Who invented Microsoft Word? Software developers Richard Brodie and Charles Simonyi released the Multi-Tool Word for the UNIX operating system in 1983. Later that year, the program was rewritten to run on personal computers under MS-DOS and was renamed Microsoft Word.

Contents

- 1 Who originally created word?

- 2 When was word invented?

- 3 Who is the father of MS Word?

- 4 Was Microsoft Word ever free?

- 5 What is the meaning of word?

- 6 How did words become words?

- 7 What was the first human word?

- 8 Who created English?

- 9 What are the 23 oldest words?

- 10 Who created MS Office?

- 11 Who invented MS Excel?

- 12 What came before Microsoft Word?

- 13 Is word free on iPhone?

- 14 Do I need Microsoft 365 to use Word?

- 15 Does Windows 10 come with Word?

- 16 Is Demonsterized a word?

- 17 What is the longest word in English?

- 18 Why do we say word?

- 19 Who invented talking?

- 20 What was the first word in English?

Who originally created word?

The first version of Microsoft Word was developed by Charles Simonyi and Richard Brodie, former Xerox programmers hired by Bill Gates and Paul Allen in 1981.

When was word invented?

Microsoft Word

| A story being written and formatted in Word, running on Windows 10 | |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Microsoft |

| Initial release | October 25, 1983 (as Multi-Tool Word) |

| Stable release | 2103 (16.0.13901.20400) / April 13, 2021 |

Who is the father of MS Word?

Charles Simonyi

Charles Simonyi, known as the “father of Microsoft Word” and Microsoft’s former research and development expert, will take a Russian manned spacecraft next month to visit the International Space Station (ISS).

Was Microsoft Word ever free?

Microsoft Office for Android and iOS

It combines Word, Excel, and PowerPoint in one app, and it’s completely free. Perhaps the best part about the free Microsoft Word on mobile is how well it represents documents filled with charts and graphics.

What is the meaning of word?

1 : a sound or combination of sounds that has meaning and is spoken by a human being. 2 : a written or printed letter or letters standing for a spoken word. 3 : a brief remark or conversation I’d like a word with you.

How did words become words?

English words come from several different sources. They develop naturally over the course of centuries from ancestral languages, they are also borrowed from other languages, and we create many of them by various means of word formation.

What was the first human word?

Mother, bark and spit are some of the oldest known words, say researchers. Continue reading → Mother, bark and spit are just three of 23 words that researchers believe date back 15,000 years, making them the oldest known words.

Who created English?

Anglo-Saxon

English is a West Germanic language that originated from Anglo-Frisian dialects brought to Britain in the mid 5th to 7th centuries AD by Anglo-Saxon migrants from what is now northwest Germany, southern Denmark and the Netherlands.

What are the 23 oldest words?

Science Says These are the Oldest 23 Words in the English…

- Thou. The singular form of “you,” this is the only word that all seven language families share in some form.

- I. Similarly, you’d need to talk about yourself.

- Mother.

- Give.

- Bark.

- Black.

- Fire.

- Ashes.

Who created MS Office?

Microsoft also maintains mobile apps for Android and iOS.

Microsoft Office.

| Microsoft Office for Mobile apps on Windows 10 | |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Microsoft |

| Initial release | April 19, 2000 |

| Stable release | 16.0 / February 2020 |

| Operating system | Windows 10, Windows 10 Mobile, Windows Phone, iOS, iPadOS, Android, Chrome OS |

Who invented MS Excel?

The electronic spreadsheet was essentially invented in 1979 by software pioneer Dan Bricklin, who started up Software Arts with Bob Frankston and created VisiCalc. The technology took a huge next step in 1983 when Mitch Kapor’s Lotus Development Corp.

What came before Microsoft Word?

While there were earlier word processors, Electric Pencil, WordStar was for many of us the first word processor we could use on a general purpose PC. It was also the first popular What You See is What You Get (WYSIWYG) word processor.

Is word free on iPhone?

Microsoft Office Is Now Free for iPhones, iPads and Android

Office users will now be able to create and edit documents in Word, Excel and PowerPoint on iPhone, iPad and Android devices at no cost. Making full use of the apps previously required a subscription to Office 365, which starts at $70 per year.

Do I need Microsoft 365 to use Word?

The good news is if you don’t need the full suite of Microsoft 365 tools, you can access a number of its apps online for free — including Word, Excel, PowerPoint, OneDrive, Outlook, Calendar and Skype. Here’s how to get them: 1. Go to Office.com.

Does Windows 10 come with Word?

Windows 10 includes online versions of OneNote, Word, Excel and PowerPoint from Microsoft Office. The online programs often have their own apps as well, including apps for Android and Apple smartphones and tablets.

Is Demonsterized a word?

As for people I don’t love, Thomas sits Katie down, grabs her hands in a way that screams “I studied a lot of heartfelt speeches,” and begins his very rehearsed speech about how his character and integrity’s been “demonsterized.” NOT A WORD!

What is the longest word in English?

Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis

1 Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis (forty-five letters) is lung disease caused by the inhalation of silica or quartz dust.

Why do we say word?

‘Word’ in slang is a word one would use to indicate acknowledgement, approval, recognition or affirmation, of something somebody else just said.

Who invented talking?

Language started 1.5m years earlier than previously thought as scientists say Homo Erectus were first to talk.

What was the first word in English?

There was no first word. At various times in the 5th century, the Angles, Saxons, Jutes and other northern Europeans show up in what is now England. They’re speaking various North Sea Germanic dialects that might or might not have been mutually understandable.

Who created words?

The general consensus is that Sumerian was the first written language, developed in southern Mesopotamia around 3400 or 3500 BCE. At first, the Sumerians would make small tokens out of clay representing goods they were trading. Later, they began to write these symbols on clay tablets.

Who created the first word?

The word is of Hebrew origin(it is found in the 30th chapter of Exodus). Also according to Wiki answers,the first word ever uttered was “Aa,” which meant “Hey!” This was said by an australopithecine in Ethiopia more than a million years ago.

What is today’s word for the day?

Definition of burble | Dictionary.com Today’s Word of the Day is eyesome.

What is the oldest word in the world?

According to a 2009 study by researchers at Reading University, the oldest words in the English language include “I“, “we“, “who“, “two” and “three“, all of which date back tens of thousands of years.

What is the oldest country?

By many accounts, the Republic of San Marino, one of the world’s smallest countries, is also the world’s oldest country. The tiny country that is completely landlocked by Italy was founded on September 3rd in the year 301 BCE.

What is the most dangerous country in the world?

MOST DANGEROUS COUNTRIES IN THE WORLD

- Central African Republic.

- Iraq.

- Libya.

- Mali.

- Somalia.

- South Sudan.

- Syria.

- Yemen.

Which culture is oldest in the world?

Sumerian civilization

Who is the poorest person in the world?

Jerome Kerviel

Who is the richest black person?

Here are the richest African Americans and where they rank on the list of the world’s billionaires.

- Robert F. Smith.

- David Steward. Net worth: $3.7 billion.

- Oprah Winfrey. Net worth: $2.7 billion.

- Kanye West. Net Worth: $1.8 billion.

- Michael Jordan. Net Worth: $1.6 billion.

- Jay-Z. Net Worth: $1.4 billion.

- Tyler Perry.

Who is a zillionaire?

: an immeasurably wealthy person.

Who is the richest YouTuber?

Jeffree Star

How much money does Pewdiepie have 2020?

Estimates of PewDiePie’s Net Worth

| Net Worth: | $30-$50 Million |

|---|---|

| Age: | 30 |

| First Name: | Felix Arvid Ulf |

| Last Name: | Kjellberg |

| Born: | October 24, 1989 |

Who is the youngest richest YouTuber?

Well, one child in particular – Forbes has published its annual listing of the top earners on YouTube, which, once again, is lead by Ryan Kaji, of the ever-popular channel ‘Ryan’s World’, who is now only 9 years of age.

How tall is Mr Beast?

6 feet and 3 inches

Who is the richest YouTuber in the World 2020?

Ryan Kaji

Does MrBeast have a girlfriend?

Maddy Spidell, (born: March 31, 2000 (2000-03-31) [age 21]) is the girlfriend of MrBeast. They have been dating since June 2019, when they met through Twitter.

How tall is Chris the meme God?

5 feet 10 inches

Who is Karl from Mr Beast?

Karl Jacobs

What is the age of Mr Beast?

23 years (May 7, 1998)

How tall is Pewdiepie?

1.80 m

How tall is Elsa?

5’7″

How tall is really tall?

The height average for men in US, Canada, UK and other countries is 5′9 1/2″. Anyone who is 6′ and above is considered tall. Since you are 6′ 3 1/2″ tall, you are certainly considered tall.

How tall is 6ix9ine inches in feet?

Quick Bio

| Full Name | Daniel Hernandez |

|---|---|

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Height | 5ft 5 ( in feet and inches) 165 cm (in centimeters) 1.65 m ( in meters) |

| Weight | In kilograms- 64 kg In pounds- 141 lbs |

| Famous For | Several tattoos of 69 on his body |

This article is about the unit of speech and writing. For the computer software, see Microsoft Word. For other uses, see Word (disambiguation).

Codex Claromontanus in Latin. The practice of separating words with spaces was not universal when this manuscript was written.

A word is a basic element of language that carries an objective or practical meaning, can be used on its own, and is uninterruptible.[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.[3]: 13:618 Some specific definitions of the term «word» are employed to convey its different meanings at different levels of description, for example based on phonological, grammatical or orthographic basis. Others suggest that the concept is simply a convention used in everyday situations.[4]: 6

The concept of «word» is distinguished from that of a morpheme, which is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning, even if it cannot stand on its own.[1] Words are made out of at least one morpheme. Morphemes can also be joined to create other words in a process of morphological derivation.[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as «rock», «god», «type», «writ», «can», «not») and possibly some affixes («-s», «un-«, «-ly», «-ness»). Words with more than one root («[type][writ]er», «[cow][boy]s», «[tele][graph]ically») are called compound words. In turn, words are combined to form other elements of language, such as phrases («a red rock», «put up with»), clauses («I threw a rock»), and sentences («I threw a rock, but missed»).

In many languages, the notion of what constitutes a «word» may be learned as part of learning the writing system.[5] This is the case for the English language, and for most languages that are written with alphabets derived from the ancient Latin or Greek alphabets. In English orthography, the letter sequences «rock», «god», «write», «with», «the», and «not» are considered to be single-morpheme words, whereas «rocks», «ungodliness», «typewriter», and «cannot» are words composed of two or more morphemes («rock»+»s», «un»+»god»+»li»+»ness», «type»+»writ»+»er», and «can»+»not»).

Definitions and meanings

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.[5] However, no satisfying definition has yet been found to apply to all languages and at all levels of linguistic analysis. It is, however, possible to find consistent definitions of «word» at different levels of description.[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.[2]: 1285

In some languages, these different types of words coincide and one can analyze, for example, a «phonological word» as essentially the same as «grammatical word». However, in other languages they may correspond to elements of different size.[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars. Some of the criteria for «word» developed can only be applicable to languages of broadly European synthetic structure.[4]: 1-3 Because of this unclear status, some linguists propose avoiding the term «word» altogether, instead focusing on better defined terms such as morphemes.[6]

Dictionaries categorize a language’s lexicon into individually listed forms called lemmas. These can be taken as an indication of what constitutes a «word» in the opinion of the writers of that language. This written form of a word constitutes a lexeme.[2]: 670-671 The most appropriate means of measuring the length of a word is by counting its syllables or morphemes.[7] When a word has multiple definitions or multiple senses, it may result in confusion in a debate or discussion.[8]

Phonology

One distinguishable meaning of the term «word» can be defined on phonological grounds. It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules. In Walmatjari, an Australian language, roots or suffixes may have only one syllable but a phonologic word must have at least two syllables. A disyllabic verb root may take a zero suffix, e.g. luwa-ø ‘hit!’, but a monosyllabic root must take a suffix, e.g. ya-nta ‘go!’, thus conforming to a segmental pattern of Walmatjari words. In the Pitjantjatjara dialect of the Wati language, another language form Australia, a word-medial syllable can end with a consonant but a word-final syllable must end with a vowel.[4]: 14

In most languages, stress may serve a criterion for a phonological word. In languages with a fixed stress, it is possible to ascertain word boundaries from its location. Although it is impossible to predict word boundaries from stress alone in languages with phonemic stress, there will be just one syllable with primary stress per word, which allows for determining the total number of words in an utterance.[4]: 16

Many phonological rules operate only within a phonological word or specifically across word boundaries. In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word. Conversely, external sandhi rules act across word boundaries. The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.[4]: 17

It is often the case that a phonological word does not correspond to our intuitive conception of a word. The Finnish compound word pääkaupunki ‘capital’ is phonologically two words (pää ‘head’ and kaupunki ‘city’) because it does not conform to Finnish patterns of vowel harmony within words. Conversely, a single phonological word may be made up of more than one syntactical elements, such as in the English phrase I’ll come, where I’ll forms one phonological word.[3]: 13:618

Lexemes

A word can be thought of as an item in a speaker’s internal lexicon; this is called a lexeme. Nevertheless, it is considered different from a word used in everyday speech, since it is assumed to also include inflected forms. Therefore, the lexeme teapot refers to the singular teapot as well as the plural, teapots. There is also the question to what extent should inflected or compounded words be included in a lexeme, especially in agglutinative languages. For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev or plural evler. However, it is not clear if it should also encompass the word evlerinizden ‘from your houses’, formed through regular suffixation. There are also lexemes such as «black and white» or «do-it-yourself», which, although consist of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.[3]: 13:618

Grammar

Grammatical words are proposed to consist of a number of grammatical elements which occur together (not in separate places within a clause) in a fixed order and have a set meaning. However, there are exceptions to all of these criteria.[4]: 19

Single grammatical words have a fixed internal structure; when the structure is changed, the meaning of the word also changes. In Dyirbal, which can use many derivational affixes with its nouns, there are the dual suffix -jarran and the suffix -gabun meaning «another». With the noun yibi they can be arranged into yibi-jarran-gabun («another two women») or yibi-gabun-jarran («two other women») but changing the suffix order also changes their meaning. Speakers of a language also usually associate a specific meaning with a word and not a single morpheme. For example, when asked to talk about untruthfulness they rarely focus on the meaning of morphemes such as -th or -ness.[4]: 19-20

Semantics

Leonard Bloomfield introduced the concept of «Minimal Free Forms» in 1928. Words are thought of as the smallest meaningful unit of speech that can stand by themselves.[9]: 11 This correlates phonemes (units of sound) to lexemes (units of meaning). However, some written words are not minimal free forms as they make no sense by themselves (for example, the and of).[10]: 77 Some semanticists have put forward a theory of so-called semantic primitives or semantic primes, indefinable words representing fundamental concepts that are intuitively meaningful. According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.[11][12]

Features

In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as «bundles» of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.[13]: 36–37 For example, the word «koalas» has semantic features (it denotes real-world objects, koalas), category features (it is a noun), number features (it is plural and must agree with verbs, pronouns, and demonstratives in its domain), phonological features (it is pronounced a certain way), etc.

Orthography

Words made out of letters, divided by spaces

In languages with a literary tradition, the question of what is considered a single word is influenced by orthography. Word separators, typically spaces and punctuation marks are common in modern orthography of languages using alphabetic scripts, but these are a relatively modern development in the history of writing. In character encoding, word segmentation depends on which characters are defined as word dividers. In English orthography, compound expressions may contain spaces. For example, ice cream, air raid shelter and get up each are generally considered to consist of more than one word (as each of the components are free forms, with the possible exception of get), and so is no one, but the similarly compounded someone and nobody are considered single words.

Sometimes, languages which are close grammatically will consider the same order of words in different ways. For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver («to wash oneself»), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g. lavarse.[a]

Not all languages delimit words expressly. Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically. However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries. This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility. Vietnamese orthography, although using the Latin alphabet, delimits monosyllabic morphemes rather than words.

Word boundaries

The task of defining what constitutes a «word» involves determining where one word ends and another word begins, that is identifying word boundaries. There are several ways to determine where the word boundaries of spoken language should be placed:[5]

- Potential pause: A speaker is told to repeat a given sentence slowly, allowing for pauses. The speaker will tend to insert pauses at the word boundaries. However, this method is not foolproof: the speaker could easily break up polysyllabic words, or fail to separate two or more closely linked words (e.g. «to a» in «He went to a house»).

- Indivisibility: A speaker is told to say a sentence out loud, and then is told to say the sentence again with extra words added to it. Thus, I have lived in this village for ten years might become My family and I have lived in this little village for about ten or so years. These extra words will tend to be added in the word boundaries of the original sentence. However, some languages have infixes, which are put inside a word. Similarly, some have separable affixes: in the German sentence «Ich komme gut zu Hause an«, the verb ankommen is separated.

- Phonetic boundaries: Some languages have particular rules of pronunciation that make it easy to spot where a word boundary should be. For example, in a language that regularly stresses the last syllable of a word, a word boundary is likely to fall after each stressed syllable. Another example can be seen in a language that has vowel harmony (like Turkish):[15]: 9 the vowels within a given word share the same quality, so a word boundary is likely to occur whenever the vowel quality changes. Nevertheless, not all languages have such convenient phonetic rules, and even those that do present the occasional exceptions.

- Orthographic boundaries: Word separators, such as spaces and punctuation marks can be used to distinguish single words. However, this depends on a specific language. East-asian writing systems often do not separate their characters. This is the case with Chinese, Japanese writing, which use logographic characters, as well as Thai and Lao, which are abugidas.

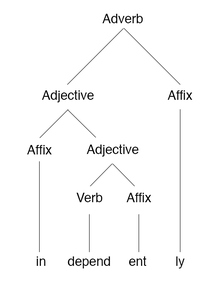

Morphology

A morphology tree of the English word «independently»

Morphology is the study of word formation and structure. Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection. Derivation is a process in which a new word is created from existing ones, often with a change of meaning. For example, in English the verb to convert may be modified into the noun a convert through stress shift and into the adjective convertible through affixation. Inflection adds grammatical information to a word, such as indicating case, tense, or gender.[14]: 73

In synthetic languages, a single word stem (for example, love) may inflect to have a number of different forms (for example, loves, loving, and loved). However, for some purposes these are not usually considered to be different words, but rather different forms of the same word. In these languages, words may be considered to be constructed from a number of morphemes.

In Indo-European languages in particular, the morphemes distinguished are:

- The root.

- Optional suffixes.

- A inflectional suffix.

Thus, the Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dhom would be analyzed as consisting of

- *wr̥-, the zero grade of the root *wer-.

- A root-extension *-dh- (diachronically a suffix), resulting in a complex root *wr̥dh-.

- The thematic suffix *-o-.

- The neuter gender nominative or accusative singular suffix *-m.

Philosophy

Philosophers have found words to be objects of fascination since at least the 5th century BC, with the foundation of the philosophy of language. Plato analyzed words in terms of their origins and the sounds making them up, concluding that there was some connection between sound and meaning, though words change a great deal over time. John Locke wrote that the use of words «is to be sensible marks of ideas», though they are chosen «not by any natural connexion that there is between particular articulate sounds and certain ideas, for then there would be but one language amongst all men; but by a voluntary imposition, whereby such a word is made arbitrarily the mark of such an idea».[16] Wittgenstein’s thought transitioned from a word as representation of meaning to «the meaning of a word is its use in the language.»[17]

Classes

Each word belongs to a category, based on shared grammatical properties. Typically, a language’s lexicon may be classified into several such groups of words. The total number of categories as well as their types are not universal and vary among languages. For example, English has a group of words called articles, such as the (the definite article) or a (the indefinite article), which mark definiteness or identifiability. This class is not present in Japanese, which depends on context to indicate this difference. On the other hand, Japanese has a class of words called particles which are used to mark noun phrases according to their grammatical function or thematic relation, which English marks using word order or prosody.[18]: 21–24

It is not clear if any categories other than interjection are universal parts of human language. The basic bipartite division that is ubiquitous in natural languages is that of nouns vs verbs. However, in some Wakashan and Salish languages, all content words may be understood as verbal in nature. In Lushootseed, a Salish language, all words with ‘noun-like’ meanings can be used predicatively, where they function like verb. For example, the word sbiaw can be understood as ‘(is a) coyote’ rather than simply ‘coyote’.[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs. Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.[3]: 13:631

The current classification of words into classes is based on the work of Dionysius Thrax, who, in the 1st century BC, distinguished eight categories of Ancient Greek words: noun, verb, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, and conjunction. Later Latin authors, Apollonius Dyscolus and Priscian, applied his framework to their own language; since Latin has no articles, they replaced this class with interjection. Adjectives (‘happy’), quantifiers (‘few’), and numerals (‘eleven’) were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek. They were recognized as distinct categories only when scholars started studying later European languages.[3]: 13:629

In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word. Some words can be controversial, such as slang in formal contexts; misnomers, due to them not meaning what they would imply; or polysemous words, due to the potential confusion between their various senses.[20]

History

In ancient Greek and Roman grammatical tradition, the word was the basic unit of analysis. Different grammatical forms of a given lexeme were studied; however, there was no attempt to decompose them into morphemes. [21]: 70 This may have been the result of the synthetic nature of these languages, where the internal structure of words may be harder to decode than in analytic languages. There was also no concept of different kinds of words, such as grammatical or phonological – the word was considered a unitary construct.[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.[21]: 70

See also

- Longest words

- Utterance

- Word (computer architecture)

- Word count, the number of words in a document or passage of text

- Wording

- Etymology

Notes

- ^ The convention also depends on the tense or mood—the examples given here are in the infinitive, whereas French imperatives, for example, are hyphenated, e.g. lavez-vous, whereas the Spanish present tense is completely separate, e.g. me lavo.

References

- ^ a b Brown, E. K. (2013). The Cambridge dictionary of linguistics. J. E. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-521-76675-3. OCLC 801681536.

- ^ a b c d Bussmann, Hadumod (1998). Routledge dictionary of language and linguistics. Gregory Trauth, Kerstin Kazzazi. London: Routledge. p. 1285. ISBN 0-415-02225-8. OCLC 41252822.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Keith (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: V1-14. Keith Brown (2nd ed.). ISBN 1-322-06910-7. OCLC 1097103078.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Word: a cross-linguistic typology. Robert M. W. Dixon, A. Y. Aikhenvald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-511-06149-8. OCLC 57123416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Haspelmath, Martin (2011). «The indeterminacy of word segmentation and the nature of morphology and syntax». Folia Linguistica. 45 (1). doi:10.1515/flin.2011.002. ISSN 0165-4004. S2CID 62789916.

- ^ Harris, Zellig S. (1946). «From morpheme to utterance». Language. 22 (3): 161–183. doi:10.2307/410205. JSTOR 410205.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of the word. John R. Taylor (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-175669-6. OCLC 945582776.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chodorow, Martin S.; Byrd, Roy J.; Heidorn, George E. (1985). «Extracting semantic hierarchies from a large on-line dictionary». Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics. Chicago, Illinois: Association for Computational Linguistics: 299–304. doi:10.3115/981210.981247. S2CID 657749.

- ^ Katamba, Francis (2005). English words: structure, history, usage (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29892-X. OCLC 54001244.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Hardman, Frank; Stevens, David; Williamson, John (2003-09-02). Meeting the Standards in Secondary English (1st ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203165553. ISBN 978-1-134-56851-2.

- ^ Wierzbicka, Anna (1996). Semantics : primes and universals. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870002-4. OCLC 33012927.

- ^ «The search for the shared semantic core of all languages.». Meaning and universal grammar. Volume II: theory and empirical findings. Cliff Goddard, Anna Wierzbicka. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 2002. ISBN 1-58811-264-0. OCLC 752499720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: a minimalist approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924370-0. OCLC 50768042.

- ^ a b An introduction to language and linguistics. Ralph W. Fasold, Jeff Connor-Linton. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84768-1. OCLC 62532880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bauer, Laurie (1983). English word-formation. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]. ISBN 0-521-24167-7. OCLC 8728300.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). «Chapter II: Of the Signification of Words». An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Vol. III (1st ed.). London: Thomas Basset.

- ^ Biletzki, Anar; Matar, Anat (2021). Ludwig Wittgenstein. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Linguistics: an introduction to language and communication. Adrian Akmajian (6th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01375-8. OCLC 424454992.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Beck, David (2013-08-29), Rijkhoff, Jan; van Lier, Eva (eds.), «Unidirectional flexibility and the noun–verb distinction in Lushootseed», Flexible Word Classes, Oxford University Press, pp. 185–220, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0007, ISBN 978-0-19-966844-1, retrieved 2022-08-25

- ^ De Soto, Clinton B.; Hamilton, Margaret M.; Taylor, Ralph B. (December 1985). «Words, People, and Implicit Personality Theory». Social Cognition. 3 (4): 369–382. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.4.369. ISSN 0278-016X.

- ^ a b Robins, R. H. (1997). A short history of linguistics (4th ed.). London. ISBN 0-582-24994-5. OCLC 35178602.

Bibliography

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Words.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Word.

Look up word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Barton, David (1994). Literacy: an introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 96. ISBN 0-631-19089-9. OCLC 28722223.

- The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. E. K. Brown, Anne Anderson (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1. OCLC 771916896.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge encyclopedia of the English language. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 31518847.

- Plag, Ingo (2003). Word-formation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-07843-9. OCLC 57545191.

- The Oxford English Dictionary. J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford University Press (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Here’s a trick question: who’s produced the most books in the past 30 years? Answer: a guy called Charles Simonyi. Eh? Well, I said it was a trick question. Mr Simonyi, you see, is the chap who created Microsoft Word, which is the word-processing program used by perhaps 95% of all writers currently extant, and although Simonyi didn’t actually write any books himself, the tool he made has definitely affected the ways texts are created. As Marshall McLuhan was fond of saying, we shape our tools and afterwards they shape us.

I write with feeling on the matter. When I started in journalism, I wrote on a manual typewriter. After I’d composed a paragraph, I would look at it, scribble between the lines, cross out words, type some more before eventually tearing the page out of the machine and retyping the para on a fresh sheet. This would go on until my desk was engulfed in a rising tide of scrunched-up balls of paper.

So you can imagine my joy when Mr Simonyi’s program appeared. Suddenly, I could type away, backspace and delete and overwrite and revise as much as I liked. And no matter how much I hacked away at the draft, I always had a fresh-looking paragraph on which to build. The tide of scrunched-up paper sheets receded. And I could add formatting – italics, bold face type, justification, indentation and other features that began to mimic the appearance of «proper» printed text. Bliss!

And I was not alone. It turned out that millions of other writers and hacks were as disenchanted by the annoyances of typewriters as I was. So we went for Microsoft Word like ostriches go for brass doorknobs. And now everyone uses Word or one of its clones. We are all word processors now.

But we were – and remain – remarkably incurious about how our beloved new tool would shape the way we write. Consider first the name that the computer industry assigned to it: word processor. The obvious analogy is with the food processor, a motorised culinary device that reduces everything to undifferentiated mush. That may indeed have been the impact of Word et al on business communications, which have increasingly become assemblies of boilerplate cliches. But that’s not been the main impact of word processing on creative writing, which seems to me to be just as vibrant as it was in the age of the typewriter or the fountain pen.

But has word processing changed the way we write? There have been lots of inconclusive or unconvincing studies of how the technology has affected, say, the quality of student essays – how it facilitates plagiarism. The most interesting academic study I looked at found that writers using computers «spent more time on a first draft and less on finalising a text, pursued a more fragmentary writing process, tended to revise more extensively at the beginning of the writing process, attended more to lower linguistic levels [letter, word] and formal properties of the text, and did not normally undertake any systematic revision of their work before finishing».

My hunch is that using a word processor makes writing more like sculpting in clay. Because it’s so easy to revise, one begins by hacking out a rough draft which is then iteratively reshaped – cutting bits out here, adding bits there, gradually licking the thing into some kind of shape.

But that’s just my opinion. We need more scholarly research on the subject. Which is why it’s nice to see that an American academic, Professor Matthew Kirschenbaum of the University of Maryland, has taken up the challenge by embarking on a literary history of word processing. «The story of writing in the digital age,» he told the New York Times, «is every bit as messy as the ink-stained rags that would have littered Gutenberg’s print shop or the molten lead of the Linotype machine.»

No sooner had Professor Kirschenbaum embarked on his quest, though, than he was engulfed in a tide of molten lead. He tentatively fingered the horror writer Stephen King as the first major American writer to complete a work of fiction in 1983 using the new technology. The science fiction writer Jerry Pournelle, a columnist on the long-defunct computer magazine Byte, fulminated that Kirschenbaum «hasn’t bothered to talk to the people who were actually writing with computers in the 1979-1984 era».

Mr Pournelle went on to point out that he and his co-author, Larry Niven, had published a bestselling novel in 1982 which was written on a Z-80 computer that is now in the Smithsonian Museum. And they didn’t even use Microsoft Word.

-

#1

Does anyone have any idea of who created words?

-

#2

Humans, a very long time ago.

-

#3

And it looks like they still are.

-

#4

Does nobody have a clue who really did it?

-

#5

There isn’t even agreement on when or where, little alone who. Probably some Neanderthal (literally).

Human speech is estimated to have started somewhere between 65,000-100,000 years ago. Theories differ. There’s not even agreement on where to draw the line between words and sounds with meaning. There’s no definitive way to prove anything it was so long ago. Writing, on the other hand, is relatively new, having started only (roughly around 8,000-10,000 years ago).

One consistent feature of any language, is that it evolves. New words are constantly being invented, old words drop out of usage. Those words are created by the speakers of a given language (or sometimes borrowed from another language).

So I wasn’t joking when I said «humans» — assuming you don’t want to argue the difference between Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens.

-

#6

I thought someone would know but it looks like it is a mystery.

Tdol

Editor, UsingEnglish.com

-

#7

There are various theories about how language emerged, but the answer is that we do not know. Speech evolved long before writing, so there are no records, which makes the theories speculation. We can say where and when writing emerged, but the words already existed. All human societies, however,have language. The words they use are arbitrary- it’s simply a matter of a speech community agreeing to use a word for something. Some people suggest that language is innate- humans are born with the desire/need for it, and they then adapt to the words and grammar around them. This doesn’t explain why English speakers say table, and other languages use different words,but it could explain why we feel the need to name it.

-

#8

at least you guys are honest and won’t say lies to finish the question. I think drawing and vision is everyone’s language. Am I right?

-

#9

I think drawing and vision is everyone’s language. Am I right?

No. They say that music is an international language. At least music has the comparative advantage of making a sound.

-

#10

How does sound connect with understanding?

Tdol

Editor, UsingEnglish.com

-

#11

How does sound connect with understanding?

Again, it is arbitrary. Even onomatopoeia, where the sounds are supposed to reflect the meaning, are cultural- there are many different ways of describing common sounds like dogs barking or cockerels. We need sounds to convey meaning, but the sounds we use vary from language to language, and most of the time have little connection to the meaning we convey. We absorb the sounds others use and follow the patterns.

-

#12

Again, it is arbitrary. Even onomatopoeia, where the sounds are supposed to reflect the meaning, are cultural- there are many different ways of describing common sounds like dogs barking or cockerels. We need sounds to convey meaning, but the sounds we use vary from language to language, and most of the time have little connection to the meaning we convey. We absorb the sounds others use and follow the patterns.

I kinda disagree but maybe you are kinda right.

-

#13

Do some Google searches on animal sounds by language to see some incredibly interesting, as well as highly amusing, lists of how animal sounds vary by language. Most are fairly similar and/or logically different, with some exceptions — how the Japanese hear ‘boon boon’ as representative of a bee ‘buzz’ or ‘boo boo’ for a pig’s ‘oink’ is beyond me.

These differences seem like a fun thesis paper for somebody in an Applied Linguistics program. Either that, or the title of a good children’s book — «Old McDonald’s World Vacation».

-

#14

Do some Google searches on animal sounds by language to see some incredibly interesting, as well as highly amusing, lists of how animal sounds vary by language. Most are fairly similar and/or logically different, with some exceptions — how the Japanese hear ‘boon boon’ as representative of a bee ‘buzz’ or ‘boo boo’ for a pig’s ‘oink’ is beyond me.

These differences seem like a fun thesis paper for somebody in an Applied Linguistics program. Either that, or the title of a good children’s book — «Old McDonald’s World Vacation».

This is kinda interesting https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5oIew0m-3HU&feature=youtu.be.

-

#15

If nobody alive created the first words I really don’t understand why some people be correcting others or why there is unnecessary corrections.

-

#16

How could words not be created by someone who was alive? Do you think dead people created words?

As an aside, if I ever find out who created «kinda», I will hunt them down, dead or alive, and make them sorry.

-

#17

How could words not be created by someone who was alive? Do you think dead people created words?

As an aside, if I ever find out who created «kinda», I will hunt them down, dead or alive, and make them sorry.

I meant the first person who created the first words or the first language. Why is it bad to use «kinda»?

Last edited: Aug 15, 2015

-

#18

Last edited: Aug 15, 2015

Tdol

Editor, UsingEnglish.com

-

#19

The fact that a word is in the dictionaries does not mean that it is fine to use it in all contexts.

-

#20

The fact that a word is in the dictionaries does not mean that it is fine to use it in all contexts.

Are you saying ‘kinda’ isn’t fine or ‘kind of’ isn’t fine? and Why isn’t it fine?

Last Update: Jan 03, 2023

This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested!

Asked by: Holden Wiza

Score: 4.8/5

(58 votes)

Eleven and twelve come from the Old English words endleofan and twelf, which can be traced back further to a time when they were ain+lif and twa+lif.

Who created the word dozen?

The English word dozen comes from the old form douzaine, a French word meaning «a group of twelve» («Assemblage de choses de même nature au nombre de douze» (translation: A group of twelve things of the same nature), as defined in the eighth edition of the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française).

Why is it called eleven and twelve?

numeral systems

Thus, eleven comes from Old English endleofan, literally meaning “[ten and] one left [over],” and twelve from twelf, meaning “two left”; the endings -teen and -ty both refer to ten, and hundred comes originally from a pre-Greek term meaning “ten times [ten].”

Why is 12 the perfect number?

Twelve is a sublime number, a number that has a perfect number of divisors, and the sum of its divisors is also a perfect number. Since there is a subset of 12’s proper divisors that add up to 12 (all of them but with 4 excluded), 12 is a semiperfect number. … Twelve is also the kissing number in three dimensions.

Is Twelveteen a number?

Numeral. (nonstandard) twelve.

26 related questions found

Are you a teenager at 12?

A teenager, or teen, is someone who is between 13 and 19 years old. They are called teenagers because their age number ends with «teen». The word «teenager» is often associated with adolescence. … A person begins their teenage life when they become 13 years old, and ends when they become 20 years old.

Is 12 considered a child?

Legally, the term child may refer to anyone below the age of majority or some other age limit. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child defines child as «a human being below the age of 18 years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier».

What does 12 mean in Bible?

The number 12 signifies perfection of government or rule. According to Bible scholars, 12 is the product of 3, which signifies the divine, and 4, which signifies the earthly. The heavenly bodies are also connected to the number 12 since the stars pass through the 12 signs of the zodiac in their heavenly procession.

Is 12 a holy number?

In many religions, such as the Greeks, the number 12 is considered holy and sacred for many generations. There are 12 main gods in Greek mythology, Odin had 12 sons in Norse mythology, 12 disicples of Christ in Christinaity, and 12 Imams in the Islam religion.

Why is fifteen not Fiveteen?

The correct spelling for the number 15 is fifteen, not fiveteen . The best way to remember the spelling of 15 is to use the word “fif,” and add “teen” thus “fifteen”. The funny thing about the spelling is this: five, fifteen, fifty are correct but Fiveteen is incorrect, that’s the nature of the English language.

Where does the word Twelve come from?

Eleven and twelve come from the Old English words endleofan and twelf, which can be traced back further to a time when they were ain+lif and twa+lif.

Why is it thirteen and not thirteen?

Thirteen comes from the Middle English thrittene. Through a process known as metathesis, where letters in a words a rearranged due to sound change we end up with thirteen. tene is a word element in Old English meaning «ten more than», so þreotene would be basically three + ten, i.e. thirteen.

What is the origin of a baker’s dozen?

Baker’s dozen means 13, instead of 12. The tale behind its origin is that a mediaeval law specified the weight of bread loaves, and any baker who supplied less to a customer was in for dire punishment. So bakers would include a thirteenth loaf with each dozen just to be safe.

When was the word dozen invented?

c. 1300, doseine, «collection of twelve things or units,» from Old French dozaine «a dozen, a number of twelve» in various usages, from doze (12c.) «twelve,» from Latin duodecim «twelve,» from duo «two» (from PIE root *dwo- «two») + decem «ten» (from PIE root *dekm- «ten»).

Why are things sold in dozens?

The English word «dozen» comes from the French word «douzaine» meaning a group of twelve. … By this time, the practice of selling eggs in dozens was commonplace and cartons started to be manufactured commercially that held twelve eggs. Nowadays, you can find 6-egg, 4-egg and even 2-egg cartons.

Why is twelfth spelled with an F?

The answer is yes. Middle English had the word “twelfte”, which was a cognate with Old Norse, Danish, Old Frisian, Dutch, among others. In Old English the “f” was there too, “twelfta” (derived from the number twelve, which was then “twelf”; «f» and «v» were allophones in Old English.

Is it twelfth or twelfth?

As adjectives the difference between twelveth and twelfth

is that twelveth is (archaic) twelfth while twelfth is (ordinal) the ordinal form of the number twelve, describing a person or thing in position number of a sequence.

How do you say 12 in words?

12 in words is written as Twelve.

What are the 12 stars in Revelation?

The Apocalypse of John describes «a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head.» Proponents of the Revelation 12 Sign say that the woman represents the constellation Virgo and the crown of twelve stars represents the nine stars of the constellation Leo in …

Who commissioned the 12 apostles?

Jesus went up on a mountainside and called to him those he wanted, and they came to him. He appointed twelve that they might be with him and that he might send them out to preach and to have authority to drive out demons.

What does 1212 mean in love?

The number 1212 is associated with a female being in isolation. This often means that you are at a time when you are ready to start a new relationship or want to take an existing one to a deeper level.

Can a 12 year old have a boyfriend?

«There is no law about when you are old enough to have a girlfriend or boyfriend, unlike the age of consent. You need to know your child well, because some children may be ready for a relationship at 12 but another not until they are 17.»

How tall is a 12 year old supposed to be?

While the average height of 12-year-olds is around 58 inches for boys and 59 inches for girls, it could be normal for your child to be quite a bit shorter or taller than average.

Why is my twelve year old so moody?

This behavior is actually a sign that he is growing up and forming his own identity, says Daniels. «It’s a good sign to show assertiveness and independence at age 12, as long as you are still seeing signs of a loving child,» Daniels says. At this stage, don’t pounce too strongly on every infraction, he says.

English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- vurd (Bermuda)

- worde (obsolete)

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /wɜːd/

- (General American) enPR: wûrd, IPA(key): /wɝd/

- Rhymes: -ɜː(ɹ)d

- Homophone: whirred (accents with the wine-whine merger)

Etymology 1[edit]

From Middle English word, from Old English word, from Proto-West Germanic *word, from Proto-Germanic *wurdą, from Proto-Indo-European *wr̥dʰh₁om. Doublet of verb and verve; further related to vrata.

Noun[edit]

word (countable and uncountable, plural words)

-

The smallest unit of language that has a particular meaning and can be expressed by itself; the smallest discrete, meaningful unit of language. (contrast morpheme.)

-

1897, Ouida, “The New Woman”, in An Altruist and Four Essays, page 239:

-

But every word, whether written or spoken, which urges the woman to antagonism against the man, every word which is written or spoken to try and make of her a hybrid, self-contained opponent of men, makes a rift in the lute to which the world looks for its sweetest music.

-

-

1986, David Barrat, Media Sociology, →ISBN, page 112:

-

The word, whether written or spoken, does not look like or sound like its meaning — it does not resemble its signified. We only connect the two because we have learnt the code — language. Without such knowledge, ‘Maggie’ would just be a meaningless pattern of shapes or sounds.

-

-

2009, Jack Fitzgerald, Viva La Evolucin, →ISBN, page 233:

-

Brian and Abby signed the word clothing, in which the thumbs brush down the chest as though something is hanging there. They both spoke the word clothing. Brian then signed the word for change, […]

-

-

2013 June 14, Sam Leith, “Where the profound meets the profane”, in The Guardian Weekly, volume 189, number 1, page 37:

-

Swearing doesn’t just mean what we now understand by «dirty words». It is entwined, in social and linguistic history, with the other sort of swearing: vows and oaths. Consider for a moment the origins of almost any word we have for bad language – «profanity», «curses», «oaths» and «swearing» itself.

-

- The smallest discrete unit of spoken language with a particular meaning, composed of one or more phonemes and one or more morphemes

-

1894, Alex. R. Mackwen, “The Samaritan Passover”, in Littell’s Living Age, volume 1, number 6:

-

Then all was silent save the voice of the high priest, whose words grew louder and louder, […]

-

-

1897 December (indicated as 1898), Winston Churchill, chapter IV, in The Celebrity: An Episode, New York, N.Y.: The Macmillan Company; London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd., →OCLC:

-

Mr. Cooke at once began a tirade against the residents of Asquith for permitting a sandy and generally disgraceful condition of the roads. So roundly did he vituperate the inn management in particular, and with such a loud flow of words, that I trembled lest he should be heard on the veranda.

-

- 2006 Feb. 17, Graham Linehan, The IT Crowd, Season 1, Episode 4:

- I can’t believe you want me back.

You’ve got Jen to thank for that. Her words the other day moved me deeply. Very deeply indeed.

Really? What did she say.

Like I remember! Point is it’s the effect of her words that’s important.

- I can’t believe you want me back.

-

- The smallest discrete unit of written language with a particular meaning, composed of one or more letters or symbols and one or more morphemes

-

c. 1599–1602 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Tragedie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, [Act II, scene ii]:

-

Polonius: What do you read, my lord?

Hamlet: Words, words, words.

-

-

2003, Jan Furman, Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon: A Casebook, →ISBN, page 194:

-

The name was a confused gift of love from her father, who could not read the word but picked it out of the Bible for its visual shape, […]

-

-

2009, Stanislas Dehaene, Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read, →ISBN:

-

Well-meaning academics even introduced spelling absurdities such as the “s” in the word “island,” a misguided Renaissance attempt to restore the etymology of the [unrelated] Latin word insula.

-

-

- A discrete, meaningful unit of language approved by an authority or native speaker (compare non-word).

-

1896, Israel Zangwill, Without Prejudice, page 21:

-

“Ain’t! How often am I to tell you ain’t ain’t a word?”

-

-

1999, Linda Greenlaw, The Hungry Ocean, Hyperion, page 11:

-

Fisherwoman isn’t even a word. It’s not in the dictionary.

-

-

-

- Something like such a unit of language:

- Hypernym: syntagma

- A sequence of letters, characters, or sounds, considered as a discrete entity, though it does not necessarily belong to a language or have a meaning

-

1974, Thinking Goes to School: Piaget’s Theory in Practice, →ISBN, page 183:

-

In still another variation, the nonsense word is presented and the teacher asks, «What sound was in the beginning of the word?» «In the middle?» and so on. The child should always respond with the phoneme; he should not use letter labels.

-

-

2003, How To Do Everything with Your Tablet PC, →ISBN, page 278:

-

I wrote a nonsense word, «umbalooie,» in the Input Panel’s Writing Pad. Input Panel converted it to «cembalos» and displayed it in the Text Preview pane.

-

-

2006, Scribal Habits and Theological Influences in the Apocalypse, →ISBN, page 141:

-

Here the scribe has dropped the με from καθημενος, thereby creating the nonsense word καθηνος.

-

-

2013, The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Language, →ISBN, page 91:

-

If M. V. has sustained impairment to a phonological output process common to reading and repetition, we might anticipate that her mispronunciations will partially reflect the underlying phonemic form of the nonsense word.

-

-

- (telegraphy) A unit of text equivalent to five characters and one space. [from 19th c.]

- (computing) A fixed-size group of bits handled as a unit by a machine and which can be stored in or retrieved from a typical register (so that it has the same size as such a register). [from 20th c.]

-

1997, John L. Hennessy; David A. Patterson, Computer Organization and Design, 2nd edition, San Francisco, California: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, Inc., §3.3, page 109:

-

The size of a register in the MIPS architecture is 32 bits; groups of 32 bits occur so frequently that they are given the name word in the MIPS architecture.

-

-

- (computer science) A finite string that is not a command or operator. [from 20th or 21st c.]

- (group theory) A group element, expressed as a product of group elements.

- The fact or act of speaking, as opposed to taking action. [from 9th c].

-

1811, Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility:

-

[…] she believed them still so very much attached to each other, that they could not be too sedulously divided in word and deed on every occasion.

-

-

2004 September 8, Richard Williams, The Guardian:

-

As they fell apart against Austria, England badly needed someone capable of leading by word and example.

-

-

- (now rare outside certain phrases) Something that someone said; a comment, utterance; speech. [from 10th c.]

-

1945 April 1, Sebastian Haffner, The Observer:

-

«The Kaiser laid down his arms at a quarter to twelve. In me, however, they have an opponent who ceases fighting only at five minutes past twelve,» said Hitler some time ago. He has never spoken a truer word.

-

-

2011, David Bellos, Is That a Fish in Your Ear?, Penguin_year_published=2012, page 126:

-

Despite appearances to the contrary […] dragomans stuck rigidly to their brief, which was not to translate the Sultan’s words, but his word.

-

-

2011, John Lehew (senior), The Encouragement of Peter, →ISBN, page 108:

-

In what sense is God’s Word living? No other word, whether written or spoken, has the power that the Bible has to change lives.

-

-

- (obsolete outside certain phrases) A watchword or rallying cry, a verbal signal (even when consisting of multiple words).

-

1592, William Shakespeare, Richard III:

-

Our ancient word of courage, fair Saint George, inspire us with the spleen of fiery dragons!

-

-

c. 1623, John Fletcher and William Rowley, The Maid in the Mill, published 1647, scene 3:

-

I have the word : sentinel, do thou stand; […]

-

-

- (obsolete) A proverb or motto.

-

1499, John Skelton, The Bowge of Court:

-

Among all other was wrytten in her trone / In golde letters, this worde, whiche I dyde rede: / Garder le fortune que est mauelz et bone.

-

-

1646, Joseph Hall, The Balm of Gilead:

-

The old word is, ‘What the eye views not, the heart rues not.’

-

-

- (uncountable) News; tidings [from 10th c.]

-

1945 August 17, George Orwell [pseudonym; Eric Arthur Blair], chapter 1, in Animal Farm […], London: Secker & Warburg, →OCLC:

-

Word had gone round during the day that old Major, the prize Middle White boar, had had a strange dream on the previous night and wished to communicate it to the other animals.

-

-

Have you had any word from John yet?

-

I’ve tried for weeks to get word, but I still don’t know where she is or if she’s all right.

-

- An order; a request or instruction; an expression of will. [from 10th c.]

-

He sent word that we should strike camp before winter.

-

Don’t fire till I give the word

-

Their mother’s word was law.

-

- A promise; an oath or guarantee. [from 10th c.]

-

I give you my word that I will be there on time.

- Synonym: promise

-

- A brief discussion or conversation. [from 15th c.]

-

Can I have a word with you?

-

- (meiosis) A minor reprimand.

-

I had a word with him about it.

-

- (in the plural) See words.

-

There had been words between him and the secretary about the outcome of the meeting.

-

- (theology, sometimes Word) Communication from God; the message of the Christian gospel; the Bible, Scripture. [from 10th c.]

-

Her parents had lived in Botswana, spreading the word among the tribespeople.

- Synonyms: word of God, Bible

-

- (theology, sometimes Word) Logos, Christ. [from 8th c.]

-

1526, [William Tyndale, transl.], The Newe Testamẽt […] (Tyndale Bible), [Worms, Germany: Peter Schöffer], →OCLC, John ]:

-

And that worde was made flesshe, and dwelt amonge vs, and we sawe the glory off yt, as the glory off the only begotten sonne off the father, which worde was full of grace, and verite.

-

- Synonyms: God, Logos

-

Usage notes[edit]

In English and other languages with a tradition of space-delimited writing, it is customary to treat «word» as referring to any sequence of characters delimited by spaces. However, this is not applicable to languages such as Chinese and Japanese, which are normally written without spaces, or to languages such as Vietnamese, which are written with spaces delimiting syllables.

In computing, the size (length) of a word, while being fixed in a particular machine or processor family design, can be different in different designs, for many reasons. See Word (computer architecture) for a full explanation.

Synonyms[edit]

- vocable; see also Thesaurus:word

Derived terms[edit]

- a-word

- action word

- afterword

- b-word

- babble word

- bad word

- bareword

- baseword

- breathe a word

- bug-word

- buzzword

- byword

- c-word

- catchword

- codeword

- compound predicate word

- compound word

- content word

- counterword

- crossword

- curse word

- cuss word

- d-word

- description word

- directed acyclic word graph

- dirty word

- doubleword

- dword

- Dyck word

- empty word

- f-word

- famous last words

- fighting word, fighting words

- five-dollar word

- foreword

- fossil word

- four-letter word

- frankenword

- from the word go

- function word

- g-word

- gainword

- get a word in edgeways, get a word in edgewise

- get the word out

- ghost word

- good as one’s word

- good word

- guideword

- h-word

- halfword

- hard word

- have a quiet word

- have a word

- have a word in someone’s ear

- have a word with oneself

- have words

- headword

- i-word

- in a word

- in so many words

- interword

- joey word

- k-word

- kangaroo word

- keyword

- l-word

- last word, last words

- last-wordism

- loaded word

- loanword

- longword

- Lyndon word

- m-word

- magic word

- measure word

- metaword

- mince words

- multi-word

- mum’s the word

- my word, oh my word

- n-word

- nameword

- non-word

- nonce word

- nonsense word

- octoword

- of one’s word

- one’s word is law

- operative word

- oword

- p-word

- partword

- pass one’s word

- password

- phoneword

- pillow word

- place word

- polyword

- portmanteau word

- power word

- procedure word, proword

- protoword

- purr word

- put in a good word

- put words in someone’s mouth

- quadword

- question word

- qword

- r-word

- reserved word

- root word

- s-word

- safeword

- say the word

- say word one

- semiword

- send word

- sight word

- single-word

- snarl word

- spelling word

- spoken word

- starword

- stop word

- subword

- swear word

- t-word

- take someone’s word for it

- ten-dollar word

- the word is go

- twenty-five cent word

- ur-word

- v-word

- vocabulary word

- vogue word

- w-word

- wake word

- war of words

- watchword

- weasel word

- wh-word

- winged word

- Wonderword

- word association

- word blindness

- word break

- word class

- word cloud

- word count

- word divider

- word for word

- word formation

- word game

- word golf

- word has it

- word is bond

- word ladder

- word method

- Word of Allah

- word of faith

- word of finger

- Word of God, word of God, God’s word

- word of honour

- word of mouth

- Word of Wisdom

- word on the street

- word order

- word problem

- word processing

- word processor

- word salad

- word search

- word space

- word square

- word to the wise

- word wrap

- word-blind

- word-final

- word-hoard

- word-initial

- word-lover

- word-perfect

- word-stock

- word-wheeling

- wordage

- wordbook

- wordbuilding

- wordcraft

- wordfast

- wordfinding

- wordflow

- wordform

- wordful

- wordhood

- wordie

- wording

- wordish

- wordlength

- wordless

- wordlike

- wordlist

- wordlore

- wordly

- wordmark

- wordmeal

- wordmonger

- wordness

- wordnet

- wordplay

- wordpool

- words fail someone

- words of one syllable

- wordscape

- wordshaping

- wordship

- wordsmith

- wordsome

- wordwise

- wordy

- workword

- wug word

Descendants[edit]

- Chinese Pidgin English: word, 𭉉

Translations[edit]

unit of language

- Abkhaz: ажәа (aẑʷa)

- Adyghe: гущыӏ (gʷuśəʼ)

- Afrikaans: woord (af)

- Albanian: fjalë (sq) f, llaf (sq) m

- Ambonese Malay: kata

- Amharic: ቃል (am) (ḳal)

- Arabic: كَلِمَة (ar) f (kalima)

- Egyptian Arabic: كلمة f (kilma)

- Hijazi Arabic: كلمة f (kilma)

- Aragonese: parola (an) f

- Aramaic:

- Hebrew: מלתא c (melthā, meltho)

- Syriac: ܡܠܬܐ c (melthā, meltho)

- Archi: чӏат (čʼat)

- Armenian: բառ (hy) (baṙ)

- Aromanian: zbor, cuvendã

- Assamese: শব্দ (xobdo)

- Asturian: pallabra (ast) f

- Avar: рагӏул (raʻul), рагӏи (raʻi)

- Azerbaijani: söz (az)

- Balinese: kruna

- Bashkir: һүҙ (hüð)

- Basque: hitz, berba

- Belarusian: сло́ва (be) n (slóva)

- Bengali: শব্দ (bn) (śobdo), লফজ (bn) (lôfzô)

- Bikol Central: kataga

- Breton: ger (br) m, gerioù (br) pl

- Bulgarian: ду́ма (bg) f (dúma), сло́во (bg) n (slóvo)

- Burmese: စကားလုံး (my) (ca.ka:lum:), ပုဒ် (my) (pud), ပဒ (my) (pa.da.)

- Buryat: үгэ (üge)

- Catalan: paraula (ca) f, mot (ca) m

- Cebuano: pulong

- Chamicuro: nachale

- Chechen: дош (doš)

- Cherokee: ᎧᏁᏨ (kanetsv)

- Chichewa: mawu

- Chickasaw: anompa

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 詞/词 (ci4)

- Dungan: цы (cɨ)

- Mandarin: 詞/词 (zh) (cí), 單詞/单词 (zh) (dāncí), 詞語/词语 (zh) (cíyǔ)

- Chukchi: вэтгав (vėtgav)

- Chuvash: сӑмах (sămah)

- Classical Nahuatl: tēntli, tlahtōlli

- Crimean Tatar: söz

- Czech: slovo (cs) n

- Danish: ord (da) n

- Dhivehi: ލަފުޒު (lafuzu)

- Drung: ka

- Dutch: woord (nl) n

- Dzongkha: ཚིག (tshig)

- Eastern Mari: мут (mut)

- Egyptian: (mdt)

- Elfdalian: uord n

- Erzya: вал (val)

- Esperanto: vorto (eo)

- Estonian: sõna (et)

- Even: төрэн (törən)

- Evenki: турэн (turən)

- Faroese: orð (fo) n

- Finnish: sana (fi)

- French: mot (fr) m

- Friulian: peraule f

- Ga: wiemɔ

- Galician: palabra (gl) f, verba f, pravoa f, parola (gl) f

- Georgian: სიტყვა (ka) (siṭq̇va)

- German: Wort (de) n

- Gothic: 𐍅𐌰𐌿𐍂𐌳 n (waurd)

- Greek: λέξη (el) f (léxi)

- Ancient: λόγος m (lógos), ῥῆμα n (rhêma), λέξις f (léxis), (Epic) ὄψ f (óps)

- Greenlandic: oqaaseq

- Guerrero Amuzgo: jñ’o

- Gujarati: શબ્દ (gu) m (śabd)

- Haitian Creole: mo

- Hausa: kalma

- Hawaiian: huaʻōlelo

- Hebrew: מילה מִלָּה (he) f (milá), דבר (he) m (davár) (Biblical)

- Higaonon: polong

- Hindi: शब्द (hi) m (śabd), बात (hi) f (bāt), लुग़त m (luġat), लफ़्ज़ m (lafz)

- Hittite: 𒈨𒈪𒅀𒀸 (memiyaš)

- Hungarian: szó (hu)

- Ibanag: kagi

- Icelandic: orð (is) n

- Ido: vorto (io)

- Ilocano: (literally) sao n

- Indonesian: kata (id)

- Ingrian: sana

- Ingush: дош (doš)

- Interlingua: parola (ia), vocabulo

- Irish: focal (ga) m

- Italian: parola (it) f, vocabolo (it) m, termine (it) m

- Japanese: 言葉 (ja) (ことば, kotoba), 単語 (ja) (たんご, tango), 語 (ja) (ご, go)

- Javanese:

- Carakan: ꦠꦼꦩ꧀ꦧꦸꦁ (jv) (tembung)

- Roman: tembung

- K’iche’: tzij

- Kabardian: псалъэ (psaalˢe)

- Kabyle: awal

- Kaingang: vĩ

- Kalmyk: үг (üg)

- Kannada: ಶಬ್ದ (kn) (śabda), ಪದ (kn) (pada)

- Kapampangan: kataya, salita, amanu

- Karachay-Balkar: сёз (söz)

- Karelian: sana

- Kashubian: słowò n

- Kazakh: сөз (kk) (söz)

- Khmer: ពាក្យ (km) (piək), ពាក្យសំដី (piək sɑmdəy)

- Korean: 말 (ko) (mal), 낱말 (ko) (nanmal), 단어(單語) (ko) (daneo), 마디 (ko) (madi)

- Kurdish:

- Central Kurdish: وشە (ckb) (wşe)

- Northern Kurdish: peyv (ku) f, bêje (ku) f, kelîme (ku) f

- Kyrgyz: сөз (ky) (söz)

- Ladin: parola f

- Ladino: palavra f, פﭏאבﬞרה (palavra), biervo m

- Lak: махъ (maq)

- Lao: ຄຳ (lo) (kham)

- Latgalian: vuords m

- Latin: verbum (la) n; vocābulum n, fātus m

- Latvian: vārds (lv) m

- Laz: ნენა (nena)

- Lezgi: гаф (gaf)

- Ligurian: paròlla f

- Lingala: nkómbó

- Lithuanian: žodis (lt) m

- Lombard: paròlla f

- Luxembourgish: Wuert (lb) n

- Lü: ᦅᧄ (kam)

- Macedonian: збор (mk) m (zbor), слово (mk) n (slovo) (archaic)

- Malay: kata (ms), perkataan (ms), kalimah (ms)

- Malayalam: വാക്ക് (ml) (vākkŭ), പദം (ml) (padaṃ), ശബ്ദം (ml) (śabdaṃ)

- Maltese: kelma f

- Maori: kupu (mi)

- Mara Chin: bie

- Marathi: शब्द (mr) m (śabda)

- Middle English: word

- Mingrelian: ზიტყვა (ziṭq̇va), სიტყვა (siṭq̇va)

- Moksha: вал (val)

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: үг (mn) (üg)

- Mongolian: ᠦᠭᠡ (üge)

- Moroccan Amazigh: ⴰⵡⴰⵍ (awal)

- Mòcheno: bourt n

- Nahuatl: tlahtolli (nah)

- Nanai: хэсэ

- Nauruan: dorer (na)

- Navajo: saad

- Nepali: शब्द (śabda)

- North Frisian:

- Föhr-Amrum: wurd n

- Helgoland: Wür n

- Mooring: uurd n

- Sylt: Uurt n

- Northern Sami: sátni

- Northern Yukaghir: аруу (aruu)

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: ord (no) n

- Nynorsk: ord (nn) n

- Occitan: mot (oc) m, paraula (oc) f

- Ojibwe: ikidowin

- Okinawan: くとぅば (kutuba)

- Old Church Slavonic:

- Cyrillic: слово n (slovo)

- Glagolitic: ⱄⰾⱁⰲⱁ n (slovo)

- Old East Slavic: слово n (slovo)

- Old English: word (ang) n

- Old Norse: orð n

- Oriya: ଶବ୍ଦ (or) (śôbdô)

- Oromo: jecha

- Ossetian: дзырд (ʒyrd), ныхас (nyxas)

- Pali: pada n

- Papiamentu: palabra f

- Pashto: لغت (ps) (luġat), کلمه (kalimâ)

- Persian: واژه (fa) (vâže), کلمه (fa) (kalame), لغت (fa) (loğat)

- Piedmontese: mòt m, vos f, paròla f

- Plautdietsch: Wuat (nds) n

- Polabian: slüvǘ n

- Polish: słowo (pl) n

- Portuguese: palavra (pt) f, vocábulo (pt) m

- Punjabi: ਸ਼ਬਦ (pa) (śabad)

- Romanian: cuvânt (ro) n, vorbă (ro) f

- Romansch: pled m, plaid m

- Russian: сло́во (ru) n (slóvo)

- Rusyn: сло́во n (slóvo)

- S’gaw Karen: တၢ်ကတိၤ (ta̱ ka toh̄)

- Samoan: ’upu

- Samogitian: žuodis m

- Sanskrit: शब्द (sa) m (śabda), पद (sa) n (pada), अक्षरा (sa) f (akṣarā)

- Santali: ᱨᱳᱲ (roṛ)

- Sardinian: fueddu

- Scots: wird, wurd

- Scottish Gaelic: facal m, briathar m

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: ре̑ч f, рије̑ч f, сло̏во n (obsolete)

- Roman: rȇč (sh) f, rijȇč (sh) f, slȍvo (sh) n (obsolete)

- Sicilian: palora (scn) f, parola (scn) f

- Sidamo: qaale

- Silesian: suowo n

- Sindhi: لَفظُ (sd) (lafẓu)

- Sinhalese: වචනය (si) (wacanaya)

- Skolt Sami: sääˊnn

- Slovak: slovo (sk) n

- Slovene: beseda (sl) f

- Somali: eray (so)

- Sorbian:

- Lower Sorbian: słowo n

- Upper Sorbian: słowo n

- Sotho: lentswe

- Southern Sami: baakoe

- Spanish: palabra (es) f, voz f, vocablo (es) m

- Sundanese: ᮊᮨᮎᮕ᮪ (kecap)

- Svan: please add this translation if you can

- Swahili: neno (sw)

- Swedish: ord (sv) n

- Tagalog: salita (tl)

- Tahitian: parau

- Tajik: вожа (tg) (voža), калима (tg) (kalima), луғат (tg) (luġat)

- Tamil: வார்த்தை (ta) (vārttai), சொல் (ta) (col)

- Tatar: сүз (tt) (süz)

- Telugu: పదము (te) (padamu), మాట (te) (māṭa)

- Tetum: liafuan

- Thai: คำ (th) (kam)

- Tibetan: ཚིག (tshig)

- Tigrinya: ቃል (ti) (ḳal)

- Tocharian B: reki

- Tofa: соот (soot)

- Tongan: lea

- Tswana: lefoko

- Tuareg: tăfert

- Turkish: sözcük (tr), kelime (tr)

- Turkmen: söz

- Tuvan: сөс (sös)

- Udmurt: кыл (kyl)

- Ugaritic: 𐎅𐎆𐎚 (hwt)

- Ukrainian: сло́во (uk) n (slóvo)

- Urdu: شبد m (śabd), بات f (bāt), کلمہ (ur) m, لغت (ur) m (luġat), لفظ (ur) m (lafz)

- Uyghur: سۆز (söz)

- Uzbek: soʻz (uz)

- Venetian: paroła f, paròła f, paròla f

- Vietnamese: từ (vi), lời (vi), nhời (vi), tiếng (vi)

- Volapük: vöd (vo)

- Walloon: mot (wa) m

- Waray-Waray: pulong

- Welsh: gair (cy)

- West Frisian: wurd (fy) n

- Western Cham: بۉه ڤنوۉئ

- White Hmong: lo lus

- Wolof: baat (wo)

- Xhosa: igama

- Yagnobi: гап (gap)

- Yakut: тыл (tıl)

- Yiddish: וואָרט (yi) n (vort)

- Yoruba: ó̩ró̩gbólóhùn kan, ọ̀rọ̀

- Yup’ik: qanruyun

- Zazaki: çeku c, kelime (diq) c, qıse (diq) m, qısa f

- Zhuang: cih

- Zulu: igama (zu) class 5/6, uhlamvu class 11/10

telegraphy: unit of text

- Finnish: sana (fi)

- Greek: λέξη (el) f (léxi)

- Maori: kupu (mi)

- Russian: сло́во (ru) n (slóvo)

- Telugu: సంకేత పదము (saṅkēta padamu)

computer science: finite string which is not a command or operator

- Finnish: sana (fi)

- Russian: сло́во (ru) n (slóvo)

fact or act of speaking, as opposed to taking action

- Finnish: sanat (fi) pl