libcats.org

Выбери правильное слово (Which word to use)

, Павлович Р.

Для того чтобы правильно выразить свою мысль на иностранном языке, часто важно правильно выбрать нужное слово из сходных по значению слов.

Данное пособие в доступной и занимательной форме поможет учащимся VI?VIII классов средней школы активно усвоить трудные случаи употребления лексики. Этому помогут занимательные тексты, диалоги, шутки, пересказ по серии картинок, разнообразные упражнения.

Популярные книги за неделю:

Только что пользователи скачали эти книги:

О книге

Добавлена в библиотеку 12.06.2012

пользователем Elleroth

Издание 1968 года

Размер fb2 файла: 3.79 MB

Объём: 164 страниц

4.64

Книгу просматривали 256 раз, оценку поставили 53 читателя

Аннотация

Скачать или читать онлайн книгу Выбери правильное слово (Which word to use)

На этой странице свободной электронной библиотеки fb2.top любой посетитель может

читать онлайн бесплатно полную версию книги «Выбери правильное слово (Which word to use)» или скачать fb2

файл книги на свой смартфон или компьютер и читать её с помощью любой

современной книжной читалки. Книга написана авторами Виктор Александрович Чижиков,

Галина Титовна Костенко,

Розалия Павловна Павлович,

относится к жанру Игры, упражнения для детей,

добавлена в библиотеку 12.06.2012 и доступна

полностью, абсолютно бесплатно и без регистрации.

С произведением «Выбери правильное слово (Which word to use)» , занимающим объем 164 печатных страниц,

вы наверняка проведете не один увлекательный вечер. В нашей онлайн

читалке предусмотрен ночной режим чтения, который отлично подойдет для тёмного

времени суток и чтения перед сном. Помимо этого, конечно же, можно читать

«Выбери правильное слово (Which word to use)» полностью в классическом режиме или же скачать всю книгу

целиком на свой смартфон в удобном формате fb2. Желаем увлекательного

чтения!

С этой книгой читают:

- В стране невыученных уроков

— Виктор Чижиков - В стране невыученных уроков

— Виктор Чижиков - Мужик и Медведь

— Виктор Чижиков - Площадь картонных часов

— Виктор Чижиков - Сундучок

— Виктор Чижиков - Физическое воспитание и развитие дошкольников

— Светлана Филиппова, Татьяна Волосникова, Октавий Каминский - 24 игры из тетради в клетку

— Виталий Медведь - Скала ужаса

— Дмитрий Тышевич - Генезис

— Рэй Гард - Тридцать миллионов слов. Развиваем мозг малыша, просто беседуя с ним

— Бет Саскинд, Лесли Левинтер-Саскинд, Дана Саскинд

To do well at school and in life, kids and adults need to know and to use lots of words.

The words we know and use – our vocabulary – has a big impact on our success at school and work. Vocabulary is one of the Big 5 skills we need to read well; and school failure is often caused by under-developed literacy and language skills (Duncan & Murnane, 2011, Murnane et al., 2012). Arguably, a good vocabulary is more important that ever in the digital/knowledge age.

But there are so many words to learn, and so little time:

- One research group estimates there are at least 520 million words in use in English (Corpus Contemporary American English, 2017).

- Another group cites more than 2 billion words out there to learn (Cambridge English Corpus, 2017)!

1. Choosing the right words to teach matters (a lot)

Teaching a child a new word does not automatically improve the child’s knowledge of, or ability to learn, other words (e.g. Elleman et al., 2009). To make things worse, some kids find it really hard to learn new words, for example:

- kids with developmental language disorders;

- kids learning English as a second (or third, or fourth) language (ESL); and

- kids growing up in poverty, in foster care, or kids at in or at risk of entering the youth justice system.

Kids with developmental language disorders may need to hear and use a word scores of times before they can be said to know the word well enough to use it in conversation. Learning new words for these kids takes lots of time and effort.

So which words should we teach kids to help them get the most out of school and their lives?

2. Some words are more useful than others

If you look at many educational products marketed to parents, teachers and speech pathologists, you’d think the most important words in the world are the names of farm animals, fruits and vegetables, forms of transport, colours and shapes; and concepts like “big”, “small”, “between”, “up”, and “after”. But how useful are these words in the real world? How often do adults talk or read about big, green frogs and little, purple grapes in general conversation? And don’t most kids – even kids with learning difficulties – pick up these easy to picture, high-frequency words from context at some point?

As kids move from Kindergarten to Year 12, the language used in books – including the words – becomes less easy to picture in their heads. Kids start with story-books about things they can see, hear, smell, touch and imagine moving: pigs and sheep and ducks and lions and trains and buses and trucks. But, by the end of school, kids are expected to read and understand histories, comedies, tragedies, poetry, philosophies, geographies, and treatises on maths and science. Books filled with:

- abstract ideas and concepts that can’t be understood with our senses alone; and

- words used in serious texts, but rarely if ever spoken in general conversation.

3. Kids (and adults) need school/academic/professional words

What kids really need for school and work success is an “academic vocabulary”: useful words that are used a lot in school books across different subjects, but not in general conversation (e.g. Baumann & Graves, 2010; Nagy & Townsend, 2012).

4. Where can I find an evidence-based list of academic words to teach?

Right here!

As a student speech pathologist, I struggled to find good words lists, and often ended up making my own – a time consuming process unsupported by evidence. But there are some great, free resources out there: if only I’d known where to look!

Way back in 2000, Dr Averil Coxhead published her “Academic Word List” (AWL). It’s used all over the world by teachers, speech pathologists, researchers, dictionary makers, people learning English as a second language, and website and app makers (Coxhead, 2016). The AWL contains 570 word families that make up about 10% of the total words used in academic texts outside the 2,000 most frequently used words in English. The full list can be accessed here.

In 2013, Professor Charles Browne published a “New Academic Word List”, which can be accessed here.

For those of you looking for a useful list of words to teach, here is a list of the most frequent words in the original AWL list:

analysis

approach

area

assessment

assume

authority

available

benefit

concept

consistent

constitutional

context

contract

create

data

definition

derived

distribution

economic

environment

established

estimate

evidence

export

factors

financial

formula

function

identified

income

indicate

individual

interpretation

involved

issues

labour

legal

legislation

major

method

occur

percent

period

policy

principle

procedure

process

required

research

response

role

section

sector

significant

similar

source

specific

structure

theory

variables

The words in bold are some of my personal favourites to teach school-aged kids. Why?

- Verbs/action words (e.g. “analyse” (from “analysis”), “research”, “assume” and “indicate”), are so important to language development generally, and are used a lot in exams.

- Words with Latin or Greek roots (e.g. “benefit”, “contract”, “specific”), can be used to help kids develop morphological awareness and general word-attack strategies for related words.

- Words like “procedure” and “evidence” are used in the school curriculum in lots of different contexts, and can help build links to lots of other words (so-called “semantic networks”) (e.g. Baumann et al., 2010).

- Words like “financial”, “legal”, “economic”, “theory”, “role”, “per cent” and “source” are highly useful words to know for people to participate meaningfully in society (and to avoid being exploited by others).

5. How should we teach academic words?

A mistake many educators and speech pathologists make is to teach words in lists, and/or to focus only on words’ definitions/meanings. This approach doesn’t tend to work well, especially for children with developmental language disorders.

At the single word level, we’ve talked about the “nuts and bolts” of how to teach new vocabulary before. Education and speech pathology research published over the last 20 years has improved our knowledge of how best to improve kids’ academic vocabularies. There’s even an acronym for it: “ALIAS”, which stands for “Academic Language Instruction for All Students”.

ALIAS principles to teach new words

When teaching students new words, we should:

- do it while reading real books and other works (e.g. in novels and non-fiction articles), rather than through lists (e.g. Stahl & Nagy, 2006);

- consciously choose “general purpose” academic words, like those listed above, rather than on basic words (like “car”) or specialised words used only in one context (like “photosynthesis”) (e.g. Lasaux et al., 2014);

- teach word knowledge deeply by looking at words from lots of different angles, including:

- different meanings of a word in different places, including general and specific meanings;

- how the word is pronounced (its “phonology“);

- how the word is spelled (its “orthography“);

- how the word is structured, including its prefixes, root, and suffixes (its “morphology“); and

- other words related to a word (e.g. Stahl & Nagy, 2006);

- focus on teaching kids strategies to help them learn the process of how to get new words – not just the words themselves (e.g. Baumann et al., 2003);

- give kids practice reading, writing, listening and saying the words (e.g. Beck et al., 2002);

- give kids multiple exposures to new words, spaced out over time (e.g. Lasaux et al., 2014); and

- emphasise interaction among students, with lots of opportunities for kids to work and talk together (Lesaux et al., 2014).

6. What does ALIAS/academic word teaching look like in practice?

In 2014, Professor Nonie Lesaux and colleagues published the results of their attempt to put the ALIAS principles into practice with more than 2,000 US-based Year 6 students from urban primary (‘middle’) schools (almost 1,500 were from an ESL background). The program:

- went for 20 weeks, featuring nine, 2-week units;

- units each consisted of a 9-day lesson cycle, and two 1-week review units;

- had 45-minute daily lessons;

- used short non-fiction articles featured in a kids’ magazine to teach the words;

- used articles that were appropriate for Year 6 readers and contained academic words like those listed above; and

- targeted 70 words, favouring academic words, but also some general words.

The researchers found that the program improved students’ vocabulary, morphological awareness, written expression and reading comprehension of texts that included the target words (but not reading comprehension generally), as well as overall oral language skills. Crucially, they found that the program had its most significant positive effects on students learning ESL and students who started the program with underdeveloped vocabulary – in other words, the students most at risk for academic failure.

The study had some limitations, including ceiling effects on some tests, and no measures of teacher buy-in or sustained use of strategies. But, overall, the study showed that ALIAS principles work in the “real world” to help school-aged kids learn, understand and use new academic words.

Clinical bottom line

Having a poorly-developed vocabulary increases a child’s risk of reading, school, and work failure. Teaching kids the right words – useful academic vocabulary – is crucial, especially for children at risk of academic failure. So, too, is teaching children new words in the right way.

Teachers, speech pathologists, and parents can access free, evidence-based available academic word lists to help choose the rights words. Kids learn new words best when teaching is based on the ALIAS principles (summarised above).

Free teacher/speech pathologist/parent resources

Free word lists

Word corpora

Cambridge English Corpus

Free to use resources built on or for Academic Word Lists

Sandra Haywood’s AWL Highlighter Tool

Principal sources:

(1) Lesaux, N.K., Kieffer, M. J., Kelley, J.G., & Harris, J.R. (2014). Effects of Academic Vocabulary Instruction for Linguistically Diverse Adolescents: Evidence from a Randomized Field Trial. American Educational Research Journal, 51(6), 1159-1194.

(2) Coxhead, H. (2016). Reflecting on Coxhead (2000), “A New Academic Word List”, TESOL Quarterly, 50(1), 181-185.

(3) Justice, L. (2017). Keynote address at the Speech Pathology Australia 2017 National Conference, Sydney, on 31 May 2017. (You can read more about Dr Justice’s fantastic work in literacy here.)

Image: http://tinyurl.com/ydykwpoc

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.

As a parent, you may have heard the term “sight words” but might not really know what it means. We read sight words every day without thinking about it. They are words like “the,” “he,” and “where,” for example, that are very common but not easy to sound out.

Learning sight words can boost your child’s reading skills and confidence. When you give your little one the resources they need to recognize sight words, they’ll be on the path to mastering — and enjoying — their reading journey!

In this article, we’ll talk about what sight words are and share some fun ways to use them to help kids learn to read.

Table of Contents

- What Are Sight Words?

- When Should Kids Learn Sight Words?

- Age-Appropriate Sight Words

- Fun And Easy Tips For Using Sight Words

- What To Do If Your Child Is Struggling

- Sight Words And Reading

- A Lifetime Of Reading

What Are Sight Words?

As we mentioned, sight words aren’t easy to sound out or decode, so we memorize them (or, in other words, recognize them by sight).

Once your child learns sight words, they won’t need to spend a lot of time trying to decipher these high-frequency words. This helps them improve their reading fluency and makes reading more fun.

After all, being able to quickly recognize sight words is one of the first steps to a lifetime of reading adventures!

Here are some examples of the simplest and most essential sight words:

- The

- Was

- Are

- Of

- To

- On

- Have

- What

- Said

As kids develop their reading skills, the list of words they recognize by sight will grow well beyond the one above. But giving them these words to start with can help boost their confidence and encourage them to learn more.

When Should Kids Learn Sight Words?

Most children — not all! — begin to master a few sight words (like is, it, my, me, and no) by the time they’re in Pre-K at four years old. Then, during kindergarten, children are introduced to anywhere from 20 to 50 sight words, adding to that number each year.

However, it’s important to mention that while some kids are ready for sight words before they turn four, others may not be ready until they’re five or older.

How can you tell if your child is ready to start memorizing sight words? Here are a few easy signs to watch for in your little one. They:

- Show an interest in books

- Recognize some or all letters

- Can hear the sounds in words (such as knowing when words rhyme)

- Express an eagerness to learn how to read

If your child isn’t quite there yet, that’s OK! Give the process — and your little one — time and grace. And remember that every child learns in their own way and in their own timing!

If you get started but your child seems a bit discouraged, consider trying some simple, yet fun, approaches to introducing sight words. Sight words hopscotch, memory games, and other similar activities are great ways to engage different learning styles.

Finally, if your little one still seems to be struggling, that’s OK, too! Their teacher can be a great resource offering ideas for tackling these special words.

Age-Appropriate Sight Words

Some sight words are more difficult than others, meaning different levels of sight words are appropriate for different ages.

To help you easily keep them straight, there are two common lists that break down which words are best to introduce at which age: The Dolch Word List (also called The Dolch 220) and The Fry Word List.

We recommend starting with The Dolch 220. Made up of the most commonly used words in the English language, this list is ideal for helping your four to eight-year-old develop a love for reading!

The Dolch Sight Words List

Edward William Dolch was a professor who wrote several children’s books with his wife. In the 1930s, he researched and discovered the 220 words that were most frequently used in the English language.

These words were given the title “Sight Words” and the list was born. Later, he compiled a list of the 95 most common nouns in English, bringing the number of sight words in his lists to 315.

To make it easy to choose which words to introduce based on a child’s age, the Dolch high-frequency word list is broken up into five groups: Pre-K (Pre-Primer), Kindergarten (Primer), First Grade, Second Grade, and Third Grade.

You can choose which group to start introducing to your child based on their grade level, or you can work with whichever one you feel they’re ready for. There are different ways to begin your child’s reading adventure!

For example, if your child is a kindergartener, according to the Dolch list, they might be ready to start learning some of these words:

- All

- Ride

- Saw

- There

- Four

- He

- Our

The Dolch Sight Words are often used in schools, so your child’s teacher will most likely provide a list of sight words to help you get started.

But if your child isn’t yet in school or you’re unsure where to start, our Learning Quiz is a great way to help identify your child’s reading stage! From there, investigate our games and practice menus in the HOMER Learn & Grow app for sight word games and activities for your child.

Fun And Easy Tips For Using Sight Words

Now that you know what sight words are and why they’re important, let’s dive into some specific tips to help you teach your child to read these words.

1) Ease Into The Adventure

Our first tip is to start slow. When introducing sight words, begin with three to five words and build from there. If your child seems a bit overwhelmed, you can always take it at their pace and reduce the number of words.

The goal is to help them learn a handful of sight words at a time. Start with a few words and, once your child can recognize these words on sight, try adding more!

For example, if they have a list of five words and have mastered three of them, try including three new ones so they’re still working on no more than five at a time.

2) Involve The Senses

Next, get as many of their senses involved as you can!

Giving your child the opportunity for fun, hands-on learning helps them connect their brain and body, which can reinforce what the word sounds and looks like.

When you introduce a word, write it on a bright note card and put it in a place where they can see it throughout the day so that when you pass by the word with your child, you can point it out to them.

Say the word often in your everyday conversations so they can hear it out loud, and have them write the word in sand or flour using their fingers so they can touch it.

You can also use shaving cream to make involving their sense of touch even more fun! To try this activity, simply spread some shaving cream thinly over a cookie tray and let your child write the word in it.

By letting your child interact with each word in various ways, you’ll help cement it into their brain. So break out the playdough and challenge them to build each letter and put them in order. Or pour some salt into a baking pan so they can write in it.

Have your child try to spell the word aloud while hopping on one foot. Then, see if they can spell it with their eyes closed.

Change things up and keep the activities light and fun to help your child master the words!

3) Try Silly Spelling

Humor can help kids remember things in a different way. So don’t be afraid to get your child giggling as you practice.

For this activity, say each word once, spell it, and then say it again. Then, have your child repeat what you just said back to you while looking at the word.

To make sure your child is connecting the sound of the word with the written word, give them a notecard to look at while the two of you spell and repeat the word.

To amp up the fun, get creative with it and use silly voices each time, encouraging your child to copy you. They will love having some fun, and you’ll love helping them learn sight words while going about your busy day!

4) Play A Word-Find Game

Finally, another great way to help your child become familiar with their sight words is by making a game of finding the words in a book.

To do this activity, choose one word to write on a card and let your child study it a bit. Once they’ve looked at it a while, challenge them to find it in a book. You may even have them find the same word five times in one book to see how useful sight words are.

This is an easy, fun, and effective way to help your child with sight words while going about your day because you can send them on a word hunt while you’re checking things off your to-do list!

Another way to incorporate this new word-finding skill into your day is to pause while you’re reading aloud whenever you come across a sight word that your child knows. Then, have them look at the word and read what it says.

This process helps them see what the word looks like in context. It also encourages young readers to listen and follow the story, which is an essential literacy skill.

Tip: Avoid doing this too often or it may turn what should be a fun read-aloud time into a chore for your child.

5) Sight Word Slap

Sight word games reinforce words. They encourage your child to practice what they’ve been learning in a way that doesn’t feel like work.

Here’s another fun game you can play. You’ll need a fly swatter, a marker, and a stack of index cards.

Before you play, write a single sight word on each card. Make sure to pick the ones your child is currently working on or has already mastered. This slapping game can be a fun way to review words your child already knows.

Spread the sight word cards out around the room, word side up. Then, call out one of the words. Have your child look for the card with that word on it. Once they find it, they hit it with the flyswatter, bring you the card, and read the word aloud.

If they misread a word, put it back out into the room and try it again later in the game. If they get it right, put the card in a stack.

Repeat this process until your child has successfully read all of the words.

6) Building Sight Words

If your child enjoys playing with building blocks, such as LEGOs or MEGA Bloks, they’ll enjoy this game.

Before you begin, gather a dry-erase marker, baby wipes to use as an eraser, and a stack of blocks. You’ll also need a list of sight words.

Pro Tip: While we’ve had good luck getting the marker off of MEGA Bloks with a baby wipe, you might want to test yours to ensure you have the same results. If not, you’ll probably want to skip this game. Or, you could put a piece of painter’s tape on each block and write on that instead.

Once you’ve tested, write a single letter on one side of each block with the dry-erase marker. Make sure you have enough of each letter to make the words on your list. You’ll likely need more than one of some letters.

When your blocks are ready, call your child over. Ask them to identify the letters on each block. This step is a quick way to practice letter identification and ensure that they can clearly see the letters.

To play, ask your child to spell one of the sight words from your list by using the letter blocks. Have them set the blocks side-by-side to spell the word. For example, if they’re trying to spell “away,” they’d need two “A” blocks, a “W,” and a “Y.”

Once they spell the word correctly, ask them to read it. Then, spread the blocks back out to use in the next round.

When you’ve practiced all of the words on your list, have your child help you erase the letters with the wipes.

7) Make Your Own Books

While the reading games above can help your child memorize sight words, they’re often reading the words out of context. This can make it challenging for your child to remember them when they see the sight words surrounded by other words in a sentence or on the page.

To help your child learn to read sight words in context, make little books together! This activity allows you to customize the words your child practices. For example, you can include their name, names of family members, and various other words they can read.

Enlist your young reader to help with the writing process. Start by talking about all of the words they can read now and asking them to brainstorm some sentences that combine those words.

Be their scribe and write each sentence on a separate piece of paper. After you’ve written the words, ask your child to illustrate the sentence. Remind them that pictures can add clues to help them read if they get stuck, so the illustrations should match the text.

Encourage your writer to keep thinking of sentences. When you have a few pages done, staple them together to make a book. Then, have your child read the book to you. After they practice a few times, have them share their project with someone else.

If you’re having trouble figuring out what to write, here are a few simple sentences that use sight words. Hopefully, they’ll give you a starting point:

- I see the big red ball.

- Do you like my new dress?

- He is funny.

- We looked at a dog.

- Can you play at my house?

- Mom is cooking dinner.

- Dad is reading a book.

At first, don’t worry about the story making sense. Remember that the goal here is to practice reading sight words. So if the pages don’t flow together to create a complete story, that’s OK!

What To Do If Your Child Is Struggling

Sometimes, no matter how hard you try to help your child learn sight words, they still have trouble reading the words. If this is the case, don’t worry! Just take a step back and reevaluate your approach.

Here are a few things you can try.

Change Your Routine

Reading practice can sometimes start to feel dull or mundane. If your child usually does well but is having a hard time lately, try switching things up a bit.

For example, if you usually practice sight words after lunch, try doing it first thing in the morning. Or if you typically sit down at the kitchen table to work on them, try standing up or doing a movement-centered game instead.

These simple changes might not seem important, but they can make a big difference to your child.

Re-Evaluate Your Child’s Readiness

Even if you think your child is old enough to read certain words, they might not be developmentally prepared. Review the list at the beginning of this post to see if your child is ready.

If they aren’t, work on phonemic awareness activities for a bit. Then, come back to sight words after their reading skills are a little more developed.

Use Different Words

Children go through different stages of reading development. Early readers often use the first and last letters of the word to provide clues. Then, they’ll try to guess based on that information. For example, if they see the word “dog,” they might read “dig,” ignoring the vowel in the middle.

As your child develops a better understanding of letters and sounds, they’ll apply that knowledge to their reading. Until then, it’s best to make sure the words you’re practicing don’t all look alike.

So if you’re working on the word “on,” don’t also practice “no.” These two words share the same letters and can confuse young readers.

Again, as your child develops reading skills, they’ll be able to tackle similar words better. But, for now, try to work on dissimilar ones.

Slow It Down

As mentioned above, you can’t be in a hurry when introducing sight words. But for some kids, two or three words a week can be too many. Try slowing down even more if the words don’t seem to stick in your child’s memory.

Pick one word to practice each week. Then, add a different one the next week. Often, simply changing the pace can be enough to help your child begin to master the words and gain confidence as a reader.

Use Tech

The HOMER Learn & Grow app has several games to help children practice essential sight words. Letting your child play for a little bit each day can help move the needle when it comes to reading.

Ask For Help

If you’ve tried all of the above and your child is still having trouble, it might be time to seek out some professional help.

A tutor or teacher can assess your child’s skills and give you tailored advice on how to best help them. They might also be able to recommend some great resources to help your child learn to read sight words.

Sight words are a great foundation for learning to read. As your child adds more sight words to their reading vocabulary, they’ll start to read with more speed and ease and, as a result, will begin to feel more confident.

Think of every sight word as a building block. When you stack the blocks, a firm foundation is set. Your child can then build on this base, adding more words, more skills in sounding out words, and more fluency. And their love of reading will grow along with their skills!

A Lifetime Of Reading

To sum up, sight words are common words recognized by sight rather than by sounding them out. You can start teaching sight words to your child as early as four years old, but the exact timing will depend on when your young learner is ready.

There are fun and simple ways to start working on sight words with your child at home. It doesn’t have to be boring! The sky’s the limit when it comes to how you can teach sight words to your beginning reader.

Learning sight words can even feel like play if you change things up every so often. If you’re looking for ideas, check out our kid-tested games and activities. And for more fun ideas on how to use sight words, take a look at 13 Highly Effective And Fun Sight Words Games To Help Your Kids Learn.

Whether your child is just starting to learn their letters or is already recognizing some sight words, we can help make learning to read fun! To encourage your child’s love of reading, HOMER uses their interests to curate stories just for them.

We have over 200 animated and interactive stories and songs for them to choose from. They can read along or read on their own for an experience that’s both fun and educational!

Reading wars, Whole word VS. Phonics, whole language advocates vs. phonetics enthusiasts…

Who would imagine that learning to read could be such a controversial topic?

But sadly, it is!

And I use the word SADLY for a good reason: Because the ones that normally pay the consequences of this disagreement are our children!

In this article we will look at the differences between the whole word approach and the phonics approach, so you can learn the ins and outs of this hot debate and form your own opinion.

If your child is learning to read, this is a crucial topic for you to understand as a parent. The reading success of your child can depend very much upon the actual approach used to teach your child to read; and, as you will discover on this article, schools do not always use the most effective method.

When it comes to teaching children to read there are two main teaching methods.

These two main methods are the whole word approach (also called the “sight words” approach) and the phonetic or phonics approach.

Some prefer the whole word method, while others use the phonics approach.

There are also educators that use a mix of different approaches.

But, who is right?

The Whole Word Approach

The whole word approach relies on what are called “sight words”. This method basically consists of getting children to memorize lists of words and teaching them various strategies of figuring out the text from a series of clues. Using the whole word approach, English is being taught as an ideographic language, such as Chinese or Japanese.

One of the biggest arguments of whole word advocates is that teaching to read using phonics breaks up the words into letters and syllables which have no actual meaning. Yet they fail to acknowledge that once the child is able to decode the word, they will be able to actually read that entire word, pronounce it and understand its meaning. So, in practicality, this is a very weak argument, from our point of view.

Unlike Chinese, English is an alphabet-based language. This means the letters of the English alphabet are not ideograms (also called ideographs), like Chinese characters are.

An ideogram (or ideograph) is a graphic symbol that represents an idea or a concept. Simply put, ideograms are like logos.

So, in a way, you could say that in the Chinese language you need to teach children to memorize “logos” and the meaning of each of them.

It is not logic to think that English should be taught using an ideographic approach…

So, the very popular reading programs that use a whole word approach simply get children to memorize words using different strategies, but without teaching any proper decoding methodology.

Think of the example we used before of the logos and the Chinese language.

Besides, there is no scientific evidence to suggest that teaching your child to using the whole word approach is an effective method. However, there are large numbers of studies which have consistently stated that teaching children to read using phonics and phonemic awareness is a highly effective method.

The Whole-Word Approach in Schools…

So, is your child learning to read using sight words? Or maybe a mixture of phonetics and sight words? What is the standard approach in our education system?

Well, every country – and even every educator / school – is different.

However, in English speaking countries in general -with the exception of the UK, which has been encouraging schools to adopt a systematic synthetic phonics approach since 2011- reading instruction is normally more heavily weighted towards the teaching of sight words, emphasizing the learning of “word shapes”.

Despite all the evidence to suggest otherwise, the whole word method of teaching still dominates how reading is taught at schools.

Why? Well, our guess is that children can appear to make fast progress with the whole language approach, and that makes everybody happy…

That is until their progress stalls, which is what usually happens, because with this method many children do not learn the relationships between letters and sounds correctly.

Some children can finally understand the letter-sound relationships from the words they have learned, but unfortunately many children aren’t able to figure this out. So, they are left with only one strategy for learning to read: memory and continuous repetition.

This is a very poor strategy these children are left with, in our opinion.

On the other hand, the reading ability of children is normally exaggerated on whole word programs as the texts used are very repetitive and extremely predictable. The children know what to expect. So… They are basically guessing!

When children are presented with a less predictable text without pictures, they struggle with words they had previously been able to figure out in a repetitive text with illustrations.

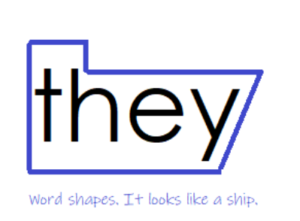

Another strategy used in whole word programs consists of focusing on word shapes.

Just have a look at this image. This is a “reading strategy” used on whole word programs.

Encouraging children to learn to read by looking at word shapes is completely madness! They are told to look at words as if they were “pictures”, focusing on the overhangs in the shapes of words! This does not apply for the English language!! Again, this is a method used for ideographic languages, such us Chinese or Japanese.

It does not make sense! There are just so many words with very similar shapes!

For example, look at this:

- hat vs. bat

- tree vs. free

- fall vs. tall vs hall

- hunt vs. hurt vs. hard

And the list goes on and on and on… Honestly, we could find thousands of words that have similar shape if we had the time to do this exercise!

The Whole- Word Method and Spelling

Even if a child has some early success learning to read using whole words programs, it gets him/her into the habit of ignoring the letters in words. This causes serious reading problems later on (when texts get more complicated), including spelling problems.

Another strategy that we are told to do on whole word programs is encouraging our children to look at the pictures in storybooks to “guess” or “predict” words.

-

Can they use the picture to help?

-

Can they look at the initial letter and predict what word would make sense that starts with that letter?

-

What word makes sense based on the context?

A little bit of history on the Whole-Word Approach

The main idea behind this theory is that if you see words enough number of times, you eventually store them in your memory as visual images.

They also embrace the idea that kids can naturally learn to read if they are exposed a lot of books.

Since the 1980s, these beliefs had strongly influenced the way children in North America and most English speaking countries are taught to read and write.

These ideas start to emerge in the 1970’s, and they become extremely popular for teaching reading in the 80’s and 90’s.

There is a strong focus on meaning, rather than sounds.

The Phonics Approach

At the opposite end of the spectrum, we find reading instruction based on phonemic awareness and phonics.

The phonics approach focuses on the sounds in words, which are represented by the letters (or groups of letters) in the alphabet.

There is a myriad of methods and systems within the phonics approach itself, but the the two main methodologies for teaching phonics are Synthetic and Analytic phonics.

Even though they both have the label “Phonics” attached to them, they are in fact quite different ways for teaching children to read.

However, for the sake of this article (and to keep things simple) we will just say that the main difference is that in the Synthetic Phonics approach skills are taught in a highly structured ‘systematic’ way.

Children start with very simple sounds and decoding regular words. Gradually, they are introduced to more complex sounds (such us letter combination sounds) and to irregularities and exceptions. Every step of the way is planned, and children only move to the next stage of phonics once they have mastered the previous one.

In the Analytic Phonics approach, reading instruction is less structured, and learning happens in a more ‘embedded’ fashion. Children are encouraged to analyze groups of whole words to identify similar sounds and letter patterns. Instruction relies a lot on the analysis of “families of words”.

For instance, the family of words ending up in -all, such us “tall, fall, mall, hall, small”, or the family of words ending up in -at, such “mat, cat, rat, bat, fat, pat”.

If you are interested in knowing more about the differences between analytics and synthetic phonics, you can check this video.ç

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/twDjIsFkhFM” title=”YouTube video player” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>

Is there a Winner in the Reading Wars?

What Research / Modern Science has to say…

The best way to put an end to this controversy and start making decisions that are RIGHT for our kids – and not based on personal preferences or ideology- is by looking at what research and scientific studies have to say.

However, you may think that if opinions on the topic are still so divided, then it must be that the results of these studies are somehow inconclusive.

Well, not really…

Look at these statements by the US National Reading

“Teaching children to manipulate phonemes in words was highly effective under a variety of teaching conditions with a variety of learners across a range of grade and age levels and that teaching phonemic awareness to children significantly improves their reading more than instruction that lacks any attention to Phonemic Awareness.”

“Conventional wisdom has suggested that kindergarten students might not be ready for phonics instruction, this assumption was not supported by the data. The effects of systematic early phonics instruction were significant and substantial in kindergarten and the 1st grade, indicating that systematic phonics programs should be implemented at those age and grade levels.”

^* Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Excerpts from the meta-analysis of over 1,900 scientific studies.

Overwhelmingly research has found that phonemic awareness and phonics is a superior way for teaching children to read!

But wait there is more…

Modern Scientific Research on the Brain and How we learn to read

For a very long time many experts have embraced the idea that we store words in our memory in the same way we store visual memories, such us faces or objects. That belief is at the core of the whole word approach.

And, in fact, many reading experts still believe this is the cse.

However, modern scientific research proves otherwise…

But before I tell you how we actually store words in our memory, look at the following factors already pointing out at how visual memory -contrary to still popular belief – is NOT involved:

-

We can read mixed case letters without difficulties.

-

We can read words with different fonts, in print and cursive, and handwritting without difficulties.

-

Word recognition works faster than object recognition, indicating that we are using different storage and retrieval processes.

Let me tell you about the sound scientific evidence now…

Brain scans show that the parts of the brain activated while performing visual memory tasks are different than the parts of the brain activated while reading…

Moreover, scientists in the visual memory area (not related to reading research, therefore unbiased) have indicated that we don’t have the cognitive capacity to remember 30 – 90,000 words for immediate retrieval.

As reading instruction still assumes that we store words as visual images, students who struggle to remember words are many times presumed to have poor visual memory.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. There is only a small relationship between visual memory and our capacity to store words for immediate retrieval while reading.

However, there is a very strong relationship between HEARING skills and our capacity to store words for immediate retrieval while reading (fluent reading capacity).

To be more specific, children that have been trained to hear the actual sounds that form words (phonemic /phonological skills) and are capable to recognize and store those common strings of sounds and visually link them to the letters / words they know become fluent readers.

There is no evidence to suggest that visual memory has a role in word recognition /reading fluency once the letters and the connection between letters and sounds have been learned.

If there seems to be a winner on the ‘Reading Wars’, why do we keep arguing?

Phonics instruction cons…

These are the main arguments against phonics instruction:

- Children only read phonics books: This is one of the main pillars of a proper phonics system. Children should only attempt to read books that are in line with their level of phonics. Otherwise, it is overwhelming for them and can get confused, since they may be exposed to too many exceptions and irregularities. While this is true, that doesn’t mean that parents can’t read more difficult books to their children. And, in fact, they are encouraged to do so.

- Phonics doesn’t help with reading comprehension. Besides, teaching to read using phonics breaks up the words into letters and syllables, which have no actual meaning. However, once the child is able to decode the word, he/she will be able to actually read that entire word, pronounce it and understand its meaning.

- Children learn to read naturally, therefore they don’t need tedious phonics instruction. Whereas it is truth that some children can learn to read by themselves, most won’t be able to figure it out. Besides, there is no harm in receiving phonics instruction for those that are able to learn to decode by themselves.

- There are just too many exceptions and irregularities in English. While it is true that English is full of irregularities and exceptions, there are less of these than what we are led to believe. Besides, there are some rules, patterns and tips and tricks that apply to those “irregular” words that certainly do help in the process of learning to read.

So, saying that phonics has won the war is quite far from what happens in reality.

As we stated at the beginning of the article, there are different ways for teaching phonics.

What our schools have evolved to do to keep both sides of the war happy is establishing a “balanced literacy” strategy that combines both whole word and phonics principles.

What in practicality ends up happening is that there is only a little bit of phonics instruction here and there, rather than a proper curriculum based on phonics.

That is an ineffective method for teaching phonics, and certainly doesn’t work. And this is precisely the sort of evidence that whole word enthusiasts hold on to.

Final thoughts on the Reading Wars

The debate is still hot. This is bizarre as, in our opinion, based on the latest scientific evidence, the number one skill that we need to develop in our children is phonemic awareness.

This way we would have far fewer students with reading difficulties.

And, after having developed strong phonological / phonemic awareness skills, using a proper phonics approach (and not just a little bit of phonics instruction here and there) seems like the way to go.

Free Resources you may be interested in!

Phonemic Awareness Activity Worksheets

Nursery Rhymes Ebook

44+ English sounds chart

List of CVC Words