are related. One of my earliest documented, born in America, ancestors was «Anna Merriken» (born in Maryland, near Annapolis). Nathaniel Stinchcomb married (2) Anna Merriken January 03, 1704/05 in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. She was born about 1670 in Anne Arundel County, Maryland.

See: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~stinchcomb/thomas.htmEugene B. Veek, Prescott, Arizona, USA

- I don’t think America was named after Amerigo Vespucci, because places are usually named after a person’s surname. I think America was named after Richard Amerike a wealthy English merchant who lived in the 15th Century.

Ian Beaveridge, Wigan England

- I don’t think America was named after Amerigo Vespucci, because places are usually named after a person’s surname. I think America was named after Richard Amerike a wealthy English merchant who lived in the 15th Century.

Ian Beaveridge, Wigan England

- America was named after an obscure star named Meric which is Arabic in origin. This star is highly significant to the occult elite.

Rachael Harding, Seattle U.S.

Add your answer

Chapter 14 do americans speak english or american?

In one of his stories Oscar Wilde said that the English «have really everything in common with America nowadays, except, of course, language.»

Bernard Shaw, on the contrary, seemed to hold a different opinion on the point, but he expressed it in such an ambiguous way that, if one gives it some thought, the idea is rather the same as that of Wilde. Shaw said that America and England are two great nations separated by the same language.

Of course, both these statements were meant as jokes, but the insistence on a certain difference of the language used in the United States of America to the language spoken in. England is emphasized quite seriously.

Viewed linguistically, the problem maybe put in this way: do the English and the Americans speak the same language or two different languages? Do the United States of America possess their own language?

The hypothesis of the so-called «American language» has had several champions and supporters, especially in the United States (H. L. Mencken. The American Language. N.-Y., 1957).

Yet, there are also other points of view. There are scholars who regard American English as one of the dialects of the English language. This theory can hardly be accepted because a dialect is usually opposed to the literary variety of the language whereas American English possesses a literary variety of its own. Other scholars label American English «a regional variety» of the English language.

Before accepting this point of view, though, it is necessary to find out whether or not American English, in its modern stage of development, possesses those characteristics which would support its status as an independent language.

A language is supposed to possess a vocabulary and a grammar system of its own. Let us try and see if American English can boast such.

Vocabulary of American English

It is quite true that the vocabulary used by American speakers, has distinctive features of its own. More than that: there are whole groups of words which belong to American vocabulary exclusively and constitute its specific feature. These words are called Americanisms.

The first group of such words may be described as historical Americanisms.

At the beginning of the 17th c. the first English migrants began arriving in America in search of new and better living conditions. It was then that English was first spoken on American soil, and it is but natural that it was spoken in its 17th c. form. For instance, the noun fall was still used by the first migrants in its old meaning «autumn», the verb to guess in the old meaning «to think», the adjective sick in the meaning «ill, unwell». In American usage these words still retain their old meanings whereas in British English their meanings have changed.

These and similar words, though the Americans and the English use them in different meanings, are nevertheless found both in American and in British vocabularies.

The second group of Americanisms includes words which one is not likely to discover in British vocabulary. They are specifically American, and we shall therefore call them proper Americanisms. The oldest 01 these were formed by the first migrants to the American continent and reflected, to a great extent, their attempts to cope with their new environment.

It should be remembered that America was called «The New World» not only because the migrants severed all connections with their old life. America was for them a truly new world in which everything was strikingly and bewilderingly different from what it had been in the Old Country (as they called England): the landscape, climate, trees and plants, birds and animals.

Therefore, from the very first, they were ;faced with a serious lack of words in their vocabulary with which to describe all these new and strange things. Gradually such words were formed. Here are some of them.

Backwoods («wooded, uninhabited districts»), cold snap («a sudden frost»), blue-grass («a sort of grass peculiar to North America»), blue-jack («a small American oak»), egg-plant («a plant with edible fruit»), sweet potato («a plant with sweet edible roots»), redbud («an American tree having small budlike pink flowers, the state tree of Oklahoma»), red cedar («an American coniferous tree with reddish fragrant wood»), cat-bird («a small North-American bird whose call resembles the mewing of a cat»), cat-fish («called so because of spines likened to a cat’s claws»), bull-frog («a huge frog producing sounds not unlike a bull’s roar»), sun-fish («a fish with a round flat golden body»).

If we consider all these words from the point of view of the «building materials» of which they are made we shall see that these are all familiarly English, even though the words themselves cannot be found in the vocabulary of British English. Yet, both the word-building pattern of composition (see Ch. 6) and the constituents of these compounds are easily recognized as essentially English.

Later proper Americanisms are represented by names of objects which are called differently in the

United States and in England. E. g. the British chemist’s is called drug store or druggist’s in the United States, the American word for sweets (Br.) is candy, luggage (Br.) is called baggage (Amer.), underground (Br.) is called subway (Amer.), lift (Br.) is called elevator (Amer.), railway (Br.) is called railroad (Amer.), carriage (Br.) is called car (Amer.), car (Br.) is called automobile (Amer.).

If historical Americanisms have retained their 17th-c. meanings (e. g. fall, п., mad, adj., sick, adj.), there are also words which, though they can be found both in English and in American vocabulary, have developed meanings characteristic of American usage. The noun date is used both in British and American English in the meanings «the time of some event»; «the day of the week or month»; «the year». On the basis of these meanings, in American English only, another meaning developed: an appointment for a particular time (transference based on contiguity: the day and time of an appointment > appointment itself).

* * *

American vocabulary is rich in borrowings. The principal groups of borrowed words are the same as were pointed out for English vocabulary (see Ch. 3). Yet, there are groups of specifically American borrowings which reflect the historical contacts of the Americans with other nations on the American continent.

These are, for instance, Spanish borrowings (e. g. ranch, sombrero, canyon, cinch), Negro borrowings (e. g. banjo) and, especially, Indian borrowings. The latter are rather numerous and have a peculiar flavour of their own: wigwam, squaw, canoe, moccasin, toboggan, caribou, tomahawk. There are also some translation-loans of Indian origin: pale-face (the name of the Indians for all white people), war path, war paint, pipe of peace, fire-water.

These words are used metaphorically in both American and British modern communication. A woman who is too heavily made up may be said to wear war paint, and a person may be warned against an enemy by: Take care: he is on the war path (i. e. he has hostile intentions).

Many of the names of places, rivers, lakes, even of states, are of Indian origin, and hold, in their very sound, faint echoes of the distant past of the continent. Such names as, for instance, Ohio [qV`haiqV], Michigan [`mISIgqn], Tennessee [tene`sJ], Illinois [IlI`noI(s)], Kentucky [ken`tAkI] sound exotic and romantic. These names awake dim memories of those olden times when Indian tribes were free and the sole masters of the vast unspoiled beautiful lands. These words seem to have retained in their sound the free wind blowing over the prairie or across the great lakes, the smokes rising over wigwams, the soft speech of dark-skinned people. It seems that Longfellow’s famous lines about Indian legends and tales could well be applied to words of Indian origin:

Should you ask me, whence the stories?

Whence these legends and traditions,

With the odour of the forest,

With the dew and damp of meadows,

With the curling smoke of wigwams,

With the rushing of great rivers …

(From Hiawatha Song)

* * *

One more group of Americanisms is represented by American shortenings. It should be immediately pointed out that there is nothing specifically American about shortening as a way of word-building (see Ch. 6). It is a productive way of word-building typical of both British and American English. Yet, this type of word structure seems to be especially characteristic for American word-building. The following shortenings were produced on American soil, yet most of them are used both in American English and British English: movies, talkies, auto, gym (for gymnasium), dorm (for dormitory), perm (for permanent wave, «kind of hairdo»), то (for moment, e. g. Just а то), circs (for circumstances, e. g. under the circs), cert (for certainty, e. g. That’s a cert), n. g. (for no good), b. f. (for boyfriend), g. m. (for grandmother}, okay. (All these words represent informal stylistic strata of the vocabulary.)

* * *

More examples could be given in support of the statement that the vocabulary of American English includes certain groups of words that are specifically American and possesses certain distinctive characteristics. Yet, in all its essential features, it is the same vocabulary as that of British English, and, if in this chapter we made use of the terms «the vocabulary of American English» and «the vocabulary of British English», it was done only for the sake of argument. Actually, they are not two vocabularies but one. To begin with, the basic vocabulary, whose role in communication is of utmost importance, is the same in American and British English, with very few exceptions.

On the other hand, many Americanisms belong to colloquialisms and slang, that is to those shifting, changeable strata of the vocabulary which do not represent its stable or permanent bulk, the latter being the same in American and British speech.

Against the general extensive background of English vocabulary, all the groups of Americanisms look, in comparison, insignificant enough, and are not sufficiently weighty to support the hypothesis that there is an «American language».

Many Americanisms easily penetrate into British speech, and, as a result, some of the distinctive characteristics of American English become erased, so that the differentiations seem to have a tendency of getting levelled rather than otherwise.

The Grammar System of American English

Here we are likely to find even fewer divergencies than in the vocabulary system.

The first distinctive feature is the use of the auxiliary verb will in the first person singular and plural of the Future Indefinite Tense, in contrast to the British normative shall. The American I will go there does not imply modality, as in the similar British utterance (where it will mean «I am willing to go there»), but pure futurity. The British-English Future Indefinite shows the same tendency of substituting will for shall in the first person singular and plural.

The second distinctive feature consists in a tendency to substitute the Past Indefinite Tense for the Present Perfect Tense, especially in oral communication. An American is likely to say I saw this movie where an Englishman will probably say I’ve seen this film, though, with the mutual penetration of both varieties, it is sometimes difficult to predict what Americanisms one is likely to hear on the British Isles. Even more so with the substitution of the Past Indefinite for the Present Perfect which is also rather typical of some English dialects.

Just as American usage has retained the old meanings of some English words (fall, guess, sick), it has also retained the old form of the Past Participle of the verb to get: to get — got — gotten (cf. the British got).

That is practically the whole story as far as divergencies in grammar of American English and British English are concerned.

The grammatical system of both varieties is actually the same, with very few exceptions.

* * *

American English is marked by certain phonetic peculiarities. Yet, these consist in the way some words are pronounced and in the intonation patterns. The system of phonemes is the same as in British English, with the exception of the American retroflexive [r]-sound, and the labialized [h] in such words as what, why, white, wheel, etc.

* * *

All this brings us to the inevitable conclusion that the language spoken in the United States of America is, in all essential features, identical with that spoken in Great Britain. The grammar systems are fully identical. The American vocabulary is marked by certain peculiarities which are not sufficiently numerous or pronounced to justify the claims that there exists an independent American language. The language spoken in the United States can be regarded as a regional variety of English.

Canadian, Australian and Indian (that is, the English spoken in India) can also be considered regional varieties of English with their own peculiarities.

Exercises

I. Consider your answers to the following.

1. In what different ways might the language spoken in the USA be viewed linguistically?

2. What are the peculiarities of the vocabulary of English spoken in the USA?

3. Can we say that the vocabulary of the language spoken in the USA supports the hypothesis that there is an «American language»? Give a detailed answer.

4. What are the grammatical peculiarities of the American variety of English?

5. Describe some of the phonetic divergencies in both varieties of English.

6. What other regional varieties of English do you know?

II. Read the following extract and give more examples illustrating the same group of Americanisms. What do we call this group?

M: — Well, now, homely is a very good word to illustrate Anglo-American misunderstanding. At any rate, many funny stories depend on it, like the one about the British lecturer visiting the United States; he faces his American audience and very innocently tells them how nice it is to see so many homely faces out in the audience.

Homely in Britain means, of course, something rather pleasant, but in American English ‘not very good looking’. This older sense is preserved in some British dialects.

(From A Common Language by A. H. Marckwardt and R. Quirk1)

III. Read the following extract. What are the three possible ways of creating names for new species of plants and animals and new features of the landscape? Give more examples of the same. What do we call this group of Americanisms?

Q: … I think that this time we ought to give some attention to those parts of the language where the differences in the vocabulary are much more noticeable.

M: Yes, we should. First, there are what we might call the ‘realia’ — the real things — the actual things we refer to in the two varieties of the language. For example, the flora and fauna — that is to say the plants and animals of England and of the United States are by no means the same, nor is the landscape, the topography.

Q: All this must have created a big problem for those early settlers, mustn’t it?

M: It surely did. From the very moment they set foot on American soil, they had to supply names for these new species of plants and animals, the new features of landscape that they encountered. At times they made up new words such as mockingbird, rattlesnake, egg-plant. And then occasionally they used perfectly familiar terms but to refer to different things. In the United States, for example, the robin is a rather large bird, a type of thrush.

Q: Yes, whereas with us it is a tiny little red-breasted bird.

M: And a warbler, isn’t it?

Q: Yes.

M: It sings. Corn is what you call maize. We never use it for grain in general, or for wheat in particular.

Q: Or oats. Well, wouldn’t foreign borrowings also be important in a situation like this?

M: Oh, they were indeed. A good many words, for example, were adopted from the American Indian languages — hickory, a kind of tree, squash, a vegetable; moccasin, a kind of footwear. We got caribou and prairie from the early French settlers. The Spanish gave us canyon and bronco.

(From A Common Language by A. H. Marckwardt and R. Quirk)

IV. Read the following passage. Draw up a list of terms denoting the University teaching staff in Great Britain and in the USA. What are the corresponding Russian terms?

Q: But speaking of universities, we’ve also got a different set of labels for the teaching staff, haven’t we?

M: Yes, in the United States, for example, our full time faculty, which we call staff incidentally — is arranged in a series of steps which goes from instructor through ranks of assistant professor, associate professor to that of professor. But I wish you’d straighten me out on the English s37-stem. Don for example, is a completely mysterious word and I’m never sure of the difference, say, between a lecturer and a reader.

Q: Well, readers say that lecturers should lecture and readers should read! But seriously, I think there’s more similarity here than one would imagine. Let me say, first of all, that this word don is a very informal word and that it is common really only in Oxford and Cambridge. But corresponding to your instructor we’ve got the rank of assistant lecturer, usually a beginner’s post. The assistant lecturer who is successful is promoted, like your instructor and he becomes a lecturer and this lecturer grade is the main teaching grade throughout the university world. Above lecturer a man may be promoted to senior lecturer or reader, and both of these — there’s little difference between them — correspond closely to your associate professor. And then finally he may get a chair, as we say — that is a professorship, or, as you would say, a full professorship. It’s pretty much a difference of labels rather than of organization, it seems to me.

(From A Common Language by A. H. Marckwardt and R. Quirk)

V. Give the British equivalents for the following Americanism.

Apartment, store, baggage, street car, full, truck, elevator, candy, corn.

VI. Explain the differences in the meanings of the following words in American and British English.

Corn, apartment, homely, guess, lunch.

VII. Identify the etymology of the following words.

Ohio, ranch, squash, mosquito, banjo, toboggan, pickaninny, Mississippi, sombrero, prairie, wigwam.

VIII. Comment on the formation of the following’ words.

Rattlesnake, foxberry, auto, Americanism, Colonist, addressee, ad, copperhead, pipe of peace, fire-water.

IX. Translate the following words giving both the British and American variant.

Каникулы, бензин, осень, консервная банка, радио, трамвай.

X. Give the synonyms for the following American shortenings. Describe the words from the stylistic point of view.

Gym, mo, circs, auto, perm, cert, n. g., b. f., g. m., dorm.

XI. In the following sentences find the examples of words which are characteristic of American English. State whether they belong to the group of a) historical Americanisms; b) proper Americanisms; c) American shortenings; d) American borrowings. Take note of their spelling peculiarities.

1. As the elevator carried Brett downward. Hank Kreisel closed and locked the apartment door from inside. 2. A raw fall wind swirled leaves and dust in small tornadoes and sent pedestrians scurrying for indoor warmth. 3. Over amid the bungalows a repair crew was coping with a leaky water main. 4. We have also built, ourselves, experimental trucks and cars which are electric powered. 5. In a plant bad news travelled like burning gasoline. 6. May Lou wasn’t in; she had probably gone to a movie. 7. The bank was about equal in size to a neighbourhood drugstore, brightly lighted and pleasantly designed. 8. Nolan Wainwright walked towards the apartment building, a three-storey structure probably forty years old and showing signs of disrepair. He guessed it contained two dozen or so apartments. Inside a vestibule Nolan Wainwright could see an array of mail boxes and call buttons. 9. He’s a barber and one of our bird dogs.1 We had twenty or so regular bird dogs, Smokey revealed, including service station operators, a druggist, a beauty-parlor operator, and an undertaker. 10. Barbara put a hand to her hair — chestnut brown and luxuriant, like her Polish Mother’s; it also grew annoyingly fast so she had to spend more time than she liked in beauty salons. 11. He hadn’t had an engineering degree to start, having been a high school dropout before World War II. 12. Auto companies regularly invited design school students in, treating them like VIP’s,1 while the students saw for themselves the kind of aura they might work in later.

XII. Read the following joke and find examples of words which are characteristic of American English.

The Bishop of London, speaking at a meeting recently, said that when he was in America he had learned to say to his chauffeur, «Step on the gas, George,» but so far he had not summoned sufficient courage to say to the Archbishop of Canterbury, «О. К., Chief.»

XIII. Bead the following extract. Explain the difference in the meanings of the italicized words in American and British English.

In America just as in English, you see the same shops with the same boards and windows in every town and village.

Shopping, however, is an art of its own and you have to learn slowly where to buy various things. If you are hungry, you go to the chemist’s. A chemist’s shop is called a drugstore in the United States. In the larger drugstores you may be able to get drugs, too, but their main business consists in selling stationery, candy, toys, braces, belts, fountain pens, furniture and imitation jewellery. You must be extremely careful concerning the names of certain articles. If you ask for suspenders in a man’s shop, you receive a pair of braces, if you ask for a pair of pants, you receive a pair of trousers and should you ask for a pair of braces, you receive a queer look.

I should like to mention that although a lift is called an elevator in the United States, when hitch-hiking you do not ask for an elevator, you ask for a lift. There’s some confusion about the word flat. A flat in America is called an apartment; what they call a flat is a puncture in your tyre (or as they spell it, tire). Consequently the notice: Flats Fixed’ does not indicate an estate agent where they are going to fix you up with a flat, but a garage where they are equipped to mend a puncture.

(From How to Scrape Skies by G. Mikes)

XIV. Read the following passage. Do you share Professor Quirk’s opinion about neutralizing the differences between the two forms of English? If so, give your own examples to prove it.

M: … and finally I notice that although we used to think that baggage was somehow an American term and luggage an English term, we have now come to adopt luggage much more, especially in connection with air travel.

Q: Well, I think it is equally true that we in Britain have more and more to adopt the word baggage. I have certainly noticed that on shipping lines, perhaps chiefly those that are connected with the American trade. But this blending of our usage in connection with the luggage and baggage would seem to me to be rather typical of this trend that we’ve got in the twentieth century towards neutralizing the differences between our two forms of English.

(From A Common Language by A. H. Marckwardt and R. Quirk)

XV. Look through the following list of words and state what spelling norms are accepted in the USA and Great Britain so far as the given words are concerned.

1. favour — favor

honour — honor

colour — color

2. defence — defense

practice — practise

offence — offense

3. centre — center

metre — meter

fibre — fiber

4. marvellous — marvelous

woollen — woolen

jewellery — jewelry

5. to enfold — to infold

to encrust — to incrust

to empanel — to impanel

6. cheque — check

catalogue-catalog

programme — program

7. Judgement — judgment

abridgement — abridgment

acknowledgement — acknowledgment

XVI. Write the following words according to the British norms of spelling.

Judgment, practise, instill, color, flavor, check, program, woolen, humor, theater.

XVII. Write the following words according to the American norms of spelling.

Honour, labour, centre, metre, defence, offence, catalogue, abridgement, gramm, enfold, marvellous.

XVIII. Read the following passage. Give some more examples illustrating the differences in grammar between the two varieties of English.

Q: I thought Americans always said gotten when they used the verb get as a full verb. But you did say I’ve got your point, didn’t you?

M: Yes, I did. You know, it’s a common English belief — almost a superstition — about American usage, but it does turn out on examination, as many other things do, that we are closer together than appears on the surface. Actually, we, Americans, use gotten only when our meaning is «to acquire» or «to obtain». We’ve gotten a new car since you were here last. Now, when we use get to mean «possess» or «to be obliged to» we have exactly the same forms as you do. I’ve got a pen in my pocket. I’ve got to write a letter.

(From A Common Language by A. H. Marckwardt and R. Quirk)

XIX. Bead the following extract. What is a citizen of the USA called? Analyse the suggested variants of names from the point of view of word-building.

It is embarrassing that the citizens of the United States do not have a satisfactory name. In the Declaration of Independence the British colonists called their country the United States of America, thus creating a difficulty. What should the inhabitant of a country with such a long name be called?

For more than 150 years those living in the country have searched in vain for a suitable name for themselves. In 1803, a prominent American physician, Dr. Samuel Mitchill, suggested that the entire country should be called Fredonia or Fredon. He had taken the English word freedom and the Latin colonies, and from them coined Fredonia or Fredon. Dr. Mitchill thought that with this word as the name for the country as a whole, the derivative Fredish would follow naturally, corresponding to British, etc. In the same way, he thought, Frede, would be a good name for the inhabitant of Fredonia. But his fellow-citizens laughed at the doctor’s names.

Such citizen names as United Statesian, shortened to Unisian and United Statian were proposed but quickly forgotten. No better success has greeted Usona (United States of North America) as a name for the country and Usonian — for a citizen.

Usage overwhelmingly favours American, as a name for an inhabitant of the USA, though all Americans realize it covers far too much territory.

(From American Words by M. Mathews)

Mod

EV3RY BUDDY’S FAVORITE [[Number 1 Rated Moderator 2023]]

If you think this post is funny, UPVOTE this comment!

If you think this post is unfunny, DOWNVOTE this comment!

DownloadVideo Link

SaveVideo Link

VideoTrim Link

Kevin would also like to remind you that, if you’re really desperate, youtube-dl can be used to download videos from Reddit.

Whilst you’re here, Jealous-Category304, why not join our public discord server?