Download Article

Download Article

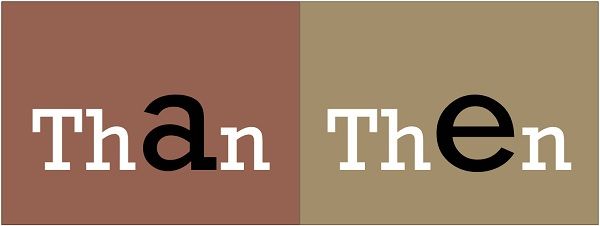

People often misuse the words than and then. It’s a common mistake, in part because the words are pronounced similarly or in some cases because you simply don’t know the difference. However, it is important to know in which situations you would use each word, especially for academic or business writing. As a general rule, use than to indicate comparison and then to indicate time. Practice both usage and pronunciation, and then you’ll be using these words better than anyone you know.

Grammar Help

-

1

Remember that then is a word that indicates time or sequence. In all of its uses, then is used when you want to talk about a point in time or sequence of events. If someone is asking when something happened, then is the appropriate word for your response.[1]

- For example, if your teacher asks you where you were at noon yesterday, you could respond, “I was at lunch then.”

- If someone asks when something will be ready, you could let them know to, “Come back tomorrow afternoon. I will have everything ready by then.”

EXPERT TIP

Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014.

Christopher Taylor, Adjunct Assistant Professor of English, notes: «Than» is generally used to compare two things (e.g., bigger than a quarter), whereas «then» helps you establish a sequence of events (e.g., first this, then that).»

-

2

Connect a series of events using then. Another common use for then is to indicate sequential items. Use then to tell someone what comes next in time, space, or order. Some examples of these uses include:[2]

- We are going to leave at 9, and then we stop for lunch around 11.

- First, you line up part A and part B. Then, you screw them together.

- The inner planets go Mercury, Venus, Earth, and then Mars.

Advertisement

-

3

Add additional or conditional information using then. Then can also be used to mean «in addition,» «moreover,» or «in that case.» Use then when you need to add additional information to your sentence, or to modify outcomes based on conditions.[3]

- If you’re adding additional information you might say, “The dinner costs $20, and then you have to add the tip.”

- To express conditional information you may say, “If the weather is good, then we will go to the beach tomorrow.”

-

4

Use then when you are indicating something that was true at one time. In some special cases, then can be used as an adjective to indicate something that was true at the time, even if it isn’t so anymore. You may hear then used this way often with people like politicians who once held a position, but no longer do.[4]

- For example, “That program was instituted in 2010 by then President Barack Obama.”

- This use isn’t limited to just people, though. You could also say something like, “The historian wrote about the then thriving state of Rome.”

Advertisement

-

1

Use than as a conjunction in comparative contexts. A conjunction is a word used to connect 2 parts of a sentence. When you are talking about a noun (thing, person, place or concept) in relation to another noun, use than to introduce the second part of your comparison. Than is usually preceded by comparative words like better, worse, more, less, higher, lower, smaller, larger, etc. For example:

- There are more onions than scallions in your fridge.

- I can run faster now than I could last year.

- I like cloudy weather more than I like the sun.

-

2

Indicate a correlation between 2 events with than. Than can also be used with past tense verbs and some adverbial expressions. Adverbial expressions are multi-word expressions that function to modify or qualify a verb. In these cases, than is being used to indicate that one thing correlated with another.[5]

- For example, if it feels like your alarm goes off right after you fall asleep, you may say, “No sooner did I lay my head down than my clock started to ring.”

- This usage may seem similar to how then may be used sometimes, which can be confusing. The difference is that then would be used if there was a sequence, but than is not describing a sequence in this instance. It is showing correlation or relationship between 2 things, such as laying down your head and your alarm clock going off.

-

3

Use than when you can’t find a synonym for what you’re saying. If you’re trying to decide between than and then, try substituting the word. Than is a unique word with no synonyms. Then, however, can be substituted for works like “subsequently,” “next,” or “later.»[6]

- For example, it wouldn’t work to say “Jessica arrived later subsequently Joe.” Even though you’re talking about time, in this context you’re still comparing who was later. That is why this sentence needs to be, “Jessica arrived later than Joe.”

- However, it does make sense to say, “First and need to shower and next I have to catch the bus.” In this context, “next” can be substituted for then.

Advertisement

-

1

Test your usage. If you’re ever confused when you’re writing, test each word to see if it makes sense in the context of your sentence. Try asking yourself these questions as you write to find the correct word:[7]

- If I write the word «next» instead of «then,» will the sentence still make sense?

- «I will go to the store next» makes sense, so here we would say «I will go to the store then.»

- If I write the phrase «in comparison to» instead of the word «than,» will the sentence still make sense?

- «A used car costs less in comparison to a new car» makes sense, so you’d want to say «It costs less than a new car.»

- If I write the word «next» instead of «then,» will the sentence still make sense?

-

2

Practice writing with then and than frequently. The best way to get used to the different uses of then and than is to use them in context. Try writing a brief comparative essay to help you get used to than. Then, try writing out a set of instructions to practice your use of then. [8]

- Pay attention to your use of then and than in your everyday writing, too. Set aside a few extra minutes to proofread your essays, letters, school work, and documents so that you can check for the correct usage.

- You can even look for then and than quizzes and exercises online to help you test your usage.[9]

-

3

Pronounce the words differently. Phonetically speaking, native speakers of English use the schwa (ǝ, kind of like a soft «eh» sound) because it’s more efficient in daily conversations. Consequently, lots of «a»s and «e»s are not pronounced distinctly. However, taking the time to pronounce the words distinctly can help reinforce their use in your mind.[10]

- Try saying than with your mouth opened wide and the tongue pressed down toward your teeth. The vowel sounds from the back of the mouth and the throat is somewhat constricted.

- Say then with your mouth partially opened. The vowel rises from a relaxed throat and the tongue rests.

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

What’s the difference between the words «than» and «then»?

Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014.

English Professor

Expert Answer

-

Question

How do you use the word «then» in a sentence?

Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014.

English Professor

Expert Answer

-

Question

When would you use «than» in a sentence?

Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014.

English Professor

Expert Answer

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

Video

-

The simplest mnemonic is that «then» is a time word equivalent to «when,» so they are both spelled with an «e.»

-

Pay attention to grammar check. If your word processor underlines or highlights the word «then» or «than,» you may have chosen the wrong word. Re-read your sentence to be sure.

-

People tend to misuse then more than than. Than mistakes may look strange or grossly incorrect; however, the then mistakes may seem more acceptable. Pay special attention to then and its uses.

Show More Tips

Advertisement

About This Article

Article SummaryX

To use the words than and then properly, remember that than is used when comparing things and then is used to indicate time. For example, if you were comparing how many oranges and apples you have, you would say «I have more oranges than apples.» But if you were explaining which fruit you bought first, you would say «I bought oranges and then I bought apples.» To learn helpful tricks for remembering the difference between than and then, keep reading!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 3,704,757 times.

Did this article help you?

- Top Definitions

- Quiz

- Than Vs. Then

- Examples

- British

- Idioms And Phrases

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

[ than, then; unstressed thuhn, uhn ]

/ ðæn, ðɛn; unstressed ðən, ən /

This shows grade level based on the word’s complexity.

conjunction

(used, as after comparative adjectives and adverbs, to introduce the second member of an unequal comparison): She’s taller than I am.

(used after some adverbs and adjectives expressing choice or diversity, such as other, otherwise, else, anywhere, or different, to introduce an alternative or denote a difference in kind, place, style, identity, etc.): I had no choice other than that. You won’t find such freedom anywhere else than in this country.

(used to introduce the rejected choice in expressions of preference): I’d rather walk than drive there.

except; other than: We had no choice than to return home.

when: We had barely arrived than we had to leave again.

preposition

in relation to; by comparison with (usually followed by a pronoun in the objective case): He is a person than whom I can imagine no one more courteous.

QUIZ

CAN YOU ANSWER THESE COMMON GRAMMAR DEBATES?

There are grammar debates that never die; and the ones highlighted in the questions in this quiz are sure to rile everyone up once again. Do you know how to answer the questions that cause some of the greatest grammar debates?

Which sentence is correct?

Origin of than

before 900; Middle English, Old English than(ne) than, then, when, variant (in special senses) of thonnethen; cognate with German dann then, denn than, Dutch dan then, than

grammar notes for than

Whether than is to be followed by the objective or subjective case of a pronoun is much discussed in usage guides. When, as a conjunction, than introduces a subordinate clause, the case of any pronouns following than is determined by their function in that clause: He is younger than I am. I like her better than I like him. When than is followed only by a pronoun or pronouns, with no verb expressed, the usual advice for determining the case is to form a clause mentally after than to see whether the pronoun would be a subject or an object. Thus, the sentences He was more upset than I and She gave him more sympathy than I are to be understood, respectively, as He was more upset than I was and She gave him more sympathy than I gave him. In the second sentence, the use of the objective case after than ( She gave him more sympathy than me ) would produce a different meaning ( She gave him more sympathy than she gave me ). This method of determining the case of pronouns after than is generally employed in formal speech and writing.

Than occurs as a preposition in the old and well-established construction than whom : a musician than whom none is more expressive. In informal, especially uneducated, speech and writing, than is usually treated as a preposition and followed by the objective case of the pronoun: He is younger than me. She plays better poker than him, but you play even better than her. See also but1, different, me.

WORDS THAT MAY BE CONFUSED WITH than

than , then

Words nearby than

Thamar, Thames, Thames River, thamin, Thammuz, than, thana, thanage, thanato-, thanatology, thanatophobia

Dictionary.com Unabridged

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

THAN VS. THEN

What’s the difference between than and then?

Than is a very common word used in comparisons, as in She’s a little older than you or This hot sauce is a lot spicier than that one. Then is a very common word that’s used in situations involving what comes next—either in terms of time (as in Just then, the door opened or We saw a movie and then we drove home) or a result (as in If you forget to water the plants, then they will wilt).

Grammatically speaking, than is used as a conjunction or preposition, while then is used as an adverb or adjective.

Perhaps the most common way the two words are confused is when then is used when it should be than, but doing the reverse is also a common mistake.

One way to tell if you’re using the right word is to remember that then is usually used to indicate what comes next, and then and next are both spelled with the letter e.

Here’s an example of then and than used correctly in the same sentence.

Example: If you want to be an expert, then you’ll need more experience than you have now.

Want to learn more? Read the full breakdown of the difference between than and then.

Quiz yourself on than vs. then!

Should than or then be used in the following sentence?

I went to the grocery store, _____ the dry cleaners.

How to use than in a sentence

-

And yet as Robert Ward discovered, Marvin—for all of his larger-than-life machismo—was surprising in real life.

-

My younger, straighter-than-an-arrow son was stopped and arrested in two separate jurisdictions a few years ago.

-

He was the larger-than-the-life figure, and he loomed impossibly large over this campaign.

-

Barack Obama is in for a rougher-than-usual couple of months.

-

Kim is mocking the entire value system on which she built her career, as well as her own less-than-savory past.

-

Jack probably learned more about the Bible during that trip-its history and its heroes-than during all his former years.

-

«The Wright brothers invented the lighter-than-air ship early in the twentieth century,» he said.

-

Rugel told him that this was the moment of equilibrium, the peak of the faster-than-light motion.

-

The competitor who paid the less-than-carload rate on an equal volume of business would be sadly handicapped.

-

Altogether, it was not until the nineteenth century that any real progress toward flight in a heavier-than-air machine was made.

British Dictionary definitions for than

than

/ (ðæn, unstressed ðən) /

conjunction, preposition (coordinating)

used to introduce the second element of a comparison, the first element of which expresses differenceshorter than you; couldn’t do otherwise than love him; he swims faster than I run

used after adverbs such as rather or sooner to introduce a rejected alternative in an expression of preferencerather than be imprisoned, I shall die

other than besides; in addition to

Word Origin for than

Old English thanne; related to Old Saxon, Old High German thanna; see then

usage for than

In formal English, than is usually regarded as a conjunction governing an unexpressed verb: he does it far better than I (do). The case of any pronoun therefore depends on whether it is the subject or object of the unexpressed verb: she likes him more than I (like him); she likes him more than (she likes) me . However in ordinary speech and writing than is usually treated as a preposition and is followed by the object form of a pronoun: my brother is younger than me

Collins English Dictionary — Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition

© William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins

Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Other Idioms and Phrases with than

see actions speak louder than words; bark is worse than one’s bite; better late than never; better safe than sorry; better than; bite off more than one can chew; blood is thicker than water; easier said than done; eyes are bigger than one’s stomach; in (less than) no time; irons in the fire, more than one; less than; more dead than alive; more fun than a barrel of monkeys; more in sorrow than in anger; more often than not; more sinned against than sinning; more than meets the eye; more than one bargained for; more than one can shake a stick at; more than one way to skin a cat; none other than; no sooner said than done; other than; quicker than you can say Jack Robinson; wear another (more than one) hat.

The American Heritage® Idioms Dictionary

Copyright © 2002, 2001, 1995 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

«Than» is neither a conjunction nor a preposition, it is a special function word with only one single use — after a comparative. Actually it can only be used in the structure verb (mostly to be) + comparative + than + complement. Prepositions or conjunctions don’t behave in this way.

Dictionaries that label this function word as conjunction or preposition have no feeling that this special word does not fit into these two word classes.

Even etymonline uses the label conjunction. And its historical explanation does not help much.

I can give only my view: If you say Peter is taller than his sister, you say: Peter is taller (seen from there: seen from his sister). In German there is the word davon (there+from). This could give an understanding of the word than. In German there is also an old «denn» after comparative:

Geben ist seeliger denn Nehmen (Giving is better than taking). And we have an old «von dannen» (from there).

If you talk about the size of a thing A, you can compare it with a thing B.

And you can say compared with B A is taller — or you can say: seen from B A is taller.

This way of expressing the idea was already in use in Latin. The Romans used an ablative (indicating from where) after a comparative: Nulla bestia fidelior est cane (No animal is more loyal than the dog). You could explain: «No animal is more loyal (seen) from the dog.» This ablative is called ablativus comparationis (ablative of comparison).

So «than» has a special origin and exactly one use comparable to the function word «ago» and you get problems if you want to force such a word into the traditional word classes. That does not help to understand the word, on the contrary. You get wrong ideas. And some begin to rack their brain when «than» is a conjunction and when a preposition.

- Then there comes a day when it is proved that Joseph is a better football player than Jacob.

Here, then represents time, whereas than introduces Jacob for comparing with Joseph.

So, there is a huge difference between than and then, which we must understand to clearly describe what we meant while using them.

Content: Than Vs Then

- Comparison Chart

- Definition

- Key Differences

- Examples

- How to remember the difference

Comparison Chart

| Basis for Comparison | Than | Then |

|---|---|---|

| Meaning | The word ‘than’ is used in comparative sentences, to make compare two entities. | Then is an action word, which is an expression of time, i.e. what happens next. |

| Pronunciation | ðan | ðɛn |

| Part of speech | Conjunction or Preposition | Adjective or Adverb |

| Used to | Indicate second element in a comparison | Indicate second part in a sentence |

| Position | Middle of the sentence | Beginning or end of the sentence |

| Examples | When it comes to intelligence, Akshada is a step ahead than Janvi | Shreya deposited the cash to the hospital and then the operation started. |

Definition of Than

‘Than’ is basically a comparative term, which is used to make a comparison between two entities, units, individuals and other elements. That is why its position in a sentence is just after a comparative adjective and adverb. Come let’s understand the use of ‘than’ in our sentences:

- It is used as a preposition, it emphasizes the other entity of comparison:

- Bill Gates is richer than Mark Zuckerberg.

- My daughter scored better percentage in class 12th than her friend.

- It acts as a conjunction to highlight an exception:

- I prefer walking rather than jogging as an exercise.

- There is no better hotel other than this.

- It can also be used to show an option or diversity, and it also indicates an unpreferred choice:

- I would rather be an author than a poet.

Definition of Then

‘Then’ is an expression of time in a sentence, i.e. it indicates what happens afterwards. As an adverb, it is used to show ‘at what time’ or ‘to denote the sequence of events’. When ‘then’ is used as an adjective, it indicates something which was true at a certain time in the past, but it is not true at present. Then as a noun refers to ‘that time’.

One can also use ‘then’ while communication to point out what you are going to say next. It can be used to give additional information or conclude something. Now, let’s understand the use of ‘then’ with the help of examples:

- It is used to express that time in past or future:

- You should have told me the decision then.

- Just then, we started chatting.

- Then I moved to the city of my dreams, i.e. Dehradun.

- To refer next step or point:

- First I will do my work, then I will watch a movie.

- Let her decide first, then talk about the matter.

- To imply in addition:

- This is the basic car model, then there are premium models also.

- To refer to consequence or outcome:

- If you study harder, then you will succeed.

The points given below are substantial so far as the difference between than and then is concerned:

- The word ‘than’ is used when there is some kind of comparison between two subjects. On the other hand, then is an adverb that expresses actions in time.

- Than is commonly used as a preposition or conjunction, whereas then is mainly used as an adverb or adjective.

- The position of ‘then’ is either at the beginning or at the end of the sentence. Conversely, than is positioned at the middle of the sentence, that links two elements of comparison.

- While than introduces the second element in a comparison, then adds another part in a sentence.

Examples

Than

- I want to visit any Asian country, other than China, as I’ve already been there.

- Communication skills of Kapil are better than Rahul.

Then

- Once the project is complete, then I will switch the company.

- If Priya doesn’t come by tomorrow morning, then we have to take strict action against her.

How to remember the difference

‘Then’ is a rhyming word of ‘when’, which also indicates time, so you can relate the meaning of then in this sense. Further, to understand the use of than, you must memorise it with ‘that’. When one thing is better than another, you would say: This is better than that.

Learn to write algebraic expressions in and out of word problems.

Why do we have math if we can describe things in words?

Sometimes in math we describe an expression with a phrase. For example, the phrase

can be written as the expression

Similarly, when we describe an expression in words that includes a variable, we’re describing an algebraic expression (an expression with a variable).

can be written as the algebraic expression

But why? Why use math if we can describe things in words? One of the many reasons is that math is more precise and easier to work with than words are. This is a question you should keep thinking about as we dig deeper into algebra.

Different words for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division

Here is a table that summarizes common words for each operation:

| Operation | Words | Example algebraic expression |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | plus, sum, more than, increased by | x, plus, 3 |

| Subtraction | subtracted, minus, difference, less than, decreased by | p, minus, 6 |

| Multiplication | times, product | 8, k |

| Division | divided, quotient | a, divided by, 9 |

For example, the word «product» tells us to use multiplication. So, the phrase

Let’s take a look at a trickier example

Write an expression for «m decreased by 7«.

Notice that the phrase «decreased by» tells us to use subtraction.

So the expression is m, minus, 7.

Let’s try some practice problems!

Basic expressions

More complicated expressions

Word problems

progressive aspects as well as the simple past:

14*

212 Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar

(1) / wrote my letter of 16 July 1972 with a special pen. (2a) / have written with a special pen since 1972.

(2bi) / wrote with a special pen from 1969 to 1972. (2bii) / was writing poetry with a special pen.

3.36 The Future

There is no obvious future tense in English corresponding to the time/tense relation for present and past. Instead there are several possibilities for denoting future time. Futurity, modality, and aspect are closely related, and future time is rendered by means of modal auxiliaries or semi-auxiliaries, or by simple present forms or progressive forms.

3.37 Will and Shall

will or ’11 + infinitive in all persons

shall + infinitive (in 1st person only; chiefly BrE) / will/shall arrive tomorrow.

He’ll be here in half an hour.

The future and modal functions of these auxiliaries can hardly be separated but «shall» and, particularly, «will» are the closest approximation to a colourless, neutral future. «Will» for future can be used in all persons throughout the English-speaking world, whereas «shall» (for 1st person) is largely restricted in this usage to southern BrE.

3.45 Mood

Mood is expressed in English to a very minor extent by the subjunctive as in

So be it then! to a much greater extent by

past form as in

If you taught me, I would learn quickly. but above

all, by means of the modal auxiliaries, as in

//is strange that he should have left so early.

3.46The Subjunctive

Three categories of subjunctive may be distinguished:

(a) The MANDATIVE Subjunctive in that-clauses has only one form, the base (V); this means there is lack of the regular indicative concord between subject and finite verb in the 3rd person singular present, and the present and past tenses are indistinguishable. This subjunctive can be used with any verb in subordinate that-clause when the main clause contains an expression of recommendation, resolution, demand, and so on (We demand, require, move, insist, suggest, ask, etc., that…). The use of this subjunctive occurs chiefly in formal style (and especially in AmE) where in less formal contexts one would rather make use of other devices, such as toinfinitive or should + infinitive. It is necessary that every member inform himself of these rules. It is necessary that every member should inform himself of these

rules. It is necessary for every member to inform himself of these rules.

(b)The FORMULAIC Subjunctive also consists of the base (V) but is only used in clauses in certain set expressions which have to be learned as wholes:

Come what may, we will go ahead.

God save the Queen!

Suffice it to say that…

Be that as it may…

Heaven forbid that…

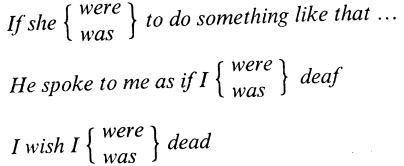

(c)The SUBJUNCTIVE «were» is hypothetical in meaning and is

used in conditional and concessive clauses and in subordinate clauses after optative verbs like «wish». It occurs as the 1st and 3rd person singular past of the verb «be», matching the indicative «was», which is the more common in less formal style:

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

214 Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar

Questions:

1.What classification of verbs did the authors work out?

2.What principles do they suggest to differentiate between finite and nonfinite verbs?

3.What criteria of classifying verb phrases do they suggest?

4.How do they define the categorial meanings of tense, aspect, and mood?

5.Why do they treat tense, aspect, and mood as interconnected categories?

6.What does the analysis of the present and past tenses in relation to the progressive and perfective aspects show?

7.How do they substantiate the absence of the future tense in English?

8.What three categories of subjunctive do they distinguish?

7.

Qraustein G., Hoffmann A., Schentke M.

English Grammar. A University Handbook

The Category of Mood

The verbal category of mood serves to express the speaker’s attitude towards the factuality («Faktizitat») of a state-of-affairs described in a sentence. By means of this category the speaker can present the state-of-affairs as real, existing in fact, or as hypothetical, i.e. not necessarily real. In contemporary English the category of mood is decaying, the forms of the hypothetical mood (subjunctive) falling more and more into disuse and in many cases being replaced by modals.

Structure and Functions

The category of mood consists of three constituents, the indicative and the subjunctives I and II. They form a binary opposition, the unmarked member (indicative) being opposed to the marked member, which appears in two variants (subjunctive I and II):

,, (~ _____ f call-0 (no ‘-s’/tense/correlation/aspect) call-0 + lcall-ed

The categorial meaning of the category of mood indicates the hypothetical nature of the state-of-affairs described as seen from the speaker’s point of view. The functions of the marked forms are identical with the categorial meaning of the category of mood:

Long live the workers’ revolution. It is time Kurt went on a diet.

The function of the unmarked form negates this categorial meaning in that it indicates the «reality of the state-of-affairs»:

A small section of the working class has now more access to culture

than it had in the 1930’s.

These formal and functional relations form the mood paradigm:

It is only the indicative that has full tense, correlation and aspect marking. […] The subjunctive I form of the verb is homonymous with the SimPres (0) form: «I suggest that he come/write/go». «Be» has the subjunctive I form «be». Subjunctive I, which is more common in AmE than in BrE where it is used only in formal style, occurs in an optative or a possibility function:

The boss insisted that Willard arrive at eight sharp. She suggested that I be the cook. (AmE) […] If any person be found guilty, he shall have the right of appeal. The subjunctive II form of the verb is homonymous with its Sim-• Past form and may be used with reference to the present and future: »• «if I called/wrote/went». «Be» has «were» in all persons, in colloquial , speech also «was». Reference to the past (or anterior

present) is made I, by adding «have -ed-participle»: «if I had called/written/gone». Sub-I junctive II may combine with aspect markers: «if I were going to call/ were calling». It represents a state- of-affairs as imaginary. […]/ wish I had thought of him before.

He took it from me as if I were handing him the Cullinam diamond.

(pp. 174-175)

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

|

216 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

Questions:

1.What is the categorial meaning of mood?

2.What types of mood forms do the authors recognize?

3.What functions are performed by Subjunctive I and SubjiH|Ctjve jj cording to the authors?

References

Blokh M. Y. A Course in Theoretical English Grammar. — M., 20QQ _ p 119. 197. . .

. — , 1975. — . 97-148. . .

, 2001.- . 25-55. .,

., .

. — ., 1981. — , 46-87

. . —

. — ., 1986. .

. — .: , , 1996. — . 479,202- 250.

Francis W.N. «he Structure of American English. — N.Y., __ M

Graustein G., Hoffmann A., Schentke M. English Grammar. University Handbook. — Leipzig: VEB Verlag Enzyklopadie, 1977. — {> 174.175

Joos M. The English Verb. Form and Meaning. — Madison & Milwaukee 1964.

Ilyish B. The Structure of Modern English. — L., 1971. — P. 123.129 Quirk R., Greenbaum S., Leech G., Svartvik J. A University Qrammar of

English.-M., 1982. Strang B. Modern English Structure. — London, 1962.

Seminar 8

ADJECTIVE AND ADVERB

1.A general outline of the adjective.

2.Classification of adjectives.

3.The problem of the stative.

4.The category of adjectival comparison.

5.A general outline of the adverb.

6.Structural types of adverbs. Modern interpretations of the «to bring up» type of adverbs.

7.The lexemic subcategorizations of the adverbs ending in «-ly».

1. Adjective as a Part of Speech

The adjective expresses the categorial semantics of property of a i substance. It means that each adjective used in the text presupposes relation to some noun the property of whose referent it denotes, such fas its material, colour, dimensions, position, state, and other charac-fteristics both permanent and temporary. It follows from this that, i unlike nouns, adjectives do not possess a full nominative value.

Adjectives are distinguished by a specific combinability with nouns, which they modify, if not accompanied by adjuncts, usually in pre-position, and occasionally in post-position; by a combinability with link-verbs, both functional and notional; by a combinability with modifying adverbs.

In the sentence the adjective performs the functions of an attribute I and a predicative. Of the two, the more specific function of the adjec-

|

218 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

tive is that of an attribute, since the function of a predicative can be performed by the noun as well.

To the derivational features of adjectives belong a number of suffixes and prefixes.of which the most important are: -ful (hopeful), -less (flawless), -ish (bluish), -ous (famous), -ive (decorative), -ic (basic) ;un- (unprecedented), in- (inaccurate),pre- (premature). Among the adjectival affixes should also be named the prefix a-, constitutive for the stative subclass.

The English adjective is distinguished by the hybrid category of comparison. The ability of an adjective to form degrees of comparison is usually taken as a formal sign of its qualitative character, in opposition to a relative adjective which is understood as incapable of forming degrees of comparison by definition. However, in actual speech the described principle of distinction is not at all strictly observed.

On the one hand, adjectives can denote such qualities of substances which are incompatible with the idea of degrees of comparison. Here refer adjectives like extinct, immobile, deaf, final, fixed, etc.

On the other hand, many adjectives considered under the heading of relative still can form degrees of comparison, thereby, as it were, transforming the denoted relative property of a substance into such as can be graded quantitatively, e.g.: of a military design — of a less military design -of a more military design.

In order to overcome the demonstrated lack of rigour in the differentiation of qualitative and relative adjectives, we may introduce an additional linguistic distinction which is more adaptable to the chances of usage. The suggested distinction is based on the evaluative function of adjectives. According as they actually give some qualitative evaluation to the substance referent or only point out its corresponding native property, all the adjective functions may be grammatically divided into «evaluative» and «specificative». In particular, one and the same adjective, irrespective of its being basically «relative» or «qualitative», can be used either in the evaluative function or in the specificative function.

The introduced distinction between the evaluative and specificative uses of adjectives, in the long run, emphasizes the fact that the morphological category of comparison (comparison degrees) is potentially represented in the whole class of adjectives and is constitutive for it.

|

Seminar 8. Adjective and Adverb |

219 |

2. Category of Adjectival Comparison

The category of adjectival comparison expresses the quantitative characteristic of the quality of a nounal referent. The category is constituted by the opposition of the three forms known under the heading of degrees of comparison; the basic form (positive degree), having no features of comparison; the comparative degree form, having the feature of restricted superiority (which limits the comparison to two elements only); the superlative degree form, having the feature of unrestricted superiority.

Both formally and semantically, the oppositional basis of the category of comparison displays a binary nature. In terms of the three degrees of comparison, at the upper level of presentation the superiority degrees as the marked member of the opposition are contrasted against the positive degree as its unmarked member. The superiority degrees, in their turn, form the opposition of the lower level of presentation, where the comparative degree features the functionally weak member, and the superlative degree, respectively, the strong member. The whole of the double oppositional unity, considered from the semantic angle, constitutes a gradual ternary opposition.

The analytical forms of comparison, as different from the synthetic forms, are used to express emphasis, thus complementing the synthetic forms in the sphere of this important stylistic connotation. Analytical degrees of comparison are devoid of the feature of «semantic idiomatism» characteristic of some other categorial analytical forms, such as, e.g., the forms of the verbal perfect. For this reason the analytical degrees of comparison invite some linguists to call in question their claim to a categorial status in English grammar.

3. Elative Most-Construction

The mosJ-combination with the indefinite article deserves special consideration. This combination is a common means of expressing elative evaluations of substance properties.

The definite article with the elative raosr-construction is also possible, if leaving the elative function less distinctly recognizable. Cf:

They gave a most spectacular show -1 found myself in the most awkward situation. The expressive nature of the elative superlative as such

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

|

220 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

provides it with a permanent grammatico-stylistic status in the language. The expressive peculiarity of the form consists in the immediate combination of the two features which outwardly contradict each other: the categorial form of the superlative, on the one hand, and the absence of a comparison, on the other.

4. Less/Least-Construction

After examining the combinations of less/least with the basic form of the adjective we must say that they are similar to the more/most- combinations, and constitute specific forms of comparison, which may be called forms of «reverse comparison». The two types of forms cannot be syntagmatically combined in one and the same form of the word, which shows the unity of the category of comparison. Thus, the whole category includes not three, but five different forms, making up the two series — respectively, direct and reverse. Of these, the reverse series of comparison (the reverse superiority degrees, or «inferiority degrees», for that matter) is of far lesser importance than the direct one, which evidently can be explained by semantic reasons.

5. Adverb as a Part of Speech

The adverb is usually defined as a word expressing either property of an action, or property of another property, or circumstances in which an action occurs. This definition, though certainly informative and instructive, fails to directly point out the relation between the adverb and the adjective as the primary qualifying part of speech.

To overcome this drawback, we should define the adverb as a notional word expressing a non-substantive property, that is, a property of a non-substantive referent. This formula immediately shows the actual correlation between the adverb and the adjective, since the adjective is a word expressing a substantive property.

In accord with their categorial semantics adverbs are characterized by a combinability with verbs, adjectives and words of adverbial nature. The functions of adverbs in these combinations consist in expressing different adverbial modifiers. Adverbs can also refer to whole situations; in this function they are considered under the heading of «situation-determinants».

|

Seminar 8. Adjective and Adverb |

221 |

In accord with their word-building structure adverbs may be simple and derived.

The typical adverbial affixes in affixal derivation are, first and foremost, the basic and only productive adverbial suffix -ly (slowly), and then a couple of others of limited distribution, such as -ways (sideways), -wise (clockwise), -ward(s) (homewards). The characteristic adverbial prefix is a- (away). Among the adverbs there are also peculiar composite formations and phrasal formations of prepositional, conjunctional and other types: sometimes, at least, to and fro, etc.

Adverbs are commonly divided into qualitative, quantitative and circumstantial. Qualitative adverbs express immediate, inherently non-graded qualities of actions and other qualities. The typical adverbs of this kind are qualitative adverbs in -ly. E.g.: bitterly, plainly. The adverbs interpreted as «quantitative» include words of degree. These are specific lexical units of semi-functional nature expressing quality measure, or gradational evaluation of qualities, e.g.: of high degree: very, quite; of excessive degree: too, awfully; of unexpected degree: surprisingly; of moderate degree: relatively; of low degree: a little; of approximate degree: almost; of optimal degree: adequately; of inadequate degree: unbearably; of under-degree: hardly. Circumstantial adverbs are divided into functional and notional.

The functional circumstantial adverbs are words of pronominal nature. Besides quantitative (numerical) adverbs they include adverbs of time, place, manner, cause, consequence. Many of these words are used as syntactic connectives and question-forming functionals. Here belong such words as now, here, when, where, so, thus, how, why, etc. As for circumstantial notional adverbs, they include adverbs of time

(today, never, shortly) and adverbs of place (homeward(s), near, ashore). The two varieties express a general idea of temporal and spacial orientation and essentially perform deictic (indicative) functions in the broader sense. On this ground they may be united under the general heading of «orientative» adverbs.

Thus, the whole class of adverbs will be divided, first, into nominal and pronominal, and the nominal adverbs will be subdivided into qualitative and orientative, the former including genuine qualitative adverbs and degree adverbs, the latter falling into temporal and local adverbs, with further possible subdivisions of more detailed specifications.

222 Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar

As is the case with adjectives, this lexemic subcategorization of adverbs should be accompanied by a more functional and flexible division into evaluative and specificative, connected with the categorial expression of comparison. Each adverb subject to evaluational grading by degree words expresses the category of comparison, much in the same way as adjectives do. Thus, not only qualitative, but also orientative adverbs, proving they come under the heading of evaluative, are included into the categorial system of comparison, e.g.: ashore

— more ashore — most ashore — less ashore — least ashore.

Questions:

*1. What categorial meaning does the adjective express?

•2. What does the adjectival specific combinability find its expression in?

3.What proves the lack of rigid demarcation line between the traditionally identified qualitative and relative subclasses of adjectives?

4.What is the principle of differentiation between evaluative and specifica

tive adjectives?

* 5. What does the category of adjectival comparison express?

• 6. What arguments enable linguists to treat the category of adjectival comparison as a five-member category?

7.What does the expressive peculiarity of the elative superlative consist in?

8.What is the categorial meaning of the adverb?

19. What combinability are adverbs characterized by?

10.What is typical of the adverbial word-building structure?

11.What semantically relevant sets of adverbs can be singled out?

12.How is the whole class of adverbs structured?

‘13. What does the similarity between the adjectival degrees of comparison and adverbial degrees of comparison find its expression in?

I.State the classification features of the adjectives and adverbs used in the given sentences.

MODEL: «I found myself weary and yet wakeful, tossing restlessly from side to side...»

«weary» — a qualitative evaluative adjective; «wakeful» — a qualitative speculative adjective; «restlessly» — an evaluative qualitative adverb.

1.Rosemary Fell was not exactly beautiful. Pretty? Well, if you took her to pieces… But why be so cruel as to take anyone to pieces? She was

223

young, brilliant, extremely modern, exquisitely dressed, amazingly wellread in the newest of the new books, and her parties were the most delicious mixture of the really important people and… artists — quaint creatures, discoveries of hers, some of them too terrifying for words, but others quite presentable and amusing (Mansfield).

2.He was in a great quiet room with ebony walls and a dull illumination that was too faint, too subtle, to be called a light (Fitzgerald).

3.«There!» cried Rosemary again, as they reached her beautiful big bed room with the curtains drawn, the fire leaping on the wonderful lacquer furniture, her gold cushions and the primroses and blue rags (Mansfield).

4.Medley had already risen hurriedly to his feet. The look in his eyes said he was going straight to his telephone to tell Doctor Llewellyn apologet ically that he, Llewellyn, was a superb doctor and he, Medley, could hear him perfectly. Oxborrow was on his heels. In two minutes the room was clear of all but Con, Andrew, and the remainder of the beer (Cronin).

5.She was helpful, pervasive, honest, hungry, and loyal (Cheever).

6.Dr. Trench. I will be plain with you. I know that Blanche has a quick temper. It is part of her strong character and her physical courage, which is greater than that of most men, I can assure you. You must be pre pared for that. If this quarrel is only Blanche’s temper, you may take my word for it that it will be over before to-morrow (Shaw).

7.The elder man was about forty with a proud vacuous face, intelligent eyes, and a robust figure (Fitzgerald).

8.He was tall and homely^ wore horn-rimmed glasses, and spoke in a deep voice (Cheever).

II.Comment on the use of the forms of superlative degree of the adjective and on the use of the words «more» and «most» in the following sentences.

MODEL: «It was a most unpleasant telephone call.» This is a case of the elative «mos/-construction». The morphological form «a most unpleasant» is not a superlative degree of the adjective but an elative form expressing a high degree of the quality in question.

a)

1.She who had been most upset and terrified at the morning’s discovery now seemed to regard the whole thing as a personal insult (James).

2.The Fifth Symphony by Beethoven is a most beautiful piece of music.

3.I have been with good people, far better than you (Ch. Bronte).

4.Sure, it’s difficult to do about in the wrongest way possible (Wilson).

5.The more we go into the thing, the more complex the matter becomes (Wilson).

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

|

224 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

b)

1.When Sister Cecilia entered, he rose and gave her his most distinguished bow (Cronin).

2.And he thought how much more advanced and broad-minded the young er generation was (Bennett).

3.She was the least experienced of all (Bennett).

4.She is best when she is not trying to show off (Bennett).

5.He was none the wiser for that answer, but he did not try to analyse it (Aldridge).

c)

1.You’re the most complete man I’ve ever known (Hemingway).

2.Now in Hades — as you know if you ever had been there the names of the more fashionable preparatory schools and colleges mean very little (Fitzgerald).

3.As they came closer, John saw that it was the tail-light of an immense automobile, larger and more magnificent than any he had ever seen (Fitzgerald).

4.It was a most unhappy day for me when I discovered how ignorant I am (Saroyan).

5.«Have you got a dollar?» asked Tripp, with his most fawning look and his dog-like eyes that blinked in the narrow space between his highgrowing matted beard and his low-growing matted hair (O.Henry).

d)

1.She had, however, great hopes of Mrs. Copleigh, and felt that once thoroughly rested herself, she would be able to lead the conversation to the most fruitful subjects possible (Christie).

2.«Still on your quest? A sad task and so unlikely to meet with success. I really think it was a most unreasonable request to make.» (Christie)

3.«I know. I know. I’m often the same. I say things and I don’t really know what I mean by them. Most vexing.» (Christie)

4.«Then it is he whom you suspect?» «I dare not go so far as that. But of the three he is perhaps the least unlikely.» (Doyle)

5.In the first place, your Grace, I am bound to tell you that you have placed yourself in a most serious position in the eyes of the law (Doyle).

III.Give the forms of degrees of comparison and state whether they are formed in a synthetic, analytical or suppletive way,

a)wet, merry, real, far;

b)kind-hearted, shy, little, friendly;

|

Seminar 8. Adjective and Adverb |

225 |

c)certain, comical, severe, well-off;

d)sophisticated, clumsy, old-fashioned, good-looking.

IV. Translate the given phrases into English using Adjective + Noun, Noun + Noun combinations where possible, or else prepositions or genitive case (give double variants where possible):

a), ( ),

, ,

, , , ,

, , , , ,

, ,

, , , ,

, , ;

b), , ,

, , , ,

, , ,

; , , , ,

, ;

c), , , ,

, ,

, , , ,

, ;

d), , , ,

, , , ,

;

e), , ,

, , , ,

, , , ,

, , , ,

, , ,

, .

V.Give the Russian equivalents for the English word combinations:

a.iron rations, iron foundry (ironworks), iron industry, ironware (iron mongery), ferrous metal, ferrous oxide;

b.celestial map, sky-force, celestial food, sky-line, skyway, celestial navi-

rgation;

c. sea-boy, sea-water, naval base, «sea dog», Admiralty, Admiralty mile,

sea-cock, dog-fish, echinus;

d.sea-hedgehog, starfish, sea-horse, sea-dye, grass-wrack, sea kale, «old salt», sea-cliff, sea-cow, sea-lane.

15 — 3548

|

226 |

Seminars on Theoretical English Grammar |

VI. Account for the peculiarity of the underlined word-forms:

1.I am the more bad because I realize where my badness lies.

2.Wimbledon will be yet more hot tomorrow.

3.The economies are such more vulnerable, such more weak.

4.Certainly, Ann was doing nothing to prevent Pride’s finally coming out of the everything into the here.

5.He turned out to be even more odd than I had expected.

6.That’s the way among that class. They up and give the old woman a friendly clap, just as you or me would swear at the missus.

7.«You see, by this time we was on the peacefulest of terms.» (O.Henry)

8.«Well, you never could be fly,» says Myra with her special laugh, which was the provokingest sound I ever heard except the rattle of an empty canteen against my saddle-horn (O.Henry).

Selected Reader

1.

Quirk R., Qreenbaum S., Leech Q., Svartvik J.

A University Grammar of English

Adjectives

5.1. Characteristics of the Adjective

We cannot tell whether a word is an adjective by looking at it in isolation: the form does not necessarily indicate its syntactic function. Some suffixes are indeed found only with adjectives, e.g.: -ous, but many common adjectives have no identifying shape, e.g.: good, hot, little, young, fat. Nor can we identify a word as an adjective merely considering what inflections or affixes it will allow. […]

5.2.

Most adjectives can be both attributive and predicative, but some are either attributive only or predicative only.

|

Seminar 8. Adjective and Adverb |

227 |

Two other features usually apply to adjectives:

(1)Most can be premodified by the intensifier «very», e.g.: The children are very happy.

(2)Most can take comparative and superlative forms. The com> parison may be by means of inflections, e.g.: «The children are happier now», «They are the happiest people I know» or by the addition of the premodifiers «more» and «most» (periphrastic comparison), e.g.: «These students are more intelligent», «They are the most beautiful paintings I have ever seen.» […]

5.4.

Adjectives can sometimes be postpositive, i.e. they can sometimes follow the item they modify. A postposed adjective (together with any complementation it may have) can usually be regarded as a re, duced relative clause.

Indefinite pronouns ending in -body, -one, -thing, -where can be modified only postpositively: I want to try on something larger (7.e,

«which is large»).

Postposition is obligatory for a few adjectives, which have a dif, ferent sense when they occur attributively or predicatively. The most common are probably «elect» («soon to take office») and «proper» («as strictly defined»), as in: «the president elecf «the City of . don proper». In several compounds (mostly legal or quasi-legal) the adjective is postposed, the most common being: attorney general, body politic, court martial, heir apparent, notary public (AmE), postmaster general.

Postposition (in preference to attributive position) is usual for a few a-adjectives and for «absent», «present», «concerned», «involved», which normally do not occur attributively in the relevant sense:

The house ablaze is next door to mine. The people involved were not found.

Some postposed adjectives, especially those ending in «-able» or «-ible», retain the basic meaning they have in attributive position but convey the implication that what they are denoting has only a temporary application. Thus, the star visible refers to stars that are visible at a time specified or implied, while the visible stars refers to a category of stars that can (at appropriate times) be seen.

15*

: PRESSI ( HERSON )

Соседние файлы в папке Теорграмматика

- #

18.03.201516.06 Mб72haymovich(2).pdf

- #

- #

- #

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

An adverb is a word or an expression that generally modifies a verb, adjective, another adverb, determiner, clause, preposition, or sentence. Adverbs typically express manner, place, time, frequency, degree, level of certainty, etc., answering questions such as how, in what way, when, where, to what extent. This is called the adverbial function and may be performed by single words (adverbs) or by multi-word adverbial phrases and adverbial clauses.

Adverbs are traditionally regarded as one of the parts of speech. Modern linguists note that the term «adverb» has come to be used as a kind of «catch-all» category, used to classify words with various types of syntactic behavior, not necessarily having much in common except that they do not fit into any of the other available categories (noun, adjective, preposition, etc.) [1]

Functions[edit]

The English word adverb derives (through French) from Latin adverbium, from ad- («to»), verbum («word», «verb»), and the nominal suffix -ium. The term implies that the principal function of adverbs is to act as modifiers of verbs or verb phrases.[2] An adverb used in this way may provide information about the manner, place, time, frequency, certainty, or other circumstances of the activity denoted by the verb or verb phrase. Some examples:

- She sang loudly (loudly modifies the verb sang, indicating the manner of singing)

- We left it here (here modifies the verb phrase left it, indicating place)

- I worked yesterday (yesterday modifies the verb worked, indicating time)

- You often make mistakes (often modifies the verb phrase make mistakes, indicating frequency)

- He undoubtedly did it (undoubtedly modifies the verb phrase did it, indicating certainty)

Adverbs can also be used as modifiers of adjectives, and of other adverbs, often to indicate degree. Examples:

- You are quite right (the adverb quite modifies the adjective right)

- She sang very loudly (the adverb very modifies another adverb – loudly)

They can also modify determiners, prepositional phrases,[2] or whole clauses or sentences, as in the following examples:

- I bought practically the only fruit (practically modifies the determiner the in the noun phrase, «the only fruit» wherein «only» is an adjective)

- She drove us almost to the station (almost modifies the prepositional phrase to the station)

- Certainly we need to act (certainly modifies the sentence as a whole)

Adverbs thus perform a wide range of modifying functions. The major exception is the function of modifier of nouns, which is performed instead by adjectives (compare she sang loudly with her loud singing disturbed me; here the verb sang is modified by the adverb loudly, whereas the noun singing is modified by the adjective loud). However, because some adverbs and adjectives are homonyms, their respective functions are sometimes conflated:

- Even numbers are divisible by two

- The camel even drank.

The word «even» in the first sentence is an adjective, since it is a prepositive modifier that modifies the noun «numbers». The word «even» in the second sentence is a prepositive adverb that modifies the verb «drank.»

Although it is possible for an adverb to precede or to follow a noun or a noun phrase, the adverb nonetheless does not modify either in such cases, as in:

- Internationally there is a shortage of protein for animal feeds

- There is a shortage internationally of protein for animal feeds

- There is an international shortage of protein for animal feeds

In the first sentence, «Internationally» is a prepositive adverb that modifies the clause, «there is …» In the second sentence, «internationally» is a postpositive adverb that modifies the clause, «There is …» By contrast, the third sentence contains «international» as a prepositive adjective that modifies the noun, «shortage.»

Adverbs can sometimes be used as predicative expressions; in English, this applies especially to adverbs of location:

- Your seat is there.

- Here is my boarding pass (wherein «boarding pass» is the subject and «here» is the predicate in a syntax that entails a subject-verb inversion).

When the function of an adverb is performed by an expression consisting of more than one word, it is called an adverbial phrase or adverbial clause, or simply an adverbial.

Formation and comparison[edit]

In English, adverbs of manner (answering the question how?) are often formed by adding -ly to adjectives, but flat adverbs (such as in drive fast, drive slow, and drive friendly) have the same form as the corresponding adjective. Other languages often have similar methods for deriving adverbs from adjectives (French, for example, uses the suffix -ment), or else use the same form for both adjectives and adverbs, as in German and Dutch, where for example schnell or snel, respectively, mean either «quick» or «quickly» depending on the context. Many other adverbs, however, are not related to adjectives in this way; they may be derived from other words or phrases, or may be single morphemes. Examples of such adverbs in English include here, there, together, yesterday, aboard, very, almost, etc.

Where the meaning permits, adverbs may undergo comparison, taking comparative and superlative forms. In English this is usually done by adding more and most before the adverb (more slowly, most slowly), although there are a few adverbs that take inflected forms, such as well, for which better and best are used.

For more information about the formation and use of adverbs in English, see English grammar § Adverbs. For other languages, see § In specific languages below, and the articles on individual languages and their grammars.

Adverbs as a «catch-all» category[edit]

Adverbs are considered a part of speech in traditional English grammar, and are still included as a part of speech in grammar taught in schools and used in dictionaries. However, modern grammarians recognize that words traditionally grouped together as adverbs serve a number of different functions. Some describe adverbs as a «catch-all» category that includes all words that do not belong to one of the other parts of speech.[3]

A logical approach to dividing words into classes relies on recognizing which words can be used in a certain context. For example, the only type of word that can be inserted in the following template to form a grammatical sentence is a noun:

- The _____ is red. (For example, «The hat is red».)

When this approach is taken, it is seen that adverbs fall into a number of different categories. For example, some adverbs can be used to modify an entire sentence, whereas others cannot. Even when a sentential adverb has other functions, the meaning is often not the same. For example, in the sentences She gave birth naturally and Naturally, she gave birth, the word naturally has different meanings: in the first sentence, as a verb-modifying adverb, it means «in a natural manner», while in the second sentence, as a sentential adverb, it means something like «of course».

Words like very afford another example. We can say Perry is very fast, but not Perry very won the race. These words can modify adjectives but not verbs. On the other hand, there are words like here and there that cannot modify adjectives. We can say The sock looks good there but not It is a there beautiful sock. The fact that many adverbs can be used in more than one of these functions can confuse the issue, and it may seem like splitting hairs to say that a single adverb is really two or more words that serve different functions. However, this distinction can be useful, especially when considering adverbs like naturally that have different meanings in their different functions. Rodney Huddleston distinguishes between a word and a lexicogrammatical-word.[4]

Grammarians find difficulty categorizing negating words, such as the English not. Although traditionally listed as an adverb, this word does not behave grammatically like any other, and it probably should be placed in a class of its own.[5][6]

In languages[edit]

- In Dutch adverbs have the basic form of their corresponding adjectives and are not inflected (though they sometimes can be compared).

- In German the term Adverb is defined differently from its use in the English language. German adverbs form a group of uninflectable words (though a few can be compared). An English adverb which is derived from an adjective is arranged in German under the adjectives with adverbial use in the sentence. The others are also called adverbs in the German language.

- In Scandinavian languages, adverbs are typically derived from adjectives by adding the suffix ‘-t’, which makes it identical to the adjective’s neuter form. Scandinavian adjectives, like English ones, are inflected in terms of comparison by adding ‘-ere’/’-are’ (comparative) or ‘-est’/’-ast’ (superlative). In inflected forms of adjectives, the ‘-t’ is absent. Periphrastic comparison is also possible.

- In most Romance languages, many adverbs are formed from adjectives (often the feminine form) by adding ‘-mente’ (Portuguese, Spanish, Galician, Italian) or ‘-ment’ (French, Catalan) (from Latin mens, mentis: mind, intelligence, or suffix -mentum, result or way of action), while other adverbs are single forms which are invariable. In Romanian, almost all adverbs are simply the masculine singular form of the corresponding adjective, one notable exception being bine («well») / bun («good»). However, there are some Romanian adverbs built from certain masculine singular nouns using the suffix «-ește», such as the following ones: băieț-ește (boyishly), tiner-ește (youthfully), bărbăt-ește (manly), frăț-ește (brotherly), etc.

- Interlingua also forms adverbs by adding ‘-mente’ to the adjective. If an adjective ends in c, the adverbial ending is ‘-amente’. A few short, invariable adverbs, such as ben («well»), and mal («badly»), are available and widely used.

- In Esperanto, adverbs are not formed from adjectives but are made by adding ‘-e’ directly to the word root. Thus, from bon are derived bone, «well», and bona, «good». See also: special Esperanto adverbs.

- In Hungarian adverbs are formed from adjectives of any degree through the suffixes -ul/ül and -an/en depending on the adjective: szép (beautiful) → szépen (beautifully) or the comparative szebb (more beautiful) → szebben (more beautifully)

- Modern Standard Arabic forms adverbs by adding the indefinite accusative ending ‘-an’ to the root: kathiir-, «many», becomes kathiiran «much». However, Arabic often avoids adverbs by using a cognate accusative followed by an adjective.

- Austronesian languages generally form comparative adverbs by repeating the root (as in WikiWiki) as with the plural noun.

- Japanese forms adverbs from verbal adjectives by adding /ku/ (く) to the stem (haya- «swift» hayai «quick/early», hayakatta «was quick», hayaku «quickly») and from nominal adjectives by placing /ni/ (に) after the adjective instead of the copula /na/ (な) or /no/ (の) (rippa «splendid», rippa ni «splendidly»). The derivations are quite productive, but for a few adjectives, adverbs may not be derived.

- In the Celtic languages, an adverbial form is often made by preceding the adjective with a preposition: go in Irish or gu in Scottish Gaelic, meaning ‘until’. In Cornish, yn is used, meaning ‘in’.

- In Modern Greek, an adverb is most commonly made by adding the endings <-α> or <-ως> to the root of an adjective. Often, the adverbs formed from a common root using each of these endings have slightly different meanings. So, <τέλειος> (<téleios>, meaning «perfect» and «complete») yields <τέλεια> (<téleia>, «perfectly») and <τελείως> (<teleíos>, «completely»). Not all adjectives can be transformed into adverbs by using both endings. <Γρήγορος> (<grígoros>, «swift») becomes <γρήγορα> (<grígora>, «swiftly»), but not normally *<γρηγόρως> (*<grigóros>). When the <-ως> ending is used to transform an adjective whose stress accent is on the third syllable from the end, such as <επίσημος> (<epísimos>, «official»), the corresponding adverb is accented on the second syllable from the end; compare <επίσημα> (<epísima>) and <επισήμως> (<episímos>), which both mean «officially». There are also other endings with particular and restricted use as <-ί>, <-εί>, <-ιστί>, etc. For example, <ατιμωρητί> (<atimorití>, «with impunity») and <ασυζητητί> (<asyzitití>, «indisputably»); <αυτολεξεί> (<aftolexí> «word for word») and <αυτοστιγμεί> (<aftostigmí>, «in no time»); <αγγλιστί> [<anglistí> «in English (language)»] and <παπαγαλιστί> (<papagalistí>, «by rote»); etc.

- In Latvian, an adverb is formed from an adjective by changing the masculine or feminine adjective endings -s and -a to -i. «Labs», meaning «good», becomes «labi» for «well». Latvian adverbs have a particular use in expressions meaning «to speak» or «to understand» a language. Rather than use the noun meaning «Latvian/English/Russian», the adverb formed from these words is used. «Es runāju latviski/angliski/krieviski» means «I speak Latvian/English/Russian» or, literally, «I speak Latvianly/Englishly/Russianly». If a noun is required, the expression used means literally «language of the Latvians/English/Russians», «latviešu/angļu/krievu valoda».

- In Russian, and analogously in Ukrainian and some other Slavic languages, most adverbs are formed by removing the adjectival suffixes «-ий» «-а» or «-е» from an adjective, and replacing them with the adverbial «-о». For example, in Ukrainian, «швидкий», «гарна», and «смачне» (fast, nice, tasty) become «швидко», «гарно», and «смачно» (quickly, nicely, tastily), while in Russian, «быстрый», «хороший» and «прекрасный» (quick, good, wonderful) become «быстро», «хорошо», «прекрасно» (quickly, well, wonderfully). Another wide group of adverbs are formed by gluing a preposition to an oblique case form. In Ukrainian, for example, (до onto) + (долу bottom) → (додолу downwards); (з off) + (далеку afar) → (здалеку afar-off) . As well, note that adverbs are mostly placed before the verbs they modify: «Добрий син гарно співає.» (A good son sings nicely/well). There is no specific word order in East Slavic languages.

- In Korean, adverbs are commonly formed by replacing the -다 ending of the dictionary form of a descriptive verb with 게. So, 쉽다 (easy) becomes 쉽게 (easily). They are also formed by replacing the 하다 of some compound verbs with 히, e.g. 안녕하다 (peaceful) > 안녕히 (peacefully).

- In Turkish, the same word usually serves as adjective and adverb: iyi bir kız («a good girl»), iyi anlamak («to understand well).

- In Chinese, adverbs are not a separate class. Adjectives become adverbs when they are marked by an adverbial suffix, for example 地 de(e.g., 孩子們快樂地唱歌 haizimen kuaile.de changge ‘the children happily sing a song’), or when adjectives are preceded by a verbal suffix such as 得 (e.g., 她說漢語說得很好 ta shuo hanyu shuo.de henhao ‘she speaks Chinese very well’).

- In Persian, many adjectives and adverbs have the same form such as «خوب», «سریع», «تند» so there is no obvious way to recognise them out of context. The only exceptions are Arabic adverbs with a «اً» suffix such as «ظاهراً» and «واقعاً».

See also[edit]

- Flat adverb (as in drive fast, drive slow, drive friendly)

- Category:Adverbs by type

- Prepositional adverb

- Pronominal adverb

- Grammatical conjunction

References[edit]

- ^ For example: Thomas Edward Payne, Describing Morphosyntax: A Guide for Field Linguists, CUP 1997, p. 69.

- ^ a b Rodney D. Huddleston, Geoffrey K. Pullum, A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar, CUP 2005, p. 122ff.

- ^ For example: Thomas Edward Payne, Describing Morphosyntax: A Guide for Field Linguists, CUP 1997, p. 69.

- ^ Huddleston, Rodney (1988). English Grammar: An Outline. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-521-32311-8.

- ^ Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads—a cross linguistic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Haegeman, Liliane. 1995. The syntax of negation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ernst, Thomas. 2002. The syntax of adjuncts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jackendoff, Ray. 1972. Semantic Interpretation in Generative Grammar. MIT Press,

External links[edit]

Look up adverb in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- The Online Dictionary of Language Terminology