The word “THAT” can be used as a Definite Article, a Conjunction, an Adverb, Pronoun, and Adjective. Take a look at the definitions and examples below to learn how “THAT” works as different parts of speech.

- Definite Article

“That” is classified as a definite article when it is used to indicate something/someone specific that the listeners or readers already know. For instance, read the sample sentence below:

“Pick up that book on the floor.”

The person being talked to knows exactly what “book” the speaker is referring to.

Definition:

a. refers to a specific person or thing, assuming that the person being addressed understands or is familiar with it

- Examples:

- Look at that old woman

- She lived in New York at that time.

- Where is that friend of yours?

2. Conjunction

Sometimes, “that” can also serve as a conjunction by combining two clauses. For instance, in the sentence:

“I bought the materials that are required for the project.”

“That“ is used to introduce the clause “…are required for the project.” It combines the dependent clause with the independent clause, “I bought the materials…”

Definition:

a. used to introduce a clause that is the subject or object of a verb

- Examples:

- He said that he was hungry.

b. used to introduce a clause that completes or explains the meaning of a previous noun or adjective or of the pronoun it

- Examples:

- She was so exhausted that she couldn’t think straight.

c. used to introduce a clause that states a reason or purpose

- Examples:

- The boss seems pleased that I wanted to pursue with the training.

3. Adverb

The word can also be used as an adverb, especially in verbal communication. It is normally used to show the intensity of a particular adjective. Take for example the sentence below:

“He is that old.”

In this sample sentence, the word “that” somehow intensifies and shows the degree of the adjective “old.”

Definition:

a. to the degree that is stated or suggested

- Examples:

- It wasn’t that difficult.

b. to the degree or extent indicated by a gesture

- Examples:

- She wouldn’t go that far.

c. to a great degree

- Examples:

- It was that wide, perhaps even wider.

4. Pronoun

In some cases, the word “that” also functions as a freestanding pronoun. Look at the sample sentence below:

“That’s exactly what I thought.”

It can be presumed that the word “that” is representing or replacing a specific thought.

Definition:

a. used to identify a specific person or thing observed by the speaker

- Examples:

- That is my brother with a new car.

b. referring to a specific thing previously mentioned, known, or understood

- Examples:

- It’s not as bad as all that.

- All the people that were left behind became infected with the virus.

5. Adjective

The word “that” functions as an adjective when it is used to modify a noun. It is also useful in clarifying which noun the speaker is referring to in the sentence. Take for example, the sentence below:

“That cat is so adorable.”

The word “that” modifies “cat” by emphasizing that it is the particular noun being referred to.

Definition:

a. used to indicate which person, thing, or idea is being shown, pointed to, or mentioned

- Examples:

- That building is the oldest in the city.

- Do you want this bag or that one?

b. used to indicate the one that is farther away or less familiar

- Examples:

- I don’t know how it got that way.

That can be a pronoun (often a relative pronoun), an adverb, or an adjective, depending on the use. Some dictionaries also list it as a conjunction, but I disagree.

More answers

That can be a pronoun (often a relative pronoun), an adverb, or an adjective, depending on the use. Some dictionaries also list it as a conjunction, but I disagree.

That’s is a contraction of two parts of speech, that (pronoun)

and is (verb).

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What part of speech is the word that’s?

Write your answer…

Still have questions?

Continue Learning about English Language Arts

I know that «that» can function as many different parts of speech, so what part of speech is it in the phrase «the stuff that dreams are made of»?

RegDwigнt

96.4k39 gold badges305 silver badges399 bronze badges

asked Nov 14, 2013 at 4:53

ODO believes it to be a relative pronoun:

that pronoun (plural those)

5 (plural that) [relative pronoun] used to introduce a defining clause, especially one essential to identification:

• instead of ‘which’, ‘who’, or ‘whom’:

the woman that owns the place

• instead of ‘when’ after an expression of time:

the year that Anna was born[ODO]

The example “instead of which, who or whom” exactly matches your sentence.

answered Nov 14, 2013 at 7:21

Andrew Leach♦Andrew Leach

98.4k12 gold badges188 silver badges306 bronze badges

2

«That» introduces a sentence complement to a noun, as in «the fact that we left», where the sentence «we left» is complement to «fact». When the complement is a relative clause, there is a common alternative analysis that makes «that» a relative pronoun, yet this is not right, because relative pronouns need not occur at the beginning of a relative clause. «That» in relative clauses, unlike relative pronouns, always comes at the very beginning of the clause. Compare, «the facts with which we are familiar», *»the facts with that we are familiar», «the facts that we are familiar with».

answered Aug 13, 2015 at 18:38

Greg LeeGreg Lee

17.1k2 gold badges17 silver badges39 bronze badges

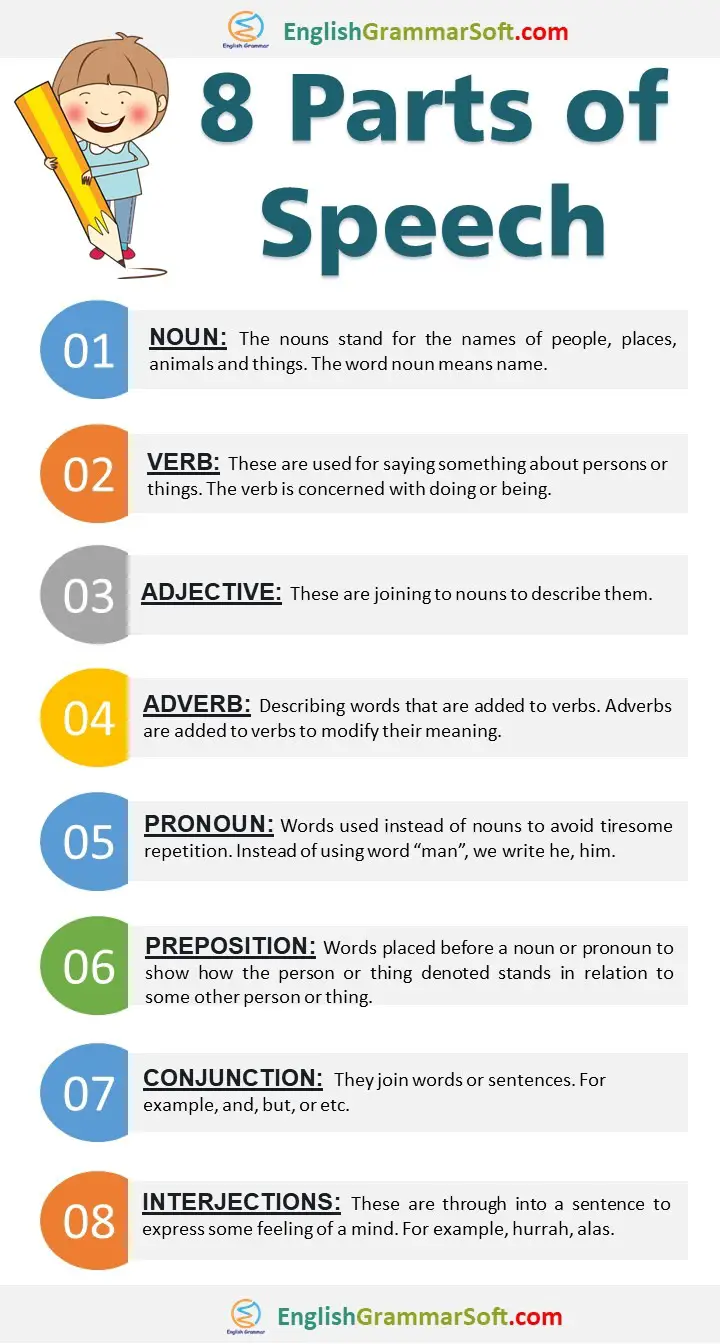

It is a fact that almost every word of English has got the capacity to be employed as a different part of speech. At one place, a particular word may be used as a noun, at another as a verb, and yet at another place as an adjective.

These words enable the learners of the English language to understand the behavior of a particular word in various positions.

Importance of Parts of Speech in Communication

As you know, English sentences are used to communicate a complete thought. The importance of parts of speech lies in their proper utilization, which can help your understanding and confidence grow immensely.

Proper usage of parts of speech means that you can impart clear messages and understand them because you know the rules of the language.

Each word in a sentence belongs to one of the eight parts of speech according to the work it is doing in that sentence. There are 8 parts of speech.

- Noun

- Verb

- Adjective

- Adverb

- Pronoun

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

1 – Noun (Naming words)

The nouns stand for the names of people, places, animals, and things. The word noun means name. Look at these sentences.

“John lives in Chicago. He has two bikes. He is fond of riding bikes.”

In the above example, John is the name. We cannot use the same name again and again in different sentences. Here, we used “he” in the next two sentences instead of “John”. “He” is called the pronoun.

Types of nouns are

1.1 – Common Noun

It describes a person, place, and thing.

Examples: City, country, town, boy.

1.2 – Proper Noun

It includes a particular person, place, thing, or idea and begins with a capital letter.

Examples: Austria, Manchester, United Kingdom, etc.

1.3 – Abstract Noun

An abstract noun describes names, ideas, feelings, emotions or qualities, the subject of any paragraph comes under this category. It does not take “the”.

Examples: grief, loss, happiness, greatness.

1.4 – Concrete Noun

It describes material things, persons or places. The existence of that thing can be physically observed.

Examples: Book, table, car, etc.

1.5 – Countable and Uncountable Noun

Countable nouns can be singular or plural. It can be counted.

Examples: Ships, cars, buses, books, etc.

The uncountable noun is neither singular nor plural. It cannot be counted.

Examples: Water, milk, juice, butter, music, etc.

1.6 – Collective Noun

It includes the group and collection

people, things or ideas. It is in unit form and is considered as singular.

Examples: Staff of office, group of visitors.

However, people and police can be

considered both singular and plural.

1.7 – Possessive Noun

It shows ownership or relationship.

Examples: Jimmy’s pen.

Further Reading: 11 Types of Nouns with Examples

2 – Verb (Saying words)

These are used for saying something

about persons or things. The verb is concerned with doing or being.

Examples

- A hare runs (action) very fast.

- Aslam is a good student.

Types of verbs

2.1 – Actions verbs

(run, move, write etc)

2.2 – Linking verbs

(to be (is, am, are, was, were), seem, feel, look, understand)

2.3 – Auxiliary (helping) verbs

(have, do, be)

2.4 – Modal Verbs

(can, could, may, might, will/shall)

2.5 – Transitive verbs

It takes an object.

Example – He is reading a newspaper.

2.6 – Intransitive verbs

It does not take the object.

Example – He awakes.

Further Reading: What are the verbs in English?

3 – Adjectives (describing words)

These are joining to nouns to describe

them.

Examples

- A hungry wolf.

- A brown wolf.

- A lazy boy.

- A tall man.

It is used before a noun and after a linking verb.

Before noun example

A new brand has been launched.

After linking verb example

Imran is rich.

It is used to clarify nouns.

Example: smart boy, blind man

Types of adjectives

3.1 – Simple degree

He is intelligent.

3.2 – Comparative

Ali is intelligent than Imran.

3.3 – Superlative

Comparison of one person with class,

country or world. In this type “the” is used.

Example: Ali is the wisest boy.

3.4 – Demonstrative adjective

It points out a noun. These are four

in number.

This That These Those

3.5 – Indefinite adjectives

It points out nouns. They often tell

“how many” or “how much” of something.

Interrogative adjectives: it is used to ask questions

Examples

- Which book?

- What time?

- Whose car?

Further Reading: More About Adjectives

4 – Adverbs

Describing words that are added to verbs. Just as adjectives are added to describe them, adverbs are added to verbs to modify their meaning. The word “modify” means to enlarge the meaning of the adverbs.

Examples

- Emma sings beautifully. (used with verb)

- Cameron is extremely clever. (used with adjective)

- This motor car goes incredibly fast. (used with another adverb)

Types of adverb

4.1 – Adverb of manner

This type of adverb deals with the

action something

Example

- I walk quickly.

- He wrote slowly.

4.2 – Adverb of place

Happening of something or the place where it happens.

Examples:

There was somebody sitting nearby.

Here, these, upstairs, nowhere everywhere, outside, in, out, are called adverb of place.

4.3 – Adverb of time

It determines the time of the happening of something.

Examples

- She went there last night.

- Have you seen him before?

- He wrote a letter yesterday.

Tomorrow, today, now, then,

yesterday, already, ago.

4.4 – Linking adverbs (then, however)

It creates a connection between two clauses or sentences.

Example

There will be clouds in Lahore. However, the sun is expected in Multan.

Note: Besides modifying the meaning of a verb, adverbs also modify adjectives and other adverbs.

Examples

- It is a very large house.

- He is too weak to walk.

- He ran too fast.

Further Reading: 11 Types of Adverbs with Examples

5 – Pronouns

Words that are used instead of nouns to avoid tiresome repetition. Instead of using the word man in a composition, we often write he, him, himself. In place of the word “woman”, we write she, her, or herself. For both the nouns ‘men’ and ‘women’ we use, they, them, themselves.

Some of the most common pronouns are

Singular: I, he, she, it, me, him,

her

Plural: We, they, out, us, them.

Examples

Imran was hurt. He didn’t panic.

He checked the mobile. It still

worked.

Types of Pronouns

It stands instead of persons. They have different forms according to the person who is supposed to be speaking.

First person: I, we, me, us, mine, our, ourselves.

Second person: thou, you, there.

Third person: He, she, it, his, him

5.1 – Possessive pronouns

Such as mine, ours, yours, hers and theirs.

- This book is mine.

- My horse and yours are tired.

5.2 – Relative pronoun

Who, whom, which and they are called relative pronouns. They are called relative because they relate to some word in the main clause. The word to which pronoun relates is called the antecedent.

Example

I saw a boy who was going.

In this sentence, who is the relative pronoun and boy is its antecedent.

This is the girl who won the prize.

“which” is used for animals and things.

The dog which barks.

That is used instead of who or which in this case.

This is the best picture that I ever saw.

5.3 – Interrogative pronouns

It is used to introduce or create an asking position in a sentence. Who, whom, which, and whose are interrogative pronouns.

Examples

Who wrote this book? (for persons

only)

What is your name? (for things)

Which boy here is your friend?

5.4 – Demonstrative pronoun

It points out a person, thing, place

or idea. This, that, these and those are called demonstrative pronouns.

That is a circuit-breaker.

These are cups of a team.

5.5 – Reflexive pronoun

The type of pronoun that ends in self or selves is called a reflexive pronoun.

Examples: myself, ourselves, yourself, herself, himself, itself, themselves.

Use in sentence: They worked hard to

get out themselves from the debt.

Indefinite pronoun: An indefinite

pronoun does not refer to a specific person, place thing or idea.

Examples

Nothing lasts forever.

No one can make this design.

Further Reading: Different Types of Pronouns with 60+ Examples

6 – Prepositions

Words placed before a noun or pronoun

to show how the person or thing denoted stands in relation to some other person

or thing.

Examples: A house on a hill. Here, the word “on” is a preposition.

The noun and pronoun that follow the preposition are called its object. We can identify prepositions in the following examples.

In 2006, in March, in the garden,

On 14th August, on Friday, on the table

At 8:30 pm, at 9 o’clock, at the door, at noon, at night, at midnight

However, we use “in” for morning and evening.

Further Reading: Preposition Usage and Examples

7 – Conjunctions (joining words)

They join words or sentences.

Examples: Jimmy and Tom are good players.

In the above sentence, “and” is a conjunction.

Types of conjunctions

These are the types of conjunctions.

- Nor (used in later part of the negative sentence)

- But (when two different ideas are described in a sentence)

- Yet (when two contrast things are being described in a sentence)

- So (To explain the reason)

- For (it connects a reason to a result)

- Or (to adopt two equal choices)

- And (to join two things or work)

Further Reading: Conjunction Rules with Examples

8 – Interjections

Interjection words are not connected with other parts of a sentence. They are through into a sentence to express some feeling of a mind.

Examples: Hurrah! We won the match.

Alas, hurrah, wow, uh, oh-no, gush, shh are some words used to express the feeling.

It is important to note that placing a word in this or that part of speech is not fixed. It depends upon the work the words are doing in a particular sentence. Thus the same word may appear in three or four parts of speech.

Further Reading: More about Interjections

You can read a detailed article about parts of speech here.

Parts of Speech Exercise with Answers

Read also: 71 Idioms with Meaning and Sentences

When you start breaking it down, the English language is pretty complicated—especially if you’re trying to learn it from scratch! One of the most important English words to understand is the.

But what part of speech is the word the, and when should it be used in a sentence? Is the word the a preposition? Is the a pronoun? Or is the word the considered a different part of speech?

To help you learn exactly how the word the works in the English language, we’re going to do the following in this article:

- Answer the question, «What part of speech is the?»

- Explain how to use the correctly in sentences, with examples

- Provide a full list of other words that are classified as the same part of speech as the in the English language

Okay, let’s get started learning about the word the!

In the English language the word the is classified as an article, which is a word used to define a noun. (More on that a little later.)

But an article isn’t one of the eight parts of speech. Articles are considered a type of adjective, so «the» is technically an adjective as well. However, «the» can also sometimes function as an adverb in certain instances, too.

In short, the word «the» is an article that functions as both an adjective and an adverb, depending on how it’s being used. Having said that, the is most commonly used as an article in the English language. So, if you were wondering, «Is the a pronoun, preposition, or conjunction,» the answer is no: it’s an article, adjective, and an adverb!

While we might think of an article as a story that appears in a newspaper or website, in English grammar, articles are words that help specify nouns.

The as an Article

So what are «articles» in the English language? Articles are words that identify nouns in order to demonstrate whether the noun is specific or nonspecific. Nouns (a person, place, thing, or idea) can be identified by two different types of articles in the English language: definite articles identify specific nouns, and indefinite articles identify nonspecific nouns.

The word the is considered a definite article because it defines the meaning of a noun as one particular thing. It’s an article that gives a noun a definite meaning: a definite article. Generally, definite articles are used to identify nouns that the audience already knows about. Here’s a few examples of how «the» works as a definite article:

We went to the rodeo on Saturday. Did you see the cowboy get trampled by the bull?

This (grisly!) sentence has three instances of «the» functioning as a definite article: the rodeo, the cowboy, and the bull. Notice that in each instance, the comes directly before the noun. That’s because it’s an article’s job to identify nouns.

In each of these three instances, the refers to a specific (or definite) person, place, or thing. When the speaker says the rodeo, they’re talking about one specific rodeo that happened at a certain place and time. The same goes for the cowboy and the bull: these are two specific people/animals that had one kinda terrible thing happen to them!

It can be a bit easier to see how definite articles work if you see them in the same sentence as an indefinite article (a or an). This sentence makes the difference a lot more clear:

A bat flew into the restaurant and made people panic.

Okay. This sentence has two articles in it: a and the. So what’s the difference? Well, you use a when you’re referring to a general, non-specific person, place, or thing because its an indefinite article. So in this case, using a tells us this isn’t a specific bat. It’s just a random bat from the wild that decided to go on an adventure.

Notice that in the example, the writer uses the to refer to the restaurant. That’s because the event happened at a specific time and at a specific place. A bat flew into one particular restaurant to cause havoc, which is why it’s referred to as the restaurant in the sentence.

The last thing to keep in mind is that the is the only definite article in the English language, and it can be used with both singular and plural nouns. This is probably one reason why people make the mistake of asking, «Is the a pronoun?» Since articles, including the, define the meaning of nouns, it seems like they could also be combined with pronouns. But that’s not the case. Just remember: articles only modify nouns.

Adjectives are words that help describe nouns. Because «the» can describe whether a noun is a specific object or not, «the» is also considered an adjective.

The as an Adjective

You know now that the is classified as a definite article and that the is used to refer to a specific person, place, or thing. But defining what part of speech articles are is a little bit tricky.

There are eight parts of speech in the English language: nouns, pronouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, prepositions, conjunctions, and interjections. The thing about these eight parts of speech in English is that they contain smaller categories of types of words and phrases in the English language. Articles are considered a type of determiner, which is a type of adjective.

Let’s break down how articles fall under the umbrella of «determiners,» which fall under the umbrella of adjectives. In English, the category of «determiners» includes all words and phrases in the English language that are combined with a noun to express an aspect of what the noun is referring to. Some examples of determiners are the, a, an, this, that, my, their, many, few, several, each, and any. The is used in front of a noun to express that the noun refers to a specific thing, right? So that’s why «the» can be considered a determiner.

And here’s how determiners—including the article the—can be considered adjectives. Articles and other determiners are sometimes classified as adjectives because they describe the nouns that they precede. Technically, the describes the noun it precedes by communicating specificity and directness. When you say, «the duck,» you’re describing the noun «duck» as referring to a specific duck. This is different than saying a duck, which could mean any one duck anywhere in the world!

When «the» comes directly before a word that’s not a noun, then it’s operating as an adverb instead of an adjective.

The as an Adverb

Finally, we mentioned that the can also be used as an adverb, which is one of the eight main parts of speech we outlined above. Adverbs modify or describe verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs, but never modify nouns.

Sometimes, the can be used to modify adverbs or adjectives that occur in the comparative degree. Adverbs or adjectives that compare the amounts or intensity of a feeling, state of being, or action characterizing two or more things are in the comparative degree. Sometimes the appears before these adverbs or adjectives to help convey the comparison!

Here’s an example where the functions as an adverb instead of an article/adjective:

Lainey believes the most outrageous things.

Okay. We know that when the is functioning as an adjective, it comes before a noun in order to clarify whether it’s specific or non-specific. In this case, however, the precedes the word most, which isn’t a noun—it’s an adjective. And since an adverb modifies an adjective, adverb, or verb, that means the functions as an adverb in this sentence.

We know that can be a little complicated, so let’s dig into another example together:

Giovanni’s is the best pizza place in Montana.

The trick to figuring out whether the article the is functioning as an adjective or an adverb is pretty simple: just look at the word directly after the and figure out its part of speech. If that word is a noun, then the is functioning as an adjective. If that word isn’t a noun, then the is functioning like an adverb.

Now, reread the second example. The word the comes before the word best. Is best a noun? No, it isn’t. Best is an adjective, so we know that the is working like an adverb in this sentence.

How to Use The Correctly in Sentences

An important part of answering the question, «What part of speech is the word the?» includes explaining how to use the correctly in a sentence. Articles like the are some of the most common words used in the English language. So you need to know how and when to use it! And since using the as an adverb is less common, we’ll provide examples of how the can be used as an adverb as well.

Using The as an Article

In general, it is correct and appropriate to use the in front of a noun of any kind when you want to convey specificity. It’s often assumed that you use the to refer to a specific person, place, or thing that the person you’re speaking to will already be aware of. Oftentimes, this shared awareness of who, what, or where «the» is referring to is created by things already said in the conversation, or by context clues in a given social situation.

Let’s look at an example here:

Say you’re visiting a friend who just had a baby. You’re sitting in the kitchen at your friend’s house while your friend makes coffee. The baby, who has been peacefully dozing in a bassinet in the living room, begins crying. Your friend turns to you and asks, «Can you hold the baby while I finish doing this?»

Now, because of all of the context surrounding the social situation, you know which baby your friend is referring to when they say, the baby. There’s no need for further clarification, because in this case, the gives enough direct and specific meaning to the noun baby for you to know what to do!

In many cases, using the to define a noun requires less or no awareness of an immediate social situation because people have a shared common knowledge of the noun that the is referring to. Here are two examples:

Are you going to watch the eclipse tomorrow?

Did you hear what the President said this morning?

In the first example, the speaker is referring to a natural phenomenon that most people are aware of—eclipses are cool and rare! When there’s going to be an eclipse, everyone knows about it. If you started a conversation with someone by saying, «Are you going to watch the eclipse tomorrow?» it’s pretty likely they’d know which eclipse the is referring to.

In the second example, if an American speaking to another American mentions what the President said, the other American is likely going to assume that the refers to the President of the United States. Conversely, if two Canadians said this to one another, they would likely assume they’re talking about the Canadian prime minister!

So in many situations, using the before a noun gives that noun specific meaning in the context of a particular social situation.

Using The as an Adverb

Now let’s look at an example of how «the» can be used as an adverb. Take a look at this sample sentence:

The tornado warning made it all the more likely that the game would be canceled.

Remember how we explained that the can be combined with adverbs that are making a comparison of levels or amounts of something between two entities? The example above shows how the can be combined with an adverb in such a situation. The is combined with more and likely to form an adverbial phrase.

So how do you figure this out? Well, if the words immediately after the are adverbs, then the is functioning as an adverb, too!

Here’s another example of how the can be used as an adverb:

I had the worst day ever.

In this case, the is being combined with the adverb worst to compare the speaker’s day to the other days. Compared to all the other days ever, this person’s was the worst…period. Some other examples of adverbs that you might see the combined with include all the better, the best, the bigger, the shorter, and all the sooner.

One thing that can help clarify which adverbs the can be combined with is to check out a list of comparative and superlative adverbs and think about which ones the makes sense with!

3 Articles in the English Language

Now that we’ve answered the question, «What part of speech is the?», you know that the is classified as an article. To help you gain a better understanding of what articles are and how they function in the English language, here’s a handy list of 3 words in the English language that are also categorized as articles.

|

Article |

Type of Article |

What It Does |

Example Sentence |

|

The |

Definite Article |

Modifies nouns by giving them a specific meaning |

Please fold the laundry. Do you want to go to the concert? |

|

A |

Indefinite Article |

Modifies a noun that refers to a general idea; appears before nouns that begin with a consonant. |

Do you want to go to a concert? |

|

An |

Indefinite Article |

Modifies a noun that refers to a general idea; appears before nouns that begin with a vowel. |

Do you want to go to an arcade? Let’s get an iguana. |

What’s Next?

If you’re looking for more grammar resources, be sure to check out our guides on every grammar rule you need to know to ace the SAT (or the ACT)!

Learning more about English grammar can be really helpful when you’re studying a foreign language, too. We highly recommend that you study a foreign language in high school—not only is it great for you, it looks great on college applications, too. If you’re not sure which language to study, check out this helpful article that will make your decision a lot easier.

Speaking of applying for college…one of the most important parts of your application packet is your essay. Check out this expert guide to writing college essays that will help you get into your dream school.

Need more help with this topic? Check out Tutorbase!

Our vetted tutor database includes a range of experienced educators who can help you polish an essay for English or explain how derivatives work for Calculus. You can use dozens of filters and search criteria to find the perfect person for your needs.

Have friends who also need help with test prep? Share this article!

About the Author

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

The basic building blocks of any language are the words and sounds of that language. English is no exception. We will start with the categories into which we classify the words of English. It is quite likely that you will already know the names of some or all of the parts of speech. Nevertheless, this is where we must begin.

The parts of speech are as follows:

- Nouns

- Pronouns

- Adjectives

- Verbs

- Adverbs

- Articles

- Determiners

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Prepositions

These are also known as word classes. The terms are familiar to most people, and are in everyday use. However, many people would probably admit that their understanding of some of them is a little sketchy. We will now take each in turn and have a closer look.

Nouns

What are nouns? Very few people with a good knowledge of English would expect to experience any difficulty in picking the nouns out of the following list:

briefcase, open, disc, plate, London, knife, write, usually, and, however, football, sing

My guess is that you probably decided that the following were nouns:

- briefcase

- disc

- plate

- London

- knife

- football

Who knows? Perhaps you are right. Briefcase is certainly a noun and London as a place name must be, but what about knife? This is a more difficult decision. We have no context. What if we found this word in a sentence such as ‘He knifed me!’ — surely here it is a verb? And what about ‘plate’ — is this a noun? Suppose the context were ‘The window was plate glass.’ Or perhaps, ‘The frame had been plated with silver.’ So is ‘disc’ a noun? Not always, it depends on how it is used in a particular sentence. The lesson here is ‘Be careful!’ When a student asks you the meaning of a word, always check the context in which it appears before answering. Remember in the world of TEFL, as in the world in general, it is not what you don’t know that gives you the biggest problems, but what you think you know!

So how can we define the word class ‘noun’ then? One apparently acceptable definition might be that a noun is a word that represents one of the following:

|

a person |

David |

|

a place |

Paris |

|

a thing |

stapler |

|

an activity |

hockey |

|

a quality |

responsibility |

|

a state |

poverty |

|

an idea |

communism |

Does a noun have to be a single word? What about ‘disc jockey,’ or ‘post office’? Are these nouns? The answer is ‘Yes they are’. These are called compound nouns and are quite common in English. So the word class ‘noun’ is not restricted to single words. Can a noun consist of more than two words then? Once again the answer is ‘yes’. An example might be ‘football team coach’. These are often found in newspaper headlines, where space is at a premium, since they usually express quite complex ideas in very few words.

In a sentence nouns can be used as either the subject or the object of the main verb.

John (subject) kissed (verb) Maria (object).

Types of Nouns

The word class ‘Nouns’ can be sub-divided into the following four types:

|

Abstract |

The name of an action, an idea, a physical condition, quality or state of mind |

an attack, Communism, liveliness, modesty, insanity |

|

Collective |

A name for a collection or group of animals, people or things that are thought of as being one thing |

flock, gang, fleet |

|

Common |

A name that can be applied to all members of a large class of animals, people or things |

puppy, woman, banana |

|

Proper |

The name by which a particular animal, organisation, person, place or thing is known |

Fido, Microsoft, Julia, Liverpool, the Tower of London. Capital letters are used in order to distinguish between common nouns and proper nouns e.g., broom and Broom, where the former is an implement used for sweeping floors while the latter is a surname. |

There are some nouns that can be placed in more than one of these groups depending on how we are thinking at the time of usage. An example would be the noun ‘family’, which could be a collective if we are thinking of the family as a unit e.g. ‘My family is quite large.’ Or a common noun if we are thinking in terms of a collection of individuals e.g. Helen’s family are coming up next week.’ Many Americans may find this particular example unacceptable since in most parts of the US ‘family’ can never agree with the plural verb form ‘is’. In British English, however, this usage is perfectly correct.

Nouns can also be divided into two other groups: countable and uncountable. Water, flour and sand are examples of uncountable nouns. It would be very strange to use them with a number as in six flours or three sands. Countable nouns, on the other hand, can be used with numbers: seven men, two houses, etc. Countable nouns have a plural form. This is usually made by the addition of an ‘s’ or ‘es’ to the end of the singular form: guitars, books, ships, glasses etc. Some countable nouns, however, have an irregular plural form: men, children, wives, geese, etc. Plural countable nouns are always used with plural verb forms. So ‘Coconuts are nice.’ and not *’Coconuts is nice.’* Uncountable nouns have only one form and therefore can only be used with singular verbs. So ‘Water is used as a coolant.’ but never *’Water are used as a coolant.’*

Back to Top

Pronouns

In English, sentences such as ‘John ran up to the house, checked to see John wasn’t being watched and then John knocked on the door twice.’ would cause confusion. How many Johns are involved? Which of them knocked on the door? Probably the solution least likely to occur to a native speaker of English would be that there was only one John and that he carried out all three actions. Why is that? Well, it’s because English just doesn’t work like that! The sentence should be rendered thus ‘John ran up to the house, checked to see he wasn’t being watched and then knocked on the door twice.’ So what makes the difference? Obviously it must be the use of the word ‘he’ in place of John in the second instance. What is ‘he’ then? ‘He’ is a member of the word class Pronouns. These are words that stand in the place of nouns in order to avoid unnecessary repetition.

Kinds of pronoun:

|

Demonstrative |

this, that, these, those, the former, the latter ( ‘Have you seen this?’) |

|

Distributive |

each, either, neither ( ‘Give me either.’) |

|

Emphatic |

myself, yourself, his/herself, ourselves, etc. ( ‘Do it yourself.’) |

|

Indefinite |

one, some, any, some-body/one, any-body/one, every-body/one |

|

Interrogative |

what, which, who ( ‘Who was that?’) |

|

Personal |

I, you, he, she, it, we, you, they |

|

Possessive |

mine, yours hers, his, ours, theirs |

|

Reflexive |

myself, yourself, her/himself, ourselves, etc. ( ‘She cut herself, while slicing bread.’) |

|

Relative |

that, what, which, who (as in, ‘The car that hit him went that way.’) |

It should be noted that some of these words may also at times be deemed adjectives. It is a feature of the English language that many words have multiple uses and hence can be different parts of speech according to the context in which they are found.

Back to Top

Adjectives

Adjectives are words that describe/qualify nouns or pronouns:

- ‘She was a quiet woman.’

- ‘That’s an unusual one.’

Types of adjective

|

Demonstrative |

this, that, these, those (‘I like this picture.‘) |

|

Distributive |

either, neither, each, every (‘Either wine is fine by me.‘) |

|

Interrogative |

what? which? (‘Which wine would you like?‘) |

|

Numeral |

one, two, three, etc. |

|

Indefinite |

all, many, several |

|

Possessive |

my, your, his, her, our, their |

|

Qualitative |

French, wooden, nice |

Not surprisingly, most adjectives fit into the ‘Qualitative‘ category, as their basic function is to describe.

Some adjectives are made from nouns or verbs by the addition of a suffix:

- comfort — comfortable

- health — healthy

- success — successful

- consume — consumable

- consider — considerate

Many positive adjectives can be made negative by the addition of a prefix:

- comfortable — uncomfortable

- responsible — irresponsible

- respectful — disrespectful

- patient — impatient

- considerate — inconsiderate

Comparative and Superlative Adjectives

Some adjectives are used to compare and contrast things:

- big — bigger — biggest

- happy — happier — happiest

There is more information about this important use later.

Verbs

Verbs are words that indicate actions or physical and/or mental states.

|

Action |

Susan slapped Michael. |

|

Mental state |

Paul was exhausted. |

|

Physical state |

Stephen felt sad. |

It is a popular misconception that verbs are ‘doing-words‘. Unfortunately, this is too simple an explanation as only some verbs fit this description. An example of one that doesn’t might be ‘seem‘ as in, ‘ Sarah seemed puzzled‘. What is ‘done‘ in this case? Absolutely nothing! In fact, only verbs indicating actions can be called ‘doing-words‘.

Most verbs have three forms. The first form (present) also uses an inflection to indicate third person singular:

|

First form (present) |

Second form (past) |

Third form (past participle) |

|

do(es) |

did |

done |

|

give(s) |

gave |

given |

|

like(s) |

liked |

liked |

|

hit(s) |

hit |

hit |

As you can see sometimes the second and third forms coincide, and occasionally all three forms coincide as in ‘hit’. This is because verbs such as hit, give, take, do, have, etc. are irregular. That is to say that, unlike the vast majority of English verbs, they don’t use ‘-ed’ to make their second and third forms. There are only about two hundred irregular verbs in total, but since they tend to be the most common verbs it seems more. These can be quite a problem for EFL students as they simply have to be learnt and remembered.

Auxiliary and Modal Auxiliary Verbs

There is a category of verb known as ‘auxiliary verbs‘ or sometimes ‘helping verbs‘. This category includes to be, to do and to have. These three verbs are very important. ‘Be‘ is used in forming the ‘continuous aspect‘ — I am flying to France tomorrow.’ It is also used to form the ‘passive‘ — ‘I was arrested.’ ‘Do‘ is used in forming questions and for emphasis. ‘Have‘ is used to form the ‘perfect aspect‘ — ‘I have been here before.’ More about these later, when we look at the English tense system.

Also included in the category auxiliary verbs are nine very special verbs, which form a sub-category of their own called ‘modal auxiliary verbs‘ or ‘modal verbs‘ for short. This sub-category comprises the verbs can, could, may, might, shall, should, will, would and must. These nine verbs share some important characteristics:

- They can never be followed by ‘to‘: ‘I must to go.’ is a badly formed sentence in English.

- They cannot co-occur in the same verb phrase: ‘You must can go’ is also unacceptable.

- They have no ‘third person‘ inflection: ‘She likes reading.’ is fine, but ‘ She cans swim.’ is not.

In a verb phrase they always occupy the first position — ‘It must have been my aunt.’ Likewise, they do not have three forms.

So what exactly do these ‘modal verbs‘ do? An interesting question! The following table should give you some idea.

Modal verbs are used to express:

|

Degrees of certainty |

Certainty (positive/negative) |

We shall/shan’t come. |

|

Probability/Possibility |

She should arrive at about midday. |

|

|

Weak probability |

She might call — you never know! |

|

|

Theoretical/habitual possibility |

You may have a problem |

|

|

Conditional certainty/possibility |

If you had asked me, I would |

|

|

Obligation |

Strong obligation |

All employees must clock in and out. |

|

Prohibition |

Staff must not make personal calls. |

|

|

Weak obligation/recommendation |

When shall we leave? |

|

|

Willingness/Offering |

Can I help you? |

|

|

Permission |

Might I ask a favour? |

|

|

Ability |

Can you swim? |

|

|

Other uses |

Habitual behaviour |

When I was a boy, I would often go skiing. |

|

Irritation |

Must you do that? |

|

|

Requests |

Would you open the window please? |

Some linguists include verbs such as dare, need and ought in the modal verb sub-category. There is some justification for this, as they display the relevant characteristics some of the time. However, since they do not do so all the time it is better to leave them out of this group.

Back to Top

Adverbs

Adverbs describe or add to the meaning of verbs, prepositions, adjectives, other adverbs and even sentences. They answer questions such as ‘How’, ‘Where’ or ‘When’. Many, but by no means all, adverbs are made from adjectives by simply adding the suffix ‘ly’.

Types of adverb:

|

Adverbs of manner |

carefully, gently, quickly, willingly (She kissed him gently on the forehead.) |

|

Adverbs of place |

here, there, between, externally (He lived between a pub and a noisy factory.) |

|

Adverbs of time |

now, annually, tomorrow, recently (I only returned recently.) |

|

Adverbs of degree |

very, almost, nearly, too (She is very rich.) |

|

Adverbs of number |

|

|

Adverbs of certainty |

not, surely, maybe, certainly (Surely he’s not drunk again!) |

|

Interrogative |

How? What? When? Why? (What does it matter?) |

Adverbials

An adverbial is a general term for any word, phrase or clause that functions as an adverb. The definition is necessary because sometimes whole phrases and clauses act as adverbs:

- When I arrived she was watching TV. (adverbial time clause)

- We went to France to visit my brother. (adverbial clause of purpose)

- After breakfast, I went to work. (adverbial phrase)

An ordinary adverb is a single word adverbial.

The adverb/adverbial is quite a difficult area of the English language to get to grips with. It has been said that, when all the other words of English had been classified as nouns, verbs, prepositions, etc., those remaining were dumped into the adverb class because nobody knew what else to do with them. Even if this is not entirely historically accurate, it certainly describes the confused state of this word class.

Back to Top

Articles

The articles in English are the words ‘a‘, ‘an‘ and ‘the‘. They are used with nouns to distinguish between the definite and the indefinite. They are not really a word class in themselves but are actually a sub-group of the word class Determiners. However, EFL usually treats them as a class and so they are dealt with separately here.

The definite article is ‘the‘. Its most common uses are to show that the nouns it is used with refer to:

|

something known to both speaker and listener |

He is in the garage. |

|

something that has already been mentioned |

That woman keeps looking at you. |

|

something that is defined afterwards |

The house where my mother was born is somewhere near here. |

|

something as a specific group or class |

Can you play the piano? (But not ‘Can you play the instrument?’ — Unless which instrument is being referred to is understood by both speaker and listener.) |

The indefinite article is ‘a(n)». I write ‘is’ because ‘a’ and ‘an’ are really the same word: the ‘n’ is added to the article ‘a’ for ease of pronunciation when the following word begins with a vowel sound — an egg, an ostrich, an upwards motion but a unicorn, a united front (because unicorn and united begin with consonant sounds).

The most common uses of the indefinite article are to show that the nouns it is used with refer to:

|

one example of a group or class |

I’ll buy her an ornament for her birthday. |

|

a typical example of a group or class |

A reliable worker deserves a good boss. |

It should be noted that the indefinite implies ‘oneness’ and so cannot be used with plural or uncountable nouns.

Finally, there are some nouns (apart from plural and uncountable) with which articles are not usually used. Examples of these are the names of countries, towns and cities and of people, months, mealtimes (breakfast, lunch, etc.). Where no article is used this is often referred to as the ‘Zero article‘.

For the EFL student articles either present no difficulty at all, or are a major obstacle in their acquisition of English. The determining factor seems to be whether or not there are articles in the student’s first (native) language (L1). If it doesn’t have them, then the student will have additional problems to face when studying a second language (L2) that does. Even quite advanced students make frequent slips with articles. Compounding the problem is the fact that there are no good rules as far as articles are concerned. Many course books offer ‘rules’ but there are so many exceptions that they are difficult to apply and students have to fall back on learning them by heart. Fortunately,

In order to gain some understanding of the difficulty from a teaching perspective, how would you set about explaining to a student with absolutely no understanding of articles why the fourth of the following sentences is unacceptable in English? Then, having done that, how would you explain why the second is fine?

- ‘I stopped the car and got in.’

- ‘I stopped a car and got in.’

- ‘I stopped the car and got out.’

- *’I stopped a car and got out.’*

Or perhaps it is easier to explain why ‘the Moscow’ might be the river Moscow, the hotel Moscow or the restaurant Moscow but couldn’t possibly be the city of that name. Or why, in British English at least, if you are ‘going to the prison’, you are probably visiting someone or maybe you work there, whereas if you are just ‘going to prison’, you are going because you have been convicted of a crime.

By far the biggest problem with articles is not so much when to use ‘a’, ‘an’ or ‘the’ but when not to use an article at all!

Back to Top

Determiners

As has already been mentioned, the determiners are a word class that would normally include the articles, however, as is usual in TEFL, they have been listed above separately. Even so, it is important for the new teacher to understand that this distinction is false.

Determiners are words that restrict the meaning of the nouns they are used with. For example, ‘But I’m certain I put it in this cupboard. Where can it have got to?’ Even if we cannot see what is happening, we understand, from the speaker’s use of ‘this‘, that there must be more than one cupboard. Despite the obvious similarities, it should be clearly understood that determiners are not adjectives.

Types of determiner:

|

Articles |

a pen, the house |

|

Demonstratives |

this hat, these hats, that book, those books |

|

Possessives |

my dog, your sunglasses, her car, etc. |

|

Quantifiers |

many choices, some people, several hooligans, etc. |

|

Numerals |

the second option, seven possibilities, etc. |

Determiners can be grouped according to how they are used:

Group A includes the articles, demonstratives and possessives. The use of a Group A determiner allows us to understand whether or not the speaker believes the listener knows which one(s) is being referred to (e.g. a car, the car), or whether the speaker is talking about a specific example(s) or in general. It is not possible to put two group A determiners together in a phrase: so ‘the car‘ is fine but *’the her car‘* is not. If for some reason we want to do so, we have to use a structure using ‘of‘ (e.g. ‘this husband of yours‘).

Group B is composed mainly of quantifiers. It is possible to put two Group B determiners together where their individual meanings allow it. For example, ‘As a punishment for the city’s stubborn resistance, the invaders executed every third person.’

Most Group B determiners do not use ‘of‘ when placed before nouns (‘Do you have any cream?’ not *’Do you have any of cream?’*). However, when used in combination with a Group A determiner, ‘of‘ must be used (‘Several books were badly damaged in the fire.’, but ‘Several of the books were badly damaged in the fire.’). There are a few cases where a Group B determiner is used in combination with ‘of‘ when placed directly before a noun. These are mostly either place names (‘Most of London was destroyed in the great fire.’) or uncountable nouns that refer to entire subjects or activities (‘It is difficult to determine, with any great certainty, exactly what really happened in the past because much of recorded history was set down by interested parties.’).

Another important thing to be aware of, since many EFL students make this mistake, is that the ‘of‘ structure is not used after the Group B determiners ‘no‘ and ‘every‘. Instead ‘none‘ and ‘every one‘ are used (‘Every student was happy.’, but ‘Every one of her students were happy.’).

The correct use of ‘of‘ with determiners is a complex area and warrants more space than is available here. Those wishing to delve into this more deeply are again advised to refer to Michael Swan’s Practical English Usage.

Back to Top

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that join words, phrases or clauses together and show the relationships that exist between them. Examples of these are: but, and, or (these are known as co-ordinating conjunctions).

- ‘but» is most often used to join and emphasise contrasting ideas: ‘They were exhausted, but very happy.’

- ‘and‘ is simply used to join things without unduly emphasising any differences that may exist (which is not to say that ‘and» cannot be emphatic — with the right intonation obviously it can be.): ‘He put on his hat, coat and an air of indifference.’

Other conjunctions like ‘when‘, ‘because‘, ‘that‘ are known as subordinating conjunctions and unlike the co-ordinating conjunctions are a part of the clause they join.

- ‘when‘ is used to join a time clause to the rest of a sentence: ‘I was shocked when they announced they were giving the prize to me’.

- ‘because‘ joins a fact with its cause: ‘He lied because he thought the truth would hurt her.’

- ‘that‘ is used to join clauses that are acting as the object of a verb: He promised her that he would come if he could. (Compare the above with He(subject) promised(verb) her(indirect object) a new dress(object))

Conjunctions can consist of more than one word. Examples of these are: ‘such as‘, ‘in order to‘, etc.

Back to Top

Interjections

Interjections are words such as ‘Yuck!‘, ‘Ugh!‘, and ‘Ouch!‘ which indicate the emotions, like disgust, fear, shock, delight, etc., of the person who utters them.

Back to Top

Prepositions

Prepositions are words which are used to link nouns, pronouns and gerunds ( the ‘-ing‘ form of a verb which is being used as a noun e.g. ‘At high level Swimming is a very demanding sport.’) to other words. They are often short words like ‘on‘, ‘in‘, ‘up‘, ‘down‘, ‘about‘, etc. They can consist of more than one word: in front of, next to, etc.

In TEFL we talk a lot about prepositions of time, place and movement:

|

Time |

I’ll see you at six o’clock. |

|

I’ll be home by five. |

|

|

We’re having a party on Christmas eve. |

|

|

Let’s have a party at Christmas. |

|

|

Place |

I’m in London at the moment. |

|

He’s at work, I’m afraid. |

|

|

The bookshop is on the second floor. |

|

|

She always leaves a key under the doormat. |

|

|

Movement |

She went to post office. |

|

He flew here from Guyana. |

|

|

He leapt over the gate. |

|

|

An elderly man was slowly climbing up the hill. |

These of course are not the only prepositions. The biggest problem for EFL students and therefore for their teachers is that it is almost impossible to predict which preposition combines with which verb, noun or adjective in any particular case, or even whether one is necessary at all. Here are some examples to demonstrate this point:

- agree with somebody about a subject but on a decision and to a suggestion,

- angry with somebody about something (at could also be used in both cases), or angry with/at somebody for doing something

- get/be married to somebody but marry somebody (no preposition)

- ‘pay for the tickets’, but ‘pay a bill’.

To a native speaker of English these may at first sight seem obvious, but to an EFL student they are impossible to guess. After all what is really wrong with *’get married on somebody’*? This would be perfectly correct in a number of languages. Even native speakers fail to agree on the use of some prepositions: Americans can say ‘Congratulations for your exam results!’, or ‘In America football is different than soccer.’ but these feel very wrong to the British, who would prefer to say ‘Congratulations on your exam results .’, and ‘In America football is different from soccer.’ Interestingly, British English does allow ‘different than‘ if it is followed by a clause e.g. The situation is different than I expected.’ It should be said, however, that the impact of Hollywood on British English seems to be gradually causing these differences to disappear.

Another complication is that it is often very difficult to know whether a word is, in fact, an adverb particle or a preposition as many can be either depending on the particular context in which they are found. This creates a problem in distinguishing between phrasal verbs and prepositional verbs. In the sentence ‘She fell off her chair.’ Off is a preposition while in the sentence ‘She turned off the radio.’ it is an adverb particle. Why is this so important? Well, lets take a moment to consider these two examples.

1. She turned off the radio.

What happens to the word order in the above sentence if we replace ‘the radio’ with the pronoun ‘it’? We have to place ‘it’ between the verb and its adverb particle — ‘She turned it off.’ We cannot say *’She turned off it.’* We can, however, say ‘She turned the radio off.’

2. She fell off her chair.

What if we do the same to this sentence? We get ‘She fell off it (because she was laughing so much).’ In this case, we cannot insert ‘it’ into the middle of the prepositional verb. Nor can we say *’She fell the chair off.’*

No problem for a native speaker, of course, they ‘know’ what is right, but what about the poor EFL student, who doesn’t have this ‘knowledge’? And what about the poor EFL teacher, who has to find some way to help their students with this?

No matter what language is being studied prepositions are always a problem.

End of Section 1 Parts of Speech

Back to Top

Foundation TEFL methodology course

80 HOURS OF INPUT

- Engaging & interactive assignments

- Based on decades of combined experience

- Learn anywhere at any time

EXPLORE THE WORLD OF TEACHING! TEACH, INSPIRE & GROW

AN-244

Phrasal Syntax

seminar

Marosán Lajos

Parts of Speech

Tarr Dániel

1995

Parts of Speech

Parts

of Speech are words classified

according to their functions in sentences, for purposes of traditional

grammatical analysis. According to traditional grammars eight parts of speech

are usually identified: nouns, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions,

pronouns, verbs, and interjections.

Noun girl, man, dog,

orange, truth …

Pronoun I, she, everyone,

nothing, who …

Verb be, become,

take, look, sing …

Adjective small, happy, young,

wooden …

Adverb slowly, very,

here, afterwards, nevertheless

Preposition at, in, by, on, for,

with, from, to …

Conjunction and, but, because,

although, while …

Interjection ouch, oh, alas, grrr,

psst …

Most

of the major language groups spoken today, notably the Indo-European languages

and Semitic languages, use almost the identical categories; Chinese, however,

has fewer parts of speech than English.[1]

The

part of speech classification is the center of all traditional grammars.

Traditional grammars generally provide short definitions for each part of

speech, while many modern grammars, using the same categories, refer to them as

“word-classes” or “form-classes”. To preface our discussion, we will do the

same:

Nouns

A noun

(Latin nomen, “name”) is usually defined as a word denoting a thing, place,

person, quality, or action and functioning in a sentence as the subject or

object of action expressed by a verb or as the object of a preposition. In

modern English, proper nouns, which are always capitalized and denote

individuals and personifications, are distinguished from common nouns. Nouns

and verbs may sometimes take the same form, as in Polynesian languages. Verbal

nouns, or gerunds, combine features of both parts of speech. They occur in the

Semitic and Indo-European languages and in English most commonly with words

ending in -ing.

Nouns

may be inflected to indicate gender (masculine, feminine, and neuter), number,

and case. In modern English, however, gender has been eliminated, and

only two forms, singular and plural, indicate number (how many perform or

receive an action). Some languages have three numbers: a singular form

(indicating, for example, one book), a plural form (indicating three or more

books), and a dual form (indicating, specifically, two books). English has

three cases of nouns: nominative (subject), genitive

(possessive), and objective (indicating the relationship between the

noun and other words).

Adjectives

An

adjective is a word that modifies, or qualifies, a noun or pronoun, in

one of three forms of comparative degree: positive (strong, beautiful), comparative

(stronger, more beautiful), or superlative (strongest, most beautiful).

In many languages, the form of an adjective changes to correspond with the

number and gender of the noun or pronoun it modifies.

Adverbs

An

adverb is a word that modifies a verb (he walked slowly), an adjective

(a very good book), or another adverb (he walked very slowly). Adverbs may

indicate place or direction (where, whence), time (ever,

immediately), degree (very, almost), manner (thus, and words

ending in —ly, such as wisely), and belief or doubt (perhaps,

no). Like adjectives, they too may be comparative (wisely, more wisely, most

wisely).

Prepositions

Words

that combine with a noun or pronoun to form a phrase are termed prepositions.

In languages such as Latin or German, they change the form of the noun or

pronoun to the objective case (as in the equivalent of the English

phrase “give to me”), or to the possessive case (as in the phrase “the

roof of the house”).

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are the words that connect sentences, clauses,

phrases, or words, and sometimes paragraphs. Coordinate conjunctions

(and, but, or, however, nevertheless, neither … nor) join independent clauses,

or parts of a sentence; subordinate conjunctions introduce subordinate

clauses (where, when, after, while, because, if, unless, since, whether).

Pronouns

A pronoun

is an identifying word used instead of a noun and inflected in the same way

nouns are. Personal pronouns, in English, are I, you, he/she/it, we, you

(plural), and they. Demonstrative pronouns are thus, that, and such.

Introducing questions, who and which are interrogative pronouns; when

introducing clauses they are called relative pronouns. Indefinite pronouns

are each, either, some, any, many, few, and all.

Verbs

Words

that express some form of action are called verbs. Their inflection,

known as conjugation, is simpler in English than in most other

languages. Conjugation in general involves changes of form according to person

and number (who and how many performed the action), tense (when

the action was performed), voice (indicating whether the subject of the

verb performed or received the action), and mood (indicating the frame

of mind of the performer). In English grammar, verbs have three moods: the indicative,

which expresses actuality; the subjunctive, which expresses contingency;

and the imperative, which expresses command (I walk; I might walk;

Walk!)

Certain

words, derived from verbs but not functioning as such, are called verbals.

In addition to verbal nouns, or gerunds, participles can serve as adjectives

(the written word), and infinitives often serve as nouns (to err is human).

Interjections

Interjections are exclamations such as oh, alas, ugh, or well (often

printed with an exclamation point). Used for emphasis or to express an

emotional reaction, they do not truly function as grammatical elements of a

sentence.[2]

It is useful to make a distinction and consider words as falling into two broad

categories; closed

class words and open class words. The former consists of classes that are finite (and

often small) with membership that is relatively stable and unchanging in the

language. These words play a major part in English grammar, often corresponding

to inflections in some other languages, and they are sometimes referred to as

‘grammatical words’, ‘function words’, or ‘structure words’. These terms also

stress their function in the grammatical sense, as structural markers, thus a

determiner typically signals the beginning of a noun phrase, a preposition the

beginning of a prepositional phrase, a conjunction the beginning of a clause. Closed

classes are: pronoun /she, they/, determiner /the, a/, primary

verb /be/, modal verb

/can, might/, preposition /in, of/, and conjunction /and, or/. Open classes are: noun /room, hospital/, adjective /happy, new/, full verb /grow, search/, and adverb /really, steadily/. To these two lesser

categories may be added: numerals /one, first/, and interjections /oh, aha/; and finally a small number of words

of unique function which do not easily fit into any of these classes /eg.: the negative particle not and the infinite

marker to/.

Quirk

and Greenbaum[3]point out the ambiguity of the term word, for

words are enrolled in their classes in their ‘dictionary form’, and not as they

might appear in sentences when they function as constituents of phrases. Since

words in their various grammatical forms appear in sentences that are normal

usage, it is more correct if we refer to them as lexical items. Thus, a lexical item is a word as it occurs in a

dictionary, where work, works, working, worked will all be counted as

different grammatical forms of the word work. This distinction however

is not always necessary, for it is only important with certain parts of speech

that have inflections; that is endings or modifications that change the

word-form into another. These are nouns /answer,

answers/, verbs /give, given/, pronouns /they, theirs/, adjectives

/large, largest/, and a few adverbs

/soon, sooner/ and determiners /few,

fewer/.

A word may belong to more than one class; for example round

is also a preposition /”drive round the corner”/ and an adjective

/”she has a round face”/. In such cases we can say that the same morphological form is a realization of more than one lexical item. A

morphological form may be simple, consisting of a stem only /eg.: play/,

or complex, consisting of more than one morpheme /eg.: playful/. The morphological form of a word is

therefore defined as composition of stems and affixes.

We

assign words to their various classes according to their properties in entering

phrasal or clausal structure. For example, determiners link up with nouns to

form noun phrases /eg.: a soldier/;

and pronouns can replace noun phrases /eg.:

him/. This is not to deny the general validity of traditional

definitions based on meaning. In fact it is impossible to separate grammatical

form from semantic factors. The distinction between generic /the tiger lives/ and specific /these tigers/, unmarked and marked

forms prove that.

Another

possible assignment is according to morphological characteristics, notably the

occurrence of derivational suffixes, which marks a word as a member of a

particular class. For example, the suffix -ness, marks an item as a noun

/kindness/, while the suffix -less marks an item as an adjective

/helpless/. Such indicators help to identify word classes without

semantic factors.

For

the sake of completeness, it should also be added that a word also has a phonological and an orthographic form. Words which share the same phonological or

orthographic “shape”, but are morphologically unrelated are called homonyms /eg.: rose

(noun) and rose (past tense verb)/. Words with the same pronunciation

are specified as homophones, and words with the same spelling are determined as homographs. Words which partake the same morphological form are

called homomorphs /eg.: meeting

(noun) and meeting (verb)/. There is also a correspondence between words

with different morphological form, but same meaning. These are called synonyms. Of the three major kinds of equivalence, homonymy is

phonological and/or graphic, and synonymy is semantic.

We have to go back to the distinction of closed-class items and open-class

items, because this introduces a peculiarity of great importance. That is, closed-class items are ‘closed’ in the sense that they cannot normally

be extended by the creation of additional members. For example, it is very

unlikely for a new pronoun to develop. It is also very easy to list all the

members in a closed class. These items are said to be constitute a system in

being mutually exclusive: the decision to use one item in a given structure

excludes the possibility of using any other /the book or a

book, but not *a the book/. These items are also reciprocally

defining in meaning: it is less easy to state the meaning of any individual

item than to define it in relation to the rest of the system.

By

contrast open

class items belong to a class in that

they have the same grammatical properties and structural possibilities as other

members of the class (that is, as other nouns or verbs or adjectives or

adverbs), but the class is ‘open’ in the sense that it is indefinitely

extendible. New items can be created and no inventory can be made that would be

complete. This ultimately affects the way in which we attempt to define any

item in an open class; because while it is possible to relate the meaning of a

noun to another with which it has semantic affinity /eg.: house = chamber/,

one could not define it as not house, which is possible with closed

class items /this = not that/.

However,

the distinction between ‘open’ and ‘closed’ parts of speech or word classes

must not be treated incautiously. On the on hand, it is not very easy to create

new words, and on the other, we must not overstate the extent to which we speak

of ‘closedness’, for new prepositions like by way of [4]are no means impossible. Although parts of speech have

deceptively specific labels, words tend to be rather heterogeneous. The adverb

and the verb are especially mixed classes, each having small and fairly well

defined groups of closed-system items alongside the indefinitely large

open-class items. So far as the verb is concerned, the closed-system subgroup

is known be the well established term “auxiliary”…

Some

mention must be finally made of two additional classes, numerals and interjections,

which are common in the difficulty of classifying them as either closed or open

classes. Numerals whether the cardinal numerals /one, two, three/,

or the ordinal numerals /first, second, third/, must be placed somewhere

between open-class and closed-class items: they resemble the former in that

they make up a class of infinite membership; but they resemble the latter in

that the semantic relations among them are mutually exclusive and mutually

defining. Interjections might be considered a closed class on the

grounds that those that are fully institutionalized are few in number. But

unlike the closed classes, they are grammatically peripheral — they do not

enter into constructions with other word classes, and they are only loosely

connected to sentences with which they may be orthographically or

phonologically associated.

A further and related contrast between words, is the distinction between stative

and dynamic. Broadly speaking, nouns can be characterized naturally

as ‘stative’ in that they refer to entities that are regarded as

stable, whether these are concrete /house, table/ or abstract /hope,

length/. On the other hand verbs and adverbs can equally naturally be

characterized as ‘dynamic’: verbs are fitted to indicate action, activity and

temporary or changing conditions; and adverbs in so far as they add a

particular condition of time, place, manner, etc. to the dynamic implication of

the verb.

But

it is not uncommon to find verbs which may be used either dynamically or

statively. If we say that “some specific tigers are living in a cramped

cage”, we imply that this is a temporary condition and the verb phrase is dynamic

in its use. On the other hand, when we say that “a species of animal known as

tiger lives in China”, the generic statement entails that this is not a

temporary circumstance and the verb phrase is stative. Moreover some verbs

cannot normally be used with the progressive aspect /*He is knowing English/

and therefore belong to the stative rather than the dynamic category. In

contrast to verbs, most nouns and adjectives are stative in that they denote a

phenomena or quality that is regarded for linguistic purposes as stable and

indeed for all practical purposes permanent /Jack is an engineer — Jack

is very tall/. Also adjectives can resemble verbs in referring to

transitionary conditions of behavior or activity. /He is being a nuisance

— He is being naughty/.

The names of the parts of speech are traditional, however, and neither in

themselves nor in relation to each other do these names give a safe guide to

their meaning, which instead is best understood in terms of their grammatical

properties. One fundamental relation is that grammar provides the means of

referring back to an expression without repeating it. This is achieved by means

of pro-forms. Participles and pronouns can serve

as replacements for a noun /the big

room and the small one/, more

usually, however, pronouns replace noun phrases rather than nouns /their beautiful new car was badly damaged when it was struck be a

falling tree/.

The

relationship which often obtains between a pronoun and its antecedent is not

one which can be explained by the simple act of replacement. In some

constructions we have repetition, which are by no means equivalent in meaning /Many students

did better than many students expected/. In some constructions repetition can be avoided by ellipsis /They hoped they would play a Mozart quartet and

they will/. Therefore the general term

pro-form is best applied to words and word sequences which are essentially

devices for rephrasing or anticipating the content of a neighboring expression,

often with the effect of grammatical complexity.

Such

devices are not limited to pronouns and participles: the word such can

described as a pro-form as there are pro-forms also for place, time and other

adverbials under certain circumstances /M.is

in London and J. is there too/.

In older English and still sometimes in very formal English we find thus and so

used as pro-forms for adverbials /He

often behaved silly, but he did not always behave thus/so/. But so has a more important function in

modern usage, namely to substitute with the ‘pro-verb’ do for a main

verb and whatever follows it in the clause /He

wished they would take him seriously for his ideas, but unfortunately

they didn’t do so/. Do can also

act as pro-form on its own /I told him

about it — I did too/.

Some

pro-forms can refer forward to what not been stated rather than back to what

has been stated. These are the wh-items. Indeed, wh-words,

including what, which, who and when, may be

regarded as a special set of pro-forms /Where is M.? — M. is in London. — J. is there too/. The paraphrase for wh-words is broad enough

to explain also their use in subordinate clauses /I wonder what M. thinks/. Through the use of wh-words we can ask for

the identification of subject, object, complement or adverbial of a sentence /They [S] make [V] him [O] the chairman [C] every year

[A]. — Who [S] makes him…?/.

Now that we have outlined the various aspects of Parts of Speech, according to

traditional grammars, we will look at some other approaches and other

specifications, without the sake of complexity, only to widen our views a

little more on the subject:

Otto Jespersen[5]starts out from the point that all clauses consist of

several words. One word is defined or modified by another word, which in turn

may be defined or modified by a third word. This leads to the establishment of

different ranks of words according to their mutual relations as defined or

defining. In the combination “extremely hot weather” weather may

be called a primary word or principal; hot