It is a fact that almost every word of English has got the capacity to be employed as a different part of speech. At one place, a particular word may be used as a noun, at another as a verb, and yet at another place as an adjective.

These words enable the learners of the English language to understand the behavior of a particular word in various positions.

Importance of Parts of Speech in Communication

As you know, English sentences are used to communicate a complete thought. The importance of parts of speech lies in their proper utilization, which can help your understanding and confidence grow immensely.

Proper usage of parts of speech means that you can impart clear messages and understand them because you know the rules of the language.

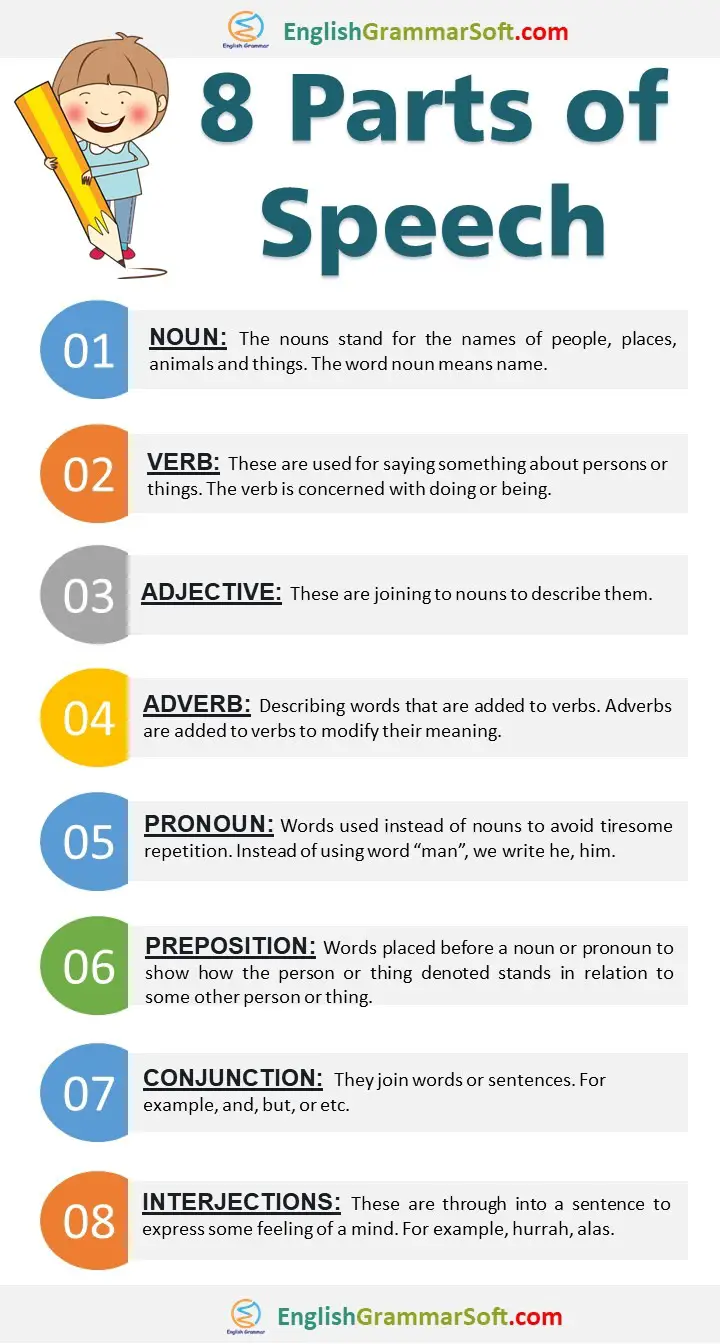

Each word in a sentence belongs to one of the eight parts of speech according to the work it is doing in that sentence. There are 8 parts of speech.

- Noun

- Verb

- Adjective

- Adverb

- Pronoun

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

1 – Noun (Naming words)

The nouns stand for the names of people, places, animals, and things. The word noun means name. Look at these sentences.

“John lives in Chicago. He has two bikes. He is fond of riding bikes.”

In the above example, John is the name. We cannot use the same name again and again in different sentences. Here, we used “he” in the next two sentences instead of “John”. “He” is called the pronoun.

Types of nouns are

1.1 – Common Noun

It describes a person, place, and thing.

Examples: City, country, town, boy.

1.2 – Proper Noun

It includes a particular person, place, thing, or idea and begins with a capital letter.

Examples: Austria, Manchester, United Kingdom, etc.

1.3 – Abstract Noun

An abstract noun describes names, ideas, feelings, emotions or qualities, the subject of any paragraph comes under this category. It does not take “the”.

Examples: grief, loss, happiness, greatness.

1.4 – Concrete Noun

It describes material things, persons or places. The existence of that thing can be physically observed.

Examples: Book, table, car, etc.

1.5 – Countable and Uncountable Noun

Countable nouns can be singular or plural. It can be counted.

Examples: Ships, cars, buses, books, etc.

The uncountable noun is neither singular nor plural. It cannot be counted.

Examples: Water, milk, juice, butter, music, etc.

1.6 – Collective Noun

It includes the group and collection

people, things or ideas. It is in unit form and is considered as singular.

Examples: Staff of office, group of visitors.

However, people and police can be

considered both singular and plural.

1.7 – Possessive Noun

It shows ownership or relationship.

Examples: Jimmy’s pen.

Further Reading: 11 Types of Nouns with Examples

2 – Verb (Saying words)

These are used for saying something

about persons or things. The verb is concerned with doing or being.

Examples

- A hare runs (action) very fast.

- Aslam is a good student.

Types of verbs

2.1 – Actions verbs

(run, move, write etc)

2.2 – Linking verbs

(to be (is, am, are, was, were), seem, feel, look, understand)

2.3 – Auxiliary (helping) verbs

(have, do, be)

2.4 – Modal Verbs

(can, could, may, might, will/shall)

2.5 – Transitive verbs

It takes an object.

Example – He is reading a newspaper.

2.6 – Intransitive verbs

It does not take the object.

Example – He awakes.

Further Reading: What are the verbs in English?

3 – Adjectives (describing words)

These are joining to nouns to describe

them.

Examples

- A hungry wolf.

- A brown wolf.

- A lazy boy.

- A tall man.

It is used before a noun and after a linking verb.

Before noun example

A new brand has been launched.

After linking verb example

Imran is rich.

It is used to clarify nouns.

Example: smart boy, blind man

Types of adjectives

3.1 – Simple degree

He is intelligent.

3.2 – Comparative

Ali is intelligent than Imran.

3.3 – Superlative

Comparison of one person with class,

country or world. In this type “the” is used.

Example: Ali is the wisest boy.

3.4 – Demonstrative adjective

It points out a noun. These are four

in number.

This That These Those

3.5 – Indefinite adjectives

It points out nouns. They often tell

“how many” or “how much” of something.

Interrogative adjectives: it is used to ask questions

Examples

- Which book?

- What time?

- Whose car?

Further Reading: More About Adjectives

4 – Adverbs

Describing words that are added to verbs. Just as adjectives are added to describe them, adverbs are added to verbs to modify their meaning. The word “modify” means to enlarge the meaning of the adverbs.

Examples

- Emma sings beautifully. (used with verb)

- Cameron is extremely clever. (used with adjective)

- This motor car goes incredibly fast. (used with another adverb)

Types of adverb

4.1 – Adverb of manner

This type of adverb deals with the

action something

Example

- I walk quickly.

- He wrote slowly.

4.2 – Adverb of place

Happening of something or the place where it happens.

Examples:

There was somebody sitting nearby.

Here, these, upstairs, nowhere everywhere, outside, in, out, are called adverb of place.

4.3 – Adverb of time

It determines the time of the happening of something.

Examples

- She went there last night.

- Have you seen him before?

- He wrote a letter yesterday.

Tomorrow, today, now, then,

yesterday, already, ago.

4.4 – Linking adverbs (then, however)

It creates a connection between two clauses or sentences.

Example

There will be clouds in Lahore. However, the sun is expected in Multan.

Note: Besides modifying the meaning of a verb, adverbs also modify adjectives and other adverbs.

Examples

- It is a very large house.

- He is too weak to walk.

- He ran too fast.

Further Reading: 11 Types of Adverbs with Examples

5 – Pronouns

Words that are used instead of nouns to avoid tiresome repetition. Instead of using the word man in a composition, we often write he, him, himself. In place of the word “woman”, we write she, her, or herself. For both the nouns ‘men’ and ‘women’ we use, they, them, themselves.

Some of the most common pronouns are

Singular: I, he, she, it, me, him,

her

Plural: We, they, out, us, them.

Examples

Imran was hurt. He didn’t panic.

He checked the mobile. It still

worked.

Types of Pronouns

It stands instead of persons. They have different forms according to the person who is supposed to be speaking.

First person: I, we, me, us, mine, our, ourselves.

Second person: thou, you, there.

Third person: He, she, it, his, him

5.1 – Possessive pronouns

Such as mine, ours, yours, hers and theirs.

- This book is mine.

- My horse and yours are tired.

5.2 – Relative pronoun

Who, whom, which and they are called relative pronouns. They are called relative because they relate to some word in the main clause. The word to which pronoun relates is called the antecedent.

Example

I saw a boy who was going.

In this sentence, who is the relative pronoun and boy is its antecedent.

This is the girl who won the prize.

“which” is used for animals and things.

The dog which barks.

That is used instead of who or which in this case.

This is the best picture that I ever saw.

5.3 – Interrogative pronouns

It is used to introduce or create an asking position in a sentence. Who, whom, which, and whose are interrogative pronouns.

Examples

Who wrote this book? (for persons

only)

What is your name? (for things)

Which boy here is your friend?

5.4 – Demonstrative pronoun

It points out a person, thing, place

or idea. This, that, these and those are called demonstrative pronouns.

That is a circuit-breaker.

These are cups of a team.

5.5 – Reflexive pronoun

The type of pronoun that ends in self or selves is called a reflexive pronoun.

Examples: myself, ourselves, yourself, herself, himself, itself, themselves.

Use in sentence: They worked hard to

get out themselves from the debt.

Indefinite pronoun: An indefinite

pronoun does not refer to a specific person, place thing or idea.

Examples

Nothing lasts forever.

No one can make this design.

Further Reading: Different Types of Pronouns with 60+ Examples

6 – Prepositions

Words placed before a noun or pronoun

to show how the person or thing denoted stands in relation to some other person

or thing.

Examples: A house on a hill. Here, the word “on” is a preposition.

The noun and pronoun that follow the preposition are called its object. We can identify prepositions in the following examples.

In 2006, in March, in the garden,

On 14th August, on Friday, on the table

At 8:30 pm, at 9 o’clock, at the door, at noon, at night, at midnight

However, we use “in” for morning and evening.

Further Reading: Preposition Usage and Examples

7 – Conjunctions (joining words)

They join words or sentences.

Examples: Jimmy and Tom are good players.

In the above sentence, “and” is a conjunction.

Types of conjunctions

These are the types of conjunctions.

- Nor (used in later part of the negative sentence)

- But (when two different ideas are described in a sentence)

- Yet (when two contrast things are being described in a sentence)

- So (To explain the reason)

- For (it connects a reason to a result)

- Or (to adopt two equal choices)

- And (to join two things or work)

Further Reading: Conjunction Rules with Examples

8 – Interjections

Interjection words are not connected with other parts of a sentence. They are through into a sentence to express some feeling of a mind.

Examples: Hurrah! We won the match.

Alas, hurrah, wow, uh, oh-no, gush, shh are some words used to express the feeling.

It is important to note that placing a word in this or that part of speech is not fixed. It depends upon the work the words are doing in a particular sentence. Thus the same word may appear in three or four parts of speech.

Further Reading: More about Interjections

You can read a detailed article about parts of speech here.

Parts of Speech Exercise with Answers

Read also: 71 Idioms with Meaning and Sentences

Just like a lot of words in the English language, this word has a double purpose. It can either be used as an adjective or as a pronoun.

- Adjective

This word is considered as an adjective when it is used to modify a noun. It can either indicate what particular one or it can also mean “whichever.” For example, in the sentence below:

I’m still deciding on which coat should I wear.

The word “which” is an adjective that modifies the noun “coat,” and is thus considered as an adjective.

Definition:

a. what one or ones of a group

- Example:

- She kept an organized record of which employees took their vacations.

b. whichever

- Example:

Turn it which way you like.

2. Pronoun

This word can also act as a pronoun when it is used to refer to something that has already been mentioned. It is commonly used at the beginning of the clause that provides further details about the noun. In the example below:

The crocodile which weighs over 2000 pounds was captured.

The word “which” is a pronoun that refers to the mentioned noun “crocodile.”

Definition:

a. used referring to something previously mentioned when introducing a clause giving further information

- Example:

- The computer which keeps breaking down was finally replaced with a new one.

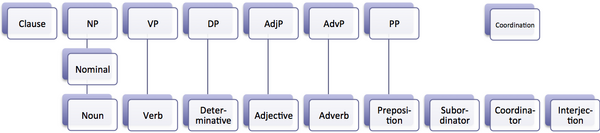

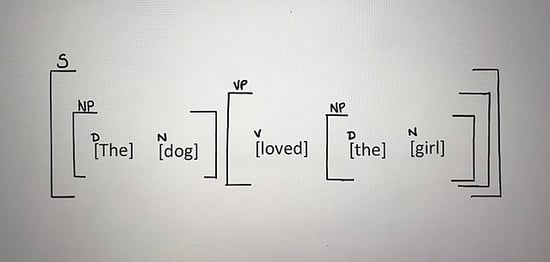

In grammar, a part of speech or part-of-speech (abbreviated as POS or PoS, also known as word class[1] or grammatical category[2]) is a category of words (or, more generally, of lexical items) that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are assigned to the same part of speech generally display similar syntactic behavior (they play similar roles within the grammatical structure of sentences), sometimes similar morphological behavior in that they undergo inflection for similar properties and even similar semantic behavior. Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, and determiner.

Other terms than part of speech—particularly in modern linguistic classifications, which often make more precise distinctions than the traditional scheme does—include word class, lexical class, and lexical category. Some authors restrict the term lexical category to refer only to a particular type of syntactic category; for them the term excludes those parts of speech that are considered to be function words, such as pronouns. The term form class is also used, although this has various conflicting definitions.[3] Word classes may be classified as open or closed: open classes (typically including nouns, verbs and adjectives) acquire new members constantly, while closed classes (such as pronouns and conjunctions) acquire new members infrequently, if at all.

Almost all languages have the word classes noun and verb, but beyond these two there are significant variations among different languages.[4] For example:

- Japanese has as many as three classes of adjectives, where English has one.

- Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese have a class of nominal classifiers.

- Many languages do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, or between adjectives and verbs (see stative verb).

Because of such variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, analysis of parts of speech must be done for each individual language. Nevertheless, the labels for each category are assigned on the basis of universal criteria.[4]

History[edit]

The classification of words into lexical categories is found from the earliest moments in the history of linguistics.[5]

India[edit]

In the Nirukta, written in the 6th or 5th century BCE, the Sanskrit grammarian Yāska defined four main categories of words:[6]

- नाम nāma – noun (including adjective)

- आख्यात ākhyāta – verb

- उपसर्ग upasarga – pre-verb or prefix

- निपात nipāta – particle, invariant word (perhaps preposition)

These four were grouped into two larger classes: inflectable (nouns and verbs) and uninflectable (pre-verbs and particles).

The ancient work on the grammar of the Tamil language, Tolkāppiyam, argued to have been written around 2nd century CE,[7] classifies Tamil words as peyar (பெயர்; noun), vinai (வினை; verb), idai (part of speech which modifies the relationships between verbs and nouns), and uri (word that further qualifies a noun or verb).[8]

Western tradition[edit]

A century or two after the work of Yāska, the Greek scholar Plato wrote in his Cratylus dialogue, «sentences are, I conceive, a combination of verbs [rhêma] and nouns [ónoma]».[9] Aristotle added another class, «conjunction» [sýndesmos], which included not only the words known today as conjunctions, but also other parts (the interpretations differ; in one interpretation it is pronouns, prepositions, and the article).[10]

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, grammarians had expanded this classification scheme into eight categories, seen in the Art of Grammar, attributed to Dionysius Thrax:[11]

- ‘Name’ (ónoma) translated as «Noun«: a part of speech inflected for case, signifying a concrete or abstract entity. It includes various species like nouns, adjectives, proper nouns, appellatives, collectives, ordinals, numerals and more.[12]

- Verb (rhêma): a part of speech without case inflection, but inflected for tense, person and number, signifying an activity or process performed or undergone

- Participle (metokhḗ): a part of speech sharing features of the verb and the noun

- Article (árthron): a declinable part of speech, taken to include the definite article, but also the basic relative pronoun

- Pronoun (antōnymíā): a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person

- Preposition (próthesis): a part of speech placed before other words in composition and in syntax

- Adverb (epírrhēma): a part of speech without inflection, in modification of or in addition to a verb, adjective, clause, sentence, or other adverb

- Conjunction (sýndesmos): a part of speech binding together the discourse and filling gaps in its interpretation

It can be seen that these parts of speech are defined by morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria.

The Latin grammarian Priscian (fl. 500 CE) modified the above eightfold system, excluding «article» (since the Latin language, unlike Greek, does not have articles) but adding «interjection».[13][14]

The Latin names for the parts of speech, from which the corresponding modern English terms derive, were nomen, verbum, participium, pronomen, praepositio, adverbium, conjunctio and interjectio. The category nomen included substantives (nomen substantivum, corresponding to what are today called nouns in English), adjectives (nomen adjectivum) and numerals (nomen numerale). This is reflected in the older English terminology noun substantive, noun adjective and noun numeral. Later[15] the adjective became a separate class, as often did the numerals, and the English word noun came to be applied to substantives only.

Classification[edit]

Works of English grammar generally follow the pattern of the European tradition as described above, except that participles are now usually regarded as forms of verbs rather than as a separate part of speech, and numerals are often conflated with other parts of speech: nouns (cardinal numerals, e.g., «one», and collective numerals, e.g., «dozen»), adjectives (ordinal numerals, e.g., «first», and multiplier numerals, e.g., «single») and adverbs (multiplicative numerals, e.g., «once», and distributive numerals, e.g., «singly»). Eight or nine parts of speech are commonly listed:

- noun

- verb

- adjective

- adverb

- pronoun

- preposition

- conjunction

- interjection

- article* or (more recently) determiner

Additionally, there are other parts of speech including particles (yes, no)[a] and postpositions (ago, notwithstanding) although many fewer words are in these categories.

Some traditional classifications consider articles to be adjectives, yielding eight parts of speech rather than nine. And some modern classifications define further classes in addition to these. For discussion see the sections below.

The classification below, or slight expansions of it, is still followed in most dictionaries:

- Noun (names)

- a word or lexical item denoting any abstract (abstract noun: e.g. home) or concrete entity (concrete noun: e.g. house); a person (police officer, Michael), place (coastline, London), thing (necktie, television), idea (happiness), or quality (bravery). Nouns can also be classified as count nouns or non-count nouns; some can belong to either category. The most common part of speech; they are called naming words.

- Pronoun (replaces or places again)

- a substitute for a noun or noun phrase (them, he). Pronouns make sentences shorter and clearer since they replace nouns.

- Adjective (describes, limits)

- a modifier of a noun or pronoun (big, brave). Adjectives make the meaning of another word (noun) more precise.

- Verb (states action or being)

- a word denoting an action (walk), occurrence (happen), or state of being (be). Without a verb, a group of words cannot be a clause or sentence.

- Adverb (describes, limits)

- a modifier of an adjective, verb, or another adverb (very, quite). Adverbs make language more precise.

- Preposition (relates)

- a word that relates words to each other in a phrase or sentence and aids in syntactic context (in, of). Prepositions show the relationship between a noun or a pronoun with another word in the sentence.

- Conjunction (connects)

- a syntactic connector; links words, phrases, or clauses (and, but). Conjunctions connect words or group of words

- Interjection (expresses feelings and emotions)

- an emotional greeting or exclamation (Huzzah, Alas). Interjections express strong feelings and emotions.

- Article (describes, limits)

- a grammatical marker of definiteness (the) or indefiniteness (a, an). The article is not always listed among the parts of speech. It is considered by some grammarians to be a type of adjective[16] or sometimes the term ‘determiner’ (a broader class) is used.

English words are not generally marked as belonging to one part of speech or another; this contrasts with many other European languages, which use inflection more extensively, meaning that a given word form can often be identified as belonging to a particular part of speech and having certain additional grammatical properties. In English, most words are uninflected, while the inflected endings that exist are mostly ambiguous: -ed may mark a verbal past tense, a participle or a fully adjectival form; -s may mark a plural noun, a possessive noun, or a present-tense verb form; -ing may mark a participle, gerund, or pure adjective or noun. Although -ly is a frequent adverb marker, some adverbs (e.g. tomorrow, fast, very) do not have that ending, while many adjectives do have it (e.g. friendly, ugly, lovely), as do occasional words in other parts of speech (e.g. jelly, fly, rely).

Many English words can belong to more than one part of speech. Words like neigh, break, outlaw, laser, microwave, and telephone might all be either verbs or nouns. In certain circumstances, even words with primarily grammatical functions can be used as verbs or nouns, as in, «We must look to the hows and not just the whys.» The process whereby a word comes to be used as a different part of speech is called conversion or zero derivation.

Functional classification[edit]

Linguists recognize that the above list of eight or nine word classes is drastically simplified.[17] For example, «adverb» is to some extent a catch-all class that includes words with many different functions. Some have even argued that the most basic of category distinctions, that of nouns and verbs, is unfounded,[18] or not applicable to certain languages.[19][20] Modern linguists have proposed many different schemes whereby the words of English or other languages are placed into more specific categories and subcategories based on a more precise understanding of their grammatical functions.

Common lexical category set defined by function may include the following (not all of them will necessarily be applicable in a given language):

- Categories that will usually be open classes:

- adjectives

- adverbs

- nouns

- verbs (except auxiliary verbs)

- interjections

- Categories that will usually be closed classes:

- auxiliary verbs

- clitics

- coverbs

- conjunctions

- determiners (articles, quantifiers, demonstrative adjectives, and possessive adjectives)

- particles

- measure words or classifiers

- adpositions (prepositions, postpositions, and circumpositions)

- preverbs

- pronouns

- contractions

- cardinal numbers

Within a given category, subgroups of words may be identified based on more precise grammatical properties. For example, verbs may be specified according to the number and type of objects or other complements which they take. This is called subcategorization.

Many modern descriptions of grammar include not only lexical categories or word classes, but also phrasal categories, used to classify phrases, in the sense of groups of words that form units having specific grammatical functions. Phrasal categories may include noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP) and so on. Lexical and phrasal categories together are called syntactic categories.

Open and closed classes[edit]

Word classes may be either open or closed. An open class is one that commonly accepts the addition of new words, while a closed class is one to which new items are very rarely added. Open classes normally contain large numbers of words, while closed classes are much smaller. Typical open classes found in English and many other languages are nouns, verbs (excluding auxiliary verbs, if these are regarded as a separate class), adjectives, adverbs and interjections. Ideophones are often an open class, though less familiar to English speakers,[21][22][b] and are often open to nonce words. Typical closed classes are prepositions (or postpositions), determiners, conjunctions, and pronouns.[24]

The open–closed distinction is related to the distinction between lexical and functional categories, and to that between content words and function words, and some authors consider these identical, but the connection is not strict. Open classes are generally lexical categories in the stricter sense, containing words with greater semantic content,[25] while closed classes are normally functional categories, consisting of words that perform essentially grammatical functions. This is not universal: in many languages verbs and adjectives[26][27][28] are closed classes, usually consisting of few members, and in Japanese the formation of new pronouns from existing nouns is relatively common, though to what extent these form a distinct word class is debated.

Words are added to open classes through such processes as compounding, derivation, coining, and borrowing. When a new word is added through some such process, it can subsequently be used grammatically in sentences in the same ways as other words in its class.[29] A closed class may obtain new items through these same processes, but such changes are much rarer and take much more time. A closed class is normally seen as part of the core language and is not expected to change. In English, for example, new nouns, verbs, etc. are being added to the language constantly (including by the common process of verbing and other types of conversion, where an existing word comes to be used in a different part of speech). However, it is very unusual for a new pronoun, for example, to become accepted in the language, even in cases where there may be felt to be a need for one, as in the case of gender-neutral pronouns.

The open or closed status of word classes varies between languages, even assuming that corresponding word classes exist. Most conspicuously, in many languages verbs and adjectives form closed classes of content words. An extreme example is found in Jingulu, which has only three verbs, while even the modern Indo-European Persian has no more than a few hundred simple verbs, a great deal of which are archaic. (Some twenty Persian verbs are used as light verbs to form compounds; this lack of lexical verbs is shared with other Iranian languages.) Japanese is similar, having few lexical verbs.[30] Basque verbs are also a closed class, with the vast majority of verbal senses instead expressed periphrastically.

In Japanese, verbs and adjectives are closed classes,[31] though these are quite large, with about 700 adjectives,[32][33] and verbs have opened slightly in recent years. Japanese adjectives are closely related to verbs (they can predicate a sentence, for instance). New verbal meanings are nearly always expressed periphrastically by appending suru (する, to do) to a noun, as in undō suru (運動する, to (do) exercise), and new adjectival meanings are nearly always expressed by adjectival nouns, using the suffix -na (〜な) when an adjectival noun modifies a noun phrase, as in hen-na ojisan (変なおじさん, strange man). The closedness of verbs has weakened in recent years, and in a few cases new verbs are created by appending -ru (〜る) to a noun or using it to replace the end of a word. This is mostly in casual speech for borrowed words, with the most well-established example being sabo-ru (サボる, cut class; play hooky), from sabotāju (サボタージュ, sabotage).[34] This recent innovation aside, the huge contribution of Sino-Japanese vocabulary was almost entirely borrowed as nouns (often verbal nouns or adjectival nouns). Other languages where adjectives are closed class include Swahili,[28] Bemba, and Luganda.

By contrast, Japanese pronouns are an open class and nouns become used as pronouns with some frequency; a recent example is jibun (自分, self), now used by some young men as a first-person pronoun. The status of Japanese pronouns as a distinct class is disputed,[by whom?] however, with some considering it only a use of nouns, not a distinct class. The case is similar in languages of Southeast Asia, including Thai and Lao, in which, like Japanese, pronouns and terms of address vary significantly based on relative social standing and respect.[35]

Some word classes are universally closed, however, including demonstratives and interrogative words.[35]

See also[edit]

- Part-of-speech tagging

- Sliding window based part-of-speech tagging

Notes[edit]

- ^ Yes and no are sometimes classified as interjections.

- ^ Ideophones do not always form a single grammatical word class, and their classification varies between languages, sometimes being split across other word classes. Rather, they are a phonosemantic word class, based on derivation, but may be considered part of the category of «expressives»,[21] which thus often form an open class due to the productivity of ideophones. Further, «[i]n the vast majority of cases, however, ideophones perform an adverbial function and are closely linked with verbs.»[23]

References[edit]

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2007). «Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. Wiley. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00030.x. ISSN 1749-818X. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Payne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: a guide for field linguists. Cambridge. ISBN 9780511805066.

- ^ John Lyons, Semantics, CUP 1977, p. 424.

- ^ a b Kroeger, Paul (2005). Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-521-01653-7.

- ^ Robins RH (1989). General Linguistics (4th ed.). London: Longman.

- ^

Bimal Krishna Matilal (1990). The word and the world: India’s contribution to the study of language (Chapter 3). - ^ Mahadevan, I. (2014). Early Tamil Epigraphy — From the Earliest Times to the Sixth century C.E., 2nd Edition. p. 271.

- ^

Ilakkuvanar S (1994). Tholkappiyam in English with critical studies (2nd ed.). Educational Publisher. - ^ Cratylus 431b

- ^ The Rhetoric, Poetic and Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, translated by Thomas Taylor, London 1811, p. 179.

- ^ Dionysius Thrax. τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), ια´ περὶ λέξεως (11. On the word):

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

λόγος δέ ἐστι πεζῆς λέξεως σύνθεσις διάνοιαν αὐτοτελῆ δηλοῦσα.

τοῦ δὲ λόγου μέρη ἐστὶν ὀκτώ· ὄνομα, ῥῆμα,

μετοχή, ἄρθρον, ἀντωνυμία, πρόθεσις, ἐπίρρημα, σύνδεσμος. ἡ γὰρ προσηγορία ὡς εἶδος τῶι ὀνόματι ὑποβέβληται. - A word is the smallest part of organized speech.

Speech is the putting together of an ordinary word to express a complete thought.

The class of word consists of eight categories: noun, verb,

participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction. A common noun in form is classified as a noun.

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

- ^ The term ‘onoma’ at Dionysius Thrax, Τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), 14. Περὶ ὀνόματος translated by Thomas Davidson, On the noun

- καὶ αὐτὰ εἴδη προσαγορεύεται· κύριον, προσηγορικόν, ἐπίθετον, πρός τι ἔχον, ὡς πρός τι ἔχον, ὁμώνυμον, συνώνυμον, διώνυμον, ἐπώνυμον, ἐθνικόν, ἐρωτηματικόν, ἀόριστον, ἀναφορικὸν ὃ καὶ ὁμοιωματικὸν καὶ δεικτικὸν καὶ ἀνταποδοτικὸν καλεῖται, περιληπτικόν, ἐπιμεριζόμενον, περιεκτικόν, πεποιημένον, γενικόν, ἰδικόν, τακτικόν, ἀριθμητικόν, ἀπολελυμένον, μετουσιαστικόν.

- also called Species: proper, appellative, adjective, relative, quasi-relative, homonym, synonym, pheronym, dionym, eponym, national, interrogative, indefinite, anaphoric (also called assimilative, demonstrative, and retributive), collective, distributive, inclusive, onomatopoetic, general, special, ordinal, numeral, participative, independent.

- ^ [penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Quintilian/Institutio_Oratoria/1B*.html This translation of Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria reads: «Our own language (Note: i.e. Latin) dispenses with the articles (Note: Latin doesn’t have articles), which are therefore distributed among the other parts of speech. But interjections must be added to those already mentioned.»]

- ^ «Quintilian: Institutio Oratoria I».

- ^ See for example Beauzée, Nicolas, Grammaire générale, ou exposition raisonnée des éléments nécessaires du langage (Paris, 1767), and earlier Jakob Redinger, Comeniana Grammatica Primae Classi Franckenthalensis Latinae Scholae destinata … (1659, in German and Latin).

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar by Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker & Edmund Weine. OUP Oxford 2014. Page 35.

- ^ Zwicky, Arnold (30 March 2006). «What part of speech is «the»«. Language Log. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

…the school tradition about parts of speech is so desperately impoverished

- ^ Hopper, P; Thompson, S (1985). «The Iconicity of the Universal Categories ‘Noun’ and ‘Verbs’«. In John Haiman (ed.). Typological Studies in Language: Iconicity and Syntax. Vol. 6. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 151–183.

- ^ Launey, Michel (1994). Une grammaire omniprédicative: essai sur la morphosyntaxe du nahuatl classique. Paris: CNRS Editions.

- ^ Broschart, Jürgen (1997). «Why Tongan does it differently: Categorial Distinctions in a Language without Nouns and Verbs». Linguistic Typology. 1 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1515/lity.1997.1.2.123. S2CID 121039930.

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 99

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 179

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 181

- ^ «Sample Entry: Function Words / Encyclopedia of Linguistics».

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-470-65531-3.

- ^ Dixon, Robert M. W. (1977). «Where Have all the Adjectives Gone?». Studies in Language. 1: 19–80. doi:10.1075/sl.1.1.04dix.

- ^ Adjective classes: a cross-linguistic typology, Robert M. W. Dixon, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, OUP Oxford, 2006

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 97

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2014). Language Development. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-133-93909-2.

- ^ Categorial Features: A Generative Theory of Word Class Categories, «p. 54».

- ^ Dixon 1977, p. 48.

- ^ The Typology of Adjectival Predication, Harrie Wetzer, p. 311

- ^ The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 96

- ^ Adam (2011-07-18). «Homage to る(ru), The Magical Verbifier».

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 98

External links[edit]

Media related to Parts of speech at Wikimedia Commons

- The parts of speech

- Guide to Grammar and Writing

- Martin Haspelmath. 2001. «Word Classes and Parts of Speech.» In: Baltes, Paul B. & Smelser, Neil J. (eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Pergamon, 16538–16545. (PDF)

Parts of Speech. Principles of Classification of the Parts of Speech.

√ Parts of speech.

√ Semantic.

√ Morphological.

√ Syntactic.

√ Meaning.

√ Form.

√ Function

√ Meaning

Parts of speech

Parts of speech are grammatical classes of words which are distinguished on the basis of four criteria:

— semantic;

— morphological;

— syntactic;

that of valency (combinability)

1) Meaning. Each part of speech is characterized by the general meaning which is an abstraction from the lexical meaning of the constituent word. Thus, the general meaning of nouns is thingness (substance), the general meaning of verbs is action, state, process; the general meaning of adjectives — quality, quantity.

The general meaning is understood as categorial meaning of the class of words.

Semantic properties of every part of speech find their expression in their grammatical properties. If we take «to sleep, a night sleep, sleepy, asleep» they all refer to the same phenomena of the objective reality but belong to different parts of speech as they have different grammatical properties.

Meaning is supportive criterion in the English language which only helps to check purely grammatical criteria — those of form and function.

Глокая куздра штэка будланула бокра и кудрячит бокрёнка. V. V. Vinogradov

Green ideas sleep furiously.

Such examples though being artificial help us to understand that — grammatical meaning is an objective thing by itself though in real speech it never exists without lexical meaning.

2) Form, (morphological properties) The formal criterion concerns the inflectional and derivational features of words belonging to a given class. That is the grammatical categories they possess, the paradigms they form and derivational and functional morphemes they have.

With the English language this criterion is not always reliable as many words in English are invariable, many words have no derivational affixes and besides the same derivational affixes may be used to build different parts of speech.(e.g. «~ly»: quickly , daily , weakly(n.)).

Because of the limitation of meaning and form as criterion we should rely mainly on words’ syntactic functions (e.g. «round» can be adjective, noun, verb, preposition).

3) Function. Syntactic properties of any class of words are: combinability (distributional criterion), typical syntactic functions in a sentence. The three criteria of defining grammatical classes of words in English may be placed in the following order: syntactic, distribution, form, meaning (Russian: form, meaning, syntactic distribution).

Parts of speech are heterogeneous classes and the boundaries between them are not clearly cut especially in the area of meaning. Within a part of speech there are subclasses which have all the properties of a given class and subclasses which have only some of these properties and may even have features of another class.

So a part of speech may be described as a field which includes both central (most typical) members and marginal (less typical) members. Marginal areas of different parts of speech may overlap and there may be intermediary elements with contradicting features (modal words, statives, pronouns and even verbs).

Words belonging to different parts of speech may be united by common feature and they may constitute a class cutting across other classes (e.g. determiners or quantifiers).

Possible Ways of the Grammatical Classification of the Vocabulary.

The parts of speech and their classification usually involves all the four criteria mentioned and scholars single out from 8 to 13 parts of speech in modern English. The founder of English scientific grammar Henry Sweet finds the following classes of words: noun-words ( here he includes some pronouns and numerals), adjective-words, verbs 4 particles (by this term he denotes words of different classes which have no grammatical categories).

The opposite criterion — structural or distributional — was used by an American scholar Charles Freeze. Each class of words is characterized by a set of positions in a sentence which are defined by substitution test. As a result of distributional analysis Freeze singles out 4 main classes of words roughly corresponding to verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs and 15 classes of function-words.

Notional and Functional Parts of Speech.

Both the traditional and distributional classification divide parts of speech into notional and functional. Notional parts of speech are open classes, new items can be added to them, we extend them indefinitely. Functional parts of speech are closed systems including a limited number of members. As a rule they cannot be extended by creating new items.

Main notional parts of speech are nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs. Members of these four classes are often connected derivationally. Functional parts of speech are prepositions, conjunctions, articles, interjections & particles. Their distinctive features are:

— very general & weak lexical meaning;

— obligatory combinability;

The function of linking and specifying words.

Pronouns constitute a class of words which takes an intermediary position between notional and functional words: on the one hand they can substitute nouns and adjectives; on the other hand they can be used as connectives and specifiers. There may be also groups of closed-system items within an open class (notional, functional and auxiliary verbs).

A word in English is very often not marked morphologically. It makes it easy for words to pass from one class to another. Such words are treated as either lexico-semantic phonemes or as words belonging to one class. The problem which is closely connected with the selection of parts of speech is the problem of conversion.

There are usually the cases of absolute, phonetic identity of words belonging to different parts of speech. About 45% of nouns can be converted into verbs and about 50% of verbs — into nouns. There are different viewpoints on conversion: some scholars think that it is a syntactic word-building means. If they say so they do admit that the word may function as parts of speech at the same time.

Russian linguist Galperin defines conversion as a non-affix way of forming words. There is another theory by French linguist Morshaw who states that conversion is a creation of new words with zero-affix. In linguistics this problem is called «stone-wall-construction problem».

Another factor which makes difficult to select parts of speech, in English is abundance of homonyms in English. They are words and forms identical in form, sounding, spelling, but different in meaning. Usually the great number of homonyms in English is explained by monosyllabic structure of words but it’s not all the explanation.

The words are monosyllabic in English because there are few endings in it, because English is predominantly analytical. We differentiate between full and partial homonymity, we usually observe full homonymity within one pan of speech and partial — within different parts of speech. If we have two homonyms within one part of speech their paradigms should fully coincide.

Homonyms can be classified into lexical, lexico-grammatical and purely grammatical. We should differentiate between homonymity and polysemantic words.

If you’re trying to learn the grammatical rules of English, you’ve probably been asked to learn the parts of speech. But what are parts of speech and how many are there? How do you know which words are classified in each part of speech?

The answers to these questions can be a bit complicated—English is a difficult language to learn and understand. Don’t fret, though! We’re going to answer each of these questions for you with a full guide to the parts of speech that explains the following:

- What the parts of speech are, including a comprehensive parts of speech list

- Parts of speech definitions for the individual parts of speech. (If you’re looking for information on a specific part of speech, you can search for it by pressing Command + F, then typing in the part of speech you’re interested in.)

- Parts of speech examples

- A ten question quiz covering parts of speech definitions and parts of speech examples

We’ve got a lot to cover, so let’s begin!

Feature Image: (Gavina S / Wikimedia Commons)

What Are Parts of Speech?

The parts of speech definitions in English can vary, but here’s a widely accepted one: a part of speech is a category of words that serve a similar grammatical purpose in sentences.

To make that definition even simpler, a part of speech is just a category for similar types of words. All of the types of words included under a single part of speech function in similar ways when they’re used properly in sentences.

In the English language, it’s commonly accepted that there are 8 parts of speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, conjunctions, interjections, and prepositions. Each of these categories plays a different role in communicating meaning in the English language. Each of the eight parts of speech—which we might also call the “main classes” of speech—also have subclasses. In other words, we can think of each of the eight parts of speech as being general categories for different types within their part of speech. There are different types of nouns, different types of verbs, different types of adjectives, adverbs, pronouns…you get the idea.

And that’s an overview of what a part of speech is! Next, we’ll explain each of the 8 parts of speech—definitions and examples included for each category.

There are tons of nouns in this picture. Can you find them all?

#1: Nouns

Nouns are a class of words that refer, generally, to people and living creatures, objects, events, ideas, states of being, places, and actions. You’ve probably heard English nouns referred to as “persons, places, or things.” That definition is a little simplistic, though—while nouns do include people, places, and things, “things” is kind of a vague term. It’s important to recognize that “things” can include physical things—like objects or belongings—and nonphysical, abstract things—like ideas, states of existence, and actions.

Since there are many different types of nouns, we’ll include several examples of nouns used in a sentence while we break down the subclasses of nouns next!

Subclasses of Nouns, Including Examples

As an open class of words, the category of “nouns” has a lot of subclasses. The most common and important subclasses of nouns are common nouns, proper nouns, concrete nouns, abstract nouns, collective nouns, and count and mass nouns. Let’s break down each of these subclasses!

Common Nouns and Proper Nouns

Common nouns are generic nouns—they don’t name specific items. They refer to people (the man, the woman), living creatures (cat, bird), objects (pen, computer, car), events (party, work), ideas (culture, freedom), states of being (beauty, integrity), and places (home, neighborhood, country) in a general way.

Proper nouns are sort of the counterpart to common nouns. Proper nouns refer to specific people, places, events, or ideas. Names are the most obvious example of proper nouns, like in these two examples:

Common noun: What state are you from?

Proper noun: I’m from Arizona.

Whereas “state” is a common noun, Arizona is a proper noun since it refers to a specific state. Whereas “the election” is a common noun, “Election Day” is a proper noun. Another way to pick out proper nouns: the first letter is often capitalized. If you’d capitalize the word in a sentence, it’s almost always a proper noun.

Concrete Nouns and Abstract Nouns

Concrete nouns are nouns that can be identified through the five senses. Concrete nouns include people, living creatures, objects, and places, since these things can be sensed in the physical world. In contrast to concrete nouns, abstract nouns are nouns that identify ideas, qualities, concepts, experiences, or states of being. Abstract nouns cannot be detected by the five senses. Here’s an example of concrete and abstract nouns used in a sentence:

Concrete noun: Could you please fix the weedeater and mow the lawn?

Abstract noun: Aliyah was delighted to have the freedom to enjoy the art show in peace.

See the difference? A weedeater and the lawn are physical objects or things, and freedom and peace are not physical objects, though they’re “things” people experience! Despite those differences, they all count as nouns.

Collective Nouns, Count Nouns, and Mass Nouns

Nouns are often categorized based on number and amount. Collective nouns are nouns that refer to a group of something—often groups of people or a type of animal. Team, crowd, and herd are all examples of collective nouns.

Count nouns are nouns that can appear in the singular or plural form, can be modified by numbers, and can be described by quantifying determiners (e.g. many, most, more, several). For example, “bug” is a count noun. It can occur in singular form if you say, “There is a bug in the kitchen,” but it can also occur in the plural form if you say, “There are many bugs in the kitchen.” (In the case of the latter, you’d call an exterminator…which is an example of a common noun!) Any noun that can accurately occur in one of these singular or plural forms is a count noun.

Mass nouns are another type of noun that involve numbers and amount. Mass nouns are nouns that usually can’t be pluralized, counted, or quantified and still make sense grammatically. “Charisma” is an example of a mass noun (and an abstract noun!). For example, you could say, “They’ve got charisma,” which doesn’t imply a specific amount. You couldn’t say, “They’ve got six charismas,” or, “They’ve got several charismas.” It just doesn’t make sense!

Verbs are all about action…just like these runners.

#2: Verbs

A verb is a part of speech that, when used in a sentence, communicates an action, an occurrence, or a state of being. In sentences, verbs are the most important part of the predicate, which explains or describes what the subject of the sentence is doing or how they are being. And, guess what? All sentences contain verbs!

There are many words in the English language that are classified as verbs. A few common verbs include the words run, sing, cook, talk, and clean. These words are all verbs because they communicate an action performed by a living being. We’ll look at more specific examples of verbs as we discuss the subclasses of verbs next!

Subclasses of Verbs, Including Examples

Like nouns, verbs have several subclasses. The subclasses of verbs include copular or linking verbs, intransitive verbs, transitive verbs, and ditransitive or double transitive verbs. Let’s dive into these subclasses of verbs!

Copular or Linking Verbs

Copular verbs, or linking verbs, are verbs that link a subject with its complement in a sentence. The most familiar linking verb is probably be. Here’s a list of other common copular verbs in English: act, be, become, feel, grow, seem, smell, and taste.

So how do copular verbs work? Well, in a sentence, if we said, “Michi is,” and left it at that, it wouldn’t make any sense. “Michi,” the subject, needs to be connected to a complement by the copular verb “is.” Instead, we could say, “Michi is leaving.” In that instance, is links the subject of the sentence to its complement.

Transitive Verbs, Intransitive Verbs, and Ditransitive Verbs

Transitive verbs are verbs that affect or act upon an object. When unattached to an object in a sentence, a transitive verb does not make sense. Here’s an example of a transitive verb attached to (and appearing before) an object in a sentence:

Please take the clothes to the dry cleaners.

In this example, “take” is a transitive verb because it requires an object—”the clothes”—to make sense. “The clothes” are the objects being taken. “Please take” wouldn’t make sense by itself, would it? That’s because the transitive verb “take,” like all transitive verbs, transfers its action onto another being or object.

Conversely, intransitive verbs don’t require an object to act upon in order to make sense in a sentence. These verbs make sense all on their own! For instance, “They ran,” “We arrived,” and, “The car stopped” are all examples of sentences that contain intransitive verbs.

Finally, ditransitive verbs, or double transitive verbs, are a bit more complicated. Ditransitive verbs are verbs that are followed by two objects in a sentence. One of the objects has the action of the ditransitive verb done to it, and the other object has the action of the ditransitive verb directed towards it. Here’s an example of what that means in a sentence:

I cooked Nathan a meal.

In this example, “cooked” is a ditransitive verb because it modifies two objects: Nathan and meal. The meal has the action of “cooked” done to it, and “Nathan” has the action of the verb directed towards him.

Adjectives are descriptors that help us better understand a sentence. A common adjective type is color.

#3: Adjectives

Here’s the simplest definition of adjectives: adjectives are words that describe other words. Specifically, adjectives modify nouns and noun phrases. In sentences, adjectives appear before nouns and pronouns (they have to appear before the words they describe!).

Adjectives give more detail to nouns and pronouns by describing how a noun looks, smells, tastes, sounds, or feels, or its state of being or existence.. For example, you could say, “The girl rode her bike.” That sentence doesn’t have any adjectives in it, but you could add an adjective before both of the nouns in the sentence—”girl” and “bike”—to give more detail to the sentence. It might read like this: “The young girl rode her red bike.” You can pick out adjectives in a sentence by asking the following questions:

- Which one?

- What kind?

- How many?

- Whose’s?

We’ll look at more examples of adjectives as we explore the subclasses of adjectives next!

Subclasses of Adjectives, Including Examples

Subclasses of adjectives include adjective phrases, comparative adjectives, superlative adjectives, and determiners (which include articles, possessive adjectives, and demonstratives).

Adjective Phrases

An adjective phrase is a group of words that describe a noun or noun phrase in a sentence. Adjective phrases can appear before the noun or noun phrase in a sentence, like in this example:

The extremely fragile vase somehow did not break during the move.

In this case, extremely fragile describes the vase. On the other hand, adjective phrases can appear after the noun or noun phrase in a sentence as well:

The museum was somewhat boring.

Again, the phrase somewhat boring describes the museum. The takeaway is this: adjective phrases describe the subject of a sentence with greater detail than an individual adjective.

Comparative Adjectives and Superlative Adjectives

Comparative adjectives are used in sentences where two nouns are compared. They function to compare the differences between the two nouns that they modify. In sentences, comparative adjectives often appear in this pattern and typically end with -er. If we were to describe how comparative adjectives function as a formula, it might look something like this:

Noun (subject) + verb + comparative adjective + than + noun (object).

Here’s an example of how a comparative adjective would work in that type of sentence:

The horse was faster than the dog.

The adjective faster compares the speed of the horse to the speed of the dog. Other common comparative adjectives include words that compare distance (higher, lower, farther), age (younger, older), size and dimensions (bigger, smaller, wider, taller, shorter), and quality or feeling (better, cleaner, happier, angrier).

Superlative adjectives are adjectives that describe the extremes of a quality that applies to a subject being compared to a group of objects. Put more simply, superlative adjectives help show how extreme something is. In sentences, superlative adjectives usually appear in this structure and end in -est:

Noun (subject) + verb + the + superlative adjective + noun (object).

Here’s an example of a superlative adjective that appears in that type of sentence:

Their story was the funniest story.

In this example, the subject—story—is being compared to a group of objects—other stories. The superlative adjective “funniest” implies that this particular story is the funniest out of all the stories ever, period. Other common superlative adjectives are best, worst, craziest, and happiest…though there are many more than that!

It’s also important to know that you can often omit the object from the end of the sentence when using superlative adjectives, like this: “Their story was the funniest.” We still know that “their story” is being compared to other stories without the object at the end of the sentence.

Determiners

The last subclass of adjectives we want to look at are determiners. Determiners are words that determine what kind of reference a noun or noun phrase makes. These words are placed in front of nouns to make it clear what the noun is referring to. Determiners are an example of a part of speech subclass that contains a lot of subclasses of its own. Here is a list of the different types of determiners:

- Definite article: the

- Indefinite articles: a, an

- Demonstratives: this, that, these, those

- Pronouns and possessive determiners: my, your, his, her, its, our, their

- Quantifiers: a little, a few, many, much, most, some, any, enough

- Numbers: one, twenty, fifty

- Distributives: all, both, half, either, neither, each, every

- Difference words: other, another

- Pre-determiners: such, what, rather, quite

Here are some examples of how determiners can be used in sentences:

Definite article: Get in the car.

Demonstrative: Could you hand me that magazine?

Possessive determiner: Please put away your clothes.

Distributive: He ate all of the pie.

Though some of the words above might not seem descriptive, they actually do describe the specificity and definiteness, relationship, and quantity or amount of a noun or noun phrase. For example, the definite article “the” (a type of determiner) indicates that a noun refers to a specific thing or entity. The indefinite article “an,” on the other hand, indicates that a noun refers to a nonspecific entity.

One quick note, since English is always more complicated than it seems: while articles are most commonly classified as adjectives, they can also function as adverbs in specific situations, too. Not only that, some people are taught that determiners are their own part of speech…which means that some people are taught there are 9 parts of speech instead of 8!

It can be a little confusing, which is why we have a whole article explaining how articles function as a part of speech to help clear things up.

Adverbs can be used to answer questions like «when?» and «how long?»

#4 Adverbs

Adverbs are words that modify verbs, adjectives (including determiners), clauses, prepositions, and sentences. Adverbs typically answer the questions how?, in what way?, when?, where?, and to what extent? In answering these questions, adverbs function to express frequency, degree, manner, time, place, and level of certainty. Adverbs can answer these questions in the form of single words, or in the form of adverbial phrases or adverbial clauses.

Adverbs are commonly known for being words that end in -ly, but there’s actually a bit more to adverbs than that, which we’ll dive into while we look at the subclasses of adverbs!

Subclasses Of Adverbs, Including Examples

There are many types of adverbs, but the main subclasses we’ll look at are conjunctive adverbs, and adverbs of place, time, manner, degree, and frequency.

Conjunctive Adverbs

Conjunctive adverbs look like coordinating conjunctions (which we’ll talk about later!), but they are actually their own category: conjunctive adverbs are words that connect independent clauses into a single sentence. These adverbs appear after a semicolon and before a comma in sentences, like in these two examples:

She was exhausted; nevertheless, she went for a five mile run.

They didn’t call; instead, they texted.

Though conjunctive adverbs are frequently used to create shorter sentences using a semicolon and comma, they can also appear at the beginning of sentences, like this:

He chopped the vegetables. Meanwhile, I boiled the pasta.

One thing to keep in mind is that conjunctive adverbs come with a comma. When you use them, be sure to include a comma afterward!

There are a lot of conjunctive adverbs, but some common ones include also, anyway, besides, finally, further, however, indeed, instead, meanwhile, nevertheless, next, nonetheless, now, otherwise, similarly, then, therefore, and thus.

Adverbs of Place, Time, Manner, Degree, and Frequency

There are also adverbs of place, time, manner, degree, and frequency. Each of these types of adverbs express a different kind of meaning.

Adverbs of place express where an action is done or where an event occurs. These are used after the verb, direct object, or at the end of a sentence. A sentence like “She walked outside to watch the sunset” uses outside as an adverb of place.

Adverbs of time explain when something happens. These adverbs are used at the beginning or at the end of sentences. In a sentence like “The game should be over soon,” soon functions as an adverb of time.

Adverbs of manner describe the way in which something is done or how something happens. These are the adverbs that usually end in the familiar -ly. If we were to write “She quickly finished her homework,” quickly is an adverb of manner.

Adverbs of degree tell us the extent to which something happens or occurs. If we were to say “The play was quite interesting,” quite tells us the extent of how interesting the play was. Thus, quite is an adverb of degree.

Finally, adverbs of frequency express how often something happens. In a sentence like “They never know what to do with themselves,” never is an adverb of frequency.

Five subclasses of adverbs is a lot, so we’ve organized the words that fall under each category in a nifty table for you here:

|

Adverbs of Place |

Adverbs of Time |

Adverbs of Manner |

Adverbs of Degree |

Adverbs of Frequency |

|

Above |

Afterwards |

Badly |

Almost |

Again |

|

Below |

Already |

Happily |

Much |

Always |

|

Here |

Always |

Sadly |

Nearly |

Ever |

|

Outside |

Immediately |

Slowly |

Quite |

Frequently |

|

Over there |

Last (month, week, year) |

Quickly |

Really |

Generally |

|

There |

Now |

Well |

So |

Hardly ever |

|

Under |

Soon |

Hard |

Too |

Nearly |

|

Upstairs |

Then |

Fast |

Very |

Never |

|

Yesterday |

Occasionally |

It’s important to know about these subclasses of adverbs because many of them don’t follow the old adage that adverbs end in -ly.

Here’s a helpful list of pronouns.

(Attanata / Flickr)

#5: Pronouns

Pronouns are words that can be substituted for a noun or noun phrase in a sentence. Pronouns function to make sentences less clunky by allowing people to avoid repeating nouns over and over. For example, if you were telling someone a story about your friend Destiny, you wouldn’t keep repeating their name over and over again every time you referred to them. Instead, you’d use a pronoun—like they or them—to refer to Destiny throughout the story.

Pronouns are typically short words, often only two or three letters long. The most familiar pronouns in the English language are they, she, and he. But these aren’t the only pronouns. There are many more pronouns in English that fall under different subclasses!

Subclasses of Pronouns, Including Examples

There are many subclasses of pronouns, but the most commonly used subclasses are personal pronouns, possessive pronouns, demonstrative pronouns, indefinite pronouns, and interrogative pronouns.

Personal Pronouns

Personal pronouns are probably the most familiar type of pronoun. Personal pronouns include I, me, you, she, her, him, he, we, us, they, and them. These are called personal pronouns because they refer to a person! Personal pronouns can replace specific nouns in sentences, like a person’s name, or refer to specific groups of people, like in these examples:

Did you see Gia pole vault at the track meet? Her form was incredible!

The Cycling Club is meeting up at six. They said they would be at the park.

In both of the examples above, a pronoun stands in for a proper noun to avoid repetitiveness. Her replaces Gia in the first example, and they replaces the Cycling Club in the second example.

(It’s also worth noting that personal pronouns are one of the easiest ways to determine what point of view a writer is using.)

Possessive Pronouns

Possessive pronouns are used to indicate that something belongs to or is the possession of someone. The possessive pronouns fall into two categories: limiting and absolute. In a sentence, absolute possessive pronouns can be substituted for the thing that belongs to a person, and limiting pronouns cannot.

The limiting pronouns are my, your, its, his, her, our, their, and whose, and the absolute pronouns are mine, yours, his, hers, ours, and theirs. Here are examples of a limiting possessive pronoun and absolute possessive pronoun used in a sentence:

Limiting possessive pronoun: Juan is fixing his car.

In the example above, the car belongs to Juan, and his is the limiting possessive pronoun that shows the car belongs to Juan. Now, here’s an example of an absolute pronoun in a sentence:

Absolute possessive pronoun: Did you buy your tickets? We already bought ours.

In this example, the tickets belong to whoever we is, and in the second sentence, ours is the absolute possessive pronoun standing in for the thing that “we” possess—the tickets.

Demonstrative Pronouns, Interrogative Pronouns, and Indefinite Pronouns

Demonstrative pronouns include the words that, this, these, and those. These pronouns stand in for a noun or noun phrase that has already been mentioned in a sentence or conversation. This and these are typically used to refer to objects or entities that are nearby distance-wise, and that and those usually refer to objects or entities that are farther away. Here’s an example of a demonstrative pronoun used in a sentence:

The books are stacked up in the garage. Can you put those away?

The books have already been mentioned, and those is the demonstrative pronoun that stands in to refer to them in the second sentence above. The use of those indicates that the books aren’t nearby—they’re out in the garage. Here’s another example:

Do you need shoes? Here…you can borrow these.

In this sentence, these refers to the noun shoes. Using the word these tells readers that the shoes are nearby…maybe even on the speaker’s feet!

Indefinite pronouns are used when it isn’t necessary to identify a specific person or thing. The indefinite pronouns are one, other, none, some, anybody, everybody, and no one. Here’s one example of an indefinite pronoun used in a sentence:

Promise you can keep a secret?

Of course. I won’t tell anyone.

In this example, the person speaking in the second two sentences isn’t referring to any particular people who they won’t tell the secret to. They’re saying that, in general, they won’t tell anyone. That doesn’t specify a specific number, type, or category of people who they won’t tell the secret to, which is what makes the pronoun indefinite.

Finally, interrogative pronouns are used in questions, and these pronouns include who, what, which, and whose. These pronouns are simply used to gather information about specific nouns—persons, places, and ideas. Let’s look at two examples of interrogative pronouns used in sentences:

Do you remember which glass was mine?

What time are they arriving?

In the first glass, the speaker wants to know more about which glass belongs to whom. In the second sentence, the speaker is asking for more clarity about a specific time.

Conjunctions hook phrases and clauses together so they fit like pieces of a puzzle.

#6: Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that are used to connect words, phrases, clauses, and sentences in the English language. This function allows conjunctions to connect actions, ideas, and thoughts as well. Conjunctions are also used to make lists within sentences. (Conjunctions are also probably the most famous part of speech, since they were immortalized in the famous “Conjunction Junction” song from Schoolhouse Rock.)

You’re probably familiar with and, but, and or as conjunctions, but let’s look into some subclasses of conjunctions so you can learn about the array of conjunctions that are out there!

Subclasses of Conjunctions, Including Examples

Coordinating conjunctions, subordinating conjunctions, and correlative conjunctions are three subclasses of conjunctions. Each of these types of conjunctions functions in a different way in sentences!

Coordinating Conjunctions

Coordinating conjunctions are probably the most familiar type of conjunction. These conjunctions include the words for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so (people often recommend using the acronym FANBOYS to remember the seven coordinating conjunctions!).

Coordinating conjunctions are responsible for connecting two independent clauses in sentences, but can also be used to connect two words in a sentence. Here are two examples of coordinating conjunctions that connect two independent clauses in a sentence:

He wanted to go to the movies, but he couldn’t find his car keys.

They put on sunscreen, and they went to the beach.

Next, here are two examples of coordinating conjunctions that connect two words:

Would you like to cook or order in for dinner?

The storm was loud yet refreshing.

The two examples above show that coordinating conjunctions can connect different types of words as well. In the first example, the coordinating conjunction “or” connects two verbs; in the second example, the coordinating conjunction “yet” connects two adjectives.

But wait! Why does the first set of sentences have commas while the second set of sentences doesn’t? When using a coordinating conjunction, put a comma before the conjunction when it’s connecting two complete sentences. Otherwise, there’s no comma necessary.

Subordinating Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunctions are used to link an independent clause to a dependent clause in a sentence. This type of conjunction always appears at the beginning of a dependent clause, which means that subordinating conjunctions can appear at the beginning of a sentence or in the middle of a sentence following an independent clause. (If you’re unsure about what independent and dependent clauses are, be sure to check out our guide to compound sentences.)

Here is an example of a subordinating conjunction that appears at the beginning of a sentence:

Because we were hungry, we ordered way too much food.

Now, here’s an example of a subordinating conjunction that appears in the middle of a sentence, following an independent clause and a comma:

Rakim was scared after the power went out.

See? In the example above, the subordinating conjunction after connects the independent clause Rakim was scared to the dependent clause after the power went out. Subordinating conjunctions include (but are not limited to!) the following words: after, as, because, before, even though, one, since, unless, until, whenever, and while.

Correlative Conjunctions

Finally, correlative conjunctions are conjunctions that come in pairs, like both/and, either/or, and neither/nor. The two correlative conjunctions that come in a pair must appear in different parts of a sentence to make sense—they correlate the meaning in one part of the sentence with the meaning in another part of the sentence. Makes sense, right?

Here are two examples of correlative conjunctions used in a sentence:

We’re either going to the Farmer’s Market or the Natural Grocer’s for our shopping today.

They’re going to have to get dog treats for both Piper and Fudge.

Other pairs of correlative conjunctions include as many/as, not/but, not only/but also, rather/than, such/that, and whether/or.

Interjections are single words that express emotions that end in an exclamation point. Cool!

#7: Interjections

Interjections are words that often appear at the beginning of sentences or between sentences to express emotions or sentiments such as excitement, surprise, joy, disgust, anger, or even pain. Commonly used interjections include wow!, yikes!, ouch!, or ugh! One clue that an interjection is being used is when an exclamation point appears after a single word (but interjections don’t have to be followed by an exclamation point). And, since interjections usually express emotion or feeling, they’re often referred to as being exclamatory. Wow!

Interjections don’t come together with other parts of speech to form bigger grammatical units, like phrases or clauses. There also aren’t strict rules about where interjections should appear in relation to other sentences. While it’s common for interjections to appear before sentences that describe an action or event that the interjection helps explain, interjections can appear after sentences that contain the action they’re describing as well.

Subclasses of Interjections, Including Examples

There are two main subclasses of interjections: primary interjections and secondary interjections. Let’s take a look at these two types of interjections!

Primary Interjections

Primary interjections are single words, like oh!, wow!, or ouch! that don’t enter into the actual structure of a sentence but add to the meaning of a sentence. Here’s an example of how a primary interjection can be used before a sentence to add to the meaning of the sentence that follows it:

Ouch! I just burned myself on that pan!

While someone who hears, I just burned myself on that pan might assume that the person who said that is now in pain, the interjection Ouch! makes it clear that burning oneself on the pan definitely was painful.

Secondary Interjections

Secondary interjections are words that have other meanings but have evolved to be used like interjections in the English language and are often exclamatory. Secondary interjections can be mixed with greetings, oaths, or swear words. In many cases, the use of secondary interjections negates the original meaning of the word that is being used as an interjection. Let’s look at a couple of examples of secondary interjections here:

Well, look what the cat dragged in!

Heck, I’d help if I could, but I’ve got to get to work.

You probably know that the words well and heck weren’t originally used as interjections in the English language. Well originally meant that something was done in a good or satisfactory way, or that a person was in good health. Over time and through repeated usage, it’s come to be used as a way to express emotion, such as surprise, anger, relief, or resignation, like in the example above.

This is a handy list of common prepositional phrases.

(attanatta / Flickr)

#8: Prepositions

The last part of speech we’re going to define is the preposition. Prepositions are words that are used to connect other words in a sentence—typically nouns and verbs—and show the relationship between those words. Prepositions convey concepts such as comparison, position, place, direction, movement, time, possession, and how an action is completed.

Subclasses of Prepositions, Including Examples

The subclasses of prepositions are simple prepositions, double prepositions, participle prepositions, and prepositional phrases.

Simple Prepositions

Simple prepositions appear before and between nouns, adjectives, or adverbs in sentences to convey relationships between people, living creatures, things, or places. Here are a couple of examples of simple prepositions used in sentences:

I’ll order more ink before we run out.

Your phone was beside your wallet.

In the first example, the preposition before appears between the noun ink and the personal pronoun we to convey a relationship. In the second example, the preposition beside appears between the verb was and the possessive pronoun your.

In both examples, though, the prepositions help us understand how elements in the sentence are related to one another. In the first sentence, we know that the speaker currently has ink but needs more before it’s gone. In the second sentence, the preposition beside helps us understand how the wallet and the phone are positioned relative to one another!

Double Prepositions

Double prepositions are exactly what they sound like: two prepositions joined together into one unit to connect phrases, nouns, and pronouns with other words in a sentence. Common examples of double prepositions include outside of, because of, according to, next to, across from, and on top of. Here is an example of a double preposition in a sentence:

I thought you were sitting across from me.

You see? Across and from both function as prepositions individually. When combined together in a sentence, they create a double preposition. (Also note that the prepositions help us understand how two people—you and I—are positioned with one another through spacial relationship.)

Prepositional Phrases