In spoken and written English, the word “all” has several functions. It can be used as a adjective, an adverb, a noun, or a pronoun.

- Adjective

This word can be categorized as an adjective if it is used to introduce a noun in the sentence. Generally, the word “all” expresses the entire quantity or extent of something. For example, in the sentence below:

All students were present.

The word “all” is considered as a adjective because it introduces the noun “students.”

Definition:

a. used to refer to the whole quantity or extent of a particular group or thing

- Example:

- All men are equal.

2 . Adverb

The word “all” can also be considered as an adverb if it is used to modify a verb, an adjective, or another adverb. For instance, in the sample sentence below:

She is dressed all in white.

This word is classified as an adverb because it modifies the verb “dressed.”

Definition:

a. completely; consisting entirely of

- Example:

- I have all leather couches in my home.

3. Noun

There are some cases wherein the word “all” is considered as a noun, which means the entirety of one’s energy or possessions. Take for example, the sentence below:

I gave my all.

In the given example, the word “all” is a noun that refers to the whole possession/energy of the pronoun “I.”

Definition:

a. the whole of one’s possessions, energy, or interest

- Example:

- We are giving our all for what we believe in.

4. Pronoun

Other times, the word “all” serves as a pronoun that represents the whole number or quantity of something. It is classified as a pronoun when it is used to take the place of a noun or a pronoun for the totality of something. For example, in the sentence below:

All of the gadgets were stolen.

The word “all” suggests the whole quantity and replaces the noun “gadgets.”

Definition:

a. the whole number, quantity, or amount

- Example:

- All of us are hungry.

Which part of speech is the word all?

In spoken and written English, the word “all” has several functions. It can be used as a adjective, an adverb, a noun, or a pronoun. This word can be categorized as an adjective if it is used to introduce a noun in the sentence. Generally, the word “all” expresses the entire quantity or extent of something.

What type of a word is all?

indefinite pronoun

What kind of adjective is all?

Quantitative adjectives describe the exact or approximate amount of a noun. Some examples include all, no, few, many, and little. Numeral adjectives are quantitative adjectives that give exact number amounts (e.g. two, seven, thirty, first, and ninth).

What type of pronoun is all?

What is the pronoun of girl?

Pronouns

| Subject pronoun | Object pronoun | |

|---|---|---|

| 3rd person singular, female | she | her |

| 3rd person singular, neutral | it | it |

| 1st person plural | we | us |

| 2nd person plural | you | you |

What are the types of personal pronouns?

Other Types of Pronoun

| Pronoun Type | Members of the Subclass |

|---|---|

| Possessive | mine, yours, his, hers, ours, theirs |

| Reflexive | myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, oneself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves |

| Reciprocal | each other, one another |

| Relative | that, which, who, whose, whom, where, when |

What can I use instead of personal pronouns?

“One,” “the reader,” “readers,” “the viewer,” or something similar sometimes can be used effectively in place of first-person pronouns in formal papers, but be careful not to overuse these expressions. You want to sound formal, not awkward and stiff.

Which pronoun is best avoided?

In academic writing, first-person pronouns (I, we) may be used depending on your field. Second person pronouns (you, yours) should almost always be avoided. Third person pronouns (he, she, they) should be used in a way that avoids gender bias.

What is 2nd person examples?

The second-person point of view belongs to the person (or people) being addressed. This is the “you” perspective. Once again, the biggest indicator of the second person is the use of second-person pronouns: you, your, yours, yourself, yourselves. You can wait in here and make yourself at home.

What is second person in writing?

What Is Second Person POV in Writing? Second person point of view uses the pronoun “you” to address the reader. This narrative voice implies that the reader is either the protagonist or a character in the story and the events are happening to them.

What are the words for second person point of view?

If it uses “you,” “your,” or “yours” as pronouns, then you have a second-person point of view. If it uses “he,” she,” “it,” “they,” “him,” “hers,” “them,” “their,” “his,” “its,” or “theirs” as pronouns, then you have a third-person point of view.

How do you write in second person?

When writing in the second person, address the reader directly. This type of writing feels personal to the reader. Use ‘you’ and ‘your’. “When you see a monster, you should tell them to tidy up.”

Is it bad to write in second person?

One of the main rules of writing formal, academic papers is to avoid using second person. Second person refers to the pronoun you. Formal papers should not address the reader directly. However, it can be difficult to write without second person because the word you is such a major part of our speech.

What effect does 2nd person have?

It affects narrative elements such as tone, theme, and tension, but, most importantly, it affects the relationship between narrator, reader, and protagonist. Second- person point of view creates a unique relationship between narrator, reader, and protagonist that first- and third-person do not share.

Why is 2nd person point of view seldom used?

Benefits of Second-Person Point of View Immerse the reader in the experience of actually being the protagonist. Engage the reader in a rich sensory experience that can best be accomplished by forcing readers to imagine themselves as part of the experience.

What effect does the second person narration have?

“The second person POV brings the reader closer to the narrator, making the reading experience more intimate and less detached. When the narrator turns the reader into one of the characters, the story feels immediate and surrounding.”

Should you write in second person?

When a writer wants the reader to not only live vicariously through the main character but become the protagonist themselves, second person is a good option. It provides the richest sensory experience of any of the points of view because the reader is in the story.

What are the disadvantages of first person narration?

List of Disadvantages of First Person Narration

- It is limited to a single story thread.

- It would risk making the narrative self-indulgent in the narrator’s emotions.

- It tends to be bias.

- It narrows the experience.

- It would be difficult to describe the narrator.

What are the benefits of first person narration?

First person point of view brings readers closer to the character. Because the reader gets to see and hear everything the narrator does, he can also feel or react to events as the narrator does. This makes for a more compelling and relatable read.

What is the purpose of first person narration?

A first-person narrator gives the reader a front row seat to the story. It also: Gives a story credibility. First-person point of view builds a rapport with readers by sharing a personal story directly with them.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of first person narration?

The advantage of first person is that you can immediately connect with the reader. The disadvantage is that the author is limited to writing from one perspective. There are several types of first person narrators: The Protagonist – This is the main character.

Which sentence is an example of first person narration?

“What is he doing here?” I asked my mother, as my uncle’s car pulled into the driveway. Explanation: First-person narration is characterized by the use of first-person pronouns such as I, me, my, we, us and our. The sentence from option B uses the pronouns I and my, which indicates that it is a first-person narration.

Continue Learning about English Language Arts

What part of speech is the word ‘two’?

All numbers are adjectives.

What part of speech is the word my-?

The part of speech that the word my is used as is an

adjective.

What part of the speech is the word warily?

what part of speech is the word warily

Does a dictionary determine the part of speech of a word?

A dictionary can show a word’s part of speech, but it does not

determine it. How a word is used in a sentence determines its part

of speech.

What part of speech is the word specifically?

The part of speech for the word specifically is an adverb.

-

#1

What is » all » grammitically?

What is «all» in the following sentence.

we

all

love our parents.what part of speech all belong here in this sentence to?

Please give me a detail reply .

Khursheed Ahmad Khan

-

#2

What is » all » grammitically?

What is «all» in the following sentence.

weall

love our parents.what part of speech all belong here in this sentence to?

Please give me a detail reply .Khursheed Ahmad Khan

«All» can be several parts of speech. I will give you a dictionary listing at the end.

In your sentence, «all» is a pronoun. It restates «we» and acts as an intensifier so that the reader knows that «we» refers to more than just a small group.

all (ôl)

adj.

- Being or representing the entire or total number, amount, or quantity: All the windows are open. Deal all the cards. See synonyms at whole.

- Constituting, being, or representing the total extent or the whole: all Christendom.

- Being the utmost possible of: argued the case in all seriousness.

- Every: got into all manner of trouble.

- Any whatsoever: beyond all doubt.

- Pennsylvania. Finished; used up: The apples are all. See Regional Note at gum band.

- Informal. Being more than one: Who all came to the party? See Regional Note at you-all.

n.

The whole of one’s fortune, resources, or energy; everything one has: The brave defenders gave their all.

pron.

- The entire or total number, amount, or quantity; totality: All of us are sick. All that I have is yours.

- Everyone; everything: justice for all.

adv.

- Wholly; completely: a room painted all white; directions that were all wrong.

- Each; apiece: a score of five all.

- So much: I am all the better for that experience.

Forward to Navigation

Posted: Jan 04, 2007 12:01;

Last Modified: Jan 25, 2014 14:01

Words are different from each other in meaning—car and unwelcome mean different things, after all.

But they can also differ from each other in more than meaning: they can also differ in the way they are used in sentences.

Thus sentences can be about a word like car more easily than they can be about a word like unwelcome:

- Cars are on the road

- *Unwelcomes are on the road1

With a word like car, we also can talk about one or more examples: a car is here, cars are here. We can describe its qualities using other words like red, fast, or good: “red cars are here”, “fast cars are here”, “good cars are here”. And a word like car can be said to possess things: the car’s tires, cars’ steering wheels

None of this is true of a word like unwelcome. But unwelcome can be used in ways a word like car cannot: it can be used to describe qualities of other words (The unwelcome news, This news was unwelcome, vs. *The car news or [*This news was car); it can be made more intense using words like very or really (it was very unwelcome, vs. *It was very car).

The real test, of course, is that the two words can’t be switched in a sentence. We couldn’t replace car with unwelcome in the example above, and it is impossible2 to replace unwelcome with car in this following sentence:

- That was really unwelcome news.

- That was really *car news.

It is possible, on the other hand, to replace car and unwelcome with other words, even if the meaning of the new words is nothing like that of the words they replace:

- Bartenders are on the road.

- That was really good news.

So why can car be replaced by bartender and not unwelcome or good? And why can unwelcome be replaced by good but not bartender or car?

The answer is that car and bartender, on the one hand, and unwelcome and good, on the other, are different types of words. As we will learn, car and bartender show in normal use most of the properties we associate with nouns while unwelcome and good show in normal use most of the properties we associate with adjectives. The fact that you can replace car with bartender and unwelcome with good shows that you can replace nouns with nouns and adjectives with adjectives more easily than you can replace words of one type with words of a different type.

This tutorial explores this property in greater depth. Traditionally, word classes have been distinguished on semantic grounds (e.g. “Nouns are the names of person places or things”; “verbs are action words”). As this tutorial will demosntrate, these traditional definitions, while not usually wrong, are often quite ambiguous. This is because the class a word belongs to is largely a question of syntax rather than meaning, especially given the ease with which English can move words from one class to another without any change in morphological form.

By the end of this tutorial you should be able to distinguish among word classes confidently.

Previous: Inflections (inflectional morphology) | Next: Grammatical relations

Words and Phrases

If we continue testing like this, we will also soon discover not only that some words are more easily exchanged with one other than with others, but also that individual words can be used to replace entire groups of closely connected words (and vice versa). For example, the word bartenders can replace more than cars in the following sentences; it also can replace entire groups of closely connected words involving cars—groups like the cars, the blue cars, and even the blue cars that sold so well last year:

- Cars are on the road

- The cars are on the road

- The blue cars are on the road

- The blue cars that sold so well last year are on the road

- Bartenders are on the road.

On the other hand, we still can’t use unwelcome to replace cars:

- Cars are on the road.

- *Unwelcomes are on the road.

If we experiment, we will see that we can’t replace just any group of words using bartender: the words need to be somehow more closely related to each other than any other part of the sentence and involve a word like car. In the following sentence, for example, we can use bartenders to replace the blue cars, but not blue cars are on:

- The blue cars are on the road

- Bartenders are on the road

- The blue cars are on the road

- *The bartenders road3.

Clearly there is something about the words the blue cars that makes us think of them as being more closely connected to each other than to anything else in the sentence. And just as the fact that we can replace car with bartender but not unwelcome in the sentences above suggests that there must be something similar about car and bartender, so to the fact that we can use bartenders to replace cars and groups of closely related words like the cars or the blue cars suggests that there must be something similar about the single word cars and these particular combinations of words.

As we shall discover, combinations of closely connected words that behave in much the same way as individual words are known as Phrases. As we define the different types of words below, we will see that each type of word has an associated type of phrase to which many of the same rules apply. This principle will become very important when we come to talk about how sentences are made.

Open and Closed Word Classes

Another difference that separates words is the question of how easy or difficult it is to make up new examples. If I want to replace car or cars in the above sentences with a new word that I will make up myself—say slipshlup—I can do so very easily:

- Cars are on the road

- Slipshlups are on the road

- The cars are on the road

- The slipshlups are on the road

- The blue cars are on the road

- The blue slipshlups are on the road

- The blue cars that sold so well last year are on the road

- The blue slipshlups that sold so well last year are on the road

- Bartenders are on the road.

Likewise, it is not hard to make up a word like unwelcome. How about griopy?

- That was really unwelcome news.

- That was really griopy news.

But if it easy to make up new words parallel to cars and unwelcome, it is much harder—impossible, in fact—to make up replacements for words like the, and, but or he, she, and it. For example, try repeating the following sentence with the following made-up words: hin for the, roop for and, and fries for she.

- The cars and the boats were on the road, but they were not for sale, she said.

Doesn’t make much sense, does it?

The Parts of Speech/Word Classes

If we compare English words in the way discussed above3, we will discover that it is possible to divide words and closely associated groups of words like them into eight main types, known as the parts of speech or word classes (a minor ninth category contains interjections. like “oh dear!” and “damn!” and is not discussed further in this tutorial). We will also discover that these Word Classes themselves fall into two larger groups based on whether or not we can easily add new examples: the Open Class contains word classes that we easily can add to—nouns, adjectives, most types of verbs, and adverbs; the Closed or Structure Class contains words, like prepositions, pronouns, conjunctions, most determiners, and some adverbs, to which we can not add easily:

| Class | Word Class | Examples |

| Open Class | Nouns | car, bartender, experience |

| Adjectives | unwelcome, good, big, blue | |

| Verbs | run, glide, listen, jog | |

| Adverbs | quickly, well, sometimes, badly | |

| Closed Class | Determiners | the, this, mine, Susan’s |

| Prepositions | up, underneath, on, with | |

| Pronouns | I, they, mine, each, these | |

| Conjunctions | and, but, if, because |

Open Classes

Nouns and Noun Phrases

Nouns are naming words. Traditionally they are defined as the names of persons, places, and things, but their actual range is much broader: they can name ideas, moods, and feelings (e.g. neoconservatism, anger, and affection); actions (the hiking), or pretty much anything else known or unknown (e.g. Slipshlup, above).

Fortunately, given how hard it can be to define them by what they describe, nouns and noun phrases can be defined relatively easily by their form and the contexts in which they appear. In particular they show one or more of the following unique features:

- Nouns are the only words that use “apostrophe s” (i.e. ‘s or s’) to show possession. In the following sentence, we know that Dave, Neoconservatism, and anger are all nouns because they indicate possession by adding -‘s: Dave’s book, Neoconservatism’s origins, anger’s solution.

- Nouns are the only words that can be modified by adjectives: blue cars, unwelcome news, clever Sally.

- Nouns are the only words that can be made plural by adding -s: DVD : DVDs, cup : cups, theology : theologies.

- Nouns are the only words that can be pointed to by determiners. Determiners, as we will see below, are words such as the and a, that and this, and possessives such as his or Brigette’s that point out specific instances of a noun, e.g. the boat, a slipshlup, that hiking, Brigette’s DVD, his anger.

- Nouns and Noun Phrases are the only words that can be replaced by a pronoun: The deer grazed quietly at the side of the road : It grazed quietly at the side of the road

Other tests are not entirely exclusive, for example:

- Nouns and pronouns are the only words that can function as the subject of a sentence: The car ran through the red light : It ran through the red light.

It is important to realise in applying these tests that not all words will fit all categories. Some nouns do not form their plural with -s, for example: e.g. child : children; sheep : sheep. What is important is that one or more of these tests be true.

Verbs

Verbs are traditionally defined as “action words.” Even more than with nouns, however, this definition fails to cover more than a narrow range of possible examples or rule out obvious counter-examples. While some verbs do express action (e.g. she hit the wall with a hammer), others do not (e.g. I am the king, he knows his baseball). Moreover, actions can also be named by nouns: This hiking is very hard; I don’t like all this hitting).

Like nouns, verbs can be defined more accurately on grammatical criteria. Particularly useful ones include:

- Verbs are the only words that show tense (i.e. past or present): he loves cheesecake : he loved cheesecake; I drive fast : I drove fast.

- Verbs are the only words that indicate third person singular, present by adding -s at the end: I drive, he drives

- Verbs are the only words that can be made into participles (i.e. adjective forms) using the endings -ed, -en, or -ing: I love : loving : loved; They drive : driving : driven

Verb Phrases include the verb plus all objects and modifiers. These can get quite large. One test for some verb phrases is replacement by do in questions designed to be answered with “yes” or “no”.

- Bobbi loves getting presents in the morning, does she?

In asking the question “does she”, the speaker is summing up the whole idea “loves getting presents in the morning” by a single form of do. This shows that “loves getting presents in the morning” is a Verb Phrase.

Adjectives

Adjectives describe qualities to nouns. One easy test, though it is also true of adverbs, is placing very or really in front:

- Adjectives and adverbs are the only words that can be made more intense by adding very or really in front: the really fast car was very red

Here are some tests that are only true of adjectives:

- Adjectives are the only words that can have endings to indicate that something is more or most in relation to some quality: the fast car was red : the faster car was green : the fastest car was blue. Of course some adjectives don’t use -er and/or -est: more unwelcome not *unwelcomer; best nor goodest.

- Adjectives and adjective phrases are the only words that can appear between determiners (like the, a, or possessives) and nouns: the fast car, Dave’s really nice cake, a very sad clown.

Adverbs

Adverbs are traditionally described as words that modify verbs. In fact there are three different kinds of adverbs, each of which can be distinguished by context.

Intensifying adverbs

Intensifying adverbs are words like very that are used to qualify adjectives and other adverbs. They do not qualify verbs directly: his very angry cousin vs. *he very jumps. Some intensifying adverbs can be used with slightly different meaning to modify verbs: he skates really fast, he really skates.

Sentence adverbs

Sentence adverbs qualify sentences and clauses: Unfortunately, the boat sank; I don’t want to, however; then he knew for sure.

Verbal adverbs

Verbal adverbs qualify verbs: He jumped quickly, he wrote well. Like adjectives, they can be intensified by words like very: she drove very quickly, Beatrice cooks really well.

Closed class words

Determiners

Determiners are words that are used to point out specific instances of a noun. They include the articles (a, the), demonstratives (this/these, that/those), and all possessive nouns and pronouns (this means that a form like Dave’s in Dave’s book is both a noun and a determiner).

The test for determiners is very straightforward:

- Determiners precede nouns and any qualifying adjectives. The first word in each of the following phrases is a determiner: the book, the large book, Dave’s really ugly book, my car, my sister’s car (in this last example, both my and my sister’s are determiners: my points to sister and my sister’s points to car).

Prepositions

Prepositions serve to connect nouns or noun phrases (e.g. cars or the car) to a clause or sentence. Examples include up a mountain, down the street, with friends, beside him, without a wooden paddle.

In English, there are a relatively small number of simple prepositions, such as up, down, with. There are also a number of phrasal or compound prepositions, especially in spoken English: outside of the English, apart from Dave’s cat, round and round the mountain.

Many of the prepositions can be memorised. Otherwise, prepositions can be recognised by their syntactic context:

- Prepositions are always followed by noun phrases (i.e. nouns with any associated determiners and adjectives, or pronouns) that serve as their objects5.

Pronouns

Pronouns are words that can substitute for nouns or noun phrases. Examples include personal pronouns like she/her, I/me/my, they/them/their; demonstratives like this/these, that/those; and other forms, such as each, none, and one:

- My sister is here. She wants to talk to you.

- The green carrots are probably rotten. I wouldn’t eat them.

- My books are here. These over here are yours.

- The members of the committee were awstruck. None had expected this.

Because pronouns replace nouns, they can be identified using some of the same tests. In particular,

- Pronouns (with nouns) are the only words that can serve as the subject of a sentence: he ran the country; she scored five goals; it was hit by a train.

- Pronouns (with nouns) are the only words that can serve as the object of a verb or preposition: outside this, with him, she cut it.

- Pronouns (with nouns) are the only words that can take a possessive inflection—though unlike nouns, the possessive is never ‘s or s’ and rarely s: my books, your garage, her cannon, his snow shovel6.

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are used to join grammatical units. Unlike prepositions, which join nouns or noun phrases to sentences, conjunctions always join elements of a similar kind: nouns and noun phrases to other nouns and noun phrases, verbs to verbs, adjectives to adjectives: it is raining cats and dogs (noun to noun); I neither pushed nor pulled (verb to verb); I went out because he didn’t come in (clause to clause).

Exercises

(Click here for Answers)

The following exercises test you on your ability to apply the above material. The real test of your knowledge of grammar is not whether you are able to memorise terms and definitions, but whether you can supply examples and describe real-life sentences.

1. Place each word in the following sentence in its Word Class using the above tests. Which Word Class(es) is or are missing?:

Over the mountain lived a former mechanic. Suzy forgets his name.

2. When Hamlet says that bad acting “out-herods Herod” (Hamlet, III.ii), meaning to rage and rant, he is using a proper name for a verb. What tests can we use to show that out-herods is a verb?

3. Although it is impossible for individuals to create new Closed or Structure Class words, the English language has acquired new pronouns over the course of its history: the entire plural pronoun system they, them, their comes from Old Norse (the original English version was hie, hira and him); she is of unknown origin (the original was heo).

Can you suggest some reasons why it is possible for languages to add or change such words but not for individuals?

Notes

1 An asterisk (i.e. *) in front of a word or group of words means “This word or group of words is not something people would say”. An explanation mark (i.e. !) in front of a word or a group of words means “It is doubtful that this is something people would say” or “People might say this, but only in special circumstances”

2 “Impossible” may seem too definite at first. In fact it is almost always possible to think of a situation in which a grammatical rule might be shown to be wrong: for example, let’s say we were talking about a band called “The Unwelcome“—then they probably could replace car in our example sentences.

As a rule, however, you should always be suspicious of counter-examples that require you to create a “back-story” to explain the conditions under which an exception might work. The fact that you need a story to explain the context is evidence that the counter-example is very unusual in normal speech.

3 You could say “The bartenders’ road” or “The bartender’s road”, but that would not really count, since cars in the original sentence did not have an “apostrophe s.” In the starting sentence, cars was plural, not possessive or plural possessive.

4 Traditionally, students learned to categorise the parts of speech on the basis of meaning. For example, nouns were said to be “the name of a person, place, or thing,” while verbs were described as “action words.” While there is some truth to these definitions in many cases, the distinctions break down very easily in others. The fighting is a noun, even though it describes an action; is, on the other hand, is a verb, even though it describes a state.

Since words are a feature of grammar, the method used here attempts to identify them on the basis of their grammatical properties: the roles they can play in the sentence, the inflections they can take, how they can be converted from one part of speech to another.

5 “Always”, except in poetry, where they can sometimes follow the words they connect to the sentence.

6 This rule—pronouns never end in apostrophe -s—might be useful in helping you avoid the common stylistic/prescriptive grammar error of using it’s (actually the abbreviation for it is) in your writing instead of the possessive form, its. In speaking, of course, you can’t hear any difference.

Previous: Inflections (inflectional morphology)

Commenting is closed for this article.

It is a fact that almost every word of English has got the capacity to be employed as a different part of speech. At one place, a particular word may be used as a noun, at another as a verb, and yet at another place as an adjective.

These words enable the learners of the English language to understand the behavior of a particular word in various positions.

Importance of Parts of Speech in Communication

As you know, English sentences are used to communicate a complete thought. The importance of parts of speech lies in their proper utilization, which can help your understanding and confidence grow immensely.

Proper usage of parts of speech means that you can impart clear messages and understand them because you know the rules of the language.

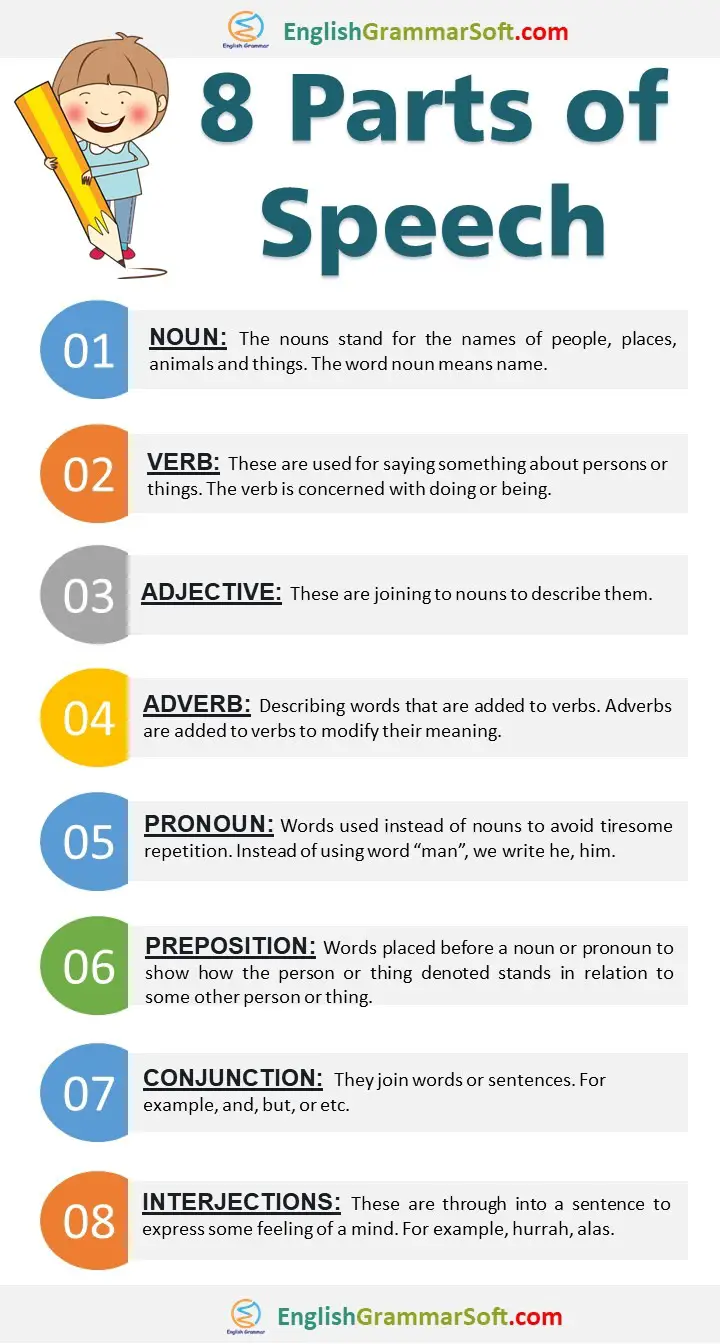

Each word in a sentence belongs to one of the eight parts of speech according to the work it is doing in that sentence. There are 8 parts of speech.

- Noun

- Verb

- Adjective

- Adverb

- Pronoun

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

1 – Noun (Naming words)

The nouns stand for the names of people, places, animals, and things. The word noun means name. Look at these sentences.

“John lives in Chicago. He has two bikes. He is fond of riding bikes.”

In the above example, John is the name. We cannot use the same name again and again in different sentences. Here, we used “he” in the next two sentences instead of “John”. “He” is called the pronoun.

Types of nouns are

1.1 – Common Noun

It describes a person, place, and thing.

Examples: City, country, town, boy.

1.2 – Proper Noun

It includes a particular person, place, thing, or idea and begins with a capital letter.

Examples: Austria, Manchester, United Kingdom, etc.

1.3 – Abstract Noun

An abstract noun describes names, ideas, feelings, emotions or qualities, the subject of any paragraph comes under this category. It does not take “the”.

Examples: grief, loss, happiness, greatness.

1.4 – Concrete Noun

It describes material things, persons or places. The existence of that thing can be physically observed.

Examples: Book, table, car, etc.

1.5 – Countable and Uncountable Noun

Countable nouns can be singular or plural. It can be counted.

Examples: Ships, cars, buses, books, etc.

The uncountable noun is neither singular nor plural. It cannot be counted.

Examples: Water, milk, juice, butter, music, etc.

1.6 – Collective Noun

It includes the group and collection

people, things or ideas. It is in unit form and is considered as singular.

Examples: Staff of office, group of visitors.

However, people and police can be

considered both singular and plural.

1.7 – Possessive Noun

It shows ownership or relationship.

Examples: Jimmy’s pen.

Further Reading: 11 Types of Nouns with Examples

2 – Verb (Saying words)

These are used for saying something

about persons or things. The verb is concerned with doing or being.

Examples

- A hare runs (action) very fast.

- Aslam is a good student.

Types of verbs

2.1 – Actions verbs

(run, move, write etc)

2.2 – Linking verbs

(to be (is, am, are, was, were), seem, feel, look, understand)

2.3 – Auxiliary (helping) verbs

(have, do, be)

2.4 – Modal Verbs

(can, could, may, might, will/shall)

2.5 – Transitive verbs

It takes an object.

Example – He is reading a newspaper.

2.6 – Intransitive verbs

It does not take the object.

Example – He awakes.

Further Reading: What are the verbs in English?

3 – Adjectives (describing words)

These are joining to nouns to describe

them.

Examples

- A hungry wolf.

- A brown wolf.

- A lazy boy.

- A tall man.

It is used before a noun and after a linking verb.

Before noun example

A new brand has been launched.

After linking verb example

Imran is rich.

It is used to clarify nouns.

Example: smart boy, blind man

Types of adjectives

3.1 – Simple degree

He is intelligent.

3.2 – Comparative

Ali is intelligent than Imran.

3.3 – Superlative

Comparison of one person with class,

country or world. In this type “the” is used.

Example: Ali is the wisest boy.

3.4 – Demonstrative adjective

It points out a noun. These are four

in number.

This That These Those

3.5 – Indefinite adjectives

It points out nouns. They often tell

“how many” or “how much” of something.

Interrogative adjectives: it is used to ask questions

Examples

- Which book?

- What time?

- Whose car?

Further Reading: More About Adjectives

4 – Adverbs

Describing words that are added to verbs. Just as adjectives are added to describe them, adverbs are added to verbs to modify their meaning. The word “modify” means to enlarge the meaning of the adverbs.

Examples

- Emma sings beautifully. (used with verb)

- Cameron is extremely clever. (used with adjective)

- This motor car goes incredibly fast. (used with another adverb)

Types of adverb

4.1 – Adverb of manner

This type of adverb deals with the

action something

Example

- I walk quickly.

- He wrote slowly.

4.2 – Adverb of place

Happening of something or the place where it happens.

Examples:

There was somebody sitting nearby.

Here, these, upstairs, nowhere everywhere, outside, in, out, are called adverb of place.

4.3 – Adverb of time

It determines the time of the happening of something.

Examples

- She went there last night.

- Have you seen him before?

- He wrote a letter yesterday.

Tomorrow, today, now, then,

yesterday, already, ago.

4.4 – Linking adverbs (then, however)

It creates a connection between two clauses or sentences.

Example

There will be clouds in Lahore. However, the sun is expected in Multan.

Note: Besides modifying the meaning of a verb, adverbs also modify adjectives and other adverbs.

Examples

- It is a very large house.

- He is too weak to walk.

- He ran too fast.

Further Reading: 11 Types of Adverbs with Examples

5 – Pronouns

Words that are used instead of nouns to avoid tiresome repetition. Instead of using the word man in a composition, we often write he, him, himself. In place of the word “woman”, we write she, her, or herself. For both the nouns ‘men’ and ‘women’ we use, they, them, themselves.

Some of the most common pronouns are

Singular: I, he, she, it, me, him,

her

Plural: We, they, out, us, them.

Examples

Imran was hurt. He didn’t panic.

He checked the mobile. It still

worked.

Types of Pronouns

It stands instead of persons. They have different forms according to the person who is supposed to be speaking.

First person: I, we, me, us, mine, our, ourselves.

Second person: thou, you, there.

Third person: He, she, it, his, him

5.1 – Possessive pronouns

Such as mine, ours, yours, hers and theirs.

- This book is mine.

- My horse and yours are tired.

5.2 – Relative pronoun

Who, whom, which and they are called relative pronouns. They are called relative because they relate to some word in the main clause. The word to which pronoun relates is called the antecedent.

Example

I saw a boy who was going.

In this sentence, who is the relative pronoun and boy is its antecedent.

This is the girl who won the prize.

“which” is used for animals and things.

The dog which barks.

That is used instead of who or which in this case.

This is the best picture that I ever saw.

5.3 – Interrogative pronouns

It is used to introduce or create an asking position in a sentence. Who, whom, which, and whose are interrogative pronouns.

Examples

Who wrote this book? (for persons

only)

What is your name? (for things)

Which boy here is your friend?

5.4 – Demonstrative pronoun

It points out a person, thing, place

or idea. This, that, these and those are called demonstrative pronouns.

That is a circuit-breaker.

These are cups of a team.

5.5 – Reflexive pronoun

The type of pronoun that ends in self or selves is called a reflexive pronoun.

Examples: myself, ourselves, yourself, herself, himself, itself, themselves.

Use in sentence: They worked hard to

get out themselves from the debt.

Indefinite pronoun: An indefinite

pronoun does not refer to a specific person, place thing or idea.

Examples

Nothing lasts forever.

No one can make this design.

Further Reading: Different Types of Pronouns with 60+ Examples

6 – Prepositions

Words placed before a noun or pronoun

to show how the person or thing denoted stands in relation to some other person

or thing.

Examples: A house on a hill. Here, the word “on” is a preposition.

The noun and pronoun that follow the preposition are called its object. We can identify prepositions in the following examples.

In 2006, in March, in the garden,

On 14th August, on Friday, on the table

At 8:30 pm, at 9 o’clock, at the door, at noon, at night, at midnight

However, we use “in” for morning and evening.

Further Reading: Preposition Usage and Examples

7 – Conjunctions (joining words)

They join words or sentences.

Examples: Jimmy and Tom are good players.

In the above sentence, “and” is a conjunction.

Types of conjunctions

These are the types of conjunctions.

- Nor (used in later part of the negative sentence)

- But (when two different ideas are described in a sentence)

- Yet (when two contrast things are being described in a sentence)

- So (To explain the reason)

- For (it connects a reason to a result)

- Or (to adopt two equal choices)

- And (to join two things or work)

Further Reading: Conjunction Rules with Examples

8 – Interjections

Interjection words are not connected with other parts of a sentence. They are through into a sentence to express some feeling of a mind.

Examples: Hurrah! We won the match.

Alas, hurrah, wow, uh, oh-no, gush, shh are some words used to express the feeling.

It is important to note that placing a word in this or that part of speech is not fixed. It depends upon the work the words are doing in a particular sentence. Thus the same word may appear in three or four parts of speech.

Further Reading: More about Interjections

You can read a detailed article about parts of speech here.

Parts of Speech Exercise with Answers

Read also: 71 Idioms with Meaning and Sentences

The

parts of speech

are classes

of words,

all the members of these classes having certain characteristics in

common which distinguish them from the members of other classesThe

problem of word classification into parts of speech still remains one

of the most controversial problems in modern linguistics. There are

four approaches to the problem:

-

Classical

(logical-inflectional) -

Functional

-

Distributional

-

Complex

1)Theclassical

parts

of speech theory goes back to ancient times. It is based on Latin

grammar. According to the Latin classification of the parts of speech

all words were divided dichotomically into declinable

and

indeclinable

parts

of speech. This system was reproduced in the earliest English

grammars. The first of these groups, declinable words, included

nouns, pronouns, verbs and participles, the second – indeclinable

words – adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections. it

cannot be applied to the English language because the principle of

declinability/indeclinability is not relevant for analytical

languages.2)

new approach to the problem was introduced in the 19 century by Henry

Sweet.

He took into account the peculiarities of the English language. This

approach may be defined as 2)functional.

He resorted to the functional features of words and singled out

nominative

units

and particles.

To nominative

parts of speech belonged noun-words

(noun, noun-pronoun, noun-numeral, infinitive, gerund),

adjective-words

(adjective, adjective-pronoun, adjective-numeral, participles), verb

(finite verb, verbals – gerund, infinitive, participles), while

adverb,

preposition,

conjunction

and interjection

belonged to the group of particles.3)

A distributional

approach

to the parts of speech classification can be illustrated by the

classification introduced by Charles

Fries.

He established a classification of words based on distributive

analysis,

that is, the

ability of words to combine with other words of different types.

At the same time, the lexical meaning of words was not taken into

account. . In this way, he introduced four major classes

of words

and 15 form-classes.

It

turned out that his four classes of words were practically the same

as traditional nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. What is really

valuable in Charles Fries’ classification is his investigation of

15 groups of function words (form-classes) because he was the first

linguist to pay attention to some of their peculiarities.

In

modern linguistics, parts of speech are discriminated according to

three criteria: semantic, formal and functional. This approach may be

defined as complex.

The semantic

criterion presupposes the grammatical meaning of the whole class of

words (general grammatical meaning). 4)The

formal

criterion

reveals paradigmatic properties: relevant grammatical categories, the

form of the words, their specific inflectional and derivational

features. The functional

criterion

concerns the syntactic function of words in the sentence and their

combinability. Thus, when characterizing any part of speech we are to

describe: a) its semantics; b) its morphological features; c) its

syntactic peculiarities.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

The basic building blocks of any language are the words and sounds of that language. English is no exception. We will start with the categories into which we classify the words of English. It is quite likely that you will already know the names of some or all of the parts of speech. Nevertheless, this is where we must begin.

The parts of speech are as follows:

- Nouns

- Pronouns

- Adjectives

- Verbs

- Adverbs

- Articles

- Determiners

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Prepositions

These are also known as word classes. The terms are familiar to most people, and are in everyday use. However, many people would probably admit that their understanding of some of them is a little sketchy. We will now take each in turn and have a closer look.

Nouns

What are nouns? Very few people with a good knowledge of English would expect to experience any difficulty in picking the nouns out of the following list:

briefcase, open, disc, plate, London, knife, write, usually, and, however, football, sing

My guess is that you probably decided that the following were nouns:

- briefcase

- disc

- plate

- London

- knife

- football

Who knows? Perhaps you are right. Briefcase is certainly a noun and London as a place name must be, but what about knife? This is a more difficult decision. We have no context. What if we found this word in a sentence such as ‘He knifed me!’ — surely here it is a verb? And what about ‘plate’ — is this a noun? Suppose the context were ‘The window was plate glass.’ Or perhaps, ‘The frame had been plated with silver.’ So is ‘disc’ a noun? Not always, it depends on how it is used in a particular sentence. The lesson here is ‘Be careful!’ When a student asks you the meaning of a word, always check the context in which it appears before answering. Remember in the world of TEFL, as in the world in general, it is not what you don’t know that gives you the biggest problems, but what you think you know!

So how can we define the word class ‘noun’ then? One apparently acceptable definition might be that a noun is a word that represents one of the following:

|

a person |

David |

|

a place |

Paris |

|

a thing |

stapler |

|

an activity |

hockey |

|

a quality |

responsibility |

|

a state |

poverty |

|

an idea |

communism |

Does a noun have to be a single word? What about ‘disc jockey,’ or ‘post office’? Are these nouns? The answer is ‘Yes they are’. These are called compound nouns and are quite common in English. So the word class ‘noun’ is not restricted to single words. Can a noun consist of more than two words then? Once again the answer is ‘yes’. An example might be ‘football team coach’. These are often found in newspaper headlines, where space is at a premium, since they usually express quite complex ideas in very few words.

In a sentence nouns can be used as either the subject or the object of the main verb.

John (subject) kissed (verb) Maria (object).

Types of Nouns

The word class ‘Nouns’ can be sub-divided into the following four types:

|

Abstract |

The name of an action, an idea, a physical condition, quality or state of mind |

an attack, Communism, liveliness, modesty, insanity |

|

Collective |

A name for a collection or group of animals, people or things that are thought of as being one thing |

flock, gang, fleet |

|

Common |

A name that can be applied to all members of a large class of animals, people or things |

puppy, woman, banana |

|

Proper |

The name by which a particular animal, organisation, person, place or thing is known |

Fido, Microsoft, Julia, Liverpool, the Tower of London. Capital letters are used in order to distinguish between common nouns and proper nouns e.g., broom and Broom, where the former is an implement used for sweeping floors while the latter is a surname. |

There are some nouns that can be placed in more than one of these groups depending on how we are thinking at the time of usage. An example would be the noun ‘family’, which could be a collective if we are thinking of the family as a unit e.g. ‘My family is quite large.’ Or a common noun if we are thinking in terms of a collection of individuals e.g. Helen’s family are coming up next week.’ Many Americans may find this particular example unacceptable since in most parts of the US ‘family’ can never agree with the plural verb form ‘is’. In British English, however, this usage is perfectly correct.

Nouns can also be divided into two other groups: countable and uncountable. Water, flour and sand are examples of uncountable nouns. It would be very strange to use them with a number as in six flours or three sands. Countable nouns, on the other hand, can be used with numbers: seven men, two houses, etc. Countable nouns have a plural form. This is usually made by the addition of an ‘s’ or ‘es’ to the end of the singular form: guitars, books, ships, glasses etc. Some countable nouns, however, have an irregular plural form: men, children, wives, geese, etc. Plural countable nouns are always used with plural verb forms. So ‘Coconuts are nice.’ and not *’Coconuts is nice.’* Uncountable nouns have only one form and therefore can only be used with singular verbs. So ‘Water is used as a coolant.’ but never *’Water are used as a coolant.’*

Back to Top

Pronouns

In English, sentences such as ‘John ran up to the house, checked to see John wasn’t being watched and then John knocked on the door twice.’ would cause confusion. How many Johns are involved? Which of them knocked on the door? Probably the solution least likely to occur to a native speaker of English would be that there was only one John and that he carried out all three actions. Why is that? Well, it’s because English just doesn’t work like that! The sentence should be rendered thus ‘John ran up to the house, checked to see he wasn’t being watched and then knocked on the door twice.’ So what makes the difference? Obviously it must be the use of the word ‘he’ in place of John in the second instance. What is ‘he’ then? ‘He’ is a member of the word class Pronouns. These are words that stand in the place of nouns in order to avoid unnecessary repetition.

Kinds of pronoun:

|

Demonstrative |

this, that, these, those, the former, the latter ( ‘Have you seen this?’) |

|

Distributive |

each, either, neither ( ‘Give me either.’) |

|

Emphatic |

myself, yourself, his/herself, ourselves, etc. ( ‘Do it yourself.’) |

|

Indefinite |

one, some, any, some-body/one, any-body/one, every-body/one |

|

Interrogative |

what, which, who ( ‘Who was that?’) |

|

Personal |

I, you, he, she, it, we, you, they |

|

Possessive |

mine, yours hers, his, ours, theirs |

|

Reflexive |

myself, yourself, her/himself, ourselves, etc. ( ‘She cut herself, while slicing bread.’) |

|

Relative |

that, what, which, who (as in, ‘The car that hit him went that way.’) |

It should be noted that some of these words may also at times be deemed adjectives. It is a feature of the English language that many words have multiple uses and hence can be different parts of speech according to the context in which they are found.

Back to Top

Adjectives

Adjectives are words that describe/qualify nouns or pronouns:

- ‘She was a quiet woman.’

- ‘That’s an unusual one.’

Types of adjective

|

Demonstrative |

this, that, these, those (‘I like this picture.‘) |

|

Distributive |

either, neither, each, every (‘Either wine is fine by me.‘) |

|

Interrogative |

what? which? (‘Which wine would you like?‘) |

|

Numeral |

one, two, three, etc. |

|

Indefinite |

all, many, several |

|

Possessive |

my, your, his, her, our, their |

|

Qualitative |

French, wooden, nice |

Not surprisingly, most adjectives fit into the ‘Qualitative‘ category, as their basic function is to describe.

Some adjectives are made from nouns or verbs by the addition of a suffix:

- comfort — comfortable

- health — healthy

- success — successful

- consume — consumable

- consider — considerate

Many positive adjectives can be made negative by the addition of a prefix:

- comfortable — uncomfortable

- responsible — irresponsible

- respectful — disrespectful

- patient — impatient

- considerate — inconsiderate

Comparative and Superlative Adjectives

Some adjectives are used to compare and contrast things:

- big — bigger — biggest

- happy — happier — happiest

There is more information about this important use later.

Verbs

Verbs are words that indicate actions or physical and/or mental states.

|

Action |

Susan slapped Michael. |

|

Mental state |

Paul was exhausted. |

|

Physical state |

Stephen felt sad. |

It is a popular misconception that verbs are ‘doing-words‘. Unfortunately, this is too simple an explanation as only some verbs fit this description. An example of one that doesn’t might be ‘seem‘ as in, ‘ Sarah seemed puzzled‘. What is ‘done‘ in this case? Absolutely nothing! In fact, only verbs indicating actions can be called ‘doing-words‘.

Most verbs have three forms. The first form (present) also uses an inflection to indicate third person singular:

|

First form (present) |

Second form (past) |

Third form (past participle) |

|

do(es) |

did |

done |

|

give(s) |

gave |

given |

|

like(s) |

liked |

liked |

|

hit(s) |

hit |

hit |

As you can see sometimes the second and third forms coincide, and occasionally all three forms coincide as in ‘hit’. This is because verbs such as hit, give, take, do, have, etc. are irregular. That is to say that, unlike the vast majority of English verbs, they don’t use ‘-ed’ to make their second and third forms. There are only about two hundred irregular verbs in total, but since they tend to be the most common verbs it seems more. These can be quite a problem for EFL students as they simply have to be learnt and remembered.

Auxiliary and Modal Auxiliary Verbs

There is a category of verb known as ‘auxiliary verbs‘ or sometimes ‘helping verbs‘. This category includes to be, to do and to have. These three verbs are very important. ‘Be‘ is used in forming the ‘continuous aspect‘ — I am flying to France tomorrow.’ It is also used to form the ‘passive‘ — ‘I was arrested.’ ‘Do‘ is used in forming questions and for emphasis. ‘Have‘ is used to form the ‘perfect aspect‘ — ‘I have been here before.’ More about these later, when we look at the English tense system.

Also included in the category auxiliary verbs are nine very special verbs, which form a sub-category of their own called ‘modal auxiliary verbs‘ or ‘modal verbs‘ for short. This sub-category comprises the verbs can, could, may, might, shall, should, will, would and must. These nine verbs share some important characteristics:

- They can never be followed by ‘to‘: ‘I must to go.’ is a badly formed sentence in English.

- They cannot co-occur in the same verb phrase: ‘You must can go’ is also unacceptable.

- They have no ‘third person‘ inflection: ‘She likes reading.’ is fine, but ‘ She cans swim.’ is not.

In a verb phrase they always occupy the first position — ‘It must have been my aunt.’ Likewise, they do not have three forms.

So what exactly do these ‘modal verbs‘ do? An interesting question! The following table should give you some idea.

Modal verbs are used to express:

|

Degrees of certainty |

Certainty (positive/negative) |

We shall/shan’t come. |

|

Probability/Possibility |

She should arrive at about midday. |

|

|

Weak probability |

She might call — you never know! |

|

|

Theoretical/habitual possibility |

You may have a problem |

|

|

Conditional certainty/possibility |

If you had asked me, I would |

|

|

Obligation |

Strong obligation |

All employees must clock in and out. |

|

Prohibition |

Staff must not make personal calls. |

|

|

Weak obligation/recommendation |

When shall we leave? |

|

|

Willingness/Offering |

Can I help you? |

|

|

Permission |

Might I ask a favour? |

|

|

Ability |

Can you swim? |

|

|

Other uses |

Habitual behaviour |

When I was a boy, I would often go skiing. |

|

Irritation |

Must you do that? |

|

|

Requests |

Would you open the window please? |

Some linguists include verbs such as dare, need and ought in the modal verb sub-category. There is some justification for this, as they display the relevant characteristics some of the time. However, since they do not do so all the time it is better to leave them out of this group.

Back to Top

Adverbs

Adverbs describe or add to the meaning of verbs, prepositions, adjectives, other adverbs and even sentences. They answer questions such as ‘How’, ‘Where’ or ‘When’. Many, but by no means all, adverbs are made from adjectives by simply adding the suffix ‘ly’.

Types of adverb:

|

Adverbs of manner |

carefully, gently, quickly, willingly (She kissed him gently on the forehead.) |

|

Adverbs of place |

here, there, between, externally (He lived between a pub and a noisy factory.) |

|

Adverbs of time |

now, annually, tomorrow, recently (I only returned recently.) |

|

Adverbs of degree |

very, almost, nearly, too (She is very rich.) |

|

Adverbs of number |

|

|

Adverbs of certainty |

not, surely, maybe, certainly (Surely he’s not drunk again!) |

|

Interrogative |

How? What? When? Why? (What does it matter?) |

Adverbials

An adverbial is a general term for any word, phrase or clause that functions as an adverb. The definition is necessary because sometimes whole phrases and clauses act as adverbs:

- When I arrived she was watching TV. (adverbial time clause)

- We went to France to visit my brother. (adverbial clause of purpose)

- After breakfast, I went to work. (adverbial phrase)

An ordinary adverb is a single word adverbial.

The adverb/adverbial is quite a difficult area of the English language to get to grips with. It has been said that, when all the other words of English had been classified as nouns, verbs, prepositions, etc., those remaining were dumped into the adverb class because nobody knew what else to do with them. Even if this is not entirely historically accurate, it certainly describes the confused state of this word class.

Back to Top

Articles

The articles in English are the words ‘a‘, ‘an‘ and ‘the‘. They are used with nouns to distinguish between the definite and the indefinite. They are not really a word class in themselves but are actually a sub-group of the word class Determiners. However, EFL usually treats them as a class and so they are dealt with separately here.

The definite article is ‘the‘. Its most common uses are to show that the nouns it is used with refer to:

|

something known to both speaker and listener |

He is in the garage. |

|

something that has already been mentioned |

That woman keeps looking at you. |

|

something that is defined afterwards |

The house where my mother was born is somewhere near here. |

|

something as a specific group or class |

Can you play the piano? (But not ‘Can you play the instrument?’ — Unless which instrument is being referred to is understood by both speaker and listener.) |

The indefinite article is ‘a(n)». I write ‘is’ because ‘a’ and ‘an’ are really the same word: the ‘n’ is added to the article ‘a’ for ease of pronunciation when the following word begins with a vowel sound — an egg, an ostrich, an upwards motion but a unicorn, a united front (because unicorn and united begin with consonant sounds).

The most common uses of the indefinite article are to show that the nouns it is used with refer to:

|

one example of a group or class |

I’ll buy her an ornament for her birthday. |

|

a typical example of a group or class |

A reliable worker deserves a good boss. |

It should be noted that the indefinite implies ‘oneness’ and so cannot be used with plural or uncountable nouns.

Finally, there are some nouns (apart from plural and uncountable) with which articles are not usually used. Examples of these are the names of countries, towns and cities and of people, months, mealtimes (breakfast, lunch, etc.). Where no article is used this is often referred to as the ‘Zero article‘.

For the EFL student articles either present no difficulty at all, or are a major obstacle in their acquisition of English. The determining factor seems to be whether or not there are articles in the student’s first (native) language (L1). If it doesn’t have them, then the student will have additional problems to face when studying a second language (L2) that does. Even quite advanced students make frequent slips with articles. Compounding the problem is the fact that there are no good rules as far as articles are concerned. Many course books offer ‘rules’ but there are so many exceptions that they are difficult to apply and students have to fall back on learning them by heart. Fortunately,

In order to gain some understanding of the difficulty from a teaching perspective, how would you set about explaining to a student with absolutely no understanding of articles why the fourth of the following sentences is unacceptable in English? Then, having done that, how would you explain why the second is fine?

- ‘I stopped the car and got in.’

- ‘I stopped a car and got in.’

- ‘I stopped the car and got out.’

- *’I stopped a car and got out.’*

Or perhaps it is easier to explain why ‘the Moscow’ might be the river Moscow, the hotel Moscow or the restaurant Moscow but couldn’t possibly be the city of that name. Or why, in British English at least, if you are ‘going to the prison’, you are probably visiting someone or maybe you work there, whereas if you are just ‘going to prison’, you are going because you have been convicted of a crime.

By far the biggest problem with articles is not so much when to use ‘a’, ‘an’ or ‘the’ but when not to use an article at all!

Back to Top

Determiners

As has already been mentioned, the determiners are a word class that would normally include the articles, however, as is usual in TEFL, they have been listed above separately. Even so, it is important for the new teacher to understand that this distinction is false.

Determiners are words that restrict the meaning of the nouns they are used with. For example, ‘But I’m certain I put it in this cupboard. Where can it have got to?’ Even if we cannot see what is happening, we understand, from the speaker’s use of ‘this‘, that there must be more than one cupboard. Despite the obvious similarities, it should be clearly understood that determiners are not adjectives.

Types of determiner:

|

Articles |

a pen, the house |

|

Demonstratives |

this hat, these hats, that book, those books |

|

Possessives |

my dog, your sunglasses, her car, etc. |

|

Quantifiers |

many choices, some people, several hooligans, etc. |

|

Numerals |

the second option, seven possibilities, etc. |

Determiners can be grouped according to how they are used:

Group A includes the articles, demonstratives and possessives. The use of a Group A determiner allows us to understand whether or not the speaker believes the listener knows which one(s) is being referred to (e.g. a car, the car), or whether the speaker is talking about a specific example(s) or in general. It is not possible to put two group A determiners together in a phrase: so ‘the car‘ is fine but *’the her car‘* is not. If for some reason we want to do so, we have to use a structure using ‘of‘ (e.g. ‘this husband of yours‘).

Group B is composed mainly of quantifiers. It is possible to put two Group B determiners together where their individual meanings allow it. For example, ‘As a punishment for the city’s stubborn resistance, the invaders executed every third person.’

Most Group B determiners do not use ‘of‘ when placed before nouns (‘Do you have any cream?’ not *’Do you have any of cream?’*). However, when used in combination with a Group A determiner, ‘of‘ must be used (‘Several books were badly damaged in the fire.’, but ‘Several of the books were badly damaged in the fire.’). There are a few cases where a Group B determiner is used in combination with ‘of‘ when placed directly before a noun. These are mostly either place names (‘Most of London was destroyed in the great fire.’) or uncountable nouns that refer to entire subjects or activities (‘It is difficult to determine, with any great certainty, exactly what really happened in the past because much of recorded history was set down by interested parties.’).

Another important thing to be aware of, since many EFL students make this mistake, is that the ‘of‘ structure is not used after the Group B determiners ‘no‘ and ‘every‘. Instead ‘none‘ and ‘every one‘ are used (‘Every student was happy.’, but ‘Every one of her students were happy.’).

The correct use of ‘of‘ with determiners is a complex area and warrants more space than is available here. Those wishing to delve into this more deeply are again advised to refer to Michael Swan’s Practical English Usage.

Back to Top

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are words that join words, phrases or clauses together and show the relationships that exist between them. Examples of these are: but, and, or (these are known as co-ordinating conjunctions).

- ‘but» is most often used to join and emphasise contrasting ideas: ‘They were exhausted, but very happy.’

- ‘and‘ is simply used to join things without unduly emphasising any differences that may exist (which is not to say that ‘and» cannot be emphatic — with the right intonation obviously it can be.): ‘He put on his hat, coat and an air of indifference.’

Other conjunctions like ‘when‘, ‘because‘, ‘that‘ are known as subordinating conjunctions and unlike the co-ordinating conjunctions are a part of the clause they join.

- ‘when‘ is used to join a time clause to the rest of a sentence: ‘I was shocked when they announced they were giving the prize to me’.

- ‘because‘ joins a fact with its cause: ‘He lied because he thought the truth would hurt her.’

- ‘that‘ is used to join clauses that are acting as the object of a verb: He promised her that he would come if he could. (Compare the above with He(subject) promised(verb) her(indirect object) a new dress(object))

Conjunctions can consist of more than one word. Examples of these are: ‘such as‘, ‘in order to‘, etc.

Back to Top

Interjections

Interjections are words such as ‘Yuck!‘, ‘Ugh!‘, and ‘Ouch!‘ which indicate the emotions, like disgust, fear, shock, delight, etc., of the person who utters them.

Back to Top

Prepositions

Prepositions are words which are used to link nouns, pronouns and gerunds ( the ‘-ing‘ form of a verb which is being used as a noun e.g. ‘At high level Swimming is a very demanding sport.’) to other words. They are often short words like ‘on‘, ‘in‘, ‘up‘, ‘down‘, ‘about‘, etc. They can consist of more than one word: in front of, next to, etc.

In TEFL we talk a lot about prepositions of time, place and movement:

|

Time |

I’ll see you at six o’clock. |

|

I’ll be home by five. |

|

|

We’re having a party on Christmas eve. |

|

|

Let’s have a party at Christmas. |

|

|

Place |

I’m in London at the moment. |

|

He’s at work, I’m afraid. |

|

|

The bookshop is on the second floor. |

|

|

She always leaves a key under the doormat. |

|

|

Movement |

She went to post office. |

|

He flew here from Guyana. |

|

|

He leapt over the gate. |

|

|

An elderly man was slowly climbing up the hill. |

These of course are not the only prepositions. The biggest problem for EFL students and therefore for their teachers is that it is almost impossible to predict which preposition combines with which verb, noun or adjective in any particular case, or even whether one is necessary at all. Here are some examples to demonstrate this point:

- agree with somebody about a subject but on a decision and to a suggestion,

- angry with somebody about something (at could also be used in both cases), or angry with/at somebody for doing something

- get/be married to somebody but marry somebody (no preposition)

- ‘pay for the tickets’, but ‘pay a bill’.

To a native speaker of English these may at first sight seem obvious, but to an EFL student they are impossible to guess. After all what is really wrong with *’get married on somebody’*? This would be perfectly correct in a number of languages. Even native speakers fail to agree on the use of some prepositions: Americans can say ‘Congratulations for your exam results!’, or ‘In America football is different than soccer.’ but these feel very wrong to the British, who would prefer to say ‘Congratulations on your exam results .’, and ‘In America football is different from soccer.’ Interestingly, British English does allow ‘different than‘ if it is followed by a clause e.g. The situation is different than I expected.’ It should be said, however, that the impact of Hollywood on British English seems to be gradually causing these differences to disappear.

Another complication is that it is often very difficult to know whether a word is, in fact, an adverb particle or a preposition as many can be either depending on the particular context in which they are found. This creates a problem in distinguishing between phrasal verbs and prepositional verbs. In the sentence ‘She fell off her chair.’ Off is a preposition while in the sentence ‘She turned off the radio.’ it is an adverb particle. Why is this so important? Well, lets take a moment to consider these two examples.

1. She turned off the radio.

What happens to the word order in the above sentence if we replace ‘the radio’ with the pronoun ‘it’? We have to place ‘it’ between the verb and its adverb particle — ‘She turned it off.’ We cannot say *’She turned off it.’* We can, however, say ‘She turned the radio off.’

2. She fell off her chair.

What if we do the same to this sentence? We get ‘She fell off it (because she was laughing so much).’ In this case, we cannot insert ‘it’ into the middle of the prepositional verb. Nor can we say *’She fell the chair off.’*

No problem for a native speaker, of course, they ‘know’ what is right, but what about the poor EFL student, who doesn’t have this ‘knowledge’? And what about the poor EFL teacher, who has to find some way to help their students with this?

No matter what language is being studied prepositions are always a problem.

End of Section 1 Parts of Speech

Back to Top

Foundation TEFL methodology course

80 HOURS OF INPUT

- Engaging & interactive assignments

- Based on decades of combined experience

- Learn anywhere at any time

EXPLORE THE WORLD OF TEACHING! TEACH, INSPIRE & GROW

Parts of Speech. Principles of Classification of the Parts of Speech.

√ Parts of speech.

√ Semantic.

√ Morphological.

√ Syntactic.

√ Meaning.

√ Form.

√ Function

√ Meaning

Parts of speech

Parts of speech are grammatical classes of words which are distinguished on the basis of four criteria:

— semantic;

— morphological;

— syntactic;

that of valency (combinability)

1) Meaning. Each part of speech is characterized by the general meaning which is an abstraction from the lexical meaning of the constituent word. Thus, the general meaning of nouns is thingness (substance), the general meaning of verbs is action, state, process; the general meaning of adjectives — quality, quantity.

The general meaning is understood as categorial meaning of the class of words.

Semantic properties of every part of speech find their expression in their grammatical properties. If we take «to sleep, a night sleep, sleepy, asleep» they all refer to the same phenomena of the objective reality but belong to different parts of speech as they have different grammatical properties.

Meaning is supportive criterion in the English language which only helps to check purely grammatical criteria — those of form and function.

Глокая куздра штэка будланула бокра и кудрячит бокрёнка. V. V. Vinogradov

Green ideas sleep furiously.

Such examples though being artificial help us to understand that — grammatical meaning is an objective thing by itself though in real speech it never exists without lexical meaning.

2) Form, (morphological properties) The formal criterion concerns the inflectional and derivational features of words belonging to a given class. That is the grammatical categories they possess, the paradigms they form and derivational and functional morphemes they have.

With the English language this criterion is not always reliable as many words in English are invariable, many words have no derivational affixes and besides the same derivational affixes may be used to build different parts of speech.(e.g. «~ly»: quickly , daily , weakly(n.)).

Because of the limitation of meaning and form as criterion we should rely mainly on words’ syntactic functions (e.g. «round» can be adjective, noun, verb, preposition).

3) Function. Syntactic properties of any class of words are: combinability (distributional criterion), typical syntactic functions in a sentence. The three criteria of defining grammatical classes of words in English may be placed in the following order: syntactic, distribution, form, meaning (Russian: form, meaning, syntactic distribution).

Parts of speech are heterogeneous classes and the boundaries between them are not clearly cut especially in the area of meaning. Within a part of speech there are subclasses which have all the properties of a given class and subclasses which have only some of these properties and may even have features of another class.

So a part of speech may be described as a field which includes both central (most typical) members and marginal (less typical) members. Marginal areas of different parts of speech may overlap and there may be intermediary elements with contradicting features (modal words, statives, pronouns and even verbs).

Words belonging to different parts of speech may be united by common feature and they may constitute a class cutting across other classes (e.g. determiners or quantifiers).

Possible Ways of the Grammatical Classification of the Vocabulary.

The parts of speech and their classification usually involves all the four criteria mentioned and scholars single out from 8 to 13 parts of speech in modern English. The founder of English scientific grammar Henry Sweet finds the following classes of words: noun-words ( here he includes some pronouns and numerals), adjective-words, verbs 4 particles (by this term he denotes words of different classes which have no grammatical categories).

The opposite criterion — structural or distributional — was used by an American scholar Charles Freeze. Each class of words is characterized by a set of positions in a sentence which are defined by substitution test. As a result of distributional analysis Freeze singles out 4 main classes of words roughly corresponding to verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs and 15 classes of function-words.

Notional and Functional Parts of Speech.

Both the traditional and distributional classification divide parts of speech into notional and functional. Notional parts of speech are open classes, new items can be added to them, we extend them indefinitely. Functional parts of speech are closed systems including a limited number of members. As a rule they cannot be extended by creating new items.

Main notional parts of speech are nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs. Members of these four classes are often connected derivationally. Functional parts of speech are prepositions, conjunctions, articles, interjections & particles. Their distinctive features are:

— very general & weak lexical meaning;

— obligatory combinability;