-

Anthropologist are now looking closer at cave paintings as a form of communication. Von Petzinger, a PhD student at the University of Victoria who has been studying prehistoric signs in European caves for a decade, says they suggest «the first glimmers of graphic communication» before the written word. Cave paintings acted as a precursor before the development of written word, as the development of a writing system had to come from some basic idea.

-

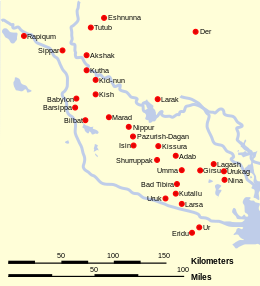

Written word emerges in around 3100 BCE in Sumer, Mesopotamia. This system of writing was called Cuneiform and was made by drawing marks in wet clay with a reed implement. In cuneiform, a stylus is pressed into soft clay to produce wedge-like mark that represent word-signs (pictographs) and, later, phonograms or (word-concepts).

-

Early cuneiform tablets were known as proto-cuneiform. At first, cuneiform was representational. A bull might be represented by a picture of a bull, and a pictograph of barley signified the word barley. The writings became abstract as it evolved to encompass more abstract concepts, eventually creating the writing system of Cuneiform. The evolution of Cuneiform occurred in stages. In stage one it was used for commercial transactions and the transactions were represented by tokens.

-

In the next stage, pictographs were drawn into wet clay, replacing the token method. With cuneiform, writers could tell stories, relate histories, and support the rule of kings. Furthermore, cuneiform was used to communicate and formalize legal systems, most famously Hammurabi’s Code.

The expansion of cuneiform began in the 3rd millennium, when the country of Elam in southwestern Iran adopted the system of writing. -

The Elamite version of cuneiform continued into the 1st millennium BCE. It also provided the Indo-European Persians with the model for creating a new simplified quasi-alphabetic cuneiform writing for the Old Persian language.

The Hurrians in northern Mesopotamia adopted a different form of cuneiform around 2000 BCE and passed it on to the Indo-European Hittites.

In the 2nd millennium cuneiform writing became a universal medium of written communication. -

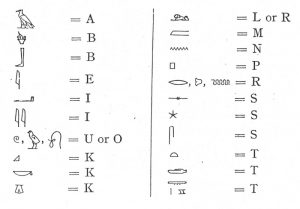

The Egyptian characters were names hieroglyphs by the Greeks in about 500 BC, because this form of writing was used for holy texts. ‘Hieros’ and ‘Glypho’ mean ‘sacred’ and ‘engrave’ in Greek. The Egyptian scribe would use a fine reed pen to write on the smooth surface of the papyrus scroll.

-

The Indus script, although not deciphered yet, is known from its thousands of seals, carved in steatite or soapstone.

Usually the center of each seal has a realistic depiction of an animal, with a short line of formal symbols. The lack of longer scripts or texts suggests that this script was probably only used for trading and accountancy purposes. -

The last of the early civilizations to develop writing is China. Chinese characters are extremely difficult when printing, typewriting or word-processing because of the complex characters. Yet they have survived.

The non-phonetic Chinese script has been a crucial binding agent in China’s vast empire. Those who are often unable to speak each other’s language, have been able to communicate fluently in writing through Chinese script. -

The Olmec, are regarded as America’s first civilization, existed from about 1500 to 400 BC. They lived in what is known as the Olmec heartland, in Mexico on the southern tip of the Gulf of Mexico.

Cascajal Block, an ancient slab of writing which is thought to be the oldest known writing system in the Western Hemisphere. This block dates to the first millennia BC. The block shows linear arrangements of certain characters that appear to be depictions of tribal objects. -

Phoenician was the first major phonemic script. Compared to Cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs, it contained only about two dozen distinct letters. This script was simple enough that everyone could learn it. Because it recorded words phonetically, it could be used in any language, unlike the writing systems that were already existent. The script was spread by the Phoenicians across the Mediterranean.

-

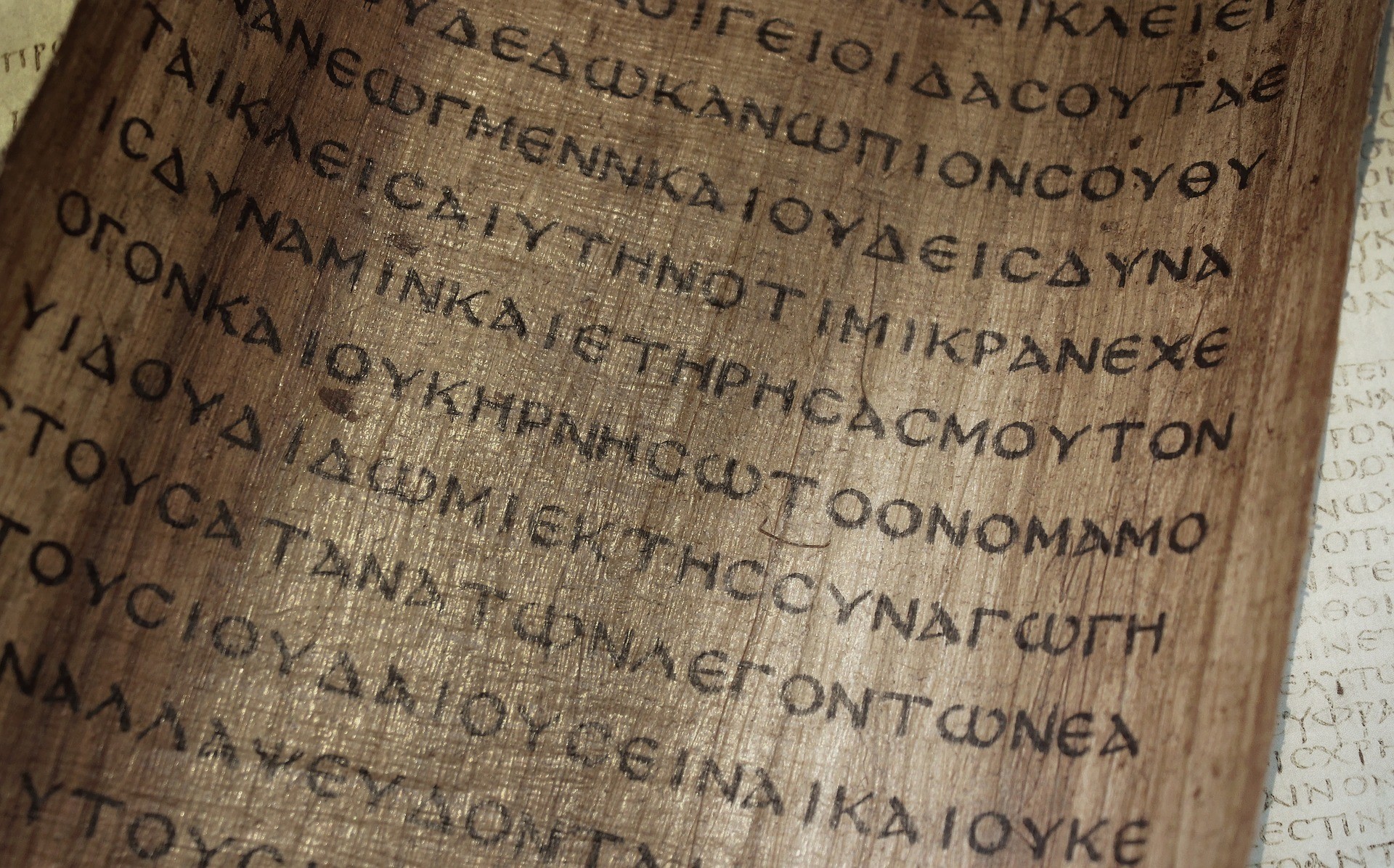

In Greece, vowels were added to the script, giving rise to the first true alphabet. The Greeks took letters which did not represent sounds in Greek, and changed them to represent the vowels.With both vowels and consonants as explicit symbols in a single script, this made the script a true alphabet. In the early years, there were many variations of the Greek alphabet, and many alphabets evolved from this one.

-

The Romans in their turn developed the Greek alphabet to form letters suitable for the writing of Latin. Through the Roman empire the alphabet spread through Europe, and eventually through much of the world, as a standard system of writing

-

Cuneiform and its international prestige of the 2nd millennium had been exhausted by 500 BCE.

-

The Arabic alphabet is one of the most used writing systems in the world. It can be found in large parts of Africa and Western and Central Asia, as well as in smaller communities in East Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Although Arabic scripts are most common after creation of Islam in the 7th century CE, the origin of the Arabic alphabet lies goes further back.

-

The Nabataeans, who established a kingdom in modern-day Jordan, were Arabs. They wrote with a cursive Aramaic-derived alphabet that would eventually evolve into the Arabic alphabet.

Nabataean inscriptions continue to appear until the 4th century CE, coinciding with the first inscriptions in the Arabic alphabet. -

The writing system of the Mayan developed from the less sophisticated systems of the Olmec civilization. The Mayans began their writing system during the second half of the Middle Pre Classic period. The system of writing used by the Mayan people until the end of the 17th century, 200 years after the Spanish conquest of Mexico.

-

Ulfilas’ outstanding contribution to writing is his invention of the Gothic alphabet, which he created from Greek and Latin. Ulfilas invented the Gothic alphabet, a writing system, in the 4th century AD. The Gothic alphabet had 27 letters. The Gothic alphabet is similar to Greek and Latin, but there are differences in phonetic values and in the order of the letters.

-

In 700 BC the pressure of business caused the Egyptian scribes to develop a more abbreviated version of the hieratic script. Parts were still the same Egyptian hieroglyphs, established more than 2000 years before, but they are now so elided that the result looks like an entirely new script. Known as demotic (‘for the people’), it is harder to read than the earlier written versions of hieroglyphics.

Both hieroglyphics and demotic continue to be used until about 400 AD.

-

Manuscripts gained popularity in Italy in the 7th to 8th century. People began using them to create a neat and formal look with all capital letters. To emphasize the beginning of an important passage, first letter was written much larger than the rest of the text and in a grander style. The following letters were in smaller ordinary text. This distinction between capital and under case letters, is the same one we use today.

-

Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in the 15th century. This invention furthered the ability to mass produce books and the rapid spread of knowledge throughout Europe.

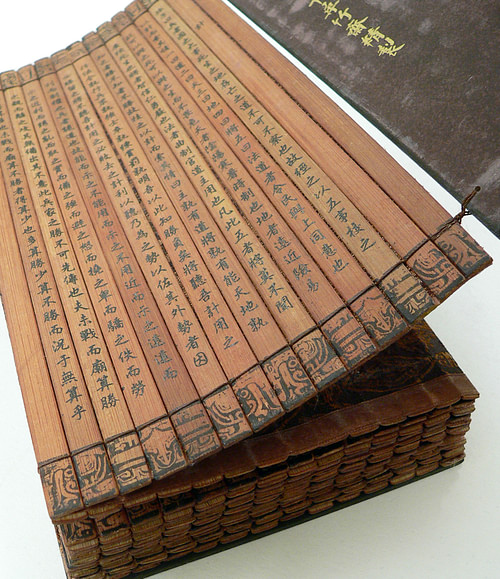

Gutenberg’s invention was inspired by the Chinese monks who set ink into paper using a method known as block printing. Block printing is the process in which wooden blocks are coated with ink and pressed to sheets of paper. -

Charles Fenerty invented paper from wood pulp as early around 1841. He was concerned about the difficulty a local paper mill was having in obtaining an adequate supply of rags to make quality paper, so he created his own.

-

Today many teens communicate through emojis. Experts say emojis can help some teenagers express themselves. Nearly 40 percent of Millennials, or people between 18 and 34, say emojis and GIFs are a much better way to communicate their thoughts and feelings than words.

Writing is the physical manifestation of a spoken language. It is thought that human beings developed language c. 35,000 BCE as evidenced by cave paintings from the period of the Cro-Magnon Man (c. 50,000-30,000 BCE) which appear to express concepts concerning daily life. These images suggest a language because, in some instances, they seem to tell a story (say, of a hunting expedition in which specific events occurred) rather than being simply pictures of animals and people.

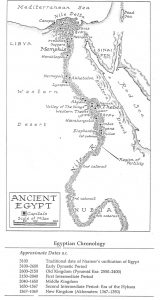

Written language, however, does not emerge until its invention in Sumer, southern Mesopotamia, c. 3500 -3000 BCE. This early writing was called cuneiform and consisted of making specific marks in wet clay with a reed implement. The writing system of the Egyptians was already in use before the rise of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 BCE) and is thought to have developed from Mesopotamian cuneiform (though this theory is disputed) and came to be known as heiroglyphics.

The phoenetic writing systems of the Greeks («phoenetic» from the Greek phonein — «to speak clearly»), and later the Romans, came from Phoenicia. The Phoenician writing system, though quite different from that of Mesopotamia, still owes its development to the Sumerians and their advances in the written word. Independently of the Near East or Europe, writing was developed in Mesoamerica by the Maya c. 250 CE with some evidence suggesting a date as early as 500 BCE and, also independently, by the Chinese.

YouTube

Follow us on YouTube!

Writing & History

Writing in China developed from divination rites using oracle bones c. 1200 BCE and appears to also have arisen independently as there is no evidence of cultural transference at this time between China and Mesopotamia. The ancient Chinese practice of divination involved etching marks on bones or shells which were then heated until they cracked. The cracks would then be interpreted by a Diviner. If that Diviner had etched `Next Tuesday it will rain’ and `Next Tuesday it will not rain’ the pattern of the cracks on the bone or shell would tell him which would be the case. In time, these etchings evolved into the Chinese script.

History is impossible without the written word as one would lack context in which to interpret physical evidence from the ancient past. Writing records the lives of a people and so is the first necessary step in the written history of a culture or civilization. A prime example of this problem is the difficulty scholars of the late 19th/early 20th centuries CE had in understanding the Maya Civilization, in that they could not read the glyphs of the Maya and so wrongly interpreted much of the physical evidence they excavated. The early explorers of the Maya sites, such as Stephens and Catherwood, believed they had found evidence of an ancient Egyptian civilization in Central America.

This same problem is evident in understanding the ancient Kingdom of Meroe (in modern day Sudan), whose Meroitic Script is yet to be deciphered as well as the so-called Linear A script of the ancient Minoan culture of Crete which also has yet to be understood.

Love History?

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

The Sumerians first invented writing as a means of long-distance communication which was necessitated by trade.

The Invention of Writing

The Sumerians first invented writing as a means of long-distance communication which was necessitated by trade. With the rise of the cities in Mesopotamia, and the need for resources which were lacking in the region, long-distance trade developed and, with it, the need to be able to communicate across the expanses between cities or regions.

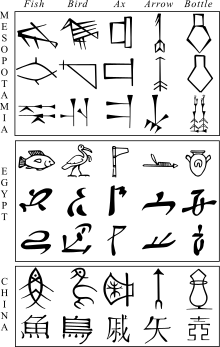

The earliest form of writing was pictographs – symbols which represented objects – and served to aid in remembering such things as which parcels of grain had gone to which destination or how many sheep were needed for events like sacrifices in the temples. These pictographs were impressed onto wet clay which was then dried, and these became official records of commerce. As beer was a very popular beverage in ancient Mesopotamia, many of the earliest records extant have to do with the sale of beer. With pictographs, one could tell how many jars or vats of beer were involved in a transaction but not necessarily what that transaction meant. As the historian Kriwaczek notes,

All that had been devised thus far was a technique for noting down things, items and objects, not a writing system. A record of `Two Sheep Temple God Inanna’ tells us nothing about whether the sheep are being delivered to, or received from, the temple, whether they are carcasses, beasts on the hoof, or anything else about them. (63)

In order to express concepts more complex than financial transactions or lists of items, a more elaborate writing system was required, and this was developed in the Sumerian city of Uruk c. 3200 BCE. Pictograms, though still in use, gave way to phonograms – symbols which represented sounds – and those sounds were the spoken language of the people of Sumer. With phonograms, one could more easily convey precise meaning and so, in the example of the two sheep and the temple of Inanna, one could now make clear whether the sheep were going to or coming from the temple, whether they were living or dead, and what role they played in the life of the temple. Previously, one had only static images in pictographs showing objects like sheep and temples. With the development of phonograms one had a dynamic means of conveying motion to or from a location.

Further, whereas in earlier writing (known as proto-cuneiform) one was restricted to lists of things, a writer could now indicate what the significance of those things might be. The scholar Ira Spar writes:

This new way of interpreting signs is called the rebus principle. Only a few examples of its use exist in the earliest stages of cuneiform from between 3200 and 3000 B.C. The consistent use of this type of phonetic writing only becomes apparent after 2600 B.C. It constitutes the beginning of a true writing system characterized by a complex combination of word-signs and phonograms—signs for vowels and syllables—that allowed the scribe to express ideas. By the middle of the Third Millennium B.C., cuneiform primarily written on clay tablets was used for a vast array of economic, religious, political, literary, and scholarly documents.

The Art of War by Sun-Tzu Coelacan (CC BY-SA)

Writing & Literature

This new means of communication allowed scribes to record the events of their times as well as their religious beliefs and, in time, to create an art form which was not possible before the written word: literature. The first writer in history known by name is the Mesopotamian priestess Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE), daughter of Sargon of Akkad, who wrote her hymns to the goddess Inanna and signed them with her name and seal.

The so-called Matter of Aratta, four poems dealing with King Enmerkar of Uruk and his son Lugalbanda, were probably composed between 2112-2004 BCE (though only written down between 2017-1763 BCE). In the first of them, Enmerkar and The Lord of Aratta, it is explained that writing developed because the messenger of King Enmerkar, going back and forth between him and the King of the city of Aratta, eventually had too much to remember and so Enmerkar had the idea to write his messages down; and so writing was born.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, considered the first epic tale in the world and among the oldest extant literature, was composed at some point earlier than c. 2150 BCE when it was written down and deals with the great king of Uruk (and descendent of Enmerkar and Lugalbanda) Gilgamesh and his quest for the meaning of life. The myths of the people of Mesopotamia, the stories of their gods and heroes, their history, their methods of building, of burying their dead, of celebrating feast days, were now all able to be recorded for posterity. Writing made history possible because now events could be recorded and later read by any literate individual instead of relying on a community’s storyteller to remember and recite past events. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer comments:

[The Sumerians] originated a system of writing on clay which was borrowed and used all over the Near East for some two thousand years. Almost all that we know of the early history of western Asia comes from the thousands of clay documents inscribed in the cuneiform script developed by the Sumerians and excavated by archaeologists. (4)

So important was writing to the Mesopotamians that, under the Assyrian King Ashurbanipal (r. 685-627 BCE) over 30,000 clay tablet books were collected in the library of his capital at Nineveh. Ashurbanipal was hoping to preserve the heritage, culture, and history of the region and understood clearly the importance of the written word in achieving this end. Among the many books in his library, Ashurbanipal included works of literature, such as the tale of Gilgamesh or the story of Etana, because he realized that literature articulates not just the story of a certain people, but of all people. The historian Durant writes:

Literature is at first words rather than letters, despite its name; it arises as clerical chants or magic charms, recited usually by the priests, and transmitted orally from memory to memory. Carmina, as the Romans named poetry, meant both verses and charms; ode, among the Greeks, meant originally a magic spell; so did the English rune and lay, and the German Lied. Rhythm and meter, suggested, perhaps, by the rhythms of nature and bodily life, were apparently developed by magicians or shamans to preserve, transmit, and enhance the magic incantations of their verse. Out of these sacerdotal origins, the poet, the orator, and the historian were differentiated and secularized: the orator as the official lauder of the king or solicitor of the deity; the historian as the recorder of the royal deeds; the poet as the singer of originally sacred chants, the formulator and preserver of heroic legends, and the musician who put his tales to music for the instruction of populace and kings.

Book of the Dead Papyrus Mark Cartwright (CC BY-NC-SA)

The Alphabet

The role of the poet in preserving heroic legends would become an important one in cultures throughout the ancient world. The Mesopotamian scribe Shin-Legi-Unninni (wrote 1300-1000 BCE) would help preserve and transmit The Epic of Gilgamesh. Homer (c. 800 BCE) would do the same for the Greeks and Virgil (70-19 BCE) for the Romans. The Indian epic Mahabharata (written down c. 400 BCE) preserves the oral legends of that region in the same way the tales and legends of Scotland and Ireland do. All of these works, and those which came after them, were only made possible through the advent of writing.

The early cuneiform writers established a system which would completely change the nature of the world in which they lived. The past, and the stories of the people, could now be preserved through writing. The Phoenicians’ contribution of the alphabet made writing easier and more accessible to other cultures, but the basic system of putting symbols down on paper to represent words and concepts began much earlier. Durant notes:

The Phoenicians did not create the alphabet, they marketed it; taking it apparently from Egypt and Crete, they imported it piecemeal to Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos, and exported it to every city on the Mediterranean; they were the middlemen, not the producers, of the alphabet. By the time of Homer the Greeks were taking over this Phoenician – or the allied Aramaic – alphabet, and were calling it by the Semitic names of the first two letters, Alpha, Beta; Hebrew Aleph, Beth.

Early writing systems, imported to other cultures, evolved into the written language of those cultures so that the Greek and Latin would serve as the basis for European script in the same way that the Semitic Aramaic script would provide the basis for Hebrew, Arabic, and possibly Sanskrit. The materials of writers have evolved as well, from the cut reeds with which early Mesopotamian scribes marked the clay tablets of cuneiform to the reed pens and papyrus of the Egyptians, the parchment of the scrolls of the Greeks and Romans, the calligraphy of the Chinese, on through the ages to the present day of computerized composition and the use of processed paper.

In whatever age, since its inception, writing has served to communicate the thoughts and feelings of the individual and of that person’s culture, their collective history, and their experiences with the human condition, and to preserve those experiences for future generations.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Six major historical writing systems (left to right, top to bottom: Sumerian pictographs, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Chinese syllabograms, Old Persian cuneiform, Roman alphabet, Indian Devanagari) |

The history of writing traces the development of expressing language by systems of markings[1] and how these markings were used for various purposes in different societies, thereby transforming social organization. Writing systems are the foundation of literacy and literacy learning, with all the social and psychological consequences associated with literacy activities.

In the history of how writing systems have evolved in human civilizations, more complete writing systems were preceded by proto-writing, systems of ideographic or early mnemonic symbols (symbols or letters that make remembering them easier). True writing, in which the content of a linguistic utterance is encoded so that another reader can reconstruct, with a fair degree of accuracy, the exact utterance written down, is a later development. It is distinguished from proto-writing, which typically avoids encoding grammatical words and affixes, making it more difficult or even impossible to reconstruct the exact meaning intended by the writer unless a great deal of context is already known in advance.

The earliest uses of writing in ancient Sumeria were to document agricultural produce and create contracts, but soon writing became used for purposes of finances, religion, government, and law. These uses supported the spread of these social activities, their associated knowledge, and the extension of centralized power.[2] Writing then became the basis of knowledge institutions such as libraries, schools, universities and scientific and disciplinary research. These uses were accompanied by the proliferation of genres, which typically initially contained markers or reminders of the social situations and uses, but the social meaning and implications of genres often became more implicit as the social functions of these genres became more recognizable in themselves, as in the examples of money, currency, financial instruments, and now digital currency.

Writing systems[edit]

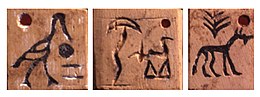

Pre-cuneiform tags, with drawing of goat or sheep and number (probably «10»), Al-Hasakah, 3300–3100 BCE, Uruk culture[3][4]

Symbolic communication systems are distinguished from writing systems. With writing systems, one must usually understand something of the associated spoken language to comprehend the text. In contrast, symbolic systems, such as information signs, painting, maps, and mathematics, often do not require prior knowledge of a spoken language. Every human community possesses language, a feature regarded by many as an innate and defining condition of humanity (see Origin of language). However the development of writing systems, and their partial replacement of traditional oral systems of communication, have been sporadic, uneven, and slow. Once established, writing systems on the whole change more slowly than their spoken counterparts and often preserve features and expressions that no longer exist in the spoken language.

Writing systems typically satisfy three criteria: Firstly, writing must be complete; it must have a purpose or some sort of meaning to it, and a point must be made or communicated in the text. Secondly, all writing systems must have some sort of symbols which can be made on some sort of surface, whether physical or digital. Thirdly, the symbols used in the writing system typically also mimic spoken word/speech, in order for communication to be possible.[5][page needed]

The greatest benefit of writing is that it provides the tool by which society can record information consistently and in greater detail, something that could not be achieved as well previously by spoken word. Writing allows societies to transmit information and to share and preserve knowledge.

Recorded history of writing[edit]

Some notational signs, used next to images of animals, may have appeared as early as the Upper Palaeolithic in Europe circa 35,000 BCE, and may be the earliest proto-writing: several symbols were used in combination as a way to convey seasonal behavioural information about hunted animals.[6]

The origins of writing are more generally attributed to the start of the pottery-phase of the Neolithic, when clay tokens were used to record specific amounts of livestock or commodities.[7] These tokens were initially impressed on the surface of round clay envelopes and then stored in them.[7] The tokens were then progressively replaced by flat tablets, on which signs were recorded with a stylus. Actual writing is first recorded in Uruk, at the end of the 4th millennium BCE, and soon after in various parts of the Near East.[7]

An ancient Mesopotamian poem gives the first known story of the invention of writing:

Because the messenger’s mouth was heavy and he couldn’t repeat (the message), the Lord of Kulaba patted some clay and put words on it, like a tablet. Until then, there had been no putting words on clay.

Scholars make a reasonable distinction between prehistory and history of early writing[10] but have disagreed concerning when prehistory becomes history and when proto-writing became «true writing». The definition is largely subjective.[11] Writing, in its most general terms, is a method of recording information and is composed of graphemes, which may, in turn, be composed of glyphs.[12]

The emergence of writing in a given area is usually followed by several centuries of fragmentary inscriptions. Historians mark the «historicity» of a culture by the presence of coherent texts in the culture’s writing system(s).[10]

Inventions of writing[edit]

Writing was long thought to have been invented in a single civilization, a theory named «monogenesis».[13] Scholars believed that all writing originated in ancient Sumer (in Mesopotamia) and spread over the world from there via a process of cultural diffusion.[13] According to this theory, the concept of representing language by written marks, though not necessarily the specifics of how such a system worked, was passed on by traders or merchants traveling between geographical regions.[a][14]

However, the discovery of the scripts of ancient Mesoamerica, far away from Middle Eastern sources, proved that writing had been invented more than once. Scholars now recognize that writing may have independently developed in at least four ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia (between 3400 and 3100 BCE), Egypt (around 3250 BCE),[15][16][13] China (1200 BCE),[17] and lowland areas of Mesoamerica (by 500 BCE).[18]

Regarding ancient Egypt, several scholars[15][19][20] have argued that «the earliest solid evidence of Egyptian writing differs in structure and style from the Mesopotamian and must therefore have developed independently. The possibility of ‘stimulus diffusion’ from Mesopotamia remains, but the influence cannot have gone beyond the transmission of an idea.»[15][21]

Regarding China, it is believed that ancient Chinese characters are an independent invention because there is no evidence of contact between ancient China and the literate civilizations of the Near East,[22] and because of the distinct differences between the Mesopotamian and Chinese approaches to logography and phonetic representation.[23]

Debate surrounds the Indus script of the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilisation, the Rongorongo script of Easter Island, and the Vinča symbols dated around 5500 BCE. All are undeciphered, and so it is unknown if they represent authentic writing, proto-writing, or something else.

The Sumerian archaic (pre-cuneiform) writing and Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally considered the earliest true writing systems, both emerging out of their ancestral proto-literate symbol systems from 3400 to 3100 BCE, with earliest coherent texts from about 2600 BCE. The Proto-Elamite script is also dated to the same approximate period.[24]

Developmental stages[edit]

Standard reconstruction of the development of writing.[25][26] There is a possibility that the Egyptian script was invented independently from the Mesopotamian script.[9] This diagram excludes the writing systems found in Mesoamerica by 500 BCE.

A conventional «proto-writing to true writing» system follows a general series of developmental stages:

- Picture writing system: glyphs (simplified pictures) directly represent objects and concepts. In connection with this, the following substages may be distinguished:

- Mnemonic: glyphs primarily as a reminder.

- Pictographic: glyphs directly represent an object or a concept such as (A) chronological, (B) notices, (C) communications, (D) totems, titles, and names, (E) religious, (F) customs, (G) historical, and (H) biographical.

- Ideographic: graphemes are abstract symbols that directly represent an idea or concept.

- Transitional system: graphemes refer not only to the object or idea that it represents but to its name as well.

- Phonetic system: graphemes refer to sounds or spoken symbols, and the form of the grapheme is not related to its meanings. This resolves itself into the following substages:

- Verbal: grapheme (logogram) represents a whole word.

- Syllabic: grapheme represents a syllable.

- Alphabetic: grapheme represents an elementary sound.

The best known picture writing system of ideographic or early mnemonic symbols are:

- Jiahu symbols, carved on tortoise shells in Jiahu, c. 6600 BCE

- Vinča symbols (Tărtăria tablets), c. 5300 BCE[27]

- Early Indus script, c. 3100 BCE

In the Old World, true writing systems developed from neolithic writing in the Early Bronze Age (4th millennium BCE).

Locations and timeframes[edit]

Examples of the Jiahu symbols, markings found on tortoise shells, dated around 6000 BCE. Most of the signs were separately inscribed on different shells.[28][29]

Proto-writing[edit]

The first writing systems of the Early Bronze Age were not a sudden invention. Rather, they were a development based on earlier traditions of symbol systems that cannot be classified as proper writing, but have many of the characteristics of writing. These systems may be described as «proto-writing». They used ideographic or early mnemonic symbols to convey information, but it probably directly contained no natural language.

These systems emerged in the early Neolithic period, as early as the 7th millennium BCE, and include:

- The Jiahu symbols found carved in tortoise shells in 24 Neolithic graves excavated at Jiahu, Henan province, northern China, with radiocarbon dates from the 7th millennium BCE.[30] Most archaeologists consider these not directly linked to the earliest true writing.[31]

- Vinča symbols, sometimes called the «Danube script», are a set of symbols found on Neolithic era (6th to 5th millennia BCE) artifacts from the Vinča culture of Central Europe and Southeast Europe.[32]

- The Dispilio Tablet of the late 6th millennium may also be an example of proto-writing.

- The Indus script, which from 3500 BCE to 1900 BCE was used for extremely short inscriptions.

Even after the Neolithic, several cultures went through an intermediate stage of proto-writing before they used proper writing. The quipu of the Incas (15th century CE), sometimes called «talking knots», may have been such a system. Another example is the pictographs invented by Uyaquk before the development of the Yugtun syllabary for the Central Alaskan Yup’ik language in about 1900.

Bronze Age writing[edit]

Writing emerged in many different cultures in the Bronze Age. Examples are the cuneiform writing of the Sumerians, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Cretan hieroglyphs, Chinese logographs, Indus script, and the Olmec script of Mesoamerica. The Chinese script likely developed independently of the Middle Eastern scripts around 1600 BCE. The pre-Columbian Mesoamerican writing systems (including Olmec and Maya scripts) are also generally believed to have had independent origins.

It is thought that the first true alphabetic writing was developed around 2000 BCE for Semitic workers in the Sinai by giving mostly Egyptian hieratic glyphs Semitic values (see History of the alphabet and Proto-Sinaitic alphabet). The Geʽez writing system of Ethiopia is considered Semitic. It is likely to be of semi-independent origin, having roots in the Meroitic Sudanese ideogram system.[33] Most other alphabets in the world today either descended from this one innovation, many via the Phoenician alphabet, or were directly inspired by its design. In Italy, about 500 years passed from the early Old Italic alphabet to Plautus (c. 750–250 BCE), and in the case of the Germanic peoples, the corresponding time span is again similar, from the first Elder Futhark inscriptions to early texts like the Abrogans (c. 200–750 CE).

Cuneiform script[edit]

Tablet with proto-cuneiform pictographic characters (end of 4th millennium BCE), Uruk III

The original Sumerian writing system derives from a system of clay tokens used to represent commodities. By the end of the 4th millennium BCE, this had evolved into a method of keeping accounts, using a round-shaped stylus impressed into soft clay at different angles for recording numbers. This was gradually augmented with pictographic writing by using a sharp stylus to indicate what was being counted. By the 29th century BCE, writing, at first only for logograms, using a wedge-shaped stylus (hence the term cuneiform) developed to include phonetic elements, gradually replacing round-stylus and sharp-stylus writing by around 2700–2500 BCE. About 2600 BCE, cuneiform began to represent syllables of the Sumerian language. Finally, cuneiform writing became a general purpose writing system for logograms, syllables, and numbers. From the 26th century BCE, this script was adapted to the Akkadian language, and from there to others, such as Hurrian and Hittite. Scripts similar in appearance to this writing system include those for Ugaritic and Old Persian.

Egyptian hieroglyphs[edit]

Designs on some of the labels or tokens from Abydos, carbon-dated to circa 3400–3200 BCE and among the earliest form of writing in Egypt.[34][35] They are remarkably similar to contemporary clay tags from Uruk, Mesopotamia.[36]

Writing was very important in maintaining the Egyptian empire, and literacy was concentrated among an educated elite of scribes.[citation needed] Only people from certain backgrounds were allowed to train as scribes, in the service of temple, royal (pharaonic), and military authorities.

Geoffrey Sampson stated that Egyptian hieroglyphs «came into existence a little after Sumerian script, and, probably [were], invented under the influence of the latter»,[37] and that it is «probable that the general idea of expressing words of a language in writing was brought to Egypt from Sumerian Mesopotamia».[38][39] Despite the importance of early Egypt–Mesopotamia relations, given the lack of direct evidence «no definitive determination has been made as to the origin of hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt».[40] Instead, it is pointed out and held that «the evidence for such direct influence remains flimsy» and that «a very credible argument can also be made for the independent development of writing in Egypt».[41]

Since the 1990s, the discoveries of glyphs at Abydos, dated to between 3400 and 3200 BCE, may challenge the classical notion according to which the Mesopotamian symbol system predates the Egyptian one, although Egyptian writing does make a sudden appearance at that time, while on the contrary Mesopotamia has an evolutionary history of sign usage in tokens dating back to circa 8000 BCE.[35][9][42] These glyphs, found in tomb U-J at Abydos are written on ivory and are likely labels for other goods found in the grave.[43]

Frank Yurco stated that depictions of pharonic iconography such as the royal crowns, Horus falcons and victory scenes were concentrated in the Upper Egyptian Naqada culture and A-Group Nubia. He further elaborated that «Egyptian writing arose in Naqadan Upper Egypt and A-Group Nubia, and not in the Delta cultures, where the direct Western Asian contact was made, [which] further vitiates the Mesopotamian-influence argument».[44]

Egyptian scholar Gamal Mokhtar argued that the inventory of hieroglyphic symbols derived from «fauna and flora used in the signs [which] are essentially African» and in «regards to writing, we have seen that a purely Nilotic, hence African origin not only is not excluded, but probably reflects the reality» although he acknowledged the geographical location of Egypt made it a receptacle for many influences.[45]

Elamite script[edit]

The undeciphered Proto-Elamite script emerges from as early as 3100 BCE. It is believed to have evolved into Linear Elamite by the later 3rd millennium and then replaced by Elamite Cuneiform adopted from Akkadian.

Indus script[edit]

Markings and symbols found at various sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation have been labelled as the Indus script citing the possibility that they were used for transcribing the Harappan language.[46] Whether the script, which was in use from about 3500–1900 BCE, constitutes a Bronze Age writing script (logographic-syllabic) or proto-writing symbols is debated as it has not yet been deciphered. It is analyzed to have been written from right-to-left or in boustrophedon.[47]

Early Semitic alphabets[edit]

The first «abjads», mapping single symbols to single phonemes but not necessarily each phoneme to a symbol, emerged around 1800 BCE in Ancient Egypt, as a representation of language developed by Semitic workers in Egypt, but by then alphabetic principles had a slight possibility of being inculcated into Egyptian hieroglyphs for upwards of a millennium.[clarification needed] These early abjads remained of marginal importance for several centuries, and it is only towards the end of the Bronze Age that the Proto-Sinaitic script splits into the Proto-Canaanite alphabet (c. 1400 BCE) Byblos syllabary and the South Arabian alphabet (c. 1200 BCE). The Proto-Canaanite was probably somehow influenced by the undeciphered Byblos syllabary and, in turn, inspired the Ugaritic alphabet (c. 1300 BCE).

Anatolian hieroglyphs[edit]

Anatolian hieroglyphs are an indigenous hieroglyphic script native to western Anatolia, used to record the Hieroglyphic Luwian language. It first appeared on Luwian royal seals from the 14th century BCE.

Chinese writing[edit]

The earliest confirmed evidence of the Chinese script yet discovered is the body of inscriptions on oracle bones and bronze from the late Shang dynasty. The earliest of these is dated to around 1200 BCE.[48][49]

There have recently been discoveries of tortoise-shell carvings dating back to c. 6000 BCE, like Jiahu Script, Banpo Script, but whether or not the carvings are complex enough to qualify as writing is under debate.[30] At Damaidi in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, 3,172 cliff carvings dating to c. 6000–5000 BCE have been discovered, featuring 8,453 individual characters, such as the sun, moon, stars, gods, and scenes of hunting or grazing. These pictographs are reputed to be similar to the earliest characters confirmed to be written Chinese. If it is deemed to be a written language, writing in China will predate Mesopotamian cuneiform, long acknowledged as the first appearance of writing, by some 2,000 years; however it is more likely that the inscriptions are rather a form of proto-writing, similar to the contemporary European Vinca script.

Cretan and Greek scripts[edit]

Cretan hieroglyphs are found on artifacts of Crete (early-to-mid-2nd millennium BCE, MM I to MM III, overlapping with Linear A from MM IIA at the earliest). Linear B, the writing system of the Mycenaean Greeks,[50] has been deciphered while Linear A has yet to be deciphered. The sequence and the geographical spread of the three overlapping, but distinct, writing systems can be summarized as follows:[b][50]

| Writing system | Geographical area | Time span |

|---|---|---|

| Cretan Hieroglyphic | Crete (eastward from the Knossos-Phaistos axis) | c. 2100−1700 BCE |

| Linear A | Crete (except extreme southwest), Aegean Islands (Kea, Kythera, Melos, Thera), and Greek mainland (Laconia) | c. 1800−1450 BCE |

| Linear B | Crete (Knossos), and mainland (Pylos, Mycenae, Thebes, Tiryns) | c. 1450−1200 BCE |

Mesoamerica[edit]

A stone slab with 3,000-year-old writing, the Cascajal Block, was discovered in the Mexican state of Veracruz, and is an example of the oldest script in the Western Hemisphere, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing dated to about 500 BCE.[51][52][53]

Of several pre-Columbian scripts in Mesoamerica, the one that appears to have been best developed, and has been fully deciphered, is the Maya script. The earliest inscriptions which are identifiably Maya date to the 3rd century BCE, and writing was in continuous use until shortly after the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores in the 16th century CE. Maya writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs: a combination somewhat similar to modern Japanese writing.

Iron Age writing[edit]

The Phoenician alphabet is simply the Proto-Canaanite alphabet as it was continued into the Iron Age (conventionally taken from a cut-off date of 1050 BCE).[citation needed] This alphabet gave rise to the Aramaic and Greek alphabets. These in turn led to the writing systems used throughout regions ranging from Western Asia to Africa and Europe. For its part the Greek alphabet introduced for the first time explicit symbols for vowel sounds.[54] The Greek and Latin alphabets in the early centuries of the Common Era gave rise to several European scripts such as the Runes and the Gothic and Cyrillic alphabets while the Aramaic alphabet evolved into the Hebrew, Arabic and Syriac abjads, of which the latter spread as far as Mongolian script. The South Arabian alphabet gave rise to the Ge’ez abugida. The Brahmic family of India is believed by some scholars to have derived from the Aramaic alphabet as well.[55]

Grakliani Hill writing[edit]

A previously unknown script was discovered in 2015 in Georgia, over the Grakliani Hill just below a temple’s collapsed altar to a fertility goddess from the seventh century BCE. These inscriptions differ from those at other temples at Grakliani, which show animals, people, or decorative elements.[56][57] The script bears no resemblance to any alphabet currently known, although its letters are conjectured to be related to ancient Greek and Aramaic.[56] The inscription appears to be the oldest native alphabet to be discovered in the whole Caucasus region,[58] In comparison, the earliest Armenian and Georgian script date from the fifth century CE, just after the respective cultures converted to Christianity. By September 2015, an area of 31 by 3 inches of the inscription had been excavated.[56]

According to Vakhtang Licheli, head of the Institute of Archaeology of the State University, «The writings on the two altars of the temple are really well preserved. On the one altar several letters are carved in clay while the second altar’s pedestal is wholly covered with writings.»[59] The finding was made by unpaid students.[citation needed] In 2016 Grakliani Hill inscriptions were taken to Miami Laboratory for Beta analytic radiocarbon dating which found that the inscriptions were made in c. 1005 – c. 950 BCE.[citation needed]

Writing in the Greco-Roman civilizations[edit]

Greek scripts[edit]

The history of the Greek alphabet began in at least the early 8th century BCE when the Greeks adapted the Phoenician alphabet for use with their own language.[60]: 62 The letters of the Greek alphabet are more or less the same as those of the Phoenician alphabet, and in modern times both alphabets are arranged in the same order.[60] The adapter(s) of the Phoenician system added three letters to the end of the series, called the «supplementals». Several varieties of the Greek alphabet developed. One, known as Western Greek or Chalcidian, was used west of Athens and in southern Italy. The other variation, known as Eastern Greek, was used in present-day Turkey and by the Athenians, and eventually the rest of the world that spoke Greek adopted this variation. After first writing right to left, like the Phoenicians, the Greeks eventually chose to write from left to right. Occasionally however, the writer would start the next line where the previous line finished, so that the lines would read alternately left to right, then right to left, and so on. This was known as «boustrophedon» writing, which imitated the path of an ox-drawn plough, and was used until the sixth century.[61]

Italic scripts and Latin[edit]

Greek is in turn the source for all the modern scripts of Europe. The most widespread descendant of Greek is the Latin script, named for the Latins, a central Italian people who came to dominate Europe with the rise of Rome. The Romans learned writing in about the 5th century BCE from the Etruscan civilization, who used one of a number of Italic scripts derived from the western Greeks. Due to the cultural dominance of the Roman state, the other Old Italic scripts have not survived in any great quantity, and the Etruscan language is mostly lost.

Writing during the Middle Ages[edit]

With the collapse of the Roman authority in Western Europe, literacy development became largely confined to the Eastern Roman Empire and the Persian Empire. Latin, never one of the primary literary languages, rapidly declined in importance (except within the Roman Catholic Church). The primary literary languages were Greek and Persian, though other languages such as Syriac and Coptic were important too.

The rise of Islam in the 7th century led to the rapid rise of Arabic as a major literary language in the region. Arabic and Persian quickly began to overshadow Greek’s role as a language of scholarship. Arabic script was adopted as the primary script of the Persian language and the Turkish language. This script also heavily influenced the development of the cursive scripts of Greek, the Slavic languages, Latin, and other languages.[citation needed] The Arabic language also served to spread the Hindu–Arabic numeral system throughout Europe.[citation needed] By the beginning of the second millennium, the city of Córdoba in modern Spain had become one of the foremost intellectual centers of the world and contained the world’s largest library at the time.[62] Its position as a crossroads between the Islamic and Western Christian worlds helped fuel intellectual development and written communication between both cultures.

Renaissance and the modern era[edit]

By the 14th century a rebirth, or renaissance, had emerged in Western Europe, leading to a temporary revival of the importance of Greek, and a slow revival of Latin as a significant literary language. A similar though smaller emergence occurred in Eastern Europe, especially in Russia. At the same time Arabic and Persian began a slow decline in importance as the Islamic Golden Age ended. The revival of literacy development in Western Europe led to many innovations in the Latin alphabet and the diversification of the alphabet to codify the phonologies of the various languages.

The nature of writing has been constantly evolving, particularly due to the development of new technologies over the centuries. The pen, the printing press, the computer and the mobile phone are all technological developments which have altered what is written, and the medium through which the written word is produced. Particularly with the advent of digital technologies, namely the computer and the mobile phone, characters can be formed by the press of a button, rather than making a physical motion with the hand.

Writing materials[edit]

There is no very definite statement as to the material which was in most common use for the purposes of writing at the start of the early writing systems.[63] In all ages it has been customary to engrave on stone or metal, or other durable material, with the view of securing the permanency of the record. Metals, such as stamped coins, are mentioned as a material of writing; they include lead,[c] brass, and gold. There are also references to the engraving of gems, such as with seals or signets.[63]

The common materials of writing were the tablet and the roll, the former probably having a Chaldean origin, the latter an Egyptian. The tablets of the Chaldeans are small pieces of clay, somewhat crudely shaped into a form resembling a pillow, and thickly inscribed with cuneiform characters.[d] Similar use has been seen in hollow cylinders, or prisms of six or eight sides, formed of fine terracotta, sometimes glazed, on which the characters were traced with a small stylus, in some specimens so minutely as to require the aid of a magnifying-glass.[63]

In Egypt the principal writing material was of quite a different sort. Wooden tablets are found pictured on the monuments; but the material which was in common use, even from very ancient times, was the papyrus, having recorded use as far back as 3,000 BCE.[64] This reed, found chiefly in Lower Egypt, had various economic means for writing. The pith was taken out and divided by a pointed instrument into the thin pieces of which it is composed; it was then flattened by pressure, and the strips glued together, other strips being placed at right angles to them, so that a roll of any length might be manufactured. Writing seems to have become more widespread with the invention of papyrus in Egypt. That this material was in use in Egypt from a very early period is evidenced by still existing papyrus of the earliest Theban dynasties.[65] As the papyrus, being in great demand, and exported to all parts of the world, became very costly, other materials were often used instead of it, among which is mentioned leather, a few leather mills of an early period having been found in the tombs.[63] Parchment, using sheepskins left after the wool was removed for cloth, was sometimes cheaper than papyrus, which had to be imported outside Egypt. With the invention of wood-pulp paper, the cost of writing material began a steady decline. Wood-pulp paper is still used today, and in recent times efforts have been made in order to improve bond strength of fibers. Two main areas of examination in this regard have been «dry strength of paper» and «wet web strength».[66] The former involves examination of the physical properties of the paper itself, while the latter involves using additives to improve strength.

Uses and implications of writing[edit]

Writing and the economy[edit]

According to Denise Schmandt-Besserat writing had its origins in the counting and cataloguing of agricultural produce, and then economic transactions involving the produce.[67] Government tax rolls followed thereafter. Written documents became essential for the accumulation, accounting, of wealth by individuals, the state, and religious organizations as well as the transactions of trade, loans, inheritance, and documentation of ownership.[68] With such documentation and accounting larger accumulations of wealth became more possible, along with the power that accompanied wealth, most prominently to the benefit of royalty, the state, and religions. Contracts and loans supported the growth of long-distance international trade with accompanying networks for import and export, supporting the rise of capitalism.[69] Paper money (initially appearing in China in the 11th century CE)[70] and other financial instruments relied on writing, initially in the form of letters and then evolving into specialized genres, to explain the transactions and guarantees (from individuals, banks, or governments) of value inhering in the documents.[71] With the growth of economic activity in late Medieval and Renaissance Europe, sophisticated methods of accounting and calculating value emerged, with such calculations both carried out in writing and explained in manuals.[72] The creation of corporations then proliferated documents surrounding organization, management, the distribution of shares, and record-keeping.[73]

Economic theory itself only began to be developed in the latter eighteenth century through the writings of such theorists as Francois Quesnay and Adam Smith. Even the concepts of an economy and a national economy were established through their texts and the texts of their colleagues.[74] Since then economics has developed as a field with many authors contributing texts to the professional literature, and governments collecting data, instituting policies and creating institutions to manage and advance their economies. Diedre McCloskey has examined the rhetorical strategies and discursive construction of modern economic theory.[75][76][77] Graham Smart has examined in depth how the Bank of Canada uses writing to cooperatively produce policies based on economic data and then to communicate strategically with relevant publics.[78]

Writing and religion[edit]

The identification of sacred religious texts or scriptures, often claimed to be of divine origin, codified distinct belief systems associated with particular divine texts, and became the basis of the modern concept of religion.[2] The reproduction and spread of these texts became associated with these scriptural religions and their spread, and thus were central to proselytizing.[2] These sacred books created obligations of believers to read, or to follow the teachings of priests or priestly castes charged with the reading, interpretation and application of these texts. Well-known examples of such scriptures are the Torah, the Bible (with its many different compilations of books of the Old and New Testaments), the Quran, the Vedas, the Bhaghavad Gita, and the Sutras, but there are far more religious texts through the histories of different religions with many still in current use. These texts, because of their spread, tended to foster generalized guides for moral and ethical behavior, at least for all members of the religious community, but often these guidelines were considered applicable to all humans, as in the ten commandments.

Writing and the law[edit]

Private legal documents for the sale of land appeared in Mesopotamia in the early third millennium BCE, not long after the initial appearance of cuneiform writing.[79] The first written legal codes followed shortly thereafter around 2100 BCE, with the most well known being the Code of Hammurabi, inscribed on stone stellae throughout Babylon circa 1750 BCE.[80] While Ancient Egypt did not have codified laws, legal decrees and private contracts did appear in the Old Kingdom around 2150 BCE. The Torah, or the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, particularly Exodus and Deutoronomy, codified the laws of Ancient Israel. Many other codes were to follow in Greece and Rome, with Roman law to serve as a model for church canon law and secular law throughout much of Europe during later periods.[81][82]

In China the earliest indications of written codifications of law or books of punishments are inscriptions on bronze vessels in 536 BCE.[83] The earliest extant full set of laws dates back to the Qin and Han Dynasties, which set out a full system of social control and governance, with criminal procedures and accountability for both government officials and citizens. These laws required complex reporting and documenting procedures to facilitate hierarchical supervision from the village up to the imperial center.[84]

While Common Law developed in a mostly oral environment in England after the Romans left, with the return of the church and then the Norman invasion, customary law began to be inscribed as were precedents of the courts; however, many elements remained oral, with documents only memorializing public oaths, wills, land transfers, court judgments, and ceremonies. During the late Medieval period, however, documents gained authority for agreements, transactions, and laws. With the founding of the United States laws were created as statutes within written codes and controlled by central documents, including the federal and state Constitutions, with all such legislative documents printed and distributed.[85] Also court judgments were presented in written opinions which then were published and served as precedents for reasoning in consequent judgments in states and nationally. Courts of Appeals in the United States only consider documents relating to records of prior proceedings and judgements and do not take new testimony,[86]

Writing and government, states, bureaucracy, citizenship, and journalism[edit]

Writing has been central to expanding many of the core functions of governance through law, regulation, taxation, and documentary surveillance of citizens; all dependent on growth of bureaucracy which elaborates and administers rules and policies and maintains records (see red tape). These developments which rely on writing increase the power and extent of states.[2] At the same time writing has increased the ability of citizens to become informed about the operations of the state, to become more organized in expressing needs and concerns, to identify with regions and states, and to form constituencies with particular views and interests; the rise and fate of journalism is closely linked to citizen information, regional and national identity, and expression of interests. These changes have greatly influenced the nature of states, increasing the visibility of people and their views no matter what the form of governance is.

Extensive bureaucracies arose in the ancient Near East[2] and China[87][88] which relied on the formation of literate classes to be scribes and bureaucrats. In the Ancient Near East this was carried out through the formation of scribal schools,[89] while in China this led to a series of written imperial examinations based on classic texts which in effect regulated education over millennia.[90] Literacy remained associated with rise in the government bureaucracy, and printing as it emerged was tightly controlled by the government, with vernacular texts only emerging later and then being limited in their range up through the early twentieth century and the fall of the Ching dynasty.[91] In ancient Greece and Rome, class distinctions of citizen and slave, wealthy and poor limited education and participation. In Medieval and early modern Europe church dominance of education, both before and for a time after the reformation, expressed the importance of religion in the control of the state and state bureaucracies.[92]

In Europe and the colonies in the Americas the introduction of the printing press and decreasing cost of paper and printing allowed for greater access of ordinary citizens to gain information about the government and conditions in other regions within the jurisdictions.[93] The Reformation with an emphasis on individual reading of sacred texts, eventually increased the spread of literacy beyond the governing classes and opened the door to wider knowledge and criticism of government actions. Divisions in English society during the sixteenth century, the Civil War of the seventeenth century, and the increased role of parliament that followed, along with the splitting of political religious control[94] were accompanied by pamphlet wars.

Newspapers and journalism, having origins in commercial information, soon was to offer political information and was instrumental to the formation of a public sphere.[95][96] Newspapers were instrumental in the sharing of information, fostering discussion, and forming political identities in the American revolution, and then the new nation. The circulation of newspapers also created urban, regional, and state identification in the latter nineteenth century and after. A focus on national news that followed telegraphy and the emergence of newspapers with national circulation along with scripted national radio and television news broadcasts also created horizons of attention through the twentieth century, with both benefits and costs.[97]

One of the earliest known examples of a named person in writing is Kushim, from the Uruk period.[98]

Writing and knowledge[edit]

Much of what we consider knowledge is inscribed in written text and is the result of communal processes of production, sharing, and evaluation among social groups and institutions bound together with the aim of producing and disseminating knowledge-bearing texts; the contemporary world identifies such social groups as disciplines and their products as disciplinary literatures. The invention of writing facilitated the sharing, comparing, criticizing, and evaluating of texts, resulting in knowledge becoming a more communal property across wider geographic and temporal domains. Sacred scriptures formed the common knowledge of scriptural religions, and knowledge of those sacred scriptures became the focus of institutions of religious belief, interpretation, and schooling, as discussed in the section on writing and religion in this article. Other sections in this article are devoted to knowledge specific to the economy, the law, and governance. This section is devoted to the development of secular knowledge and its related social organizations, institutions, and educational practices in other domains.

Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and Mesoamerica[edit]

In Mesopotamia and Egypt, scribes became important for roles beyond the initiating roles in the economy, governance and law. They became the producers and stewards of astronomy and calendars, divination, and literary culture. Schools developed in tablet houses, which also archived repositories of knowledge.[89] In ancient India, the Brahman caste became stewards texts that aggregated and codified oral knowledge.[99] Those texts then became the authoritative basis for a continuing tradition of oral education. A case in point is the work of Pāṇini the linguist, who analyzed and codified knowledge of Sanskrit syntax, prosody and grammar. Mathematics, astronomy and medicine were also subjects of classic Indian learning and were codified in classic texts.[100] Less is known about Mayan, Aztec, and other Mesoamerican learning because of the destruction of texts by the conquistadors, but it is known that scribes were revered, elite children attended schools, and the study of astronomy, map making, historical chronicles, and genealogy flourished. [101][102]

China[edit]

In China, after the Qin dynasty attempted to remove all traces of the competing Confucian tradition, the Han dynasty made philological knowledge the qualification for the government bureaucracy, so as to restore knowledge that was in danger of vanishing. The Imperial civil service examination system, which was to last for two millennia, consisted of a written exam based on knowledge of classical texts. To support students obtaining government positions through the written examination, schools focused on those same texts and the associated philological knowledge.[90] These texts covered philosophical, religious, legal, astronomical, hydrological, mathematical, military, and medical knowledge.[103] Printing as it emerged largely served the knowledge needs of the bureaucracy and the monastery, with substantial vernacular printing only emerging around the fifteenth century CE.[91]

Ancient Greece and Rome[edit]

Ancient Greece gave rise to much written knowledge that influenced western learning for two millennia.[104] Although Plato thought writing an inferior means of transmission of learning (recounted in the Phaedrus), we know of his works through Socrates’ written accounts of his dialogues. Havelock, as well, has seen the philosophic works of Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle as arising from literacy and the ability to compare accounts from different regions and to develop systematic critical reasoning through the inspection of documents and writing coherent accounts.[105][106][107] Aristotle wrote treatises and lectures which were the core of education at the Lyceum, along with the may volumes collected in the Lyceum’s library. Other philosophers such as the Stoics and Epicureans also wrote and taught during the same period in Athens, although we now have only fragments of their works.

Greek writers were the founding writers of many other fields of knowledge. Herodotus and Thucydides writing during the fifth century BCE in Athens are considered the founders of history, transforming genealogy and mythic accounts into systematic investigations of events. Thucydides developed a more critical, neutral history through the examination of documents, transcription of speeches, and interviews. Hippocrates during the same period authored several major works of medicine codifying and advancing the knowledge of this field. In the second century CE the Greek trained physician Galen went to Rome where he wrote numerous works that dominated European medicine through the Renaissance. Hellenized writers in Egypt also produced compendia of knowledge using the resources of the great library at Alexandria, such as Euclid whose Elements of geometry remains a standard reference to today. Ptolemy’s work on astronomy dominated through the Middle Ages.

Scholars in Rome continued the practice of writing compendia of knowledge, including Varro, Pliny the Elder, and Strabo. While much of Roman accomplishment was in material culture of construction, Vitruvius documented much of the contemporary practice to influence design until today. Agriculture also became an important area for manuals, such as Palladius’ compendium. Numerous manuals of rhetoric and rhetorical education that were to influence future generations also appeared, such as the anonymous Rhetorica ad Herennium, Cicero’s de Oratore and Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria.

Islamic learning[edit]

With the fall of Rome, the Middle East became the crossroads for learning, with knowledge bearing texts from the West and East meeting in Byzantium, Damascus, and then Baghdad. In Baghdad a research institute (or House of Wisdom) with a large library was founded, where Greek works of medicine, philosophy, mathematics and astronomy were translated into Arabic, along with Indian works on mathematics and therapeutics.[108] To these texts, philosophers such as Al-Kindi and Avicenna and astronomers such as Al-Farqhani made new contributions. Al-Kharazami authored the first work on algebra, drawing on both Greek and Indian resources. The centrality of the Quran to the new Islamic religion also led to growth of Arabic Linguistics.[109] From Baghdad knowledge and texts were to flow back to South Asia and down through Africa, with a large collection of books and an educational center around the Sankhore Mosque in Timbuktu, the seat of the Songhai Empire. During this period the deposed Abbasid Caliphate moved its seat of power and learning to Córdoba, now in Spain, where they founded a major library which reintroduced many of the classic texts back into Europe along with texts of Arab learning.

Early universities in Europe[edit]

The reintroduction of classic texts into Europe through the library and intercultural intellectual culture in Córdoba, including works of Plato, Aristotle, Euclid, Ptolemy and Galen, along with Arabic texts such as by Avicenna and Al-Kharazami created a need for interpretation, lectures, and scholarship to make those works more accessible to scholars in monasteries and urban centers. During the twelfth century universities emerged from these clusters of scholars in Italy at Bologna; in Spain at Salamanca, in France at Paris and in England at Oxford.[110] By 1500 there were at least sixty universities throughout Europe[111] enrolling at least three quarters of a million students.[112] Each of the four faculties (Liberal Arts, Theology, Law, and Medicine) was devoted to the transmission of classic texts rather than the production of fresh knowledge beyond lectures and commentaries. This form of scholastic education continued well into the seventeenth century and beyond in some locations and disciplines.[113][114][115][116][117]

Printing and the growth of knowledge in Europe

Johannes Gutenberg’s European introduction of the moveable type printing press around 1450 created new opportunities for the production and widespread distribution of books, fostering much new writing, with particular consequences for the development of knowledge, as documented by Elizabeth Eisenstein.[118] The production and distribution of knowledge was no longer tied to monasteries or universities with their libraries and collections of scribal copies. In the ensuing centuries a politically and increasingly religiously divided Europe, no single authority was able to censor or control the production of books. While universities remained attached to disseminating traditional texts, publishing houses became the new centers of knowledge production, and publishing houses in different jurisdictions led to a diversity of ideas becoming available as books moved across borders and scholars came to see themselves as citizens of the Republic of Letters.

The comparison of multiple editions of traditional texts led to improved textual scholarship.[119] The ability to share and compare results from many regions and enlist more people into the production of science soon led to the development of early modern science.[118] Books of medicine began to incorporate observations from contemporary surgery and dissections, including printed plates providing graphic displays, to improve knowledge of anatomy.[120] With many copies of traditional books and new books appearing, debates arose over the value of each in what became known as the battle of the books.[121] Maps and discoveries of exploration and colonization also were recorded in books and governmental records,[122] often with the purpose of economic exploitation as in the Archives of the Indies in Seville but also to satisfy curiosity about the world.[123]

Printing also made possible the invention and development of scientific journals, with the Journal des sçavans appearing in France and The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in England both in 1665. Over the years these journals proliferated and became the basis of disciplines and disciplinary literatures.[124] Genres reporting experiments and other scientific observations and theories developed over the ensuing centuries to produce modern practices of disciplinary publication with the extensive intertexts which represent the collective pursuits of disciplinary knowledge. The availability of scientific and disciplinary books and journals also facilitated the development of modern practices of scientific reference and citation. These developments from the impact of printing on the growth of knowledge contributed to the scientific revolution, science in the Renaissance and science in the Age of Enlightenment.

Modern research university and writing[edit]

In the eighteenth century a few Scottish and English dissident universities began offering some more practical and contemporary studies offered instruction in rhetoric and writing to enable their non-elite students to influence contemporary events.[125][126] Only in the nineteenth century, however, did universities in some countries begin creating place for the writing of new knowledge, turning them in the ensuing years from primarily disseminating classic knowledge through the reading of classic texts to becoming institutions devoted to both reading and writing. The creation of research seminars and the associated seminar papers in history and philology in German Universities were a significant starting point for the reform of the university.[127] Professorships in philology, history, economy, theology, psychology, sociology, mathematics and the sciences were to emerge over the century, and the German model of disciplinary research university was to influence the organization of universities in England and the United States, with another model developing in France. Both, however, prized the production of new knowledge by faculty and to be learned by students. In elite British universities writing instruction was supported by the tutorial system with weekly writing by students for their tutors, while in the United States regular courses in writing were often required starting in the late nineteenth century, with writing across the curriculum becoming an increasing focus, particularly towards the end of the twentieth century.

Military knowledge and classified documents[edit]

Military knowledge of strategies and devices date back to the ancient worlds of Egypt, India, China, Greece, and Rome, with both historical accounts and manuals for conducting war. After printing was introduced in the West, manuals for construction of fortifications and battle strategies were widely reproduced, as nations frequently were in conflict. With the growth of chemistry and other sciences, however, knowledge of new weaponry was frequently restricted to secret documents. Other documents also of limited distribution developed around policies, production, and distribution of the new weaponry.[128] By World War I, both the Allied and Axis powers applied new technologies based on scientific advances to military uses, particularly chemical weapons, with over 5000 scientists engaged in developing and producing weaponry, while attempting to limit access to the information in secret documents.[129][130] The drive towards secret knowledge, including novel research and not just applications of prior knowledge, became especially intense with the race to develop nuclear weapons in World War II as in the U.S. Manhattan Project. Aviation, rocketry, radar, encryption, and computing were also the subject of classified documents. This system of classification of knowledge continued after WWII ended as the Cold War ensued. The tension between the needs for military secrecy, open scientific research, and citizen deliberation over military policy led in the United States led to the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, which created civilian control, but through a continuing regime of classified knowledge.[131][132]

Literature and writing[edit]

The history of literature followed after the development of writing in Sumer, which was initially used for accounting purposes. The very first writings from ancient Sumer by any reasonable definition do not constitute literature. The same is true of some of the early Egyptian hieroglyphics and the thousands of ancient Chinese government records. Scholars have disagreed concerning when written record-keeping became more like literature, but the oldest surviving literary texts date from a full millennium after the invention of writing. The earliest literary author known by name is Enheduanna, who is credited as the author of a number of works of Sumerian literature, including Exaltation of Inanna, in the Sumerian language during the 24th century BCE.[133][134] The next earliest named author is Ptahhotep, who is credited with authoring The Maxims of Ptahhotep, an instructional book for young men in Egyptian composed in the 23rd century BCE.[135] The Epic of Gilgamesh is an early notable poem, but it can also be seen as a political glorification of the historical King Gilgamesh of Sumer whose natural and supernatural accomplishments are recounted.

Psychological implications of writing[edit]

Walter Ong, Jack Goody, and Eric Havelock were among the earliest to systematically argue for the psychological and intellectual consequences of literacy. Ong argued that the introduction of writing changed the form of human consciousness from sensing the immediacy of the spoken word to the critical distance and systematization of words, which could be graphically displayed and ordered,[136][137] such as in the works of Peter Ramus.[138] Havelock attributed the emergence of Greek philosophic thought to the use of the written word which allowed the comparison of beliefs and belief systems and the critical examination of concepts.[105][107] Jack Goody argued that written language fostered such practices as categorization, making lists, following formulas, developing recipes and prescriptions, and ultimately making and recording experiments. These practices changed the intellectual and psychological orientation of those who engaged with them.[139][140]

While recognizing the possibilities of all these psychological and intellectual changes that accompanied these literate practices, Sylvia Scribner and Michael Cole argued that these changes did not come universally or automatically with literacy, but rather were dependent on the social uses made of literacy in their local contexts.[141] They carried out field observation and experiments among the Vai people of West Africa, for whom the psychological impacts of literacy vary due to the three different contexts in which locals learn to read and write the Vai language, English, and Arabic—practical skills, secular education, and religious education, respectively. European language literacies were associated with European style schooling, and fostered among other things syllogistic reasoning and logical problem solving. Arabic literacy was associated with the religious training of Madrasas and fostered, among other things, heightened rote memory. Literacy in the written forms of Vai associated with daily practices of making requests and explaining tasks, increased anticipation of audience knowledge and needs along with rebus solving (as the written language used rebus-like icons).

Following a different line of Inquiry, James Pennebaker and colleagues have carried out many experiments establishing that writing about traumas can relieve anxiety, improve mental well-being, and improve physical health measures and outcomes.[142][143]

See also[edit]

- History of numbers

- History of art

- List of writing systems

- History of journalism

- History of newspaper publishing