Just like many words in the English language, the word ”very” also serves a double function. It can be used as an adverb or an adjective depending on the context.

- Adverb

This word is categorized as an adverb if it is used to modify a verb, an adjective, or another adverb in a particular sentence. Furthermore, this adverb is typically used to emphasize that something is of a high degree or intensity. For instance, in the sample sentence below:

She worked very quickly.

The word “very” is considered as an adverb because it modifies another adverb “quickly.”

Definition:

a. to a great degree

- Example:

- It is the very best store in the city.

- Adjective

There are also other times wherein the word “very” is considered as an adjective because it can modify a noun. When used as an adjective, this word typically means “exact” or “precise.” Take for example, the sentence:

Those were her very words.

The word “very” is categorized under adjectives because it describes the noun “words.”

Definition:

a. actual; precise

- Example:

- I found it at the very heart of the city.

b. being the same one

- Example:

- That is the very woman you were looking for.

c. emphasizing an extreme point in time or space

- Example:

- I knew it from the very beginning of the movie.

It’s an adverb because it modifies an adjective — adverbs modify anything that isn’t a noun. In this case, the adjective is ‘good’. Very can be used as an adjective, however, in such phrases as ‘the very soul of man’; here it lends weight to the noun.

answered May 28, 2016 at 21:10

AngelosAngelos

3913 silver badges14 bronze badges

3

«Very» is acting as an adverb in your sentence because it is describing the adjective «good.»

An adjective describes something.

You can’t say, «Questlove is a very drummer,» so you see it cannot act as an adjective in this sentence.

A good rule of thumb is to put a noun right after the word you are wondering is an adjective. If it makes sense, it’s most likely an adjective.

Hope this helps you. =)

answered May 29, 2016 at 4:19

Quiz Answer Key and Fun Facts

1. «Kate used to be a journalist five years ago.»

What part of speech is the best fit for the word «five»?

2. «Sharon, Kate and Meghan are very tired of filling out job applications!»

What part of speech is the word «very»?

3. «Joanne wanted to go on the ride, but she was just too scared.»

What part of speech is the word «but»?

4. Fill in the blank with the correct word: «I» or «me.»

«It was a very difficult evening for Tom and _____.»

5. Fill in the blank with the correct word: «I» or «me.»

Lauren and _________ are going to Kristen’s graduation party on Thursday.

6. Fill in the blank with the correct word: «I» or «me.»

«Joanne made cookies for Benny and _____.»

7. Which word is a linking verb (otherwise known as an auxiliary verb, verbal auxiliary, passive verb or helping verb) in the following sentences?

«My dog is so happy to see me when I get home. He runs and jumps all over the place!»

8. Which word is the action (otherwise known as dynamic) verb in the following sentences?

«The rain pours down in Pittsburgh. It is annoying at times.»

9. Select the appropriate possessive noun.

«My ______________ condo is right by the beach.»

10. Which word is a preposition?

«It would be difficult for her to stop eating chocolate.»

11. Can you pick the correct usage for the sentence?

«____________ driving me crazy!»

12. Here’s a straightforward one for you — all you have to do is pick the noun!

«My pony is extremely antsy!»

13. Now, select the proper noun in the sentence.

«She hated the way Mr. Vallimont taught math.»

14. Now that you’ve been through some basic grammar, tell me which word is used incorrectly in the following sentence.

«I don’t even know who’s house this is. Where am I supposed to park?»

15. Same deal for your last question: Which word is used incorrectly in the following sentence?

«Jared’s graduation is only a day away, and I haven’t purchased my own nephews gift!»

Source: Author YeuxdelaMere

This quiz was reviewed by FunTrivia editor CellarDoor before going online.

Any errors found in FunTrivia content are routinely corrected through our feedback system.

Содержание

- Имя существительное

- Имя прилагательное

- Глагол

- Наречие

- Местоимение

- Числительные

- Cоюз

- Предлоги

- Артикли

- Частицы

- Междометия

- Сводная таблица частей речи в английском языке

Так уж сложилось, что издавна во всех языках словообразование играло одну из первостепенных ролей. Обозначение разных частей речи и их название стало неким этапом в эволюции языка и языкознания.

Также как и в современном русском языке, каждое слово в английском принадлежит определенной части речи (part of speech), то есть категории слов, обладающих своими характерными признаками.

Part of speech — one of the grammatical groups, such as noun, verb, and adjective, into which words are divided depending on their use

Английские части речи классифицируются по синтаксической функции, грамматическому значению и форме. Следовательно, существуют самостоятельные (notional) и служебные (functional) части речи. Но в отличие от русского языка, в английском есть «переходные зоны» между частями речи. То есть одно и то же слово может выступать в роли разных частей речи. И в данном случае опорой служит сам контекст, а не форма слова.

Распознавание или предугадывание частей речи по контексту очень важный навык, если вы готовитесь к сдаче ЕГЭ или международных экзаменов. Понимание частей речи, безусловно, облегчит выполнение заданий в разы, а хорошая система подготовки определенно сыграет свою роль. В качестве помощи команда онлайн-школы Инглиш Шоу разработала курсы по подготовке к разнообразным экзаменам, начиная с ЕГЭ и заканчивая TOEFL или IELTS. Узнать, как это работает очень просто – стоит только записаться на бесплатный пробный урок и проверить эффективность обучения с преподавателем на себе!

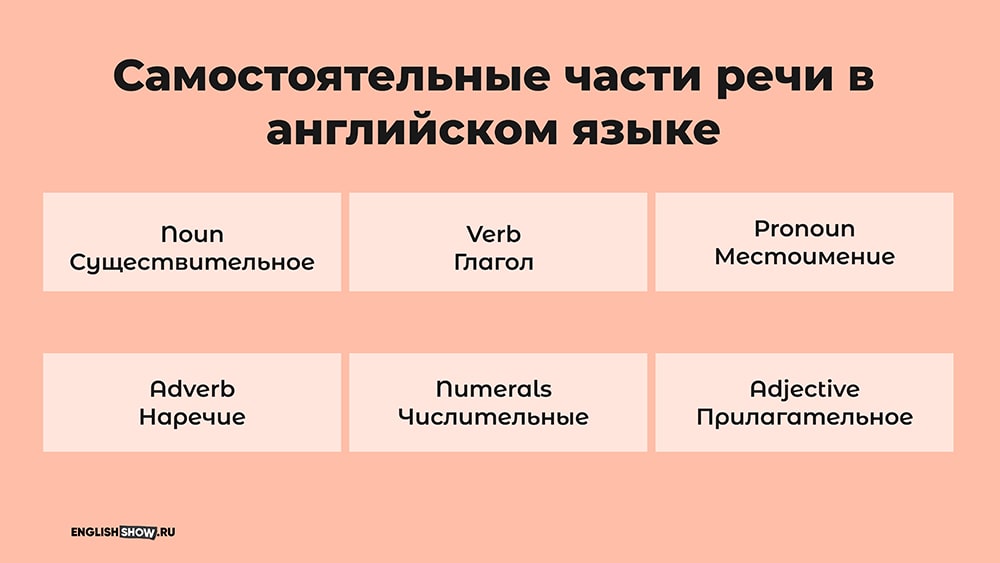

Самостоятельные части речи в английском языке

Если у слова есть свое собственное лексическое значение, то его без сомнений можно отнести к самостоятельным частям речи. Произнося его, сразу становится понятен смысл слова. К самостоятельным частям речи в английском языке относятся:

Имя существительное (Noun)

Грамматика и теория русского языка даёт нам следующее определение существительного: оно называет людей, животных, места, абстрактные понятия, предметы. И для него характерно отвечать на вопросы: «Кто?» или «Что?».

В английском существительные бывают разные:

-

Common – нарицательные

Например: person – человек, teacher – учитель, log – бревно -

Proper – собственные

Например: Stephen, Italy, America, Saturn -

Compound – составные (состоящими из двух корней)

Например: post office – почтовое отделение, car park – парковка, textbook – учебник, bookcase – книжный шкаф -

Abstract – абстрактные

Например: beauty – красота, intelligence – ум, democracy – демократия -

Collective – собирательные

Например: family – семья, flock — стая, herd – стадо

Кроме этого, в английском есть четкое разделение на исчисляемые (countable) и неисчисляемые (uncountable). Исчисляемые они потому что их можно посчитать поштучно и все они имеют форму как единственного, так и множественного числа. И перед существительным в единственном числе мы ставим артикль (a/an).

Например:

-

I have got an orange and a banana.

У меня есть апельсин и банан. -

There are a lot of cookies in this bowl.

В этой тарелке много печенья.

Стоит отметить, что к неисчисляемым существительным в основном относятся жидкости, сыпучие продукты, абстрактные понятия или те, которые существуют либо только в единственном, либо во множественном числе.

Например:

-

I don’t have much money.

У меня немного денег. -

I like listening rock music.

Я люблю слушать рок музыку. -

There is some rice in the bowl.

В тарелке есть немного риса. -

Give me some information upon this case.

Предоставь мне информацию по этому случаю.

Существительные в английском образуются с помощью определенных суффиксов, по которым вы легко сможете определить эту часть речи:

- ance: disturbance, relevance

- ence: reference, occurrence

- ity: complexity, scarcity

- ment: disappointment, achievement

- acy/cy: accuracy

- age: percentage, breakage

- an: Russian, American

- dom: kingdom, freedom

- hood: motherhood, brotherhood

В предложении эта часть речи может выполнять функции как подлежащего (subject), дополнения (object) или функцию complement (дополнения) внутри именного сказуемого.

Например:

-

We have accepted the invitation for the party.

(We – subject; invitation – object)

Мы приняли приглашение на вечеринку.

Вне всяких сомнений, существует ещё множество других нюансов, которые необходимо знать о существительных. Например, важно правильно образовывать множественное число. Об этом мы рассказывали в ролике:

Имя прилагательное (Adjective)

Мы используем прилагательные для описания существительных, то есть они характеризуют признаки предмета, человека или события. И отвечают на вопросы: «Какая?», «Какие?» и т.д.

В английском прилагательные подразделяются по степеням сравнения и бывают:

- Положительной степени (Positive form)

- Сравнительной степени (Comparative form)

- Превосходной степени (Superlative form)

Например:

-

large – larger – the largest

большой – больше – самый большой

Более подробно со всеми правилами эта тема разобрана в нашей статье 👉 Степени сравнения прилагательных

Очень часто в предложении можно встретить описание из нескольких прилагательных, в таком случае они расположены в определенном порядке:

judgement – size – shape – age – colour – origin – material – purpose – noun

суждение – размер – форма – возраст – цвет – происхождение – материал – цель – существительное

💡 Чтобы было легче запомнить, ловите подсказку: чем прилагательное субъективнее, тем дальше оно от самого существительного.

Например:

-

There is a small, old, blue, plastic table.

Это маленький, старый, голубой, пластиковый стол. -

I am a short, young, blue-eyed person.

Я молодой человек среднего роста с голубыми глазами.

Глагол (Verb)

Как мы помним со школьной скамьи, глагол – это слово «действие», которое характеризуется вопросами: «Что делать?», «Что сделать?» и так далее.

Вместе с подлежащим он представляет главные члены предложения и образует грамматическую основу.

Классификация глаголов в английском:

- Semi-auxiliary – служебные

- Auxiliary — вспомогательные

- Notional – смысловые

Также очень важным моментом является то, что в английском глаголы подразделяют на:

-

Transitive – переходные (за которым следует объект или дополнение)

She is cooking the dinner.

Она готовит обед. -

Intransitive – непереходные (которые не требуют после себя какого-либо дополнения, они просто характеризуют само действие)

He slept late this morning.

Он спал допоздна этим утром.

Ну и конечно же глаголы могут быть разных форм:

-

Infinitive – инфинитив или неопределенная форма глагола, в английском используется с частичкой to. Если без неё, то это будет форма bare infinitive (голый инфинитив).

Например: to go – идти, to cry – плакать, to unearth – раскопать

- Base form – первоначальная форма, это тот же инфинитив, но используемый уже без частички to.

-

Past Simple form – форма прошедшего времени

И здесь стоит сказать, что существуют правильные (regular) и неправильные (irregular) глаголы.

Неправильные глаголы собраны в таблицу и их просто нужно выучить для правильного употребления в речи. А правильные глаголы образуют форму прошедшего времени путем добавления -ed.

-

Past Participle – причастие прошедшего времени, это третий столбик в таблице неправильных глаголов.

Примеры: beaten – побитый, broken — сломанный

Или если глагол правильный, то он образует вторую и третью формы с помощью окончания -ed.

Примеры: play — played, study — studied, watch — watched

-

Present Participle – причастие настоящего времени, это глагол с -ing или как его ещё называют — герундий.

Например: hoping- надеющийся, studying – обучающийся

Наречие (Adverb)

В целом, наречия в отличие от прилагательных характеризуют действия или глаголы и отвечают на вопросы: «Как?», «Где?», «Когда?», «Почему?», «Каким образом?».

Классификация наречий:

-

Manner – наречие образа действия:

Well – хорошо, slowly — медленно -

Place – места:

Above – над, here – здесь -

Time – времени:

Now – сейчас, then – тогда, soon – вскоре -

Degree – степени:

Very – очень, really – реально, quite – достаточно -

Frequency – частоты:

Once – однажды, twice – дважды

В основном наречия образуются с помощью суффикса -ly, который так сказать «определитель» для этой части речи, но, как вы заметили, исключения всегда имеют место быть.

Местоимение (Pronoun)

Судя по названию, местоимения мы используем вместо имён, то есть вместо имён собственных, предметов или качеств предмета.

В английском языке существуют следующие классы местоимений:

-

Object pronouns – личные, выступающие в роли объекта: me, him, her, it, us, you, them

He met me at the park yesterday.

Он встретил меня вчера в парке. -

Subject pronouns – личные, выступающие в роли субъекта: I, he, you, she, we, it, they

They used to play tennis 10 years ago.

Они имели обыкновение играть в теннис 10 лет назад. -

Reflexive pronouns – возвратные: himself, herself, ourselves, myself

We decided to do it by ourselves.

Мы решили это сделать сами. -

Demonstrative pronouns – указательные: those, this, that, these

These are your pieces of equipment.

Вот это твоё оборудование. -

Possessive pronouns – притяжательные: hers, his, mine, yours

These shoes are mine!

Это мои туфли! -

Relative pronouns – относительные: who, which, that, whose

This was the man who stole your wallet.

Это тот мужчина, который украл у тебя кошелёк.

Числительные (Numerals)

Числительные показывают порядок предметов при счете и их количество. Для них характерными являются вопросы: «Сколько?» или «Который по счету?». Также, как и в русском языке, они бывают:

-

Cardinal numbers – количественными:

one, six, thirty, one hundred -

Ordinal numbers – порядковыми:

first – первый, second – второй, third – третий, fourth – четвертый

Образование порядковых числительных происходит с помощью окончания -th, начиная с числа 4, а первые три числа нужно просто запомнить.

Служебные части речи в английском языке

Исходя из названия можно догадаться, что служебные части речи выполняют вспомогательную функцию и, так сказать, служат самостоятельным частям речи.

Служебных частей речи не так уж много:

- Article – артикль

- Conjunction – союз

- Preposition – предлог

- Paticles — частицы

- Interjections — междометия

Cоюз (Сonjunction)

Союзы служат соединительными словами-связками, это своего рода взаимодействие однородных членов предложения. Или же они выполняют роль соединения предложений между собой.

-

Conjunctions for words of the same class (Союзы для однородных частей речи):

and, but, or, nor, yet -

Conjunctions for clauses of sentences (Союзы для частей предложения):

as soon as, before, since, until, when, because, although, unless, so, where

Предлоги (Prepositions)

Как правило, предлоги показывают отношение существительного или местоимения к другим словам в предложении. Существуют такие категории, как:

-

Place – предлоги места:

in, at, on, by, above, over -

Movement – предлоги движения:

from, to, in, into, on, onto, by, out, through -

Time – предлоги времени:

at, on, by, before, in, from, since, during, until

Сложность выбора предлогов заключается в том, что нет строгой однозначности в их использовании. Поэтому хорошим советом здесь будет: Practise, practise & practise! Подробнее про предлоги места и времени читайте в нашей статье: predlogi-mesta-i-vremeni

Артикли (Аrticles)

В английском существует всего лишь два типа артиклей, по сравнению с другими романо-германскими языками, в которых их гораздо больше.

-

Definite article – определенный артикль – the

Используется в том случае, если субъект или объект являются определенными по ситуации или единственными в своем роде.

Например:

The football is blue.

Мячик является голубым. (Именно конкретный мячик)The sun is shining brightly.

Солнце ярко светит. (Единственное в своем роде – the sun) -

Indefinite article – неопределенный артикль – a/an

Данный артикль может употребляться только с исчисляемыми существительными и в единственном числе. То есть он просто служит неким обозначением предмета в единственном числе. Поэтому нужно быть предельно внимательными при его использовании.

Например:

A lotus is a flower.

Лотус – это цветок.

Более подробно про артикли читайте в нашей следующей статье: artikli-v-anglijskom-jazyke

Частицы (Paticles)

Частицы имеют свойство придавать словам дополнительные оттенки, значение. Они не имеют грамматических категорий, а также не являются членами предложения. Давайте посмотрим, какие же существуют классификации частиц:

-

Limiting — выделительно-ограничительные:

even, only, merely, solely, just, but, alone -

Intensifying particles – усилительные:

simply, just, all, still, yet -

Negative particle — отрицательная частица:

not -

Additive particle — дополняющая частица:

else

Междометия (Interjections)

Междометия на самом деле не относятся ни к самостоятельным, ни к служебным частям речи, так как они не имеют особого смысла. Они лишь передают наши чувства и эмоции.

Например:

oh, eh, alas, er, hey, uhm

Сводная таблица частей речи в английском языке

| PARTS OF SPEECH | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|---|

| NOUNS | Name people, animals, places, things | Chair, sparrow, school, Greece |

| VERBS | Name action or activity | Be, seem, smell, jump |

| ADJECTIVES | Describe nouns such as people or things | Clean/dirty, expensive/cheap, light/dark |

| ADVERBS | Describe verbs (actions) | Well, quickly, sometimes |

| PRONOUNS | Used instead of nouns | He, we, they, their, my |

| NUMERALS | Name numbers | Fifty, eighty, thirty-first |

| CONJUNCTIONS | Join words or clauses of sentence | And, but, as soon as, unless, although |

| PREPOSITIONS | Show the relationship between a noun and other words | At, on, by, before, since |

| ARTICLES | Show if the noun is definite or indefinite | The, a/an |

| PARTICLES | Give additional meaning to words | Not, yet, else |

| INTERJECTIONS | Describe feelings and emotions | Oh, eh, alas, er, hey, uhm |

Эта таблица поможет вам определять части речи. Также, используя русско-английский словарь, вы можете посмотреть принадлежность слова к той или иной части речи. Но, чтобы начать лучше разбираться в грамматических аспектах, лучше начать изучение последовательно, к примеру, с глаголов и потом постепенно переходить к другим самостоятельным или служебным частям речи. Тогда вы сможете с легкостью выдохнуть — у вас не будет никакой каши в голове и сложностей в использовании на практике.

Также не стоит забывать, что построение английского предложения начинается с прямого порядка слов, о чем многие забывают при переключении с русского на английский. Как раз для подобного рода практики команда Инглиш Шоу разработала курс Разговорный Марафон. Каждый день на протяжении нескольких месяцев вы отрабатываете основные навыки, разговаривая на повседневные темы с разными преподавателями. Но это ещё не все! В течение курса вас ждёт масса сюрпризов и лайфхаков, так что после курса можете с уверенностью собираться заграницу! Записывайтесь на бесплатный пробный урок и узнайте все подробности самостоятельно.

AN-244

Phrasal Syntax

seminar

Marosán Lajos

Parts of Speech

Tarr Dániel

1995

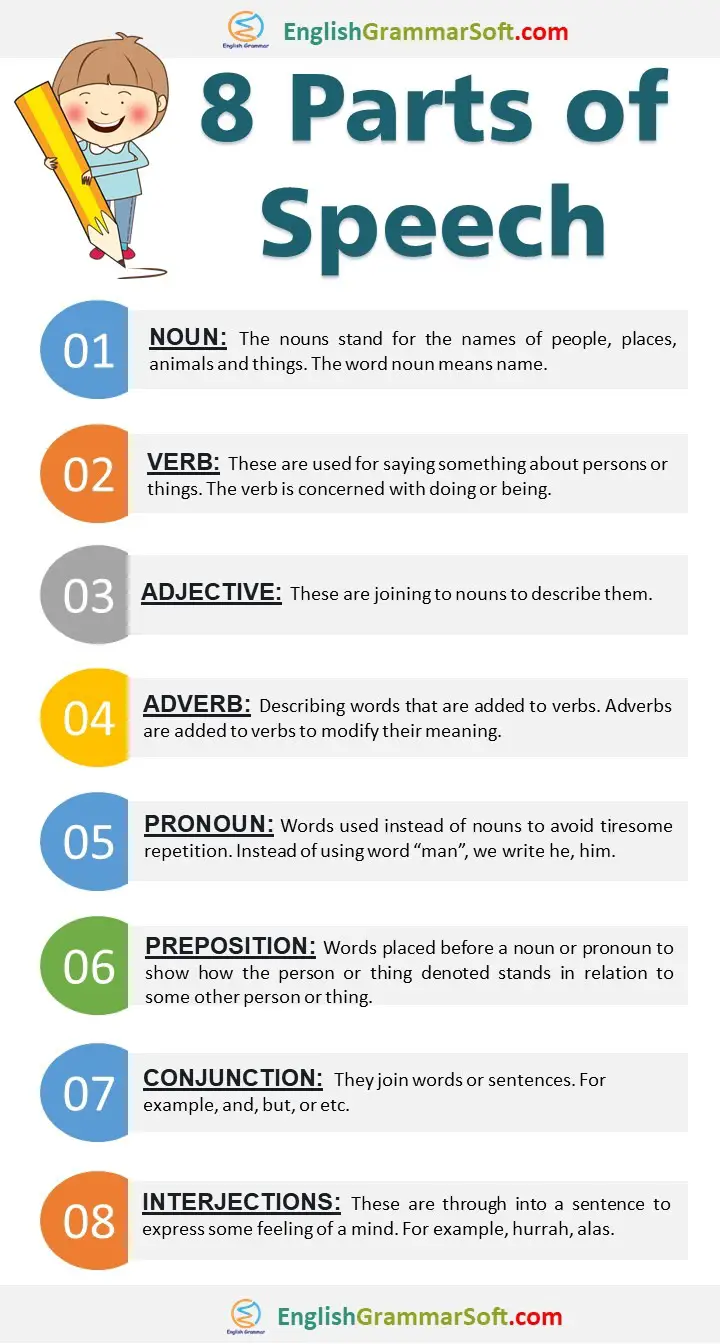

Parts of Speech

Parts

of Speech are words classified

according to their functions in sentences, for purposes of traditional

grammatical analysis. According to traditional grammars eight parts of speech

are usually identified: nouns, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions,

pronouns, verbs, and interjections.

Noun girl, man, dog,

orange, truth …

Pronoun I, she, everyone,

nothing, who …

Verb be, become,

take, look, sing …

Adjective small, happy, young,

wooden …

Adverb slowly, very,

here, afterwards, nevertheless

Preposition at, in, by, on, for,

with, from, to …

Conjunction and, but, because,

although, while …

Interjection ouch, oh, alas, grrr,

psst …

Most

of the major language groups spoken today, notably the Indo-European languages

and Semitic languages, use almost the identical categories; Chinese, however,

has fewer parts of speech than English.[1]

The

part of speech classification is the center of all traditional grammars.

Traditional grammars generally provide short definitions for each part of

speech, while many modern grammars, using the same categories, refer to them as

“word-classes” or “form-classes”. To preface our discussion, we will do the

same:

Nouns

A noun

(Latin nomen, “name”) is usually defined as a word denoting a thing, place,

person, quality, or action and functioning in a sentence as the subject or

object of action expressed by a verb or as the object of a preposition. In

modern English, proper nouns, which are always capitalized and denote

individuals and personifications, are distinguished from common nouns. Nouns

and verbs may sometimes take the same form, as in Polynesian languages. Verbal

nouns, or gerunds, combine features of both parts of speech. They occur in the

Semitic and Indo-European languages and in English most commonly with words

ending in -ing.

Nouns

may be inflected to indicate gender (masculine, feminine, and neuter), number,

and case. In modern English, however, gender has been eliminated, and

only two forms, singular and plural, indicate number (how many perform or

receive an action). Some languages have three numbers: a singular form

(indicating, for example, one book), a plural form (indicating three or more

books), and a dual form (indicating, specifically, two books). English has

three cases of nouns: nominative (subject), genitive

(possessive), and objective (indicating the relationship between the

noun and other words).

Adjectives

An

adjective is a word that modifies, or qualifies, a noun or pronoun, in

one of three forms of comparative degree: positive (strong, beautiful), comparative

(stronger, more beautiful), or superlative (strongest, most beautiful).

In many languages, the form of an adjective changes to correspond with the

number and gender of the noun or pronoun it modifies.

Adverbs

An

adverb is a word that modifies a verb (he walked slowly), an adjective

(a very good book), or another adverb (he walked very slowly). Adverbs may

indicate place or direction (where, whence), time (ever,

immediately), degree (very, almost), manner (thus, and words

ending in —ly, such as wisely), and belief or doubt (perhaps,

no). Like adjectives, they too may be comparative (wisely, more wisely, most

wisely).

Prepositions

Words

that combine with a noun or pronoun to form a phrase are termed prepositions.

In languages such as Latin or German, they change the form of the noun or

pronoun to the objective case (as in the equivalent of the English

phrase “give to me”), or to the possessive case (as in the phrase “the

roof of the house”).

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are the words that connect sentences, clauses,

phrases, or words, and sometimes paragraphs. Coordinate conjunctions

(and, but, or, however, nevertheless, neither … nor) join independent clauses,

or parts of a sentence; subordinate conjunctions introduce subordinate

clauses (where, when, after, while, because, if, unless, since, whether).

Pronouns

A pronoun

is an identifying word used instead of a noun and inflected in the same way

nouns are. Personal pronouns, in English, are I, you, he/she/it, we, you

(plural), and they. Demonstrative pronouns are thus, that, and such.

Introducing questions, who and which are interrogative pronouns; when

introducing clauses they are called relative pronouns. Indefinite pronouns

are each, either, some, any, many, few, and all.

Verbs

Words

that express some form of action are called verbs. Their inflection,

known as conjugation, is simpler in English than in most other

languages. Conjugation in general involves changes of form according to person

and number (who and how many performed the action), tense (when

the action was performed), voice (indicating whether the subject of the

verb performed or received the action), and mood (indicating the frame

of mind of the performer). In English grammar, verbs have three moods: the indicative,

which expresses actuality; the subjunctive, which expresses contingency;

and the imperative, which expresses command (I walk; I might walk;

Walk!)

Certain

words, derived from verbs but not functioning as such, are called verbals.

In addition to verbal nouns, or gerunds, participles can serve as adjectives

(the written word), and infinitives often serve as nouns (to err is human).

Interjections

Interjections are exclamations such as oh, alas, ugh, or well (often

printed with an exclamation point). Used for emphasis or to express an

emotional reaction, they do not truly function as grammatical elements of a

sentence.[2]

It is useful to make a distinction and consider words as falling into two broad

categories; closed

class words and open class words. The former consists of classes that are finite (and

often small) with membership that is relatively stable and unchanging in the

language. These words play a major part in English grammar, often corresponding

to inflections in some other languages, and they are sometimes referred to as

‘grammatical words’, ‘function words’, or ‘structure words’. These terms also

stress their function in the grammatical sense, as structural markers, thus a

determiner typically signals the beginning of a noun phrase, a preposition the

beginning of a prepositional phrase, a conjunction the beginning of a clause. Closed

classes are: pronoun /she, they/, determiner /the, a/, primary

verb /be/, modal verb

/can, might/, preposition /in, of/, and conjunction /and, or/. Open classes are: noun /room, hospital/, adjective /happy, new/, full verb /grow, search/, and adverb /really, steadily/. To these two lesser

categories may be added: numerals /one, first/, and interjections /oh, aha/; and finally a small number of words

of unique function which do not easily fit into any of these classes /eg.: the negative particle not and the infinite

marker to/.

Quirk

and Greenbaum[3]point out the ambiguity of the term word, for

words are enrolled in their classes in their ‘dictionary form’, and not as they

might appear in sentences when they function as constituents of phrases. Since

words in their various grammatical forms appear in sentences that are normal

usage, it is more correct if we refer to them as lexical items. Thus, a lexical item is a word as it occurs in a

dictionary, where work, works, working, worked will all be counted as

different grammatical forms of the word work. This distinction however

is not always necessary, for it is only important with certain parts of speech

that have inflections; that is endings or modifications that change the

word-form into another. These are nouns /answer,

answers/, verbs /give, given/, pronouns /they, theirs/, adjectives

/large, largest/, and a few adverbs

/soon, sooner/ and determiners /few,

fewer/.

A word may belong to more than one class; for example round

is also a preposition /”drive round the corner”/ and an adjective

/”she has a round face”/. In such cases we can say that the same morphological form is a realization of more than one lexical item. A

morphological form may be simple, consisting of a stem only /eg.: play/,

or complex, consisting of more than one morpheme /eg.: playful/. The morphological form of a word is

therefore defined as composition of stems and affixes.

We

assign words to their various classes according to their properties in entering

phrasal or clausal structure. For example, determiners link up with nouns to

form noun phrases /eg.: a soldier/;

and pronouns can replace noun phrases /eg.:

him/. This is not to deny the general validity of traditional

definitions based on meaning. In fact it is impossible to separate grammatical

form from semantic factors. The distinction between generic /the tiger lives/ and specific /these tigers/, unmarked and marked

forms prove that.

Another

possible assignment is according to morphological characteristics, notably the

occurrence of derivational suffixes, which marks a word as a member of a

particular class. For example, the suffix -ness, marks an item as a noun

/kindness/, while the suffix -less marks an item as an adjective

/helpless/. Such indicators help to identify word classes without

semantic factors.

For

the sake of completeness, it should also be added that a word also has a phonological and an orthographic form. Words which share the same phonological or

orthographic “shape”, but are morphologically unrelated are called homonyms /eg.: rose

(noun) and rose (past tense verb)/. Words with the same pronunciation

are specified as homophones, and words with the same spelling are determined as homographs. Words which partake the same morphological form are

called homomorphs /eg.: meeting

(noun) and meeting (verb)/. There is also a correspondence between words

with different morphological form, but same meaning. These are called synonyms. Of the three major kinds of equivalence, homonymy is

phonological and/or graphic, and synonymy is semantic.

We have to go back to the distinction of closed-class items and open-class

items, because this introduces a peculiarity of great importance. That is, closed-class items are ‘closed’ in the sense that they cannot normally

be extended by the creation of additional members. For example, it is very

unlikely for a new pronoun to develop. It is also very easy to list all the

members in a closed class. These items are said to be constitute a system in

being mutually exclusive: the decision to use one item in a given structure

excludes the possibility of using any other /the book or a

book, but not *a the book/. These items are also reciprocally

defining in meaning: it is less easy to state the meaning of any individual

item than to define it in relation to the rest of the system.

By

contrast open

class items belong to a class in that

they have the same grammatical properties and structural possibilities as other

members of the class (that is, as other nouns or verbs or adjectives or

adverbs), but the class is ‘open’ in the sense that it is indefinitely

extendible. New items can be created and no inventory can be made that would be

complete. This ultimately affects the way in which we attempt to define any

item in an open class; because while it is possible to relate the meaning of a

noun to another with which it has semantic affinity /eg.: house = chamber/,

one could not define it as not house, which is possible with closed

class items /this = not that/.

However,

the distinction between ‘open’ and ‘closed’ parts of speech or word classes

must not be treated incautiously. On the on hand, it is not very easy to create

new words, and on the other, we must not overstate the extent to which we speak

of ‘closedness’, for new prepositions like by way of [4]are no means impossible. Although parts of speech have

deceptively specific labels, words tend to be rather heterogeneous. The adverb

and the verb are especially mixed classes, each having small and fairly well

defined groups of closed-system items alongside the indefinitely large

open-class items. So far as the verb is concerned, the closed-system subgroup

is known be the well established term “auxiliary”…

Some

mention must be finally made of two additional classes, numerals and interjections,

which are common in the difficulty of classifying them as either closed or open

classes. Numerals whether the cardinal numerals /one, two, three/,

or the ordinal numerals /first, second, third/, must be placed somewhere

between open-class and closed-class items: they resemble the former in that

they make up a class of infinite membership; but they resemble the latter in

that the semantic relations among them are mutually exclusive and mutually

defining. Interjections might be considered a closed class on the

grounds that those that are fully institutionalized are few in number. But

unlike the closed classes, they are grammatically peripheral — they do not

enter into constructions with other word classes, and they are only loosely

connected to sentences with which they may be orthographically or

phonologically associated.

A further and related contrast between words, is the distinction between stative

and dynamic. Broadly speaking, nouns can be characterized naturally

as ‘stative’ in that they refer to entities that are regarded as

stable, whether these are concrete /house, table/ or abstract /hope,

length/. On the other hand verbs and adverbs can equally naturally be

characterized as ‘dynamic’: verbs are fitted to indicate action, activity and

temporary or changing conditions; and adverbs in so far as they add a

particular condition of time, place, manner, etc. to the dynamic implication of

the verb.

But

it is not uncommon to find verbs which may be used either dynamically or

statively. If we say that “some specific tigers are living in a cramped

cage”, we imply that this is a temporary condition and the verb phrase is dynamic

in its use. On the other hand, when we say that “a species of animal known as

tiger lives in China”, the generic statement entails that this is not a

temporary circumstance and the verb phrase is stative. Moreover some verbs

cannot normally be used with the progressive aspect /*He is knowing English/

and therefore belong to the stative rather than the dynamic category. In

contrast to verbs, most nouns and adjectives are stative in that they denote a

phenomena or quality that is regarded for linguistic purposes as stable and

indeed for all practical purposes permanent /Jack is an engineer — Jack

is very tall/. Also adjectives can resemble verbs in referring to

transitionary conditions of behavior or activity. /He is being a nuisance

— He is being naughty/.

The names of the parts of speech are traditional, however, and neither in

themselves nor in relation to each other do these names give a safe guide to

their meaning, which instead is best understood in terms of their grammatical

properties. One fundamental relation is that grammar provides the means of

referring back to an expression without repeating it. This is achieved by means

of pro-forms. Participles and pronouns can serve

as replacements for a noun /the big

room and the small one/, more

usually, however, pronouns replace noun phrases rather than nouns /their beautiful new car was badly damaged when it was struck be a

falling tree/.

The

relationship which often obtains between a pronoun and its antecedent is not

one which can be explained by the simple act of replacement. In some

constructions we have repetition, which are by no means equivalent in meaning /Many students

did better than many students expected/. In some constructions repetition can be avoided by ellipsis /They hoped they would play a Mozart quartet and

they will/. Therefore the general term

pro-form is best applied to words and word sequences which are essentially

devices for rephrasing or anticipating the content of a neighboring expression,

often with the effect of grammatical complexity.

Such

devices are not limited to pronouns and participles: the word such can

described as a pro-form as there are pro-forms also for place, time and other

adverbials under certain circumstances /M.is

in London and J. is there too/.

In older English and still sometimes in very formal English we find thus and so

used as pro-forms for adverbials /He

often behaved silly, but he did not always behave thus/so/. But so has a more important function in

modern usage, namely to substitute with the ‘pro-verb’ do for a main

verb and whatever follows it in the clause /He

wished they would take him seriously for his ideas, but unfortunately

they didn’t do so/. Do can also

act as pro-form on its own /I told him

about it — I did too/.

Some

pro-forms can refer forward to what not been stated rather than back to what

has been stated. These are the wh-items. Indeed, wh-words,

including what, which, who and when, may be

regarded as a special set of pro-forms /Where is M.? — M. is in London. — J. is there too/. The paraphrase for wh-words is broad enough

to explain also their use in subordinate clauses /I wonder what M. thinks/. Through the use of wh-words we can ask for

the identification of subject, object, complement or adverbial of a sentence /They [S] make [V] him [O] the chairman [C] every year

[A]. — Who [S] makes him…?/.

Now that we have outlined the various aspects of Parts of Speech, according to

traditional grammars, we will look at some other approaches and other

specifications, without the sake of complexity, only to widen our views a

little more on the subject:

Otto Jespersen[5]starts out from the point that all clauses consist of

several words. One word is defined or modified by another word, which in turn

may be defined or modified by a third word. This leads to the establishment of

different ranks of words according to their mutual relations as defined or

defining. In the combination “extremely hot weather” weather may

be called a primary word or principal; hot

is a secondary word or

adjunct; and extremely is a

tertiary word or subjunct. Primary and secondary words are superior in relation to tertiary words; secondary and tertiary

words are inferior in relation to primary words. It is therefore

possible to have two or more (coordinate) adjuncts to the same principal /that

nice [A] young [A] lady [P]/.

The

logical basis of this system of subordination is the greater or lesser degree

of specialization. Primary words are more special (apply to a smaller number of individuals) than secondary

words, and these in their turn are less general than tertiary words. The word

defined by another word, is in itself always more special than the word

defining it, though the latter serves to render the former more special than it

is in itself. Thus in the sentence “very clever student”, student

is the most special idea, whereas clever can be applied to many more

men, and very, which indicates only a high degree, can be applied any

idea. Student is more special than clever, though clever

student is more special than student; clever is more special

than very, though very clever is more special than clever.

It

is a natural consequence of these definitions that proper nouns can only be

used as principals, and while there are thus some words that can only stand as

principals as expressing highly specialized ideas, there are other words that

may be either primary and secondary words in different combinations /conservative Liberals — liberal Conservatives/. Further there are words of such general signification

that they can never be used as primary words, like the articles.

His

further definitions of parts of speech fall under the categories of substantives (=principals), adjectives

(=adjuncts), adverbs (=subjuncts), verbs

(=verbs not subject to conjugation), verbids

(=participles and infinitives), predicatives (=‘mediate adjuncts’; {most commonly}a verb connecting two ideas in

such a way that the second becomes a kind of adjunct to the first (the

object)./Eg.: the rose is red/), objects (=primary words, but more special as well as more

general than the first principal /eg.: an owl sees a bird/.), and pronouns

(= a separate “parts of speech”, understood differently according to the

situation in which they are used).

Lyons[6]

starts out from distinguishing formal

and nominal definitions. Nominal definitions of the parts of

speech may be used to determine the names, though not the membership, of the

major syntactic classes of English. Creating syntactic classes on ‘formal’

distributional grounds, with all the members of each of them listed in the

lexicon, associated with the grammar, will mean that though not all members of

class X will denote persons, places and things; most of the lexical items which

refer to persons, places and things will fall within it; and if this is so we

may call X the class of nouns. In other words we have ‘formal’ class X and

‘notional’ class A; they are not co-extensive, but if A is wholly or mainly

included in X, then X may be given the label suggested by the ‘notional’ definition

of A.

He

also points out the necessity of considering the distinction between deep and

surface structure and define parts of speech not as classes of words in

surface structure, but as deep-structure constituents of sentences. The

distinction between deep and surface structures is not made explicitly in

traditional grammar, but it is implied by the assumption that all clauses and

phrases are derived from simple, modally ‘unmarked’ sentences. It is asserted

that every simple sentence is made up of two parts: a subject and a predicate. The subject is necessarily a noun (or a pronoun standing for a noun).

The predicate falls into one of three types according to the part of speech

which occurs in it: 1. intransitive verb, 2. transitive verb with its object,

3. the ‘verb to be’ with its complement. The object, like the

subject, must be a noun, while the complement must either be an adjective, or a

noun.

Deriving

from these associations with particular parts of speech it is possible to

determine traditional parts of speech or their function solely on the basis of

constituent-structure relations. The class of nouns is the one constituent

class which all sentences have in common at the highest level of constituent

structure. The class of intransitive verbs is the only class which combines

directly with nouns to form sentences. The class of transitive verbs combine

with nouns and with no other class to form predicates. Be is the

copula-class, since it combines with both nouns and the class of adjectives.

This argument rests of course on the specific assumptions incorporated in the

syntactic function of the parts of speech; namely the status of the copula or

‘verb to be’, and the universality of the distinction between verbs and

adjectives.

‘To

be’ is not itself a constituent of deep structure, but a semantically-empty

“dummy verb” generated for the specification of certain distinctions (usually

carried by the verb) when there is no other verbal element to carry these

distinctions. Sentences that are temporally, modally and aspectually unmarked

do not need the dummy carrier /M. is clever/. As for the distinction

between verbs and adjectives it is traditionally referred to as to do with the

surface phenomenon of inflection. The adjective, when it occurs in predicative

position, does not take the verbal suffixes associated with distinctions of

tense, mood and aspect, but instead a dummy verb is generated by the grammar to

carry the necessary inflexional suffixes /M. is clever — *M. is

clever-s/. The verb is less freely transformed

to the position of modifier in the noun-phrase; but when it occurs in this

syntactic position, unlike the adjective, it bears the suffix -ing /the clever man — the singing man — *the clever-ing man/. A distinction between stative verbs and verbs of action is also relevant to English. Stative verbs do not

normally occur in the progressive form, while the majority of English verbs,

which occur freely in the progressive are called verbs of action. This

aspectual difference is matched by a similar difference in English adjectives.

Most adjectives are stative, in the sense that they do not normally take

progressive aspect when they occur in predicative position /M. is clever — *M. is being clever/, but there are a number of adjectives which occur

freely with the progressive in the appropriate circumstances /M. is being silly now/. In other words, to be stative is normal for the

class of adjectives, but abnormal for the verbs; to be non-stative is normal

for verbs, but abnormal for adjectives. It is, however, the aspectual contrast

which correlates with the notional definition of the verb and the adjective in

terms of “action” and “quality”.

To follow this argument Huddleston[7]points

out that nothing said about inflection requires that all the forms of a lexeme

should belong to the same part of speech. The main problem area concerns the

traditional non-finite forms of verb lexemes, participles, the gerund and the

infinitive. A participle is said to be a “verbal adjective”, while the gerund

and the infinitive are “verbal nouns”. According to traditional doctrine, a

gerund like writing in She likes writing letters is a noun

because it is the object of the verb like. This would lead traditional

grammarians to classify together as nouns words which are syntactically very

different. /Eg.: Writing the

letters took some time — The writing of the letters took some time/. Instead of saying that both are nouns because they

are subject of took, he suggests that we call writing a verb in the

former case, because it is the head of the extended verb phrase, and call it a

noun in the latter case, because it is a head of the noun phrase. Since the

relation between this later type of noun writing and the stem write

is lexical rather than inflectional, he calls this a “deverbal noun”, for it is

derived by a lexical-morphological process from a verb stem.

The

second problem area concerns possessives. In the traditional treatment of forms

like John’s in John’s book is regarded as an inflectional form of

the noun John but is also said to have the force of an adjective. This

is easily resolved in the light of the analyses of ‘s as a clitic rather

than an inflexional suffix: John’s is not syntactically a single word,

not a form of John, so that the issue of whether a lexeme and a member

of its paradigm belong to the same parts of speech does not arise.

References

Huddleston,

R. —

Introduction to the grammar of English .

[ Cambridge University Press, 1984 ].

Jespersen,

O. —

Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles . (Vol. II.)

[ Allen and Unwin, 1954, London ].

Lyons — Introduction

to Theoretical Linguistics .

[ Cambridge University Press, 1968 ].

Mc

Cawley, J.D.

— The Syntactic Phenomena of English .

[ The University of Chicago Press, 1988 ].

Quirk

& Greenbaum

— A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language .

[Longman, 1983, London ].

Quirk

& Greenbaum

— A University Grammar of English .

[ Longman, 1973 ].

Quirk

& Greenbaum

— A Student’s Grammar of the English Language .

[ Longman, 1991 ].

Microsoft

(R) Encarta. 1994 Microsoft Corporation.

[ Funk & Wagnall’s Corp., 1994 ].

It is a fact that almost every word of English has got the capacity to be employed as a different part of speech. At one place, a particular word may be used as a noun, at another as a verb, and yet at another place as an adjective.

These words enable the learners of the English language to understand the behavior of a particular word in various positions.

Importance of Parts of Speech in Communication

As you know, English sentences are used to communicate a complete thought. The importance of parts of speech lies in their proper utilization, which can help your understanding and confidence grow immensely.

Proper usage of parts of speech means that you can impart clear messages and understand them because you know the rules of the language.

Each word in a sentence belongs to one of the eight parts of speech according to the work it is doing in that sentence. There are 8 parts of speech.

- Noun

- Verb

- Adjective

- Adverb

- Pronoun

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

1 – Noun (Naming words)

The nouns stand for the names of people, places, animals, and things. The word noun means name. Look at these sentences.

“John lives in Chicago. He has two bikes. He is fond of riding bikes.”

In the above example, John is the name. We cannot use the same name again and again in different sentences. Here, we used “he” in the next two sentences instead of “John”. “He” is called the pronoun.

Types of nouns are

1.1 – Common Noun

It describes a person, place, and thing.

Examples: City, country, town, boy.

1.2 – Proper Noun

It includes a particular person, place, thing, or idea and begins with a capital letter.

Examples: Austria, Manchester, United Kingdom, etc.

1.3 – Abstract Noun

An abstract noun describes names, ideas, feelings, emotions or qualities, the subject of any paragraph comes under this category. It does not take “the”.

Examples: grief, loss, happiness, greatness.

1.4 – Concrete Noun

It describes material things, persons or places. The existence of that thing can be physically observed.

Examples: Book, table, car, etc.

1.5 – Countable and Uncountable Noun

Countable nouns can be singular or plural. It can be counted.

Examples: Ships, cars, buses, books, etc.

The uncountable noun is neither singular nor plural. It cannot be counted.

Examples: Water, milk, juice, butter, music, etc.

1.6 – Collective Noun

It includes the group and collection

people, things or ideas. It is in unit form and is considered as singular.

Examples: Staff of office, group of visitors.

However, people and police can be

considered both singular and plural.

1.7 – Possessive Noun

It shows ownership or relationship.

Examples: Jimmy’s pen.

Further Reading: 11 Types of Nouns with Examples

2 – Verb (Saying words)

These are used for saying something

about persons or things. The verb is concerned with doing or being.

Examples

- A hare runs (action) very fast.

- Aslam is a good student.

Types of verbs

2.1 – Actions verbs

(run, move, write etc)

2.2 – Linking verbs

(to be (is, am, are, was, were), seem, feel, look, understand)

2.3 – Auxiliary (helping) verbs

(have, do, be)

2.4 – Modal Verbs

(can, could, may, might, will/shall)

2.5 – Transitive verbs

It takes an object.

Example – He is reading a newspaper.

2.6 – Intransitive verbs

It does not take the object.

Example – He awakes.

Further Reading: What are the verbs in English?

3 – Adjectives (describing words)

These are joining to nouns to describe

them.

Examples

- A hungry wolf.

- A brown wolf.

- A lazy boy.

- A tall man.

It is used before a noun and after a linking verb.

Before noun example

A new brand has been launched.

After linking verb example

Imran is rich.

It is used to clarify nouns.

Example: smart boy, blind man

Types of adjectives

3.1 – Simple degree

He is intelligent.

3.2 – Comparative

Ali is intelligent than Imran.

3.3 – Superlative

Comparison of one person with class,

country or world. In this type “the” is used.

Example: Ali is the wisest boy.

3.4 – Demonstrative adjective

It points out a noun. These are four

in number.

This That These Those

3.5 – Indefinite adjectives

It points out nouns. They often tell

“how many” or “how much” of something.

Interrogative adjectives: it is used to ask questions

Examples

- Which book?

- What time?

- Whose car?

Further Reading: More About Adjectives

4 – Adverbs

Describing words that are added to verbs. Just as adjectives are added to describe them, adverbs are added to verbs to modify their meaning. The word “modify” means to enlarge the meaning of the adverbs.

Examples

- Emma sings beautifully. (used with verb)

- Cameron is extremely clever. (used with adjective)

- This motor car goes incredibly fast. (used with another adverb)

Types of adverb

4.1 – Adverb of manner

This type of adverb deals with the

action something

Example

- I walk quickly.

- He wrote slowly.

4.2 – Adverb of place

Happening of something or the place where it happens.

Examples:

There was somebody sitting nearby.

Here, these, upstairs, nowhere everywhere, outside, in, out, are called adverb of place.

4.3 – Adverb of time

It determines the time of the happening of something.

Examples

- She went there last night.

- Have you seen him before?

- He wrote a letter yesterday.

Tomorrow, today, now, then,

yesterday, already, ago.

4.4 – Linking adverbs (then, however)

It creates a connection between two clauses or sentences.

Example

There will be clouds in Lahore. However, the sun is expected in Multan.

Note: Besides modifying the meaning of a verb, adverbs also modify adjectives and other adverbs.

Examples

- It is a very large house.

- He is too weak to walk.

- He ran too fast.

Further Reading: 11 Types of Adverbs with Examples

5 – Pronouns

Words that are used instead of nouns to avoid tiresome repetition. Instead of using the word man in a composition, we often write he, him, himself. In place of the word “woman”, we write she, her, or herself. For both the nouns ‘men’ and ‘women’ we use, they, them, themselves.

Some of the most common pronouns are

Singular: I, he, she, it, me, him,

her

Plural: We, they, out, us, them.

Examples

Imran was hurt. He didn’t panic.

He checked the mobile. It still

worked.

Types of Pronouns

It stands instead of persons. They have different forms according to the person who is supposed to be speaking.

First person: I, we, me, us, mine, our, ourselves.

Second person: thou, you, there.

Third person: He, she, it, his, him

5.1 – Possessive pronouns

Such as mine, ours, yours, hers and theirs.

- This book is mine.

- My horse and yours are tired.

5.2 – Relative pronoun

Who, whom, which and they are called relative pronouns. They are called relative because they relate to some word in the main clause. The word to which pronoun relates is called the antecedent.

Example

I saw a boy who was going.

In this sentence, who is the relative pronoun and boy is its antecedent.

This is the girl who won the prize.

“which” is used for animals and things.

The dog which barks.

That is used instead of who or which in this case.

This is the best picture that I ever saw.

5.3 – Interrogative pronouns

It is used to introduce or create an asking position in a sentence. Who, whom, which, and whose are interrogative pronouns.

Examples

Who wrote this book? (for persons

only)

What is your name? (for things)

Which boy here is your friend?

5.4 – Demonstrative pronoun

It points out a person, thing, place

or idea. This, that, these and those are called demonstrative pronouns.

That is a circuit-breaker.

These are cups of a team.

5.5 – Reflexive pronoun

The type of pronoun that ends in self or selves is called a reflexive pronoun.

Examples: myself, ourselves, yourself, herself, himself, itself, themselves.

Use in sentence: They worked hard to

get out themselves from the debt.

Indefinite pronoun: An indefinite

pronoun does not refer to a specific person, place thing or idea.

Examples

Nothing lasts forever.

No one can make this design.

Further Reading: Different Types of Pronouns with 60+ Examples

6 – Prepositions

Words placed before a noun or pronoun

to show how the person or thing denoted stands in relation to some other person

or thing.

Examples: A house on a hill. Here, the word “on” is a preposition.

The noun and pronoun that follow the preposition are called its object. We can identify prepositions in the following examples.

In 2006, in March, in the garden,

On 14th August, on Friday, on the table

At 8:30 pm, at 9 o’clock, at the door, at noon, at night, at midnight

However, we use “in” for morning and evening.

Further Reading: Preposition Usage and Examples

7 – Conjunctions (joining words)

They join words or sentences.

Examples: Jimmy and Tom are good players.

In the above sentence, “and” is a conjunction.

Types of conjunctions

These are the types of conjunctions.

- Nor (used in later part of the negative sentence)

- But (when two different ideas are described in a sentence)

- Yet (when two contrast things are being described in a sentence)

- So (To explain the reason)

- For (it connects a reason to a result)

- Or (to adopt two equal choices)

- And (to join two things or work)

Further Reading: Conjunction Rules with Examples

8 – Interjections

Interjection words are not connected with other parts of a sentence. They are through into a sentence to express some feeling of a mind.

Examples: Hurrah! We won the match.

Alas, hurrah, wow, uh, oh-no, gush, shh are some words used to express the feeling.

It is important to note that placing a word in this or that part of speech is not fixed. It depends upon the work the words are doing in a particular sentence. Thus the same word may appear in three or four parts of speech.

Further Reading: More about Interjections

You can read a detailed article about parts of speech here.

Parts of Speech Exercise with Answers

Read also: 71 Idioms with Meaning and Sentences

The words

of language, depending on various formal and semantic features, are

divided into classes. The traditional grammatical classes of words

are called “parts of speech”, since the word is distinguished not

only by grammatical, but also by semantico-lexemic properties, some

scholars also refer to parts of speech as lexico-grammatical

categories (Смирницкий).

It should

be noted that the term “parts of speech” is purely traditional

and conventional. This name was introduced in the grammatical

teaching of Ancient Greece, where no strict differenciation was drawn

between the word as a vocabulary unit and the word as a functional

element of the sentence.

In modern

linguistics, parts of speech are discriminated on the basis of the

three criteria: “semantic, formal and functional” (Щерба).

The

semantic criterion presupposes (предполагать,

заключать

в

себя)

the generalized meaning, which is characteristic of all the words

constituting (составлять)

a given part of speech. This meaning is understood as the categorical

meaning of the part of speech.

The formal

criterion exposes (выставлять

на

показ)

the specific inflexional and derivational (word-building) features of

part a part of speech.

The

functional criterion concerns the syntactic role of words in the

sentence, typical of a part of speech.

These

three factors of categorical characterization of words are referred

to as ‘meaning’, form and function.

The

three-criteria characterization of parts of speech was developed and

applied to practice in Soviet linguistics. Three names are especially

notable for the elaboration of these criteria: V.V. Vinogradov

in connection with the study of Russian Grammar, A.I. Smirnitskyand

B.A. Ilyish in connection with their study of English Grammar.

Alongside

of the three-criteria principle of dividing the words into

grammatical classes modern linguistics has developed another,

narrower principle based on syntactic featuring of words only.

On

the material of Russian, the principle of syntactic approach to the

classification of word-stock were outlined in the works of A.M.

Peshkovsky. The principles of syntactic classification of English

words were worked out by L. Bloomfield and his followers L. Harris

and especially Ch. Fries.

Here

is how Ch. Fries presents his scheme of English word-classes.

For

his materials he chooses tape-recorded spontaneous conversations

which last 50 hours.

The

three typical sentences are:

Frames:

A.

The concert was good (always).

B.

The clerk remembered the tax (suddenly).

C.

The team went there.

As

a result he divides the words into 4 classes: class I, II, III, IV,

which correspond to the traditional nouns, verbs, adjectives and

adverbs.

Thus,

class I includes all words which can be used in the position of the

words ‘concert’ (frame A), clerk and tax (frame B), team (frame C),

i.e. in the position of subject and object.

Class

II includes the words which have the position of the words ‘was’,

‘remembered’, ‘went’ in the given frames, i.e. in the position of the

predicate or part of the predicate.

Class

III includes the words having the position of ‘good’, and ‘new’, i.e.

in the position of the predicative or attribute.

And

the words of class IV are used in the position of ‘there’ in Frame C,

i.e. of an adverbial modifier.

These

classes are subdivided into subtypes.

Ch.

Fries sticks to the positional approach. Thus such words as man, he,

the others, another belong to class I as they can take the position

before the words of class II, i.e. before the finite verb.

Besides

the 4 classes, Fries finds 15 groups of function words. Following the

positional approach, he includes into one and the same group the

words of quite different types.

Thus,

group A includes all words, which can take the position of the

definite article ‘the’, such as: no, your, their, both, few, much,

John’s, our, four, twenty.

But

Fries admits, that some of these words may take the position of class

I in other sentences.

Thus,

this division is very complicated, one and the same word may be found

in different classes due to its position in the sentence. So Fries’

idea, though interesting, doesn’t reach its aim to create a new

classification of classes of words, but his material gives

interesting data concerning the distribution of words and their

syntactic valency.

Today

many scholars believe that it is difficult to classify English parts

of speech using one criterion.

Some

Soviet linguists class the English parts of speech according to a

number of features.

1.

Lexico-grammatical meaning: (noun — substance, adjective — property,

verb — action, numeral — number, etc).

2.

Lexico — grammatical morphemes: (-er, -ist, -hood — noun; -fy, -ize —

verb; -ful, -less — adjective, etc).

3.

Grammatical categories and paradigms.

4.

Syntactic functions

5.

Combinability (power to combine with other words).

In

accord with the described criteria, words are divided into notional

and functional, which reflects their division in the earlier

grammatical tradition into changeable and unchangeable.

To

the notional parts of speech of the English language belong the noun,

the adjective, the numeral, the pronoun, the verb, the adverb.

To

the basic functional series of words in English belong the article,

the preposition, the conjunction, the particle, the modal word, the

interjection.

The

difference between them may be summed up as follows:

1) Notional

parts

of speech express notions and function as sentence parts (subject,

object, attribute, adverbial modifier).

2) Notional

parts

of speech have a naming function and make a sentence by themselves:

Go!

***

1)

Functional

words

(or form-words) cannot be used as parts of the sentence and cannot

make a sentence by themselves.

2)

Functional

words

have no naming function but express relations.

3)

Functional

words

have a negative combinability but a linking or specifying function.

E.g. prepositions and conjunctions are used to connect words, while

particles and articles — to specify them.

Each

part of speech is further subseries in accord with various particular

semantico-functional and formal features of the words.

Thus,

nouns are subdivided into proper and common, animate and unanimate,

countable and uncountable, conctrete and abstract.

E.g.

Mary-girl, man-earth, can-water, stone-honesty.

This

proves that the majority of English parts of speech has a field-like

structure.

The

theory of grammatical fields was worked out by V.G. Admoni on the

material of the German language.

The

essence of this theory is as follows. Every part of speech has words,

which obtain all the features of this part of speech. They are its

nucleus. But there are such words which don’t have all the features

of this part of speech, though they belong to it.

Consequently,

the field includes central and peripheral elements.

Because

of the rigid word-order in the English sentence and scantiness of

inflected forms, English parts of speech have developed a number of

grammatical meanings and an ability to be converted.

E.g.

It’s better to be a has-been than a never-was.

He

grows old. He grows roses.

The

conversation may be written one part of speech.

She

took off her glasses.

Give

me a glass of water.

The

person in the glass was making faces.

Don’t

break the glass when cleaning the window.

They

are called variants of one part of speech. Because of homonymy and

polysemy many notional words may have the same form as functional

words.

E.g.

He grows roses — He grows old.

Professor

Ilyish objects to the division of words into notional and functional

(formal) parts of speech. He says that prepositions and conjunctions

are no less notional than nouns and verbs, as they also express some

relations and connections existing independently.

Соседние файлы в папке Gosy

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Parts of Speech. Principles of Classification of the Parts of Speech.

√ Parts of speech.

√ Semantic.

√ Morphological.

√ Syntactic.

√ Meaning.

√ Form.

√ Function

√ Meaning

Parts of speech

Parts of speech are grammatical classes of words which are distinguished on the basis of four criteria:

— semantic;

— morphological;

— syntactic;

that of valency (combinability)

1) Meaning. Each part of speech is characterized by the general meaning which is an abstraction from the lexical meaning of the constituent word. Thus, the general meaning of nouns is thingness (substance), the general meaning of verbs is action, state, process; the general meaning of adjectives — quality, quantity.

The general meaning is understood as categorial meaning of the class of words.

Semantic properties of every part of speech find their expression in their grammatical properties. If we take «to sleep, a night sleep, sleepy, asleep» they all refer to the same phenomena of the objective reality but belong to different parts of speech as they have different grammatical properties.

Meaning is supportive criterion in the English language which only helps to check purely grammatical criteria — those of form and function.

Глокая куздра штэка будланула бокра и кудрячит бокрёнка. V. V. Vinogradov

Green ideas sleep furiously.

Such examples though being artificial help us to understand that — grammatical meaning is an objective thing by itself though in real speech it never exists without lexical meaning.

2) Form, (morphological properties) The formal criterion concerns the inflectional and derivational features of words belonging to a given class. That is the grammatical categories they possess, the paradigms they form and derivational and functional morphemes they have.

With the English language this criterion is not always reliable as many words in English are invariable, many words have no derivational affixes and besides the same derivational affixes may be used to build different parts of speech.(e.g. «~ly»: quickly , daily , weakly(n.)).

Because of the limitation of meaning and form as criterion we should rely mainly on words’ syntactic functions (e.g. «round» can be adjective, noun, verb, preposition).

3) Function. Syntactic properties of any class of words are: combinability (distributional criterion), typical syntactic functions in a sentence. The three criteria of defining grammatical classes of words in English may be placed in the following order: syntactic, distribution, form, meaning (Russian: form, meaning, syntactic distribution).

Parts of speech are heterogeneous classes and the boundaries between them are not clearly cut especially in the area of meaning. Within a part of speech there are subclasses which have all the properties of a given class and subclasses which have only some of these properties and may even have features of another class.

So a part of speech may be described as a field which includes both central (most typical) members and marginal (less typical) members. Marginal areas of different parts of speech may overlap and there may be intermediary elements with contradicting features (modal words, statives, pronouns and even verbs).

Words belonging to different parts of speech may be united by common feature and they may constitute a class cutting across other classes (e.g. determiners or quantifiers).

Possible Ways of the Grammatical Classification of the Vocabulary.

The parts of speech and their classification usually involves all the four criteria mentioned and scholars single out from 8 to 13 parts of speech in modern English. The founder of English scientific grammar Henry Sweet finds the following classes of words: noun-words ( here he includes some pronouns and numerals), adjective-words, verbs 4 particles (by this term he denotes words of different classes which have no grammatical categories).

The opposite criterion — structural or distributional — was used by an American scholar Charles Freeze. Each class of words is characterized by a set of positions in a sentence which are defined by substitution test. As a result of distributional analysis Freeze singles out 4 main classes of words roughly corresponding to verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs and 15 classes of function-words.

Notional and Functional Parts of Speech.

Both the traditional and distributional classification divide parts of speech into notional and functional. Notional parts of speech are open classes, new items can be added to them, we extend them indefinitely. Functional parts of speech are closed systems including a limited number of members. As a rule they cannot be extended by creating new items.

Main notional parts of speech are nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs. Members of these four classes are often connected derivationally. Functional parts of speech are prepositions, conjunctions, articles, interjections & particles. Their distinctive features are:

— very general & weak lexical meaning;

— obligatory combinability;

The function of linking and specifying words.

Pronouns constitute a class of words which takes an intermediary position between notional and functional words: on the one hand they can substitute nouns and adjectives; on the other hand they can be used as connectives and specifiers. There may be also groups of closed-system items within an open class (notional, functional and auxiliary verbs).

A word in English is very often not marked morphologically. It makes it easy for words to pass from one class to another. Such words are treated as either lexico-semantic phonemes or as words belonging to one class. The problem which is closely connected with the selection of parts of speech is the problem of conversion.

There are usually the cases of absolute, phonetic identity of words belonging to different parts of speech. About 45% of nouns can be converted into verbs and about 50% of verbs — into nouns. There are different viewpoints on conversion: some scholars think that it is a syntactic word-building means. If they say so they do admit that the word may function as parts of speech at the same time.

Russian linguist Galperin defines conversion as a non-affix way of forming words. There is another theory by French linguist Morshaw who states that conversion is a creation of new words with zero-affix. In linguistics this problem is called «stone-wall-construction problem».

Another factor which makes difficult to select parts of speech, in English is abundance of homonyms in English. They are words and forms identical in form, sounding, spelling, but different in meaning. Usually the great number of homonyms in English is explained by monosyllabic structure of words but it’s not all the explanation.

The words are monosyllabic in English because there are few endings in it, because English is predominantly analytical. We differentiate between full and partial homonymity, we usually observe full homonymity within one pan of speech and partial — within different parts of speech. If we have two homonyms within one part of speech their paradigms should fully coincide.

Homonyms can be classified into lexical, lexico-grammatical and purely grammatical. We should differentiate between homonymity and polysemantic words.