- «Upon the signature of the International Statute of Secrecy in 1689, wizards went into hiding for good. It was natural, perhaps, that they formed their own small communities within a community.«

- — The secrecy surrounding the wizarding world[src]

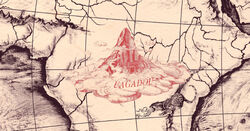

Map of the wizarding schools and their locations around the globe

The wizarding world, also referred to as the magical community, was the society in which wizards and witches lived and interacted, separate from non-wizarding society. The two communities were kept separate through the use of charms, spells, and secrecy. Wizards were forbidden to reveal anything about magic to Muggle society due to the International Statute of Wizarding Secrecy.

Each country had a form of wizarding government to oversee magical affairs in their territory, such as a Ministry of Magic or a Council of Magic. The International Confederation of Wizards served as a wizarding intergovernmental organisation.

Magic was honed through study, training and formal schooling, but couldn’t be simply learnt by Muggles. Non-magic skills, such as picking a lock with a hairpin rather than an Unlocking Charm, were uncommon to the point of novel rarity.[1] Magic was used for mostly everything, including cooking, cleaning, travelling, communicating, child rearing and medical treatment.

Although on the surface, magic appeared morally neutral, the benevolence or malevolence of a spell’s nature was tied to the intention behind it. For instance, the Cruciatus Curse couldn’t effectively torture a victim with pain unless the caster desired to do true harm to the victim. The technology of the wizarding world appeared medieval in character (such as Hogwarts not having any lifts, but instead having only stairs), as the use of magic precluded the need for advanced technology (as well as the fact that magic interfered with electrical equipment).

Government

- Rubeus Hagrid: «Ministry o’ Magic messin’ things up as usual.«

- Harry Potter: «There’s a Ministry of Magic?«

- — Harry Potter is made aware of the British Ministry of Magic[src]

Ministries of Magic

Symbol of the Ministry of Magic

A Ministry of Magic was the primary governing body of the magical community in many countries. These ministries were led by a Minister for Magic, or the local equivalent. In Britain, there was no political separation between executive, legislative and judicial branches of power. The Minister was elected, but it was unknown who has the power to elect him, although there does seem to be some degree of input from the general wizarding population. The duration of term seems not to be fixed; the longest known term was that of British Minister Faris Spavin who was in office from 1865 to 1903, a total of thirty-eight years.[2]

Also in Britain, the Wizengamot and the Council of Magical Law judged those guilty of breaking wizarding law and determined the fate of criminals. Trials consisted of a short hearing with no lawyer or arbitrator and without any possibility to appeal.[3][4] Wizarding criminals might have been sent to horrible places such as Azkaban for punishment.[5] In cases where individuals had been wrongfully imprisoned via with precaution (case in point: Rubeus Hagrid), without trial under false witness (case in point: Sirius Black), without self-defence under a false memory spell (cases in point: Morfin Gaunt and Hokey) or while under the Imperius Curse (case in point: Sturgis Podmore), the Wizengamot barely issued an apology but merely continued with its work.

The Ministry of Magic controlled a great deal of wizarding life, including methods of communication, transportation, internal affairs between wizards and other magical beings, internal security of the wizarding world, Non-Tradeable Material and even sports.

Magical Congress of the United States of America

The Magical Congress of the United States of America (shortened MACUSA) was the magical body in charge of governing the wizarding population of the United States of America. It was led by the President of the Magical Congress of the United States of America. Unlike the No-Maj United States Congress, which was divided into a House of Representatives and a Senate, the MACUSA was unicameral.[6] The MACUSA was located in the Woolworth Building in downtown New York City.

The Magical Congress of the United States of America was established in 1693, as a direct result of the Salem Witch Trials, thus pre-dating the No-Maj government by around a century. The MACUSA performs many of the same functions as other wizarding governing bodies in other countries such as the Ministries of Magic or Councils of Magic.[6]

Ministère des Affaires Magiques de la France

The Ministère des Affaires Magiques de la France was the Government of the magical population of France. It was founded in 1790. A Wallace fountain served as the visitor’s entrance. It was located in the grounds of Place de Furstemberg (in Furstemberg Square) found in the 6th District of Paris. The French Ministry of Magic had a spell that stopped witches and wizards being able to disapparate on their premises.[7]

The French Ministry of Magic had several bureaux in all, each dealing with different aspects of the wizarding world. They were equivalent to the departments of the British Ministry of Magic and MACUSA. Some of these bureauxes include: Bureau de la Justice Magique, Bureau des Magicommunications, and Bureau des Aurors

German Ministry of Magic

The German Ministry of Magic governed the wizarding community of Germany, that was headquartered in Berlin. In 1932, the German Minister of Magic was Anton Vogel, who was also the Supreme Mugwump at that time. The German Ministry hosted a Candidates’ Dinner for the 1932 International Confederation of Wizards’ Supreme Mugwump election. The German Ministry also maintained an underground prison called the Erkstag.[8]

Chinese Ministry of Magic

The Chinese Ministry of Magic governed the wizarding community of China. In 1932, the then Chinese Minister of Magic Liu Tao participated in the Supreme Mugwump election as a candidate. The Chinese Ministry of Magic viewed the walk of the Qilin remotely via some form of magical projection of the event.[8]

International Statute of Wizarding Secrecy

Enormous effort was expended to keep wizarding society from Muggle knowledge. Enchantment of Muggle property was forbidden, underage wizards were restricted from using magic without a licence, and any deliberate revelation of magic was punishable. These laws were created by the International Statute of Wizarding Secrecy and enforced by the International Confederation of Wizards and the Ministry of Magic.[9]

The Ministry did not answer to any part of the Muggle government, but its head was obliged to inform the Prime Minister of events that could cause Muggle notice, such as escaped criminals or the importation of highly dangerous magical creatures.[10] Other exceptions to this secrecy included the Muggle relatives of wizards.

Geography

Great Britain

Geographical layout of Great Britain

The authority of the British Ministry of Magic (and its educational system, Hogwarts) extended to Scotland, England, Wales and also Ireland; however, they each appeared to have separate Quidditch associations, much like the separate athletic associations within the United Kingdom in the Muggle world.

After the introduction of the International Statute of Wizarding Secrecy, most of the wizarding population settled into small villages and hamlets with Muggle populations, where they could be able rely on each other for mutual support. Some of these mixed-population wizard villages included Godric’s Hollow, Ottery St Catchpole, Mould-on-the-Wold, Tinworth and Upper Flagley. The only all-wizard village in Great Britain was Hogsmeade.

In Britain, central wizarding institutions like the Ministry of Magic,[11] St Mungo’s Hospital,[12] and the commercial district surrounding Diagon Alley[13] were in London. However, most magical folk appeared to use magical means to travel there for work, treatment, or shopping, while actually residing in other parts of Britain. Particularly high concentrations of wizards and witches seemed to live in the West Country and the Highlands of Scotland. This might be so because both areas were considered remote and relatively sparsely populated by Muggle standards, allowing for easier adherence to the Statute of Secrecy.

Other countries

The world map of the wizarding world differed from that of the Muggle world. Like wizarding Great Britain, whose borders included all of the British Isles including Ireland, not all wizarding countries corresponded directly to the borders of contemporary Muggle nations. Flanders and Transylvania, for example, existed as independent countries in the wizarding world, but not in the Muggle world. Additionally, some wizarding countries with Muggle equivalents, like Luxembourg and Liechtenstein, had outsized influence in wizarding sports and politics, suggesting their physical size in the wizarding world might be larger than their Muggle equivalent, or else that they had a disproportionately high number of wizards and witches per capita.

Wizarding nations did all appear to have their own Ministries of Magic, and there was an international governing body that coordinated between them all, the International Confederation of Wizards, with such governing bodies as the International Magical Office of Law, which oversaw international wizarding law, and the International Confederation of Wizards’ Quidditch Committee, which governed Quidditch.

Economy

Great Britain

Wizarding currency

The main economic entity in Britain was Gringotts Wizarding Bank, which was run by goblins and features an intense magical security system which includes a subterranean maze, magical barriers and protective spells, and dragons. There were hundreds of thousands of vaults, each with a unique key.[13]

Wizarding currency in the UK had three types of coins and no decimal system. The coins were Galleons, Sickles and Knuts.[13] The exchange rate was as follows:

| One Knut was | One Sickle was | One Galleon was |

| 1 Knut | 29 Knuts | 493 Knuts |

| 0.03448… Sickles | 1 Sickle | 17 Sickles |

| 0.002028… Galleons | 0.05882… Galleons | 1 Galleon |

Around 164 knuts was equivalent to one Muggle British pound in 2001.[14]

There were currently three known currency systems: UK’s Galleons, Sickles and Knuts; the US’s Dragots and Sprinks; and France’s Bezants.

The goblins of Gringotts Wizarding Bank had devised a way to exchange wizarding currency for Muggle currency and vice versa, to allow wizards to use either, as needed. It was unclear how, exactly, this process works, but it was likely to be a common one because Muggle-borns pay for Hogwarts school supplies in wizarding currency every year.[15]

The biggest employer in the wizarding world appeared to be the Ministry of Magic. It was not clear how this worked from an economics standpoint, since there did not appear to be a system of taxation — and even if there was, there did not appear to be sufficient economic activity in the wizarding world to pay for the thousands of ministry employees through taxes.

Just like in the Muggle world, wizards and witches could be rich or poor, employed or unemployed. Wealth appeared to usually be the result of inheritance rather than business acumen or magical ability, suggesting a strong class system.

United States of America

The Dragot was the wizarding currency used in the United States of America. The dragot was manufactured as octagonal and round coins in 1, ½ and ¼ denominations. A possible subunit of the Dragot was the Sprink.

France

The Bezant was the wizarding currency used in France.

Sciences

Technology

Wizards had no need of mundane domestic objects such as dishwashers or vacuum cleaners. Some members of the magical community were amused by Muggle television, and a few firebrand wizards even went so far, in the early eighties, as to start a British Wizarding Broadcasting Corporation, in the hope that they would be able to had their own television channel. The project foundered at an early stage, as the Ministry of Magic refused to countenance the broadcasting of wizarding material on a Muggle device, which would (it was felt) almost guarantee serious breaches of the International Statute of Secrecy.[16]

Some felt, and with justification, that this decision was inconsistent and unfair, as many radios had been legally modified by the wizarding community for their own use, which broadcast regular wizarding programmes. The Ministry conceded that Muggles frequently caught snippets of advice on, for instance, how to prune a Venomous Tentacula, or how best to remove gnomes from a cabbage bed, but argued that the radio-listening Muggle population seemed altogether more tolerant, gullible, or less convinced of their own good sense, than Muggle TV viewers. Reasons for this anomaly were examined at length in Professor Mordicus Egg’s The Philosophy of the Mundane: Why the Muggles Prefer Not to Know. Professor Egg argued cogently that Muggles were much more likely to believe they had misheard something than that they were hallucinating.[16]

There was another reason for most wizards’ avoidance of Muggle devices, and that was cultural. The magical community prided itself on the fact that it did not need the many (admittedly ingenious) devices that Muggles had created to enable them to do what could be so easily done by magic. To fill one’s house with tumble dryers and telephones would be seen as an admission of magical inadequacy.[16]

A Flying Ford Anglia and the Hogwarts Express

There was one major exception to the general magical aversion to Muggle technology, and that was the car (and, to a lesser extent, motorbikes and trains). Prior to the introduction of the International Statute of Secrecy, wizards and Muggles used the same kind of everyday transport: horse-drawn carts and sailing ships among them. The magical community was forced to abandon horse-drawn vehicles when they became glaringly outmoded.[16]

It is pointless to deny that wizardkind looked with great envy upon the speedy and comfortable automobiles that began filling the roads in the twentieth century, and eventually even the Ministry of Magic bought a fleet of cars, modifying them with various useful charms and enjoying them very much indeed. Many wizards loved cars with a child-like passion, and there had been cases of pure-bloods who claimed never to touch a Muggle artefact, and yet were discovered to have a flying Rolls Royce in their garage. Water pipes, faucets, and toilets were also standard in the wizarding world.[16]

Medicine

While Muggle medicine first attempts to stimulate the body’s own healing and defence systems, magic could simply impose well-being or create healing from a source other than the body’s own system. Potions, spells and magical bandages were administered by trained Healers. Pepperup Potion relieved the symptoms of colds and flu and Cheering Charms provided a rudimentary mood stimulation. Where home remedies and ordinary wizard skills failed, St Mungo’s Hospital for Magical Maladies and Injuries employed Healers who attended to everything from fixing conventional ailments to long-term care for victims of severe neurological damage.

Arts and aesthetics

Wizarding architecture in Great Britain was mostly gothic and medieval-styled. Formal vestuary included usually long, dark robes combined with 19th century-resembling clothes. Informal vestuary was a bit more similar to modern shirts and trousers, and modern formal wear and business attire. Magically moving paints were also popular in the wizarding world.

Clothing

- «When mingling with Muggles, wizards and witches will adopt an entirely Muggle standard of dress, which will conform as closely as possible to the fashion of the day. Clothing must be appropriate to the climate, the geographical region and the occasion. Nothing self-altering or adjusting is to be worn in front of Muggles.«

- — International Statute of Secrecy[src]

Dress robes

Wizards at large in the Muggle community might reveal themselves to each other by wearing the colours of purple and green, often in combination. However, this was no more than an unwritten code, and there was no obligation to conform to it. Plenty of members of the magical community preferred to wear their favourite colours when out and about in the Muggle world, or adopt black as a practical colour, especially when travelling by night.[21]

In spite of these clear instructions, clothing misdemeanours had been one of the most common infractions of the International Statute of Secrecy since its inception. Younger generations had always tended to be better informed about Muggle culture in general; as children, they mingled freely with their Muggle counterparts; later, when they entered magical careers, it became more difficult to keep in touch with normal Muggle dress.[21]

Older witches and wizards were often hopelessly out of touch with how quickly fashions in the Muggle world changed; having purchased a pair of psychedelic loon pants in their youth, they were indignant to be hauled up in front of the Wizengamot fifty years later for arousing widespread offence at a Muggle funeral. The Ministry of Magic was not always so strict though.[21]

By and large, wizard clothing had remained outside of fashion, although small alterations had been made to such garments as dress robes. Standard wizard clothing comprised plain robes, worn with or without the traditional pointed hat, and would always be worn on such formal occasions as christenings, weddings and funerals. Women’s dresses tended to be long. Wizard clothing might be said to be frozen in time, harking back to the seventeenth century, when they went into hiding. Their nostalgic adherence to this old-fashioned form of dress might be seen as a clinging to old ways and old times; a matter of cultural pride.[21]

Day to day, however, even those who detested Muggles wore a version of Muggle clothing, which was undeniably practical compared with robes. Anti-Muggles would often attempt to demonstrate their superiority by adopting a deliberately flamboyant, out-of-date or dandyish style in public.[21]

Society

The society of the wizarding world was centred around two facts: that the members could use magic due to inborn capabilities to do otherwise impossible things, and that it was impossible for Muggle society to coexist peaceably alongside wizarding society and therefore it was kept secret.

Internal relations

- «You’ll soon find out some wizarding families are much better than others, Potter. You don’t want to go making friends with the wrong sort.«

- — Draco Malfoy to Harry Potter in their first year at Hogwarts[src]

The most obvious example of wizard prejudice was what ranged from a longstanding disdain to genocidal hatred for Muggles, Muggle-borns, Squibs, and half-blood wizards. Older wizarding families and wizarding society elite lorded blood purity over others, such as the pure-blood Malfoy family[22][23] or House of Black.[24] The practice of pure-blood intermarriage left many with mental illness caused by inbreeding.[25]

Wizards appeared magically capable until advanced old age, and there seemed less prejudice toward the old. Young wizards and witches, on the other hand, were often not respected till of legal age.

The Malfoy family were an example of pure-blood elitism

Werewolves, perfectly normal human beings the majority of their lives and terrifying monsters for a small fraction of it, were so hated and despised that to reveal their affliction was to end all possibility of future employment.[26] Some werewolves, such as Fenrir Greyback, infamously used their lycanthropy to take revenge on society, however most suffered in secrecy due to fear of becoming cast out from society.[27]

Giants, normally solitary creatures given to territorial aggression, were rendered nearly extinct by the refusal of wizards to allow them near habitable land. This forced their kind to cluster together in desolate rocky lands, leading to in-fighting and further deaths. Giants were so feared by wizards that gentle and intelligent half-giants such as Rubeus Hagrid were made to feel ashamed of their heritage and suffered the same prejudice that Muggle-borns and half-bloods did.

House-elves willingly and joyfully did whatever tasks their wizard masters asked of them, had thus been ruthlessly exploited for centuries as a slave-class. The fact that they seemed to like being enslaved had made wizards send their house-elves on life-threatening errands at all corners of the globe. The casting-out of a house-elf from a family was the deepest and most traumatic punishment imaginable for them. This most often led the house-elf to harm itself in grief to the point of death.

Goblins, while they appeared to have at least a grudging co-existence with the wizard world, had nonetheless experienced much discrimination from wizards, and many had led significant uprisings against them in the past.

Muggle relations

- «People say Muggle Studies is a soft option, but I personally think wizards should have a thorough understanding of the non-magical community, particularly if they’re thinking of working in close contact with them — look at my father, he has to deal with Muggle business all the time.«

- — Percy Weasley regarding the importance of Muggle studies[src]

A Muggle Studies class

Most things of magical nature were hidden from Muggles. However, to wizards, the Muggle world was also very mysterious. Wizards tended to bungle attempts to disguise themselves as Muggles when they ventured into Muggle society (for example, wearing clothing meant for the opposite sex). Muggle technology, such as the telephone or revolver, were foreign and obscure to wizards.

Muggle Studies was offered at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry,[28] but the subject was considered soft by some,[28] or was downright disdained by prejudiced wizards.[29] The only known Muggle without wizards in his/her family that knew of the wizarding world was the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

Class, equality, and prejudices

- Remus Lupin: «Muggle-borns are being rounded up as we speak.«

- Ron Weasley: «But how are they supposed to have ‘stolen’ magic? It’s mental, if you could steal magic there wouldn’t be any Squibs, would there?«

- Remus Lupin: «I know. Nevertheless, unless you can prove that you have at least one close wizarding relative, you are now deemed to have obtained your magical power illegally and must suffer the punishment.«

- — Remus Lupin explaining the Ministry of Magic’s attitude while under Death Eater control[src]

Mudbloods and the Dangers They Pose to a Peaceful Pure-Blood Society, an example of the prejudice that exists in the wizarding world

Perhaps the only true prejudice in the wizarding community, which was very pervasive until 1998, seemed to exist towards those naturally unable to perform magic, as well as their relatives and descendants. Magic couldn’t be performed by anyone, but only by those with inborn capacity carried by genetics. Thus, the Muggles (non-magical people) were subjugated because they lacked magical abilities, and Muggle-born wizards were also subjugated because their blood was considered foul. Half-bloods, wizards with both magic and non-magic relatives, received a varied treatment.

Blood status was, consequently, an important class indicator in the wizarding world for much of its history, especially before the fall of Lord Voldemort at the end of the Second Wizarding War in May 1998. Many pure-blood wizards and witches showed strong prejudice and despise towards Muggle-borns and people who supported them.[22][30] This went back to at least a thousand years before the war, since Salazar Slytherin, one of the founders of the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, was against the admission of Muggle-borns to the school.[31][30] Tensions between wizards and Muggles led to the introduction of the Statute of Secrecy in 1692.[30] Slytherin’s descendant Tom Riddle, as he became Lord Voldemort, started two war campaigns against Muggle-borns and their supporters in the late 20th century. The pure-blood Malfoy family were an example of family who supported Voldemort.

Besides blood status, other distinguishable societal factors called much less attention. Money, despite existing in the wizarding society, seemed to lack the same pivotal importance to wizards as it has to Muggles, since wizards would be rarely subject to absence of food and other fundamental needs. There were cases, however, of rich wizards looking down to wizards with less money, such as Lucius Malfoy to the Weasleys, despite both families being pure-blood.[32][22]

Gender prejudice did not seem to play a role in the wizarding society, as both males and females held equally important posts, including those of professor, headmaster/headmistress, writer and even the post of Minister for Magic, the most important to the British wizarding community, with numerous male and female notable names in each of these professions. There appeared to also be much less discrimination and prejudice in British and global wizarding society based on sexual orientation. There was no reference to racial prejudice or even that wizards recognised different races.[33]

Remus Lupin also stated that there were no Muggle princes in the wizarding world.[27]

Religion

Wizards practised all manner of faiths and religions. Christmas and Easter were celebrated communally, though the celebrations mainly covered the non-religious portions of the holidays. Witches and wizards could be members of any faith, and there was no mention of specifically wizarding religions.

Illness and disability

Dragon Pox, a common wizarding illness

Wizards had the power to correct or override «mundane» nature, but not «magical» nature. Therefore, a wizard could catch anything a Muggle might catch, but they could cure all of it; they could also comfortably survive a scorpion sting that might kill a Muggle, whereas they might die if bitten by a Venomous Tentacula. Similarly, bones broken in non-magical accidents such as falls or fist fights could be mended by magic, but the consequences of curses or backfiring magic could be serious, permanent or life-threatening.[34]

Gilderoy Lockhart, victim of his own mangled Memory Charm, had permanent amnesia. The Longbottoms remained permanently damaged by magical torture, and why Mad-Eye Moody had to resort to a wooden leg and a magical eye when the originals were irreparably damaged in a wizards’ battle. Luna Lovegood’s mother, Pandora, died when one of her own experimental spells went wrong, and Bill Weasley was irreversibly scarred after his meeting with Fenrir Greyback.[34]

Thus it could be seen that while wizards had an enviable head start over Muggles in dealing with the flu, and all manner of serious injuries, they had to deal with problems that Muggles never face. Not only was the Muggle world free of such perils as Devil’s Snare and Blast-Ended Skrewts, the Statute of Secrecy has also kept Muggles free from contact with any wizard who could pass on Dragon Pox (as the name implies, originally contracted by wizards working closely with Peruvian Vipertooths) or Spattergroit.[34]

Lycanthropy, which caused a person to become a werewolf, was a highly stigmatised illness. Those who had been affected had often been shunned and hated.[26]

Education

Wizards were educated in their own wizarding schools.[35]

Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry

- «The finest school of witchcraft and wizardry in the world.«

- — Rubeus Hagrid praising Hogwarts[src]

Hogwarts crest

An untrained wizard child may have performed random bursts of magic intuitively when distressed or excited. Honing and controlling this into a usable skill took years of education. There was no official wizarding primary school system; however, parents might have home-schooled their children[36] or sent them to Muggle schools until they were of age to move on to formal wizarding education, at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, for example, the age of entry was eleven years on or before 1 September.

For Hogwarts, the ability to use magic was automatic grounds for admittance. There was a magical quill that wrote down into the Book of Admittance the names and births of those at the precise moment of first exhibiting signs of magic. A letter was sent to the child’s home at the age of eleven to explain that they had been accepted into Hogwarts. The homes of Muggle-born wizards received an envoy to explain the situation.[37]

Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, located in Scotland, provided education to wizarding students with residence in Britain and Ireland.[38] Students could enrol at age eleven and undertook seven years of training in a wide variety of subjects.[39] When education was complete, graduates were considered mature and capable members of the wizarding society. Some subsequent professions, such as Auror, required additional education and training.

The Wizarding Examinations Authority examined students in their fifth and seventh years at Hogwarts who sat O.W.L. and N.E.W.T. exams. The head, Griselda Marchbanks, was a very elderly witch who examined a school-aged Albus Dumbledore in his seventh year.[40] Since Dumbledore was 115 in 1997 and Griselda must had been educated fully, she was likely at least a full year older than Dumbledore (although this was an estimated minimum, it’s likely she was even older).

Ilvermorny School of Witchcraft and Wizardry

- «The great North American school of magic was founded in the seventeenth century. It stands at the highest peak of Mount Greylock, where it is concealed from non-magic gaze by a variety of powerful enchantments, which sometimes manifest in a wreath of misty cloud.«

- — Description of the school[src]

Ilvermorny crest

Ilvermorny was the American wizarding school, located on Mount Greylock in modern day Massachusetts. It accepted students from all over North America. Students of this school, as at Hogwarts in Scotland, were sorted into four houses.[41][42] Ilvermorny Castle was located on top of the highest peak of Mount Greylock in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts.

Ilvermorny was founded during the early seventeenth century after 1620, 630 years after Hogwarts, and the school was originally just a rough shack containing two teachers and two students. Ilvermorny was originally a stone cottage constructed by Irish immigrant Isolt Sayre, and her No-Maj husband James Steward. It became a school when their adoptive children Chadwick and Webster Boot hoped they could return to Ireland so they could attend Hogwarts. Isolt then promised they could build their own school at Ilvermorny with the objective of home-schooling them.[43]

Thus, the school started with just the couple acting as teachers and their two adopted sons, Chadwick and Webster Boot, as students. Each of them named one of the four Houses: Chadwick created Thunderbird, Webster created Wampus, Isolt created Horned Serpent, and James created Pukwudgie. Defence Against the Dark Arts was one of the subject which has been taught at Ilvermorny since the 17th century. One of the teachers was Rionach Steward, the daughter of Ilvermorny founders Isolt Sayre and James Steward. Another known subject at Ilvermorny was Charms. Chadwick’s Charms Vols I – VII, which was written by founder Chadwick Boot were standard textbooks for Charms class at Ilvermorny.[43]

Beauxbatons Academy of Magic

- «Thought to be situated somewhere in the Pyrenees, visitors speak of the breath-taking beauty of a chateau surrounded by formal gardens and lawns created out of the mountainous landscape by magic.«

- — Description of the landscape around Beauxbatons[src]

Beauxbatons crest

Beauxbatons Academy of Magic (French: Académie de Magie Beauxbâtons) was the French wizarding school, located in the Pyrenees[44] in southern France. It took students from France, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain.

The Palace of Beauxbatons was a beautiful chateau surrounded by majestic gardens and fountains magically created out of the surrounding mountains, and had stood for over seven hundred years.[44]

The students at Beauxbatons Academy had been taught to stand at attention from when their Headmistress entered the room until she seated herself, showing great respect for her. Education at Beauxbatons Academy was just as good, if not better, than the education at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry in Scotland. Students took their Ordinary Wizarding Levels in their sixth year.

Durmstrang Institute

- «Durmstrang doesn’t admit that sort of riffraff. But Mother didn’t like the idea of me going to school so far away. Father says Durmstrang takes a far more sensible line than Hogwarts about the Dark Arts. Durmstrang students actually learn them, not just the defence rubbish we do…«

- — Durmstrang’s customs and practices[src]

Durmstrang crest

The Durmstrang Institute (Cyrillic: Дурмстранг) was the Scandinavian wizarding school, located in the northernmost regions of either Norway or Sweden.[45] The school, which presumably took mainly northern European students, was willing to accept international students as far afield as Bulgaria. Durmstrang was one of the three schools that competed in the Triwizard Tournament. It was an old school, having existed since at least 1294,[46], and was notorious for teaching the Dark Arts.[45]

Durmstrang did not admit Muggle-borns.[45] However, it was shown that the students might not necessarily share this idea, as Krum attended the Yule Ball with Hermione Granger,[47] who was Muggle-born and would not had been admitted at his school.

Durmstrang, like Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, was in a castle, though their castle was not quite as big as Hogwarts. The castle was only four stories tall and fires were only lit for magical purposes. It had very extensive grounds and was surrounded by lakes and mountains. In addition, the school was Unplottable. Durmstrang was notorious for its acceptance of the Dark Arts, and was known to had educated (and later expelled) Gellert Grindelwald before his ascension as a Dark wizard.

Castelobruxo

- «The Brazilian school for magic, which takes students from all over South America, may be found hidden deep within the rainforest. «

- — Description[src]

Castelobruxo

Castelobruxo was the Brazilian wizarding school, located amid the Amazon rainforest in northern Brazil. It took students from all over South America. Described as a fabulous castle, the building was an imposing square edifice of golden rock, often compared to a temple. Castelobruxo was implied to be as old as Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, as it was not known which school was first bewitched to appear as a ruin for Muggles.[48]

Castelobruxo students were especially advanced in Herbology and Magizoology. The school was known to offer very popular exchange programmes for students from European wizarding schools.[48]

Bill Weasley once had a pen-friend at this school. However, their friendship ended because Bill was unable to go on an exchange trip there, due to his family’s financial problems. To add insult to injury, the pen-friend sent Bill a cursed hat, which made his ears shrivel up.[49]

Mahoutokoro

- «This ancient Japanese school has the smallest student body of the eleven great wizarding schools and takes students from the age of seven (although they do not board until they are eleven).«

- — Description[src]

Mahoutokoro

Mahoutokoro was the Japanese wizarding school, located on the topmost point of the Volcanic island of Minami Iwo Jima. It had the smallest student body of the eleven wizarding schools.[50]

The school was located at the topmost point of Minami Iwo Jima, a Japanese volcanic island. The palace was described as anotações ornate and exquisite. Both island and palace were thought to be uninhabited by Muggles. Mahoutokoro was possibly one of the oldest wizarding schools, as it was described as «ancient».[50]

Mahoutokoro had the reputation to have an impressive academic prowess. Every member of the Japanese National Quidditch team and the current Champion’s League winners (the Toyohashi Tengu) attributed their prowess to the gruelling training they were given at Mahoutokoro, where they practised over a sometimes turbulent sea in stormy conditions, forced to keep an eye out not only for the Bludgers, but also for planes from the Muggle airbase on a neighbouring island.[50]

The school took students from the age of seven, although they did not board until they were eleven.[50]

Uagadou

- «Although Africa has a number of smaller wizarding schools, there is only one that has stood the test of time (at least a thousand years) and achieved an enviable international reputation: Uagadou.«

- — Uagadou’s extensive history[src]

Uagadou

Uagadou was the Ugandan wizarding school, located atop the Mountains of the Moon in western Uganda. It took students from all over Africa, and was the largest of the eleven wizarding schools.[51][52]

Uagadou was created at least a thousand years prior to the time of Harry Potter. Although a number of smaller schools were to be found in Africa, Uagadou stood the test of time and achieved an enviable international reputation. Uagadou students were skilled in Astronomy, Alchemy, and Self-Transfiguration. Since wands were mostly a European invention, Uagadou students preferred and were able to cast spells by pointing the finger or through hand gestures.[51]

Koldovstoretz

Koldovstoretz school was the Russian wizarding school. Students from Koldovstoretz played a version of Quidditch where they flied on entire, uprooted trees instead of broomsticks.[53]

Wizarding Academy of Dramatic Arts

The Wizarding Academy of Dramatic Arts (W.A.D.A.) was a wizarding school that provided education for witches and wizards who sought a theatrical or performance career. Professor Herbert Beery began teaching at the Academy after leaving the post of Herbology Professor at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.[54]

Transport and communication

As witches and wizards lived in many areas of the known world, wizard modes of transport and communication must cover distances in a variety of ways.

Transportation

- Apparition: teleportation[55] (carries risk of splinching).[56]

- Floo Network: fireplace travel.[32]

- Flying: Broomsticks, Thestrals, flying carpets, flying motorcycles,[57] and flying cars.[1]

- Ground travel: The Hogwarts Express,[58] the Knight Bus,[59] and Ministry cars.

- Phoenix[60][61]

- Portkey: touching an item and coming to a specific set place.[55][62]

- Vanishing Cabinet: transporting from one cabinet to the other.[63]

- Toilet network: used in the Ministry of Magic.[64]

Communication

Sirius Black communicating through the Floo Network

- Objects enchanted with the Protean Charm (such as enchanted coins or dark mark tattoos) to allow each object to react to the others.

- Floo Network: fireplace communication.[32]

- Interdepartmental memo[11]

- Memorandum Rodentium

- Owls: The most common means of communication, which cooperated with wizards to convey packages, messages and letters.[65][59] In some circumstances, the owl would request payment or food in exchange for services.[13] A wizard or witch might own a separate animal that could be used instead. Albus Dumbledore, for example, had a phoenix named Fawkes that acted as an owl, although much more loyal.

- Patronus Charm[66]

- Portraits: Photographs and portraits in the wizarding world were usually enchanted so that they moved, with photographs acting as brief, looping recordings of an event or person, while portraits possessed a form of enchanted intelligence that allowed them to communicate with humans and each other, to move locations of their own accord under certain circumstances, and to pass along messages and advice reflecting the personality and knowledge of the original subject.[12][67]

- Two-way mirror[68]

- Wireless: All-wizarding radio stations existed,[16] though it was not clear if the radios that received the frequency were magical or Muggle in nature, it was unlikely electricity was used due to its known disruption due to magic.

Behind the scenes

- There was some confusion regarding the population of the wizarding world. The year Harry Potter entered Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, there were forty students that started school. This seems to indicate a very low birth rate, or a very low number of witches and wizards in Great Britain and Ireland, or a combination of both. Also, J. K. Rowling has stated that she imagines the wizarding population of the U.K. to be around 3,000. This estimate, although seemingly small, was understandable; a larger population would be far harder to hide from Muggles. However, she also stated that the number of students attending Hogwarts was around 1,000, which seems inconsistent with the 3,000 population estimate. Harry once observed in one Quidditch match that three-quarters of the stadium was supporting Gryffindor, while the Slytherin supporters numbered around 200. There were a large number of government departments, and Harry Potter observes hundreds of witches and wizards in the Ministry of Magic’s Atrium alone. This would appear to be too large for such a small population. The Quidditch World Cup stadium could hold 100,000 and was built by a Ministry task force of five hundred. It seems very unlikely that a sixth of the entire country worked for a full year on one single project, though it was possible that the Ministry could had hired out from other countries. If one were to extrapolate from Rowling’s statement that 1,000 students were at Hogwarts at a given time, however, a more sensible number seems to suggest itself: Given that 1,000 students spread over 7 years would make a class size each year of about 143 students, that nearly every young wizard and witch in Britain appears to attend Hogwarts, and that wizards and witches seem to live around 100 years if they don’t die by unnatural causes, 1,000 Hogwarts students would put the total wizarding population in Britain at 12,000 to 15,000—a number that would support almost all details known about the wizarding world.

- If the wizarding population was 15,000 then the Muggle to wizard ratio was about 4,150 to 1. This means that the current world wizarding population was roughly 1.6 to 1.7 million. If this ratio was true then unless something was drastically different a thousand years ago there were less than 900 wizards and witches in all of Britain when Hogwarts was founded. 9 students per year, tops.

- In the last 1990s, 755-year-old Barry Winkle invited «every wizard and witch he had ever known» to a massive party, with 30 million wizards attending it. Although Tier Two canon, and thus superseded by Rowling’s own estimates, if accepted as canon, it would suggest a much bigger number of wizards worldwide, although it likely included ghosts.

- According to W.O.M.B.A.T., the age at which magic may be performed legally may change from country to country.

- According to J. K. Rowling, the wizarding and Muggle worlds will never rejoin.[69]

- Even though it was shown that the wizarding world was far behind in technology and modern items, in the the film adaptation of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Rita Skeeter was seen using a Muggle pen and notepad.

Appearances

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (First appearance)

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (film)

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (video game)

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (film)

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (video game)

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (film)

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (video game)

- Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

- Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (film)

- Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (video game)

- Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix

- Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (film)

- Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (video game)

- Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

- Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (film)

- Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (video game)

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1 (video game)

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 (video game)

- Harry Potter and the Cursed Child

- Harry Potter and the Cursed Child (play)

- Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them: The Original Screenplay

- Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (film)

- The Case of Beasts: Explore the Film Wizardry of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them

- Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald — The Original Screenplay

- Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald

- The Archive of Magic: The Film Wizardry of Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald

- Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore — The Complete Screenplay

- Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore

- Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore: Movie Magic

- Quidditch Through the Ages

- Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them

- The Tales of Beedle the Bard

- Daily Prophet Newsletters (Mentioned only)

- J. K. Rowling’s official site (Mentioned only)

- Pottermore

- Wizarding World

- The Queen’s Handbag

- Harry Potter Official Site

- The Wizarding World of Harry Potter

- The Making of Harry Potter

- Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Motorbike Escape

- Harry Potter: The Character Vault

- Harry Potter: The Creature Vault

- Harry Potter: Quidditch World Cup

- LEGO Harry Potter

- LEGO Harry Potter: Building the Magical World

- LEGO Harry Potter

- LEGO Creator: Harry Potter

- Creator: Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

- LEGO Harry Potter: Years 1-4

- LEGO Harry Potter: Years 5-7

- LEGO Dimensions

- Harry Potter: Spells

- Harry Potter for Kinect

- Wonderbook: Book of Spells

- Wonderbook: Book of Potions

- Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them VR Experience

- Fantastic Beasts: Cases from the Wizarding World

- Harry Potter: Hogwarts Mystery

- Harry Potter: Wizards Unite

- Harry Potter: Puzzles & Spells

- Harry Potter: Magic Awakened

- Hogwarts Legacy

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Chapter 3 (The Burrow)

- ↑ Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Ministers for Magic» at Wizarding World

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Chapter 30 (The Pensieve)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Chapter 8 (The Hearing)

- ↑ Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Azkaban» at Wizarding World

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Pottermore — RETURN OF HANS THE AUGUREY (Archived)

- ↑ Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald — The Original Screenplay, Scene 89

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore

- ↑ Harry Potter: Hogwarts Mystery, Year 5, Chapter 15 (Secrets and Lies) — History of Magic Lesson «International Statute of Secrecy»

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Chapter 1 (The Other Minister)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Chapter 7 (The Ministry of Magic)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Chapter 22 (St Mungo’s Hospital for Magical Maladies and Injuries)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Chapter 5 (Diagon Alley)

- ↑ Quidditch Through the Ages — rear cover

- ↑ AOL Live Interview with J. K. Rowling — October 19, 2000

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Technology» at Wizarding World

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Pottermore — Magical Drafts and Potions

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Chapter 8 (The Potions Master)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Chapter 36 (The Parting of the Ways)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Chapter 10 (The Rogue Bludger)

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Clothing» at Wizarding World

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Chapter 7 (Mudbloods And Murmurs)

- ↑ Writing by J. K. Rowling: «The Malfoy Family» at Wizarding World

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Chapter 6 (The Noble and Most Ancient House of Black)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Chapter 10 (The House of Gaunt)

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Werewolves» at Wizarding World

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Chapter 16 (A Very Frosty Christmas)

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Chapter 14 (Cornelius Fudge)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Chapter 1 (The Dark Lord Ascending)

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Pure-Blood» at Wizarding World

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Chapter 9 (The Writing on the Wall)

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Chapter 4 (At Flourish and Blotts)

- ↑ The narration referred to certain characters as black, but this was from the perspective of Harry Potter, who was raised in the Muggle world.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Illness and Disability» at Wizarding World

- ↑ Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Wizarding Schools» at Wizarding World

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Chapter 11 (The Bribe)

- ↑ Writing by J. K. Rowling: «The Quill of Acceptance and The Book of Admittance» at Wizarding World

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Chapter 4 (The Keeper of the Keys)

- ↑ Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Hogwarts School Subjects» at Wizarding World

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Chapter 31 (O.W.L.s)

- ↑ News: «Pottermore reveals that Ilvermorny is the North American wizarding school» at Pottermore

- ↑ .@tannerfbowen No, but he’s going to meet people who were educated at [name in [not New York] by J.K. Rowling on Twitter

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Ilvermorny School of Witchcraft and Wizardry» at Wizarding World

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Beauxbatons Academy of Magic» at Wizarding World

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Chapter 11 (Aboard the Hogwarts Express)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Chapter 12 (The Triwizard Tournament) — The Triwizard Tournament was established some 700 years ago = c.1294

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Chapter 23 (The Yule Ball)

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Castelobruxo» at Wizarding World

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Chapter 7 (Bagman and Crouch)

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Mahoutokoro» at Wizarding World

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Uagadou» at Wizarding World

- ↑ @naunihalpublic Uagadou takes students from all over Africa, but it is in Uganda. #IAgreePottermoreShouldSayThatWillChangeDescription by J. K. Rowling on Twitter.com

- ↑ Pottermore facts from the 2014 UK editions of the Harry Potter books (transcript and link to photographs here)

- ↑ The Tales of Beedle the Bard — «The Fountain of Fair Fortune»

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Chapter 6 (The Portkey)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Chapter 18 (Birthday Surprises)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Chapter 1 (The Boy Who Lived)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Chapter 6 (The Journey from Platform Nine and Three-Quarters)

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Chapter 1 (Owl Post)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Chapter 17 (The Heir of Slytherin)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Chapter 27 (The Centaur and the Sneak)

- ↑ Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Portkeys» at Wizarding World

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Chapter 27 (The Lightning-Struck Tower)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Chapter 12 (Magic is Might)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Chapter 3 (The Letters from No One)

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Chapter 8 (The Wedding)

- ↑ Writing by J. K. Rowling: «Hogwarts Portraits» at Wizarding World

- ↑ Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Chapter 38 (The Second War Begins)

- ↑ J.K. Rowling gives revealing answers in World Book Day chat on beyondhogwarts.com

See also

- List of spells

- Wizardkind

- Dark wizard

- Wizarding Wars

Wizarding world of harry potter

Содержание

- 1 Волшебный Мир Гарри Поттера (Wizarding World of Harry Potter)

- 1.1 История

- 1.2 Горки и аттракционы

- 1.3 Магазины

- 1.4 Рестораны

- 1.5 Другие развлечения

- 2 Ссылки

Волшебный Мир Гарри Поттера (Wizarding World of Harry Potter)

«Волшебный мир Гарри Поттера» — это тематический парк развлечений в духе Гарри Поттера. Подобно другим паркам от студии Universal Studios Florida он рассчитан на то, чтобы его гости ощущали атмосферу своего любимого фильма. Парк построен в городе Орландо, штат Флорида, США. Официальное открытие назначено на 18 июня 2010 года. На сегодняшний день свое присутствие в день открытия подтвердили Бонни Райт, Том Фелтон, Оливер Фелпс и Джеймс Фелпс.

История

31 мая 2007 года Universal Orlando объявили о том, что Warner Bros и писательница Джоан К.Роулинг обеспечили их правами на создание парка. Парк площадью 81 000 м² обещал воссоздать мир Гарри Поттера на основе одноименных книг и фильмов. Строительство начали в 2007 году, а официальную дату открытия (18 июня 2010) объявили 25 марта 2010 года. Документальные материалы о подготовке парка были включены в Blu-Ray и DVD диски фильма Гарри Поттер и Принц-полукровка.

Горки и аттракционы

Состязания с драконом

Аттракцион «Состязания с драконом» основан на Турнире Трех Волшебников, который был показан в фильме Гарри Поттер и Кубог Огня. Два дракона, состязающихся между собой, будут называться также как и в фильме- Венгерская Хвосторога и Китайский Огненный Шар.

Полет на Гиппогриффе

«Полет на Гиппогриффе» — облегченный вариант американских горок. Горка переплетается с аттракционом «Состязания с драконом», который намного экстремальнее.

Гарри Поттер и Запретное путешествие

«Гарри Поттер и запретное путешествие» — это горка, которая проезжает по всему парку «Волшебный Мир Гарри Поттера». Поездка сопровождается знаменитыми сценами и площадками в духе Гарри Поттера. Этот аттракцион основан исключительно на современных и новаторских технологиях. Относится к проектам Islands of Adventure.

Хижина Хагрида

Хижина Хагрида — один из проектов Islands of Adventure подающих надежды. Аттракцион полностью включает в себя горку «Полет на Гиппогриффе», которая расположена «летать» в близости от домика лесничего. Гости не смогут войти внутрь хижины, так как это строение задумывалось лишь как памятник, в точности воспроизводящий дом Рубеуса Хагрида.

Интерактивное испытание Олливандера

Этот аттракцион является точной копией лавки Олливандера из фильмов Гарри Поттера во всех смыслах этого слова. Как когда сам Гарри Поттер получил свою первую палочку также и Вы сможете приобрести здесь свою. С помощью интерактивного испытания «Палочка выберает волшебника» Вы узнаете какая волшебная палочка подходит именно Вам. Здесь же будут продаваться все палочки, которые когда либо описывала Джоан Роулинг.

Магазины

Сладкое Королевство

Самый знаменитый волшебный магазин кондитерских изделий «Сладкое Королевство». Здесь продаются все мыслимые и немыслимые сладости из мира волшебников! Взрывающиеся леденцы, заварные котелки, лакричные палочки, жвачки Друбблс, сахарные перья, шоколадные лягушки, разноцветные драже Барти Боббс, сливочные помадки, кровавые ледянцы и т.д. Магазин находится в деревне Хогсмид. Дэрвиш & Бэнгз

«Дэрвиш & Бэнгз» – магазин волшебных вещиц и снаряжения, таких как набор “Все для Квиддича”, форма для Турнира Трех Волшебников, Спектральные очки, напоминалки, легендарная книга “Чудовищная книга о чудовищах”. Здесь же Вы сможете приобрести любой реквизит, использованный в фильмах. Магазин находится в деревне Хогсмид.

ЗОНКО

Магазин «ЗОНКО» — находка для шутников и всех людей с хорошим чувством юмора. Здесь можно найти удлинители ушей, вопящую игрушку Йо-йо, боксирующий телескоп и летающие шутихи от мастеров Уизли. Также Вы сможете оценить «вкусный юмор»: тыквенные пастилки, блевательные батончики и кровопролитные конфетки и т.п. Магазин также находится в деревне Хогсмид.

Лавка Олливандера

Необыкновенный шоппинг за волшебной палочкой ждет вас в лавке Олливандера. Едва ступив на порог вы окажитесь в комнате полной пыльных коробочек с волшебными палочками. Лучшие специалисты мира помогут выбрать волшебную палочку, которая будет слушаться только Вас!

Кладовая Филча с конфискованными вещами

Магазин игрушек предстанет перед гостями словно торговый центр персонажа Аргуса Филча. Расположен в самом замке Хогвартс.

Рестораны

Гостиница/Ресторан Три Метлы и бар Кабанья голова – это место где можно погреться у огня, попивая пинту сливочного пива или фирменный тыквенный сок. Вы можете заказать деликатесы, национальные британские блюда, пасту, Корнуэльские пирожки, запеченную индейку, свежие овощи и фрукты. Для детей особое меню. На десерт – яблочный, клубничный пироги, арахисовое масло, шоколадные трюфели и многое другое.

Другие развлечения

Деревня Хогсмид

«Хосмид» — это место отдыха и развлечений из мира Гарри Поттера. В этой деревне расположен показательный поезд Хогвартс Экспресс, лавка Олливандера, рестораны и другие магазины.

Совиная(почтовая)служба

В вымышленном мире Гарри Поттера, «Совятня» – это место где совы отдыхают до или после того как доставили письмо. В парке же это тематическое место отдыха для посетителей, однако, Вы также сможете отправить письмо, на котором будет специальный герб деревни Хогсмид.

Территория Хогвартса

Замок «Хогвартс» самое масштабное здание в парке, воспроизведенное по книгам и фильмам. В его владениях расположены: «Полет на Гиппогриффе», «Состязания с драконом», «Хижина Хагрида».

Замок Хогвартс

Хогвартс – школа Чародейства и волшебства — является неотъемлемой частью книг и фильмов о Гарри Поттере. В этом замке можно посетить культовые места: кабинет Дамблдора, класс Защиты от Темных Искусств, гостиную Гриффиндора, Выручай-комнату и т.д. «Аттракцион Гарри Поттер и Запретный Путешествие» включает в себя большую часть замка, тем не менее, небольшая площадь в здании будет по-прежнему доступна для прогулок гостей во время отдыха.

Ссылки

Официальный сайт: Wizarding World of Harry Potter

Забронировать путешествие можно на сайте: Universalorlando.com

Видео репортажи о парке: Hp-video.gallery.ru

Фотографии и рекламные снимки парка: Harry-potter.gallery.ru

[Категория:Развлечения]]

| Wizarding World | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Created by | J. K. Rowling |

| Original work | Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (1997) |

| Owner |

|

| Years | 1997–present |

| Print publications | |

| Novel(s) | Harry Potter series |

| Films and television | |

| Film(s) |

|

| Theatrical presentations | |

| Play(s) | Harry Potter and the Cursed Child |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Theme park attraction(s) | The Wizarding World of Harry Potter |

| Digital publication | Wizarding World Digital |

The Wizarding World[1][2] (previously known as J. K. Rowling’s Wizarding World)[3][4] is a fantasy media franchise and shared fictional universe centred on the Harry Potter novel series by J. K. Rowling. A series of films have been in production since 2000, and in that time eleven films have been produced—eight are adaptations of the Harry Potter novels and three are part of the Fantastic Beasts series. The films are owned and distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures. The series has collectively grossed over $9.6 billion at the global box office, making it the fourth-highest-grossing film franchise of all time (behind the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Star Wars and Spider-Man).

David Heyman and his company Heyday Films have produced every film in the Wizarding World series. Chris Columbus and Mark Radcliffe served as producers on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, David Barron began producing the films with Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix in 2007 and ending with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 in 2011, and Rowling produced the final two films in the Harry Potter series. Heyman, Rowling, Steve Kloves and Lionel Wigram have produced both films in the Fantastic Beasts series. The films are written and directed by several individuals and feature large, often ensemble, casts. Many of the actors, including Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint, Emma Watson, Tom Felton, Michael Gambon, Ralph Fiennes, Alan Rickman, Maggie Smith, Helena Bonham Carter, Gary Oldman, Eddie Redmayne, Katherine Waterston, Alison Sudol, and Dan Fogler star in numerous films. Additionally, Jude Law and Johnny Depp feature in two films each. Soundtrack albums have been released for each of the films. The franchise also includes a stage production (Harry Potter and the Cursed Child), a digital publication, a video game label and The Wizarding World of Harry Potter–themed areas at several Universal Parks & Resorts amusement parks around the world.

The first film in the Wizarding World was Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001), which was followed by seven Harry Potter sequels, beginning with Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets in 2002 and ending with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 in 2011, nearly ten years after the first film’s release. Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016) is the first film in the spin-off/prequel Fantastic Beasts series. A sequel, titled Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald, was released on 16 November 2018. A third film, Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore was released on 15 April 2022. The first Wizarding World-branded narrative video game, Hogwarts Legacy, was released in early 2023. Warner Bros. is also planning to develop a television series, set in the Wizarding World, to debut on HBO Max.[5]

Harry Potter films[edit]

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001)[edit]

David Heyman has produced every film in the Wizarding World.

Harry Potter, a seemingly ordinary eleven-year-old boy, is actually a wizard and survivor of Lord Voldemort’s attempted rise to power. Harry is rescued by Rubeus Hagrid from his unkind Muggle relatives, Uncle Vernon, Aunt Petunia, and his cousin Dudley, and takes his place at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, where he and his friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger become entangled in the mystery of the Philosopher’s Stone, which is being kept within the school.

In October 1998, Warner Bros. purchased the film rights to the first four novels of the Harry Potter fantasy series by J. K. Rowling for a seven-figure sum,[18] after a pitch from producer David Heyman.[19] Warner Bros. took particular notice of Rowling’s wishes and thoughts about the films when drafting her contract. One of her principal stipulations was that they are shot in Britain with an all-British cast,[20] which has been generally adhered to. On 8 August 2000, the then-unknown Daniel Radcliffe and newcomers Rupert Grint and Emma Watson were selected to play Harry Potter, Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger, respectively.[21] Chris Columbus was hired to direct the film adaptation of Philosopher’s Stone,[9] with Steve Kloves selected to write the screenplay.[22] Filming began on 29 September 2000 at Leavesden Film Studios and concluded on 23 March 2001,[23][24] with final work being done in July.[25] Principal photography took place on 2 October 2000 at North Yorkshire’s Goathland railway station.[26] Warner Bros. had initially planned to release the film over 4 July 2001 weekend, making for such a short production window that several proposed directors removed themselves from consideration. Because of time constraints, the date was put back, and Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone was released in the United Kingdom and the United States on 16 November 2001.[27]

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)[edit]

Harry, Ron, and Hermione return to Hogwarts for their second year, but a mysterious chamber, hidden in the school, is opened leaving students and ghosts petrified by an unknown agent. They must solve the mystery of the chamber, and discover its entrance to find and defeat the true culprit.

Columbus and Kloves returned as director, and screenwriter for the film adaptation of Chamber of Secrets.[10][11] Just three days after the wide release of the first film, production began on 19 November 2001[28] in Surrey, England, with filming continuing on location on the Isle of Man and at several other locations in Great Britain. Leavesden Film Studios in London made several scenes for Hogwarts.[29][30] Principal photography concluded in the summer of 2002.[29] The film spent until early October in post-production.[31] Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets premiered in the United Kingdom on 3 November 2002 before its wide release on 15 November, one year after the Philosopher’s Stone.[32][33]

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004)[edit]

A mysterious convict, Sirius Black, escapes from Azkaban and sets his sights on Hogwarts, where dementors are stationed to protect Harry and his peers. Harry learns more about his past and his connection with the escaped prisoner.

Columbus, the director of the two previous films, decided not to return to helm the third instalment,[10] but remained as a producer alongside Heyman.[34] Warner Bros. then drew up a three-name short list for Columbus’ replacement, which comprised Callie Khouri, Kenneth Branagh (who played Gilderoy Lockhart in Chamber of Secrets) and the eventual director Alfonso Cuarón.[12] Cuarón was initially nervous about accepting the job having not read any of the books, or seen the films, but later signed on after reading the series and connecting immediately with the story.[35][34] Michael Gambon replaced Richard Harris, who played Albus Dumbledore in the previous two films, after Harris’s death in October 2002.[36][37] Gambon was unconcerned with bettering or copying Harris, instead provided his own interpretation, including using a slight Irish accent for the role.[38] He completed his scenes in three weeks.[39] Gary Oldman was cast in the key role of Sirius Black in February 2003.[40] Principal photography began on 24 February 2003,[40] at Leavesden Film Studios, and concluded in October 2003.[41] Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban premiered on 23 May 2004 in New York.[42] It was released in the United Kingdom on 31 May, and in the United States on 4 June.[8] It was the first film in the series to be released in both conventional and IMAX theatres.[43]

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005)[edit]

After the Quidditch World Cup, Harry arrives back at Hogwarts and finds himself entered in the Triwizard Tournament, a challenging competition involving completing three dangerous tasks. Harry is forced to compete with three other wizards chosen by the Goblet of Fire – Fleur Delacour, Viktor Krum, and Cedric Diggory.

In August 2003, British film director Mike Newell was chosen to direct the film after Prisoner of Azkaban director Alfonso Cuarón announced that he would not direct the sequel. Heyman returned to produce, and Kloves again wrote the screenplay.[13] Principal photography began on 4 May 2004.[44] Scenes involving the film’s principal actors began shooting on 25 June 2004 at England’s Leavesden Film Studios.[45][46] Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire premiered on 6 November 2005 in London,[47] and was released in the United Kingdom and the United States on 18 November.[48] Goblet of Fire was the first film in the series to receive a PG-13 rating by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) for «sequences of fantasy violence and frightening images,»[49] M by the Australian Classification Board (ACB),[50] and a 12A by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) for its dark themes, fantasy violence, threat and frightening images.[51]

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007)[edit]

David Yates has directed every film in the franchise since Order of the Phoenix.

Harry returns for his fifth year at Hogwarts and discovers that the Wizarding World is in denial of Voldemort’s return. He takes matters into his own hands and starts a secret organisation to stand up against the regime of Hogwarts’ «High Inquisitor» Dolores Umbridge, as well as to learn practical Defence Against the Dark Arts (D.A.D.A) for the forthcoming battle.[52]

Daniel Radcliffe confirmed he would return as Harry Potter in May 2005,[53] with Rupert Grint, Emma Watson, Matthew Lewis (Neville Longbottom), and Bonnie Wright (Ginny Weasley) confirmed to return in November 2005.[54][55][56][57] In February 2006, Helen McCrory was cast as Bellatrix Lestrange,[58] but dropped out due to her pregnancy. In May 2006, Helena Bonham Carter was cast in her place.[59] Ralph Fiennes reprises his role as Lord Voldemort.[60] British television director David Yates was chosen to direct the film after Goblet of Fire director Newell, as well as Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Guillermo del Toro, Matthew Vaughn and Mira Nair, turned down offers.[61][62] Kloves, the screenwriter of the first four Harry Potter films, had other commitments and Michael Goldenberg, who had been considered for screenwriter of the series’ first film, filled in to write the script.[17] Principal photography began on 7 February 2006, and concluded at the start of December 2006.[63][64] Filming was put on a two-month hiatus starting in May 2006 so Radcliffe could sit his AS Levels and Watson could sit her GCSE exams.[65] Live-action filming took place in England and Scotland for exterior locations and at Leavesden Film Studios for interior locations.[66][67][68] Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix had its world premiere on 28 June 2007 in Tokyo, Japan,[69] and a UK premiere on 3 July 2007 at the Odeon Leicester Square in London.[70] The film was released in the United Kingdom on 12 July,[71] and the United States on 11 July.[72]

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2009)[edit]

Voldemort and his Death Eaters are increasing their terror upon the Wizarding and Muggle worlds. Needing him for an important reason, Headmaster Dumbledore persuades his old friend Horace Slughorn to return to his prior post at Hogwarts. During Slughorn’s Potions class, Harry takes possession of a strangely annotated school textbook, previously owned by the «Half-Blood Prince».[73]

In July 2007, it was announced that Yates would return as director.[15] Kloves returned to write the screenplay after skipping out of the fifth film, with Heyman and David Barron back as producers.[74] Watson considered not returning for the film,[75] but eventually signed on after Warner Bros. moved the production schedule to accommodate her exam dates.[76] Principal photography began on 24 September 2007,[77] and concluded on 17 May 2008.[78] Though Radcliffe, Gambon and Jim Broadbent (Slughorn) started shooting in late September 2007, other cast members started much later: Watson did not begin until December 2007, Alan Rickman (Severus Snape) until January 2008, and Bonham Carter until February 2008.[79][80] Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince had its world premiere on 6 July 2009 in Tokyo, Japan,[81] and was released in the United Kingdom and the United States on 15 July.[82]

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 (2010)[edit]

Harry, Ron, and Hermione leave Hogwarts behind and set out to find and destroy Lord Voldemort’s secret to immortality – the Horcruxes. The trio undergo a long journey with many obstacles in their path including Death Eaters, Snatchers, the mysterious Deathly Hallows, and Harry’s connection with the Dark Lord’s mind becoming ever stronger.[83]

Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson and Rupert Grint at the world premiere of Deathly Hallows – Part 2 on 7 July 2011 at Trafalgar Square in London.

Originally scheduled for a single theatrical release, on 13 March 2008, Warner Bros. announced that the film adaptation of Deathly Hallows would be split into two parts to do justice to the book and out of respect for its fans. Yates, director of the previous two films, was confirmed to return as director, and Kloves was confirmed as screenwriter.[84] For the first time in the series, Rowling was credited as a producer alongside Heyman and Barron, however Yates noted that her participation in the filmmaking process did not change from the previous films.[85][86] Pre-production began on 26 January 2009,[87] while principal photography began on 19 February at Leavesden Studios, where the previous six instalments were filmed. Pinewood Studios became the second studio location for shooting the seventh film.[24][88]

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 (2011)[edit]

Harry, Ron, and Hermione continue their search to find and destroy the remaining Horcruxes, as Harry prepares for the final battle against Voldemort.[89]

The film was announced in March 2008 as Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2, the second of two cinematic parts. It was also revealed that Yates would direct the film and that Kloves would write the screenplay.[84] Kloves started work on the second part’s script in April 2009, after the first part’s script was completed.[90] Deathly Hallows – Part 2 was filmed back-to-back with Deathly Hallows – Part 1 from 19 February 2009 to 12 June 2010,[91][24][92] and treated as if it were one film during principal photography.[93] Reshoots were confirmed to begin in the winter of 2010 for the film’s final, and epilogue scenes, which had originally taken place at London King’s Cross station. The filming took place at Leavesden Film Studios on 21 December 2010,[94] marking the end of the Harry Potter series after ten years of filming.[95]

The film had its world premiere on 7 July 2011 in Trafalgar Square in London,[96] and a U.S. premiere on 11 July at Lincoln Center in New York City.[97] Although filmed in 2D, the film was converted into 3D in post-production and was released in both RealD 3D and IMAX 3D,[98] becoming the first film in the series to be released in this format.[99] The film was released on 15 July in the United Kingdom and the United States.[96]

Fantastic Beasts films[edit]

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016)[edit]

Harry Potter author J. K. Rowling wrote and produced the three films in the Fantastic Beasts series and produced the last two Harry Potter films.

In 1926, Newt Scamander arrives in New York City with his magically expanded briefcase which houses a number of dangerous creatures and their habitats. When some creatures escape from his briefcase, Newt must battle to correct the mistake, and the horrors of the resultant increase in violence, fear, and tension felt between magical and non-magical people (No-Maj).[105]

On 12 September 2013, Warner Bros. announced that J. K. Rowling was writing a script based on her book Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and the adventures of its fictional author Newt Scamander, set seventy years before the adventures of Harry Potter. The film would mark her screenwriting debut and is planned as the first movie in a new series.[106] According to Rowling, after Warner Bros. suggested an adaptation, she wrote a rough draft of the script in twelve days. She said, «It wasn’t a great draft but it did show the shape of how it might look. So that is how it all started.»[107] In March 2014, it was revealed that a trilogy was scheduled with the first instalment set in New York.[108] The film sees the return of producer David Heyman, as well as writer Steve Kloves, both veterans of the Potter film series.[109][102] In June 2015, Eddie Redmayne was cast in the lead role of Newt Scamander, the Wizarding World’s preeminent magizoologist.[110] Other cast members include: Katherine Waterston as Tina Goldstein, Alison Sudol as Queenie Goldstein, Dan Fogler as Jacob Kowalski, Ezra Miller as Credence Barebone, Samantha Morton as Mary Lou Barebone, Jenn Murray as Chastity Barebone, Faith Wood-Blagrove as Modesty Barebone, and Colin Farrell as Percival Graves.[111] Principal photography began on 17 August 2015, at Warner Bros. Studios, Leavesden.[112] After two months, the production moved to St George’s Hall in Liverpool, which was transformed into 1920s New York City.[113] Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them was released worldwide on 18 November 2016.[114]

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald (2018)[edit]

A few months have passed since the events of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. Gellert Grindelwald has escaped imprisonment and has begun gathering followers to his cause – elevating wizards above all non-magical beings. Dumbledore must seek help from his former student Newt to put a stop to Grindelwald.[115]