Reading wars, Whole word VS. Phonics, whole language advocates vs. phonetics enthusiasts…

Who would imagine that learning to read could be such a controversial topic?

But sadly, it is!

And I use the word SADLY for a good reason: Because the ones that normally pay the consequences of this disagreement are our children!

In this article we will look at the differences between the whole word approach and the phonics approach, so you can learn the ins and outs of this hot debate and form your own opinion.

If your child is learning to read, this is a crucial topic for you to understand as a parent. The reading success of your child can depend very much upon the actual approach used to teach your child to read; and, as you will discover on this article, schools do not always use the most effective method.

When it comes to teaching children to read there are two main teaching methods.

These two main methods are the whole word approach (also called the “sight words” approach) and the phonetic or phonics approach.

Some prefer the whole word method, while others use the phonics approach.

There are also educators that use a mix of different approaches.

But, who is right?

The Whole Word Approach

The whole word approach relies on what are called “sight words”. This method basically consists of getting children to memorize lists of words and teaching them various strategies of figuring out the text from a series of clues. Using the whole word approach, English is being taught as an ideographic language, such as Chinese or Japanese.

One of the biggest arguments of whole word advocates is that teaching to read using phonics breaks up the words into letters and syllables which have no actual meaning. Yet they fail to acknowledge that once the child is able to decode the word, they will be able to actually read that entire word, pronounce it and understand its meaning. So, in practicality, this is a very weak argument, from our point of view.

Unlike Chinese, English is an alphabet-based language. This means the letters of the English alphabet are not ideograms (also called ideographs), like Chinese characters are.

An ideogram (or ideograph) is a graphic symbol that represents an idea or a concept. Simply put, ideograms are like logos.

So, in a way, you could say that in the Chinese language you need to teach children to memorize “logos” and the meaning of each of them.

It is not logic to think that English should be taught using an ideographic approach…

So, the very popular reading programs that use a whole word approach simply get children to memorize words using different strategies, but without teaching any proper decoding methodology.

Think of the example we used before of the logos and the Chinese language.

Besides, there is no scientific evidence to suggest that teaching your child to using the whole word approach is an effective method. However, there are large numbers of studies which have consistently stated that teaching children to read using phonics and phonemic awareness is a highly effective method.

The Whole-Word Approach in Schools…

So, is your child learning to read using sight words? Or maybe a mixture of phonetics and sight words? What is the standard approach in our education system?

Well, every country – and even every educator / school – is different.

However, in English speaking countries in general -with the exception of the UK, which has been encouraging schools to adopt a systematic synthetic phonics approach since 2011- reading instruction is normally more heavily weighted towards the teaching of sight words, emphasizing the learning of “word shapes”.

Despite all the evidence to suggest otherwise, the whole word method of teaching still dominates how reading is taught at schools.

Why? Well, our guess is that children can appear to make fast progress with the whole language approach, and that makes everybody happy…

That is until their progress stalls, which is what usually happens, because with this method many children do not learn the relationships between letters and sounds correctly.

Some children can finally understand the letter-sound relationships from the words they have learned, but unfortunately many children aren’t able to figure this out. So, they are left with only one strategy for learning to read: memory and continuous repetition.

This is a very poor strategy these children are left with, in our opinion.

On the other hand, the reading ability of children is normally exaggerated on whole word programs as the texts used are very repetitive and extremely predictable. The children know what to expect. So… They are basically guessing!

When children are presented with a less predictable text without pictures, they struggle with words they had previously been able to figure out in a repetitive text with illustrations.

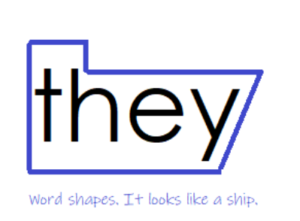

Another strategy used in whole word programs consists of focusing on word shapes.

Just have a look at this image. This is a “reading strategy” used on whole word programs.

Encouraging children to learn to read by looking at word shapes is completely madness! They are told to look at words as if they were “pictures”, focusing on the overhangs in the shapes of words! This does not apply for the English language!! Again, this is a method used for ideographic languages, such us Chinese or Japanese.

It does not make sense! There are just so many words with very similar shapes!

For example, look at this:

- hat vs. bat

- tree vs. free

- fall vs. tall vs hall

- hunt vs. hurt vs. hard

And the list goes on and on and on… Honestly, we could find thousands of words that have similar shape if we had the time to do this exercise!

The Whole- Word Method and Spelling

Even if a child has some early success learning to read using whole words programs, it gets him/her into the habit of ignoring the letters in words. This causes serious reading problems later on (when texts get more complicated), including spelling problems.

Another strategy that we are told to do on whole word programs is encouraging our children to look at the pictures in storybooks to “guess” or “predict” words.

-

Can they use the picture to help?

-

Can they look at the initial letter and predict what word would make sense that starts with that letter?

-

What word makes sense based on the context?

A little bit of history on the Whole-Word Approach

The main idea behind this theory is that if you see words enough number of times, you eventually store them in your memory as visual images.

They also embrace the idea that kids can naturally learn to read if they are exposed a lot of books.

Since the 1980s, these beliefs had strongly influenced the way children in North America and most English speaking countries are taught to read and write.

These ideas start to emerge in the 1970’s, and they become extremely popular for teaching reading in the 80’s and 90’s.

There is a strong focus on meaning, rather than sounds.

The Phonics Approach

At the opposite end of the spectrum, we find reading instruction based on phonemic awareness and phonics.

The phonics approach focuses on the sounds in words, which are represented by the letters (or groups of letters) in the alphabet.

There is a myriad of methods and systems within the phonics approach itself, but the the two main methodologies for teaching phonics are Synthetic and Analytic phonics.

Even though they both have the label “Phonics” attached to them, they are in fact quite different ways for teaching children to read.

However, for the sake of this article (and to keep things simple) we will just say that the main difference is that in the Synthetic Phonics approach skills are taught in a highly structured ‘systematic’ way.

Children start with very simple sounds and decoding regular words. Gradually, they are introduced to more complex sounds (such us letter combination sounds) and to irregularities and exceptions. Every step of the way is planned, and children only move to the next stage of phonics once they have mastered the previous one.

In the Analytic Phonics approach, reading instruction is less structured, and learning happens in a more ‘embedded’ fashion. Children are encouraged to analyze groups of whole words to identify similar sounds and letter patterns. Instruction relies a lot on the analysis of “families of words”.

For instance, the family of words ending up in -all, such us “tall, fall, mall, hall, small”, or the family of words ending up in -at, such “mat, cat, rat, bat, fat, pat”.

If you are interested in knowing more about the differences between analytics and synthetic phonics, you can check this video.ç

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/twDjIsFkhFM” title=”YouTube video player” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>

Is there a Winner in the Reading Wars?

What Research / Modern Science has to say…

The best way to put an end to this controversy and start making decisions that are RIGHT for our kids – and not based on personal preferences or ideology- is by looking at what research and scientific studies have to say.

However, you may think that if opinions on the topic are still so divided, then it must be that the results of these studies are somehow inconclusive.

Well, not really…

Look at these statements by the US National Reading

“Teaching children to manipulate phonemes in words was highly effective under a variety of teaching conditions with a variety of learners across a range of grade and age levels and that teaching phonemic awareness to children significantly improves their reading more than instruction that lacks any attention to Phonemic Awareness.”

“Conventional wisdom has suggested that kindergarten students might not be ready for phonics instruction, this assumption was not supported by the data. The effects of systematic early phonics instruction were significant and substantial in kindergarten and the 1st grade, indicating that systematic phonics programs should be implemented at those age and grade levels.”

^* Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Excerpts from the meta-analysis of over 1,900 scientific studies.

Overwhelmingly research has found that phonemic awareness and phonics is a superior way for teaching children to read!

But wait there is more…

Modern Scientific Research on the Brain and How we learn to read

For a very long time many experts have embraced the idea that we store words in our memory in the same way we store visual memories, such us faces or objects. That belief is at the core of the whole word approach.

And, in fact, many reading experts still believe this is the cse.

However, modern scientific research proves otherwise…

But before I tell you how we actually store words in our memory, look at the following factors already pointing out at how visual memory -contrary to still popular belief – is NOT involved:

-

We can read mixed case letters without difficulties.

-

We can read words with different fonts, in print and cursive, and handwritting without difficulties.

-

Word recognition works faster than object recognition, indicating that we are using different storage and retrieval processes.

Let me tell you about the sound scientific evidence now…

Brain scans show that the parts of the brain activated while performing visual memory tasks are different than the parts of the brain activated while reading…

Moreover, scientists in the visual memory area (not related to reading research, therefore unbiased) have indicated that we don’t have the cognitive capacity to remember 30 – 90,000 words for immediate retrieval.

As reading instruction still assumes that we store words as visual images, students who struggle to remember words are many times presumed to have poor visual memory.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. There is only a small relationship between visual memory and our capacity to store words for immediate retrieval while reading.

However, there is a very strong relationship between HEARING skills and our capacity to store words for immediate retrieval while reading (fluent reading capacity).

To be more specific, children that have been trained to hear the actual sounds that form words (phonemic /phonological skills) and are capable to recognize and store those common strings of sounds and visually link them to the letters / words they know become fluent readers.

There is no evidence to suggest that visual memory has a role in word recognition /reading fluency once the letters and the connection between letters and sounds have been learned.

If there seems to be a winner on the ‘Reading Wars’, why do we keep arguing?

Phonics instruction cons…

These are the main arguments against phonics instruction:

- Children only read phonics books: This is one of the main pillars of a proper phonics system. Children should only attempt to read books that are in line with their level of phonics. Otherwise, it is overwhelming for them and can get confused, since they may be exposed to too many exceptions and irregularities. While this is true, that doesn’t mean that parents can’t read more difficult books to their children. And, in fact, they are encouraged to do so.

- Phonics doesn’t help with reading comprehension. Besides, teaching to read using phonics breaks up the words into letters and syllables, which have no actual meaning. However, once the child is able to decode the word, he/she will be able to actually read that entire word, pronounce it and understand its meaning.

- Children learn to read naturally, therefore they don’t need tedious phonics instruction. Whereas it is truth that some children can learn to read by themselves, most won’t be able to figure it out. Besides, there is no harm in receiving phonics instruction for those that are able to learn to decode by themselves.

- There are just too many exceptions and irregularities in English. While it is true that English is full of irregularities and exceptions, there are less of these than what we are led to believe. Besides, there are some rules, patterns and tips and tricks that apply to those “irregular” words that certainly do help in the process of learning to read.

So, saying that phonics has won the war is quite far from what happens in reality.

As we stated at the beginning of the article, there are different ways for teaching phonics.

What our schools have evolved to do to keep both sides of the war happy is establishing a “balanced literacy” strategy that combines both whole word and phonics principles.

What in practicality ends up happening is that there is only a little bit of phonics instruction here and there, rather than a proper curriculum based on phonics.

That is an ineffective method for teaching phonics, and certainly doesn’t work. And this is precisely the sort of evidence that whole word enthusiasts hold on to.

Final thoughts on the Reading Wars

The debate is still hot. This is bizarre as, in our opinion, based on the latest scientific evidence, the number one skill that we need to develop in our children is phonemic awareness.

This way we would have far fewer students with reading difficulties.

And, after having developed strong phonological / phonemic awareness skills, using a proper phonics approach (and not just a little bit of phonics instruction here and there) seems like the way to go.

Free Resources you may be interested in!

Phonemic Awareness Activity Worksheets

Nursery Rhymes Ebook

44+ English sounds chart

List of CVC Words

При обучении чтению на родном языке давно используют метод целого слова с картинкой с детьми от 2-летнего возраста. У нас в стране это известные педагоги Никитины, например. Карточка с картинкой и словом под ней, листочки с крупно написанным словом, приклееные к соответствующему предмету по всей квартире и т.п. методы и приемы. Как бы две картинки для обозначения одного предмета (один текст на двух языках). Далее игры всякие на подбор элементов (букв) составляющих слово и т.д.

Достаточно часто этот прием срабатывает и с младшими школьниками.

Но, начиная изучать иностранный язык во 2-м классе, дети уже хорошо знают, что такое буквы и зачем они , умеют читать. Буквы иностранного языка для них уже не картинка. И вот я постоянно на практике сталкиваюсь с тем, что после года-двух изучения языка (2-3 классы) в 4-м классе дети совершенно не могут прочитать ни одного нового слова — читают только те, что выучили визуально как картинку. Правильно подставить первую букву в короткие слова, если их озвучивают!. Если 6 человек из одной группы в 12 человек обращаются к репетиторам, потому что неумение читать не позволяет им нормально осваивать учебник, то это уже какие-то методические неправильности. То, что эффективно срабатывает с дошкольниками при обучении чтению на первом (родном) языке, не всегда эффективно для изучения иностранного школьниками со 2-го класса.

Нельзя рассчитывать на прекрасную память, которая позволит «сфотографировать» весь словарь. На то, что умение анализировать и находить какие-то закономерности словообразования само появится. Всему этому надо ребенка обучать, давать ему подсказки и задания, развивающие аналитический подход. Пусть он будет рассматривать слово как набор букву (звуков) в определенном порядке, как пазл, который зазвучит, если правильно сложены все его элементы и т.п. И начинать надо от простого к сложному. На мой взгляд, фонетически сложные и длинные иностранные слова должны приходить после освоения более простых и четких по звукам. В частности поэтому, я считаю неудачными такие УМК, как SPOTLIGHT или Кузовлев для 5 класса (первый год обучения).

Мне приходится учить чтению учеников 3-6 классов, и анализ причин, почему способные дети за 2-5 лет не научились читать даже весьма простые слова — понимают на слух, но не опознают в тексте и не могут их написать, «вспоминают» при наличии картинки 3-5-буквенные слова, а без картинки сразу путаются — позволяет делать вывод, что одной из важнейших причин является отказ от обычного обучения чтению и письму, в т.ч. прописному, а не только печатному. Не надо перегружать количеством, но стоит следовать принципу лучше меньше да лучше в смысле перехода к новому только после прочного усвоения старого.

Many schools are moving away from teaching children to recognise whole words to teaching them how to decode. It is important for anyone reading with children, or teaching them to read to understand why this is so significant.

The approach of teaching kids to recognise whole words is a ‘top down’ approach. It requires children to memorise the word by shape. Remember those ‘Look and Say’ days? Children would be given flash cards with words on them and expected to remember how to read and spell them. This approach has failed many, many children. Why? Because after a while, precious memory gets clogged up. Each word is memorised in isolation with no connection to any other words. The typical result of this failing approach is the ‘Year 4 slump’. Kids seem to be reading OK until Year 4 when suddenly they stop making progress. A sign that they can no longer remember more words and are completely stuck.

The decoding approach is a ‘bottom up’ approach. Kids learn to segment individual sounds in words, how these sounds are represented by letters and how to blend the sounds/letters into words. Because every word can be broken up into spellings (graphemes), the decoding route is like having a versatile box of Lego bricks that you can reassemble every time, reusing bits that you already know. So much more efficient, as it makes links between words with the same spellings and enables kids to teach themselves to read new words. This approach is supported by research. The image above demonstrates how a child would see words in a text in these two different approaches.

If we follow the Alphabetic Principle – that letters spell sounds in words – then should be consistent and teach children to decode all words, even high-frequency words (sight words). To see our graphics on how to decode high-frequency words click here

UK versions

USA versions

#decoding #phonicsreading #phonicsforkids

It has been interesting to read about the evolution of education in America. During the eighteenth century, education moved from the home into schools and textbooks were created to help teachers tutor their students in the basics like reading and math. The McGuffy Readers were among the first of these easy-to-read books that are now called a basal reading series.

At that time, first and second grade books were specifically written to include stories that emphasized the sounds of letters in words. Teaching in the eighteenth century tended to be teacher-centered with students doing a lot of rote memorization.

Around the beginning of the twentieth entury, the Progressive Education Movement introduced instruction that focused more on the interests of students and what research was discovering about teaching and learning.

More and more stories began to emphasize particular sounds and other targeted reading strategies. Sometime in the 1950s a “whole word” approach to teaching reading began to be used – returning students once again to rote memorization.

So what is the problem with this whole word memorization approach? The best answer I can find is this analogy by Steve Waller. Reading music (phonics reading) versus playing by ear (whole word reading).

You can read faster by whole word reading just as you can play music faster by playing by ear.

But you can read more difficult passages by reading phonetically just as you can play more difficult music by reading music.

You can spell better with phonics just as you can write music better if you can read music.

Listed here are some other challenges associated with whole word reading:

Pronouncing Unfamiliar Written Words

If a whole word reader looks up a written word in the dictionary, they can define it but still can’t pronounce the word because the dictionary pronunciation keys have little or no meaning. Dictionaries don’t help whole word readers with pronunciation.

Spelling

Whole word readers are frequently and understandably poor spellers. Without the skills of phonics, what spelling mechanism can be applied to a word not already memorized? How would a whole word reader know that a spelling mistake has been made? It makes sense that a whole word reader must either guess or substitute an alternative word, one with a known spelling.

Phonics does not ensure perfect spelling. More and more English words are adopted from other languages. However, additional reading strategies and skills, like marking can resolve most, if not all, spelling challenges.

Dictionaries

Whole word readers are not inclined to use dictionaries. This tends to limit their vocabulary to written and spoken words they already know, words they were taught when they were learning to read or words that they needed to learn by whatever non-phonetic method the student was forced to utilize in school or work.

Motivation to Read

New and difficult words are a chore to read or hear because the resources that would make pronunciation or comprehension easier are not very helpful for whole word readers. New spoken words cannot even be noted down for later investigation because it cannot be spelled. Whole word readers need spoken words written for them and written words spoken for them.

Research has been conclusive that explicit phonics instruction is the most effective. The U.S. Department of Education, the National Research Council, and the National Reading Panel have all conducted research and have released finding reports that support this statement. The National Reading Panel’s report on its quantitative research studies on areas of reading instruction was published in 2000. The panel reported that several reading skills are critical to becoming good readers: phonics for word identification, fluency, vocabulary, and text comprehension.

This post may contain affiliate links. Affiliate links use cookies to track clicks and qualifying purchases for earnings. Please read my Disclosure Policy, Terms of Service, and Privacy policy for specific details.

Two techniques to teach reading include 1) using phonics to decode words and 2) recognizing whole words by sight. Whole word reading programs have fewer prerequisite skills in comparison to decoding reading programs. CLICK HERE to read an overview of the prerequisite skills for learning to read. This article is a round-up of whole word reading methods and curriculum posts.

First assess a child’s readiness for whole word reading methods.

The prerequisite skills for learning to read using whole word programs include being able to discriminate the differences between the groups of letters that form words.

CLICK HERE to for instructions on evaluating prerequisite visual discrimination skills.

Next select a curriculum or instructional method.

Published Curriculum

Edmark

Edmark is a complete whole word reading program. Word recognition, sentence fluency, and comprehension are all covered in this curriculum.

CLICK HERE to read my complete review of the Edmark Reading Curriculum.

Instructional Methods

Fernald Method

CLICK HERE to read about how to implement this approach. This approach is appropriate for individuals with severe reading disabilities.

Time Delay

Time delay is an instructional procedure that can be used to teach high frequency sight words or other selected whole words. This approach to teaching whole words has been demonstrated as effective in research (Knight, Ross, & Taylor, 2003; Ledford, Gast, Luscre, & Ayres, 2008; Redhair, McCoy, Zucker, Mathur, & Caterina, 2013).

CLICK HERE to read an overview of how to implement time delay. One of the included time delay examples is for math facts. The exact same procedure can be applied to teaching whole words.

Stimulus Fading

CLICK HERE to read about how to use the stimulus fading approach.

Time Delay vs. Stimulus Fading

Both time delay and stimulus fading are research based methods for teaching children to read whole words. The materials for time delay procedures are easy to create. Stimulus fading materials require more sophisticated computer skills, namely knowing how to use a paint app or editing program to 1) superimpose words over an image and 2) fade out the image. Both time delay and stimulus fading are easy to implement once you have your materials ready. The main advantage of a time delay procedure is ease of implementation. One advantage of a stimulus fading procedure is that a child may incidentally learn new words. Redhair, McCoy, Zucker, Mathur, & Caterino (2013) found that children may learn knew words from exposure to the word superimposed over a cooresponding image prior to actually teaching the new word.

Conclusion

Whole word methods are commonly used to teach children to read high frequency sight words. They may also be used to improve overall reading ability and fluency alone, or in combination with a phonics based reading program.

References

Knight, M. G., Ross, D. E., & Taylor, R. L. (2003). Constant time delay and interspersed of known items to teach sight words to students with mental retardation and learning disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 179-191.

Ledford, J. R., Gast, D. L., Luscre, D., & Ayres, K. M. (2008). Observational and incidental learning by children with autism during small group instruction. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 86–103.

Redhair, E. I., McCoy, K. M., Zucker, S. H., Mathur, S. R., & Caterino, L. (2013). Identification of printed nonsense words for an individual with autism: A comparison of constant time delay and stimulus fading. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48, 351-362.

Do you want to know the truth about whole word reading? Yes, the truth. I’m not pulling it out of thin air. It is not just my opinion either.

I have taught reading for nearly 20 years. I have taught and tutored struggling readers. I also have a Masters in Reading and am certified in dyslexia and language-based learning differences. I have a little experience and a bit of training in this area, so hang with me!

I sometimes get emails from readers asking if their struggling reader could be a whole word reader. In other words, they asking, “Does my learner/child just need to memorize whole words instead of learning phonics?”

My answer is always a resounding NO! Here are four common questions I am asked and my responses.

*This post contains affiliate links.

The Truth about Whole Word Reading

Question 1: I learned to read without phonics and I’m an avid reader. Is phonics instruction really needed? Kids can learn to read without it, right?

Answer: If you’re a math person, this is like saying, “It’s faster to just memorize math facts than to teach learner how to get the answer.”

Yes, it might be faster in the short-term, but it’s ineffective in the long-term. Johnny might memorize the fact, but he doesn’t know how to apply it or use it because he doesn’t know the “how.”

I was not taught phonics either, as far as I remember. I was ALWAYS a struggling reader, especially through high school and college. It wasn’t until I started learning and teaching phonics (we’re talking GRAD SCHOOL here) that I began to really pick up on my reading, especially longer words I’d never seen before.

Yes, some kids can “crack the code” of reading without explicit, step-by-step phonics instruction. For them, it just “clicks” around Kindergarten and first grade. Even though they’re not explicitly taught phonics, they’ve figured it out, BUT they still need phonics to figure out unknown words, especially as those words get longer.

Question 2: Can’t you read much faster just using whole word reading? (Phonics just slows readers down.)

Answer: The reason whole word reading caught on is that in the short-term and early years, many children seem to memorize and pick up on things easily.

But whole-word learning does not work long term with ANY reader. With whole word learning, the issues come later when they cannot sound out long and difficult words they don’t know. (This was me and STILL IS my mom. She’s nearly 70 and cannot sound out unknown words effortlessly.) Whole word learning sets children up to be poor readers long-term. It’s a quick “fix” that has devastating long-term effects.

Question 3: No matter what I do, my child/student just doesn’t “get” phonics. Could it be that phonics just won’t work for this child?

Answer: No.

Learners who struggle, like those with dyslexia, will not just “get” phonics. Phonics has to be taught in a way that spells out the how and why of phonics. It has to be broken down into bit-size steps that start with more common phonics skills and moves to less common skills. It has to move from easier skills to harder skills. Read more about this kind of teaching in my post: What is Structured Literacy?

Question 4: My learner can’t sound out the simplest words!! What am I doing wrong?

Answer: With learners that struggle, it’s going to take MUCH longer to learn phonics because their brain is literally wired differently. And the steps you need to take a baby ones.

For example, instead of focusing on all the letters of the alphabet, start with just these five: m, s, t, p, and a. Build words with them like at, mat, sat, pat, map, tap, sap, am, Sam, Pam & sap. Read these words, spell these words. Start SIMPLE and move to more, always mixing in review letters when you introduce new material.

Another common deficit struggling learners have is phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear the sounds in words. For example, if you asked, “What are the sounds you hear in the word cat, a child with phonemic awareness could separate the three sounds: /k/-/a/-/t/.

I HIGHLY recommend (for the classroom teacher, homeschooler, or tutor) All About Reading & All About Spelling. They are both based on the Orton Gilligham approach, which teaches learners explicitly with step-by-step lessons.

Still Got Questions?

Here are a few posts that can help:

- Help for Struggling Readers

- Tips for Teaching High Frequency Words {Sight Words}

- The Difference Between Phonological Awareness, Phonemic Awareness, and Phonics

- 3 Important Skills Needed for Reading

- FREE Blending CVC Cards

- Reading Unknown Words from the Inside Out

- Helping Kids Sound Out Words

- K-2 Phonics Skill List

Enjoy teaching!

~Becky

Optilexia: Guessing words instead of reading them.

What causes it and what can you do?

This is the big one, especially for the brightest children.

Most of the children we help are trying to read whole words by sight, rather than decoding them. That leads to lots of errors with short, easy words, because they tend to be very interchangeable. We see it so often we have coined the term optilexia as shorthand for mainly-reading-whole-words-by-sight.

The symptoms of Optilexia

This is what you will tend to see with an Optilexic:

- Lots of guessing with the short words but sometimes reads a long word fluently

- Reads a word on one page but not the next

- Incapable of reading unfamiliar words unless there is a clear context clue

- Very poor spelling in free writing, but sometimes quite good in spelling tests

- Might seem to progress well in the early years, but then hits a plateau aged 6-9

- Potentially far lower comprehension than you would expect for the intelligence of the child

- A lack of interest in reading

What is the solution to Optilexia?

The solution to this is to give the child the tools to engage with the phonic structure of each word and then force the engagement of the auditory cortex.

Easyread has been developed as a solution for exactly this situation and I don’t know of anything that comes close to the same effectiveness we have achieved with Easyread. So I will give examples from Easyread as to how Optilexia can be solved for the child.

First, we take the visual strength of the child and use it to help guide the child towards proper phonic decoding of the text, using our trainertext visual phonics system. This allows the child to access the phonemes within each word and then blend them successfully, without needing outside help.

Second, we create games that can be easily won if the words are decoded in this way, but are impossible if the child tries to use the familiar strategies of sight-memorization and guessing.

As they practise the new approach day by day, it slowly becomes more natural to them. Like any skill, it takes regular practice to see the change and seems harder when you first change technique. But eventually the new approach leads to far higher confidence, reading accuracy, and reading speed.

Because the child is now engaged with the internal structure of the text, we usually see a marked improvement in spelling, although seeing this change will lag behind the reading proficiency.