Continue Learning about English Language Arts

What part of speech is the word my-?

The part of speech that the word my is used as is an

adjective.

What part of the speech is the word warily?

what part of speech is the word warily

Does a dictionary determine the part of speech of a word?

A dictionary can show a word’s part of speech, but it does not

determine it. How a word is used in a sentence determines its part

of speech.

What part of speech is the word specifically?

The part of speech for the word specifically is an adverb.

What part of speech is the word law?

The part of speech for law is a noun.

- Dictionary

- S

- Some

- Parts of Speech for Some

Parts of Speech for Some

some

S s

Gramatical Hierarchy

- Adjective

- Noun

- Noun modifier

- Quantifier

- Adverb

- Pronoun

Grammatically «Some» is a adjective, to be more precise even a quantifier. But also it is used as a noun, specifically a quantifier. Part of speech depends on meaning of this word.

All about some Download all about some in pdf

Which part of speech is the word some?

Parts of Speech Table

| part of speech | function or “job” | example words |

|---|---|---|

| Determiner | limits or “determines” a noun | a/an, the, 2, some, many |

| Adverb | describes a verb, adjective or adverb | quickly, silently, well, badly, very, really |

| Pronoun | replaces a noun | I, you, he, she, some |

| Preposition | links a noun to another word | to, at, after, on, but |

What is some in English grammar?

The general rule is that any is used for questions and negatives while some is used for positive. Both may be used with countable and uncountable nouns. Some may also be used for questions, typically offers and requests, if we think the answer will be positive. …

Why do we use any?

We use any to mean ‘it does not matter which or what’, to describe something which is not limited. We use this meaning of any with all types of nouns and usually in affirmative sentences.

How do you use any in a sentence?

In general, any is used in negative sentences and questions:

- I didn’t get any nice presents for Christmas this year.

- I looked in the cupboard but I couldn’t find any biscuits.

- I don’t need any help.

- She’s so rude.

- I don’t have anything to wear to the dance.

- I’m not hungry.

- Do you have any brothers or sisters?

What means any%?

(video games) A category in speedrunning which pertains to the goal of a game’s mere completion, i.e. getting to the main concluding goal as quickly as possible, regardless of how much is unlocked.

How do you explain the word any?

(Entry 1 of 3) 1 : one or some indiscriminately of whatever kind: a : one or another taken at random Ask any man you meet. b : every —used to indicate one selected without restriction Any child would know that.

What does the word of mean?

(Entry 1 of 3) 1 —used as a function word to indicate a point of reckoning north of the lake. 2a —used as a function word to indicate origin or derivation a man of noble birth. b —used as a function word to indicate the cause, motive, or reason died of flu.

Do you have any money answer?

When talking about quantity, or how much there is of something, the two most important words are any and some. “Any” is generally used to ask if there is more than one of something. This kind of question is a “yes no” question, meaning that the answer is “yes” or “no”: “Do you have any money?” (No, I don’t.)

Is much money correct?

‘Money’ and ‘cash’ are uncountable nouns, whereas ‘notes’ and ‘coins’ are countable nouns. It’s incorrect to use the adjective ‘many’ before uncountable nouns like money,cash, rice, oil etc. Therefore ‘how much money ‘ is correct.

Did you get or have you got?

“Get” is the present tense form of the verb and “got” is the past tense form, but the tenses are often used interchangeably. In informal speech, people often question each other with “Do you get it?” or just “Get it?” to check for comprehension. “I get it” or “I got it” are both logical answers.

Did you get or got my message?

“Did you receive my message” is correct. This is simple past tense. “Have you received my message” is also correct. This is present perfect tense and could be used in a conversation that is going on.

Did you get a chance or have you got a chance?

It essentially implies that being able to do something is mostly out of your control. Asking “Have you got a chance to look into this?” would imply that “looking into this” is something that one is unlikely to do with out a lot of luck.

Did anyone got or get?

“Did I get” is correct . “Did I got” is incorrect because both did and got are in past tense. Get is the principal verb and do is the auxiliary or helping verb. ‘Did’ is the past tense of ‘do’.

When I use get or got?

Get is the present tense form of the verb. Got is the past tense form as well as one of the two alternatives for the past participle. In informal contexts, many speakers use have got, ‘ve got, or simply got to mean “have” or “must.” You should avoid this usage of the verb get in your writing; instead, use have or must.

What to say instead of got it?

What is another word for got it?

| you see | am I getting my point across |

|---|---|

| do you get me | do you understand |

| get it | understood |

| you feel me |

Is got a proper word?

In American English, most dictionaries allow “got” as the past participle but prefer “gotten.” Today I get well. In recent years, Dana has had the good sense to look this word up in the dictionary: “I see it has become accepted, so there is now such a word.”

Is got a slang word?

Many listeners, including Sigrid, have been wondering if the phrase “have got” is acceptable English. Well, you have got to check out our previous episode on that topic. It’ll tell you that the answer is yes, you can use this expression, though it is considered informal.

Is the word get bad?

Short Answer: No, “get” is not always bad. Longer Answer: “get” and its derivatives have many meanings and uses.

Is have gotten correct grammar?

5 Answers. In general, “have got” is the present perfect form of “to get” in UK English, while “have gotten” is the US English version. However, even in US English, “have got” is used in certain instances, namely to mean present tense have (in the sense of possession, or to mean must): I have got a lot of friends.

Is haven’t gotten proper English?

“I haven´t got” is a gramatically correct literal translation into English although not belletristically ideal. “Gotten” is American colloquial slang and not good English.

What is poor grammar?

Poor grammar overall is not being able to spell words correctly,Not using tenses correctly,not structuring sentences correctly, etc.

What is a grammatically correct sentence?

In order for a sentence to be grammatically correct, the subject and verb must both be singular or plural. In other words, the subject and verb must agree with one another in their tense.

It is a fact that almost every word of English has got the capacity to be employed as a different part of speech. At one place, a particular word may be used as a noun, at another as a verb, and yet at another place as an adjective.

These words enable the learners of the English language to understand the behavior of a particular word in various positions.

Importance of Parts of Speech in Communication

As you know, English sentences are used to communicate a complete thought. The importance of parts of speech lies in their proper utilization, which can help your understanding and confidence grow immensely.

Proper usage of parts of speech means that you can impart clear messages and understand them because you know the rules of the language.

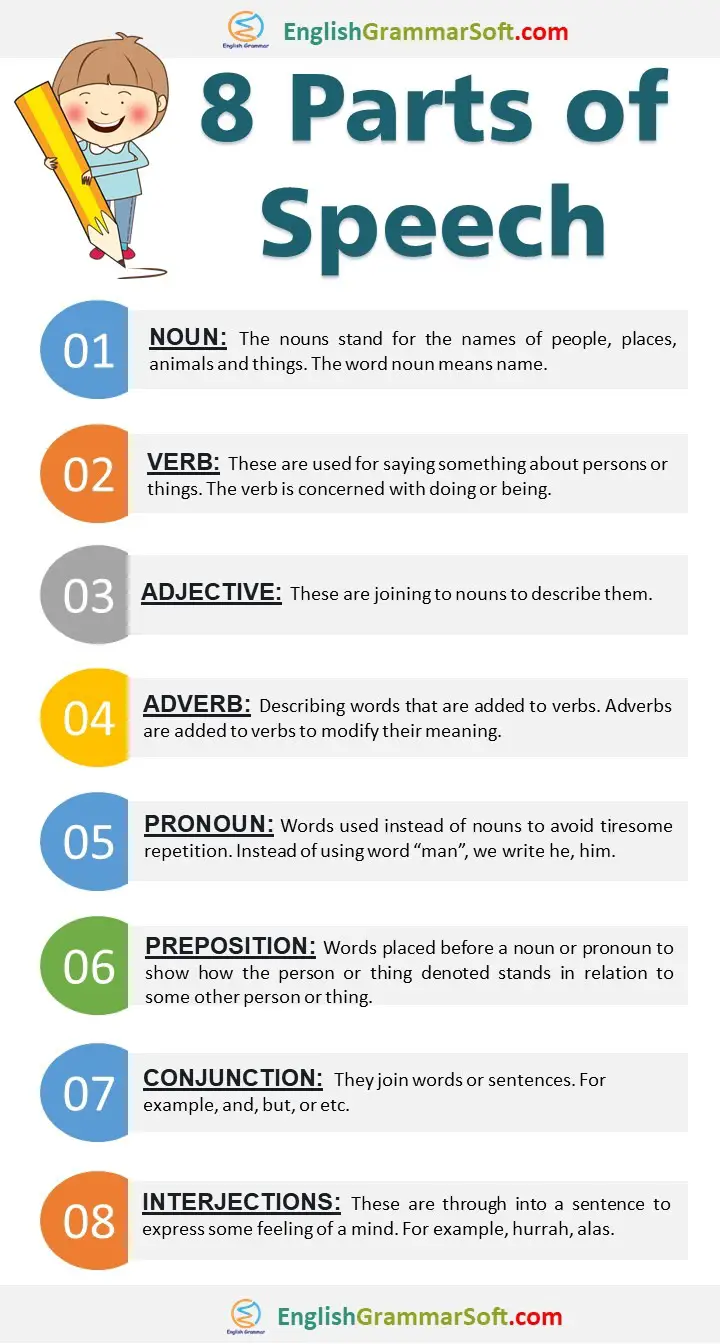

Each word in a sentence belongs to one of the eight parts of speech according to the work it is doing in that sentence. There are 8 parts of speech.

- Noun

- Verb

- Adjective

- Adverb

- Pronoun

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

1 – Noun (Naming words)

The nouns stand for the names of people, places, animals, and things. The word noun means name. Look at these sentences.

“John lives in Chicago. He has two bikes. He is fond of riding bikes.”

In the above example, John is the name. We cannot use the same name again and again in different sentences. Here, we used “he” in the next two sentences instead of “John”. “He” is called the pronoun.

Types of nouns are

1.1 – Common Noun

It describes a person, place, and thing.

Examples: City, country, town, boy.

1.2 – Proper Noun

It includes a particular person, place, thing, or idea and begins with a capital letter.

Examples: Austria, Manchester, United Kingdom, etc.

1.3 – Abstract Noun

An abstract noun describes names, ideas, feelings, emotions or qualities, the subject of any paragraph comes under this category. It does not take “the”.

Examples: grief, loss, happiness, greatness.

1.4 – Concrete Noun

It describes material things, persons or places. The existence of that thing can be physically observed.

Examples: Book, table, car, etc.

1.5 – Countable and Uncountable Noun

Countable nouns can be singular or plural. It can be counted.

Examples: Ships, cars, buses, books, etc.

The uncountable noun is neither singular nor plural. It cannot be counted.

Examples: Water, milk, juice, butter, music, etc.

1.6 – Collective Noun

It includes the group and collection

people, things or ideas. It is in unit form and is considered as singular.

Examples: Staff of office, group of visitors.

However, people and police can be

considered both singular and plural.

1.7 – Possessive Noun

It shows ownership or relationship.

Examples: Jimmy’s pen.

Further Reading: 11 Types of Nouns with Examples

2 – Verb (Saying words)

These are used for saying something

about persons or things. The verb is concerned with doing or being.

Examples

- A hare runs (action) very fast.

- Aslam is a good student.

Types of verbs

2.1 – Actions verbs

(run, move, write etc)

2.2 – Linking verbs

(to be (is, am, are, was, were), seem, feel, look, understand)

2.3 – Auxiliary (helping) verbs

(have, do, be)

2.4 – Modal Verbs

(can, could, may, might, will/shall)

2.5 – Transitive verbs

It takes an object.

Example – He is reading a newspaper.

2.6 – Intransitive verbs

It does not take the object.

Example – He awakes.

Further Reading: What are the verbs in English?

3 – Adjectives (describing words)

These are joining to nouns to describe

them.

Examples

- A hungry wolf.

- A brown wolf.

- A lazy boy.

- A tall man.

It is used before a noun and after a linking verb.

Before noun example

A new brand has been launched.

After linking verb example

Imran is rich.

It is used to clarify nouns.

Example: smart boy, blind man

Types of adjectives

3.1 – Simple degree

He is intelligent.

3.2 – Comparative

Ali is intelligent than Imran.

3.3 – Superlative

Comparison of one person with class,

country or world. In this type “the” is used.

Example: Ali is the wisest boy.

3.4 – Demonstrative adjective

It points out a noun. These are four

in number.

This That These Those

3.5 – Indefinite adjectives

It points out nouns. They often tell

“how many” or “how much” of something.

Interrogative adjectives: it is used to ask questions

Examples

- Which book?

- What time?

- Whose car?

Further Reading: More About Adjectives

4 – Adverbs

Describing words that are added to verbs. Just as adjectives are added to describe them, adverbs are added to verbs to modify their meaning. The word “modify” means to enlarge the meaning of the adverbs.

Examples

- Emma sings beautifully. (used with verb)

- Cameron is extremely clever. (used with adjective)

- This motor car goes incredibly fast. (used with another adverb)

Types of adverb

4.1 – Adverb of manner

This type of adverb deals with the

action something

Example

- I walk quickly.

- He wrote slowly.

4.2 – Adverb of place

Happening of something or the place where it happens.

Examples:

There was somebody sitting nearby.

Here, these, upstairs, nowhere everywhere, outside, in, out, are called adverb of place.

4.3 – Adverb of time

It determines the time of the happening of something.

Examples

- She went there last night.

- Have you seen him before?

- He wrote a letter yesterday.

Tomorrow, today, now, then,

yesterday, already, ago.

4.4 – Linking adverbs (then, however)

It creates a connection between two clauses or sentences.

Example

There will be clouds in Lahore. However, the sun is expected in Multan.

Note: Besides modifying the meaning of a verb, adverbs also modify adjectives and other adverbs.

Examples

- It is a very large house.

- He is too weak to walk.

- He ran too fast.

Further Reading: 11 Types of Adverbs with Examples

5 – Pronouns

Words that are used instead of nouns to avoid tiresome repetition. Instead of using the word man in a composition, we often write he, him, himself. In place of the word “woman”, we write she, her, or herself. For both the nouns ‘men’ and ‘women’ we use, they, them, themselves.

Some of the most common pronouns are

Singular: I, he, she, it, me, him,

her

Plural: We, they, out, us, them.

Examples

Imran was hurt. He didn’t panic.

He checked the mobile. It still

worked.

Types of Pronouns

It stands instead of persons. They have different forms according to the person who is supposed to be speaking.

First person: I, we, me, us, mine, our, ourselves.

Second person: thou, you, there.

Third person: He, she, it, his, him

5.1 – Possessive pronouns

Such as mine, ours, yours, hers and theirs.

- This book is mine.

- My horse and yours are tired.

5.2 – Relative pronoun

Who, whom, which and they are called relative pronouns. They are called relative because they relate to some word in the main clause. The word to which pronoun relates is called the antecedent.

Example

I saw a boy who was going.

In this sentence, who is the relative pronoun and boy is its antecedent.

This is the girl who won the prize.

“which” is used for animals and things.

The dog which barks.

That is used instead of who or which in this case.

This is the best picture that I ever saw.

5.3 – Interrogative pronouns

It is used to introduce or create an asking position in a sentence. Who, whom, which, and whose are interrogative pronouns.

Examples

Who wrote this book? (for persons

only)

What is your name? (for things)

Which boy here is your friend?

5.4 – Demonstrative pronoun

It points out a person, thing, place

or idea. This, that, these and those are called demonstrative pronouns.

That is a circuit-breaker.

These are cups of a team.

5.5 – Reflexive pronoun

The type of pronoun that ends in self or selves is called a reflexive pronoun.

Examples: myself, ourselves, yourself, herself, himself, itself, themselves.

Use in sentence: They worked hard to

get out themselves from the debt.

Indefinite pronoun: An indefinite

pronoun does not refer to a specific person, place thing or idea.

Examples

Nothing lasts forever.

No one can make this design.

Further Reading: Different Types of Pronouns with 60+ Examples

6 – Prepositions

Words placed before a noun or pronoun

to show how the person or thing denoted stands in relation to some other person

or thing.

Examples: A house on a hill. Here, the word “on” is a preposition.

The noun and pronoun that follow the preposition are called its object. We can identify prepositions in the following examples.

In 2006, in March, in the garden,

On 14th August, on Friday, on the table

At 8:30 pm, at 9 o’clock, at the door, at noon, at night, at midnight

However, we use “in” for morning and evening.

Further Reading: Preposition Usage and Examples

7 – Conjunctions (joining words)

They join words or sentences.

Examples: Jimmy and Tom are good players.

In the above sentence, “and” is a conjunction.

Types of conjunctions

These are the types of conjunctions.

- Nor (used in later part of the negative sentence)

- But (when two different ideas are described in a sentence)

- Yet (when two contrast things are being described in a sentence)

- So (To explain the reason)

- For (it connects a reason to a result)

- Or (to adopt two equal choices)

- And (to join two things or work)

Further Reading: Conjunction Rules with Examples

8 – Interjections

Interjection words are not connected with other parts of a sentence. They are through into a sentence to express some feeling of a mind.

Examples: Hurrah! We won the match.

Alas, hurrah, wow, uh, oh-no, gush, shh are some words used to express the feeling.

It is important to note that placing a word in this or that part of speech is not fixed. It depends upon the work the words are doing in a particular sentence. Thus the same word may appear in three or four parts of speech.

Further Reading: More about Interjections

You can read a detailed article about parts of speech here.

Parts of Speech Exercise with Answers

Read also: 71 Idioms with Meaning and Sentences

A part of speech is a term used in traditional grammar for one of the nine main categories into which words are classified according to their functions in sentences, such as nouns or verbs. Also known as word classes, these are the building blocks of grammar.

Parts of Speech

- Word types can be divided into nine parts of speech:

- nouns

- pronouns

- verbs

- adjectives

- adverbs

- prepositions

- conjunctions

- articles/determiners

- interjections

- Some words can be considered more than one part of speech, depending on context and usage.

- Interjections can form complete sentences on their own.

Every sentence you write or speak in English includes words that fall into some of the nine parts of speech. These include nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, articles/determiners, and interjections. (Some sources include only eight parts of speech and leave interjections in their own category.)

Learning the names of the parts of speech probably won’t make you witty, healthy, wealthy, or wise. In fact, learning just the names of the parts of speech won’t even make you a better writer. However, you will gain a basic understanding of sentence structure and the English language by familiarizing yourself with these labels.

Open and Closed Word Classes

The parts of speech are commonly divided into open classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) and closed classes (pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articles/determiners, and interjections). The idea is that open classes can be altered and added to as language develops and closed classes are pretty much set in stone. For example, new nouns are created every day, but conjunctions never change.

In contemporary linguistics, the label part of speech has generally been discarded in favor of the term word class or syntactic category. These terms make words easier to qualify objectively based on word construction rather than context. Within word classes, there is the lexical or open class and the function or closed class.

Read about each part of speech below and get started practicing identifying each.

Noun

Nouns are a person, place, thing, or idea. They can take on a myriad of roles in a sentence, from the subject of it all to the object of an action. They are capitalized when they’re the official name of something or someone, called proper nouns in these cases. Examples: pirate, Caribbean, ship, freedom, Captain Jack Sparrow.

Pronoun

Pronouns stand in for nouns in a sentence. They are more generic versions of nouns that refer only to people. Examples: I, you, he, she, it, ours, them, who, which, anybody, ourselves.

Verb

Verbs are action words that tell what happens in a sentence. They can also show a sentence subject’s state of being (is, was). Verbs change form based on tense (present, past) and count distinction (singular or plural). Examples: sing, dance, believes, seemed, finish, eat, drink, be, became

Adjective

Adjectives describe nouns and pronouns. They specify which one, how much, what kind, and more. Adjectives allow readers and listeners to use their senses to imagine something more clearly. Examples: hot, lazy, funny, unique, bright, beautiful, poor, smooth.

Adverb

Adverbs describe verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs. They specify when, where, how, and why something happened and to what extent or how often. Examples: softly, lazily, often, only, hopefully, softly, sometimes.

Preposition

Prepositions show spacial, temporal, and role relations between a noun or pronoun and the other words in a sentence. They come at the start of a prepositional phrase, which contains a preposition and its object. Examples: up, over, against, by, for, into, close to, out of, apart from.

Conjunction

Conjunctions join words, phrases, and clauses in a sentence. There are coordinating, subordinating, and correlative conjunctions. Examples: and, but, or, so, yet, with.

Articles and Determiners

Articles and determiners function like adjectives by modifying nouns, but they are different than adjectives in that they are necessary for a sentence to have proper syntax. Articles and determiners specify and identify nouns, and there are indefinite and definite articles. Examples: articles: a, an, the; determiners: these, that, those, enough, much, few, which, what.

Some traditional grammars have treated articles as a distinct part of speech. Modern grammars, however, more often include articles in the category of determiners, which identify or quantify a noun. Even though they modify nouns like adjectives, articles are different in that they are essential to the proper syntax of a sentence, just as determiners are necessary to convey the meaning of a sentence, while adjectives are optional.

Interjection

Interjections are expressions that can stand on their own or be contained within sentences. These words and phrases often carry strong emotions and convey reactions. Examples: ah, whoops, ouch, yabba dabba do!

How to Determine the Part of Speech

Only interjections (Hooray!) have a habit of standing alone; every other part of speech must be contained within a sentence and some are even required in sentences (nouns and verbs). Other parts of speech come in many varieties and may appear just about anywhere in a sentence.

To know for sure what part of speech a word falls into, look not only at the word itself but also at its meaning, position, and use in a sentence.

For example, in the first sentence below, work functions as a noun; in the second sentence, a verb; and in the third sentence, an adjective:

- Bosco showed up for work two hours late.

- The noun work is the thing Bosco shows up for.

- He will have to work until midnight.

- The verb work is the action he must perform.

- His work permit expires next month.

- The attributive noun [or converted adjective] work modifies the noun permit.

Learning the names and uses of the basic parts of speech is just one way to understand how sentences are constructed.

Dissecting Basic Sentences

To form a basic complete sentence, you only need two elements: a noun (or pronoun standing in for a noun) and a verb. The noun acts as a subject and the verb, by telling what action the subject is taking, acts as the predicate.

- Birds fly.

In the short sentence above, birds is the noun and fly is the verb. The sentence makes sense and gets the point across.

You can have a sentence with just one word without breaking any sentence formation rules. The short sentence below is complete because it’s a command to an understood «you».

- Go!

Here, the pronoun, standing in for a noun, is implied and acts as the subject. The sentence is really saying, «(You) go!»

Constructing More Complex Sentences

Use more parts of speech to add additional information about what’s happening in a sentence to make it more complex. Take the first sentence from above, for example, and incorporate more information about how and why birds fly.

- Birds fly when migrating before winter.

Birds and fly remain the noun and the verb, but now there is more description.

When is an adverb that modifies the verb fly. The word before is a little tricky because it can be either a conjunction, preposition, or adverb depending on the context. In this case, it’s a preposition because it’s followed by a noun. This preposition begins an adverbial phrase of time (before winter) that answers the question of when the birds migrate. Before is not a conjunction because it does not connect two clauses.

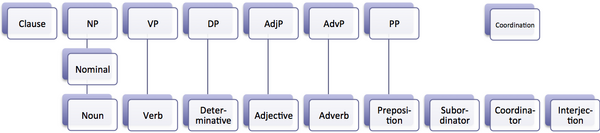

AN-244

Phrasal Syntax

seminar

Marosán Lajos

Parts of Speech

Tarr Dániel

1995

Parts of Speech

Parts

of Speech are words classified

according to their functions in sentences, for purposes of traditional

grammatical analysis. According to traditional grammars eight parts of speech

are usually identified: nouns, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions,

pronouns, verbs, and interjections.

Noun girl, man, dog,

orange, truth …

Pronoun I, she, everyone,

nothing, who …

Verb be, become,

take, look, sing …

Adjective small, happy, young,

wooden …

Adverb slowly, very,

here, afterwards, nevertheless

Preposition at, in, by, on, for,

with, from, to …

Conjunction and, but, because,

although, while …

Interjection ouch, oh, alas, grrr,

psst …

Most

of the major language groups spoken today, notably the Indo-European languages

and Semitic languages, use almost the identical categories; Chinese, however,

has fewer parts of speech than English.[1]

The

part of speech classification is the center of all traditional grammars.

Traditional grammars generally provide short definitions for each part of

speech, while many modern grammars, using the same categories, refer to them as

“word-classes” or “form-classes”. To preface our discussion, we will do the

same:

Nouns

A noun

(Latin nomen, “name”) is usually defined as a word denoting a thing, place,

person, quality, or action and functioning in a sentence as the subject or

object of action expressed by a verb or as the object of a preposition. In

modern English, proper nouns, which are always capitalized and denote

individuals and personifications, are distinguished from common nouns. Nouns

and verbs may sometimes take the same form, as in Polynesian languages. Verbal

nouns, or gerunds, combine features of both parts of speech. They occur in the

Semitic and Indo-European languages and in English most commonly with words

ending in -ing.

Nouns

may be inflected to indicate gender (masculine, feminine, and neuter), number,

and case. In modern English, however, gender has been eliminated, and

only two forms, singular and plural, indicate number (how many perform or

receive an action). Some languages have three numbers: a singular form

(indicating, for example, one book), a plural form (indicating three or more

books), and a dual form (indicating, specifically, two books). English has

three cases of nouns: nominative (subject), genitive

(possessive), and objective (indicating the relationship between the

noun and other words).

Adjectives

An

adjective is a word that modifies, or qualifies, a noun or pronoun, in

one of three forms of comparative degree: positive (strong, beautiful), comparative

(stronger, more beautiful), or superlative (strongest, most beautiful).

In many languages, the form of an adjective changes to correspond with the

number and gender of the noun or pronoun it modifies.

Adverbs

An

adverb is a word that modifies a verb (he walked slowly), an adjective

(a very good book), or another adverb (he walked very slowly). Adverbs may

indicate place or direction (where, whence), time (ever,

immediately), degree (very, almost), manner (thus, and words

ending in —ly, such as wisely), and belief or doubt (perhaps,

no). Like adjectives, they too may be comparative (wisely, more wisely, most

wisely).

Prepositions

Words

that combine with a noun or pronoun to form a phrase are termed prepositions.

In languages such as Latin or German, they change the form of the noun or

pronoun to the objective case (as in the equivalent of the English

phrase “give to me”), or to the possessive case (as in the phrase “the

roof of the house”).

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are the words that connect sentences, clauses,

phrases, or words, and sometimes paragraphs. Coordinate conjunctions

(and, but, or, however, nevertheless, neither … nor) join independent clauses,

or parts of a sentence; subordinate conjunctions introduce subordinate

clauses (where, when, after, while, because, if, unless, since, whether).

Pronouns

A pronoun

is an identifying word used instead of a noun and inflected in the same way

nouns are. Personal pronouns, in English, are I, you, he/she/it, we, you

(plural), and they. Demonstrative pronouns are thus, that, and such.

Introducing questions, who and which are interrogative pronouns; when

introducing clauses they are called relative pronouns. Indefinite pronouns

are each, either, some, any, many, few, and all.

Verbs

Words

that express some form of action are called verbs. Their inflection,

known as conjugation, is simpler in English than in most other

languages. Conjugation in general involves changes of form according to person

and number (who and how many performed the action), tense (when

the action was performed), voice (indicating whether the subject of the

verb performed or received the action), and mood (indicating the frame

of mind of the performer). In English grammar, verbs have three moods: the indicative,

which expresses actuality; the subjunctive, which expresses contingency;

and the imperative, which expresses command (I walk; I might walk;

Walk!)

Certain

words, derived from verbs but not functioning as such, are called verbals.

In addition to verbal nouns, or gerunds, participles can serve as adjectives

(the written word), and infinitives often serve as nouns (to err is human).

Interjections

Interjections are exclamations such as oh, alas, ugh, or well (often

printed with an exclamation point). Used for emphasis or to express an

emotional reaction, they do not truly function as grammatical elements of a

sentence.[2]

It is useful to make a distinction and consider words as falling into two broad

categories; closed

class words and open class words. The former consists of classes that are finite (and

often small) with membership that is relatively stable and unchanging in the

language. These words play a major part in English grammar, often corresponding

to inflections in some other languages, and they are sometimes referred to as

‘grammatical words’, ‘function words’, or ‘structure words’. These terms also

stress their function in the grammatical sense, as structural markers, thus a

determiner typically signals the beginning of a noun phrase, a preposition the

beginning of a prepositional phrase, a conjunction the beginning of a clause. Closed

classes are: pronoun /she, they/, determiner /the, a/, primary

verb /be/, modal verb

/can, might/, preposition /in, of/, and conjunction /and, or/. Open classes are: noun /room, hospital/, adjective /happy, new/, full verb /grow, search/, and adverb /really, steadily/. To these two lesser

categories may be added: numerals /one, first/, and interjections /oh, aha/; and finally a small number of words

of unique function which do not easily fit into any of these classes /eg.: the negative particle not and the infinite

marker to/.

Quirk

and Greenbaum[3]point out the ambiguity of the term word, for

words are enrolled in their classes in their ‘dictionary form’, and not as they

might appear in sentences when they function as constituents of phrases. Since

words in their various grammatical forms appear in sentences that are normal

usage, it is more correct if we refer to them as lexical items. Thus, a lexical item is a word as it occurs in a

dictionary, where work, works, working, worked will all be counted as

different grammatical forms of the word work. This distinction however

is not always necessary, for it is only important with certain parts of speech

that have inflections; that is endings or modifications that change the

word-form into another. These are nouns /answer,

answers/, verbs /give, given/, pronouns /they, theirs/, adjectives

/large, largest/, and a few adverbs

/soon, sooner/ and determiners /few,

fewer/.

A word may belong to more than one class; for example round

is also a preposition /”drive round the corner”/ and an adjective

/”she has a round face”/. In such cases we can say that the same morphological form is a realization of more than one lexical item. A

morphological form may be simple, consisting of a stem only /eg.: play/,

or complex, consisting of more than one morpheme /eg.: playful/. The morphological form of a word is

therefore defined as composition of stems and affixes.

We

assign words to their various classes according to their properties in entering

phrasal or clausal structure. For example, determiners link up with nouns to

form noun phrases /eg.: a soldier/;

and pronouns can replace noun phrases /eg.:

him/. This is not to deny the general validity of traditional

definitions based on meaning. In fact it is impossible to separate grammatical

form from semantic factors. The distinction between generic /the tiger lives/ and specific /these tigers/, unmarked and marked

forms prove that.

Another

possible assignment is according to morphological characteristics, notably the

occurrence of derivational suffixes, which marks a word as a member of a

particular class. For example, the suffix -ness, marks an item as a noun

/kindness/, while the suffix -less marks an item as an adjective

/helpless/. Such indicators help to identify word classes without

semantic factors.

For

the sake of completeness, it should also be added that a word also has a phonological and an orthographic form. Words which share the same phonological or

orthographic “shape”, but are morphologically unrelated are called homonyms /eg.: rose

(noun) and rose (past tense verb)/. Words with the same pronunciation

are specified as homophones, and words with the same spelling are determined as homographs. Words which partake the same morphological form are

called homomorphs /eg.: meeting

(noun) and meeting (verb)/. There is also a correspondence between words

with different morphological form, but same meaning. These are called synonyms. Of the three major kinds of equivalence, homonymy is

phonological and/or graphic, and synonymy is semantic.

We have to go back to the distinction of closed-class items and open-class

items, because this introduces a peculiarity of great importance. That is, closed-class items are ‘closed’ in the sense that they cannot normally

be extended by the creation of additional members. For example, it is very

unlikely for a new pronoun to develop. It is also very easy to list all the

members in a closed class. These items are said to be constitute a system in

being mutually exclusive: the decision to use one item in a given structure

excludes the possibility of using any other /the book or a

book, but not *a the book/. These items are also reciprocally

defining in meaning: it is less easy to state the meaning of any individual

item than to define it in relation to the rest of the system.

By

contrast open

class items belong to a class in that

they have the same grammatical properties and structural possibilities as other

members of the class (that is, as other nouns or verbs or adjectives or

adverbs), but the class is ‘open’ in the sense that it is indefinitely

extendible. New items can be created and no inventory can be made that would be

complete. This ultimately affects the way in which we attempt to define any

item in an open class; because while it is possible to relate the meaning of a

noun to another with which it has semantic affinity /eg.: house = chamber/,

one could not define it as not house, which is possible with closed

class items /this = not that/.

However,

the distinction between ‘open’ and ‘closed’ parts of speech or word classes

must not be treated incautiously. On the on hand, it is not very easy to create

new words, and on the other, we must not overstate the extent to which we speak

of ‘closedness’, for new prepositions like by way of [4]are no means impossible. Although parts of speech have

deceptively specific labels, words tend to be rather heterogeneous. The adverb

and the verb are especially mixed classes, each having small and fairly well

defined groups of closed-system items alongside the indefinitely large

open-class items. So far as the verb is concerned, the closed-system subgroup

is known be the well established term “auxiliary”…

Some

mention must be finally made of two additional classes, numerals and interjections,

which are common in the difficulty of classifying them as either closed or open

classes. Numerals whether the cardinal numerals /one, two, three/,

or the ordinal numerals /first, second, third/, must be placed somewhere

between open-class and closed-class items: they resemble the former in that

they make up a class of infinite membership; but they resemble the latter in

that the semantic relations among them are mutually exclusive and mutually

defining. Interjections might be considered a closed class on the

grounds that those that are fully institutionalized are few in number. But

unlike the closed classes, they are grammatically peripheral — they do not

enter into constructions with other word classes, and they are only loosely

connected to sentences with which they may be orthographically or

phonologically associated.

A further and related contrast between words, is the distinction between stative

and dynamic. Broadly speaking, nouns can be characterized naturally

as ‘stative’ in that they refer to entities that are regarded as

stable, whether these are concrete /house, table/ or abstract /hope,

length/. On the other hand verbs and adverbs can equally naturally be

characterized as ‘dynamic’: verbs are fitted to indicate action, activity and

temporary or changing conditions; and adverbs in so far as they add a

particular condition of time, place, manner, etc. to the dynamic implication of

the verb.

But

it is not uncommon to find verbs which may be used either dynamically or

statively. If we say that “some specific tigers are living in a cramped

cage”, we imply that this is a temporary condition and the verb phrase is dynamic

in its use. On the other hand, when we say that “a species of animal known as

tiger lives in China”, the generic statement entails that this is not a

temporary circumstance and the verb phrase is stative. Moreover some verbs

cannot normally be used with the progressive aspect /*He is knowing English/

and therefore belong to the stative rather than the dynamic category. In

contrast to verbs, most nouns and adjectives are stative in that they denote a

phenomena or quality that is regarded for linguistic purposes as stable and

indeed for all practical purposes permanent /Jack is an engineer — Jack

is very tall/. Also adjectives can resemble verbs in referring to

transitionary conditions of behavior or activity. /He is being a nuisance

— He is being naughty/.

The names of the parts of speech are traditional, however, and neither in

themselves nor in relation to each other do these names give a safe guide to

their meaning, which instead is best understood in terms of their grammatical

properties. One fundamental relation is that grammar provides the means of

referring back to an expression without repeating it. This is achieved by means

of pro-forms. Participles and pronouns can serve

as replacements for a noun /the big

room and the small one/, more

usually, however, pronouns replace noun phrases rather than nouns /their beautiful new car was badly damaged when it was struck be a

falling tree/.

The

relationship which often obtains between a pronoun and its antecedent is not

one which can be explained by the simple act of replacement. In some

constructions we have repetition, which are by no means equivalent in meaning /Many students

did better than many students expected/. In some constructions repetition can be avoided by ellipsis /They hoped they would play a Mozart quartet and

they will/. Therefore the general term

pro-form is best applied to words and word sequences which are essentially

devices for rephrasing or anticipating the content of a neighboring expression,

often with the effect of grammatical complexity.

Such

devices are not limited to pronouns and participles: the word such can

described as a pro-form as there are pro-forms also for place, time and other

adverbials under certain circumstances /M.is

in London and J. is there too/.

In older English and still sometimes in very formal English we find thus and so

used as pro-forms for adverbials /He

often behaved silly, but he did not always behave thus/so/. But so has a more important function in

modern usage, namely to substitute with the ‘pro-verb’ do for a main

verb and whatever follows it in the clause /He

wished they would take him seriously for his ideas, but unfortunately

they didn’t do so/. Do can also

act as pro-form on its own /I told him

about it — I did too/.

Some

pro-forms can refer forward to what not been stated rather than back to what

has been stated. These are the wh-items. Indeed, wh-words,

including what, which, who and when, may be

regarded as a special set of pro-forms /Where is M.? — M. is in London. — J. is there too/. The paraphrase for wh-words is broad enough

to explain also their use in subordinate clauses /I wonder what M. thinks/. Through the use of wh-words we can ask for

the identification of subject, object, complement or adverbial of a sentence /They [S] make [V] him [O] the chairman [C] every year

[A]. — Who [S] makes him…?/.

Now that we have outlined the various aspects of Parts of Speech, according to

traditional grammars, we will look at some other approaches and other

specifications, without the sake of complexity, only to widen our views a

little more on the subject:

Otto Jespersen[5]starts out from the point that all clauses consist of

several words. One word is defined or modified by another word, which in turn

may be defined or modified by a third word. This leads to the establishment of

different ranks of words according to their mutual relations as defined or

defining. In the combination “extremely hot weather” weather may

be called a primary word or principal; hot

is a secondary word or

adjunct; and extremely is a

tertiary word or subjunct. Primary and secondary words are superior in relation to tertiary words; secondary and tertiary

words are inferior in relation to primary words. It is therefore

possible to have two or more (coordinate) adjuncts to the same principal /that

nice [A] young [A] lady [P]/.

The

logical basis of this system of subordination is the greater or lesser degree

of specialization. Primary words are more special (apply to a smaller number of individuals) than secondary

words, and these in their turn are less general than tertiary words. The word

defined by another word, is in itself always more special than the word

defining it, though the latter serves to render the former more special than it

is in itself. Thus in the sentence “very clever student”, student

is the most special idea, whereas clever can be applied to many more

men, and very, which indicates only a high degree, can be applied any

idea. Student is more special than clever, though clever

student is more special than student; clever is more special

than very, though very clever is more special than clever.

It

is a natural consequence of these definitions that proper nouns can only be

used as principals, and while there are thus some words that can only stand as

principals as expressing highly specialized ideas, there are other words that

may be either primary and secondary words in different combinations /conservative Liberals — liberal Conservatives/. Further there are words of such general signification

that they can never be used as primary words, like the articles.

His

further definitions of parts of speech fall under the categories of substantives (=principals), adjectives

(=adjuncts), adverbs (=subjuncts), verbs

(=verbs not subject to conjugation), verbids

(=participles and infinitives), predicatives (=‘mediate adjuncts’; {most commonly}a verb connecting two ideas in

such a way that the second becomes a kind of adjunct to the first (the

object)./Eg.: the rose is red/), objects (=primary words, but more special as well as more

general than the first principal /eg.: an owl sees a bird/.), and pronouns

(= a separate “parts of speech”, understood differently according to the

situation in which they are used).

Lyons[6]

starts out from distinguishing formal

and nominal definitions. Nominal definitions of the parts of

speech may be used to determine the names, though not the membership, of the

major syntactic classes of English. Creating syntactic classes on ‘formal’

distributional grounds, with all the members of each of them listed in the

lexicon, associated with the grammar, will mean that though not all members of

class X will denote persons, places and things; most of the lexical items which

refer to persons, places and things will fall within it; and if this is so we

may call X the class of nouns. In other words we have ‘formal’ class X and

‘notional’ class A; they are not co-extensive, but if A is wholly or mainly

included in X, then X may be given the label suggested by the ‘notional’ definition

of A.

He

also points out the necessity of considering the distinction between deep and

surface structure and define parts of speech not as classes of words in

surface structure, but as deep-structure constituents of sentences. The

distinction between deep and surface structures is not made explicitly in

traditional grammar, but it is implied by the assumption that all clauses and

phrases are derived from simple, modally ‘unmarked’ sentences. It is asserted

that every simple sentence is made up of two parts: a subject and a predicate. The subject is necessarily a noun (or a pronoun standing for a noun).

The predicate falls into one of three types according to the part of speech

which occurs in it: 1. intransitive verb, 2. transitive verb with its object,

3. the ‘verb to be’ with its complement. The object, like the

subject, must be a noun, while the complement must either be an adjective, or a

noun.

Deriving

from these associations with particular parts of speech it is possible to

determine traditional parts of speech or their function solely on the basis of

constituent-structure relations. The class of nouns is the one constituent

class which all sentences have in common at the highest level of constituent

structure. The class of intransitive verbs is the only class which combines

directly with nouns to form sentences. The class of transitive verbs combine

with nouns and with no other class to form predicates. Be is the

copula-class, since it combines with both nouns and the class of adjectives.

This argument rests of course on the specific assumptions incorporated in the

syntactic function of the parts of speech; namely the status of the copula or

‘verb to be’, and the universality of the distinction between verbs and

adjectives.

‘To

be’ is not itself a constituent of deep structure, but a semantically-empty

“dummy verb” generated for the specification of certain distinctions (usually

carried by the verb) when there is no other verbal element to carry these

distinctions. Sentences that are temporally, modally and aspectually unmarked

do not need the dummy carrier /M. is clever/. As for the distinction

between verbs and adjectives it is traditionally referred to as to do with the

surface phenomenon of inflection. The adjective, when it occurs in predicative

position, does not take the verbal suffixes associated with distinctions of

tense, mood and aspect, but instead a dummy verb is generated by the grammar to

carry the necessary inflexional suffixes /M. is clever — *M. is

clever-s/. The verb is less freely transformed

to the position of modifier in the noun-phrase; but when it occurs in this

syntactic position, unlike the adjective, it bears the suffix -ing /the clever man — the singing man — *the clever-ing man/. A distinction between stative verbs and verbs of action is also relevant to English. Stative verbs do not

normally occur in the progressive form, while the majority of English verbs,

which occur freely in the progressive are called verbs of action. This

aspectual difference is matched by a similar difference in English adjectives.

Most adjectives are stative, in the sense that they do not normally take

progressive aspect when they occur in predicative position /M. is clever — *M. is being clever/, but there are a number of adjectives which occur

freely with the progressive in the appropriate circumstances /M. is being silly now/. In other words, to be stative is normal for the

class of adjectives, but abnormal for the verbs; to be non-stative is normal

for verbs, but abnormal for adjectives. It is, however, the aspectual contrast

which correlates with the notional definition of the verb and the adjective in

terms of “action” and “quality”.

To follow this argument Huddleston[7]points

out that nothing said about inflection requires that all the forms of a lexeme

should belong to the same part of speech. The main problem area concerns the

traditional non-finite forms of verb lexemes, participles, the gerund and the

infinitive. A participle is said to be a “verbal adjective”, while the gerund

and the infinitive are “verbal nouns”. According to traditional doctrine, a

gerund like writing in She likes writing letters is a noun

because it is the object of the verb like. This would lead traditional

grammarians to classify together as nouns words which are syntactically very

different. /Eg.: Writing the

letters took some time — The writing of the letters took some time/. Instead of saying that both are nouns because they

are subject of took, he suggests that we call writing a verb in the

former case, because it is the head of the extended verb phrase, and call it a

noun in the latter case, because it is a head of the noun phrase. Since the

relation between this later type of noun writing and the stem write

is lexical rather than inflectional, he calls this a “deverbal noun”, for it is

derived by a lexical-morphological process from a verb stem.

The

second problem area concerns possessives. In the traditional treatment of forms

like John’s in John’s book is regarded as an inflectional form of

the noun John but is also said to have the force of an adjective. This

is easily resolved in the light of the analyses of ‘s as a clitic rather

than an inflexional suffix: John’s is not syntactically a single word,

not a form of John, so that the issue of whether a lexeme and a member

of its paradigm belong to the same parts of speech does not arise.

References

Huddleston,

R. —

Introduction to the grammar of English .

[ Cambridge University Press, 1984 ].

Jespersen,

O. —

Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles . (Vol. II.)

[ Allen and Unwin, 1954, London ].

Lyons — Introduction

to Theoretical Linguistics .

[ Cambridge University Press, 1968 ].

Mc

Cawley, J.D.

— The Syntactic Phenomena of English .

[ The University of Chicago Press, 1988 ].

Quirk

& Greenbaum

— A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language .

[Longman, 1983, London ].

Quirk

& Greenbaum

— A University Grammar of English .

[ Longman, 1973 ].

Quirk

& Greenbaum

— A Student’s Grammar of the English Language .

[ Longman, 1991 ].

Microsoft

(R) Encarta. 1994 Microsoft Corporation.

[ Funk & Wagnall’s Corp., 1994 ].

Just like a lot of words in the English language, this word has a double purpose. It can either be used as an adjective or as a pronoun.

- Adjective

This word is considered as an adjective when it is used to modify a noun. It can either indicate what particular one or it can also mean “whichever.” For example, in the sentence below:

I’m still deciding on which coat should I wear.

The word “which” is an adjective that modifies the noun “coat,” and is thus considered as an adjective.

Definition:

a. what one or ones of a group

- Example:

- She kept an organized record of which employees took their vacations.

b. whichever

- Example:

Turn it which way you like.

2. Pronoun

This word can also act as a pronoun when it is used to refer to something that has already been mentioned. It is commonly used at the beginning of the clause that provides further details about the noun. In the example below:

The crocodile which weighs over 2000 pounds was captured.

The word “which” is a pronoun that refers to the mentioned noun “crocodile.”

Definition:

a. used referring to something previously mentioned when introducing a clause giving further information

- Example:

- The computer which keeps breaking down was finally replaced with a new one.

In grammar, a part of speech or part-of-speech (abbreviated as POS or PoS, also known as word class[1] or grammatical category[2]) is a category of words (or, more generally, of lexical items) that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are assigned to the same part of speech generally display similar syntactic behavior (they play similar roles within the grammatical structure of sentences), sometimes similar morphological behavior in that they undergo inflection for similar properties and even similar semantic behavior. Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, and determiner.

Other terms than part of speech—particularly in modern linguistic classifications, which often make more precise distinctions than the traditional scheme does—include word class, lexical class, and lexical category. Some authors restrict the term lexical category to refer only to a particular type of syntactic category; for them the term excludes those parts of speech that are considered to be function words, such as pronouns. The term form class is also used, although this has various conflicting definitions.[3] Word classes may be classified as open or closed: open classes (typically including nouns, verbs and adjectives) acquire new members constantly, while closed classes (such as pronouns and conjunctions) acquire new members infrequently, if at all.

Almost all languages have the word classes noun and verb, but beyond these two there are significant variations among different languages.[4] For example:

- Japanese has as many as three classes of adjectives, where English has one.

- Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese have a class of nominal classifiers.

- Many languages do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, or between adjectives and verbs (see stative verb).

Because of such variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, analysis of parts of speech must be done for each individual language. Nevertheless, the labels for each category are assigned on the basis of universal criteria.[4]

History[edit]

The classification of words into lexical categories is found from the earliest moments in the history of linguistics.[5]

India[edit]

In the Nirukta, written in the 6th or 5th century BCE, the Sanskrit grammarian Yāska defined four main categories of words:[6]

- नाम nāma – noun (including adjective)

- आख्यात ākhyāta – verb

- उपसर्ग upasarga – pre-verb or prefix

- निपात nipāta – particle, invariant word (perhaps preposition)

These four were grouped into two larger classes: inflectable (nouns and verbs) and uninflectable (pre-verbs and particles).

The ancient work on the grammar of the Tamil language, Tolkāppiyam, argued to have been written around 2nd century CE,[7] classifies Tamil words as peyar (பெயர்; noun), vinai (வினை; verb), idai (part of speech which modifies the relationships between verbs and nouns), and uri (word that further qualifies a noun or verb).[8]

Western tradition[edit]

A century or two after the work of Yāska, the Greek scholar Plato wrote in his Cratylus dialogue, «sentences are, I conceive, a combination of verbs [rhêma] and nouns [ónoma]».[9] Aristotle added another class, «conjunction» [sýndesmos], which included not only the words known today as conjunctions, but also other parts (the interpretations differ; in one interpretation it is pronouns, prepositions, and the article).[10]

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, grammarians had expanded this classification scheme into eight categories, seen in the Art of Grammar, attributed to Dionysius Thrax:[11]

- ‘Name’ (ónoma) translated as «Noun«: a part of speech inflected for case, signifying a concrete or abstract entity. It includes various species like nouns, adjectives, proper nouns, appellatives, collectives, ordinals, numerals and more.[12]

- Verb (rhêma): a part of speech without case inflection, but inflected for tense, person and number, signifying an activity or process performed or undergone

- Participle (metokhḗ): a part of speech sharing features of the verb and the noun

- Article (árthron): a declinable part of speech, taken to include the definite article, but also the basic relative pronoun

- Pronoun (antōnymíā): a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person

- Preposition (próthesis): a part of speech placed before other words in composition and in syntax

- Adverb (epírrhēma): a part of speech without inflection, in modification of or in addition to a verb, adjective, clause, sentence, or other adverb

- Conjunction (sýndesmos): a part of speech binding together the discourse and filling gaps in its interpretation

It can be seen that these parts of speech are defined by morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria.

The Latin grammarian Priscian (fl. 500 CE) modified the above eightfold system, excluding «article» (since the Latin language, unlike Greek, does not have articles) but adding «interjection».[13][14]

The Latin names for the parts of speech, from which the corresponding modern English terms derive, were nomen, verbum, participium, pronomen, praepositio, adverbium, conjunctio and interjectio. The category nomen included substantives (nomen substantivum, corresponding to what are today called nouns in English), adjectives (nomen adjectivum) and numerals (nomen numerale). This is reflected in the older English terminology noun substantive, noun adjective and noun numeral. Later[15] the adjective became a separate class, as often did the numerals, and the English word noun came to be applied to substantives only.

Classification[edit]

Works of English grammar generally follow the pattern of the European tradition as described above, except that participles are now usually regarded as forms of verbs rather than as a separate part of speech, and numerals are often conflated with other parts of speech: nouns (cardinal numerals, e.g., «one», and collective numerals, e.g., «dozen»), adjectives (ordinal numerals, e.g., «first», and multiplier numerals, e.g., «single») and adverbs (multiplicative numerals, e.g., «once», and distributive numerals, e.g., «singly»). Eight or nine parts of speech are commonly listed:

- noun

- verb

- adjective

- adverb

- pronoun

- preposition

- conjunction

- interjection

- article* or (more recently) determiner

Additionally, there are other parts of speech including particles (yes, no)[a] and postpositions (ago, notwithstanding) although many fewer words are in these categories.

Some traditional classifications consider articles to be adjectives, yielding eight parts of speech rather than nine. And some modern classifications define further classes in addition to these. For discussion see the sections below.

The classification below, or slight expansions of it, is still followed in most dictionaries:

- Noun (names)

- a word or lexical item denoting any abstract (abstract noun: e.g. home) or concrete entity (concrete noun: e.g. house); a person (police officer, Michael), place (coastline, London), thing (necktie, television), idea (happiness), or quality (bravery). Nouns can also be classified as count nouns or non-count nouns; some can belong to either category. The most common part of speech; they are called naming words.

- Pronoun (replaces or places again)

- a substitute for a noun or noun phrase (them, he). Pronouns make sentences shorter and clearer since they replace nouns.

- Adjective (describes, limits)

- a modifier of a noun or pronoun (big, brave). Adjectives make the meaning of another word (noun) more precise.

- Verb (states action or being)

- a word denoting an action (walk), occurrence (happen), or state of being (be). Without a verb, a group of words cannot be a clause or sentence.

- Adverb (describes, limits)

- a modifier of an adjective, verb, or another adverb (very, quite). Adverbs make language more precise.

- Preposition (relates)

- a word that relates words to each other in a phrase or sentence and aids in syntactic context (in, of). Prepositions show the relationship between a noun or a pronoun with another word in the sentence.

- Conjunction (connects)

- a syntactic connector; links words, phrases, or clauses (and, but). Conjunctions connect words or group of words

- Interjection (expresses feelings and emotions)

- an emotional greeting or exclamation (Huzzah, Alas). Interjections express strong feelings and emotions.

- Article (describes, limits)

- a grammatical marker of definiteness (the) or indefiniteness (a, an). The article is not always listed among the parts of speech. It is considered by some grammarians to be a type of adjective[16] or sometimes the term ‘determiner’ (a broader class) is used.

English words are not generally marked as belonging to one part of speech or another; this contrasts with many other European languages, which use inflection more extensively, meaning that a given word form can often be identified as belonging to a particular part of speech and having certain additional grammatical properties. In English, most words are uninflected, while the inflected endings that exist are mostly ambiguous: -ed may mark a verbal past tense, a participle or a fully adjectival form; -s may mark a plural noun, a possessive noun, or a present-tense verb form; -ing may mark a participle, gerund, or pure adjective or noun. Although -ly is a frequent adverb marker, some adverbs (e.g. tomorrow, fast, very) do not have that ending, while many adjectives do have it (e.g. friendly, ugly, lovely), as do occasional words in other parts of speech (e.g. jelly, fly, rely).

Many English words can belong to more than one part of speech. Words like neigh, break, outlaw, laser, microwave, and telephone might all be either verbs or nouns. In certain circumstances, even words with primarily grammatical functions can be used as verbs or nouns, as in, «We must look to the hows and not just the whys.» The process whereby a word comes to be used as a different part of speech is called conversion or zero derivation.

Functional classification[edit]

Linguists recognize that the above list of eight or nine word classes is drastically simplified.[17] For example, «adverb» is to some extent a catch-all class that includes words with many different functions. Some have even argued that the most basic of category distinctions, that of nouns and verbs, is unfounded,[18] or not applicable to certain languages.[19][20] Modern linguists have proposed many different schemes whereby the words of English or other languages are placed into more specific categories and subcategories based on a more precise understanding of their grammatical functions.

Common lexical category set defined by function may include the following (not all of them will necessarily be applicable in a given language):

- Categories that will usually be open classes:

- adjectives

- adverbs

- nouns

- verbs (except auxiliary verbs)

- interjections

- Categories that will usually be closed classes:

- auxiliary verbs

- clitics

- coverbs

- conjunctions

- determiners (articles, quantifiers, demonstrative adjectives, and possessive adjectives)

- particles

- measure words or classifiers

- adpositions (prepositions, postpositions, and circumpositions)

- preverbs

- pronouns

- contractions

- cardinal numbers

Within a given category, subgroups of words may be identified based on more precise grammatical properties. For example, verbs may be specified according to the number and type of objects or other complements which they take. This is called subcategorization.

Many modern descriptions of grammar include not only lexical categories or word classes, but also phrasal categories, used to classify phrases, in the sense of groups of words that form units having specific grammatical functions. Phrasal categories may include noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP) and so on. Lexical and phrasal categories together are called syntactic categories.

Open and closed classes[edit]

Word classes may be either open or closed. An open class is one that commonly accepts the addition of new words, while a closed class is one to which new items are very rarely added. Open classes normally contain large numbers of words, while closed classes are much smaller. Typical open classes found in English and many other languages are nouns, verbs (excluding auxiliary verbs, if these are regarded as a separate class), adjectives, adverbs and interjections. Ideophones are often an open class, though less familiar to English speakers,[21][22][b] and are often open to nonce words. Typical closed classes are prepositions (or postpositions), determiners, conjunctions, and pronouns.[24]

The open–closed distinction is related to the distinction between lexical and functional categories, and to that between content words and function words, and some authors consider these identical, but the connection is not strict. Open classes are generally lexical categories in the stricter sense, containing words with greater semantic content,[25] while closed classes are normally functional categories, consisting of words that perform essentially grammatical functions. This is not universal: in many languages verbs and adjectives[26][27][28] are closed classes, usually consisting of few members, and in Japanese the formation of new pronouns from existing nouns is relatively common, though to what extent these form a distinct word class is debated.

Words are added to open classes through such processes as compounding, derivation, coining, and borrowing. When a new word is added through some such process, it can subsequently be used grammatically in sentences in the same ways as other words in its class.[29] A closed class may obtain new items through these same processes, but such changes are much rarer and take much more time. A closed class is normally seen as part of the core language and is not expected to change. In English, for example, new nouns, verbs, etc. are being added to the language constantly (including by the common process of verbing and other types of conversion, where an existing word comes to be used in a different part of speech). However, it is very unusual for a new pronoun, for example, to become accepted in the language, even in cases where there may be felt to be a need for one, as in the case of gender-neutral pronouns.

The open or closed status of word classes varies between languages, even assuming that corresponding word classes exist. Most conspicuously, in many languages verbs and adjectives form closed classes of content words. An extreme example is found in Jingulu, which has only three verbs, while even the modern Indo-European Persian has no more than a few hundred simple verbs, a great deal of which are archaic. (Some twenty Persian verbs are used as light verbs to form compounds; this lack of lexical verbs is shared with other Iranian languages.) Japanese is similar, having few lexical verbs.[30] Basque verbs are also a closed class, with the vast majority of verbal senses instead expressed periphrastically.

In Japanese, verbs and adjectives are closed classes,[31] though these are quite large, with about 700 adjectives,[32][33] and verbs have opened slightly in recent years. Japanese adjectives are closely related to verbs (they can predicate a sentence, for instance). New verbal meanings are nearly always expressed periphrastically by appending suru (する, to do) to a noun, as in undō suru (運動する, to (do) exercise), and new adjectival meanings are nearly always expressed by adjectival nouns, using the suffix -na (〜な) when an adjectival noun modifies a noun phrase, as in hen-na ojisan (変なおじさん, strange man). The closedness of verbs has weakened in recent years, and in a few cases new verbs are created by appending -ru (〜る) to a noun or using it to replace the end of a word. This is mostly in casual speech for borrowed words, with the most well-established example being sabo-ru (サボる, cut class; play hooky), from sabotāju (サボタージュ, sabotage).[34] This recent innovation aside, the huge contribution of Sino-Japanese vocabulary was almost entirely borrowed as nouns (often verbal nouns or adjectival nouns). Other languages where adjectives are closed class include Swahili,[28] Bemba, and Luganda.

By contrast, Japanese pronouns are an open class and nouns become used as pronouns with some frequency; a recent example is jibun (自分, self), now used by some young men as a first-person pronoun. The status of Japanese pronouns as a distinct class is disputed,[by whom?] however, with some considering it only a use of nouns, not a distinct class. The case is similar in languages of Southeast Asia, including Thai and Lao, in which, like Japanese, pronouns and terms of address vary significantly based on relative social standing and respect.[35]

Some word classes are universally closed, however, including demonstratives and interrogative words.[35]

See also[edit]

- Part-of-speech tagging

- Sliding window based part-of-speech tagging

Notes[edit]

- ^ Yes and no are sometimes classified as interjections.

- ^ Ideophones do not always form a single grammatical word class, and their classification varies between languages, sometimes being split across other word classes. Rather, they are a phonosemantic word class, based on derivation, but may be considered part of the category of «expressives»,[21] which thus often form an open class due to the productivity of ideophones. Further, «[i]n the vast majority of cases, however, ideophones perform an adverbial function and are closely linked with verbs.»[23]

References[edit]

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2007). «Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. Wiley. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00030.x. ISSN 1749-818X. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Payne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: a guide for field linguists. Cambridge. ISBN 9780511805066.

- ^ John Lyons, Semantics, CUP 1977, p. 424.

- ^ a b Kroeger, Paul (2005). Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-521-01653-7.

- ^ Robins RH (1989). General Linguistics (4th ed.). London: Longman.

- ^

Bimal Krishna Matilal (1990). The word and the world: India’s contribution to the study of language (Chapter 3). - ^ Mahadevan, I. (2014). Early Tamil Epigraphy — From the Earliest Times to the Sixth century C.E., 2nd Edition. p. 271.

- ^

Ilakkuvanar S (1994). Tholkappiyam in English with critical studies (2nd ed.). Educational Publisher. - ^ Cratylus 431b

- ^ The Rhetoric, Poetic and Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, translated by Thomas Taylor, London 1811, p. 179.

- ^ Dionysius Thrax. τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), ια´ περὶ λέξεως (11. On the word):

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

λόγος δέ ἐστι πεζῆς λέξεως σύνθεσις διάνοιαν αὐτοτελῆ δηλοῦσα.

τοῦ δὲ λόγου μέρη ἐστὶν ὀκτώ· ὄνομα, ῥῆμα,

μετοχή, ἄρθρον, ἀντωνυμία, πρόθεσις, ἐπίρρημα, σύνδεσμος. ἡ γὰρ προσηγορία ὡς εἶδος τῶι ὀνόματι ὑποβέβληται. - A word is the smallest part of organized speech.

Speech is the putting together of an ordinary word to express a complete thought.

The class of word consists of eight categories: noun, verb,

participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction. A common noun in form is classified as a noun.

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

- ^ The term ‘onoma’ at Dionysius Thrax, Τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), 14. Περὶ ὀνόματος translated by Thomas Davidson, On the noun

- καὶ αὐτὰ εἴδη προσαγορεύεται· κύριον, προσηγορικόν, ἐπίθετον, πρός τι ἔχον, ὡς πρός τι ἔχον, ὁμώνυμον, συνώνυμον, διώνυμον, ἐπώνυμον, ἐθνικόν, ἐρωτηματικόν, ἀόριστον, ἀναφορικὸν ὃ καὶ ὁμοιωματικὸν καὶ δεικτικὸν καὶ ἀνταποδοτικὸν καλεῖται, περιληπτικόν, ἐπιμεριζόμενον, περιεκτικόν, πεποιημένον, γενικόν, ἰδικόν, τακτικόν, ἀριθμητικόν, ἀπολελυμένον, μετουσιαστικόν.

- also called Species: proper, appellative, adjective, relative, quasi-relative, homonym, synonym, pheronym, dionym, eponym, national, interrogative, indefinite, anaphoric (also called assimilative, demonstrative, and retributive), collective, distributive, inclusive, onomatopoetic, general, special, ordinal, numeral, participative, independent.

- ^ [penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Quintilian/Institutio_Oratoria/1B*.html This translation of Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria reads: «Our own language (Note: i.e. Latin) dispenses with the articles (Note: Latin doesn’t have articles), which are therefore distributed among the other parts of speech. But interjections must be added to those already mentioned.»]

- ^ «Quintilian: Institutio Oratoria I».

- ^ See for example Beauzée, Nicolas, Grammaire générale, ou exposition raisonnée des éléments nécessaires du langage (Paris, 1767), and earlier Jakob Redinger, Comeniana Grammatica Primae Classi Franckenthalensis Latinae Scholae destinata … (1659, in German and Latin).

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar by Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker & Edmund Weine. OUP Oxford 2014. Page 35.

- ^ Zwicky, Arnold (30 March 2006). «What part of speech is «the»«. Language Log. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

…the school tradition about parts of speech is so desperately impoverished

- ^ Hopper, P; Thompson, S (1985). «The Iconicity of the Universal Categories ‘Noun’ and ‘Verbs’«. In John Haiman (ed.). Typological Studies in Language: Iconicity and Syntax. Vol. 6. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 151–183.

- ^ Launey, Michel (1994). Une grammaire omniprédicative: essai sur la morphosyntaxe du nahuatl classique. Paris: CNRS Editions.