Wiki User

∙ 11y ago

Best Answer

Copy

Jose Rizal

Geraldine Davis ∙

Lvl 10

∙ 1y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

More answers

Wiki User

∙ 11y ago

Copy

Jose Rizal

This answer is:

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: Whose last words were ‘It is done’?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

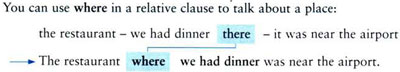

В английском языке существует категория относительных местоимений – relative pronouns, основная функция которых – присоединять придаточные предложения к главным. Они могут выступать в качестве союзных слов, а значит, могут являться членами предложения.

Самыми используемыми из относительных местоимений являются who, which, that. Их зачастую путают. Причина этому: в зависимости от контекста они могут иметь одинаковый перевод.

Английское местоимение Who

- Местоимение переводится как «кто/который». Употребляется, когда речь идёт об одушевлённых лицах (люди, животные). В придаточных предложениях выступает в роли подлежащего или дополнения. Сказуемое, идущее после, может быть в единственном и множественном числе.

Например:- There are a lot of volunteers here who she asked to help with organization of the event. — Здесь много волонтёров, которых она попросила помочь с организацией этого мероприятия (who – дополнение).

- I have never met a person who has such a strong wish to win. — Я никогда не встречал человека, который так сильно желает выиграть (who – подлежащее).

- В вопросах используется в качестве:

- Подлежащего. Глагол, следующий за местоимением в таком вопросе, употребляется в единственном числе. Есть исключение: случаи, когда мы знаем, что последует ответ во множественном числе.

Например:- Who were sitting there? — Кто здесь сидел? Заметьте: в вопросах к подлежащему вспомогательный глагол не нужен.

- Who wrote this novel? — Кто написал этот роман?

- Who has already finished the test? — Кто уже закончил тест?

- Остальные же виды вопросов требуют вспомогательного глагола:

- Who did you come to? — К кому ты пошёл?

- Who hasn’t you told about it yet? — Кому ты ещё не сказал об этом?

- Именной части сказуемого. Глагол-связка в данном случае стоит в том же числе и лице, что и следующее за ним подлежащее.

Например:- Who is this man? — Кто этот мужчина?

- Who are these people standing at the bus stop? — Кто эти люди, стоящие на автобусной остановке?

- Подлежащего. Глагол, следующий за местоимением в таком вопросе, употребляется в единственном числе. Есть исключение: случаи, когда мы знаем, что последует ответ во множественном числе.

- Используется в эмфатических оборотах, призванных уделить большее внимание подлежащему, подчеркнуть/усилить его значение. Структура такого оборота – “It is/was…who…”. Грамотнее перевести его, используя слово «именно».

Например:- It was our school’s teacher who helped me to overcome all difficulties. — Именно учительница нашей школы помогла мне преодолеть все трудности.

ARVE Error: Mode: lazyload not available (ARVE Pro not active?), switching to normal mode

Английское местоимение Which

Which переводится «кто/который/какой», используется, когда речь идёт о неодушевлённых предметах или животных.

Возьмите на заметку, что это местоимение используется, когда мы говорим о выборе из ограниченного числа.

Как и предыдущее местоимение, which в повествовательных вопросах употребляется как дополнение или подлежащее:

- It is the recipe which I created. — Это рецепт, который придумала я (which – дополнение).

- Don’t forget about the notes about which I told earlier. — Не забудь о заметках, о которых я говорила ранее (which – дополнение).

- The new recipe which was published in the magazine draws a lot of attention. — Новый рецепт, который был опубликован в журнале, привлекает много внимания (which – подлежащее).

- My sister has become a famous singer who has many fans all around the world. — Моя сестра стала известной певицей, у которой много фанатов во всем мире (which – подлежащее).

В вопросах используется в качестве:

- Местоимения-существительного (обычно идёт в паре с предлогом of):

- Which of these articles did you write last week? — Какие из этих статей ты написал вчера?

- Which of you will pay for the dinner? — Кто из вас будет платить за обед.

- Which of your friends had the same job as mine? — У кого из твоих друзей была такая же работа, как у меня?

- Местоимения-прилагательного:

- Which course have you chosen? — Какой курс ты выбрал?

- Which colors are your favorites? — Какие у тебя любимые цвета?

- Which fruits do you prefer? — Какие фрукты ты предпочитаешь?

- В некоторых вопросах может использоваться и which, и what без изменения смысла или стиля. Но сейчас чаще употребляется вариант с what.

Например:- What/which city do you want to live in? — В каком городе ты хочешь жить?

Запомните: в вопросах после which существительное пишется без артикля.

В английских предложениях, где местоимение идёт с предлогом (примеры: «с которым», «к которому»), предлоги выносятся в конец предложения:

- Where is the key which I was looking for? — Где ключ, который я искал?

Английское местоимение That

Правила употребления:

That используется с одушевленными лицами и неодушевлёнными объектами. Переводится как прошлые 2 местоимения. Призвано соединять определительные придаточные предложения в составе сложного. Употребляется только в придаточных ограничительных, о которых ещё будет упомянуто в статье.

Примеры:- A man that is standing outside is our new colleague. — Мужчина, который стоит на улице — наш новый коллега.

- Please, buy a plant that is in a pink pot as she adores this color. — Пожалуйста, купи растение, которое в розовом горшке, так как она обожает этот цвет.

- Who has planted a tree that grows near the school? — Кто посадил дерево, которое растёт рядом со школой?

- Don’t disturb a person that is sitting in front of you now. — Не отвлекай человека, который сейчас сидит перед тобой.

- В отличие от предыдущих местоимений who и which это местоимение не может употребляться в вопросительных предложениях на первом месте. Нельзя сказать “That film do you prefer?”. Правильно будет выбрать вариант “Which/what film do you prefer?”.

- Употребляется в эмфатических оборотах, о которых уже было написано выше. Конструкция “It is/was…that…”.

Например:- It is Mary that he cares about most. — Именно о Мэри он заботится больше всего.

- Служит, чтобы заменить написанное до этого существительное во избежание тавтологии:

- The price of a new fridge is much higher than that of the old one. — Цена нового холодильника намного выше, чем старого.

- That применяется и в других случаях: в качестве союза или подлежащего. Тогда оно уже не будет относительным местоимением.

Например:- Tell him that I will be late so there is no need to hurry. — Скажи ему, что я опоздаю, поэтому можно не торопиться.

Who, Whose, Whom – правило

Относительное местоимение who в косвенных падежах имеет форму whom. Чаще используется в официальной и письменной речи, в разговорной заменяется на that.

Примеры:

- The Minister whom I sent my report yesterday turns out to be our family’s friend. — Министр, которому я вчера отправил свой доклад, оказался другом нашей семьи.

- Would you mind if I tell Mr. John whom I have chosen for this job. — Вы не возражаете, если я скажу мистеру Джону, кого я выбрал для этой работы?

Местоимение whose переводится как «чей», указывает на принадлежность кому-то/чему-то:

- Whose notebook did you take? — Чью тетрадь ты взял?

- Do you remember Skylar whose daughter works as a doctor in the local hospital? — Ты помнишь Скайлар, чья дочь работает доктором в местной больнице?

ARVE Error: Mode: lazyload not available (ARVE Pro not active?), switching to normal mode

Когда можно опустить?

Относительные местоимения пропускаются, если не играют роль подлежащего. В таких случаях их можно убрать без потери смысла, и предложение останется грамматически правильным. Это явление особенно распространенно в разговорном английском.

Следует взять на заметку: такие придаточные определительные предложения с опущенным относительным местоимением в английском обычно не обособляются. Из-за этого понять предложение бывает трудно.

Примеры:

- Is it the bag (that) you are looking for right now? — Это сумка, которую ты сейчас ищешь?

- The teacher (that) I told you about knows 4 foreign languages! — Учитель, о котором я тебе рассказывала, знает 4 иностранных языка!

- The director of the theatre (that) you see every day lives in your quarter? — Директор театра, которого ты видишь каждый день, живёт в твоём квартале.

Но если в предложении относительное местоимение является подлежащим, опускать его нельзя.

Сравните:

- The T-shirt (that) I bought is so expensive. — Футболка, которую я купил, очень дорогая.

- Don’t wear a T-shirt which lies on my bed. — Не надевай футболку, которая лежит на моей кровати.

Во втором примере местоимение не может быть опущено, так как играет роль подлежащего.

Какие бывают предложения с Who, Which и That в английском языке?

Эти относительные местоимения могут использоваться в вопросительных, отрицательных и утвердительных предложениях, например:

- Who did you go for a walk with? — С кем ты ходил гулять?

- It is not the information which I have asked for. — Это не та информация, которую я просил.

- It is the first book that I can’t read without tears. — Это первая книга, которую я не могу читать без слёз.

В английском существуют описательные и ограничительные (ограничивающие) определительные придаточные предложения. Ограничительное придаточное тесно связано с тем членом предложения, к которому оно относится, и не может быть опущено без изменения смысла. Обычно не выделяется запятой.

Пример:

The geometric figure that has no angles is a circle. — Геометрическая фигура, у которой нет углов, – это круг.

Описательное придаточное вводит дополнительную информацию о предмете и лице, которое оно описывает, и может быть убрано без изменения смысла. В таких предложениях придаточное выделяется запятыми.

Например:

- The city, which my friend likes to travel, is considered one of the oldest cities. — Город, в который мой друг любит путешествовать, считается одним из самых старинных городов.

Сравните:

- The building that has a lot of pretentious decorations refers to baroque. — Здание, которое имеет много напыщенных декоративных элементов, относится к барокко.

Здесь придаточное предложение нельзя убрать, иначе получится, что любое здание относится к барокко. - The local bank, which was built in 1990, is a leader of the industry nowadays. — Местный банк, который был построен в 1990 году, на сегодняшний день является лидером индустрии.

Придаточное вводит дополнительную информацию, которую можно опустить, ведь самое главное – то, что банк является лидером индустрии, а не то, когда он был построен.

Если Вы устали учить английский годами?

Наши читатели рекомендуют попробовать 5 бесплатных уроков курса «АНГЛИЙСКИЙ ДО АВТОМАТИЗМА» с Анастасией Божок.

Те, кто посещают даже 1 урок узнают больше, чем за несколько лет!

Удивлены?

Получите 5 бесплатных уроков здесь…

Без домашки. Без зубрежек. Без учебников

Из курса «АНГЛИЙСКИЙ ДО АВТОМАТИЗМА» Вы:

- Научитесь составлять грамотные предложения на английском без заучивания грамматики

- Узнаете секрет прогрессивного подхода, благодаря которому Вы можете сократить освоение английского с 3 лет до 15 недель

- Будете проверять свои ответы мгновенно + получите доскональный разбор каждого задания

- Скачаете словарик в форматах PDF и MP3, обучающие таблицы и аудиозапись всех фраз

Получить 5 уроков бесплатно можно тут

Who или That?

Who опять же является более официальным вариантом и чаще употребляется в письменной речи. Оба местоимения используются для описания одушевлённых лиц.

Но есть случаи, в которых предпочтительнее использовать один из вариантов, хотя строгих правил нет, но все же:

- Когда мы описываем людей, можно ставить оба местоимения. Но при описании определённой черты, способности, лучше выбирать местоимение that.

Например:- My grandmother is the person that looks cheerful every day. — Моя бабушка – человек, который каждый день выглядит бодрым.

- Tom is a boy that constantly fights with his disease. — Том – это мальчик, который постоянно борется со своей болезнью.

- Если придаточное предложение в официальной речи указывает на конкретную личность, то желательно использовать who.

Например:- The doctor who leads the hospital has got financial support from the state. — Доктор, которая возглавляет эту больницу, получила финансовую поддержку от государства.

- A woman who is standing in front of you is our new manager. — Женщина, которая стоит перед вами, наш новый менеджер.

С собирательными существительными используется who, в эту категорию существительных относятся такие слова, как:

company – компания;

family – семья;

group – группа;

audience – зрители;

army – армия;

police – полиция;

people – люди;

team – команда;

jury – жюри и множество других слов.

Примеры:

- The football team who lost competitions last month is training hard these days. — Футбольная команда, которая проиграла соревнования в прошлом месяце, сейчас упорно тренируется.

- The audience who came to the concert had fun all the time and supported all artists. — Зрители, которые пришли на концерт, всё время веселились и поддерживали всех артистов.

Which или That?

И which, и that могут использоваться, когда речь идёт о неодушевленных объектах. Разница в том, что which можно назвать более книжным вариантом. Кроме того, which подразумевает выбор из какого-то ограниченного количества.

That предпочтительнее использовать, когда:

- Перед ним стоят слова something, nothing, anything, all, few, much, many.

Например:- Do you have something that will be interesting for me? — У тебя есть что-нибудь, что будет мне интересно?

- I have so many tasks for today that I need to do. — У меня так много заданий на сегодня, которые мне нужно сделать.

- После порядковых местоимений:

- It is the first day that seems to be boring. — Это первый день, который кажется скучным.

- It is the 3rd lesson that I have missed. — Это третий урок, который я пропустил.

- После превосходной степени прилагательных:

- It is the most touching story that I have ever heard. — Это самая трогательная история, которую я когда-либо слышала.

- Your brother is the most good-natures person that I have ever met. — Твой брат – самый добродушный человек из всех, кого я когда-либо встречал.

Важно – that редко используется в роли подлежащего. То есть если в сложном предложении есть придаточное определительное, которое даёт больше информации о неодушевлённом предмете, то в качестве подлежащего чаще выступает не that, а which. Пример: The meal which was cooked yesterday refers to Chinese cuisine. Блюдо, которое было вчера приготовлено, относится к китайской кухне (хотя that подходит, в таких случаях его не ставят).

Таблица критериев выбора местоимений для предложений

| Местоимение | Who | Which | That |

| Существительные, с которыми они употребляются. | Одушевлённые (люди и животные). Вопрос – кто? | Неодушевлённые (неживые предметы, явления, собирательные существительные). Основной вопрос – что? | Любые существительные. |

| Формальность. | Чаще используется в официально-деловой и письменной речи. | Чаще используется в официально-деловой и письменной речи. | Чаще используется в разговорной речи. |

| Тип предложения. | Описательное/ограничительное. | Описательное/ограничительное. | Ограничительное. |

ARVE Error: Mode: lazyload not available (ARVE Pro not active?), switching to normal mode

Заключение

Данная тема не так сложна для понимания, однако, содержит много нюансов, обязательных к изучению. Рекомендуем составить собственную таблицу, где будут прописаны все указанные выше тонкости, исключения, особенности и приведён пример на каждый пункт.

Чтобы не путать местоимения и помнить разницу в использовании между ними, нужно знать:

- с какими существительными (одушевлённым/неодушевлённым) они употребляются;

- в каких придаточных предложениях (ограничительных/описательных);

- в официальной/разговорной речи;

- конкретные случаи употребления и исключения.

Эти пункты помогут вам разобраться в большом объёме информации и структурировать её удобным образом. Не забывайте периодически просматривать правило употребления этих местоимений, чтобы освежить и закрепить его в памяти.

Переведи-ка на английский язык: «Это дом, который построил Джек».

Каким словом ты переведешь «который»? Which? Или that? А может who?!

Запутаться в этих словах с непривычки – легко. Разобраться с ними – еще легче. 🙂 В помощь наша статья.

Who, which, that – это местоимения. Когда они соединяют две части сложного предложения, на русский язык все три слова переводятся словом «который».

– Here are some cells which have been affected. (Вот некоторые ячейки, которые были повреждены).

– This is a man who takes his responsibilities seriously. (Это человек, который серьезно относится к своим обязанностям).

– They’re the people that want to buy our house. (Это люди, которые хотят купить наш дом).

В этом и сложность для нас – мы можем не увидеть разницы. Итак, начнем с противопоставления who и which.

Правило Who-Which, или Смотри не перепутай!

| ⠀Who | ⠀Which |

| Когда говорим о людях:

I know someone who can help you. (Я знаю кое-кого, кто может вам помочь).⠀ |

Когда говорим о вещах:

Where is the cellphone which was on the table? (Где телефон, который лежал на столе?) |

Вот и вся разница. 🙂 Также which используется, когда придаточное относится не к какому-то конкретному слову, а ко всему предложению:

We’re starting to sell electric cars, which is great. (Мы начинаем продавать электромобили, что здорово).

Но это, разумеется, не конец статьи. Что насчет that?

В неформальной речи that может заменять как who, так и which. Но опять же все не так просто.

That и which: употребление

В одних предложениях ты можешь использовать оба местоимения:

– The movie that/which I saw last weekend was great. (Кино, которое я посмотрел на прошлых выходных, было классным)

– The table that/which I bought from ikea was cheap. (Стол, который я купил в Икее, был дешевым).

Сюда же относится и наш пример с Джеком:

– This is the house that Jack built (в оригинале that, но можно использовать which).

Теперь сравни:

– Harry Potter, which I finished last week, was an excellent book. (Гарри Поттер, которого я дочитал на прошлой неделе, – прекрасная книга).

– Toronto, which is heavily populated, is a multicultural city. (Торонто, который густо населен, является мультикультурным городом).

Обрати внимание: в этих примерах мы уже не можем использовать that и обособляем придаточное запятыми. В чем разница?

Первые 2 примера называются Defining relative clauses. В этих предложениях мы не могли «выкинуть» без потери смысла часть, присоединенную which/that:

The movie that/which i saw last weekend was great. (А какое кино? Извольте уточнить!)

The table which/that i bought from ikea was cheap. (А какой именно стол? Тоже хочу дешевый стол!)

Вторые предложения называются Non-defining relative clauses. Если мы выкинем придаточную часть с which, предложение все равно будет иметь смысл:

Toronto, which is heavily populated, is a multicultural city.

Harry Potter, which I finished last week, was an excellent book.

В таких предложениях нельзя использовать that и нужны запятые. Об этом же правиле ты можешь посмотреть крутое видео от engvid (заодно потренировать аудирование).

А подробнее о пунктуации тут: Запятые в английском, или Как не съесть бабушку на ужин.

Употребление that и who

В неформальной речи ты можешь использовать that вместо who, хотя экзаменаторы это не оценят. В качестве иллюстрации разговорной речи возьмем песенные примеры:

Aerosmith: «I’m the one that jaded you».

Katy Perry: «I don’t have to say you were the one that got away».

Но и здесь повторяется история с Non-defining relative clauses.

Сравни с примерами из песен эти предложения:

– Alice, who has worked in Brussels ever since leaving Edinburgh, will be starting a teaching course in the autumn. (Элис, которая работала в Брюсселе с тех пор, как покинула Эдинбург, начнет курс обучения осенью).

– Clare, who I work with, is doing the London marathon this year. (Клэр, с которой я работаю, организует Лондонский марафон в этом году).

Такое же правило: если мы можем выкинуть часть предложения – она несет лишь дополнительную информацию, без нее предложение не потеряет смысл – то мы не используем that и выделяем придаточное запятыми.

Who / whose, whom – правило

Whom – это объектный падеж для who. Переводится как наше «которого, которому, которым, о котором». То есть все, кроме именительного падежа – «который».

Whom используется, когда придаточное предложение относится НЕ к подлежащему (=кто выполняет действие):

– That’s the guy whom she married. (Это парень, за которого она вышла замуж)

Whom относится к слову guy (парень), но подлежащее в придаточном – she (она). Именно она вышла замуж – выполнила действие. Еще больше примеров в видео от engvid.

Whom – книжный вариант, в устной речи обычно заменяется на who или that, или просто опускается.

– He was talking to a man (whom, who, that) I have never seen before. (Он разговаривал с человеком, которого я никогда раньше не видел.)

Вот как реагируют на тех, кто пытается использовать whom 🙂

Whose – переводится, как наше «чей, чья, чье».

– She’s now playing a woman whose son was killed in the First World War. (Сейчас она играет женщину, чей сын был убит в Первой мировой войне).

Когда можно опустить?

Как мы сказали выше, whom можно опустить. То же самое относится к which, that и who. Когда это можно сделать? Объяснить будет трудновато, но я постараюсь.

Сравни:

| ⠀Можно опустить | ⠀Нельзя опустить |

| Come and look at this photo which Carina sent me.⠀ | He ordered coffee which was promptly brought.⠀ |

Видишь разницу? Если нет, то давай разбираться. Возьмем лишь придаточные предложения и рассмотрим их отдельно:

…which Carina sent me (которую Карина скинула мне).

…which was promptly brought (который был принесен сразу).

– В первом случае подлежащее (=действующее лицо) – Carina. Which – дополнение. В таком случае which можно опустить.

– Во втором случае подлежащее – само местоимение which (именно оно было принесено). Подлежащее слишком важно. Его опускать нельзя.

А когда подлежащим является who, его не только нельзя опускать, но и заменять на that:

This is the man who wants to see you. (Это человек, который хочет встретиться с тобой).

Да и в целом осторожнее заменяй who на that. Когда речь идет о людях, лучше использовать who. Тогда точно не ошибешься.

Еще один шаг к пятерке!

Оказалось, все не так сложно, правда? Предлагаем тебе разобраться и с другими темами грамматики с помощью онлайн-курса на Lingualeo и грамматических тренажеров (бесплатные тренировки, доступны после регистрации).

Какая разница между who, which и that?

В английском языке можно встретить ряд местоимений, которые могут не просто замещать существительные, но служат для объединения двух предложений в одно — главного и и придаточного. В первую очередь мы имеем ввиду английские местоимения who, which и that. Эти местоимения принято называть соединительными или относительными. Часто в эту группу включают whom.

Мы рассмотрим каждое слово, дадим общие рекомендации по использованию того или иного английского местоимения в соответствии с правилами грамматики и разберем их использование на практике.

Для начала следует понимать, что относительные (Relative pronouns) и соединительные (Conjunctive pronouns) местоимения — это разные группы.

I have a friend who can draw well. — У меня есть друг, который здорово рисует./ То есть мы узнаем, какой именно это друг — хорошо рисующий.

Do you know, who wrote this book? — Вы знаете, кто написал эту книгу?/ Здесь местоимение объединяет два предложения и не дает определение никому.

Хотя они могут быть выражены одними и теми же словами и даже иметь одинаковый перевод на русский язык, эти местоимения выполняют разные функции в предложении. Основной целью нашей статьи является помочь вам в выборе нужного слова, а не дать классификацию местоимений. Исходя из этого, мы расскажем об особенностях каждого слова, не зависимо от их группы.

Каждое из представленных местоимений можно перевести с английского языка “какой”, “который”. Местоимения НЕ являются взаимозаменяемыми. О причинах мы поговорим далее.

Английское местоимение Who

Это местоимение можно использовать только в отношении человека. Помните, в английском языке не достаточно быть одушевленным существительным, как, например, кошка или лошадка. Многие грамматические правила, связанные с местоимениями, делят существительные на категорию “человек” — “не человек”.

This is a song about a man who sold the world. — Это песня о человеке, который продал мир.

Let’s find out who killed who. — Давайте узнаем, кто кого убил.

Так как слово, выполняющее функцию подлежащего предполагает именно лицо, персону, то мы используем местоимение ‘who’.

У этого местоимения есть падежная форма ‘whom’ — “которого”, “какого”. Это слово в английском предложении выражает дополнение в придаточной части:

Do you remember whom did you tell about it? — Ты помнишь, кому рассказал об этом?

Однако многие лингвисты и филологи рассматривают эту форму как книжную. В разговорной речи она чаще всего заменяется на ‘that’.

Английское местоимение Which

Местоимение ‘which’ так же переводится “который”, “какой”, но в отличие от предыдущего слова может употребляться только по отношению к неодушевленным предметам и животным, то есть к “не людям”.

Sally dodn’t remember which way to go. — Сэлли не помнила, по какой дороге идти.

Принято считать, что местоимение ‘which’ является более книжным вариантом ‘that’, который можно чаще встретить в разговорной речи. Однако не всегда эти слова могут замещать друг друга. ‘That’ никогда не будет использоваться как подлежащее в придаточном предложении:

Tell me, which car is yours? — Скажи, какая машина твоя?

Это важный момент, на который следует обратить внимание. Местоимение ‘that’, о котором сейчас пойдет речь очень часто замещает в речи ‘who’ или ‘which’, если они являются относительными.

НО ‘that’ никогда не используется в качестве соединительного местоимения.

Английское местоимение That

Итак, мы с вами определились, что это английское местоимение является относительным. Его прелесть заключается в том, что оно может заменять практически любое относительное местоимение не зависимо от того, за каким существительным оно закреплено — одушевленным или неодушевленным, будь то человек или животное:

Когда используются which, that и who

В этой статье мы рассмотрим случаи, когда употребляется which, а когда — that, в чем разница употребления. Затронем также и употребление who в придаточных определительных предложениях в английском.

Иногда which и that взаимозаменяемы:

What’s the name of the river which/that goes through the town? — Как называется река, которая протекает по территории города?

То же самое касается that и who (когда речь идет о людях):

What’s the name of the man who/that lives next door? — Как зовут мужчину, который живет по соседству?

Who и which употребляются в более формальных ситуациях.

Но употребление зависит также от типа придаточного предложения. Если вы не знаете, что это, следующий абзац немного освежит память.

Что такое придаточное предложение (relative clause)

Простыми словами, придаточные предложения добавляют информацию к основному. В русском языке они обычно отделяются от основного предложения запятой. Зачастую их можно отбросить без потери смысла.

Когда мы имеем дело с относительными местоимениями that, which и who, здесь нужно рассмотреть придаточные определительные.

Придаточное определительное (defining/identifying clause)

Также называются restrictive.

Такие предложения уточняют, о ком или о чем конкретно мы говорим. Если их выбросить, то это отразится на смысле всего предложения.

В определительных предложениях чаще принято использовать THAT (но можно использовать и which). Если речь о людях, используется также who.

The woman who/that visited me in the hospital was very kind. — Женщина, которая навещала меня в больнице, была очень добра. (Если оставить «женщина была очень добра» — непонятно, о ком идет речь).

The umbrella that/which I bought last week is already broken. — Зонт, который я купил на прошлой неделе, уже сломался. (Без придаточного получается «Зонт уже сломался» — какой именно зонт?)

Как вы могли заметить, в таких случаях мы не ставим запятые.

Придаточное неопределительное (non-defining clause)

Также называются non-restrictive.

Такие предложения добавляют информацию, которую можно выбросить из предложения, не потеряв сути. Т. е. они дают информацию, которая не является обязательной для упоминания.

В таких предложениях употребляется WHICH. При упоминании людей используется who.

Elephants, which are the largest land mammals, live in herds of 10 or more adults. — Слоны, самые большие земные млекопитающие, живут в стадах из 10 и более взрослых особей. (Про самых больших млекопитающих — скорее, необязательное энциклопедическое уточнение).

The author, who graduated from the same university I did, gave a wonderful presentation. — Автор, который закончил тот же университет, что и я, дал замечательную презентацию. (Здесь говорящий просто замечает, что автор учился с ним в одном заведении. Можно также добавить «кстати»).

Также если мы говорим о принадлежности, можно использовать местоимение whose (чей):

The farmer, whose name was Fred, sold us 10 pounds of potatoes. — Фермер, чье имя было Фред (которого звали Фред), продал нам 10 фунтов картофеля. (Опять же, информация о его имени не важна, смысл в том, что он продал нам картошку).

Неопределительные придаточные выделяются запятыми.

That в неопределительных предложениях НЕ используется:

The area, which has very high unemployment, is in the north of the country.

The area, that has very high unemployment, is in the north of the country.

Если правило показалось вам немного размытым и непонятным, давайте рассмотрим еще пару примеров, чтобы сравнить придаточные определительные после which и that.

The car that he bought is very expensive. — Машина, которую он купил, очень дорогая. (Придаточное предложение содержит важную информацию — мы говорим конкретно о машине, которую он купил).

He bought a car, which is very expensive. — Он купил машину, которая очень дорогая. (Здесь нам важно сказать о том, что он купил машину. Информация о том, что она дорогая, не так важна.)

Надеюсь, теперь вам стало понятно, чем отличается which от that и как их правильно употреблять в предложении. Если остались какие-то вопросы, задавайте их в комментариях.

Наконец, предлагаю вам выполнить упражнения в виде теста, чтобы закрепить урок на практике.

Правило употребления who which

Who (или Whom) является местоимением, и используется говорящим в качестве подлежащего или дополнения глагола, чтобы указать, о каком человеке идет речь, либо чтобы ввести какую-либо дополнительную информацию о только что упомянутом человеке. Это местоимение может употребляться только по отношению к одушевленным лицам.

Which является местоимением, и используется говорящим в качестве подлежащего или дополнения глагола, чтобы указать, о какой вещи или вещах идет речь, либо чтобы ввести какую-либо дополнительную информацию о только что упомянутой вещи. Это местоимение может употребляться только по отношению к неодушевленным предметам.

That является местоимением, и используется говорящим в качестве подлежащего или дополнения глагола, чтобы указать, о каком человеке или о какой вещи идет речь, либо чтобы ввести какую-либо дополнительную информацию о только что упомянутом человеке или вещи. Это местоимение может употребляться по отношению как к одушевленным лицам, так и к неодушевленным.

Все эти местоимения в некоторых случаях могут опускаться (для подробностей смотрите относительные местоимения).

Например:

The girl who was hungry.

Девочка, которая была голодна.

The boy whom I talked to.

Мальчик, с которым я разговаривал.

The dog that wagged its tail.

Пес, который вилял хвостом.

The software (that) I wrote.

Программное обеспечение, которое написал я.

The company, which / that hired me.

Компания, которая наняла меня.

Вопросительные местоимения.

1. Вопросительные местоимения — это и есть относительные местоимения ( what, who, whom, which, whose ), только используются в сложном повествовательном предложении для соединения главного предложения с придаточным.

Синтаксическая функция относительных местоимений (what, who, whom, which, whose ). В то же время внутри придаточного предложения эти местоимения выполняют самостоятельную синтаксическую функцию (подлежащего, дополнения, определения).

The woman, who is from London, speaks Irish.

Тот женщина, которая родом из Лондона, говорит по-ирландски (подлежащее).

Не always says what he thinks.

Он всегда говорит то, что думает (дополнение).

That is the doll which I bought for my daughter.

Это кукла, которую я купила для своей дочери (дополнен.).

Употребление that вместо относительных местоимений what, who, whom, which, whose в придаточном предложении.

Вместо относительных местоимений what, who, whom, which, whose в придаточном предложении может употребляться относительное местоимение that — которые, который по отношению как к одушевленому так и к неодушевленному предмету (Но: после запятой и предлогов that не употребляется)These are the tables which they bought 2 weeks ago.These are the tables that they bought 2 weeks ago.

Это столы, которые они купили две неделе назад.

Употребление Whose. 2. Whose как относительное местоимение употребляется как с неодушевленным , так и с предметам одушевленными и непосредственно стоит перед существительными, к которому местоимение относится.

Do they happen to call the young women whose names are Jill and Jim Peterson?

Вы случайно не звонили молодым женщинам,по имени которогоДжил и Джим Питерсоны?

The mountains whose tops were covered with snow looked magnificent.

Горы, вершины которых (чьи вершины) были покрыты снегом, вы-глядели величественно.

Употребление that, which, who в неофициальной речи.

3.

В неофициальной речи that, which, who как относительные местоимения могут опускаться, кроме тех случаев, когда местоимение выполняет функцию подлежащего в придаточном предложении.

I saw some people I knew personally.Я увидел людей, которых знал лично.The boy, who (подлеж.) has broken the chair is her son.

Мальчик, который сломал этот стул, ее сын.

Предлог при относительном местоимении. 4. Предлог (при относительном местоимении, когда опускается, остается) в предложении ставится после глагола и после дополнения (при его наличии).

That’s the hotel in where ( which ) we stayed.

That’s the hotel they stayed in.

Это мотель, в котором мы остановились.

Употрбление which .

5. Относительное местоимение which может вводить придаточное предложение, которое относится не к отдельному слову, а ко всему главному предложению и отделяется от него запятой. В этом случае оно соответствует русскому местоимению что.Не informed me about it in time, which helped me very much.

Он сообщил мне об этом вовремя, что очень сильно мне помогло.

Упражнения: Выберите правильный вариант ответа1. The coach, which / who was appointed just last week, made no comment on the situation.2. Isn’t that the street which / where the accident happened last night?3.

The human brain, which / what weighs about 1400 grammes, is ten times the size of a baboon’s.4. There are several reasons where / why I don’t want to talk to Mike.5. This is the university which / where I work.6. The new guy in our group who’s / whose name is Alex, seems really nice.7.

All the friends to who / whom the e-mail was sent replied.8. February 14th where / when we express our love to each other, is known as St.Valentine’s Day.9. A very popular breed of dog is the German Shepherd what / which is often used as a guard dog.10.

The unsinkable Titanic sank on her maiden voyage, what / which shocked the whole world. Keys:1-who2-where3-which4-why5-where6-whose7-whom8-when9-which

10-what

Упражнение Выберите правильный вариант ответа ‘1. There were none of my biscuits left when I had a cup of tea, . was really annoying.1) what 3) which

2) why 4) who

2. We have just bought a new webcamera . takes clear pictures.1) who 3) where

2) which 4) what

3. The Godfather was made by Francis Ford Copolla, . daughter is alsoa film director.1) whose 3) who’s

2) whose’s 4) whos’s

4. Do you know any reason . Sally should be angry with me?1) which 3)why

2) where 4) when

5. Here is a photo of the hotel . we stayed when we were in Sydney.1) which 3)when

2) what 4) where

6. How do you think the first man . went into space felt?1) what 3)whom

2) whose 4) who

7. This is the first occasion on . the directors of these well-known companies have met.1) which 3) when

2) what 4) where

8. She is a person for . very few people feel much sympathy.1) who 3) which

2) whom 4) why

9. The moment . the heroine suddenly appears at the ball is the most exciting moment in the whole film.1) which 3) when

2) what 4) where

10. We met a woman . had a dog with only three legs.1) whose 3) which

2) whom 4) who

Относительные и соединительные местоимения (who, whom, what, which, whose, that) — На Отлично!

В эту группу, как вы видите, входят те же вопросительные местоимения плюс местоимение that, которое не имеет самостоятельного (особого) значения, но часто употребляется вместо who, whom, which в обычной разговорной речи.

Они служат для связи придаточного предложения с главным (как и союзы) и, кроме того, выполняют в придаточном предложении функции членов предложения (подлежащего, дополнения и др.). По их синтаксической функции в сложноподчиненном предложении они могут выступать в роли как относительных, так и соединительных местоимений.

WHO – который, кто – именительный падеж WHOM – которого – объектный падеж WHOSE- который, которого WHICH- который, которого WHAT- то что; что

THAT- который, которого

1) Относительные местоимения (Relative -относительный pronouns) вводят определительные придаточные предложения и на русский обычно переводятся словом который, -ая, -ое, -ые.

Они всегда относятся к конкретному, определяемому слову (обычно существительному, местоимению) в главном предложении. В придаточном предложении выполняют функцию подлежащего или дополнения. Местоимение what в этой роли не употребляется.

2) Соединительные (союзные) местоимения (Conjunctive -соединительный pronouns) вводят придаточные предложения подлежащие, сказуемые (предикативные) и дополнительные.

В составе вводимого ими придаточного предложения они могут выполнять функцию подлежащего, части составного сказуемого или дополнения.

who- который, кто

Употребляется только по отношению к лицам и выполняет в придаточном предложении функцию подлежащего:

1) Относительное местоимение (определение):

I see a boy who is drawing.-Я вижу мальчика, который рисует.

The girl who gave me the book has gone.-Девочка, которая дала мне книгу, ушла.

There was somebody who wanted you.-Здесь был кто-то, кто искал тебя.

2) Соединительное местоимение; примеры придаточного -подлежащего:

Who has done it is unknown.-Кто это сделал, неизвестно.

Придаточного -дополнения:

I know (don’t know) who did it.-Я знаю (не знаю), кто сделал это.

whom-которого

1) Относительное (определение). Также употребляется только в отношении лиц и выполняет в придаточном предложении функцию прямого дополнения:

There is the man whom we saw in the park yesterday.-Вот тот человек, которого мы вчера видели в парке.

She is (She’s) the only person (whom) I trust.-Она – единственный человек, которому я доверяю .

Форма объектного падежа whom считается очень книжной и редко употребляется в устной речи; вместо нее используется who или that, а еще чаще относительное местоимение вообще опускается:

He was talking to a man (whom, who, that) I have never seen before.-Он разговаривал с человеком, которого я никогда раньше не видел.

2) Соединительное; придаточное – сказуемого и придаточное – дополнение:

The question is whom we must complain to.-Вопрос в том, кому мы должны жаловаться.

Tell us whom you saw there.-Скажите нам, кого вы видели там.

whose -который, которого

Употребляется по отношению к лицам (редко к предметам); местоимение whose не опускается.

1) Относительное (определение):

That’s the man whose car is been stolen.-Вот тот человек, машину которого украли.

Do you know the man whose house we saw yesterday?-Знаете ли вы человека, дом которого мы видели вчера?

2 ) Соединительное (в косвенных вопросах и придаточных предложениях):

Do you know whose book it is?-Ты знаешь, чья это книга?

I wonder whose house that is.-Интересно, чей дом это.

which- который, которого; что

Употребляется по отношению к неодушевленным предметам и животным.

1) Относительное (определение). Местоимение which считается книжным и в разговорном стиле обычно заменяется местоимением that:

The pen which (that) you took is mine.-Ручка, которую ты взял, – моя.

В придаточном предложении which может выполнять функцию подлежащего или прямого дополнения. В функции дополнения в разговорной речи оно (как и that) часто совсем опускается:

He returned the book (which,that) he had borrowed.-Он вернул книгу, которую брал.

This is the picture (which, that) I bought yesterday.-Это картина, которую я купил вчера.

В функции подлежащего в придаточном предложении which опускаться не может (но может заменяться that):

He ordered coffee which (that) was promptly brought.-Он заказал кофе, который сразу же и принесли.

I’m looking for jeans, which (that) are less expensive.-Я ищу джинсы, которые были бы дешевле (менее дорогие).

2) Соединительное; пример придаточного – части сказуемого:

The question is which book is yours.-Вопрос в том которая (какая) книга твоя.

Придаточного – дополнения:

I don’t know which book to choose.-Я не знаю, какую книгу выбрать.

Tell me, which way we’ll do it.-Скажи мне, каким образом (способом) мы будем делать это.

what -то, что; что

1) Как относительное (определение) употребляется только в просторечии.

2) Соединительное. Может вводить придаточное предложение–подлежащее:

What I say is true.-То, что я говорю, правда.

Придаточное предложение-сказуемое (предикативное):

That is (That’s) what I don’t understand.-Это – то, что я не понимаю.

Или придаточное предложение-дополнение:

I know what you mean.-Я знаю, что вы имеете в виду.

Don’t forget what I told you.-Не забудь то, что я сказал тебе.

I don’t understand what the difference is.-Не понимаю, какая здесь разница.

Местоимение what в сочетании с наречием ever всегда; когда-либо образует местоимение whatever

Правила использования WHO, WHICH, WHOSE,THAT

Итак, какие такие местоимения называются относительными? Это такие местоимения, которые вводят определительные придаточные предложения и на русский обычно переводятся словами который, -ая, -ое, -ые.

Они всегда относятся к конкретному, определяемому слову (обычно существительному, местоимению в функции дополнения) в главном предложении.

В эту группу входят, среди прочих, и who (который, кто), which (который, которого, что), whose (который, которого, чей) и that (который, которого, что).

Местоимение WHO

Рассмотрим каждое из этих местоимений более подробно.

Особенность местоимения who (который, которого) – это то, что оно употребляется только по отношению к лицам и выполняет в придаточном предложении функцию подлежащего:

E.g. I see a boy who is drawing.

Я вижу мальчика, который рисует. (Рис. 3)

The girl who gave me the book has gone.

Девочка, которая дала мне книгу, ушла.

There was somebody who wanted you.

Здесь был кто-то, кто искал тебя.

I know (don’t know) who did it.

Я знаю (не знаю), кто сделал это.

Рис. 1. Иллюстрация к примеру

Местоимение WHOSE

Очень похоже внешне на who местоимение whose (который, которого, чей). Употребляется это местоимение по отношению к лицам.

E.g. That’s the man whose car has been stolen.

Вот тот человек, машину которого украли.

Do you know the man whose house we saw yesterday?

Знаете ли вы человека, дом которого мы видели вчера?

Do you know whose book it is?

Ты знаешь, чья это книга?

I wonder whose house that is.

Интересно, чей это дом. (Рис. 4)

Рис. 2. Иллюстрация к примеру

Местоимение WHICH

Теперь мы рассмотрим местоимение which (который, которого, что). В отличие от предыдущих местоимений, which употребляется по отношению к неодушевленным предметам и животным. К тому же, оно считается книжным и в разговорном стиле обычно заменяется местоимением that.

E.g. He ordered coffee which (that) was promptly brought.

Он заказал кофе, который сразу же и принесли. (Рис. 5)

I’m looking for jeans, which (that) are less expensive.

Я ищу джинсы, которые были бы дешевле (менее дорогие).

Рис. 3. Иллюстрация к примеру

I don’t know which book to choose.

Я не знаю, какую книгу выбрать.

Tell me, which way we’ll do it.

Скажи мне, каким образом (способом) мы будем делать это.

Иногда в разговорной речи which (that) может опускаться.

The pen which (that) you took is mine.

Ручка, которую ты взял, — моя.

He returned the book (which, that) he had borrowed.

Он вернул книгу, которую брал.

This is the picture (which, that) I bought yesterday.

Это картина, которую я купил вчера.

Местоимение THAT

И напоследок у нас остается местоимение that (который, которого). В роли определения местоимение that часто заменяет местоимения who и which в обычной разговорной речи. Может употребляться по отношению к лицам, но чаще употребляется по отношению к неодушевленным предметам:

E.g. They could not find anybody that (who) knew the town.

Они не могли найти никого, кто бы знал город.

Did you see the letter that had come today?

Вы видели письмо, которое пришло сегодня? (Рис. 6)

The news that (which) he brought upset us all.

Известие, которое он принес, огорчило нас всех.

Рис. 4. Иллюстрация к примеру

В разговорной речи местоимения that (как и which), вводящие определительные придаточные предложения, обычно вообще опускаются:

E.g. It is the end of the letter (that, which) she sent me.

Это конец письма, которое она мне прислала.

The woman (that) I love most of all is my mother.

Женщина, которую я люблю больше всего, – моя мать.

Дополнение в английском языке

Как и в русском, в английском языке дополнения бывают прямые (всегда без предлога) и косвенные (беспредложные и с предлогом – предложные).

Переходные глаголы (которые выражают действие, которое переходит на лицо или предмет) требуют после себя прямого дополнения, обозначающего лицо или предмет и отвечающего на вопрос что? или кого?

Например, He gave a book.

Он дал книгу. (Рис. 5)

Рис. 5. Иллюстрация к примеру

Само прямое дополнение употребляется без предлога, но многие глаголы образуют устойчивые сочетания с предлогами, выражающие единое понятие (например: look for – искать, listen to – слушать, take off – снимать, pick up – поднимать и т. д.). В этом случае предлог (наречие) образует единое целое с глаголом, а следующее за ним прямое дополнение является (как и положено) беспредложным.

Например, I am looking for the book.

Я ищу книгу.

Что же касается косвенных дополнений, то они дают различную дополнительную информацию, отвечающую на разные вопросы: кому?, с кем?, для кого?, о чем? и т. д.

Беспредложное косвенное дополнение возникает в предложении, когда некоторые из переходных глаголов, кроме прямого дополнения, имеют еще и второе – косвенное дополнение, отвечающее на вопрос кому? и обозначающее лицо, к которому обращено действие. Косвенное дополнение, стоящее перед прямым, употребляется без предлога.

Например, He gave the boy abook.

Он дал мальчику книгу. (Рис. 6)

Рис. 6. Иллюстрация к примеру

Предложное косвенное дополнение – это косвенное дополнение, стоящее после прямого. Оно употребляется с предлогом и отвечает на различные вопросы: о ком?, о чем?, с кем?, с чем?, для кого? и т. д.

Например, He gave a book for my father.

Он дал книгу для моего отца.

END или FINISH

Слова end и finish имеют достаточно схожее значение, однако существует ряд различий. Рассмотрим их.

Когда речь идет о приближении к завершению какого-нибудь действия, используется конструкция finish + дополнение («завершать что-то»).

E.g. You should try to finish all the work before 6 p.m.

Тебе следует постараться завершить всю работу до 6 часов вечера.

I have already finished reading that book.

Я уже закончил чтение той книги.

Если же мы используем конструкцию «end + дополнение», получится смысл «останавливать, прекращать что-то». Смысл будет схож с глаголом “to stop”:

E.g. We must end this war!

Мы должны остановить эту войну!

They decided to end their relationships.

Они решили прекратить свои взаимоотношения. (Рис. 7)

Рис. 7. Иллюстрация к примеру

Когда речь идет о «физическом/материальном» завершении чего-то (а не о временнОм завершении), лучше использовать “end”:

E.g. This street ends a mile away from here.

Эта улица заканчивается в одной миле отсюда.

Во всех остальных случаях, как правило, разницы между этими словами либо нет, либо она не существенна. К примеру:

What time do your classes end/finish?

Во сколько заканчиваются твои занятия?

The contract ends/finishes on 15 Oct 2013.

Договор заканчивается 15 октября 2013 года.

После существительных, определяемых прилагательными в превосходной степени, порядковыми числительными, а также all, onlyупотребляется только местоимение that (а не which):

E.g. This is the second book that I read last summer.

Это вторая книга, которую я прочла прошлым летом. (Рис.

I’ve read all the books that you gave me.

Я прочел все книги, которые вы мне дали.

This is the best dictionary that I have ever seen.

Это лучший словарь, который я когда-либо видел.

The only thing that I can do is to take his advice.

Единственное, что я могу сделать, – это послушаться его совета.

Рис. 8. Иллюстрация к примеру

Лимерики

Английские лимерики (english limericks) – это стихотворения, которые являются одной из составляющих английского юмора и культуры.

Лимерик – это короткое смешное стихотворение, состоящее из пяти строк. Кроме того, отличительной чертой лимерика является его особая одинаковая стихотворная форма. Обычно начинается со слов «There was a…».

Вот несколько интересных лимериков.

There was an Old Man of Peru,

Who dreamt he was eating his shoe.

He awoke in the night

In a terrible fright

And found it was perfectly true!

Однажды увидел чудак

Во сне, что он ест свой башмак

Он вмиг пробудился

И убедился,

Что это действительно так.

There was an Old Man, who when little,

Fell casually into a kettle;

But growing too stout,

He could never get out,

So he passed all his life in that kettle.

Один неуклюжий малец

Упал в котелок, сорванец.

Он выбраться быстро хотел,

Но так растолстел,

Что там и остался малец.

Задания для самопроверки

And now let’s do some exercises to understand the use of who, which, whose and that better.

А теперь сделаем несколько упражнений, чтобы лучше понять использования местоимений who, which, whose, that.

Look at the sentences and fill the gaps with the necessary relative pronoun – who, whose, which.

1. Do you know ___ cup of tea it is? → whose

2. She is looking at the aquarium ___ we bought last week. → which

3. I don’t know the girl ___ is speaking with my brother. → who

4. Where is the pie ___ our mother made yesterday? → which

5. Do you know ___ dog is in our garden? → whose

6. We know ___ broke your vase. → who

7. I don’t see the boy ___ won the competition. → who

8. Have you found the dog ___ bit you? → which

9. I wonder ___ car it is. → whose

10. The apple ___ I bought is worm-eaten. → which

Вопросы к конспектам

Вставьте местоимения who, whose или which.

1. He didn’t know ___ sheet of paper it was. 2. We are talking about the book ___ we bought yesterday. 3. I don’t know the man ___ is looking at me. 4. Where is the pizza ___ she cooked yesterday? 5.

Do you know ___ cat it is? 6. I know ___ broke your smartphone. 7. We are discussing the boy ___ won the competition. 8. Do you see the elephant ___ has a big red bow? 9. He wonders ___ house it is. 10.

The apple-pie ___ I bought is in the fridge.

Разделите в две колонки местоимения who, which, whose, that в зависимости от того, употребляются они с одушевленными и неодушевленными предметами. Придумайте по одному примеру, подтверждающему Ваш выбор.

English lives here

Но только для создания специальных вопросов понадобятся вопросительные местоимения (what, who, whom, whose, which, when, why, how):

- what — что, какой, какая, какое, какие,

- who — кто,

Употреблять what или who зависит от информации, которую запрашивают, используя одно из этих местоимений, если необходимо выяснить род деятельности человека, прибегают к what, если имя и / фамилию, то — who:

What is he? Кто он (по-профессии, роду деятельности)?

Who is he? Кто он (как его зовут, его имя и фамилия)?

Who — вопросительное местоимение в именительном падеже (является подлежащим в предложении), в объектном падеже оно же — whom (в предложении — дополнение).

В качестве дополнения в английском предложении могут быть использованы, как whom, так и who. При этом разница между who и whom заключается в том, что whom является более формальным и не используется в разговорной речи, где его заменяет who. Использование whom вместе с предлогом, делает высказывание еще более формальным:

Who said it? Кто это сказал? — именительный падеж (who здесь в качестве подлежащего)

Who did he visit? — Кого он навещал? — объектный падеж, менее формально

To whom did you give your gloves? Кому ты дала свои перчатки? — объектный падеж, очень формально

Whom did you give your gloves to? — объектный падеж, формально.

Реклама

Whose goose is this? Чей это гусь? — притяжательный падеж

Следует отметить, что местоимения who, whom, whose используются только по отношению к одушевленным предметам.

Which article is yours? — Которая статья твоя?

Разница между what и which состоит в следующем:

с what (какой) задают вопрос для уточнения ‘какой из возможных, из себе подобных?’ (Какой = what цвет твой любимый? (один из существующих цветов)),

с which (который) составляют вопрос для уточнения ‘который из определенного, ограниченного круга предметов’ (платье какого = which цвета вы выбираете (из представленных перед нами расцветок платьев, например: розового, голубого и желтого))

What is the smartest computer? Какой самый умный компьютер (из всех существующих компьютеров)?

Which is your bag? Которая из (каких-то определенных) сумок твоя?

Местоимения who, whose, which и what в предложении могут выполнять роль как дополнения, так и подлежащего, при этом в случаях, где местоимения в роли подлежащего, вспомогательный глагол не используют:

What happened next? NOT What did happen next? Что произошло потом? — what подлежащее.

What did you do yesterday? Что ты делала вчера? Did — вспомогательный глагол, what — дополнение.

When did you stay there? — Когда ты там останавливалась?

Why did you visit Peter? — Почему ты навещала Питера?

How is your kitten getting on? — Как поживает твой котенок?

- how many / much — сколько

Разница между how many и how much кроется в том, относится вопрос к исчисляемому или неисчисляемому существительному.

How many books do you have at home? — Сколько книг у тебя дома? (Книга исчисляемое существительное, то есть их (книги) можно посчитать)

How much send is in the vase? Сколько песка в вазе? (Песок — существительное неисчисляемое, его невозможно посчитать по-крупинкам, не прибегая к мерам объема или веса).

Большинство из разобранных нами выше местоимений могут употребляться в сложных предложениях, а именно придаточных, и, служа для связи двух предложений в составе сложного, они приобретают название относительных (who, whom, whose, which, that).

Употребление этих местоимений обычно не вызывает затруднений, за исключением некоторых случаев.

Между which и who разница заключается в том, что which используется в отношении неодушевленных предметов и животных, а who (так же как и whom и whose) — одушевленных. That используется как с одушевлениями, так с неодушевленными.

Разница между who и whom идентична описанному выше правилу: whom — более формально, who — менее.

There was only one woman to whom he spoke. Была только одна женщина, с которой он разговаривал. — более формально

There was only one woman who he spoke to. — менее формально.

I have visited a lot of places which / that are worth seeing. Я посетила много мест, которые стоит увидеть. Places — неодушевленное существительное.

I have seen my aunt who / that is a kind old lady. Я виделась с тетушкой, она милая старушка. Aunt — одушевление существительное.

Which также используется в придаточном предложении, где местоимение относится ко всему предложению.

She seemed more nervous, which was because it was her first day at a new job. Она явно нервничала, потому что это был ее первый день на новой работе.

Разница между that и which менее существенна, а в некоторых случаях эти местоимения взаимозаменяемы.

Для начала разграничим два типа придаточных предложений: определительное и неопределительное.

- Определительное придаточное предложение — это предложение, которое служит для идентификации существительного. В этих предложениях можно использовать как which, так и that (однако that является более неформальным, разговорным), придаточные запятыми не обособляются.

The dresses which you see on the bed cost me 200 Euro. Платья, которые ты видишь на кровати стоили мне 200 евро.

The dress that Peter bought for me is very nice. Платье, которое Питер купил мне, очень милое.

В приведенных примерах придаточные предложения нельзя опустить, предложения в целом потеряют смысл, — так можно идентифицировать определительное предложение.

- Неопределительное предложение — придаточное предложение, которое несет необязательные, дополнительные сведения. В этих случаях придаточное выделяется запятыми, и в нем следует использовать which, а употребление that будет неправильным.

«Science», which is the leading scientific magazine, was chosen for the publication of her article. «Наука», ведущий научный журнал, был выбран для публикации ее статьи.

Придаточное предложение лишь предоставляет дополнительную информацию о предмете, которая, в большинстве случаев, является общеизвестной и необязательной, предложение без нее не потеряет смысл. О вариативности придаточного предложения сигнализирует также выделение его запятыми.

Who может использоваться как в определительных, так и неопределительных предложениях, правила обособления запятыми аналогичны с местоимениям that и which.

They are the people who borrowed our TV-set. Это люди, взявшие у нас на время телевизор. — определительное предложение.

Ann, who is a friend of mine, lent me the book. Анна, моя подруга, одолжила мне эт книгу. — неопределительное.

Полезную информацию о других типах местоимений можете прочитать здесь (неопределенные местоимения some, any, no и их производные)

Если остались вопросы после прочтения статьи, задавайте их в комментариях.

Чтобы не пропустить следующую статью, подписывайтесь на мой блог (кнопка вверху страницы)

Подписывайтесь также на мой мини-блог в твиттере! (Там есть много всего, чего нет здесь)

Если статья была полезна, поделитесь в любой соцсети.

Правила и примеры использования относительных местоимений в английском языке

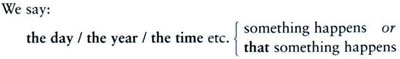

[ Предварительное примечание.

В русском языке мы привыкли, что перед словом «который» всегда ставится запятая. А в английском языке она в основном не ставится. Всё зависит от существенности информации, идущей после слова «который»: можно или нельзя её выбросить без потери смысла предложения?

В предложении «The house that Jack built is large — Дом, который построил Джек, большой» придаточное «который построил Джек» выбросить нельзя, так как останется «Дом большой» — то есть произошла утрата существенной информации. Можно даже сказать, что произошла утрата части «многословного» подлежащего Дом-который-построил-Джек. В таких предложениях перед «который» в английском языке запятая не ставится.

А вот в предложении «My father, who is 78, swims every day — Мой отец, которому 78 лет, плавает каждый день» придаточное предложение «которому 78 лет» можно выбросить: получится «Мой отец плавает каждый день» — то есть смысл сохранился, мы лишь удалили несущественное «замечание в скобках». Такие придаточные предложениях англичане и американцы выделяют запятыми.

Чтобы грамматически наукообразить сказанное, в английской грамматике различают два вида Relative Clauses (определительных придаточных предложений) — Restrictive и Nonrestrictive. В русском языке такого нет.

Restrictive Clause — определительное индивидуализирующее придаточное предложение, оно определяет, передает индивидуальный признак лица или предмета (лиц или предметов), то есть признак, приписываемый только данному лицу или предмету и отличающий его от всех других лиц или предметов того же класса.

Пример: The house that Jack built is large.

Nonrestrictive Clause — определительное описательное придаточное предложение, служит для сообщения о лицах или предметах дополнительных сведений (а не говорит нам, о каком лице или предмете идет речь). Таким образом описательные определительные придаточные предложения не несут существенной информации и могут быть без ущерба для смысла выброшены из предложения

Пример: My father, who is 78, swims every day.

Если вся эта терминология покажется вам утомительной, запомните простое правило пунктуации: «перед словом that запятая никогда не ставится» и считайте, что усвоили статью на 60%. ]

Самыми распространёнными относительными местоимениями (relative pronouns) в английском языке являются who/whom, whoever/whomever, whose, that и which. (Заметим, что в некоторых ситуациях what, when, where тоже могут выступать как относительные местоимения.)

В сложных предложениях с относительных местоимений начинаются определительные придаточные предложения (relative clauses), которые индивидуализируют или поясняют отдельное слово, выражение или идею главного предложения. Поясняемое слово (выражение) называется антецедентом (= предшествующее). В следующих примерах that и whom поясняют подлежащее главного предложения:

The house that Jack built is large.

Дом, который построил Джек, большой.

The professor, whom I respect, recently received tenure.

Профессор, которого я уважаю, недавно получил постоянную должность (на кафедре).

Какое относительное местоимение следует использовать, зависит от типа определительного придаточного предложения.

В целом существуют два типа определительных придаточных предложений: индивидуализирующее (restrictive (defining) clause — ограничительное, оно суживает определение поясняемого слова) и описательное (non-restrictive (non-defining) clause — неограничительное, не суживает определения). В обоих этих типах относительное местоимение может выступать как подлежащее, дополнение или притяжательное местоимение («whose»).

Относительные местоимения в индивидуализирующих определительных придаточных предложениях (Relative Pronouns in Restrictive Relative Clauses)

Относительные местоимения, стоящие в начале индивидуализирующих определительных придаточных предложений, не отделяются запятой.

Индивидуализирующие придаточные предложения (restrictive relative clauses, иначе называемые «дающие определение слову» — defining relative clauses) добавляют существенную информацию об определяемом слове.

Без этой информации невозможно правильно понять смысл предложения — поэтому такие придаточные не могут быть выброшены из сложноподчинённого предложения без потери смысла.

Таблица ниже показывает, какие относительные местоимения следует использовать в индивидуализирующих определительных придаточных предложениях после разных антецедентов (= поясняемых ими слов):

| Function in the sentence Член предложения |

Reference to | На что указывает | ||||

| People Люди |

Things/concepts Вещи/понятия |

Place Место |

Time Время |

Explanation Объяснение |

|

| Subject Подлежащее |

who, that | which, that | |||

| Object Дополнение |

(that, who, whom)* | (which, that)* | where | when | what/why |

| PossessiveПритяжательное

местоимение |

whose | whose, of which |

Примеры

Относительное местоимение является подлежащим в индивидуализирующем придаточном предложении (поэтому запятой не отделяются!) (Relative pronouns used as a subject of a restrictive relative clause):

This is the house that had a great Christmas decoration.

Вот дом, который красочно наряжали на Рождество.

It took me a while to get used to people who eat popcorn during the movie.

Я не сразу привык к людям, которые едят попкорн во время сеансов в кинотеатре.

Относительное местоимение является дополнением в индивидуализирующем придаточном предложении (Relative pronouns used as an object in a restrictive relative clause):

1) Как видно из таблицы, если речь идёт о человеке или предмете, относительное местоимение, выступающее в роли дополнения, можно опустить (отмечено *). Но в неразговорном (официальном) языке его не опускают.

Когда относительное местоимение употребляется с предлогом, то вместо that используют which, например, «in which», «for which», «about which», «through which» и так далее (см.

последний пример).

Formal English: This is the man to whom I wanted to speak and whose name I had forgotten.

Официальный язык: Этот тот человек, с которым я хотел поговорить и имя которого забыл.

Informal English: This is the man I wanted to speak to and whose name I’d forgotten.

Разговорный язык: Это человек, с которым я хотел поговорить и имя которого забыл.

Formal English: The library did not have the book that I wanted.

Официальный язык: В библиотеке не оказалось книги, которая (была) мне нужна.

Informal English: The library didn’t have the book I wanted.

Разговорный язык: В библиотеке не оказалось нужной мне книги.

Formal English: This is the house where/in which I lived when I first came to the United States.

Официальный язык: Вот дом, где/в котором я жил, когда впервые приехал в США.

Informal English: This is the house I lived in when I first came to the United States.

Разговорный язык: В этом доме я жил, когда только что приехал в США.

2) В американском английском (American English) слово whom (кого) используется редко. «Whom» звучит более официально, чем «who», и очень часто в речи опускается совсем:

Grammatically Correct: The woman to whom you have just spoken is my teacher.

Грамматически правильно: Женщина, с которой ты только что говорил, — моя учительница

Conversational Use: The woman you have just spoken to is my teacher.

OR ИЛИThe woman who you have just spoken to is my teacher.

Разговорный язык: Женщина, с которой ты только что говорил, — моя учительница.

Однако «whom» нельзя опускать, если перед ним стоит предлог, так как относительное местоимение «whom» поясняет именно этот предлог (является в предложении дополнением к нему):

The visitor for whom you were waiting has arrived.

Посетитель, которого вы ожидали, прибыл.

Относительные местоимения для притяжательного падежа в индивидуализирующем придаточном предложении (Relative pronouns used as a possessive in a restrictive relative clause):

Whose — единственное относительное притяжательное местоимение (possessive relative pronoun) в английском языке. Оно может относиться как к людям, так и вещам:

The family whose house burnt in the fire was immediately given a complimentary suite in a hotel.

Семье, чей дом сгорел, немедленно предоставили (для проживания) номер в гостинице.

The book whose author won a Pulitzer has become a bestseller.

Книга, автор которой (= чей автор) получил Пулитцеровскую премию, стала бестселлером.

Относительное местоимения в описательных придаточных предложениях (Relative Pronouns in Non-Restrictive Relative Clauses)

Несмотря на сходство с индивидуализирующими придаточными предложениями, описательные придаточные предложения (в большинстве случаев) отделяются запятой от главного предложения. В качестве показателя описательного характера придаточного предложения предпочтительно использовать местоимение which (который).

Описательные придаточные предложения (non-restrictive relative clauses, также известные как non-defining relative clauses — не несущие функции индивидуализации, конкретизации смысла) дают об определяемом слове из главного предложения лишь дополнительную, несущественную информацию.

Эта информация необязательна для правильного понимания смысла всего предложения и потому может быть из него выброшена без ущерба для смысла.

Примеры

Относительные местоимения в роли подлежащего в описательном придаточном предложении (Relative pronouns used as a subject of a non-restrictive relative clause):

The science fair, which lasted all day, ended with an awards ceremony.

Ярмарка научных проектов студентов, которая продолжалась весь день, закончилась церемонией вручения наград.

The movie turned out to be a blockbuster hit, which came as a surprise to critics.

Этот фильм оказался блокбастером (хитом продаж), что стало сюрпризом для критиков.

Относительные местоимения в роли дополнения в описательном придаточном предложении (Relative pronouns used as an object in a non-restrictive relative clause):

The sculpture, which he admired, was moved into the basement of the museum to make room for a new exhibit.

Скульптуру, которую он очень любил, перенесли в подвал музея, чтобы освободить место для нового экспоната.

The theater, in which the play debuted, housed 300 people.

Театр, в котором эта пьеса была впервые поставлена, вмещает 300 зрителей.

Когда использовать относительное местоимение «that», а когда «who» и «which» («That» vs. «Who» and «Which»)

Относительное местоимение that может использоваться только в индивидуализирующих придаточных предложениях.

В разговорном английском, если речь идёт о людях, его можно заменить на who, а если о вещах — то на which.

Хотя that часто используется в разговорном языке, в официальном письменном языке всё же привычнее выглядят who и which.

Conversational, Informal: William Kellogg was the man that lived in the late 19th century and had some weird ideas about raising children.

Разговорный язык: Уильям Келлог — это человек, живший в конце 19-го века и имевший очень странные идеи о воспитании детей.

Written, Formal: William Kellogg was the man who lived in the late 19th century and had some weird ideas about raising children.

Письменный, официальный язык: Уильям Келлог — это человек, который (кто) жил в конце 19-го века и имел очень странные идеи о воспитании детей.

Conversational, Informal: The café that sells the best coffee in town has recently been closed.

Разговорный язык: Кафе, в котором продавался лучший в городе кофе, недавно закрылось.

Written, Formal: The café, which sells the best coffee in town, has recently been closed.

Письменный, официальный язык: Кафе, в котором продавался лучший в городе кофе, недавно закрылось.

Особые случаи использования относительных местоимений в индивидуализирующих придаточных предложениях (Some Special Uses of Relative Pronouns in Restrictive Clauses)

that / who

В разговорном языке по отношению к людям можно использовать как that, так и who. «That» может быть использован для обозначения характеристик или способностей индивида или группы людей:

He is the kind of person that/who will never let you down.

Он такой человек, который (кто) никогда вас не подведёт.

I am looking for someone that/who could give me a ride to Chicago.

Я ищу человека, который (кто) мог бы довезти меня до Чикаго.

Однако в официальном языке по отношению к конкретному человеку предпочтительнее использовать who:

The old lady who lives next door is a teacher.

Старушка, которая живёт рядом, — учительница.

The girl who wore a red dress attracted everybody’s attention at the party.

Девушка, на которой было красное платье, привлекла всеобщее внимание на вечеринке.

that / which

В некоторых случаях that подходит больше, чем which:

1) После местоимений «all», «any(thing)», «every(thing)», «few», «little», «many», «much», «no(thing)», «none», «some(thing)»:

The police usually ask for every detail that helps identify the missing person.

Обычно полицейские выспрашивают про каждую подробность, которая может помочь в розыске пропавшего человека.

Dessert is all that he wants.

Она не хочет есть ничего, кроме сладкого (десерта).

2) После существительного, перед которым стоит прилагательное в превосходной степени (superlative degree):

This is the best resource that I have ever read!

Это самый лучший ресурс, который мне доводилось читать!

Специальные вопросы в английском языке, как и в русском, задаются с целью выяснить какую-то конкретную информацию о предмете или явлении. Отличительной чертой специальных вопросов в английском является обязательное наличие вопросительных слов.

Такие вопросы в английском языке задается к любому члену предложения. Все зависит от того, что именно нужно узнать человеку.

Примеры

What do you need for a good mood? — Что тебе нужно для хорошего настроения?

What is the main question? — Каков основной вопрос?

When will you be here? — Когда ты будешь здесь?

Вопросительные слова:

What? — Что?

Where? — Где?

When? — Когда?

Why? — Почему?

Who? — Кто?

Which? — Который?

Whose? — Чей?

Whom? — Кого?

How? — Как?

Вопросительные слова what (что), where (где), when (когда) используются чаще всего.

Вопросительные слова в английском начинаются с сочетания букв wh. По этой причине специальные вопросы также называют «Wh-questions».

Кроме того, в английском языке есть и вопросительные конструкции, состоящие из двух слов:

What kind? — Какой?

What time? — Во сколько?

How many? — Сколько? (для исчисляемых существительных)

How much? — Сколько? (для неисчисляемых существительных)

How long? — Как долго?

How often? — Как часто?

How far? — Как далеко?

Важно помнить, что вопросительное и уточняющее слова в вопросе не разделяются. Вся конструкция ставится в начало предложения.

Примеры

How far will she go? — Как далеко она зайдет?

How long will it take? — Сколько времени это займет?

Выбирая вопросительную конструкцию, автор вопроса определяет, какая именно информация его интересует. Например, к предложению

Maria bakes bread once a week. — Мария печет хлеб раз в неделю.

можно задать несколько вопросов:

Who bakes bread once a week? — Кто печет хлеб раз в неделю?

How often does Maria bake bread? — Как часто Мария печет хлеб?

What does Maria bake once a week? — Что Мария печет раз в неделю?

Как задать специальный вопрос

При формировании специального вопроса за основу берется общий. Например, общий вопрос к предложению

She saw this film. — Она смотрела этот фильм

будет звучать как

Did she see this film? — Она смотрела этот фильм?

Для того чтобы преобразовать его в специальный, необходимо добавить в начало предложения одно из вопросительных слов.

Пример

When did she see this film? — Когда она смотрела этот фильм?

Вспомогательный глагол, как и в общем вопросе, ставится перед существительным, смысловой — после него.

Общая схема построения специального вопроса в английском:

Вопросительное слово + вспомогательный глагол + подлежащее + сказуемое + остальные члены предложения

Примеры

What have you done? — Что ты наделал?

Why has he eaten this? — Почему он съел это?

What are you doing? — Что ты делаешь?

Правила формирования специального вопроса

- Первое место в порядке слов принадлежит вопросительному слову.

- Второе место занимают модальные (should, ought, may, must, can и другие) или вспомогательные (do/does,have/has, to be и другие) глаголы.

Схемы построения видов специальных вопросов в английском языке

- С вспомогательными глаголами (do/does, will, did и т.д.)